What is normal may be habitual and not true for others

Posted: November 21, 2018 Filed under: behavior, health, Uncategorized Leave a commentThe pot roast parable/allegory reprinted from http://selfdefinedleadership.com/blog/

A young woman is preparing a pot roast while her friend looks on. She cuts off both ends of the roast, prepares it and puts it in the pan. “Why do you cut off the ends?” her friend asks. “I don’t know”, she replies. “My mother always did it that way and I learned how to cook it from her”.

Her friend’s question made her curious about her pot roast preparation. During her next visit home, she asked her mother, “How do you cook a pot roast?” Her mother proceeded to explain and added, “You cut off both ends, prepare it and put it in the pot and then in the oven”. “Why do you cut off the ends?” the daughter asked. Baffled, the mother offered, “That’s how my mother did it and I learned it from her!”

Her daughter’s inquiry made the mother think more about the pot roast preparation. When she next visited her mother in the nursing home, she asked, “Mom, how do you cook a pot roast?” The mother slowly answered, thinking between sentences. “Well, you prepare it with spices, cut off both ends and put it in the pot”. The mother asked, “But why do you cut off the ends?” The grandmother’s eyes sparkled as she remembered. “Well, the roasts were always bigger than the pot that we had back then. I had to cut off the ends to fit it into the pot that I owned”.

What we are used to is what we assume to be normal. Similarly, we interpret the results of scientific studies–often recorded from college students or white males–can be generalized to all people. We forget that what is “normal” may only be normal for this moment of time and specific location for western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic (WEIRD) people. Without being aware of our evolutionary past, without awareness how we evolved, and without asking questions, we accept cultural patterns and habits even though there may be other options. Enjoy the blog by Daniel Hruschka that was republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

You can’t characterize human nature if studies overlook 85 percent of people on Earth

Daniel Hruschka, Arizona State University ,

By only working in their own backyards, what do psychology researchers miss about human behavior? Over the last century, behavioral researchers have revealed the biases and prejudices that shape how people see the world and the carrots and sticks that influence our daily actions. Their discoveries have filled psychology textbooks and inspired generations of students. They’ve also informed how businesses manage their employees, how educators develop new curricula and how political campaigns persuade and motivate voters.

But a growing body of research has raised concerns that many of these discoveries suffer from severe biases of their own. Specifically, the vast majority of what we know about human psychology and behavior comes from studies conducted with a narrow slice of humanity – college students, middle-class respondents living near universities and highly educated residents of wealthy, industrialized and democratic nations.

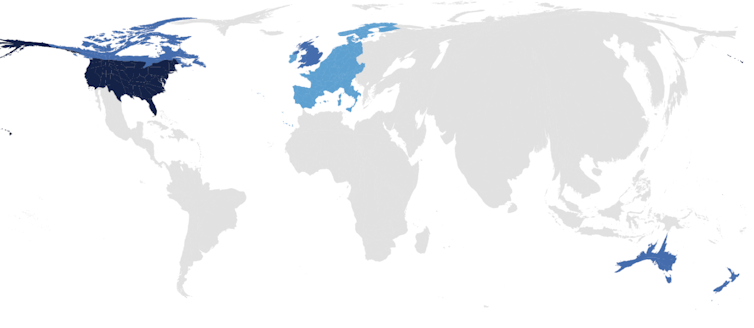

To illustrate the extent of this bias, consider that more than 90 percent of studies recently published in psychological science’s flagship journal come from countries representing less than 15 percent of the world’s population.

If people thought and behaved in basically the same ways worldwide, selective attention to these typical participants would not be a problem. Unfortunately, in those rare cases where researchers have reached out to a broader range of humanity, they frequently find that the “usual suspects” most often included as participants in psychology studies are actually outliers. They stand apart from the vast majority of humanity in things like how they divvy up windfalls with strangers, how they reason about moral dilemmas and how they perceive optical illusions.

Given that these typical participants are often outliers, many scholars now describe them and the findings associated with them using the acronym WEIRD, for Western, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic.

WEIRD isn’t universal

Because so little research has been conducted outside this narrow set of typical participants, anthropologists like me cannot be sure how pervasive or consequential the problem is. A growing body of case studies suggests, though, that assuming such typical participants are the norm worldwide is not only scientifically suspect but can also have practical consequences.

Daniel Hruschka, CC BY-ND

Consider an apparently simple pattern recognition test commonly used to assess the cognitive abilities of children. A standard item consists of a sequence of two-dimensional shapes – squares, circles and triangles – with a missing space. A child is asked to complete the sequence by choosing the appropriate shape for the missing space.

When 2,711 Zambian schoolchildren completed this task in one recent study, only 12.5 percent correctly filled in more than half of shape sequences they were shown. But when the same task was given with familiar three-dimensional objects – things like toothpicks, stones, beans and beads – nearly three times as many children achieved this goal (34.9 percent). The task was aimed at recognizing patterns, not the ability to manipulate unfamiliar two-dimensional shapes. The use of a culturally foreign tool dramatically underestimated the abilities of these children.

Misplaced assumptions about what is “normal” might also affect the very methods scientists use to assess their theories. For example, one of the most commonly used tools in the behavioral sciences involves presenting a participant with a statement – something like “I generally trust people.” Then participants are asked to choose one point along a five- or seven-point line ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree. This numbered line is named a “Likert item” after its social psychologist originator, Rensis Likert.

Likert Scales are commonly used to collect opinions and reactions.

Nicholas Smith/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

Most readers of this article have likely responded to many Likert items in their lifetime, but when this tool is taken to other settings it encounters varying success. Some people may refuse to answer. Others prefer to answer simply yes or no. Sometimes they respond with no difficulty.

If something as apparently simple and normal as a Likert item fails in different contexts (and not in others), it raises serious questions about our most basic models of how people should perceive and respond to stimuli.

Aiming for a science of all humanity

To address these potentially vast gaps in our understanding of human psychology and behavior, researchers have proposed a number of solutions. One is to reward researchers who take the time and effort to build long-term research relationships with diverse communities. Another is to recruit and retain behavioral scientists from diverse backgrounds and perspectives. Still another is to pay closer attention to the norms, values and beliefs of study communities, whether they are WEIRD or not, when interpreting results.

A key part of these efforts will be to go beyond theories of “universal humans” and build theories that make predictions about how the local culture and environment can shape all aspects of human behavior and psychology. These include theories of how trading in markets can make people treat strangers more fairly, how some societies became WEIRD in recent centuries, and how the number of personality traits we find in a society – such as agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism – depends on the complexity of a society’s organization.

Proponents disagree on the best paths to moving beyond WEIRD science to building a science of all humanity. But hopefully some combination of these solutions will expand our understanding of both what makes us human and what creates such remarkable diversity in the human experience.![]()

Daniel Hruschka, Professor and Associate Director of the School of Human Evolution and Social Change , Arizona State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Biofeedback, breathing and health

Posted: November 17, 2018 Filed under: Breathing/respiration, emotions, health, mindfulness, posture, relaxation, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: resentment 2 CommentsIn the video interview recorded at the 2018 Conference of the New Psychology Association, Jagiellonian University, Krakow, Poland, Erik Peper, PdD, defines biofeedback and suggests three simple breathing and imagery approaches that we can all apply to reduce pain, resentment and improve well-being.

Cell phone radio frequency radiation increases cancer risk*

Posted: November 12, 2018 Filed under: cancer, digital devices, self-healing, Uncategorized | Tags: cellphones, digital devices, Radio frequency radiation, technology 3 CommentsBe safe rather than sorry. Cellphone radio frequency radiation is harmful!

The National Toxicology Program (NTP) released on October 31, 2018 their final report on rat and mouse studies of radio frequency radiation like that used with cellphones. The $30 million NTP studies took more than 10 years to complete and are the most comprehensive assessments to date of health effects in animals exposed to Radio Frequency Radiation (RFR) with modulations used in 2G and 3G cell phones. 2G and 3G networks were standard when the studies were designed and are still used for phone calls and texting.

The report concluded there is clear evidence that male rats exposed to high levels of radio frequency radiation (RFR) like that used in 2G and 3G cell phones developed cancerous heart tumors, according to final reports. There was also some evidence of tumors in the brain and adrenal gland of exposed male rats. For female rats, and male and female mice, the evidence was equivocal as to whether cancers observed were associated with exposure to RFR.

“The exposures used in the studies cannot be compared directly to the exposure that humans experience when using a cell phone,” said John Bucher, Ph.D., NTP senior scientist. “In our studies, rats and mice received radio frequency radiation across their whole bodies. By contrast, people are mostly exposed in specific local tissues close to where they hold the phone. In addition, the exposure levels and durations in our studies were greater than what people experience.”

In the NTP study, the lowest exposure level used in the studies was equal to the maximum local tissue exposure currently allowed for cell phone users. This power level rarely occurs with typical cell phone use. The highest exposure level in the studies was four times higher than the maximum power level permitted. Butcher state, “We believe that the link between radio frequency radiation and tumors in male rats is real, and the external experts agreed.”

I interpret that their results support the previous–often contested–observations that brain cancers were more prevalent in high cell phone users especially on the side of the head they held the cellphone.

More some women who have habitually stashed their cell phone in their bra have been diagnosed with a rare breast cancer located beneath the area of the breast where they stored their cell phone. Watch the heart breaking TV interview with Tiffany. She was 21 years old when she developed breast cancer which was located right beneath the breast were she had kept her cell phone against her bare skin for the last 6 years.

While these rare cases could have occurred by chance, they could also be an early indicator of risk. Previously, most research studies were based upon older adults who have tended to use their mobile phone much less than most young people today. The average age a person acquires a mobile phone is ten years old (this data was from 2016 and many children now have cellphones even earlier). Often infants and toddlers are entertained by smartphones and tablets–the new technological babysitter. The possible risk may be much greater for a young people since their bodies and brains are still growing rapidly. I wonder if the antenna radiation may be one of the many initiators or promoters of later onset cancers. We will not know the answer; since, most cancer take twenty or more years to develop.

What can you do to reduce risk?

Act now and reduce the exposure to the antenna radiation by implementing the following suggestions:

- Keep your phone, tablet or laptop in your purse, backpack or briefcase. Do not keep it on or close to your body.

- Use the speakerphone or earphones with microphone while talking. Do not hold it against the side of your head, close to your breast or on your lap.

- Text while the phone is on a book or on a table away from your body.

- Put the tablet and laptop on a table and away from the genitals.

- Set the phone to airplane mode.

- Be old fashioned and use a cable to connect to your home router instead of relying on the WiFi connection.

- Keep your calls short and enjoy the people in person.

- Support legislation to label wireless devices with a legible statement of possible risk and the specific absorption rate (SAR) value. Generally, higher the SAR value, the higher the exposure to antenna radiation.

- Support the work by the Environmental Health Trust.

For an radio interview on this topic, listen to my interview on Deborah Quilter’s radio show. http://www.blogtalkradio.com/rsihelp/2018/11/20/why-you-should-keep-your-cell-phone-away-from-your-body-with-dr-erik-peper

For more information on NTP study see:

*The blog is adapted in part from the November 1, 2018 news release from the National Toxicology Program (NTP)1, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences2, National Institute of Health (NIH)3.

- About the National Toxicology Program (NTP):NTP is a federal, interagency program headquartered at NIEHS, whose goal is to safeguard the public by identifying substances in the environment that may affect human health. For more information about NTP and its programs, visit niehs.nih.gov.

- About the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS): NIEHS supports research to understand the effects of the environment on human health and is part of NIH. For more information on environmental health topics, visit niehs.nih.gov. Subscribe to one or more of the NIEHS news lists (www.niehs.nih.gov/news/newsroom/newslist/index.cfm) to stay current on NIEHS news, press releases, grant opportunities, training, events, and publications.

- About the National Institutes of Health (NIH):NIH, the nation’s medical research agency, includes 27 Institutes and Centers and is a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NIH is the primary federal agency conducting and supporting basic, clinical, and translational medical research, and is investigating the causes, treatments, and cures for both common and rare diseases. For more information about NIH and its programs, visit nih.gov.