Reduce the risk for colds and flu and superb science podcasts

Posted: January 24, 2024 Filed under: attention, behavior, education, Evolutionary perspective, Exercise/movement, healing, health, Nutrition/diet, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized, vision | Tags: colds, darkness, flu, influenza, light 1 Comment

What can we do to reduce the risk of catching a cold or the flu? It is very challenging to make sense out of all the recommendations found on internet and the many different media site such as X(Twitter), Facebook, Instagram, or TikTok. The following podcasts are great sources that examine different topics that can affect health. They are in-depth presentations with superb scientific reasoning.

Huberman Lab podcasts discusses science and science based tools for everyday life. https://www.hubermanlab.com/podcast. Select your episode and they are great to listen to on your cellphone.

THE PODCAST episode, How to prevent and treat cold and flu, is outstanding. Skip the long sponsor introductdion and start listening at the 6 minute point. In this podcast, Professor Andrew Huberman describes behavior, nutrition and supplementation-based tools supported by peer-reviewed research to enhance immune system function and better combat colds and flu. I also dispel common myths about how the cold and flu are transmitted and when you and those around you are contagious. I explain if common preventatives and treatments such as vitamin C, zinc, vitamin D and echinacea work. I also highlight other compounds known to reduce contracting and duration of colds and flu. I discuss how to use exercise and sauna to bolster the immune response. This episode will help listeners understand how to reduce the chances of catching a cold or flu and help people recover more quickly from and prevent the spread of colds and flu.

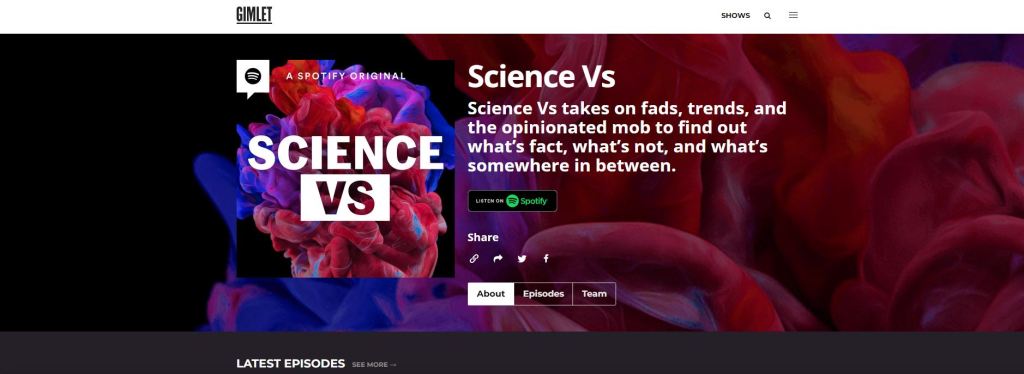

PODCAST, ScienceVS, is an outstanding podcast series that takes on fads, trends, and opinionated mob to find out what’s fact, what’s not, and what’s somewhere in between. Select your episode and listen.

Link: https://gimletmedia.com/shows/science-vs/episodes#show-tab-picker

PODCAST episode, The Journal club podcast and Youtube, presentation from Huberman Lab is a example of outstanding scientific reasoning. In this presentation, Professor Andrew Huberman and Dr. Peter Attia (author of Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity) discuss two peer-reviewed scientific papers in-depth. The first discussion explores the role of bright light exposure during the day and dark exposure during the night and its relationship to mental health. The second paper explores a novel class of immunotherapy treatments to combat cancer.

Rethink the monies spent on cancer screening tests

Posted: November 24, 2023 Filed under: behavior, cancer, Evolutionary perspective, healing, health, Nutrition/diet, self-healing | Tags: breast canceer, Cancer screening, environmental toxins, Life style, mammography, organic foods Leave a commentErik Peper, PhD and Richard Harvey, PhD

Cancer screening tests are based upon the rational that early detection of fatal cancers enables earlier and more effective treatments (Kowalski, 2021), however, there is some controversy. Early screening may increase the risk of over diagnosis, treating false positives (people who did not have the cancer but the test indicates they have cancer) and potentially fatal treatment of cancers that would never progress to increase morbidity or mortality (Kowalski, 2021).

Today about $40 billion spent on colon cancer screening, $15 billion spent on breast cancer screening, and $4 billion spent on prostate cancer screening annually (CSPH, 2021). A question is raised whether the billions and billions of dollars spent on screening asymptomatic participants would be more wisely spent on promoting and supporting life style changes that reduce cancer risks and actually extend life span? That cancer screening is expensive does not mean no one should be screened. Instead, the argument is that the majority of healthcare dollars could be spent on health promotion practices and reserving screening for those people who are at highest risk for developing cancers.

What is the evidence that screening prolongs life?

Cancer screening tests appear correlated with preventing deaths since deaths due to cancers in the USA have decreased by about 28% from 1999 to 2020 (CDC, 2023a). Although cancer causes many of the deaths in the USA, overall life expectancy has increased by less than 1% from 1999 to 2020. If cancer screening were more effective, the life expectancy should have increased more because cancer is the second leading cause of death (CDC, 2023b). Consider also that deaths due to cancers may be coincident and or comorbid with other circumstances. For example, during the last four years, overall life expectancy in the USA has precipitously declined in part due to other causes of death such as the COVID pandemic and opioid overdose epidemic (Lewis, 2022). Decline in life expectancy in the USA has many contributing factors, including the ‘harms’ associated with cancer screening procedures. For example, perforations during colon cancer screening can lead to internal bleeding, or complications related to surgeries, radiotherapies or chemotherapies. Bretthauer et al., (2023) commented: “A cancer screening test may reduce cancer-specific mortality but fail to increase longevity if the harms for some individuals outweigh the benefits for others or if cancer-specific deaths are replaced by deaths from competing cause” (p. 1197).

Bretthauer et al. (2023) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of 18 long-term randomized clinical trials involving 2.1 million Individuals with more than nine years of follow-up reporting on all-cause mortality. They reported that“…this meta-analysis suggest that current evidence does not substantiate the claim that common cancer screening tests save lives by extending lifetime, except possibly for colorectal cancer screening with sigmoidoscopy.”

Following is a summary of Bretthauer et al. (2023) findings:

- The only cancer screening with a significant lifetime gain (approximately 3 months) was sigmoidoscopy.

- There was no significant difference between harms of screening and benefits of screening for:

- mammography

- prostate cancer screening

- FOBT (fecal occult blood test) screening every year or every other year

- lung cancer screening Pap test cytology for cervical cancer screening, no randomized clinical trials with cancer-specific or all-cause mortality end points and long term follow-up were identified.

Potential for loss or harm (e.g., iatrogenic and nosocomial) versus potential for benefit and extended life

More than 35 years ago a significant decrease in breast cancer mortality was observed after mammography was implemented. The correlation suggested a causal relationship that screening reduced mortality (Fracheboud, 2004). This correlation made logical sense since the breast cancer screening test identified cancers early which could then be treated and thereby would result in a decrease in mortality.

How much money is spent on screening that may correlate with unintended harms?

The annual total expenditure for cancer screening is estimated to be between $40-$50 billion annually (CSPH, 2021). Below are some of the estimated expenditures for common tests other than colorectal cancer screening, which arguably is costly; however, has potential benefits that outweigh potential harms.

- $10.37-13.94 billion for mammography to screen 50% of eligible women (Badal et al, 2023).

- $2-4 billion for prostate cancer (Ma et al., 2014)

- $1-2 billion for lung cancer (Taylor et al., 2022)

What is the correlation between initiation of mammography and decrease in breast cancer mortality?

The conclusion that mammography reduced breast cancer mortality was based upon studies without control groups; however, this relationship could be causal or synchronistic. The ambiguity of correlation or causation was resolved with the use of natural experimental control groups. Some European countries began screening 10 years earlier than other countries. Using statistical techniques such as propensity score matching when comparing the data from countries that initiated mammography screening early (Netherlands, Sweden and Northern Ireland) to countries that started screening 10 year later (Belgium, Norway and Republic of Ireland), the effectiveness of screening could be compared.

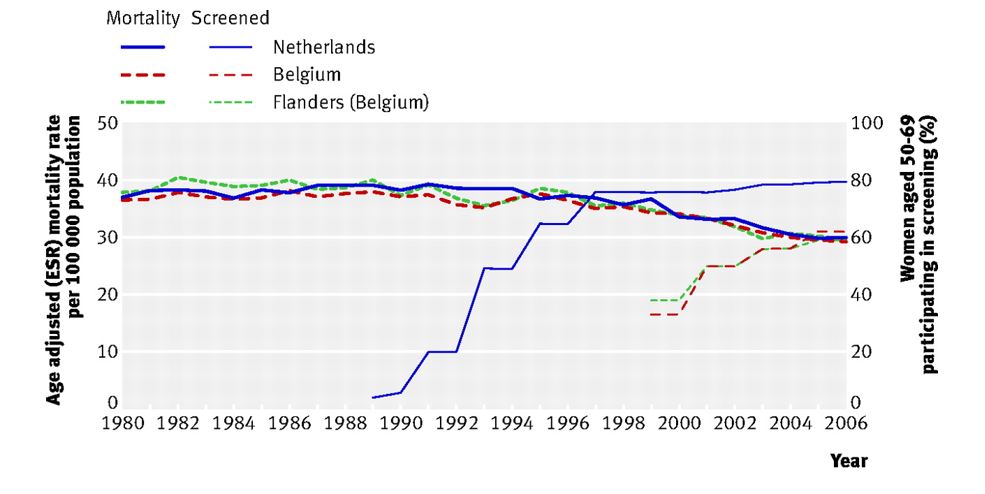

The comparisons showed no difference in the decrease of breast cancer mortality in countries that initiated breast cancer screening early or late. For example, there was no difference in the decrease of breast cancer mortality rates of women who lived in the Netherlands that started screening early versus those who lived in Belgium that began screening 10 years later, as is shown Figure 1 (Autier et al, 2011).

Figure 1. No difference in age adjust breast cancer mortality between the two adjacent countries even though breast cancer screening began ten years earlier in the Netherlands than in Belgium (graph reproduced from Autier et al, 2011).

The observations are similar when comparing neighboring countries: Sweden (early screening) to Norway (late screening) as well as Northern Ireland, UK (early screening) compared to the Republic of Ireland (late screening). The systematic comparisons showed that screening did not account for the decrease in breast cancer mortality. To what extent could the decrease in mortality be related to other factors such as better prenatal and early childhood diet and life style, improved nutrition, reduction in environmental pollutants, and other unidentified life style and environmental factors which improve immune competence?

A simplistic model to reduce the risk of cancers is described in the following equation (Gorter & Peper, 2011).

Cancer risk can be reduced, arguably by influencing risk factors that contribute to cancers as well as increasing factors to enhance immune competence. In the simple model above, ‘Cancer burden’ refers to the set of exposures that increase the odds of cancer formations. Categories include exposures to oncoviruses, environmental exposures (e.g., ionizing radiation, carcinogenic chemicals) as well as genetic (e.g., chromosomal aberrations, replication errors) and epigenetic factors (e.g., lifestyle categories related to eating, exercising, sleeping, and relaxing). In the model above, ‘Immune competence’ refers to a set of categories of immune functioning related to DNA repair, orderly cell death (i.e., processes of apoptosis), expected autophagy, as well as ‘metabolic rewiring,’ also called cellular energetics, that would allow the body to be able to reduce manage cancers from progressing (Fouad & Aanei, 2017) .

How do we examine the cancer burden/immune competence relationship?

Schmutzler et al., (2022) have suggested personalized and precision-medicine risk-adjusted cancer screening incorporating “… high-throughput “multi-omics” technologies comprising, among others, genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics, which have led to the discovery of new molecular risk factors that seem to interact with each other and with non-genetic risk factors in a multiplicative manner.” The argument is that ‘profit-centered’ medicine could incorporate ‘multi-omics’ into risk-adjusted cancer screening as a way to reduce potential loss or harm due to other cancer screening procedures. Rather than simply screening for cancers using currently invasive or toxic procedures which may do more harm than good, consider more nuanced screening tests aimed at the so-called ‘hallmarks of cancer?’ For example, Hanahan (2022) suggests some technical targets for the multi-omics technologies. The following are some of the precision screening tests possible topersonalized medicine of 14 factors or processes related to:

- cells evading growth suppression

- non-mutational epigenetic reprogramming

- avoiding immune destruction

- enabling replicative immortality

- tumor-promoting inflammation

- polymorphic microbiomes

- activating invasion and metastasis

- inducing or accessing vasculature formation/angiogenesis

- cellular senescence

- genome instability and mutation

- resisting cell death

- deregulating cellular metabolism

- unlocking phenotypic plasticity

- sustaining proliferative signaling

Of the listed categories above, ‘phenotypic plasticity’ (cf. Feinberg, 2007; Gupta et al., 2019) suggests that lifestyle behaviors and environmental exposures play a role in cancer progression and regression.

Lifestyle and environmental factors can contribute to the development of cancers.

The 2008-2009 report from the President’s Cancer Panel appraised the National Cancer Program in accordance with the National Cancer Act of 1971 stated (Reuben, 2010):

“We have grossly underestimated the link between environmental toxins, plastics, chemicals, and cancer risk. It is estimated that 70 percent of all cancers were related to diet and environment “

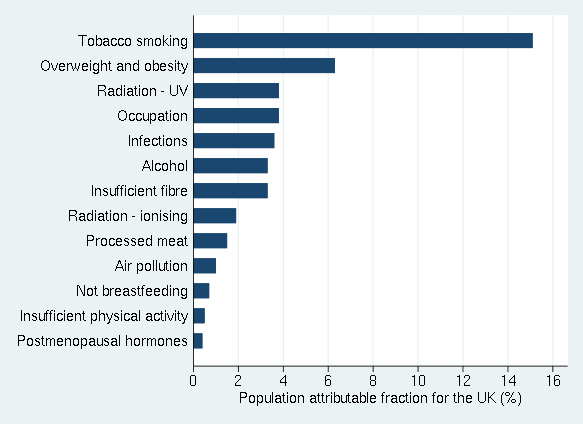

Multiple research studies have shown that a healthy life style pattern is associated with decreased cancer risks and increased longevity. Lifestyle factors that have been documented to increase cancer risks in the United Kingdom (UK) as shown in figure 2.

Figure 2. Percentages of cancer cases in the UK attributable to different exposures. Adapted from Brown et al., 2018 and reproduced by permission from Key et al., 2020.

Similar findings have been reported by Song et al. (2016) from the long term follow-up of 126901 adult health care professionals. People who never smoked, drank no alcohol or moderate alcohol (< 1 drink/d for women; < 2 drinks/d for men}, had a body-mass index (BMI) of at least 18.t but lower than 27.5, did weekly aerobic physical activity of at least 75 vigorous-intensity minutes or 150 150 moderate-intensity minutes compared to those who smoked, drank, had high BMI and did not exercise had nearly half the cancer death rate. Song et al (2016) concludes:

“…about 20% to 40% of carcinoma cases and about half of carcinoma deaths can be potentially prevented through lifestyle modification. Not surprisingly, these figures increased to 40% to 70% when assessed with regard to the population of US whites which has a much worse lifestyle pattern than other cohorts. Notably, approximately 80% to 90% of lung cancer deaths can be avoided if Americans adopted the lifestyle of the low-risk group, mainly by quitting smoking. For other cancers, a range of 10% to 70% of deaths can be prevented. These results provide strong support for the importance of environmental factors in cancer risk and reinforce the enormous potential of primary prevention for cancer control.”

Said another way, primary prevention should remain a priority for cancer control.

Given that many cancers are related to diet, environment and lifestyle, it is estimated that 50% of all cancers and cancer deaths could be prevented by modifying personal behavior. Thus, the monies spent on screening or even developing new treatments could better be spent on prevention along with implementing programs that promote a healthier environment, diet and personal behavior (AACR, 2011).

What can be done? Addressing systems not symptoms

From a ‘systems perspective,’ the first step is to reduce the cancer burden and carcinogenic agents that occur in our environment such environmental pollution (Turner et al., 2022). In many cases, governmental regulations that reduce cancer risk factors have been weakened, delayed, and contested for years through industry’s lobbying. It often takes more than 30 years after risk factors have been observed and documented before government regulations are successfully implemented, as exemplified in the battle over tobacco or, air pollution regulations related to particulates from burning fossil fuels (Stratton et al, 2001).

Sadly, we cannot depend upon governments or industries to implement regulations known to reduce cancer risks. More within our control is implementing lifestyle changes that enhance immune competence and promote health.

Implement a healthy life style that enhances immune competence and, supports health and well-being

Paraphrasing a trope of what some physicians may state: ‘Take two pills, and call me in the morning. Oh, and eat well, exercise, and get good rest.’ Broadly stated, the following are some controllable lifestyle behaviors that can decrease cancer risks and promotes health. Implementing environmental and lifestyle changes are very challenging because they are highly related to socio economic factors, cultural factors, industry push for profits over health, and self-care challenges since there are no immediate results experienced by behavior and lifestyle changes.

In many cases, the effects of harmful life-style and environment factors are only observed twenty or more years later (e.g., diabetes, lung cancer, cirrhosis of the liver). The individual does not experience immediate benefits of lifestyle changes thus it is more challenging to know that your healthy life style has an effect. The process is even more complex because in most cases it is not a single factor but the interaction of multiple factors (genetics, lifestyle, and environment). The complexity of causality so often conflicts with the simplistic research studies to identify only one isolated risk factor. Instead of waiting for the definitive governmental guidelines and regulations, adopt a ‘precautionary principle’ which means do not take an action when there is uncertainty about its potential harm (Goldstein, 2001). Do not wait for screening; instead, take charge of your health and implement as many of the following behaviors and strategies to enhance immune competence and thereby reduce cancer risks.

Eat organic foods, especially vegetable and fruits.

Many studies have suggested that eating organic foods and in particular more fruits and vegetable such as a Mediterranean diet is associated with increased health and longevity. Similarly, people who eat do not eat highly-processed or ultra-processed foods have better health status (Van Tulleken, 2023). For example, In the large prospective study of 68, 946 participants, adults who consumed the most organic fruits, vegetables, dairy products, meat and other foods had 25% fewer cancers when compared with adults who never ate organic food (Baudry et al., 2018; Rabin, 2018). Similarly, many studies have reported that those who adhere consistently to a Mediterranean diet have a significantly lower incidence of chronic diseases (such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, etc.) and cancers compared to those who do not adhere to a Mediterranean diet (Mentella et al., 2019).

Reduce environmental pollution exposure

Air pollution and the exposure to airborne carcinogens are a significant risk factor for cancers as illustrated by the increased cancer rates among smokers. In the USA, the reduction of smoking has significantly decreased the lung cancer deaths (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2014).

Increase movement and exercise

Many studies have documented that people who exercise regularly and are otherwise non–sedentary but are active their entire lives have the lowest risk for breast cancers and colon cancers. Women who exercise 3 hours a week or more have a 30-40% lower risk of developing breast cancer (NIH NCI, 2023). The NIH National Cancer Institute summary concludes that exercises also significantly benefited the following cancer survivors (NIH NCI, 2023):

- Breast cancer: In a 2019 systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies, breast cancer survivors who were the most physically active had a 42% lower risk of death from any cause and a 40% lower risk of death from breast cancer than those who were the least physically active (Spei et al, 2019).

- Colorectal cancer: Evidence from multiple epidemiologic studies suggests that physical activity after a colorectal cancer diagnosis is associated with a 30% lower risk of death from colorectal cancer and a 38% lower risk of death from any cause (Patel et al., 2019).

- Prostate cancer: Limited evidence from a few epidemiologic studies suggests that physical activity after a prostate cancer diagnosis is associated with a 33% lower risk of death from prostate cancer and a 45% lower risk of death from any cause ((Patel et al., 2019).

- Implement stress management.

Chronic stress may reduce immune competence and increase the risk of cancers as well as hinders healing from cancer treatments (Dai et al., 2020). The results of numerous studies have shown that implementing stress management spractices uch as Cognitive-behavioral stress management (CBSM) improves mood and lowers distress during treatment and, is also associated with longer survival compared to control groups in the 8-15 year follow up (Stagl et al., 2015).

Respect your biological rhythm.

The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) reports that, when the human circadian clock is disrupted, the likelihood of developing cancers, including lung cancers, intestinal cancers, and breast cancers, dramatically increases (Huang, et al., 2023). Go to bed at the same time and, have about 8 hours of sleep. As much as possible avoid night shifts at work along with frequent jet lag as that highly disrupts the circadian rhythm.

Increase social connections and be part of a social community

Absence of social support, feeling lonely and socially isolated tends reduces immune competence and increases cancer mortality risk while having more social support satisfaction is associated with lower mortality risks (Salazaor et al., 2023; Boen et al., 2018). Meta-analysis of 148 studies (308,849 participants) found that that on the average there is a 50% increased likelihood of survival for participants with stronger social relationships (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010).

Live a life with meaning and purpose

Having meaning and purpose make each moment worth living and may contribute to improving immune function and possible cancer survival (LeShan, 1994; Rosenbaum & Rosenbaum, 2023).

Summary

The research suggests that cancer screening does not extend life span unless specifically performed for certain diagnostic purposes or, with individuals who are at high risk of developing cancers (e.g., have a genetic predisposition). Implementing self-care health behaviors that have been identified to promote health and increase lifespan. Implementing health behaviors is challenging since there is limited governmental and corporate support. Thus, take charge and implement a holistic self-care lifestyle that reduces cancer risk factors and supports health.

See also the following blogs:

References

AACR. (2011). AACR Cancer Progress Report 2011. American Association for Cancer Research. http://www.aacr.org/Uploads/DocumentRepository/2011CPR/2011_AACR_CPR_Text_web.pdf

American Cancer Society. (2021). History of ACS Recommendations for the Early Detection of Cancer in People Without Symptoms. Accessed November 11, 2023. https://www.cancer.org/health-care-professionals/american-cancer-society-prevention-early-detection-guidelines/overview/chronological-history-of-acs-recommendations.html

Autier, P., Boniol, M., Gavin, A,, & Vatten, L.J. (2011) Breast cancer mortality in neighbouring European countries with different levels of screening but similar access to treatment: trend analysis of WHO mortality database. BMJ. 343, d4411. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d4411

Badal., K., Staib, J., Tice,J., Kim, M-O., Eklund, M., DaCosta Byfield, S., Catlett,K., Wilson,L., et al, (2023). Cost of breast cancer screening in the USA: Comparison of current practice, advocated guidelines, and a personalized risk-based approach. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 41: 16_suppl, 3 18917 :16_suppl, e18917. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2023.41.16_suppl.e18917

Baudry, J., Assmann, K.E., Touvier, M., et al. (2018). Association of Frequency of Organic Food Consumption With Cancer Risk: Findings From the NutriNet-Santé Prospective Cohort Study. JAMA Intern Med, 178(12), 1597–1606. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4357

Boen, C.E., Barrow, D..A, Bensen, J.T., Farnan, L., Gerstel, A., Hendrix, L.H., Yang, Y.C. (2018). Social Relationships, Inflammation, and Cancer Survival. Cancer. Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 27(5), 541-549. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-0836

Bretthauer M, Wieszczy P, Løberg M, et al. (2023). Estimated Lifetime Gained With Cancer Screening Tests: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA Intern Med. 183(11),1196–1203. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.3798Brown, K.F., Rumgay, H., Dunlop, C. et al. (2018). The fraction of cancer attributable to modifiable risk factors in England, Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland, and the United Kingdom in 2015. Br J Cancer, 118, 1130–1141. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-018-0029-6

CDC. (2023a). U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group. U.S. Cancer Statistics Data Visualizations Tool, based on 2022 submission data (1999-2020): U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute; released in November 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/dataviz

CDC. (2023b). Leading Causes of Death. National Center for health statistics, Centers for disease control and prevention. Accessed November 20, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm

CSPH. (2021). Estimating annual expenditures for cancer screening in the United States. Center for Surgery and Public Health. Assessed November 14, 2023. https://csph.brighamandwomens.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Estimating-Annual-Expenditures-for-Cancer-Screening-in-the-United-States.pdf

Dai, S., Mo, Y., Wang, Y., Xiang, B., Liao, Q., Zhou, M., Li, X., Li, Y., Xiong. W., Li, G., Guo, C., & Zeng, Z. (2020). Chronic Stress Promotes Cancer Development. Front Oncol. 10, 1492. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.01492

Feinberg, A. P. (2007). Phenotypic plasticity and the epigenetics of human disease. Nature, 447(7143), 433-440. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05919

Fouad, Y. A., & Aanei, C. (2017). Revisiting the hallmarks of cancer. American journal of cancer research, 7(5), 1016. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28560055/

Fracheboud, J. et al. (2004). Decreased rates of advanced breast cancer due to mammography screening in The Netherlands, British Journal of Cancer (2004) 91, 861–867. https://doi,org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6602075

Goldstein, B.D. (2001). The precautionary principle also applies to public health actions. Am J Public Health, 91(9),1358-61. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.91.9.1358

Gorter, R. & Peper, E. (2011). Fighting Cancer-A None Toxic Approach to Treatment. Berkeley: North Atlantic/New York: Random House. https://www.amazon.com/Fighting-Cancer-Nontoxic-Approach-Treatment/dp/1583942483

Gupta, P. B., Pastushenko, I., Skibinski, A., Blanpain, C., & Kuperwasser, C. (2019). Phenotypic plasticity: driver of cancer initiation, progression, and therapy resistance. Cell Stem Cell, 24(1), 65-78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2018.11.011

Hanahan, Douglas. (2022): Hallmarks of cancer: new dimensions. Cancer discovery, 12(1), 31-46. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-1059

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T.B., & Layton, J.B. (2010). Social Relationships and Mortality Risk: A Meta-analytic Review, PLoS Med 7(7), e1000316. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316

Huang, C., Zhang, C,, Cao, Y., Li, J., & Bi, F. (2023). Major roles of the circadian clock in cancer. Cancer Biol Med, 20(1):1–24. https://doi.org/10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2022.0474

Kalaf, J.M. (2014). Mammography: a history of success and scientific enthusiasm. Radiol Bras. 47(4):VII-VIII. https://doi.org/10.1590/0100-3984.2014.47.4e2

Key TJ, Bradbury KE, Perez-Cornago A, Sinha R, Tsilidis KK, Tsugane S. Diet, nutrition, and cancer risk: what do we know and what is the way forward? BMJ. 2020 Mar 5;368:m511. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m511

Kowalski, A.E. (2021). Mammograms and mortality: How has the evidence evolved? J Econ Perspect, 35(2), 119-140. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.35.2.119

LeShan, L. (1994). Cancer as a turning point. New York: Plume. https://www.amazon.com/Cancer-As-Turning-Point-Professionals/dp/0452271371

Lewis, T. (2022). The U.S. just lost 26 years’ worth of progress on life expectancy. Scientific American. October 17, 2022. Accessed November 11, 2023. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-u-s-just-lost-26-years-worth-of-progress-on-life-expectancy/

Ma, X., Wang, R., Long, J.B., Ross, J.S., Soulos, P.R., Yu, J.B., Makarov, D.V., Gold, H.T. and Gross, C.P. (2014), The cost implications of prostate cancer screening in the Medicare population. Cancer, 120: 96-102. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28373

Mentella, M.C., Scaldaferri, F., Ricci, C., Gasbarrini, A., & Miggiano, G.A.D. (2019). Cancer and Mediterranean Diet: A Review. Nutrients,11(9):2059. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11092059

NIH NCI (2023). Physical Activity and Cancer. National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute. Accessed November 18, 2023. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/obesity/physical-activity-fact-sheet

Patel, A,V., Friedenreich, C.M., Moore, S.C, et al. (2019). American College of Sports Medicine Roundtable Report on physical activity, sedentary behavior, and cancer prevention and control. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 51(11), 2391-2402. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000002117

Rabin, R.C. (2018). Can eating organic food lower your cancer risk? The New York Times. Oct 23, 2018. Accessed November 17, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/23/well/eat/can-eating-organic-food-lower-your-cancer-risk.html

Reuben, S.H. (2010). Reducing environmental cancer risk – What We Can Do Now. The President’s Cancer Panel Report. Washington, D.C: U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. https://deainfo.nci.nih.gov/advisory/pcp/annualReports/pcp08-09rpt/PCP_Report_08-09_508.pdf

Rosenbaum, E. H. & Rosenbaum, I.R. (2023) The Will to Live. Stanford Center for Integrative Medicine. Surviving Cancer. Accessed November 23, 2023. https://med.stanford.edu/survivingcancer/cancers-existential-questions/cancer-will-to-live.html

Salazar, S.M.D.C., Dino, M.J.S., & Macindo, J.R.B. (2023). Social connectedness and health-related quality of life among patients with cancer undergoing chemotherapy: a mixed method approach using structural equation modelling and photo-elicitation. J Clin Nurs. Published online March 9, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.16675

Schmutzler, R. K., Schmitz-Luhn, B., Borisch, B., Devilee, P., Eccles, D., Hall, P., … & Woopen, C. (2022). Risk-adjusted cancer screening and prevention (RiskAP): complementing screening for early disease detection by a learning screening based on risk factors. Breast Care, 17(2), 208-223. https://doi.org/10.1159/000517182

Song, M., & Giovannucci, E. (2016). Preventable incidence and mortality of carcinoma associated with lifestyle factors among white adults in the United States. JAMA Ooncology, 2(9), 1154-1161. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.0843

Spei, M.E., Samoli, E., Bravi, F., et al. (2019). Physical activity in breast cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis on overall and breast cancer survival. Breast, 44,144-152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2019.02.001

Stagl, J.M., Lechner, S.C., Carver, C.S. et al. (2015). A randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavioral stress management in breast cancer: survival and recurrence at 11-year follow-up. Breast Cancer Res Treat, 154, 319–328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-015-3626-6

Stratton, K., Shetty, P., Wallace, R., et al., eds. (2001). Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Assess the Science Base for Tobacco Harm Reduction. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK222369/

Tailor, T.D,, Bell, S., Fendrick, A.M., & Carlos, R.C. (2022) Total and Out-of-Pocket Costs of Procedures After Lung Cancer Screening in a National Commercially Insured Population: Estimating an Episode of Care. J Am Coll Radiol. 19(1 Pt A), 35-46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2021.09.015

Turner, M.C., Andersen, Z.J., Baccarelli, A., Diver, W.R., Gapstur, S.M., Pope, C.A 3rd, Prada, D., Samet, J., Thurston, G., & Cohen, A. (2020). Outdoor air pollution and cancer: An overview of the current evidence and public health recommendations. CA Cancer J Clin, 10.3322/caac.21632. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21632

US Department of Health and Human Services (2014). The Health Consequences of Smoking: 50 Years of Progress. A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: :

US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. https://aahb.org/Resources/Pictures/Meetings/2014-Charleston/PPT%20Presentations/Sunday%20Welcome/Abrams.AAHB.3.13.v1.o.pdf

Van Tulleken, C. (2023). Ultra-processed people. The science behind food that isn’t food. New Yoerk: W.W. Norton & Company. https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/1324036729/ref=ox_sc_act_title_1?smid=ATVPDKIKX0DER&psc=1

Are food companies responsible for the epidemic in diabetes, cancer, dementia and chronic disease and do their products need to be regulated like tobacco? Is it time for a class action suit?

Posted: July 15, 2023 Filed under: behavior, cancer, Evolutionary perspective, health, Nutrition/diet, self-healing | Tags: dementia, diabetes, diet, high fructose corn syrup, mortality, obsity, smoking, sugar, ultra-processed foods, UPF 2 CommentsAdapted from: Peper, E. & Harvey, R. (2024). Are Food Companies Responsible for the Epidemic in Diabetes, Cancer, Dementia and Chronic Disease and Do Their Products Need to Be Regulated Like Tobacco? Is It Time for a Class Action Suit? Thownsend Letter-the examiner of alternative medicine. https://www.townsendletter.com/e-letter-26-ultra-processed-foods-and-health-issues/

Erik Peper, PhD and Richard Harvey, PhD

Why are one third of young Americans becoming obese and at risk for diabetes?

Why are heart disease, cancer, and dementias occurring earlier and earlier? Is it genetics, environment, foods, or lifestyle?

Is it individual responsibility or the result of the quest for profits by agribusiness and the food industry?

Like the tobacco industry that sells products regulated because of their public health dangers, is it time for a class action suit against the processed food industry? The argument relates not only to the regulation of toxic or hazardous food ingredients (e.g., carcinogenic or obesogenic chemicals) but also to the regulation of consumer vulnerabilities. Addressing vulnerabilities to tobacco products include regulations such as how cigarette companies may not advertise their products for sale within a certain distance from school grounds.

Is it time to regulate nationally the installation of vending machines on school grounds selling sugar-sweetened beverages? Students have sensitivity to the enticing nature of advertised, and/or conveniently available consumable products such as ‘fast foods’ that are highly processed (e.g., packaged, preserved and practically imperishable). Whereas ‘processed foods’ have some nutritive value, and may technically pass as ‘nutritious’ food, the quality of processed ‘nutrients’ can be called into question. For the purpose of this blog other important questions to raise relate to ingredients which, alone or in combination, may contribute to the onset of or, the acceleration of a variety of chronic health outcomes related to various kinds of cancers, cardiovascular diseases, and diabetes.

It may be an over statement to suggest that processed food companies are directly responsible for the epidemic in diabetes, cancer, dementia and chronic disease and need to be regulated like tobacco. On the other hand, processed food companies should become much more regulated than they are now.

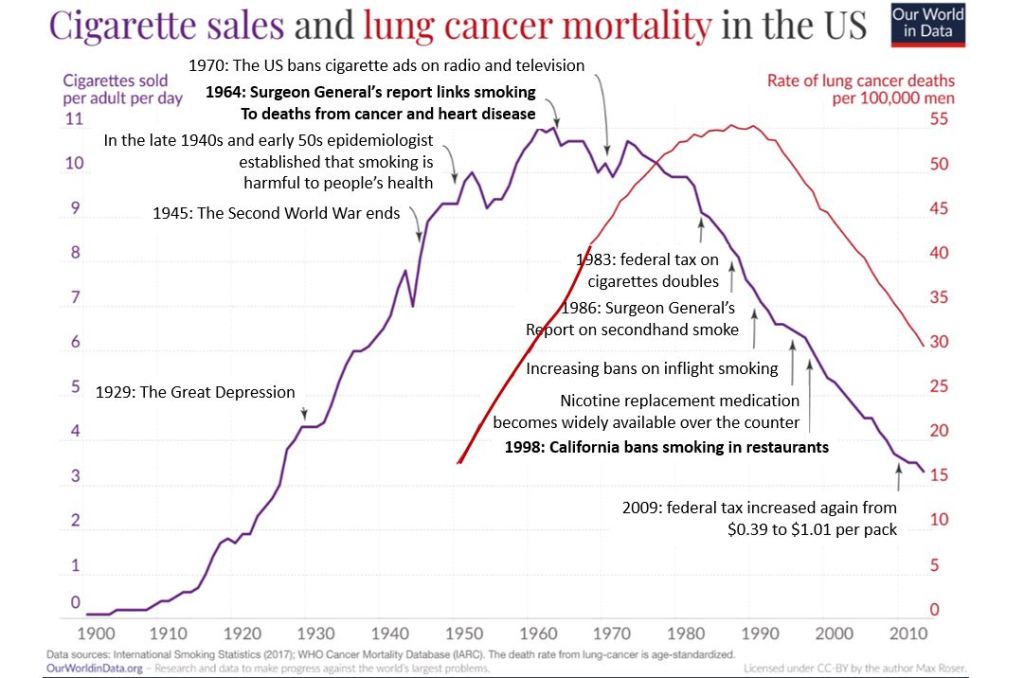

More than 80 years ago, smoking was identified as a significant factor contributing to lung cancer, heart disease and many other disorders. In 1964 the Surgeon Generals’ report officially linked smoking to deaths of cancer and heart disease (United States Public Health Service, 1964). Another 34 years pased before California prohibited smoking in restaurants in 1998 and, eventually inside all public buildings. The harms of smoking tobacco products were well known, yet many years passed with countless deaths and suffering which could have been prevented before regulation of tobacco products took place. Reviewing historical data there is about a 20 year delay (e.g., a whole generation) before death rates decrease in relation to when regulations became effective and smoking rates decreased, as shown in figure 1.

Figure 1. The relationship between smoking and lung cancer. Reproduced by permission from Roser, M. (2021). Smoking: How large of a global problem is it? And how can we make progress against it? Our world in data.

During those interim years before government actions limited smoking more effectively, tobacco companies hid data regarding the harmful effects of smoking. Arguably, the ‘Big Tobacco’ industry paid researchers to publish data which could confuse readers about tobacco product harm. There is evidence of some published articles suggesting that the harm of cigarette smoking was a hoax– all for the sake of boosting corporate profits (Bero, 2005).

Now we are experiencing a similar problem with the processed food industry. It has been suggested that alongside smoking and vaping, opioid use, a sedentary ‘couch potato’ lifestyle, and lack of exercise, ultra-processed food (UPF) that we eat severely affects our health.

Ultra-processed foods, which for many constitutes a majority of calories ranging from 55% to over 80% of the food they eat, contain chemical additives that trick the tastebuds, mouth and eventually our brain to desire those processed foods and eat more of them (Srour et al., 2022).

What are ultra-processed foods? Any foods that your great grandmother would not recognize as food. This includes all soft drinks, highly processed chips, additives, food coloring, stabilizers, processed proteins, etc. Even oils such as palm oil, canola oil, or soybean are ultra processed since they heated, highly processed with phosphoric acid to remove gums and waxes, neutralized with chemicals, bleached, and deodorized with high pressure steam (van Tulleken, 2023).

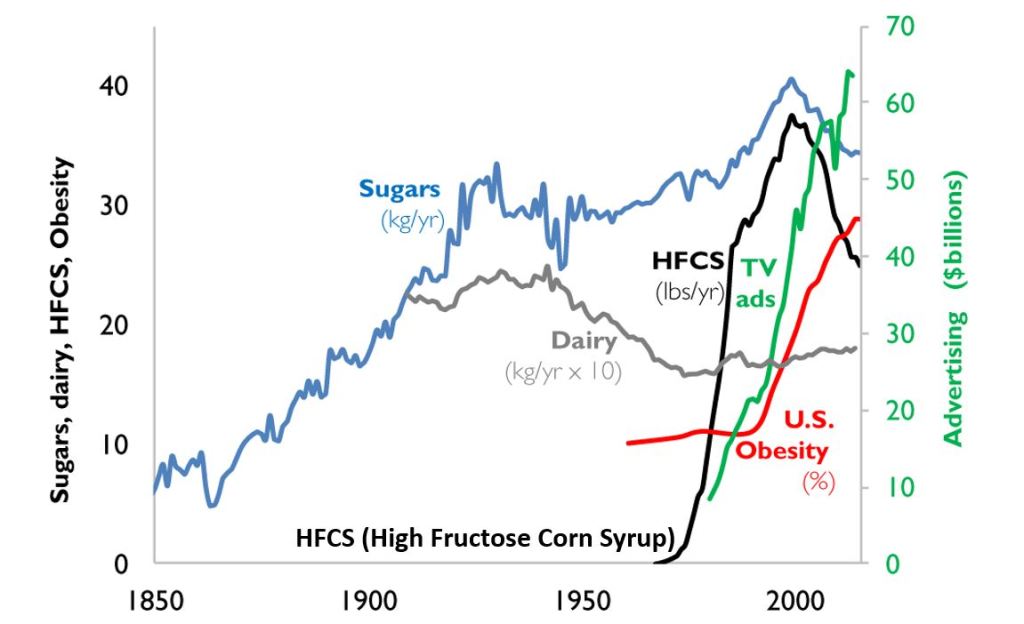

The data is clear! Since the 1970s obesity and inflammatory disease have exploded after ultra-processed foods became the constituents of the modern diet as shown in figure 2.

Figure 2. A timeline from 1850 to 2000 reflects the increase in use of refined sugar and high fructose corn syrup (HFCS) to the U.S. diet, together with the increase in U.S. obesity rate. The data for sugar, dairy and HFCS consumption per capita are from USDA Economic Research Service (Johnson et al., 2009) and reflects historical estimates before 1967 (Guyenet et al., 2017). The obesity data (% of U.S. adult population) are from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Trust for America’s Health. (stateofobesity.org). Total U.S. television advertising data are from the World Advertising Research Center (www.warc.com). The vertical measure (y–axis) for kilograms per year (kg/yr) on the left covers all data except advertising expenditures, which uses the vertical measure for advertising on the right. Reproduced by permission from Bentley et al, 2018.

This graph clearly shows a close association between the years that high fructose corn syrups (HFCS) were introduced into the American diet and an increase in TV advertising with corresponding increase in obesity. HFCS is an ultra-processed food and is a surrogate marker for all other ultra-processed foods. The best interpretation is that ultra-processed foods, which often contain HFCS, are a causal factor of the increase in obesity, and diabetes and in turn are risk factors for heart disease, cancers and dementias.

Ultra-processed foods are novel from an evolutionary perspective.

The human digestive system has only recently encountered sources of calories which are filled with so many unnatural chemicals, textures and flavors. Ultra-processed foods have been engineered, developed and product tested to increase the likelihood they are wanted by consumers and thereby increase sales and profits for the producers. These foods contain the ‘right amount’ processed materials to evoke the taste, flavor and feel of desired foods that ‘trick’ the consumer it eat them because they activate evolutionary preference for survival. Thus, these ultra-processed foods have become an ‘evolutionary trap’ where it is almost impossible not to eat them. We eat the food because it capitalized on our evolutionary preferences even though doing so is ultimately harmful for our health (for a detailed discussion on evolutionary traps, see Peper, Harvey & Faass, 2020).

An example is a young child wanting the candy while waiting with her parents at the supermarket checkout line. The advertised images of sweet foods trigger the cue to eat. Remember, breast milk is sweet and most foods in nature that are sweet in taste, provide calories for growth and survival and are not harmful. Calories are essential of growth. Thus, we have no intrinsic limit on eating sweets unlike foods that taste bitter.

As parents, we wish that our children (and even adults) have self-control and no desire to eat the candy or snacks that is displayed at eye level (eye candy) especially while waiting at the cashier. When reflecting about food advertising and the promotion of foods that are formulated to take advantage of ‘evolutionary traps’, who is responsible? Is it the child, who does not yet have the wisdom and self-control or, is it the food industry that ultra-processes the foods and adds ingredients into foods which can be harmful and then displays them to trigger an evolutionary preference for food that have been highly processed?

Every country that has adapted the USA diet of ultra-processed foods has experienced similar trends in increasing obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, etc. The USA diet is replacing traditional diets as illustrated by the availability of Coca-Cola. It is sold in over 200 countries and territories (Coca-Cola, 2023).

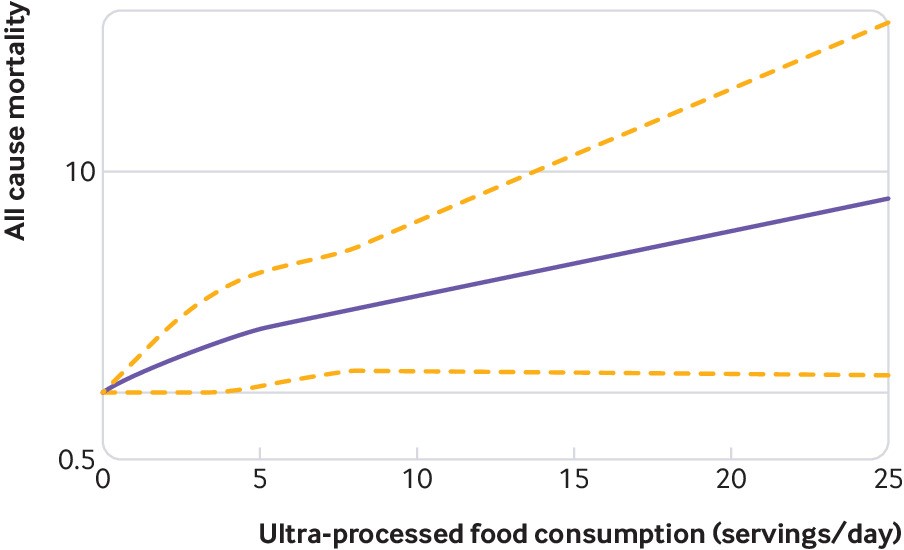

An increase in ultra-processed foods by 10 percent was associated with a 25 percent increase in the risk of dementia and a 14 per cent increase in the risk of Alzheimers’s (Li et al., 2022). More importantly, people who eat the highest proportion of their diet in ultra-processed foods had a 22%-62% increased risk of death compared to the people who ate the lowest proportion of processed foods (van Tulleken, 2023). In the USA, counties with the highest food swamp scores (the availability of fast food outlets in a county) had a 77% increased odds of high obesity-related cancer mortality (Bevel et al., 2023). The increase risk has also been observed for cardiovascular disease, coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease and all cause mortality as is shown in figure 3 (Srour et al., 2019; Rico-Campà et al., 2019).

Figure 3. Association between consumption of ultra-processed foods and all cause mortality. Reproduced from Rico-Campà et al, 2019.

The harmful effects of UPF holds up even when correcting for the amount of sugars, carbohydrates or fats in the diet and controlling for socio economic variables.

The logic that underlies this perspective is based upon the writing by Nassim Taleb (2012) in his book, Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder (Incerto). He provides an evolutionary perspective and offers broad and simple rules of health as well as recommendations for reducing UPF risk factors:

- Assume that anything that was not part of our evolutionary past is probably harmful.

- Remove the unnatural/unfamiliar (e.g. smoking/ e-cigarettes, added sugars, textured proteins, gums, stabilizers (guar gum, sodium alginate), emulsifiers (mono-and di-glycerides), modified starches, dextrose, palm stearin, and fats, colors and artificial flavoring or other ultra-processed food additives).

What can we do?

The solutions are simple and stated by Michael Pollan in his 2007 New York Times article, “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly Plants.” Eat foods that your great grandmother would recognize as foods (Pollan, 2009). Do not eat any of the processed foods that fill a majority of a supermarket’s space.

- Buy only whole organic natural foods and prepare them yourself.

- Request that food companies only buy and sell non-processed foods.

- Demand government action to tax ultra-processed food and limit access to these foods. In reality, it is almost impossible to expect people to choose healthy, organic foods when they are more expensive and not easily available in the American ‘food swamps and deserts’ (the presence of many fast food outlets or the absence of stores that have fresh produce and non-processed foods). We do have a choice. We can spend more money now for organic, health promoting foods or, pay much more later to treat illness related to UPF.

- It is time to take our cues from the tobacco wars that led to regulating tobacco products. We may even need to start class action suits against producers and merchants of UPF for causing increased illness and premature morbidity.

For more background information and the science behind this blog, read, the book, Ultra-processed people, by Chris van Tulleken.

Look at the following blogs for more background information.

References

Bentley, R.A., Ormerod, P. & Ruck, D.J. (2018). Recent origin and evolution of obesity-income correlation across the United States. Palgrave Commun 4, 146. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-018-0201-x

Bero, L. A. (2005). Tobacco Industry Manipulation of Research. Public Health Reports (1974-), 120(2), 200–208. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20056773

Bevel, M.S., Tsai, M., Parham, A., Andrzejak, S.E., Jones, S., & Moore, J.X. (2023). Association of Food Deserts and Food Swamps With Obesity-Related Cancer Mortality in the US. JAMA Oncol. 9(7), 909–916. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2023.0634

Coca-Cola. (2023). More on Coca-Cola. Accessed July 14, 2023. https://www.coca-cola.co.uk/our-business/faqs/how-many-countries-sell-coca-cola-is-there-anywhere-in-the-world-that-doesnt

Johnson, R.K., Appel, L.J., Brands, M., Howard, B.V., Lefevre, M., Lustig, R.H., Sacks, F., Steffen, L.M., & Wylie–Rosett, J. (2009). Dietary sugars intake and cardiovascular health: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 120(10), 1011–1020. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192627

Li, H., Li, S., Yang, H., et al, 2022. Association of ultraprocessed food consumption with the risk of dementia: a prospective cohort study. Neurology, 99, e1056-1066. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000200871

Peper, E., Harvey, R. & Faass, N. (2020). TechStress: How Technology is Hijacking Our Lives, Strategies for Coping, and Pragmatic Ergonomics. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books, pp 18-22, 151. https://www.amazon.com/Beyond-Ergonomics-Prevent-Fatigue-Burnout/dp/158394768X/ref=sr_1_1?crid=1U9Y82YO4DKKP&keywords=erik+peper&qid=1689372466&sprefix=erik+peper%2Caps%2C187&sr=8-1

Pollan, M. (2007). Unhappy meals. The New York Times Magazine. https://www.nytimes.com/2007/01/28/magazine/28nutritionism.t.html

Pollan, M. (2009). Food Rules: An Eater’s Manual. New York: Penguin Books. https://www.amazon.com/Food-Rules-Eaters-Michael-Pollan/dp/014311638X/ref=tmm_pap_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=1689373484&sr=8-2

Rico-Campà, A., Martínez-González, M. A., Alvarez-Alvarez, I., de Deus Mendonça, R., Carmen de la Fuente-Arrillaga, C., Gómez-Donoso, C., & Bes-Rastrollo, M. (2019). Association between consumption of ultra-processed foods and all cause mortality: SUN prospective cohort study. BMJ; 365: l1949 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l1949

Roser, M. (2021).Smoking: How large of a global problem is it? And how can we make progress against it? Our world in data. Assessed July 13, 2023. https://ourworldindata.org/smoking-big-problem-in-brief

Srour, B., Fezeu, L.K., Kesse-Guyot, E.,Alles, B., Mejean, C…(2019). Ultra-processed food intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: prospective cohort study (NutriNet-Santé) BMJ,365:l1451. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l1451

Srour, B., Kordahi, M. C., Bonazzi, E., Deschasaux-Tanguy, M., Touvier, M., & Chassaing, B. (2022). Ultra-processed foods and human health: from epidemiological evidence to mechanistic insights. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(22)00169-8

Taleb, N. N. (2012). Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder (Incerto). New York: Random House Publishing Group. (Kindle Locations 5906-5908). https://www.amazon.com/Antifragile-Things-Disorder-ANTIFRAGILE-Hardcover/dp/B00QOJ6MLC/ref=sr_1_4?crid=3BISYYG0RPGW5&keywords=Antifragile%3A+Things+That+Gain+from+Disorder+%28Incerto%29&qid=1689288744&s=books&sprefix=antifragile+things+that+gain+from+disorder+incerto+%2Cstripbooks%2C158&sr=1-4

Van Tulleken, C. (2023). Ultra-processed people. The science behind food that isn’t food. New Yoerk: W.W. Norton & Company. https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/1324036729/ref=ox_sc_act_title_1?smid=ATVPDKIKX0DER&psc=1

United States Public Health Service. (1964). The 1964 Report on Smoking and Health. United States. Public Health Service. Office of the Surgeon General. https://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/spotlight/nn/catalog?f%5Bexhibit_tags%5D%5B%5D=smoking

Mouth breathing and tongue position: a risk factor for health

Posted: June 8, 2023 Filed under: ADHD, behavior, Breathing/respiration, cognitive behavior therapy, Evolutionary perspective, healing, health, Nutrition/diet, self-healing, Uncategorized | Tags: babies, breastfeedging, development, infants, jaw, mouth breathing, neurocognitive develoment, nose breathing, sleep, tongue-tie Leave a commentErik Peper, PhD, BCB and Ron Swatzyna, PhD, LCSW, BCB, BCN

Adapted from: Peper, E., Swatzyna, R., & Ong, K. (2023). Mouth breathing and tongue position: a risk factor for health. Biofeedback. 51(3), 74–78 https://doi.org/10.5298/912512

Breathing usually occurs without awareness unless there are problems such as asthma, emphysema, allergies, or viral infections. Infant and child development may affect how we breathe as adults. This blog discusses the benefits of nasal breathing, factors that contribute to mouth breathing, how babies’ breastfeeding and chewing decreases the risk of mouth breathing, recommendations that parents may implement to support healthy development of a wider palate, and the embedded video presentation, How the Tongue Informs Healthy (or Unhealthy) Neurocognitive Development, by Karindy Ong, MA, CCC-SLP, CFT, .

Benefits of nasal breathing

Breathing through the nose filters, humidifies, warms, or cools the inhaled air as well as reduces the air turbulence in the upper airways. In addition, the epithelial cells of the nasal cavities produce nitric oxide that are carried into the lungs when inhaling during nasal breathing (Lundberg & Weitzberg, 1999). The nitric oxide contributes to healthy respiratory function by promoting vasodilation, aiding in airway clearance, exerting antimicrobial effects, and regulating inflammation. Breathing through the nose is associated with deeper and slower breathing rate than mouth breathing. This slower breathing also facilitates sympathetic parasympathetic balance and reduces airway irritation.

Mouth breathing

Some people breathe predominantly through their mouth although nose breathing is preferred and health promoting. Mouth breathing negatively impacts the ability to perform during the day as well as affect our cognitions and mood (Nestor, 2020). It contributes to disturbed sleep, snoring, sleep apnea, dry mouth upon waking, fatigue, allergies, ear infections, attention deficit disorders, crowded mis-aligned teeth, and poorer quality of life (Kahn & Ehrlich, 2018). Even the risk of ear infections in children is 2.4 time higher for mouth breathers than nasal breathers (van Bon et al, 1989) and nine and ten year old children who mouth breath have significantly poorer quality of life and have higher use of medications (Leal et al, 2016).

One recommendation to reduce mouth breathing is to tape the mouths closed with mouth tape (McKeown, 2021). Using mouth tape while sleeping bolsters nose breathing and may help people improve sleep, reduce snoring, and improves alertness when awake (Lee et al, 2022).

Experience how mouth breathing affects the throat and upper airway

Inhale quickly, like a gasp, as much air as possible through your open mouth. Exhale letting the air flow out through your mouth. Repeat once more.

Inhale quickly as much air through the nose, then exhale by allow the airflow out through the nose. Repeat once more.

What did you observe? Many people report that rapidly inhaling through the mouth causes the back of the throat and even upper airways to feel drier and irritated. This does not occur when inhaling through the nose. This simple experiment illustrates how habitual mouth breathing may irritate the airways.

Developmental behavior that contributes to mouth breathing

The development of mouth breathing may begin right at birth when the mouth, tongue, jaw and nasal area are still developing. The arch of the upper palate forms the roof of the oral cavity that separates the oral and nasal cavities. When the palate and jaw narrows, the arch of the palate increases and pushes upwards into the nasal area. This reduces space in the nasal cavity for the air to flow and obstructs nasal breathing. The highly vaulted palate is not only genetically predetermined but also by how we use our tongue and jaw from birth. The highly arched palate is only a recent anatomical phenomena since the physical structure of the upper palate and jaw from the pre- industrial era was wider (less arched upper palate) than many of our current skulls (Kahn & Ehrlich, 2018).

The role of the tongue in palate development

After babies are born, they breastfeed by sucking with the appropriate tongue movements that help widen the upper palate and jaw. On the other hand, when babies are bottle fed, the tongue tends to move differently which causes the cheek to pull in and the upper palate to arch which may create a high narrow upper palate and making the jaw narrower. There are many other possible factors that could cause mouth breathing such as tongue-tie (ankyloglossia), septal deviation, congenital malformation, enlarged adenoids and tonsils (Aden tonsillar hyperplasia), inflammatory diseases such as allergic rhinitis (Trabalon et al, 2012). Whatever the reasons, the result of the impoverished tongue movement and jaw increases the risk for having a higher arched upper palate that impedes nasal breathing and contributes to habitual mouth breathing.

The forces that operate on the mouth, jaw and palate during bottle feeding may be similar to when you suck on straw and the cheeks coming in with the face narrowing. The way the infants are fed will change the development of the physical structure that may result in lifelong problems and may contribute to developing a highly arched palate with a narrow jaw and facial abnormalities such as long face syndrome (Tourne, 1990).

To widen the upper palate and jaw, the infant needs to chew, chew and tear the food with their gums and teeth. Before the industrialization of foods, children had to tear food with their teeth, chew fibrous foods or gnaw at the meat on bones. The chewing forces allows the jaw to widen and develop so that when the permanent teeth are erupting, they would more likely be aligned since there would be enough space–eliminating the need for orthodontics. On the other hand, when young children eat puréed and highly processed soft foods (e.g., cereals soaked in milk, soft breads), the chewing forces are not powerful enough to encourage the widening of the palate and jaw.

Although the solution in adults can be the use of mouth tape to keep the mouth closed at night to retrain the breathing pattern, we should not wait until we have symptoms. The focus needs to be on prevention. The first step is an assessment whether the children’s tongue can do its job effectively or limited by tongue-tie and the arch of the palate. These structures are not totally fixed and can change depending on our oral habits. The field of orthodontics is based upon the premise that the physical structure of the jaw and palate can be changed, and teeth can be realigned by applying constant forces with braces.

Support healthy development of the palate and jaw

Breastfeed babies (if possible) for the first year of life and do NOT use bottle feeding. When weaning, provide chewable foods (fruits, vegetable, roots, berries, meats on bone) that was traditionally part of our pre-industrial diet. These foods support in infants’ healthy tongue and jaw development, which helps to support the normal widening of the palate to provide space for nasal breathing.

Provide fresh organic foods that children must tear and chew. Avoid any processed foods which are soft and do not demand chewing. This will have many other beneficial health effects since processed foods are high in simple carbohydrates and usually contain color additives as well as traces of pesticides and herbicides. The highly processed foods increase the risk of developing depression, type 2 diabetes, inflammatory disease, and colon cancer (Srour et al., 2019).

Sadly, the USA allows much higher residues of pesticide and herbicides that act as neurotoxins than are allowed in by the European Union. For example, the acceptable level of the herbicide glyphosate (Round-Up) is 0.7 parts per million in the USA while in the acceptable level is 0.01 parts per million in European countries (Tano, 2016; EPA, 2023; European Commission, 2023). The USA allows this higher exposure even though about half of the human gut microbiota are vulnerable to glyphosate exposure (Puigbò et al., 2022).

The negative effects of herbicides and pesticides are harmful for growing infants. Even fetal exposure from the mother (gestational exposure) is associated with an increase in behaviors related to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorders and executive function in the child when they are 7 to 12 years old (Sagiv et al., 2021) and organophosphate exposure is correlated with ADHD prevalence in children (Bouchard et al., 2010).

To implement these basic recommendations are very challenging. It means the mother has to breastfeed her infant during the first year of life. This is often not possible because of socioeconomic inequalities; work demands and medical complications. It also goes against the recent cultural norm that fathers should participate in caring for the baby by giving the baby a bottle of stored breast milk or formula.

From our perspective, women who give birth must have a year paid maternity leave to provide their infants with the best opportunity for health (e.g., breast-feeding, emotional bonding, and reduced financial stress). As a society, we have the option to pay the upfront cost now by providing a year- long maternity leave to mothers or later pay much more costs for treating chronic conditions that may have developed because we did not support the natural developmental process of babies.

Relevance to the field of neurofeedback and biofeedback

Clinicians often see clients, especially children with diagnostic labels such as ADHD who have failed to respond to numerous psychotherapies and pharmacotherapies. In the recent umbrella review and meta-analytic evaluation of recent meta-analyses, Leichsenring et al. (2022) found only small benefits overall for both types of intervention. They suggest that a paradigm shift in research seems to be required to achieve further progress in resolving mental health issues. As the past director of National Institute of Health, Dr. Thomas Insel pointed out that the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is not a valid instrument and should be a big wake up call for all of us to think outside the box (Insel, 2009). One factor that starts right at birth is the oral cavity development by dysfunctional tongue movements.

We want to make all of you aware of a serious issue in children that you may come across. For those of us who work with children children, we need to ask their parents about the following: tongue-tie, mouth breathing, bedwetting, high-vaulted palate, thumb sucking, abnormal eating issues, apraxia, dysarthria, and hypotonia. Research suggests that the palates of these children are so arched that the tongue cannot do its job effectively, causing multiple issues which may be related.

Please view the webinar from May 17, 2023. Presented by Karindy Ong, MA, CCC-SLP, CFT, How the Tongue Informs Healthy (or Unhealthy) Neurocognitive Development. The presentation explains the developmental process of the role the tongue plays and how it contributes to nasal breathing. Please pass it on to others who may have interest.

References

Bouchard, M.F., Bellinger, D.C., Wright, R.O., & Weisskopf, M.G. (2010). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and urinary metabolites of organophosphate pesticides. Pediatrics, 125(6), e1270-7. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-3058

EPA. (2023). Glyphosate. United States Environmental Protection Agency. Accessed April 1, 2023. https://www.epa.gov/ingredients-used-pesticide-products/glyphosate

European Commission. (2023). EU legislation on MRLs.Food Safety. Assessed April 1, 2023. https://food.ec.europa.eu/plants/pesticides/maximum-residue-levels/eu-legislation-mrls_en#:~:text=A%20general%20default%20MRL%20of,e.g.%20babies%2C%20children%20and%20vegetarians.

Insel, T.R. (2009). Translating scientific opportunity into public health impact: a strategic plan for research on mental illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 66(2), 128-133. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.540

Kahn, S. & Ehrlich, P.R. (2018). Jaws. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. https://www.amazon.com/Jaws-Hidden-Epidemic-Sandra-Kahn/dp/1503604136/ref=tmm_hrd_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=1685135054&sr=1-1

Leal, R.B., Gomes, M.C., Granville-Garcia, A.F., Goes, P.S.A., & de Menezes, V.A. (2016). Impact of Breathing Patterns on the Quality of Life of 9- to 10-year-old Schoolchildren. American Journal of Rhinology & Allergy, 30(5):e147-e152. https://doi.org/10.2500/ajra.2016.30.4363

Lee, Y.C., Lu, C.T., Cheng, W.N., & Li, H.Y. (2022).The Impact of Mouth-Taping in Mouth-Breathers with Mild Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Preliminary Study. Healthcare (Basel), 10(9), 1755. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10091755

Leichsenring, F., Steinert, C., Rabung, S. and Ioannidis, J.P.A. (2022), The efficacy of psychotherapies and pharmacotherapies for mental disorders in adults: an umbrella review and meta-analytic evaluation of recent meta-analyses. World Psychiatry, 21: 133-145. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20941

Lundberg, J.O. & Weitzberg, E. (1999). Nasal nitric oxide in man. Thorax. (10):947-52. https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.54.10.947

McKeown, P. (2021). The Breathing Cure: Develop New Habits for a Healthier, Happier, and Longer Life. Boca Raton, Fl “Humanix Books. https://www.amazon.com/BREATHING-CURE-Develop-Healthier-Happier/dp/1630061972/

Nestor, J. (2020). Breath: The New Science of a Lost Art. New York: Riverhead Books. https://www.amazon.com/Breath/dp/0593191358/ref=tmm_pap_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=1686191995&sr=8-1

Puigbò, P., Leino, L. I., Rainio, M. J., Saikkonen, K., Saloniemi, I., & Helander, M. (2022). Does Glyphosate Affect the Human Microbiota?. Life, 12(5), 707. https://doi.org/10.3390/life12050707

Sagiv, S.K., Kogut, K., Harley, K., Bradman, A., Morga, N., & Eskenazi, B. (2021). Gestational Exposure to Organophosphate Pesticides and Longitudinally Assessed Behaviors Related to Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Executive Function, American Journal of Epidemiology, 190(11), 2420–2431. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwab173

Srour, B. et al. (2019). Ultra-processed food intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: prospective cohort study (NutriNet-Santé).BMJ, 365. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l1451

Tano, B. (2016). The Layman’s Guide to Integrative Immunity. Integrative Medical Press. https://www.amazon.com/Laymans-Guide-Integrative-Immunity-Discover/dp/0983419299/_

Tourne, L.P. (1990). The long face syndrome and impairment of the nasopharyngeal airway. Angle Orthod, 60(3):167-76. https://doi.org/10.1043/0003

Trabalon, M. & Schaal, B. (2012). It takes a mouth to eat and a nose to breathe: abnormal oral respiration affects neonates’ oral competence and systemic adaptation. Int J Pediatr, 207605. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/207605

van Bon, M.J., Zielhuis, G.A., Rach, G.H., & van den Broek, P. (1989). Otitis media with effusion and habitual mouth breathing in Dutch preschool children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol, (2), 119-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-5876(89)90087-6

Eat what grows in season

Posted: December 14, 2021 Filed under: health, Nutrition/diet, self-healing | Tags: food, herbicide, organic foods, pesticides Leave a commentAndrea Castillo and Erik Peper

We are what we eat. Our body is synthesized from the foods we eat. Creating the best conditions for a healthy body depends upon the foods we ingest as implied by the phrase, Let food be thy medicine, attributed to Hippocrates, the Greek founder of western medicine (Cardenas, 2013). The foods are the building blocks for growth and repair. Comparing our body to building a house, the building materials are the foods we eat, the architect’s plans are our genetic coding, the care taking of the house is our lifestyle and the weather that buffers the house is our stress reactions. If you build a house with top of the line materials and take care of it, it will last a life time or more. Although the analogy of a house to the body is not correct since a house cannot repair itself, it is a useful analogy since repair is an ongoing process to keep the house in good shape. Our body continuously repairs itself in the process of regeneration. Our health will be better when we eat organic foods that are in season since they have the most nutrients.

Organic foods have much lower levels of harmful herbicides and pesticides which are neurotoxins and harmful to our health (Baker et al., 2002; Barański, et al, 2014). Crops have been organically farmed have higher levels of vitamins and minerals which are essential for our health compared to crops that have been chemically fertilized (Peper, 2017),

Even seasonality appears to be a factor. Foods that are outdoor grown or harvested in their natural growing period for the region where it is produced, tend to have more flavor that foods that are grown out of season such as in green houses or picked prematurely thousands of miles away to allow shipping to the consumer. Compare the intense flavor of small strawberry picked in May from the plant grown in your back yard to the watery bland taste of the great looking strawberries bought in December.

The seasonality of food

It’s the middle of winter. The weather has cooled down, the days are shorter, and some nights feel particularly cozy. Maybe you crave a warm bowl of tomato soup so you go to the store, buy some beautiful organic tomatoes, and make yourself a warm meal. The soup is… good. But not great. It is a little bland even though you salted it and spiced it. You can’t quite put your finger on it, but it feels like it’s missing more tomato flavor. But why? You added plenty of tomatoes. You’re a good cook so it’s not like you messed up the recipe. It’s just—missing something.

That something could easily be seasonality. The beautiful, organic tomatoes purchased from the store in the middle of winter could not have been grown locally, outside. Tomatoes love warm weather and die when days are cooler, with temperatures dropping to the 30s and 40s. So why are there organic tomatoes in the store in the middle of cold winters? Those tomatoes could’ve been grown in a greenhouse, a human-made structure to recreate warmer environments. Or, they could’ve been grown organically somewhere in the middle of summer in the southern hemisphere and shipped up north (hello, carbon emissions!) so you can access tomatoes year-round.

That 24/7 access isn’t free and excellent flavor is often a sacrifice we pay for eating fruits and vegetables out of season. Chefs and restaurants who offer seasonal offerings, for example, won’t serve bacon, lettuce, tomato (BLT) sandwiches in winter. Not because they’re pretentious, but because it won’t taste as great as it would in summer months. Instead of winter BLTs, these restaurants will proudly whip up seasonal steamed silky sweet potatoes or roasted brussels sprouts with kimchee puree.

When we eat seasonally-available food, it’s more likely we’re eating fresher food. A spring asparagus, summer apricot, fall pear, or winter grapefruit doesn’t have to travel far to get to your plate. With fewer miles traveled, the vitamins, minerals, and secondary metabolites in organic fruits and vegetables won’t degrade as much compared to fruits and vegetables flown or shipped in from other countries. Seasonal food tastes great and it’s great for you too.

If you’re curious to eat more of what’s in season, visit your local farmers market if it’s available to you. Strike up a conversation with the people who grow your food. If farmers markets are not available, take a moment to learn what is in season where you live and try those fruits and vegetables next time to go to the store. This Seasonal Food Guide for all 50 states is a great tool to get you started.

Once you incorporate seasonal fruits and vegetables into your daily meals, your body will thank you for the health boost and your meals will gain those extra flavors. Remember, you’re not a bad cook: you just need to find the right seasonal partners so your dinners are never left without that extra little something ever again.

Sign up for Andrea Castillo’s Seasonal, a newsletter that connects you to the Bay Area food system, one fruit and vegetable at a time. Andrea is a food nerd who always wants to know the what’s, how’s, when’s, and why’s of the food she eats.

References

Baker, B.P., Benbrook, C.M., & Groth III, E., & Lutz, K. (2002). Pesticide residues in conventional, integrated pest management (IPM)-grown and organic foods: insights from three US data sets. Food Additives and Contaminants, 19(5) http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02652030110113799

Barański, M., Średnicka-Tober, D., Volakakis, N., Seal, C., Sanderson, R., Stewart, G., . . . Leifert, C. (2014). Higher antioxidant and lower cadmium concentrations and lower incidence of pesticide residues in organically grown crops: A systematic literature review and meta-analyses. British Journal of Nutrition, 112(5), 794-811. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114514001366

Cardenas, E. (2013). Let not thy food be confused with thy medicine: The Hippocratic misquotation,e-SPEN Journal, I(6), e260-e262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnme.2013.10.002

Peper, E. (2017). Yes, fresh organic food is better! the peper perspective. https://peperperspective.com/2017/10/27/yes-fresh-organic-food-is-better/

Reduce your risk of COVID-19 variants and future pandemics

Posted: July 5, 2021 Filed under: behavior, health, Nutrition/diet, self-healing | Tags: COVID-19, immune, pandemic, prevention, vitamin D 2 CommentsErik Peper, PhD and Richard Harvey, PhD

The number of hospitalizations and deaths from COVID-19 are decreasing as more people are being vaccinated. At the same time, herd immunity will depend on how vaccinated and unvaccinated people interact with one another. Close-proximity, especially indoor interactions, increases the likelihood of transmission of coronavirus for unvaccinated individuals. During the summer months, people tend to congregate outdoors which reduces viral transmission and also increases vitamin D production which supports the immune system (Holick, 2021)..

Most likely, COVID-19 disease will become endemic because the SARS-CoV-2 virus will continue to mutate. Already Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla stated on April 15, 2021 that people will “likely” need a third dose of a Covid-19 vaccine within 12 months of getting fully vaccinated. Although, at this moment the vaccines are effective against several variants, we need to be ready for the next COVID XX outbreak.

To reduce future infections, the focus of interventions should 1) reduce virus exposure, 2) vaccinate to activate the immune system, and 3) enhance the innate immune system competence. The risk of illness may relate to virus density exposure and depend upon the individual’s immune competence (Gandhi & Rutherford, 2020; Mukherjee, 2020) which can be expressed in the following equation.

Reduce viral load (hazardous exposure)

Without exposure to the virus and its many variants, the risk is zero which is impossible to achieve in democratic societies. People do not live in isolated bubbles but in an interconnected world and the virus does not respect borders or nationalities. Therefore, public health measures need to focus upon strategies that reduce virus exposure by encouraging or mandating wearing masks, keeping social distance, limiting social contact, and increasing fresh air circulation.

Wearing masks reduces the spread of the virus since people may shed viruses one or two days before experiencing symptoms (Lewis et al., 2021). When a person exhales through the mask, a good fitting N95 mask will filter out most of the virus and thereby reduce the spread of the virus during exhalation. To protect oneself from inhaling the virus, the mask needs be totally sealed around the face with the appropriate filters. Systematic observations suggest that many masks such as bandanas or surgical masks do not filter out the virus (Fisher et al., 2020).

Fresh air circulation reduces the virus exposure and is more important than the arbitrary 6 feet separation (CDC, May 13, 2021). If separated by 6 feet in an enclosed space, the viral particles in the air will rapidly increase even when the separation is 10 feet or more. On the other hand, if there is sufficient fresh air circulation, even three feet of separation would not be a problem. The spatial guidelines need to be based upon air flow and not on the distance of separation as illustrated in the outstanding graphical modeling schools by Nick Bartzokas et al. (February 26, 2021) in the New York Times article, Why opening windows is a key to reopening schools.

The public health recommendations of sheltering-in-place to prevent exposure or spreading the virus may also result in social isolation. Thus, shelter-in-place policies have resulted in compromising physical health such as weight gain (e.g. average increase of more than 7lb in weight in America according to Lin et al., 2021), reduced physical activity and exercise levels (Flanagan et al., 2021) and increased anxiety and depression (e.g. a three to four fold increase in the self-report of anxiety or depression according to Abbott, 2021). Increases in weight, depression and anxiety symptoms tend to decrease immune competence (Leonard, 2010). In addition, the stay at home recommendations especially in the winter time meant that individuals are less exposed to sunlight which results in lower vitamin D levels which is correlated with increased COVID-19 morbidity (Seheult, 2020).

Increase immune competence

Vaccination is the primary public health recommendation to prevent the spread and severity of COVID-19. Through vaccination, the body increases its adaptive capacity and becomes primed to respond very rapidly to virus exposure. Unfortunately, as Pfizer Chief Executive Albert Bourla states, there is “a high possibility” that emerging variants may eventually render the company’s vaccine ineffective (Steenhuysen, 2021). Thus, it is even more important to explore strategies to enhance immune competence independent of the vaccine.

Public Health policies need to focus on intervention strategies and positive health behaviors that optimize the immune system capacity to respond. The research data has been clear that COVID -19 is more dangerous for those whose immune systems are compromised and have comorbidities such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease, regardless of age.

Comorbidity and being older are the significant risk factors that contribute to COVID-19 deaths. For example, in evaluating all patients in the Fair Health National Private Insurance Claims (FH NPIC’s) longitudinal dataset, researchers identified 467,773 patients diagnosed with COVID-19 from April 1, 2020, through August 31, 2020. The severity of the illness and death from COVID-19 depended on whether the person had other co-morbidities first as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The distribution of patients with and without a comorbidity among all patients diagnosed with COVID-19 (left) and all deceased COVID-19 patients (right) April-August 2020. Reproduced by permission from: https://www.ajmc.com/view/contributor-links-between-covid-19-comorbidities-mortality-detailed-in-fair-health-study

Each person who died had about 2 or 3 types of pre-existing co-morbidities such as cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, obesity, congestive heart failure, chronic kidney disease, respiratory disease and cancer (Ssentongo et al., 2020; Gold et al., 2020). The greater the frequency of comorbidities the greater the risk of death, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Across all age groups, the risk of COVID-19 death increased significantly as a patient’s number of comorbidities increased. Compared to patients with no comorbidities. Reproduced by permission from https://s3.amazonaws.com/media2.fairhealth.org/whitepaper/asset/Risk%20Factors%20for%20COVID-19%20Mortality%20among%20Privately%20Insured%20Patients%20-%20A%20Claims%20Data%20Analysis%20-%20A%20FAIR%20Health%20White%20Paper.pdf