Playful practices to enhance health with biofeedback

Posted: May 4, 2024 Filed under: attention, behavior, biofeedback, Breathing/respiration, computer, Exercise/movement, health, Neck and shoulder discomfort, Pain/discomfort, self-healing, Uncategorized | Tags: exercise, Feldenkrais, pain, Play, somatics Leave a commentAdapted from: Gibney, K.H. & Peper, E. (2003). Exercise or play? Medicine of fun. Biofeedback, 31(2), 14-17.

Homework assignments are sometimes viewed as chore and one more thing to do. Changing the perception from that of work to fun by encouraging laughter and joy often supports the healing process. This blog focusses on utilizing childhood activities and paradoxical movement to help clients release tension patterns and improve range of motion. A strong emphasis is placed on linking diaphragmatic breathing to movement.

When I went home I showed my granddaughter how to be a tree swaying in the wind, she looked at me and said, “Grandma, I learned that in kindergarten!”

‘Betty’ laughed heartily as she relayed this story. Her delight in being able to sway her arms like the limbs of a tree starkly contrasted with her demeanor only a month prior. Betty was referred for biofeedback training after a series of 9 surgeries – wrists, fingers, elbows and shoulders. She arrived at her first session in tears with acute, chronic pain accompanied by frequent, incapacitating spasms in her shoulders and arms. She was unable to abduct her arms more than a few inches without triggering more painful spasms. Her protective bracing and rapid thoracic breathing probably exacerbated her pain and contributed to a limited range of motion of her arms. Unable to work for over a year, she was coping not only with pain, but also with weight gain, poor self-esteem and depression.

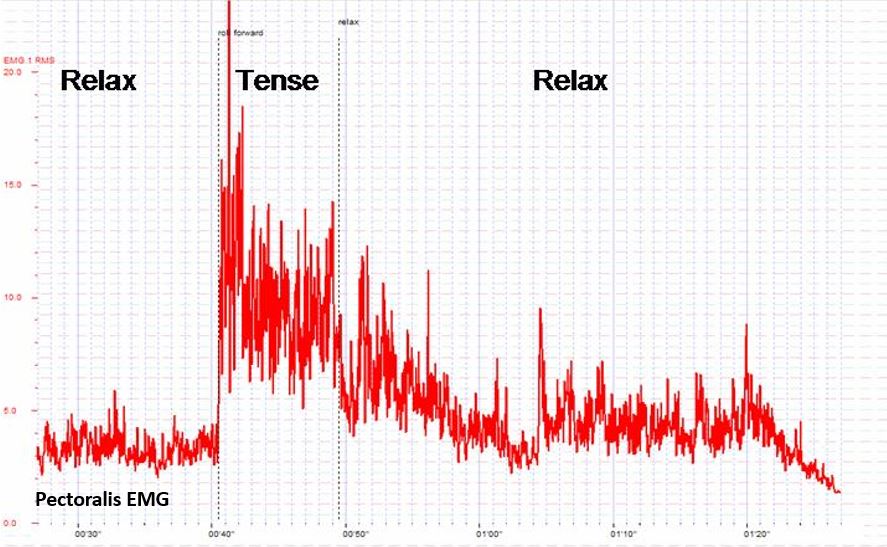

The biofeedback training began with effortless, diaphragmatic breathing which is often the foundation of health (Peper and Gibney, 1994). Each thoracic breath added to Betty’s chronic shoulder pain. Convincing Betty to drop her painful bracing pattern and to allow her arms to hang freely from her shoulders as she breathed diaphragmatically was the first major step in regaining mobility. She discovered in that first session that she could use her breathing to achieve control over muscle spasms when she initiated the movement during the exhalation phase of breathing as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Initiate the physical activity after exhaling has begun and body is relaxing especially if the movement or procedure such as an injection would cause pain. Pause the movement when inhaling and then continue the movement again during the exhalation phase. The simple rule is to initiate the activity slightly after beginning exhaling and when the heart rate started to decrease (reproduced with permission from Gorter & Peper, 2012).

During the first week, she practiced her breathing assiduously at home and had fewer spasms. Betty was able to move better during her physical therapy sessions. Each time she felt the onset of muscle spasms she would stop all activity for a moment and ‘go into my trance’ to prevent a recurrence. For the first time in many months, she was feeling optimistic.

Subsequent sessions built upon the foundation of diaphragmatic breathing: boosting Betty’s confidence, increasing range of motion (ROM), and bringing back some fun in life. Activities included many childhood games: tossing a ball, swaying like a tree in the wind, pretending to conduct an orchestra, bouncing on gym balls, playing “Simon Says” (following the movements of the therapist), and dancing. Laughter and childlike joy became a common occurrence. She looked forward to receiving the sparkly star stickers she was given after successful sessions. With each activity, Betty gained more confidence, gradually increased ROM, and began losing weight. Although she had some days where the pain was strong and spasms threatened, Betty reframed the pain as occurring as a result of healing and expanding her ROM—she was no longer a victim of the pain. In addition, her family was proud of her, she was doing more fun activities, and she felt confident that she would return to work.

Betty’s story is similar to other clients whom we have seen. The challenge presented to therapists is to help the client better cope with pain, increase ROM, regain function and, often the most important, to reclaim a “joie de vivre”. Increasing function includes using the minimum amount of effort necessary for the task, allowing unnecessary muscles to remain relaxed (inhibition of dysponesis[i]), and quickly releasing muscle tension when the muscle is no longer required for the activity (work/rest) (Whatmore & Kohli, 1974; Peper et al, 2010; Sella, 2019). The challenge is to perform the task without concurrent evocation of components of the alarm reaction, which tend to be evoked when “we try to do it perfectly,” or “it has to work,” “If I do not do it correctly,” or “I will be judged.” For example, when people learn how to implement micro-breaks (1–2 second rest periods) at the computer, they often sit quietly believing that they are relaxed; however, they may continue a bracing pattern (Peper et al, 2006). Alternatively, tossing a small ball rather than resting at the keyboard will generally evoke laughter, encourage generalization of skills, and covertly induce more relaxation. In some cases, therapists in their desire to help clientss to get well assign structured exercises as homework that evoke striving for performance and boredom—this striving to perform the structured exercises may inhibit healing. Utilizing tools other than those found in the work setting helps the client achieve a broader perspective of the healing/preventive concepts that are taught.

To optimize success, clients are active participants in their own healing process which means that they learn the skills during the therapeutic session and practice at home and at work. Home practices are assigned to integrate the mastery of news skills into daily life. To help clients achieve increased health through physical activity three different approaches are often used: movement reeducation, youthful play, and pure exercise. How the client performs the activity may be monitored with surface electromyography (SEMG) to identify muscles tightening that are not needed for the task and how the muscle relaxes when not needed for the task performance. This monitoring can be done with a portable biofeedback device or multi-channel system when walking or performing the exercises. Clients can even use a single channel SEMG at home.

When working to improve ROM and physical function, explore the following:

- Maintain diaphragmatic breathing – rhythm or tempo may change but the breath must be generated from the diaphragm with emphasis on full exhalation. Use strain gauge feedback and/or SEMG feedback to monitor and train effortless breathing (Peper et al., 2016). Strain gauge feedback is used to teach a slower and diaphragmatic breathing pattern, while SEMG recorded from the scalene to trapezius is used to teach how to reduce shoulder and ancillary muscle tension during inhalation

- Perform activities or stretching/strengthening exercises so slowly that they don’t trigger or aggravate pain during the exhalation phase of breathing.

- Use the minimum amount of tension necessary for the task and let unnecessary muscles remain relaxed. Use SEMG feedback recorded from muscles not needed for the performance of the task to teach clients awareness of inappropriate muscle tension and to learn relaxation of those muscles.

- Release muscle tension immediately when the task is accomplished. Use SEMG feedback to monitor that the muscles are completely relaxed. If rapid relaxation is not achieved, first teach the person to relax the muscles before repeating the muscle activity.

- Perform the exercises as if you have never performed them and do them with a childlike, beginner’s mind, and exploratory attitude (Kabat-Zinn, 1990).

- Create exercises that are totally new and novel so that the participant has no expectancy of outcome can be surprised by their own experience. This approach is part of many somatic educational and therapeutic approaches such as Feldenkrais or Somatics (Hanna, 2004; Feldenkrais, 2009).

Movement and exercise can be taught as pure physical exercise, movement reeducation or youthful playing. Physical exercise is necessary for strength and endurance and at the same time, improves our mood (Thayer, 1996; Mahindru et al., 2023). However, many exercises are considered a burden and are often taught without a sense of lightness and fun, which results in the client thinking in terms that are powerless and helpless (depressive)—“I have to do them.” Helping your clients to understand that exercise is simply a part of every day life, that it encourages healing and improves health, and that they can “cheat” at it, may help them to reframe their attitudes toward it and accomplish their healing goals.

Pure Physical Exercise—Enjoyment through Strength and Flexibility

The major challenge of structured exercises is that the person is very serious and strives too hard to attain the goal. In the process of striving, the body is often held rigid: Breath is shallow and halted and shoulders are slightly braced. Maintaining a daily chart is an excellent tool to show improvement (e.g., more repetitions, more weight, increased flexibility; since, structured exercises are very helpful for improving ROM and strength. When using pure exercise, remember that injured person may have a sense of urgency – they want to get well quickly and, if work stress was a factor in developing pain, they often rush when they need to meet a deadline.

As much as possible make the exercise fun. Help the client understand that he/she can be quick while not rushed. For example, monitor SEMG from an upper trapezius muscle using a portable electromyography. For example, begin by walking slowly. Add a ramp or step to ensure that there is no bracing when climbing (a common occurrence). Walk around the room, down the hall, around the block. Maintain relaxed shoulders, an even swing of the arms, and diaphragmatic breathing. Walk more quickly while emphasizing relaxation with speed rather than rushing. Go faster and faster. Up the stairs. Down the stairs. Walk backward. Skip. Hop. Laugh.

Movement Reeducation – Be ‘Oppositional’ And Do It Differently

Movement reeducation, such as Feldenkrais, Alexander Technique or Hannah Somatics, involves conscious awareness of movement (Alexander, 2001; Hanna, 2004; Murphy, 1993). Many daily patterns of movement become imbedded in our consciousness and, over the years, may include a pain trigger. A common trigger is lifting the shoulders when reaching for the keyboard or mouse, people suffering from thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) often have such patterns (Peper & Harvey, 2021). A keyboard can often inadvertently cue the client to trigger this dysponetic, and frequently painful, pattern. Have the client do movement reeducation exercises as they are guided through practices in which they have no expectancy and the movements are novel. The focus is on awareness without triggering any fight/flight or startle responses.

Ask the client to explore performing many functional activities with the opposite hand, such as brushing his/her hair or teeth, eating, blowing his/her hair dry, or doing household chores, such as vacuuming. (Explore this for yourself, as well!). Be aware of how much shoulder muscle tension is needed to raise the arms for combing or blow-drying the hair. Explore how little effort is required to hold a fork or knife (you might want to do this in the privacy of your own home!).

Do movements differently such as, practicing alternating hands when leading with the vacuum or when sweeping, changing routes when driving/walking to work or the store, getting out of bed differently. Break up habitual conditioned reflex patterns such as eye, head and hand coordination. For example, slowly rotate your head from left to right and simultaneously shift your eyes in the opposite direction (e.g., turn your head fully to the right while shifting your eyes fully to the left, and then reverse) or before reaching forward, drop your elbows to your sides then, bend your elbows and touch your shoulders with your thumbs then, reach forward. Often, when we change our patterns we increase our flexibility, inhibit bracing and reduce discomfort.

Free Your Neck and Shoulders (adapted from a demonstration by Sharon Keane and developed by Ilana Rubenfeld, 2001)

–Push away from the keyboard and sit at the edge of the chair with your knees bent at right angles and your feet shoulder-width apart and flat on the floor. Do the following movements slowly. Do NOT push yourself if you feel discomfort. Be gentle with yourself.

–Look to the right and gently turn your head and body as far as you can go to the right. When you have gone as far as you can comfortably go, look at the furthest spot on the wall and remember that spot. Gently rotate your head back to center. Close your eyes and relax.

–Reach up with your left hand; pass it over the top of your head and hold on to your right ear. Then, gently bend to the left lowering your elbow towards the floor. Slowly straighten up. Repeat for a few times feeling as if you are a sapling flexing in the breeze. Observe what your body is doing as it bends and comes back up to center. Notice the movements in your ribs, back and neck. Then, drop your arm to your lap and relax. Make sure you continue to breathe diaphragmatically throughout the exercise.

–Reach up with your right hand and pass it over the top of your head and hold on to your left ear. Repeat as above except bending to the right.

–Reach up with your left hand and pass it over the top of your head and hold on to your right ear. Then, look to the left with your eyes and rotate your head to the left as if you are looking behind you. Return to center and repeat the movement a few times. Then, drop your arm to your lap and relax for a few breaths.

–Again, reach over your head with your left hand and hold onto your right ear. Repeat the same rotating motion of your head to the left except that your eyes look to the right. Repeat this a few times then, drop your arm to your lap and relax for a few breaths.

–Reach up with your right hand and pass it over the top of your head and hold on to your left ear. Then, look to the right with your eyes and rotate your head to the right as if you are looking behind you. Return to center and repeat a few times. Then, drop your arm to your lap and relax for a few breaths.

–Again, reach over your head with your right hand and hold onto your left ear. Repeat the same rotating motion of your head to the right except that your eyes look to the left. Repeat this a few times then, drop your arm to your lap and relax for a few breaths.

–Now, look to the right and gently turn your head and body as far as you can go. When you can not go any further, look at that point on the wall. Did you rotate further than at the beginning of the exercise?

–Gently rotate your head back to center, close your eyes, relax and notice the feeling in your neck, shoulders and back.

Youthful Playing – Pavlovian Practice

Evoking positive past memories and actually acting them out may enhance health as is illustrated by the recovery of serious illness of Ivan Pavlov, the discovery of classical conditioning. When Pavlov quietly lay in his hospital bed, many, including his family, thought he was slipping into death. He then ask the nurse to get him a bowl of water with earth in it and the whole night long he gently played with the mud. He recreated the experience when as a child he was playing in mud along a river’s bank. Pavlov knew that evoking the playful joy of childhood would help to encourage mental and physical healing. The mud in hands was the conditioned stimulus to evoke the somatic experience of wellness (Peper, Gibney, & Holt, 2002).

Having clients play can encourage laughter and joie de vivre, which may help in physical healing. Being involved in childhood games and actually playing these games with children removes one from worries and concerns—both past and future—and allows one to be simply in the present. Just being present is associated with playfulness, timelessness, passive attention, creativity and humor. A state in which one’s preconceived mental images and expectancies—the personal, familial, cultural, and healthcare provider’s hypnotic suggestions—are by-passed and for that moment, the present and the future are yet undefined. This is often the opposite of the client’s expectancy; since, remembering the past experiences and the diagnosis creates a fixed mental image that may expect pain and limitation.

Explore some of the following practices as strategies to increase movement and flexibility without effort and to increase joy. Use your creativity and explore your own permutations of the practices. Observe how your mood improves and your energy increases when you play a childhood game instead of an equivalent exercise. For example, instead of dropping your hands to your lap or stretching at the computer terminal during a micro- or meso-break[ii], go over to your coworker and play “pattycake.” This is the game in which you and your partner face each other and then clap your hands and then touch each other’s palms. Do this in all variations of the game.

For increased ROM in the shoulders explore some of the following (remember the basics: diaphragmatic breathing, minimum effort, rapid release) in addition, do the practices to the rhythm of the music that you enjoyed as a young person.

Ball Toss: a hand-sized ball that is easily squeezed is best for this exercise. Monitor respiration patterns, and SEMG forearm extensors and/or flexors, and upper trapezii muscles. Sit quietly in a chair and focus on a relaxed breathing rhythm. Toss the ball in the air with your right hand and catch it with your left hand. As soon as you catch the ball, drop both hands to your lap. Toss the ball back only when you achieve relaxation—both with the empty hand and the hand holding the ball. Watch for over-efforting in the upper trapezii. Begin slowly and increase the pace as you train yourself to quickly release unnecessary muscle tension. Go faster and faster (just about everyone begins to laugh, especially each time they drop the ball).

Ball Squeeze/Toss: Expand upon the above by squeezing the ball prior to tossing. When working with a client, call out different degrees of pressure (e.g., 50%, 10%, 80%, etc.). The same rules apply as with the ball toss.

Ball Hand to Hand: Close your eyes and hand the ball back and forth. Go faster and faster and add ball squeezes prior to passing the ball.

Gym Ball Bounces: Sit on a gym ball and find your balance. Begin bouncing slowly up and down. Reach up and lower your left then, right hand. Abduct your arms forward then, laterally. Turn on the radio and bounce to music.

Simon Says: This can be done standing, sitting in a chair or on a gym ball. When on a gym ball, bounce during the game. Have your client do a mirror image of your movements: reaching up, down, left, right, forward or backward. Touch your head, nose, knees or belly. Have fun and go more quickly.

Back-To-Back Massage: With a partner, stand back-to-back. Lean against each other’s back so that you provide mutual support. Then each rub your back against each other’s back. Enjoy the wiggling movement and stimulation. Be sure to continue to breathe.

Summary: An Attitude of Fun

In summary, it is not what you do; it is also the attitude by which you do it that affects health. From this perspective,when exercises are performed playfully, flexibility, movement and health are enhanced while discomfort is decreased. Inducing laughter promotes healing and disrupts the automatic negative hypnotic suggestion/self-images of what is expected. The clients begins to live in the present moment and thereby decreases the anticipatory bracing and dysponetic activity triggered by striving. By decreasing striving and concern for results, clients may allow themselves to perform the practices with a passive attentive attitude that may facilitate healing. For that moment, the client forgets the painful past and a future expectances that are fraught with promises of continued pain and inactivity. At moment, the pain cycle is interrupted which provides hope for a healthier future.

References

Alexander, F.M. (2001). The Use of the Self. London: Orion Publishing. https://www.amazon.com/Use-Self-F-M-Alexander/dp/0752843915

Feldenkrais, M. (2009). Awareness Through Movement Easy-to-Do Health Exercises to Improve Your Posture, Vision, Imagination, and Personal Awareness. New York: HarperOne. https://www.amazon.com/Awareness-Through-Movement-Easy-Do/dp/0062503227

Gibney, K.H. & Peper, E. (2003). Exercise or play? Medicine of fun. Biofeedback, 31(2), 14-17. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/380317304_EXERCISE_OR_PLAY_MEDICINE_OF_FUN

Gorter, R. & Peper, E. (2012). Fighting Cancer- A Nontoxic Approach to Treatment. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books. https://www.amazon.com/Fighting-Cancer-Nontoxic-Approach-Treatment/dp/1583942483

Hanna, T. (2004). Somatics: Reawakening The Mind’s Control Of Movement, Flexibility, And Health. Da Capo Press. https://www.amazon.com/Somatics-Reawakening-Control-Movement-Flexibility/dp/0738209570

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living. New York: Delacorte Press.

Mahindru, A., Patil, P., & Agrawal, V. (2023). Role of Physical Activity on Mental Health and Well-Being: A Review. Cureus, I5(1), e33475. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.33475

Murphy, M. (1993). The future of the body. New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Perigee. https://www.amazon.com/Future-Body-Explorations-Further-Evolution/dp/0874777305

Peper, E., Booiman, A., Lin, I-M, Harvey, R., & Mitose, J. (2016). Abdominal SEMG Feedback for Diaphragmatic Breathing: A Methodological Note. Biofeedback. 44(1), 42-49. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/300365890_Abdominal_SEMG_Feedback_for_Diaphragmatic_Breathing_A_Methodological_Note

Peper, E., Booiman, A., Tallard, M., & Takebayashi, N. (2010). Surface electromyographic biofeedback to optimize performance in daily life: Improving physical fitness and health at the worksite. Japanese Journal of Biofeedback Research, 37(1), 19-28. https://doi.org/10.20595/jjbf.37.1_19

Peper, E., Gibney, K. & Holt, C. (2002). Make health happen: Training yourself to create wellness. Dubuque, IA: Kendall-Hunt. https://he.kendallhunt.com/product/make-health-happen-training-yourself-create-wellness

Peper, E. & Harvey, R. (2021). Causes of TechStress and ‘Technology-Associated Overuse’ Syndrome and Solutions for Reducing Screen Fatigue, Neck and Shoulder Pain, and Screen Addiction. Townsend Letter-The examiner of Alternative Medicine, Oct 28, 2021. https://www.townsendletter.com/article/459-techstress-how-technology-is-hurting-us

Peper, E., Harvey, R. & Tylova, H. (2006). Stress protocol for assessing computer related disorders. Biofeedback. 34(2), 57-62. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242549995_FEATURE_Stress_Protocol_for_Assessing_Computer-Related_Disorders

Peper, E. & Tibbetts, V. (1994). Effortless diaphragmatic breathing. Physical Therapy Products. 6(2), 67-71. Also in: Electromyography: Applications in Physical Therapy. Montreal: Thought Technology Ltd. https://www.bfe.org/protocol/pro10eng.htm

Rubenfeld, I. (2001). The listening hands: Self-healing through Rubenfeld Synergy method of talk and touch. New York: Random House. https://www.amazon.com/Listening-Hand-Self-Healing-Through-Rubenfeld/dp/0553379836

Sella, G. E. (2019). Surface EMG (SEMG): A Synopsis. Biofeedback, 47(2), 36–43. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-47.1.05

Thayer, R.E. (1996). The origin of everyday moods—Managing energy, tension, and stress. New York: Oxford University Press. https://www.amazon.com/Origin-Everyday-Moods-Managing-Tension/dp/0195118057

Whatmore, G. and Kohli, D. The Physiopathology and Treatment of Functional Disorders. New York: Grune and Stratton, 1974. https://www.amazon.com/physiopathology-treatment-functional-disorders-biofeedback/dp/0808908510

[i] Dysponesis involves misplaced muscle activities or efforts that are usually covert and do not add functionally to the movement. From: Dys” meaning bad, faulty or wrong, and “ponos” meaning effort, work or energy (Whatmore and Kohli, 1974)

[ii] A meso-break is a 10 to 90 second break that consists of a change in work position, movement or a structured activity such as stretching that automatically relaxes those muscles that were previously activated while performing a task.

Quick Rescue Techniques When Stressed

Posted: February 4, 2024 Filed under: attention, behavior, biofeedback, Breathing/respiration, CBT, cognitive behavior therapy, education, emotions, Evolutionary perspective, Exercise/movement, health, mindfulness, Neck and shoulder discomfort, posture, relaxation, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: alarm reaction, anxiety, box breathing, Breathing, conditioning, defense reaction, health, huming, Parasympathetic response, rumination, safety, sniff inhale, somatic practices, stress, sympathetic arousal, tactical breathing, Toning, yoga 2 CommentsErik Peper, PhD, Yuval Oded, PhD, and Richard Harvey, PhD

Adapted from Peper, E., Oded, Y, & Harvey, R. (2024). Quick somatic rescue techniques when stressed. Biofeedback, 52(1).

“If a problem is fixable, if a situation is such that you can do something about it, then there is no need to worry. If it’s not fixable, then there is no help in worrying. There is no benefit in worrying whatsoever.” ― Dalai Lama XIV

To implement the Dalai Lama’s quote is challenging. When caught up in an argument, being angry, extremely frustrated, or totally stressed, it is easy to ruminate, worry. It is much more challenging to remember to stay calm. When remembering the message of the Dalai Lama’s quote, it may be possible to shift perspective about the situation although a mindful attitude may not stop ruminating thoughts. The body typically continues to reacti to the torrents of thoughts that may occur when rehashing rage over injustices, fear over physical or psychological threats, or profound grief and sadness over the loss of a family member. Some people become even more agitated and less rational as illustrated in the following examples.

I had an argument with my ex and I am still pissed off. Each time I think of him or anticipate seeing them, my whole body tightened. I cannot stomach seeing him and I already see the anger in his face and voice. My thoughts kept rehashing the conflict and I am getting more and more upset.

A car cut right in front of me to squeeze into my lane. I had to slam on my brakes. What an idiot! My heart rate was racing and I wanted to punch the driver.

When threatened, we respond quickly in our thoughts and body with a defense reaction that may negatively affect those around us as well as ourselves. What can we do to interrupt negative stress reactions?

Background

Many approaches exist that allow us to become calmer and less reactive. General categories include techniques of cognitive reappraisal (seeing the situation from the other person’s point of view and labeling your own feelings and emotions) and stress management techniques. Practices that are beneficial include mindfulness meditation, benign humor (versus gallows humor), listening to music, taking a time out while implementing a variety of self-soothing practices, or incorporating slow breathing (e.g., heart rate variability and/or box breathing) throughout the day.

No technique fits all as we respond differently to our stressful life circumstances. For example, some people during stress react with a “tend and befriend stress response” (Cohen & Lansing, 2021; Taylor et al., 2000). This response appears to be mostly mediated by the hormone oxytocin acting in ways that sooth or calm the nervous system as an analgesic. These neurophysiological mechanisms of the soothing with the calming analgesic effects of oxytocin have been characterized in detail by Xin, et al. (2017).

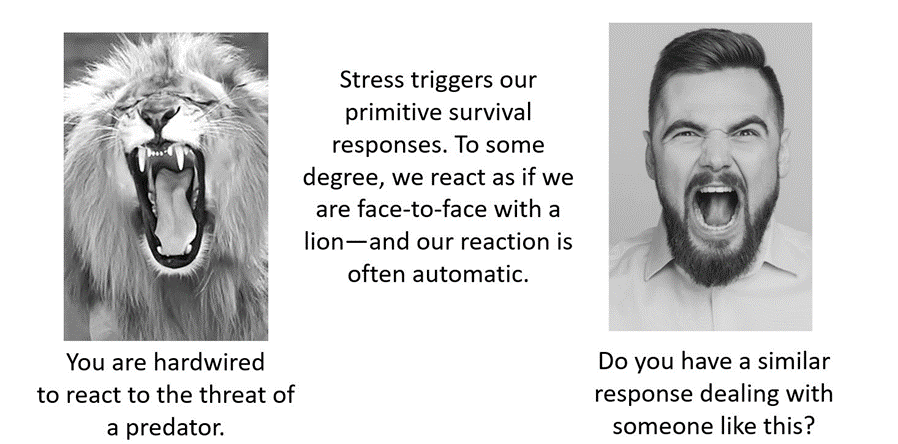

The most common response is a fight/flight/freeze stress response that is mediated by excitatory hormones such as adrenalin and inhibitory neurotransmitters such as gamma amino butyric acid (GABA). There is a long history of fight/flight/freeze stress response research, which is beyond the scope of this blog with major theories and terms such as interior milleau (Bernard, 1872); homeostasis and fight/flight (Cannon, 1929); general adaptation syndrome (Selye, 1951); polyvagal theory (Porges, 1995); and, allostatic load (McEwen, 1998). A simplified way to start a discussion about stress reactions begins with the fight/flight stress response. When stressed our defense reactions are triggered. Our sympathetic nervous system becomes activated our mind and body stereotypically responds as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. An intense confrontation tends to evoke a stress response (reproduced from Peper et al., 2020).

The flight/fight response triggers a cascade of stress hormones or neurotransmitters (e.g., hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal cascade) and produces body changes such as the heart pounding, quicker breathing, an increase in muscle tension and sweating. Our body mobilizes itself to protect itself from danger. Our focus is on immediate survival and not what will occur in the future (Porges, 2021; Sapolsky, 2004). It is as if we are facing an angry lion—a life-threatening situation—and we feel threatened and unsafe.

Rather than sitting still, a quick effective strategy is to interrupt this fight/flight response process by completing the alarm reaction such as by moving our muscles (e.g., simulating a fight or flight behavior) before continuing with slower breathing or other self-soothing strategies. Many people have experienced their body tension is reduced and they feel calmer when they do vigorous exercise after being upset, frustrated or angry. Similarly, athletes often have reported that they experience reduced frequency and/or intensity of negative thoughts after an exhausting workout (Thayer, 2003; Liao et al., 2015; Basso & Suzuki, 2017).

Becoming aware of the escalating cascades of physical, behavioral and psychological responses to a stressor is the first step in interrupting the escalating process. After becoming aware, reduce the body’s arousal and change the though patterns using any of the techniques described in this blog. The self-regulation skills presented in this blog are ideally over-learned and automated so that these skills can be rapidly implemented to shift from being stressed to being calm. Examples of skills that can shift from sympathetic neervous system overarousal to parasympathetic nervous system calm include techniques of autogenic traing (Schulz & Luthe, 1959), the quieting reflex developed by Charles Stroebel in 1985 or more recently rescue breathing developed by Richard Gevirtz (Stroebel, 1985; Gevirtz, 2014; Peper, Gibney & Holt, 2002; Peper & Gibney, 2003).

Concepts underlying the rescue techniques

- Psychophysiological principle: “Every change in the physiological state is accompanied by an appropriate change in the mental-emotional state, conscious or unconscious, and conversely, every change in the mental-emotional state, conscious or unconscious, is accompanied by an appropriate change in the physiological state” (Green et al. 1970, p. 3).

- Posture evokes memories and feelings associated with the position. When the body posture is erect and tall while looking slightly up. It is easier to evoke empowering, positive thoughts and feelings. When looking down it is easier to evoke hopeless, helpless and powerless thoughts and feelings (Peper et al., 2017).

- Healing occurs more easily when relaxed and feeling safe. Feeling safe and nurtured enhances the parasympathetic state and reduces the sympathetic state. Use memory recall to evoke those experiences when you felt safe (Peper, 2021).

- Interrupting thoughts is easier with somatic movement than by redirecting attention and thinking of something else without somatic movement.

- Focus on what you want to do not want to do. Attempting to stop thinking or ruminating about something tends to keeps it present (e.g., do not think of pink elephants. What color is the elephant? When you answer, “not pink,” you are still thinking pink). A general concept is to direct your attention (or have others guide you) to something else (Hilt & Pollak, 2012; Oded, 2018; Seo, 2023).

- Skill mastery takes practice and role rehearsal (Lally et al., 2010; Peper & Wilson, 2021).

- Use classical conditioning concepts to facilitate shifting states. Practice the skills and associate them with an aroma, memory, sounds or touch cues. Then when you the situation occurs, use these classical conditioned cues to facilitate the regeneration response (Peper & Wilson, 2021).

Rescue techniques

Coping When Highly Stressed and Agitated

- Complete the alarm/defense reaction with physical activity (Be careful when you do these physical exercises if you have back, hip, knee, or ankle problems).

- Acknowledge you have reacted and have chosen to interrupt your automatic response.

- Check whether the situation is actually a threat. If yes, then do anything to get out of immediate danger (yell, scream, fight, run away, or dial 911).

- If there is no actual physical threat, then leave the situation and perform vigorous physical activity to complete your alarm reaction, such as going for a run or walking quickly up and down stairs. As you do the exercise, push yourself so that the muscles in your thighs are aching, which focusses your attention on the sensations in your thighs. In our experience, an intensive run for 20 minutes quiets the brain while it often takes 40 minutes when walking somewhat quickly.

- After recovering from the exhaustive exercise, explore new options to resolve the conflict.

- Complete the alarm/defense reaction and evoke calmness with the S.O.S™ technique (Oded, 2023)

- Acknowledge you have reacted and have chosen to interrupt your automatic response.

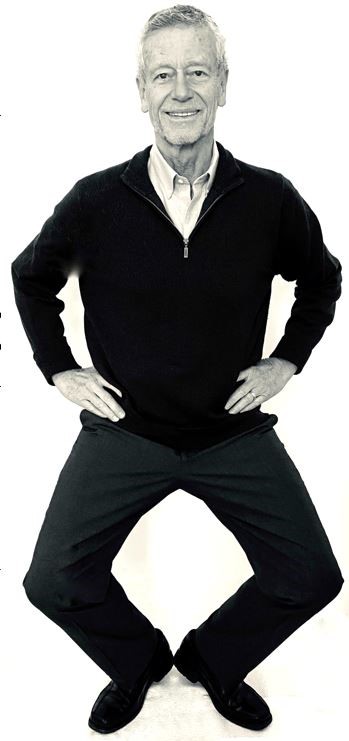

- Squat against a wall (similar to the wall-sit many skiers practice). While tensing your arms and fists as shown in Figure 2, gaze upward because it is more difficult to engage in negative thinking while looking upwards. If you continue to ruminate, then scan the room for object of a certain color or feature to shift visual attention and be totally present on the visual object.

- Do this set of movements for 7 to 10 seconds or until you start shaking. Than stand up and relax hands and legs. While standing, bounce up and down loosely for 10 to 15 seconds as you become aware of the vibratory sensations in your arms and shoulders, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2.Defense position wall-sit to tighten muscles in the protective defense posture (Oded, 2023). Figure 3. Bouncing up and down to loosen muscles ((Oded, 2023).

- Acknowledge you have reacted and have chosen to interrupt your automatic response. Swing your arms back and forth for 20 seconds. Allow the arms to swing freely as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Swinging the arms to loosen the body and spine (Oded, 2023).

- Rest and ground. Lie on the floor and put your calves and feet on a chair seat so that the psoas muscle can relax, as illustrated in Figure 5. Allow yourself to be totally supported by the floor and chair. Be sure there is a small pillow under your head and put your hand on your abdomen so that you can focus on abdominal breathing.

Figure 5. Lying down to allow the psoas muscle to relax and feel grounded (Oded, 2023).

- While lying down, imagine a safe place or memory and make it as real as possible. It is often helpful to listen to a guided imagery or music. The experience can be enhanced if cues are present that are associated with the safe place, such as pictures, sounds, or smells. Continue to breathe effortlessly at about six breaths per minute. If your attention wanders, bring it back to the memory or to the breathing. Allow yourself to rest for 10 minutes.

In most cases, thoughts stop and the body’s parasympathetic activity becomes dominant as the person feels safe and calm. Usually, the hands warm and the blood volume pulse amplitude increases as an indicator of feeling safe, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Blood volume pulse increases as the person is relaxing, feels safe and calm.

Coping When You Can’t Get Away (adapted from Peper, Harvey & Faass, 2020)

In many cases, it is difficult or embarrassing to remove yourself from the situation when you are stressed out such as at work, in a business meeting or social gathering.

- Become aware that you have reacted.

- Excuse yourself for a moment and go to a private space, such as a restroom. Going to the bathroom is one of the only acceptable social behaviors to leave a meeting for a short time.

- In the bathroom stall, do the 5-minute Nyingma exercise, which was taught by Tarthang Tulku Rinpoche in the tradition of Tibetan Buddhism, as a strategy for thought stopping (see Figure 7). Stand on your toes with your heels touching each other. Lift your heels off the floor while bending your knees. Place your hands at your sides and look upward. Breathe slowly and deeply (e.g., belly breathing at six breaths a minute) and imagine the air circulating through your legs and arms. Do this slow breathing and visualization next to a wall so you can steady yourself if necessary to keep balance. Stay in this position for 5 minutes or longer. Do not straighten your legs—keep squatting despite the discomfort. In a very short time, your attention is captured by the burning sensation in your thighs. Continue. After 5 minutes, stop and shake your arms and legs.

Figure 7. Stressor squat Nyingma exercise (reproduced from Peper et al., 2020).

- Follow this practice with slow abdominal breathing to enhance the parasympathetic response. Be sure that the abdomen expands as the inhalation occurs. Breathe in and out through the nose at about six breaths per minute.

- Once you feel centered and peaceful, return to the room.

- After this exercise, your racing thoughts most likely will have stopped and you will be able to continue your day with greater calm.

What to do When Ruminating, Agitated, Anxious or Depressed

(adapted from Peper, Harvey, & Hamiel, 2019).

- Shift your position by sitting or standing erect in a power position with the back of the head reaching upward to the ceiling while slightly gazing upward. Then sniff quickly through nose, hold and again sniff quickly then very slowly exhale. Be sure as you exhale your abdomen constricts. Then sniff again as your abdomen gets bigger, hold, and sniff one more time letting the abdomen get even bigger. Then, very slow, exhale through the nose to the internal count of six (adapted from Balban et al., 2023). When you sniff or gasp, your racing thoughts will stop (Peper et al., 2016).

- Continue with box breathing (sometimes described as tactical breathing or battle breathing) by exhaling slowly through your nose for 4 seconds, holding your breath for 4 seconds, inhaling slowly for 4 seconds through your nose, holding your breath for 4 seconds and then repeating this cycle of breathing for a few minutes (Röttger et al., 2021; Balban et al., 2023). Focusing your attention on performing the box breathing makes it almost impossible to think of anything else. After a few minutes, follow this with slow effortless diaphragmatic breathing at about six breaths per minute. While exhaling slowly through your nose, look up and when you inhale imagine the air coming from above you. Then as you exhale, imagine and feel the air flowing down and through your arms and legs and out the hands and feet.

- While gazing upward, elicit a positive memory or a time when you felt safe, powerful, strong and/or grounded. Make the positive memory as real as possible.

- Implement cognitive strategies such as reframing the issue, sending goodwill to the person, seeing the problem from the other person’s point of view, and ask is this problem worth dying over (Peper, Harvey, & Hamiel, 2019).

What to Do When Thoughts Keep Interrupting

Practice humming or toning. When you are humming or toning, your focus is on making the sound and the thoughts tend to stop. Generally, breathing will slow down to about six breaths per minute (Peper, Pollack et al., 2019). Explore the following:

- Box breathing (Röttger et al., 2021; Balban et al., 2023)

- Humming also known as bee breath (Bhramari Pranayama) (Abishek et al., 2019; Yoga, 2023) – Allow the tongue to rest against the upper palate, sit tall and erect so that the back of the head is reaching upward to the ceiling, and inhale through your nose as the abdomen expands. Then begin humming while the air flows out through your nose, feel the vibration in the nose, face and throat. Let humming last for about 7 seconds and then allow the air to blow in through the nose and then hum again. Continue for about 5 minutes.

- Toning – Inhale through your nose and then vocalize a single sound such as Om. As you vocalize the lower sound, feel the vibration in your throat, chest and even going down to the abdomen. Let each toning exhalation last for about 6 to 7 seconds and then inhale through your nose. Continue for about 5 minutes (Peper, al., 2019).

Many people report that after practice these skills, they become aware that they are reacting and are able to reduce their automatic reaction. As a result, they experience a significant decrease in their stress levels, fewer symptoms such as neck and holder tension and high blood pressure, and they feel an increase in tranquility and the ability to communicate effectively.

Practicing these skills does not resolve the conflicts; they allow you to stop reacting automatically. This process allows you a time out and may give you the ability to be calmer, which allows you to think more clearly. When calmer, problem solving is usually more successful. As phrased in a popular meme, “You cannot see your reflection in boiling water. Similarly, you cannot see the truth in a state of anger. When the waters calm, clarity comes” (author unknown).

Boiling water (photo modified from: https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=388991500314839&set=a.377199901493999)

Below are additional resources that describe the practices. Please share these resources with friends, family and co-workers.

Stressor squat instructions

Toning instructions

Diaphragmatic breathing instructions

Reduce stress with posture and breathing

Conditioning

References

Abishek, K., Bakshi, S. S., & Bhavanani, A. B. (2019). The efficacy of yogic breathing exercise bhramari pranayama in relieving symptoms of chronic rhinosinusitis. International Journal of Yoga, 12(2), 120–123. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijoy.IJOY_32_18

Balban, M. Y., Neri, E., Kogon, M. M., Weed, L., Nouriani, B., Jo, B., Holl, G., Zeitzer, J. M., Spiegel, D., Huberman, A. D. (2023). Brief structured respiration practices enhance mood and reduce physiological arousal. Cell Reports Medicine, 4(1), 10089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100895

Basso, J. C. & Suzuki, W. A. (2017). The effects of acute exercise on mood, cognition, neurophysiology, and neurochemical pathways: A review. Brain Plast, 2(2), 127–152. https://doi.org/10.3233/BPL-160040

Bernard, C. (1872). De la physiologie générale. Paris: Hachette livre. https://www.amazon.ca/PHYSIOLOGIE-GENERALE-BERNARD-C/dp/2012178596

Cannon, W. B. (1929). Organization for Physiological Homeostasis. Physiological Reviews, 9, 399–431. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.1929.9.3.399

Cohen, L. & Lansing, A. H. (2021). The tend and befriend theory of stress: Understanding the biological, evolutionary, and psychosocial aspects of the female stress response. In: Hazlett-Stevens, H. (eds), Biopsychosocial Factors of Stress, and Mindfulness for Stress Reduction. pp. 67–81, Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81245-4_3

Gevirtz, R. (2014). HRV Training and its Importance – Richard Gevirtz, Ph.D., Pioneer in HRV Research & Training. Thought Technology. Accessed December 29, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9nwFUKuJSE0

Green, E. E., Green, A. M., & Walters, E. D. (1970). Voluntary control of internal states: Psychological and physiological. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 2, 1–26. https://atpweb.org/jtparchive/trps-02-70-01-001.pdf

Hilt, L. M., & Pollak, S. D. (2012). Getting out of rumination: comparison of three brief interventions in a sample of youth. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40(7), 1157–1165.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-012-9638-3

Lally, P., VanJaarsveld, C. H., Potts, H. W., & Wardle, J. (2010). How habits are formed: Modelling habit formation the real world. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 998–1009. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.674

Liao, Y., Shonkoff, E. T., & Dunton, G. F. (2015). The acute relationships between affect, physical feeling states, and physical activity in daily life: A review of current evidence. Frontiers in Psychology. 6, 1975. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01975

McEwen, B. S. (1998). Stress, adaptation, and disease: Allostasis and allostatic load. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 840(1), 33–44.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09546.x

Oded, Y. (2018). Integrating mindfulness and biofeedback in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Biofeedback, 46(2), 37-47. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-46.02.03

Oded, Y. (2023). Personal communication. S.O.S 1™ technique is part of the Sense Of Safety™ method. www.senseofsafety.co

Peper, E. (2021). Relive memory to create healing imagery. Somatics, XVIII(4), 32–35.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/369114535_Relive_memory_to_create_healing_imagery

Peper, E., Gibney, K.H. & Holt. C. (2002). Make Health Happen: Training Yourself to Create Wellness. Dubuque, IA: Kendall-Hunt. https://he.kendallhunt.com/product/make-health-happen-training-yourself-create-wellness

Peper, E., & Gibney, K.H. (2003). A teaching strategy for successful hand warming. Somatics. XIV(1), 26–30. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/376954376_A_teaching_strategy_for_successful_hand_warming

Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Faass, N. (2020). TechStress: How Technology is Hijacking Our Lives, Strategies for Coping, and Pragmatic Ergonomics. North Atlantic Books. https://www.amazon.com/Beyond-Ergonomics-Prevent-Fatigue-Burnout/dp/158394768X

Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Hamiel, D. (2019). Transforming thoughts with postural awareness to increase therapeutic and teaching efficacy. NeuroRegulation, 6(3),153–160. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.6.3.153

Peper, E., Lee, S., Harvey, R., & Lin, I-M. (2016). Breathing and math performance: Implication for performance and neurotherapy. NeuroRegulation, 3(4), 142–149. http://dx.doi.org/10.15540/nr.3.4.142

Peper, E., Lin, I-M, Harvey, R., & Perez, J. (2017). How posture affects memory recall and mood. Biofeedback, 45(2), 36–41. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-45.2.01

Peper, E., Pollack, W., Harvey, R., Yoshino, A., Daubenmier, J. & Anziani, M. (2019). Which quiets the mind more quickly and increases HRV: Toning or mindfulness? NeuroRegulation, 6(3), 128–133. https://www.neuroregulation.org/article/view/19345/13263

Peper, E. & Wilson, V. (2021). Optimize the learning state: Techniques and habits. Biofeedback, 9(2), 46–49. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-49-2-04

Porges, S. W. (1995). Orienting in a defensive world: Mammalian modifications of our evolutionary heritage. A polyvagal theory. Psychophysiology, 32(4), 301–318. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.1995.tb01213.x

Porges, S.W. (2021) Cardiac vagal tone: a neurophysiological mechanism that evolved in mammals to dampen threat reactions and promote sociality. World Psychiatry, 20(2),296-298. Porges SW. Cardiac vagal tone: a neurophysiological mechanism that evolved in mammals to dampen threat reactions and promote sociality. World Psychiatry. 2021 Jun;20(2):296-298. https://doi.org10.1002/wps.20871

Röttger, S., Theobald, D. A., Abendroth, J., & Jacobsen, T. (2021). The effectiveness of combat tactical breathing as compared with prolonged exhalation. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 46, 19–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-020-09485-w

Sapolsky, R. (2004). Why zebras don’t get ulcers (3rd ed.). New York:Holt. https://www.amazon.com/Why-Zebras-Dont-Ulcers-Third/dp/0805073698/

Schultz, J. H., & Luthe, W. (1959). Autogenic training: A psychophysiologic approach to psychotherapy. Grune & Stratton. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Autogenic_Training/y8SwQgAACAAJ?hl=en

Selye, H. (1951). The general-adaptation-syndrome. Annual Review of Medicine, 2(1), 327–342. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.me.02.020151.001551

Seo, H. (2023). How to stop ruminating. The New York Times. Accessed January 3, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/01/well/mind/stop-rumination-worry.html

Stroebel, C. F. (1985). QR: The Quieting Reflex. Berkley. https://www.amazon.com/Qr-quieting-reflex-Charles-Stroebel/dp/0425085066

Taylor, S. E., Klein, L. C., Lewis, B. P., Gruenewald, T. L., Gurung, R. A. R., & Updegraff, J. A. (2000). Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: Tend-and-befriend, not fight-or-flight. Psychological Review, 107(3), 411–429. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.107.3.411

Thayer, R. E. (2003). Calm energy: How people regulate mood with food and exercise. Oxford University Press. https://www.amazon.com/Calm-Energy-People-Regulate-Exercise/dp/0195163397

Xin, Q., Bai, B., & Liu, W. (2017). The analgesic effects of oxytocin in the peripheral and central nervous system. Neurochemistry International, 103, 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuint.2016.12.021

Yoga, N. (2023). This simple breath practice is scientifically proven to calm your mind. The nomadic yogi. Accessed December 31, 2023. https://www.leahsugerman.com/blog/bhramari-pranayama-humming-bee-breath#

TechStress: Building Healthier Computer Habits

Posted: August 30, 2023 Filed under: ADHD, behavior, biofeedback, Breathing/respiration, cognitive behavior therapy, computer, digital devices, education, emotions, ergonomics, Evolutionary perspective, Exercise/movement, health, laptops, Neck and shoulder discomfort, Pain/discomfort, posture, screen fatigue, stress management, Uncategorized, vision, zoom fatigue | Tags: cellphone, fatigue, gaming, mobile devices, screens 2 CommentsBy Erik Peper, PhD, BCB, Richard Harvey, PhD, and Nancy Faass, MSW, MPH

Adapted by the Well Being Journal, 32(4), 30-35. from the book, TechStress: How Technology is Hijacking Our Lives, Strategies for Coping, and Pragmatic Ergonomics by Erik Peper, Richard Harvey, and Nancy Faass.

Every year, millions of office workers in the United States develop occupational injuries from poor computer habits—from carpal tunnel syndrome and tension headaches to repetitive strain injury, such as “mouse shoulder.” You’d think that an office job would be safer than factory work, but the truth is that many of these conditions are associated with a deskbound workstyle.

Back problems are not simply an issue for workers doing physical labor. Currently, the people at greatest risk of injury are those with a desk job earning over $70,000 annually. Globally, computer-related disorders continue to be on the rise. These conditions can affect people of all ages who spend long hours at a computer and digital devices.

In a large survey of high school students, eighty-five percent experienced tension or pain in their neck, shoulders, back, or wrists after working at the computer. We’re just not designed to sit at a computer all day.

Field of Ergonomics

For the past twenty years, teams of researchers all over the world have been evaluating workplace stress and computer injuries—and how to prevent them. As researchers in the fields of holistic health and ergonomics, we observe how people interact with technology. What makes our work unique is that we assess employees not only by interviewing them and observing behaviors, but also by monitoring physical responses.

Specifically, we measure muscle tension and breathing, in the moment, in real-time, while they work. To record shoulder pain, for example, we place small sensors over different muscles and painlessly measure the muscle tension using an EMG (electromyograph)—a device that is employed by physicians, physical therapists, and researchers. Using this device, we can also keep a record of their responses and compare their reactions over time to determine progress.

What we’ve learned is that people get into trouble if their muscles are held in tension for too long. Working at a computer, especially at a stationary desk, most people maintain low-level chronic tension for much of the day. Shallow, rapid breathing is also typical of fine motor tasks that require concentration, like data entry.

Muscle tension and breathing rate usually increase during data entry or typing without our awareness.

When these patterns are paired with psychological pressure due to office politics or job insecurity, the level of tension and the risk of fatigue, inflammation, pain, or injury increase. In most cases, people are totally unaware of the role that tension plays in injury. Of note, the absolute level of tension does not predict injury—rather, it is the absence of periodic rest breaks throughout the day that seems to correlate with future injuries.

Restbreaks

All of life is the alternation between movement and rest, inhaling and exhaling, sleeping and waking. Performing alternating tasks or different types of activities and movement is one way to interrupt the couch potato syndrome—honoring our evolutionary background.

Our research has confirmed what others have observed: that it’s important to be physically active, at least periodically, throughout the day. Alternating activity and rest recreate the pattern of our ancestors’ daily lives. When we alternate sedentary tasks with physical activity, and follow work with relaxation, we function much more efficiently. In short, move your body more.

Better Computer Habits: Alternate Periods of Rest and Activity

As mentioned earlier, our workstyle puts us out of sync with our genetic heritage. Whether hunting and gathering or building and harvesting, our ancestors alternated periods of inactivity with physical tasks that required walking, running, jumping, climbing, digging, lifting, and carrying, to name a few activities. In contrast, today many of us have a workstyle that is so immobile we may not even leave our desk for lunch.

As health researchers, we have had the chance to study workstyles all over the world. Back pain and strain injuries now affect a large proportion of office workers in the US and in high-tech firms worldwide. The vast majority of these jobs are sedentary, so one focus of the research is on how to achieve a more balanced way of working.

A recent study on exercise looked at blood flow to the brain. Researchers Carter and colleagues found that if people sit for four hours on the job, there’s a significant decrease in blood flow to the brain. However, if every thirty or forty minutes they get up and move around for just two minutes, then brain blood flow remains steady. The more often you interrupt sitting with movement, the better.

It may seem obvious that to stay healthy, it’s important to take breaks and be physically active from time to time throughout the day. Alternating activity and rest recreate the pattern of our ancestors’ daily lives. The goal is to alternate sedentary tasks with physical activity and follow work with relaxation. When we keep this type of balance going, most people find that they have more energy, are more productive, and can be more effective.

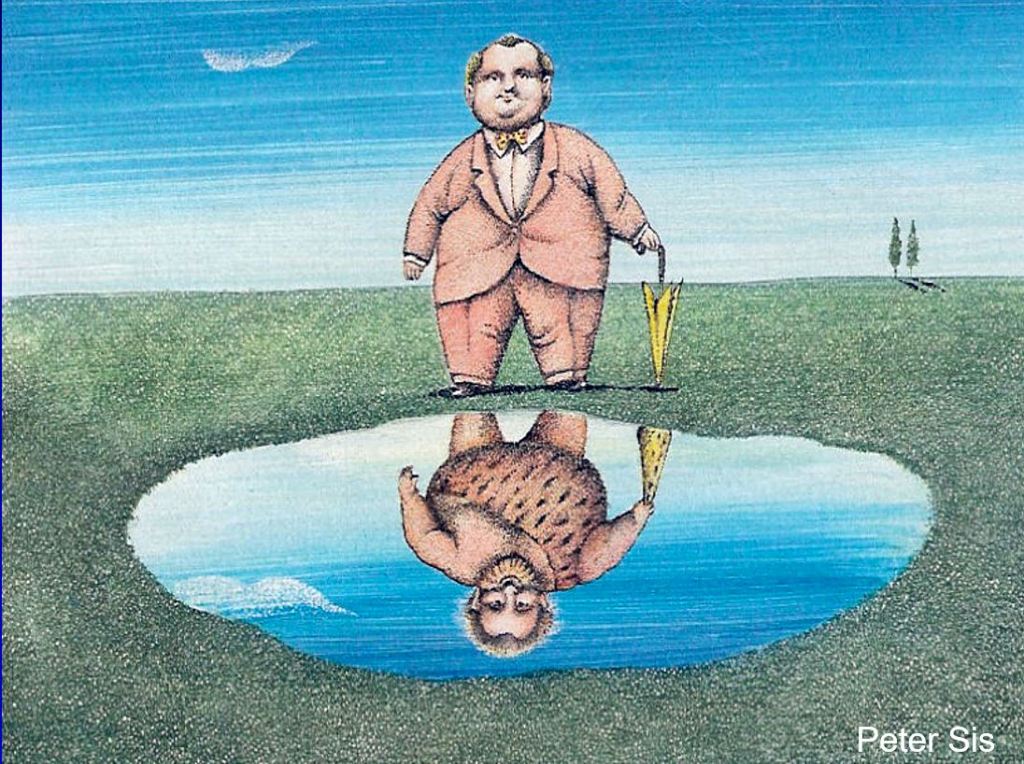

Genetics: We’re Hardwired Like Ancient Hunters

Despite a modern appearance, we carry the genes of our forebearers—for better and for worse. (Art courtesy of Peter Sis). Reproduced from Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Faass (2020). TechStress: How Technology is Hijacking Our Lives, Strategies for Coping, and Pragmatic Ergonomics. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books.

In the modern workplace, most of us find ourselves working indoors, in small office spaces, often sitting at a computer for hours at a time. In fact, the average Westerner spends more than nine hours per day sitting indoors, yet we’re still genetically programmed to be physically active and spend time outside in the sunlight most of the day, like the nomadic hunters and gatherers of forty thousand years ago.

Undeniably, we inherently conserve energy in order to heal and regenerate. This aspect of our genetic makeup also helps burn fewer calories when food is scarce. Hence the propensity for lack of movement and sedentary lifestyle (sitting disease).

In times of famine, the habit of sitting was essential because it reduced calorie expenditure, so it enabled our ancestors to survive. In a prehistoric world with a limited food supply, less movement meant fewer calories burned. Early humans became active when they needed to search for food or shelter. Today, in a world where food and shelter are abundant for most Westerners, there is no intrinsic drive to initiate movement.

It is also true that we have survived as a species by staying active. Chronic sitting is the opposite of our evolutionary pattern in which our ancestors alternated frequent movement while hunting or gathering food with periods of rest. Whether they were hunters or farmers, movement has always been an integral aspect of daily life. In contrast, working at the computer—maintaining static posture for hours on end—can increase fatigue, muscle tension, back strain, and poor circulation, putting us at risk of injury.

Quit a Sedentary Workstyle

Almost everyone is surprised by how quickly tension can build up in a muscle, and how painful it can become. For example, we tend to hover our hands over the keyboard without providing a chance for them to relax. Similarly, we may tighten some of the big muscles of our body, such as bracing or crossing our legs.

What’s needed is a chance to move a little every few minutes—we can achieve this right where we sit by developing the habit of microbreaks. Without regular movement, our muscles can become stiff and uncomfortable. When we don’t take breaks from static muscle tension, our muscles don’t have a chance to regenerate and circulate oxygen and necessary nutrients.

Build a variety of breaks into your workday:

- Vary work tasks

- Take microbreaks (brief breaks of less than thirty seconds)

- Take one-minute stretch breaks

- Fit in a moving break

Varying Work Tasks

You can boost physical activity at work by intentionally leaving your phone on the other side of the desk, situating the printer across the room, or using a sit-stand desk for part of the day. Even a few minutes away from the desk makes a difference, whether you are hand delivering documents, taking the long way to the bathroom, or pacing the room while on a call.

When you alternate the types of tasks and movement you do, using a different set of muscles, this interrupts the contractions of muscle fibers and allows them to relax and regenerate. Try any of these strategies:

- Alternate computer work with other activities, such as offering to do a coffee run

- Schedule walking meetings with coworkers

- Vary keyboarding and hand movements

Ultimately, vary your activities and movements as much as possible. By changing your posture and making sure you move, you’ll find that your circulation and your energy improve, and you’ll experience fewer aches and pains. In a short time, it usually becomes second nature to vary your activities throughout the day.

Experience It: “Mouse Shoulder” Test

You can test this simple mousing exercise at the computer or as a simulation. If you’re at the computer, sit erect with your hand on the mouse next to the keyboard. To simulate the exercise, sit with erect posture as if you were in front of your computer and hold a small object you can use to imitate mousing.

With the mouse (or a sham mouse), simulate drawing the letters of your name and your street address, right to left. Be sure each letter is very small (less than half an inch in height). After drawing each letter, click the mouse.

As part of the exercise, draw the letters and numbers as quickly as possible for ten to fifteen seconds. What did you observe? In almost all cases, you may note that you tightened your mousing shoulder and your neck, stiffened your trunk, and held your breath. All this occurred without awareness while performing the task. Over time, this type of muscle tension can contribute to discomfort, soreness, pain, or eventual injury.

Microbreaks

If you’ve developed an injury—or have chronic aches and pains—you’ll probably find split-second microbreaks invaluable. A microbreak means taking brief periods of time that last just a few seconds to relax the tension in your wrists, shoulders, and neck.

For example, when typing, simply letting your wrists drop to your lap for a few seconds will allow the circulation to return fully to help regenerate the muscles. The goal is to develop a habit that is part of your routine and becomes automatic, like driving a car. To make the habit of microbreaks practical, think about how you can build the breaks into your workstyle. That could mean a brief pause after you’ve completed a task, entered a column of data, or before starting typing out an assignment.

For frequent microbreaks, you don’t even need to get up—just drop your hands in your lap or shake them out, move your shoulders, and then resume work. Any type of shaking or wiggling movement is good for your circulation and kind of fun.

In general, a microbreak may be defined as lasting one to thirty seconds. A minibreak may last roughly thirty seconds to a few minutes, and longer large-movement breaks are usually greater than a few minutes. Popular microbreaks:

- Take a few deep breaths

- Pause to take a sip of water

- Rest your hands in your lap

- Stretch

- Let your arms drop to your sides

- Shake out your hands (wrists and fingers)

- Perform a quick shoulder or neck roll

Often, we don’t realize how much tension we’ve been carrying until we become more mindful of it. We can raise our awareness of excess tension—this is a learned skill—and train ourselves to let go of excess muscle tension. As we increase our awareness, we’re able to develop a new, more dynamic workstyle that better fits our goals and schedule.

One-Minute Stretch Breaks

We all benefit from a brief break, even with the best of posture (left). One approach is to totally release your muscles (middle). That release can be paired with a series of brief stretches (right). Reproduced from Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Faass (2020). TechStress: How Technology is Hijacking Our Lives, Strategies for Coping, and Pragmatic Ergonomics. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books.

The typical mini-stretch break lasts from thirty seconds to a few minutes, and ideally you want to take them several times per hour. Similar to microbreaks, mini-stretch breaks are especially important for people with an injury or those at risk of injury. Taking breaks is vital, especially if you have symptoms related to computer stress or whenever you’re working long hours at a sedentary job. To take a stretch break:

Begin with a big stretch, for example, by reaching high over your head then drop your hands in your lap or to your sides.

Look away from the monitor, staring at near and far objects, and blink several times. Straighten your back and stretch your entire backbone by lifting your head and neck gently, as if there were an invisible string attached to the crown of your head.

Stretch your mind and body. Sitting with your back straight and both feet flat on the floor, close your eyes and listen to the sounds around you, including the fan on the computer, footsteps in the hallway, or the sounds in the street.

Breathe in and out over ten seconds (breathe in for four or five seconds and breathe out for five or six seconds), making the exhale slightly longer than the inhale. Feel your jaw, mouth, and tongue muscles relax. Feel the back and bottom of the chair as your body breathes all around you. Envision someone in your mind’s eye who is kind and reassuring, who makes you feel safe and loved, and who can bring a smile to your face inwardly or outwardly.

Do a wiggling movement. When you take a one-minute break, wiggling exercises are fast and easy, and especially good for muscle tension or wrist pain. Wiggle all over—it feels good, and it’s also a great way to improve circulation.

Building Exercise and Movement into Every Day

Studies show that you get more benefit from exercising ten to twenty minutes, three times a day, than from exercising for thirty to sixty minutes once a day. The implication is that doing physical activities for even a few minutes can make a big difference.

Dunstan and colleagues have found that standing up three times an hour and then walking for just two minutes reduced blood sugar and insulin spikes by twenty-five percent.Fit in a Moving Break

Fit in a Moving Break

Once we become conscious of muscle tension, we may be able to reverse it simply by stepping away from the desk for a few minutes, and also by taking brief breaks more often. Explore ways to walk in the morning, during lunch break, or right after work. Ideally, you also want to get up and move around for about five minutes every hour.

Ultimately, research makes it clear that intermittent movement, such as brief, frequent stretching throughout the day or using the stairs rather than elevator, is more beneficial than cramming in a couple of hours at the gym on the weekend. This explains why small changes can have a big impact—it’s simply a matter of reminding yourself that it’s worth the effort.

Workstation Tips

Your ability to see the display and read the screen is key to reducing neck and eye strain. Here are a few strategic factors to remember:

Monitor height: Adjust the height of your monitor so the top is at eyebrow level, so you can look straight ahead at the screen.

Keyboard height: The keyboard height should be set so that your upper arms hang straight down while your elbows are bent at a 90-degree angle (like the letter L) with your forearms and wrists held horizontally.

Typeface and font size: For email, word processing, or web content, consider using a sans serif typeface. Fonts that have fewer curved lines and flourishes (serifs) tend to be more readable on screen.

Checking your vision: Many adults benefit from computer glasses to see the screen more clearly. Generally, we do not recommend reading glasses, bifocals, trifocals, and progressive lenses as they tend to allow clear vision at only one focal length. To see through the near-distance correction of the lens requires you to tilt your head back. Although progressive lenses allow you to see both close up and at a distance, the segment of the lens for each focal length is usually too narrow for working at the computer.

Wearing progressive lenses requires you to hold your head in a fixed position to be in focus. Yet you may be totally unaware that you are adapting your eye and head movements to sustain your focus. When that is the case, most people find that special computer glasses are a good solution.

Consider computer glasses if you must either bring your nose to the screen to read the text, wear reading glasses and find that their focal length is inappropriate for the monitor distance, wear bi- or trifocal glasses, or are older than forty.

Computer glasses correct for the appropriate focal distance to the computer. Typically, monitor distance is about twenty-three to twenty-eight inches, whereas reading glasses correct for a focal length of about fifteen inches. To determine your individual, specific focal length, ask a coworker to measure the distance from the monitor to your eyes. Provide this personal focal distance at the eye exam with your optometrist or ophthalmologist and request that your computer glasses be optimized for that distance.

Remembering to blink: As we focus on the screen, our blinking rate is significantly reduced. Develop the habit of blinking periodically: at the end of a paragraph, for example, or when sending an email.

Resting your eyes: Throughout the day, pause and focus on the far distance to relax your eyes. When looking at the screen, your eyes converge, which can cause eyestrain. Each time you look away and refocus, that allows your eyes to relax. It’s especially soothing to look at green objects such as a tree that can be seen through a window.

Minimizing glare: If the room is lit with artificial light, there may be glare from your light source if the light is right in front of you or right behind you, causing reflection on your screen. Reflection problems are minimized when light sources are at a 90-degree angle to the monitor (with the light coming from the side). The worst situations occur when the light source is either behind or in front of you.

An easy test is to turn off your monitor and look for reflections on the screen. Everything that you see on the monitor when it’s turned off is there when you’re working at the monitor. If there are bright reflections, they will interfere with your vision. Once you’ve identified the source of the glare, change the location of the reflected objects or light sources, or change the location of the monitor.

Contrast: Adjust the light contrast in the room so that it is neither too bright nor too dark. If the room is dark, turn on the lights. If it is too bright, close the blinds or turn off the lights. It is exhausting for your eyes to have to adapt from bright outdoor light to the lighting of your computer screen. You want the light intensity of the screen to be somewhat similar to that in the room where you’re working. You also do not want to look from your screen to a window lit by intense sunlight.

Don’t look down at phone: According to Kenneth Hansraj, MD, chief of spine surgery at New York Spine Surgery and Rehabilitation Medicine, pressure on the spine increases from about ten pounds when you are holding your head erect, to sixty pounds of pressure when you are looking down. Bending forward to look at your phone, your head moves out of the line of gravity and is no longer balanced above your neck and spine. As the angle of the face-forward position increases, this intensifies strain on the neck muscles, nerves, and bones (the vertebrae).

The more you bend your neck, the greater the stress since the muscles must stretch farther and work harder to hold your head up against gravity. This same collapsed head-forward position when you are seated and using the phone repeats the neck and shoulder strain. Muscle strain, tension headaches, or neck pain can result from awkward posture with texting, craning over a tablet (sometimes referred to as the iPad neck), or spending long hours on a laptop.

A face-forward position puts as much as sixty pounds of pressure on the neck muscles and spine.

Repetitive strain of neck vertebrae (the cervical spine), in combination with poor posture, can trigger a neuromuscular syndrome sometimes diagnosed as thoracic outlet syndrome. According to researchers Sharan and colleagues, this syndrome can also result in chronic neck pain, depression, and anxiety.

When you notice negative changes in your mood or energy, or tension in your neck and shoulders, use that as a cue to arch your back and look upward. Think of a positive memory, take a mindful breath, wiggle, or shake out your shoulders if you’d like, and return to the task at hand.

Strengthen your core: If you find it difficult to maintain good posture, you may need to strengthen your core muscles. Fitness and sports that are beneficial for core strength include walking, sprinting, yoga, plank, swimming, and rowing. The most effective way to strengthen your core is through activities that you enjoy.

Final Thoughts

If these ideas resonate with you, consider lifestyle as the first step. We need to build dynamic physical activity into our lives, as well as the lives of our children. Being outside is usually an uplift, so choose to move your body in natural settings whenever possible, whatever form that takes. Being outside is the factor that adds an energetic dimension. Finally, share what you learn, and help others learn and grow from your experiences.

If you spend time in front of a computeror using a mobile device, read the book, TechStress: How Technology is Hijacking Our Lives, Strategies for Coping, and Pragmatic Ergonomics. It provides practical, easy-to-use solutions for combating the stress and pain many of us experience due to technology use and overuse. The book offers extremely helpful tips for ergonomic use of technology, it

goes way beyond that, offering simple suggestions for improving muscle health that seem obvious once you read them, but would not have thought of yourself: “Why didn’t I think of that?” You will learn about the connection between posture and mood, reasons for and importance of movement breaks, specific movements you can easily perform at your desk, as well as healthier ways to utilize technology in your everyday life.

Additional resources

Healing a Shoulder/Chest Injury

Posted: August 14, 2023 Filed under: behavior, biofeedback, Breathing/respiration, emotions, Exercise/movement, healing, Neck and shoulder discomfort, Pain/discomfort, relaxation, self-healing, Uncategorized | Tags: electromyograph, guided imagery, shoulder pain Leave a commentAdapted from Peper, E. & Fuhs, M. (2004). Applied psychophysiology for therapeutic use: Healing a shoulder injury, Biofeedback, 32(2), 11-18.

“It has been an occurrence of the third dimension for me! How come my pain — that lasted for more than 10 days and was still so strong that I really had difficulties in breathing, couldn’t laugh without pain nor move my arm not even to fulfil my daily routines such as dressing and eating — disappeared within one single session of 20 minutes? And not only that, I was able to freely rotate my arm as if it had never been injured before.” —23 year old woman

The participant T., aged 23, was a psychology student who participated in an educational workshop for Healthy Computing. She volunteered to be a subject for a surface electromyographic (SEMG) monitoring and feedback demonstration. Ten days prior to this workshop, she had a severe skiing accident. She described the accident as follows:

I went skiing and may be I had too much snow in my ski-binding and while turning, I slipped out of my binding and fell head first down into the hill. As I fell, I landed on my ski pole which hit my left upper chest and breast area. Afterwards, my head was humming and I assumed that I had a light concussion. I stopped skiing and stayed in bed for a while. The next day it started hurting and I couldn’t turn my head or put my shoulders back (they were rotated forward). Also, I couldn’t ski as I was not able to look down to my feet–my muscles were too contracted and I felt searing pain whenever I moved. I hoped that it would go away however, the pain and left forward shoulder rotation stayed.

Assessment

Observation and Palpation

T.´s left shoulder was rolled forward (adducted and in internal rotation). She was not able to breathe or laugh without pain or move her arm freely. All movements in vertical and horizontal directions and rotations were restricted by at least 50 % as compared to her right arm (limitations in shoulder extension, flexion and external rotation). Also, her hands were ice-cold and she breathed very shallowly and rapidly in her chest. She was not able to stand in an upright position or sit in a comfortable position without maintaining her left upper extremity in a protected position. Her left shoulder blade (scapula) was winging.

After visually observing her, the instructor placed his left hand on her left shoulder and pectoralis muscles and his right hand on the back of her shoulder. Using palpation and anchoring her back with his leg so that she could not rotate her trunk, he explored the existing range of shoulder movement. He also attempted to rotate the left shoulder outward and back–not by forcing or pulling—but by very gentle traction. No change in mobility was observed and the pectoralis muscle felt tight (SEMG monitoring is helpful to the therapist during such a diagnostic assessment by helping to identify the person’s reactivity and avoiding to evoke and condition even more bracing). T. reported afterwards that she was very scared by this assessment because there was one point in the back which was highly reactive to touch. T. appeared to tighten automatically out of fear and trigger a general flexor contraction pattern—a process that commonly occurs if a person is guarding an area.

Often a traumatic injury first induces a general shock that triggers an automatic freeze and fear reaction. Therefore, an intervention needed to be developed that did not trigger vigilance or fear and thereby allowed the muscle to relax. If pain is experienced or increased, it is another negative reinforcement for generalizing guarding and bracing and tightening the muscles. This guarding decreases mobility – a common reaction that may occur when health professionals in the process of assessment increase the client’s discomfort. T.’s vigilance was also “telegraphed” to the therapist by her ice-cold hands and very shallow chest breathing. Therefore, it was important to increase her comfort level and to not induce any further pain. We hypothesized that only if she felt safe it would be possible for her muscle tension to decrease and thereby increase her mobility.

Underlying concept: The very cold hands and shallow breathing probably indicated excessive vigilance and arousal—a possible indicator of a catabolic state that could limit regeneration. The chronic cold hands most likely implied that she was very sensitive to other people’s emotions and continuously searches/scans the environment for threats. In addition, she indicated that she liked to do/perform her best which induced more anxiety and fear of judgement.