Reduce your risk of COVID-19 variants and future pandemics

Posted: July 5, 2021 Filed under: behavior, health, Nutrition/diet, self-healing | Tags: COVID-19, immune, pandemic, prevention, vitamin D 2 CommentsErik Peper, PhD and Richard Harvey, PhD

The number of hospitalizations and deaths from COVID-19 are decreasing as more people are being vaccinated. At the same time, herd immunity will depend on how vaccinated and unvaccinated people interact with one another. Close-proximity, especially indoor interactions, increases the likelihood of transmission of coronavirus for unvaccinated individuals. During the summer months, people tend to congregate outdoors which reduces viral transmission and also increases vitamin D production which supports the immune system (Holick, 2021)..

Most likely, COVID-19 disease will become endemic because the SARS-CoV-2 virus will continue to mutate. Already Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla stated on April 15, 2021 that people will “likely” need a third dose of a Covid-19 vaccine within 12 months of getting fully vaccinated. Although, at this moment the vaccines are effective against several variants, we need to be ready for the next COVID XX outbreak.

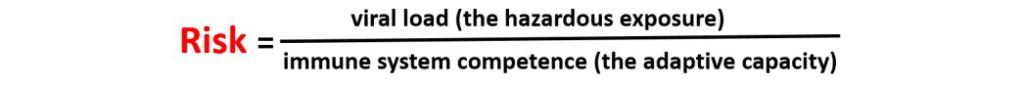

To reduce future infections, the focus of interventions should 1) reduce virus exposure, 2) vaccinate to activate the immune system, and 3) enhance the innate immune system competence. The risk of illness may relate to virus density exposure and depend upon the individual’s immune competence (Gandhi & Rutherford, 2020; Mukherjee, 2020) which can be expressed in the following equation.

Reduce viral load (hazardous exposure)

Without exposure to the virus and its many variants, the risk is zero which is impossible to achieve in democratic societies. People do not live in isolated bubbles but in an interconnected world and the virus does not respect borders or nationalities. Therefore, public health measures need to focus upon strategies that reduce virus exposure by encouraging or mandating wearing masks, keeping social distance, limiting social contact, and increasing fresh air circulation.

Wearing masks reduces the spread of the virus since people may shed viruses one or two days before experiencing symptoms (Lewis et al., 2021). When a person exhales through the mask, a good fitting N95 mask will filter out most of the virus and thereby reduce the spread of the virus during exhalation. To protect oneself from inhaling the virus, the mask needs be totally sealed around the face with the appropriate filters. Systematic observations suggest that many masks such as bandanas or surgical masks do not filter out the virus (Fisher et al., 2020).

Fresh air circulation reduces the virus exposure and is more important than the arbitrary 6 feet separation (CDC, May 13, 2021). If separated by 6 feet in an enclosed space, the viral particles in the air will rapidly increase even when the separation is 10 feet or more. On the other hand, if there is sufficient fresh air circulation, even three feet of separation would not be a problem. The spatial guidelines need to be based upon air flow and not on the distance of separation as illustrated in the outstanding graphical modeling schools by Nick Bartzokas et al. (February 26, 2021) in the New York Times article, Why opening windows is a key to reopening schools.

The public health recommendations of sheltering-in-place to prevent exposure or spreading the virus may also result in social isolation. Thus, shelter-in-place policies have resulted in compromising physical health such as weight gain (e.g. average increase of more than 7lb in weight in America according to Lin et al., 2021), reduced physical activity and exercise levels (Flanagan et al., 2021) and increased anxiety and depression (e.g. a three to four fold increase in the self-report of anxiety or depression according to Abbott, 2021). Increases in weight, depression and anxiety symptoms tend to decrease immune competence (Leonard, 2010). In addition, the stay at home recommendations especially in the winter time meant that individuals are less exposed to sunlight which results in lower vitamin D levels which is correlated with increased COVID-19 morbidity (Seheult, 2020).

Increase immune competence

Vaccination is the primary public health recommendation to prevent the spread and severity of COVID-19. Through vaccination, the body increases its adaptive capacity and becomes primed to respond very rapidly to virus exposure. Unfortunately, as Pfizer Chief Executive Albert Bourla states, there is “a high possibility” that emerging variants may eventually render the company’s vaccine ineffective (Steenhuysen, 2021). Thus, it is even more important to explore strategies to enhance immune competence independent of the vaccine.

Public Health policies need to focus on intervention strategies and positive health behaviors that optimize the immune system capacity to respond. The research data has been clear that COVID -19 is more dangerous for those whose immune systems are compromised and have comorbidities such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease, regardless of age.

Comorbidity and being older are the significant risk factors that contribute to COVID-19 deaths. For example, in evaluating all patients in the Fair Health National Private Insurance Claims (FH NPIC’s) longitudinal dataset, researchers identified 467,773 patients diagnosed with COVID-19 from April 1, 2020, through August 31, 2020. The severity of the illness and death from COVID-19 depended on whether the person had other co-morbidities first as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The distribution of patients with and without a comorbidity among all patients diagnosed with COVID-19 (left) and all deceased COVID-19 patients (right) April-August 2020. Reproduced by permission from: https://www.ajmc.com/view/contributor-links-between-covid-19-comorbidities-mortality-detailed-in-fair-health-study

Each person who died had about 2 or 3 types of pre-existing co-morbidities such as cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, obesity, congestive heart failure, chronic kidney disease, respiratory disease and cancer (Ssentongo et al., 2020; Gold et al., 2020). The greater the frequency of comorbidities the greater the risk of death, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Across all age groups, the risk of COVID-19 death increased significantly as a patient’s number of comorbidities increased. Compared to patients with no comorbidities. Reproduced by permission from https://s3.amazonaws.com/media2.fairhealth.org/whitepaper/asset/Risk%20Factors%20for%20COVID-19%20Mortality%20among%20Privately%20Insured%20Patients%20-%20A%20Claims%20Data%20Analysis%20-%20A%20FAIR%20Health%20White%20Paper.pdf

Although the risk of serious illness and death is low for young people, the presence of comorbidity increases the risk. Kompaniyets et al. (2021) reported that for patients under 18 years with severe COVID-19 illness who required ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, or died most had underlying medical conditions such as asthma, neurodevelopmental disorders, obesity, essential hypertension or complex chronic diseases such as malignant neoplasms or multiple chronic conditions.

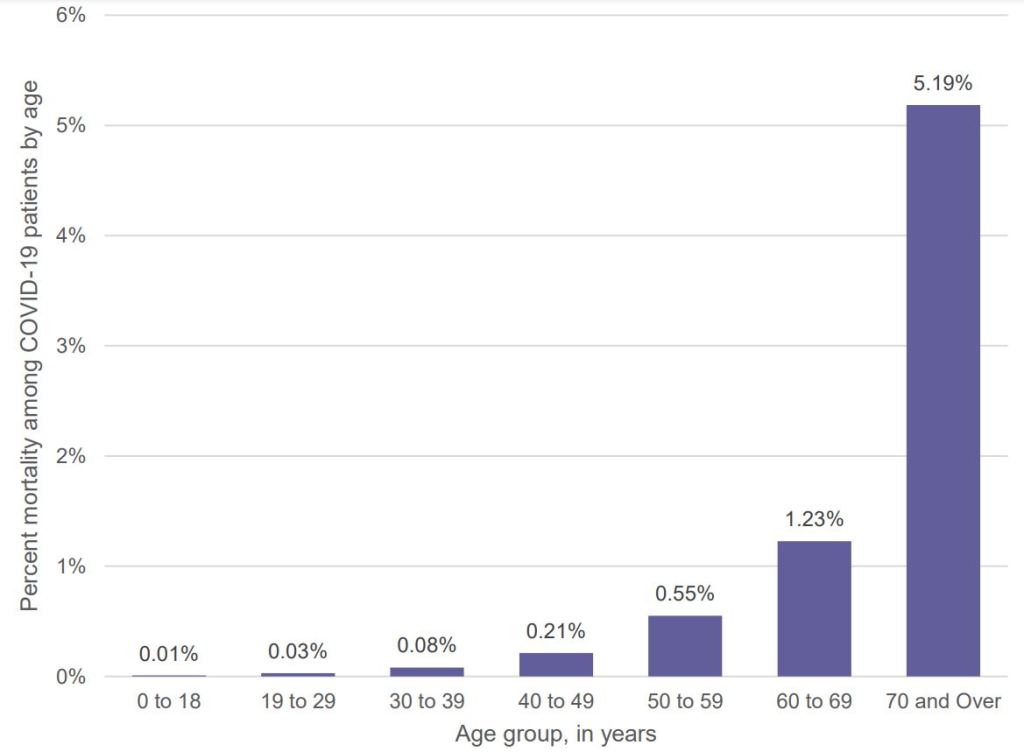

Consistent with earlier findings, the Fair Health National Private Insurance Claims (FH NPIC’s) longitudinal dataset also showed that the COVID-19 mortality rate rose sharply with age as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Percent mortality among COVID-19 patients by age, April-August 2020. Reproduced by permission from: https://s3.amazonaws.com/media2.fairhealth.org/whitepaper/asset/Risk%20Factors%20for%20COVID-19%20Mortality%20among%20Privately%20Insured%20Patients%20-%20A%20Claims%20Data%20Analysis%20-%20A%20FAIR%20Health%20White%20Paper.pdf

Optimize antibody response from vaccinations

Assuming that the immune system reacts similarly to other vaccinations, higher antibody response is evoked when the vaccine is given in the morning versus the afternoon or after exercise (Long et al., 2016; Long et al., 2012). In addition, the immune response may be attenuated if the person suppresses the body’s natural immune response–the flulike symptoms which may occur after the vaccination–with Acetaminophen (Tylenol (Graham et al, 1990).

Support the immune system with a healthy life style

Support the immune system by implementing a lifestyle that reduces the probability of developing comorbidities. This means reducing risk factors such as vaping, smoking, immobility and highly processed foods. For example, young people who vape experience a fivefold increase to become seriously sick with COVID-19 (Gaiha, Cheng, & Halpern-Felsher, 2020); similarly, cigarette smoking increases the risk of COVID morbidity and mortality (Haddad, Malhab, & Sacre, 2021).

There are many factors that have contributed to the epidemic of obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease and other chronic diseases. In many cases, the environment and lifestyle factors (lack of exercise, excessive intake of highly processed foods, environmental pollution, social isolation, stress, etc.) significantly contribute to the initiation and development of comorbidities. Genetics also is a factor; however, the generic’s risk factor may not be triggered if there are no environmental/behavioral exposures. Phrasing it colloquially, Genetics loads the gun, environment and behavior pulls the trigger. Reducing harmful lifestyle behaviors and environment is not simply an individual’s responsibility but a corporate and governmental responsibility. At present, harmful lifestyles choices are actively supported by corporate and government policies that choose higher profits over health. For example, highly processed foods made from corn, wheat, soybeans, rice are grown by farmers with US government farm subsidies. Thus, many people especially of lower economic status live in food deserts where healthy non-processed organic fruits and vegetable foods are much less available and more expensive (Darmon & Drewnowski, 2008; Michels, Vynckier, Moreno, L.A. et al. 2018; CDC, 2021). In the CDC National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey that analyzed the diet of 10,308 adults, researchers Siegel et al. (2016) found that “Higher consumption of calories from subsidized food commodities was associated with a greater probability of some cardiometabolic risks” such as higher levels of obesity and unhealthy blood glucose levels (which raises the risk of Type 2 diabetes).

Immune competence is also affected by many other factors such as exercise, stress, shift work, social isolation, and reduced micronutrients and Vitamin D (Zimmermann & Curtis, 2019). Even being sedentary increases the risk of dying from COVID as reported by the Kaiser Permanente Southern California study of 50,000 people who developed COVID (Sallis et al., 2021).

People who exercised 10 minutes or less each week were hospitalized twice as likely and died 2.5 times more than people who exercised 150 minutes a week (Sallis et al., 2021). Although exercise tends to enhance immune competence (da Silveira et al, 2020), it is highly likely that exercise is a surrogate marker for other co-morbidities such as obesity and heart disease as well as aging. At the same time sheltering–in-place along with the increase in digital media has significantly reduced physical activity.

The importance of vitamin D

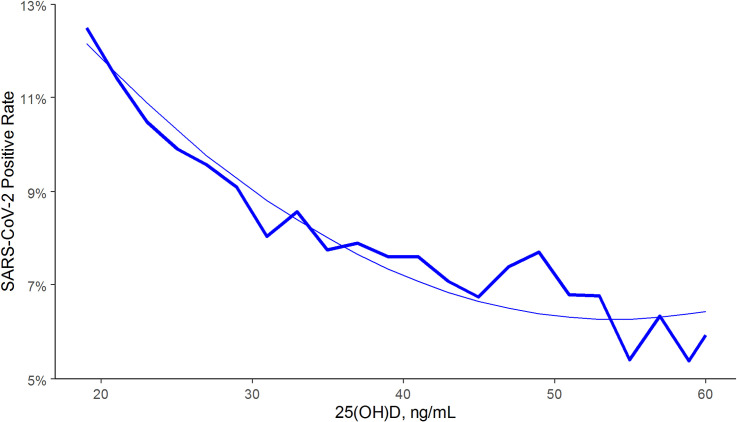

Low levels of vitamin D is correlated with poorer prognosis for patients with COVID-19 (Munshi et al., 2021). Kaufman et al. (2020) reported that the positivity rate correlated inversely with vitamin D levels as shown in figure 4.

Figure 4. SARS-CoV-2 NAAT positivity rates and circulating 25(OH)D levels in the total population. From: Kaufman, H.W., Niles, J.K., Kroll, M.H., Bi, C., Holick, M.F. (2020). SARS-CoV-2 positivity rates associated with circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels. PLoS One. 15(9):e0239252. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239252

Vitamin D is a modulator for the immune system (Baeke, Takiishi, Korf, Gysemans, & Mathieu, 2010). There is an inverse correlation of all-cause, cardiovascular, cancer, and respiratory disease mortality with hydroxyvitamin D concentrations in a large cohort study (Schöttker et al., 2013). For a superb discussion about how much vitamin D is needed, see the presentation, The D-Lightfully Controversial Vitamin D: Health Benefits from Birth until Death, by Dr. Michael F. Holick, Ph.D., M.D. from the University Medical Center Boston.

Low vitamin D levels may partially explain why in the winter there is an increase in influenza. During winter time, people have reduced sunlight exposure so that their skin does not produce enough vitamin D. Lower levels of vitamin D may be a cofactor in the increased rates of COVID among people of color and older people. The darker the skin, the more sunlight the person needs to produce Vitamin D and as people become older their skin is less efficient in producing vitamin D from sun exposure (Harris, 2006; Gallagher, 2013). Vitamin D also moderates macrophages by regulating the release, and the over-release of inflammatory factors in the lungs (Khan et al., 2021).

Watch the interesting presentation by Professor Roger Seheult, MD, UC Riverside School of Medicine, Vitamin D and COVID 19: The Evidence for Prevention and Treatment of Coronavirus (SARS CoV 2). 12/20/2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ha2mLz-Xdpg

What can be done NOW to enhance immune competence?

We need to recognize that once the COVID-19 pandemic has passed, it does not mean it is over. It is only a reminder that a new COVID-19 variant or another new virus will emerge in the future. Thus, the government public health policies need to focus on promoting health over profits and aim at strategies to prevent the development of chronic illnesses that affect immune competence. One take away message is to incorporate behavioral medicine prescriptions supporting a healthy lifestyle into treatment plans, such as prescribing a walk in the sun to increase vitamin D production and develop dietary habits of eating organic locally grown vegetable and fruits foods. Even just reducing the refined sugar content in foods and drinks is challenging although it may significantly reduce incidence and prevalence of obesity and diabetes (World Health Organization, 2017. The benefits of such an approach has been clearly demonstrated by the Pennsylvania-based Geisinger Health System’s Fresh Food Farmacy. This program for food-insecure people with Type 2 diabetes and their families provides enough fresh fruits and vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins for two healthy meals a day five days a week. After one year there was a 40 percent decrease in the risk of death or serious complications and an 80 percent drop in medical costs per year (Brody, 2020).

The simple trope of this article ‘eat well, exercise and get good rest’ and increase your immune competence concludes with some simple reminders.

- Increase availability of organic foods since they do not contain pesticides such as glyphosate residue that reduce immune competence.

- Increase vegetable and fruits and reduce highly processed foods, simple carbohydrates and sugars.

- Decrease sitting and increase movement and exercise

- Increase sun exposure without getting sunburns

- Master stress management

- Increase social support

For additional information see: https://peperperspective.com/2020/04/04/can-you-reduce-the-risk-of-coronavirus-exposure-and-optimize-your-immune-system/

References

Baeke, F., Takiishi, T., Korf, H., Gysemans, C., & Mathieu, C. (2010). Vitamin D: modulator of the immune system,Current Opinion in Pharmacology,10(4), 482-496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coph.2010.04.001

Brody, J. (2020). How Poor Diet Contributes to Coronavirus Risk. The New York Times, April 20, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/20/well/eat/coronavirus-diet-metabolic-health.html?referringSource=articleShare

CDC. (2021). Adult Obesity Prevalence Maps. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/prevalence-maps.html#nonhispanic-white-adults

CDC. (May 13, 2021). Ways COVID-19 Spreads. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/how-covid-spreads.html

Darmon, N. & Drewnowski, A. (2008). Does social class predict diet quality?, The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 87(5), 2008, 1107–1117. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/87.5.1107

da Silveira, M. P., da Silva Fagundes, K. K., Bizuti, M. R., Starck, É., Rossi, R. C., & de Resende E Silva, D. T. (2021). Physical exercise as a tool to help the immune system against COVID-19: an integrative review of the current literature. Clinical and experimental medicine, 21(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10238-020-00650-3

Elflein, J. (2021). COVID-19 deaths reported in the U.S. as of January 2, 2021, by age. Downloaded, 1/13/2021 from https://www.statista.com/statistics/1191568/reported-deaths-from-covid-by-age-us/

Fisher, E. P., Fischer, M.C., Grass, D., Henrion, I., Warren, W.S., & Westmand, E. (2020). Low-cost measurement of face mask efficacy for filtering expelled droplets during speech. Science Advance, (6) 36, eabd3083. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abd3083

Flanagan. E.W., Beyl, R.A., Fearnbach, S.N., Altazan, A.D., Martin, C.K., & Redman, L.M. (2021). The Impact of COVID-19 Stay-At-Home Orders on Health Behaviors in Adults. Obesity (Silver Spring), (2), 438-445. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.23066

Gaiha, S.M., Cheng, J., & Halpern-Felsher, B. (2020). Association Between Youth Smoking, Electronic Cigarette Use, and COVID-19. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(4), 519-523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.07.002

Gallagher J. C. (2013). Vitamin D and aging. Endocrinology and metabolism clinics of North America, 42(2), 319–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecl.2013.02.004

Gandhi, M. & Rutherford, G. W. (2020). Facial Masking for Covid-19 — Potential for “Variolation” as We Await a Vaccine. New England Journal of Medicine, 383(18), e101 https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp2026913

Gold, M.S., Sehayek, D., Gabrielli, S., Zhang, X., McCusker, C., & Ben-Shoshan, M. (2020). COVID-19 and comorbidities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Postgrad Med, 132(8), 749-755. https://doi.org/10.1080/00325481.2020.1786964

Graham, N.M., Burrell, C.J., Douglas, R.M., Debelle, P., & Davies, L. (1990). Adverse effects of aspirin, acetaminophen, and ibuprofen on immune function, viral shedding, and clinical status in rhinovirus-infected volunteers. J Infect Dis., 162(6), 1277-82. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/162.6.1277

Haddad, C., Malhab, S.B., & Sacre, H. (2021). Smoking and COVID-19: A Scoping Review. Tobacco Use Insights, 14, First Published February 15, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1177/1179173X21994612

Harris, S.S. (2006). Vitamin D and African Americans. The Journal of Nutrition, 136(4), 1126-1129. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/136.4.1126

Kaufman, H.W., Niles, J.K., Kroll, M.H., Bi, C., Holick, M.F. (2020). SARS-CoV-2 positivity rates associated with circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels. PLoS One. 15(9):e0239252. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239252

Khan, A. H., Nasir, N., Nasir, N., Maha, Q., & Rehman, R. (2021). Vitamin D and COVID-19: is there a role?. Journal of Diabetes & Metabolic Disorders, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40200-021-00775-6

Kompaniyets, L., Agathis, N.T., Nelson, J.M., et al. (2021). Underlying Medical Conditions Associated With Severe COVID-19 Illness Among Children. JAMA Netw Open. 4(6):e2111182. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.11182

Leonard B. E. (2010). The concept of depression as a dysfunction of the immune system. Current immunology reviews, 6(3), 205–212. https://doi.org/10.2174/157339510791823835

Lewis, N. M., Duca, L. M., Marcenac, P., Dietrich, E. A., Gregory, C. J., Fields, V. L….Kirking, H. L. (2021). Characteristics and Timing of Initial Virus Shedding in Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2, Utah, USA. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 27(2), 352-359. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2702.203517

Long, J.E., Drayson, M.T., Taylor, A.E., Toellner, K.M., Lord, J.M., & Phillips, A.C. (2016). Morning vaccination enhances antibody response over afternoon vaccination: A cluster-randomised trial. Vaccine, 34(24), 2679-85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.04.032.

Long. J.E., Ring, C., Drayson, M., Bosch, J., Campbell, J.P., Bhabra, J., Browne, D., Dawson, J., Harding, S., Lau, J., & Burns, V.E. (2012). Vaccination response following aerobic exercise: can a brisk walk enhance antibody response to pneumococcal and influenza vaccinations? Brain Behav Immun., 26(4), 680-687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2012.02.004

Merelli, A. (2021, February 2). Pfizer’s Covid-19 vaccine is set to be one of the most lucrative drugs in the world. QUARTZ. https://qz.com/1967638/pfizer-will-make-15-billion-from-covid-19-vaccine-sales/

Michels, N., Vynckier, L., Moreno, L.A. et al. (2018). Mediation of psychosocial determinants in the relation between socio-economic status and adolescents’ diet quality. Eur J Nutr, 57, 951–963. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-017-1380-8

Mukherjee, S. (2020). How does the coronavirus behave inside a patient? We’ve counted the viral spread across peoples; now we need to count it within people. The New Yorker, April 6, 2020. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/04/06/how-does-the-coronavirus-behave-inside-a-patient?utm_source=onsite-share&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=onsite-share&utm_brand=the-new-yorker

Munshi, R., Hussein, M.H., Toraih, E.A., Elshazli, R.M., Jardak, C., Sultana, N., Youssef, M.R., Omar, M., Attia, A.S., Fawzy, M.S., Killackey, M., Kandil, E., & Duchesne, J. (2020) Vitamin D insufficiency as a potential culprit in critical COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol, 93(2), 733-740. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.26360

Renoud. L, Khouri, C., Revol, B., et al. (2021) Association of Facial Paralysis With mRNA COVID-19 Vaccines: A Disproportionality Analysis Using the World Health Organization Pharmacovigilance Database. JAMA Intern Med. Published online April 27, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.2219

Sallis, R., Young, D. R., Tartof, S.Y., et al. (2021). Physical inactivity is associated with a higher risk for severe COVID-19 outcomes: a study in 48 440 adult patients. British Journal of Sports Medicine. Published Online First: 13 April 2021. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2021-104080

Schöttker, B., Haug, U., Schomburg, L., Köhrle, L., Perna, L., Müller. H., Holleczek, B., & Brenner. H. (2013). Strong associations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels with all-cause, cardiovascular, cancer and respiratory disease mortality in a large cohort study. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 97(4), 782–793 2013; https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.112.047712

Siegel, K.R., McKeever Bullard, K., Imperatore. G., et al. (2016). Association of Higher Consumption of Foods Derived From Subsidized Commodities With Adverse Cardiometabolic Risk Among US Adults. JAMA Intern Med. 176(8), 1124–1132. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2410

Ssentongo P, Ssentongo AE, Heilbrunn ES, Ba DM, Chinchilli VM (2020) Association of cardiovascular disease and 10 other pre-existing comorbidities with COVID-19 mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 15(8): e0238215. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238215

Steenhuysen, J. 2021, Jan 30). Fresh data show toll South African virus variant takes on vaccine efficacy. Accessed January 31, 2021. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-vaccines-variant/fresh-data-show-toll-south-african-virus-variant-takes-on-vaccine-efficacy-idUSKBN29Z0I7

World Health Organization. (2017). Sugary drinks1 – a major contributor to obesity and diabetes. WHO/NMH/PND/16.5 Rev. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/260253/WHO-NMH-PND-16.5Rev.1-eng.pdf?sequence=1

Zimmermann, P. & Curtis, N. (2019). Factors That Influence the Immune Response to Vaccination. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 32(2), 1-50. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00084-18

Why did the CDC mishandle the COVID-19 pandemic response?

Posted: May 10, 2021 Filed under: education, health, Uncategorized | Tags: CDC, COVID-19 1 CommentThe CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) located in Atlanta, George, with a stellar international reputation responded too late and incompetently to the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Although many people blame the Trump administration for the failed response, a significant factor was the risk adverse and politicized CDC.. To understand what actually happened, listen to the superb New York Times podcast with Michael Lewis and read his just published book, The Premonition: A Pandemic Story. The interview and his book should be the first requirement for anyone interested in Public Health careers, government service and public policy.

Listen to the New York Times book review podcast interview: and read the book.

CDC should make COVID-19 vaccine V-safe side effects self-reporting “Opt out” instead of “Opt in”

Posted: February 15, 2021 Filed under: health | Tags: COVID-19, Moderna, Pfizer-BioNTech, side effects, vaccine 14 Comments

At the moment the United States and the rest of the world are participating in an unprecedented experiment of being vaccinated for COVID-19 to end the pandemic without completely knowing long-term risks. The Federal Drug Administration (FDA) has authorized the emergency use for the vaccine based upon clinical trials that showing that the vaccine is highly effective in reducing or preventing COVID-19 disease and morbidity (FDA, 2021). Because it is an experimental procedure, it is necessary to monitor and follow-up everyone who is vaccinated in order to identify possible rare complications that could occur in the future. What has been reported is a very rare complication of anaphylaxis that may occur immediately after administration of the vaccine by Pfizer-BioNTech (4.7 cases per million) and Moderna (2.4 cases per million) (Shimabukuro, Cole, & Su, 2021); however, this data may under report the actual negative side effects. In the recently published prospectively study by Blumenthal et al. (2021) of 64,000 employees associated with Mass General Brigham (MGB) were actively followed through a multipronged approach including email, text message, phone, and smartphone application links. The complication rate of acute allergic reaction rate was 2.1% and the severe anaphylaxis reaction was 247 cases per million. This is 50 times higher than the previously reported results which depended on voluntary reporting instate of active all participants follow-up. Nevertheless, the benefits of vaccination far outweigh the risk of anaphylaxis, which was experienced within the first 15-30 minutes after the vaccination and treatable. What is disturbing is that at this moment, the USA does not have a systematic long-term follow up strategy for all the people who vaccinated to identify possible delayed long-term side effects since it depends upon voluntary reporting, however, rare. Thus, we are all part of an uncontrolled experiment in which I am also participating.

At the age of 76, I choose to be vaccinated after having assessed the risk-benefits reported in the published clinical studies (the possible harm caused by Covid-19 would be significantly worse than the possible harm caused by the short and long term side effects from the vaccine). It was confusing and challenging to figure out where the vaccinations were being offered. Luckily, I searched online to find a location where I could sign up to make an appointment for the first vaccination. After having successfully navigated signing up and getting an appointment for Thursday, I contacted the older couple who live nearby and asked if they already had a vaccination appointment. When they told me that they were unable to find a location, I shared with them the information for signing up on the website.

After having received the vaccination, I installed the V-safe app in my cellphone and answered the questions on the App survey; however, to participate, I had to opt in instead of having to opt out. Later on Thursday, I received the first text message from V-safe to which I responded by answering the short symptom questions. I reported that the site of the vaccination felt sore and tight and whenever I lifted up my left arm, I felt a dull ache and stiffness. It was slightly more uncomfortable than I had experienced two years earlier from a tetanus and diphtheria (Td) vaccine injection. That night I could not sleep on my left side since the deltoid area continued to feel sore and painful to pressure. The next day, I worked and did not look at my text messages. On Saturday morning, I realized that I had not responded to Friday’s check-in text message from V-safe. When I tried to response, the survey link embedded in the text message no longer worked. Thus, my discomfort that continued through Thursday night and Friday was not reported to the CDC.

As I still felt some slight tenderness, I also wondered how the older couple were doing since they had received the vaccine on the same day as I did. I called them to check on how they were doing and see if they had signed up with V-safe. They responded that they were doing well except for some soreness in the upper arm; however, they had not signed up for V-safe.

This experience brought to mind studies finding that when follow-up information depends voluntarily opting in, most people do not opt in. Thus, the follow-up data and reporting of possible negative side effects will be less reliable since it would reflect only a small subset of all the people who received the vaccine and are tech savvy. The CDC needs to revise their tracking strategy so that it is able to survey accurately the occurrence of side effects from everyone who gets vaccinated by enrolling them, unless they choose to opt out.

- Enroll people automatically unless they personally decide to opt-out. The enrollment process should be organized so that when an individual receives the vaccine, they automatically are enrolled. Automatic enrollment leads to much higher participation than a voluntary opt-in approach. The difference in participation has been demonstrated in many settings ranging from organ donations to signing up for 401K retirement plans. For example, in Austria, organ donation is the default option at the time of death, and people must explicitly ‘opt out’ of organ donation. “In these so-called opt-out countries, more than 90% of people register to donate their organs. Yet in countries such as U.S. and Germany, people must explicitly ‘opt in’ if they want to donate their organs when they die. In these opt-in countries, fewer than 15% of people register” (Davidai, Gilovich & Ross, 2012). Similar results have been observed in employees’ enrollment in 401K saving plans (Nash, 2007). For example, in analyses of recent hires by Fortune 500 firms, 85.9% of new hires will participate in a 401 K retirement plan when they are automatically enrolled versus 32.4% if they have to voluntarily enroll (opt –in).

- The V-safe app needs to allow symptom data to be reported after the deadline. There needs to be an option to allow a delayed response. In addition, if the person did not respond to the automatic survey, the person needs to be contacted to identify the cause of the non-response.

- Longterm follow-up to monitor for possible adverse effects needs to be implemented. The minimum follow-up period needs to be two years to be able to monitor possible adverse effects that may be triggered by the vaccines. In theory, this could include “antibody-dependent enhancement” to another virus. This occurs when the immune response that has been previously activated makes the clinical symptoms worse when the person is infected a subsequent time with a different type of virus and that trigger an over-reaction, creating a cytokine storm. For example, when a person gets dengue fever and is infected a second time by a different strain of dengue, the person becomes much sicker the second time (Murphy & Whitehead, 2011). Some researchers are concerned that the vaccine in the future could cause an excessive immune reaction when exposed to another virus.

Without automatic enrollment and follow-up, the short and long-term general public safety data may be unreliable and will not accurately capture the actual frequency of side effects. The reported data may under report the actual risk. When independent researchers investigated medical procedures they often find find the complication rate three-fold higher than the medical staff reported. For example, for endoscopic procedures such as colonoscopies, doctors reported only 31 complications from 6,383 outpatient upper endoscopies and 11,632 outpatient colonoscopies. The actual rate was 134 trips to the emergency room and 76 hospitalizations. This discrepancy occurred because the only incidents reported involved patients who went back to their own doctors. The research did not capture those patients who sought help at other locations or hospitals (Leffler et al., 2010).

The data reported by the cellphone web-based app V-safe may represent possibly only 20% of the people vaccinate, biased to those who are healthier, more affluent, younger, and technologically adept. In order to be able to sign-up for V-safe and respond to the text messages, the person needs to be tech savvy, have a cellphone, and be able to respond to the text message during the same day the message is send.

References

Blumenthal, K.G., Robinson, L.B., Camargo, C.A., et al. (2021). Acute Allergic Reactions to mRNA COVID-19 Vaccines. JAMA. Published online March 08, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.3976

CDC (2021). V-safe After Vaccination Health Checker. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Accessed January 30, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/safety/vsafe.html

Davidai, S., Gilovich, T., & Ross, L. (2012). The meaning of default options for potential organ donors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 15201-15205. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1211695109

FDA (2021). COVID-19 Vaccines. Accessed January 30, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/covid-19-vaccines

Leffler, D.A, Kheraj, R., Garud, S., Neeman, N., Nathanson, L.A., Kelly, C.P., Sawhney, M., Landon, B., Doyle, R., Rosenberg, S., & Aronson, M. (2010). The incidence and cost of unexpected hospital use after scheduled outpatient endoscopy. Arch Intern Medicine, 170(19), 1752-1757. http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=226125

Madrian, B. & Shea, D. (2001). The Power of Suggestion: Inertia in 401(k) Participation and Savings Behavior. ”Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(4), 1149-87. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2696456

Murphy, B.R. & Whitehead, S.S. (2011). Immune response to dengue virus and prospects for a vaccine. Annu Rev Immunol., 29, 587-619. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101315

Nash, B. J. (2007). Opt in or opt out? Automatic enrollment increases 401(k) participation. Region focus, 28-31. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/6670505.pdf

Shimabukuro, T.T., Cole, M., & Su, J.R. (2021) Reports of Anaphylaxis after Receipt of mRNA COVID-19 Vaccines in the US—December 14, 2020-January 18, 2021. JAMA. Published online February 12, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.1967

Do nose breathing FIRST in the age of COVID-19

Posted: May 30, 2020 Filed under: Breathing/respiration, health, self-healing, Uncategorized | Tags: anxiety, COVID-19, HRV, nasal breathing, respiration 4 Comments

Breathing affects every cell of our body and should be the first intervention strategy to improve physical and mental well-being (Peper & Tibbetts, 1994). Breathing patterns are much more subtle than indicated by the respiratory function tests (spirometry, lung capacity, airway resistance, diffusing capacity and blood gas analysis) or commonly monitored in medicine and psychology (breathing rate, tidal volume, peak flow, oxygen saturation, end-tidal carbon dioxide) (Gibson, Loddenkemper, Sibille & Lundback, 2019).

When a person feels safe, healthy and peaceful, the breathing is effortless and the breath flows in and out of the nose without awareness. Functional and dysfunctional breathing patterns includes an assessment of the whole body pattern by which breathing occurs such as nose versus mouth breathing, alternation of nasal patency, the rate of air flow rate during inhalation and exhalation, the length of time during inhalation and exhalation, the post exhalation pause time. the pattern of transition between inhaling and exhaling, the location and timing of expansion in the truck, the range of diaphragmatic movement, and the subjective quality of breathing effort (Gilbert, 2019; Peper, Gilbert, Harvey & Lin, 2015; Nestor, 2020).

Breathing patterns affect sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems (Levin & Swoap, 2019). Inhaling tends to activate the sympathetic nervous system (fight/flight response) while exhaling activates the parasympathetic nervous system (rest and repair response) (Lehrer & Gevirtz, 2014). To observe how breathing affects your heart rate, monitor your pulse from either the radial artery in the wrist or the carotid artery in your neck as shown in Figure 1 and practice the following.

After sensing the baseline rate of your pulse, continue to feel your radial artery pulse in your wrist or at the carotid artery in your neck. Then inhale for the count of four hold for a moment and gently exhale for the count of 5 or 6. Repeat two or three times.

Most people observe that during inhalation, their heart rate increased (sympathetic activation for action) and during exhalation, the heart rate decreases (restoration during safety).

Nearly everyone who is anxious tends to breathe rapidly and shallowly or when stressed, unknowingly gasp or holds their breath–they may even freeze up and blank out (Peper et al, 2016). In addition, many people habitually breathe through their mouth instead of their nose and wake up tired with a dry mouth with bad breath. Mouth breathing combined with chest breathing in the absence of slower diaphragmatic breathing (the lower ribs and abdomen expand during inhalation and constrict during exhalation) is a risk factor for disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome, hypertension, tiredness, anxiety, panic attacks, asthma, dysmenorrhea, epilepsy, cold hands and feet, emphysema, and insomnia. Many of our clients who aware of their dysfunctional breathing patterns and are able to implement effortless breathing report significant reduction in symptoms (Chaitow, Bradley, & Gilbert, 2013; Peper, Mason, Huey, 2017; Peper & Cohen, 2017; Peper, Martinez Aranda, & Moss, 2015).

Breathing is usually overlooked as a first treatment strategy-it is not as glamorous as drugs, surgery or psychotherapy. Teaching breathing takes skill since practitioners needs to be experienced. Namely, they need to be able to demonstrate in action how to breathe effortlessly before teaching it to others. Although it seems unbelievable, a small change in our breathing pattern can have major physical, mental, and emotional effects as can be experienced in the following practice.

Begin by breathing normally and then exhale only 70% of the inhaled air, and inhale normally and again exhale only 70% of the inhaled air. With each exhalation exhale on 70% of the inhaled air. Continue this for 30 seconds. Stop and note how you feel.

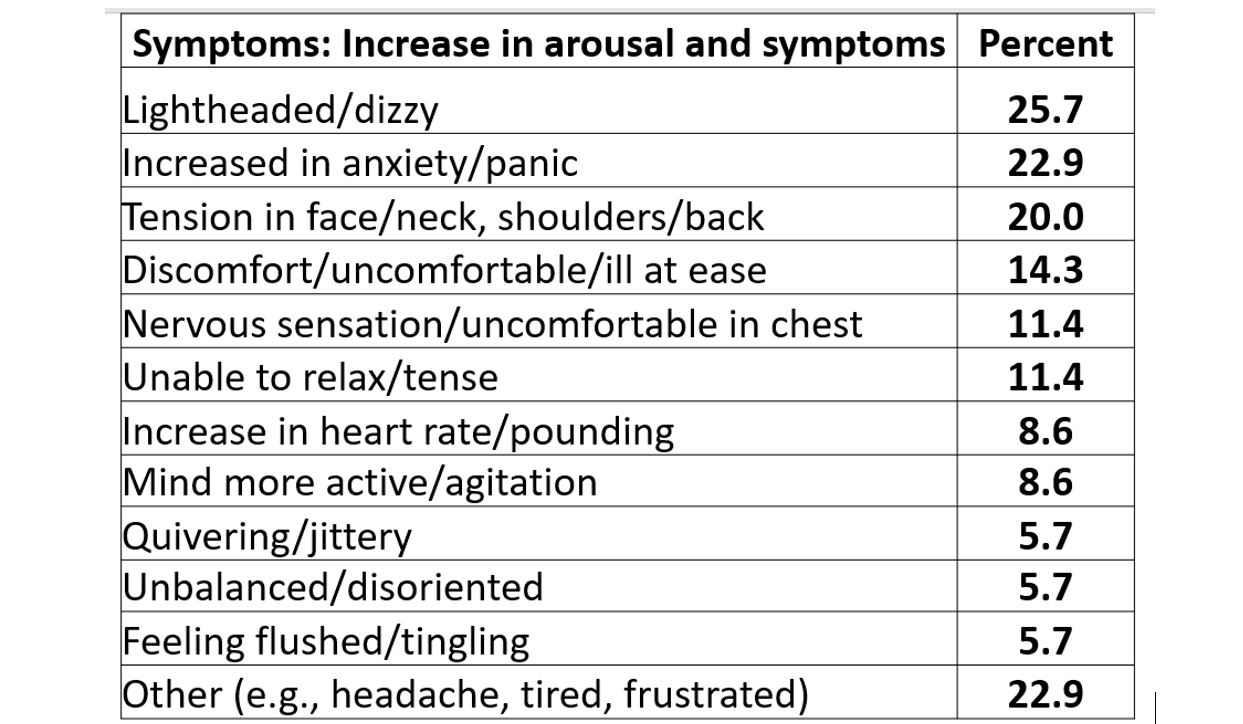

Almost every reports that the 30 seconds feels like a minute and experience some of the following symptoms listed in table 1.

Table 1. Symptoms experienced after 30-45 seconds of sequentially exhaling 70% percent of the inhales air (Peper & MacHose, 1993).

Even though many therapists have long pointed out that breathing is essential, it is usually the forgotten ingredient. It is now being rediscovered in the age of the COVID-19 as respiratory health may reduce the risk of COVID-19.

Simply having very sick patients lie on their side or stomach can improve gas exchange. By lying on your side or prone, breathing is easier as the lung can expand more which appears to reduce the utilization of respirators and intubation (Long & Singh, 2020; Farkas, 2020). This side or prone breathing approach is thousands of years old.

One of the natural and health promoting breathing patterns to promote lung health is to breathe predominantly through the nose. The nose filters, warms, moisturizes and slows the airflow so that airway irritation is reduced. Nasal breathing also increases nitric oxide production that significantly increases oxygen absorption in the body. More importantly for dealing with COVID-19, nitric oxide, produced and released inside the nasal cavities and the lining of the blood vessels, acts as an anti-viral and is a secondary strategy to protect against viral infections (Mehta, Ashkar & Mossman, 2012). During inspiration through the nose, the nitric oxide helps dilate the airways in your lungs and blood vessels (McKeown, 2016).

To increase your health, breathe through your nose, yes, even at night (McKeown, 2020). As you practice this during the day be sure that the lower ribs and abdomen expand during inhalation and decrease in diameter during exhalation. It is breathing without effort although many people will report that it initially feels unnatural. Exhale to the count of about 5 or 6 and inhale (allow the air to flow in) to the count of 4 or 5. Mastering nasal breathing takes practice, practice and practice. See the following for more information.

Watch the Youtube presentation by Patrick McKeown author of the Oxygen Advantage, Practical 40 minute free breathing session with Patrick McKeown to improve respiratory health. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AiwrtgWQeDc&t=680s

Listen to Terry Gross interviewing James Nestor on “How The ‘Lost Art’ Of Breathing Can Impact Sleep And Resilience” on May 27, 2020 on the NPR radio show, Fresh Air.

Look at the Peperperspective blogs that focus on breathing in the age of Covid-19.

Read science writer James Nestor’s book, Breath The new science of a lost art, Breath The new science of a lost art.

References

Allen, R. (2017).The health benefits of nose breathing. Nursing in General Practice.

Christopher, G. (2019). A Guide to Monitoring Respiration. Biofeedback, 47(1), 6-11.

Farkas, J. (2020). PulmCrit – Awake Proning for COVID-19. May 5, 2020.

Long, L. & Singh, S. (2020). COVID-19: Awake Repositioning / Proning. EmDocs

McKeown, P. (2016). Oxygen advantage. New York: William Morrow.

Nestor, James. (2020). Breath The new science of a lost art. New York: Riverhead Books

Reduce initial dose of the virus and optimize your immune system

Posted: April 4, 2020 Filed under: behavior, health, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: coronavirus, COVID-19, immune system, public health, technology 9 CommentsErik Peper and Richard Harvey

Adapted from:Peper, E. & Harvey, R. (September 13, 2020). Reduce Initial Dose of the Virus and Optimize Your Immune System. Townsend Letters-The Examiner of Alternative Medicine, 44. https://www.townsendletter.com/article/reduce-initial-dose-of-the-virus-and-optimize-your-immune-system/

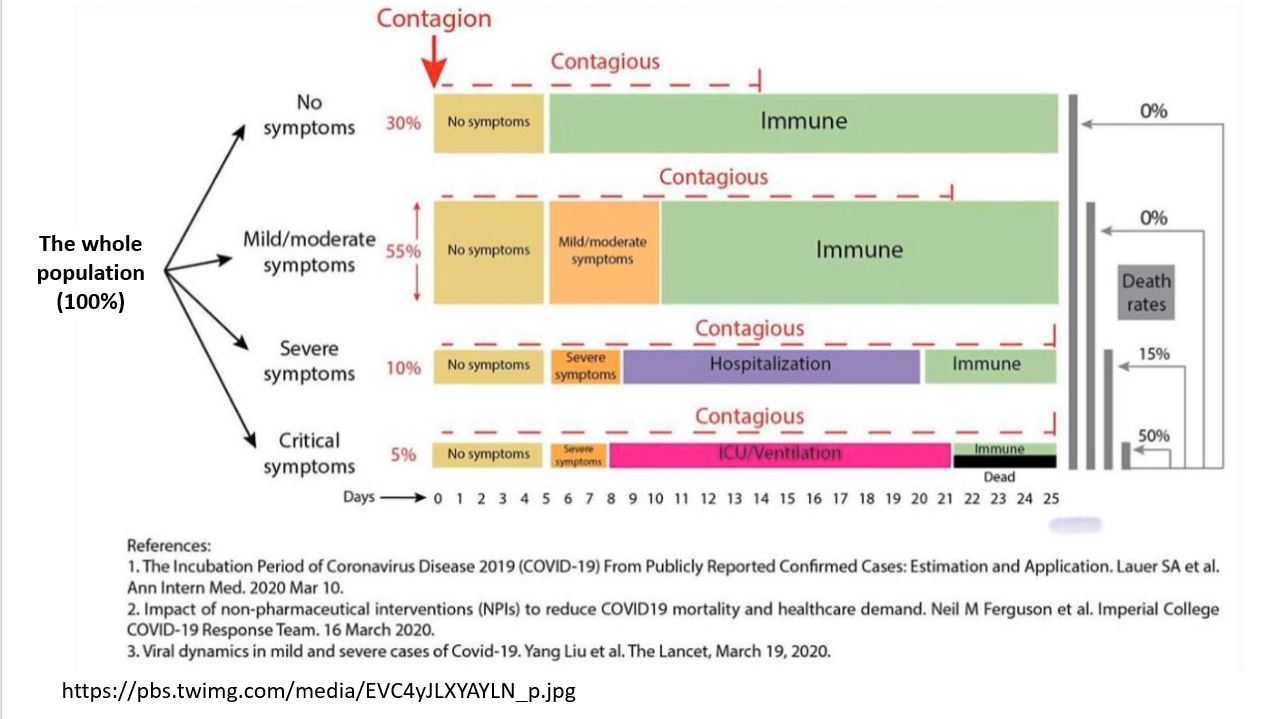

COVID-19 can sometimes overwhelm young and old immune systems and in some cases can result in ‘Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome’ pneumonia and death (CDC, 2020). The risk is greater for older people, and people with serious heart conditions (e.g., heart failure, coronary artery disease, or cardiomyopathies), cancers, obesity, Type 2 diabetes, COPD, chronic kidney disease, hypertension, smoking, immune suppression or other health issues (CDC, 2020a) as well as young people who vape or smoke and those with immunological defects in type I and II interferon production (Gaiha, Cheng, & Halpern-Felsher, 2020; van der Made, 2020). As we age the immune system deteriorates (immunosenescence) that reduces the response of the adaptive immune system that needs to respond to the virus infection (Aw, Silva & Palmer, 2007; Osttan, Monti, Gueresi, et al., 2016). On the other hand, for young people and children the risk is very low and similar for Covid-19 as for seasonal influenza A and B in rates for hospitalization, admission to the intensive care unit, and mechanical ventilator ( Song et al, 2020).

Severity of disease may depend upon initial dose of the virus

In a brilliant article, How does the coronavirus behave inside a patient? We’ve counted the viral spread across peoples; now we need to count it within people, assistant professor of medicine at Columbia University and cancer physician Siddhartha Mukherjee points out that severity of the disease may be related to the initial dose of the virus. Namely, if you receive a very small dose (not too many virus particles), they will infect you; however, the body can activate its immune response to cope with the infection. The low dose exposure act similar to vaccination. If on the other hand you are exposed to a very high dose then your body is overwhelmed with the infection and is unable to respond effectively. Think of a forest fire. A small fire can easily be suppressed since there is enough time to upgrade the fire-fighting resources; however, during a fire-storm with multiple fires occurring at the same time, the fire-fighting resources are overwhelmed and there is not enough time to recruit outside fire-fighting resources.

As Mukherjee points out this dose exposure relationship with illness severity has a long history. For example, before vaccinations for childhood illnesses were available, a child who became infected at the playground usually experienced a mild form of the disease. However, the child’s siblings who were infected at home develop a much more severe form of the disease.

The child infected in the playground most likely received a relatively small dose of the virus over a short time period (viral concentration in the air is low). On the other hand, the siblings who were infected at home by their infected brother or sister received a high concentration of the virus over an extended period which initially overwhelmed their immune system. Higher virus concentration is more likely during the winter and in well insulated/sealed houses where the air is recirculated without going through HEPA or UV filters to sterilize the air. When there is no fresh air to decrease or remove the virus concentration, the risk of severity of illness may be higher (Heid, 2020).

The risk of becoming sick with COVID-19 can only occur if you are exposed to the coronavirus and the competency of your immune system. This can be expressed in the following equation. This equation suggests two strategies to reduce risk: reduce coronavirus load/exposure and strengthen the immune system.

This equation suggests two strategies to reduce risk: reduce coronavirus load/exposure and strengthen the immune system.

How to reduce the coronavirus load/dose of virus exposure

Assume that everyone is contagious even though they may appear healthy. Research suggests that people are already contagious before developing symptoms or are asymptomatic carriers who do not get sick and thereby unknowingly spread the virus (Furukawa, Brooks, Sobel, 2020). Dutch researchers have reported that, “The proportion of pre-symptomatic transmission was 48% for Singapore and 62% for Tianjin, China (Ganyani et al, 2020). Thus, the intervention to isolate people who have symptoms of COVID-19 (fever, dry cough, etc.) most likely will miss the asymptomatic carriers who may infect the community without awareness. Only if you have been tested, do you know if you been exposed or recovered from the virus. To reduce exposure to the virus, avoid the “Three C’s” — closed spaces with poor ventilation, crowded places and close contact—and do the following:

- Follow the public health guidelines:

-

- Social distance (physical distancing while continuing to offer social support)

- Wear a mask and gloves to reduce spreading the virus to others.

- Wash your hands with soap for at least 20 seconds.

- Avoid touching your face to prevent microorganisms and viruses to enter the body through mucosal surfaces of the nose mouth and eyes.

- Clean surfaces which could have been touched by other such as door bell, door knobs, packages.

- Avoid the person’s slipstream that may contain the droplets in the exhaled air. The purpose of social distancing is to have enough distance between you and another person so that the exhaled air of the other person would not reach you. The distance between people depends upon their activities and the direction of airflow.

In a simulation study, Professor Bert Blocken and his colleagues at KU Leuven and Eindhoven University of Technology reported that the plume of the exhaled air that potentially could contain the virus droplets could extend much more than 5 feet. It would depends upon the direction of the wind and whether the person is walking or jogging as show in Figure 1 (Blocken, 2020).

Figure 1. The plume of exhaled droplets that could contain the virus extends behind the person in their slipstream (photo from KU Leuven en TU Eindhoven).

The plume of exhaled droplets in the person’s slipstream may extend more than 15 feet while walking and more than 60 feet while jogging or bicycling. Thus. social distancing under these conditions is much more than 6 feet and it means avoiding their slipstream and staying much further away from the person.

- Increase fresh air to reduce virus concentration. The CDC recommends ventilation with 6 to 12 room air changes per hour for effective air disinfection (Nardell & Nathavitharana, 2020). By increasing the fresh outside air circulation, you dilute the virus concentration that may be shed by an infected asymptomatic or sick person (Qian & Zheng, 2018). Thus, if you are exposed to the virus, you may receive a lower dose and increase the probability that you experience a milder version of the disease. Almost all people who contract COVID-19 are exposed indoors to the virus. In the contact tracing study of 1245 confirmed cases in China, only a single outbreak of two people occurred in an outdoor environment (Qian et al, 2020). To increase fresh air (this assumes that outside air is not polluted), explore the following:

-

- Open the windows to allow cross ventilation through your house or work setting. One of the major reasons that the flu season spikes in the winter is that people congregate indoors to escape weather extremes. People keep their windows closed to conserve heat and reduce heating bill costs. Lack of fresh air circulation increases the viral density and risk of illness severity (Foster, 2014). See the superb graphic illustration by Bartzokas et al (Feb 26, 2021).in the New York Times of virus concentration in schools when the windows are opened. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/02/26/science/reopen-schools-safety-ventilation.html?smid=em-share

- Use an exhaust fans to ventilate a building. By continuously replacing the inside “stale” air with fresh outside air, the concentration of the virus in the air is reduced.

- Use High-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) air purifiers to filter the air within a room. These devices will filter out particles whose diameter is equal to 0.3 µ m. They will not totally filter out the virus; however, they will reduce it.

- Avoid buildings with recycled air unless the heating and air conditioning system (HAC) uses HEPA filters.

- Wear masks to protect other people and your community. The mask will reduce the shedding of the virus to others by people with COVID-19 or those who are asymptomatic carriers. This is superbly illustrated by Prather, Wang, & Schooley (2020) that not masking maximizes exposure, whereas universal masking results in the least exposure.

- Avoid long-term exposure to air pollution. People exposed to high levels of air pollution and fine particulate matter (PM2.5) are more at risk to develop chronic respiratory conditions and COVID-19 death rates. In the 2003 study of SARS, ecologic analysis conducted among 5 regions in China with 100 or more SARS cases showed that case fatality rate increased with the increment of air pollution index (Cui, Zhang, Froines, et al. , 2003). The higher the concentration of fine particulate matter (PM2.5), the higher the death rate (Conticini, Frediani, & Caro, 2020). As researchers, Xiao Wu, Rachel C. Nethery and colleagues (2020) from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health point out, “A small increase in long-term exposure to PM2.5 leads to a large increase in COVID-19 death rate, with the magnitude of increase 20 times that observed for PM2.5 and all cause mortality. The study results underscore the importance of continuing to enforce existing air pollution regulations to protect human health both during and after the COVID-19 crisis.“

- Breathe only through your nose. The nose filters, warms, moisturizes and slows the airflow so that airway irritation is reduced. Nasal breathing increases nitric oxide production that significantly increases oxygen absorption in the body. During inspiration through the nose the nitric oxide helps dilate the airways in your lungs and blood vessels (McKeown, 2016). More importantly for dealing with COVID-19, Nitric Oxide, produced and released inside the nasal cavities and the lining of the blood vessels, acts as an antiviral and a secondary strategy to protect against viral infections (Mehta, Ashkar & Mossman, 2012).

How to strengthen your immune system to fight the virus

The immune system is dynamic and many factors as well as individual differences affect its ability to fight the virus. It is possible that a 40 year-old person may have an immune systems that functions as a 70 year old, while some 70 year-olds have an immune system that function as a 40 year-old. Factors that contribute to immune competence include genetics, aging, previous virus exposure, and lifestyle (Lawton, 2020).

It is estimated that 70-80% mortality caused by Covid-19 occurred in people with comorbidity who are: over 65, male, lower socioeconomic status (SES), non white, overweight/obesity, cardiovascular heart disease, and immunocompromised. Although children comprised only a small percentage of the seriously ill patients, 83% of those children in the intensive care units had comorbidities and 60% were obese. The majority of contributing factors to comorbidities and obesity are the result of economic inequality and life style patterns such as the Western inflammatory diet (Shekerdemian et al, 2020; Zachariah, 2020; Pollan, 2020).

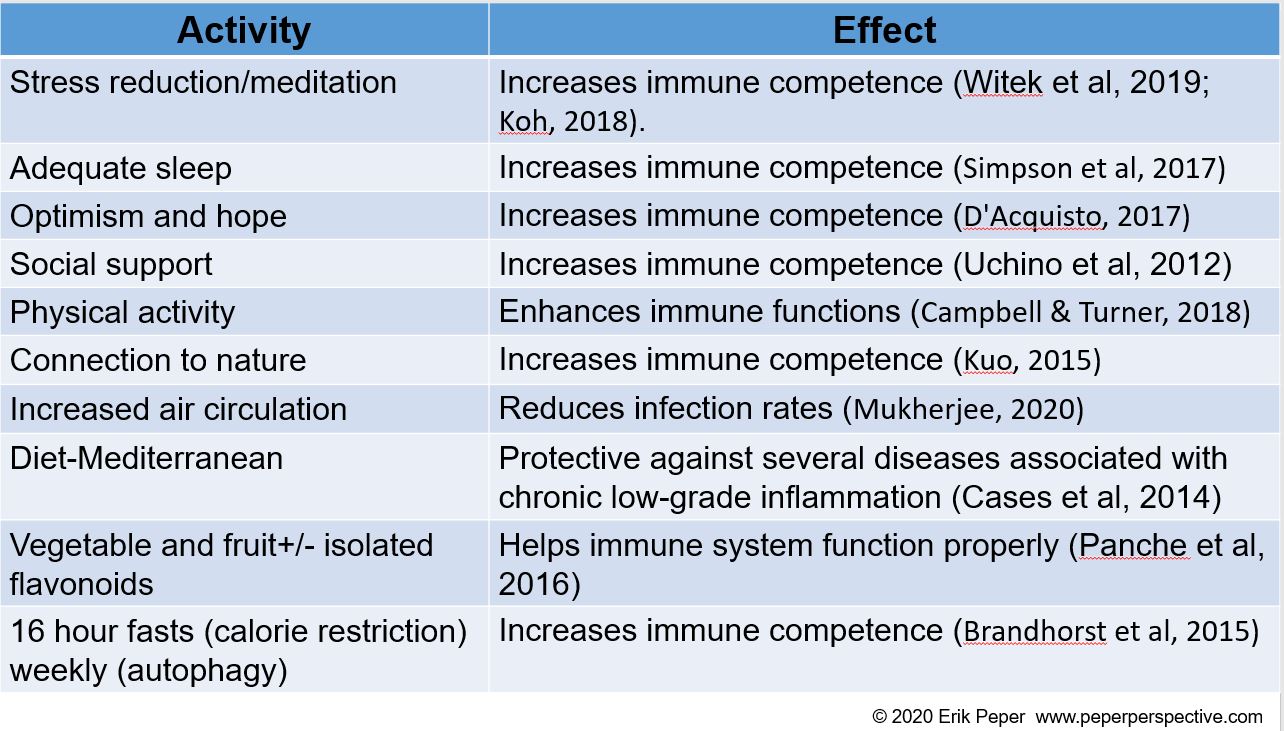

By taking charge of your lifestyle habits through an integrated approach, you may be able to strengthen your immune system (Alschuler et al, 2020; Lawton, 2020). The following tables, adapted from the published articles by Lawton (2020), Alschuler et al, (2020) and Jaffe (2020), list factors that support or decrease the immune system.

Factors that decrease immune competence

Factors that support immune competence

Phytochemicals and vitamins that support immune competence

REFERENCES

Abhanon, T. (2020 March 26). Practical tips how to keep yourself safe.

Foster, H. (2014 December 1). The reason for the season: why flu strikes in winter. SITN Science in the News.

Furukawa, N.W., Brooks, J.T., & Sobel, J. (2020, July). Evidence supporting transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 while presymptomatic or asymptomatic. Emerg Infect Dis. [June3, 2020]. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2607.201595

Ganyani, T., Kremer, C., Chen, D., Torneri, A, Faes, C., Wallinga, J., & Hensm N. (2020). Estimating the generation interval for COVID-19 based on symptom onset data doi:https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.05.20031815

Gaiha, S.M., Cheng, J. & Halpern-Felsher, B. (2020). Association between youth smoking, electronic cigarette use, and coronavirus disease 2019. Journal of Adolescent Health. Published online August 11, 2020. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.07.002

Heid, M. (2020-04-09). The Germ-Cleaning Power of an Open Window. Elemental by Medium.

BMJ Open, 11:e047474. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047474

Jaffe, R. (2020). Reduce risk, boost immunity defense and repair abilities, and stay resilient. PERQUE Integrative Health.

Lawton, G. (2020). You’re only as young as your immune system. New Scientist, 245(3275), 44-48.

Lee, G. Y., & Han, S. N. (2018). The Role of Vitamin E in Immunity. Nutrients, 10(11), 1614.

Malaguarnera L. (2019). Influence of Resveratrol on the Immune Response. Nutrients, 11(5), 946.

Mukherjee, S. (2020). How does the coronavirus behave inside a patient? We’ve counted the viral spread across peoples; now we need to count it within people. The New Yorker, April 6, 2020.

Can changing your breathing pattern reduce coronavirus exposure?

Posted: April 1, 2020 Filed under: Breathing/respiration, health, relaxation, self-healing, Uncategorized | Tags: coronavirus, COVID-19 9 Comments

This blog is based upon our breathing research that began in the 1990s, This research helped identify dysfunctional breathing patterns that could contribute to illness. We developed coaching/teaching strategies with biofeedback to optimize breathing patterns, improve health and performance (Peper and Tibbetts, 1994; Peper, Martinez Aranda and Moss, 2015; Peper, Mason, and Huey, 2017).

For example, people with asthma were taught to reduce their reactivity to cigarette smoke and other airborne irritants (Peper and Tibbitts, 1992; Peper and Tibbetts, 2003). The smoke of cigarettes or vaping spreads out as the person exhales. If the person was infected, the smoke could represent the cloud of viruses that the other people would inhale as is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Vaping by young people in Riga, Latvia (photo by Erik Peper).

To learn how to breathe differently, the participants first learned effortless slow diaphragmatic breathing. Then were taught that the moment they would become aware of an airborne irritant such as cigarette smoke, they would hold their breath and relax their body and move away from the source of the polluted air while exhaling very slowly through their nose. When the air was clearer they would inhale and continue effortless diaphragmatically breathing (Peper and Tibbetts, 1994). From this research we propose that people may reduce exposure to the coronavirus by changing their breathing pattern; however, the first step is prevention by following the recommended public health guidelines.

- Social distancing (physical distancing while continuing to offer social support)

- Washing your hands with soap for at least 20 seconds

- Not touching your face

- Cleaning surfaces which could have been touched by other such as door bell, door knobs, packages.

- Wear a mask to protect other people and your community. The mask will reduce the shedding of the virus to others by people with COVID-19 or those who are asymptomatic carriers.

Reduce your exposure to the virus when near other people by changing your breathing pattern

Normally when startled or surprised, we tend to gasp and inhale air rapidly. When someone sneezes, coughs or exhales near you, we often respond with a slight gasp and inhale their droplets. To reduce inhaling their droplets (which may contain the coronavirus virus), implement the following:

- When a person is getting too close

- Hold your breath with your mouth closed and relax your shoulders (just pause your breathing) as you move away from the person.

- Gently exhale through your nose (do not inhale before exhaling)-just exhale how little or much air you have

- When far enough away, gently inhale through your nose.

- Remember to relax and feel your shoulders drop when holding your breath. It will last for only a few seconds as you move away from the person. Exhale before inhaling through your nose.

- When a person coughs or sneezes

- Hold your breath, rotate you head away from the person and move away from them while exhaling though your nose.

- If you think the droplets of the sneeze or cough have landed on you or your clothing, go home, disrobe outside your house, and put your clothing into the washing machine. Take a shower and wash yourself with soap.

- When passing a person ahead of you or who is approaching you

- Inhale before they are too close and exhale through your nose as you are passing them.

- After you are more than 6 feet away gently inhale through your nose.

- When talking to people outside

- Stand so that the breeze/wind hits both people from the same side so that the exhaled droplets are blown away from both of you (down wind).

These breathing skills seem so simple; however, in our experience with people with asthma and other symptoms, it took practice, practice, and practice to change their automatic breathing patterns. The new pattern is pause (stop) the breath and then exhale through your nose. Remember, this breathing pattern is not forced and with practice it will occur effortlessly.

The following blogs offer instructions for mastering effortless diaphragmatic breathing.

https://peperperspective.com/2018/10/04/breathing-reduces-acid-reflux-and-dysmenorrhea-discomfort/

https://peperperspective.com/2017/03/19/enjoy-sex-breathe-away-the-pain/

https://peperperspective.com/2015/02/18/reduce-hot-flashes-and-premenstrual-symptoms-with-breathing/

https://peperperspective.com/2015/09/25/resolving-pelvic-floor-pain-a-case-report/

References

Peper, E., Mason, L., Huey, C. (2017). Healing irritable bowel syndrome with diaphragmatic breathing. Biofeedback. (45-4). /

Coronavirus risk in context: How worried should you be?

Posted: March 7, 2020 Filed under: behavior, health, Uncategorized | Tags: coronavirus, COVID-19 9 CommentsThe coronavirus which causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) appears to be a highly contagious disease. Some older people and those who are immune compromised are more at risk. The highest risk are for older people who already have cardiovascular, diabetes, respiratory disease, and hypertension. In addition, older men over 65 years are much more at risk; however, many are smokers who have a compromised pulmonary system. Previous meta analysis showed that smoking was consistently associated with higher risk of hospital admissions after influenza infection. Nevertheless, it is reasonable to assume that over time all most all of us will become exposed to the virus, a few will get very sick, and even fewer will die.

The preliminary data suggests that most people who become infected may not even know they are infectious. Make the assumption that everyone could be contagious unless tested for the virus or antibodies to the virus since people appear to be infectious for the first four days before experiencing symptoms.

The absolute risk that one would die of this disease is low although if you do become very sick it is more dangerous than the normal flu; however, the fear of this disease may be out of proportion compared to other health risks. For detailed analysis and graphic summaries see the updated research reports on the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) by Our World in Data and Information is beautiful. These reports make data and research on the world’s largest problems understandable and accessible.

It is worthwhile to look at the absolute risk of COVID-19. To read that more than 332,000 people world wide have died in the last five months is terrifying especially with the increasing death rate in Europe and New York; however, it needs to be understood in context of the size of the population. The epicenter of this disease was Wuhan and Hubei Provence, China with a total population of about 60 million people. Each year about 427,200 people die in the Wuhan and Hubei Province (the annual death rate in China is 7.12 deaths per 1000 people). Without this new viral disease, about 71,200 people would have died during the same two month period. The question that has not been discussed is how much did the total death rate increase. Would it be possible that some of the people who died would have died of other natural causes such as the flu?

The World Health Organization (WHO) and governments around the world should be lauded for their attempt to reduce the spread of the virus. On March 6, 2020, the United States Congress allocated $8. billion dollars to fight and prevent the spread of COVID-19.

This funding will only partially prevent the spread of the virus because some people have no choice but to go to work when they are sick–they do not receive paid sick leave! This is true for about 30 percent of the American workers who have no coverage at work or the millions of self-employed workers (e.g. gig/freelance workers, waiters, cashiers, drivers, nannies, house cleaners).

To reduce the risk of the spreading COVID-19, anyone who feels sick or thinks they have been exposed, should receive paid sick leave so that they can stay home and self-isolate. The paid sick leave should be Federally funded and provide basic income for those whose income would be lost if they did not work. Although it is possible that a few people will cheat and take the paid sick leave when they are well, this is worth the risk to keep the rest of population healthy. To provide possible relief, at the moment the House and Senate are working on a greater than $2 trillion dollar stimulus package.

Personal and government responses to health risks are not always rational.

Funding for health and illness prevention is driven by politics. For example, gun violence results in more than 100,000 people being injured each year and more than 36,000 killed—an average of 100 per day. Gun violence is a much more virulent disease than COVID-19 and more than 1.7 million Americans have died from firearms since 1968.

The Federal Government response to this gun violence epidemic has been minimal. For the first time since 1996 did the 2020 federal budget include $25 million funding for the CDC and NIH to research reducing gun-related deaths and injuries.

It is clear that the government response does not always focuses its resources on what would reduce injury and death rates the most. Look at the difference in the national response to COVID-19 virus that has killed more than 120,000 people in the USA ($8.5 billion for the initial response and then $2 trillion stimulus package) as compared gun violence that kills 36,000 people a year in the USA ($25 million funding to study the causes of gun violence).

Be realistic about the actual risk of COVID-19 without succumbing to fear.

COVID-19 is a pandemic and I expect that 30% to 70% of us will be infected this year. Hopefully, in the next 18 months an effective vaccine will be developed. In the mean time, there is no known treatment, thus optimize health and reduce the exposure to the coronavirus.

- How to reduce exposure to the coronavirus

- Optimize your health and immune function by eating healthy, getting enough sleep, enjoying some exercise/movement and reducing stress.

- Increase social distance when with other people–greet people by staying separated by at least six feet or more from each other instead of a handshake or a kiss on the cheek.

- Wash your hands after touching surfaces that others may have touched or after going out for shopping, work, pleasure and/or meeting other people.

- Avoid touching your face especially your mouth, nose and eyes.

- Sanitize hard surfaces. Malia Jones, PhD, MPH points out that you can make your own inexpensive antimicrobial spray by mixing 1 part household bleach to 99 parts cold tap water. Spray this on surfaces and leave for 10-30 minutes. (Note: this is bleach. It will ruin your sofa).

- If you think you have the disease or have symptoms, contact your healthcare provider. Wear a mask and self-isolate to reduce spreading the virus to others.

- Increase fresh air circulation and avoid room that have poor ventilation.

- Reliable information about COVID-19

- World Health Organization (WHO): https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public

- Centers for Disease Control (CDC): https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/about/index.html

- Graphic representation of the background of the COVID-19 infection and relationship to other diseases

- Summary of what is the corona virus: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus#citation

- Graphic representation of coronavirus in context to other diseases: https://informationisbeautiful.net/visualizations/covid-19-coronavirus-infographic-datapack/

- Accurate information on number of infections, new cases and deaths: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/

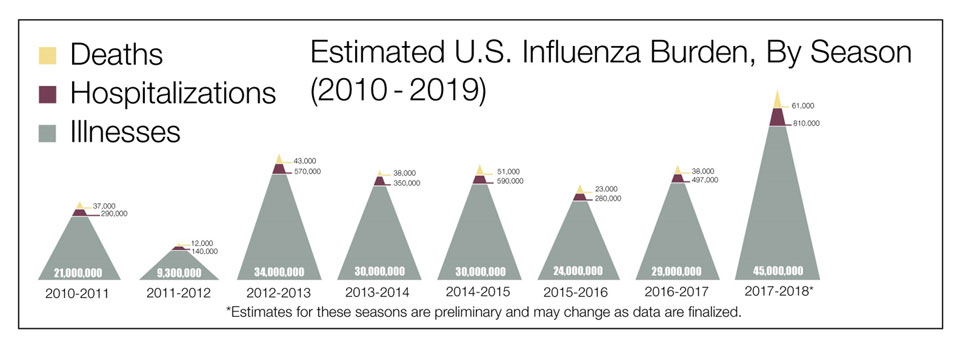

To make sense of the danger of COVID-19, look at it in context to the flu. The risk is the greatest for people with co-morbidity (obesity, diabetes, emphysema, immune suppressed illnesses, and people who smoke and vape). While the risk for young people and children is no different for being infected with Covid-19 or influensa A and B in hospitalization rates, intensive care unit admission rates, and mechanical ventilator (Song et al. 2020). Depending upon the severity the flu, 9,000,000 to 45,000,000 people get sick from flu and between 12,000 to 61,000 die from its complications as shown below in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The estimated U.S. influenza burden by year (from: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/burden/index.html)

Figure 1. The estimated U.S. influenza burden by year (from: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/burden/index.html)