Posture and mood: implications and applications to health and therapy

Posted: November 28, 2017 Filed under: Neck and shoulder discomfort, posture, self-healing, Uncategorized | Tags: back pain, electromyography, ergonomics, neck and shoulder tension, posture, spinal alignment, stress management 5 CommentsThis blog has been reprinted from: Peper, E., Lin, I-M, & Harvey, R. (2017). Posture and mood: Implications and applications to therapy. Biofeedback.35(2), 42-48.

Slouched posture is very common and tends to increase access to helpless, hopeless, powerless and depressive thoughts as well as increased head, neck and shoulder pain. Described are five educational and clinical strategies that therapists can incorporate in their practice to encourage an upright/erect posture. These include practices to experience the negative effects of a collapsed posture as compared to an erect posture, watching YouTube video to enhance motivation, electromyography to demonstrate the effect of posture on muscle activity, ergonomic suggestions to optimize posture, the use of a wearable posture biofeedback device, and strategies to keep looking upward. When clients implement these changes, they report a more positive outlook and reduced neck and shoulder discomfort.

Background

Most people slouch without awareness when looking at their cellphone, tablet, or the computer screen (Guan et al., 2016) as shown in Figure 1. Many clients in psychotherapy and in biofeedback or neurofeedback training experience concurrent rumination and depressive thoughts with their physical symptoms. In most therapeutic sessions, clients sit in a comfortable chair, which automatically creates a posterior pelvic tilt and encourages the spine to curve so that the client sits in a slouched position. While at home, they sit on an easy chair or couch, which lets them slouch as they watch TV or surf the web.

Figure 1. (A). Employee working on his laptop. (B). Boy with ADHD being trained with neurofeedback in a clinic. (C). Student looking at cell phone. When people slouch and look at the screen, they tend to slouch and scrunch their neck.

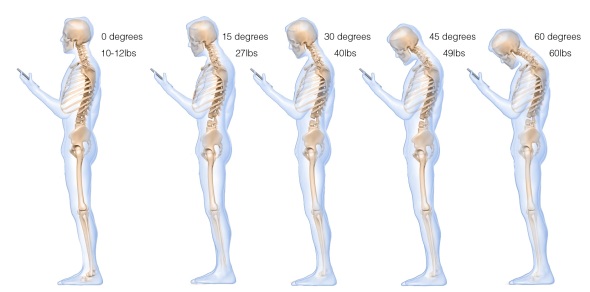

In many cases, the collapsed position also causes people to scrunch their necks, which puts pressure on their necks that may contribute to developing headache or becoming exhausted. Repetitive strain on the neck and cervical spine may trigger a cervical neuromuscular syndrome that involves chronic neck pain, autonomic imbalance and concomitant depression and anxiety (Matsui & Fujimoto, 2011), and may contribute to vertebrobasilar insufficiency –a reduction in the blood supply to the hindbrain through the left and right vertebral arteries and basilar arteries (Kerry, Taylor, Mitchell, McCarthy, & Brew, 2008). From a biomechanical perspective, slouching also places more stress is on the cervical spine, as shown in Figure 2. When the neck compression is relieved, the symptoms decrease (Matsui & Fujimoto, 2011).

Figure 2. The more the head tilts forward, the more stress is placed on the cervical spine. Reproduced by permission from: Hansraj, K. K. (2014). Assessment of stresses in the cervical spine caused by posture and position of the head. Surgical Technology International, 25, 277–279.

Figure 2. The more the head tilts forward, the more stress is placed on the cervical spine. Reproduced by permission from: Hansraj, K. K. (2014). Assessment of stresses in the cervical spine caused by posture and position of the head. Surgical Technology International, 25, 277–279.

Most people are totally unaware of slouching positions and postures until they experience neck, shoulder, and/or back discomfort. Neither clients nor therapists are typically aware that slouching may decrease energy levels and increase the prevalence of negative (hopeless, helpless, powerless, or defeated) memories and thoughts (Peper & Lin, 2012; Peper et al, 2017)

Recommendations for posture awareness and training in treatment/education

The first step in biofeedback training and therapy is to systematically increase awareness and training of posture before attempting further bio/neurofeedback training and/or cognitive behavior therapy. If the client is sitting in a collapsed position in therapy, then it will be much more difficult for them to access positive thoughts, which interferes with further training and effective therapy. For example, research by Tsai, Peper, & Lin (2016) showed that engaging in positive thinking while slouched requires greater mental effort then when sitting erect. Sitting erect and tall contributes to elevated mood and positive thinking. An upright posture supports positive outcomes that may be akin to the beneficial effects of exercise for the treatment of depression (Schuch, Vancampfort, Richards, Rosenbaum, Ward, & Stubbs., 2016).

Most people know that posture affects health; however, they are unaware of how rapidly a slouching posture can impact their physical and mental health. We recommend the following educational and clinical strategies to teach this awareness.

- Practicing activities that raise awareness about a collapsed posture as compared to an erect posture

Guide clients through the practices so that they experience how posture can affect memory recall, physical strength, energy level, and possible triggering of headaches.

A. The effect of collapsed and erect posture on memory recall. Participants reported that it is much easier evoke powerless, hopeless, helpless, and defeated memories when sitting in a collapsed position than when sitting upright. Guide the client through the procedure described in the article, How posture affects memory recall and mood (Peper, Lin, Harvey, and Perez, 2017) and in the blog Posture affects memory recall and mood.

B. The effects of collapsed and erect posture on perceived physical strength. Participants experience much more difficulty in resisting downward pressure at the wrist of an outstretched arm when slouched rather than upright. Guide the client through the exercise described in the article, Increase strength and mood with posture (Peper, Booiman, Lin, & Harvey, 2016) and the blog, Increase strength and mood with posture.

C. The effect of slouching versus skipping on perceived energy levels. Participants experience a significant increase in subjective energy after skipping than walking slouched. Guide the client through the exercises as described in the article, Increase or decrease depression—How body postures influence your energy level (Peper & Lin, 2012).

D. The effect of neck compression to evoke head pressure and headache sensations. In our unpublished study with students and workshop participants, almost all participants who are asked to bring their head forward, then tilt the chin up and at the same time compress the neck (scrunching the neck), report that within thirty seconds they feel a pressure building up in the back of the head or the beginning of a headache. To their surprise, it may take up to 5 to 20 minutes for the discomfort to disappear. Practicing similar awareness activities can be a useful demonstration for clients with dizziness or headaches to experience how posture can increase their symptoms.

- Watching a Youtube video to enhance motivation.

Have clients watch Professor Amy Cuddy’s 2012 TED (Technology, Entertainment, and Design) Talk, Your body language shape who you are, which describes the hormonal changes that occur when adapting a upright power versus collapsed defeated posture.

- Electromyographic (EMG) feedback to demonstrate how posture affects muscle activity.

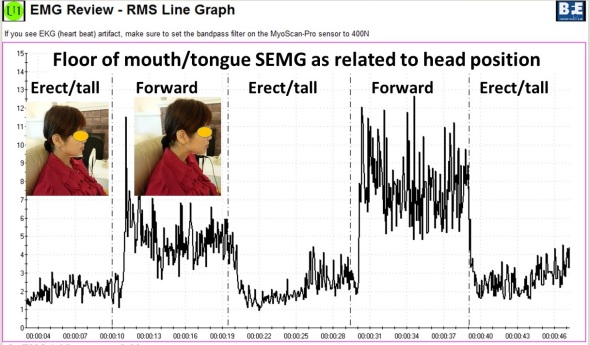

Record EMG from muscles such as around the cervical spine, trapezius, frontalis, and masseters or beneath the chin (submental lead) to demonstrate that having the head is forward and/or the neck compressed will increase EMG activity, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Electromyographic recording of the muscle under the chin while alternating between bringing the head forward or holding it back, feeling erect and tall.

The client can then learn awareness of the head and neck position. For example, one client with severe concussion experienced significant increase in head pressure and dizziness when she slouched or looked at a computer screen as well as feeling she would never get better. She then practiced the exercise of alternating her awareness by bringing her head forward and then back, and then bringing her neck back while her chin was down, thereby elongating the neck while she continued to breathe. With her head forward, she would feel her molars touching and with her neck back she felt an increase in space between the molars. When she elongated her neck in an erect position, she felt the pressure draining out of her head and her dizziness and tinnitus significantly decrease.

- Assessing ergonomics to optimize posture.

Change the seated posture of both the therapist and the client during treatment and training. Although people may be aware of their posture, it is much easier to change the external environment so that they automatically sit in a more erect power posture. Possible options include:

A. Seat insert or cushions. Sit in upright chairs that encourage an anterior pelvic tilt by having the seat pan slightly lower in the front than in the back or using a seat insert to facilitate a more erect posture (Schwanbeck, Peper, Booiman, Harvey, & Lin, 2015) as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. An example of how posture can be impacted covertly when one sits on a seat insert that rotates the pelvis anteriorly (The seat insert shown in the diagram and used in research is produced by BackJoy™).

B. Back cushion. Place a small pillow or rolled up towel at the kidney level so that the spine is slight arched, instead of sitting collapsed, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. An example of how a small pillow, placed between the back of the chair and the lower back, changes posture from collapsed to erect.

Figure 5. An example of how a small pillow, placed between the back of the chair and the lower back, changes posture from collapsed to erect.

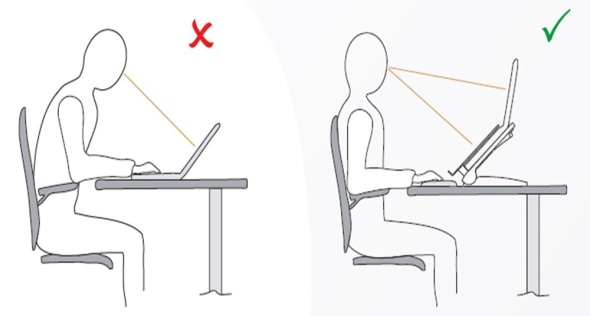

C. Check ergonomic and work site computer use to ensure that the client can sit upright while working at the computer. For some, that means checking their vision if they tend to crane forward and crunch their neck to read the text. For those who work on laptops, it means using either an external keyboard, a monitor, or a laptop stand so the screen is at eye level, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Posture is collapsed when working on a laptop and can be improved by using an external keyboard and monitor. Reproduced by permission from: Bakker Elkhuizen. (n.d.). Office employees are like professional athletes! (2017).

Figure 6. Posture is collapsed when working on a laptop and can be improved by using an external keyboard and monitor. Reproduced by permission from: Bakker Elkhuizen. (n.d.). Office employees are like professional athletes! (2017).

- Wearable posture biofeedback training device

The wearable biofeedback device, UpRight™, consists of a small sensor placed on the spine and works as an app on the cell phone. After calibration the erect and slouched positions, the posture device gives vibratory feedback each time the participant slouches, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Illustration of a posture feedback device, UpRight™. It provides vibratory feedback to the wearer to indicate that they are beginning to slouch.

Clinically, we have observed that clients can learn to identify conditions that are associated with slouching, such as feeling tired, thinking depressive/hopeless thoughts or other situations that evoke slouching. When people wear a posture feedback device during the day, they rapidly become aware of these subjective experiences whenever they slouch. The feedback reminds them to sit in an erect position, and they subsequently report an improvement in health (Colombo et al., 2017). For example, a 26-year-old man who works more than 8 hours a day on computer reported, “I have an improved awareness of my posture throughout my day. I also notice that I had less back pain at the end of the day.”

- Integrating posture awareness and position changes throughout the day

After clients have become aware of their posture, additional training included having them observe their posture as well and negative changes in mood, energy level or tension in their neck and head. When they become aware of these changes, they use it as a cue to slightly arch their back and look upward. If possible have the clients look outside at the tops of trees and notice details such as how the leaves and branches move. Looking at the details interrupts any ongoing rumination. At the same time, have them think of an uplifting positive memory. Then have them take another breath, wiggling, and return to the task at hand. Recommend to clients to go outside during breaks and lunchtime to look upward at the trees, the hills, or the clouds. Each time one is distracted, return to appreciate the natural patterns. This mental break concludes by reminding oneself that humans are like trees.

Trees are rooted in the earth and reach upward to the light. Despite the trauma of being buffeted by the storms, they continue to reach upward. Similarly, clouds reflect the natural beauty of the world, and are often visible in the densest city environment. The upward movement reflects our intrinsic resilience and growth. –Erik Peper

Have clients place family photos and art slightly higher on the wall at home so they automatically look upward to see the pictures. A similar strategy can be employed in the office, using art to evoke positive feelings. When clients integrate an erect posture into their daily lives, they experience a more positive outlook and reduced neck and shoulder discomfort.

Compliance with Ethical Standards:

Conflict of Interest: Author Erik Peper has received donations of 15 UpRight posture feedback devices from UpRight (http://www.uprightpose.com/) and 12 BackJoy seat inserts from Backjoy (https://www.backjoy.com) for use in research. Co-authors I-Mei Lin and Richard Harvey declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This report evaluated a convenience sample of a student classroom activity related to posture and the information was anonymous collected. As an evaluation of a classroom activity, this report of findings was exempted from Institutional Review Board oversight

References:

Bakker Elkhuizen. (n.d.). Office employees are like professional athletes! (2017). Retrieved from https://www.bakkerelkhuizen.com/knowledge-center/whitepaper-improving-work-performance-with-insights-from-pro-sports/

Cuddy, A. (2012). Your body language shapes who you are. Technology, Entertainment, and Design (TED) Talk, available at: www.ted.com/talks/amy_cuddy_your_body_language_shapes_who_you_are

We thank Frank Andrasik for his constructive comments.

Posture affects memory recall and mood

Posted: November 25, 2017 Filed under: Exercise/movement, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: cognitive therapy, depression, empowerment, energy, helplessness, memory, mood, posture, power posture, somatics 5 CommentsThis blog has been reprinted from: Peper, E., Lin, I-M., Harvey, R., & Perez, J. (2017). How posture affects memory recall and mood. Biofeedback, 45 (2), 36-41.

When I sat collapsed looking down, negative memories flooded me and I found it difficult to shift and think of positive memories. While sitting erect, I found it easier to think of positive memories. -Student participant

The link between posture and mood is embedded in idiomatic phrases such as walking tall, standing proud, and an upstanding citizen, versus collapsed, defeated, or in a slump–Language suggests that posture and mood/emotions are connected. Slumped posture is commonly observed in depression (Canales et al., 2010; Michalak et al., 2009) and adapting an upright posture increases positive affect, reduces fatigue, and increases energy in people with mild to moderate depression (Wilkes et al., 2017; Peper & Lin, 2012).

The link between posture and mood is embedded in idiomatic phrases such as walking tall, standing proud, and an upstanding citizen, versus collapsed, defeated, or in a slump–Language suggests that posture and mood/emotions are connected. Slumped posture is commonly observed in depression (Canales et al., 2010; Michalak et al., 2009) and adapting an upright posture increases positive affect, reduces fatigue, and increases energy in people with mild to moderate depression (Wilkes et al., 2017; Peper & Lin, 2012).

This blog describes in detail our research study that demonstrated how posture affects memory recall (Peper et al, 2017). Our findings may explain why depression is increasing the more people use cell phones. More importantly, learning posture awareness and siting more upright at home and in the office may be an effective somatic self-healing strategy to increase positive affect and decrease depression.

Background

Most psychotherapies tend to focus on the mind component of the body-mind relationship. On the other hand, exercise and posture focus on the body component of the mind/emotion/body relationship. Physical activity in general has been demonstrated to improve mood and exercise has been successfully used to treat depression with lower recidivism rates than pharmaceuticals such as sertraline (Zoloft) (Babyak et al., 2000). Although the role of exercise as a treatment strategy for depression has been accepted, the role of posture is not commonly included in cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) or biofeedback or neurofeedback therapy.

The link between posture, emotions and cognition to counter symptoms of depression and low energy have been suggested by Wilkes et al. (2017) and Peper and Lin (2012), . Peper and Lin (2012) demonstrated that if people tried skipping rather than walking in a slouched posture, subjective energy after the exercise was significantly higher. Among the participants who had reported the highest level of depression during the last two years, there was a significant decrease of subjective energy when they walked in slouched position as compared to those who reported a low level of depression. Earlier, Wilson and Peper (2004) demonstrated that in a collapsed posture, students more easily accessed hopeless, powerless, defeated and other negative memories as compared to memories accessed in an upright position. More recently, Tsai, Peper, and Lin (2016) showed that when participants sat in a collapsed position, evoking positive thoughts required more “brain activation” (i.e. greater mental effort) compared to that required when walking in an upright position.

Even hormone levels also appear to change in a collapsed posture (Carney, Cuddy, & Yap, 2010). For example, two minutes of standing in a collapsed position significantly decreased testosterone and increased cortisol as compared to a ‘power posture,’ which significantly increased testosterone and decreased cortisol while standing. As Professor Amy Cuddy pointed out in herTechnology, Entertainment and Design (TED) talk, “By changing posture, you not only present yourself differently to the world around you, you actually change your hormones” (Cuddy, 2012). Although there appears to be controversy about the results of this study, the overall findings match mammalian behavior of dominance and submission. From my perspective, the concepts underlying Cuddy’s TED talk are correct and are reconfirmed in our research on the effect of posture. For more detail about the controversy, see the article by Susan Dominusin in the New York Times, “When the revolution came for Amy Cuddy,”, and Amy Cuddy’s response (Dominus, 2017;Singal and Dahl, 2016).

The purpose of our study is to expand on our observations with more than 3,000 students and workshop participants. We observed that body posture and position affects recall of emotional memory. Moreover, a history of self-described depression appears to affect the recall of either positive or negative memories.

Method

Subjects: 216 college students (65 males; 142 females; 9 undeclared), average age: 24.6 years (SD = 7.6) participated in a regularly planned classroom demonstration regarding the relationship between posture and mood. As an evaluation of a classroom activity, this report of findings was exempted from Institutional Review Board oversight.

Procedure

While sitting in a class, students filled out a short, anonymous questionnaire, which asked them to rate their history of depression over the last two years, their level of depression and energy at this moment, and how easy it was for them to change their moods and energy level (on a scale from 1–10). The students also rated the extent they became emotionally absorbed or “captured” by their positive or negative memory recall. Half of the students were asked to rate how they sat in front of their computer, tablet, or mobile device on a scale from 1 (sitting upright) to 10 (completely slouched).

Two different sitting postures were clearly defined for participants: slouched/collapsed and erect/upright as shown in Figure 1. To assume the collapsed position, they were asked to slouch and look down while slightly rounding the back. For the erect position, they were asked to sit upright with a slight arch in their back, while looking upward.

Figure 1. Sitting in a collapsed position and upright position (photo by Jana Asenbrennerova). Reprinted by permission from Gorter and Peper (2011).

Figure 1. Sitting in a collapsed position and upright position (photo by Jana Asenbrennerova). Reprinted by permission from Gorter and Peper (2011).

After experiencing both postures, half the students sat in the collapsed position while the other half sat in the upright position. While in this position, they were asked to recall/evoke as many hopeless, helpless, powerless, or defeated memories as possible, one after the other, for 30 seconds.

After 30 seconds they were reminded to keep their same position and let go of thinking negative memories. They were then asked to recall/evoke only positive, optimistic, or empowering memories for 30 seconds.

They were then asked to switch positions. Those who were collapsed switched to sitting erect, and those who were erect switched to sitting collapsed. Then they were again asked to recall/evoke as many hopeless, helpless, powerless, or defeated memories as possible one after the other for 30 seconds. After 30 seconds they were reminded to keep their same position and again let go of thinking of negative memories. They were then asked to recall/evoke only positive, optimistic, or empowering memories for 30 seconds, while still retaining the second posture.

They then rated their subjective experience in recalling negative or positive memories and the degree to which they were absorbed or captured by the memories in each position, and in which position it was easier to recall positive or negative experiences.

Results

86% of the participants reported that it was easier to recall/access negative memories in the collapsed position than in the erect position, which was significantly different as determined by one-way ANOVA (F(1,430)=110.193, p < 0.01) and 87% of participants reported that it was easier to recall/access positive images in the erect position than in the collapsed position, which was significantly different as determined by one-way ANOVA (F(1,430)=173.861, p < 0.01) as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Percent of respondents who reported that it was easier to recall positive or negative memories in an upright or slouched posture.

Figure 2. Percent of respondents who reported that it was easier to recall positive or negative memories in an upright or slouched posture.

The difficulty or ease of recalling negative or positive memories varied depending on position as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. The relative subjective rating in the ease or difficulty of recalling negative and positive memories in collapsed and upright positions.

Figure 3. The relative subjective rating in the ease or difficulty of recalling negative and positive memories in collapsed and upright positions.

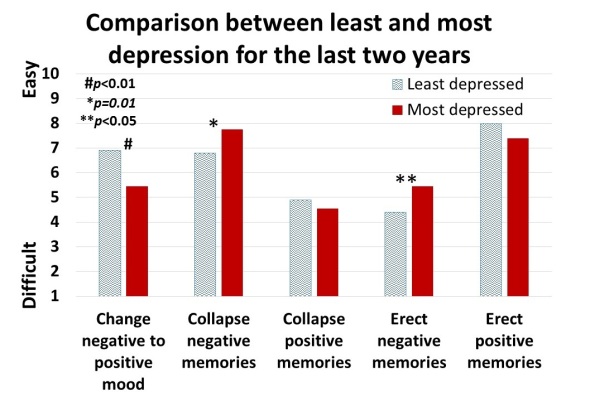

The participants with a high level of depression over the last two years (top 23% of participants who scored 7 or higher on the scale of 1–10) reported that it was significantly more difficult to change their mood from negative to positive (t(110) = 4.08, p < 0.01) than was reported by those with a low level of depression (lowest 29% of the participants who scored 3 or less on the scale of 1–10). It was significantly easier for more depressed students to recall/evoke negative memories in the collapsed posture (t(109) = 2.55, p = 0.01) and in the upright posture (t(110) = 2.41, p ≦0.05 he) and no significant difference in recalling positive memories in either posture, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Differences is in memory access for participants with a history of least or most depression.

Figure 4. Differences is in memory access for participants with a history of least or most depression.

For all participants, there was a significant correlation (r = 0.4) between subjective energy level and ease with which they could change from negative to positive mood. There were no significance differences for gender in all measures except that males reported a significantly higher energy level than females (M = 5.5, SD = 3.0 and M = 4.7, SD = 3.8, respectively; t(203) = 2.78, p < 0.01).

A subset of students also had rated their posture when sitting in front of a computer or using a digital device (tablet or cell phone) on a scale from 1 (upright) to 10 (completely slouched). The students with the highest levels of depression over the last two years reporting slouching significantly more than those with the lowest level of depression over the last two years (M = 6.4, SD = 3.5 and M = 4.6, SD = 2.6; t(46) = 3.5, p < 0.01).

There were no other order effects except of accessing fewer negative memories in the collapsed posture after accessing positive memories in the erect posture (t(159)=2.7, p < 0.01). Approximately half of the students who also rated being “captured” by their positive or negative memories were significantly more captured by the negative memories in the collapsed posture than in the erect posture (t(197) = 6.8, p < 0.01) and were significantly more captured by positive memories in the erect posture than the collapsed posture (t(197) = 7.6, p < 0.01), as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Subjective rating of being captured by negative and positive memories depending upon position.

Figure 5. Subjective rating of being captured by negative and positive memories depending upon position.

Discussion

Posture significantly influenced access to negative and positive memory recall and confirms the report by Wilson and Peper (2004). The collapsed/slouched position was associated with significantly easier access to negative memories. This is a useful clinical observation because ruminating on negative memories tends to decrease subjective energy and increase depressive feelings (Michi et al., 2015). When working with clients to change their cognition, especially in the treatment of depression, the posture may affect the outcome. Thus, therapists should consider posture retraining as a clinical intervention. This would include teaching clients to change their posture in the office and at home as a strategy to optimize access to positive memories and thereby reduce access or fixation on negative memories. Thus if one is in a negative mood, then slouching could maintain this negative mood while changing body posture to an erect posture, would make it easier to shift moods.

Physiologically, an erect body posture allows participants to breathe more diaphragmatically because the diaphragm has more space for descent. It is easier for participants to learn slower breathing and increased heart rate variability while sitting erect as compared to collapsed, as shown in Figure 6 (Mason et al., 2017).

Figure 6. Effect of posture on respiratory breathing pattern and heart rate variability.

Figure 6. Effect of posture on respiratory breathing pattern and heart rate variability.

The collapsed position also tends to increase neck and shoulder symptoms This position is often observed in people who work at the computer or are constantly looking at their cell phone—a position sometimes labeled as the i-Neck.

Implication for therapy

In most biofeedback and neurofeedback training sessions, posture is not assessed and clients sit in a comfortable chair, which automatically causes a slouched position. Similarly, at home, most clients sit on an easy chair or couch, which lets them slouch as they watch TV or surf the web. Finally, most people slouch when looking at their cellphone, tablet, or the computer screen (Guan et al., 2016). They usually only become aware of slouching when they experience neck, shoulder, or back discomfort.

Clients and therapists are usually not aware that a slouched posture may decrease the client’s energy level and increase the prevalence of a negative mood. Thus, we recommend that therapists incorporate posture awareness and training to optimize access to positive imagery and increase energy.

References

Singal, J. and Dahl, M. (2016, Sept 30 ) Here Is Amy Cuddy’s Response to Critiques of Her Power-Posing Research. https://www.thecut.com/2016/09/read-amy-cuddys-response-to-power-posing-critiques.html

We thank Frank Andrasik for his constructive comments.

Breathing to improve well-being

Posted: November 17, 2017 Filed under: Breathing/respiration, Exercise/movement, Neck and shoulder discomfort, Pain/discomfort, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: anxiety, Breathing, health, mindfulness, pain, respiration, stress 8 CommentsBreathing affects all aspects of your life. This invited keynote, Breathing and posture: Mind-body interventions to improve health, reduce pain and discomfort, was presented at the Caribbean Active Aging Congress, October 14, Oranjestad, Aruba. www.caacaruba.com

The presentation includes numerous practices that can be rapidly adapted into daily life to improve health and well-being.