Quick Rescue Techniques When Stressed

Posted: February 4, 2024 Filed under: attention, behavior, biofeedback, Breathing/respiration, CBT, cognitive behavior therapy, education, emotions, Evolutionary perspective, Exercise/movement, health, mindfulness, Neck and shoulder discomfort, posture, relaxation, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: alarm reaction, anxiety, box breathing, Breathing, conditioning, defense reaction, health, huming, Parasympathetic response, rumination, safety, sniff inhale, somatic practices, stress, sympathetic arousal, tactical breathing, Toning, yoga 2 CommentsErik Peper, PhD, Yuval Oded, PhD, and Richard Harvey, PhD

Adapted from Peper, E., Oded, Y, & Harvey, R. (2024). Quick somatic rescue techniques when stressed. Biofeedback, 52(1), 18–26. https://doi.org/10.5298/982312

“If a problem is fixable, if a situation is such that you can do something about it, then there is no need to worry. If it’s not fixable, then there is no help in worrying. There is no benefit in worrying whatsoever.” ― Dalai Lama XIV

To implement the Dalai Lama’s quote is challenging. When caught up in an argument, being angry, extremely frustrated, or totally stressed, it is easy to ruminate, worry. It is much more challenging to remember to stay calm. When remembering the message of the Dalai Lama’s quote, it may be possible to shift perspective about the situation although a mindful attitude may not stop ruminating thoughts. The body typically continues to reacti to the torrents of thoughts that may occur when rehashing rage over injustices, fear over physical or psychological threats, or profound grief and sadness over the loss of a family member. Some people become even more agitated and less rational as illustrated in the following examples.

I had an argument with my ex and I am still pissed off. Each time I think of him or anticipate seeing them, my whole body tightened. I cannot stomach seeing him and I already see the anger in his face and voice. My thoughts kept rehashing the conflict and I am getting more and more upset.

A car cut right in front of me to squeeze into my lane. I had to slam on my brakes. What an idiot! My heart rate was racing and I wanted to punch the driver.

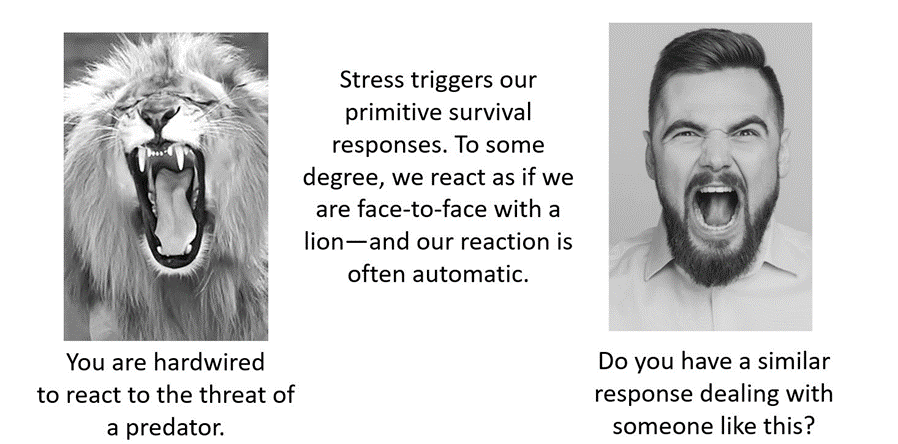

When threatened, we respond quickly in our thoughts and body with a defense reaction that may negatively affect those around us as well as ourselves. What can we do to interrupt negative stress reactions?

Background

Many approaches exist that allow us to become calmer and less reactive. General categories include techniques of cognitive reappraisal (seeing the situation from the other person’s point of view and labeling your own feelings and emotions) and stress management techniques. Practices that are beneficial include mindfulness meditation, benign humor (versus gallows humor), listening to music, taking a time out while implementing a variety of self-soothing practices, or incorporating slow breathing (e.g., heart rate variability and/or box breathing) throughout the day.

No technique fits all as we respond differently to our stressful life circumstances. For example, some people during stress react with a “tend and befriend stress response” (Cohen & Lansing, 2021; Taylor et al., 2000). This response appears to be mostly mediated by the hormone oxytocin acting in ways that sooth or calm the nervous system as an analgesic. These neurophysiological mechanisms of the soothing with the calming analgesic effects of oxytocin have been characterized in detail by Xin, et al. (2017).

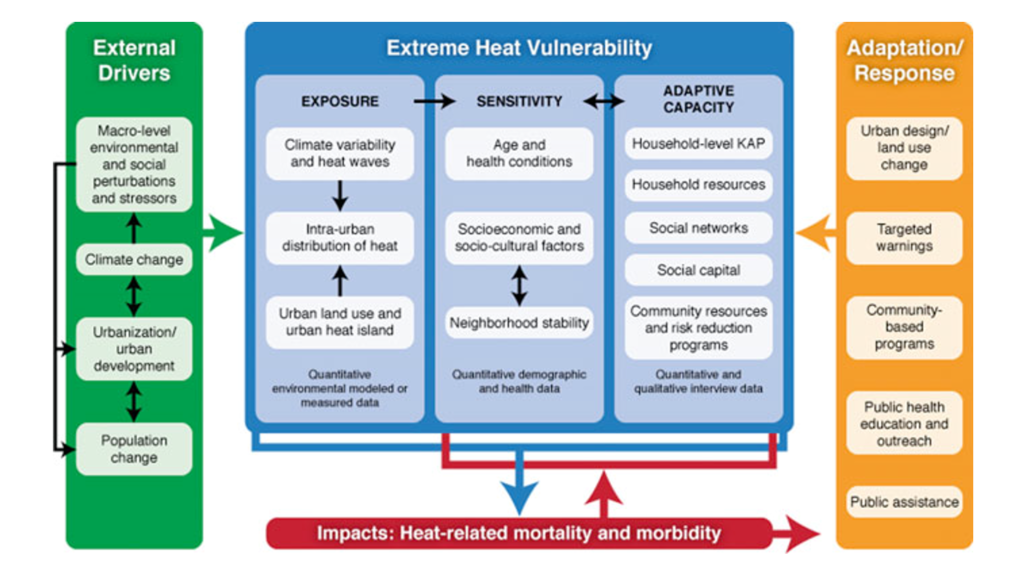

The most common response is a fight/flight/freeze stress response that is mediated by excitatory hormones such as adrenalin and inhibitory neurotransmitters such as gamma amino butyric acid (GABA). There is a long history of fight/flight/freeze stress response research, which is beyond the scope of this blog with major theories and terms such as interior milleau (Bernard, 1872); homeostasis and fight/flight (Cannon, 1929); general adaptation syndrome (Selye, 1951); polyvagal theory (Porges, 1995); and, allostatic load (McEwen, 1998). A simplified way to start a discussion about stress reactions begins with the fight/flight stress response. When stressed our defense reactions are triggered. Our sympathetic nervous system becomes activated our mind and body stereotypically responds as illustrated in Figure 1.

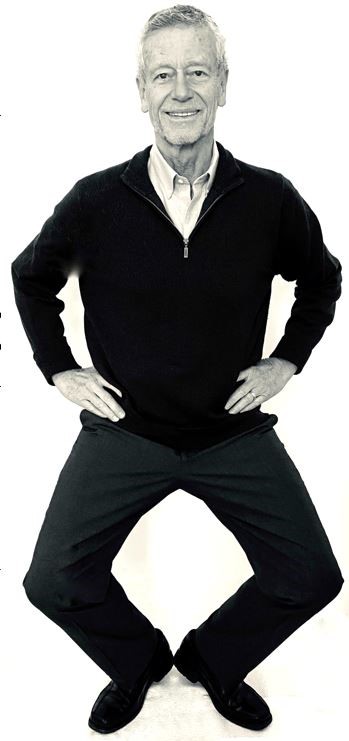

Figure 1. An intense confrontation tends to evoke a stress response (reproduced from Peper et al., 2020).

The flight/fight response triggers a cascade of stress hormones or neurotransmitters (e.g., hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal cascade) and produces body changes such as the heart pounding, quicker breathing, an increase in muscle tension and sweating. Our body mobilizes itself to protect itself from danger. Our focus is on immediate survival and not what will occur in the future (Porges, 2021; Sapolsky, 2004). It is as if we are facing an angry lion—a life-threatening situation—and we feel threatened and unsafe.

Rather than sitting still, a quick effective strategy is to interrupt this fight/flight response process by completing the alarm reaction such as by moving our muscles (e.g., simulating a fight or flight behavior) before continuing with slower breathing or other self-soothing strategies. Many people have experienced their body tension is reduced and they feel calmer when they do vigorous exercise after being upset, frustrated or angry. Similarly, athletes often have reported that they experience reduced frequency and/or intensity of negative thoughts after an exhausting workout (Thayer, 2003; Liao et al., 2015; Basso & Suzuki, 2017).

Becoming aware of the escalating cascades of physical, behavioral and psychological responses to a stressor is the first step in interrupting the escalating process. After becoming aware, reduce the body’s arousal and change the though patterns using any of the techniques described in this blog. The self-regulation skills presented in this blog are ideally over-learned and automated so that these skills can be rapidly implemented to shift from being stressed to being calm. Examples of skills that can shift from sympathetic neervous system overarousal to parasympathetic nervous system calm include techniques of autogenic traing (Schulz & Luthe, 1959), the quieting reflex developed by Charles Stroebel in 1985 or more recently rescue breathing developed by Richard Gevirtz (Stroebel, 1985; Gevirtz, 2014; Peper, Gibney & Holt, 2002; Peper & Gibney, 2003).

Concepts underlying the rescue techniques

- Psychophysiological principle: “Every change in the physiological state is accompanied by an appropriate change in the mental-emotional state, conscious or unconscious, and conversely, every change in the mental-emotional state, conscious or unconscious, is accompanied by an appropriate change in the physiological state” (Green et al. 1970, p. 3).

- Posture evokes memories and feelings associated with the position. When the body posture is erect and tall while looking slightly up. It is easier to evoke empowering, positive thoughts and feelings. When looking down it is easier to evoke hopeless, helpless and powerless thoughts and feelings (Peper et al., 2017).

- Healing occurs more easily when relaxed and feeling safe. Feeling safe and nurtured enhances the parasympathetic state and reduces the sympathetic state. Use memory recall to evoke those experiences when you felt safe (Peper, 2021).

- Interrupting thoughts is easier with somatic movement than by redirecting attention and thinking of something else without somatic movement.

- Focus on what you want to do not want to do. Attempting to stop thinking or ruminating about something tends to keeps it present (e.g., do not think of pink elephants. What color is the elephant? When you answer, “not pink,” you are still thinking pink). A general concept is to direct your attention (or have others guide you) to something else (Hilt & Pollak, 2012; Oded, 2018; Seo, 2023).

- Skill mastery takes practice and role rehearsal (Lally et al., 2010; Peper & Wilson, 2021).

- Use classical conditioning concepts to facilitate shifting states. Practice the skills and associate them with an aroma, memory, sounds or touch cues. Then when you the situation occurs, use these classical conditioned cues to facilitate the regeneration response (Peper & Wilson, 2021).

Rescue techniques

Coping When Highly Stressed and Agitated

- Complete the alarm/defense reaction with physical activity (Be careful when you do these physical exercises if you have back, hip, knee, or ankle problems).

- Acknowledge you have reacted and have chosen to interrupt your automatic response.

- Check whether the situation is actually a threat. If yes, then do anything to get out of immediate danger (yell, scream, fight, run away, or dial 911).

- If there is no actual physical threat, then leave the situation and perform vigorous physical activity to complete your alarm reaction, such as going for a run or walking quickly up and down stairs. As you do the exercise, push yourself so that the muscles in your thighs are aching, which focusses your attention on the sensations in your thighs. In our experience, an intensive run for 20 minutes quiets the brain while it often takes 40 minutes when walking somewhat quickly.

- After recovering from the exhaustive exercise, explore new options to resolve the conflict.

- Complete the alarm/defense reaction and evoke calmness with the S.O.S™ technique (Oded, 2023)

- Acknowledge you have reacted and have chosen to interrupt your automatic response.

- Squat against a wall (similar to the wall-sit many skiers practice). While tensing your arms and fists as shown in Figure 2, gaze upward because it is more difficult to engage in negative thinking while looking upwards. If you continue to ruminate, then scan the room for object of a certain color or feature to shift visual attention and be totally present on the visual object.

- Do this set of movements for 7 to 10 seconds or until you start shaking. Than stand up and relax hands and legs. While standing, bounce up and down loosely for 10 to 15 seconds as you become aware of the vibratory sensations in your arms and shoulders, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2.Defense position wall-sit to tighten muscles in the protective defense posture (Oded, 2023). Figure 3. Bouncing up and down to loosen muscles ((Oded, 2023).

- Acknowledge you have reacted and have chosen to interrupt your automatic response. Swing your arms back and forth for 20 seconds. Allow the arms to swing freely as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Swinging the arms to loosen the body and spine (Oded, 2023).

- Rest and ground. Lie on the floor and put your calves and feet on a chair seat so that the psoas muscle can relax, as illustrated in Figure 5. Allow yourself to be totally supported by the floor and chair. Be sure there is a small pillow under your head and put your hand on your abdomen so that you can focus on abdominal breathing.

Figure 5. Lying down to allow the psoas muscle to relax and feel grounded (Oded, 2023).

- While lying down, imagine a safe place or memory and make it as real as possible. It is often helpful to listen to a guided imagery or music. The experience can be enhanced if cues are present that are associated with the safe place, such as pictures, sounds, or smells. Continue to breathe effortlessly at about six breaths per minute. If your attention wanders, bring it back to the memory or to the breathing. Allow yourself to rest for 10 minutes.

In most cases, thoughts stop and the body’s parasympathetic activity becomes dominant as the person feels safe and calm. Usually, the hands warm and the blood volume pulse amplitude increases as an indicator of feeling safe, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Blood volume pulse increases as the person is relaxing, feels safe and calm.

Coping When You Can’t Get Away (adapted from Peper, Harvey & Faass, 2020)

In many cases, it is difficult or embarrassing to remove yourself from the situation when you are stressed out such as at work, in a business meeting or social gathering.

- Become aware that you have reacted.

- Excuse yourself for a moment and go to a private space, such as a restroom. Going to the bathroom is one of the only acceptable social behaviors to leave a meeting for a short time.

- In the bathroom stall, do the 5-minute Nyingma exercise, which was taught by Tarthang Tulku Rinpoche in the tradition of Tibetan Buddhism, as a strategy for thought stopping (see Figure 7). Stand on your toes with your heels touching each other. Lift your heels off the floor while bending your knees. Place your hands at your sides and look upward. Breathe slowly and deeply (e.g., belly breathing at six breaths a minute) and imagine the air circulating through your legs and arms. Do this slow breathing and visualization next to a wall so you can steady yourself if necessary to keep balance. Stay in this position for 5 minutes or longer. Do not straighten your legs—keep squatting despite the discomfort. In a very short time, your attention is captured by the burning sensation in your thighs. Continue. After 5 minutes, stop and shake your arms and legs.

Figure 7. Stressor squat Nyingma exercise (reproduced from Peper et al., 2020).

- Follow this practice with slow abdominal breathing to enhance the parasympathetic response. Be sure that the abdomen expands as the inhalation occurs. Breathe in and out through the nose at about six breaths per minute.

- Once you feel centered and peaceful, return to the room.

- After this exercise, your racing thoughts most likely will have stopped and you will be able to continue your day with greater calm.

What to do When Ruminating, Agitated, Anxious or Depressed

(adapted from Peper, Harvey, & Hamiel, 2019).

- Shift your position by sitting or standing erect in a power position with the back of the head reaching upward to the ceiling while slightly gazing upward. Then sniff quickly through nose, hold and again sniff quickly then very slowly exhale. Be sure as you exhale your abdomen constricts. Then sniff again as your abdomen gets bigger, hold, and sniff one more time letting the abdomen get even bigger. Then, very slow, exhale through the nose to the internal count of six (adapted from Balban et al., 2023). When you sniff or gasp, your racing thoughts will stop (Peper et al., 2016).

- Continue with box breathing (sometimes described as tactical breathing or battle breathing) by exhaling slowly through your nose for 4 seconds, holding your breath for 4 seconds, inhaling slowly for 4 seconds through your nose, holding your breath for 4 seconds and then repeating this cycle of breathing for a few minutes (Röttger et al., 2021; Balban et al., 2023). Focusing your attention on performing the box breathing makes it almost impossible to think of anything else. After a few minutes, follow this with slow effortless diaphragmatic breathing at about six breaths per minute. While exhaling slowly through your nose, look up and when you inhale imagine the air coming from above you. Then as you exhale, imagine and feel the air flowing down and through your arms and legs and out the hands and feet.

- While gazing upward, elicit a positive memory or a time when you felt safe, powerful, strong and/or grounded. Make the positive memory as real as possible.

- Implement cognitive strategies such as reframing the issue, sending goodwill to the person, seeing the problem from the other person’s point of view, and ask is this problem worth dying over (Peper, Harvey, & Hamiel, 2019).

What to Do When Thoughts Keep Interrupting

Practice humming or toning. When you are humming or toning, your focus is on making the sound and the thoughts tend to stop. Generally, breathing will slow down to about six breaths per minute (Peper, Pollack et al., 2019). Explore the following:

- Box breathing (Röttger et al., 2021; Balban et al., 2023)

- Humming also known as bee breath (Bhramari Pranayama) (Abishek et al., 2019; Yoga, 2023) – Allow the tongue to rest against the upper palate, sit tall and erect so that the back of the head is reaching upward to the ceiling, and inhale through your nose as the abdomen expands. Then begin humming while the air flows out through your nose, feel the vibration in the nose, face and throat. Let humming last for about 7 seconds and then allow the air to blow in through the nose and then hum again. Continue for about 5 minutes.

- Toning – Inhale through your nose and then vocalize a single sound such as Om. As you vocalize the lower sound, feel the vibration in your throat, chest and even going down to the abdomen. Let each toning exhalation last for about 6 to 7 seconds and then inhale through your nose. Continue for about 5 minutes (Peper, al., 2019).

Many people report that after practice these skills, they become aware that they are reacting and are able to reduce their automatic reaction. As a result, they experience a significant decrease in their stress levels, fewer symptoms such as neck and holder tension and high blood pressure, and they feel an increase in tranquility and the ability to communicate effectively.

Practicing these skills does not resolve the conflicts; they allow you to stop reacting automatically. This process allows you a time out and may give you the ability to be calmer, which allows you to think more clearly. When calmer, problem solving is usually more successful. As phrased in a popular meme, “You cannot see your reflection in boiling water. Similarly, you cannot see the truth in a state of anger. When the waters calm, clarity comes” (author unknown).

Boiling water (photo modified from: https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=388991500314839&set=a.377199901493999)

Below are additional resources that describe the practices. Please share these resources with friends, family and co-workers.

Stressor squat instructions

Toning instructions

Diaphragmatic breathing instructions

Reduce stress with posture and breathing

Conditioning

References

Abishek, K., Bakshi, S. S., & Bhavanani, A. B. (2019). The efficacy of yogic breathing exercise bhramari pranayama in relieving symptoms of chronic rhinosinusitis. International Journal of Yoga, 12(2), 120–123. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijoy.IJOY_32_18

Balban, M. Y., Neri, E., Kogon, M. M., Weed, L., Nouriani, B., Jo, B., Holl, G., Zeitzer, J. M., Spiegel, D., Huberman, A. D. (2023). Brief structured respiration practices enhance mood and reduce physiological arousal. Cell Reports Medicine, 4(1), 10089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100895

Basso, J. C. & Suzuki, W. A. (2017). The effects of acute exercise on mood, cognition, neurophysiology, and neurochemical pathways: A review. Brain Plast, 2(2), 127–152. https://doi.org/10.3233/BPL-160040

Bernard, C. (1872). De la physiologie générale. Paris: Hachette livre. https://www.amazon.ca/PHYSIOLOGIE-GENERALE-BERNARD-C/dp/2012178596

Cannon, W. B. (1929). Organization for Physiological Homeostasis. Physiological Reviews, 9, 399–431. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.1929.9.3.399

Cohen, L. & Lansing, A. H. (2021). The tend and befriend theory of stress: Understanding the biological, evolutionary, and psychosocial aspects of the female stress response. In: Hazlett-Stevens, H. (eds), Biopsychosocial Factors of Stress, and Mindfulness for Stress Reduction. pp. 67–81, Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81245-4_3

Gevirtz, R. (2014). HRV Training and its Importance – Richard Gevirtz, Ph.D., Pioneer in HRV Research & Training. Thought Technology. Accessed December 29, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9nwFUKuJSE0

Green, E. E., Green, A. M., & Walters, E. D. (1970). Voluntary control of internal states: Psychological and physiological. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 2, 1–26. https://atpweb.org/jtparchive/trps-02-70-01-001.pdf

Hilt, L. M., & Pollak, S. D. (2012). Getting out of rumination: comparison of three brief interventions in a sample of youth. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40(7), 1157–1165.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-012-9638-3

Lally, P., VanJaarsveld, C. H., Potts, H. W., & Wardle, J. (2010). How habits are formed: Modelling habit formation the real world. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 998–1009. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.674

Liao, Y., Shonkoff, E. T., & Dunton, G. F. (2015). The acute relationships between affect, physical feeling states, and physical activity in daily life: A review of current evidence. Frontiers in Psychology. 6, 1975. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01975

McEwen, B. S. (1998). Stress, adaptation, and disease: Allostasis and allostatic load. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 840(1), 33–44.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09546.x

Oded, Y. (2018). Integrating mindfulness and biofeedback in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Biofeedback, 46(2), 37-47. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-46.02.03

Oded, Y. (2023). Personal communication. S.O.S 1™ technique is part of the Sense Of Safety™ method. www.senseofsafety.co

Peper, E. (2021). Relive memory to create healing imagery. Somatics, XVIII(4), 32–35.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/369114535_Relive_memory_to_create_healing_imagery

Peper, E., Gibney, K.H. & Holt. C. (2002). Make Health Happen: Training Yourself to Create Wellness. Dubuque, IA: Kendall-Hunt. https://he.kendallhunt.com/product/make-health-happen-training-yourself-create-wellness

Peper, E., & Gibney, K.H. (2003). A teaching strategy for successful hand warming. Somatics. XIV(1), 26–30. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/376954376_A_teaching_strategy_for_successful_hand_warming

Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Faass, N. (2020). TechStress: How Technology is Hijacking Our Lives, Strategies for Coping, and Pragmatic Ergonomics. North Atlantic Books. https://www.amazon.com/Beyond-Ergonomics-Prevent-Fatigue-Burnout/dp/158394768X

Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Hamiel, D. (2019). Transforming thoughts with postural awareness to increase therapeutic and teaching efficacy. NeuroRegulation, 6(3),153–160. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.6.3.153

Peper, E., Lee, S., Harvey, R., & Lin, I-M. (2016). Breathing and math performance: Implication for performance and neurotherapy. NeuroRegulation, 3(4), 142–149. http://dx.doi.org/10.15540/nr.3.4.142

Peper, E., Lin, I-M, Harvey, R., & Perez, J. (2017). How posture affects memory recall and mood. Biofeedback, 45(2), 36–41. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-45.2.01

Peper, E., Pollack, W., Harvey, R., Yoshino, A., Daubenmier, J. & Anziani, M. (2019). Which quiets the mind more quickly and increases HRV: Toning or mindfulness? NeuroRegulation, 6(3), 128–133. https://www.neuroregulation.org/article/view/19345/13263

Peper, E. & Wilson, V. (2021). Optimize the learning state: Techniques and habits. Biofeedback, 9(2), 46–49. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-49-2-04

Porges, S. W. (1995). Orienting in a defensive world: Mammalian modifications of our evolutionary heritage. A polyvagal theory. Psychophysiology, 32(4), 301–318. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.1995.tb01213.x

Porges, S.W. (2021) Cardiac vagal tone: a neurophysiological mechanism that evolved in mammals to dampen threat reactions and promote sociality. World Psychiatry, 20(2),296-298. Porges SW. Cardiac vagal tone: a neurophysiological mechanism that evolved in mammals to dampen threat reactions and promote sociality. World Psychiatry. 2021 Jun;20(2):296-298. https://doi.org10.1002/wps.20871

Röttger, S., Theobald, D. A., Abendroth, J., & Jacobsen, T. (2021). The effectiveness of combat tactical breathing as compared with prolonged exhalation. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 46, 19–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-020-09485-w

Sapolsky, R. (2004). Why zebras don’t get ulcers (3rd ed.). New York:Holt. https://www.amazon.com/Why-Zebras-Dont-Ulcers-Third/dp/0805073698/

Schultz, J. H., & Luthe, W. (1959). Autogenic training: A psychophysiologic approach to psychotherapy. Grune & Stratton. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Autogenic_Training/y8SwQgAACAAJ?hl=en

Selye, H. (1951). The general-adaptation-syndrome. Annual Review of Medicine, 2(1), 327–342. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.me.02.020151.001551

Seo, H. (2023). How to stop ruminating. The New York Times. Accessed January 3, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/01/well/mind/stop-rumination-worry.html

Stroebel, C. F. (1985). QR: The Quieting Reflex. Berkley. https://www.amazon.com/Qr-quieting-reflex-Charles-Stroebel/dp/0425085066

Taylor, S. E., Klein, L. C., Lewis, B. P., Gruenewald, T. L., Gurung, R. A. R., & Updegraff, J. A. (2000). Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: Tend-and-befriend, not fight-or-flight. Psychological Review, 107(3), 411–429. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.107.3.411

Thayer, R. E. (2003). Calm energy: How people regulate mood with food and exercise. Oxford University Press. https://www.amazon.com/Calm-Energy-People-Regulate-Exercise/dp/0195163397

Xin, Q., Bai, B., & Liu, W. (2017). The analgesic effects of oxytocin in the peripheral and central nervous system. Neurochemistry International, 103, 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuint.2016.12.021

Yoga, N. (2023). This simple breath practice is scientifically proven to calm your mind. The nomadic yogi. Accessed December 31, 2023. https://www.leahsugerman.com/blog/bhramari-pranayama-humming-bee-breath#

Reduce the risk for colds and flu and superb science podcasts

Posted: January 24, 2024 Filed under: attention, behavior, education, Evolutionary perspective, Exercise/movement, healing, health, Nutrition/diet, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized, vision | Tags: colds, darkness, flu, influenza, light 1 Comment

What can we do to reduce the risk of catching a cold or the flu? It is very challenging to make sense out of all the recommendations found on internet and the many different media site such as X(Twitter), Facebook, Instagram, or TikTok. The following podcasts are great sources that examine different topics that can affect health. They are in-depth presentations with superb scientific reasoning.

Huberman Lab podcasts discusses science and science based tools for everyday life. https://www.hubermanlab.com/podcast. Select your episode and they are great to listen to on your cellphone.

THE PODCAST episode, How to prevent and treat cold and flu, is outstanding. Skip the long sponsor introductdion and start listening at the 6 minute point. In this podcast, Professor Andrew Huberman describes behavior, nutrition and supplementation-based tools supported by peer-reviewed research to enhance immune system function and better combat colds and flu. I also dispel common myths about how the cold and flu are transmitted and when you and those around you are contagious. I explain if common preventatives and treatments such as vitamin C, zinc, vitamin D and echinacea work. I also highlight other compounds known to reduce contracting and duration of colds and flu. I discuss how to use exercise and sauna to bolster the immune response. This episode will help listeners understand how to reduce the chances of catching a cold or flu and help people recover more quickly from and prevent the spread of colds and flu.

PODCAST, ScienceVS, is an outstanding podcast series that takes on fads, trends, and opinionated mob to find out what’s fact, what’s not, and what’s somewhere in between. Select your episode and listen.

Link: https://gimletmedia.com/shows/science-vs/episodes#show-tab-picker

PODCAST episode, The Journal club podcast and Youtube, presentation from Huberman Lab is a example of outstanding scientific reasoning. In this presentation, Professor Andrew Huberman and Dr. Peter Attia (author of Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity) discuss two peer-reviewed scientific papers in-depth. The first discussion explores the role of bright light exposure during the day and dark exposure during the night and its relationship to mental health. The second paper explores a novel class of immunotherapy treatments to combat cancer.

Rethink the monies spent on cancer screening tests

Posted: November 24, 2023 Filed under: behavior, cancer, Evolutionary perspective, healing, health, Nutrition/diet, self-healing | Tags: breast canceer, Cancer screening, environmental toxins, Life style, mammography, organic foods Leave a commentErik Peper, PhD and Richard Harvey, PhD

Cancer screening tests are based upon the rational that early detection of fatal cancers enables earlier and more effective treatments (Kowalski, 2021), however, there is some controversy. Early screening may increase the risk of over diagnosis, treating false positives (people who did not have the cancer but the test indicates they have cancer) and potentially fatal treatment of cancers that would never progress to increase morbidity or mortality (Kowalski, 2021).

Today about $40 billion spent on colon cancer screening, $15 billion spent on breast cancer screening, and $4 billion spent on prostate cancer screening annually (CSPH, 2021). A question is raised whether the billions and billions of dollars spent on screening asymptomatic participants would be more wisely spent on promoting and supporting life style changes that reduce cancer risks and actually extend life span? That cancer screening is expensive does not mean no one should be screened. Instead, the argument is that the majority of healthcare dollars could be spent on health promotion practices and reserving screening for those people who are at highest risk for developing cancers.

What is the evidence that screening prolongs life?

Cancer screening tests appear correlated with preventing deaths since deaths due to cancers in the USA have decreased by about 28% from 1999 to 2020 (CDC, 2023a). Although cancer causes many of the deaths in the USA, overall life expectancy has increased by less than 1% from 1999 to 2020. If cancer screening were more effective, the life expectancy should have increased more because cancer is the second leading cause of death (CDC, 2023b). Consider also that deaths due to cancers may be coincident and or comorbid with other circumstances. For example, during the last four years, overall life expectancy in the USA has precipitously declined in part due to other causes of death such as the COVID pandemic and opioid overdose epidemic (Lewis, 2022). Decline in life expectancy in the USA has many contributing factors, including the ‘harms’ associated with cancer screening procedures. For example, perforations during colon cancer screening can lead to internal bleeding, or complications related to surgeries, radiotherapies or chemotherapies. Bretthauer et al., (2023) commented: “A cancer screening test may reduce cancer-specific mortality but fail to increase longevity if the harms for some individuals outweigh the benefits for others or if cancer-specific deaths are replaced by deaths from competing cause” (p. 1197).

Bretthauer et al. (2023) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of 18 long-term randomized clinical trials involving 2.1 million Individuals with more than nine years of follow-up reporting on all-cause mortality. They reported that“…this meta-analysis suggest that current evidence does not substantiate the claim that common cancer screening tests save lives by extending lifetime, except possibly for colorectal cancer screening with sigmoidoscopy.”

Following is a summary of Bretthauer et al. (2023) findings:

- The only cancer screening with a significant lifetime gain (approximately 3 months) was sigmoidoscopy.

- There was no significant difference between harms of screening and benefits of screening for:

- mammography

- prostate cancer screening

- FOBT (fecal occult blood test) screening every year or every other year

- lung cancer screening Pap test cytology for cervical cancer screening, no randomized clinical trials with cancer-specific or all-cause mortality end points and long term follow-up were identified.

Potential for loss or harm (e.g., iatrogenic and nosocomial) versus potential for benefit and extended life

More than 35 years ago a significant decrease in breast cancer mortality was observed after mammography was implemented. The correlation suggested a causal relationship that screening reduced mortality (Fracheboud, 2004). This correlation made logical sense since the breast cancer screening test identified cancers early which could then be treated and thereby would result in a decrease in mortality.

How much money is spent on screening that may correlate with unintended harms?

The annual total expenditure for cancer screening is estimated to be between $40-$50 billion annually (CSPH, 2021). Below are some of the estimated expenditures for common tests other than colorectal cancer screening, which arguably is costly; however, has potential benefits that outweigh potential harms.

- $10.37-13.94 billion for mammography to screen 50% of eligible women (Badal et al, 2023).

- $2-4 billion for prostate cancer (Ma et al., 2014)

- $1-2 billion for lung cancer (Taylor et al., 2022)

What is the correlation between initiation of mammography and decrease in breast cancer mortality?

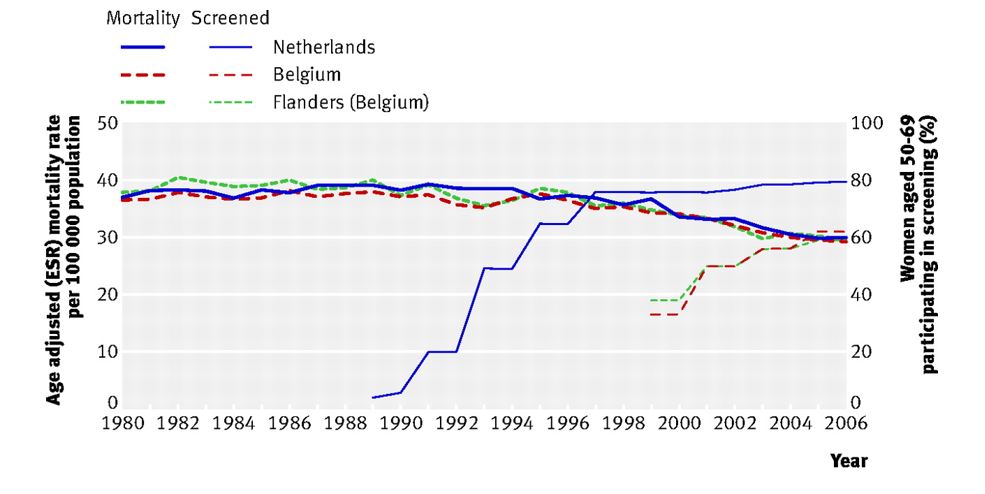

The conclusion that mammography reduced breast cancer mortality was based upon studies without control groups; however, this relationship could be causal or synchronistic. The ambiguity of correlation or causation was resolved with the use of natural experimental control groups. Some European countries began screening 10 years earlier than other countries. Using statistical techniques such as propensity score matching when comparing the data from countries that initiated mammography screening early (Netherlands, Sweden and Northern Ireland) to countries that started screening 10 year later (Belgium, Norway and Republic of Ireland), the effectiveness of screening could be compared.

The comparisons showed no difference in the decrease of breast cancer mortality in countries that initiated breast cancer screening early or late. For example, there was no difference in the decrease of breast cancer mortality rates of women who lived in the Netherlands that started screening early versus those who lived in Belgium that began screening 10 years later, as is shown Figure 1 (Autier et al, 2011).

Figure 1. No difference in age adjust breast cancer mortality between the two adjacent countries even though breast cancer screening began ten years earlier in the Netherlands than in Belgium (graph reproduced from Autier et al, 2011).

The observations are similar when comparing neighboring countries: Sweden (early screening) to Norway (late screening) as well as Northern Ireland, UK (early screening) compared to the Republic of Ireland (late screening). The systematic comparisons showed that screening did not account for the decrease in breast cancer mortality. To what extent could the decrease in mortality be related to other factors such as better prenatal and early childhood diet and life style, improved nutrition, reduction in environmental pollutants, and other unidentified life style and environmental factors which improve immune competence?

A simplistic model to reduce the risk of cancers is described in the following equation (Gorter & Peper, 2011).

Cancer risk can be reduced, arguably by influencing risk factors that contribute to cancers as well as increasing factors to enhance immune competence. In the simple model above, ‘Cancer burden’ refers to the set of exposures that increase the odds of cancer formations. Categories include exposures to oncoviruses, environmental exposures (e.g., ionizing radiation, carcinogenic chemicals) as well as genetic (e.g., chromosomal aberrations, replication errors) and epigenetic factors (e.g., lifestyle categories related to eating, exercising, sleeping, and relaxing). In the model above, ‘Immune competence’ refers to a set of categories of immune functioning related to DNA repair, orderly cell death (i.e., processes of apoptosis), expected autophagy, as well as ‘metabolic rewiring,’ also called cellular energetics, that would allow the body to be able to reduce manage cancers from progressing (Fouad & Aanei, 2017) .

How do we examine the cancer burden/immune competence relationship?

Schmutzler et al., (2022) have suggested personalized and precision-medicine risk-adjusted cancer screening incorporating “… high-throughput “multi-omics” technologies comprising, among others, genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics, which have led to the discovery of new molecular risk factors that seem to interact with each other and with non-genetic risk factors in a multiplicative manner.” The argument is that ‘profit-centered’ medicine could incorporate ‘multi-omics’ into risk-adjusted cancer screening as a way to reduce potential loss or harm due to other cancer screening procedures. Rather than simply screening for cancers using currently invasive or toxic procedures which may do more harm than good, consider more nuanced screening tests aimed at the so-called ‘hallmarks of cancer?’ For example, Hanahan (2022) suggests some technical targets for the multi-omics technologies. The following are some of the precision screening tests possible topersonalized medicine of 14 factors or processes related to:

- cells evading growth suppression

- non-mutational epigenetic reprogramming

- avoiding immune destruction

- enabling replicative immortality

- tumor-promoting inflammation

- polymorphic microbiomes

- activating invasion and metastasis

- inducing or accessing vasculature formation/angiogenesis

- cellular senescence

- genome instability and mutation

- resisting cell death

- deregulating cellular metabolism

- unlocking phenotypic plasticity

- sustaining proliferative signaling

Of the listed categories above, ‘phenotypic plasticity’ (cf. Feinberg, 2007; Gupta et al., 2019) suggests that lifestyle behaviors and environmental exposures play a role in cancer progression and regression.

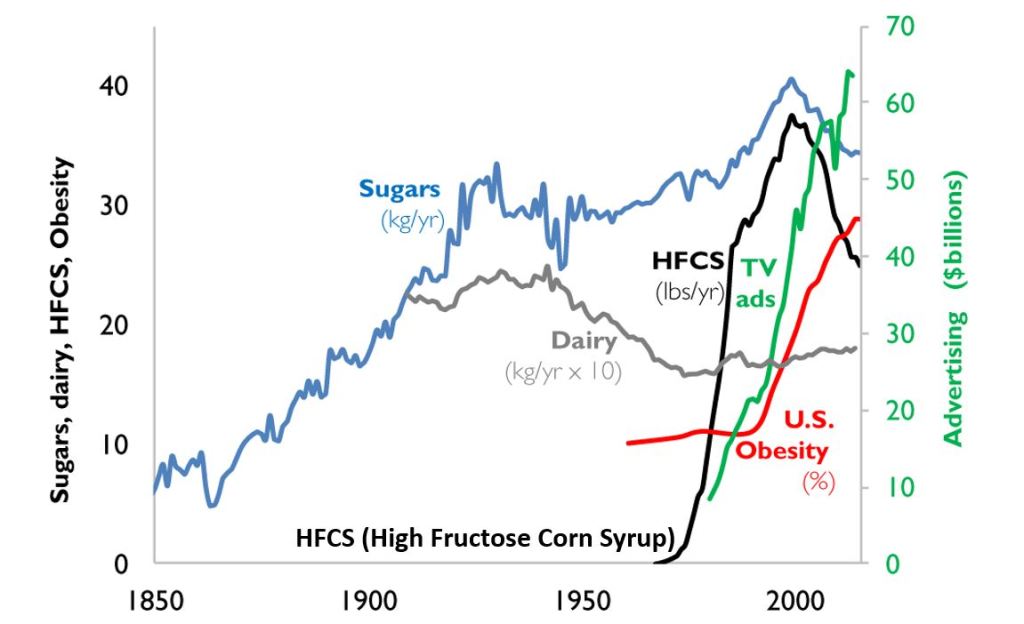

Lifestyle and environmental factors can contribute to the development of cancers.

The 2008-2009 report from the President’s Cancer Panel appraised the National Cancer Program in accordance with the National Cancer Act of 1971 stated (Reuben, 2010):

“We have grossly underestimated the link between environmental toxins, plastics, chemicals, and cancer risk. It is estimated that 70 percent of all cancers were related to diet and environment “

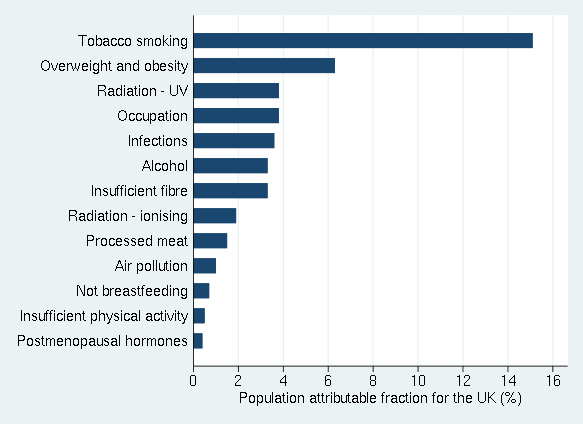

Multiple research studies have shown that a healthy life style pattern is associated with decreased cancer risks and increased longevity. Lifestyle factors that have been documented to increase cancer risks in the United Kingdom (UK) as shown in figure 2.

Figure 2. Percentages of cancer cases in the UK attributable to different exposures. Adapted from Brown et al., 2018 and reproduced by permission from Key et al., 2020.

Similar findings have been reported by Song et al. (2016) from the long term follow-up of 126901 adult health care professionals. People who never smoked, drank no alcohol or moderate alcohol (< 1 drink/d for women; < 2 drinks/d for men}, had a body-mass index (BMI) of at least 18.t but lower than 27.5, did weekly aerobic physical activity of at least 75 vigorous-intensity minutes or 150 150 moderate-intensity minutes compared to those who smoked, drank, had high BMI and did not exercise had nearly half the cancer death rate. Song et al (2016) concludes:

“…about 20% to 40% of carcinoma cases and about half of carcinoma deaths can be potentially prevented through lifestyle modification. Not surprisingly, these figures increased to 40% to 70% when assessed with regard to the population of US whites which has a much worse lifestyle pattern than other cohorts. Notably, approximately 80% to 90% of lung cancer deaths can be avoided if Americans adopted the lifestyle of the low-risk group, mainly by quitting smoking. For other cancers, a range of 10% to 70% of deaths can be prevented. These results provide strong support for the importance of environmental factors in cancer risk and reinforce the enormous potential of primary prevention for cancer control.”

Said another way, primary prevention should remain a priority for cancer control.

Given that many cancers are related to diet, environment and lifestyle, it is estimated that 50% of all cancers and cancer deaths could be prevented by modifying personal behavior. Thus, the monies spent on screening or even developing new treatments could better be spent on prevention along with implementing programs that promote a healthier environment, diet and personal behavior (AACR, 2011).

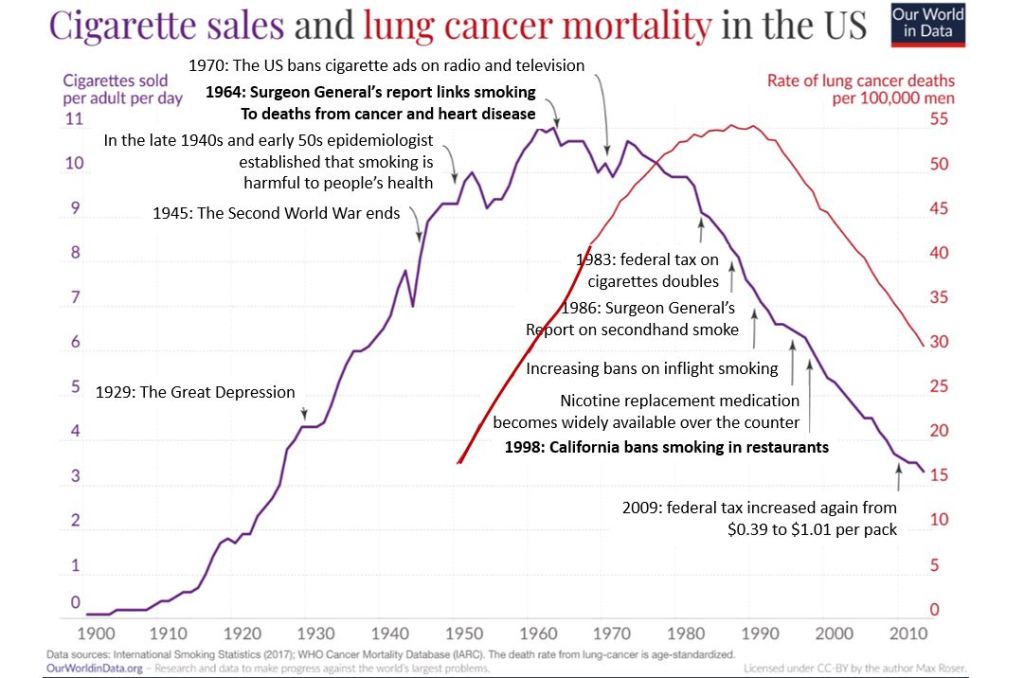

What can be done? Addressing systems not symptoms

From a ‘systems perspective,’ the first step is to reduce the cancer burden and carcinogenic agents that occur in our environment such environmental pollution (Turner et al., 2022). In many cases, governmental regulations that reduce cancer risk factors have been weakened, delayed, and contested for years through industry’s lobbying. It often takes more than 30 years after risk factors have been observed and documented before government regulations are successfully implemented, as exemplified in the battle over tobacco or, air pollution regulations related to particulates from burning fossil fuels (Stratton et al, 2001).

Sadly, we cannot depend upon governments or industries to implement regulations known to reduce cancer risks. More within our control is implementing lifestyle changes that enhance immune competence and promote health.

Implement a healthy life style that enhances immune competence and, supports health and well-being

Paraphrasing a trope of what some physicians may state: ‘Take two pills, and call me in the morning. Oh, and eat well, exercise, and get good rest.’ Broadly stated, the following are some controllable lifestyle behaviors that can decrease cancer risks and promotes health. Implementing environmental and lifestyle changes are very challenging because they are highly related to socio economic factors, cultural factors, industry push for profits over health, and self-care challenges since there are no immediate results experienced by behavior and lifestyle changes.

In many cases, the effects of harmful life-style and environment factors are only observed twenty or more years later (e.g., diabetes, lung cancer, cirrhosis of the liver). The individual does not experience immediate benefits of lifestyle changes thus it is more challenging to know that your healthy life style has an effect. The process is even more complex because in most cases it is not a single factor but the interaction of multiple factors (genetics, lifestyle, and environment). The complexity of causality so often conflicts with the simplistic research studies to identify only one isolated risk factor. Instead of waiting for the definitive governmental guidelines and regulations, adopt a ‘precautionary principle’ which means do not take an action when there is uncertainty about its potential harm (Goldstein, 2001). Do not wait for screening; instead, take charge of your health and implement as many of the following behaviors and strategies to enhance immune competence and thereby reduce cancer risks.

Eat organic foods, especially vegetable and fruits.

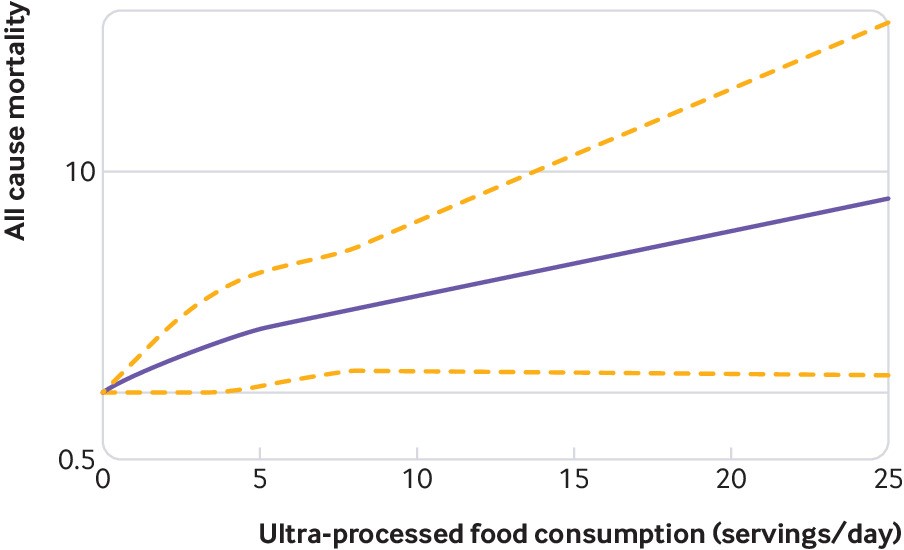

Many studies have suggested that eating organic foods and in particular more fruits and vegetable such as a Mediterranean diet is associated with increased health and longevity. Similarly, people who eat do not eat highly-processed or ultra-processed foods have better health status (Van Tulleken, 2023). For example, In the large prospective study of 68, 946 participants, adults who consumed the most organic fruits, vegetables, dairy products, meat and other foods had 25% fewer cancers when compared with adults who never ate organic food (Baudry et al., 2018; Rabin, 2018). Similarly, many studies have reported that those who adhere consistently to a Mediterranean diet have a significantly lower incidence of chronic diseases (such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, etc.) and cancers compared to those who do not adhere to a Mediterranean diet (Mentella et al., 2019).

Reduce environmental pollution exposure

Air pollution and the exposure to airborne carcinogens are a significant risk factor for cancers as illustrated by the increased cancer rates among smokers. In the USA, the reduction of smoking has significantly decreased the lung cancer deaths (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2014).

Increase movement and exercise

Many studies have documented that people who exercise regularly and are otherwise non–sedentary but are active their entire lives have the lowest risk for breast cancers and colon cancers. Women who exercise 3 hours a week or more have a 30-40% lower risk of developing breast cancer (NIH NCI, 2023). The NIH National Cancer Institute summary concludes that exercises also significantly benefited the following cancer survivors (NIH NCI, 2023):

- Breast cancer: In a 2019 systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies, breast cancer survivors who were the most physically active had a 42% lower risk of death from any cause and a 40% lower risk of death from breast cancer than those who were the least physically active (Spei et al, 2019).

- Colorectal cancer: Evidence from multiple epidemiologic studies suggests that physical activity after a colorectal cancer diagnosis is associated with a 30% lower risk of death from colorectal cancer and a 38% lower risk of death from any cause (Patel et al., 2019).

- Prostate cancer: Limited evidence from a few epidemiologic studies suggests that physical activity after a prostate cancer diagnosis is associated with a 33% lower risk of death from prostate cancer and a 45% lower risk of death from any cause ((Patel et al., 2019).

- Implement stress management.

Chronic stress may reduce immune competence and increase the risk of cancers as well as hinders healing from cancer treatments (Dai et al., 2020). The results of numerous studies have shown that implementing stress management spractices uch as Cognitive-behavioral stress management (CBSM) improves mood and lowers distress during treatment and, is also associated with longer survival compared to control groups in the 8-15 year follow up (Stagl et al., 2015).

Respect your biological rhythm.

The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) reports that, when the human circadian clock is disrupted, the likelihood of developing cancers, including lung cancers, intestinal cancers, and breast cancers, dramatically increases (Huang, et al., 2023). Go to bed at the same time and, have about 8 hours of sleep. As much as possible avoid night shifts at work along with frequent jet lag as that highly disrupts the circadian rhythm.

Increase social connections and be part of a social community

Absence of social support, feeling lonely and socially isolated tends reduces immune competence and increases cancer mortality risk while having more social support satisfaction is associated with lower mortality risks (Salazaor et al., 2023; Boen et al., 2018). Meta-analysis of 148 studies (308,849 participants) found that that on the average there is a 50% increased likelihood of survival for participants with stronger social relationships (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010).

Live a life with meaning and purpose

Having meaning and purpose make each moment worth living and may contribute to improving immune function and possible cancer survival (LeShan, 1994; Rosenbaum & Rosenbaum, 2023).

Summary

The research suggests that cancer screening does not extend life span unless specifically performed for certain diagnostic purposes or, with individuals who are at high risk of developing cancers (e.g., have a genetic predisposition). Implementing self-care health behaviors that have been identified to promote health and increase lifespan. Implementing health behaviors is challenging since there is limited governmental and corporate support. Thus, take charge and implement a holistic self-care lifestyle that reduces cancer risk factors and supports health.

See also the following blogs:

References

AACR. (2011). AACR Cancer Progress Report 2011. American Association for Cancer Research. http://www.aacr.org/Uploads/DocumentRepository/2011CPR/2011_AACR_CPR_Text_web.pdf

American Cancer Society. (2021). History of ACS Recommendations for the Early Detection of Cancer in People Without Symptoms. Accessed November 11, 2023. https://www.cancer.org/health-care-professionals/american-cancer-society-prevention-early-detection-guidelines/overview/chronological-history-of-acs-recommendations.html

Autier, P., Boniol, M., Gavin, A,, & Vatten, L.J. (2011) Breast cancer mortality in neighbouring European countries with different levels of screening but similar access to treatment: trend analysis of WHO mortality database. BMJ. 343, d4411. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d4411

Badal., K., Staib, J., Tice,J., Kim, M-O., Eklund, M., DaCosta Byfield, S., Catlett,K., Wilson,L., et al, (2023). Cost of breast cancer screening in the USA: Comparison of current practice, advocated guidelines, and a personalized risk-based approach. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 41: 16_suppl, 3 18917 :16_suppl, e18917. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2023.41.16_suppl.e18917

Baudry, J., Assmann, K.E., Touvier, M., et al. (2018). Association of Frequency of Organic Food Consumption With Cancer Risk: Findings From the NutriNet-Santé Prospective Cohort Study. JAMA Intern Med, 178(12), 1597–1606. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4357

Boen, C.E., Barrow, D..A, Bensen, J.T., Farnan, L., Gerstel, A., Hendrix, L.H., Yang, Y.C. (2018). Social Relationships, Inflammation, and Cancer Survival. Cancer. Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 27(5), 541-549. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-0836

Bretthauer M, Wieszczy P, Løberg M, et al. (2023). Estimated Lifetime Gained With Cancer Screening Tests: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA Intern Med. 183(11),1196–1203. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.3798Brown, K.F., Rumgay, H., Dunlop, C. et al. (2018). The fraction of cancer attributable to modifiable risk factors in England, Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland, and the United Kingdom in 2015. Br J Cancer, 118, 1130–1141. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-018-0029-6

CDC. (2023a). U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group. U.S. Cancer Statistics Data Visualizations Tool, based on 2022 submission data (1999-2020): U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute; released in November 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/dataviz

CDC. (2023b). Leading Causes of Death. National Center for health statistics, Centers for disease control and prevention. Accessed November 20, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm

CSPH. (2021). Estimating annual expenditures for cancer screening in the United States. Center for Surgery and Public Health. Assessed November 14, 2023. https://csph.brighamandwomens.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Estimating-Annual-Expenditures-for-Cancer-Screening-in-the-United-States.pdf

Dai, S., Mo, Y., Wang, Y., Xiang, B., Liao, Q., Zhou, M., Li, X., Li, Y., Xiong. W., Li, G., Guo, C., & Zeng, Z. (2020). Chronic Stress Promotes Cancer Development. Front Oncol. 10, 1492. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.01492

Feinberg, A. P. (2007). Phenotypic plasticity and the epigenetics of human disease. Nature, 447(7143), 433-440. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05919

Fouad, Y. A., & Aanei, C. (2017). Revisiting the hallmarks of cancer. American journal of cancer research, 7(5), 1016. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28560055/

Fracheboud, J. et al. (2004). Decreased rates of advanced breast cancer due to mammography screening in The Netherlands, British Journal of Cancer (2004) 91, 861–867. https://doi,org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6602075

Goldstein, B.D. (2001). The precautionary principle also applies to public health actions. Am J Public Health, 91(9),1358-61. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.91.9.1358

Gorter, R. & Peper, E. (2011). Fighting Cancer-A None Toxic Approach to Treatment. Berkeley: North Atlantic/New York: Random House. https://www.amazon.com/Fighting-Cancer-Nontoxic-Approach-Treatment/dp/1583942483

Gupta, P. B., Pastushenko, I., Skibinski, A., Blanpain, C., & Kuperwasser, C. (2019). Phenotypic plasticity: driver of cancer initiation, progression, and therapy resistance. Cell Stem Cell, 24(1), 65-78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2018.11.011

Hanahan, Douglas. (2022): Hallmarks of cancer: new dimensions. Cancer discovery, 12(1), 31-46. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-1059

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T.B., & Layton, J.B. (2010). Social Relationships and Mortality Risk: A Meta-analytic Review, PLoS Med 7(7), e1000316. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316

Huang, C., Zhang, C,, Cao, Y., Li, J., & Bi, F. (2023). Major roles of the circadian clock in cancer. Cancer Biol Med, 20(1):1–24. https://doi.org/10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2022.0474

Kalaf, J.M. (2014). Mammography: a history of success and scientific enthusiasm. Radiol Bras. 47(4):VII-VIII. https://doi.org/10.1590/0100-3984.2014.47.4e2

Key TJ, Bradbury KE, Perez-Cornago A, Sinha R, Tsilidis KK, Tsugane S. Diet, nutrition, and cancer risk: what do we know and what is the way forward? BMJ. 2020 Mar 5;368:m511. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m511

Kowalski, A.E. (2021). Mammograms and mortality: How has the evidence evolved? J Econ Perspect, 35(2), 119-140. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.35.2.119

LeShan, L. (1994). Cancer as a turning point. New York: Plume. https://www.amazon.com/Cancer-As-Turning-Point-Professionals/dp/0452271371

Lewis, T. (2022). The U.S. just lost 26 years’ worth of progress on life expectancy. Scientific American. October 17, 2022. Accessed November 11, 2023. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-u-s-just-lost-26-years-worth-of-progress-on-life-expectancy/

Ma, X., Wang, R., Long, J.B., Ross, J.S., Soulos, P.R., Yu, J.B., Makarov, D.V., Gold, H.T. and Gross, C.P. (2014), The cost implications of prostate cancer screening in the Medicare population. Cancer, 120: 96-102. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28373

Mentella, M.C., Scaldaferri, F., Ricci, C., Gasbarrini, A., & Miggiano, G.A.D. (2019). Cancer and Mediterranean Diet: A Review. Nutrients,11(9):2059. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11092059

NIH NCI (2023). Physical Activity and Cancer. National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute. Accessed November 18, 2023. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/obesity/physical-activity-fact-sheet

Patel, A,V., Friedenreich, C.M., Moore, S.C, et al. (2019). American College of Sports Medicine Roundtable Report on physical activity, sedentary behavior, and cancer prevention and control. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 51(11), 2391-2402. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000002117

Rabin, R.C. (2018). Can eating organic food lower your cancer risk? The New York Times. Oct 23, 2018. Accessed November 17, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/23/well/eat/can-eating-organic-food-lower-your-cancer-risk.html

Reuben, S.H. (2010). Reducing environmental cancer risk – What We Can Do Now. The President’s Cancer Panel Report. Washington, D.C: U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. https://deainfo.nci.nih.gov/advisory/pcp/annualReports/pcp08-09rpt/PCP_Report_08-09_508.pdf

Rosenbaum, E. H. & Rosenbaum, I.R. (2023) The Will to Live. Stanford Center for Integrative Medicine. Surviving Cancer. Accessed November 23, 2023. https://med.stanford.edu/survivingcancer/cancers-existential-questions/cancer-will-to-live.html

Salazar, S.M.D.C., Dino, M.J.S., & Macindo, J.R.B. (2023). Social connectedness and health-related quality of life among patients with cancer undergoing chemotherapy: a mixed method approach using structural equation modelling and photo-elicitation. J Clin Nurs. Published online March 9, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.16675

Schmutzler, R. K., Schmitz-Luhn, B., Borisch, B., Devilee, P., Eccles, D., Hall, P., … & Woopen, C. (2022). Risk-adjusted cancer screening and prevention (RiskAP): complementing screening for early disease detection by a learning screening based on risk factors. Breast Care, 17(2), 208-223. https://doi.org/10.1159/000517182

Song, M., & Giovannucci, E. (2016). Preventable incidence and mortality of carcinoma associated with lifestyle factors among white adults in the United States. JAMA Ooncology, 2(9), 1154-1161. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.0843

Spei, M.E., Samoli, E., Bravi, F., et al. (2019). Physical activity in breast cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis on overall and breast cancer survival. Breast, 44,144-152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2019.02.001

Stagl, J.M., Lechner, S.C., Carver, C.S. et al. (2015). A randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavioral stress management in breast cancer: survival and recurrence at 11-year follow-up. Breast Cancer Res Treat, 154, 319–328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-015-3626-6

Stratton, K., Shetty, P., Wallace, R., et al., eds. (2001). Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Assess the Science Base for Tobacco Harm Reduction. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK222369/

Tailor, T.D,, Bell, S., Fendrick, A.M., & Carlos, R.C. (2022) Total and Out-of-Pocket Costs of Procedures After Lung Cancer Screening in a National Commercially Insured Population: Estimating an Episode of Care. J Am Coll Radiol. 19(1 Pt A), 35-46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2021.09.015

Turner, M.C., Andersen, Z.J., Baccarelli, A., Diver, W.R., Gapstur, S.M., Pope, C.A 3rd, Prada, D., Samet, J., Thurston, G., & Cohen, A. (2020). Outdoor air pollution and cancer: An overview of the current evidence and public health recommendations. CA Cancer J Clin, 10.3322/caac.21632. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21632

US Department of Health and Human Services (2014). The Health Consequences of Smoking: 50 Years of Progress. A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: :

US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. https://aahb.org/Resources/Pictures/Meetings/2014-Charleston/PPT%20Presentations/Sunday%20Welcome/Abrams.AAHB.3.13.v1.o.pdf

Van Tulleken, C. (2023). Ultra-processed people. The science behind food that isn’t food. New Yoerk: W.W. Norton & Company. https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/1324036729/ref=ox_sc_act_title_1?smid=ATVPDKIKX0DER&psc=1

TechStress: Building Healthier Computer Habits

Posted: August 30, 2023 Filed under: ADHD, behavior, biofeedback, Breathing/respiration, cognitive behavior therapy, computer, digital devices, education, emotions, ergonomics, Evolutionary perspective, Exercise/movement, health, laptops, Neck and shoulder discomfort, Pain/discomfort, posture, screen fatigue, stress management, Uncategorized, vision, zoom fatigue | Tags: cellphone, fatigue, gaming, mobile devices, screens 2 CommentsBy Erik Peper, PhD, BCB, Richard Harvey, PhD, and Nancy Faass, MSW, MPH

Adapted by the Well Being Journal, 32(4), 30-35. from the book, TechStress: How Technology is Hijacking Our Lives, Strategies for Coping, and Pragmatic Ergonomics by Erik Peper, Richard Harvey, and Nancy Faass.

Every year, millions of office workers in the United States develop occupational injuries from poor computer habits—from carpal tunnel syndrome and tension headaches to repetitive strain injury, such as “mouse shoulder.” You’d think that an office job would be safer than factory work, but the truth is that many of these conditions are associated with a deskbound workstyle.

Back problems are not simply an issue for workers doing physical labor. Currently, the people at greatest risk of injury are those with a desk job earning over $70,000 annually. Globally, computer-related disorders continue to be on the rise. These conditions can affect people of all ages who spend long hours at a computer and digital devices.

In a large survey of high school students, eighty-five percent experienced tension or pain in their neck, shoulders, back, or wrists after working at the computer. We’re just not designed to sit at a computer all day.

Field of Ergonomics

For the past twenty years, teams of researchers all over the world have been evaluating workplace stress and computer injuries—and how to prevent them. As researchers in the fields of holistic health and ergonomics, we observe how people interact with technology. What makes our work unique is that we assess employees not only by interviewing them and observing behaviors, but also by monitoring physical responses.

Specifically, we measure muscle tension and breathing, in the moment, in real-time, while they work. To record shoulder pain, for example, we place small sensors over different muscles and painlessly measure the muscle tension using an EMG (electromyograph)—a device that is employed by physicians, physical therapists, and researchers. Using this device, we can also keep a record of their responses and compare their reactions over time to determine progress.

What we’ve learned is that people get into trouble if their muscles are held in tension for too long. Working at a computer, especially at a stationary desk, most people maintain low-level chronic tension for much of the day. Shallow, rapid breathing is also typical of fine motor tasks that require concentration, like data entry.

Muscle tension and breathing rate usually increase during data entry or typing without our awareness.

When these patterns are paired with psychological pressure due to office politics or job insecurity, the level of tension and the risk of fatigue, inflammation, pain, or injury increase. In most cases, people are totally unaware of the role that tension plays in injury. Of note, the absolute level of tension does not predict injury—rather, it is the absence of periodic rest breaks throughout the day that seems to correlate with future injuries.

Restbreaks

All of life is the alternation between movement and rest, inhaling and exhaling, sleeping and waking. Performing alternating tasks or different types of activities and movement is one way to interrupt the couch potato syndrome—honoring our evolutionary background.

Our research has confirmed what others have observed: that it’s important to be physically active, at least periodically, throughout the day. Alternating activity and rest recreate the pattern of our ancestors’ daily lives. When we alternate sedentary tasks with physical activity, and follow work with relaxation, we function much more efficiently. In short, move your body more.

Better Computer Habits: Alternate Periods of Rest and Activity

As mentioned earlier, our workstyle puts us out of sync with our genetic heritage. Whether hunting and gathering or building and harvesting, our ancestors alternated periods of inactivity with physical tasks that required walking, running, jumping, climbing, digging, lifting, and carrying, to name a few activities. In contrast, today many of us have a workstyle that is so immobile we may not even leave our desk for lunch.

As health researchers, we have had the chance to study workstyles all over the world. Back pain and strain injuries now affect a large proportion of office workers in the US and in high-tech firms worldwide. The vast majority of these jobs are sedentary, so one focus of the research is on how to achieve a more balanced way of working.

A recent study on exercise looked at blood flow to the brain. Researchers Carter and colleagues found that if people sit for four hours on the job, there’s a significant decrease in blood flow to the brain. However, if every thirty or forty minutes they get up and move around for just two minutes, then brain blood flow remains steady. The more often you interrupt sitting with movement, the better.

It may seem obvious that to stay healthy, it’s important to take breaks and be physically active from time to time throughout the day. Alternating activity and rest recreate the pattern of our ancestors’ daily lives. The goal is to alternate sedentary tasks with physical activity and follow work with relaxation. When we keep this type of balance going, most people find that they have more energy, are more productive, and can be more effective.

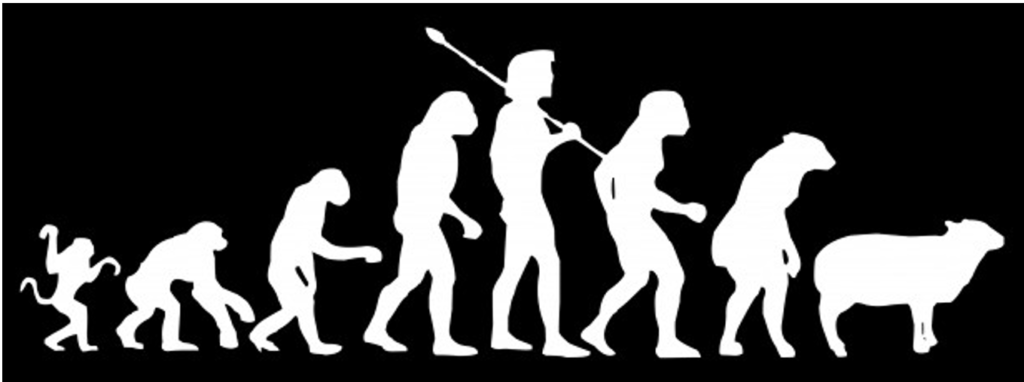

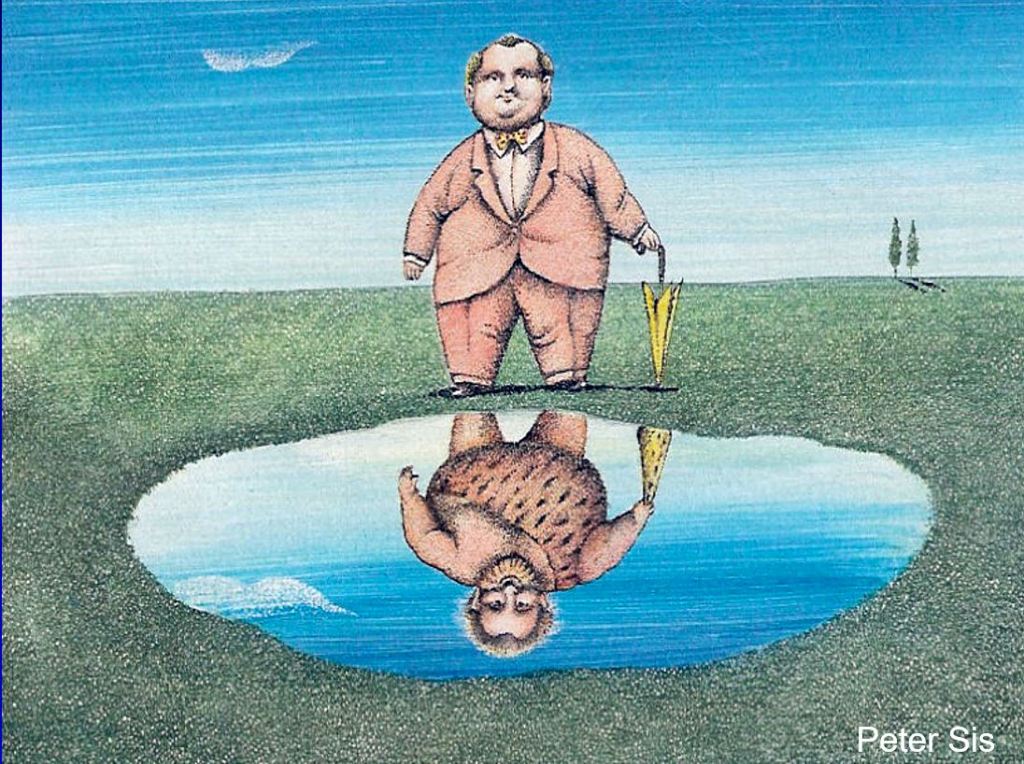

Genetics: We’re Hardwired Like Ancient Hunters

Despite a modern appearance, we carry the genes of our forebearers—for better and for worse. (Art courtesy of Peter Sis). Reproduced from Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Faass (2020). TechStress: How Technology is Hijacking Our Lives, Strategies for Coping, and Pragmatic Ergonomics. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books.

In the modern workplace, most of us find ourselves working indoors, in small office spaces, often sitting at a computer for hours at a time. In fact, the average Westerner spends more than nine hours per day sitting indoors, yet we’re still genetically programmed to be physically active and spend time outside in the sunlight most of the day, like the nomadic hunters and gatherers of forty thousand years ago.

Undeniably, we inherently conserve energy in order to heal and regenerate. This aspect of our genetic makeup also helps burn fewer calories when food is scarce. Hence the propensity for lack of movement and sedentary lifestyle (sitting disease).

In times of famine, the habit of sitting was essential because it reduced calorie expenditure, so it enabled our ancestors to survive. In a prehistoric world with a limited food supply, less movement meant fewer calories burned. Early humans became active when they needed to search for food or shelter. Today, in a world where food and shelter are abundant for most Westerners, there is no intrinsic drive to initiate movement.

It is also true that we have survived as a species by staying active. Chronic sitting is the opposite of our evolutionary pattern in which our ancestors alternated frequent movement while hunting or gathering food with periods of rest. Whether they were hunters or farmers, movement has always been an integral aspect of daily life. In contrast, working at the computer—maintaining static posture for hours on end—can increase fatigue, muscle tension, back strain, and poor circulation, putting us at risk of injury.

Quit a Sedentary Workstyle

Almost everyone is surprised by how quickly tension can build up in a muscle, and how painful it can become. For example, we tend to hover our hands over the keyboard without providing a chance for them to relax. Similarly, we may tighten some of the big muscles of our body, such as bracing or crossing our legs.

What’s needed is a chance to move a little every few minutes—we can achieve this right where we sit by developing the habit of microbreaks. Without regular movement, our muscles can become stiff and uncomfortable. When we don’t take breaks from static muscle tension, our muscles don’t have a chance to regenerate and circulate oxygen and necessary nutrients.

Build a variety of breaks into your workday:

- Vary work tasks

- Take microbreaks (brief breaks of less than thirty seconds)

- Take one-minute stretch breaks

- Fit in a moving break

Varying Work Tasks

You can boost physical activity at work by intentionally leaving your phone on the other side of the desk, situating the printer across the room, or using a sit-stand desk for part of the day. Even a few minutes away from the desk makes a difference, whether you are hand delivering documents, taking the long way to the bathroom, or pacing the room while on a call.

When you alternate the types of tasks and movement you do, using a different set of muscles, this interrupts the contractions of muscle fibers and allows them to relax and regenerate. Try any of these strategies:

- Alternate computer work with other activities, such as offering to do a coffee run

- Schedule walking meetings with coworkers

- Vary keyboarding and hand movements

Ultimately, vary your activities and movements as much as possible. By changing your posture and making sure you move, you’ll find that your circulation and your energy improve, and you’ll experience fewer aches and pains. In a short time, it usually becomes second nature to vary your activities throughout the day.

Experience It: “Mouse Shoulder” Test

You can test this simple mousing exercise at the computer or as a simulation. If you’re at the computer, sit erect with your hand on the mouse next to the keyboard. To simulate the exercise, sit with erect posture as if you were in front of your computer and hold a small object you can use to imitate mousing.

With the mouse (or a sham mouse), simulate drawing the letters of your name and your street address, right to left. Be sure each letter is very small (less than half an inch in height). After drawing each letter, click the mouse.

As part of the exercise, draw the letters and numbers as quickly as possible for ten to fifteen seconds. What did you observe? In almost all cases, you may note that you tightened your mousing shoulder and your neck, stiffened your trunk, and held your breath. All this occurred without awareness while performing the task. Over time, this type of muscle tension can contribute to discomfort, soreness, pain, or eventual injury.

Microbreaks

If you’ve developed an injury—or have chronic aches and pains—you’ll probably find split-second microbreaks invaluable. A microbreak means taking brief periods of time that last just a few seconds to relax the tension in your wrists, shoulders, and neck.

For example, when typing, simply letting your wrists drop to your lap for a few seconds will allow the circulation to return fully to help regenerate the muscles. The goal is to develop a habit that is part of your routine and becomes automatic, like driving a car. To make the habit of microbreaks practical, think about how you can build the breaks into your workstyle. That could mean a brief pause after you’ve completed a task, entered a column of data, or before starting typing out an assignment.

For frequent microbreaks, you don’t even need to get up—just drop your hands in your lap or shake them out, move your shoulders, and then resume work. Any type of shaking or wiggling movement is good for your circulation and kind of fun.

In general, a microbreak may be defined as lasting one to thirty seconds. A minibreak may last roughly thirty seconds to a few minutes, and longer large-movement breaks are usually greater than a few minutes. Popular microbreaks:

- Take a few deep breaths

- Pause to take a sip of water

- Rest your hands in your lap

- Stretch

- Let your arms drop to your sides

- Shake out your hands (wrists and fingers)

- Perform a quick shoulder or neck roll

Often, we don’t realize how much tension we’ve been carrying until we become more mindful of it. We can raise our awareness of excess tension—this is a learned skill—and train ourselves to let go of excess muscle tension. As we increase our awareness, we’re able to develop a new, more dynamic workstyle that better fits our goals and schedule.

One-Minute Stretch Breaks

We all benefit from a brief break, even with the best of posture (left). One approach is to totally release your muscles (middle). That release can be paired with a series of brief stretches (right). Reproduced from Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Faass (2020). TechStress: How Technology is Hijacking Our Lives, Strategies for Coping, and Pragmatic Ergonomics. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books.

The typical mini-stretch break lasts from thirty seconds to a few minutes, and ideally you want to take them several times per hour. Similar to microbreaks, mini-stretch breaks are especially important for people with an injury or those at risk of injury. Taking breaks is vital, especially if you have symptoms related to computer stress or whenever you’re working long hours at a sedentary job. To take a stretch break:

Begin with a big stretch, for example, by reaching high over your head then drop your hands in your lap or to your sides.

Look away from the monitor, staring at near and far objects, and blink several times. Straighten your back and stretch your entire backbone by lifting your head and neck gently, as if there were an invisible string attached to the crown of your head.

Stretch your mind and body. Sitting with your back straight and both feet flat on the floor, close your eyes and listen to the sounds around you, including the fan on the computer, footsteps in the hallway, or the sounds in the street.

Breathe in and out over ten seconds (breathe in for four or five seconds and breathe out for five or six seconds), making the exhale slightly longer than the inhale. Feel your jaw, mouth, and tongue muscles relax. Feel the back and bottom of the chair as your body breathes all around you. Envision someone in your mind’s eye who is kind and reassuring, who makes you feel safe and loved, and who can bring a smile to your face inwardly or outwardly.

Do a wiggling movement. When you take a one-minute break, wiggling exercises are fast and easy, and especially good for muscle tension or wrist pain. Wiggle all over—it feels good, and it’s also a great way to improve circulation.

Building Exercise and Movement into Every Day

Studies show that you get more benefit from exercising ten to twenty minutes, three times a day, than from exercising for thirty to sixty minutes once a day. The implication is that doing physical activities for even a few minutes can make a big difference.

Dunstan and colleagues have found that standing up three times an hour and then walking for just two minutes reduced blood sugar and insulin spikes by twenty-five percent.Fit in a Moving Break

Fit in a Moving Break

Once we become conscious of muscle tension, we may be able to reverse it simply by stepping away from the desk for a few minutes, and also by taking brief breaks more often. Explore ways to walk in the morning, during lunch break, or right after work. Ideally, you also want to get up and move around for about five minutes every hour.

Ultimately, research makes it clear that intermittent movement, such as brief, frequent stretching throughout the day or using the stairs rather than elevator, is more beneficial than cramming in a couple of hours at the gym on the weekend. This explains why small changes can have a big impact—it’s simply a matter of reminding yourself that it’s worth the effort.

Workstation Tips

Your ability to see the display and read the screen is key to reducing neck and eye strain. Here are a few strategic factors to remember:

Monitor height: Adjust the height of your monitor so the top is at eyebrow level, so you can look straight ahead at the screen.

Keyboard height: The keyboard height should be set so that your upper arms hang straight down while your elbows are bent at a 90-degree angle (like the letter L) with your forearms and wrists held horizontally.

Typeface and font size: For email, word processing, or web content, consider using a sans serif typeface. Fonts that have fewer curved lines and flourishes (serifs) tend to be more readable on screen.

Checking your vision: Many adults benefit from computer glasses to see the screen more clearly. Generally, we do not recommend reading glasses, bifocals, trifocals, and progressive lenses as they tend to allow clear vision at only one focal length. To see through the near-distance correction of the lens requires you to tilt your head back. Although progressive lenses allow you to see both close up and at a distance, the segment of the lens for each focal length is usually too narrow for working at the computer.

Wearing progressive lenses requires you to hold your head in a fixed position to be in focus. Yet you may be totally unaware that you are adapting your eye and head movements to sustain your focus. When that is the case, most people find that special computer glasses are a good solution.

Consider computer glasses if you must either bring your nose to the screen to read the text, wear reading glasses and find that their focal length is inappropriate for the monitor distance, wear bi- or trifocal glasses, or are older than forty.

Computer glasses correct for the appropriate focal distance to the computer. Typically, monitor distance is about twenty-three to twenty-eight inches, whereas reading glasses correct for a focal length of about fifteen inches. To determine your individual, specific focal length, ask a coworker to measure the distance from the monitor to your eyes. Provide this personal focal distance at the eye exam with your optometrist or ophthalmologist and request that your computer glasses be optimized for that distance.

Remembering to blink: As we focus on the screen, our blinking rate is significantly reduced. Develop the habit of blinking periodically: at the end of a paragraph, for example, or when sending an email.

Resting your eyes: Throughout the day, pause and focus on the far distance to relax your eyes. When looking at the screen, your eyes converge, which can cause eyestrain. Each time you look away and refocus, that allows your eyes to relax. It’s especially soothing to look at green objects such as a tree that can be seen through a window.

Minimizing glare: If the room is lit with artificial light, there may be glare from your light source if the light is right in front of you or right behind you, causing reflection on your screen. Reflection problems are minimized when light sources are at a 90-degree angle to the monitor (with the light coming from the side). The worst situations occur when the light source is either behind or in front of you.

An easy test is to turn off your monitor and look for reflections on the screen. Everything that you see on the monitor when it’s turned off is there when you’re working at the monitor. If there are bright reflections, they will interfere with your vision. Once you’ve identified the source of the glare, change the location of the reflected objects or light sources, or change the location of the monitor.