Resolving a chronic headache with posture feedback and breathing

Posted: January 4, 2022 Filed under: behavior, Breathing/respiration, computer, digital devices, ergonomics, health, laptops, Neck and shoulder discomfort, Pain/discomfort, posture, relaxation, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: Desktop feedback app, headache, migraine 11 Comments| Adapted from Peper, E., Covell, A., & Matzembacker, N. (2021). How a chronic headache condition became resolved with one session of breathing and posture coaching. NeuroRegulation, 8(4), 194–197. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.8.4.194 |

This blog describes the process by which a 32 year old woman student’s chronic headaches that she had since age eighteen was resolved in a single coaching session. The student suffered two or three headache per week a week which initially began when she was eighteen after using digital devices and encouraged her to slouch as she looked down. Although she describes herself as healthy, she reported having high level of anxiety and occasional depression. She self-medicated with 2 to 10 Excedrin tablets a week. It is possible that the chronic headaches could partially be triggered by caffeine withdrawal which get resolved by taking more Excedrins (Greben et al., 1980) since Excedrin contains 65 mg of caffeine as well as 250 mg of Acetaminophen which can be harmful to liver function (Bauer et al., 2021).

The behavioral coaching intervention

During the first day in class, the student approached the instructor and she shared that she had a severe headache. During their conversation, the instructor noticed that she was breathing in her chest without abdominal movement, her shoulders were held tight, her posture slightly slouched and her hands were cold. As she was unaware of her body responses, the instructor offered to guide her through some practices that may be useful to reduce her headache. The same strategies could also be useful for the other students in the class; since, headaches, anxiety, zoom fatigue, neck and shoulder tension, abdominal discomfort, and vision problems are common and have increased as people spent more time in front of screens (Charles et al., 2021; Ahmed et al., 2021; Bauer, 2021; Kuehn, 2021; Peper et al., 2021 ).

These symptoms may occur because of bad posture, neck and shoulder tension, shallow chest breathing, stress and social isolation (Elizagaray-Garcia et al., 2020; Schulman, 2002). When people become aware of their dysfunctional somatic patterns and change their posture, breathing pattern, internal language and implement stress management techniques, they often report a reduction in symptoms such as irritable bowel syndrome, acid reflux, neck and shoulder tension, or anxiety (Peper et al, 2017a; Peper et al, 2016a). Sometimes, a single coaching session can be sufficient to improve health.

Working hypothesis: The headaches were most likely tension headaches and not migraines and may be the result of chronic neck and shoulder tension which was maintained during chest breathing and the slouched head forward body posture. If she could change her posture, relax her neck and shoulders, and breathe diaphragmatically so that the lower abdomen widen during inhalation, most likely her shoulder and neck tension would decrease. Therefore, by changing posture from a slouched to upright position combined with slower diaphragmatic breathing, the muscle tension would be reduced and the headaches would decrease.

Breathing and posture changes

She was encouraged to sit upright so that the abdomen had space to expand (Peper et al., 2020). In addition, she needed to loosen the clothing around her waist to provide room for her abdomen to expand during inhalation instead of her chest lifting (MacHose & Peper, 1991). Allowing abdominal expansion can be challenging for many paticipants since they are self-conscious about their body image, as well holding their stomach in as an unconscious learned response to avoid pain after having had abdominal surgery, or as an automatic protective response to threat (Peper et al., 2015). The upright position also allowed her to sit tall and erect in which the back of head reaches upward towards the ceiling while relaxing and feeling gravity pulling her shoulders downward and at the same time relaxing her hips and legs.

With guided verbal and tactile coaching, she learned to master slower diaphragmatic breathing in which she gently and slowly exhaled by making a sound of pssssssst (exhaling through pursed lips) which tends to activate the transverse and oblique abdominal muscles and slightly tighten the pelvic floor muscles so that her lower abdomen would slightly constrict at the end of the exhalation (Peper et al., 2016). Then, by allowing the lower abdomen and pelvic floor relax so that the abdomen could expand in 360 degrees, inhalation occurred.

While practicing the slower breathing in this relaxed upright position, she was instructed to sense/imagine feeling a flow of down and through her arms and out her hands as she exhaled (as if the air could flow through straws down her arms). After a few minutes, she felt her headache decrease and noticed that her hands had warmed. After this short coaching intervention, she went back to her seat in class and continued to practice the relaxed effortless breathing while sitting upright and allowing her shoulders to melt downward.

The use of muscle feedback to demonstrate residual covert muscle tension

During class session, she volunteered to have her trapezius muscle monitored with electromyography (EMG). The EMG indicated that her muscles were slightly tense even though she reported feeling relaxed. With a few minutes of EMG biofeedback exploration, she discovered that she could relax her shoulder muscles by feeling them being heavy and melting.

Implementing home practice with a posture app

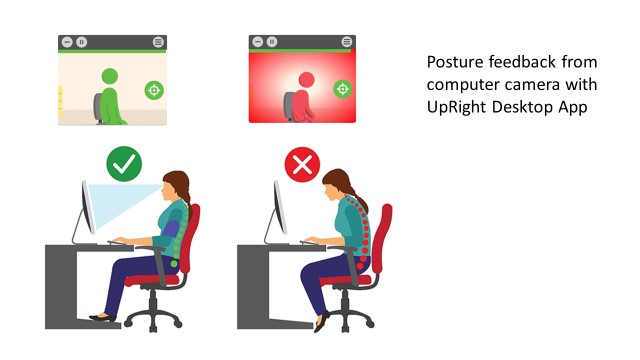

As part of the class homework, she was assigned a self-study for two weeks with the posture feedback app, Dario Desktop. The app uses the computer/laptop camera to monitor posture and provides visual feedback in a small window on the computer screen and/or an auditory signal each time she slouches as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Posture feedback to signal to participant that the person is slouching.

To observe the effect of the posture breathing training, she monitored her symptoms for three days without feedback and then installed the posture feedback application on her laptop to provide feedback whenever she slouched. The posture feedback reminded her to practice better posture during the day while working on her computer and also do a few stretches or shift to standing when using the computer for an extended period of time. Each time the feedback signal indicated she slouched, she would sit up and change her posture, breathe lower and slower and relax her shoulders.

She also monitored what factors triggered the slouching. In additionally, she added daily reminders to her phone to remind her of her posture and to stretch and stand after each hour of studying. After two weeks she recorded her symptoms for three days for the post assessment without posture feedback.

Results

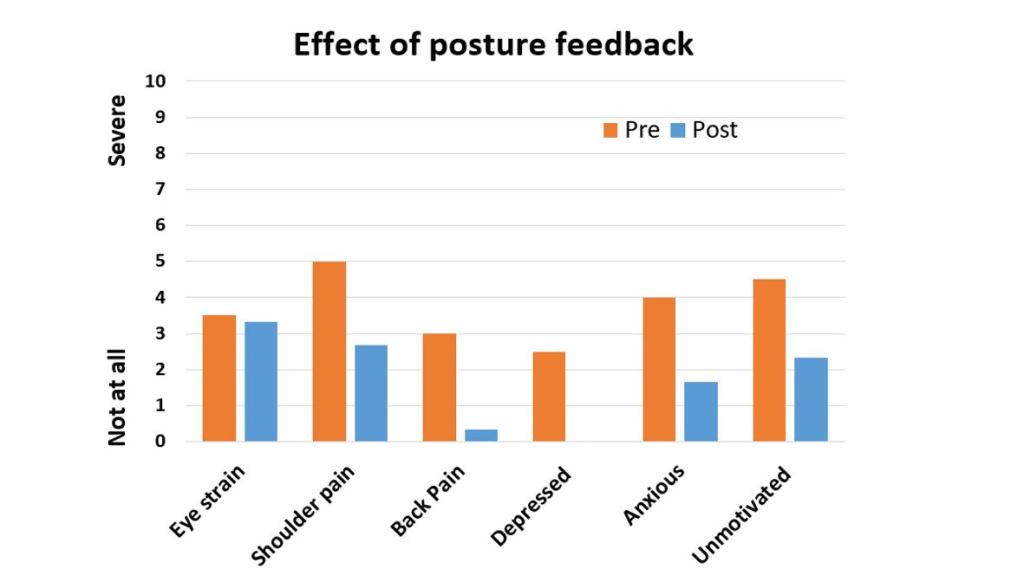

The chronic headache condition which had been present for fourteen years disappeared and she has not used any medication since the first day of class. She reported after two weeks that her shoulder and back discomfort/pain, depression, anxiety and lack of motivation decreased as shown in Figure 2. At the fourteen week follow up, she continues to have no headaches and has not used any medication.

Figure 2. Changes in symptoms after implementing posture feedback for two weeks.

She used the desktop posture app every time she opened her laptop at home as often as 3-5 times per day (roughly 2-6 hours).In addition, when she felt beginning of discomfort or thought she should take medication, she would adjust her posture and breathe. While using the app, she identified numerous factors that were associated with slouching as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Behaviors associated with slouching.

Discussion

The decrease in depression, anxiety and increase in motivation may be the direct result of posture change; since, a slouched position tends to increase hopeless, helpless and powerless thoughts while the upright position tends to increase subjective felt energy and easier access to empowering and positive thoughts (Peper et al., 2017b; Veenstra et al., 2017; Wilson & Peper, 2004; Tsai et al., 2016). Most likely, a major factor that contributed to the elimination of her headaches was that she implemented changes in her behavior. One major factor was using posture feedback tool at home to remind her to sit tall and relax her shoulders while practicing slower diaphragmatic breathing. As she noted, “Although it was distracting to be reminded all the time about my posture, it did decrease my neck pain. With the pain reduction, I was able to sit at the computer longer and felt more motivated.”

The combination of slower lower abdominal breathing with the upright posture reversed her protective/defensive body position (tightening the muscle in the lower abdomen and pelvic floor and pressing the knees together while curling the shoulder forward for protection). The upright posture creates a position of empowerment and trust by which the lower abdomen could expand which supported health and regeneration. In addition, the upright posture allowed easier access to positive thoughts and reduced recall of hopeless, powerless, defeated memories. It is also possible that caffeine withdrawal was a co-factor in evoking headaches (Küçer, 2010). By eliminating the medication containing caffeine, she also eliminated the triggering of the caffeine withdrawal headaches.

This case example suggests that health care providers first rule out any pathology and then teach behavioral self-healing strategies that the clients can implement instead of immediately prescribing medications. These interventions could include slower and lower diaphragmatic breathing, upright posture feedback, muscle biofeedback training, hear rate variability training, stress management, cognitive behavior therapy and facilitating health promoting lifestyles modifications such as regular sleep, exercise and healthier diet. When students implement these behavioral changes as part of a five week self-healing program, many report significant decreases in symptoms such as headaches, anxiety, neck and shoulder pain, and gastrointestinal distress (Peper et al., 2016a).

Watch April Covell describe her experience with the self-healing approach to eliminate her chronic headaches.

See the following blogs for additional instructions how to breathe diaphragmatically.

References

Ahmed, S., Akter, R., Pokhrel, N. et al. (2021). Prevalence of text neck syndrome and SMS thumb among smartphone users in college-going students: a cross-sectional survey study. J Public Health (Berl.) 29, 411–416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-019-01139-4

Bauer, A.Z., Swan, S.H., Kriebel, D. et al. (2021). Paracetamol use during pregnancy — a call for precautionary action. Nat Rev Endocrinol . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-021-00553-7

Charles, N. E., Strong, S. J., Burns, L. C., Bullerjahn, M. R., & Serafine, K. M. (2021). Increased mood disorder symptoms, perceived stress, and alcohol use among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry research, 296, 113706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113706

Elizagaray-Garcia, I., Beltran-Alacreu, H., Angulo-Díaz, S., Garrigós-Pedrón, M., Gil-Martínez, A. (2020). Chronic Primary Headache Subjects Have Greater Forward Head Posture than Asymptomatic and Episodic Primary Headache Sufferers: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Pain Med, 21(10):2465-2480. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnaa235

Greden, J.F., Victor, B.S., Fontaine, P., & Lubetsky, M. (1980). Caffeine-Withdrawal Headache: A Clinical Profile. Psychosomatics, 21(5), 411-413, 417-418. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0033-3182(80)73670-8

Küçer, N. (2010). The relationship between daily caffeine consumption and withdrawal symptoms: a questionnaire-based study. Turk J Med Sci, 40(1), 105-108. https://doi.org/10.3906/sag-0809-26

Kuehn, B.M. (2021). Increase in Myopia Reported Among Children During COVID-19 Lockdown. JAMA, 326(11),999. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.14475

MacHose, M. & Peper, E. (1991). The effect of clothing on inhalation volume. Biofeedback and Self-Regulation 16, 261–265 (1991). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01000020

Peper, E., Booiman, A., Lin, I-M, Harvey, R., & Mitose, J. (2016). Abdominal SEMG Feedback for Diaphragmatic Breathing: A Methodological Note. Biofeedback. 44(1), 42-49. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-44.1.03

Peper, E., Gilbert, C.D., Harvey, R. & Lin, I-M. (2015). Did you ask about abdominal surgery or injury? A learned disuse risk factor for breathing dysfunction. Biofeedback. 34(4), 173-179. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-43.4.06

Peper, E., Lin, I-M., Harvey, R., & Perez, J. (2017b). How posture affects memory recall and mood. Biofeedback. 45 (2), 36-41. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-45.2.01

Peper, E., Mason, L., Harvey, R., Wolski, L, & Torres, J. (2020). Can acid reflux be reduced by breathing? Townsend Letters-The Examiner of Alternative Medicine, 445/446, 44-47. https://www.townsendletter.com/article/445-6-acid-reflux-reduced-by-breathing/

Peper, E., Mason, L., Huey, C. (2017a). Healing irritable bowel syndrome with diaphragmatic breathing. Biofeedback. (45-4). https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-45.4.04

Peper, E., Miceli, B., & Harvey, R. (2016a). Educational Model for Self-healing: Eliminating a Chronic Migraine with Electromyography, Autogenic Training, Posture, and Mindfulness. Biofeedback, 44(3), 130–137. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-44.3.03

Peper, E., Wilson, V., Martin, M., Rosegard, E., & Harvey, R. (2021). Avoid Zoom fatigue, be present and learn. NeuroRegulation, 8(1), 47–56. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.8.1.47

Schulman, E.A. (2002). Breath-holding, head pressure, and hot water: an effective treatment for migraine headache. Headache, 42(10), 1048-50. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1526-4610.2002.02237.x

Tsai, H. Y., Peper, E., & Lin, I. M.* (2016). EEG patterns under positive/negative body postures and emotion recall tasks. NeuroRegulation, 3(1), 23-27. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.3.1.23

Veenstra, L., Schneider, I.K., & Koole, S.L. (2017). Embodied mood regulation: the impact of body posture on mood recovery, negative thoughts, and mood-congruent recall. Cogntion and Emotion, 31(7), 1361-1376. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2016.1225003

Wilson, V.E. and Peper, E. (2004). The effects of upright and slumped postures on the generation of positive and negative thoughts. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 29(3), 189–195. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:apbi.0000039057.32963.34

Education versus treatment for self-healing: Eliminating a headache[1]

Posted: November 18, 2016 Filed under: Pain/discomfort, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: autogenic training, biofeedback, education, electromyography, headache, Holistic health, migraine, posture, treatment 2 Comments“I have had headaches for six years, at first occurring almost every day. When I got put on an antidepressant, they slowed to about 3 times a week (sometimes more) and continued this way until I learned relaxation techniques. I am 20 years old and now headache free. Everyone should have this educational opportunity to heal themselves.” -Melinda, a 20 year old student

Health and wellness is a basic right for all people. When students learn stress management skills which include awareness of stress, progressive muscle relaxation, Autogenic phrases, slower breathing, posture change, transforming internal language, self-healing imagery, the role of diet, exercise embedded within an evolutionary perspective as part of a college class their health often improves. When students systematically applied these self-awareness techniques to address a self-selected illness or health behavior (e.g., eczema, diet, exercise, insomnia, or migraine headaches), 80% reported significant improvement in their health during that semester (Peper et al., 2014b; Tseng, et al., 2016). The semester long program is based upon the practices described in the book, Make Health Happen, (Peper, Gibney, & Holt, 2002).

The benefits often last beyond the semester. Numerous students reported remarkable outcomes at follow-up many months after the class had ended because they had mastered the self-regulation skills and continued to implement these skills into their daily lives. The educational model utilized in holistic health courses is often different from the clinical/treatment model.

Educational approach: I am a student and I have an illness (most of me is healthy and only part of me is sick).

Clinical treatment approach: I am a patient and I am sick (all of me is sick)

Some of the concepts underlying the differences between the educational and the clinical approach are shown in Table 1.

| Educational approach | Clinic/treatment approach |

| Focuses on growth and learning | Focuses on remediation |

| Focuses on what is right | Focuses on what is wrong |

| Focuses on what people can do for themselves | Focuses on how the therapist can help patients |

| Assumes students as being competent | Implies patients are damaged and incompetent |

| Students defined as being competent to master the skills | Patients defined as requiring others to help them |

| Encourages active participation in the healing process | Assumes passive participation in the healing process |

| Students keep logs and write integrative and reflective papers, which encourage insight and awareness | Patients usually do not keep logs nor are asked to reflect at the end of treatment to see which factors contributed to success |

| Students meet in small groups, develop social support and perspective | Patients meet only with practitioners and stay isolated |

| Students experience an increased sense of mastery and empowerment | Patients experience no change or possibly a decrease in sense of mastery |

| Students develop skills and become equal or better than the instructor | Patients are healed, but therapist is always seen as more competent than patient |

| Students can become colleagues and friends with their teachers | Patients cannot become friends of the therapist and thus are always distanced |

Table 1. Comparison of an educational versus clinical/treatment approach

The educational approach focuses on mastering skills and empowerment. As part of the course work, students become more mindful of their health behavior patterns and gradually better able to transform their previously covert harm promoting patterns. This educational approach is illustrated in a case report which describes how a student reduced her chronic migraines.

Case Example: Elimination of Chronic Migraines

Melinda, a 20-year-old female student, experienced four to five chronic migraines per week since age 14. A neurologist had prescribed several medications including Imitrex (used to treat migraines) and Topamax (used to prevent seizures as well as migraine headaches), although they were ineffective in treating her migraines. Nortriptyline (a tricyclic antidepressant) and Excedrin Migraine (which contains caffeine, aspirin, and acetaminophen) reduced the frequency of symptoms to three times per week.

She was enrolled in a university biofeedback class that focused on learning self-regulation and biofeedback skills. All these students were taught the fundamentals of biofeedback and practiced Autogenic Training (AT) every day during the semester (Luthe, 1979; Luthe & Schultz, 1969; Peper & Williams, 1980).

In the class, students practiced with surface electromyography (SEMG) feedback to identify the presence of shoulder muscle overexertion (dysponesis), as well as awareness of minimum muscle tension. Additional practices included hand warming, awareness of thoracic and diaphragmatic breathing, and other biofeedback or somatic awareness approaches. In parallel with awareness of physical sensations, students practiced behavioral awareness such as alternating between a slouching body posture (associated with feeling self-critical and powerless) and an upright body posture (associated with feeling powerful and in control). Psychological awareness was focused on transforming negative thoughts and self-judgments to positive empowering thoughts (Harvey and Peper, 2011; Peper et al., 2014a; Peper et al, 2015). Taken together, students systematically increased awareness of physical, behavioral, and psychological aspects of their reactions to stress.

The major determinant for success is to generalize training at school, home and at work. Each time Melinda felt her shoulders tightening, she learned to relax and release the tension in her shoulders, practiced Autogenic Training with the phrase “my neck and shoulders are heavy.” In addition, whenever she felt her body beginning to slouch or noticed a negative self-critical thought arising in her mind, she shifted her body to an upright empowered posture, and substituted positive thoughts to reduce her cortisol level and increase access to positive thoughts (Carney & Cuddy, 2010; Cuddy, 2012; Tsai, et al., 2016). Postural feedback was also informally given by Melinda’s instructor. Every time the instructor noticed her slouching in class or the hallway, he visually changed his own posture to remind her to be erect.

Results

Melinda’s headaches reduced from between three and five per week before enrolling in the class to zero following the course, as shown in Figure 2. She has learned to shift her posture from slouching to upright and relaxed. In addition, she reported feeling empowered, mentally clear, and her acne cleared up. All medications were eliminated. At a two year follow-up, she reported that since she took the class, she had only few headaches which were triggered by excessive stress.

Figure 2. Frequency of migraine and the implementation of self-practices.

The major factors that contributed to success were:

- Becoming aware of muscle tension through the SEMG feedback. Melinda realized that she had tension when she thought she was relaxed.

- Keeping detailed logs and developing a third person perspective by analyzing her own data and writing a report. A process that encouraged acceptance of self, thereby becoming less judgmental.

- Acquiring a new belief that she could learn to overcome her headaches, facilitated by class lecture and verbal feedback from the instructor.

- Taking active control by becoming aware of the initial negative thoughts or sensations and interrupting the escalating chain of negative thoughts and sensations by shifting the attention to positive empowering thoughts and sensations–a process that integrated mindfulness, acceptance and action. Thus, transforming judgmental thoughts into accepting and positive thoughts.

- Becoming more aware throughout the day, at school and at home, of initial triggers related to body collapse and muscle tension, then changing her body posture and relaxing her shoulders. This awareness was initially developed because the instructor continuously gave feedback whenever she started to slouch in class or when he saw her slouching in the hallways.

- Practicing many, many times during the day. Namely, increasing her ongoing mindfulness of posture, neck, and shoulder tension, and of negative internal dialogue without judgment.

The benefits of this educational approach is captured by Melinda’s summary, “The combined Autogenic biofeedback awareness and skill with the changes in posture helped me remarkably. It improved my self-esteem, empowerment, reduced my stress, and even improved the quality of my skin. It proves the concept that health is a whole system between mind, body, and spirit. When I listen carefully and act on it, my overall well-being is exceptionally improved.”

References:

Carney, D. R., Cuddy, A. J., & Yap, A. J. (2010). Power posing brief nonverbal displays affect neuroendocrine levels and risk tolerance. Psychological Science, 21(10), 1363-1368.

Cuddy, A. (2012). Your body language shapes who you are. Technology, Entertainment, and Design (TED) Talk, available at: http://www.ted.com/talks/amy_cuddy_your_body_language_shapes_who_you_are

Harvey, E. & Peper, E. (2011). I thought I was relaxed: The use of SEMG biofeedback for training awareness and control (pp. 144-159). In W. A. Edmonds, & G. Tenenbaum (Eds.), Case studies in applied psychophysiology: Neurofeedback and biofeedback treatments for advances in human performance. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Luthe, W. (1979). About the methods of autogenic therapy (pp. 167-186). In E. Peper, S. Ancoli, & M. Quinn, Mind/body integration. New York: Springer.

Luthe, W., & Schultz, J.H. (1969). Autogenic therapy (Vols. 1-6). New York, NY: Grune and Stratton.

Peper, E., Booiman, A., Lin, I-M., & Shaffer, F. (2014a). Making the unaware aware-Surface electromyography to unmask tension and teach awareness. Biofeedback. 42(1), 16-23.

Peper, E., Gibney, K.H. & Holt. C. (2002). Make health happen: Training yourself to create wellness. Dubuque, IA: Kendall-Hunt. ISBN-13: 978-0787293314

Peper, E., Lin, I-M, Harvey, R., Gilbert, M., Gubbala, P., Ratkovich, A., & Fletcher, F. (2014b). Transforming chained behaviors: Case studies of overcoming smoking, eczema and hair pulling (trichotillomania). Biofeedback, 42(4), 154-160.

Peper, E., Nemoto, S., Lin, I-M., & Harvey, R. (2015). Seeing is believing: Biofeedback a tool to enhance motivation for cognitive therapy. Biofeedback, 43(4), 168-172. doi: 10.5298/1081-5937-43.4.03

Peper, E. & Williams, E.A. (1980). Autogenic therapy (pp. 131-137). In: A. C. Hastings, J. Fadiman, & J. S. Gordon (Eds.). Health for the whole person. Boulder: Westview Press.

Tsai, H. Y., Peper, E., & Lin, I. M. (2016). EEG patterns under positive/negative body postures and emotion recall tasks. NeuroRegulation, 3(1), 23-27.

Tseng, C., Abili, R., Peper, E., & Harvey, R. (2016). Reducing acne-stress and an integrated self-healing approach. Poster presented at the 47th Annual Meeting of the Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, Seattle WA, March 9-12, 2016.

[1] Adapted from: Peper, E., Miceli, B., & Harvey, R. (2016). Educational Model for Self-healing: Eliminating a Chronic Migraine with Electromyography, Autogenic Training, Posture, and Mindfulness. Biofeedback, 44(3), 130–137. https://biofeedbackhealth.files.wordpress.com/2011/01/a-educational-model-for-self-healing-biofeedback.pdf