Quick Rescue Techniques When Stressed

Posted: February 4, 2024 Filed under: attention, behavior, biofeedback, Breathing/respiration, CBT, cognitive behavior therapy, education, emotions, Evolutionary perspective, Exercise/movement, health, mindfulness, Neck and shoulder discomfort, posture, relaxation, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: alarm reaction, anxiety, box breathing, Breathing, conditioning, defense reaction, health, huming, Parasympathetic response, rumination, safety, sniff inhale, somatic practices, stress, sympathetic arousal, tactical breathing, Toning, yoga 2 CommentsErik Peper, PhD, Yuval Oded, PhD, and Richard Harvey, PhD

Adapted from Peper, E., Oded, Y, & Harvey, R. (2024). Quick somatic rescue techniques when stressed. Biofeedback, 52(1).

“If a problem is fixable, if a situation is such that you can do something about it, then there is no need to worry. If it’s not fixable, then there is no help in worrying. There is no benefit in worrying whatsoever.” ― Dalai Lama XIV

To implement the Dalai Lama’s quote is challenging. When caught up in an argument, being angry, extremely frustrated, or totally stressed, it is easy to ruminate, worry. It is much more challenging to remember to stay calm. When remembering the message of the Dalai Lama’s quote, it may be possible to shift perspective about the situation although a mindful attitude may not stop ruminating thoughts. The body typically continues to reacti to the torrents of thoughts that may occur when rehashing rage over injustices, fear over physical or psychological threats, or profound grief and sadness over the loss of a family member. Some people become even more agitated and less rational as illustrated in the following examples.

I had an argument with my ex and I am still pissed off. Each time I think of him or anticipate seeing them, my whole body tightened. I cannot stomach seeing him and I already see the anger in his face and voice. My thoughts kept rehashing the conflict and I am getting more and more upset.

A car cut right in front of me to squeeze into my lane. I had to slam on my brakes. What an idiot! My heart rate was racing and I wanted to punch the driver.

When threatened, we respond quickly in our thoughts and body with a defense reaction that may negatively affect those around us as well as ourselves. What can we do to interrupt negative stress reactions?

Background

Many approaches exist that allow us to become calmer and less reactive. General categories include techniques of cognitive reappraisal (seeing the situation from the other person’s point of view and labeling your own feelings and emotions) and stress management techniques. Practices that are beneficial include mindfulness meditation, benign humor (versus gallows humor), listening to music, taking a time out while implementing a variety of self-soothing practices, or incorporating slow breathing (e.g., heart rate variability and/or box breathing) throughout the day.

No technique fits all as we respond differently to our stressful life circumstances. For example, some people during stress react with a “tend and befriend stress response” (Cohen & Lansing, 2021; Taylor et al., 2000). This response appears to be mostly mediated by the hormone oxytocin acting in ways that sooth or calm the nervous system as an analgesic. These neurophysiological mechanisms of the soothing with the calming analgesic effects of oxytocin have been characterized in detail by Xin, et al. (2017).

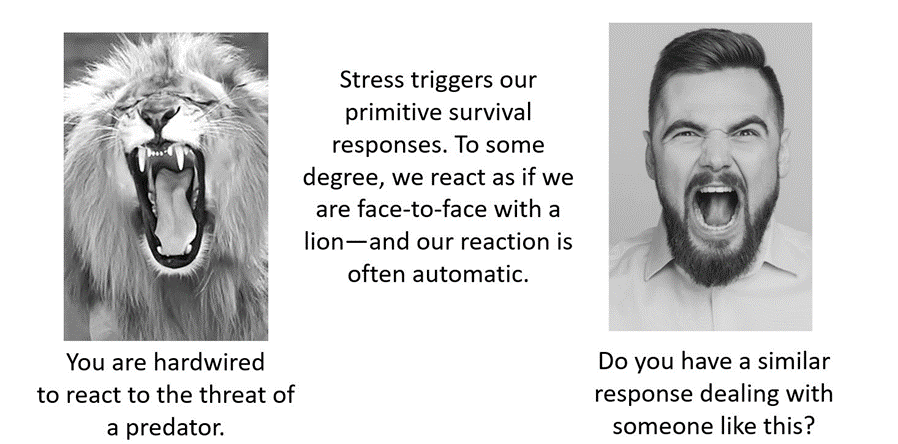

The most common response is a fight/flight/freeze stress response that is mediated by excitatory hormones such as adrenalin and inhibitory neurotransmitters such as gamma amino butyric acid (GABA). There is a long history of fight/flight/freeze stress response research, which is beyond the scope of this blog with major theories and terms such as interior milleau (Bernard, 1872); homeostasis and fight/flight (Cannon, 1929); general adaptation syndrome (Selye, 1951); polyvagal theory (Porges, 1995); and, allostatic load (McEwen, 1998). A simplified way to start a discussion about stress reactions begins with the fight/flight stress response. When stressed our defense reactions are triggered. Our sympathetic nervous system becomes activated our mind and body stereotypically responds as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. An intense confrontation tends to evoke a stress response (reproduced from Peper et al., 2020).

The flight/fight response triggers a cascade of stress hormones or neurotransmitters (e.g., hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal cascade) and produces body changes such as the heart pounding, quicker breathing, an increase in muscle tension and sweating. Our body mobilizes itself to protect itself from danger. Our focus is on immediate survival and not what will occur in the future (Porges, 2021; Sapolsky, 2004). It is as if we are facing an angry lion—a life-threatening situation—and we feel threatened and unsafe.

Rather than sitting still, a quick effective strategy is to interrupt this fight/flight response process by completing the alarm reaction such as by moving our muscles (e.g., simulating a fight or flight behavior) before continuing with slower breathing or other self-soothing strategies. Many people have experienced their body tension is reduced and they feel calmer when they do vigorous exercise after being upset, frustrated or angry. Similarly, athletes often have reported that they experience reduced frequency and/or intensity of negative thoughts after an exhausting workout (Thayer, 2003; Liao et al., 2015; Basso & Suzuki, 2017).

Becoming aware of the escalating cascades of physical, behavioral and psychological responses to a stressor is the first step in interrupting the escalating process. After becoming aware, reduce the body’s arousal and change the though patterns using any of the techniques described in this blog. The self-regulation skills presented in this blog are ideally over-learned and automated so that these skills can be rapidly implemented to shift from being stressed to being calm. Examples of skills that can shift from sympathetic neervous system overarousal to parasympathetic nervous system calm include techniques of autogenic traing (Schulz & Luthe, 1959), the quieting reflex developed by Charles Stroebel in 1985 or more recently rescue breathing developed by Richard Gevirtz (Stroebel, 1985; Gevirtz, 2014; Peper, Gibney & Holt, 2002; Peper & Gibney, 2003).

Concepts underlying the rescue techniques

- Psychophysiological principle: “Every change in the physiological state is accompanied by an appropriate change in the mental-emotional state, conscious or unconscious, and conversely, every change in the mental-emotional state, conscious or unconscious, is accompanied by an appropriate change in the physiological state” (Green et al. 1970, p. 3).

- Posture evokes memories and feelings associated with the position. When the body posture is erect and tall while looking slightly up. It is easier to evoke empowering, positive thoughts and feelings. When looking down it is easier to evoke hopeless, helpless and powerless thoughts and feelings (Peper et al., 2017).

- Healing occurs more easily when relaxed and feeling safe. Feeling safe and nurtured enhances the parasympathetic state and reduces the sympathetic state. Use memory recall to evoke those experiences when you felt safe (Peper, 2021).

- Interrupting thoughts is easier with somatic movement than by redirecting attention and thinking of something else without somatic movement.

- Focus on what you want to do not want to do. Attempting to stop thinking or ruminating about something tends to keeps it present (e.g., do not think of pink elephants. What color is the elephant? When you answer, “not pink,” you are still thinking pink). A general concept is to direct your attention (or have others guide you) to something else (Hilt & Pollak, 2012; Oded, 2018; Seo, 2023).

- Skill mastery takes practice and role rehearsal (Lally et al., 2010; Peper & Wilson, 2021).

- Use classical conditioning concepts to facilitate shifting states. Practice the skills and associate them with an aroma, memory, sounds or touch cues. Then when you the situation occurs, use these classical conditioned cues to facilitate the regeneration response (Peper & Wilson, 2021).

Rescue techniques

Coping When Highly Stressed and Agitated

- Complete the alarm/defense reaction with physical activity (Be careful when you do these physical exercises if you have back, hip, knee, or ankle problems).

- Acknowledge you have reacted and have chosen to interrupt your automatic response.

- Check whether the situation is actually a threat. If yes, then do anything to get out of immediate danger (yell, scream, fight, run away, or dial 911).

- If there is no actual physical threat, then leave the situation and perform vigorous physical activity to complete your alarm reaction, such as going for a run or walking quickly up and down stairs. As you do the exercise, push yourself so that the muscles in your thighs are aching, which focusses your attention on the sensations in your thighs. In our experience, an intensive run for 20 minutes quiets the brain while it often takes 40 minutes when walking somewhat quickly.

- After recovering from the exhaustive exercise, explore new options to resolve the conflict.

- Complete the alarm/defense reaction and evoke calmness with the S.O.S™ technique (Oded, 2023)

- Acknowledge you have reacted and have chosen to interrupt your automatic response.

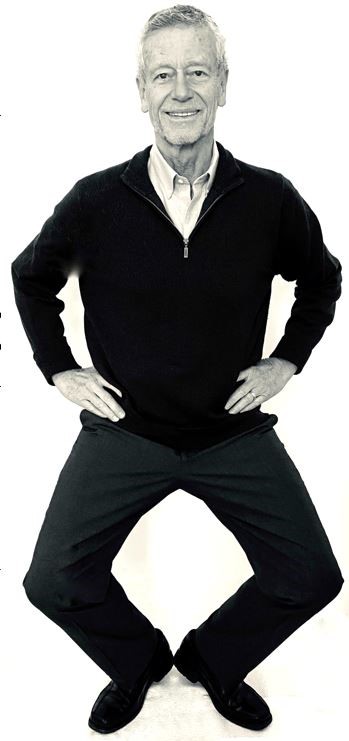

- Squat against a wall (similar to the wall-sit many skiers practice). While tensing your arms and fists as shown in Figure 2, gaze upward because it is more difficult to engage in negative thinking while looking upwards. If you continue to ruminate, then scan the room for object of a certain color or feature to shift visual attention and be totally present on the visual object.

- Do this set of movements for 7 to 10 seconds or until you start shaking. Than stand up and relax hands and legs. While standing, bounce up and down loosely for 10 to 15 seconds as you become aware of the vibratory sensations in your arms and shoulders, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2.Defense position wall-sit to tighten muscles in the protective defense posture (Oded, 2023). Figure 3. Bouncing up and down to loosen muscles ((Oded, 2023).

- Acknowledge you have reacted and have chosen to interrupt your automatic response. Swing your arms back and forth for 20 seconds. Allow the arms to swing freely as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Swinging the arms to loosen the body and spine (Oded, 2023).

- Rest and ground. Lie on the floor and put your calves and feet on a chair seat so that the psoas muscle can relax, as illustrated in Figure 5. Allow yourself to be totally supported by the floor and chair. Be sure there is a small pillow under your head and put your hand on your abdomen so that you can focus on abdominal breathing.

Figure 5. Lying down to allow the psoas muscle to relax and feel grounded (Oded, 2023).

- While lying down, imagine a safe place or memory and make it as real as possible. It is often helpful to listen to a guided imagery or music. The experience can be enhanced if cues are present that are associated with the safe place, such as pictures, sounds, or smells. Continue to breathe effortlessly at about six breaths per minute. If your attention wanders, bring it back to the memory or to the breathing. Allow yourself to rest for 10 minutes.

In most cases, thoughts stop and the body’s parasympathetic activity becomes dominant as the person feels safe and calm. Usually, the hands warm and the blood volume pulse amplitude increases as an indicator of feeling safe, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Blood volume pulse increases as the person is relaxing, feels safe and calm.

Coping When You Can’t Get Away (adapted from Peper, Harvey & Faass, 2020)

In many cases, it is difficult or embarrassing to remove yourself from the situation when you are stressed out such as at work, in a business meeting or social gathering.

- Become aware that you have reacted.

- Excuse yourself for a moment and go to a private space, such as a restroom. Going to the bathroom is one of the only acceptable social behaviors to leave a meeting for a short time.

- In the bathroom stall, do the 5-minute Nyingma exercise, which was taught by Tarthang Tulku Rinpoche in the tradition of Tibetan Buddhism, as a strategy for thought stopping (see Figure 7). Stand on your toes with your heels touching each other. Lift your heels off the floor while bending your knees. Place your hands at your sides and look upward. Breathe slowly and deeply (e.g., belly breathing at six breaths a minute) and imagine the air circulating through your legs and arms. Do this slow breathing and visualization next to a wall so you can steady yourself if necessary to keep balance. Stay in this position for 5 minutes or longer. Do not straighten your legs—keep squatting despite the discomfort. In a very short time, your attention is captured by the burning sensation in your thighs. Continue. After 5 minutes, stop and shake your arms and legs.

Figure 7. Stressor squat Nyingma exercise (reproduced from Peper et al., 2020).

- Follow this practice with slow abdominal breathing to enhance the parasympathetic response. Be sure that the abdomen expands as the inhalation occurs. Breathe in and out through the nose at about six breaths per minute.

- Once you feel centered and peaceful, return to the room.

- After this exercise, your racing thoughts most likely will have stopped and you will be able to continue your day with greater calm.

What to do When Ruminating, Agitated, Anxious or Depressed

(adapted from Peper, Harvey, & Hamiel, 2019).

- Shift your position by sitting or standing erect in a power position with the back of the head reaching upward to the ceiling while slightly gazing upward. Then sniff quickly through nose, hold and again sniff quickly then very slowly exhale. Be sure as you exhale your abdomen constricts. Then sniff again as your abdomen gets bigger, hold, and sniff one more time letting the abdomen get even bigger. Then, very slow, exhale through the nose to the internal count of six (adapted from Balban et al., 2023). When you sniff or gasp, your racing thoughts will stop (Peper et al., 2016).

- Continue with box breathing (sometimes described as tactical breathing or battle breathing) by exhaling slowly through your nose for 4 seconds, holding your breath for 4 seconds, inhaling slowly for 4 seconds through your nose, holding your breath for 4 seconds and then repeating this cycle of breathing for a few minutes (Röttger et al., 2021; Balban et al., 2023). Focusing your attention on performing the box breathing makes it almost impossible to think of anything else. After a few minutes, follow this with slow effortless diaphragmatic breathing at about six breaths per minute. While exhaling slowly through your nose, look up and when you inhale imagine the air coming from above you. Then as you exhale, imagine and feel the air flowing down and through your arms and legs and out the hands and feet.

- While gazing upward, elicit a positive memory or a time when you felt safe, powerful, strong and/or grounded. Make the positive memory as real as possible.

- Implement cognitive strategies such as reframing the issue, sending goodwill to the person, seeing the problem from the other person’s point of view, and ask is this problem worth dying over (Peper, Harvey, & Hamiel, 2019).

What to Do When Thoughts Keep Interrupting

Practice humming or toning. When you are humming or toning, your focus is on making the sound and the thoughts tend to stop. Generally, breathing will slow down to about six breaths per minute (Peper, Pollack et al., 2019). Explore the following:

- Box breathing (Röttger et al., 2021; Balban et al., 2023)

- Humming also known as bee breath (Bhramari Pranayama) (Abishek et al., 2019; Yoga, 2023) – Allow the tongue to rest against the upper palate, sit tall and erect so that the back of the head is reaching upward to the ceiling, and inhale through your nose as the abdomen expands. Then begin humming while the air flows out through your nose, feel the vibration in the nose, face and throat. Let humming last for about 7 seconds and then allow the air to blow in through the nose and then hum again. Continue for about 5 minutes.

- Toning – Inhale through your nose and then vocalize a single sound such as Om. As you vocalize the lower sound, feel the vibration in your throat, chest and even going down to the abdomen. Let each toning exhalation last for about 6 to 7 seconds and then inhale through your nose. Continue for about 5 minutes (Peper, al., 2019).

Many people report that after practice these skills, they become aware that they are reacting and are able to reduce their automatic reaction. As a result, they experience a significant decrease in their stress levels, fewer symptoms such as neck and holder tension and high blood pressure, and they feel an increase in tranquility and the ability to communicate effectively.

Practicing these skills does not resolve the conflicts; they allow you to stop reacting automatically. This process allows you a time out and may give you the ability to be calmer, which allows you to think more clearly. When calmer, problem solving is usually more successful. As phrased in a popular meme, “You cannot see your reflection in boiling water. Similarly, you cannot see the truth in a state of anger. When the waters calm, clarity comes” (author unknown).

Boiling water (photo modified from: https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=388991500314839&set=a.377199901493999)

Below are additional resources that describe the practices. Please share these resources with friends, family and co-workers.

Stressor squat instructions

Toning instructions

Diaphragmatic breathing instructions

Reduce stress with posture and breathing

Conditioning

References

Abishek, K., Bakshi, S. S., & Bhavanani, A. B. (2019). The efficacy of yogic breathing exercise bhramari pranayama in relieving symptoms of chronic rhinosinusitis. International Journal of Yoga, 12(2), 120–123. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijoy.IJOY_32_18

Balban, M. Y., Neri, E., Kogon, M. M., Weed, L., Nouriani, B., Jo, B., Holl, G., Zeitzer, J. M., Spiegel, D., Huberman, A. D. (2023). Brief structured respiration practices enhance mood and reduce physiological arousal. Cell Reports Medicine, 4(1), 10089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100895

Basso, J. C. & Suzuki, W. A. (2017). The effects of acute exercise on mood, cognition, neurophysiology, and neurochemical pathways: A review. Brain Plast, 2(2), 127–152. https://doi.org/10.3233/BPL-160040

Bernard, C. (1872). De la physiologie générale. Paris: Hachette livre. https://www.amazon.ca/PHYSIOLOGIE-GENERALE-BERNARD-C/dp/2012178596

Cannon, W. B. (1929). Organization for Physiological Homeostasis. Physiological Reviews, 9, 399–431. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.1929.9.3.399

Cohen, L. & Lansing, A. H. (2021). The tend and befriend theory of stress: Understanding the biological, evolutionary, and psychosocial aspects of the female stress response. In: Hazlett-Stevens, H. (eds), Biopsychosocial Factors of Stress, and Mindfulness for Stress Reduction. pp. 67–81, Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81245-4_3

Gevirtz, R. (2014). HRV Training and its Importance – Richard Gevirtz, Ph.D., Pioneer in HRV Research & Training. Thought Technology. Accessed December 29, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9nwFUKuJSE0

Green, E. E., Green, A. M., & Walters, E. D. (1970). Voluntary control of internal states: Psychological and physiological. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 2, 1–26. https://atpweb.org/jtparchive/trps-02-70-01-001.pdf

Hilt, L. M., & Pollak, S. D. (2012). Getting out of rumination: comparison of three brief interventions in a sample of youth. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40(7), 1157–1165.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-012-9638-3

Lally, P., VanJaarsveld, C. H., Potts, H. W., & Wardle, J. (2010). How habits are formed: Modelling habit formation the real world. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 998–1009. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.674

Liao, Y., Shonkoff, E. T., & Dunton, G. F. (2015). The acute relationships between affect, physical feeling states, and physical activity in daily life: A review of current evidence. Frontiers in Psychology. 6, 1975. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01975

McEwen, B. S. (1998). Stress, adaptation, and disease: Allostasis and allostatic load. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 840(1), 33–44.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09546.x

Oded, Y. (2018). Integrating mindfulness and biofeedback in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Biofeedback, 46(2), 37-47. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-46.02.03

Oded, Y. (2023). Personal communication. S.O.S 1™ technique is part of the Sense Of Safety™ method. www.senseofsafety.co

Peper, E. (2021). Relive memory to create healing imagery. Somatics, XVIII(4), 32–35.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/369114535_Relive_memory_to_create_healing_imagery

Peper, E., Gibney, K.H. & Holt. C. (2002). Make Health Happen: Training Yourself to Create Wellness. Dubuque, IA: Kendall-Hunt. https://he.kendallhunt.com/product/make-health-happen-training-yourself-create-wellness

Peper, E., & Gibney, K.H. (2003). A teaching strategy for successful hand warming. Somatics. XIV(1), 26–30. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/376954376_A_teaching_strategy_for_successful_hand_warming

Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Faass, N. (2020). TechStress: How Technology is Hijacking Our Lives, Strategies for Coping, and Pragmatic Ergonomics. North Atlantic Books. https://www.amazon.com/Beyond-Ergonomics-Prevent-Fatigue-Burnout/dp/158394768X

Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Hamiel, D. (2019). Transforming thoughts with postural awareness to increase therapeutic and teaching efficacy. NeuroRegulation, 6(3),153–160. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.6.3.153

Peper, E., Lee, S., Harvey, R., & Lin, I-M. (2016). Breathing and math performance: Implication for performance and neurotherapy. NeuroRegulation, 3(4), 142–149. http://dx.doi.org/10.15540/nr.3.4.142

Peper, E., Lin, I-M, Harvey, R., & Perez, J. (2017). How posture affects memory recall and mood. Biofeedback, 45(2), 36–41. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-45.2.01

Peper, E., Pollack, W., Harvey, R., Yoshino, A., Daubenmier, J. & Anziani, M. (2019). Which quiets the mind more quickly and increases HRV: Toning or mindfulness? NeuroRegulation, 6(3), 128–133. https://www.neuroregulation.org/article/view/19345/13263

Peper, E. & Wilson, V. (2021). Optimize the learning state: Techniques and habits. Biofeedback, 9(2), 46–49. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-49-2-04

Porges, S. W. (1995). Orienting in a defensive world: Mammalian modifications of our evolutionary heritage. A polyvagal theory. Psychophysiology, 32(4), 301–318. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.1995.tb01213.x

Porges, S.W. (2021) Cardiac vagal tone: a neurophysiological mechanism that evolved in mammals to dampen threat reactions and promote sociality. World Psychiatry, 20(2),296-298. Porges SW. Cardiac vagal tone: a neurophysiological mechanism that evolved in mammals to dampen threat reactions and promote sociality. World Psychiatry. 2021 Jun;20(2):296-298. https://doi.org10.1002/wps.20871

Röttger, S., Theobald, D. A., Abendroth, J., & Jacobsen, T. (2021). The effectiveness of combat tactical breathing as compared with prolonged exhalation. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 46, 19–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-020-09485-w

Sapolsky, R. (2004). Why zebras don’t get ulcers (3rd ed.). New York:Holt. https://www.amazon.com/Why-Zebras-Dont-Ulcers-Third/dp/0805073698/

Schultz, J. H., & Luthe, W. (1959). Autogenic training: A psychophysiologic approach to psychotherapy. Grune & Stratton. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Autogenic_Training/y8SwQgAACAAJ?hl=en

Selye, H. (1951). The general-adaptation-syndrome. Annual Review of Medicine, 2(1), 327–342. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.me.02.020151.001551

Seo, H. (2023). How to stop ruminating. The New York Times. Accessed January 3, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/01/well/mind/stop-rumination-worry.html

Stroebel, C. F. (1985). QR: The Quieting Reflex. Berkley. https://www.amazon.com/Qr-quieting-reflex-Charles-Stroebel/dp/0425085066

Taylor, S. E., Klein, L. C., Lewis, B. P., Gruenewald, T. L., Gurung, R. A. R., & Updegraff, J. A. (2000). Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: Tend-and-befriend, not fight-or-flight. Psychological Review, 107(3), 411–429. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.107.3.411

Thayer, R. E. (2003). Calm energy: How people regulate mood with food and exercise. Oxford University Press. https://www.amazon.com/Calm-Energy-People-Regulate-Exercise/dp/0195163397

Xin, Q., Bai, B., & Liu, W. (2017). The analgesic effects of oxytocin in the peripheral and central nervous system. Neurochemistry International, 103, 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuint.2016.12.021

Yoga, N. (2023). This simple breath practice is scientifically proven to calm your mind. The nomadic yogi. Accessed December 31, 2023. https://www.leahsugerman.com/blog/bhramari-pranayama-humming-bee-breath#

Breathing to improve well-being

Posted: November 17, 2017 Filed under: Breathing/respiration, Exercise/movement, Neck and shoulder discomfort, Pain/discomfort, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: anxiety, Breathing, health, mindfulness, pain, respiration, stress 8 CommentsBreathing affects all aspects of your life. This invited keynote, Breathing and posture: Mind-body interventions to improve health, reduce pain and discomfort, was presented at the Caribbean Active Aging Congress, October 14, Oranjestad, Aruba. www.caacaruba.com

The presentation includes numerous practices that can be rapidly adapted into daily life to improve health and well-being.

Enhance Yoga with Biofeedback*

Posted: August 6, 2017 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: asana, awareness, biofeedback, Breathing, electromyography, meditation, posture, yoga Leave a commentHow can you demonstrate that yoga practices are beneficial?

How do you know you are tightening the correct muscles or relaxing the muscle not involved in the movement when practicing asanas?

How can you know that the person is mindful and not sleepy or worrying when meditating?

How do you know the breathing pattern is correct when practicing pranayama?

The obvious answer would be to ask the instructor or check in with the participant; however, it is often very challenging for the teacher or student to know. Many participants think that they are muscularly relaxed while in fact there is ongoing covert muscle tension as measured by electromyography (EMG). Some participants after performing an asana, do not relax their muscles even though they report feeling relaxed. Similarly, some people practice specific pranayama breathing practice with the purpose of restoring the sympathetic/parasympathetic system; however, they may not be doing it correctly. Similarly, when meditating, a person may become sleepy or their attention wanders and is captured by worries, dreams, and concerns instead of being present with the mantra. These problems may be resolved by integrating bio- and neurofeedback with yoga instruction and practice. Biofeedback monitors the physiological signals produced by the body and displays them back to the person as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Biofeedback is a methodology by which the participant receives ongoing feedback of the physiological changes that are occurring within the body. Reproduced with permission from Peper et al, 2008.

With the appropriate biofeedback equipment, one can easily record muscle tension, temperature, blood flow and pulse from the finger, heart rate, respiration, sweating response, posture alignment, etc.** Neurofeedback records the brainwaves (electroencephalography) and can selectively feedback certain EEG patterns. In most cases participants are unaware of subtle physiological changes that can occur. However, when the physiological signals are displayed so that the person can see or hear the changes in their physiology they learn internal awareness that is associated with these physiological changes and learn mastery and control. Biofeedback and neuro feedback is a tool to make the invisible, visible; the unfelt, felt and the undocumented, documented.

Biofeedback can be used to document that a purported yoga practice actually affects the psychophysiology. For example, in our research with the Japanese Yogi, Mr. Kawakami, who was bestowed the title “Yoga Samrat’ by the Indian Yoga Culture Federation in 1983, we measured his physiological responses while breathing at two breaths a minute as well as when he inserted non-sterilized skewers through his tongue tongue (Arambula et al, 2001; Peper et al, 2005a; Peper et al, 2005b). The physiological recordings confirmed that his Oxygen saturation stayed normal while breathing two breaths per minute and that he did not trigger any physiological arousal during the skewer piercing. The electroencephalographic recordings showed that there was no response or registration of pain. A useful approach of using biofeedback with yoga instruction is to monitor muscle activity to measure whether the person is performing the movement appropriately. Often the person tightens the wrong muscles or performs with too much effort, or does not relax after performing. An example of recording muscle tension as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Recording the muscle tension with Biograph Infinity while performing an asana.

In our research it is clear that many people are unaware that they tighten muscles. For example, Mcphetridge et al, (2011) showed that when participants were asked to bend forward slowly to touch their toes and then hang relaxed in a forward fold, most participants reported that they were totally relaxed in their neck. In actuality, they were not relaxed as their neck muscles were still contracting as recorded by electromyography (EMG). After muscle biofeedback training, they all learned to let their neck muscles be totally relaxed in the hanging fold position as shown in Figure 3 & 4.

Figure 3: Initial assessment of neck SEMG while performing a toe touch. Reproduced from Harvey, E. & Peper, E. (2011).

Figure 4: Toe touch after feedback training. The neck is now relaxed; however, the form is still not optimum. . Reproduced from Harvey, E. & Peper, E. (2011).

Thus, muscle feedback is a superb tool to integrate with teaching yoga so that participants can perform asanas with least amount of inappropriate tension and also can relax totally after having tightened the muscles. Biofeedback can similarly be used to monitor body posture during meditation. Often participants become sleepy or their attention drifts and gets captured by imagery or worries. When they become sleepy, they usually begin to slouch. This change in body position can be readily be monitored with a posture feedback device. The UpRight,™ (produced by Upright Technologies, Ltd https://www.uprightpose.com/) is a small sensor that is placed on the upper or lower spine and connects with Bluetooth to the cell phone. After calibration of erect and slouched positions, the device gives vibratory feedback each time the participant slouches and reminds the participant to come back to sitting upright as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5: UpRigh™ device placed on the upper spine to provide feedback during meditation. Each time person slouches which often occurs when they become sleepy or loose meditative focus, the device provides feedback by vibrating.

Alternatively, the brainwaves patterns (electroencephalography could be monitored with neurofeedback and whenever the person drifts into sleep or becomes excessively aroused by worry, neurofeedback could remind the person to be let go and be centered. Finally, biofeedback can be used with pranayama practice. When a person is breathing approximately six breaths per minute heart rate variability can increase. This means that during inhalation heart rate increases and during exhalation heart rate decreases. When the person breathes so that the heart rate variability increases, it optimizes sympathetic/parasympathetic activity. There are now many wearable biofeedback devices that can accurately monitor heart rate variability and display the changes in heart rate as modulated by breathing.

Conclusion: Biofeedback is a useful strategy to enhance yoga practice as it makes the invisible visible. It allows the teacher and the student to become aware of the dysfunctional patterns that may be occurring beneath awareness.

References

*Reprinted from: Peper, E. (2017). Enhancing Yoga with Biofeedback. J Yoga & Physio.2(2).*55584. DOI: 10.19080/JYP.2017.02.555584

**Biofeedback and neurofeedback takes skill and training. For information on certification, see http://www.bcia.org Two useful websites are:

Enjoy sex: Breathe away the pain*

Posted: March 19, 2017 Filed under: Breathing/respiration, Pain/discomfort, self-healing, Uncategorized | Tags: Breathing, dyspareunia, intercourse, intimacy, pain, pelvic floor, relaxation, Sexuality, vaginismus 7 CommentsAdapted from: Peper, E. & Cohen, T. (2017). Inhale to breathe away pelvic floor pain and enjoy intercourse. Biofeedback, 45(1), 21–24. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-45.1.04

“After two and a half years of trying, ups and downs, and a long period of thinking it will never happen, it did happen. I followed your advice by only applying pressure with the cones while inhaling and at the same time relaxing the pelvic floor. We succeeded! we had “real” sex in the first time.”

Millions of women experience involuntary contraction of the musculature of the outer third of the vagina (vaginismus) interfering with intercourse, causing distress and interpersonal difficulty (ter Kuile et, 2010) or pain during intercourse (dyspareunia). It is estimated that 1 to 6% of women have vaginismus (Lewis et al, 2004) and 6.5% to 45.0% in older women and from 14% to 34% in younger women experience dyspareunia (Van Lankveld et al, 2010; Gross & Brubaker, 2022). The most common treatment for vaginismus is sequential dilation of the vaginal opening with progressively larger cones, psychotherapy and medications to reduce the pain and anxiety. At times clients and health care professionals may be unaware of the biological processes that influence the muscle contraction and relaxation of the pelvic floor. Success is more likely if the client works in harmony with the biological processes while practicing self-healing and treatment protocols. These biological processes, described at the end of the blog significantly affects the opening of vestibule and vagina are: 1) feeling safe, 2) inhale during insertion to relax the pelvic floor, 3) stretch very, very slowly to avoid triggering the stretch reflex, and 4) being sexual aroused.

Successful case report: There is hope to resolve pain and vaginismus

Yesterday my husband and I had sex in the first time, after two and a half years of “trying”. Why did it take so long? Well, the doctor said “vaginismus”, the psychologist said “fear”, the physiotherapist said “constricted muscles”, and friends said “just relax, drink some wine and it will happen”.

Sex was always a weird, scary, complicated – and above all, painful – world to me. It may have started in high school: like many other teens, I thought a lot about sex and masturbated almost every night. Masturbation was a good feeling followed by tons of bad feelings – guilt, shame, and feeling disgusting. One of the ideas I had to accept, later in my progress, is that ‘feeling good is a good thing’. It is normal, permitted and even important and healthy.

My first experience, at age 20, was short, very painful, and without any love or even affection. He was…. well, not for me. And I was…. well, naive and with very little knowledge about my body. The experiences that came after that, with other guys, were frustrating. Neither of them knew how to handle the pain that sex caused me, and I didn’t know what to do.

The first gynecologist said that everything is fine and I just need to relax. No need to say I left her clinic very angry and in pain. The second gynecologist was the first one to give it a name: “vaginismus”. He said that there are some solutions to the problem: anesthetic ointment, physiotherapy (“which is rarely helps”, according to his optimistic view..), and if these won’t work “we will start thinking of surgery, which is very painful and you don’t want to go there”. Oh, I certainly didn’t want to go there.

After talking to a friend whose sister had the same problem, I started seeing a great physiotherapist who was an expert in these problems. She used a vaginal biofeedback sensor, that measured muscles’ tonus inside the vagina. My homework were 30 constrictions every day, plus working with “dilators” – plastic cones comes in 6 sizes, starting from a size of a small finger, to a size of a penis.

At this point I was already in a relationship with my husband, who was understanding, calm and most important – very patient. To be honest, we both never thought it would take so long. Practicing was annoying and painful, and I found myself thinking a lot “is it worth it?”. After a while, I felt that the physical practice is not enough, and I need a “psychological breakthrough”. So I stopped practicing and started seeing a psychologist, for about a half a year. We processed my past experiences, examined the thoughts and beliefs I had about sex, and that way we released some of the tension that was shrinking my body.

The next step was to continue practicing with the dilators, but honestly – I had no motivation. My husband and I had great sex without the actual penetration, and I didn’t want the painful practice again. Fortunately, I participated in a short course given by Professor Erik Peper, about biofeedback therapy. In his lecture he described a young woman, who suffered from vulvodynia, a problem that is a bit similar to vaginismus (Peper et al, 2015; See: https://peperperspective.com/2015/09/25/resolving-pelvic-floor-pain-a-case-report/). She learned how to relax her body and deal with the pain, and finally she had sex – and even enjoyed it! I was inspired.

Erik Peper gave me a very important advice: breathing in. Apparently, we can relax the muscles and open the vagina better while inhaling, instead of exhaling – as I tried before. During exhalation the pelvic floor tightens and goes upward while during inhalation the pelvic floor descends and relaxes especially when sitting up (Peper et al, 2016). He advised me to give myself a few minutes with the dilator, and in every inhale – imagine the area opening and insert the dilator a few millimeters. I started practicing again, but in a sitting position, which I found more comfortable and less painful. I advanced to the biggest dilator within a few weeks, and had a just little pain – sometimes without any pain at all. The most important thing I understood was not to be afraid of the pain. The fear is what made me even more tensed, and tension brings pain. Then, my husband and I started practicing with “the real thing”, very slowly and gently, trying to find the best position and angle for us. Finally, we did it. And it was a great feeling.

The biological factors that affect the relaxation/contraction of the pelvic floor and vaginal opening are:

Feeling safe and hopeful. When threatened, scared, anticipate pain, and worry, our body triggers a defense reaction. In this flexor response, labeled by Thomas Hanna as the Red Light Reflex, the body curls up in defense to protect itself which includes the shoulders to round, the chest to be depressed, the legs pressing together, the pelvic floor to tighten and the head to jut forward (Hanna, 2004). This is the natural response of fear, anxiety, prolonged stress or negative depressive thinking.

Before beginning to work on vaginismus, feel safe. This means accepting what is, accepting that it is not your fault, and that there are no demands for performance. It also means not anticipating that it will be again painful because with each anticipation the pelvic floor tends to tightens. Read the chapter on vaginismus in Dr. Lonnie Barbach’s book, For each other: Sharing sexual intimacy (Barbach, 1983).

Inhale during insertion to relax the pelvic floor and vaginal opening. This instruction is seldom taught because in most instances, we have been taught to exhale while relaxing. Exhaling while relaxing is true for most muscles; however, it is different for the pelvic floor. When inhalation occurs, the pelvic floor descends and relaxes. During exhalation the pelvic floor tightens and ascends to support breathing and push the diaphragm upward to exhale the air. Be sure to allow the abdomen to expand during inhalation without lifting the chest and allow the abdomen to constrict during exhalation as if inhalation fills the balloon in the abdomen and exhalation deflates the balloon (for detailed instructions see Peper et al, 2016). Do not inhale by lifting and expanding your chest which often occurs during gasping and and fear. It tends to tighten and lift the pelvic floor.

Experience the connection between diaphragmatic breathing and pelvic floor movement in the following practice.

While sitting upright make a hissing noise as the air escapes with pressure between your lips. As you are exhaling feel, your abdomen and your anus tightening. During the inhalation let your abdomen expand and feel how your anus descends and pelvic floor relaxes. With practice this will become easier.

Stretch very, very slowly to avoid triggering the stretch reflex. When a muscle is rapidly stretched, it triggers an automatic stretch reflex which causes the muscle to contract. This innate response occurs to avoid damaging the muscle by over stretching. The stretch reflex is also triggered by pain and puts a brake on the stretching. Always use a lubricant when practicing by yourself or with a partner. Practice inserting larger and larger diameter dilaters into the vagina. Start with a very small diameter and progress to a larger diameter. These can be different diameter cones, your finger, or other objects. Remember to inhale and feel the pelvic floor descending as you insert the probe or finger. If you feel discomfort/pain, stop pushing, keep breathing, relax your shoulders, relax your hips, legs, and toes and do not push inward and upward again until the discomfort has faded out.

Feel sexually aroused by allowing enough foreplay. When sexually aroused the tissue is more lubricated and may stretch easier. Continue to use a good lubricant.

Putting it all together.

When you feel safe, practice slow diaphragmatic breathing and be aware of the pelvic floor relaxing and descending during inhalation and contracting and going up during exhalation. When practicing stretching the opening with cones or your finger, go very, very slow. Only apply pressure of insertion during the mid-phase of inhalation, then wait during exhalation and then again insert slight more during the next inhalation. When you experience pain, relax your shoulders, keep breathing for four or five breaths till the pain subsides, then push very little during the next inhalation. Go much slower and with more tenderness.

Be patient. Explain to your partner that your body and mind need time to adjust to new feelings. However, don’t stop having sex – you can have great sex without penetration. Practice both alone and with your partner; together find the best angle and rate. Use different lubricants to check out what is best for you. Any little progress is getting you closer to having an enjoyable sex. I recommend watching this TED video of Emily Nagoski explaining the “dual control model” and practicing as she suggests: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HILY0wWBlBM

Finally, practice the exercises developed by Dr. Lonnie Barbach, who as one of the first co-directors of clinical training at the University of California San Francisco, Human Sexuality Program, created the women’s pre-orgasmic group treatment program. They are superbly described in her two books, For each other: Sharing sexual intimacy, and For yourself: The fulfillment of female sexuality, and are a must read for anyone desiring to increase sexual fulfillment and joy (Barbach, 2000; 1983).

References:

Barbach, L. (1983). For each other: Sharing sexual intimacy. New York: Anchor

Barbach, L. (2000). For yourself: The fulfillment of female sexuality. New York: Berkley.

BarLewis, R. W., Fugl‐Meyer, K. S., Bosch, R., Fugl‐Meyer, A. R., Laumann, E. O., Lizza, E., & Martin‐Morales, A. (2004). Epidemiology/risk factors of sexual dysfunction. The journal of sexual medicine, 1(1), 35-39. http://www.jsm.jsexmed.org/article/S1743-6095(15)30062-X/fulltext

Gross. E. & Brubaker, L. (2022). Dyspareunia in Women. JAMA. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.4853

Hanna, T. (2004). Somatics: Reawakening the mind’s control of movement, flexibility, and health. Boston: Da Capo Press.

Martinez Aranda, P. & Peper, E. (2015). The healing of vulvodynia from a client’s perspective. https://biofeedbackhealth.files.wordpress.com/2011/01/a-healing-of-vulvodynia-from-the-client-perspective-2015-06-15.pdf

Peper, E., Booiman, A., Lin, I-M, Harvey, R., & Mitose, J. (2016). Abdominal SEMG Feedback for Diaphragmatic Breathing: A Methodological Note. Biofeedback. 44(1), 42-49. https://biofeedbackhealth.files.wordpress.com/2011/01/1-abdominal-semg-feedback-published.pdf

Peper, E., Martinez Aranda, P., & Moss, E. (2015). Vulvodynia treated successfully with breathing biofeedback and integrated stress reduction: A case report. Biofeedback. 43(2), 103-109. https://biofeedbackhealth.files.wordpress.com/2011/01/a-vulvodynia-treated-with-biofeedback-published.pdf

Ter Kuile, M. M., Both, S., & van Lankveld, J. J. (2010). Cognitive behavioral therapy for sexual dysfunctions in women. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 33(3), 595-610. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/45090259_Cognitive_Behavioral_Therapy_for_Sexual_Dysfunctions_in_Women

Van Lankveld, J. J., Granot, M., Weijmar Schultz, W., Binik, Y. M., Wesselmann, U., Pukall, C. F., . Achtrari, C. (2010). Women’s sexual pain disorders. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7(1pt2), 615-631. http://www.jsm.jsexmed.org/article/S1743-6095(15)32867-8/fulltext

*We thank Dr. Lonnie Barbach for her helpful feedback and support. Written collaboratively with Tal Cohen, biofeedback therapist (Israel) and Erik Peper.

Can abdominal surgery cause epilepsy, panic and anxiety and be reversed with breathing biofeedback?*

Posted: March 5, 2016 Filed under: Breathing/respiration, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: anxiety, biofeedback, Breathing, epilepsy, iatrogenic illness, learned disuse, panic, respiration, surgery 3 Comments“I had colon surgery six months ago. Although I made no connection to my anxiety, it just started to increase and I became fearful and I could not breathe. The asthma medication did not help. Learning effortless diaphragmatic breathing and learning to expand my abdomen during inhalation allowed me to breathe comfortably without panic and anxiety—I could breathe again.” (72 year old woman)

“One year after my appendectomy, I started to have twelve seizures a day. After practicing effortless diaphragmatic breathing and changing my lifestyle, I am now seizure-free.” (24 year old male college student)

One of the hidden long term costs of surgery and injury is covert learned disuse. Learned disuse occurs when a person inhibits using a part of their body to avoid pain and compensates by using other muscle patterns to perform the movements (Taub et al, 2006). This compensation to avoid discomfort creates a new habit pattern. However, the new habit pattern often induces functional impairment and creates the stage for future problems.

Many people have experienced changing their gait while walking after severely twisting their ankle or breaking their leg. While walking, the person will automatically compensate and avoid putting weight on the foot of the injured leg or ankle. These compensations may even leads to shoulder stiffness and pain in the opposite shoulder from the injured leg. Even after the injury has healed, the person may continue to move in the newly learned compensated gait pattern. In most cases, the person is totally unaware that his/her gait has changed. These new patterns may place extra strain on the hip and back and could become a hidden factor in developing hip pain and other chronic symptoms.

Similarly, some women who have given birth develop urinary stress incontinence when older. This occurred because they unknowingly avoided tightening their pelvic floor muscles after delivery because it hurt to tighten the stretched or torn tissue. Even after the tissue was healed, the women may no longer use their pelvic floor muscles appropriately. With the use of pelvic floor muscle biofeedback, many women with stress incontinence can rapidly learn to become aware of the inhibited/forgotten muscle patterns (learned disuse) and regain functional control in nine sessions of training (Burgio et al., 1998; Dannecker et al., 2005). The process of learned disuse is the result of single trial learning to avoid pain. Many of us as children have experienced this process when we touched a hot stove—afterwards we tended to avoid touching the stove even when it was cold.

Often injury will resolve/cure the specific problem. It may not undo the covert newly learned dysfunctional patterns which could contribute to future iatrogenic problems or illnesses (treatment induced illness). These iatrogenic illnesses are treated as a new illness without recognizing that they were the result of functional adaptations to avoid pain and discomfort in the recovery phase of the initial illness.

Surgery creates instability at the incision site and neighboring areas, so our bodies look for the path of least resistance and the best place to stabilize to avoid pain. (Adapted from Evan Osar, DC).

After successful surgical recovery do not assume you are healed!

Yes, you may be cured of the specific illness or injury; however, the seeds for future illness may be sown. Be sure that after injury or surgery, especially if it includes pain, you learn to inhibit the dysfunctional patterns and re-establish the functional patterns once you have recovered from the acute illness. This process is described in the two cases studies in which abdominal surgeries appeared to contribute to the development of anxiety and uncontrolled epilepsy.

How abdominal surgery can have serious, long-term effect on changing breathing patterns and contributing to the development of chronic illness.

When recovering from surgery or injury to the abdomen, it is instinctual for people to protect themselves and reduce pain by reducing the movement around the incision. They tend to breathe more shallowly as not to create discomfort or disrupt the healing process (e.g., open a stitch or staple. Prolonged shallow breathing over the long term may result in people experiencing hyperventilation induced panic symptoms or worse. This process is described in detail in our recent article, Did You Ask about Abdominal Surgery or Injury? A Learned Disuse Risk Factor for Breathing Dysfunction (Peper et al., 2015). The article describes two cases studies in which abdominal surgeries led to breathing dysfunction and ultimately chronic, serious illnesses.

Reducing epileptic seizures from 12 per week to 0 and reducing panic and anxiety

A routine appendectomy caused a 24-year-old male to develop rapid, shallow breathing that initiated a series of up to 12 seizures per week beginning a year after surgery. After four sessions of breathing retraining and incorporating lifestyle changes over a period of three months his uncontrolled seizures decreased to zero and is now seizure free. In the second example, a 39-year-old woman developed anxiety, insomnia, and panic attacks after her second kidney transplant probably due to shallow rapid breathing only in her chest. With biofeedback, she learned to change her breathing patterns from 25 breaths per minute without any abdominal movement to 8 breathes a minute with significant abdominal movement. Through generalization of the learned breathing skills, she was able to achieve control in situations where she normally felt out of control. As she practiced this skill her symptoms were significantly reduced and stated:

“What makes biofeedback so terrific in day-to-day situations is that I can do it at any time as long as I can concentrate. When I feel I can’t concentrate, I focus on counting and working with my diaphragm muscles; then my concentration returns. Because of the repetitive nature of biofeedback, my diaphragm muscles swing into action as soon as I started counting. When I first started, I had to focus on those muscles to get them to react. Getting in the car, I find myself starting these techniques almost immediately. Biofeedback training is wonderful because you learn techniques that can make challenging situations more manageable. For me, the best approach to any situation is to be calm and have peace of mind. I now have one more way to help me achieve this.” (From: Peper et al, 2001).

The commonality between these two participants was that neither realized that they were bracing the abdomen and were breathing rapidly and shallowly in the chest. I highly recommend that anyone who has experienced abdominal insults or surgery observe their breathing patterns and relearn effortless breathing/diaphragmatically breathing instead of shallow, rapid chest breathing often punctuated with breath holding and sighs.

It is important that medical practitioners and post-operative surgery patients recognize the common covert learned disuse patters such as shifting to shallow breathing to avoid pain. The sooner these patterns are identified and unlearned, the less likely will the person develop future iatrogenic illnesses. Biofeedback is an excellent tool to help identify and retrain these patterns and teach patients how to reestablish healthy/natural body patterns.

The full text of the article see: “Did You Ask About Abdominal Surgery or Injury? A Learned Disuse Risk Factor for Breathing Dysfunction,”

*Adapted from: Biofeedback Helps to Control Breathing Dysfunction.http://www.prweb.com/releases/2016/02/prweb13211732.htm

References

Burgio, K. L., Locher, J. L., Goode, P. S., Hardin, J. M., McDowell, B. J., Dombrowski, M., & Candib, D. (1998). Behavioral vs drug treatment for urge urinary incontinence in older women: a randomized controlled trial. Jama, 280(23), 1995-2000.

Dannecker, C., Wolf, V., Raab, R., Hepp, H., & Anthuber, C. (2005). EMG-biofeedback assisted pelvic floor muscle training is an effective therapy of stress urinary or mixed incontinence: a 7-year experience with 390 patients. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 273(2), 93-97.

Osar, E. (2016). http://www.fitnesseducationseminars.com/

Peper, E., Castillo, J., & Gibney, K. H. (2001, September). Breathing biofeedback to reduce side effects after a kidney transplant. In Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback (Vol. 26, No. 3, pp. 241-241). 233 Spring St., New York, NY 10013 USA: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publ.

Peper, E., Gilbert, C.D., Harvey, R. & Lin, I-M. (2015). Did you ask about abdominal surgery or injury? A learned disuse risk factor for breathing dysfunction. Biofeedback. 34(4), 173-179. DOI: 10.5298/1081-5937-43.4.06

Taub, E., Uswatte, G., Mark, V. W., Morris, D. M. (2006). The learned nonuse phenomenon: Implications for rehabilitation. Europa Medicophysica, 42(3), 241-256.

Resolving pelvic floor pain-A case report

Posted: September 25, 2015 Filed under: Breathing/respiration, Pain/discomfort, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: biofeedback, Breathing, electromyography, pain, posture, self-regulation, vulvodynia 7 CommentsAdapted from: Martinez Aranda, P. & Peper, E. (2015). The healing of vulvodynia from a client’s perspective. https://biofeedbackhealth.files.wordpress.com/2011/01/a-healing-of-vulvodynia-from-the-client-perspective-2015-06-15.pdf

It’s been a little over a year since I began practicing biofeedback and visualization strategies to overcome vulvodynia. Today, I feel whole, healed, and hopeful. I learned that through controlled and conscious breathing, I could unleash the potential to heal myself from chronic pain. Overcoming pain did not happen overnight; but rather, it was a process where I had to create and maintain healthy lifestyle habits and meditation. Not only am I thankful for having learned strategies to overcome chronic pain, but for acquiring skills that will improve my health for the rest of my life. –-24 year old woman who successfully resolved vulvodynia

Pelvic floor pain can be debilitating, and it is surprisingly common, affecting 10 to 25% of American women. Pelvic floor pain has numerous causes and names. It can be labeled as vulvar vestibulitis, an inflammation of vulvar tissue, interstitial cystitis (chronic pain or tenderness in the bladder), or even lingering or episodic hip, back, or abdominal pain. Chronic pain concentrated at the entrance to the vagina (vulva), is known as vulvodynia. It is commonly under-diagnosed, often inadequately treated, and can go on for months and years (Reed et al., 2007; Mayo Clinic, 2014). The discomfort can be so severe that sitting is uncomfortable and intercourse is impossible because of the extreme pain. The pain can be overwhelming and destructive of the patient’s life. As the participant reported,

I visited a vulvar specialist and he gave me drugs, which did not ease the discomfort. He mentioned surgical removal of the affected tissue as the most effective cure (vestibulectomy). I cried immediately upon leaving the physician’s office. Even though he is an expert on the subject, I felt like I had no psychological support. I was on Gabapentin to reduce pain, and it made me very depressed. I thought to myself: Is my life, as I know it, over?

Physically, I was in pain every single day. Sometimes it was a raging burning sensation, while other times it was more of an uncomfortable sensation. I could not wear my skinny jeans anymore or ride a bike. I became very depressed. I cried most days because I felt old and hopeless instead of feeling like a vibrant 23-year-old woman. The physical pain, combined with my negative feelings, affected my relationship with my boyfriend. We were unable to have sex at all, and because of my depressed status, we could not engage in any kind of fun. (For more details, read the published case report,Vulvodynia treated successfully with breathing biofeedback and integrated stress reduction: A case report).

The four-session holistic biofeedback interventions to successfully resolved vulvodynia included teaching diaphragmatic breathing to transform shallow thoracic breathing into slower diaphragmatic breathing, transforming feelings of powerlessness and hopelessness to empowerment and transforming her beliefs that she could reduce her symptoms and optimize her health. The interventions also incorporated self-healing imagery and posture-changing exercises. The posture changes consisted of developing awareness of the onset of moving into a collapsed posture and use this awareness to shift to an erect/empowered postures (Carney, Cuddy, & Yap, 2010; Peper, 2014; Peper, Booiman, Lin, & Harvey, in press). Finally, this case report build upon the seminal of electromyographic feedback protocol developed by Dr. Howard Glazer (Glazer & Hacad, 2015) and the integrated relaxation protocol developed Dr. David Wise (Wise & Anderson, 2007).

Through initial biofeedback monitoring of the lower abdominal muscle activity, chest, and abdomen breathing patterns, the participant observed that when she felt discomfort or was fearful, her lower abdomen muscles tended to tighten. After learning how to sense this tightness, she was able to remind herself to breathe lower and slower, relax the abdominal wall during inhalation and sit or stand in an erect power posture.

The self-mastery approach for healing is based upon a functional as compared to a structural perspective. The structural perspective implies that the problem can only be fixed by changing the physical structure such as with surgery or medications. The functional perspective assumes that if you can learn to change your dysfunctional psychophysiological patterns the disorder may disappear.

The functional approach assumed that an irritation of the vestibular area might have caused the participant to tighten her lower abdomen and pelvic floor muscles reflexively in a covert defense reaction. In addition, ongoing worry and catastrophic thinking (“I must have surgery, it will never go away, I can never have sex again, my boyfriend will leave me”) also triggered the defense reaction—further tightening of her lower abdomen and pelvic area, shallow breathing, and concurrent increases in sympathetic nervous activation—which together activated the trigger points that lead to increased chronic pain (Banks et al, 1998).

When the participant experienced a sensation or thought/worried about the pain, her body responded in a defense reaction by breathing in her chest and tightening the lower abdominal area as monitored with biofeedback. Anticipation of being monitored increased her shoulder tension, recalling the stressful memory increased lower abdominal muscle tension (pulling in the abdomen for protection), and the breathing became shallow and rapid as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Physiological recording of pre-stressor relaxation, the recall of a fearful driving experience, and a post-stressor relaxation. The scalene to trapezius SEMG increased in anticipation while she recalled the experience, and then initially did not relax (from Peper, Martinez Aranda, & Moss, 2015).

This defense pattern became a conditioned response—initiating intercourse or being touched in the affected area caused the participant to tense and freeze up. She was unaware of these automatic protective patterns, which only worsened her chronic pain.

During the four sessions of training, the participant learned to reverse and interrupt the habitual defense reaction. For example, as she became aware of her breathing patterns she reported,

It was amazing to see on the computer screen the difference between my regular breathing pattern and my diaphragmatic breathing pattern. I could not believe I had been breathing that horribly my whole life, or at least, for who knows how long. My first instinct was to feel sorry for myself. Then, rather than practicing negative patterns and thoughts, I felt happy because I was learning how to breathe properly. My pain decreased from an 8 to alternating between a 0 and 3.

The mastery of slower and lower abdominal breathing within a holistic perspective resulted in the successful resolution of her vulvodynia. An essential component of the training included allowing the participant to feel safe, and creating hope by enabling her to experience a decrease in discomfort while doing a specific practice, and assisting her to master skills to promote self-healing. Instead of feeling powerless and believing that the only resolution was the removal of the affected area (vestibulectomy). The integrated biofeedback protocol offered skill mastery training, to promote self-healing through diaphragmatic breathing, somatic postural changes, reframing internal language, and healing imagery as part of a common sense holistic health approach.

For more details about the case report, download the published study, Peper, E., Martinez Aranda, P., & Moss, E. (2015). Vulvodynia treated successfully with breathing biofeedback and integrated stress reduction: A case report. Biofeedback. 43(2), 103-109.

The participant also wrote up her subjective experience of the integrated biofeedback process in the paper, Martinez Aranda & Peper (2015). Healing of vulvodynia from the client perspective. In this paper she articulated her understanding and experiences in resolving vulvodynia which sheds light on the internal processes that are so often skipped over in published reports.

At the five year follow-up on May 29, 2019, she wrote:

“I am doing very well, and I am very healthy. The vulvodynia symptoms have never come back. It migrated to my stomach a couple of years after, and I still have a sensitive stomach. My stomach has gotten much, much better, though. I don’t really have random pain anymore, now I just have to be watchful and careful of my diet and my exercise, which are all great things!”

References

Banks, S. L., Jacobs, D. W., Gevirtz, R., & Hubbard, D. R. (1998). Effects of autogenic relaxation training on electromyographic activity in active myofascial trigger points. Journal of Musculoskeletal Pain, 6(4), 23-32. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/David_Hubbard/publication/232035243_Effects_of_Autogenic_Relaxation_Training_on_Electromyographic_Activity_in_Active_Myofascial_Trigger_Points/links/5434864a0cf2dc341daf4377.pdf

Carney, D. R., Cuddy, A. J., & Yap, A. J. (2010). Power posing brief nonverbal displays affect neuroendocrine levels and risk tolerance. Psychological Science, 21(10), 1363-1368. Available from: https://www0.gsb.columbia.edu/mygsb/faculty/research/pubfiles/4679/power.poses_.PS_.2010.pdf

Glazer, H. & Hacad, C.R. (2015). The Glazer Protocol: Evidence-Based Medicine Pelvic Floor Muscle (PFM) Surface Electromyography (SEMG). Biofeedback, 40(2), 75-79. http://www.aapb-biofeedback.com/doi/abs/10.5298/1081-5937-40.2.4

Martinez Aranda, P. & Peper, E. (2015). Healing of vulvodynia from the client perspective. Available from: https://biofeedbackhealth.files.wordpress.com/2011/01/a-healing-of-vulvodynia-from-the-client-perspective-2015-06-15.pdf

Mayo Clinic (2014). Diseases and conditions: Vulvodynia. Available at http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/vulvodynia/basics/definition/con-20020326

Peper, E. (2014). Increasing strength and mood by changing posture and sitting habits. Western Edition, pp.10, 12. Available from: http://thewesternedition.com/admin/files/magazines/WE-July-2014.pdf

Peper, E., Booiman, A., Lin, I, M.,& Harvey, R. (in press). Increase strength and mood with posture. Biofeedback.

Peper, E., Martinez Aranda, P., & Moss, E. (2015). Vulvodynia treated successfully with breathing biofeedback and integrated stress reduction: A case report. Biofeedback. 43(2), 103-109. Available from: https://biofeedbackhealth.files.wordpress.com/2011/01/a-vulvodynia-treated-with-biofeedback-published.pdf

Reed, B. D., Haefner, H. K., Sen, A., & Gorenflo, D. W. (2008). Vulvodynia incidence and remission rates among adult women: a 2-year follow-up study. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 112(2, Part 1), 231-237. http://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/Abstract/2008/08000/Vulvodynia_Incidence_and_Remission_Rates_Among.6.aspx

Wise, D., & Anderson, R. U. (2006). A headache in the pelvis: A new understanding and treatment for prostatitis and chronic pelvic pain syndromes. Occidental, CA: National Center for Pelvic Pain Research.http://www.pelvicpainhelp.com/books/

Reduce hot flashes and premenstrual symptoms with breathing

Posted: February 18, 2015 Filed under: Breathing/respiration, Pain/discomfort, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: biofeedback, Breathing, diaphragmatic breathing, heart rate variability, hormone replacement therapy, hot flashes, HRT, Menopause, respiration, sighs, stress, sympathetic activity 6 CommentsAfter the first week to my astonishment, I have fewer hot flashes and they bother me less. Each time I feel the warmth coming, I breathe out slowly and gently. To my surprise they are less intense and are much less frequent. I keep breathing slowly throughout the day. This is quite a surprise because I was referred for biofeedback training because of headaches that occurred after getting a large electrical shock. After 5 sessions my headaches have decreased and I can control them, and my hot flashes have decreased from 3-4 per day to 1-2 per week. -50 year old client

After students in my Holistic Health class at San Francisco State University practiced slower diaphragmatic breathing and begun to change their dysfunctional shallow breathing, gasping, sighing, and breath holding to diaphragmatic breathing. A number of the older female students students reported that their hot flashes decreased. Some of the younger female students reported that their menstrual cramps and discomfort were reduced by 80 to 90% when they laid down and breathed slower and lower into their abdomen.

The recent study in JAMA reported that many women continue to experience menopausal triggered hot flashes for up to 14 years. Although the article described the frequency and possible factors that were associated with the prolonged hot flashes, it did not offer helpful solutions.

The recent study in JAMA reported that many women continue to experience menopausal triggered hot flashes for up to 14 years. Although the article described the frequency and possible factors that were associated with the prolonged hot flashes, it did not offer helpful solutions.

Another understanding of the dynamics of hot flashes is that the decrease in estrogen accentuates the sympathetic/ parasympathetic imbalances that probably already existed. Then any increase in sympathetic activation can trigger a hot flash. In many cases the triggers are events and thoughts that trigger a stress response, emotional responses such as anger, anxiety, or worry, increase caffeine intake and especially shallow chest breathing punctuated with sighs. Approximately 80% of American women tend to breathe thoracically often punctuated with sighs and these women are more likely to experience hot flashes. On the other hand, the 20% of women who habitually breathe diaphragmatically tend to have fewer and less intense hot flashes and often go through menopause without any discomfort. In the superb study Drs. Freedman and Woodward (1992), taught women who experience hot flashes to breathe slowly and diaphragmatically which increased their heart rate variability as an indicator of sympathetic/parasympathetic balance and most importantly it reduced the the frequency and intensity of hot flashes by 50%.

Test the breathing connection if you experience hot flashes

Take a breath into your chest and rapidly exhale with a sigh. Repeat this quickly five times. In most cases, one minute later you will experience the beginning sensations of a hot flash. Similarly, when you practice slow diaphragmatic breathing throughout the day and interrupt every gasp, breath holding moment, sigh or shallow chest breathing with slower diaphragmatic breathing, you will experience a significant reduction in hot flashes.

Although this breathing approach has been well documented, many people are unaware of this simple behavioral approach unlike the common recommendation for the hormone replacement therapies (HRT) to ameliorate menopausal symptoms. This is not surprising since pharmaceutical companies spent nearly five billion dollars per year in direct to consumer advertising for drugs and very little money is spent on advertising behavioral treatments. There is no profit for pharmaceutical companies teaching effortless diaphragmatic breathing unlike prescribing HRTs. In addition, teaching and practicing diaphragmatic breathing takes skill training and practice time–time which is not reimbursable by third party payers.

For more information, research data and breathing skills to reduce hot flash intensity, see our article which is reprinted below.

Gibney, H.K. & Peper, E. (2003). Taking control: Strategies to reduce hot flashes and premenstrual mood swings. Biofeedback, 31(3), 20-24.

Taking control: Strategies to reduce hot flashes and premenstrual mood swings*

Erik Peper, Ph.D**., and Katherine H. Gibney

San Francisco State University

After the first week to my astonishment, I have fewer hot flashes and they bother me less. Each time I feel the warmth coming, I breathe out slowly and gently. To my surprise they are less intense and are much less frequent. I keep breathing slowly throughout the day. This is quite a surprise because I was referred for biofeedback training because of headaches that occurred after getting a large electrical shock. After 5 sessions my headaches have decreased and I can control them, and my hot flashes have decreased from 3-4 per day to 1-2 per week. -50 year old client

For the first time in years, I experienced control over my premenstrual mood swings. Each time I could feel myself reacting, I relaxed, did my autogenic training and breathing. I exhaled. It brought me back to center and calmness. -26 year old student

Abstract

Women have been troubled by hot flashes and premenstrual syndrome for ages. Hormone replacement therapy, historically the most common treatment for hot flashes, and other pharmacological approaches for pre-menstrual syndrome (PMS) appear now to be harmful and may not produce significant benefits. This paper reports on a model treatment approach based upon the early research of Freedman & Woodward to reduce hot flashes and PMS using biofeedback training of diaphragmatic breathing, relaxation, and respiratory sinus arrhythmia. Successful symptom reduction is contingent upon lowering sympathetic arousal utilizing slow breathing in response to stressors and somatic changes. We strongly recommend that effortless diaphragmatic breathing be taught as the first step to reduce hot flashes and PMS symptoms.

A long and uncomfortable history

Women have been troubled by hot flashes and premenstrual syndrome for ages. Hot flashes often result in red faces, sweating bodies, and noticeable and embarrassing discomfort. They come in the middle of meetings, in the middle of the night, and in the middle of romantic interludes. Premenstrual syndrome also arrives without notice, bringing such symptoms as severe mood swings, anger, crying, and depression.

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) was the most common treatment for hot flashes for decades. However, recent randomized controlled trials show that the benefits of HRT are less than previously thought and the risks—especially of invasive breast cancer, coronary artery disease, dementia, stroke and venous thromboembolism—are greater (Humphries & Gill, 2003; Shumaker, et al, 2003; Wassertheil-Smoller, et al, 2003). In addition, there is no evidence of increased quality of life improvements (general health, vitality, mental health, depressive symptoms, or sexual satisfaction) as claimed for HRT (Hays et al, 2003).

“As a result of recent studies, we know that hormone therapy should not be used to prevent heart disease. These studies also report an increased risk of heart attack, stroke, breast cancer, blood clots, and dementia…” -Wyeth Pharmaceuticals (2003)

Because of the increased long-term risk and lack of benefit, many physicians are weaning women off HRT at a time when the largest population of maturing women in history (‘baby boomers’) is entering menopausal years. The desire to find a reliable remedy for hot flashes is on the front burner of many researchers’ minds, not to mention the minds of women suffering from these ‘uncontrollable’ power surges. Yet, many women are becoming increasingly leery of the view that menopause is an illness. There is a rising demand to find a natural remedy for this natural stage in women’s health and development.

For younger women a similar dilemma occurs when they seek treatment of discomfort associated with their menstrual cycle. Is premenstrual syndrome (PMS) just a natural variation in energy and mood levels? Or, are women expected to adapt to a masculine based environment that requires them to override the natural tendency to perform in rhythm with their own psychophysiological states? Instead of perceiving menstruation as a natural occurrence in which one has different moods and/or energy levels, women in our society are required to perform at the status quo, which may contribute to PMS. The feelings and mood changes are quickly labeled as pathology that can only be treated with medication.

Traditionally, premenstrual syndrome is treated with pharmaceuticals, such as birth control pills or Danazol. Although medications may alleviate some symptoms, many women experience unpleasant side effects, such as bloating or acne, and still experience a variety of PMS symptoms. Many cannot tolerate the medications. Thus, millions of women (and families) suffer monthly bouts of ‘uncontrollable’ PMS symptoms

For both hot flashes and PMS the biomedical model tends to frame the symptoms as a “structural biological problem.” Namely, the pathology occurs because the body is either lacking in, or has an excess of, some hormone. All that needs to be done is either augment or suppress hormones/symptoms with some form of drug. Recently, for example, medicine has turned to antidepressant medications to address menopausal hot flashes (Stearns, Beebe, Iyengar, & Dube, 2003).

The biomedical model, however, is only one perspective. The opposite perspective is that the dysfunction occurs because of how we use ourselves. Use in this sense means our thoughts, emotions and body patterns. As we use ourselves, we change our physiology and, thereby, may affect and slowly change the predisposing and maintaining factors that contribute to our dysfunction. By changing our use, we may reduce the constraints that limit the expression of the self-healing potential that is intrinsic in each person.