Quick Rescue Techniques When Stressed

Posted: February 4, 2024 Filed under: attention, behavior, biofeedback, Breathing/respiration, CBT, cognitive behavior therapy, education, emotions, Evolutionary perspective, Exercise/movement, health, mindfulness, Neck and shoulder discomfort, posture, relaxation, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: alarm reaction, anxiety, box breathing, Breathing, conditioning, defense reaction, health, huming, Parasympathetic response, rumination, safety, sniff inhale, somatic practices, stress, sympathetic arousal, tactical breathing, Toning, yoga 2 CommentsErik Peper, PhD, Yuval Oded, PhD, and Richard Harvey, PhD

Adapted from Peper, E., Oded, Y, & Harvey, R. (2024). Quick somatic rescue techniques when stressed. Biofeedback, 52(1), 18–26. https://doi.org/10.5298/982312

“If a problem is fixable, if a situation is such that you can do something about it, then there is no need to worry. If it’s not fixable, then there is no help in worrying. There is no benefit in worrying whatsoever.” ― Dalai Lama XIV

To implement the Dalai Lama’s quote is challenging. When caught up in an argument, being angry, extremely frustrated, or totally stressed, it is easy to ruminate, worry. It is much more challenging to remember to stay calm. When remembering the message of the Dalai Lama’s quote, it may be possible to shift perspective about the situation although a mindful attitude may not stop ruminating thoughts. The body typically continues to reacti to the torrents of thoughts that may occur when rehashing rage over injustices, fear over physical or psychological threats, or profound grief and sadness over the loss of a family member. Some people become even more agitated and less rational as illustrated in the following examples.

I had an argument with my ex and I am still pissed off. Each time I think of him or anticipate seeing them, my whole body tightened. I cannot stomach seeing him and I already see the anger in his face and voice. My thoughts kept rehashing the conflict and I am getting more and more upset.

A car cut right in front of me to squeeze into my lane. I had to slam on my brakes. What an idiot! My heart rate was racing and I wanted to punch the driver.

When threatened, we respond quickly in our thoughts and body with a defense reaction that may negatively affect those around us as well as ourselves. What can we do to interrupt negative stress reactions?

Background

Many approaches exist that allow us to become calmer and less reactive. General categories include techniques of cognitive reappraisal (seeing the situation from the other person’s point of view and labeling your own feelings and emotions) and stress management techniques. Practices that are beneficial include mindfulness meditation, benign humor (versus gallows humor), listening to music, taking a time out while implementing a variety of self-soothing practices, or incorporating slow breathing (e.g., heart rate variability and/or box breathing) throughout the day.

No technique fits all as we respond differently to our stressful life circumstances. For example, some people during stress react with a “tend and befriend stress response” (Cohen & Lansing, 2021; Taylor et al., 2000). This response appears to be mostly mediated by the hormone oxytocin acting in ways that sooth or calm the nervous system as an analgesic. These neurophysiological mechanisms of the soothing with the calming analgesic effects of oxytocin have been characterized in detail by Xin, et al. (2017).

The most common response is a fight/flight/freeze stress response that is mediated by excitatory hormones such as adrenalin and inhibitory neurotransmitters such as gamma amino butyric acid (GABA). There is a long history of fight/flight/freeze stress response research, which is beyond the scope of this blog with major theories and terms such as interior milleau (Bernard, 1872); homeostasis and fight/flight (Cannon, 1929); general adaptation syndrome (Selye, 1951); polyvagal theory (Porges, 1995); and, allostatic load (McEwen, 1998). A simplified way to start a discussion about stress reactions begins with the fight/flight stress response. When stressed our defense reactions are triggered. Our sympathetic nervous system becomes activated our mind and body stereotypically responds as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. An intense confrontation tends to evoke a stress response (reproduced from Peper et al., 2020).

The flight/fight response triggers a cascade of stress hormones or neurotransmitters (e.g., hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal cascade) and produces body changes such as the heart pounding, quicker breathing, an increase in muscle tension and sweating. Our body mobilizes itself to protect itself from danger. Our focus is on immediate survival and not what will occur in the future (Porges, 2021; Sapolsky, 2004). It is as if we are facing an angry lion—a life-threatening situation—and we feel threatened and unsafe.

Rather than sitting still, a quick effective strategy is to interrupt this fight/flight response process by completing the alarm reaction such as by moving our muscles (e.g., simulating a fight or flight behavior) before continuing with slower breathing or other self-soothing strategies. Many people have experienced their body tension is reduced and they feel calmer when they do vigorous exercise after being upset, frustrated or angry. Similarly, athletes often have reported that they experience reduced frequency and/or intensity of negative thoughts after an exhausting workout (Thayer, 2003; Liao et al., 2015; Basso & Suzuki, 2017).

Becoming aware of the escalating cascades of physical, behavioral and psychological responses to a stressor is the first step in interrupting the escalating process. After becoming aware, reduce the body’s arousal and change the though patterns using any of the techniques described in this blog. The self-regulation skills presented in this blog are ideally over-learned and automated so that these skills can be rapidly implemented to shift from being stressed to being calm. Examples of skills that can shift from sympathetic neervous system overarousal to parasympathetic nervous system calm include techniques of autogenic traing (Schulz & Luthe, 1959), the quieting reflex developed by Charles Stroebel in 1985 or more recently rescue breathing developed by Richard Gevirtz (Stroebel, 1985; Gevirtz, 2014; Peper, Gibney & Holt, 2002; Peper & Gibney, 2003).

Concepts underlying the rescue techniques

- Psychophysiological principle: “Every change in the physiological state is accompanied by an appropriate change in the mental-emotional state, conscious or unconscious, and conversely, every change in the mental-emotional state, conscious or unconscious, is accompanied by an appropriate change in the physiological state” (Green et al. 1970, p. 3).

- Posture evokes memories and feelings associated with the position. When the body posture is erect and tall while looking slightly up. It is easier to evoke empowering, positive thoughts and feelings. When looking down it is easier to evoke hopeless, helpless and powerless thoughts and feelings (Peper et al., 2017).

- Healing occurs more easily when relaxed and feeling safe. Feeling safe and nurtured enhances the parasympathetic state and reduces the sympathetic state. Use memory recall to evoke those experiences when you felt safe (Peper, 2021).

- Interrupting thoughts is easier with somatic movement than by redirecting attention and thinking of something else without somatic movement.

- Focus on what you want to do not want to do. Attempting to stop thinking or ruminating about something tends to keeps it present (e.g., do not think of pink elephants. What color is the elephant? When you answer, “not pink,” you are still thinking pink). A general concept is to direct your attention (or have others guide you) to something else (Hilt & Pollak, 2012; Oded, 2018; Seo, 2023).

- Skill mastery takes practice and role rehearsal (Lally et al., 2010; Peper & Wilson, 2021).

- Use classical conditioning concepts to facilitate shifting states. Practice the skills and associate them with an aroma, memory, sounds or touch cues. Then when you the situation occurs, use these classical conditioned cues to facilitate the regeneration response (Peper & Wilson, 2021).

Rescue techniques

Coping When Highly Stressed and Agitated

- Complete the alarm/defense reaction with physical activity (Be careful when you do these physical exercises if you have back, hip, knee, or ankle problems).

- Acknowledge you have reacted and have chosen to interrupt your automatic response.

- Check whether the situation is actually a threat. If yes, then do anything to get out of immediate danger (yell, scream, fight, run away, or dial 911).

- If there is no actual physical threat, then leave the situation and perform vigorous physical activity to complete your alarm reaction, such as going for a run or walking quickly up and down stairs. As you do the exercise, push yourself so that the muscles in your thighs are aching, which focusses your attention on the sensations in your thighs. In our experience, an intensive run for 20 minutes quiets the brain while it often takes 40 minutes when walking somewhat quickly.

- After recovering from the exhaustive exercise, explore new options to resolve the conflict.

- Complete the alarm/defense reaction and evoke calmness with the S.O.S™ technique (Oded, 2023)

- Acknowledge you have reacted and have chosen to interrupt your automatic response.

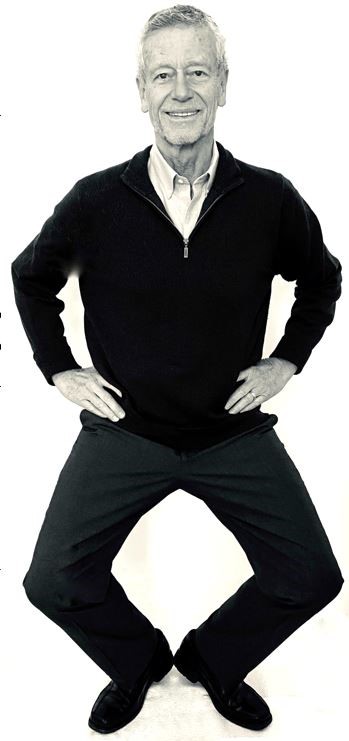

- Squat against a wall (similar to the wall-sit many skiers practice). While tensing your arms and fists as shown in Figure 2, gaze upward because it is more difficult to engage in negative thinking while looking upwards. If you continue to ruminate, then scan the room for object of a certain color or feature to shift visual attention and be totally present on the visual object.

- Do this set of movements for 7 to 10 seconds or until you start shaking. Than stand up and relax hands and legs. While standing, bounce up and down loosely for 10 to 15 seconds as you become aware of the vibratory sensations in your arms and shoulders, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2.Defense position wall-sit to tighten muscles in the protective defense posture (Oded, 2023). Figure 3. Bouncing up and down to loosen muscles ((Oded, 2023).

- Acknowledge you have reacted and have chosen to interrupt your automatic response. Swing your arms back and forth for 20 seconds. Allow the arms to swing freely as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Swinging the arms to loosen the body and spine (Oded, 2023).

- Rest and ground. Lie on the floor and put your calves and feet on a chair seat so that the psoas muscle can relax, as illustrated in Figure 5. Allow yourself to be totally supported by the floor and chair. Be sure there is a small pillow under your head and put your hand on your abdomen so that you can focus on abdominal breathing.

Figure 5. Lying down to allow the psoas muscle to relax and feel grounded (Oded, 2023).

- While lying down, imagine a safe place or memory and make it as real as possible. It is often helpful to listen to a guided imagery or music. The experience can be enhanced if cues are present that are associated with the safe place, such as pictures, sounds, or smells. Continue to breathe effortlessly at about six breaths per minute. If your attention wanders, bring it back to the memory or to the breathing. Allow yourself to rest for 10 minutes.

In most cases, thoughts stop and the body’s parasympathetic activity becomes dominant as the person feels safe and calm. Usually, the hands warm and the blood volume pulse amplitude increases as an indicator of feeling safe, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Blood volume pulse increases as the person is relaxing, feels safe and calm.

Coping When You Can’t Get Away (adapted from Peper, Harvey & Faass, 2020)

In many cases, it is difficult or embarrassing to remove yourself from the situation when you are stressed out such as at work, in a business meeting or social gathering.

- Become aware that you have reacted.

- Excuse yourself for a moment and go to a private space, such as a restroom. Going to the bathroom is one of the only acceptable social behaviors to leave a meeting for a short time.

- In the bathroom stall, do the 5-minute Nyingma exercise, which was taught by Tarthang Tulku Rinpoche in the tradition of Tibetan Buddhism, as a strategy for thought stopping (see Figure 7). Stand on your toes with your heels touching each other. Lift your heels off the floor while bending your knees. Place your hands at your sides and look upward. Breathe slowly and deeply (e.g., belly breathing at six breaths a minute) and imagine the air circulating through your legs and arms. Do this slow breathing and visualization next to a wall so you can steady yourself if necessary to keep balance. Stay in this position for 5 minutes or longer. Do not straighten your legs—keep squatting despite the discomfort. In a very short time, your attention is captured by the burning sensation in your thighs. Continue. After 5 minutes, stop and shake your arms and legs.

Figure 7. Stressor squat Nyingma exercise (reproduced from Peper et al., 2020).

- Follow this practice with slow abdominal breathing to enhance the parasympathetic response. Be sure that the abdomen expands as the inhalation occurs. Breathe in and out through the nose at about six breaths per minute.

- Once you feel centered and peaceful, return to the room.

- After this exercise, your racing thoughts most likely will have stopped and you will be able to continue your day with greater calm.

What to do When Ruminating, Agitated, Anxious or Depressed

(adapted from Peper, Harvey, & Hamiel, 2019).

- Shift your position by sitting or standing erect in a power position with the back of the head reaching upward to the ceiling while slightly gazing upward. Then sniff quickly through nose, hold and again sniff quickly then very slowly exhale. Be sure as you exhale your abdomen constricts. Then sniff again as your abdomen gets bigger, hold, and sniff one more time letting the abdomen get even bigger. Then, very slow, exhale through the nose to the internal count of six (adapted from Balban et al., 2023). When you sniff or gasp, your racing thoughts will stop (Peper et al., 2016).

- Continue with box breathing (sometimes described as tactical breathing or battle breathing) by exhaling slowly through your nose for 4 seconds, holding your breath for 4 seconds, inhaling slowly for 4 seconds through your nose, holding your breath for 4 seconds and then repeating this cycle of breathing for a few minutes (Röttger et al., 2021; Balban et al., 2023). Focusing your attention on performing the box breathing makes it almost impossible to think of anything else. After a few minutes, follow this with slow effortless diaphragmatic breathing at about six breaths per minute. While exhaling slowly through your nose, look up and when you inhale imagine the air coming from above you. Then as you exhale, imagine and feel the air flowing down and through your arms and legs and out the hands and feet.

- While gazing upward, elicit a positive memory or a time when you felt safe, powerful, strong and/or grounded. Make the positive memory as real as possible.

- Implement cognitive strategies such as reframing the issue, sending goodwill to the person, seeing the problem from the other person’s point of view, and ask is this problem worth dying over (Peper, Harvey, & Hamiel, 2019).

What to Do When Thoughts Keep Interrupting

Practice humming or toning. When you are humming or toning, your focus is on making the sound and the thoughts tend to stop. Generally, breathing will slow down to about six breaths per minute (Peper, Pollack et al., 2019). Explore the following:

- Box breathing (Röttger et al., 2021; Balban et al., 2023)

- Humming also known as bee breath (Bhramari Pranayama) (Abishek et al., 2019; Yoga, 2023) – Allow the tongue to rest against the upper palate, sit tall and erect so that the back of the head is reaching upward to the ceiling, and inhale through your nose as the abdomen expands. Then begin humming while the air flows out through your nose, feel the vibration in the nose, face and throat. Let humming last for about 7 seconds and then allow the air to blow in through the nose and then hum again. Continue for about 5 minutes.

- Toning – Inhale through your nose and then vocalize a single sound such as Om. As you vocalize the lower sound, feel the vibration in your throat, chest and even going down to the abdomen. Let each toning exhalation last for about 6 to 7 seconds and then inhale through your nose. Continue for about 5 minutes (Peper, al., 2019).

Many people report that after practice these skills, they become aware that they are reacting and are able to reduce their automatic reaction. As a result, they experience a significant decrease in their stress levels, fewer symptoms such as neck and holder tension and high blood pressure, and they feel an increase in tranquility and the ability to communicate effectively.

Practicing these skills does not resolve the conflicts; they allow you to stop reacting automatically. This process allows you a time out and may give you the ability to be calmer, which allows you to think more clearly. When calmer, problem solving is usually more successful. As phrased in a popular meme, “You cannot see your reflection in boiling water. Similarly, you cannot see the truth in a state of anger. When the waters calm, clarity comes” (author unknown).

Boiling water (photo modified from: https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=388991500314839&set=a.377199901493999)

Below are additional resources that describe the practices. Please share these resources with friends, family and co-workers.

Stressor squat instructions

Toning instructions

Diaphragmatic breathing instructions

Reduce stress with posture and breathing

Conditioning

References

Abishek, K., Bakshi, S. S., & Bhavanani, A. B. (2019). The efficacy of yogic breathing exercise bhramari pranayama in relieving symptoms of chronic rhinosinusitis. International Journal of Yoga, 12(2), 120–123. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijoy.IJOY_32_18

Balban, M. Y., Neri, E., Kogon, M. M., Weed, L., Nouriani, B., Jo, B., Holl, G., Zeitzer, J. M., Spiegel, D., Huberman, A. D. (2023). Brief structured respiration practices enhance mood and reduce physiological arousal. Cell Reports Medicine, 4(1), 10089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100895

Basso, J. C. & Suzuki, W. A. (2017). The effects of acute exercise on mood, cognition, neurophysiology, and neurochemical pathways: A review. Brain Plast, 2(2), 127–152. https://doi.org/10.3233/BPL-160040

Bernard, C. (1872). De la physiologie générale. Paris: Hachette livre. https://www.amazon.ca/PHYSIOLOGIE-GENERALE-BERNARD-C/dp/2012178596

Cannon, W. B. (1929). Organization for Physiological Homeostasis. Physiological Reviews, 9, 399–431. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.1929.9.3.399

Cohen, L. & Lansing, A. H. (2021). The tend and befriend theory of stress: Understanding the biological, evolutionary, and psychosocial aspects of the female stress response. In: Hazlett-Stevens, H. (eds), Biopsychosocial Factors of Stress, and Mindfulness for Stress Reduction. pp. 67–81, Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81245-4_3

Gevirtz, R. (2014). HRV Training and its Importance – Richard Gevirtz, Ph.D., Pioneer in HRV Research & Training. Thought Technology. Accessed December 29, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9nwFUKuJSE0

Green, E. E., Green, A. M., & Walters, E. D. (1970). Voluntary control of internal states: Psychological and physiological. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 2, 1–26. https://atpweb.org/jtparchive/trps-02-70-01-001.pdf

Hilt, L. M., & Pollak, S. D. (2012). Getting out of rumination: comparison of three brief interventions in a sample of youth. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40(7), 1157–1165.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-012-9638-3

Lally, P., VanJaarsveld, C. H., Potts, H. W., & Wardle, J. (2010). How habits are formed: Modelling habit formation the real world. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 998–1009. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.674

Liao, Y., Shonkoff, E. T., & Dunton, G. F. (2015). The acute relationships between affect, physical feeling states, and physical activity in daily life: A review of current evidence. Frontiers in Psychology. 6, 1975. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01975

McEwen, B. S. (1998). Stress, adaptation, and disease: Allostasis and allostatic load. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 840(1), 33–44.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09546.x

Oded, Y. (2018). Integrating mindfulness and biofeedback in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Biofeedback, 46(2), 37-47. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-46.02.03

Oded, Y. (2023). Personal communication. S.O.S 1™ technique is part of the Sense Of Safety™ method. www.senseofsafety.co

Peper, E. (2021). Relive memory to create healing imagery. Somatics, XVIII(4), 32–35.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/369114535_Relive_memory_to_create_healing_imagery

Peper, E., Gibney, K.H. & Holt. C. (2002). Make Health Happen: Training Yourself to Create Wellness. Dubuque, IA: Kendall-Hunt. https://he.kendallhunt.com/product/make-health-happen-training-yourself-create-wellness

Peper, E., & Gibney, K.H. (2003). A teaching strategy for successful hand warming. Somatics. XIV(1), 26–30. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/376954376_A_teaching_strategy_for_successful_hand_warming

Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Faass, N. (2020). TechStress: How Technology is Hijacking Our Lives, Strategies for Coping, and Pragmatic Ergonomics. North Atlantic Books. https://www.amazon.com/Beyond-Ergonomics-Prevent-Fatigue-Burnout/dp/158394768X

Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Hamiel, D. (2019). Transforming thoughts with postural awareness to increase therapeutic and teaching efficacy. NeuroRegulation, 6(3),153–160. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.6.3.153

Peper, E., Lee, S., Harvey, R., & Lin, I-M. (2016). Breathing and math performance: Implication for performance and neurotherapy. NeuroRegulation, 3(4), 142–149. http://dx.doi.org/10.15540/nr.3.4.142

Peper, E., Lin, I-M, Harvey, R., & Perez, J. (2017). How posture affects memory recall and mood. Biofeedback, 45(2), 36–41. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-45.2.01

Peper, E., Pollack, W., Harvey, R., Yoshino, A., Daubenmier, J. & Anziani, M. (2019). Which quiets the mind more quickly and increases HRV: Toning or mindfulness? NeuroRegulation, 6(3), 128–133. https://www.neuroregulation.org/article/view/19345/13263

Peper, E. & Wilson, V. (2021). Optimize the learning state: Techniques and habits. Biofeedback, 9(2), 46–49. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-49-2-04

Porges, S. W. (1995). Orienting in a defensive world: Mammalian modifications of our evolutionary heritage. A polyvagal theory. Psychophysiology, 32(4), 301–318. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.1995.tb01213.x

Porges, S.W. (2021) Cardiac vagal tone: a neurophysiological mechanism that evolved in mammals to dampen threat reactions and promote sociality. World Psychiatry, 20(2),296-298. Porges SW. Cardiac vagal tone: a neurophysiological mechanism that evolved in mammals to dampen threat reactions and promote sociality. World Psychiatry. 2021 Jun;20(2):296-298. https://doi.org10.1002/wps.20871

Röttger, S., Theobald, D. A., Abendroth, J., & Jacobsen, T. (2021). The effectiveness of combat tactical breathing as compared with prolonged exhalation. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 46, 19–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-020-09485-w

Sapolsky, R. (2004). Why zebras don’t get ulcers (3rd ed.). New York:Holt. https://www.amazon.com/Why-Zebras-Dont-Ulcers-Third/dp/0805073698/

Schultz, J. H., & Luthe, W. (1959). Autogenic training: A psychophysiologic approach to psychotherapy. Grune & Stratton. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Autogenic_Training/y8SwQgAACAAJ?hl=en

Selye, H. (1951). The general-adaptation-syndrome. Annual Review of Medicine, 2(1), 327–342. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.me.02.020151.001551

Seo, H. (2023). How to stop ruminating. The New York Times. Accessed January 3, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/01/well/mind/stop-rumination-worry.html

Stroebel, C. F. (1985). QR: The Quieting Reflex. Berkley. https://www.amazon.com/Qr-quieting-reflex-Charles-Stroebel/dp/0425085066

Taylor, S. E., Klein, L. C., Lewis, B. P., Gruenewald, T. L., Gurung, R. A. R., & Updegraff, J. A. (2000). Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: Tend-and-befriend, not fight-or-flight. Psychological Review, 107(3), 411–429. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.107.3.411

Thayer, R. E. (2003). Calm energy: How people regulate mood with food and exercise. Oxford University Press. https://www.amazon.com/Calm-Energy-People-Regulate-Exercise/dp/0195163397

Xin, Q., Bai, B., & Liu, W. (2017). The analgesic effects of oxytocin in the peripheral and central nervous system. Neurochemistry International, 103, 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuint.2016.12.021

Yoga, N. (2023). This simple breath practice is scientifically proven to calm your mind. The nomadic yogi. Accessed December 31, 2023. https://www.leahsugerman.com/blog/bhramari-pranayama-humming-bee-breath#

Is mindfulness training old wine in new bottles?

Posted: January 11, 2024 Filed under: attention, behavior, biofeedback, Breathing/respiration, CBT, cognitive behavior therapy, healing, health, meditation, self-healing, stress management | Tags: anxiety, autogenic training, biofeedback, health, meditation, mental-health, mindfulness, pain, passive attention, progressive muscle relaxation, wellness, yoga Leave a commentAdapted from: Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Lin, I-M. (2019). Mindfulness training has themes common to other technique. Biofeedback. 47(3), 50-57. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-47.3.02

This extensive blog discusses the benefits of mindfulness-based meditation (MM) techniques and explores how similar beneficial outcomes occur with other mind-centered practices such as transcendental meditation, and body-centered practices such as progressive muscle relaxation (PMR), autogenic training (AT), and yoga. For example, many standardized mind-body techniques such as mindfulness-based stress reduction and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (a) are associated with a reduction in symptoms of symptoms such as anxiety, pain and depression. This article explores the efficacy of mindfulness based techniques to that of other self-regulation techniques and identifies components shared between mindfulness based techniques and several previous self-regulation techniques, including PMR, AT, and transcendental meditation. The authors conclude that most of the commonly used self-regulation strategies have comparable efficacy and share many elements.

Mindfulness-based strategies are based in ancient Buddhist practices and have found acceptance as one of the major contemporary behavioral medicine techniques (Hilton et al, 2016; Khazan, 2013). Throughout this blog the term mindfulness will refer broadly to a mental state of paying total attention to the present moment, with a non-judgmental awareness of the inner and/ or outer experiences (Baer et al., 2004; Kabat-Zinn, 1994).

In 1979, Jon Kabat-Zinn introduced a manual for a standardized Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center (Kabat-Zinn, 1994, 2003). The eight-week program combined mindfulness as a form of insight meditation with specific types of yoga breathing and movements exercises designed to focus on awareness of the mind and body, as well as thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

There is a substantial body of evidence that mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT); Teasdale et al., 1995) and mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) (Kabat-Zinn, 1994, 2003) have combined with skills of cognitive therapy for ameliorating stress symptoms such as negative thinking, anxiety and depression. For example, MBSR and MBCT has been confirmed to be clinical beneficial in alleviating a variety of mental and physical conditions, for people dealing with anxiety, depression, cancer-related pain and anxiety, pain disorder, or high blood pressure (The following are only a few of the hundred studies published: Andersen et al., 2013; Carlson et al., 2003; Fjorback et al., 2011; Greeson, & Eisenlohr-Moul, 2014; Hoffman et al., 2012; Marchand, 2012; Baer, 2015; Demarzo et al., 2015; Khoury et al, 2013; Khoury et al, 2015; Chapin et al., 2014; Witek Janusek et al., 2019). Currently, MBSR and MBCT techniques that are more standardized are widely applied in schools, hospitals, companies, prisons, and other environments.

The Relationship Between Mindfulness and Other Self-Regulation Techniques

This section addresses two questions: First, how do mindfulness-based interventions compare in efficacy to older self-regulation techniques? Second, and perhaps more basically, how new and different are mindfulness-based therapies from other self-regulation-oriented practices and therapies?

Is mindfulness more effective than other mind/body body/mind approaches?

Although mindfulness-based meditation (MM) techniques are effective, it does not mean that is is more effective than other traditional meditation or self-regulation approaches. To be able to conclude that MM is superior, it needs to be compared to equivalent well-coached control groups where the participants were taught other approaches such as progressive relaxation, autogenic training, transcendental meditation, or biofeedback training. In these control groups, the participants would be taught by practitioners who were self-experienced and had mastered the skills and not merely received training from a short audio or video clip (Cherkin et al, 2016). The most recent assessment by the National Centere for Complementary and Integrative Health, National Institutes of Health (NCCIH-NIH, 2024) concluded that generally “the effects of mindfulness meditation approaches were no different than those of evidence-based treatments such as cognitive behavioral therapy and exercise especially when they include how to generalize the skills during the day” (NCCIH, 2024). Generalizing the learned skills into daily life contributes to the successful outcome of Autogenic Training, Progressive Relaxation, integrated biofeedback stress management training, or the Quieting Response (Luthe, 1979; Davis et al., 2019; Wilson et al., 2023; Stroebel, 1982).

Unfortunately, there are few studies that compare the effective of mindfulness meditation to other sitting mental techniques such as Autogenic Training, Transcendental Meditation or similar meditative practices that are used therapeutically. When the few randomized control studies of MBSR versus autogenic training (AT) was done, no conclusions could be drawn as to the superior stress reduction technique among German medical students (Kuhlmann et al., 2016).

Interestingly, Tanner, et al (2009) in a waitlist study of students in Washington, D.C. area universities practicing TM used the concept of mindfulness, as measured by the Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills (KIM) (Baer et al, 2004) as a dependent variable, where TM practice resulted in greater degrees of ‘mindfulness.’ More direct comparisons of MM with body-focused techniques, such as progressive relaxation, or Autogenic training mindfulness-based approaches, have not found superior benefit. For example, Agee et al (2009) compared the stress management effects of a five-week Mindfulness Meditation (MM) to a five-week Progressive Muscle Relaxation (PMR) course and found no meaningful reports of superiority of one over the other program; both MM and PMR were effective in reducing symptoms of stress.

In a persuasive meta-analysis comparing MBSR with other similar stress management techniques used among military service members, Crawford, et al (2013) described various multimodal programs for addressing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other military or combat-related stress reactions. Of note, Crawford, et al (2013) suggest that all of the multi-modal approaches that include Autogenic Training, Progressive Muscle Relaxation, movement practices including Yoga and Tai Chi, as well as Mindfulness Meditation, and various types of imagery, visualization and prayer-based contemplative practices ALL provide some benefit to service members experiencing PTSD.

An important observation by Crawford et al (2013) pointed out that when military service members had more physical symptoms of stress, the meditative techniques appeared to work best, and when the chief complaints were about cognitive ruminations, the body techniques such as Yoga or Tai Chi worked best to reduce symptoms. Whereas it may not be possible to say that mindfulness meditation practices are clearly superior to other mind-body techniques, it may be possible to raise questions about mechanisms that unite the mind-body approaches used in therapeutic settings.

Could there be negative side effects?

Another point to consider is the limited discussion of the possible absence of benefit or even harms that may be associated with mind-body therapies. For example, for some people, meditation does not promote prosocial behavior (Kreplin et al, 2018). For other people, meditation can evoke negative physical and/or psychological outcomes (Lindahl et al, 2017; Britton et al., 2021). There are other struggles with mind-body techniques when people only find benefit in the presence of a skilled clinician, practitioner, or guru, suggesting a type of psychological dependency or transference, rather than the ability to generalize the benefits outside of a set of conditions (e.g. four to eight weeks of one to four hour trainings) or a particular setting (e.g. in a natural and/or quiet space).

Whereas the detailed instructions for many mindfulness meditation trainings, along with many other types of mind-body practices (e.g. Transcendental Meditation, Autogenic Training, Progressive Muscle Relaxation, Yoga, Tai Chi…) create conditions that are laudable because they are standardized, a question is raised as to ‘critical ingredients’, using the metaphor of baking. The difference between a chocolate and a vanilla cake is not ingredients such as flour, or sugar, etc., which are common to all cakes, but rather the essential or critical ingredient of the chocolate or vanilla flavoring. So what are the essential or critical ingredients in mind-body techniques? Extending the metaphor, Crawford, et al (2013, p. 20) might say the critical ingredient common to the mind-body techniques they studied was that people “can change the way their body and mind react to stress by changing their thoughts, emotions, and behaviors…” with techniques that, relatively speaking, “involve minimal cost and training time.”

The skeptical view suggested here is that MM techniques share similar strategies with other mind-body approaches that encouraging learners to ‘pay attention and shift intention.’ This strategy is part of the instructions when learning Progressive Relaxation, Autogenic Training, Transcendental Meditation, movement meditation of Yoga and Tai Chi and, with instrumented self-regulation techniques such as bio/neurofeedback. In this sense, MM training repackages techniques that have been available for millennia and thus becomes ‘old wine sold in new bottles.’

We wonder if a control group for compassionate mindfulness training would report more benefits if they were asked not only to meditate on compassionate acts, but actually performed compassionate tasks such as taking care of person in pain, helping a homeless person, or actually writing and delivering a letter of gratitude to a person who has helped them in the past? The suggestion is to titrate the effects of MM techniques, moving from a more basic level of benefit to a more fully actualized level of benefit, generalizing their skill beyond a training setting, as measured by the Baer et al (2004) Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills.

Each generation of clinicians and educators rediscover principles without always recognizing that the similar principles were part of the previous clinical interventions. The analogies and language has changed; however, the underlying concepts may be the same. Mindfulness interventions are now the new, current and popular approach. Some of the underlying ‘mindfulness’ concepts that are shared in common with successfully other mind-body and self-regulation approaches include:

The practitioner must be self-experienced in mindfulness practice. This means that the practitioners do not merely believe the practice is effective; they know it is effective from self-experience. Inner confidence conveyed to clients and patients enhances the healing/placebo effect. It is similar to having sympathy or empathy for clients and patients that occurs from have similar life experiences, such as when a clinician speaks to a patient. For example, a male physician speaking to a female patient who has had a mastectomy may be compassionate; however, empathy occurs more easily when another mastectomy patient (who may also be a physician) shares how she struggled overcame her doubts and can still be loved by her partner.

There may also be a continuum of strengthening beliefs about the benefits of mindfulness techniques that leads to increase benefits for the approach. Knowing there are some kinds of benefits from initiating a practice of mindfulness increases empathy/compassion for others as they learn. Proving that mindfulness techniques are causing benefits after systematically comparing their effectiveness with other approaches strengthens the belief in the mindfulness approaches. Note that a similar process of strengthening one’s belief in an approach occurs gradually, over time as clients and patients progress through beginner, intermediate and advanced levels of mind-body practices.

Observing thoughts without being captured. Being a witness to the thoughts, emotions, and external events results in a type of covert global desensitization and skill mastery of NOT being captured by those thoughts and emotions. This same process of non-attachment and being a witness is one of the underpinnings of techniques that tacitly and sometime covertly support learning ways of controlling attention, such as with Autogenic Training; namely how to passively attend to a specific body part without judgment and, report on the subjective experience without comparison or judgment.

Ongoing daily practice. Participants take an active role in their own healing process as they learn to control and focus their attention. Participants are often asked to practice up to one hour a day and apply the practices during the day as mini-practices or awareness cues to interrupt the dysfunctional behavior. For example in Autogenic training, trainees are taught to practice partial formula (such my “neck and shoulders are heavy”) during the day to bring the body/mind back to balance. While with Progressive Relaxation, the trainee learns to identify when they tighten inappropriate muscles (dysponesis) and then inhibit this observed tension.

Peer support by being in a group. Peer support is a major factor for success as people can share their challenges and successes. Peer support tends to promote acceptance of self-and others and provides role modeling how to cope with stressors. It is possible that some peer support groups may counter the benefits of a mind-body technique, especially when the peers do not provide support or may in fact impede progress when they complain of the obstacles or difficulties in their process.

These concepts are not unique to Mindfulness Meditation (MM) training. Similar instructions have been part of the successful/educational intervention of Progressive Relaxation, Autogenic Training, Yogic practices, and Transcendental Meditation. These approaches have been most successful when the originators, and their initial students, taught their new and evolving techniques to clients and patients; however, they became less successful as later followers and practitioners used these approaches without learning an in-depth skill mastery. For example, Progressive relaxation as taught by Edmund Jacobson consisted of advanced skill mastery by developing subtle awareness of different muscle tension that was taught over 100 sessions (Mackereth & Tomlinson, 2010). It was not simply listening once to a 20-minute audio recording about tightening and relaxing muscles. Similarly, Autogenic training is very specific and teaches passive attention over a three to six-month time-period while the participant practices multiple times daily. Stating the obvious, learning Autogenic Training, Mindfulness, Progressive Relaxation, Bio/Neurofeedback or any other mind-body technique is much more than listening to a 20-minute audio recording.

The same instructions are also part of many movement practices. For many participants focusing on the movement automatically evoked a shift in attention. Their attention is with the task and they are instructed to be present in the movement.

Areas to explore.

Although Mindfulness training with clients and patients has resulted in remarkable beneficial outcomes for the participants, it is not clear whether mindfulness training is better than well taught PR, AT, TM or other mind/body or body/mind approaches. There are also numerous question to explore such as: 1) Who drops out, 2) Is physical exercise to counter sitting disease and complete the alarm reaction more beneficial, and 3) Strategies to cope with wandering attention.

- Who drops out?

We wonder if mindfulness is appropriate for all participants as sometimes participants drop out or experience negative abreactions. It not clear who those participants are. Interestingly, hints for whom the techniques may be challenging can be found in the observations of Autogenic Training that lists specific guidelines for contra-, relative- and non-indications (Luthe, 1970).

- Physical movement to counter sitting disease and complete the alarm reaction.

Although many mindfulness meditation practices may include yoga practices, most participants practice it in a sitting position. It may be possible that for some people somatic movement practices such as a slow Zen walk may quiet the inner dialogue more quickly. In our experience, when participants are upset and highly stressed, it is much easier to let go of agitation by first completing the triggered fight/flight response with vigorous physical activity such as rapidly walking up and downs stairs while focusing on the burning sensations of the thigh muscles. Once the physical stress reaction has been completed and the person feels physically calmer then the mind is quieter. Then have the person begin their meditative practice.

- Strategies to cope with wandering attention.

Some participants have difficulty staying on task, become sleepy, worry, and/or are preoccupied. We observed that first beginning with physical movement practices or Progressive Relaxation appears to be a helpful strategy to reduce wandering thoughts. If one has many active thoughts, progressive relaxation continuously pulls your attention to your body as you are directed to tighten and let go of muscle groups. Being guided supports developing the passive focus of attention to bring awareness back to the task at hand. Once internally quieter, it is easier hold their attention while doing Autogenic Training, breathing or Mindfullness Meditation.

By integrating somatic components with the mindfulness such as done in Progressive Relaxation or yoga practices facilitates the person staying present. Similarly, when teaching slower breathing, if a person has a weight on their abdomen while practicing breathing, it is easier to keep attending to the task: allow the weight to upward when inhaling and feeling the exhalation flowing out through the arms and legs.

Therapeutic and education strategies that implicitly incorporate mindfulness

Progressive relaxation

In the United States during the 1920 progressive relaxation (PR) was developed and taught by Edmund Jacobson (1938). This approach was clinically very successful for numerous illnesses ranging from hypertension, back pain, gastrointestinal discomfort, and anxiety; it included 50 year follow-ups. Patients were active participants and practiced the skills at home and at work and interrupt their dysfunctional patterns during the day such as becoming aware of unnecessary muscle tension (dyponetic activity) and then release the unnecessary muscle tension (Whatmore & Kohli, 1968). This structured approach is totally different than providing an audio recording that guides clients and patients through a series of tightening and relaxing of their muscles. The clinical outcome of PR when taught using the original specific procedures described by Jacobson (1938) was remarkable. The incorporation of Progressive Relaxation as the homework practice was an important cofactor in the successful outcome in the treatment of muscle tension headache using electromyography (EMG) biofeedback by Budzynski, Stoyva and Adler (1970).

Autogenic Training

In 1932 Johannes Schultz in Germany published a book about Autogenic Training describing the basic training procedure. The basic autogenic procedure, the standard exercises, were taught over a minimum period of three month in which the person practiced daily. In this practice they directed theri passive attention to the following cascading sequence: heaviness of their arms, warmth of their arms, heart beat calm and regular, breathing calm and regular or it breathes me, solar plexus is warm, forehead is cool, and I am at peace (Luthe, 1979). Three main principles of autonomic training mentioned by Luthe (1979) are: (1) mental repetition of topographically oriented verbal formulae for brief periods; (2) passive concentration; and (3) reduction of exteroceptive and proprioceptive afferent stimulation. The underlying concepts of Autogenic Therapy include as described by Peper and Williams (1980):

The body has an innate capacity for self-healing and it is this capacity that is allowed to become operative in the autogenic state. Neither the trainer nor trainee has the wisdom necessary to direct the course of the self-balancing process; hence, the capacity is allowed to occur and not be directed.

- Homeostatic self-regulation is encouraged.

- Much of the learning is done by the trainee at home; hence, the responsibility for the training lies primarily with the trainee.

- The trainer/teacher must be self-experience in the practice.

- The attitude necessary for successful practice is one of passive attention; active striving and concern with results impedes the learning process. An attitude of acceptance is cultivated, letting be whatever comes up. This quality of attention is known as “mindfulness’ in meditative traditions.

The clinical outcome for autogenic therapy is very promising. The detailed guided self-awareness training and uncontrolled studies showed benefits across a wide variety of psychosomatic illness such as asthma, cancer, hypertension, anxiety, pain irritable bowel disease, depression (Luthe & Schultz, 1970a; Luthe & Schultz, 1970b). Autogenic training components have also been integrated in biofeedback training. Elmer and Alice Green included the incorporation of autogenic training phrases with temperature biofeedback for the very successful treatment of migraines (Green & Green, 1989). Autonomic training combine with biofeedback in clinical practices produced better results than control group for headache population (Luthe, 1979). Empirical research found that autonomic training was applied efficiently in emotional and behavioral problems, and physical disorder (Klott, 2013), such as skin disorder (Klein & Peper, 2013), insomnia (Bowden et al., 2012), Meniere’s disease (Goto, Nakai, & Ogawa, 2011) and the multitude of stress related symptoms (Wilson et al., 2023).

Bio/neurofeedback training

Starting in the late 1960s, biofeedback procedures have been developed as a successful treatment approach for numerous illnesses ranging from headaches, hypertension, to ADHD (Peper et al., 1979; Peper & Shaffer, 2010; Khazan, 2013). In most cases, the similar instructions that are part of mindfulness meditation are also embedded in the bio/neurofeedback instructions. The participants are instructed to learn control over some physiological parameter and then practice the same skill during daily life. This means that during the learning process, the person learn passive attention and is not be captured by marauding thoughts and feeling. and during the day develop awareness Whenever they become aware of dysfunctional patterns, thoughts, emotions, they initiated their newly learned skill. The ongoing biological feedback signals continuously reminds them to focus.

Transcendental meditation

The next fad to hit the American shore was Transcendental Meditation (TM)– a meditation practice from the ancient Vedic tradition in India. The participant were given a mantra that they mentally repeated and if their attention wanders, they go back to repeating the mantra internally. The first study that captured the media’s attention was by Wallace (1970) published in the Journal Science which reported that “During meditation, oxygen consumption and heart rate decreased, skin resistance increased, and the electroencephalogram showed specific changes in certain frequencies. These results seem to distinguish the state produced by Transcendental Meditation from commonly encountered states of consciousness and suggest that it may have practical applications.” (Wallace, 1970).

The participants were to practice the mantra meditation twice a day for about 20 minutes. Meta-analysis studies have reported that those who practiced TM as compared to the control group experienced significant improved of numerous disorders such as CVD risk factors, anxiety, metabolic syndrome, drug abuse and hypertension (Paul-Labrador et al, 2006; Rainforth et al., 2007; Hawkins, 2003).

To make it more acceptable for the western audience, Herbert Benson, MD, adapted and simplified techniques from TM training and then labelled a core element, the ‘relaxation response’ (Benson et al., 1974) Instead of giving people a secret mantra and part of a spiritual tradition, he recommend using the word “one” as the mantra. Numerous studies have demonstrated that when patients practice the relaxation response, many clinical symptoms were reduced. The empirical research found that practiced transcendental meditation caused increasing prefrontal low alpha power (8-10Hz) and theta power of EEG; as well as higher prefrontal alpha coherence than other locations at both hemispheres. Moreover, some individuals also showed lower sympathetic activation and higher parasympathetic activation, increased respiratory sinus arrhythmic and frontal blood flow, and decreased breathing rate (Travis, 2001, 2014). Although TM and Benson’s relaxation response continues to be practiced, mindfulness has taking it place.

Conclusion

Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) are very beneficial and yet may be considered ‘old wine in new bottles’ where the metaphor refers to millennia old meditation techniques as ‘old wine’ and the acronyms such as MBSR or MBCT as ‘new bottles’. Like many other ‘new’ therapeutic approaches or for that matter, many other ‘new’ medications, use it now before it becomes stale and loses part of its placebo power. As long as the application of a new technique is taught with the intensity and dedication of the promotors of the approach, and as long as the participants are required to practice while receiving support, the outcomes will be very beneficial, and most likely similar in effect to other mind-body approaches.

The challenge facing mindfulness practices just as those from Autogenic Training, Progressive Relaxation and Transcendental Meditation, is that familiarity breeds contempt and that clients and therapists are continuously looking for a new technique that promises better outcome. Thus as Mindfulness training is taught to more and more people, it may become less promising. In addition, as mindfulness training is taught in less time, (e.g. fewer minutes and/or fewer sessions), and with less well-trained instructors, who may offer less support and supervision for people experiencing possible negative effects, the overall benefits may decrease. Thus, mindfulness practice, Autogenic training, progressive relaxation, Transcendental Meditation, movement practices, meditation, breathing practices as well as the many spiritual practices all appear to share common fate of fading over time. Whereas the core principles of mind-body techniques are ageless, the execution is not always assured.

References

Agee, J. D., Danoff-Burg, S., & Grant, C. A. (2009). Comparing brief stress management courses in a community sample: Mindfulness skills and progressive muscle relaxation. Explore: The Journal of Science and Healing, 5(2), 104-109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.explore.2008.12.004

Andersen, S. R., Würtzen, H., Steding-Jessen, M., Christensen, J., Andersen, K. K., Flyger, H., … & Dalton, S. O. (2013). Effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction on sleep quality: Results of a randomized trial among Danish breast cancer patients. Acta Oncologica, 52(2), 336-344. https://doi.org/10.3109/0284186X.2012.745948

Alvarez-Jimenez, M., Gleeson, J. F., Bendall, S., Penn, D. L., Yung, A. R., Ryan, R. M., … Nelson, B. (2018). Enhancing social functioning in young people at Ultra High Risk (UHR) for psychosis: A pilot study of a novel strengths and mindfulness-based online social therapy. Schizophrenia Research, 202, 369-377 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2018.07.022

Baer, R. A. (2003). Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10, 125–143. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy/bpg015

Baer, R. A.. (2015). Mindfulness-based treatment approaches: Clinician’s guide to evidence base and applications. New York: Elsevier. https://www.elsevier.com/books/mindfulness-based-treatment-approaches/baer/978-0-12-416031-6

Baer, R., Smith, G., & Allen, K. (2004). Assessment of mindfulness by self-report: The Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills. Assessment, 11, 191–206. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191104268029

Benson, H., Beary, J. F., & Carol, M. P. (1974).The Relaxation Response. Psychiatry, 37(1), 37-46. https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/upsy20

Bowden, A., Lorenc, A., & Robinson, N. (2012). Autogenic Training as a behavioural approach to insomnia: A prospective cohort study. Primary Health Care Research & Development, 13, 175-185. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1463423611000181

Britton, W.B., Lindahl, J.R., Coope, D.J., Canby, N.K., & Palitsky, R. (2021). Defining and Measuring Meditation-Related Adverse Effects in Mindfulness-Based Programs. Clinical Psychological Science, 9(6), 1185-1204. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702621996340

Budzynski, T., Stoyva, J., & Adler, C. (1970). Feedback-induced muscle relaxation: Application to tension headache. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 1(3), 205-211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7916(70)90004-2

Carlson, L. E., Speca, M., Patel, K. D., & Goodey, E. (2003). Mindfulness‐based stress reduction in relation to quality of life, mood, symptoms of stress, and immune parameters in breast and prostate cancer outpatients. Psychosomatic Medicine, 65(4), 571-581. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.psy.0000074003.35911.41

Chapin, H. L., Darnall, B. D., Seppala, E. M., Doty, J. R., Hah, J. M., & Mackey, S. C. (2014). Pilot study of a compassion meditation intervention in chronic pain. J Compassionate Health Care, 1(4), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40639-014-0004-x

Cherkin, D. C., Sherman, K. J., Balderson, B. H., Cook, A. J., Anderson, M. L., Hawkes, R. J., … & Turner, J. A. (2016). Effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction vs cognitive behavioral therapy or usual care on back pain and functional limitations in adults with chronic low back pain: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 315(12), 1240-1249. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.2323

Crawford, C., Wallerstedt, D. B., Khorsan, R., Clausen, S. S., Jonas, W. B., & Walter, J. A. (2013). A systematic review of biopsychosocial training programs for the self-management of emotional stress: Potential applications for the military. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 747694: 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/747694

Davis, M., Eshelman, E.R., & McKay, M. (2019). The Relaxation and Stress Reduction Workbook. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications. https://www.amazon.com/Relaxation-Reduction-Workbook-Harbinger-Self-Help/dp/1684033349

Demarzo, M. M., Montero-Marin, J., Cuijpers, P., Zabaleta-del-Olmo, E., Mahtani, K. R., Vellinga, A., Vincens, C., Lopez del Hoyo, Y., & García-Campayo, J. (2015). The efficacy of mindfulness-based interventions in primary care: A meta-analytic review. The Annals of Family Medicine, 13(6), 573-582. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1863

Fjorback, L. O., Arendt, M., Ørnbøl, E., Fink, P., & Walach, H. (2011). Mindfulness‐Based Stress Reduction and Mindfulness‐Based Cognitive Therapy–A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 124(2), 102-119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01704.x

Goto, F., Nakai, K., & Ogawa, K. (2011). Application of autogenic training in patients with Meniere disease. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, 268(10), 1431-1435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-011-1530-1

Greeson, J., & Eisenlohr-Moul, T. (2014). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for chronic pain. In R. A. Baer (Ed.), Mindfulness-Based Treatment Approaches: Clinician’s Guide to Evidence Base and Applications, 269-292. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2014-40932-000

Green, E. and Green, A. (1989). Beyond Biofeedback. New York: Knoll. https://www.amazon.com/Beyond-Biofeedback-Elmer-Green/dp/0940267144

Hawkins, M. A. (2003). Effectiveness of the Transcendental Meditation program in criminal rehabilitation and substance abuse recovery. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 36(1-4), 47- 65. https://doi.org/10.1300/J076v36n01_03

Hilton, L., Hempel, S., Ewing, B. A., Apaydin, E., Xenakis, L., Newberry, S., …Maglione, M. A. (2016). Mindfulness meditation for chronic pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 51(2), 199-213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-016-9844-2

Hoffman, C. J., Ersser, S. J., Hopkinson, J. B., Nicholls, P. G., Harrington, J. E., & Thomas, P. W. (2012). Effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction in mood, breast-and endocrine-related quality of life, and well-being in stage 0 to III breast cancer: A randomized, controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 30(12), 1335-1342. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2010.34.0331

Jacobson, E. (1938). Progressive relaxation. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. https://www.amazon.com/Progressive-Relaxation-Physiological-Investigation-Significance/dp/0226390594

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1994). Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. New York: Hyperion. https://www.amazon.com/Wherever-You-There-Are-Mindfulness/dp/0306832011

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). Constructivism in the Human Sciences, 8, 73–107. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2004-19791-008

Khazan, I. Z. (2013). The clinical handbook of biofeedback: A step-by-step guide for training and practice with mindfulness. New York: John Wiley & Sons. https://www.amazon.com/Clinical-Handbook-Biofeedback-Step-Step/dp/1119993717

Klein, A., & Peper, E. (2013). There Is hope: Autogenic biofeedback training for the treatment of psoriasis. Biofeedback, 41 (4), 194-201. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-41.4.01

Khoury, B., Lecomte, T., Fortin, G., Masse, M., Therien, P., Bouchard, V., Chapleau, M., Paquin, K., & Hofmann, S. G. (2013). Mindfulness-based therapy: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(6), 763-771. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2013.05.005

Khoury, B., Sharma, M., Rush, S. E., & Fournier, C. (2015). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for healthy individuals: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 78(6), 519-528.

Klott, O. (2013). Autogenic Training–a self-help technique for children with emotional and behavioural problems. Therapeutic Communities: The International Journal of Therapeutic Communities, 34(4), 152-158. https://doi.org/10.1108/TC-09-2013-0027

Kreplin, U., Farias, M., & Brazil, I. A. (2018). The limited prosocial effects of meditation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep, 8, 2403. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-20299-z

Kuhlmann, S. M., Huss, M., Bürger, A., & Hammerle, F. (2016). Coping with stress in medical students: results of a randomized controlled trial using a mindfulness-based stress prevention training (MediMind) in Germany. BMC Medical Education, 16(1), 316. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0833-8

Lindahl, J. R., Fisher, N. E., Cooper, D. J., Rosen, R. K, & Britton, W. B. (2017). The varieties of contemplative experience: A mixed-methods study of meditation-related challenges in Western Buddhists. PLoSONE, 12(5): e0176239. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0176239

Luthe, W. (1970). Autogenic therapy: Research and theory. New York: Grune and Stratton. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/the-british-journal-of-psychiatry/article/abs/autogenic-therapy-edited-by-wolfgang-luthe-volume-4-research-and-theory-by-wolfgang-luthe-grune-and-stratton-new-york-1970-pp-276-price-1475/6C8521C36C37254A08AAD1F2FE08211C

Luthe, W. (1979). About the Methods of Autogenic Therapy. In: Peper, E., Ancoli, S., Quinn, M. (eds). Mind/Body Integration. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4613-2898-8_12

Luthe, W. & Schultz, J. H. (1970a). Autogenic therapy: Medical applications. New York: Grune and Stratton. https://www.amazon.com/Autogenic-Therapy-II-Medical-Applications/dp/B001J9W7L6

Luthe, W. & Schultz, J. H. (1970b). Autogenic therapy: Applications in psychotherapy. New York: Grune and Stratton. https://www.amazon.com/Autogenic-Therapy-Applications-Psychotherapy-v/dp/0808902725

Mackereth, P.A. & Tomlinson, L. (2010). Progressive muscle relaxation. In Cawthorn, A. & Mackereth, P.A. eds. Integrative Hypnotherapy. London: Churchill Livingstone. https://www.amazon.com/Integrative-Hypnotherapy-Complementary-approaches-clinical/dp/0702030821

Marchand, W. R. (2012). Mindfulness-based stress reduction, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, and Zen meditation for depression, anxiety, pain, and psychological distress. Journal of Psychiatric Practice, 18(4), 233-252. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.pra.0000416014.53215.86

NCCIH (2024). Meditation and Mindfulness: What You Need To Know. National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, National Institutes of Health. Accessed January 31, 2024. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/meditation-and-mindfulness-what-you-need-to-know?

Paul-Labrador, M., Polk, D., Dwyer, J.H. et al. (2006). Effects of a randomized controlled trial of Transcendental Meditation on components of the metabolic syndrome in subjects with coronary heart disease. Archive of Internal Medicine, 166(11), 1218-1224. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.11.1218

Peper, E., Ancoli, S. & Quinn, M. (Eds). (1979). Mind/Body Integration: Essential Readings in Biofeedback. New York: Plenum. https://www.amazon.com/Mind-Body-Integration-Essential-Biofeedback/dp/0306401029

Peper, E. & Shaffer, F. (2010). Biofeedback History: An Alternative View. Biofeedback, 38 (4): 142–147. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-38.4.03

Peper, E., & Williams, E.A. (1980). Autogenic therapy. In A. C. Hastings, J. Fadiman, & J. S. Gordon (Eds.), Health for the whole person (pp137-141).. Boulder: Westview Press. https://biofeedbackhealth.files.wordpress.com/2016/02/autogenic-therapy-peper-and-williams.pdf

Rainforth, M.V., Schneider, R.H., Nidich, S.I., Gaylord-King, C., Salerno, J.W., & Anderson, J.W. (2007). Stress reduction programs in patients with elevated blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Current Hypertension Reports, 9(6), 520–528. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-007-0094-3

Stroebel, C. (1982). QR: The Quieting Reflex. New York: Putnam Pub Group. https://www.amazon.com/Qr-Quieting-Charles-M-D-Stroebel/dp/0399126570

Tanner, M. A., Travis, F., Gaylord‐King, C., Haaga, D. A. F., Grosswald, S., & Schneider, R. H. (2009). The effects of the transcendental meditation program on mindfulness. Journal of Clinical Psychology 65(6), 574-589. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20544

Teasdale, J. D., Segal, Z., & Williams, J. M. (1995). How does cognitive therapy prevent depressive relapse and why should attentional control (mindfulness) training help? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33, 25–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)e0011-7

Travis, F. (2001). Autonomic and EEG patterns distinguish transcending from other experiences during transcendental meditation practice. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 42, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-8760(01)00143-x

Travis, F. (2014). Transcendental experiences during meditation practice. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1307, 1–8. https://doi.og10.1111/nyas.12316

Wallace, K.W. (1970). Physiological Effects of Transcendental Meditation. Science, 167 (3926), 1751-1754. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.167.3926.1751

Whatmore, G. B., & Kohli, D. R. (1968). Dysponesis: A neurophysiologic factor in functional disorders. Behavioral Science, 13(2), 102–124. https://doi.org/10.1002/bs.3830130203

Wilson, V., Somers, K. & Peper, E. (2023). Differentiating Successful from Less Successful Males and Females in a Group Relaxation/Biofeedback Stress Management Program. Biofeedback, 51(3), 53–67. https://doi.org/10.5298/608570

Witek Janusek, L., Tel,l D., & Mathews, H.L. (2019). Mindfulness based stress reduction provides psychological benefit and restores immune function of women newly diagnosed with breast cancer: A randomized trial with active control. Brain Behav Immun, 80:358-373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2019.04.012

Happy New Year: Explore the positive

Posted: December 26, 2017 Filed under: stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: Confidence, health, hope, Inspiration, peak performance 2 CommentsAs the New Year begins, I wish you health, happiness and the courage to follow your dreams. Even though we may face challenges, they are also the gateway to new opportunities. Within each person there are unknown potentials which are so often limited by our beliefs. Enjoy the video that points out there is nothing more powerful than a human being with a dream. Best wishes for the New Year.

Link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IWLZ2b158HI&feature=player_embedded

Breathing to improve well-being

Posted: November 17, 2017 Filed under: Breathing/respiration, Exercise/movement, Neck and shoulder discomfort, Pain/discomfort, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: anxiety, Breathing, health, mindfulness, pain, respiration, stress 8 CommentsBreathing affects all aspects of your life. This invited keynote, Breathing and posture: Mind-body interventions to improve health, reduce pain and discomfort, was presented at the Caribbean Active Aging Congress, October 14, Oranjestad, Aruba. www.caacaruba.com

The presentation includes numerous practices that can be rapidly adapted into daily life to improve health and well-being.

First do no harm: Listen to Freakonomics Radio Episodes Bad Medicine

Posted: September 3, 2017 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: health, Medicine, pharmaceuticals, placebo, treatment 1 Comment

How come up to 250,000 people a year die of medical errors and is the third leading cause of death in the USA (Makary & Daniel, 2016)?

Why are some drugs recalled after years of use because they did more harm than good?

How come arthroscopic surgery continues to be done for osteoarthritis of the knee even though it is no more beneficial than mock surgery (Moseley et al, 2002)?

How come women have more negative side effects from Ambien and other sleep aids than men?

Is it really true that the average new cancer drug costs about $100,000 for treatment and usually only extends the life of the selected study participants by about two months (Szabo, 2017; Fojo, Mailankody, & Lo, 2014)?

“It is simply no longer possible to believe much of the clinical research that is published, or to rely on the judgment of trusted physicians or authoritative medical guidelines. I take no pleasure in this conclusion, which I reached slowly and reluctantly over my two decades as an editor of the New England Journal of Medicine”—Dr. Marcia Angell, longtime Editor in Chief of the New England Medical Journal (Angell, 2009).

Medical discoveries have made remarkable improvements in our health. The discovery of insulin in 1921 by Canadian physician Frederick Banting and medical student Charles H. Best allowed people with Type 1 Diabetes to live healthy productive lives (Rosenfeld, 2002). Cataract lens replacement surgery is performed more than three million times per year and allows millions of people to see better even though a few patients have serious side negative side effects. And, there appears to be new hope for cancer. The FDA on August 30, 2017, approved a new individualized cancer treatment that uses genetically engineered cells from a patient’s immune system to produce remissions in 83 percent of the children and young adults who have relapsed after undergoing standard treatment for B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. (FDA August 30, 2017). The one-time treatment for this breakthrough cancer drug for patients who respond costs $475,000 according to the manufacturer Novartis. Yet, it will be years before we know if there are long term negative side effects.

The cost of this treatment is much more than the average cost of $100,000 for newly developed and approved cancer drugs which at best extend the life of highly selected patients on the average by two months; however, when they used with more typical Medicare patients, these drugs often offer little or no increased benefits (Szabo, 2017; Freakonomics Radio episode Bad Medicine, Part 2: (Drug) Trials and Tribulations).

As the health care industry is promising new screening, diagnostic and treatment approaches especially through direct-to-consumer advertising, they may not always be beneficial and, in some cases, may cause harm. The only way to know if a diagnostic or treatment procedure is beneficial is to do long term follow-up; namely, did the treated patients live longer, have fewer complications and better quality of life than the non-treatment randomized control patients. Just because a surrogate illness markers such as glucose level for type 2 Diabetes or blood pressure for essential hypertension decrease in response to treatment, it does not always mean that the patients will have fewer complications or live longer.

To have a better understanding of the complexity and harm that can occur from medical care, listen to the following three Freakonomics Radio episodes titled Bad Medicine.

Freakonomics Radio episode Bad Medicine, Part 1: The story of 98.6. We tend to think of medicine as a science, but for most of human history it has been scientific-ish at best. In the first episode of a three-part series, we look at the grotesque mistakes produced by centuries of trial-and-error, and ask whether the new era of evidence-based medicine is the solution. http://freakonomics.com/podcast/bad-medicine-part-1-story-98-6/

Freakonomics Radio episode Bad Medicine, Part 2: (Drug) Trials and Tribulations. How do so many ineffective and even dangerous drugs make it to market? One reason is that clinical trials are often run on “dream patients” who aren’t representative of a larger population. On the other hand, sometimes the only thing worse than being excluded from a drug trial is being included. http://freakonomics.com/podcast/bad-medicine-part-2-drug-trials-and-tribulations/

Freakonomics Radio episode, Bad Medicine, Part 3: Death by Diagnosis. By some estimates, medical error is the third-leading cause of death in the U.S. How can that be? And what’s to be done? Our third and final episode in this series offers some encouraging answers. http://freakonomics.com/podcast/bad-medicine-part-3-death-diagnosis/

References

Angell M. Drug companies and doctors: A story of corruption. January 15, 2009. The New York Review of Books 56. Available: http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2009/jan/15/drug-companies-doctorsa-story-of-corruption/. Accessed 24, November, 2016.

FDA approval brings first gene therapy to the United States, August 30, 2017. https://www.fda.gov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm574058.htm

Makary, M. A., & Daniel, M. (2016). Medical error-the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ: British Medical Journal (Online), 353. Listen to his BMJ medical talk: https://soundcloud.com/bmjpodcasts/medical-errorthe-third-leading-cause-of-death-in-the-us

Rosenfeld, L. (2002). Insulin: discovery and controversy. Clinical chemistry, 48(12), 2270-2288. http://clinchem.aaccjnls.org/content/48/12/2270

Szabo, L. (201, February 9). Dozens of new cancer drugs do little to improve survival. Kaiser Health News. Downloaded September 3, 2017. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2017/02/09/new-cancer-drugs-do-little-improve-survival/97712858/

Sitting disease is the new health hazard

Posted: July 29, 2017 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: exercise, health, posture, sitting 7 Comments Sedentary behavior is the new norm as most jobs do not require active movement. Sitting in a car instead of walking, standing on the escalator instead of walking up the stairs, using an electric mixer instead of whipping the eggs by hand, sending a text instead of getting up and talking to a co-worker in the next cubicle, buying online instead of walking to the brick and mortar store, watching TV shows, streaming movies, or playing computer games instead of socializing with actual friends, are all examples how the technological revolution has transformed our lives. The result is sitting disease which we belief can mitigate by daily exercise.

Sedentary behavior is the new norm as most jobs do not require active movement. Sitting in a car instead of walking, standing on the escalator instead of walking up the stairs, using an electric mixer instead of whipping the eggs by hand, sending a text instead of getting up and talking to a co-worker in the next cubicle, buying online instead of walking to the brick and mortar store, watching TV shows, streaming movies, or playing computer games instead of socializing with actual friends, are all examples how the technological revolution has transformed our lives. The result is sitting disease which we belief can mitigate by daily exercise.

The research data is very clear– exercise does not totally reverse the health risks of sitting. In the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study, researchers Matthews and colleagues (Matthews et al, 2012) completed an 8.5 year follow up on 240,819 adults (aged 50–71 year) who at the beginning baseline surveys did not report any cancer, cardiovascular disease, or respiratory disease.

The 8.5 year outcome data showed that the time spent in sedentary behaviors such as sitting and watching TV was positively correlated with an increased illness and death rates as shown in Figure 1. More disturbing, moderate vigorous exercises does not totally reverse the health risks of sitting and watching television (Matthews et al, 2012).

Figure 1. The more you sit the higher the risk of mortality even if you if you attempt to mitigate the effect with moderate vigorous exercise (Matthews et al, 2012). From: https://www.washingtonpost.com/apps/g/page/national/the-health-hazards-of-sitting/750/

The harmful impact of sedentary behavior and simple ways to improve health have been superbly described and illustrated by Bonnie Berkowitz and Patterson Clark (2014), in their January 20, 2014, Washington Post article, The health hazards of sitting, Their one page poster should be posted on the office walls and given to all clients. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/special/health/sitting/Sitting.pdf

As they point out, sitting disease increases the risk of heart disease, diabetes, colon cancer, muscle degeneration especially weaker abdominal muscles and gluteus muscles, back pain and reduced hip flexibility, poor circulation in the legs which may cause edema in the ankles and deep vein thrombosis, osteoporosis, strained neck, shoulder and back pain. The effects are not only physical. Sitting reduces subjective energy level and attention as our brain becomes more and more sleepy.

The solution is both very simple and challenging. To reduce the risks, do less sedentary behavior and sitting and do more physical movement during the day. Continuously interrupt sitting with standing and movement. After sitting at the computer for 30 minutes, get up and move. Even skipping in place for 30 seconds, significantly will increase your energy and mood (Peper and Lin, 2012). There are many ways to remind and support yourself and others to move. For example, use reminder programs on the computer such as StretchBreakTM to remind you to get up and stretch. Employees who do episode movements, report fewer symptoms and have more energy (Peper & Harvey, 2008). As one of the employees state after implementing the break program, “There is life after five.” Meaning he was no longer exhausted when he finished work.

Although challenging, wean yourself away from the addicting digital screen and being a couch potato at home. At those moments when you feel drained and all you want to do is veg out by watching another TV series, go for a walk. After walking for 20 minutes, in most cases your energy will have returned and your low mood has been transformed to see new positive option. Plan the walks with neighbors and friends who provide the motivation to pull you out of your funk and go out.

References: