TechStress: Building Healthier Computer Habits

Posted: August 30, 2023 Filed under: ADHD, behavior, biofeedback, Breathing/respiration, cognitive behavior therapy, computer, digital devices, education, emotions, ergonomics, Evolutionary perspective, Exercise/movement, health, laptops, Neck and shoulder discomfort, Pain/discomfort, posture, screen fatigue, stress management, Uncategorized, vision, zoom fatigue | Tags: cellphone, fatigue, gaming, mobile devices, screens 2 CommentsBy Erik Peper, PhD, BCB, Richard Harvey, PhD, and Nancy Faass, MSW, MPH

Adapted by the Well Being Journal, 32(4), 30-35. from the book, TechStress: How Technology is Hijacking Our Lives, Strategies for Coping, and Pragmatic Ergonomics by Erik Peper, Richard Harvey, and Nancy Faass.

Every year, millions of office workers in the United States develop occupational injuries from poor computer habits—from carpal tunnel syndrome and tension headaches to repetitive strain injury, such as “mouse shoulder.” You’d think that an office job would be safer than factory work, but the truth is that many of these conditions are associated with a deskbound workstyle.

Back problems are not simply an issue for workers doing physical labor. Currently, the people at greatest risk of injury are those with a desk job earning over $70,000 annually. Globally, computer-related disorders continue to be on the rise. These conditions can affect people of all ages who spend long hours at a computer and digital devices.

In a large survey of high school students, eighty-five percent experienced tension or pain in their neck, shoulders, back, or wrists after working at the computer. We’re just not designed to sit at a computer all day.

Field of Ergonomics

For the past twenty years, teams of researchers all over the world have been evaluating workplace stress and computer injuries—and how to prevent them. As researchers in the fields of holistic health and ergonomics, we observe how people interact with technology. What makes our work unique is that we assess employees not only by interviewing them and observing behaviors, but also by monitoring physical responses.

Specifically, we measure muscle tension and breathing, in the moment, in real-time, while they work. To record shoulder pain, for example, we place small sensors over different muscles and painlessly measure the muscle tension using an EMG (electromyograph)—a device that is employed by physicians, physical therapists, and researchers. Using this device, we can also keep a record of their responses and compare their reactions over time to determine progress.

What we’ve learned is that people get into trouble if their muscles are held in tension for too long. Working at a computer, especially at a stationary desk, most people maintain low-level chronic tension for much of the day. Shallow, rapid breathing is also typical of fine motor tasks that require concentration, like data entry.

Muscle tension and breathing rate usually increase during data entry or typing without our awareness.

When these patterns are paired with psychological pressure due to office politics or job insecurity, the level of tension and the risk of fatigue, inflammation, pain, or injury increase. In most cases, people are totally unaware of the role that tension plays in injury. Of note, the absolute level of tension does not predict injury—rather, it is the absence of periodic rest breaks throughout the day that seems to correlate with future injuries.

Restbreaks

All of life is the alternation between movement and rest, inhaling and exhaling, sleeping and waking. Performing alternating tasks or different types of activities and movement is one way to interrupt the couch potato syndrome—honoring our evolutionary background.

Our research has confirmed what others have observed: that it’s important to be physically active, at least periodically, throughout the day. Alternating activity and rest recreate the pattern of our ancestors’ daily lives. When we alternate sedentary tasks with physical activity, and follow work with relaxation, we function much more efficiently. In short, move your body more.

Better Computer Habits: Alternate Periods of Rest and Activity

As mentioned earlier, our workstyle puts us out of sync with our genetic heritage. Whether hunting and gathering or building and harvesting, our ancestors alternated periods of inactivity with physical tasks that required walking, running, jumping, climbing, digging, lifting, and carrying, to name a few activities. In contrast, today many of us have a workstyle that is so immobile we may not even leave our desk for lunch.

As health researchers, we have had the chance to study workstyles all over the world. Back pain and strain injuries now affect a large proportion of office workers in the US and in high-tech firms worldwide. The vast majority of these jobs are sedentary, so one focus of the research is on how to achieve a more balanced way of working.

A recent study on exercise looked at blood flow to the brain. Researchers Carter and colleagues found that if people sit for four hours on the job, there’s a significant decrease in blood flow to the brain. However, if every thirty or forty minutes they get up and move around for just two minutes, then brain blood flow remains steady. The more often you interrupt sitting with movement, the better.

It may seem obvious that to stay healthy, it’s important to take breaks and be physically active from time to time throughout the day. Alternating activity and rest recreate the pattern of our ancestors’ daily lives. The goal is to alternate sedentary tasks with physical activity and follow work with relaxation. When we keep this type of balance going, most people find that they have more energy, are more productive, and can be more effective.

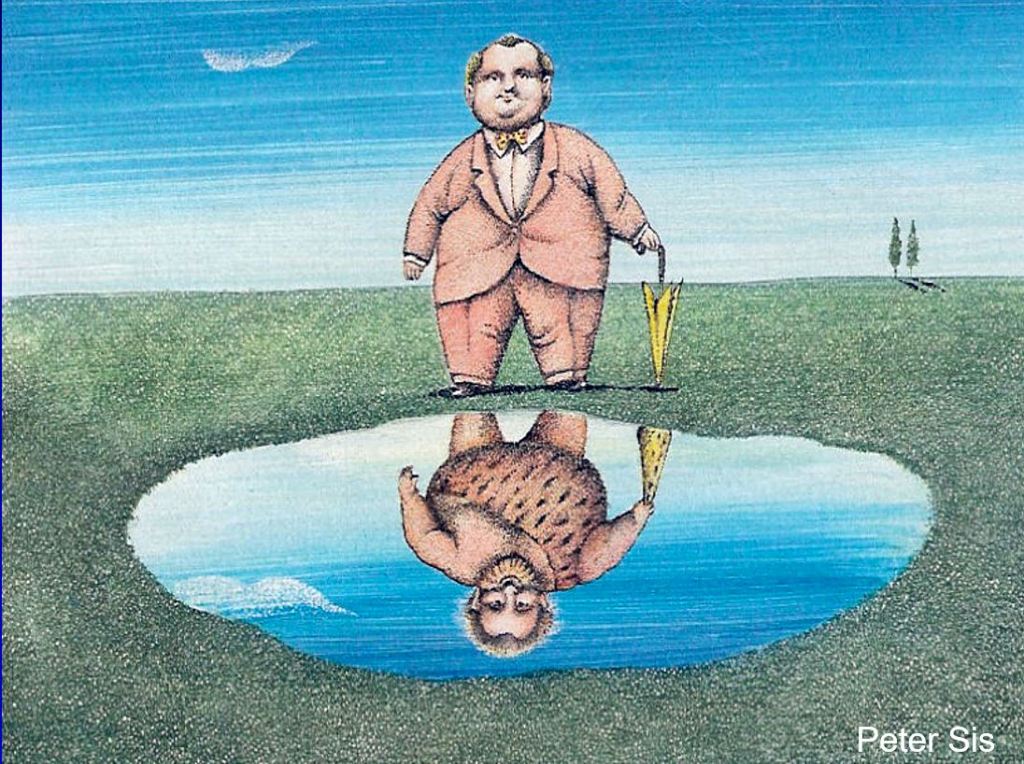

Genetics: We’re Hardwired Like Ancient Hunters

Despite a modern appearance, we carry the genes of our forebearers—for better and for worse. (Art courtesy of Peter Sis). Reproduced from Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Faass (2020). TechStress: How Technology is Hijacking Our Lives, Strategies for Coping, and Pragmatic Ergonomics. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books.

In the modern workplace, most of us find ourselves working indoors, in small office spaces, often sitting at a computer for hours at a time. In fact, the average Westerner spends more than nine hours per day sitting indoors, yet we’re still genetically programmed to be physically active and spend time outside in the sunlight most of the day, like the nomadic hunters and gatherers of forty thousand years ago.

Undeniably, we inherently conserve energy in order to heal and regenerate. This aspect of our genetic makeup also helps burn fewer calories when food is scarce. Hence the propensity for lack of movement and sedentary lifestyle (sitting disease).

In times of famine, the habit of sitting was essential because it reduced calorie expenditure, so it enabled our ancestors to survive. In a prehistoric world with a limited food supply, less movement meant fewer calories burned. Early humans became active when they needed to search for food or shelter. Today, in a world where food and shelter are abundant for most Westerners, there is no intrinsic drive to initiate movement.

It is also true that we have survived as a species by staying active. Chronic sitting is the opposite of our evolutionary pattern in which our ancestors alternated frequent movement while hunting or gathering food with periods of rest. Whether they were hunters or farmers, movement has always been an integral aspect of daily life. In contrast, working at the computer—maintaining static posture for hours on end—can increase fatigue, muscle tension, back strain, and poor circulation, putting us at risk of injury.

Quit a Sedentary Workstyle

Almost everyone is surprised by how quickly tension can build up in a muscle, and how painful it can become. For example, we tend to hover our hands over the keyboard without providing a chance for them to relax. Similarly, we may tighten some of the big muscles of our body, such as bracing or crossing our legs.

What’s needed is a chance to move a little every few minutes—we can achieve this right where we sit by developing the habit of microbreaks. Without regular movement, our muscles can become stiff and uncomfortable. When we don’t take breaks from static muscle tension, our muscles don’t have a chance to regenerate and circulate oxygen and necessary nutrients.

Build a variety of breaks into your workday:

- Vary work tasks

- Take microbreaks (brief breaks of less than thirty seconds)

- Take one-minute stretch breaks

- Fit in a moving break

Varying Work Tasks

You can boost physical activity at work by intentionally leaving your phone on the other side of the desk, situating the printer across the room, or using a sit-stand desk for part of the day. Even a few minutes away from the desk makes a difference, whether you are hand delivering documents, taking the long way to the bathroom, or pacing the room while on a call.

When you alternate the types of tasks and movement you do, using a different set of muscles, this interrupts the contractions of muscle fibers and allows them to relax and regenerate. Try any of these strategies:

- Alternate computer work with other activities, such as offering to do a coffee run

- Schedule walking meetings with coworkers

- Vary keyboarding and hand movements

Ultimately, vary your activities and movements as much as possible. By changing your posture and making sure you move, you’ll find that your circulation and your energy improve, and you’ll experience fewer aches and pains. In a short time, it usually becomes second nature to vary your activities throughout the day.

Experience It: “Mouse Shoulder” Test

You can test this simple mousing exercise at the computer or as a simulation. If you’re at the computer, sit erect with your hand on the mouse next to the keyboard. To simulate the exercise, sit with erect posture as if you were in front of your computer and hold a small object you can use to imitate mousing.

With the mouse (or a sham mouse), simulate drawing the letters of your name and your street address, right to left. Be sure each letter is very small (less than half an inch in height). After drawing each letter, click the mouse.

As part of the exercise, draw the letters and numbers as quickly as possible for ten to fifteen seconds. What did you observe? In almost all cases, you may note that you tightened your mousing shoulder and your neck, stiffened your trunk, and held your breath. All this occurred without awareness while performing the task. Over time, this type of muscle tension can contribute to discomfort, soreness, pain, or eventual injury.

Microbreaks

If you’ve developed an injury—or have chronic aches and pains—you’ll probably find split-second microbreaks invaluable. A microbreak means taking brief periods of time that last just a few seconds to relax the tension in your wrists, shoulders, and neck.

For example, when typing, simply letting your wrists drop to your lap for a few seconds will allow the circulation to return fully to help regenerate the muscles. The goal is to develop a habit that is part of your routine and becomes automatic, like driving a car. To make the habit of microbreaks practical, think about how you can build the breaks into your workstyle. That could mean a brief pause after you’ve completed a task, entered a column of data, or before starting typing out an assignment.

For frequent microbreaks, you don’t even need to get up—just drop your hands in your lap or shake them out, move your shoulders, and then resume work. Any type of shaking or wiggling movement is good for your circulation and kind of fun.

In general, a microbreak may be defined as lasting one to thirty seconds. A minibreak may last roughly thirty seconds to a few minutes, and longer large-movement breaks are usually greater than a few minutes. Popular microbreaks:

- Take a few deep breaths

- Pause to take a sip of water

- Rest your hands in your lap

- Stretch

- Let your arms drop to your sides

- Shake out your hands (wrists and fingers)

- Perform a quick shoulder or neck roll

Often, we don’t realize how much tension we’ve been carrying until we become more mindful of it. We can raise our awareness of excess tension—this is a learned skill—and train ourselves to let go of excess muscle tension. As we increase our awareness, we’re able to develop a new, more dynamic workstyle that better fits our goals and schedule.

One-Minute Stretch Breaks

We all benefit from a brief break, even with the best of posture (left). One approach is to totally release your muscles (middle). That release can be paired with a series of brief stretches (right). Reproduced from Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Faass (2020). TechStress: How Technology is Hijacking Our Lives, Strategies for Coping, and Pragmatic Ergonomics. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books.

The typical mini-stretch break lasts from thirty seconds to a few minutes, and ideally you want to take them several times per hour. Similar to microbreaks, mini-stretch breaks are especially important for people with an injury or those at risk of injury. Taking breaks is vital, especially if you have symptoms related to computer stress or whenever you’re working long hours at a sedentary job. To take a stretch break:

Begin with a big stretch, for example, by reaching high over your head then drop your hands in your lap or to your sides.

Look away from the monitor, staring at near and far objects, and blink several times. Straighten your back and stretch your entire backbone by lifting your head and neck gently, as if there were an invisible string attached to the crown of your head.

Stretch your mind and body. Sitting with your back straight and both feet flat on the floor, close your eyes and listen to the sounds around you, including the fan on the computer, footsteps in the hallway, or the sounds in the street.

Breathe in and out over ten seconds (breathe in for four or five seconds and breathe out for five or six seconds), making the exhale slightly longer than the inhale. Feel your jaw, mouth, and tongue muscles relax. Feel the back and bottom of the chair as your body breathes all around you. Envision someone in your mind’s eye who is kind and reassuring, who makes you feel safe and loved, and who can bring a smile to your face inwardly or outwardly.

Do a wiggling movement. When you take a one-minute break, wiggling exercises are fast and easy, and especially good for muscle tension or wrist pain. Wiggle all over—it feels good, and it’s also a great way to improve circulation.

Building Exercise and Movement into Every Day

Studies show that you get more benefit from exercising ten to twenty minutes, three times a day, than from exercising for thirty to sixty minutes once a day. The implication is that doing physical activities for even a few minutes can make a big difference.

Dunstan and colleagues have found that standing up three times an hour and then walking for just two minutes reduced blood sugar and insulin spikes by twenty-five percent.Fit in a Moving Break

Fit in a Moving Break

Once we become conscious of muscle tension, we may be able to reverse it simply by stepping away from the desk for a few minutes, and also by taking brief breaks more often. Explore ways to walk in the morning, during lunch break, or right after work. Ideally, you also want to get up and move around for about five minutes every hour.

Ultimately, research makes it clear that intermittent movement, such as brief, frequent stretching throughout the day or using the stairs rather than elevator, is more beneficial than cramming in a couple of hours at the gym on the weekend. This explains why small changes can have a big impact—it’s simply a matter of reminding yourself that it’s worth the effort.

Workstation Tips

Your ability to see the display and read the screen is key to reducing neck and eye strain. Here are a few strategic factors to remember:

Monitor height: Adjust the height of your monitor so the top is at eyebrow level, so you can look straight ahead at the screen.

Keyboard height: The keyboard height should be set so that your upper arms hang straight down while your elbows are bent at a 90-degree angle (like the letter L) with your forearms and wrists held horizontally.

Typeface and font size: For email, word processing, or web content, consider using a sans serif typeface. Fonts that have fewer curved lines and flourishes (serifs) tend to be more readable on screen.

Checking your vision: Many adults benefit from computer glasses to see the screen more clearly. Generally, we do not recommend reading glasses, bifocals, trifocals, and progressive lenses as they tend to allow clear vision at only one focal length. To see through the near-distance correction of the lens requires you to tilt your head back. Although progressive lenses allow you to see both close up and at a distance, the segment of the lens for each focal length is usually too narrow for working at the computer.

Wearing progressive lenses requires you to hold your head in a fixed position to be in focus. Yet you may be totally unaware that you are adapting your eye and head movements to sustain your focus. When that is the case, most people find that special computer glasses are a good solution.

Consider computer glasses if you must either bring your nose to the screen to read the text, wear reading glasses and find that their focal length is inappropriate for the monitor distance, wear bi- or trifocal glasses, or are older than forty.

Computer glasses correct for the appropriate focal distance to the computer. Typically, monitor distance is about twenty-three to twenty-eight inches, whereas reading glasses correct for a focal length of about fifteen inches. To determine your individual, specific focal length, ask a coworker to measure the distance from the monitor to your eyes. Provide this personal focal distance at the eye exam with your optometrist or ophthalmologist and request that your computer glasses be optimized for that distance.

Remembering to blink: As we focus on the screen, our blinking rate is significantly reduced. Develop the habit of blinking periodically: at the end of a paragraph, for example, or when sending an email.

Resting your eyes: Throughout the day, pause and focus on the far distance to relax your eyes. When looking at the screen, your eyes converge, which can cause eyestrain. Each time you look away and refocus, that allows your eyes to relax. It’s especially soothing to look at green objects such as a tree that can be seen through a window.

Minimizing glare: If the room is lit with artificial light, there may be glare from your light source if the light is right in front of you or right behind you, causing reflection on your screen. Reflection problems are minimized when light sources are at a 90-degree angle to the monitor (with the light coming from the side). The worst situations occur when the light source is either behind or in front of you.

An easy test is to turn off your monitor and look for reflections on the screen. Everything that you see on the monitor when it’s turned off is there when you’re working at the monitor. If there are bright reflections, they will interfere with your vision. Once you’ve identified the source of the glare, change the location of the reflected objects or light sources, or change the location of the monitor.

Contrast: Adjust the light contrast in the room so that it is neither too bright nor too dark. If the room is dark, turn on the lights. If it is too bright, close the blinds or turn off the lights. It is exhausting for your eyes to have to adapt from bright outdoor light to the lighting of your computer screen. You want the light intensity of the screen to be somewhat similar to that in the room where you’re working. You also do not want to look from your screen to a window lit by intense sunlight.

Don’t look down at phone: According to Kenneth Hansraj, MD, chief of spine surgery at New York Spine Surgery and Rehabilitation Medicine, pressure on the spine increases from about ten pounds when you are holding your head erect, to sixty pounds of pressure when you are looking down. Bending forward to look at your phone, your head moves out of the line of gravity and is no longer balanced above your neck and spine. As the angle of the face-forward position increases, this intensifies strain on the neck muscles, nerves, and bones (the vertebrae).

The more you bend your neck, the greater the stress since the muscles must stretch farther and work harder to hold your head up against gravity. This same collapsed head-forward position when you are seated and using the phone repeats the neck and shoulder strain. Muscle strain, tension headaches, or neck pain can result from awkward posture with texting, craning over a tablet (sometimes referred to as the iPad neck), or spending long hours on a laptop.

A face-forward position puts as much as sixty pounds of pressure on the neck muscles and spine.

Repetitive strain of neck vertebrae (the cervical spine), in combination with poor posture, can trigger a neuromuscular syndrome sometimes diagnosed as thoracic outlet syndrome. According to researchers Sharan and colleagues, this syndrome can also result in chronic neck pain, depression, and anxiety.

When you notice negative changes in your mood or energy, or tension in your neck and shoulders, use that as a cue to arch your back and look upward. Think of a positive memory, take a mindful breath, wiggle, or shake out your shoulders if you’d like, and return to the task at hand.

Strengthen your core: If you find it difficult to maintain good posture, you may need to strengthen your core muscles. Fitness and sports that are beneficial for core strength include walking, sprinting, yoga, plank, swimming, and rowing. The most effective way to strengthen your core is through activities that you enjoy.

Final Thoughts

If these ideas resonate with you, consider lifestyle as the first step. We need to build dynamic physical activity into our lives, as well as the lives of our children. Being outside is usually an uplift, so choose to move your body in natural settings whenever possible, whatever form that takes. Being outside is the factor that adds an energetic dimension. Finally, share what you learn, and help others learn and grow from your experiences.

If you spend time in front of a computeror using a mobile device, read the book, TechStress: How Technology is Hijacking Our Lives, Strategies for Coping, and Pragmatic Ergonomics. It provides practical, easy-to-use solutions for combating the stress and pain many of us experience due to technology use and overuse. The book offers extremely helpful tips for ergonomic use of technology, it

goes way beyond that, offering simple suggestions for improving muscle health that seem obvious once you read them, but would not have thought of yourself: “Why didn’t I think of that?” You will learn about the connection between posture and mood, reasons for and importance of movement breaks, specific movements you can easily perform at your desk, as well as healthier ways to utilize technology in your everyday life.

Additional resources

Healing a Shoulder/Chest Injury

Posted: August 14, 2023 Filed under: behavior, biofeedback, Breathing/respiration, emotions, Exercise/movement, healing, Neck and shoulder discomfort, Pain/discomfort, relaxation, self-healing, Uncategorized | Tags: electromyograph, guided imagery, shoulder pain Leave a commentAdapted from Peper, E. & Fuhs, M. (2004). Applied psychophysiology for therapeutic use: Healing a shoulder injury, Biofeedback, 32(2), 11-18.

“It has been an occurrence of the third dimension for me! How come my pain — that lasted for more than 10 days and was still so strong that I really had difficulties in breathing, couldn’t laugh without pain nor move my arm not even to fulfil my daily routines such as dressing and eating — disappeared within one single session of 20 minutes? And not only that, I was able to freely rotate my arm as if it had never been injured before.” —23 year old woman

The participant T., aged 23, was a psychology student who participated in an educational workshop for Healthy Computing. She volunteered to be a subject for a surface electromyographic (SEMG) monitoring and feedback demonstration. Ten days prior to this workshop, she had a severe skiing accident. She described the accident as follows:

I went skiing and may be I had too much snow in my ski-binding and while turning, I slipped out of my binding and fell head first down into the hill. As I fell, I landed on my ski pole which hit my left upper chest and breast area. Afterwards, my head was humming and I assumed that I had a light concussion. I stopped skiing and stayed in bed for a while. The next day it started hurting and I couldn’t turn my head or put my shoulders back (they were rotated forward). Also, I couldn’t ski as I was not able to look down to my feet–my muscles were too contracted and I felt searing pain whenever I moved. I hoped that it would go away however, the pain and left forward shoulder rotation stayed.

Assessment

Observation and Palpation

T.´s left shoulder was rolled forward (adducted and in internal rotation). She was not able to breathe or laugh without pain or move her arm freely. All movements in vertical and horizontal directions and rotations were restricted by at least 50 % as compared to her right arm (limitations in shoulder extension, flexion and external rotation). Also, her hands were ice-cold and she breathed very shallowly and rapidly in her chest. She was not able to stand in an upright position or sit in a comfortable position without maintaining her left upper extremity in a protected position. Her left shoulder blade (scapula) was winging.

After visually observing her, the instructor placed his left hand on her left shoulder and pectoralis muscles and his right hand on the back of her shoulder. Using palpation and anchoring her back with his leg so that she could not rotate her trunk, he explored the existing range of shoulder movement. He also attempted to rotate the left shoulder outward and back–not by forcing or pulling—but by very gentle traction. No change in mobility was observed and the pectoralis muscle felt tight (SEMG monitoring is helpful to the therapist during such a diagnostic assessment by helping to identify the person’s reactivity and avoiding to evoke and condition even more bracing). T. reported afterwards that she was very scared by this assessment because there was one point in the back which was highly reactive to touch. T. appeared to tighten automatically out of fear and trigger a general flexor contraction pattern—a process that commonly occurs if a person is guarding an area.

Often a traumatic injury first induces a general shock that triggers an automatic freeze and fear reaction. Therefore, an intervention needed to be developed that did not trigger vigilance or fear and thereby allowed the muscle to relax. If pain is experienced or increased, it is another negative reinforcement for generalizing guarding and bracing and tightening the muscles. This guarding decreases mobility – a common reaction that may occur when health professionals in the process of assessment increase the client’s discomfort. T.’s vigilance was also “telegraphed” to the therapist by her ice-cold hands and very shallow chest breathing. Therefore, it was important to increase her comfort level and to not induce any further pain. We hypothesized that only if she felt safe it would be possible for her muscle tension to decrease and thereby increase her mobility.

Underlying concept: The very cold hands and shallow breathing probably indicated excessive vigilance and arousal—a possible indicator of a catabolic state that could limit regeneration. The chronic cold hands most likely implied that she was very sensitive to other people’s emotions and continuously searches/scans the environment for threats. In addition, she indicated that she liked to do/perform her best which induced more anxiety and fear of judgement.

Single Channel Surface Electromyographic (SEMG)Assessment

The triode electrode with sensor was placed over the left pectoralis muscle area as shown in Figure 1. The equipment was a MyoTrac™ produced by Thought Technology Ltd. which is a small portable SEMG with the preamplifiers at the triode sensor to eliminate electrode lead and movement artefacts (Peper & Gibney, 2006). Such a device is an inexpensive option for people who may use biofeedback for demonstrating and teaching awareness and control over muscle tension from a single electrode location.

Figure 1. Location of the Triode electrode placement on the left pectoralis muscle area of another participant.

The MyoTrac was placed on a table within view, so that the therapist and the subject could simultaneously see the visual feedback signal and observe what was going on as well as demonstrate expected changes. The feedback was used for T. as a tool to see if she could reduce her SEMG activity. It was also used by the therapist to guide his interventions: To keep the SEMG activity low and to stop any intervention that would increase the SEMG activity as this would prevent bracing as a possible reaction to, or anticipation of, pain.

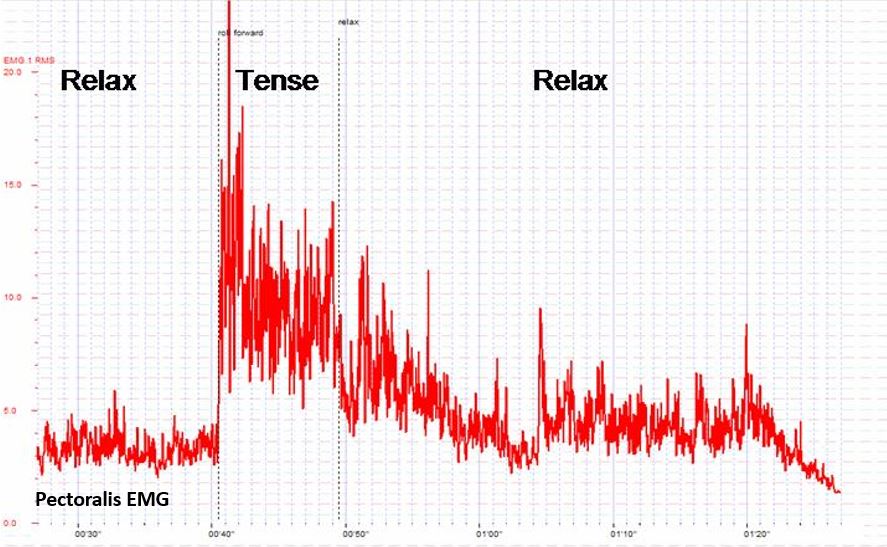

1. Assessment of Muscle Reactivity. After the electrode was attached on her pectoralis muscle and with her arm resting on her lap, she was asked to roll her left shoulder slightly more forward, hold the tension for the count of 10 and then let go and relax. Even with feedback, the muscle activity stayed high and did not relax and return to a lower level of activity as shown in Figure 2. This lack of return to baseline is often a diagnostic indicator of muscle irritability or injury (Sella, 1998; Sella, 2006). If the muscle does not relax immediately after contraction, movement or exercise should not be prescribed, since it may aggravate the injury. Instead, the person first needs to learn how to relax and then learn how to relax between activation and tensing of the muscle. The general observation of T. was that at the initiation of any movement (active or passive) muscle tension increased and did not return to baseline for more than two minutes.

Figure 2. Simulation of the effect on the pectoralis sEMG (this is a recording from another subject who showed a similar response pattern that was visually observed from T. with the Myotrac). After the muscle is contracted it takes a long time to return to baseline level

2. Exploration. Self-exploration with feedback was encouraged. T. was instructed to let go of muscle tension in her left shoulder girdle. In addition the therapist tried to induce her letting go by gently and passively rocking her left arm. The increased SEMG activity and the protective bracing in her shoulder showed that she couldn’t reduce the muscle tension. Each time her arm was moved, however slightly, she helped with the movement and kept control. In addition, T. was asked to reduce the muscle tension using the biofeedback signal; again she was not able to reduce her muscle tension with feedback.

3. Passive Stretch and Movements. The next step was to passively stretch the pectoralis muscle by holding the shoulder between both hands and very gently externally rotate the shoulder — a process derived from the Alexander technique (Barlow, 1991). Each time the instructor attempted to rotate her shoulder, the SEMG increased and T. reported an increased fear of pain. T.’s SEMG response most likely consisted of the following components:

- Movement induced pain

- Increased splinting and guarding

- Increased arousal/vigilance to perform well

These three assessment and self-regulation procedures were unsuccessful in reducing muscle tension or increasing shoulder movement. This suggested that another therapeutic intervention would need to be developed to allow the left pectoralis area to relax. The SEMG could be used as an indicator whether the intervention was successful as indicated by a reduction in SEMG activity. Finally, the inability to relax after tightening (bracing and splinting) probably aggravated her discomfort.

Multiple levels of injury: The obvious injury and discomfort was due to her left chest wall being hit by the ski pole. She then guarded the area by bracing the muscles to protect it which limited movement. The guarding tightened the muscles and limited blood circulation and lymphatic flow which increased local ischemia, irritation and pain. This led to a self-perpetuating cycle: Pain triggers guarding and guarding increases pain and impedes self-healing.

As the SEMG and passive stretching assessment were performed, the therapist concurrently discussed the pain process. Namely, from this perspective, there were at least two types of pains:

- Pain caused by the physiological injury

- Pain as the result of guarding

The pain from the guarding is similar to having exercised for a long time after not having exercised. The next day you feel sore. However, if you feel sore, you know that it was due to the exercise therefore it is defined as a good pain. In T.’s case, the pain indicated that something was wrong and did not heal and therefore she would need to protect it. We discussed this process as a way to use cognitive reframing to change her attitude toward guarding and pain.

Rationale: The intention was to interrupt her negative image of pain that acted as a post hypnotic suggestion. The objective was to change her image and thoughts from “pain indicates the muscle is damaged” to “pain indicates the muscle has worked too hard and long and needs time to regenerate.”

Treatment interventions

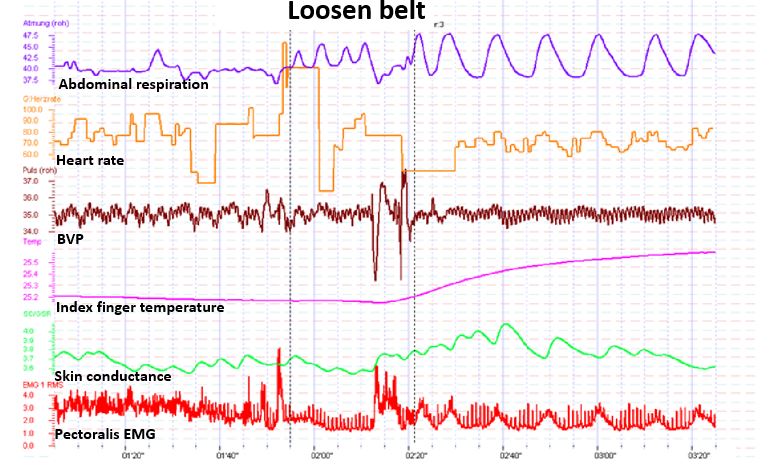

The initial intervention focused upon shifting shallow thoracic breathing to diaphragmatic breathing. Generally, when people breathe rapidly and predominantly in their chest, they usually tighten their neck and shoulder muscles during inhalation. One of the reasons T. breathed in her chest was that her clothing–very tight jeans–constricted her waist (MacHose & Peper, 1991; Peper et al., 2015). This breathing pattern probably contributed to sub-clinical hyperventilation and was part of a fear or flexor response pattern. When she loosened the upper buttons of her jeans and allowed her stomach to expand her pectoralis muscle relaxed as she breathed as shown in Figure 3. As she began to breathe in this pattern, each time she exhaled her pectoralis muscle tension decreased.

Figure 3. Illustration of the effect of loosening tight waist constriction (eliminating designer’s jean syndrome) on blood flow and pectoralis sEMG. Abdominal breathing became possible and finger temerature increased (this recording is from another subject whose physiological responses were similar to that was observed with the Myotrac from T.)

Following the demonstration that breathing significantly lowered her chest muscle tension, the discussion focussed on the importance of effortless diaphragmatic breathing for health and reduction of vigilance. Being awkward and uncomfortable at loosening her pants, she struggled with allowing her abdomen to expand and her pants to be looser because she thought that she looked much more attractive in tight clothing. Yet, she agreed that her boy friend would love her regardless whether she wore loose or tight clothing. To encourage an acceptance for wearing looser clothing and thereby permit diaphragmatic breathing during the day, an informal discussion focused on “designer jeans syndrome” (chest breathing induced by tight clothing) with humorous examples such as discussing the name of the room that is located on top of the stairs in the Victorian houses in San Francisco. It is called the fainting room–in the 19th century women who wore corsets and had to climb the stairs would have to breathe rapidly and then would faint when they reached the top of the stairs (Peper, 1990).

Rationale: Rapid shallow chest breathing can induce a catabolic state that inhibits healing while diaphragmatic breathing may induce an anabolic state that promotes regeneration. Moreover, effortless diaphragmatic breathing would increase respiratory sinus arhythmia (RSA)–heart rate variability linked to breathing– and thereby facilitate sympathetic-parasympathetic balance that would promote self-healing.

The discussion included the use of the YES set which meant asking a person questions in such a way that she/he answers the question with YES. When a person answers YES at least three times in a row rapport is often facilitated (Erikson, 1983, pp. 237-238). Questions were framed in such a way that the client would answer with YES. For example, if the therapist thought the person did not do their homework, a yes question could be framed as, “It must have been difficult to find time to do the homework this week?” In T.’s case, the therapist said, “I see, you would rather wear tight clothing than allow your shoulder to heal.” She answered, “Yes.” This was the expected answer, however, the question was framed in an intuitive guess on the therapist’s part. Nevertheless, the strategy would have been successful either way because if she had answered “No,” it would have broken the “Yes: set, but she would then be committed to change her clothing.

Throughout this discussion, the therapist placed his left hand on her abdomen over her belly button and overtly and covertly guided her breathing movement. As she exhaled, he pressed gently on her abdomen; as she inhaled he drew his hand away–as if her abdomen was like a balloon that inflated during inhalation and deflated during exhalation. To enhance learning diaphragmatic breathing and slower exhalation, the therapist covertly breathed at the same rhythm and gently exhaled as she exhaled while allowing the breathing movement to be mainly in his abdomen. In this process, learning occurred without demand for performance and she could imitate the breathing process that was covertly modelled by the therapist.

The Change

The central observation was that each time she tried to relax or do something, she would slight brace which increased her pectoralis SEMG activity. The chronic tension from guarding probably induced localized ischemia, inhibited lymphatic flow and drainage, and reduced blood circulation which would increase tissue irritation. Whenever the therapist began to move her arm, she would anticipate and try to help with the movement. Overall she was vigilant (also indicated by her very cold hands) and wanted to perform very well (a possible need for approval). Her muscle bracing and helping with movement was reframed as a combined activity that consisted of guarding to prevent further injury and as a compliment that she would like to perform well.

Labelling her activity as a “compliment” was part of a continuing YES set approach. The therapist was deliberately framing whatever happened as adaptive behaviour, with positive intent. Further, if one tries and does something with too much effort while being vigilant, the arousal would probably induce hand cooling. If the activity can be performed with passive attention, then increased blood flow and warmth may occur. The therapeutic challenge was how to reduce vigilance, perfectionism and guarding so that the muscles that were guarding the traumatized area would relax.

Therapeutic concept: If a direct approach does not work, an indirect approach needs to be employed. Through an indirect approach, the person experiences a change without trying to focus on doing or achieving it. Underlying this approach is the guideline: If something does not work, try it once more and then if it does not work, do something completely different. This is analogous to sexual arousal: If you demand from a male to have an erection: The more performance you demand the less likely will there be success. On the other hand, if you remove the demand for performance and allow the person to become interested and thereby feel an erotic experience an erection may occur without effort.

The shift to an indirect intervention was done through active somatic visualization. T. was encouraged to visualize and remember a positive image or memory from her past. She chose a memory of a time when she was in Paris with her grandmother. While T. visualized being with her grandmother, the therapist asked another older women participant to help and hold T’s right hand in a grandmother-like way as if she was her grandmother. The “grandmother” then moved T.’s hand in a playful way as if dancing with T.’s right arm. Through this kinesthetic experience, T. became more and more absorbed in her memory experience. At the same time, T´s left hand was being held and gently rocked by the therapist. During this gentle rocking, the SEMG activity decreased completely in her left pectoralis area. The therapist used the SEMG feedback to guide him in the gentle rocking motion of T.’s left arm and very slowly increased the range of her arm and shoulder motion. Gentle movement was done only as long as the SEMG activity did not increase. It allowed the muscle to stay relaxed and facilitated the experience of trust. The following is T. report two days later of what happened.

“Initially it was very difficult for me to let go of control because I found this idea somewhat strange and I was puzzled. I expected the therapist to intervene and I felt frightened. The therapist’s soft and gentle touch and his very soft voice in this kind of meditation helped me to let go of control and I was surprised about my own courage to give myself into the process without knowing what would happen next.”

Rationale: Every corresponding thought and emotion has an associated body response and every body response has an associated mental/emotional response (Green & Green, 1977; Green, 1999). Therefore, an image and experience of a happy and safe past memory will allow the body to evoke the same state and vigilance can be abated. The intensity of the experience is increased when multi-sensory cues are included such as actual handholding. The more senses are involved, the more the experience can become real. In addition, the tactile sensation of feeling the grandmother’s hand diverted her attention away from her shoulder into her hand and thereby reduced her active efforts of trying to relax the shoulder and pectoralis area. Doing something she did not expect to happen also helped her loose control – an implicit confusion approach.

SEMG feedback was used as the guide for controlling the movement. The therapist gently increased the range of the movements in abduction and external rotation directions while continuously rocking her arm until her injured arm was able to move unrestricted in full range of motion. The arm and shoulder relaxation and continuous subtle movement without evoking any SEMG activation facilitated blood flow and lymphatic drainage which probably reduced congestion. After a few minutes, the therapist gently dropped her arm on her lap. After her arm was resting on her lap, she reported that it felt very heavy and relaxed and that she didn’t feel any pain. However, she initially didn’t really realize that her mobility had increased dramatically.

Rationale: When previous movements that had been associated with pain are linked to an experience of pleasure, the movement is often easier. The conditioned muscle bracing patterns associated with anticipation of pain and/or concern for improvement/results are reduced.

Process to deepen and generalize the relaxation and breathing. She was asked to imagine breathing the air down and through her arms and legs–a strategy that she could then do at home with her boyfriend. We wanted to involve another person because it is often difficult to do homework practices without striving and concern for results and focussing on the area of discomfort. Her response to asking if her boyfriend would help was an automatic “naturally” (the continuation of the YES set). With her agreement, we role played how her boyfriend was to encourage diaphragmatic breathing. He was to gently stroke down her legs as she exhaled. She could then just focus on the sensations and allow the air to flow down her legs. Then, while she continued to breathe effortlessly, he would gently rock and move her arm.

To be sure that she knew how to give the instructions, the therapist role played her boyfriend and then asked her to rock his arm so that she would know how to teach her boy friend how to move her arm. The therapist sat on her left side, and, as she now held his right arm and gently rocked it with her left arm, the therapist gently moved backwards. This meant that she externally rotated her left arm and shoulder more and more. He moved in such a way that in the process of rocking his arm, she moved her “previously injured shoulder” in all directions (up, down, forward and backwards) and was unaware that she could move her arm and shoulder as she did not experience any discomfort. Afterwards, we shared our observations and she was asked to move her arm and shoulder. She moved it without any restrictions or discomfort.

Rationale: By focusing outside herself and not being concerned about herself, she did not think of herself or of trying to move her arm and shoulder. Hence, she did not evoke the anticipatory guarding and thus significantly increased her flexibility.

Process of acceptance. Often after an injury, we are frustrated with our bodies. This frustration may interfere with healing. Therefore, the session concluded by asking her to be appreciative of her shoulder and arm. She was asked to think of all the positive things her shoulder, chest and arm have done for her in the past instead of the many limitations and pains caused by the injury. Instead of being angry at her shoulder that it had not healed or restricted her movement, we suggested that she should appreciate her shoulder and pectoralis area for all it had done without her awareness such as: How the shoulder moved her arm during love-making, how without complaining her shoulder moved during walking, writing, skiing, eating, etc., and how many times in the past she had abused her shoulder without giving it proper respect and appreciation. This process reframes the way one symbolically relates to the injured area. Every thought of discomfort or negative judgement becomes the trigger and is transformed into breathing lower and slower and evokes an appreciation of the positive nice things her shoulder has done for her in the past.

Rationale: When injured we often evoke negative mental and emotional images which become post- hypnotic suggestions. Those negative thoughts, images and emotions interfere with healing while positive thoughts, images and emotions tend to promote healing. A possible energetic process that occurs when injured is that we withdraw awareness/ consciousness from the injured area which reduces blood and lymph circulation. Caring and positive feelings about an area tends to increase blood flow and warmth (a heart-warming experience) and promotes healing.

RESULTS

She left the initial session without any pain and with total range of motion. At the two week follow-up she reported continued pain relief and complete range of motion. T.s reflection of the experience was:

“I really was not aware that I could move my arm freely like before the accident, I was just feeling a kind of trance and was happy to not feel any pain and to feel much more upright than before. Then I watched the faces of the two other therapists who sat there with big eyes and a grin on their face and then become aware of my own arms position which was rotated backwards and up, a movement that was impossible to do before. I remember this evening that I left with this feeling of trance and that I often tried to go back to my collapsed posture but this was not possible anymore and I felt very tall and straight. Now two weeks later I still feel like that and know that I had an amazing experience which I will store in my brain!

My father who is an orthopedic surgeon tested me and found out, that I had hurt my rib. He said that I have a contusion and it will go away in a few weeks. Before this experience, I would say that he was not open to Biofeedback. However he was so captivated by my experiences that he spontaneously promised me to pay for my own biofeedback equipment and to support me with my educational program and even offered me a job in his practice to do this work!”

Psychophysiological Follow-up: 3 Weeks Later

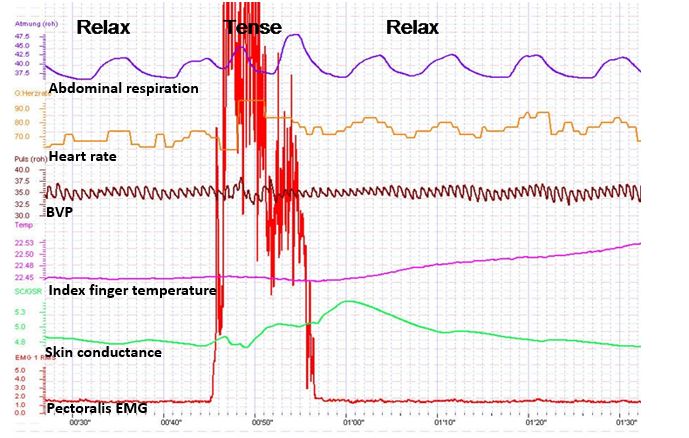

The physiological assessment included monitoring thoracic and abdominal breathing patterns, blood volume pulse, heart rate and SEMG from her left pectoralis muscle while she was asked to roll her left shoulder forward (adducted and internally rotated) for the count of 10 and then relax. The physiological recording showed that she breathed more diaphragmatically and that her pectoralis muscle relaxed and returned directly to baseline after rotation as shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4. Physiological profile during the rolling left shoulder forward (tense) and relaxing at thethree week follow-up. Note that the pectoralis sEMG activity returned rapidly to baseline after contracting and her breathing pattern is abdomninal and slower.

Summary

This case example demonstrates the usefulness of a simple one-channel SEMG biofeedback device to guide the interventions during assessment and treatment. It suggests that the therapist and client can use the SEMG activity as an indicator of guarding–a visual representation of the subjective experience of fear, pain and range of mobility–that can be evoked during assessment and therapeutic interventions. The anticipation of increased pain commonly occurs during diagnosis and treatment and often becomes an obstacle for healing because increased pain may increase anticipation of pain and trigger even more bracing. To avoid triggering this vicious circle of guarding/fear, the feedback signal allows the therapist and the client to explore strategies that reduce muscle activity by indirect interventions.

By using an indirect approach that the client may not expect, the interventions shift the focus of attention and striving and may allow increased freedom and relaxation. The biofeedback signal may guide the therapeutic process to reduce the patterns of fear, panic, and bracing that are commonly associated with injury and illnesses. Once this excessive sympathetic activity is reduced, the actual pathophysiology may become obvious (in most cases is much less then before) and the healing process may be accelerated. This case description may offer an approach in diagnosis and treatment for many therapists and open a door for a gentle, painless and yet successful way of treatment and encourage therapists to be creative and use both experience/technique and intuition.

For additional intervention approaches see the following two blogs.

References

Barlow, W. (1991). The Alexander technique: How to use your body without stress. Rochester, VT: Healing Arts Press https://www.amazon.com/Alexander-Technique-Your-without-Stress/dp/0892813857#:~:text=Barlow%2C%20the%20foremost%20exponent%20and,and%20movement%20in%20everyday%20activities.

Erikson, M. H. (1983). Healing in hypnosis, volume 1 (Edited by E. L. Rossi, M. O. Ryan, M. & F. A. Sharp). New York: Irvington Publishers, Inc.. https://www.amazon.com/Hypnosis-Seminars-Workshops-Lectures-Erickson/dp/0829007393/ref=sr_1_1?keywords=9780829007398&linkCode=qs&qid=1692038804&s=books&sr=1-1

Green, E. (1999). Psychophysical Principal. Accessed August 14, 2023 https://www.elmergreenfoundation.org/psychophysiological-principal/

Green, E., & Green, A. (1977). Beyond biofeedback. New York:

Delacorte Press/Seymour. https://elmergreenfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Beyond-Biofeedback-Green-Green-Searchable.pdf

MacHose, M., & Peper, E. (1991). The effect of clothing on inhalation volume. Biofeedback and Self-Regulation. 16(3), 261-265. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01000020

Peper, E. (1990). Breathing for health. Montreal: Thought Technology Ltd.

Peper, E. & Gibney, K.H. (2006). Muscle biofeedback at the computer-A manual to prevent repetitive strain injury (RSI) by taking the guesswwork out of assessment, monitoring and training. Biofeedback Foundation of Europe. https://thoughttechnology.com/muscle-biofeedback-at-the-computer-book-t2245/

Peper, E., Gilbert, C.D., Harvey, R. & Lin, I-M. (2015). Did you ask about abdominal surgery or injury? A learned disuse risk factor for breathing dysfunction. Biofeedback. 34(4), 173-179. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-43.4.06

Sella, G. E. (2006). SEMG: Objective methodology in muscular dysfunction investigation and rehabilitation. Weiner’s pain management: A practical guide for clinicians, CRC Press, 645-662. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.1201/b14253-45/semg-objective-methodology-muscular-dysfunction-investigation-rehabilitation-gabriel-sella

Sella, G. E. (1998). Towards an Integrated Approach of sEMG Utilization: Quantative Protocols of Assessment and Biofeedback. Electromyography: Applications in Physical Medicine. Thought Technology, 13. https://www.bfe.org/protocol/pro13eng.htm

[1] We thank Theresa Stockinger for her significant contribution and Candy Frobish for her helpful comments.