TechStress: Building Healthier Computer Habits

Posted: August 30, 2023 Filed under: ADHD, behavior, biofeedback, Breathing/respiration, cognitive behavior therapy, computer, digital devices, education, emotions, ergonomics, Evolutionary perspective, Exercise/movement, health, laptops, Neck and shoulder discomfort, Pain/discomfort, posture, screen fatigue, stress management, Uncategorized, vision, zoom fatigue | Tags: cellphone, fatigue, gaming, mobile devices, screens 2 CommentsBy Erik Peper, PhD, BCB, Richard Harvey, PhD, and Nancy Faass, MSW, MPH

Adapted by the Well Being Journal, 32(4), 30-35. from the book, TechStress: How Technology is Hijacking Our Lives, Strategies for Coping, and Pragmatic Ergonomics by Erik Peper, Richard Harvey, and Nancy Faass.

Every year, millions of office workers in the United States develop occupational injuries from poor computer habits—from carpal tunnel syndrome and tension headaches to repetitive strain injury, such as “mouse shoulder.” You’d think that an office job would be safer than factory work, but the truth is that many of these conditions are associated with a deskbound workstyle.

Back problems are not simply an issue for workers doing physical labor. Currently, the people at greatest risk of injury are those with a desk job earning over $70,000 annually. Globally, computer-related disorders continue to be on the rise. These conditions can affect people of all ages who spend long hours at a computer and digital devices.

In a large survey of high school students, eighty-five percent experienced tension or pain in their neck, shoulders, back, or wrists after working at the computer. We’re just not designed to sit at a computer all day.

Field of Ergonomics

For the past twenty years, teams of researchers all over the world have been evaluating workplace stress and computer injuries—and how to prevent them. As researchers in the fields of holistic health and ergonomics, we observe how people interact with technology. What makes our work unique is that we assess employees not only by interviewing them and observing behaviors, but also by monitoring physical responses.

Specifically, we measure muscle tension and breathing, in the moment, in real-time, while they work. To record shoulder pain, for example, we place small sensors over different muscles and painlessly measure the muscle tension using an EMG (electromyograph)—a device that is employed by physicians, physical therapists, and researchers. Using this device, we can also keep a record of their responses and compare their reactions over time to determine progress.

What we’ve learned is that people get into trouble if their muscles are held in tension for too long. Working at a computer, especially at a stationary desk, most people maintain low-level chronic tension for much of the day. Shallow, rapid breathing is also typical of fine motor tasks that require concentration, like data entry.

Muscle tension and breathing rate usually increase during data entry or typing without our awareness.

When these patterns are paired with psychological pressure due to office politics or job insecurity, the level of tension and the risk of fatigue, inflammation, pain, or injury increase. In most cases, people are totally unaware of the role that tension plays in injury. Of note, the absolute level of tension does not predict injury—rather, it is the absence of periodic rest breaks throughout the day that seems to correlate with future injuries.

Restbreaks

All of life is the alternation between movement and rest, inhaling and exhaling, sleeping and waking. Performing alternating tasks or different types of activities and movement is one way to interrupt the couch potato syndrome—honoring our evolutionary background.

Our research has confirmed what others have observed: that it’s important to be physically active, at least periodically, throughout the day. Alternating activity and rest recreate the pattern of our ancestors’ daily lives. When we alternate sedentary tasks with physical activity, and follow work with relaxation, we function much more efficiently. In short, move your body more.

Better Computer Habits: Alternate Periods of Rest and Activity

As mentioned earlier, our workstyle puts us out of sync with our genetic heritage. Whether hunting and gathering or building and harvesting, our ancestors alternated periods of inactivity with physical tasks that required walking, running, jumping, climbing, digging, lifting, and carrying, to name a few activities. In contrast, today many of us have a workstyle that is so immobile we may not even leave our desk for lunch.

As health researchers, we have had the chance to study workstyles all over the world. Back pain and strain injuries now affect a large proportion of office workers in the US and in high-tech firms worldwide. The vast majority of these jobs are sedentary, so one focus of the research is on how to achieve a more balanced way of working.

A recent study on exercise looked at blood flow to the brain. Researchers Carter and colleagues found that if people sit for four hours on the job, there’s a significant decrease in blood flow to the brain. However, if every thirty or forty minutes they get up and move around for just two minutes, then brain blood flow remains steady. The more often you interrupt sitting with movement, the better.

It may seem obvious that to stay healthy, it’s important to take breaks and be physically active from time to time throughout the day. Alternating activity and rest recreate the pattern of our ancestors’ daily lives. The goal is to alternate sedentary tasks with physical activity and follow work with relaxation. When we keep this type of balance going, most people find that they have more energy, are more productive, and can be more effective.

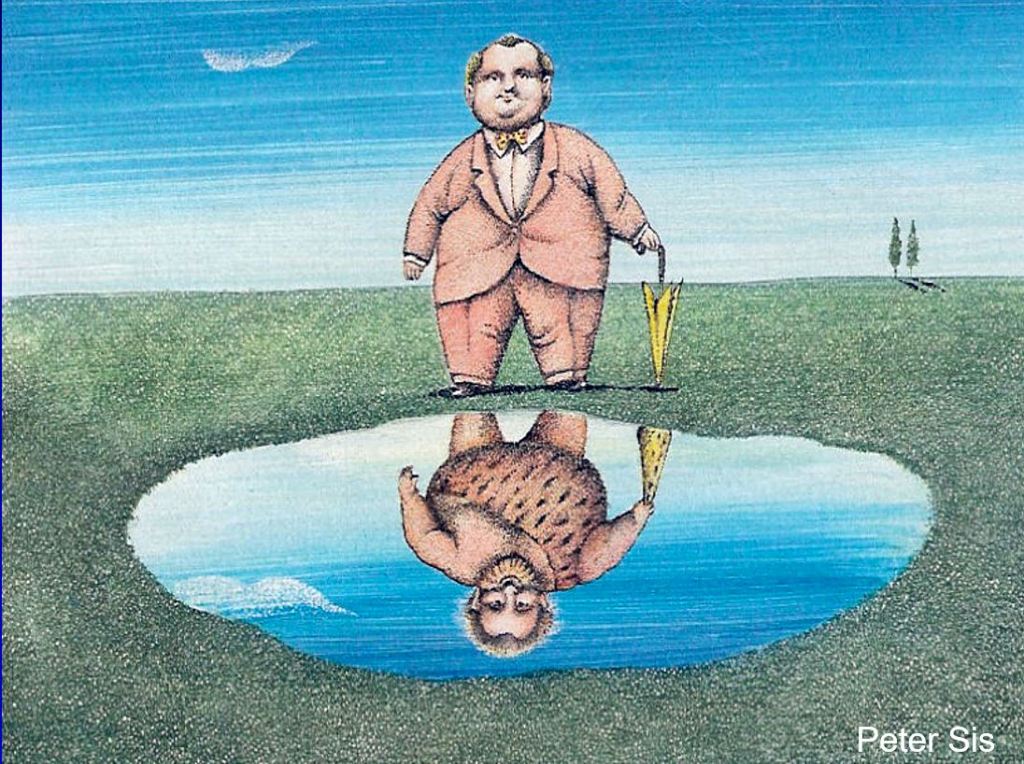

Genetics: We’re Hardwired Like Ancient Hunters

Despite a modern appearance, we carry the genes of our forebearers—for better and for worse. (Art courtesy of Peter Sis). Reproduced from Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Faass (2020). TechStress: How Technology is Hijacking Our Lives, Strategies for Coping, and Pragmatic Ergonomics. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books.

In the modern workplace, most of us find ourselves working indoors, in small office spaces, often sitting at a computer for hours at a time. In fact, the average Westerner spends more than nine hours per day sitting indoors, yet we’re still genetically programmed to be physically active and spend time outside in the sunlight most of the day, like the nomadic hunters and gatherers of forty thousand years ago.

Undeniably, we inherently conserve energy in order to heal and regenerate. This aspect of our genetic makeup also helps burn fewer calories when food is scarce. Hence the propensity for lack of movement and sedentary lifestyle (sitting disease).

In times of famine, the habit of sitting was essential because it reduced calorie expenditure, so it enabled our ancestors to survive. In a prehistoric world with a limited food supply, less movement meant fewer calories burned. Early humans became active when they needed to search for food or shelter. Today, in a world where food and shelter are abundant for most Westerners, there is no intrinsic drive to initiate movement.

It is also true that we have survived as a species by staying active. Chronic sitting is the opposite of our evolutionary pattern in which our ancestors alternated frequent movement while hunting or gathering food with periods of rest. Whether they were hunters or farmers, movement has always been an integral aspect of daily life. In contrast, working at the computer—maintaining static posture for hours on end—can increase fatigue, muscle tension, back strain, and poor circulation, putting us at risk of injury.

Quit a Sedentary Workstyle

Almost everyone is surprised by how quickly tension can build up in a muscle, and how painful it can become. For example, we tend to hover our hands over the keyboard without providing a chance for them to relax. Similarly, we may tighten some of the big muscles of our body, such as bracing or crossing our legs.

What’s needed is a chance to move a little every few minutes—we can achieve this right where we sit by developing the habit of microbreaks. Without regular movement, our muscles can become stiff and uncomfortable. When we don’t take breaks from static muscle tension, our muscles don’t have a chance to regenerate and circulate oxygen and necessary nutrients.

Build a variety of breaks into your workday:

- Vary work tasks

- Take microbreaks (brief breaks of less than thirty seconds)

- Take one-minute stretch breaks

- Fit in a moving break

Varying Work Tasks

You can boost physical activity at work by intentionally leaving your phone on the other side of the desk, situating the printer across the room, or using a sit-stand desk for part of the day. Even a few minutes away from the desk makes a difference, whether you are hand delivering documents, taking the long way to the bathroom, or pacing the room while on a call.

When you alternate the types of tasks and movement you do, using a different set of muscles, this interrupts the contractions of muscle fibers and allows them to relax and regenerate. Try any of these strategies:

- Alternate computer work with other activities, such as offering to do a coffee run

- Schedule walking meetings with coworkers

- Vary keyboarding and hand movements

Ultimately, vary your activities and movements as much as possible. By changing your posture and making sure you move, you’ll find that your circulation and your energy improve, and you’ll experience fewer aches and pains. In a short time, it usually becomes second nature to vary your activities throughout the day.

Experience It: “Mouse Shoulder” Test

You can test this simple mousing exercise at the computer or as a simulation. If you’re at the computer, sit erect with your hand on the mouse next to the keyboard. To simulate the exercise, sit with erect posture as if you were in front of your computer and hold a small object you can use to imitate mousing.

With the mouse (or a sham mouse), simulate drawing the letters of your name and your street address, right to left. Be sure each letter is very small (less than half an inch in height). After drawing each letter, click the mouse.

As part of the exercise, draw the letters and numbers as quickly as possible for ten to fifteen seconds. What did you observe? In almost all cases, you may note that you tightened your mousing shoulder and your neck, stiffened your trunk, and held your breath. All this occurred without awareness while performing the task. Over time, this type of muscle tension can contribute to discomfort, soreness, pain, or eventual injury.

Microbreaks

If you’ve developed an injury—or have chronic aches and pains—you’ll probably find split-second microbreaks invaluable. A microbreak means taking brief periods of time that last just a few seconds to relax the tension in your wrists, shoulders, and neck.

For example, when typing, simply letting your wrists drop to your lap for a few seconds will allow the circulation to return fully to help regenerate the muscles. The goal is to develop a habit that is part of your routine and becomes automatic, like driving a car. To make the habit of microbreaks practical, think about how you can build the breaks into your workstyle. That could mean a brief pause after you’ve completed a task, entered a column of data, or before starting typing out an assignment.

For frequent microbreaks, you don’t even need to get up—just drop your hands in your lap or shake them out, move your shoulders, and then resume work. Any type of shaking or wiggling movement is good for your circulation and kind of fun.

In general, a microbreak may be defined as lasting one to thirty seconds. A minibreak may last roughly thirty seconds to a few minutes, and longer large-movement breaks are usually greater than a few minutes. Popular microbreaks:

- Take a few deep breaths

- Pause to take a sip of water

- Rest your hands in your lap

- Stretch

- Let your arms drop to your sides

- Shake out your hands (wrists and fingers)

- Perform a quick shoulder or neck roll

Often, we don’t realize how much tension we’ve been carrying until we become more mindful of it. We can raise our awareness of excess tension—this is a learned skill—and train ourselves to let go of excess muscle tension. As we increase our awareness, we’re able to develop a new, more dynamic workstyle that better fits our goals and schedule.

One-Minute Stretch Breaks

We all benefit from a brief break, even with the best of posture (left). One approach is to totally release your muscles (middle). That release can be paired with a series of brief stretches (right). Reproduced from Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Faass (2020). TechStress: How Technology is Hijacking Our Lives, Strategies for Coping, and Pragmatic Ergonomics. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books.

The typical mini-stretch break lasts from thirty seconds to a few minutes, and ideally you want to take them several times per hour. Similar to microbreaks, mini-stretch breaks are especially important for people with an injury or those at risk of injury. Taking breaks is vital, especially if you have symptoms related to computer stress or whenever you’re working long hours at a sedentary job. To take a stretch break:

Begin with a big stretch, for example, by reaching high over your head then drop your hands in your lap or to your sides.

Look away from the monitor, staring at near and far objects, and blink several times. Straighten your back and stretch your entire backbone by lifting your head and neck gently, as if there were an invisible string attached to the crown of your head.

Stretch your mind and body. Sitting with your back straight and both feet flat on the floor, close your eyes and listen to the sounds around you, including the fan on the computer, footsteps in the hallway, or the sounds in the street.

Breathe in and out over ten seconds (breathe in for four or five seconds and breathe out for five or six seconds), making the exhale slightly longer than the inhale. Feel your jaw, mouth, and tongue muscles relax. Feel the back and bottom of the chair as your body breathes all around you. Envision someone in your mind’s eye who is kind and reassuring, who makes you feel safe and loved, and who can bring a smile to your face inwardly or outwardly.

Do a wiggling movement. When you take a one-minute break, wiggling exercises are fast and easy, and especially good for muscle tension or wrist pain. Wiggle all over—it feels good, and it’s also a great way to improve circulation.

Building Exercise and Movement into Every Day

Studies show that you get more benefit from exercising ten to twenty minutes, three times a day, than from exercising for thirty to sixty minutes once a day. The implication is that doing physical activities for even a few minutes can make a big difference.

Dunstan and colleagues have found that standing up three times an hour and then walking for just two minutes reduced blood sugar and insulin spikes by twenty-five percent.Fit in a Moving Break

Fit in a Moving Break

Once we become conscious of muscle tension, we may be able to reverse it simply by stepping away from the desk for a few minutes, and also by taking brief breaks more often. Explore ways to walk in the morning, during lunch break, or right after work. Ideally, you also want to get up and move around for about five minutes every hour.

Ultimately, research makes it clear that intermittent movement, such as brief, frequent stretching throughout the day or using the stairs rather than elevator, is more beneficial than cramming in a couple of hours at the gym on the weekend. This explains why small changes can have a big impact—it’s simply a matter of reminding yourself that it’s worth the effort.

Workstation Tips

Your ability to see the display and read the screen is key to reducing neck and eye strain. Here are a few strategic factors to remember:

Monitor height: Adjust the height of your monitor so the top is at eyebrow level, so you can look straight ahead at the screen.

Keyboard height: The keyboard height should be set so that your upper arms hang straight down while your elbows are bent at a 90-degree angle (like the letter L) with your forearms and wrists held horizontally.

Typeface and font size: For email, word processing, or web content, consider using a sans serif typeface. Fonts that have fewer curved lines and flourishes (serifs) tend to be more readable on screen.

Checking your vision: Many adults benefit from computer glasses to see the screen more clearly. Generally, we do not recommend reading glasses, bifocals, trifocals, and progressive lenses as they tend to allow clear vision at only one focal length. To see through the near-distance correction of the lens requires you to tilt your head back. Although progressive lenses allow you to see both close up and at a distance, the segment of the lens for each focal length is usually too narrow for working at the computer.

Wearing progressive lenses requires you to hold your head in a fixed position to be in focus. Yet you may be totally unaware that you are adapting your eye and head movements to sustain your focus. When that is the case, most people find that special computer glasses are a good solution.

Consider computer glasses if you must either bring your nose to the screen to read the text, wear reading glasses and find that their focal length is inappropriate for the monitor distance, wear bi- or trifocal glasses, or are older than forty.

Computer glasses correct for the appropriate focal distance to the computer. Typically, monitor distance is about twenty-three to twenty-eight inches, whereas reading glasses correct for a focal length of about fifteen inches. To determine your individual, specific focal length, ask a coworker to measure the distance from the monitor to your eyes. Provide this personal focal distance at the eye exam with your optometrist or ophthalmologist and request that your computer glasses be optimized for that distance.

Remembering to blink: As we focus on the screen, our blinking rate is significantly reduced. Develop the habit of blinking periodically: at the end of a paragraph, for example, or when sending an email.

Resting your eyes: Throughout the day, pause and focus on the far distance to relax your eyes. When looking at the screen, your eyes converge, which can cause eyestrain. Each time you look away and refocus, that allows your eyes to relax. It’s especially soothing to look at green objects such as a tree that can be seen through a window.

Minimizing glare: If the room is lit with artificial light, there may be glare from your light source if the light is right in front of you or right behind you, causing reflection on your screen. Reflection problems are minimized when light sources are at a 90-degree angle to the monitor (with the light coming from the side). The worst situations occur when the light source is either behind or in front of you.

An easy test is to turn off your monitor and look for reflections on the screen. Everything that you see on the monitor when it’s turned off is there when you’re working at the monitor. If there are bright reflections, they will interfere with your vision. Once you’ve identified the source of the glare, change the location of the reflected objects or light sources, or change the location of the monitor.

Contrast: Adjust the light contrast in the room so that it is neither too bright nor too dark. If the room is dark, turn on the lights. If it is too bright, close the blinds or turn off the lights. It is exhausting for your eyes to have to adapt from bright outdoor light to the lighting of your computer screen. You want the light intensity of the screen to be somewhat similar to that in the room where you’re working. You also do not want to look from your screen to a window lit by intense sunlight.

Don’t look down at phone: According to Kenneth Hansraj, MD, chief of spine surgery at New York Spine Surgery and Rehabilitation Medicine, pressure on the spine increases from about ten pounds when you are holding your head erect, to sixty pounds of pressure when you are looking down. Bending forward to look at your phone, your head moves out of the line of gravity and is no longer balanced above your neck and spine. As the angle of the face-forward position increases, this intensifies strain on the neck muscles, nerves, and bones (the vertebrae).

The more you bend your neck, the greater the stress since the muscles must stretch farther and work harder to hold your head up against gravity. This same collapsed head-forward position when you are seated and using the phone repeats the neck and shoulder strain. Muscle strain, tension headaches, or neck pain can result from awkward posture with texting, craning over a tablet (sometimes referred to as the iPad neck), or spending long hours on a laptop.

A face-forward position puts as much as sixty pounds of pressure on the neck muscles and spine.

Repetitive strain of neck vertebrae (the cervical spine), in combination with poor posture, can trigger a neuromuscular syndrome sometimes diagnosed as thoracic outlet syndrome. According to researchers Sharan and colleagues, this syndrome can also result in chronic neck pain, depression, and anxiety.

When you notice negative changes in your mood or energy, or tension in your neck and shoulders, use that as a cue to arch your back and look upward. Think of a positive memory, take a mindful breath, wiggle, or shake out your shoulders if you’d like, and return to the task at hand.

Strengthen your core: If you find it difficult to maintain good posture, you may need to strengthen your core muscles. Fitness and sports that are beneficial for core strength include walking, sprinting, yoga, plank, swimming, and rowing. The most effective way to strengthen your core is through activities that you enjoy.

Final Thoughts

If these ideas resonate with you, consider lifestyle as the first step. We need to build dynamic physical activity into our lives, as well as the lives of our children. Being outside is usually an uplift, so choose to move your body in natural settings whenever possible, whatever form that takes. Being outside is the factor that adds an energetic dimension. Finally, share what you learn, and help others learn and grow from your experiences.

If you spend time in front of a computeror using a mobile device, read the book, TechStress: How Technology is Hijacking Our Lives, Strategies for Coping, and Pragmatic Ergonomics. It provides practical, easy-to-use solutions for combating the stress and pain many of us experience due to technology use and overuse. The book offers extremely helpful tips for ergonomic use of technology, it

goes way beyond that, offering simple suggestions for improving muscle health that seem obvious once you read them, but would not have thought of yourself: “Why didn’t I think of that?” You will learn about the connection between posture and mood, reasons for and importance of movement breaks, specific movements you can easily perform at your desk, as well as healthier ways to utilize technology in your everyday life.

Additional resources

“Don’t slouch!” Improve health with posture feedback

Posted: July 1, 2019 Filed under: behavior, digital devices, ergonomics, health, Neck and shoulder discomfort, posture, self-healing, Uncategorized | Tags: cellphone, eye strain, Laptop 3 Comments“Although I knew I slouched and often corrected myself, I never realized how often and how long I slouched until the vibratory posture feedback from the UpRight Go 2™ cued me to sit up (see Figure 1).” -Erik Peper

Figure 1. Wearing an UpRight Go 2™ to increase awareness of slouching and as a reminder to change position.

Figure 1. Wearing an UpRight Go 2™ to increase awareness of slouching and as a reminder to change position.

For thousands of years we sat and stood erect. In those earlier times, we looked down to identify specific plants or animal track and then looked up and around to search for possible food sources, identify friends, and avoid predators. The upright, not slouched posture body posture, is innate and optimizes body movement as illustrated in Figure 2 (for more information, see Gokhale, 2013).

Figure 2. The normal aligned spine of a toddler and the aligned posture of a man carrying a heavy load.

Figure 2. The normal aligned spine of a toddler and the aligned posture of a man carrying a heavy load.

Being tall and erect allows the head to freely rotate. Head rotation is reduced when we look down at our cell phones, tablets or laptops (Harvey, Peper, Booiman, Heredia Cedillo, & Villagomez, 2018). Our digital world captures us as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Captured by the screen with a head forward positions.

Figure 3. Captured by the screen with a head forward positions.

Looking down and focusing on the screen for long time periods is the opposite of what supported us to survive and thrive when we lived as hunters and gatherers. When we look down, we become more oblivious to our surroundings and unaware of the possible predators that would have been hunting us for food.

This slouched position increases back, neck, head and eye tension as well as affecting respiration and digestion (Devi, Lakshmi, & Devi, 2018; Peper, Lin, & Harvey, 2017). After looking at the screens for a long time, we may feel tired or exhausted and lack initiative to do something else. Our mood may turn more negative since it is easier to evoke hopeless, helpless and powerless thoughts and memories when looking down than when looking up (Wilson, & Peper, 2004; Peper, Lin, Harvey, & Perez, 2017). In the down position, our brain has to work harder to evoke positive thoughts and memories or perform cognitive tasks as compared to when the head is erect (Tsai, Peper, & Lin, 2016; Peper, Harvey, Mason, & Lin, 2018). By looking down and focusing at the screen, our eyes may begin to strain. To be able to see objects near us, the extraocular muscles of the eyes contract to converge the eyes and the cilia muscles around the lens contract to increase the curvature of the lens so that the reading material is in focus.

Become aware how nearby vision increases eye strain.

Hold your arm straight ahead of you at eye level with your thumb up. While focusing on your thumb, slowly bring your thumb closer and closer to your nose. Observe the increase in eyestrain as you bring your thumb closer to your nose.

Eyestrain tends to develop when we do not relax the eyes by periodically looking away from the screen. When we look at the horizon or trees in the far distance the ciliary muscles and the extraocular muscles relax (Schneider, 2016).

Head forward posture increases neck and back tension

When we look down and concentrate, our head moves significantly forward. The neck and back muscles have to work much harder to hold the head up when the neck is in this flexed position. As Dr. Kenneth Hansraj, Chief of Spine Surgery New York Spine Surgery & Rehabilitation Medicine reported, “The weight seen by the spine dramatically increases when flexing the head forward at varying degrees. An adult head weighs 10-12 pounds in the neutral position. As the head tilts forward the forces seen by the neck surges to 27 pounds at 15 degrees, 40 pounds at 30 degrees, 49 pounds at 45 degrees and 60 pounds at 60 degrees.” (Hansraj, 2014). Our head tends to tilt down when we look at the text, videos, emails, photos, or games and stay in this position for long time periods. We are captured by the digital display and are unaware of our tight overused neck and back muscles. Straightening up so that the back of the head is re-positioned over the spine and looking into the distance may help relax those muscles.

To reduce discomfort caused by slouching, we need to reintegrate our prehistoric life style pattern of alternating between looking down to being tall and looking at the distant scenery or across the room. The first step is awareness of knowing when slouching begins. Yet, we tend to be unaware until we experience discomfort or are reminded by others (e.g, “Don’t slouch! Sit up straight!”). If we could have immediate posture feedback when we begin to slouch, our awareness would increase and remind us to change our posture.

Posture feedback with UpRight Go

Simple posture feedback device such as an UpRight Go 2™ can provide vibratory feedback each time slouching starts as the neck as the head goes forward. The wearable feedback device consists of a small sensor that is attached to the back of the neck or back (see Figure 1). After being paired with a cellphone and calibrated for the upright position, the software algorithm detects changes in tilt and provides vibratory feedback each time the neck/back tilts forward.

In our initial exploration, employees, students and clients used the UpRight feedback devices at work, at school, at home, while driving, walking and other activities to identify situations that caused them to slouch. The most common triggers were:

- Ergonomic caused movement such as bring the head closer to the screen or looking down at their cell phone (for suggestions to improve ergonomics see recommendations at the end of the article)

- Tiredness

- Negative self-critical/depressive thoughts

- Crossing the legs protectively, shallow breathing, and other factors

After having identified some of the factors that were associated with slouching, we compared the health outcome of students who used the device for a minimum for 15 minutes a day for four weeks as compared to a control group who did not use the device. The students who received the UpRight feedback were also encouraged to use the feedback to change their posture and behavior and implemented some of the following strategies.

- Head down when looking at their laptop, tablet or cellphone.

- Change the ergonomics such as using a laptop stand and an external keyboard so that they could be upright while looking at the screen.

- Take many movement breaks to interrupt the static tension.

- Feeling tired.

- Take a break or nap to regenerate.

- Do fun physical activity especially activities where you look upward to re-energize.

- Negative self-critical, powerless, self-critical and depressive thoughts and feelings.

- Reframe internal language to empowering thoughts.

- Change posture by wiggling and looking up to have a different point of view.

- Crossing the legs.

- Sit in power position and breathe diaphragmatically.

- Get up and do a few movements such as shoulder rolls, skipping, or arm swings.

- Other causes.

- Identify the trigger and explore strategies so that you can sit erect without effort.

- Wiggle, move and get up to interrupt static muscle tension.

- Stand up and look out of the window and the far distance while breathing slowly

Posture feedback improves health

After four weeks of using the feedback device and changing behavior, the treatment group reported significant improvements in physical and mental health as shown in Figure 4 & 5.

Figure 4. Using the posture feedback significantly improved the Physical Health and Mental Health Composite Scores for the treatment group as compared to the control group (reproduced from Mason, L., Joy, Peper, & Harvey, 2018).

Figure 5. Pre to post changes after using posture feedback (reproduced from Colombo, Joy, Mason, L., Peper, Harvey, & Booiman, 2017).

Summary

Slouched posture and head forward and down position usually occurs without awareness and often results in long-term discomfort. We recommend that practitioners integrate wearable biofeedback devices to facilitate home practice especially for people with neck, shoulder, back and eye discomfort as well as for those with low energy and depression (Mason et al., 2018). We observed that a small wearable posture feedback device helped participants improve posture and decreased symptoms. The vibratory posture feedback provided the person with the opportunity to identify the triggers associated with slouching and the option to change their posture, behavior and environment.

As one participant reported, “I have been using the Upright device for a few weeks now. I mostly use the device while studying at my desk and during class. I have found that it helps me stay focused at my desk for longer time. Knowing there is something monitoring my posture helps to keep me sitting longer because I want to see how long I can keep an upright posture. While studying, I have found whenever I become frustrated, tired, or when my mind begins to wander I slouch. The Upright then vibrates and I become aware of these feelings and thoughts, and can quickly correct them. This device has improved my posture, created awareness, and increased my overall study time.”

Suggestions to reduce slouching and improve ergonomics

How to arrange your computer and laptop: https://peperperspective.com/2014/09/30/cartoon-ergonomics-for-working-at-the-computer-and-laptop/

Relieve neck and shoulder stiffness: https://peperperspective.com/2019/05/21/relieve-and-prevent-neck-stiffness-and-pain/

Cellphone health: https://peperperspective.com/2014/11/20/cellphone-harm-cervical-spine-stress-and-increase-risk-of-brain-cancer/

References

Colombo, S., Joy, M., Mason, L., Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Booiman, A. (2017). Posture Change Feedback Training and its Effect on Health. Poster presented at the 48th Annual Meeting of the Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, Chicago, IL March, 2017. Abstract published in Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.42(2), 147.

Gokhale, E. (2013). 8 Steps to a Pain-Free Back. Pendo Press.

Schneider, M. (2016). Vision for Life. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic.