Freeing the neck and shoulders*

Posted: April 6, 2017 Filed under: Neck and shoulder discomfort, self-healing, Uncategorized | Tags: computer, flexibility, Holistic health, neck pain, relaxation, repetitive strain injurey, shoulder pain, somatic practices, stress 4 CommentsStress, incorrect posture, poor vision and not knowing how to relax may all contribute to neck and shoulder tension. More than 30% of all adults experience neck pain and 45% of girls and 19% of boys 18 year old, report back, neck and shoulder pain (Cohen, 2015; Côté, Cassidy, & Carroll, 2003; Hakala, Rimpelä, Salminen, Virtanen, & Rimpelä, 2002). Shoulder pain affects almost a quarter of adults in the Australian community (Hill et al, 2010). Most employees working at the computer experience neck and shoulder tenderness and pain (Brandt et al, 2014), more than 33% of European workers complained of back-ache (The European Agency for Safety and Health at Work, 2004), more than 25% of Europeans experience work-related neck-shoulder pain, and 15% experience work-related arm pain (Blatter & De Kraker, 2005; Eijckelhof et al, 2013), and more than 90% of college students report some muscular discomfort at the end of the semester especially if they work on the computer (Peper & Harvey, 2008).

The stiffness in the neck and shoulders or the escalating headache at the end of the day may be the result of craning the head more and more forward or concentrating too long on the computer screen. Or, we are unaware that we unknowingly tighten muscles not necessary for the task performance—for example, hunching our shoulders or holding our breath. This misdirected effort is usually unconscious, and unfortunately, can lead to fatigue, soreness, and a buildup of additional muscle tension.

The stiffness in the neck and shoulders or the escalating headache at the end of the day may be the result of craning the head more and more forward or concentrating too long on the computer screen. Poor posture or compromised vision can contribute to discomfort; however, in many cases stress is major factor. Tightening the neck and shoulders is a protective biological response to danger. Danger that for thousands of years ago evoke a biological defense reaction so that we could run from or fight from the predator. The predator is now symbolic, a deadline to meet, having hurry up sickness with too many things to do, anticipating a conflict with your partner or co-worker, worrying how your child is doing in school, or struggling to have enough money to pay for the rent.

Mind-set also plays a role. When we’re anxious, angry, or frustrated most of us tighten the muscles at the back of the neck. We can also experience this when insecure, afraid or worrying about what will happen next. Although this is a normal pattern, anticipating the worst can make us stressed. Thus, implement self-care strategies to prevent the occurrence of discomfort.

What can you do to free up the neck and shoulder?

Become aware what factors precede the neck and shoulder tension. For a week monitor yourself, keep a log during the day and observe what situations occur that precede the neck and should discomfort. If the situation is mainly caused by:

- Immobility while sitting and being captured by the screen. Interrupt sitting every 15 to 20 minutes and move such as walking around while swinging your arms.

- Ergonomic factors such as looking down at the computer or laptop screen while working. Change your work environment to optimize the ergonomics such as using a detached keyboard and raising the laptop screen so that the top of the screen is at eyebrow level.

- Emotional factors. Learn strategies to let go of the negative emotions and do problem solving. Take a slow deep breath and as you exhale imagine the stressor to flow out and away from you. Be willing to explore and change ask yourself: “What do I have to have to lose to change?”, “Who or what is that pain in my neck?”, or “What am I protecting by being so rigid?”

Regardless of the cause, explore the following five relaxation and stretching exercises to free up the neck and shoulders. Be gentle, do not force and stop if your discomfort increases. When moving, continue to breathe.

1. WIGGLE. Wiggle and shake your body many times during the day. The movements can be done surreptitiously such as, moving your feet back and forth in circles or tapping feet to the beat of your favorite music, slightly arching or curling your spine, sifting the weight on your buttock from one to the other, dropping your hands along your side while moving and rotating your fingers and wrists, rotating your head and neck in small unpredictable circles, or gently bouncing your shoulders up and down as if you are giggling. Every ten minutes, wiggle to facilitate blood flow and muscle relaxation.

2. SHAKE AND BOUNCE. Stand up, bend your knees slightly, and let your arms hang along your trunk. Gently bounce your body up and down by bending and straightening your knees. Allow the whole body to shake and move for about one minute like a raggedy Ann doll. Then stop bouncing and alternately reach up with your hand and arm to the ceiling and then let the arm drop. Be sure to continue to breathe.

3. ROTATION MOVEMENT (Adapted from the work by Sue Wilson and reproduced by permission from: Gorter, R. & Peper, E. (2011). Fighting Cancer- A Nontoxic Approach to Treatment).

Pre-assessment: Stand up and give yourself enough space, so that when you lift your arms to shoulder level and rotate, you don’t touch anything. Continue to stand in the same spot during the exercise as shown in figures 1a and 1b.

Lift your arms and hold them out, so that they are at shoulder level, positioned like airplane wings. Gently rotate your arms to the left as far as you can without discomfort. Look along your left arm to your fingertips and beyond to a spot on the wall and remember that spot. Rotate back to center and drop your arms to your sides and relax.

Figures 1a and 1b. Rotating the arms as far as is comfortable (photos by Jana Asenbrennerova)

Figures 1a and 1b. Rotating the arms as far as is comfortable (photos by Jana Asenbrennerova)

Movement practice. Again, lift your arms to the side so that they are like airplane wings pointing to the left and right. Gently rotate your trunk, keeping your arms fixed at a right angle to your body. Rotate your arms to the right and turn your head to the left. Then reverse the direction and rotate your arms in a fixed position to the left and turn your head to the right. Do not try to stretch or push yourself. Repeat the sequence three times in each direction and then drop your arms to your sides and relax.

With your arms at your sides, lift your shoulders toward your ears while you keep your neck relaxed. Feel the tension in your shoulders, and hold your shoulder up for five seconds. Let your shoulders drop and relax. Then relax even more. Stay relaxed for ten seconds.

Repeat this sequence, lifting, dropping, and relaxing your shoulders two more times. Remember to keep breathing; and each time you drop your shoulders, relax even more after they have dropped.

Repeat the same sequence, but this time, very slowly lift your shoulders so that it takes five seconds to raise them to your ears while you continue to breathe. Keep relaxing your neck and feel the tension just in your shoulders. Then hold the tension for a count of three. Now relax your shoulders very slowly so that it takes five seconds to lower them. Once they are lowered, relax them even more and stay relaxed for five seconds. Repeat this sequence two more times.

Now raise your shoulders quickly toward your ears, feel the tension in your upper shoulders, and hold it for the count of five. Let the tension go and relax. Just let your shoulders drop. Relax, and then relax even more.

Post-assessment. Lift your arms up to the side so that they are at shoulder level and are positioned like airplane wings. Gently rotate without discomfort to the left as far as you can while you look along your left arm to your fingers and beyond to a spot on the wall.

Almost everyone reports that when they rotate the last time, they rotated significantly further than the first time. The increased flexibility is the result of loosening your shoulder muscles.

4. TAPPING FEET (adapted from the work of Servaas Mes)

Diagonal movements underlie human coordination and if your coordination is in sync, this will happen as a reflex without thought. There are many examples of these basic reflexes, all based on diagonal coordination such as arm and leg movement while walking. To restore this coordination, we use exercises that emphasize diagonal movements. This will help you reverse unnecessary tension and use your body more efficiently and thereby reducing “sensory motor amnesia” and dysponesis (Hanna, 2004). Remember to do the practices without straining, with a sense of freedom, while you continue relaxed breathing. If you feel pain, you have gone too far, and you’ll want to ease up a bit. This practice offers brief, simple practices to avoid and reverse dysfunctional patterns of bracing and tension and reduce discomfort. Practicing healthy patterns of movement can reestablish normal tone and reduce tension and pain. This is a light series of movements that involve tapping your feet and turning your head. You’ll be able to do the entire exercise in less than twenty seconds.

Pre-assessment. Sit erect at the edge of the chair with your hands on your lap and your feet shoulders’ width apart, with your heels beneath your knees.

First, notice your flexibility by gently rotating your head to the right as far as you can. Now look at a spot on the wall as a measure of how far you can comfortably turn your head and remember that spot. Then rotate back to the center.

Practicing rotating feet and head. Become familiar with the feet movement, lift the balls of your feet so your feet are resting on your heels. Lightly pivot the balls of your feet to the right, tap the floor, and then stop and relax your feet for just a second. Now lift the balls of your feet, pivot your feet to the left, tap, relax, and pivot back to the right.

Just let your knees follow the movement naturally. This is a series of ten light, quick, relaxed pivoting movements—each pivot and tap takes only about one or two seconds.

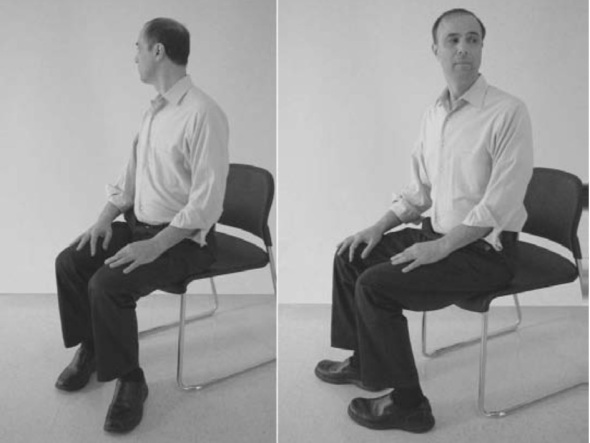

Add head rotation. Turn your head in the opposite direction of your feet. This series of movements provides effortless stretches that you can do in less than half a minute as shown in figures 2a and 2b.

Figures 2a and 2b. Rotating the feet and head in opposite directions (photos by Gary Palmer)

Figures 2a and 2b. Rotating the feet and head in opposite directions (photos by Gary Palmer)

When you’re facing right, move your feet to the left and lightly tap. Then face left and move your feet to the right and tap.

- Continue the tapping movement, but each time pivot your head in the opposite direction. Don’t try to stretch or force the movement.

- Do this sequence ten times. Now stop, face straight head, relax your legs, and just keep breathing.

Post assessment. Rotate your head to the right as far as you can see and look at a spot on the wall. Notice how much more flexibility/rotation you have achieved.

Almost everyone reports being able to rotate significantly farther after the exercise than before. They also report that they have less stiffness in their neck and shoulders.

5. SHOULDER AWARENESS PRACTICE. Sit comfortably with your hands on your lap. Allow your jaw to hang loose and breathe diaphragmatically. Continue to breathe slowly as you do the following:

- Shrug, raising your shoulders towards your ears to 70% of maximum effort and hold them up for about 10 seconds (note the sensations of tension).

- Let your shoulders drop and relax for 10 to 20 seconds

- Shrug, raising your shoulders towards your ears to 50% of maximum effort and hold them up for about 10 seconds (note the sensations of tension).

- Let your shoulders drop and relax for 10 to 20 seconds

- Shrug, raising your shoulders towards your ears to 25% of maximum effort and hold them up for about 10 seconds (note the sensations of tension).

- Let your shoulders drop and relax for 10 to 20 seconds

- Shrug, raising your shoulders towards ears to 5% of maximum effort and hold them up for about 10 seconds (note the sensations of tension).

- Let your shoulders drop and relax for 10 to 20 seconds

- Pull your shoulders down to 25% of maximum effort and hold them up for about 10 seconds (note the sensations of tension).

- Allow your shoulders to come back up and relax for 10 to 20 seconds

Remember to relax your shoulders completely after each incremental tightening. If you tend to hold your breath while raising your shoulders, gently exhale and continue to breathe. When you return to work, check in occasionally with your shoulders and ask yourself if you can feel any of the sensations of tension. If so, drop your shoulders and relax for a few seconds before resuming your tasks.

In summary, when employees and students change their environment and integrate many movements during the day, they report a significant decrease in neck and shoulder discomfort and an increase in energy and health. As one employee reported, after taking many short movement breaks while working at the computer, that he no longer felt tired at the end of the day, “Now, there is life after five”.

To explore how prevent and reverse the automatic somatic stress reactions, read Thomas Hanna‘s book, Somatics: Reawakening The Mind’s Control of Movement, Flexibility, and Health. For easy to do neck and shoulder guided instructions stretches, see the following ebsite: http://greatist.com/move/stretches-for-tight-shoulders

References:

Blatter, B. M., & Kraker, H. D. (2005). Prevalentiecijfers van RSI-klachten en het vóórkomen van risicofactoren in 15 Europese landen. Tijdschrift voor gezondheidswetenschappen, 1, 83, 8-15.

Côté, P., Cassidy, J. D., & Carroll, L. (2003). The epidemiology of neck pain: what we have learned from our population-based studies. The Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association, 47(4), 284. http://www.pain-initiative-un.org/doc-

European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (2004). http://europa.eu.int/comm/employment_social/news/2004/nov/musculoskeletaldisorders_en.html

Paoli, P., Merllié, D., & Fundação Europeia para a Melhoria das Condições de Vida e de Trabalho. (2001). Troisième enquête européenne sur les conditions de travail, 2000.

*I thank Sue Wilson and Servaas Mes for teaching me these somatic practices.

Adjust your world to fit you: Become the unreasonable person!*

Posted: November 12, 2014 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: computer, ergonomics, muscle tension, neck pain, posture 2 Comments“Reasonable people adapt themselves to the world; unreasonable people persist in trying to adapt the world to themselves. Therefore all progress depends on unreasonable people.”

–Paraphrased from Bernard Shaw

Having the right equipment and work environment will reduce injury and improve performance. This is true for athletes as well as for people using computers, laptops, tablets and smartphones. We look down and curve our upper spine to read the tablet, crane our heads forward to read the screen, lift our shoulders, arms and hands up to the laptop keyboard to enter data, and we bend our heads down and squint to read the smartphone—all occurring without awareness (Straker et al, 2008; Asunda, Odell, Luce, & Dennerlein, 2010; Peper et al, 2014). We are captured by the devices and stay immobilized until we hurt. At the end of the work day, we are often exhausted and experience neck and shoulder stiffness, arm pain and eye fatigue. This stress immobility syndrome is the twenty first century reward for digital immigrants and natives.

We hurt because we fit ourselves to the environment instead of changing the environment to fit us. The predominant slouched position even affects our mood and strength (Peper and Lin, 2012). Experience how your strength decreases when you slouch and look downward as compared when you sit tall with your spine lengthened at your laptop, tablet or phone. You will need a partner to do this practice as shown in Figure 1.

Sit in your slouched position while looking down and extend your arm to the side. Have your partner stand behind you and gently press downward on your upper arm near your wrist while you attempt to resist the pressure. Now relax and let your arms hang along the side of your body. Now sit upright in a tall position with your spine lengthening while looking straight ahead. Again extend your arm and gently have your gently press downward on your upper arm near your wrist while you attempt to resist the pressure.

Figure 1. Measuring the ability to resist the downward pressure on the forearm while sitting in either slouched or tall position.

Figure 1. Measuring the ability to resist the downward pressure on the forearm while sitting in either slouched or tall position.

You probably experienced significantly more strength resisting the downward pressure when sitting erect and tall than when sitting collapsed as we discovered in our study at San Francisco State University in with students as shown in figure 2.

Figure 2. Change in perceived strength resisting a downward pressure on the extended arm while sitting. Reproduced by permission from Schwanbeck, R., Peper, E., Booiman, A., Harvey, R., and Lin, I-M. (in press).

Increase your power and take charge! Arrange your laptop, computer and tablet so it fits you. This usually means changing your home and office chairs and desks; since, they have been manufactured for the average person. Just like the average coach airplane seat – it is uncomfortable for most people. As my colleague Annette Booiman who is a Mensendiek practitioner has pointed out, “An incorrectly adjusted chair or table height will force you to work in a dysfunctional body position while an appropriately adjusted chair or table height offers you the opportunity to work in a healthy position.”

Become the unreasonable person and fit the world so that you are comfortable while using digital devices. There are solutions! Take responsibility and adjust your posture to a healthy one–it will make your life so much more energetic. Sit on your sit bones (ischial tuberosities) as if they are the feet of your pelvis and feel your spine lengthening as you sit tall. Alternatively, stand while working and adjust the desk height for your size. Regardless of whether you sit or stand while working, take many breaks to interrupt your immobilized posture. Install a software program on computer to remind you to take breaks and watch the YouTube clips on cartoon ergonomics for working at the computer.

Implement the following common sense ergonomic guidelines:

For working at a computer sit in a chair with your feet on the floor, the elbows bend at 90 degrees with the hands, wrists, and forearms are straight, in-line and roughly parallel to the floor so that the hands can be on the keyboard while the top of monitor is at eye brow level as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Optimum position to sit at a computer work station. From: http://bmarthur.files.wordpress.com/2009/03/good-posture-how-to-sit-at-a-desk.png

For working with a laptop you will always compromise body position. If the screen is at eye level, you have to bring your arms and hands up to the keyboard, or, more commonly, you will look down at the screen while at the same time raising your hands to reach the keyboard. The solution is to use an external keyboard so that the keyboard can be at your waist position and the laptop screen eye level as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Optimum position to sit while using a laptop. From: http://www.winwin-tech.com/uploadfile/cke/images/6.jpg

For working with tablets and smart phones you have little choice. You either look down or reach up to touch the screen. As much as possible tilt and raise the tablet so that you do not have slouch to see the screen.

If you observe that you slouch and collapse while working, invest in an adjustable desk that you can raise or lower for your optimum height. An adjustable height desk such as the unDesk offers the opportunity to change work position from sitting to standing as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Example of a height adjustable desk (the unDesk) that can be used for sitting and standing.

Although office chairs can give support, we often slouch in them. While at home we use any chair that is available—again encouraging slouching. Reduce the slouching by sitting on a seat insert such as a BackJoy® which tends to let you sit more erect and in a more powerful and energizing position see Figure 6.

Figure 6. Example how BackJoy® seat inserts allows you to sit more erect. Reproduced with permission from: http://www.backjoy.com/sit/

Finally, whether or not you can change your environment, take many, many short movement breaks– wiggle, stretch, get up and walk–to interrupt the muscle tension and allow yourself to regenerate. To remind yourself to take breaks while being captured by your work, install a reminder program on your computer such as Stretchbreak that pops up on the screen and guides you through short stretches to regenerate.

Suggested sources:

Cartoon videos on ergonomics: https://peperperspective.com/2014/09/30/cartoon-ergonomics-for-working-at-the-computer-and-laptop/

Healthy computing tips: http://biofeedbackhealth.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/health-computing-email-tips.pdf

Seat insert such as BackJoy®: http://www.backjoy.com/sit/

Height adjustable desk such as The unDesk: http://www.theundesk.com/

Interrupt computer program such as Stretchbreak: http://www.paratec.com

References:

Asundi, K., Odell, D., Luce, A., & Dennerlein, J. T. (2010). Notebook computer use on a desk, lap and lap support: Effects on posture, performance and comfort. Ergonomics, 53(1), 74-82.

Peper, E., & Lin, I. M. (2012). Increase or decrease depression-How body postures influence your energy level. Biofeedback, 40 (3), 126-130.

Peper, E., Booiman, A., Lin, I-M., & Shaffer, F. Making the Unaware Aware-Surface Electromyography to Unmask Tension and Teach Awareness. Biofeedback, 2(1), 16-23.

Schwanbeck, R., Peper, E., Booiman, A., Harvey, R., and Lin, I-M. Posture changes with a seat insert: Changes in strength and implications for breathing and HRV. Poster submitted for the 46th Annual Meeting of the Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Straker, L. M., Coleman, J., Skoss, R., Maslen, B. A., Burgess-Limerick, R., & Pollock, C. M. (2008). A comparison of posture and muscle activity during tablet computer, desktop computer and paper use by young children. Ergonomics, 51(4), 540-555.

* Adapted from: Peper, E. (in press). Become the unreasonable person: Adjust your world to fit you! Western Edition and Schwanbeck, R., Peper, E., Booiman, A., Harvey, R., and Lin, I-M. (in press). Posture changes with a seat insert: Changes in strength and implications for breathing and HRV.

Cartoon ergonomics for working at the computer and laptop

Posted: September 30, 2014 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: cell phones, computer, health, Laptop, muscle tension, neck pain, pain, posture, shoulder pain 6 CommentsI finally bought a separate keyboard and a small stand for my laptop so that the screen is at eye level and my shoulders are relaxed while typing at the keyboard. To my surprise, my neck and shoulder tightness and pain disappeared and I am much less exhausted.

How we sit and work at the computer significantly affects our health and productivity. Ergonomics is the science that offers guidelines on how to adjust your workspace and equipment to suit your individual needs. It is just like choosing appropriate shoes–Ever try jogging in high heels? The same process applies to the furniture and equipment you use when computing.

When people arrange their work setting according to good ergonomic principles and incorporate a healthy computing work style numerous disorders (e.g., fatigue, vision discomfort, head, neck, back, shoulder, arm or hand pain) may be prevented (Peper et al, 2004). For pragmatic tips to stay health at the computer see Erik Peper’s Health Computer Email Tips. Enjoy the following superb video cartoons uploaded by Stephen Walker on YouTube that summarize the basic guidelines for computer, laptop and cell phones use at work, home, or while traveling.

Adult or Child Laptop Use at Home, Work or Classroom

Healthy use of laptops anywhere.

Mobile or Smart Phone Use while Driving, Traveling or on the Move.