Welcome the New Year with Inspiration

Posted: December 22, 2025 Filed under: attention, behavior, CBT, cognitive behavior therapy, emotions, healing, health, mindfulness, self-healing | Tags: hope, Inspreiation, meaning, post=traumatic growth, purpose, resilience 1 CommentAs the holiday season begins, I find myself looking back on all that has unfolded this year and looking forward with hope to the year ahead. My social media feed is full of touching, uplifting messages and videos—reminders of resilience, creativity, and the simple goodness in the world. Best wishes for the holidays and the New Year and I hope you will enjoy the two inspiring videos.

1. Nine life lessons from comedian Tim Minchin, presented at the University of Western Australia. His humor and wisdom offer a refreshing take on what truly matters.

2. A powerful story about transforming disaster into blessing.

If you ever feel stuck or unsure about the future, this video is a beautiful reminder that unexpected turns can lead to new possibilities.

Wishing you a healthy and inspiring New Year!

Erik

Reduce Interpersonal Stress*

Posted: December 4, 2025 Filed under: attention, behavior, Breathing/respiration, CBT, emotions, Exercise/movement, healing, health, meditation, mindfulness, Pain/discomfort, stress management | Tags: health, mental-health, nutrition, wellness 2 CommentsAdapted from: Peper, E. & Harvey, R. Adjunctive techniques to reduce interpersonal stress at home. Biofeedback. 53(3), 54-57. https://rdcu.be/eMJqt

Stress often triggers defensive reactions—manifesting as anger, frustration, or anxiety that may mirror fight-or-flight responses. These reactions can reduce rational thinking, increase long-term health risks, and contribute to psychological and physiological disorders. and complicate the management of specific symptoms. Outlined are some pragmatic techniques that can be implemented during the day to interrupt and reduce stress.

After we had been living in our house for a few years, a new neighbor moved in next door. Within months, she accused us of moving things in her yard, blamed us when there was a leak in her house, claimed we were blowing leaves from her property onto other neighbors’ properties, and even screamed at her tenants to the extent that the police were called numerous times. Just looking at her house through the window was enough to make my shoulders tighten and leave me feeling upset.

When I drove home and saw her standing in front of her house, I would drive around the block one more time to avoid her while . . . feeling my body contract. Often, when I woke up in the morning, I would already anticipate conflict with my neighbor. I would share stories of my disturbing neighbor and her antics with my friends. They were very supportive and agreed with me that she was crazy. However, the acknowledgment and validation from my friends did not resolve my anger or indignation or the anxiety that was triggered whenever I saw my neighbor or thought of her. I spent far too much time anticipating and thinking about her, which resulted in tension in my own body—my heart rate would increase, and my neck and shoulders would tighten.

I decided to change. I knew I could not change her; however, I could change my reactivity and perspective. Thus, I practiced a “pause and recenter” technique. At the first moment of awareness that I was thinking about her or her actions, I would change my posture by sitting up straight, begin looking upward, breathe lower and slower, and then, in my mind’s eye, send a thought of goodwill streaming to her like an ocean wave flowing through and around her in the distance. I chose to do this series of steps because I believe that within every person, no matter how crazy or cruel, there is a part that is good, and it is that part I want to support.

I repeated this pause and recenter technique many times, especially whenever I looked in the direction of her house or saw her in her yard. I also reframed and reappraised her aggressive, negative behavior as her way of coping with her own demons. Three months later, I no longer reacted defensively. When I see her, I can say hello and discuss the weather without triggering my defensive reaction. I feel so much more at peace living where I am.

When stressed, angry, rejected, frustrated, or hurt, we so often blame the other person (Leary, 2015). The moment we think about that person or event, our anger, indignation, resentment, and frustration are triggered. We keep rehashing what happened. As we relive the experiences in our mind, we are unaware that we are also reliving bodily reactions to past events.

We are often unaware of the harm we are doing to ourselves until we experience physical symptoms such as high blood pressure, gastrointestinal distress, and muscle tightness along with behavioral and psychological symptoms such as insomnia, anxiety, or depression (Carney et al., 2006; Gerin et al., 2012). As we think of past events or interact again with a person involved in those past events, our body automatically responds with a defense reaction as if we were being threatened again in the present moment.

This defense reaction to memory of past threats from a “crazy” neighbor activates our fight-or-flight responses and increases sympathetic activation so that we can run faster and fight more ferociously to survive; however, this reaction also reduces blood flow through the frontal cortex—a process that reduces our ability to think rationally (van Dinther et al., 2024; Willeumier, et al., 2011). When we become so upset and stressed that our mind is captured by the other person, this reaction contributes to symptoms of chronic stress such as an increase in hypertension, myofascial pain, depression, insomnia, cardiovascular disease, and other chronic disorders (Duan et al., 2022; Russell et al., 2015; Suls, 2013).

Sharing our frustrations with friends and others is normal. It feels good to blame people for their personal limitations or mental illness; however, over time, blaming others avoids building adaptive capacity in strengthening skills that reduce chronic stress reactions (Fast & Tiedens, 2010; Lou et al., 2023). The time spent rehashing and justifying our feelings diminishes the time we spend in the present moment and our focus on upcoming opportunities.

In the moment of an encounter with a difficult neighbor, we may not realize that we have a choice. Some people keep living and reacting to past hurts or losses perpetually. Some people can learn to let go and/or forgive and make space in favor of considering new opportunities for learning and growth. Although the choice is ours, it is often very challenging to implement—even with the best intentions—because we react automatically when reminded of past hurts (seeing that person, anticipating meeting or actually meeting that person who caused the hurt, or being triggered by other events that evoke memories of the pain).

What Can You Do

Choose to change your response. Choose to reduce reactivity. Choosing adaptive reactions does not mean you condone what happened or agree that the other person was right. You are just choosing to live your life and not continue to be captured by nor react to the previous triggers. Many people report that after implementing some of the practices described below along with many other stress management techniques, their automatic reactivity was noticeably decreased. They report that their chronic stress symptoms were reduced and they have the freedom to live in present instead of being captured by the painful past.

Pause and Recenter by Sending Goodwill

Our automatic reaction to the trigger elicits a defense reaction that reduces our ability to think rationally. Therefore, the moment you anticipate or begin to react, take three very slow diaphragmatic breaths, inhaling for approximately 4–5 seconds and exhaling for about 5–6 seconds, where one in-and-out breath takes about 10 seconds to complete. As you inhale, allow your abdomen to expand; then as you exhale, slowly make yourself tall and look up. Looking up allows easier access to empowering and positive memories (Peper et al., 2017).

Continue looking up, inhaling slowly to allow the abdomen to expand. Repeat this slow breath again. On the third long, slow breath, while looking up, evoke a memory of someone in whose presence you felt at peace and who loves you, such as your grandmother, aunt, uncle, or even a pet. Reawaken positive feelings associated with memories of being loved. Allow a smile inwardly or outwardly and soften your eyes as you experience the loving memory.

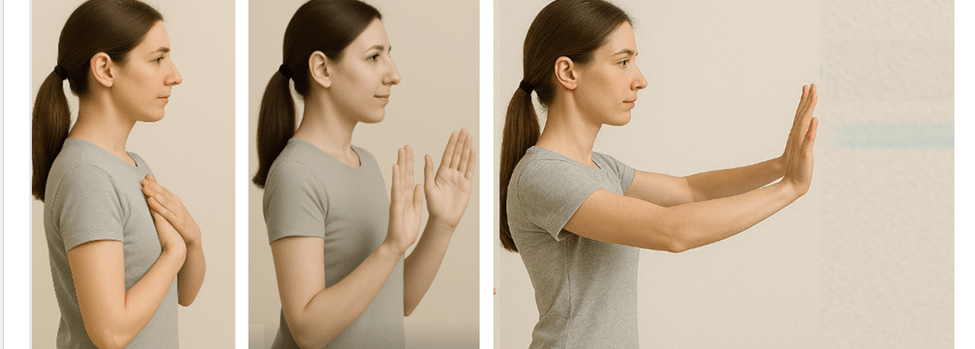

Next, put your hands on your chest, take another long slow breath as your abdomen expands, and as you exhale bring your hands away from your chest and stretch them out in front of you. At the same time in your mind’s eye, imagine sending goodwill to that person involved in the interpersonal conflict that previously evoked your stress response. As if you are sending an ocean wave that is streaming outward to the person.

As you do the pause and recenter technique, remember you are not condoning what happened; instead, you are sending goodwill to that person’s positive aspect. From this perspective, everyone has an intrinsic component—however small—that some label as the individual’s human potential, Christ nature or Buddha nature.

Why would this be effective? This practice short-circuits the automatic stress response and provides time to recenter, interrupting ongoing rumination by shifting the mind away from thoughts about the person or event that induced stress toward a positive memory. By evoking a loving memory from the past, we facilitate a reduction in arousal, evoke a positive mood, and decrease sympathetic nervous system activation (Speer & Delgado, 2017). Slower diaphragmatic breathing also reduces sympathetic activation (Birdee et al., 2023; Siedlecki et al., 2022). By combining body-centered and mind-centered techniques, we can pause and create the opportunity to respond positively rather than reacting with anger and hurt.

Practice Sending Goodwill the Moment You Wake Up

So often when we wake up, we anticipate the challenges, and even the prospect of interacting with a person or event heightens our defense reaction. Therefore, as soon as you wake up, sit at the edge of the bed, repeat the previous practice, pause, and center. Then, as you sit at the edge of the bed, slightly smile with soft eyes, look up, and inhale as your abdomen expands. Then, stamp a foot into the floor while saying, “Today is a new day.” Next, inhale, allowing your abdomen to expand; as you look up, stamp the opposite foot on the floor while saying, “Today is a new day.” Finally, send goodwill to the person who previously triggered your defensive reaction.

Why would this be effective? Looking up makes it easier to access positive memories and thoughts. Stamping your foot on the ground is a nonverbal expression of determination and anchors the thought of a new day, thereby focusing on new opportunities (Feldman, 2022).

Interrupt the Stress Response with the ABCs

The moment you notice discomfort, pain, stress, or negative thoughts, interrupt the cycle with a simple ABC strategy (Peper, 2025):

- Adjust posture and look up

- Breathe by allowing your abdomen to relax and expand while inhaling

- Change your internal dialogue, smile and focus on what you want to do

Why would this be effective? By shifting your posture and gently looking upward, you make it easier to access positive and empowering memories and thoughts (Peper et al., 2019). This simple change in body position can interrupt habitual stress responses and open the doorway to more constructive states.

Slow, diaphragmatic breathing further supports this process by reducing sympathetic arousal and restoring a sense of calm. As your breathing deepens, clarity of mind increases, allowing you to respond rather than react (Peper et al, 2024b; Matto et al, 2025).

Equally important is transforming critical, judgmental, or negative self-talk into affirmative, supportive statements. Describe what you want to do—rather than what you want to avoid. This reframing creates a clear internal guide and significantly increases the likelihood that you will achieve your desired goals.

Complete the Alarm Reaction a Burst of Physical Activity

When you feel overwhelmed and fully captured by a stress reaction, one of the most effective strategies is to complete the fight-flight response with a brief burst of intense physical activity. This momentary action such as running in place, vigorously shaking your arms, or doing a few rapid push-offs from a wall (Peper et al., 2024a). After completing the physical activity implement your stress management strategies such as breathing, cognitive reframing, meditation, etc.

Why would this be effective? The intense physical activity discharges the excessive physiological arousal and interrupts the cycle of rumination. For practical examples and step-by-step guidance, see the article Quick Rescue Techniques When Stressed (Peper et al., 2024a) or the accompanying blog post: https://peperperspective.com/2024/02/04/quick-rescue-techniques-when-stressed/

Discuss Your Issue from the Third-Person Perspective

When thinking, ruminating, talking, texting, or writing about the event, discuss it from the third-person perspective. Replace the first-person pronoun “I” with “she” or “he.” For example, instead of saying “I was really pissed off when my boss criticized my work without giving any positive suggestions for improvement,” say “He was really pissed off when his boss criticized his work without offering any positive suggestions for improvement.”

Why would this be effective? The act of substituting the third-person pronoun for the first-person pronoun interrupts our automatic reactivity because it requires us to observe and change our language, which activates parts of the frontal cortex. This third-person/first-person process creates a psychological distance from our feelings, allowing for a more objective and calmer perspective on the situation, effectively reducing stress by stepping back from the immediate emotional response (Moser et al., 2017). This process can be interpreted as meaning that you are no longer fully captured by the emotions, as you are simultaneously the observer of your own inner language and speech.

Compare Yourself with Others Who are less Fortunate

When you feel sorry for yourself or hurt, take a breath, look upward, and compare yourself with others who are suffering much more. In that moment, consider yourself incredibly lucky compared with people enduring extreme poverty, bombings, or severe disfigurement. Be grateful for what you have.

Why would this be effective? Research shows that when we compare ourselves with people who are more successful, we tend to feel worse—especially when we have low self-esteem. However, when we compare ourselves with others who are suffering more, we tend to feel better (Aspinwall, & Taylor, 1993). This comparison relativizes our perspective on suffering, making our own hardships and suffering seem less significant compared with the severe suffering of others.

Conclusion

It is much easier to write and talk about these practices than to implement them. Reminding yourself to implement them can be very challenging. It requires significant effort and commitment. In some cases, the benefits are not experienced immediately; however, when practiced many times during the day for six to eight weeks, many people report feeling less resentment and experience a reduction in symptoms and improvements in health and relationships.

*This blog was inspired by the podcast “No Hard Feelings,” an episode on Hidden Brain produced by Shankar Vedantam (2025) that featured psychologist Fred Luskin, and the wisdom taught by Dora Kunz (Kunz & Peper, 1983, 1984a, 1984b, 1987).

See the following posts for more relevant information

References

Aspinwall, L. G., & Taylor, S. E. (1993). Effects of social comparison direction, threat, and self-esteem on affect, self-evaluation, and expected success. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(5), 708–722. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.64.5.708

Birdee, G., Nelson, K.,Wallston, K., Nian, H., Diedrich, A., Paranjape, S., Abraham, R., & Gamboa, A. (2023). Slow breathing for reducing stress: The effect of extending exhale. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2023.102937

Carney, C. E., Edinger, J. D., Meyer, B., Lindman, L., & Istre, T. (2006). Symptom-focused rumination and sleep disturbance. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 4(4), 228–241. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15402010bsm0404_3

Defayette, A. B., Esposito-Smythers, C., Cero, I., Harris, K. M.,Whitmyre, E. D., & López, R. (2023). Interpersonal stress and proinflammatory activity in emerging adults with a history of suicide risk: A pilot study. Journal of Mood and Anxiety Disorders, 2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xjmad.2023.100016

Dienstbier, R. A. (1989). Arousal and physiological toughness: Implications for mental and physical health. Psychological Review, 96(1), 84. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-95x.96.1.84

Duan, S., Lawrence, A., Valmaggia, L., Moll, J., & Zahn, R. (2022). Maladaptive blame-related action tendencies are associated with vulnerability to major depressive disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 145, 70–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.11.043

Fast, N. J., & Tiedens, L. Z. (2010). Blame contagion: The automatic transmission of self-serving attributions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46(1), 97–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.10.007

Feldman, Y. (2022). The dialogical dance–A relational embodied approach to supervision. In C. Butte & T. Colbert (Eds.), Embodied approaches to supervision: The listening body (chap. 2). Routledge. https://www.amazon.com/Embodied-Approaches-Supervision-C%C3%A9line-Butt%C3%A9/dp/0367473348

Gerin,W., Zawadzki,M. J., Brosschot, J. F., Thayer, J. F., Christenfeld, N. J., Campbell, T. S., & Smyth, J. M. (2012). Rumination as a mediator of chronic stress effects on hypertension: A causal model. International Journal of Hypertension, 2012, 453465. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/453465

Hase, A., O’Brien, J., Moore, L. J., & Freeman, P. (2019). The relationship between challenge and threat states and performance: A systematic review. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 8(2), 123. https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000132

Hassamal, S. (2023). Chronic stress, neuroinflammation, and depression: An overview of pathophysiological mechanisms and emerging anti-inflammatories. Frontiers in Psychiatry,

14, 1130989. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1130989

Kunz, D., & Peper, E. (1983). Fields and their clinical implications—Part III: Anger and how it affects human interactions. The American Theosophist, 71(6), 199–203. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280777019_Fields_and_their_clinical_implications-Part_III_Anger_and_how_it_affects_human_interactions

Kunz, D., & Peper, E. (1984a). Fields and their clinical implications IV: Depression from the energetic perspective: Etiological underpinnings. The American Theosophist, 72(8), 268–275. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280884054_Fields_and_their_clinical_implications_Part_IV_Depression_from_the_energetic_perspective-Etiological_underpinnings

Kunz, D., & Peper, E. (1984b). Fields and their clinical implications V: Depression from the energetic perspective: Treatment strategies. The American Theosophist, 72(9), 299–306. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280884158_Fields_and_their_clinical_implications_Part_V_Depression_from_the_energetic_perspective-Treatment_strategies

Kunz, D., & Peper, E. (1987). Resentment: A poisonous undercurrent. The Theosophical Research Journal, IV(3), 54–59. Also in: Cooperative Connection, IX(1), 1–5. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/387030905_Resentment_Continued_from_page_4

Leary, M. R. (2015). Emotional responses to interpersonal rejection. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 17(4), 435–441. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2015.17.4/mleary

Lou, Y., Wang, T., Li, H., Hu, T. Y., & Xie, X. (2023). Blame others but hurt yourself: Blaming or sympathetic attitudes toward victims of COVID-19 and how it alters one’s health status. Psychology & Health, 39(13), 1877–1898. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2023.2269400

Matto, D., Peper, E., & Harvey, R. (2025). Monitoring and coaching breathing patterns and rate. Townsend Letter-Innovative Health Perspectives. https://townsendletter.com/monitoring-and-coaching-breathing-patterns-and-rate/

Moser, J. S., Dougherty, A., Mattson, W. I., Katz, B., Moran, T. P.,Guevarra, D., Shablack, H.,Ayduk,O., Jonides, J., Berman, M. G., & Kross, E. (2017). Third-person self-talk facilitates emotion regulation without engaging cognitive control: Converging evidence from ERP and fMRI. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 4519. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-04047-3

Peper, E. (2025). Breathe Away Menstrual Pain- A Simple Practice That Brings Relief. the peper perspective-ideas on illness, health and well-being from Erik Peper. https://peperperspective.com/2025/11/22/6825/

Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Hamiel, D. (2019). Transforming thoughts with postural awareness to increase therapeutic and teaching efficacy. NeuroRegulation, 6(3), 153-169. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.6.3.1533-1

Peper, E., Lin, I.-M., Harvey, R., & Perez, J. (2017). How posture affects memory recall and mood. Biofeedback, 45(2), 36–41. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-45.2.01

Peper, E., Oded, Y., & Harvey, R. (2024a). Quick somatic rescue techniques when stressed. Biofeedback, 52(1), 18–26. https://doi.org/10.5298/982312

Peper, E., Oded, Y., Harvey, R., Hughes, P., Ingram, H., & Martinez, E. (2024b). Breathing for health: Mastering and generalizing breathing skills. Townsend Letter-Innovative Health Perspectives. November 15, 2024. https://townsendletter.com/suggestions-for-mastering-and-generalizing-breathing-skills/

Russell, M. A., Smith, T. W., & Smyth, J. M. (2015). Anger expression, momentary anger, and symptom severity in patients with chronic disease. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 50(2), 259–271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-015-9747-7

Siedlecki, P., Ivanova, T. D., Shoemaker, J. K., & Garland, S. J. (2022). The effects of slow breathing on postural muscles during standing perturbations in young adults. Experimental Brain Research, 240, 2623–2631. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-022-06437-0

Speer, M. E., & Delgado, M. R. (2017). Reminiscing about positive memories buffers acute stress responses. Nature Human Behaviour, 1, 0093. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-017-0093

Suls, J. (2013). Anger and the heart: Perspectives on cardiac risk, mechanisms and interventions. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases, 55(6), 538–547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2013.03.002

van Dinther, M., Hooghiemstra, A. M., Bron, E. E., Versteeg, A., et al. (2024). Lower cerebral blood flow predicts cognitive decline in patients with vascular cognitive impairment. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, 20(1), 136–144. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.13408

Vedantam, S. (2025). No hard feelings. Hidden brain. Accessed February 5, 2025. https://hiddenbrain.org/podcast/no-hard-feelings/

Willeumier, K., Taylor, D. V., & Amen, D. G. (2011). Decreased cerebral blood flow in the limbic and prefrontal cortex using SPECT imaging in a cohort of completed suicides. Translational Psychiatry, 1(8), e28. https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2011.28

Zannas, A. S., & West, A. E. (2014). Epigenetics and the regulation of stress vulnerability and resilience. Neuroscience, 264, 157–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.12.003

Breathe Away Menstrual Pain- A Simple Practice That Brings Relief *

Posted: November 22, 2025 Filed under: attention, behavior, biofeedback, Breathing/respiration, cognitive behavior therapy, education, emotions, Neck and shoulder discomfort, Pain/discomfort, posture, relaxation, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: dysmenorrhea, health, meditation, menstrual cramps, mental-health, mindfulness, wellness 2 CommentsAdapted from: Peper, E. Harvey, R., Chen, & Heinz, N. (2025). Practicing diaphragmatic breathing reduces menstrual symptoms both during in-person and synchronous online teaching. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, Published online: 25 October 2025. https://rdcu.be/eMJqt https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-025-09745-7

“Once again, the pain starts—sharp, deep, and overwhelming—until all I can do is curl up and wait for it to pass. There’s no way I can function like this, so I call in sick. The meds take the edge off, but they don’t really fix anything—they just mask it for a little while. I usually don’t tell anyone it’s menstrual pain; I just say I’m not feeling well. For the next couple of days, I’m completely drained, struggling just to make it through.

Many women experience discomfort during menstruation, from mild cramps to intense, even disabling pain. When the pain becomes severe, the body instinctively responds by slowing down—encouraging rest, curling up to protect the abdomen, and often reaching for medication in hopes of relief. For most, the symptoms ease within a day or two, occasionally stretching into three, before the body gradually returns to balance.

Another helpful approach is to practice slow abdominal breathing, guided by a breathing app FlowMD. In our study led by Mattia Nesse, PhD, in Italy, the response of one 22-year-old woman illustrated the power of this simple practice.

“Last night my period started, so I was a bit discouraged because I knew I’d get stomach pain, etc. On the other hand, I said, “Okay, let’s see if the breathing works,” and it was like magic — incredible. I’ll need to try it more times to understand whether it consistently has the same effect, but right now it truly felt magical. Just 3 minutes of deep breathing with the app were enough, and I’m not saying I don’t feel any pain anymore, but it has decreased a lot, so thank you! Thank you again for this tool… I’m really happy!”

The Silent Burden of Menstrual Pain

Menstrual pain, or dysmenorrhea, affects most women at some point in their lives — often silently. For many, the monthly cycle brings not only physical discomfort but also shame, fatigue, and interruptions to work or school. It is one of the leading causes of absenteeism and reduced productivity worldwide (Itani et al., 2022; Thakur & Pathania, 2022). In addition, the estimated health cost ranged from US $1367 to US$ 7043 per year (Huang et al., 2021). Yet, despite its prevalence, most women are never taught how to use their own physiology to ease these symptoms.

The Study (Peper et al, 2025)

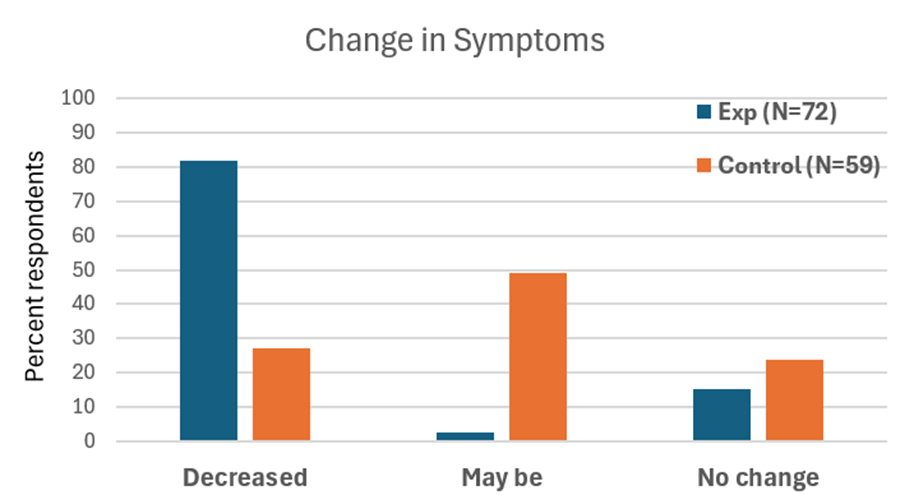

Seventy-five university women participated across two upper-division Holistic Health courses. Forty-nine practiced 30 minutes per day of breathing and relaxation over five weeks as well as practicing the moment they anticipated or felt discomfort; twenty-six served as a comparison group without a specific daily self-care routine. Students rated change in menstrual symptoms on a scale from –5 (“much worse”) to +5 (“much better”). For the detailed steps in training, see the blog: https://peperperspective.com/2023/04/22/hope-for-menstrual-cramps-dysmenorrhea-with-breathing/ (Peper et al., 2023).

What changed

The results were striking. Women who practiced breathing and relaxation showed significant decrease in menstrual symptoms compared to the non-intervention group (p = 0.0008) as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Decrease in menstrual symptoms as compared to the control group after implementing slow diaphragmatic breathing.

Why does breathing and posture change have a beneficial effect?

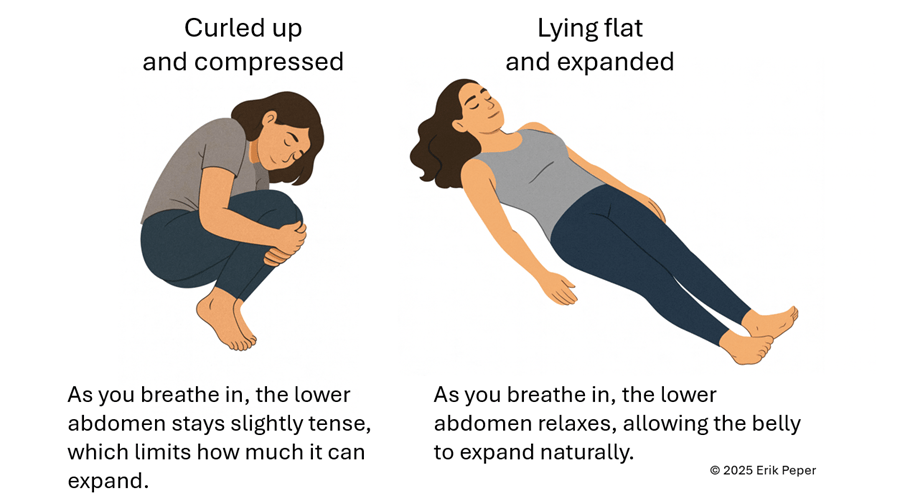

When you stay curled up, your abdomen becomes compressed, leaving little room for the lower belly to relax or for the diaphragm to move freely. The result? Tension builds, and pain often increases.

To reverse this, create space for relaxation. Gently loosen your waist and let your abdomen expand as you inhale. Uncurl your body—lengthen your spine and open your chest, as shown in Figure 2. With each easy breath, you invite calm and allow your body to shift from tension to ease.

Figure 2. Curling up compresses the abdomen and prevents relaxation of the lower belly. In contrast, lying flat with the body gently expanded allows the abdomen to move freely with each breath, which can help reduce menstrual discomfort.

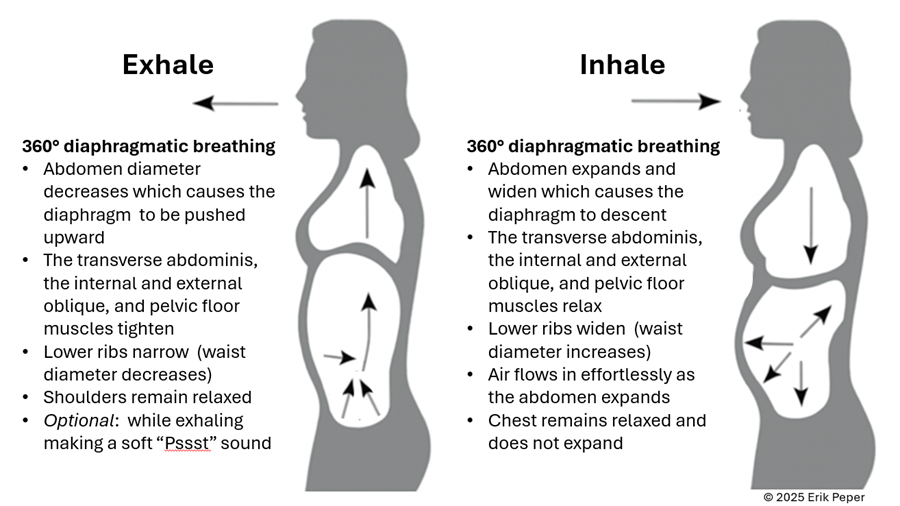

In contrast, slow abdominal or diaphragmatic breathing activates the body’s natural relaxation response. It quiets the stress-driven sympathetic nervous system, calms the mind, and improves circulation in the abdominal area. With each slow breath in, the abdomen gently expands while the pelvic floor and abdominal muscles relax. As you exhale, these muscles naturally tighten slightly, helping to massage and move blood and lymph through the abdominal region. This rhythmic movement supports healing and ease, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3. The dynamic process of diaphragmatic breathing.

The process of slower, lower diaphragmatic breathing

When lying down, rest comfortably on your back with your legs slightly apart. Allow your abdomen to rise naturally as you inhale and fall as you exhale. As you breathe out, imagine the air flowing through your abdomen, down your legs, and out through your feet. To deepen this sensation, you can ask a partner to gently stroke from your abdomen down your legs as you exhale—helping you sense the flow of release through your body.

Gently focus on slow, effortless diaphragmatic breathing. With each inhalation, your abdomen expands, and the lower belly softens. As you exhale, the abdomen gently goes down pushing the diaphragm upward and allowing the air to leave easily. Breathing slowly—about six breaths per minute—helps engage the body’s natural relaxation response.

If you notice that your breath is staying high in your chest instead of expanding through the abdomen, your symptoms may not improve and can even increase. One participant experienced this at first. After learning to let her abdomen expand with each inhalation while keeping her shoulders and chest relaxed, her next menstrual cycle was markedly easier and far less uncomfortable. The lesson is clear: technique matters.

“During times of pain, I practiced lying down and breathing through my stomach… and my cramps went away within ten minutes. It was awesome.” — 22-year-old college student

“Whenever I felt my cramps worsening, I practiced slow deep breathing for five to ten minutes. The pain became less debilitating, and I didn’t need as many painkillers.” — 18-year-old college student

These successes point out that it’s not just breathing — it’s how you breathe by providing space for the abdomen to expand during inhalation.

Practice: How to Do Diaphragmatic Breathing

- Find a quiet space. Lie on your back or sit comfortably erect with your shoulders relaxed.

- Place one hand on your chest and one on your abdomen.

- Inhale slowly through your nose for about 3–4 seconds. Let your abdomen expand as you breathe in — your chest should remain relaxed.

- Exhale gently through your mouth for 4—6 seconds, allowing the abdomen to fall or constrict naturally.

- As you exhale imagine the air moving down your arms, through your abdomen, down your legs, and out your feet

- Practice daily for 20 minutes and also for 5–10 minutes during the day when menstrual discomfort begins.

- Add warmth. Placing a warm towel or heating pad over your abdomen can enhance relaxation while lying on your back and breathing slowly.

With regular practice and implementing it during the day when stressed, this simple method can reduce cramps, promote calm, and reconnect you with your body’s natural rhythm.

Implement the ABCs during the day

The ABC sequence—adapted from the work of Dr. Charles Stroebel, who developed The Quieting Reflex (Stroebel, 1982)—teaches a simple way to interrupt stress reactions in real time. The moment you notice discomfort, pain, stress, or negative thoughts, interrupt the cycle with a simple ABC strategy:

A — Adjust your posture

Sit or stand tall, slightly arch your lower back and allowing the abdomen to expand while you inhale and look up. This immediately shifts your body out of the collapsed “defense posture’ and increases access to positive thoughts (Tsai et all, 2016; Peper et al., 2019)

B — Breathe

Allow your abdomen to expand as you inhale slowly and deeply. Let it get smaller as you exhale. Gently make a soft hissing sound as you exhale while helps the abdomen and pelvic floor to tighten. Then allow the abdomen to relax and widen which without effort draws the air in during inhalation. As you exhale, stay tall and imagine the air flowing through you and down your legs and out your feet.

C — Concentrate

Refocus your attention on what you want to do and add a gentle smile. This engages positive emotions, the smile helps downshift tension.

The video clip guides you through the ABCs process.

Integrate the breathing during the day by implementing your ABCs

When students practice relaxation technique and this method, they reported greater reductions in symptoms compared with a control group. By learning to notice tension and apply the ABC steps as soon as stress arises, they could shift their bodies and minds toward calm more quickly, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Change in symptoms after practicing a sequential relaxation and breathing techniques for four weeks.

Takeaway

Menstrual pain doesn’t have to be endured in silence or masked by medication alone. By practicing 30 minutes of slow diaphragmatic breathing daily and many times during the day, women may be able to reduce pain, stress, and discomfort — while building self-awareness and confidence in their body’s natural rhythms thereby having the opportunity to be more productive.

We recommend that schools and universities include self-care education—especially breathing and relaxation practices—as part of basic health curricula as this approach is scalable. Teaching young women to understand their bodies, manage stress, and talk openly about menstruation can profoundly improve well-being. It not only reduces physical discomfort but also helps dissolve the stigma that still surrounds this natural process,

Remember: Breathing is free—available anytime, anywhere and is helpful in reducing pain and discomfort. (Peper et al., 2025; Joseph et al., 2022)

See the following blogs for more in-depth information and practical tips on how to learn and apply diaphragmatic breathing:

REFERENCES

Itani, R., Soubra, L., Karout, S., Rahme, D., Karout, L., & Khojah, H.M.J. (2022). Primary Dysmenorrhea: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment Updates. Korean J Fam Med, 43(2), 101-108. https://doi.org/10.4082/kjfm.21.0103

Huang, G., Le, A. L., Goddard, Y., James, D., Thavorn, K., Payne, M., & Chen, I. (2022). A systematic review of the cost of chronic pelvic pain in women. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada, 44(3), 286–293.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogc.2021.08.011

Joseph, A. E., Moman, R. N., Barman, R. A., Kleppel, D. J., Eberhart, N. D., Gerberi, D. J., Murad, M. H., & Hooten, W. M. (2022). Effects of slow deep breathing on acute clinical pain in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Evidence-Based Integrative Medicine, 27, 2515690X221078006. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515690X221078006

Peper, E., Booiman, A. & Harvey, R. (2025). Pain-There is Hope. Biofeedback, 53(1), 1-9. http://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-53.01.16

Peper, E., Chen, S., Heinz, N., & Harvey, R. (2023). Hope for menstrual cramps (dysmenorrhea) with breathing. Biofeedback, 51(2), 44–51. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-51.2.04

Peper, E., Harvey, R., Chen, S., & Heinz, N. (2025). Practicing diaphragmatic breathing reduces menstrual symptoms both during in-person and synchronous online teaching. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. Published online: 25 October 2025. https://rdcu.be/eMJqt https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-025-09745-7

Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Hamiel, D. (2019). Transforming thoughts with postural awareness to increase therapeutic and teaching efficacy. NeuroRegulation, 6(3),153-169. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.6.3.1533-1

Stroebel, C. (1982). The Quieting Reflex. New York: Putnam Pub Group. https://www.amazon.com/Qr-Quieting-Charles-M-D-Stroebel/dp/0399126570/

Thakur, P. & Pathania, A.R. (2022). Relief of dysmenorrhea – A review of different types of pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments. MaterialsToday: Proceedings.18, Part 5, 1157-1162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2021.08.207

Tsai, H. Y., Peper, E., & Lin, I. M. (2016). EEG patterns under positive/negative body postures and emotion recall tasks. NeuroRegulation, 3(1), 23-27. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.3.1.23

*Edited with the help of ChatGPT 5

Ensorcelled: Breaking the Digital Enchantment

Posted: October 7, 2025 Filed under: ADHD, attention, behavior, cellphone, computer, digital devices, education, emotions, healing, health, laptops, techstress, Uncategorized | Tags: anxiety, depression, health, human connection, life, loneliness, media addictdion, mental-health, storytelling 1 Comment

My mom called, “Stop playing on your computer and come for dinner!” I heard her, but I was way too into my game. It felt like I was actually inside it. I think I yelled “Yeah!” back, but I didn’t move.

A few seconds later, I was totally sucked into this awesome world where I was conquering other galaxies. My avatar was super powerful, and I was winning this crazy battle.

Then, all of a sudden, my mom came into my room and just turned off the computer. I was so mad. I was about to win! The real world around me felt boring and empty. I didn’t even feel hungry anymore. I didn’t say anything, I just wanted to go back to my game.

For some, the virtual world feels more real and exciting than the actual one. It can seem more vivid precisely because they have not yet tasted the full, multi-dimensional richness of real human connection, those moments when you feel seen, touched, and understood.

This theme comes vividly alive in my son Eliot Peper’s new novella, Ensorcelled. I am so proud of him. He has crafted a story in which a young boy, captured by the spell of the immersive digital world, discovers that real-life experiences carry far deeper meaning. I won’t give away the plot, but the story creates the experience, it doesn’t just tell it. It reminds us that meaning and belonging arise through genuine connection, not through screens. As Eliot writes, “Sometimes a story is the only thing that can save your life.” It’s a story everyone should read.

The effects of our immersive digital world

Our new world of digital media can take over the reality of actual experiences. It is no wonder that more young people feel stressed and have social anxiety when they have to make an actual telephone call instead of texting (Jin, 2025). They also experience a significant increase in anxiety and depression and feel more awkward initiating in-person social communication with others. The increase in mental health problems and social isolation affects predominantly those who are cellphone and social media natives; namely, those who started to use social media after Facebook was released in 2004 and the iPhone in 2007 (Braghieri et al., 2022).

Students who are most often on their phone whether streaming videos, scrolling, texting, watching YouTube, Instagram or TikTok, and more importantly responding to notifications from phones when they are socializing, report higher levels of loneliness, depression and anxiety as shown inf Figure 1 (Peper & Harvey 2018). They also report less positive feelings and energy when they communicate with each other online as compared to in person (Peper & Harvey, 2024).

Figure 1. The those with the highest phone use were the most lonely, depressed and anxious (Peper and Harvey, 2018).

Even students’ sexual activity has decreased in U.S. high-school from 2013 to 2023 and young adults (ages 18-44) from 2000-2018 (CDC, 2023; Ueda et al., 2020). Much of this may be due to the reality that adolescents have reduced face-to-face socializing (dating, parties, going out) while increasing their time on digital media (Twenge et al., 2019).

What to do

As a parent it often feels like a losing battle to pull your child, or even yourself, away from the intoxicating digital media, since the digital world is supercharged with AI-generated media. It is all aimed at capturing eyeballs (your attention and time), resulting reducing genuine human social connection. (Peper at al., 2020; Haidt, 2024). To change behavior is challenging and yet rewarding. If possible, implement the following (Peper at al., 2020; Twenge, 2025; Haidt, 2024):

- Create tech-free zones. Keep phones and devices out of bedrooms, the dinner table, and family gatherings. Make these spaces sacred for real connection.

- Avoid screens before bedtime. Turn off screens at least an hour before bed. Replace scrolling with quiet reflection, reading, or gentle stretching. Read or tell actual stories before bedtime.

- Explore why we turn to digital media. Before you open an app, ask: Why am I doing this? Am I bored, anxious, or avoiding something? Awareness shifts behavior.

- Provide unstructured time. Let yourself and your children be bored sometimes. Boredom sparks creativity, imagination, and self-discovery.

- Create shared experiences. Plan family activities that don’t involve screens—cooking, hiking, playing music, or simply talking. Real connection satisfies what digital media only mimics.

- Implement social support. Coordinate with other parents, friends, or colleagues to agree on digital limits. Shared norms make it easier to follow through.

- Model what you want your children to do. Children imitate what they see. When adults practice digital restraint, kids learn that real life matters more than screen life.

We have a choice.

We can set limits now and experience real emotional connection and growth or become captured, enslaved, and manipulated by the corporate creators, producers and sellers of media.

Read Ensorcelled. which uses storytelling, the traditional way to communicate concepts and knowledge. Read it, share it. It may change your child’s life and your own.

Available from

Signed copy by author: https://store.eliotpeper.com/products/ensorcelled

Paperback: https://www.amazon.com/Ensorcelled-Eliot-Peper/dp/1735016535/

Kindle: https://www.amazon.com/Ensorcelled-Eliot-Peper-ebook/dp/B0FLGQC3BS/

References

Braghieri, L., Levy, R., & Makarin, A. (2022). Social Media and Mental Health (July 28, 2022) http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3919760

CDC. (2023). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). Youth Risk Behavior Survey: Data summary & trends report 2011–2021. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/index.htm

Haidt, J. (2024). The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness. New York: Penguin Press. https://www.amazon.com/Anxious-Generation-Rewiring-Childhood-Epidemic/dp/0593655036

Jin, B. (2025). Avoidance and Anxiety About Phone Calls in Young Adults: The Role of Social Anxiety and Texting Controllability. Communication Reports, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/08934215.2025.2542562

Peper, E. & Harvey, R. (2018). Digital addiction: increased loneliness, depression, and anxiety. NeuroRegulation. 5(1),3–8. doi:10.15540/nr.5.1.3 5(1),3–8. http://www.neuroregulation.org/article/view/18189/11842

Peper, E. & Harvey, R. (2024). Smart phones affects social communication, vision, breathing, and mental and physical health: What to do! Townsend Letter-Innovative Health Perspectives, September 15, 2024. https://townsendletter.com/smartphone-affects-social-communication-vision-breathing-and-mental-and-physical-health-what-to-do/

Peper, E., Harvey, R. & Faass, N. (2020). TechStress: How Technology is Hijacking Our Lives, Strategies for Coping, and Pragmatic Ergonomics. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books.

Ueda, P., Mercer, C. H., Ghaznavi, C., & Herbenick, D. (2020). Trends in frequency of sexual activity and number of sexual partners among adults aged 18 to 44 years in the US, 2000–2018. JAMA Network Open, 3(6), e203833. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3833

Twenge, J.M. (2025). 10 Rules for Raising Kids in a High-Tech World: How Parents Can Stop Smartphones, Social Media, and Gaming from Taking Over Their Children’s Lives. New York: Atria Books. https://www.amazon.com/Rules-Raising-Kids-High-Tech-World/dp/1668099993

Twenge, J. M., Spitzberg, B. H., & Campbell, W. K. (2019). Less in-person social interaction with peers among U.S. adolescents in the 21st century and links to loneliness. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 36(6), 1892-1913. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407519836170

This May Save Your Life! Bacteriophage Treatment for Bacterial Diseases*

Posted: September 11, 2025 Filed under: Evolutionary perspective, healing, health, Pain/discomfort, self-healing | Tags: antibiotic resistance, antibiotics, bacteria, bacteriohage, health, Medicine Leave a commentRecently, I listened to a special episode featuring Lina Zeldovich on her book The Living Medicine, from This Podcast Will Kill You. I was totally inspired because it discussesd the healing power of bacteriophages, which apparently treat antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections successfully, reportedly without side effects. (Bacterial phages are viruses that selectively kill specific bacteria and have been used to treat multi-antibiotic-resistant conditions).

This emerging therapy is an aspect of individualized treatment. Zeldovich reports that it can not only be used to treat, but also to prevent the occurrence of bacterial illnesses. I rushed out to buy the book, The Living Medicine: How a lifesaving cure was nearly lost and why it will rescue us when antibiotics fail. Zeldovich is a great science storyteller and the book really captured me. I read it in two evenings and wanted to share this information, since a day may come when it could save your life.

This is a must-read for all of us, particularly for health professionals. It offers hope through a non-toxic strategy in the fight against antibiotic-resistant disease. The book provides a perspective on the challenges of bringing this effective healing strategy to acceptance and implementation when cultural biases and financial disincentives have stood in the way.;

Zeldovich, describes the development and history of bacterial phage medicine and why it has taken so many years to become accepted in the West. Only after several high-profile cases has this approach become of interest. A prime example is the 2016 treatment of Dr. Tom Patterson, a professor at UC San Diego, who contracted a life-threatening Acinetobacter baumannii infection while traveling (Garnett, 2019). The bacteria that caused his infection was resistant to every available antibiotic. After he slipped into a coma, his doctors feared the worst. As a last resort, his wife, Dr. Steffanie Strathdee, worked with scientists to identify phages that could target the infection. Within 48 hours of receiving intravenous phage therapy, Patterson woke up. He went on to make a full recovery, one of the first documented cases in the U.S. in which phages saved a patient’s life.

Pros and cons of antibiotics

Until antibiotics were discovered, bacterial infections were often fatal. This changed with the discovery of penicillin by Alexander Fleming in 1928. During World War II, antibiotics saved countless solders’ lives in the treatment of infected wounds, pneumonia, and blood poisoning. The antibiotic approach was quickly adopted in the United States, beginning in the early 1940’s, since penicillin could be mass-produced and thus was highly profitable for the pharmaceutical companies. Despite the initial success of the drug, bacteria quickly developed antibiotic resistance to penicillin due to the ability of bacteria to produce β-lactamase, an enzyme capable of breaking down the drug.

Antibiotics were and are extraordinary drugs. When a patient is becoming sicker and sicker as a bacterial infection spreads, the infection can be stopped in its tracks with an effective antibiotic. Before the era of antibiotic resistance, patients recovered as if by magic, simple by giving an antibiotic orally or intravenously,

I still remember when our son developed pneumonia at the age of 12, initially with coughing, a high fever, chest pain, and a great deal of congestion. But as the infection progressed, he began to have difficulty breathing and his energy was fading. We were initially hesitant to give the prescribed antibiotic because we hoped his immune system would be able to fight the infection. My hesitancy was based upon the fact that antibiotics do not selectively kill the bacteria causing the illness, but also destroy beneficial bacteria that are part of the human biome.

Millions of women who have taken an antibiotic for an infection subsequently experience chronic vaginal yeast infections. This occurs because antibiotics such as tetracyclines, which are used to treat UTIs, intestinal tract infections, eye infections, sexually transmitted infections, acne, and gum disease, also kill the healthy bacteria of the human biome in the vagina. Since nature abhors a vacuum, yeast then overgrow where healthy bacteria used to predominate, thus allowing a vaginal infection (candidiasis) to occur (Spinillo et al., 1999)

In the case of my son, as it became clear that he was getting weaker and his immune system was not successfully clearing the infection, we followed his doctor’s advice and gave him the antibiotic. Magically, within two days he was better, and we continued with the course of antibiotics to clear his body of all the bacteria that was causing the pneumonia. Treatment is always a decision that involves balancing risk and benefit, getting sicker or getting well, given the possible negative side effects of the treatment. At the same time, it was possible that the antibiotic would not work since there was no time to run a lab test for that specific bacteria. If it had not worked, he would have needed another, different antibiotic, and if that had failed, a third drug.

Today, antibiotic resistance has grown into a worldwide crisis. The World Health Organization estimates that antimicrobial resistance directly caused 1.27 million deaths and contributed to another 5 million deaths globally in 2019. In the United States alone, the CDC reports over 2.8 million antibiotic-resistant infections occur every year, leading to at least 35,000 deaths and more than 3 million cases of infection by Clostridioides difficile (C. diff) occur (CDC, 2019).

Potentially fatal diseases that have become antibiotic resistant include Staphylococcus aureus (such as methicillin-resistant Staph aureus or MRSA) and Streptococcus pneumoniae (strep), as well as Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Escherichia coli, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. These six pathogens alone were responsible for nearly 1 million deaths in 2019. Other dangerous resistant infections include multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB), extensively drug-resistant typhoid fever, and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), sometimes described as “nightmare bacteria” (Murray, et al., 2022).

Bacterial resistance develops because bacteria, like all living organisms, evolve. Antibiotics, which are typically chemicals produced by molds or other organisms, work by killing or interfering with the life cycle of specific types of bacteria. However, antibiotics are often a blunt instrument: they resemble a form of what has been referred to as carpet bombing in warfare, in which the enemy is destroyed, but the whole neighborhood is also destroyed. While antibiotics may eliminate the bacteria causing the infection, they can also damage or destroy many beneficial bacteria in the gut, on the skin, and other areas of the body.

One in five medication-related visits to the emergency room are from reactions to antibiotics (CDC, 2025). This collateral damage can disrupt the gut microbiome, weaken immunity, and create opportunities for other harmful microbes to flourish. In addition, frequent antibiotic use could possibly contribute to obesity, as evidenced by the fact that low dosages of antibiotics are often given to farm animals, not only to prevent disease, but to increase their weight. Antibiotics appear to alter the gut microbiome to make it more efficient at extracting nutrients and energy from feed (Cox, 2016).

Antibiotics have been one of the major focuses of pharmaceutical drug development; however, they can cause serious side effects and tend to become less effective over time as the bacteria develop antibiotic resistance. Many bacteria can develop antibiotic resistance in less than a 6 month time period (Poku et al., 2023). Once bacteria develop antibiotic resistance to one drug, a new antibiotic drug needs to be discovered, developed, and produced. Even the newer and stronger antibiotics rapidly loose their efficacy as the bacteria develop resistance to it. In the long term, it is a loosing battle, and a totally new approach is needed.

Bacteriophage therapy

One new approach worth closer consideration is bacteriophage therapy. In nature, bacteria and viruses have been locked in a constant evolutionary battle for billions of years. Bacteria are vulnerable to specific viruses, so a bacteriophage, or phage, refers to a virus that specifically infects and kills a particular strain of bacteria. As bacteria change to evade attack, phages evolve to counter them, maintaining an ongoing balance to some degree. The theory is that because phages are very specific and only act on one particular type of bacteria, that potentially makes them a uniquely precise form of medicine.

The challenge involves matching the phage to the pathogenic bacterium, and there are an astonishing number of different phages and bacteria. In two patients with the same symptoms or diagnosis, the causal bacteria could be a slightly different subspecies. When used clinically, bacteriophages work only against specific type of bacterium. This makes phage therapy a useful form of individualized medicine.

To be successful, the bacteria that causes the patient’s infection must first be identified. This is different from the way in which antibiotics are commonly used in primary care. When a patient develops symptoms, often an antibiotic is given before the bacteria has been identified, and if it does not work, another antibiotic is given.

In contrast, phage therapy depends on matching the specific disease-causing bacteria to a specific phage. Phage medicine requires a library of thousands of known phages as an essential prerequisite to treatment. Clinical care involves identifying the phage that can target and destroy that specific bacterium. Then the phage is cultured, purified, and administered in either a liquid preparation, capsule, ointment, intravenously or at a wound site depending on the type of infection.

Unlike antibiotics, which often damage beneficial microbes, phages only target the bacteria they evolved to destroy, leaving the rest of the human biome intact. Because viruses are capable of reproduction, once a phage reaches its bacterial host, it multiplies rapidly and produces hundreds of new phages that continue to attack the specific disease-causing bacteria as shown in Figure 1. According to reports from phage medicine, symptoms improve dramatically within 24 hours. The phages are self-limiting and their numbers naturally decline once the infection is cleared.

Figure 1. Electron micrograph of a phage attaching and injecting it viral genome into the cell and its life cycle

At present, phage therapy has already shown success against a variety of resistant infections, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Acinetobacter baumannii wound infections (a major problem in military medicine), multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae, and even certain cases of tuberculosis. Instead of being the last line of defense, in the future this may become the first line of defense.

The initial research and clinical use has been concentrated in Russia and Eastern Europe. The United States largely abandoned phage therapy after the discovery of antibiotics. Several factors contributed to this trend.

- Funding barriers. Funding agencies in the West have not seen phage therapy as a credible option. In many cases, the review committees that decided which grant applications to approve have tended to fund research that supported their own biases and their interests in antibiotic research. As a result, research money was rarely allocated to study or develop phage therapies. Generally, high- risk, novel research ideas are almost never funded by federal agencies except DARPA which is more open to new concepts when they offer a high potential of success.

- Economic realities discourage investment. Unlike antibiotics, which can be mass-produced as a single chemical and sold at high volume for profit, phage therapy requires maintaining large, evolving phage libraries and tailoring treatments to each patient. This individualized model offered little appeal to large pharmaceutical companies seeking standardized products with a high payout.

- Development is not scalable. A specific bacteriophage must be selected for each specific pathogenic bacteria, and a large phage collection must be maintained to identify the correct phage.

- Scientific and cultural bias. American researchers have tended to dismiss work coming out of Russia and Georgia, failing to recognize the rigor and effectiveness of decades of phage therapy practiced there. Limited scientific exchange was also a factor during the Cold War. A similar bias, for example, has influenced the adoption of psychological treatment strategies developed in Russia. In the U.S., the focus was more on using instrumental learning while neglecting the power of Pavlov’s classical condition.

These scientific prejudices, financial disincentives, and geopolitical divides have meant that phage therapy was almost totally absent in Western medicine although it continued in Eastern Europe, where it has saved countless lives. Phage therapy is currently becoming recognized and desperately needed because of the increase in multi-drug-resistant infections.

Phage treatment challenges

The greatest challenge with phage therapy is that it must be individualized to the pathogen. Each patient’s infection may require a different phage, because phages are exquisitely specific to the bacterium they target. A phage that destroys one strain of E. coli, for example, may have no effect on another subspecies of E. coli. While the same phage can sometimes be used for multiple patients with the same infection, in most cases treatment must be customized to the individual patient.

This requires maintaining vast phage libraries that researchers and clinicians must be able to screen rapidly in order to find the right match. The scale of this challenge is staggering, although AI technology may be part of the solution. Scientists estimate that there are 10³¹ (ten million trillion trillion) specific phages on Earth, making them the most abundant biological entities known. Only a tiny fraction of these have been studied, and only a relatively smaller number are currently catalogued for medical use.

Specialized research institutes, particularly in Georgia, Poland, and Russia (and now in the U.S. and Europe) have developed large collections of phages that can be tested against samples of specific bacterium. Building, maintaining, and updating these libraries is labor-intensive and requires constant monitoring, since both bacteria and phages evolve. Phage therapy does not lend itself easily to large-scale commercialization. Nevertheless, phage therapy represents one of the most promising approaches to resistant infections.

Summary

Unlike antibiotics, which disrupt the human microbiome and can cause significant side effects, phages are naturally occurring, highly targeted, and generally well tolerated. Because they attack only a specific bacterium, without disturbing beneficial microbes, phages have the potential to be used not only as a treatment but also for prevention, helping to control bacterial populations before they cause disease. Harnessing this form of living medicine could mark an evolutionary shift in modern healthcare, offering a sustainable, balanced way to prevent and treat infections. Read the outstanding book by Lina Zeldovich, The Living Medicine: How a lifesaving cure was nearly lost and why it will rescue us when antibiotics fail.

References

admin. (2025, August 28). Special Episode: Lina Zeldovich & The Living Medicine. This Podcast Will Kill You. Accessed September 1, 2025. https://thispodcastwillkillyou.com/2025/08/28/special-episode-lina-zeldovich-the-living-medicine/

CDC. (2019). Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2019. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/antimicrobial-resistance/media/pdfs/2019-ar-threats-report-508.pdf

CDC. (2025). Do antibiotics have side effects. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC Accessed September 5, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/media/pdfs/Do-Antibiotics-Have-Side-Effects-508.pdf

Cox, L.M. (2016). Antibiotics shape microbiota and weight gain across the animal kingdom, Animal Frontiers, 6(3), 8–14. https://doi.org/10.2527/af.2016-0028

Garnett, C. (2019). Personal quest resurrects phage therapy in infection fight. NIH Record, LXXI(6). https://nihrecord.nih.gov/2019/03/22/personal-quest-resurrects-phage-therapy-infection-fight

Murray, C. J. L. et al. (2022). Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. The Lancet, 399(103250, 629 – 655. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02724-0

Poku, E., Cooper, K., Cantrell, A., Harnan, S., Sin, M.A., Zanuzdana, A., & Hoffmann, A. (2023). Systematic review of time lag between antibiotic use and rise of resistant pathogens among hospitalized adults in Europe. JAC Antimicrob Resist, 5(1), dlad001. https://doi.org/10.1093/jacamr/dlad001

Spinillo, A., Capuzzo, E., Acciano, S., De Santolo, A., & Zara, F. (1999). Effect of antibiotic use on the prevalence of symptomatic vulvovaginal candidiasis. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 180(1 Pt 1),14-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70141-9

Zeldovich, L. (2024). The Living Medicine: How a lifesaving cure was nearly lost and why it will rescue us when antibiotics fail. New York: St. Martin’s Press. https://www.amazon.com/Living-Medicine-Lifesaving-Lost_and-Antibiotics/dp/1250283388

*Created in part from the information in the book, The Living Medicine-How a lifesaving cure was nearly lost-and why it will rescue Us When Antibiotics Fail, by Linda Zeldovich and with the editorial help of ChatGPT5.

Exploring the pain-brain-breathing connection

Posted: August 30, 2025 Filed under: attention, behavior, Breathing/respiration, cognitive behavior therapy, education, emotions, healing, meditation, Pain/discomfort, placebo, self-healing, Uncategorized | Tags: deliberate harm Leave a commentIf you’re curious about how the mind and body interplay in shaping pain—or looking for real, actionable techniques grounded in research listen to this episode of the Heart Rate Variability Podcast, Matt Bennett interviews Dr. Erik Peper about his article and blogpost Pain – There Is Hope. The conversation takes listeners beyond the common perception of pain as merely a physical response. It is a balanced mix of scientific depth and real-life applications, especially valuable for anyone interested in self-healing, holistic health, or understanding mind-body medicine. Moreover, it explains how pain is shaped by posture, breathing, mindset, and emotional context. Finally, it provides practical strategies to shift the pain experience, offering an uplifting and science-backed blend of understanding and hope.

If you find this helpful, let me know! And feel free to share it with friends and post it on your social channels so more people can benefit.

Blogs that complement this interview

If you want to explore further, check out the companion blog posts I hve created to expand on the themes from this discussion. These blogs highlight practical strategies, scientific insights, and everyday applications.

Healing from the Inside Out: How Your Mind–Body Shapes Pain

Posted: June 9, 2025 Filed under: attention, behavior, Breathing/respiration, CBT, emotions, healing, health, mindfulness, Pain/discomfort, placebo, self-healing, Uncategorized | Tags: health, meditation, mental-health, mindfulness, Sufism, yoga 2 CommentsAdapted from Peper, E., Booiman, A. C., & Harvey, R. (2025). Pain-There is Hope. Biofeedback, 53(1), 1-9. http://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-53.01.16

Pain is more than a physical sensation—it’s shaped by our breath, thoughts, emotions, and beliefs. A striking example: a four-year-old received a vaccination with no pain, revealing the disconnect between what science knows about pain relief and what’s practiced.

The article highlights five key ways to reduce pain:

- Exhale during the painful moment – This activates the parasympathetic nervous system, calming the body. A yogi famously demonstrated this by pushing skewers through his tongue without bleeding or feeling pain.

- Create a sense of safety – Feeling secure can lessen pain and speed healing. Sufi mystics have shown this by pushing knives through their chest muscles without long-term damage, often healing rapidly.

- Distract the mind – Shifting focus can ease discomfort.

- Reduce anticipation – Fear of pain often amplifies it.

- Explore the personal meaning of pain – Understanding what pain symbolizes can shift how we experience it.

The blog also explores how the body regulates pain through mechanisms which influence inflammation and pain signals. In the end, hope, trust, and acceptance, along with mindful breathing, healing imagery, and meaningful engagement, emerge as powerful tools not just to reduce pain—but to promote true healing.

Listen to the AI generated podcast created from this article by Google NotebookLM

I took my four-year-old daughter to the pediatrician for a vaccination. As the nurse prepared to administer the shot in her upper arm. I instructed my daughter to exhale while breathing, understanding that this technique could influence her perception of pain. Despite my efforts, my daughter did not follow my instructions. At that point, the nurse interjected and said, “Please sit in front of your daughter.” Then turned to my daughter and said, “Do you see your father’s curly hair? Do you think you could blow the curls to move them back and forth?” My daughter thought this playful game was fun! As she blew at my hair, the curls moved back and forth while the nurse administered the injection. My daughter was unaware that she had received the shot and felt no pain.

My experience as a father and as a biofeedback practitioner was enlightening–it demonstrated the difference between theoretical knowledge of breathing techniques associated with pain perception and practical applications of clinical skills used by a pediatric nurse practitioner while administering an injection with children. An obvious question raised is: What processes are involved in the perception of pain?

There are many factors influencing pain perception, such as physical/physiological, behavioral and psychological/emotional factors related to the injection as described by St Clair-Jones et al., (2020). Physical and physiological considerations include device type such as needle gauge size as well as formulation volume and ingredients (e.g., adjuvants, pH, buffers), fluid viscosity, temperature, as well as possible sensitivity to coincidental exposures associated with an injection (e.g., sensitivity to latex exam gloves or some other irritant in the injection room).

There are overlapping physical and behavioral-related moderators that include weight and body fat composition, proclivity towards movements (e.g., activity level or ‘squirminess’), as well as co-morbid factors such as whether the person has body sensitization due to rheumatoid arthritis and/or fibromyalgia, for example. Other behavioral factors include a clinician selecting the injection site, along with the angle, speed or duration of injection. Psychological influences center around patient expectations including injection-anxiety or needle phobia, pain catastrophizing, as well as any nocebo effects such as white-coat hypertension.

Although the physical, behavioral and psychological categories allow for considering many physical and physiological factors (e.g., product-related factors), behavioral factors (e.g., injection-related behaviors) and psychological factors (e.g., person-related psychological attitudes, beliefs, cognitions and emotions), this article focuses on a figurative recipe for success associated with benefits of simple breathing to reduce pain perceptions.

Of the many categories of consideration related to pain perceptions, following are five key ‘recipe ingredients’ that contributed to a relatively painless experience:

- Exhaling During Painful Stimuli: Exhaling during a painful stimulus can activate parts of the parasympathetic nervous system leading to promotion of self-healing.

- Creating a Sense of Safety: Ensuring that the child feels safe and secure is crucial in managing pain. My lack of worry and concern and the nurse’s gentle and engaging approach created a comforting environment for my daughter.

- Using Distraction: Distraction techniques, such as focusing on the movement of the curls of the hair served to redirect my daughter’s attention away from the anticipated pain.

- Reducing Anticipation of Pain: My daughter’s previous visits were always enjoyable and as a parent, I was not anxious and was looking forward to the pediatrician visit and their helpful advice.

- Understanding the Personal Meaning of Pain: The approach taken by the nurse allowed the injection to be perceived as a non-event, thereby minimizing the psychological impact of the pain.

Exhaling During Painful Stimuli

Exhaling during painful stimuli facilitates a reduction in discomfort through several physiological mechanisms. During exhalation the parasympathetic nervous system is activated, which slows the heart rate and promotes relaxation, regeneration, reduces anxiety, and may counteract the effects of pain (Magnon et al., 2021). Breathing moderation of discomfort is observable through heart rate variability associated with slow, resonant breathing patterns, where heart rate increases with inhalation and decreases with exhalation (Lehrer & Gevirtz, 2014; Steffen et al., 2017). Physiological studies show that slow, resonant breathing at approximately six breaths per minute for adults, and a little faster for young children, causes the heart rate to increase during inhalation and decrease during exhalation, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Changes in heart rate as modulated by slower breathing at about six breaths per minute

One can experience how breathing affects discomfort when taking a cold shower under two conditions: As the cold water hits your skin: (1) gasping and holding your breath versus (2) exhaling slowly as the cold water hits you. Most people will report that slowly exhaling feels less uncomfortable, though they may still prefer a warm shower.

An Exercise for Use During Medical Procedures: Paring the procedure with inhalation and exhalation

A simple breathing technique can be used to reduce the experience of pain during a procedure or treatment, or during uncomfortable movement post-injury or post-surgery. Physiologically, inhalation tends to increase heart rate and sympathetic activation while exhalation reduces heart rate and increases parasympathetic activity. Often inhalation increases tension in the body, while during exhalation, one tends to relax and let go. The goal is to have the patient practice longer and slower breathing so that a procedure that might be uncomfortable is initiated during the exhalation phase. Applications of long, slow breathing techniques include having blood drawn, insertion of acupuncture needles in tender points, or movement that causes discomfort or pain. Slowly breathing is helpful in reducing many kinds of discomfort and pain perceptions (Joseph et al., 2022; Jafari et al., 2020).

Implementing the technique of exhaling during painful experiences can be deceptively simple yet challenging. When initially practicing this technique, the participants often try too hard by quickly inhaling and exhaling as the pain stimulus occurs. The effective technique involves allowing the abdomen to expand while inhaling, then allowing exhaled air to flow out while simultaneously relaxing the body and smiling slightly, and initiating the painful procedure only after about 25 percent of the air is exhaled.

Some physiological mechanisms that explain how slow breathing influences on pain perceptions have focused on baroreceptors that are mechanically sensitive to pressure and breathing dynamics. According to Suarez-Roca et al. (2021, p 29): “Several physiological factors moderate the magnitude and the direction of baroreceptor modulation of pain perception, including: (a) resting systolic and diastolic AP, (b) pain modality and dimension, (c) type of activated vagal afferent, and (d) the presence of a chronic pain condition It supports the parasympathetic activity that exert an anti-inflammatory influence, whereas the sympathetic activity is mostly pro-inflammatory. Although there are complex physiological interactions between cardiorespiratory systems, arterial pressure and baroreceptor sensitivity that influence pain perceptions, this report focuses on simpler reminders, such as creating a sense of safety for people as a result of better breathing techniques.

Creating a Sense of Safety

My young daughter did not know what to expect and totally trusted me and I was relaxed because the purpose was to enhance my daughter’s future health by giving her a vaccination to prevent being sick at a future time. Often, a parent’s anxiety is contagious to the child since expectations and emotional states influence the experience of medical procedures and pain (Sullivan et al., 2021). For my daughter, the nurse’s calm and confident demeanor contributed to a safe and reassuring environment. As a result, she was more engaged in a playful distraction, blowing at my hair, rather than focusing on the impending shot. This observation underscores an important psychological principle: when individuals do not anticipate pain and feel safe, they are more likely to experience surprise rather than distress. Conversely, anticipation of pain can amplify the perception of discomfort.

For instance, many people have experienced heightened anxiety at the dentist, where they may feel the pain of the needle before it is inserted. Anticipation evocates a past memory of pain that triggers a defensive reaction, increasing sympathetic arousal and sharpening awareness of potential danger. By providing the experience of feeling of safety, parents, caretakers, and medical professionals can play a crucial role in reducing the perceived pain of medical interventions.

Using Distraction

It is inherently difficult to attend to two tasks simultaneously; thus, focusing one’s attention on one task often diminishes awareness of pain and other stimuli (Rischer et al., 2020). For instance, when the nurse asked my daughter to see if she could blow hard enough to make the curls move back and forth, this task captured her attention in a fun and multisensory way. She was engaged visually by the movement of the curls, audibly by the sound of the rushing air, physically by the act of exhalation, and cognitively by following the instructions. Additionally, her success in moving the curls reinforced the activity as a positive and enjoyable experience.

In contrast, it is challenging to allow oneself to be distracted when anticipating discomfort, as numerous cues can continuously refocus attention on the procedure that may induce pain. This experience is akin to attempting to tickle oneself, which typically fails to elicit laughter due to the predictability and lack of external stimulation. Most of us have experienced how challenging it is to be self-directive and not focus on the sensations during dental procedures as discussed in the overview of music therapy for use in dentistry by Bradt and Teague (2018). The challenges are illustrated by my own experience during a dental cleaning

During a dental cleaning, I often attempt to distract myself by mentally visualizing the sensation of breathing down my legs while repeating an internal mantra or evoking joyful memories. Despite these efforts, I frequently find myself attending to the sound of the ultrasonic probe and the sensations in my mouth. To manage this distraction more effectively, I have found that external interventions such as listening to music or an engaging audio story through earphones is more beneficial.

From this perspective, we wished that the dentist could implement an external intervention by collaborating with a massage therapist to provide a simultaneous foot massage during the teeth cleaning. This dual stimulation would offer enough competing sensations to divert attention from the dental procedure to the comfort of the foot massage.

Reducing Anticipation of Pain

A crucial factor in the experience of pain is the anticipation and expectation of discomfort, which is often shaped by previous experiences (Henderson et al., 2020; Reicherts et al., 2017). When encountering a novel experience, we might interpret the sensations as novel rather than painful. Similar phenomena can be observed in young children when they fall or get hurt on the playground. They may initially react with surprise or shock and may look for their caretaker. Depending the reaction of their caregiver, they may begin to cry or they might cry briefly, stop and resume playing.