360-Degree Belly Breathing with Jamie McHugh

Posted: April 26, 2024 Filed under: attention, Breathing/respiration, emotions, healing, health, meditation, mindfulness, Pain/discomfort, relaxation, self-healing | Tags: abdominal braething, belly breathing, daiphragm, effortless breathing, passive attention, self-acceptance, somatic awreness 1 Comment

Breathing is a whole mind-body experience and reflects our physical, cognitive and emotional well-being. By allowing the breath to occur effortlessly, we provide ourselves the opportunity to regenerate. Although there are many directed breathing practices that specifically directs us to inhale or exhale at specific rhythms or depth to achieve certain goals, healthy breathing is whole body experience. Many focus on being paced at a specific rhythm such as 5.5 breath per minute; however, effortless breathing is dynamic and constantly changing. It is contstantly adapting to the body’s needs: sometimes the breath is slightly slower, sometimes slightly faster, sometimes slightly deeper, sometimes slightly more shallower. The breathing process is effortless. This process can be described by the Autogenic training phrase, “It breathes me” (Luthe, 1969; Luthe, 1979; Luthe & de Rivera, 2015). Read the essay by Jamie McHugh, Registered Master Somatic Movement Therapist and then let yourself be guided in this non-striving somatic approach to allow effortless 360 degree belly breathing for regeneration.

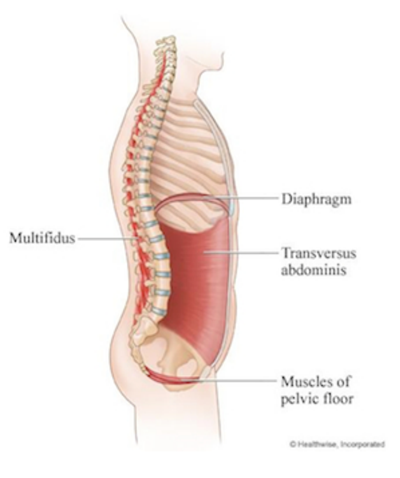

The 360 degree belly breathing by Jamie McHugh, MSMT, is a somatic exploration to experience that breathing is not just abdominal breathing by letting the belly expand forward, but a rhythmic 360 degree increase and decrease in abdominal volume without effort. This effortless breathing pattern can often be observed in toddlers when they sit peacefully erect on the floor. This pattern of breathing not only enhances gas exchange, more importantly, it enhances abdominal blood and lymph circulation.

“The usual psychodynamic foundation for the self-experience is that of hunger, not breath. The body is experienced as an alien entity that has to be kept satisfied; the way an anxious mother might experience a new baby. When awareness is shifted from appetite to breath, the anxieties about not being enough are automatically attenuated. It requires a settling down or relaxing into one’s own body. When this fluidity moves to the forefront of awareness…there is a relaxation of the tensed self…and the emergence of a simpler, breath-based self that is capable of surrender to the moment.” – Mark Epstein (2013).

The intention behind 360 Degree Belly Breathing is to access and express the movement of the breath in all three dimensions. This is the basis for all subsequent somatic explorations within the Embodied Mindfulness protocol, a body-based approach to traditional meditation practices I have developed over the past 20 years (McHugh, 2016). Embodied Mindfulness explores the inner landscape of the body with the essential somatic technologies of breath, vocalization, self-contact, stillness and subtle movement. We focus and sustain mental attention while pleasurably cultivating bodily calm and clarity as a daily practice for survival in these turbulent times. Coupled with individual variations and experimentation, this practice becomes a reliable sanctuary from overwhelm, scattered attention, and emotional turmoil.

The Central Diaphragm

The central diaphragm, a dome-shaped muscular sheath that divides the thorax (chest) and the abdomen (belly), is the primary mechanism for breathing. It is the floor for your heart and lungs and the ceiling for your belly. The central diaphragm is a mostly impenetrable divide, with a few openings through it for the aorta, vena cava and the esophagus. Each time you inhale, the diaphragm contracts and flattens out a bit as it presses down towards your pelvis. Each time you exhale, the diaphragm relaxes and floats back up towards your heart. The motion of the diaphragm impacts the barometric pressure in your chest: the downward movement of the diaphragm on the inhale pulls oxygen into your lungs, and the subsequent exhale expels carbon dioxide into the world as the diaphragm releases upwards.

The movement of the diaphragm is twofold: involuntary and voluntary. Involuntary, ordinary breathing is a homebase and a point of return. Breathing just automatically happens – you don’t have to think about it. Breathing is also voluntary; you can choose to change the tempo (quick or slow), the duration (short or long) and quality (smooth or sharp) of this movement to “charge up and chill out” at will. Knowing how to collaborate with your diaphragm, discovering your own rhythm of diaphragmatic action, and undulating between the automatic and the chosen is a foundation for physiological equilibrium and emotional “self-soothing”.

Watch these two brief videos to get a visual image of your diaphragm in motion:

Beginning Sitting Practice

“When your back becomes straight, your mind will become quiet.” – Shunryu Suzuki

What does it mean to have a “straight back”? What are the inner coordinates and outer parameters of this position in space? And what kind of environment is needed to support this uprightness? This simple orientation to sitting can create more comfort, ease and support in your structure, which will stimulate more fluidity in your breathing and your thinking.

As you sit on a chair, consider two points of focus: body and environment. Can I sit upright with ease and comfort on this chair? If not, what changes can I make with my body and how can I adapt the environment of this chair to meet my needs? Since we are all various heights, it is not surprising a one-size-fits-all chair would need adaptation. Don’t be content with your first solution – experiment until you find just the right configuration. Valuing and seeking bodily comfort and ease are simple yet profound acts of self-kindness.

Do you need to move your pelvis forward on the chair or back? If you move your pelvis back, do you get the necessary support from the back of the chair for your pelvic bowl? If the back of the chair is too far away and/or makes you lean back into space, place a small cushion or two between the back of the chair and the base of your spine. With your back supported, are your feet on the floor? If not, place a folded blanket or a cushion under them.

With pelvis and feet in place, take a few full breaths to stabilize your pelvis and let your weight drop down through your sitz bones into the chair. The upper body receives more support from the core muscles of the lower body when your center of gravity drops – you don’t have to work so hard to maintain uprightness. Finally, rock on your sitz bones forward, backward, and side-to-side. Movement awakens bodily feedback so you can feel where center is in this moment. That sense of center will continue to change throughout the duration of the practice period so feel free to periodically adjust your position.

After this initial structural orientation, the next step is attending to the combination of breath and self-contact to fill out our self-perception. Self-contact is like using a magnifying glass – focusing the mind by feeling the substance of the belly’s movement in our hands. Since the diaphragm is a 360-degree phenomenon that generates movement in our sides and our back as well as our front, spreading awareness out not only creates different patterns of muscular activation – it also changes the brain’s map of the body and how we perceive ourselves. This change of orientation over time recalibrates our alignment and how we settle in ourselves, with awareness of our back in equal proportion to our front and sides.

360-Degree Belly Breath

“To stop your mind does not mean to stop the activities of the mind. It means your mind pervades your whole body.” – Shunryu Suzuki

Read text below or be guided by the audio file or YouTube video. http://somaticexpression.com/classes/360DegreeBreathingwithJamieMcHugh.mp3

Sit comfortably and place your hands on the front of your belly. With each inhale, become aware of the forward movement of your belly swelling. Then, with each exhale, notice the release of your belly and the settling back to center. Give this action and each subsequent action at least 5-7 breath cycles. Intersperse this way of breathing with ordinary, effortless breathing by letting the body breathe automatically. Return time and again to ordinary breathing, letting go of the focus and the effort to rest in the aftermath.

Now, slide your hands to the sides of your belly. Notice with each breath cycle how your belly moves laterally out to the sides on the inhale and then settles back to center again on the exhale.

Now, slide your hands to the back of your belly. You may wish to make contact with the back of your hands instead of your palms if it is more comfortable. With each inhale, focus on the movement into the backspace – this will be much smaller than the movement to the front; and with each exhale, the movement settling back to center.

Finally, connect all three directions: your belly radiates out 360 degrees on the horizon with each inhale, simultaneously moving forward, backward, and out to both sides, and then settles inward with each exhale.

Finish with open awareness – scanning your whole inner landscape from feet to head, back to front, and center to extremities, and letting your body breathe itself, as you notice what is alive in you now.

Inhale – Belly Radiates Outwards; Exhale – Belly Settles Inwards

“The belly is an extraordinary diagnostic instrument. It displays the armoring of the heart as a tension in the belly. Trying tightens the belly. Trying stimulates judgment. Hard belly is often judging belly. Observing the relative openness or closedness of the belly gives insight into when and how we are holding (on) to our pain. The deeper our relationship to the belly, the sooner we discover if we are holding in the mind or opening into the heart.” – Steven Levine (1991)

The contact of your hands on your belly helps the mind pay attention to the subtle movement created by the inhale-exhale cycle of the diaphragm. The combination of tactility and interoceptive awareness focusing on the belly shifts attention into our “second brain” (the enteric nervous system) and signals the mind it can rest and soften. More pleasurable sensation is often accompanied by an emergent feeling of safety as you settle into sensing the rhythm of a slower, more even breath, creating a feedback loop between bodily/somatic ease and mental calm. Giving yourself some daily “breathing room” in this way can help you build the calm muscle!

Naturally, there can be hiccups along the way so it is not all unicorns and rainbows! By giving the mind bodily tasks to accomplish, particularly in relationship to deepening and expanding the movement of the breath, we ease the self into a slower, more receptive state of being. Yet, in this receptive state of ease, whatever is in the background of awareness can arise and slip through the “border control”, sometimes taking us by surprise and causing distress. Depending upon the nature of the information, there are layers of action strategies that can be progressively taken to modulate and buffer what arises:

Tether your awareness to the breath rhythm with hands on your belly to stay present as a witness. Next step up: open your eyes softly and look around to orient in your present environment. Further step up: breath flow, hands-on belly, eyes open a wee bit looking around, and adding simple movement, like rocking a bit in all directions or expressing an exhale as a sigh, a yawn or a hum.

Note: If you find your personal resources are insufficient, find a guide to work with one-on-one to discover your own individual path for increasing the “window of capacity”. Above all, be gentle with yourself – take your time – cultivate your garden – and enjoy your breath!

References

Epstein, M. (2013) Thoughts without a Thinker: Psychotherapy from a Buddhist Perspective. New York: Basic Books. https://www.amazon.com/Thoughts-Without-Thinker-Psychotherapy-Perspective/dp/0465050948

Levine, S. (1991). Guided Meditations, Explorations and Healings. New York: Anchor. https://www.amazon.com/Guided-Meditations-Explorations-Healings-Stephen/dp/0385417373

Luthe, W. (1969). Autogenic Therapy Volume 1 Autogenic Methods. New York: Grune and Stratton. https://www.amazon.com/Autogenic-Therapy-1-Methods/dp/B0013457B4/

Luthe, W. (1979). About the Methods of Autogenic Therapy. In: Peper, E., Ancoli, S., Quinn, M. (eds). Mind/Body Integration. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4613-2898-8_12

Luthe, W. & de Rivera, L. (2015). Wolfgang Luthe Introductory workshop: Introduction to the Methods of Autogenic Training, Therapy and Psychotherapy (Autogenic Training & Psychotherapy). CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. https://www.amazon.com/WOLFGANG-LUTHE-INTRODUCTORY-WORKSHOP-Psychotherapy/dp/1506008038/

Quick Rescue Techniques When Stressed

Posted: February 4, 2024 Filed under: attention, behavior, biofeedback, Breathing/respiration, CBT, cognitive behavior therapy, education, emotions, Evolutionary perspective, Exercise/movement, health, mindfulness, Neck and shoulder discomfort, posture, relaxation, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: alarm reaction, anxiety, box breathing, Breathing, conditioning, defense reaction, health, huming, Parasympathetic response, rumination, safety, sniff inhale, somatic practices, stress, sympathetic arousal, tactical breathing, Toning, yoga 2 CommentsErik Peper, PhD, Yuval Oded, PhD, and Richard Harvey, PhD

Adapted from Peper, E., Oded, Y, & Harvey, R. (2024). Quick somatic rescue techniques when stressed. Biofeedback, 52(1).

“If a problem is fixable, if a situation is such that you can do something about it, then there is no need to worry. If it’s not fixable, then there is no help in worrying. There is no benefit in worrying whatsoever.” ― Dalai Lama XIV

To implement the Dalai Lama’s quote is challenging. When caught up in an argument, being angry, extremely frustrated, or totally stressed, it is easy to ruminate, worry. It is much more challenging to remember to stay calm. When remembering the message of the Dalai Lama’s quote, it may be possible to shift perspective about the situation although a mindful attitude may not stop ruminating thoughts. The body typically continues to reacti to the torrents of thoughts that may occur when rehashing rage over injustices, fear over physical or psychological threats, or profound grief and sadness over the loss of a family member. Some people become even more agitated and less rational as illustrated in the following examples.

I had an argument with my ex and I am still pissed off. Each time I think of him or anticipate seeing them, my whole body tightened. I cannot stomach seeing him and I already see the anger in his face and voice. My thoughts kept rehashing the conflict and I am getting more and more upset.

A car cut right in front of me to squeeze into my lane. I had to slam on my brakes. What an idiot! My heart rate was racing and I wanted to punch the driver.

When threatened, we respond quickly in our thoughts and body with a defense reaction that may negatively affect those around us as well as ourselves. What can we do to interrupt negative stress reactions?

Background

Many approaches exist that allow us to become calmer and less reactive. General categories include techniques of cognitive reappraisal (seeing the situation from the other person’s point of view and labeling your own feelings and emotions) and stress management techniques. Practices that are beneficial include mindfulness meditation, benign humor (versus gallows humor), listening to music, taking a time out while implementing a variety of self-soothing practices, or incorporating slow breathing (e.g., heart rate variability and/or box breathing) throughout the day.

No technique fits all as we respond differently to our stressful life circumstances. For example, some people during stress react with a “tend and befriend stress response” (Cohen & Lansing, 2021; Taylor et al., 2000). This response appears to be mostly mediated by the hormone oxytocin acting in ways that sooth or calm the nervous system as an analgesic. These neurophysiological mechanisms of the soothing with the calming analgesic effects of oxytocin have been characterized in detail by Xin, et al. (2017).

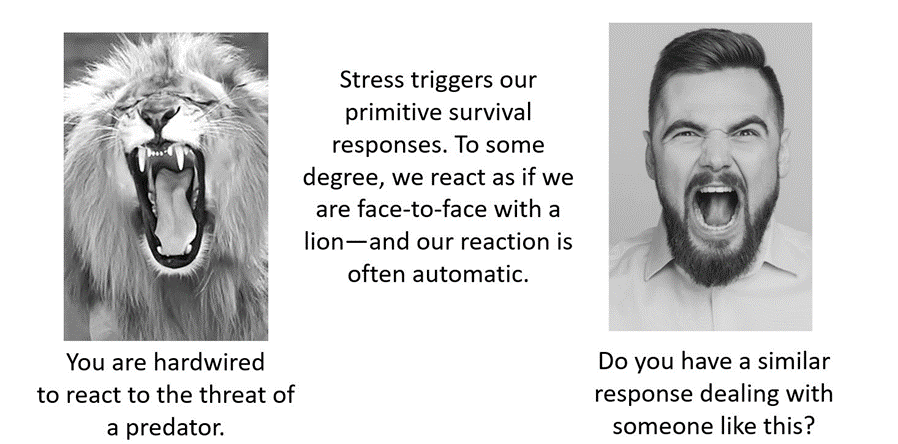

The most common response is a fight/flight/freeze stress response that is mediated by excitatory hormones such as adrenalin and inhibitory neurotransmitters such as gamma amino butyric acid (GABA). There is a long history of fight/flight/freeze stress response research, which is beyond the scope of this blog with major theories and terms such as interior milleau (Bernard, 1872); homeostasis and fight/flight (Cannon, 1929); general adaptation syndrome (Selye, 1951); polyvagal theory (Porges, 1995); and, allostatic load (McEwen, 1998). A simplified way to start a discussion about stress reactions begins with the fight/flight stress response. When stressed our defense reactions are triggered. Our sympathetic nervous system becomes activated our mind and body stereotypically responds as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. An intense confrontation tends to evoke a stress response (reproduced from Peper et al., 2020).

The flight/fight response triggers a cascade of stress hormones or neurotransmitters (e.g., hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal cascade) and produces body changes such as the heart pounding, quicker breathing, an increase in muscle tension and sweating. Our body mobilizes itself to protect itself from danger. Our focus is on immediate survival and not what will occur in the future (Porges, 2021; Sapolsky, 2004). It is as if we are facing an angry lion—a life-threatening situation—and we feel threatened and unsafe.

Rather than sitting still, a quick effective strategy is to interrupt this fight/flight response process by completing the alarm reaction such as by moving our muscles (e.g., simulating a fight or flight behavior) before continuing with slower breathing or other self-soothing strategies. Many people have experienced their body tension is reduced and they feel calmer when they do vigorous exercise after being upset, frustrated or angry. Similarly, athletes often have reported that they experience reduced frequency and/or intensity of negative thoughts after an exhausting workout (Thayer, 2003; Liao et al., 2015; Basso & Suzuki, 2017).

Becoming aware of the escalating cascades of physical, behavioral and psychological responses to a stressor is the first step in interrupting the escalating process. After becoming aware, reduce the body’s arousal and change the though patterns using any of the techniques described in this blog. The self-regulation skills presented in this blog are ideally over-learned and automated so that these skills can be rapidly implemented to shift from being stressed to being calm. Examples of skills that can shift from sympathetic neervous system overarousal to parasympathetic nervous system calm include techniques of autogenic traing (Schulz & Luthe, 1959), the quieting reflex developed by Charles Stroebel in 1985 or more recently rescue breathing developed by Richard Gevirtz (Stroebel, 1985; Gevirtz, 2014; Peper, Gibney & Holt, 2002; Peper & Gibney, 2003).

Concepts underlying the rescue techniques

- Psychophysiological principle: “Every change in the physiological state is accompanied by an appropriate change in the mental-emotional state, conscious or unconscious, and conversely, every change in the mental-emotional state, conscious or unconscious, is accompanied by an appropriate change in the physiological state” (Green et al. 1970, p. 3).

- Posture evokes memories and feelings associated with the position. When the body posture is erect and tall while looking slightly up. It is easier to evoke empowering, positive thoughts and feelings. When looking down it is easier to evoke hopeless, helpless and powerless thoughts and feelings (Peper et al., 2017).

- Healing occurs more easily when relaxed and feeling safe. Feeling safe and nurtured enhances the parasympathetic state and reduces the sympathetic state. Use memory recall to evoke those experiences when you felt safe (Peper, 2021).

- Interrupting thoughts is easier with somatic movement than by redirecting attention and thinking of something else without somatic movement.

- Focus on what you want to do not want to do. Attempting to stop thinking or ruminating about something tends to keeps it present (e.g., do not think of pink elephants. What color is the elephant? When you answer, “not pink,” you are still thinking pink). A general concept is to direct your attention (or have others guide you) to something else (Hilt & Pollak, 2012; Oded, 2018; Seo, 2023).

- Skill mastery takes practice and role rehearsal (Lally et al., 2010; Peper & Wilson, 2021).

- Use classical conditioning concepts to facilitate shifting states. Practice the skills and associate them with an aroma, memory, sounds or touch cues. Then when you the situation occurs, use these classical conditioned cues to facilitate the regeneration response (Peper & Wilson, 2021).

Rescue techniques

Coping When Highly Stressed and Agitated

- Complete the alarm/defense reaction with physical activity (Be careful when you do these physical exercises if you have back, hip, knee, or ankle problems).

- Acknowledge you have reacted and have chosen to interrupt your automatic response.

- Check whether the situation is actually a threat. If yes, then do anything to get out of immediate danger (yell, scream, fight, run away, or dial 911).

- If there is no actual physical threat, then leave the situation and perform vigorous physical activity to complete your alarm reaction, such as going for a run or walking quickly up and down stairs. As you do the exercise, push yourself so that the muscles in your thighs are aching, which focusses your attention on the sensations in your thighs. In our experience, an intensive run for 20 minutes quiets the brain while it often takes 40 minutes when walking somewhat quickly.

- After recovering from the exhaustive exercise, explore new options to resolve the conflict.

- Complete the alarm/defense reaction and evoke calmness with the S.O.S™ technique (Oded, 2023)

- Acknowledge you have reacted and have chosen to interrupt your automatic response.

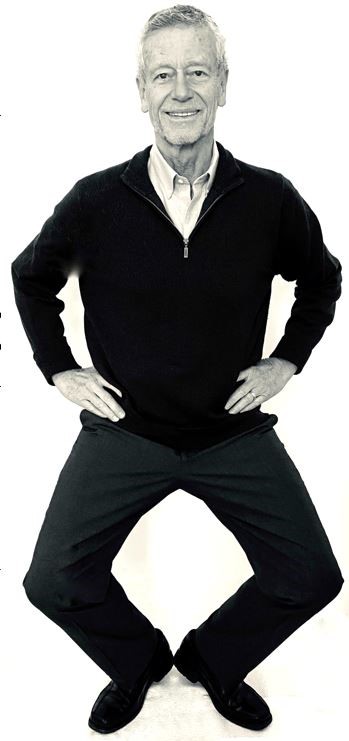

- Squat against a wall (similar to the wall-sit many skiers practice). While tensing your arms and fists as shown in Figure 2, gaze upward because it is more difficult to engage in negative thinking while looking upwards. If you continue to ruminate, then scan the room for object of a certain color or feature to shift visual attention and be totally present on the visual object.

- Do this set of movements for 7 to 10 seconds or until you start shaking. Than stand up and relax hands and legs. While standing, bounce up and down loosely for 10 to 15 seconds as you become aware of the vibratory sensations in your arms and shoulders, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2.Defense position wall-sit to tighten muscles in the protective defense posture (Oded, 2023). Figure 3. Bouncing up and down to loosen muscles ((Oded, 2023).

- Acknowledge you have reacted and have chosen to interrupt your automatic response. Swing your arms back and forth for 20 seconds. Allow the arms to swing freely as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Swinging the arms to loosen the body and spine (Oded, 2023).

- Rest and ground. Lie on the floor and put your calves and feet on a chair seat so that the psoas muscle can relax, as illustrated in Figure 5. Allow yourself to be totally supported by the floor and chair. Be sure there is a small pillow under your head and put your hand on your abdomen so that you can focus on abdominal breathing.

Figure 5. Lying down to allow the psoas muscle to relax and feel grounded (Oded, 2023).

- While lying down, imagine a safe place or memory and make it as real as possible. It is often helpful to listen to a guided imagery or music. The experience can be enhanced if cues are present that are associated with the safe place, such as pictures, sounds, or smells. Continue to breathe effortlessly at about six breaths per minute. If your attention wanders, bring it back to the memory or to the breathing. Allow yourself to rest for 10 minutes.

In most cases, thoughts stop and the body’s parasympathetic activity becomes dominant as the person feels safe and calm. Usually, the hands warm and the blood volume pulse amplitude increases as an indicator of feeling safe, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Blood volume pulse increases as the person is relaxing, feels safe and calm.

Coping When You Can’t Get Away (adapted from Peper, Harvey & Faass, 2020)

In many cases, it is difficult or embarrassing to remove yourself from the situation when you are stressed out such as at work, in a business meeting or social gathering.

- Become aware that you have reacted.

- Excuse yourself for a moment and go to a private space, such as a restroom. Going to the bathroom is one of the only acceptable social behaviors to leave a meeting for a short time.

- In the bathroom stall, do the 5-minute Nyingma exercise, which was taught by Tarthang Tulku Rinpoche in the tradition of Tibetan Buddhism, as a strategy for thought stopping (see Figure 7). Stand on your toes with your heels touching each other. Lift your heels off the floor while bending your knees. Place your hands at your sides and look upward. Breathe slowly and deeply (e.g., belly breathing at six breaths a minute) and imagine the air circulating through your legs and arms. Do this slow breathing and visualization next to a wall so you can steady yourself if necessary to keep balance. Stay in this position for 5 minutes or longer. Do not straighten your legs—keep squatting despite the discomfort. In a very short time, your attention is captured by the burning sensation in your thighs. Continue. After 5 minutes, stop and shake your arms and legs.

Figure 7. Stressor squat Nyingma exercise (reproduced from Peper et al., 2020).

- Follow this practice with slow abdominal breathing to enhance the parasympathetic response. Be sure that the abdomen expands as the inhalation occurs. Breathe in and out through the nose at about six breaths per minute.

- Once you feel centered and peaceful, return to the room.

- After this exercise, your racing thoughts most likely will have stopped and you will be able to continue your day with greater calm.

What to do When Ruminating, Agitated, Anxious or Depressed

(adapted from Peper, Harvey, & Hamiel, 2019).

- Shift your position by sitting or standing erect in a power position with the back of the head reaching upward to the ceiling while slightly gazing upward. Then sniff quickly through nose, hold and again sniff quickly then very slowly exhale. Be sure as you exhale your abdomen constricts. Then sniff again as your abdomen gets bigger, hold, and sniff one more time letting the abdomen get even bigger. Then, very slow, exhale through the nose to the internal count of six (adapted from Balban et al., 2023). When you sniff or gasp, your racing thoughts will stop (Peper et al., 2016).

- Continue with box breathing (sometimes described as tactical breathing or battle breathing) by exhaling slowly through your nose for 4 seconds, holding your breath for 4 seconds, inhaling slowly for 4 seconds through your nose, holding your breath for 4 seconds and then repeating this cycle of breathing for a few minutes (Röttger et al., 2021; Balban et al., 2023). Focusing your attention on performing the box breathing makes it almost impossible to think of anything else. After a few minutes, follow this with slow effortless diaphragmatic breathing at about six breaths per minute. While exhaling slowly through your nose, look up and when you inhale imagine the air coming from above you. Then as you exhale, imagine and feel the air flowing down and through your arms and legs and out the hands and feet.

- While gazing upward, elicit a positive memory or a time when you felt safe, powerful, strong and/or grounded. Make the positive memory as real as possible.

- Implement cognitive strategies such as reframing the issue, sending goodwill to the person, seeing the problem from the other person’s point of view, and ask is this problem worth dying over (Peper, Harvey, & Hamiel, 2019).

What to Do When Thoughts Keep Interrupting

Practice humming or toning. When you are humming or toning, your focus is on making the sound and the thoughts tend to stop. Generally, breathing will slow down to about six breaths per minute (Peper, Pollack et al., 2019). Explore the following:

- Box breathing (Röttger et al., 2021; Balban et al., 2023)

- Humming also known as bee breath (Bhramari Pranayama) (Abishek et al., 2019; Yoga, 2023) – Allow the tongue to rest against the upper palate, sit tall and erect so that the back of the head is reaching upward to the ceiling, and inhale through your nose as the abdomen expands. Then begin humming while the air flows out through your nose, feel the vibration in the nose, face and throat. Let humming last for about 7 seconds and then allow the air to blow in through the nose and then hum again. Continue for about 5 minutes.

- Toning – Inhale through your nose and then vocalize a single sound such as Om. As you vocalize the lower sound, feel the vibration in your throat, chest and even going down to the abdomen. Let each toning exhalation last for about 6 to 7 seconds and then inhale through your nose. Continue for about 5 minutes (Peper, al., 2019).

Many people report that after practice these skills, they become aware that they are reacting and are able to reduce their automatic reaction. As a result, they experience a significant decrease in their stress levels, fewer symptoms such as neck and holder tension and high blood pressure, and they feel an increase in tranquility and the ability to communicate effectively.

Practicing these skills does not resolve the conflicts; they allow you to stop reacting automatically. This process allows you a time out and may give you the ability to be calmer, which allows you to think more clearly. When calmer, problem solving is usually more successful. As phrased in a popular meme, “You cannot see your reflection in boiling water. Similarly, you cannot see the truth in a state of anger. When the waters calm, clarity comes” (author unknown).

Boiling water (photo modified from: https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=388991500314839&set=a.377199901493999)

Below are additional resources that describe the practices. Please share these resources with friends, family and co-workers.

Stressor squat instructions

Toning instructions

Diaphragmatic breathing instructions

Reduce stress with posture and breathing

Conditioning

References

Abishek, K., Bakshi, S. S., & Bhavanani, A. B. (2019). The efficacy of yogic breathing exercise bhramari pranayama in relieving symptoms of chronic rhinosinusitis. International Journal of Yoga, 12(2), 120–123. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijoy.IJOY_32_18

Balban, M. Y., Neri, E., Kogon, M. M., Weed, L., Nouriani, B., Jo, B., Holl, G., Zeitzer, J. M., Spiegel, D., Huberman, A. D. (2023). Brief structured respiration practices enhance mood and reduce physiological arousal. Cell Reports Medicine, 4(1), 10089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100895

Basso, J. C. & Suzuki, W. A. (2017). The effects of acute exercise on mood, cognition, neurophysiology, and neurochemical pathways: A review. Brain Plast, 2(2), 127–152. https://doi.org/10.3233/BPL-160040

Bernard, C. (1872). De la physiologie générale. Paris: Hachette livre. https://www.amazon.ca/PHYSIOLOGIE-GENERALE-BERNARD-C/dp/2012178596

Cannon, W. B. (1929). Organization for Physiological Homeostasis. Physiological Reviews, 9, 399–431. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.1929.9.3.399

Cohen, L. & Lansing, A. H. (2021). The tend and befriend theory of stress: Understanding the biological, evolutionary, and psychosocial aspects of the female stress response. In: Hazlett-Stevens, H. (eds), Biopsychosocial Factors of Stress, and Mindfulness for Stress Reduction. pp. 67–81, Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81245-4_3

Gevirtz, R. (2014). HRV Training and its Importance – Richard Gevirtz, Ph.D., Pioneer in HRV Research & Training. Thought Technology. Accessed December 29, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9nwFUKuJSE0

Green, E. E., Green, A. M., & Walters, E. D. (1970). Voluntary control of internal states: Psychological and physiological. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 2, 1–26. https://atpweb.org/jtparchive/trps-02-70-01-001.pdf

Hilt, L. M., & Pollak, S. D. (2012). Getting out of rumination: comparison of three brief interventions in a sample of youth. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40(7), 1157–1165.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-012-9638-3

Lally, P., VanJaarsveld, C. H., Potts, H. W., & Wardle, J. (2010). How habits are formed: Modelling habit formation the real world. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 998–1009. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.674

Liao, Y., Shonkoff, E. T., & Dunton, G. F. (2015). The acute relationships between affect, physical feeling states, and physical activity in daily life: A review of current evidence. Frontiers in Psychology. 6, 1975. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01975

McEwen, B. S. (1998). Stress, adaptation, and disease: Allostasis and allostatic load. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 840(1), 33–44.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09546.x

Oded, Y. (2018). Integrating mindfulness and biofeedback in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Biofeedback, 46(2), 37-47. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-46.02.03

Oded, Y. (2023). Personal communication. S.O.S 1™ technique is part of the Sense Of Safety™ method. www.senseofsafety.co

Peper, E. (2021). Relive memory to create healing imagery. Somatics, XVIII(4), 32–35.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/369114535_Relive_memory_to_create_healing_imagery

Peper, E., Gibney, K.H. & Holt. C. (2002). Make Health Happen: Training Yourself to Create Wellness. Dubuque, IA: Kendall-Hunt. https://he.kendallhunt.com/product/make-health-happen-training-yourself-create-wellness

Peper, E., & Gibney, K.H. (2003). A teaching strategy for successful hand warming. Somatics. XIV(1), 26–30. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/376954376_A_teaching_strategy_for_successful_hand_warming

Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Faass, N. (2020). TechStress: How Technology is Hijacking Our Lives, Strategies for Coping, and Pragmatic Ergonomics. North Atlantic Books. https://www.amazon.com/Beyond-Ergonomics-Prevent-Fatigue-Burnout/dp/158394768X

Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Hamiel, D. (2019). Transforming thoughts with postural awareness to increase therapeutic and teaching efficacy. NeuroRegulation, 6(3),153–160. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.6.3.153

Peper, E., Lee, S., Harvey, R., & Lin, I-M. (2016). Breathing and math performance: Implication for performance and neurotherapy. NeuroRegulation, 3(4), 142–149. http://dx.doi.org/10.15540/nr.3.4.142

Peper, E., Lin, I-M, Harvey, R., & Perez, J. (2017). How posture affects memory recall and mood. Biofeedback, 45(2), 36–41. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-45.2.01

Peper, E., Pollack, W., Harvey, R., Yoshino, A., Daubenmier, J. & Anziani, M. (2019). Which quiets the mind more quickly and increases HRV: Toning or mindfulness? NeuroRegulation, 6(3), 128–133. https://www.neuroregulation.org/article/view/19345/13263

Peper, E. & Wilson, V. (2021). Optimize the learning state: Techniques and habits. Biofeedback, 9(2), 46–49. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-49-2-04

Porges, S. W. (1995). Orienting in a defensive world: Mammalian modifications of our evolutionary heritage. A polyvagal theory. Psychophysiology, 32(4), 301–318. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.1995.tb01213.x

Porges, S.W. (2021) Cardiac vagal tone: a neurophysiological mechanism that evolved in mammals to dampen threat reactions and promote sociality. World Psychiatry, 20(2),296-298. Porges SW. Cardiac vagal tone: a neurophysiological mechanism that evolved in mammals to dampen threat reactions and promote sociality. World Psychiatry. 2021 Jun;20(2):296-298. https://doi.org10.1002/wps.20871

Röttger, S., Theobald, D. A., Abendroth, J., & Jacobsen, T. (2021). The effectiveness of combat tactical breathing as compared with prolonged exhalation. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 46, 19–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-020-09485-w

Sapolsky, R. (2004). Why zebras don’t get ulcers (3rd ed.). New York:Holt. https://www.amazon.com/Why-Zebras-Dont-Ulcers-Third/dp/0805073698/

Schultz, J. H., & Luthe, W. (1959). Autogenic training: A psychophysiologic approach to psychotherapy. Grune & Stratton. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Autogenic_Training/y8SwQgAACAAJ?hl=en

Selye, H. (1951). The general-adaptation-syndrome. Annual Review of Medicine, 2(1), 327–342. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.me.02.020151.001551

Seo, H. (2023). How to stop ruminating. The New York Times. Accessed January 3, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/01/well/mind/stop-rumination-worry.html

Stroebel, C. F. (1985). QR: The Quieting Reflex. Berkley. https://www.amazon.com/Qr-quieting-reflex-Charles-Stroebel/dp/0425085066

Taylor, S. E., Klein, L. C., Lewis, B. P., Gruenewald, T. L., Gurung, R. A. R., & Updegraff, J. A. (2000). Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: Tend-and-befriend, not fight-or-flight. Psychological Review, 107(3), 411–429. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.107.3.411

Thayer, R. E. (2003). Calm energy: How people regulate mood with food and exercise. Oxford University Press. https://www.amazon.com/Calm-Energy-People-Regulate-Exercise/dp/0195163397

Xin, Q., Bai, B., & Liu, W. (2017). The analgesic effects of oxytocin in the peripheral and central nervous system. Neurochemistry International, 103, 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuint.2016.12.021

Yoga, N. (2023). This simple breath practice is scientifically proven to calm your mind. The nomadic yogi. Accessed December 31, 2023. https://www.leahsugerman.com/blog/bhramari-pranayama-humming-bee-breath#

Compassion supports healing: Case report how a “bad eye” became an “amazing eye”*

Posted: April 11, 2023 Filed under: behavior, cognitive behavior therapy, healing, health, mindfulness, Pain/discomfort, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized, vision | Tags: compassion, self-image 2 CommentsErik Peper, PhD and Dana Yirmiyahu

“I completely changed my perception of having a bad eye, to having an amazing eye. After two months, my eye is totally normal and healthy”

When experiencing chronic discomfort or reduced function, we commonly describe that part of our body that causes problems as broken or bad. Sometimes we even wish that it did not exist. In other cases, especially if there is pain or disfigurement, the person may attempt to dissociate from that body part. The language the person uses creates a graphic imagery that may impact the healing process; since, language can also be seen as a self-hypnotic suggestion.

The negative labeling, plus being disgusted or frustrated with that part of the body that is the cause of discomfort, often increases stress, tension and sympathetic activity. This reduces our self-healing potential. In many cases, the language is both the description and the prognosis-a self-fulfilling prophecy. If the description is negative and judgmental, it may interfere with the healing/treatment process. The negative language may activate the nocebo process that inhibits regeneration. On the other hand, positive affirming language may implicitly activate the placebo process that enhances healing.

By reframing the experience as positive and appreciating what the problem area of the body had done for you in the past as well as incorporating a healing compassionate process, healing is supported. Our limiting beliefs limit our possibilities. See the TED talk, A broken body isn’t a broken person, by Janine Shepherd (2014) who, after a horrendous accident and being paralyzed, became an acrobatic pilot instructor. Another example of a remarkable recovery is that of Madhu Anziani. After falling from a second floor window, he was a quadriplegic and used Reiki, toning, self-compassion and hope to improve his health. He reframed the problem as an opportunity for growth. He can now walk, talk and play the most remarkable music (Anziani and Peper, 2021).

When a person can focus on what they can do instead of focusing on what they cannot do or on their suffering, pain may be reduced. For example, Jill Cosby describes undergoing two surgeries to replace her shattered L3 with a metal “cage” and fused this cage to the L4 and L2 vertebrae with bars. She used imagery to eliminate the pains in her back and stopped her pain medications (Peper et al., 2022). The healing process is similar to how children develop, growth, and learn–a process that is promoted through playfulness and support with an openness to possibilities.

Healing only goes forwards in time

After an injury, most people want to be the same as they were before the injury, and they keep comparing themselves to how they were. The person can never be what they were in the past, butthey can be different and even better.. Time flows only in a forward direction, and the person already has been changed by the experience. Instead, the person explores ways to accept where they are, appreciate how much the problem area has done for them in the past, and continue to work to improve. This is a dynamic process in which the person appreciates the very small positive changes that are occurring without setting limits on how much change can occur.

A useful tool while working with clients is to explore ways by which they can genuinely transform their negative beliefs and self-talk about the problem to appreciation and growth. This process is illustrated in the following report about the rapid healing of a 15-year problem with an eye that had become smaller following severe corneal abrasion.

Case report

On January 18th, 2023, I attended a workshop/ lecture by Professor Erik Peper.

During the break, I spoke to him and expressed my concern regarding my right eye. 15 years ago, the cornea of my eye was accidently scratched by my 3-year-old daughter. The eye suffered a trauma and was treated at the hospital. In addition, I had a patch over my eye for 3 weeks and suffered extrusion pain during the first 2 weeks. A scar remained on my eye, and doctors were not able to say if it would be permanent or whether the eye would heal itself eventually. An invasive operation was also suggested, which I refused. The trauma affected my eyesight for a few months, but after a year, the scar was gone and physically no permanent damage has remained.

Although it was certainly determined that my eye had healed completely, it didn’t feel that way at all. I always considered it ‘my bad eye’ and suffered irritation and pain every time I experienced tiredness, anxiety, or any other emotional discomfort. My eye was the first and only organ to reflect pain/itchiness/irritation. Over time, my eye ‘shrank’ as well. It became visibly smaller and it felt tense at all times.

For 15 years, that was my reality! I coped with it and haven’t thought of it much, until January 18, when I attended the workshop.

Professor Peper asked me to the front of the stage when we returned from break and conducted an exercise with me, where I used my imagination and words to comfort my eye and embrace it rather than call it ‘the defective/bad eye’. He pointed out that if you only describe your children as bad or evil, how can you expect them to grow? Then, he explored with me a few exercises such as evoking self-healing imagery. The self-healing imagery did not totally resonate; however, I felt I just needed to hug my eye. I thanked my eye for its being and stroked it gently in my mind. On stage and during the rest of the lecture I felt a sense of comfort. I felt if the muscles around my eye had finally loosened–a feeling I haven’t experienced for years. I continued to follow the instructions I got at the workshop for a couple of days, but unfortunately, I did not persist, and the negative sensations returned.

On a follow-up zoom meeting 10 days after the lecture with Prof. Peper, I received additional tools to practice ‘eye physiotherapy’ as well as mindfulness regarding the eye. This practice consisted of closing my eyes and covering the non-problem eye and then as I exhaled gently and softly opening my eyes, opening them more and more while looking all around. I completely changed my perception of having a bad eye, to having ‘an amazing eye’. At first talking to it didn’t come naturally to me but as I persisted it became easier and easier. I did it in the car, before going to sleep and when waking up in the morning. In addition, I practiced the exercises I got over zoom, where I covered my left eye (the undamaged one) and had my right eye look up and down to both sides.

It has been about three months since this zoom meeting and I am awed by the results. My eye has opened more, and no longer feels shrunk and small, I rarely feel negative sensations in it and when I do, I immediately know how to handle it.

I can say that attending this workshop has definitely been a life-changing event for my amazing right eye and for me.

Why did the healing occur?

The “bad eye” symptoms were most likely caused by “learned disuse”; namely, the chronic eye tension was the result of the protective response to reduce the discomfort after the injury to the cornea (Uswatte & Taub, 2005). After the injury and medical treatment, she would have unknowingly tensed her muscles around the eye to protect it. This process occurs automatically without conscious awareness. This protective response became her “new normal” and once her eye had healed, the bracing continued. The bracing pattern was amplified by the ongoing self-labeling of having a “bad eye.” By accepting the eye as it was, giving it compassionate caring and support, and following up with simple eye movement exercises to allow the eye to rediscover and experience the complete range of motion, the symptoms disappeared.

What can we take home from this case example?

Listen to the language a client uses to describe their problem. Does the language implicitly limit recovery, growth and hope (e.g., I will always have the problem)? Does the language inhibit caring and compassion for the problem area (e.g., I’m frustrated, angry, disgusted)? If that is the case, explore ways to reframe the language and emotional tone. A useful strategy is to incorporate self-healing imagery: the person first inspects the problem area, next imagines how it would look when it is healthy, and finally creates self-healing imagery that transforms what was observed to become well and whole. Then, each moment the client’s attention is drawn to the problem, he or she evokes the self-healing imagery (Peper, Gibney, & Holt, 2002). In many cases, combining this imagery with slower breathing to reduce stress promotes healing.

References

Anziani, M. & Peper, E. (2021). Healing from paralysis-Music (toning) to activate health. the peper perspective-ideas on illness, health and well-being from Erik Peper. Accessed March 22, 2023. https://peperperspective.com/2021/11/22/healing-from-paralysis-music-toning-to-activate-health/

Mullins, A. (2009). The opportunity of adversity. TEDMED. Accessed March 22, 2023. https://www.ted.com/talks/aimee_mullins_the_opportunity_of_adversity?language=en

Peper, E. Cosby, J. & Amendras, M. (2022). Healing chronic back pain. NeuroRegulation, 9(3), 165-172. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.9.3.164

Peper, E., Gibney, H. K. & Holt, C. (2002). Make Health Happen. Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall-Hunt. pp. 193-236. https://he.kendallhunt.com/make-health-happen

Shepherd, J. (2014). A broken body isn’t a broken person. TEDxKC. Accessed March 20, 2023 https://www.ted.com/talks/janine_shepherd_a_broken_body_isn_t_a_broken_person?language=en

Uswatte, G. & Taub, E. (2005). Implications of the Learned Nonuse Formulation for Measuring Rehabilitation Outcomes: Lessons From Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy. Rehabilitation Psychology, 50(1), 34-42. https://doi.org/10.1037/0090-5550.50.1.34

*I thank Cathy Holt, MPH, for her supportive feedback.

Breathing: Informative YouTube videos and blogs

Posted: March 20, 2023 Filed under: behavior, Breathing/respiration, health, mindfulness, Pain/discomfort, relaxation, self-healing | Tags: anxiety, box breathing, carbon dioxide, exhaling, hickups 3 Comments

Breathing is a voluntary and involuntary process and affects our body, emotions, mind and performance. The focus of breathing is to bring oxygen into the body and eliminate carbon dioxide. This is the basic physiological process that underlies the concepts described in the videos; however, it does not included the concept as breathing as a pump to optimize abdominal venous and lymph circulation. The pumping action may reduce abdominal discomfort such as irritable bowel disease, acid reflux and pelvic floor discomfort. Effortless whole body breathing also supports pelvic floor muscle tone balance and spinal column dynamics. Effortless diaphragmatic breathing can only occur if the abdomen is able to expand and constrict in 360 degrees and not constricted by tight clothing around the waist (designer’s jean syndrome), self-image (holding the abdomen in to look slimmer), or learned disuse of abdominal movement (breathing shallowly and in the chest to avoid movement at the incisionsafter abdominal surgery).

The outstanding videos discuss the psychophysiology, mechanics, chemistry of respiration as well as useful practices practices to enhance health..

- How to Breathe Correctly for Optimal Health, Mood, Learning & Performance | Huberman Lab Podcast (Skip the advertisements embedded in this video)

- Dr. Jack Feldman: Breathing for Mental & Physical Health & Performance | Huberman Lab Podcast #54 (Skip the advertisements embedded in this video)

The videos provide additional approaches to improve breathing and health

- 5 Ways to Improve your Breathing with James Nestor

- Patrick McKeown-Why we breathe: How to improve your sleep, concentration, focus & performance

The blogs that explores how diaphragmatic breathing may reduce symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome, acid reflux, and pelvic floor pain.

- Healing irritable bowel syndrome with diaphragmatic breathing

- Breathing to reduce acid reflux and dysmenorrhea

- Enjoy sex: Breath away the pain

- Resolving pelvic floor pain-a casae report

Below are the descriptions of the youtube videos.

How to Breathe Correctly for Optimal Health, Mood, Learning & Performance | Huberman Lab Podcast

In this episode, I explain the biology of breathing (respiration), how it delivers oxygen and carbon dioxide to the cells and tissues of the body and how is best to breathe—nose versus mouth, fast versus slow, deliberately versus reflexively, etc., depending on your health and performance needs. I discuss the positive benefits of breathing properly for mood, to reduce psychological and physiological stress, to halt sleep apnea, and improve facial aesthetics and immune system function. I also compare what is known about the effects and effectiveness of different breathing techniques, including physiological sighs, box breathing and cyclic hyperventilation, “Wim Hof Method,” Prānāyāma yogic breathing and more. I also describe how to breath to optimize learning, memory and reaction time and I explain breathing at high altitudes, why “overbreathing” is bad, and how to breathe specifically to relieve cramps and hiccups. Breathwork practices are zero-cost and require minimal time yet provide a unique and powerful avenue to improve overall quality of life that is grounded in clear physiology. Anyone interesting in improving their mental and physical health or performance in any endeavor ought to benefit from the information and tools in this episode.

Dr. Jack Feldman: Breathing for Mental & Physical Health & Performance | Huberman Lab Podcast #54

This episode my guest is Dr. Jack Feldman, Distinguished Professor of Neurobiology at University of California, Los Angeles and a pioneering world expert in the science of respiration (breathing). We discuss how and why humans breathe the way we do, the function of the diaphragm and how it serves to increase oxygenation of the brain and body. We discuss how breathing influences mental state, fear, memory, reaction time, and more. And we discuss specific breathing protocols such as box-breathing, cyclic hyperventilation (similar to Wim Hof breathing), nasal versus mouth breathing, unilateral breathing, and how these each effect the brain and body. We discuss physiological sighs, peptides expressed by specific neurons controlling breathing, and magnesium compounds that can improve cognitive ability and how they work. This conversation serves as a sort of “Master Class” on the science of breathing and breathing related tools for health and performance.

5 Ways To Improve Your Breathing with James Nestor

James Nestor believes we’re all breathing wrong. Here he breaks down 5 ways to transform your breathing, from increasing your lung capacity to stopping breathing through your mouth. There is nothing more essential to our health and wellbeing than breathing: take air in, let it out, repeat 25,000 times a day. Yet, as a species, humans have lost the ability to breathe correctly, with grave consequences. In Breath, journalist James Nestor travels the world to discover the hidden science behind ancient breathing practices to figure out what went wrong and how to fix it. Modern research is showing us that making even slight adjustments to the way we inhale and exhale can: – jump-start athletic performance – rejuvenate internal organs – halt snoring, allergies, asthma and autoimmune disease, and even straighten scoliotic spines None of this should be possible, and yet it is. Drawing on thousands of years of ancient wisdom and cutting-edge studies in pulmonology, psychology, biochemistry and human physiology, Breath turns the conventional wisdom of what we thought we knew about our most basic biological function on its head. You will never breathe the same again.

Patrick McKeown – Why We Breathe: How to Improve Your Sleep, Concentration, Focus & Performance

Watch Oxygen Advantage founder and world-renowned breathing expert Patrick McKeown speak to an influential group of health professionals at the recent Health Optimisation Summit in London. Patrick was presenting his very well-received topic: ‘Why We Breathe: How to Improve Your Sleep, Concentration, Focus & Performance’. The aim of the event was to “unite the health, wellness and science disciplines”, and in doing so, it brought together thousands of industry professionals and members of the public. Patrick would like to take this opportunity to thank the organisers of The Health Optimisation Summit for an excellent event and for giving him the opportunity to speak among such luminaries of the health and wellbeing world and on a subject about which he is very passionate.

Breathing is more than gas exchange

Effortless diaphragmatic breathing is optimized when the abdomen is able to expand and constrict in 360 degrees like and not constricted by tight clothing (designer’s jean syndrome induced by the constriction of the waist), self-image (holding the abdomen in to look slimmer), or learned disuse of abdominal movement (breathing shallowly and in the chest to avoid movement at the incisions site after abdominal surgery).

Bring joy through kindness

Posted: December 31, 2022 Filed under: behavior, healing, meditation, mindfulness | Tags: generousity, kindness Leave a commentAs the New Year begins, bring support through simple acts of kindness. As we share generously, our own well-being improves. I wish you health, happiness and peace for the New Year. Enjoy the two videos on simple acts of kindness.

Biofeedback, posture and breath: Tools for health

Posted: December 1, 2022 Filed under: ADHD, behavior, biofeedback, Breathing/respiration, CBT, cognitive behavior therapy, computer, digital devices, education, emotions, ergonomics, Evolutionary perspective, Exercise/movement, healing, health, laptops, mindfulness, Neck and shoulder discomfort, Pain/discomfort, posture, relaxation, screen fatigue, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized, vision, zoom fatigue 2 CommentsTwo recent presentations that that provide concepts and pragmatic skills to improve health and well being.

How changing your breathing and posture can change your life.

In-depth podcast in which Dr. Abby Metcalf, producer of Relationships made easy, interviews Dr. Erik Peper. He discusses how changing your posture and how you breathe may result in major improvement with issues such as anxiety, depression, ADHD, chronic pain, and even insomnia! In the presentation he explain how this works and shares practical tools to make the changes you want in your life.

How to cope with TechStress

A wide ranging discussing between Dr. Russel Jaffe and Dr Erik that explores the power of biofeedback, self-healing strategies and how to cope with tech-stress.

These concepts are also explored in the book, TechStress-How Technology is Hijacking our Lives, Strategies for Coping and Pragmatic Ergonomics. You may find this book useful as we spend so much time working online. The book describes the impacts personal technology on our physical and emotional well-being. More importantly, “Tech Stress” provides all of the basic tools to be able not only to survive in this new world but also thrive in it.

Additiona resources:

Gonzalez, D. (2022). Ways to improve your posture at home.

Meditation Myths and Tips for Practice

Posted: May 19, 2022 Filed under: behavior, Breathing/respiration, cognitive behavior therapy, emotions, healing, health, meditation, mindfulness, self-healing | Tags: Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, mindfulness-based stress reduction, TM, transcendental meditation Leave a commentMindfulness-based strategies are drawn from ancient Buddhist practices and have found acceptance as one of the major behavioral medicine techniques of today (Hilton et al, 2016; Khazan, 2013). Throughout this blog the term mindfulness will refer broadly to a mental state of paying total attention to the present moment, with a non-judgmental awareness of inner and outer experiences (Baer, Smith, & Allen, 2004; Kabat-Zinn, 1994). This approach is the common core for many stress management approaches (Peper, Harvey, & Lin, 2019).

Background

Transcendental meditation (TM), a form of concentrative meditation involving repetition of a sacred word or phrase known as a mantra, was a popular meditation technique introduced in the United States from India and participants reported improvement of mental and physical health (Wallace, 1970; Paul-Labrador et al, 2006; Rainforth et al, 2007; Hawkins, 2003). To make TM more acceptable for the western audience, Herbert Benson, MD, adapted and simplified the TM process and then labelled a core element, the ‘relaxation response’ (Benson, Beary, & Carol, 1974; Benson & Clipper, 1992). Instead of giving people a secret mantra and part of a spiritual tradition, he recommend using the word “one” as the mantra. Since that time numerous studies have demonstrated that when patients practice the relaxation response, many clinical symptoms were reduced.

In 1979, Jon Kabat-Zinn introduced a manual for a standardized Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center (Kabat-Zinn, 1994; Kabat-Zin, 2003). The eight-week program combined mindfulness as a form of insight meditation with mindful yogic movement exercises designed to focus awareness on body sensations, thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Mindfulness based programs have become a predominant approach used in behavioral medicine.

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) and mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) combine mindfulness meditation training with cognitive therapy and is a useful approach to reduce a variety of mental and physical conditions such as stress, anxiety, depression, addiction, disordered eating, chronic pain, sleep disturbances, and high blood pressure (Andersen et al., 2013; Carlson, Speca, Patel, & Goodey, 2003; Fjorback, Arendt, Ørnbøl, Fink, & Walach, 2011; Greeson, & Eisenlohr-Moul, 2014; Hoffman et al., 2012; Marchand, 2012; Baer, 2015; Demarzo et al, 2015; Khoury et al, 2013; Khoury et al, 2015; Teasdale, Segal, & Williams, 1995; Kabat-Zinn, 1994; Kabat-Zin, 2003; Zimmermann, Burrell, , & Jordan, 2018). Although in most cases, MBSR is helpful, in some cases meditation can evoke negative physical and/or psychological outcomes and inhibit prosocial behavior (Kreplin et al, 2018; Lindahl et al, 2017). Based on this encouraging research, many people are learning to meditate on their own using meditation apps. However, there are many questions that can arise for people new to meditation – such as what is meditation, how do I do it, what are the challenges, and how is it helpful? Some people also develop misconceptions about what meditation is and can become discouraged.

Watch the outstanding presentation by Professor Jennifer Daubenmier presented for the Holistic Health Lecture Series, in which she discusses meditation myths and pragmatic tips for practice.

References

Andersen, S. R., Würtzen, H., Steding-Jessen, M., Christensen, J., Andersen, K. K., Flyger, H., … & Dalton, S. O. (2013). Effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction on sleep quality: Results of a randomized trial among Danish breast cancer patients. Acta Oncologica, 52(2), 336-344. https://doi.org/10.3109/0284186X.2012.745948

Baer, R., Smith, G., & Allen, K. (2004). Assessment of mindfulness by self-report: The Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills. Assessment, 11, 191–206. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191104268029

Benson, H., Beary, J. F., & Carol, M. P. (1974).The Relaxation Response. Psychiatry, 37(1), 37-46. https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/upsy20

Benson, H. & Clipper, M.Z. (1992). The Relaxation Response. Wings Books.

Carlson, L. E., Speca, M., Patel, K. D., & Goodey, E. (2003). Mindfulness‐based stress reduction in relation to quality of life, mood, symptoms of stress, and immune parameters in breast and prostate cancer outpatients. Psychosomatic Medicine, 65(4), 571-581. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.psy.0000074003.35911.41

Demarzo, M. M., Montero-Marin, J., Cuijpers, P., Zabaleta-del-Olmo, E., Mahtani, K. R., Vellinga, A., Vicens, C., López-del-Hoyo, Y., & García-Campayo, J. (2015). The Efficacy of Mindfulness-Based Interventions in Primary Care: A Meta-Analytic Review. Annals of family medicine, 13(6), 573–582. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1863

Fjorback, L. O., Arendt, M., Ørnbøl, E., Fink, P., & Walach, H. (2011). Mindfulness‐Based Stress Reduction and Mindfulness‐Based Cognitive Therapy–A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 124(2), 102-119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01704.x

Greeson, J., & Eisenlohr-Moul, T. (2014). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for chronic pain. In R. A. Baer (Ed.), Mindfulness-Based Treatment Approaches: Clinician’s Guide to Evidence Base and Applications, 269-292. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. https://www.academia.edu/8092878/Mindfulness_Based_Stress_Reduction_for_Chronic_Pain

Hawkins, M. A. (2003). Effectiveness of the Transcendental Meditation program in criminal rehabilitation and substance abuse recovery, Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 36(1-4), 47-65. https://doi.org/10.1300/J076v36n01_03

Hilton, L., Hempel, S., Ewing, B. A., Apaydin, E., Xenakis, L., Newberry, S., …Maglione, M. A. (2016). Mindfulness meditation for chronic pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 51(2), 199-213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-016-9844-2

Hoffman, C. J., Ersser, S. J., Hopkinson, J. B., Nicholls, P. G., Harrington, J. E., & Thomas, P. W. (2012). Effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction in mood, breast-and endocrine-related quality of life, and well-being in stage 0 to III breast cancer: A randomized, controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 30(12), 1335-1342. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2010.34.0331

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1994). Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. New York: Hyperion.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). Constructivism in the Human Sciences, 8, 73–107. https://www.proquest.com/openview/fef538e3ed2210c1201ef2a946faed43/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=29080

Khazan, I. Z. (2013). The clinical handbook of biofeedback: A step-by-step guide for training and practice with mindfulness. John Wiley & Sons.

Khoury, B., Lecomte, T., Fortin, G., Masse, M., Therien, P., Bouchard, V., Chapleau, M., Paquin, K., & Hofmann, S. G. (2013). Mindfulness-based therapy: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(6), 763-771. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2013.05.005

Khoury, B., Sharma, M., Rush, S. E., & Fournier, C. (2015). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for healthy individuals: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 78(6), 519-528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.03.009

Kreplin, U., Farias, M., & Brazil, I. A. (2018). The limited prosocial effects of meditation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep, 8, 2403. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-20299-z

Lindahl, J. R., Fisher, N. E., Cooper, D. J., Rosen, R. K, & Britton, W. B. (2017) The varieties of contemplative experience: A mixed-methods study of meditation-related challenges in Western Buddhists. PLoSONE, 12(5): e0176239. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0176239

Marchand, W. R. (2012). Mindfulness-based stress reduction, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, and Zen meditation for depression, anxiety, pain, and psychological distress. Journal of Psychiatric Practice, 18(4), 233-252. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.pra.0000416014.53215.86

Paul-Labrador, M., Polk, D., Dwyer, J.H. et al. (2006). Effects of a randomized controlled trial of Transcendental Meditation on components of the metabolic syndrome in subjects with coronary heart disease. Archive of Internal Medicine, 166(11), 1218-1224. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.11.1218

Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Lin, I-M. (2019). Mindfulness training has themes common to other technique. Biofeedback. 47(3), 50-57. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-47.3.02

Rainforth, M.V., Schneider, R.H., Nidich, S.I., Gaylord-King, C., Salerno, J.W., & Anderson, J.W. (2007). Stress reduction programs in patients with elevated blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Current Hypertension Reports, 9(6), 520–528. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-007-0094-3

Teasdale, J. D., Segal, Z., & Williams, J. M. (1995). How does cognitive therapy prevent depressive relapse and why should attentional control (mindfulness) training help? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33, 25–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)e0011-7

Wallace, K.W. (1970). Physiological Effects of Transcendental Meditation. Science, 167 (3926), 1751-1754. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.167.3926.1

A breath of fresh air: Breathing and posture to optimize health

Posted: April 3, 2022 Filed under: behavior, Breathing/respiration, CBT, cognitive behavior therapy, emotions, ergonomics, Exercise/movement, health, mindfulness, Neck and shoulder discomfort, Pain/discomfort, posture, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: respiration 1 CommentMost people breathe 22,000 breaths per day. We tend to breathe more rapidly when stressed, anxious or in pain. While a slower diaphragmatic breathing supports recovery and regeneration. We usually become aware of our dysfunctional breathing when there are problems such as nasal congestion, allergies, asthma, emphysema, or breathlessness during exertion. Optimal breathing is much more than the absence of symptoms and is influenced by posture. Dysfunctional posture and breathing are cofactors in illness. We often do not realize that posture and breathing affect our thoughts and emotions and that our thoughts and emotions affect our posture and breathing. Watch the video, A breath of fresh air: Breathing and posture to optimize health, that was recorded for the 2022 Virtual Ergonomics Summit.

Reduce anxiety

Posted: March 23, 2022 Filed under: behavior, Breathing/respiration, CBT, cognitive behavior therapy, digital devices, education, emotions, health, mindfulness, posture, relaxation, self-healing, stress management | Tags: anxiety, concentration, insomnia, menstrual cramps, pain Leave a comment

The purpose of this blog is to describe how a university class that incorporated structured self-experience practices reduced self-reported anxiety symptoms (Peper, Harvey, Cuellar, & Membrila, 2022). This approach is different from a clinical treatment approach as it focused on empowerment and mastery learning (Peper, Miceli, & Harvey, 2016).

As a result of my practice, I felt my anxiety and my menstrual cramps decrease. — College senior

When I changed back to slower diaphragmatic breathin, I was more aware of my negative emotions and I was able to reduce the stress and anxiety I was feeling with the deep diaphragmatic breathing.– College junior

Background

More than half of college students now report anxiety (Coakley et al., 2021). In our recent survey during the first day of the spring semester class, 59% of the students reported feeling tired, dreading their day, being distracted, lacking mental clarity and had difficulty concentrating.

Before the COVID pandemic nearly one-third of students had or developed moderate or severe anxiety or depression while being at college (Adams et al., 2021. The pandemic accelerated a trend of increasing anxiety that was already occurring. “The prevalence of major depressive disorder among graduate and professional students is two times higher in 2020 compared to 2019 and the prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder is 1.5 times higher than in 2019” As reported by Chirikov et al (2020) from the UC Berkeley SERU Consortium Reports.

This increase in anxiety has both short and long term performance and health consequences. Severe anxiety reduces cognitive functioning and is a risk factor for early dementia (Bierman et al., 2005; Richmond-Rakerd et al, 2022). It also increases the risk for asthma, arthritis, back/neck problems, chronic headache, diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, pain, obesity and ulcer (Bhattacharya et al., 2014; Kang et al, 2017).

The most commonly used treatment for anxiety are pharmaceutical and cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) (Kaczkurkin & Foa, 2015). The anti-anxiety drugs are usually benzodiazepines (e.g., alprazolam (Xanax), clonazepam (Klonopin), chlordiazepoxide (Librium), diazepam (Valium) and lorazepam (Ativan). Although these drugs they may reduce anxiety, they have numerous side effects such as drowsiness, irritability, dizziness, memory and attention problems, and physical dependence (Shri, 2012; Crane, 2013).

Cognitive behavior therapy techniques based upon the assumption that anxiety is primarily a disorder in thinking which then causes the symptoms and behaviors associated with anxiety. Thus, the primary treatment intervention focuses on changing thoughts.

Given the significant increase in anxiety and the potential long term negative health risks, there is need to provide educational strategies to empower students to prevent and reduce their anxiety. A holistic approach is one that assumes that body and mind are one and that soma/body, emotions and thoughts interchangeably affect the development of anxiety. Initially in our research, Peper, Lin, Harvey & Perez (2017) reported that it was easier to access hopeless, helpless, powerless and defeated memories in a slouched position than an upright position and it was easier to access empowering positive memories in an upright position than a slouched position. Our research on transforming hopeless, helpless, depressive thought to empowering thoughts, Peper, Harvey & Hamiel (2019) found that it was much more effective if the person first shifts to an upright posture, then begins slow diaphragmatic breathing and finally reframes their negative to empowering/positive thoughts. Participants were able to reframe stressful memories much more easily when in an upright posture compared to a slouched posture and reported a significant reduction in negative thoughts, anxiety (they also reported a significant decrease in negative thoughts, anxiety and tension as compared to those attempting to just change their thoughts).

The strategies to reduce anxiety focus on breathing and posture change. At the same time there are many other factors that may contribute the onset or maintenance of anxiety such as social isolation, economic insecurity, etc. In addition, low glucose levels can increase irritability and may lower the threshold of experiencing anxiety or impulsive behavior (Barr, Peper, & Swatzyna, 2019; Brad et al, 2014). This is often labeled as being “hangry” (MacCormack & Lindquist, 2019). Thus, by changing a high glycemic diet to a low glycemic diet may reduce the somatic discomfort (which can be interpreted as anxiety) triggered by low glucose levels. In addition, people are also sitting more and more in front of screens. In this position, they tend to breathe quicker and more shallowly in their chest.

Shallow rapid breathing tends to reduce pCO2 and contributes to subclinical hyperventilation which could be experienced as anxiety (Lum, 1981; Wilhelm et al., 2001; Du Pasquier et al, 2020). Experimentally, the feeling of anxiety can rapidly be evoked by instructing a person to sequentially exhale about 70 % of the inhaled air continuously for 30 seconds. After 30 seconds, most participants reported a significant increase in anxiety (Peper & MacHose, 1993). Thus, the combination of sitting, shallow breathing and increased stress from the pandemic are all cofactors that may contribute to the self-reported increase in anxiety.

To reduce anxiety and discomfort, McGrady and Moss (2013) suggested that self-regulation and stress management approaches be offered as the initial treatment/teaching strategy in health care instead of medication. One of the useful approaches to reduce sympathetic arousal and optimize health is breathing awareness and retraining (Gilbert, 2003).

Stress management as part of a university holistic health class

Every semester since 1976, up to 180 undergraduates have enrolled in a three-unit Holistic Health class on stress management and self-healing (Klein & Peper, 2013). Students in the class are assigned self-healing projects using techniques that focus on awareness of stress, dynamic regeneration, stress reduction imagery for healing, and other behavioral change techniques adapted from the book, Make Health Happen (Peper, Gibney & Holt, 2002).

82% of students self-reported that they were ‘mostly successful’ in achieving their self-healing goals. Students have consistently reported achieving positive benefits such as increasing physical fitness, changing diets, reducing depression, anxiety, and pain, eliminating eczema, and even reducing substance abuse (Peper et al., 2003; Bier et al., 2005; Peper et al., 2014).

This assessment reports how students’ anxiety decreased after five weeks of daily practice. The students filled out an anonymous survey in which they rated the change in their discomfort after practicing effortless diaphragmatic breathing. More than 70% of the students reported a decrease in anxiety. In addition, they reported decreases in symptoms of stress, neck and shoulder pain as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Self-report of decrease in symptoms after practice diaphragmatic breathing for a week.

In comparing the self-reported responses of the students in the holistic health class to those of the control group (N=12), the students in the holistic health class reported a significant decrease in symptoms since the beginning of the semester as compared to the control group as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Change in self-reported symptoms after 6 weeks of practice the integrated holistic health skills as compared to the control group who did not practice these skills.

Changes in symptoms Most students also reported an increase in mental clarity and concentration that improved their study habits. As one student noted: Now that I breathe properly, I have less mental fog and feel less overwhelmed and more relaxed. My shoulders don’t feel tense, and my muscles are not as achy at the end of the day.

The teaching components for the first five weeks included a focus on the psychobiology of stress, the role of posture, and psychophysiology of respiration. The class included didactic presentations and daily self-practice

Lecture content

- Diadactic presentation on the physiology of stress and how posture impacts health.

- Self-observation of stress reactions; energy drain/energy gain and learning dynamic relaxation.

- Short experiential practices so that the student can experience how slouched posture allows easier access to helpless, hopeless, powerless and defeated memories.

- Short experiential breathing practices to show how breathing holding occurs and how 70% exhalation within 30 seconds increases anxiety.

- Didactic presentation on the physiology of breathing and how a constricted waist tends to have the person breathe high in their chest (the cause of neurasthemia) and how the fight/flight response triggers chest breathing, breath holding and/or shallow breathing.

- Explanation and practice of diaphragmatic breathing.

Daily self-practice