Compassionate Presence: Covert Training Invites Subtle Energies Insights

Posted: January 20, 2025 Filed under: attention, healing, meditation, mindfulness, relaxation, Uncategorized | Tags: being safe, compassion, energy, Energy healing, healing, reiki, spirituality, therapeutic touch Leave a commentAdapted from: Peper, E. (2015). Compassionate Presence: Covert Training Invites Subtle Energies Insights. Subtle Energies Magazine, 26(2), 22-25. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283123475_Compassionate_Presence_Covert_Training_Invites_Subtle_Energies_Insights

“Healing is best accomplished when art and science are conjoined, when body and spirit are probed together. Only when doctors can brood for the fate of a fellow human afflicted with fear and pain do they engage the unique individuality of a particular human being…a doctor thereby gains courage to deal with the pervasive uncertainties for which technical skill alone is inadequate. Patient and doctor then enter into a partnership as equals.

I return to my central thesis. Our health care system is breaking down because the medical profession has been shifting its focus away from healing, which begins with listening to the patient. The reasons for this shift include a romance with mindless technology.” Bernard Lown, MD, The Lost art of healing: Practicing Compassion in Medicine (1999)

Therapeutic Touch healing by Dora Kunz.

I wanted to study with the healer and she instructed me to sit and observe, nothing more. She did not explain what she was doing, and provided no further instructions. Just observe. I did not understand. Yet, I continued to observe because she knew something, she did something that seemed to be associated with improvement and healing of many patients. A few showed remarkable improvement – at times it seemed miraculous. I felt drawn to understand. It was an unique opportunity and I was prepared to follow her guidance.

The healer was remarkable. When she put her hands on the patient, I could see the patient’s defenses melt. At that moment, the patient seemed to feel safe, cared for, and totally nurtured. The patient felt accepted for just who she was and all the shame about the disease and past actions appeared to melt away. The healer continued to move her hands here and there and, every so often, she spoke to the client. Tears and slight sobbing erupted from the client. Then, the client became very peaceful and quiet. Eventually, the session was finished and the client expressed gratitude to the healer and reported that her lower back pain and the constriction around her heart had been released, as if a weight had been taken from her body.

How was this possible? I had so many questions to ask the healer: “What were you doing? What did you feel in your hands? What did you think? What did you say so softly to the client?”

Yet she did not help me understand how I could do this. The main instruction the healer kept giving me was to observe. Yes, she did teach me to be aware of the energy fields around the person and taught me how I could practice therapeutic touch (Kreiger, 1979; Peper, 1986; Kunz & Peper,1995; Kunz & Krieger, 2004; Denison, 2004; van Gelder & Chesley, F, 2015). But she was doing much more and I longed to understand more about the process.

Sitting at the foot of the healer, observing for months, I often felt frustrated as she continued to insist that I just observe. How could I ever learn from this healer if she did not explain what I should do! Does the learning occur by activating my mirror neurons (Acharya & Shukla, 2012).? Similar instructions are common in spiritual healing and martial arts traditions – the guru or mentor usually tells an apprentice to observe and be there. But how can one gain healing skills or spiritual healing abilities if you are only allowed to observe the process? Shouldn’t the healer be demonstrating actual practices and teaching skills?

After many sessions, I finally realized that the healer’s instruction to to learn was to observe and observe. I began to learn how to be present without judging, to be present with compassion, to be present with total awareness in all senses, and to be present without frustration. The many hours at the foot of this master were not just wasted time. It eventually became clear that those hours of observation were important training and screening strategies used to insure that only those students who were motivated enough to master the discipline of non-judgmental observation, the discipline to be present and open to any experience, would continue to participate in the training process. I finally understood. I was being taught a subtle energies skill of compassionate, and mindful awareness. Once I, the apprentice, achieved this state, I was ready to begin work with clients and master technical aspects of the healing practice – but not before.

A major component of the healing skill that relies on subtle energies is the ability to be totally present with the client without judgment (Peper, Gibney & Wilson, 2005). To be peaceful, caring, and present seems to create an energetic ambiance that sets stage, creates the space, for more subtle aspects of the healing interaction. This energetic ambiance is similar to feeling the love of a grandparent: feeling total acceptance from someone who just knows you are a remarkable human being. In the presence of a healer with such a compassionate presence, you feel safe, accepted, and engaged in a timeless state of mind, a state that promotes healing and regeneration as it dissolves long held defensiveness and fear-based habits of holding others at bay. This state of mind provides an opportunity for worries and unsettled emotions to dissipate. Feeling safe, accepted, and experiencing compassionate love supports the bological processes that nurture regeneration and growth.

How different this is from the more common experience with health care/medical practitioners who have little time to listen and to be with a patient. We might experience a medical provider as someone who sees us only as an illness (the cancer patient, the asthma patient) instead of recognizing us as a human spirit who happens to have an illness ( a person with cancer or asthma). At times we can feel as though we are seen only as a series of numbers in a medical chart – yet we know we are more than that. People long to be seen. Often the medical provider interrupts with unrelated questions instead of listening. It becomes clear that the computerized medical record is more important than the human being seated there. We can feel more fragmented, less safe, when we are not heard, not understood.

As one 23 year old student reported after being diagnosed with a serious medical condition,”/ cried immediately upon leaving the physician’s office. Even though he is an expert on the subject, I felt like I had no psychological support. I was on Gabapentin, and it made me very depressed. I thought to myself: Is my life, as I know it, over?” (Peper, Martinez Aranda, P., & Moss, 2015).

The healing connection is often blocked, the absence of a human connection is so obvious. The medical provider may be unaware of the effect of their rushed behavior and lack of presence. They can issue a diagnosis based on the scientific data without recognizing the emotional impact on the person receiving it.

What is missing is compassion and caring for the patient. Sitting at the foot of the master healer is not wasted time when the apprentice learns how to genuinely attend to another with non-judgmental, compassionate presence. However, this requires substantial personal work. Possibly all healthcare providers should be required, or at least invited, to learn how to attain the state of mind that can enhance healing. Perhaps the practice of medicine could change if, as Bernard Lown wrote, the focus were once again on healing, “…which begins with listening to the patient.”

References

Acharya, S., & Shukla, S. (2012). Mirror neurons: Enigma of the metaphysical modular brain. Journal of natural science, biology, and medicine, 3(2), 118–124. https://doi.org/10.4103/0976-9668.101878

Denison, B. (2004). Touch the pain away: New research on therapeutic touch and persons with fibromyalgia syndrome. Holistic nursing practice, 18(3), 142-151. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004650-200405000-00006

Krieger, D. (1979). The therapeutic touch: How to use your hands to help or to heal. Vol. 15. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. https://www.amazon.com/Therapeutic-Touch-Your-Hands-Help/dp/067176537X

Kunz, D. & Krieger, D. (2004). The spiritual dimension of therapeutic touch. Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions/Bear & Co. https://www.amazon.com/Spiritual-Dimension-Therapeutic-Touch/dp/1591430259/

Kunz, D., & Peper, E. (1995). Fields and their clinical implications. In Kunz, D. Spiritual Aspects of the Healing Arts. Wheaton, ILL: Theosophical Pub House, 213-222. https://www.amazon.com/Spiritual-Aspects-Healing-Arts-Quest/dp/0835606015

Lown, B. (1999). The lost art of healing: Practicing compassion in medicine. New York, NY: Ballantine Books. https://www.amazon.com/Lost-Art-Healing-Practicing-Compassion/dp/0345425979

Peper, E. (1986). You are whole through touch: An energetic approach to give support to a breast cancer patient. Cooperative Connection. VII (3), 1-6. Also in: (1986/87). You are whole through touch: Dora Kunz and Therapeutic Touch. Somatics. VI (1), 14-19. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280884245_You_are_whole_through_touch_Dora_Kunz_and_therapeutic_touch

Peper, E. (2024). Reflections on Dora and the Healing Process, webinar presented to the Therapeutic Touch International Association, Saturday, December 14, 2024. https://youtu.be/skq9Chn-eME?si=HJNAhiUsgXSkqd_5

Peper, E., Gibney, K. H. & Wilson, V. E. (2005). Enhancing Therapeutic Success–Some Observations from Mr. Kawakami: Yogi, Teacher, Mentor and Healer. Somatics. XIV (4), 18-21. https://biofeedbackhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/edited-enhancing-therapeutic-success-8-23-05.pdf

Peper, E., Martinez Aranda, P., & Moss, E. (2015). Vulvodynia treated successfully with breathing biofeedback and integrated stress reduction: A case report. Biofeedback, 43(2), 103-109. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-43.2.04

Van Gelder, K & Chesley, F. (2015). A Most Unusual Life. Wheaton Ill: Theosophical Publishing House. https://www.amazon.com/Most-Unusual-Life-Clairvoyant-Theosophist/dp/0835609367

[1] I thank Peter Parks for his superb editorial support.

Posture affects memory recall and mood

Posted: November 25, 2017 Filed under: Exercise/movement, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: cognitive therapy, depression, empowerment, energy, helplessness, memory, mood, posture, power posture, somatics 5 CommentsThis blog has been reprinted from: Peper, E., Lin, I-M., Harvey, R., & Perez, J. (2017). How posture affects memory recall and mood. Biofeedback, 45 (2), 36-41.

When I sat collapsed looking down, negative memories flooded me and I found it difficult to shift and think of positive memories. While sitting erect, I found it easier to think of positive memories. -Student participant

The link between posture and mood is embedded in idiomatic phrases such as walking tall, standing proud, and an upstanding citizen, versus collapsed, defeated, or in a slump–Language suggests that posture and mood/emotions are connected. Slumped posture is commonly observed in depression (Canales et al., 2010; Michalak et al., 2009) and adapting an upright posture increases positive affect, reduces fatigue, and increases energy in people with mild to moderate depression (Wilkes et al., 2017; Peper & Lin, 2012).

The link between posture and mood is embedded in idiomatic phrases such as walking tall, standing proud, and an upstanding citizen, versus collapsed, defeated, or in a slump–Language suggests that posture and mood/emotions are connected. Slumped posture is commonly observed in depression (Canales et al., 2010; Michalak et al., 2009) and adapting an upright posture increases positive affect, reduces fatigue, and increases energy in people with mild to moderate depression (Wilkes et al., 2017; Peper & Lin, 2012).

This blog describes in detail our research study that demonstrated how posture affects memory recall (Peper et al, 2017). Our findings may explain why depression is increasing the more people use cell phones. More importantly, learning posture awareness and siting more upright at home and in the office may be an effective somatic self-healing strategy to increase positive affect and decrease depression.

Background

Most psychotherapies tend to focus on the mind component of the body-mind relationship. On the other hand, exercise and posture focus on the body component of the mind/emotion/body relationship. Physical activity in general has been demonstrated to improve mood and exercise has been successfully used to treat depression with lower recidivism rates than pharmaceuticals such as sertraline (Zoloft) (Babyak et al., 2000). Although the role of exercise as a treatment strategy for depression has been accepted, the role of posture is not commonly included in cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) or biofeedback or neurofeedback therapy.

The link between posture, emotions and cognition to counter symptoms of depression and low energy have been suggested by Wilkes et al. (2017) and Peper and Lin (2012), . Peper and Lin (2012) demonstrated that if people tried skipping rather than walking in a slouched posture, subjective energy after the exercise was significantly higher. Among the participants who had reported the highest level of depression during the last two years, there was a significant decrease of subjective energy when they walked in slouched position as compared to those who reported a low level of depression. Earlier, Wilson and Peper (2004) demonstrated that in a collapsed posture, students more easily accessed hopeless, powerless, defeated and other negative memories as compared to memories accessed in an upright position. More recently, Tsai, Peper, and Lin (2016) showed that when participants sat in a collapsed position, evoking positive thoughts required more “brain activation” (i.e. greater mental effort) compared to that required when walking in an upright position.

Even hormone levels also appear to change in a collapsed posture (Carney, Cuddy, & Yap, 2010). For example, two minutes of standing in a collapsed position significantly decreased testosterone and increased cortisol as compared to a ‘power posture,’ which significantly increased testosterone and decreased cortisol while standing. As Professor Amy Cuddy pointed out in herTechnology, Entertainment and Design (TED) talk, “By changing posture, you not only present yourself differently to the world around you, you actually change your hormones” (Cuddy, 2012). Although there appears to be controversy about the results of this study, the overall findings match mammalian behavior of dominance and submission. From my perspective, the concepts underlying Cuddy’s TED talk are correct and are reconfirmed in our research on the effect of posture. For more detail about the controversy, see the article by Susan Dominusin in the New York Times, “When the revolution came for Amy Cuddy,”, and Amy Cuddy’s response (Dominus, 2017;Singal and Dahl, 2016).

The purpose of our study is to expand on our observations with more than 3,000 students and workshop participants. We observed that body posture and position affects recall of emotional memory. Moreover, a history of self-described depression appears to affect the recall of either positive or negative memories.

Method

Subjects: 216 college students (65 males; 142 females; 9 undeclared), average age: 24.6 years (SD = 7.6) participated in a regularly planned classroom demonstration regarding the relationship between posture and mood. As an evaluation of a classroom activity, this report of findings was exempted from Institutional Review Board oversight.

Procedure

While sitting in a class, students filled out a short, anonymous questionnaire, which asked them to rate their history of depression over the last two years, their level of depression and energy at this moment, and how easy it was for them to change their moods and energy level (on a scale from 1–10). The students also rated the extent they became emotionally absorbed or “captured” by their positive or negative memory recall. Half of the students were asked to rate how they sat in front of their computer, tablet, or mobile device on a scale from 1 (sitting upright) to 10 (completely slouched).

Two different sitting postures were clearly defined for participants: slouched/collapsed and erect/upright as shown in Figure 1. To assume the collapsed position, they were asked to slouch and look down while slightly rounding the back. For the erect position, they were asked to sit upright with a slight arch in their back, while looking upward.

Figure 1. Sitting in a collapsed position and upright position (photo by Jana Asenbrennerova). Reprinted by permission from Gorter and Peper (2011).

Figure 1. Sitting in a collapsed position and upright position (photo by Jana Asenbrennerova). Reprinted by permission from Gorter and Peper (2011).

After experiencing both postures, half the students sat in the collapsed position while the other half sat in the upright position. While in this position, they were asked to recall/evoke as many hopeless, helpless, powerless, or defeated memories as possible, one after the other, for 30 seconds.

After 30 seconds they were reminded to keep their same position and let go of thinking negative memories. They were then asked to recall/evoke only positive, optimistic, or empowering memories for 30 seconds.

They were then asked to switch positions. Those who were collapsed switched to sitting erect, and those who were erect switched to sitting collapsed. Then they were again asked to recall/evoke as many hopeless, helpless, powerless, or defeated memories as possible one after the other for 30 seconds. After 30 seconds they were reminded to keep their same position and again let go of thinking of negative memories. They were then asked to recall/evoke only positive, optimistic, or empowering memories for 30 seconds, while still retaining the second posture.

They then rated their subjective experience in recalling negative or positive memories and the degree to which they were absorbed or captured by the memories in each position, and in which position it was easier to recall positive or negative experiences.

Results

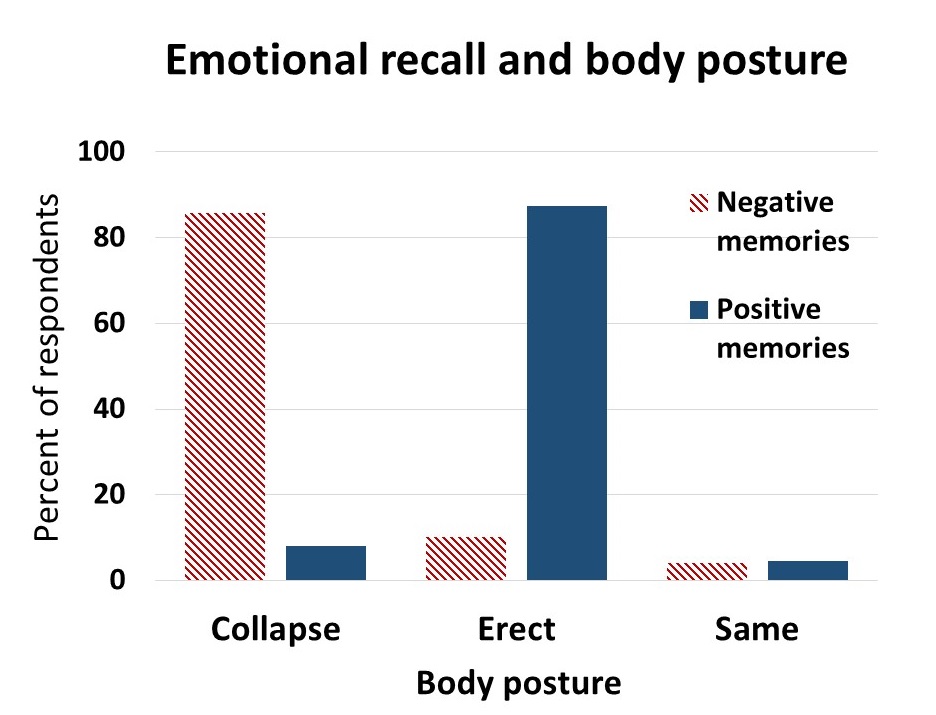

86% of the participants reported that it was easier to recall/access negative memories in the collapsed position than in the erect position, which was significantly different as determined by one-way ANOVA (F(1,430)=110.193, p < 0.01) and 87% of participants reported that it was easier to recall/access positive images in the erect position than in the collapsed position, which was significantly different as determined by one-way ANOVA (F(1,430)=173.861, p < 0.01) as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Percent of respondents who reported that it was easier to recall positive or negative memories in an upright or slouched posture.

Figure 2. Percent of respondents who reported that it was easier to recall positive or negative memories in an upright or slouched posture.

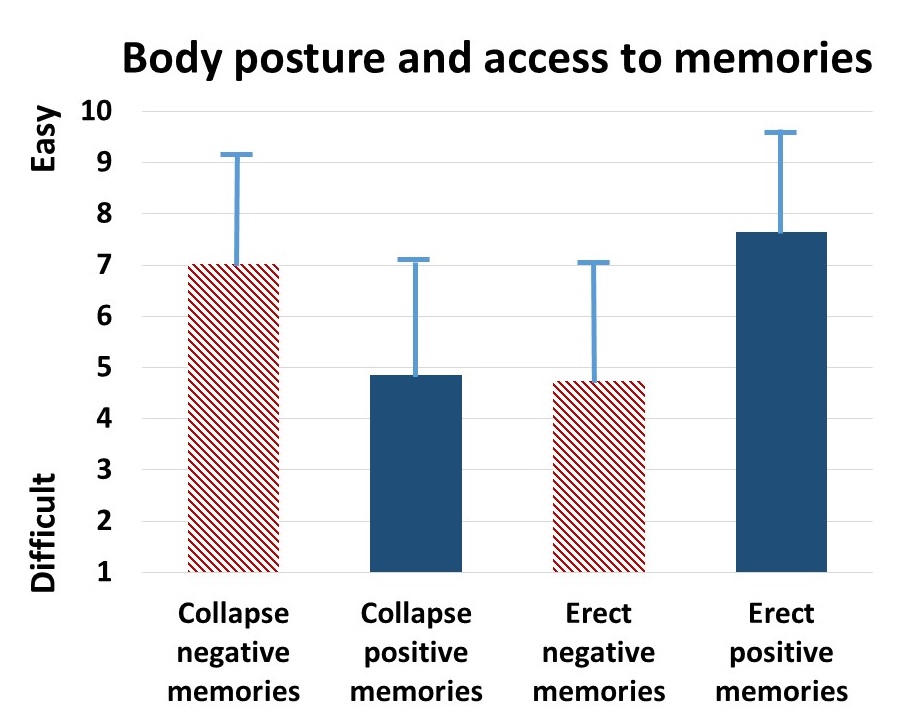

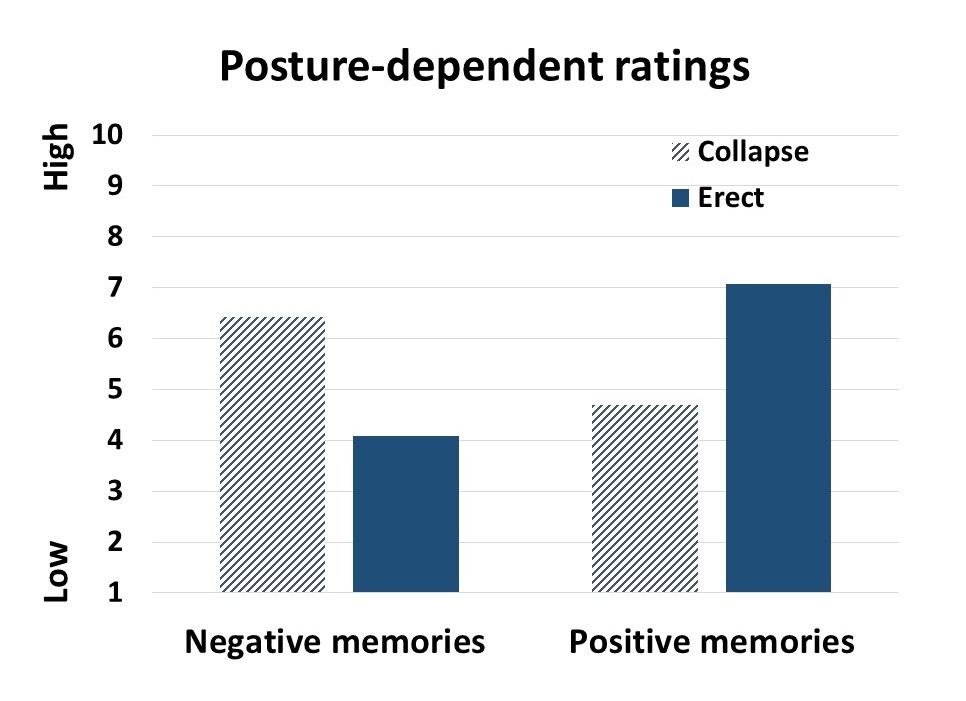

The difficulty or ease of recalling negative or positive memories varied depending on position as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. The relative subjective rating in the ease or difficulty of recalling negative and positive memories in collapsed and upright positions.

Figure 3. The relative subjective rating in the ease or difficulty of recalling negative and positive memories in collapsed and upright positions.

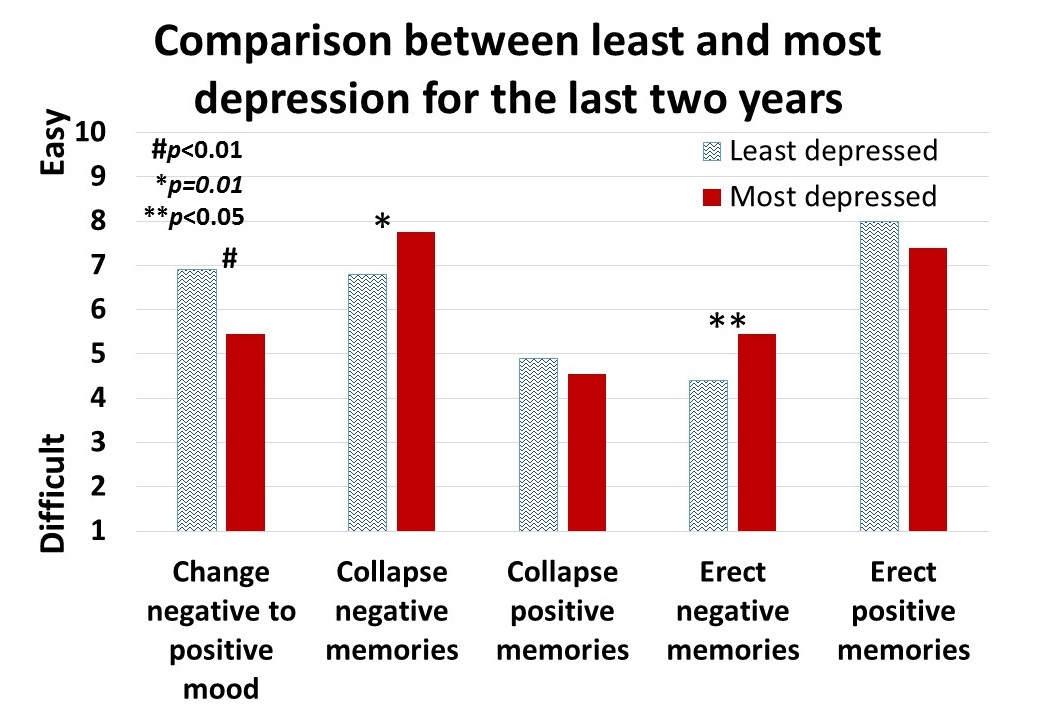

The participants with a high level of depression over the last two years (top 23% of participants who scored 7 or higher on the scale of 1–10) reported that it was significantly more difficult to change their mood from negative to positive (t(110) = 4.08, p < 0.01) than was reported by those with a low level of depression (lowest 29% of the participants who scored 3 or less on the scale of 1–10). It was significantly easier for more depressed students to recall/evoke negative memories in the collapsed posture (t(109) = 2.55, p = 0.01) and in the upright posture (t(110) = 2.41, p ≦0.05 he) and no significant difference in recalling positive memories in either posture, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Differences is in memory access for participants with a history of least or most depression.

Figure 4. Differences is in memory access for participants with a history of least or most depression.

For all participants, there was a significant correlation (r = 0.4) between subjective energy level and ease with which they could change from negative to positive mood. There were no significance differences for gender in all measures except that males reported a significantly higher energy level than females (M = 5.5, SD = 3.0 and M = 4.7, SD = 3.8, respectively; t(203) = 2.78, p < 0.01).

A subset of students also had rated their posture when sitting in front of a computer or using a digital device (tablet or cell phone) on a scale from 1 (upright) to 10 (completely slouched). The students with the highest levels of depression over the last two years reporting slouching significantly more than those with the lowest level of depression over the last two years (M = 6.4, SD = 3.5 and M = 4.6, SD = 2.6; t(46) = 3.5, p < 0.01).

There were no other order effects except of accessing fewer negative memories in the collapsed posture after accessing positive memories in the erect posture (t(159)=2.7, p < 0.01). Approximately half of the students who also rated being “captured” by their positive or negative memories were significantly more captured by the negative memories in the collapsed posture than in the erect posture (t(197) = 6.8, p < 0.01) and were significantly more captured by positive memories in the erect posture than the collapsed posture (t(197) = 7.6, p < 0.01), as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Subjective rating of being captured by negative and positive memories depending upon position.

Figure 5. Subjective rating of being captured by negative and positive memories depending upon position.

Discussion

Posture significantly influenced access to negative and positive memory recall and confirms the report by Wilson and Peper (2004). The collapsed/slouched position was associated with significantly easier access to negative memories. This is a useful clinical observation because ruminating on negative memories tends to decrease subjective energy and increase depressive feelings (Michi et al., 2015). When working with clients to change their cognition, especially in the treatment of depression, the posture may affect the outcome. Thus, therapists should consider posture retraining as a clinical intervention. This would include teaching clients to change their posture in the office and at home as a strategy to optimize access to positive memories and thereby reduce access or fixation on negative memories. Thus if one is in a negative mood, then slouching could maintain this negative mood while changing body posture to an erect posture, would make it easier to shift moods.

Physiologically, an erect body posture allows participants to breathe more diaphragmatically because the diaphragm has more space for descent. It is easier for participants to learn slower breathing and increased heart rate variability while sitting erect as compared to collapsed, as shown in Figure 6 (Mason et al., 2017).

Figure 6. Effect of posture on respiratory breathing pattern and heart rate variability.

Figure 6. Effect of posture on respiratory breathing pattern and heart rate variability.

The collapsed position also tends to increase neck and shoulder symptoms This position is often observed in people who work at the computer or are constantly looking at their cell phone—a position sometimes labeled as the i-Neck.

Implication for therapy

In most biofeedback and neurofeedback training sessions, posture is not assessed and clients sit in a comfortable chair, which automatically causes a slouched position. Similarly, at home, most clients sit on an easy chair or couch, which lets them slouch as they watch TV or surf the web. Finally, most people slouch when looking at their cellphone, tablet, or the computer screen (Guan et al., 2016). They usually only become aware of slouching when they experience neck, shoulder, or back discomfort.

Clients and therapists are usually not aware that a slouched posture may decrease the client’s energy level and increase the prevalence of a negative mood. Thus, we recommend that therapists incorporate posture awareness and training to optimize access to positive imagery and increase energy.

References

Singal, J. and Dahl, M. (2016, Sept 30 ) Here Is Amy Cuddy’s Response to Critiques of Her Power-Posing Research. https://www.thecut.com/2016/09/read-amy-cuddys-response-to-power-posing-critiques.html

We thank Frank Andrasik for his constructive comments.

Decrease procrastination! Increase productivity and energy!*

Posted: August 2, 2014 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: energy, mental rehearsal, procrastination, visualization 6 Comments“I felt more motivated to get things done.”

“After practicing this exercise for a week, my productivity significantly increased.”

“I felt more in control of my life in a fun way that made me feel successful.”

“Every time it increased my mood, confidence and energy levels.”

— Reports by participants after practicing “transforming failure into success”

Putting off something we set out to do can leave us feeling unproductive, drained of energy, and guilty. Procrastination can also contribute to dysphoria, depression, and self-recrimination. When people reflect on their own activity, they often using blaming language such as “I should not have done that,” “That was stupid,” or “What was I thinking.” The challenge is how to change this blaming language — through which the person continues to rehearse how they have failed — to positive and empowering language and images.

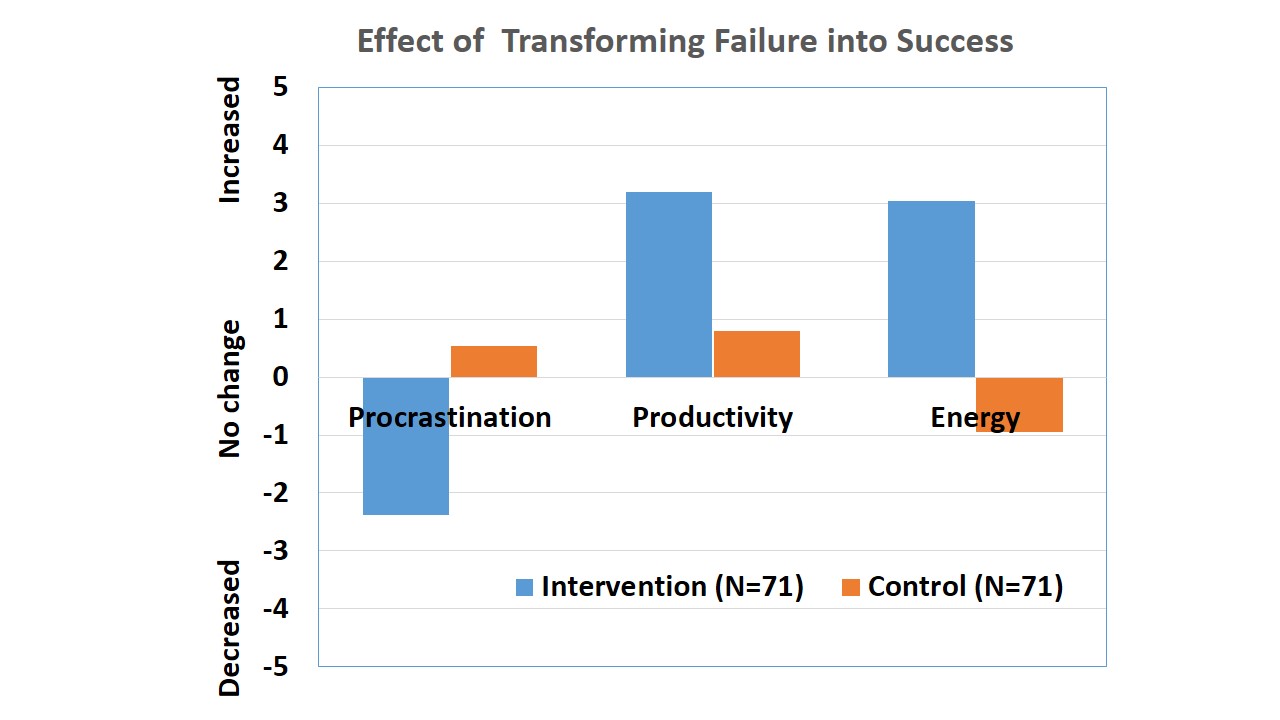

For many years, we have taught students a useful daily practice,Transforming Failure into Success, to transform the self-blame into optimizing performance. When the students as well as athletes practices this for a week, they report significant improvement in study habits, dealing with anger, and even sports performance. This year we systematically measured the effect of this practice and compared it to a control group. The students, just as previous athletes and clients, reported a significant decrease in procrastination and increase in productivity and energy as compared to the control group as shown in figure 1.

Figure 1. Change in self-report of procrastination, productivity and energy level. Reprinted from: Peper, E., Harvey, R., Lin, I-M, & Duvvuri, P. (2014). Increase productivity, decrease procrastination and increase energy. Biofeedback, 42(2), 82-87.

When we procrastinate or blame ourselves, we increase our chances of repeating that same behavior. We often forget that our ongoing thoughts and framing of past experiences become the template for our future behavior. It is easy to look back and criticize yourself for not having done something you feel you should have done, or having done something you later regretted doing. Unfortunately, this strategy only strengthens the memory of the mistake. The more you mentally rehearse/imagine yourself performing the desired (or undesired!) behavior, the more likely you will actually perform that behavior.

Thus the first step is to accept that what we actually did was the only thing we could have done given our history, training, maturity, and circumstances. The key is to rehearse what you would like to do or achieve. This practice is illustrated by a golfer who hits a ball into the pond. Instead of cursing himself and constantly repeating, “I should not have hit the ball into the pond,” the golfer acknowledges the problem and then asks , “What was the problem?” He then considers that he might not have hit the ball hard enough or that he might not have accounted for the cross winds. Or, he did not know the cause of the problem and needed to ask a consultant for suggestions. He decides that he did not account for the cross winds and then asks, “How could I have done it differently to get the outcome I wanted?” He then imagines exactly how hard and in what direction to hit the ball. He mentally rehearses the appropriate swing a number of times, each time seeing the ball landing on the green just a short putt away from the fifth hole. As he images this perfect swing, he feels it in his body. Later that day when his golfing partner asks him what happened when his ball went into the pond, he answers, “It went into the pond, and let me now tell you how I would hit it now.” Thus, the past error becomes the cue to rehearse the desired behavior.

Instructions for transforming failure into success

Each time when you observe yourself thinking, “I wish I’d done that differently,” Stop! Give yourself credit that you did the only thing you could have done and that you could NOT have done it any differently given your history, skills, and environmental factors at that moment. Accept what happened and recognize that you are now ready to explore new options. Next, breathe and relax, then ask yourself, “If I could do this over, how would I do it now given the new wisdom I have gained?” Then imagine yourself doing it in the new way.

Each time you observe an action which upon hindsight could have been improved, mentally rewrite how you would like to have behaved. Use the following five-step process:

- Think of a past conflict or area of behavior with which you are dissatisfied.

- Accept that it was the only way you could have done what you did under the circumstances.

- Ask, “Given the wisdom I have now, how could I have done this differently?”

- See yourself in that same situation but behaving differently, using the wisdom you now have (rehearse this step a number of times). When rehearsing, it is important to see and feel yourself completely immersed in the situation. Be very specific, and engage as many of the senses as you can.

- Smile and congratulate yourself for taking charge of programming your own future.

The more senses you invoke in your imagination and visualization, the more real the experience will feel and the more it will be become the new pattern. Imagine every small step, sensation, and thought—everything that would occur when you actually do the task. How you image the task is not important. Some people see it in living color while others only have a sense of it. Just take yourself through the new activity. Rewriting the past takes practice. During the mental rehearsal the old pattern often reasserts itself. Just let it go and practice again. If it continues to recur, ask yourself, “What do I need to learn from this; what is my lesson?”

This practice only applies to one’s own behavior–you can only change yourself. Remember that others have the freedom and the right to react in their own way. In your imagery, see yourself changing. Others may also change in their response to your change; however, they have the right NOT to change.

Finally, there are many settings in which we had no control and, regardless of our behaviors, nothing would be different (e.g., being abused as a young child). In such cases, the adaptive response is to acknowledge what happened, reaffirm that you are no longer the same person as when the experience occurred. Then take a deep breath and relax, and let go while knowing that this personal experience has taught you a set of coping skills that have nurtured your own growth and development.

This blog is adapted from our recent published article, Increase productivity, decrease procrastination and increase energy, which describes the background, methodology and research findings.

*Adapted from our published article: Peper, E., Harvey, R., Lin, I-M, & Duvvuri, P. (2014). Increase productivity, decrease procrastination and increase energy. Biofeedback, 42(2), 82-87.

Increase energy gains; decrease energy drains*

Posted: December 9, 2012 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: cancer, depression, energy 5 CommentsAre you full of pep and energy, ready to do more? Or do you feel drained and exhausted? After giving at the office, is there nothing left to give at home? Do you feel as if you are on a treadmill that will never stop, that more things feel draining than energizing?

Feeling chronically drained is often a precursor for illness and may contribute to errors; conversely, feeling energized enhances productivity and creativity and encourages health. An important aspect of staying healthy is that one’s daily activities are filled more with activities that contribute to our energy than with tasks and activities that drain our energy. Energy is the subjective sense of feeling alive and vibrant. An energy gain is an activity, task, or thought that makes you feel better and slightly more alive—those things we want to or choose to do. An energy drain is the opposite feeling—less alive and almost depressed—those things we have to or must do; often something that we do not want to do. Energy drains can be doing the dishes and feeling resentful that your partner or children are not doing them, or anticipating seeing a person whom you do not really want to see. An energy gain can be meeting a friend and talking or going for a walk in the woods, or finishing a work project. Energy drains and gains are always unique to the individual; namely, what is a drain for one can be a gain for another. The challenge is to identify your energy drains and gains and then explore strategies to decrease the drains and increase the gains. Use the following five step process to increase your energy:

- Monitor your energy drains and energy gains. Keep a log of events, activities, thoughts, or emotions that increase or decrease energy at home and at work.

- Identify common themes associated with energy drains and energy gains.

- Describe in behavioral detail how you will increase your energy gain and decrease the energy drains.

- Record your experiences on a daily log.

- After a week assess the impact of your practices.

1. Use the following chart to monitor your energy drains and gains at home and at work by using the following chart.

|

Energy Gains (Sources) |

Energy Drains |

2. Identify one energy gain that you will increase and one energy drain that you will decrease this week

|

Energy Gain (Source) |

Energy Drain |

3. Describe in detail how you will increase an energy gain and decrease an energy drain. Be so specific that it appears real and you can picture how, where, when, with whom, and under which situations you are performing it. Be sure to anticipate obstacles that may interfere with your plan and develop ways to overcome these obstacles.

Write out your detailed behavioral description for increasing an energy gain:

Write out your detailed behavioral description for decreasing an energy drain:

4. Record your experience on a daily log. By recording your experiences you can assess the efficacy of your changes.

- Day 1

- Day 2

- Day 3

- Day 4

- Day 5

- Day 6

- Day 7

5. After a week, review your daily log and ask yourself some of the following questions:

- What benefits occurred by increasing energy gains?

- What factors impeded increasing energy gains?

- What benefits occurred by decreasing energy drains?

- What factors impeded decreasing energy drains and how did you cope with that?

- What strategies did you use to remind yourself to decrease the energy drains and increase the energy gains?

- If you could have done the practice again, how would you have done it differently?

*Adapted from: Gorter, R. & Peper, E. (2011). Fighting Cancer-A Nontoxic Approach to Treatment. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books, 107-200.