Quick Rescue Techniques When Stressed

Posted: February 4, 2024 Filed under: attention, behavior, biofeedback, Breathing/respiration, CBT, cognitive behavior therapy, education, emotions, Evolutionary perspective, Exercise/movement, health, mindfulness, Neck and shoulder discomfort, posture, relaxation, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: alarm reaction, anxiety, box breathing, Breathing, conditioning, defense reaction, health, huming, Parasympathetic response, rumination, safety, sniff inhale, somatic practices, stress, sympathetic arousal, tactical breathing, Toning, yoga 2 CommentsErik Peper, PhD, Yuval Oded, PhD, and Richard Harvey, PhD

Adapted from Peper, E., Oded, Y, & Harvey, R. (2024). Quick somatic rescue techniques when stressed. Biofeedback, 52(1).

“If a problem is fixable, if a situation is such that you can do something about it, then there is no need to worry. If it’s not fixable, then there is no help in worrying. There is no benefit in worrying whatsoever.” ― Dalai Lama XIV

To implement the Dalai Lama’s quote is challenging. When caught up in an argument, being angry, extremely frustrated, or totally stressed, it is easy to ruminate, worry. It is much more challenging to remember to stay calm. When remembering the message of the Dalai Lama’s quote, it may be possible to shift perspective about the situation although a mindful attitude may not stop ruminating thoughts. The body typically continues to reacti to the torrents of thoughts that may occur when rehashing rage over injustices, fear over physical or psychological threats, or profound grief and sadness over the loss of a family member. Some people become even more agitated and less rational as illustrated in the following examples.

I had an argument with my ex and I am still pissed off. Each time I think of him or anticipate seeing them, my whole body tightened. I cannot stomach seeing him and I already see the anger in his face and voice. My thoughts kept rehashing the conflict and I am getting more and more upset.

A car cut right in front of me to squeeze into my lane. I had to slam on my brakes. What an idiot! My heart rate was racing and I wanted to punch the driver.

When threatened, we respond quickly in our thoughts and body with a defense reaction that may negatively affect those around us as well as ourselves. What can we do to interrupt negative stress reactions?

Background

Many approaches exist that allow us to become calmer and less reactive. General categories include techniques of cognitive reappraisal (seeing the situation from the other person’s point of view and labeling your own feelings and emotions) and stress management techniques. Practices that are beneficial include mindfulness meditation, benign humor (versus gallows humor), listening to music, taking a time out while implementing a variety of self-soothing practices, or incorporating slow breathing (e.g., heart rate variability and/or box breathing) throughout the day.

No technique fits all as we respond differently to our stressful life circumstances. For example, some people during stress react with a “tend and befriend stress response” (Cohen & Lansing, 2021; Taylor et al., 2000). This response appears to be mostly mediated by the hormone oxytocin acting in ways that sooth or calm the nervous system as an analgesic. These neurophysiological mechanisms of the soothing with the calming analgesic effects of oxytocin have been characterized in detail by Xin, et al. (2017).

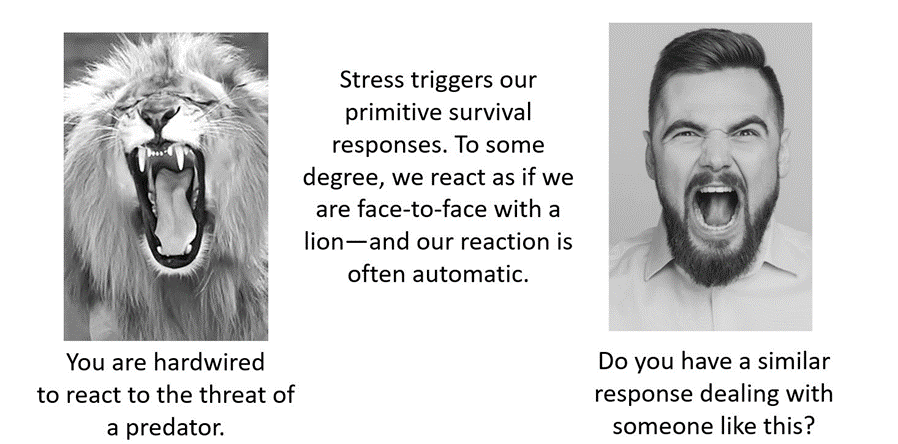

The most common response is a fight/flight/freeze stress response that is mediated by excitatory hormones such as adrenalin and inhibitory neurotransmitters such as gamma amino butyric acid (GABA). There is a long history of fight/flight/freeze stress response research, which is beyond the scope of this blog with major theories and terms such as interior milleau (Bernard, 1872); homeostasis and fight/flight (Cannon, 1929); general adaptation syndrome (Selye, 1951); polyvagal theory (Porges, 1995); and, allostatic load (McEwen, 1998). A simplified way to start a discussion about stress reactions begins with the fight/flight stress response. When stressed our defense reactions are triggered. Our sympathetic nervous system becomes activated our mind and body stereotypically responds as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. An intense confrontation tends to evoke a stress response (reproduced from Peper et al., 2020).

The flight/fight response triggers a cascade of stress hormones or neurotransmitters (e.g., hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal cascade) and produces body changes such as the heart pounding, quicker breathing, an increase in muscle tension and sweating. Our body mobilizes itself to protect itself from danger. Our focus is on immediate survival and not what will occur in the future (Porges, 2021; Sapolsky, 2004). It is as if we are facing an angry lion—a life-threatening situation—and we feel threatened and unsafe.

Rather than sitting still, a quick effective strategy is to interrupt this fight/flight response process by completing the alarm reaction such as by moving our muscles (e.g., simulating a fight or flight behavior) before continuing with slower breathing or other self-soothing strategies. Many people have experienced their body tension is reduced and they feel calmer when they do vigorous exercise after being upset, frustrated or angry. Similarly, athletes often have reported that they experience reduced frequency and/or intensity of negative thoughts after an exhausting workout (Thayer, 2003; Liao et al., 2015; Basso & Suzuki, 2017).

Becoming aware of the escalating cascades of physical, behavioral and psychological responses to a stressor is the first step in interrupting the escalating process. After becoming aware, reduce the body’s arousal and change the though patterns using any of the techniques described in this blog. The self-regulation skills presented in this blog are ideally over-learned and automated so that these skills can be rapidly implemented to shift from being stressed to being calm. Examples of skills that can shift from sympathetic neervous system overarousal to parasympathetic nervous system calm include techniques of autogenic traing (Schulz & Luthe, 1959), the quieting reflex developed by Charles Stroebel in 1985 or more recently rescue breathing developed by Richard Gevirtz (Stroebel, 1985; Gevirtz, 2014; Peper, Gibney & Holt, 2002; Peper & Gibney, 2003).

Concepts underlying the rescue techniques

- Psychophysiological principle: “Every change in the physiological state is accompanied by an appropriate change in the mental-emotional state, conscious or unconscious, and conversely, every change in the mental-emotional state, conscious or unconscious, is accompanied by an appropriate change in the physiological state” (Green et al. 1970, p. 3).

- Posture evokes memories and feelings associated with the position. When the body posture is erect and tall while looking slightly up. It is easier to evoke empowering, positive thoughts and feelings. When looking down it is easier to evoke hopeless, helpless and powerless thoughts and feelings (Peper et al., 2017).

- Healing occurs more easily when relaxed and feeling safe. Feeling safe and nurtured enhances the parasympathetic state and reduces the sympathetic state. Use memory recall to evoke those experiences when you felt safe (Peper, 2021).

- Interrupting thoughts is easier with somatic movement than by redirecting attention and thinking of something else without somatic movement.

- Focus on what you want to do not want to do. Attempting to stop thinking or ruminating about something tends to keeps it present (e.g., do not think of pink elephants. What color is the elephant? When you answer, “not pink,” you are still thinking pink). A general concept is to direct your attention (or have others guide you) to something else (Hilt & Pollak, 2012; Oded, 2018; Seo, 2023).

- Skill mastery takes practice and role rehearsal (Lally et al., 2010; Peper & Wilson, 2021).

- Use classical conditioning concepts to facilitate shifting states. Practice the skills and associate them with an aroma, memory, sounds or touch cues. Then when you the situation occurs, use these classical conditioned cues to facilitate the regeneration response (Peper & Wilson, 2021).

Rescue techniques

Coping When Highly Stressed and Agitated

- Complete the alarm/defense reaction with physical activity (Be careful when you do these physical exercises if you have back, hip, knee, or ankle problems).

- Acknowledge you have reacted and have chosen to interrupt your automatic response.

- Check whether the situation is actually a threat. If yes, then do anything to get out of immediate danger (yell, scream, fight, run away, or dial 911).

- If there is no actual physical threat, then leave the situation and perform vigorous physical activity to complete your alarm reaction, such as going for a run or walking quickly up and down stairs. As you do the exercise, push yourself so that the muscles in your thighs are aching, which focusses your attention on the sensations in your thighs. In our experience, an intensive run for 20 minutes quiets the brain while it often takes 40 minutes when walking somewhat quickly.

- After recovering from the exhaustive exercise, explore new options to resolve the conflict.

- Complete the alarm/defense reaction and evoke calmness with the S.O.S™ technique (Oded, 2023)

- Acknowledge you have reacted and have chosen to interrupt your automatic response.

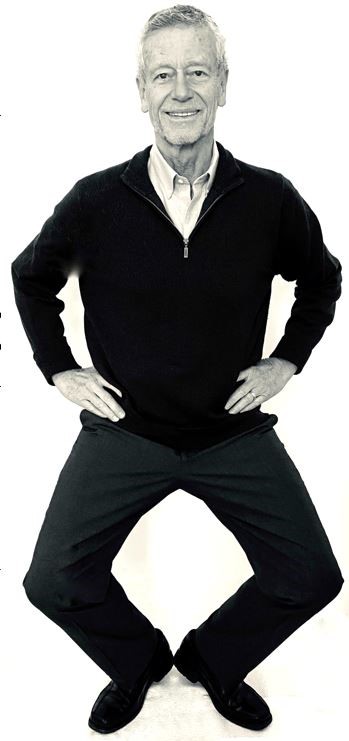

- Squat against a wall (similar to the wall-sit many skiers practice). While tensing your arms and fists as shown in Figure 2, gaze upward because it is more difficult to engage in negative thinking while looking upwards. If you continue to ruminate, then scan the room for object of a certain color or feature to shift visual attention and be totally present on the visual object.

- Do this set of movements for 7 to 10 seconds or until you start shaking. Than stand up and relax hands and legs. While standing, bounce up and down loosely for 10 to 15 seconds as you become aware of the vibratory sensations in your arms and shoulders, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2.Defense position wall-sit to tighten muscles in the protective defense posture (Oded, 2023). Figure 3. Bouncing up and down to loosen muscles ((Oded, 2023).

- Acknowledge you have reacted and have chosen to interrupt your automatic response. Swing your arms back and forth for 20 seconds. Allow the arms to swing freely as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Swinging the arms to loosen the body and spine (Oded, 2023).

- Rest and ground. Lie on the floor and put your calves and feet on a chair seat so that the psoas muscle can relax, as illustrated in Figure 5. Allow yourself to be totally supported by the floor and chair. Be sure there is a small pillow under your head and put your hand on your abdomen so that you can focus on abdominal breathing.

Figure 5. Lying down to allow the psoas muscle to relax and feel grounded (Oded, 2023).

- While lying down, imagine a safe place or memory and make it as real as possible. It is often helpful to listen to a guided imagery or music. The experience can be enhanced if cues are present that are associated with the safe place, such as pictures, sounds, or smells. Continue to breathe effortlessly at about six breaths per minute. If your attention wanders, bring it back to the memory or to the breathing. Allow yourself to rest for 10 minutes.

In most cases, thoughts stop and the body’s parasympathetic activity becomes dominant as the person feels safe and calm. Usually, the hands warm and the blood volume pulse amplitude increases as an indicator of feeling safe, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Blood volume pulse increases as the person is relaxing, feels safe and calm.

Coping When You Can’t Get Away (adapted from Peper, Harvey & Faass, 2020)

In many cases, it is difficult or embarrassing to remove yourself from the situation when you are stressed out such as at work, in a business meeting or social gathering.

- Become aware that you have reacted.

- Excuse yourself for a moment and go to a private space, such as a restroom. Going to the bathroom is one of the only acceptable social behaviors to leave a meeting for a short time.

- In the bathroom stall, do the 5-minute Nyingma exercise, which was taught by Tarthang Tulku Rinpoche in the tradition of Tibetan Buddhism, as a strategy for thought stopping (see Figure 7). Stand on your toes with your heels touching each other. Lift your heels off the floor while bending your knees. Place your hands at your sides and look upward. Breathe slowly and deeply (e.g., belly breathing at six breaths a minute) and imagine the air circulating through your legs and arms. Do this slow breathing and visualization next to a wall so you can steady yourself if necessary to keep balance. Stay in this position for 5 minutes or longer. Do not straighten your legs—keep squatting despite the discomfort. In a very short time, your attention is captured by the burning sensation in your thighs. Continue. After 5 minutes, stop and shake your arms and legs.

Figure 7. Stressor squat Nyingma exercise (reproduced from Peper et al., 2020).

- Follow this practice with slow abdominal breathing to enhance the parasympathetic response. Be sure that the abdomen expands as the inhalation occurs. Breathe in and out through the nose at about six breaths per minute.

- Once you feel centered and peaceful, return to the room.

- After this exercise, your racing thoughts most likely will have stopped and you will be able to continue your day with greater calm.

What to do When Ruminating, Agitated, Anxious or Depressed

(adapted from Peper, Harvey, & Hamiel, 2019).

- Shift your position by sitting or standing erect in a power position with the back of the head reaching upward to the ceiling while slightly gazing upward. Then sniff quickly through nose, hold and again sniff quickly then very slowly exhale. Be sure as you exhale your abdomen constricts. Then sniff again as your abdomen gets bigger, hold, and sniff one more time letting the abdomen get even bigger. Then, very slow, exhale through the nose to the internal count of six (adapted from Balban et al., 2023). When you sniff or gasp, your racing thoughts will stop (Peper et al., 2016).

- Continue with box breathing (sometimes described as tactical breathing or battle breathing) by exhaling slowly through your nose for 4 seconds, holding your breath for 4 seconds, inhaling slowly for 4 seconds through your nose, holding your breath for 4 seconds and then repeating this cycle of breathing for a few minutes (Röttger et al., 2021; Balban et al., 2023). Focusing your attention on performing the box breathing makes it almost impossible to think of anything else. After a few minutes, follow this with slow effortless diaphragmatic breathing at about six breaths per minute. While exhaling slowly through your nose, look up and when you inhale imagine the air coming from above you. Then as you exhale, imagine and feel the air flowing down and through your arms and legs and out the hands and feet.

- While gazing upward, elicit a positive memory or a time when you felt safe, powerful, strong and/or grounded. Make the positive memory as real as possible.

- Implement cognitive strategies such as reframing the issue, sending goodwill to the person, seeing the problem from the other person’s point of view, and ask is this problem worth dying over (Peper, Harvey, & Hamiel, 2019).

What to Do When Thoughts Keep Interrupting

Practice humming or toning. When you are humming or toning, your focus is on making the sound and the thoughts tend to stop. Generally, breathing will slow down to about six breaths per minute (Peper, Pollack et al., 2019). Explore the following:

- Box breathing (Röttger et al., 2021; Balban et al., 2023)

- Humming also known as bee breath (Bhramari Pranayama) (Abishek et al., 2019; Yoga, 2023) – Allow the tongue to rest against the upper palate, sit tall and erect so that the back of the head is reaching upward to the ceiling, and inhale through your nose as the abdomen expands. Then begin humming while the air flows out through your nose, feel the vibration in the nose, face and throat. Let humming last for about 7 seconds and then allow the air to blow in through the nose and then hum again. Continue for about 5 minutes.

- Toning – Inhale through your nose and then vocalize a single sound such as Om. As you vocalize the lower sound, feel the vibration in your throat, chest and even going down to the abdomen. Let each toning exhalation last for about 6 to 7 seconds and then inhale through your nose. Continue for about 5 minutes (Peper, al., 2019).

Many people report that after practice these skills, they become aware that they are reacting and are able to reduce their automatic reaction. As a result, they experience a significant decrease in their stress levels, fewer symptoms such as neck and holder tension and high blood pressure, and they feel an increase in tranquility and the ability to communicate effectively.

Practicing these skills does not resolve the conflicts; they allow you to stop reacting automatically. This process allows you a time out and may give you the ability to be calmer, which allows you to think more clearly. When calmer, problem solving is usually more successful. As phrased in a popular meme, “You cannot see your reflection in boiling water. Similarly, you cannot see the truth in a state of anger. When the waters calm, clarity comes” (author unknown).

Boiling water (photo modified from: https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=388991500314839&set=a.377199901493999)

Below are additional resources that describe the practices. Please share these resources with friends, family and co-workers.

Stressor squat instructions

Toning instructions

Diaphragmatic breathing instructions

Reduce stress with posture and breathing

Conditioning

References

Abishek, K., Bakshi, S. S., & Bhavanani, A. B. (2019). The efficacy of yogic breathing exercise bhramari pranayama in relieving symptoms of chronic rhinosinusitis. International Journal of Yoga, 12(2), 120–123. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijoy.IJOY_32_18

Balban, M. Y., Neri, E., Kogon, M. M., Weed, L., Nouriani, B., Jo, B., Holl, G., Zeitzer, J. M., Spiegel, D., Huberman, A. D. (2023). Brief structured respiration practices enhance mood and reduce physiological arousal. Cell Reports Medicine, 4(1), 10089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100895

Basso, J. C. & Suzuki, W. A. (2017). The effects of acute exercise on mood, cognition, neurophysiology, and neurochemical pathways: A review. Brain Plast, 2(2), 127–152. https://doi.org/10.3233/BPL-160040

Bernard, C. (1872). De la physiologie générale. Paris: Hachette livre. https://www.amazon.ca/PHYSIOLOGIE-GENERALE-BERNARD-C/dp/2012178596

Cannon, W. B. (1929). Organization for Physiological Homeostasis. Physiological Reviews, 9, 399–431. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.1929.9.3.399

Cohen, L. & Lansing, A. H. (2021). The tend and befriend theory of stress: Understanding the biological, evolutionary, and psychosocial aspects of the female stress response. In: Hazlett-Stevens, H. (eds), Biopsychosocial Factors of Stress, and Mindfulness for Stress Reduction. pp. 67–81, Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81245-4_3

Gevirtz, R. (2014). HRV Training and its Importance – Richard Gevirtz, Ph.D., Pioneer in HRV Research & Training. Thought Technology. Accessed December 29, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9nwFUKuJSE0

Green, E. E., Green, A. M., & Walters, E. D. (1970). Voluntary control of internal states: Psychological and physiological. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 2, 1–26. https://atpweb.org/jtparchive/trps-02-70-01-001.pdf

Hilt, L. M., & Pollak, S. D. (2012). Getting out of rumination: comparison of three brief interventions in a sample of youth. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40(7), 1157–1165.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-012-9638-3

Lally, P., VanJaarsveld, C. H., Potts, H. W., & Wardle, J. (2010). How habits are formed: Modelling habit formation the real world. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 998–1009. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.674

Liao, Y., Shonkoff, E. T., & Dunton, G. F. (2015). The acute relationships between affect, physical feeling states, and physical activity in daily life: A review of current evidence. Frontiers in Psychology. 6, 1975. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01975

McEwen, B. S. (1998). Stress, adaptation, and disease: Allostasis and allostatic load. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 840(1), 33–44.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09546.x

Oded, Y. (2018). Integrating mindfulness and biofeedback in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Biofeedback, 46(2), 37-47. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-46.02.03

Oded, Y. (2023). Personal communication. S.O.S 1™ technique is part of the Sense Of Safety™ method. www.senseofsafety.co

Peper, E. (2021). Relive memory to create healing imagery. Somatics, XVIII(4), 32–35.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/369114535_Relive_memory_to_create_healing_imagery

Peper, E., Gibney, K.H. & Holt. C. (2002). Make Health Happen: Training Yourself to Create Wellness. Dubuque, IA: Kendall-Hunt. https://he.kendallhunt.com/product/make-health-happen-training-yourself-create-wellness

Peper, E., & Gibney, K.H. (2003). A teaching strategy for successful hand warming. Somatics. XIV(1), 26–30. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/376954376_A_teaching_strategy_for_successful_hand_warming

Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Faass, N. (2020). TechStress: How Technology is Hijacking Our Lives, Strategies for Coping, and Pragmatic Ergonomics. North Atlantic Books. https://www.amazon.com/Beyond-Ergonomics-Prevent-Fatigue-Burnout/dp/158394768X

Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Hamiel, D. (2019). Transforming thoughts with postural awareness to increase therapeutic and teaching efficacy. NeuroRegulation, 6(3),153–160. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.6.3.153

Peper, E., Lee, S., Harvey, R., & Lin, I-M. (2016). Breathing and math performance: Implication for performance and neurotherapy. NeuroRegulation, 3(4), 142–149. http://dx.doi.org/10.15540/nr.3.4.142

Peper, E., Lin, I-M, Harvey, R., & Perez, J. (2017). How posture affects memory recall and mood. Biofeedback, 45(2), 36–41. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-45.2.01

Peper, E., Pollack, W., Harvey, R., Yoshino, A., Daubenmier, J. & Anziani, M. (2019). Which quiets the mind more quickly and increases HRV: Toning or mindfulness? NeuroRegulation, 6(3), 128–133. https://www.neuroregulation.org/article/view/19345/13263

Peper, E. & Wilson, V. (2021). Optimize the learning state: Techniques and habits. Biofeedback, 9(2), 46–49. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-49-2-04

Porges, S. W. (1995). Orienting in a defensive world: Mammalian modifications of our evolutionary heritage. A polyvagal theory. Psychophysiology, 32(4), 301–318. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.1995.tb01213.x

Porges, S.W. (2021) Cardiac vagal tone: a neurophysiological mechanism that evolved in mammals to dampen threat reactions and promote sociality. World Psychiatry, 20(2),296-298. Porges SW. Cardiac vagal tone: a neurophysiological mechanism that evolved in mammals to dampen threat reactions and promote sociality. World Psychiatry. 2021 Jun;20(2):296-298. https://doi.org10.1002/wps.20871

Röttger, S., Theobald, D. A., Abendroth, J., & Jacobsen, T. (2021). The effectiveness of combat tactical breathing as compared with prolonged exhalation. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 46, 19–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-020-09485-w

Sapolsky, R. (2004). Why zebras don’t get ulcers (3rd ed.). New York:Holt. https://www.amazon.com/Why-Zebras-Dont-Ulcers-Third/dp/0805073698/

Schultz, J. H., & Luthe, W. (1959). Autogenic training: A psychophysiologic approach to psychotherapy. Grune & Stratton. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Autogenic_Training/y8SwQgAACAAJ?hl=en

Selye, H. (1951). The general-adaptation-syndrome. Annual Review of Medicine, 2(1), 327–342. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.me.02.020151.001551

Seo, H. (2023). How to stop ruminating. The New York Times. Accessed January 3, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/01/well/mind/stop-rumination-worry.html

Stroebel, C. F. (1985). QR: The Quieting Reflex. Berkley. https://www.amazon.com/Qr-quieting-reflex-Charles-Stroebel/dp/0425085066

Taylor, S. E., Klein, L. C., Lewis, B. P., Gruenewald, T. L., Gurung, R. A. R., & Updegraff, J. A. (2000). Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: Tend-and-befriend, not fight-or-flight. Psychological Review, 107(3), 411–429. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.107.3.411

Thayer, R. E. (2003). Calm energy: How people regulate mood with food and exercise. Oxford University Press. https://www.amazon.com/Calm-Energy-People-Regulate-Exercise/dp/0195163397

Xin, Q., Bai, B., & Liu, W. (2017). The analgesic effects of oxytocin in the peripheral and central nervous system. Neurochemistry International, 103, 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuint.2016.12.021

Yoga, N. (2023). This simple breath practice is scientifically proven to calm your mind. The nomadic yogi. Accessed December 31, 2023. https://www.leahsugerman.com/blog/bhramari-pranayama-humming-bee-breath#

Relive memory to create healing imagery

Posted: February 15, 2019 Filed under: behavior, health, placebo, relaxation, self-healing, Uncategorized | Tags: conditioning, Imagery, Pavlov, visualization 3 Comments

This blog describes a structured imagery that evokes past memories of joy and health and integrates them into a relaxation practice to support healing. First, a look at the logic for the practice and then the process of creating your own personal imagery script. A sample audio file is included as a model for creating your MP3 file. The blog is adapted from Peper, E., Gibney, K.H. & Holt. C. (2002). Make Health Happen: Training Yourself to Create Wellness. Dubuque, IA: Kendall-Hunt.

“I enjoyed regressing back into my childhood, remembered playing in the rain, making paper sailboats with my brother…. Placing my fingers in a bowl of water and stroking a paper sailboat enabled me to participate in the total experience… I felt tingling sensations all over my body, like tiny bundles of energy exploding inside of me. By the end of the week the simple word “rain” could induce these sensations inside my whole being.”–Student

Daydreaming! We all know how to do it. When we daydream, we feel, sense, hear, and taste our daydream—the image becomes tangible, as if we are living it. A well-developed relaxation image can also include colors, scents, sounds, flavors, temperature, and so forth. Evoking a past memory image of wholeness may contribute significant to healing, as illustrated in Pavlov’s experience with controlled conditioning and with self-healing.

THE POWER OF CONDITIONING

Pavlov’s experience

Most of us are probably familiar with the classical conditioning experiment of the famous Russian physiologist, Ivan Pavlov, who taught dogs to salivate on cue when they heard a bell ring—even when no food was provided. Pavlov accomplished this by giving the dogs food immediately after ringing a bell. Eventually, the dogs became conditioned to expect the food with the bell and simply hearing the bell ring would induce salivation (shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1. The process of classical conditioning. (Figure adapted from: https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontopsychology/chapter/7-1-learning-by-association-classical-conditioning/)

The conditioning effects of imagery can have an effect on health as well as physiology as reflected in an anecdote told by Theodore Melnechuk about Ivan Pavlov. As an old man, he became quite ill with heart disease and his doctors had no hope of curing him. They took his family aside and told them that the end was near. Pavlov himself, however, was not disheartened. He asked the nurse who was caring for him to bring him a bowl of warm water with a little dirt or mud in it. All day, as he lay in bed, he dabbled one hand in the water, with a dreamy, faraway look on his face. His family was quite sure that he had taken leave of his wits and would die soon. However, the next morning he announced that he felt fine, ate a large breakfast, and sat out in the sun awhile. By the end of the day, when the doctor came to check on him, there was no trace of the heart condition. When asked to explain what he had done, he said that he had reasoned that if he could recall a time when he was completely carefree and happy, it might have some healing benefit for him. As a young boy, he used to spend his summers playing with his friends in a shallow swimming hole in a nearby river. The memory of the warm, slightly muddy water was delightful to him. With his knowledge of the power of conditioned stimuli, he reasoned that having a physical reminder of that water might help him evoke that experience and those blissful feelings, and bring some of those memories into the present time. Using this strategy, he harnessed positive memory and the associated emotions that evoked the associated body changes to bring about his healing.

Conditioned Behaviors

We all performs many conditioned behaviors every day. Some of these behaviors can have implications for our health and wellness. There may be aspects of allergic reactions that are conditioned. For example, the literature reports that a woman who was allergic to roses developed a severe allergic reaction to a very realistic-looking paper rose, even though she was not allergic to paper. Her body reacted as if the paper rose was real. (McKenzie, 1886; Vits et al, 2011).

Conditioning can also affect our immune system. When rats were injected with a powerful immune-suppressing drug, while being fed saccharin-flavored water, their immune function showed an immediate drop. After the drug and saccharine water were paired a number of times, the rats were then given just the saccharin water and a harmless injection of salt water. Their immune cells responded exactly as if they had received the drug! The reverse ability, increasing immune cell function, has been shown to be influenced through conditioning (Ader, Cohen & Felten, 1995; Ader and Cohen, 1993).

Belief can also play a role in these scenarios. Bernie Siegel, MD,(2011) has recounted the story of a woman scheduled for chemotherapy who was first given a saline solution, and cautioned that it could cause hair loss. Although this is an unlikely result of a saline injection, given her belief, her hair fell out.

Actions, thoughts, and images affect our physiology.

We often anticipate, react, and form conclusions with incomplete information. Thoughts and images affect our physiology and even our immune system. Re-evoking a positive memory and living in that memory could potentially improve your health. In a remarkable study by a Harvard psychologist, Ellen Langer, eight men in their 70s lived together for one week, recreating aspects of the world that they had experienced more than 20 years earlier. They were instructed to act as they had in 1959, while the control group was instructed to focus entirely on the present time.

In the experimental group, all the physical cues were reminiscent of the culture twenty years earlier. Black and white television and magazines were from 1959. There were no mirrors to remind them of their current age—only photos on the wall of their younger selves. After a week in which the participants acted as if they were younger and the cues around them evoked their younger selves, 63% of the experimental group had improved their cognitive performance as compared with 44% of the control group. Among participants in the experimental group, even their physical health had improved. Independent raters who looked at the before and after pictures of these participants rated their appearance a little younger than the photos taken before the experiment (Langer, 2009; Grierson, 2014; Friedman, 2015). It is possible that by acting and thinking younger, we actually stay younger!

The limits of our belief are the limits of our experience. This concept underlies the remarkable power of placebo. If one believes a drug or a procedure is helpful, that can have a powerful healing effect (Peper & Harvey, 2017; also see the blog, How effective is treatment? The importance of active placebos).

CREATE YOUR OWN VISUALIZATION

Begin by remembering a time when you felt happy, healthy, and whole. Draw inspiration from Pavlov, who evoked happy memories from his childhood, apparently dramatically changing his health. To develop your personal visualization, set aside the time to recreate a healing memory. Remember a time in your life when you felt healthy and joyous (possibly from your childhood). For some, this might be time in nature or with your family or with friends.

Once you remember the event, re-experience it as if you were there right now. Evoke as many senses as possible. Think of the memory and any associations such as an old teddy bear, a shell from the beach, a favorite song, a certain perfume or some other tangible aspect of the experience. The goal is to recreate the experience as if it was current reality. Olfactory and gustatory cues can be especially powerful. If possible include the actual objects and cues associated with that memory—articles, pictures, music, songs, fragrances, or even food.

Sounds, scents, or touching and objects from that era of your life can deepen your ability to recreate and experience the quality of that memory—to actually be in the memory. These sensory reminders will help to evoke the memory and increase the felt experience. You might find it helpful to review Ellen Langer’s experiment, recreating an environment from twenty years earlier. The actual cues will deepen the experience, just as aromas often evoke specific memories and emotions.

The underlying principle is that memories are associated with conditioned stimuli that evoke the physiological state(s) in the body present when the memory was created.

Once you have created a vivid memory that engenders a sense of wholeness, develop a detailed description of your memory to help you evoke that experience. (For some, the memory calls up a timeless setting—relaxing on a warm beach, sitting in front of the fire on a winter evening, or sailing on a calm day. For others, the sense of trust may be associated with a specific person—someone you love—being with your grandmother, helping your mother bake a cake, or going fishing with your dad.). As you recreate the experience, engage all your senses (images, fragrance, tastes, textures, sounds, kinetics). Stay in your image: see it, smell it, taste it, touch it, hear it, be it and allow the experience to deepen.

Begin by writing up your imagery. Then record the introduction the structured relaxation and follow it with a description that evokes the memory as an MP3 audiofile. Use the following three-step process to create the script for your personal relaxation.

- Describe a time in your past when you felt joy, peace, love, or a sense of integration and wholeness.

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

- Identify the specific cues or stimuli associated with that memory.

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

- Write out a detailed description that will evoke your personal memory.

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

CREATING YOUR AUDIO FILE

In this approach, there are three components to your script: first, a relaxation practice to ease you into your visualization, then the visualization of your memory, closing with a brief script that brings you back into the present moment.

Begin the recording with progressive relaxation—use your favorite process for relaxing, or apply the script included here.

Generally tense the muscles for about 5 to 8 seconds and let go for 15 to 20 seconds as indicated by the …. inthe script. While tightening and relaxing the muscles, sense the muscle sensations with passive attention. Tense only the muscles that you are instructed to tighten and continue to breathe while tensing and relaxing the muscles. If your attention wanders, gently bring it back to feeling the sensations in the specific muscles that you are instructed to tighten or relax.

First, find a comfortable position for relaxation… To fully relax your face, squeeze your eyes shut tight, press your lips and teeth together, and wrinkle up your nose… feel the tightness in your whole face… Now let it go completely and relax… Allow your face to soften, feel the eyes sinking in their sockets, and your breath to flow effortlessly in and out…

Tense both arms by making fists, and extend them straight ahead, while continuing to breathe deeply… study the tension… Now relax and let your arms drop as if you were a rag doll… To relax your shoulders, hunch them toward your ears and tighten your neck, while keeping the rest of your body loose and relaxed… Continue to breathe easily… Allow your shoulders to drop… Feel the weight of your arms… Feel the relaxation flowing from your shoulders, down your arms into your hands and out your fingers…

Now your stomach. Then let go and relax… Arch your back and feel the tightness in the back. Let go and relax….Allow your body to sink comfortably into the surface on which you are resting… Finally, tighten your butt, thighs, calves, and feet by pressing your heels down into the surface where you are lying, curling your toes and squeezing your knees together… Feel the tension as you continue to breathe, keeping your upper body relaxed… Now let go and relax… Allow relaxation to flow through your legs… Be aware of the sensations of letting go…

Feel the deepening relaxation, the calmness and the serenity… Feel each exhalation flowing down and through your arms, chest, and legs… Let the feelings of relaxation and heaviness deepen as you relax more… Notice the developing sense of inner peace… a calm indifference to external events… Let the feelings of relaxation, calmness, and serenity deepen for a few minutes. After a few minutes, evoke your memory of wholeness.

Insert your imagery script here.

Finish with the brief closing script

Allow yourself to just stay in this special place all your own… and know that you can return to this peaceful sanctuary any time you choose to do so. When you are ready to release the imagery, take a deep breath, gently stretch your body, and open your eyes.

Record these this whole script on your cell phone as an MP3 file.

When you record, it often takes a few tries before the pacing is correct. You may find it helpful to listen to the following audio file as a model for to create your own.

LISTENING TO YOUR VISUALIZATION

Create a sanctuary for yourself by turning off your cellphone, adjusting the heat to a comfortable temperature, and ensuring that you will have uninterrupted quiet time for 20 to 30 minutes. Loosen any constricting clothing or jewelry, your glasses, and so on. Settle into a comfortable chair, bed, or setting where you can easily relax. Enjoy letting yourself drift into and relive the memory experience.

Many participants report that this practice is an exceptionally relaxing and nurturing experience, one that supports regeneration. You’ll probably find that the more you practice, the more the relaxation deepens. You may find it helpful to keep notes and observe how you feel after each practice. Although it may feel strange to listen to your own voice, most people find that after a while it becomes more comfortable. After listening to it for a few times, you may want to rerecord the script. Finally, generalize this practice by smiling and evoking the memory scene as much as you desire during the day.

Additional strategies to enhance the relaxation

- Have a massage or take a warm shower or soak and then do the practice. Compare your level of relaxation afterwards to the result of using the audio alone.

- Practice gentle stretches to loosen tight muscles or “shake out” your arms and legs just before doing your relaxation practice.

- Draw or paint the relaxing image or actually go to the location where your memory occurred (if possible) and do your practice. Or practice outdoors in the most relaxing place you can find. Nature can be a great healer.

- Create an atmosphere that helps to evoke and augment your relaxation image (e.g., play background music or use fragrances that you associated with the image).

Common challenges

- Inability to evoke a memory of wholeness. When this occurs, it is as if one draws a blank. This is common, especially if one has experienced abuse or feels depressed. In that case, use the image presented in the script or make one up and create a totally imaginary peaceful image.

- Positive memories of wholeness evoke a bitter/sweet feeling. This occurs when images of wholeness include a loved one who has passed on or who is no longer in your life. On the one hand, this may call up strongly positive feelings, but it may evoke a sense of loss and sadness. If this occurs, simply chose a different memory or create a different script. Let the memory of loss go. Accept your experience and your feelings as much as possible, and know that at least you have been loved. For your image, it may be easier to focus on a natural setting you love—one you associate with peace and tranquility.

- Lack of experience with places in nature. Some people have only urban experiences and find nature alien. See what comes up for you. Does your favorite memory as a city kid recall a day of freedom on your bike or skateboarding, or an afternoon with your playmates? Perhaps you have treasured memories as a teen or an adult of long walks in the city or time spent with close friends. You also have the option of creating new images such as sitting by a fireplace, in a walled garden, or some other scene of peace and safety.

- Difficulty using progressive relaxation. If you’re having trouble isolating a muscle: touch it, stroke it with your hands, and then tense it fully (without strain) and feel the tension in your hands; feel the difference with your hands as you let go of the tension. Or, you may tighten only as much as is needed to feel the tension.

- The desire to stay in the imagery and not wanting to return to reality. If the imagery is much more pleasant than the present, use this process as a stimulus to reorganize your life and set new goals and priorities.

References

Ader, R. & Cohen, N. (1993). Psychoneuroimmunology, Conditioning,_and_Stress. Annual Review of Psychology, 44(1), 53-85.

Ader, R., Cohen, N. and Felten, D. (1995) Psychoneuroimmunology: Interactions between the Nervous System and the Immune System. The Lancet, 345, 99-103.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(95)90066-7

Friedman, L. F. (2015). A radical experiment tried to make old people young again–and the results were astonishing . https://www.businessinsider.com/ellen-langers-reversing-aging-experiment-2015-4

Grierson, B. (2014). What if age is nothing more than a mind-set? New York Times Magazine. October 22.

Langer, E. (2009). Counterclockwise: Mindful Health and the Power of Possibility . New York: Ballantine Books.

McKenzie, J. (1886). The production of the so-called rose effect by means of an artificial rose, with remarks and historical notes. Am. J. Med. Sci. 91, 45–57

Peper, E., Gibney, K.H. & Holt. C. (2002). Make Health Happen: Training Yourself to Create Wellness . Dubuque, IA: Kendall-Hunt. ISBN-13: 978-0787293314

Peper, E. & Harvey, R. (2017). The fallacy of placebo controlled clinical trials: Are positive outcomes the result of indirect treatment side effects? NeuroRegulation. 4(3–4), 102–113. doi:10.15540/nr.4.3-4.102

Siegel, B. (2011, May). Remarkable recoveries. Retrieved from: http://berniesiegelmd.com/resources/articles/remarkable-recoveries/

Vits, S., Cesko, E., Enck, P., Hillen, U., Schadendorf, D., & Schedlowski, M. (2011). Behavioural conditioning as the mediator of placebo responses in the immune system. Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences, 366(1572), 1799–1807. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23035535