Quick Rescue Techniques When Stressed

Posted: February 4, 2024 Filed under: attention, behavior, biofeedback, Breathing/respiration, CBT, cognitive behavior therapy, education, emotions, Evolutionary perspective, Exercise/movement, health, mindfulness, Neck and shoulder discomfort, posture, relaxation, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: alarm reaction, anxiety, box breathing, Breathing, conditioning, defense reaction, health, huming, Parasympathetic response, rumination, safety, sniff inhale, somatic practices, stress, sympathetic arousal, tactical breathing, Toning, yoga 2 CommentsErik Peper, PhD, Yuval Oded, PhD, and Richard Harvey, PhD

Adapted from Peper, E., Oded, Y, & Harvey, R. (2024). Quick somatic rescue techniques when stressed. Biofeedback, 52(1), 18–26. https://doi.org/10.5298/982312

“If a problem is fixable, if a situation is such that you can do something about it, then there is no need to worry. If it’s not fixable, then there is no help in worrying. There is no benefit in worrying whatsoever.” ― Dalai Lama XIV

To implement the Dalai Lama’s quote is challenging. When caught up in an argument, being angry, extremely frustrated, or totally stressed, it is easy to ruminate, worry. It is much more challenging to remember to stay calm. When remembering the message of the Dalai Lama’s quote, it may be possible to shift perspective about the situation although a mindful attitude may not stop ruminating thoughts. The body typically continues to reacti to the torrents of thoughts that may occur when rehashing rage over injustices, fear over physical or psychological threats, or profound grief and sadness over the loss of a family member. Some people become even more agitated and less rational as illustrated in the following examples.

I had an argument with my ex and I am still pissed off. Each time I think of him or anticipate seeing them, my whole body tightened. I cannot stomach seeing him and I already see the anger in his face and voice. My thoughts kept rehashing the conflict and I am getting more and more upset.

A car cut right in front of me to squeeze into my lane. I had to slam on my brakes. What an idiot! My heart rate was racing and I wanted to punch the driver.

When threatened, we respond quickly in our thoughts and body with a defense reaction that may negatively affect those around us as well as ourselves. What can we do to interrupt negative stress reactions?

Background

Many approaches exist that allow us to become calmer and less reactive. General categories include techniques of cognitive reappraisal (seeing the situation from the other person’s point of view and labeling your own feelings and emotions) and stress management techniques. Practices that are beneficial include mindfulness meditation, benign humor (versus gallows humor), listening to music, taking a time out while implementing a variety of self-soothing practices, or incorporating slow breathing (e.g., heart rate variability and/or box breathing) throughout the day.

No technique fits all as we respond differently to our stressful life circumstances. For example, some people during stress react with a “tend and befriend stress response” (Cohen & Lansing, 2021; Taylor et al., 2000). This response appears to be mostly mediated by the hormone oxytocin acting in ways that sooth or calm the nervous system as an analgesic. These neurophysiological mechanisms of the soothing with the calming analgesic effects of oxytocin have been characterized in detail by Xin, et al. (2017).

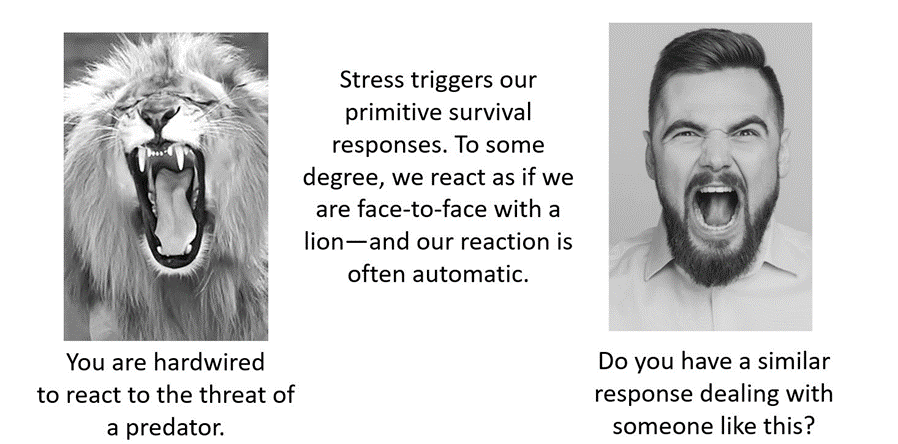

The most common response is a fight/flight/freeze stress response that is mediated by excitatory hormones such as adrenalin and inhibitory neurotransmitters such as gamma amino butyric acid (GABA). There is a long history of fight/flight/freeze stress response research, which is beyond the scope of this blog with major theories and terms such as interior milleau (Bernard, 1872); homeostasis and fight/flight (Cannon, 1929); general adaptation syndrome (Selye, 1951); polyvagal theory (Porges, 1995); and, allostatic load (McEwen, 1998). A simplified way to start a discussion about stress reactions begins with the fight/flight stress response. When stressed our defense reactions are triggered. Our sympathetic nervous system becomes activated our mind and body stereotypically responds as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. An intense confrontation tends to evoke a stress response (reproduced from Peper et al., 2020).

The flight/fight response triggers a cascade of stress hormones or neurotransmitters (e.g., hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal cascade) and produces body changes such as the heart pounding, quicker breathing, an increase in muscle tension and sweating. Our body mobilizes itself to protect itself from danger. Our focus is on immediate survival and not what will occur in the future (Porges, 2021; Sapolsky, 2004). It is as if we are facing an angry lion—a life-threatening situation—and we feel threatened and unsafe.

Rather than sitting still, a quick effective strategy is to interrupt this fight/flight response process by completing the alarm reaction such as by moving our muscles (e.g., simulating a fight or flight behavior) before continuing with slower breathing or other self-soothing strategies. Many people have experienced their body tension is reduced and they feel calmer when they do vigorous exercise after being upset, frustrated or angry. Similarly, athletes often have reported that they experience reduced frequency and/or intensity of negative thoughts after an exhausting workout (Thayer, 2003; Liao et al., 2015; Basso & Suzuki, 2017).

Becoming aware of the escalating cascades of physical, behavioral and psychological responses to a stressor is the first step in interrupting the escalating process. After becoming aware, reduce the body’s arousal and change the though patterns using any of the techniques described in this blog. The self-regulation skills presented in this blog are ideally over-learned and automated so that these skills can be rapidly implemented to shift from being stressed to being calm. Examples of skills that can shift from sympathetic neervous system overarousal to parasympathetic nervous system calm include techniques of autogenic traing (Schulz & Luthe, 1959), the quieting reflex developed by Charles Stroebel in 1985 or more recently rescue breathing developed by Richard Gevirtz (Stroebel, 1985; Gevirtz, 2014; Peper, Gibney & Holt, 2002; Peper & Gibney, 2003).

Concepts underlying the rescue techniques

- Psychophysiological principle: “Every change in the physiological state is accompanied by an appropriate change in the mental-emotional state, conscious or unconscious, and conversely, every change in the mental-emotional state, conscious or unconscious, is accompanied by an appropriate change in the physiological state” (Green et al. 1970, p. 3).

- Posture evokes memories and feelings associated with the position. When the body posture is erect and tall while looking slightly up. It is easier to evoke empowering, positive thoughts and feelings. When looking down it is easier to evoke hopeless, helpless and powerless thoughts and feelings (Peper et al., 2017).

- Healing occurs more easily when relaxed and feeling safe. Feeling safe and nurtured enhances the parasympathetic state and reduces the sympathetic state. Use memory recall to evoke those experiences when you felt safe (Peper, 2021).

- Interrupting thoughts is easier with somatic movement than by redirecting attention and thinking of something else without somatic movement.

- Focus on what you want to do not want to do. Attempting to stop thinking or ruminating about something tends to keeps it present (e.g., do not think of pink elephants. What color is the elephant? When you answer, “not pink,” you are still thinking pink). A general concept is to direct your attention (or have others guide you) to something else (Hilt & Pollak, 2012; Oded, 2018; Seo, 2023).

- Skill mastery takes practice and role rehearsal (Lally et al., 2010; Peper & Wilson, 2021).

- Use classical conditioning concepts to facilitate shifting states. Practice the skills and associate them with an aroma, memory, sounds or touch cues. Then when you the situation occurs, use these classical conditioned cues to facilitate the regeneration response (Peper & Wilson, 2021).

Rescue techniques

Coping When Highly Stressed and Agitated

- Complete the alarm/defense reaction with physical activity (Be careful when you do these physical exercises if you have back, hip, knee, or ankle problems).

- Acknowledge you have reacted and have chosen to interrupt your automatic response.

- Check whether the situation is actually a threat. If yes, then do anything to get out of immediate danger (yell, scream, fight, run away, or dial 911).

- If there is no actual physical threat, then leave the situation and perform vigorous physical activity to complete your alarm reaction, such as going for a run or walking quickly up and down stairs. As you do the exercise, push yourself so that the muscles in your thighs are aching, which focusses your attention on the sensations in your thighs. In our experience, an intensive run for 20 minutes quiets the brain while it often takes 40 minutes when walking somewhat quickly.

- After recovering from the exhaustive exercise, explore new options to resolve the conflict.

- Complete the alarm/defense reaction and evoke calmness with the S.O.S™ technique (Oded, 2023)

- Acknowledge you have reacted and have chosen to interrupt your automatic response.

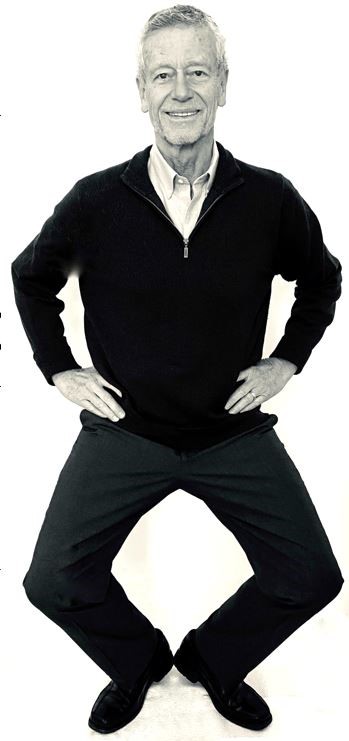

- Squat against a wall (similar to the wall-sit many skiers practice). While tensing your arms and fists as shown in Figure 2, gaze upward because it is more difficult to engage in negative thinking while looking upwards. If you continue to ruminate, then scan the room for object of a certain color or feature to shift visual attention and be totally present on the visual object.

- Do this set of movements for 7 to 10 seconds or until you start shaking. Than stand up and relax hands and legs. While standing, bounce up and down loosely for 10 to 15 seconds as you become aware of the vibratory sensations in your arms and shoulders, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2.Defense position wall-sit to tighten muscles in the protective defense posture (Oded, 2023). Figure 3. Bouncing up and down to loosen muscles ((Oded, 2023).

- Acknowledge you have reacted and have chosen to interrupt your automatic response. Swing your arms back and forth for 20 seconds. Allow the arms to swing freely as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Swinging the arms to loosen the body and spine (Oded, 2023).

- Rest and ground. Lie on the floor and put your calves and feet on a chair seat so that the psoas muscle can relax, as illustrated in Figure 5. Allow yourself to be totally supported by the floor and chair. Be sure there is a small pillow under your head and put your hand on your abdomen so that you can focus on abdominal breathing.

Figure 5. Lying down to allow the psoas muscle to relax and feel grounded (Oded, 2023).

- While lying down, imagine a safe place or memory and make it as real as possible. It is often helpful to listen to a guided imagery or music. The experience can be enhanced if cues are present that are associated with the safe place, such as pictures, sounds, or smells. Continue to breathe effortlessly at about six breaths per minute. If your attention wanders, bring it back to the memory or to the breathing. Allow yourself to rest for 10 minutes.

In most cases, thoughts stop and the body’s parasympathetic activity becomes dominant as the person feels safe and calm. Usually, the hands warm and the blood volume pulse amplitude increases as an indicator of feeling safe, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Blood volume pulse increases as the person is relaxing, feels safe and calm.

Coping When You Can’t Get Away (adapted from Peper, Harvey & Faass, 2020)

In many cases, it is difficult or embarrassing to remove yourself from the situation when you are stressed out such as at work, in a business meeting or social gathering.

- Become aware that you have reacted.

- Excuse yourself for a moment and go to a private space, such as a restroom. Going to the bathroom is one of the only acceptable social behaviors to leave a meeting for a short time.

- In the bathroom stall, do the 5-minute Nyingma exercise, which was taught by Tarthang Tulku Rinpoche in the tradition of Tibetan Buddhism, as a strategy for thought stopping (see Figure 7). Stand on your toes with your heels touching each other. Lift your heels off the floor while bending your knees. Place your hands at your sides and look upward. Breathe slowly and deeply (e.g., belly breathing at six breaths a minute) and imagine the air circulating through your legs and arms. Do this slow breathing and visualization next to a wall so you can steady yourself if necessary to keep balance. Stay in this position for 5 minutes or longer. Do not straighten your legs—keep squatting despite the discomfort. In a very short time, your attention is captured by the burning sensation in your thighs. Continue. After 5 minutes, stop and shake your arms and legs.

Figure 7. Stressor squat Nyingma exercise (reproduced from Peper et al., 2020).

- Follow this practice with slow abdominal breathing to enhance the parasympathetic response. Be sure that the abdomen expands as the inhalation occurs. Breathe in and out through the nose at about six breaths per minute.

- Once you feel centered and peaceful, return to the room.

- After this exercise, your racing thoughts most likely will have stopped and you will be able to continue your day with greater calm.

What to do When Ruminating, Agitated, Anxious or Depressed

(adapted from Peper, Harvey, & Hamiel, 2019).

- Shift your position by sitting or standing erect in a power position with the back of the head reaching upward to the ceiling while slightly gazing upward. Then sniff quickly through nose, hold and again sniff quickly then very slowly exhale. Be sure as you exhale your abdomen constricts. Then sniff again as your abdomen gets bigger, hold, and sniff one more time letting the abdomen get even bigger. Then, very slow, exhale through the nose to the internal count of six (adapted from Balban et al., 2023). When you sniff or gasp, your racing thoughts will stop (Peper et al., 2016).

- Continue with box breathing (sometimes described as tactical breathing or battle breathing) by exhaling slowly through your nose for 4 seconds, holding your breath for 4 seconds, inhaling slowly for 4 seconds through your nose, holding your breath for 4 seconds and then repeating this cycle of breathing for a few minutes (Röttger et al., 2021; Balban et al., 2023). Focusing your attention on performing the box breathing makes it almost impossible to think of anything else. After a few minutes, follow this with slow effortless diaphragmatic breathing at about six breaths per minute. While exhaling slowly through your nose, look up and when you inhale imagine the air coming from above you. Then as you exhale, imagine and feel the air flowing down and through your arms and legs and out the hands and feet.

- While gazing upward, elicit a positive memory or a time when you felt safe, powerful, strong and/or grounded. Make the positive memory as real as possible.

- Implement cognitive strategies such as reframing the issue, sending goodwill to the person, seeing the problem from the other person’s point of view, and ask is this problem worth dying over (Peper, Harvey, & Hamiel, 2019).

What to Do When Thoughts Keep Interrupting

Practice humming or toning. When you are humming or toning, your focus is on making the sound and the thoughts tend to stop. Generally, breathing will slow down to about six breaths per minute (Peper, Pollack et al., 2019). Explore the following:

- Box breathing (Röttger et al., 2021; Balban et al., 2023)

- Humming also known as bee breath (Bhramari Pranayama) (Abishek et al., 2019; Yoga, 2023) – Allow the tongue to rest against the upper palate, sit tall and erect so that the back of the head is reaching upward to the ceiling, and inhale through your nose as the abdomen expands. Then begin humming while the air flows out through your nose, feel the vibration in the nose, face and throat. Let humming last for about 7 seconds and then allow the air to blow in through the nose and then hum again. Continue for about 5 minutes.

- Toning – Inhale through your nose and then vocalize a single sound such as Om. As you vocalize the lower sound, feel the vibration in your throat, chest and even going down to the abdomen. Let each toning exhalation last for about 6 to 7 seconds and then inhale through your nose. Continue for about 5 minutes (Peper, al., 2019).

Many people report that after practice these skills, they become aware that they are reacting and are able to reduce their automatic reaction. As a result, they experience a significant decrease in their stress levels, fewer symptoms such as neck and holder tension and high blood pressure, and they feel an increase in tranquility and the ability to communicate effectively.

Practicing these skills does not resolve the conflicts; they allow you to stop reacting automatically. This process allows you a time out and may give you the ability to be calmer, which allows you to think more clearly. When calmer, problem solving is usually more successful. As phrased in a popular meme, “You cannot see your reflection in boiling water. Similarly, you cannot see the truth in a state of anger. When the waters calm, clarity comes” (author unknown).

Boiling water (photo modified from: https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=388991500314839&set=a.377199901493999)

Below are additional resources that describe the practices. Please share these resources with friends, family and co-workers.

Stressor squat instructions

Toning instructions

Diaphragmatic breathing instructions

Reduce stress with posture and breathing

Conditioning

References

Abishek, K., Bakshi, S. S., & Bhavanani, A. B. (2019). The efficacy of yogic breathing exercise bhramari pranayama in relieving symptoms of chronic rhinosinusitis. International Journal of Yoga, 12(2), 120–123. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijoy.IJOY_32_18

Balban, M. Y., Neri, E., Kogon, M. M., Weed, L., Nouriani, B., Jo, B., Holl, G., Zeitzer, J. M., Spiegel, D., Huberman, A. D. (2023). Brief structured respiration practices enhance mood and reduce physiological arousal. Cell Reports Medicine, 4(1), 10089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100895

Basso, J. C. & Suzuki, W. A. (2017). The effects of acute exercise on mood, cognition, neurophysiology, and neurochemical pathways: A review. Brain Plast, 2(2), 127–152. https://doi.org/10.3233/BPL-160040

Bernard, C. (1872). De la physiologie générale. Paris: Hachette livre. https://www.amazon.ca/PHYSIOLOGIE-GENERALE-BERNARD-C/dp/2012178596

Cannon, W. B. (1929). Organization for Physiological Homeostasis. Physiological Reviews, 9, 399–431. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.1929.9.3.399

Cohen, L. & Lansing, A. H. (2021). The tend and befriend theory of stress: Understanding the biological, evolutionary, and psychosocial aspects of the female stress response. In: Hazlett-Stevens, H. (eds), Biopsychosocial Factors of Stress, and Mindfulness for Stress Reduction. pp. 67–81, Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81245-4_3

Gevirtz, R. (2014). HRV Training and its Importance – Richard Gevirtz, Ph.D., Pioneer in HRV Research & Training. Thought Technology. Accessed December 29, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9nwFUKuJSE0

Green, E. E., Green, A. M., & Walters, E. D. (1970). Voluntary control of internal states: Psychological and physiological. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 2, 1–26. https://atpweb.org/jtparchive/trps-02-70-01-001.pdf

Hilt, L. M., & Pollak, S. D. (2012). Getting out of rumination: comparison of three brief interventions in a sample of youth. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40(7), 1157–1165.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-012-9638-3

Lally, P., VanJaarsveld, C. H., Potts, H. W., & Wardle, J. (2010). How habits are formed: Modelling habit formation the real world. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 998–1009. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.674

Liao, Y., Shonkoff, E. T., & Dunton, G. F. (2015). The acute relationships between affect, physical feeling states, and physical activity in daily life: A review of current evidence. Frontiers in Psychology. 6, 1975. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01975

McEwen, B. S. (1998). Stress, adaptation, and disease: Allostasis and allostatic load. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 840(1), 33–44.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09546.x

Oded, Y. (2018). Integrating mindfulness and biofeedback in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Biofeedback, 46(2), 37-47. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-46.02.03

Oded, Y. (2023). Personal communication. S.O.S 1™ technique is part of the Sense Of Safety™ method. www.senseofsafety.co

Peper, E. (2021). Relive memory to create healing imagery. Somatics, XVIII(4), 32–35.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/369114535_Relive_memory_to_create_healing_imagery

Peper, E., Gibney, K.H. & Holt. C. (2002). Make Health Happen: Training Yourself to Create Wellness. Dubuque, IA: Kendall-Hunt. https://he.kendallhunt.com/product/make-health-happen-training-yourself-create-wellness

Peper, E., & Gibney, K.H. (2003). A teaching strategy for successful hand warming. Somatics. XIV(1), 26–30. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/376954376_A_teaching_strategy_for_successful_hand_warming

Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Faass, N. (2020). TechStress: How Technology is Hijacking Our Lives, Strategies for Coping, and Pragmatic Ergonomics. North Atlantic Books. https://www.amazon.com/Beyond-Ergonomics-Prevent-Fatigue-Burnout/dp/158394768X

Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Hamiel, D. (2019). Transforming thoughts with postural awareness to increase therapeutic and teaching efficacy. NeuroRegulation, 6(3),153–160. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.6.3.153

Peper, E., Lee, S., Harvey, R., & Lin, I-M. (2016). Breathing and math performance: Implication for performance and neurotherapy. NeuroRegulation, 3(4), 142–149. http://dx.doi.org/10.15540/nr.3.4.142

Peper, E., Lin, I-M, Harvey, R., & Perez, J. (2017). How posture affects memory recall and mood. Biofeedback, 45(2), 36–41. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-45.2.01

Peper, E., Pollack, W., Harvey, R., Yoshino, A., Daubenmier, J. & Anziani, M. (2019). Which quiets the mind more quickly and increases HRV: Toning or mindfulness? NeuroRegulation, 6(3), 128–133. https://www.neuroregulation.org/article/view/19345/13263

Peper, E. & Wilson, V. (2021). Optimize the learning state: Techniques and habits. Biofeedback, 9(2), 46–49. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-49-2-04

Porges, S. W. (1995). Orienting in a defensive world: Mammalian modifications of our evolutionary heritage. A polyvagal theory. Psychophysiology, 32(4), 301–318. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.1995.tb01213.x

Porges, S.W. (2021) Cardiac vagal tone: a neurophysiological mechanism that evolved in mammals to dampen threat reactions and promote sociality. World Psychiatry, 20(2),296-298. Porges SW. Cardiac vagal tone: a neurophysiological mechanism that evolved in mammals to dampen threat reactions and promote sociality. World Psychiatry. 2021 Jun;20(2):296-298. https://doi.org10.1002/wps.20871

Röttger, S., Theobald, D. A., Abendroth, J., & Jacobsen, T. (2021). The effectiveness of combat tactical breathing as compared with prolonged exhalation. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 46, 19–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-020-09485-w

Sapolsky, R. (2004). Why zebras don’t get ulcers (3rd ed.). New York:Holt. https://www.amazon.com/Why-Zebras-Dont-Ulcers-Third/dp/0805073698/

Schultz, J. H., & Luthe, W. (1959). Autogenic training: A psychophysiologic approach to psychotherapy. Grune & Stratton. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Autogenic_Training/y8SwQgAACAAJ?hl=en

Selye, H. (1951). The general-adaptation-syndrome. Annual Review of Medicine, 2(1), 327–342. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.me.02.020151.001551

Seo, H. (2023). How to stop ruminating. The New York Times. Accessed January 3, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/01/well/mind/stop-rumination-worry.html

Stroebel, C. F. (1985). QR: The Quieting Reflex. Berkley. https://www.amazon.com/Qr-quieting-reflex-Charles-Stroebel/dp/0425085066

Taylor, S. E., Klein, L. C., Lewis, B. P., Gruenewald, T. L., Gurung, R. A. R., & Updegraff, J. A. (2000). Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: Tend-and-befriend, not fight-or-flight. Psychological Review, 107(3), 411–429. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.107.3.411

Thayer, R. E. (2003). Calm energy: How people regulate mood with food and exercise. Oxford University Press. https://www.amazon.com/Calm-Energy-People-Regulate-Exercise/dp/0195163397

Xin, Q., Bai, B., & Liu, W. (2017). The analgesic effects of oxytocin in the peripheral and central nervous system. Neurochemistry International, 103, 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuint.2016.12.021

Yoga, N. (2023). This simple breath practice is scientifically proven to calm your mind. The nomadic yogi. Accessed December 31, 2023. https://www.leahsugerman.com/blog/bhramari-pranayama-humming-bee-breath#

Cancer: What you can do to prevent and support healing

Posted: April 22, 2018 Filed under: cancer, self-healing, Uncategorized | Tags: cancer, healing, Holistic health, prevention, self-care, stress Leave a commentAre you curious to know if there is anything you can do to help prevent cancer?

Are you searching for ways to support your healing process and your immune system?

If yes, watch the invited lecture presented October 14, 2017, at the Caribbean Active Aging Congress, Oranjestad, Aruba, http://www.caacaruba.com

Breathing to improve well-being

Posted: November 17, 2017 Filed under: Breathing/respiration, Exercise/movement, Neck and shoulder discomfort, Pain/discomfort, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: anxiety, Breathing, health, mindfulness, pain, respiration, stress 8 CommentsBreathing affects all aspects of your life. This invited keynote, Breathing and posture: Mind-body interventions to improve health, reduce pain and discomfort, was presented at the Caribbean Active Aging Congress, October 14, Oranjestad, Aruba. www.caacaruba.com

The presentation includes numerous practices that can be rapidly adapted into daily life to improve health and well-being.

Healing irritable bowel syndrome with diaphragmatic breathing*

Posted: June 23, 2017 Filed under: Breathing/respiration, self-healing | Tags: abdominal pain, diaphragmatic breathing, food intolerances, health, Holistic health, IBS, irritable bowel syndrome, pain, recurrent abdominal pain, self-care, SIBO, stress, thoracic breathing 19 CommentsErik Peper, Lauren Mason and Cindy Huey

This blog was adapted and expanded from: Peper, E., Mason, L., & Huey, C. (2017). Healing irritable bowel syndrome with diaphragmatic breathing. Biofeedback. 45(4), 83-87. DOI: 10.5298/1081-5937-45.4.04 https://biofeedbackhealth.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/a-healing-ibs-published.pdf

After having constant abdominal pain, severe cramps, and losing 15 pounds from IBS, I found myself in the hospital bed where all the doctors could offer me was morphine to reduce the pain. I searched on my smart phone for other options. I saw that abdominal breathing could help. I put my hands on my stomach and tried to expand it while I inhaled. All that happened was that my chest expanded and my stomach did not move. I practiced and practiced and finally, I could breathe lower. Within a few hours, my pain was reduced. I continued breathing this way many times. Now, two years later, I no longer have IBS and have regained 20 pounds.

– 21-year old woman who previously had severe IBS

Irritable bowel syndrome(IBS) affects between 7% to 21% of the general population and is a chronic condition. The symptoms usually include abdominal cramping, discomfort or pain, bloating, loose or frequent stools and constipation and can significantly reduce the quality of life (Chey et al, 2015). A precursor of IBS in children is called recurrent abdominal pain (RAP) which affects between 0.3 to 19% of school children (Chitkara et al, 2005). Both IBS and RAP appear to be functional illnesses, as no organic causes have been identified to explain the symptoms. In the USA, this results in more than 3.1 physician visits and 5.9 million prescriptions written annually. The total direct and indirect cost of these services exceeds $20 billion (Chey et al, 2015). Multiple factors may contribute to IBS, such as genetics, food allergies, previous treatment with antibiotics, severity of infection, psychological status and stress. More recently, changes in the intestinal and colonic microbiome resulting in small intestine bacterial overgrowth are suggested as another risk factor (Dupont, 2014).

Generally, standard medical treatments (reassurance, dietary manipulation and of pharmacological therapy) are often ineffective in reducing abdominal IBS and other abdominal symptoms (Chey et al, 2015), while complementary and alternative approaches such as relaxation and cognitive therapy are more effective than traditional medical treatment (Vlieger et, 2008). More recently, heart rate variability training to enhance sympathetic/ parasympathetic balance appears to be a successful strategy to treat functional abdominal pain (FAB) in children (Sowder et al, 2010). Sympathetic/parasympathetic balance can be enhanced by increasing heart rate variability (HRV), which occurs when a person breathes at their resonant frequency which is usually between 5-7 breaths per minute. For most people, it means breathing much slower, as slow abdominal breathing appears to be a self-control strategy to reduce symptoms of IBS, RAP and FAP.

This article describes how a young woman healed herself from IBS with slow abdominal breathing without any therapeutic coaching, reviews how slower diaphragmatic breathing (abdominal breathing) may reduce symptoms of IBS, explores the possibility that breathing is more than increasing sympathetic/parasympathetic balance, and suggests some self-care strategies to reduce the symptoms of IBS.

Healing IBS-a case report

After being diagnosed with Irritable Bowel Syndrome her Junior year of high school, doctors told Cindy her condition was incurable and could only be managed at best, although she would have it throughout her entire life. With adverse symptoms including excessive weight loss and depression, Cindy underwent monthly hospital visits and countless tests, all which resulted in doctors informing her that her physical and psychological symptoms were due to her untreatable condition known as IBS, of which no one had ever been cured. When doctors offered her what they believed to be the best option: morphine, something Cindy describes now as a “band-aid,” she was left feeling discouraged. Hopeless and alone in her hospital bed, she decided to take matters into her own hands and began to pursue other options. From her cell phone, Cindy discovered something called “diaphragmatic breathing,” a technique which involved breathing through the stomach. This strategy could help to bring warmth to the abdominal region by increasing blood flow throughout abdomen, thereby relieving discomfort of the bowel. Although suspicious of the scientific support behind this method, previous attempts at traditional western treatment had provided no benefit to recovery; therefore, she found no harm in trying. Lying back flat against the hospital bed, she relaxed her body completely, and began to breathe. Immediately, Cindy became aware that she took her breath in her chest, rather than her stomach. Pushing out all of her air, she tried again, this time gasping with inhalation. Delighted, she watched as air flooded into her stomach, causing it to rise beneath her hands, while her chest remained still. Over time, Cindy began to develop more awareness and control over her newfound strategy. While practicing, she could feel her stomach and abdomen becoming warmer. Cindy shares that for the first time in years, she felt relief from pain, causing her to cry from happiness. Later that day, she was released from the hospital, after denying any more pain medication from doctors.

Cindy continues to practice her diaphragmatic breathing as much as she can, anywhere at all, at the sign of pain or discomfort, as well as preventatively prior to what she anticipates will be a stressful situation. Since beginning her practice, Cindy says that her IBS is pretty much non-existent now. She no longer feels depressed about her situation due to her developed ability to manage her condition. Overall, she is much happier. Moreover, since this time two years ago, Cindy has gained approximately 20 pounds, which she attributes to eating a lot more. In regard to her success, she believes it was her drive, motivation, and willingness to dedicate herself fully to the breathing practice which allowed for her to develop skills and prosper. Although it was not natural for her to breathe in her stomach at first, a trait which she says she often recognizes in others, Cindy explains it was due to necessity which caused her to shift her previously-ingrained way of breathing. Upon publicly sharing her story with others for the first time, Cindy reflects on her past, revealing that she experienced shame for a long time as she felt that she had a weird condition, related to abnormal functions, which no one ever talks about. On the experience of speaking out, she affirms that it was very empowering, and hopes to encourage others coping with a situation similar to hers that there is in fact hope for the future. Cindy continues to feel empowered, confident, and happy after taking control of her own body, and acknowledges that her condition is a part of her, something of which she is proud.

Watch the in-depth interview with Cindy Huey in which she describes her experience of discovering diaphragmatic breathing and how she used this to heal herself of IBS

Video 1. Interview with Cindy Huey describing how she healed herself from IBS.

Background perspective

“Why should the body digest food or repair itself, when it will be someone else’s lunch” (paraphrased from Sapolsky (2004), Why zebras do not get ulcers).

From an evolutionary perspective, we were prey and needed to be on guard (vigilant) to the presence of predators. In the long forgotten past, the predators were tigers, snakes, and the carnivore for whom we were food as well as other people. Today, the same physiological response pathways are still operating, except that the pathways are now more likely to be activated by time urgency, work and family conflict, negative mental rehearsal and self-judgment. This is reflected in the common colloquial phrases: “It makes me sick to my stomach,” “I have no stomach for it,” “He is gutless,” “It makes me queasy,” “Butterflies in my stomach,” “Don’t get your bowels in uproar,” “Gut feelings’, or “Scared shitless.”

Whether conscious or unconscious, when threatened, our body reacts with a fight/flight/freeze response in which the blood flow is diverted from the abdomen to deep muscles used for propulsion. This results in peristalsis being reduced. At the same time the abdomen tends to brace to protect it from injury. In almost all cases, the breathing patterns shift to thoracic breathing with limited abdominal movement. As the breathing pattern is predominantly in the chest, the person increases the risk of hyperventilation because the body is ready to run or fight.

In our clinical observations, people with IBS, small intestine bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), abdominal discomfort, anxiety and panic, and abdominal pain tend to breathe more in their chest, and when asked to take breathe, they tend to inhale in their upper chest with little or no abdominal displacement. Almost anyone who experiences abdominal pain tends to hold the abdomen rigid as if the splinting could reduce the pain. A similar phenomenon is observed with female students experiencing menstrual cramps. They tend to curl up to protect themselves and breathe shallowly in their chest instead of slowly in their abdomen, a body pattern which triggers a defense reaction and inhibits regeneration. If instead they breathe slowly and uncurl they report a significant decrease in discomfort (Gibney & Peper, 2003).

Paradoxically, this protective stance of bracing the abdomen and breathing shallowly in the chest increases breathing rate and reduces heart rate variability. It reduces and inhibits blood and lymph flow through the abdomen as the defensive posture evokes the physiology of fight/flight/freeze. The reduction in venous blood and lymph flow occurs because the ongoing compression and expansion in the abdomen is inhibited by the thoracic breathing and, moreover, the inhibition of diaphragmatic breathing. It also inhibits peristalsis and digestion. No wonder so many of the people with IBS report that they are reactive to some foods. If the GI track has reduced blood flow and reduced peristalsis, it may be less able to digest foods which would affect the bacteria in the small intestine and colon. We wonder if a risk factor that contributes to SIBO is chronic lack of abdominal movement and bracing.

Slow diaphragmatic abdominal breathing to establish health

“Digestion and regeneration occurs when the person feels safe.”

Effortless, slow diaphragmatic breathing occurs when the diaphragm descends and pushes the abdominal content downward during inhalation, which causes the abdomen to become bigger. As the abdomen expands, the pelvic floor relaxes and descends. During exhalation, the pelvic floor muscles tighten slightly, lifting the pelvic floor and the transverse and oblique abdominal muscles contract and push the abdominal content upward against the diaphragm, allowing the diaphragm to relax and go upward, pushing the air out. The following video, 3D view of the diaphragm, from www.3D-Yoga.com by illustrates the movement of the diaphragm.

Video 2. 3D view of diaphragm by sohambliss from www.3D-Yoga.com,

This expansion and constriction of the abdomen occurs most easily if the person is extended, whether sitting or standing erect or lying down, and the waist is not constricted. If the arches forward in a protected pattern and the spine is flexed in a c shape, it would compress the abdomen; instead, the body is long and the abdomen can move and expand during inhalation as the diaphragm descends (see figure 1). If the person holds their abdomen tight or it is constricted by clothing or a belt, it cannot expand during inhalation. Abdominal breathing occurs more easily when the person feels safe and expanded versus unsafe or fearful and collapsed or constricted.

Figure 1. Erect versus collapsed posture note that there is less space for the abdomen to expand in the protective collapsed position. Reproduced by permission from: Clinical Somatics (http://www.clinicalsomatics.ie/

When a person breathes slower and lower it encourages blood and lymph flow through the abdomen. As the person continues to practice slower, lower breathing, it reduces the arousal and vigilance. This is the opposite state of the flight, fight, freeze response so that blood flow is increased in abdomen, and peristalsis re-occurs. When the person practices slow exhalation and breathing and they slightly tighten the oblique and transverse abdominal muscles as well as the pelvic floor and allow these muscles to relax during inhalation. When they breathe in this pattern effortless they, they often will experience an increase in abdominal warmth and an initiation of abdominal sounds (stomach rumble or borborygmus) which indicates that peristalsis has begun to move food through the intestines (Peper et al., 2016). For a detailed description see https://peperperspective.com/2016/04/26/allow-natural-breathing-with-abdominal-muscle-biofeedback-1-2/

What can you do to reduce IBS

There are many factors that cause and effect IBS, some of which we have control over and some which are our out of our control, such as genetics. The purpose of proposed suggestions is to focus on those things over which you have control and reduce risk factors that negatively affect the gastrointestinal track. Generally, begin by integrating self-healing strategies that promote health which have no negative side effects before agreeing to do more aggressive pharmaceutical or even surgical interventions which could have negative side effects. Along the way, work collaboratively with your health care provider. Experiment with the following:

- Avoid food and drinks that may irritate the gastrointestinal tract. These include coffee, hot spices, dairy products, wheat and many others. If you are not sure whether you are reacting to a food or drink, keep a detailed log of what you eat and drink and how you feel. Do self-experimentation by eating or drinking the specific food by itself as the first food in the morning. Then observe how you feel in the next two hours. If possible, eat only organic foods that have not been contaminated by herbicides and pesticides (see: https://peperperspective.com/2015/01/11/are-herbicides-a-cause-for-allergies-immune-incompetence-and-adhd/).

- Identify and resolve stressors, conflicts and problems that negatively affect you and drain your energy. Keep a log to identify situations that drain or increase your subjective energy. Then do problem solving to reduce those situations that drain your energy and increase those situations that increase your energy. For a detailed description of the practice see https://peperperspective.com/2012/12/09/increase-energy-gains-decrease-energy-drains/

Often the most challenging situations that we cannot stomach are those where we feel defeated, helpless, hopeless and powerless or situations where we feel threatened– we do not feel safe. Reach out to other both friends and social services to explore how these situations can be resolved. In some cases, there is nothing that can be done except to accept what is and go on.

- Feel safe. As long as we feel unsafe, we have to be vigilant and are stressed which affects the GI track. Explore the following:

- What does safety mean for you?

- What causes you to feel unsafe from the past or the present?

- What do you need to feel safe?

- Who can offer support that you feel safe?

Reflect on these questions and then explore and implement ways by which you can create feeling more safe.

- Take breaks to regenerate. During the day, at work and at home, monitor yourself. Are you pushing yourself to complete tasks. In a 24/7 world with many ongoing responsibilities, we are unknowingly vigilant and do not allow ourselves to rest and relax to regenerate. Do not wait till you feel tired or exhausted. Stop earlier and take a short break. The break can be a short walk, a cup of tea or soup, or looking outside at a tree. During this break, think about positive events that have happened or people who love you and for whom you feel love. When you smile and think of someone who loves you, such as a grandparent, you may relax and for that moment as you feel safe which allows regeneration to begin.

- Observe how you inhale. Take a deep breath. If you feel you are moving upward and becoming a little bit taller, your breathing is wrong. Put one hand on your lower abdomen and the other on your chest and take a deep breath. If you observe your chest lifted upward and stomach did not expand, your breathing is wrong. You are not breathing diaphragmatically. Watch the following video, The correct way to breathe in, on how to observe your breathing and how to breathe diaphragmatically.

- Learn diaphragmatic breathing. Take time to practice diaphragmatic breathing. Practice while lying down and sitting or standing. Let the breathing rate slow down to about six breaths per minute. Exhale to the count of four and then let it trail off for two more counts, and inhale to the count of three and let it trail for another count. Practice this sitting and lying down (for more details on breathing see: https://peperperspective.com/2014/09/11/a-breath-of-fresh-air-improve-health-with-breathing/.

- Sitting position. Exhale by feeling your abdomen coming inward slightly for the count of four and trailing off for the count of two, then allow the lower ribs to widen, abdomen expand–the whole a trunk expands–as you inhale while the shoulders stay relaxed for a count of three. Allow it to trail off for one more count before you again begin to exhale. Be gentle, do not rush or force yourself. Practice this slower breathing for five minutes. Focus more on the exhalation and allowing the air to just flow in. Give yourself time during the transition between inhalation and exhalation.

- Lying down position. While lying on your back, place a two to five-pound weight such as a bag of rice on your stomach as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Lying down and practicing breathing with two to five-pound weight on stomach (reproduced by permission from Gorter and Peper, 2011.

As you inhale push the weight upward and also feel your lower ribs widen. Then allow exhalation to occur by the weight pushing the abdominal content down which pushes the diaphragm upward. This causing the breath to flow out. As you exhale, imagine the air flowing out through your legs as if there were straws inside your legs. When your attention wanders, smile and bring it back to imagining the air flowing down your legs during exhalation. Practice this for twenty minutes. Many people report that during the practice the gurgling in their abdomen occurs which is a sign that peristalsis and healing is returning.

- Observe and change your breathing during the day. Observe your breathing pattern during the day. Each time you hold your breath, gasp or breathe in your chest, interrupt the pattern and substitute slow diaphragmatic breathing for the next five breaths. Do this the whole day long. Many people observe that when they think of stressor or are worried, they hold their breath or shallow breathe in the chest. If this occurs, acknowledge the worry and focus on changing your breathing. This does not mean that you dismiss the concern, instead for this moment you focus on breathing and then explore ways to solve the problem.

If you observed that under specific circumstance you held your breath or breathed shallowly in your chest, then whenever you anticipate that the same event will occur again, begin to breathe diaphragmatically. To do this consistently is very challenging and most people report that initially they only seem to breathe incorrectly. It takes practice, practice and practice—mindful practice– to change. Yet those who continue to practice often report a decrease in symptoms and feel more energy and improved quality of life.

Summary

Changing habitual health behaviors such as diet and breathing can be remarkably challenging; however, it is possible. Give yourself enough time, and practice it many times until it becomes automatic. It is no different from learning to play a musical instrument or mastering a sport. Initially, it feels impossible, and with lot of practice it becomes more and more automatic. We continue to be impressed that healing is possible. Among our students at San Francisco State University, who practice their self-healing skills for five weeks, approximately 80% report a significant improvement in their health (Peper et al., 2014).

* This blog was adapted and expanded from: Peper, E., Mason, L., & Huey, C. (2017). Healing irritable bowel syndrome with diaphragmatic breathing. Biofeedback. 45(4), 83-87. DOI: 10.5298/1081-5937-45.4.04 https://biofeedbackhealth.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/a-healing-ibs-published.pdf

References

Chey, W. D., Kurlander, J., & Eswaran, S. (2015). Irritable bowel syndrome: a clinical review. Jama, 313(9), 949-958.

Chitkara, D. K., Rawat, D. J., & Talley, N. J. (2005). The epidemiology of childhood recurrent abdominal pain in Western countries: a systematic review. American journal of Gastroenterology, 100(8), 1868-1875.

Dupont, H. L. (2014). Review article: evidence for the role of gut microbiota in irritable bowel syndrome and its potential influence on therapeutic targets. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics, 39(10), 1033-1042.

Gibney, H.K. & Peper, E. (2003). Taking control: Strategies to reduce hot flashes and premenstrual mood swings. Biofeedback, 31(3), 20-24.

Gorter, R. & Peper, E. (2011). Fighting Cancer-A NonToxic Approach to Treatment. Berkeley: North Atlantic.

Peper, E., Booiman, A., Lin, I-M, Harvey, R., & Mitose, J. (2016). Abdominal SEMG Feedback for Diaphragmatic Breathing: A Methodological Note. Biofeedback. 44(1), 42-49.

Peper, E., Lin, I-M, Harvey, R., Gilbert, M., Gubbala, P., Ratkovich, A., & Fletcher, F. (2014). Transforming chained behaviors: Case studies of overcoming smoking, eczema and hair pulling (trichotillomania). Biofeedback, 42(4), 154-160.

Sapolsky, R. (2004). Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers. New York: Owl Books

Sowder, E., Gevirtz, R., Shapiro, W., & Ebert, C. (2010). Restoration of vagal tone: a possible mechanism for functional abdominal pain. Applied psychophysiology and biofeedback, 35(3), 199-206.

Vlieger, A. M., Blink, M., Tromp, E., & Benninga, M. A. (2008). Use of complementary and alternative medicine by pediatric patients with functional and organic gastrointestinal diseases: results from a multicenter survey. Pediatrics, 122(2), e446-e451.

Freeing the neck and shoulders*

Posted: April 6, 2017 Filed under: Neck and shoulder discomfort, self-healing, Uncategorized | Tags: computer, flexibility, Holistic health, neck pain, relaxation, repetitive strain injurey, shoulder pain, somatic practices, stress 4 CommentsStress, incorrect posture, poor vision and not knowing how to relax may all contribute to neck and shoulder tension. More than 30% of all adults experience neck pain and 45% of girls and 19% of boys 18 year old, report back, neck and shoulder pain (Cohen, 2015; Côté, Cassidy, & Carroll, 2003; Hakala, Rimpelä, Salminen, Virtanen, & Rimpelä, 2002). Shoulder pain affects almost a quarter of adults in the Australian community (Hill et al, 2010). Most employees working at the computer experience neck and shoulder tenderness and pain (Brandt et al, 2014), more than 33% of European workers complained of back-ache (The European Agency for Safety and Health at Work, 2004), more than 25% of Europeans experience work-related neck-shoulder pain, and 15% experience work-related arm pain (Blatter & De Kraker, 2005; Eijckelhof et al, 2013), and more than 90% of college students report some muscular discomfort at the end of the semester especially if they work on the computer (Peper & Harvey, 2008).

The stiffness in the neck and shoulders or the escalating headache at the end of the day may be the result of craning the head more and more forward or concentrating too long on the computer screen. Or, we are unaware that we unknowingly tighten muscles not necessary for the task performance—for example, hunching our shoulders or holding our breath. This misdirected effort is usually unconscious, and unfortunately, can lead to fatigue, soreness, and a buildup of additional muscle tension.

The stiffness in the neck and shoulders or the escalating headache at the end of the day may be the result of craning the head more and more forward or concentrating too long on the computer screen. Poor posture or compromised vision can contribute to discomfort; however, in many cases stress is major factor. Tightening the neck and shoulders is a protective biological response to danger. Danger that for thousands of years ago evoke a biological defense reaction so that we could run from or fight from the predator. The predator is now symbolic, a deadline to meet, having hurry up sickness with too many things to do, anticipating a conflict with your partner or co-worker, worrying how your child is doing in school, or struggling to have enough money to pay for the rent.

Mind-set also plays a role. When we’re anxious, angry, or frustrated most of us tighten the muscles at the back of the neck. We can also experience this when insecure, afraid or worrying about what will happen next. Although this is a normal pattern, anticipating the worst can make us stressed. Thus, implement self-care strategies to prevent the occurrence of discomfort.

What can you do to free up the neck and shoulder?

Become aware what factors precede the neck and shoulder tension. For a week monitor yourself, keep a log during the day and observe what situations occur that precede the neck and should discomfort. If the situation is mainly caused by:

- Immobility while sitting and being captured by the screen. Interrupt sitting every 15 to 20 minutes and move such as walking around while swinging your arms.

- Ergonomic factors such as looking down at the computer or laptop screen while working. Change your work environment to optimize the ergonomics such as using a detached keyboard and raising the laptop screen so that the top of the screen is at eyebrow level.

- Emotional factors. Learn strategies to let go of the negative emotions and do problem solving. Take a slow deep breath and as you exhale imagine the stressor to flow out and away from you. Be willing to explore and change ask yourself: “What do I have to have to lose to change?”, “Who or what is that pain in my neck?”, or “What am I protecting by being so rigid?”

Regardless of the cause, explore the following five relaxation and stretching exercises to free up the neck and shoulders. Be gentle, do not force and stop if your discomfort increases. When moving, continue to breathe.

1. WIGGLE. Wiggle and shake your body many times during the day. The movements can be done surreptitiously such as, moving your feet back and forth in circles or tapping feet to the beat of your favorite music, slightly arching or curling your spine, sifting the weight on your buttock from one to the other, dropping your hands along your side while moving and rotating your fingers and wrists, rotating your head and neck in small unpredictable circles, or gently bouncing your shoulders up and down as if you are giggling. Every ten minutes, wiggle to facilitate blood flow and muscle relaxation.

2. SHAKE AND BOUNCE. Stand up, bend your knees slightly, and let your arms hang along your trunk. Gently bounce your body up and down by bending and straightening your knees. Allow the whole body to shake and move for about one minute like a raggedy Ann doll. Then stop bouncing and alternately reach up with your hand and arm to the ceiling and then let the arm drop. Be sure to continue to breathe.

3. ROTATION MOVEMENT (Adapted from the work by Sue Wilson and reproduced by permission from: Gorter, R. & Peper, E. (2011). Fighting Cancer- A Nontoxic Approach to Treatment).

Pre-assessment: Stand up and give yourself enough space, so that when you lift your arms to shoulder level and rotate, you don’t touch anything. Continue to stand in the same spot during the exercise as shown in figures 1a and 1b.

Lift your arms and hold them out, so that they are at shoulder level, positioned like airplane wings. Gently rotate your arms to the left as far as you can without discomfort. Look along your left arm to your fingertips and beyond to a spot on the wall and remember that spot. Rotate back to center and drop your arms to your sides and relax.

Figures 1a and 1b. Rotating the arms as far as is comfortable (photos by Jana Asenbrennerova)

Figures 1a and 1b. Rotating the arms as far as is comfortable (photos by Jana Asenbrennerova)

Movement practice. Again, lift your arms to the side so that they are like airplane wings pointing to the left and right. Gently rotate your trunk, keeping your arms fixed at a right angle to your body. Rotate your arms to the right and turn your head to the left. Then reverse the direction and rotate your arms in a fixed position to the left and turn your head to the right. Do not try to stretch or push yourself. Repeat the sequence three times in each direction and then drop your arms to your sides and relax.

With your arms at your sides, lift your shoulders toward your ears while you keep your neck relaxed. Feel the tension in your shoulders, and hold your shoulder up for five seconds. Let your shoulders drop and relax. Then relax even more. Stay relaxed for ten seconds.

Repeat this sequence, lifting, dropping, and relaxing your shoulders two more times. Remember to keep breathing; and each time you drop your shoulders, relax even more after they have dropped.

Repeat the same sequence, but this time, very slowly lift your shoulders so that it takes five seconds to raise them to your ears while you continue to breathe. Keep relaxing your neck and feel the tension just in your shoulders. Then hold the tension for a count of three. Now relax your shoulders very slowly so that it takes five seconds to lower them. Once they are lowered, relax them even more and stay relaxed for five seconds. Repeat this sequence two more times.

Now raise your shoulders quickly toward your ears, feel the tension in your upper shoulders, and hold it for the count of five. Let the tension go and relax. Just let your shoulders drop. Relax, and then relax even more.

Post-assessment. Lift your arms up to the side so that they are at shoulder level and are positioned like airplane wings. Gently rotate without discomfort to the left as far as you can while you look along your left arm to your fingers and beyond to a spot on the wall.

Almost everyone reports that when they rotate the last time, they rotated significantly further than the first time. The increased flexibility is the result of loosening your shoulder muscles.

4. TAPPING FEET (adapted from the work of Servaas Mes)

Diagonal movements underlie human coordination and if your coordination is in sync, this will happen as a reflex without thought. There are many examples of these basic reflexes, all based on diagonal coordination such as arm and leg movement while walking. To restore this coordination, we use exercises that emphasize diagonal movements. This will help you reverse unnecessary tension and use your body more efficiently and thereby reducing “sensory motor amnesia” and dysponesis (Hanna, 2004). Remember to do the practices without straining, with a sense of freedom, while you continue relaxed breathing. If you feel pain, you have gone too far, and you’ll want to ease up a bit. This practice offers brief, simple practices to avoid and reverse dysfunctional patterns of bracing and tension and reduce discomfort. Practicing healthy patterns of movement can reestablish normal tone and reduce tension and pain. This is a light series of movements that involve tapping your feet and turning your head. You’ll be able to do the entire exercise in less than twenty seconds.

Pre-assessment. Sit erect at the edge of the chair with your hands on your lap and your feet shoulders’ width apart, with your heels beneath your knees.

First, notice your flexibility by gently rotating your head to the right as far as you can. Now look at a spot on the wall as a measure of how far you can comfortably turn your head and remember that spot. Then rotate back to the center.

Practicing rotating feet and head. Become familiar with the feet movement, lift the balls of your feet so your feet are resting on your heels. Lightly pivot the balls of your feet to the right, tap the floor, and then stop and relax your feet for just a second. Now lift the balls of your feet, pivot your feet to the left, tap, relax, and pivot back to the right.

Just let your knees follow the movement naturally. This is a series of ten light, quick, relaxed pivoting movements—each pivot and tap takes only about one or two seconds.

Add head rotation. Turn your head in the opposite direction of your feet. This series of movements provides effortless stretches that you can do in less than half a minute as shown in figures 2a and 2b.

Figures 2a and 2b. Rotating the feet and head in opposite directions (photos by Gary Palmer)

Figures 2a and 2b. Rotating the feet and head in opposite directions (photos by Gary Palmer)

When you’re facing right, move your feet to the left and lightly tap. Then face left and move your feet to the right and tap.

- Continue the tapping movement, but each time pivot your head in the opposite direction. Don’t try to stretch or force the movement.

- Do this sequence ten times. Now stop, face straight head, relax your legs, and just keep breathing.

Post assessment. Rotate your head to the right as far as you can see and look at a spot on the wall. Notice how much more flexibility/rotation you have achieved.

Almost everyone reports being able to rotate significantly farther after the exercise than before. They also report that they have less stiffness in their neck and shoulders.

5. SHOULDER AWARENESS PRACTICE. Sit comfortably with your hands on your lap. Allow your jaw to hang loose and breathe diaphragmatically. Continue to breathe slowly as you do the following:

- Shrug, raising your shoulders towards your ears to 70% of maximum effort and hold them up for about 10 seconds (note the sensations of tension).

- Let your shoulders drop and relax for 10 to 20 seconds

- Shrug, raising your shoulders towards your ears to 50% of maximum effort and hold them up for about 10 seconds (note the sensations of tension).

- Let your shoulders drop and relax for 10 to 20 seconds

- Shrug, raising your shoulders towards your ears to 25% of maximum effort and hold them up for about 10 seconds (note the sensations of tension).

- Let your shoulders drop and relax for 10 to 20 seconds

- Shrug, raising your shoulders towards ears to 5% of maximum effort and hold them up for about 10 seconds (note the sensations of tension).

- Let your shoulders drop and relax for 10 to 20 seconds

- Pull your shoulders down to 25% of maximum effort and hold them up for about 10 seconds (note the sensations of tension).

- Allow your shoulders to come back up and relax for 10 to 20 seconds

Remember to relax your shoulders completely after each incremental tightening. If you tend to hold your breath while raising your shoulders, gently exhale and continue to breathe. When you return to work, check in occasionally with your shoulders and ask yourself if you can feel any of the sensations of tension. If so, drop your shoulders and relax for a few seconds before resuming your tasks.

In summary, when employees and students change their environment and integrate many movements during the day, they report a significant decrease in neck and shoulder discomfort and an increase in energy and health. As one employee reported, after taking many short movement breaks while working at the computer, that he no longer felt tired at the end of the day, “Now, there is life after five”.

To explore how prevent and reverse the automatic somatic stress reactions, read Thomas Hanna‘s book, Somatics: Reawakening The Mind’s Control of Movement, Flexibility, and Health. For easy to do neck and shoulder guided instructions stretches, see the following ebsite: http://greatist.com/move/stretches-for-tight-shoulders

References:

Blatter, B. M., & Kraker, H. D. (2005). Prevalentiecijfers van RSI-klachten en het vóórkomen van risicofactoren in 15 Europese landen. Tijdschrift voor gezondheidswetenschappen, 1, 83, 8-15.

Côté, P., Cassidy, J. D., & Carroll, L. (2003). The epidemiology of neck pain: what we have learned from our population-based studies. The Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association, 47(4), 284. http://www.pain-initiative-un.org/doc-

European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (2004). http://europa.eu.int/comm/employment_social/news/2004/nov/musculoskeletaldisorders_en.html

Paoli, P., Merllié, D., & Fundação Europeia para a Melhoria das Condições de Vida e de Trabalho. (2001). Troisième enquête européenne sur les conditions de travail, 2000.

*I thank Sue Wilson and Servaas Mes for teaching me these somatic practices.

How to stay safe when pulled over by the police

Posted: September 25, 2016 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: health, police, safety, stress, violence 1 CommentAn officer and suspect interaction is fraught with danger especially if the police anticipate DANGER. The interaction may trigger an evolutionary based defense reaction that may mean that our analytical reflective thinking fades out and we focus only on immediate survival. You may interpret any cues as potentially dangerous and that your life could be in danger. At that point the information is not processed rationally; since, it reaches the amygdala 22 milliseconds faster than to the cortex where thinking would take place. You react instead of act!

Adapted from: Ropeik, D. (2011). How Risky Is It, Really? Why our fears don’t always match the facts. New York: McGraw Hill

We all have experienced this automatic response. Remember when you were pissed off and angry at a close family member or friend? In the heat of the argument (or was it the battle for survival?), you said something that was cruel and painful–a real zinger. As the words left your mouth, you realized that you should not have said what you said. You wished you could reel the words back. Immediately you know that this would be very difficult to repair. At that moment, you reacted in self-defense from the amygdala before the cortex was aware.

Similarly, an officer and you may react automatically without thinking when they perceive personal danger. How you behave and move could automatically signal DANGER or SAFETY to the officer . To deescalate the situation when stopped by the police, behave in a way that signals to the officers that you are NOT a danger to them.

I highly recommend the short YouTube video by country singer, Coffey Anderson, Stop the Violence Safety Video for when you get pulled over by the Police. They share, what to do actually when you get pulled over by the police? It offers strategies to help diffuse tension at traffic stop, it gives solid steps into ways of staying safe, and getting home. SHARE this. It’s a must for all to see. If you have the opportunity, role-play the situation with your friends so that it becomes your new automatic response.

The video is on YouYube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MnoLAtu0Wjk

Do medications work as promised? Ask questions!

Posted: January 13, 2016 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: antidepressants, medication, opiod, pharmaceuticals, risk-benefit, side effects, stress Leave a commentMedications can be beneficial and safe lives; however, some may not work as well as promised. In some cases, they may do more harm than good as illustrated by the following examples.

- There is weak or no evidence of effectiveness for the long term use of any opiod (morphine, fentanyl, oxycodone, methadone and hydrocodone) in the treatment of chronic pain (Perlin, 2015). As the Center for Disease Control and Prevention reports, “Since 1999, the amount of prescription painkillers prescribed and sold in the U.S. has nearly quadrupled, yet there has not been an overall change in the amount of pain that Americans report. Over prescribing leads to more abuse and more overdose deaths.” More than 16,000 people a year die from prescription drug overdose (CDC, 2016). For a superb discussion of the treatment of chronic pain, see the recently published book by Cindy Perlin, The truth about chronic pain treatments.

- Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitor such as Paxil and Prozac (SSRI) are much less effective than promised by pharmaceutical companies. When independent researchers (not funded by pharmaceutical companies) re-analyzed the data from published and unpublished the studies, they found that the medication was no more effective than the placebo for the treatment of mild and moderate depression (Ioannidis, 2008; Le Noury et al, 2015). In addition, the SSRIs (paroxetine and Imipramine) in treatment of unipolar major depression in adolescence may cause significant harm which outweigh any possible benefits (Le Le Noury et al., 2015). On the other had, exercise appears as effective as antidepressants for reducing symptoms of mild to moderate depression (Cooney et al., 2013). Despite the questionable benefits of SSRI medications, pharmaceutic industry to posted $11.9 billion dollars in 2011 global sales (Perlin, 2015).

When medications are recommended, ask your provider the following questions (Robin, 1984; Gorter & Peper, 2011).

- Why are you prescribing the medication?

- What are the risks and negative side effects?

- Do the benefits outweigh the risks?

- How do I know when the medication is working?

- What will you do if the medication does not work?

- How many patients do you need to treat before one patient benefits?

- Can you recommend non-pharmaceutical options?

The important questions to ask are:

- How many patients need to be treated with the medication before one patient benefits?

- How many will experience negative side effects?

The data can be discouraging. As Daniel Levitin, neuroscientist at McGill University in Montreal and Dean at Minerva Schools in San Francisco, points out, it takes 300 people to take statins for one year before one heart attack, stroke or other serious event is prevented. However, 5% of all the people taken statins (the of drug of choice to lower cholesterol) will experience debilitating adverse effects such as severe muscle pain and gastrointestinal disorders. This means that you are 15 times more likely to suffer serious side effect than being helped by the drug. Nevertheless, the CDC reported that during 2011–2012, more than one-quarter (27.9%) of adults aged 40 and over used a prescription cholesterol-lowering medication (statins) (Gu, 2014).

Before making any medical decision when stressed, watch the superb 2015 TED London presentation by neuroscientist Daniel Levitin, How to think about making a decision under stress.

Reference:

CDC Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2016). Injury prevention & control: Prescription drug overdose. http://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/

Cooney, G.M., Dwan, K., Greig, C.A., Lawlor, D.A, Rimer, J., Waugh, F.R., McMurdo, M., & Mead, G. E.(2013). Exercise for depression. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 9. Art. No.: CD004366. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004366.pub6.The Cochrane Library. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD004366.pub6/epdf

Goter, R. & Peper, E. (2011). Fighting cancer: A nontoxic approach to treatment. Berkeley, CA: Noreth Atlantic Books.http://www.amazon.com/Fighting-Cancer-Nontoxic-Approach-Treatment/dp/1583942483/ref=sr_1_2_twi_pap_2?ie=UTF8&qid=1452715134&sr=8-2&keywords=gorter+and+peper

Gu, Q., Paulose-Ram, R., Burt, V.L., & Kit, B.K. (2014).Prescription Cholesterol-Lowering Medication Use in Adults Aged 40 and Over: United States, 2003–2012. NCHS Data Brief No. 177. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics.http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db177.pdf

Ioannidis, J. P. (2008). Effectiveness of antidepressants: an evidence myth constructed from a thousand randomized trials?. Philosophy, Ethics, and Humanities in Medicine, 3(1), 14. http://peh-med.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1747-5341-3-14

Le Noury, J., Nardo, J. M., Healy, D., Jureidini, J., Raven, M., Tufanaru, C., & Abi-Jaoude, E. (2015). Restoring Study 329: efficacy and harms of paroxetine and imipramine in treatment of major depression in adolescence. http://www.bmj.com/content/351/bmj.h4320.full

Levitin, D. (2015). How to stay calm when you know you’ be stressed. TEDGlobal London Talk http://www.ted.com/talks/daniel_levitin_how_to_stay_calm_when_you_know_you_ll_be_stressed

Perlin, C. (2015). The truth about chronic pain treatments. Delmar, NY: Morning Light Books, LLC. http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B0160UEQB2/ref=dp-kindle-redirect?ie=UTF8&btkr=1

Robin, E.D. (1984). Matters of life & death: Risks vs. benefits of medical care. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company. http://www.amazon.com/Matters-Life-Death-Benefits-Medical/dp/071671681X/ref=tmm_pap_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=&sr=

Porges and Peper Propose Physiological Basis for Paralysis as Reaction to Date Rape

Posted: May 24, 2015 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: assault, immobilization, polyvagal theory, psychophysiology, rape, stress 1 CommentParalysis Can Be a Natural Reaction to Date rape

This is the press release for my recently published article in the journal, Biofeedback, coauthored with Stephen Porges,

Stigma is often associated with inaction during a crisis. Those who freeze in the face of a life-threatening situation often experience feelings of shame and guilt, and they often feel that they are constantly being judged for their inaction. While others may confidently assert that they would have been more “heroic” in that situation, there is a far greater chance that their bodies would have reacted in exactly the same way, freezing as an innate part of self-preservation.

Stephen Porges and Erik Peper describe how immobilization is a natural neurobiological response to being attacked as can occur during date rape.in the article titled “When Not Saying NO Does Not Mean Yes: Psychophysiological Factors Involved in Date Rape,” published in the journal Biofeedback .

The article explains the immobilization response in light of the polyvagal theory, which Porges introduced about 20 years ago. According to this theory, the brain reacts to various risk situations in three ways: The situation is safe, the situation is dangerous, or the situation is life-threatening. After our brain identifies risk, our body reacts either with a fight-or-flight response or, especially in dire situations, can become completely immobilized. The likelihood of an immobilization response increases when the person is physically restrained or is in a confined environment. Immobilization is also often accompanied by a higher pain threshold and a tendency to disassociate.

In the case of rape, it is often assumed that the victim should simply have said No, should have fought back, or should have made it clear that the sexual attention was unwanted. However, the more we learn about the brain’s response to extreme threats, the more we realize that it may be difficult to recruit the neural circuits necessary to verbally express oneself or to fight or flee, especially when drugs or alcohol are involved. Instead, it is a natural response for victims to freeze, to feel so physically threatened that their own body will not allow them to fight or flee.

Porges and Peper note that polyvagal theory supports a law passed in California in September 2014. The new law requires the governing boards of the state’s colleges and universities to adopt policies and procedures that require students who engage in sexual activity to obtain “affirmative, unambiguous, and conscious decision by each participant.” In other words, simply not saying No will no longer be tolerated as an excuse for rape.

The article conclude that victims of date rape should not feel shame or guilt if they froze in that situation. The body’s natural defense reactions are not just flight or fight; sometimes it is complete immobilization.

The authors hope that recognizing this will help people deal with trauma and help those around them understand their experiences. After a lecture, one of the authors, Peper, had a profound experience when a student came up to him with tears in her eyes. She explained that the same immobilization process happened to her two weeks before when she was robbed and she had felt so guilty.` Just listening to her made the efforts of writing the article worthwhile.”

Full text of the article, “When Not Saying NO Does Not Mean Yes: Psychophysiological Factors Involved in Date Rape,” Biofeedback, Vol. 43, No. 1, 2015, is available at https://biofeedbackhealth.files.wordpress.com/2011/01/porges-and-peper-date-rape.pdf

About the journal Biofeedback

Biofeedback is published four times per year and distributed by the Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. The chief editor of Biofeedback is Donald Moss, Dean of Saybrook University’s School of Mind-Body Medicine. AAPB’s mission is to advance the development, dissemination, and utilization of knowledge about applied psychophysiology and biofeedback to improve health and the quality of life through research, education, and practice.

Media Contact:

Bridget Lamb

Allen Press, Inc.

800/627-0326 ext. 248

blamb@allenpress.com

What do numbers mean? How much does Walmart’s wage raise affect profits?

Posted: February 22, 2015 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: economics, salaries, stress 1 Comment Walmart created news when it announced that it will be paying its 500,000 employees more than the minimum wage. The largest increase would be an increase of the entry-level wage from the US minimum $7.25 to $9 an hour; howver, the overall increase in minimal. As Jody Knauss and Mary Bottari point out, The company forecasts the average hourly wage for full-time workers to rise 15 cents an hour, from $12.85 to $13.00, while the average for part-timers will bump up from $9.48 to $10.00 per hour. This will still still leave most of its workers beneath the poverty level and relying on food stamps to make ends meet.

Walmart created news when it announced that it will be paying its 500,000 employees more than the minimum wage. The largest increase would be an increase of the entry-level wage from the US minimum $7.25 to $9 an hour; howver, the overall increase in minimal. As Jody Knauss and Mary Bottari point out, The company forecasts the average hourly wage for full-time workers to rise 15 cents an hour, from $12.85 to $13.00, while the average for part-timers will bump up from $9.48 to $10.00 per hour. This will still still leave most of its workers beneath the poverty level and relying on food stamps to make ends meet.