Healing a Shoulder/Chest Injury

Posted: August 14, 2023 Filed under: behavior, biofeedback, Breathing/respiration, emotions, Exercise/movement, healing, Neck and shoulder discomfort, Pain/discomfort, relaxation, self-healing, Uncategorized | Tags: electromyograph, guided imagery, shoulder pain Leave a commentAdapted from Peper, E. & Fuhs, M. (2004). Applied psychophysiology for therapeutic use: Healing a shoulder injury, Biofeedback, 32(2), 11-18.

“It has been an occurrence of the third dimension for me! How come my pain — that lasted for more than 10 days and was still so strong that I really had difficulties in breathing, couldn’t laugh without pain nor move my arm not even to fulfil my daily routines such as dressing and eating — disappeared within one single session of 20 minutes? And not only that, I was able to freely rotate my arm as if it had never been injured before.” —23 year old woman

The participant T., aged 23, was a psychology student who participated in an educational workshop for Healthy Computing. She volunteered to be a subject for a surface electromyographic (SEMG) monitoring and feedback demonstration. Ten days prior to this workshop, she had a severe skiing accident. She described the accident as follows:

I went skiing and may be I had too much snow in my ski-binding and while turning, I slipped out of my binding and fell head first down into the hill. As I fell, I landed on my ski pole which hit my left upper chest and breast area. Afterwards, my head was humming and I assumed that I had a light concussion. I stopped skiing and stayed in bed for a while. The next day it started hurting and I couldn’t turn my head or put my shoulders back (they were rotated forward). Also, I couldn’t ski as I was not able to look down to my feet–my muscles were too contracted and I felt searing pain whenever I moved. I hoped that it would go away however, the pain and left forward shoulder rotation stayed.

Assessment

Observation and Palpation

T.´s left shoulder was rolled forward (adducted and in internal rotation). She was not able to breathe or laugh without pain or move her arm freely. All movements in vertical and horizontal directions and rotations were restricted by at least 50 % as compared to her right arm (limitations in shoulder extension, flexion and external rotation). Also, her hands were ice-cold and she breathed very shallowly and rapidly in her chest. She was not able to stand in an upright position or sit in a comfortable position without maintaining her left upper extremity in a protected position. Her left shoulder blade (scapula) was winging.

After visually observing her, the instructor placed his left hand on her left shoulder and pectoralis muscles and his right hand on the back of her shoulder. Using palpation and anchoring her back with his leg so that she could not rotate her trunk, he explored the existing range of shoulder movement. He also attempted to rotate the left shoulder outward and back–not by forcing or pulling—but by very gentle traction. No change in mobility was observed and the pectoralis muscle felt tight (SEMG monitoring is helpful to the therapist during such a diagnostic assessment by helping to identify the person’s reactivity and avoiding to evoke and condition even more bracing). T. reported afterwards that she was very scared by this assessment because there was one point in the back which was highly reactive to touch. T. appeared to tighten automatically out of fear and trigger a general flexor contraction pattern—a process that commonly occurs if a person is guarding an area.

Often a traumatic injury first induces a general shock that triggers an automatic freeze and fear reaction. Therefore, an intervention needed to be developed that did not trigger vigilance or fear and thereby allowed the muscle to relax. If pain is experienced or increased, it is another negative reinforcement for generalizing guarding and bracing and tightening the muscles. This guarding decreases mobility – a common reaction that may occur when health professionals in the process of assessment increase the client’s discomfort. T.’s vigilance was also “telegraphed” to the therapist by her ice-cold hands and very shallow chest breathing. Therefore, it was important to increase her comfort level and to not induce any further pain. We hypothesized that only if she felt safe it would be possible for her muscle tension to decrease and thereby increase her mobility.

Underlying concept: The very cold hands and shallow breathing probably indicated excessive vigilance and arousal—a possible indicator of a catabolic state that could limit regeneration. The chronic cold hands most likely implied that she was very sensitive to other people’s emotions and continuously searches/scans the environment for threats. In addition, she indicated that she liked to do/perform her best which induced more anxiety and fear of judgement.

Single Channel Surface Electromyographic (SEMG)Assessment

The triode electrode with sensor was placed over the left pectoralis muscle area as shown in Figure 1. The equipment was a MyoTrac™ produced by Thought Technology Ltd. which is a small portable SEMG with the preamplifiers at the triode sensor to eliminate electrode lead and movement artefacts (Peper & Gibney, 2006). Such a device is an inexpensive option for people who may use biofeedback for demonstrating and teaching awareness and control over muscle tension from a single electrode location.

Figure 1. Location of the Triode electrode placement on the left pectoralis muscle area of another participant.

The MyoTrac was placed on a table within view, so that the therapist and the subject could simultaneously see the visual feedback signal and observe what was going on as well as demonstrate expected changes. The feedback was used for T. as a tool to see if she could reduce her SEMG activity. It was also used by the therapist to guide his interventions: To keep the SEMG activity low and to stop any intervention that would increase the SEMG activity as this would prevent bracing as a possible reaction to, or anticipation of, pain.

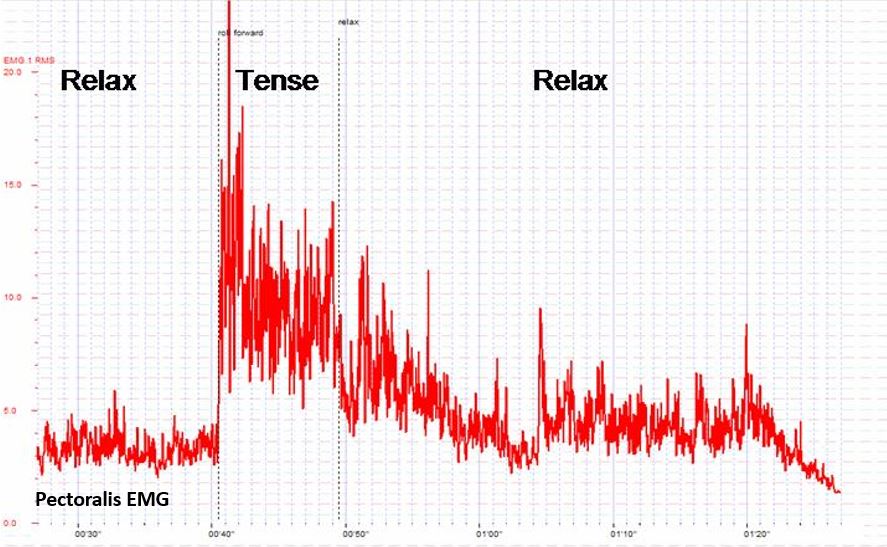

1. Assessment of Muscle Reactivity. After the electrode was attached on her pectoralis muscle and with her arm resting on her lap, she was asked to roll her left shoulder slightly more forward, hold the tension for the count of 10 and then let go and relax. Even with feedback, the muscle activity stayed high and did not relax and return to a lower level of activity as shown in Figure 2. This lack of return to baseline is often a diagnostic indicator of muscle irritability or injury (Sella, 1998; Sella, 2006). If the muscle does not relax immediately after contraction, movement or exercise should not be prescribed, since it may aggravate the injury. Instead, the person first needs to learn how to relax and then learn how to relax between activation and tensing of the muscle. The general observation of T. was that at the initiation of any movement (active or passive) muscle tension increased and did not return to baseline for more than two minutes.

Figure 2. Simulation of the effect on the pectoralis sEMG (this is a recording from another subject who showed a similar response pattern that was visually observed from T. with the Myotrac). After the muscle is contracted it takes a long time to return to baseline level

2. Exploration. Self-exploration with feedback was encouraged. T. was instructed to let go of muscle tension in her left shoulder girdle. In addition the therapist tried to induce her letting go by gently and passively rocking her left arm. The increased SEMG activity and the protective bracing in her shoulder showed that she couldn’t reduce the muscle tension. Each time her arm was moved, however slightly, she helped with the movement and kept control. In addition, T. was asked to reduce the muscle tension using the biofeedback signal; again she was not able to reduce her muscle tension with feedback.

3. Passive Stretch and Movements. The next step was to passively stretch the pectoralis muscle by holding the shoulder between both hands and very gently externally rotate the shoulder — a process derived from the Alexander technique (Barlow, 1991). Each time the instructor attempted to rotate her shoulder, the SEMG increased and T. reported an increased fear of pain. T.’s SEMG response most likely consisted of the following components:

- Movement induced pain

- Increased splinting and guarding

- Increased arousal/vigilance to perform well

These three assessment and self-regulation procedures were unsuccessful in reducing muscle tension or increasing shoulder movement. This suggested that another therapeutic intervention would need to be developed to allow the left pectoralis area to relax. The SEMG could be used as an indicator whether the intervention was successful as indicated by a reduction in SEMG activity. Finally, the inability to relax after tightening (bracing and splinting) probably aggravated her discomfort.

Multiple levels of injury: The obvious injury and discomfort was due to her left chest wall being hit by the ski pole. She then guarded the area by bracing the muscles to protect it which limited movement. The guarding tightened the muscles and limited blood circulation and lymphatic flow which increased local ischemia, irritation and pain. This led to a self-perpetuating cycle: Pain triggers guarding and guarding increases pain and impedes self-healing.

As the SEMG and passive stretching assessment were performed, the therapist concurrently discussed the pain process. Namely, from this perspective, there were at least two types of pains:

- Pain caused by the physiological injury

- Pain as the result of guarding

The pain from the guarding is similar to having exercised for a long time after not having exercised. The next day you feel sore. However, if you feel sore, you know that it was due to the exercise therefore it is defined as a good pain. In T.’s case, the pain indicated that something was wrong and did not heal and therefore she would need to protect it. We discussed this process as a way to use cognitive reframing to change her attitude toward guarding and pain.

Rationale: The intention was to interrupt her negative image of pain that acted as a post hypnotic suggestion. The objective was to change her image and thoughts from “pain indicates the muscle is damaged” to “pain indicates the muscle has worked too hard and long and needs time to regenerate.”

Treatment interventions

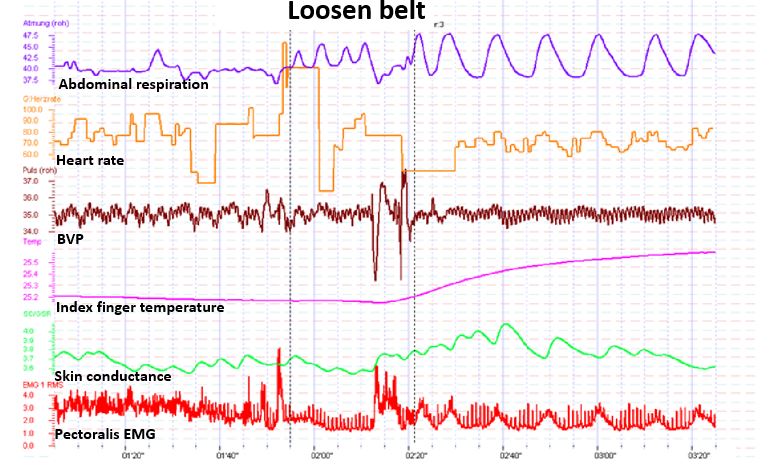

The initial intervention focused upon shifting shallow thoracic breathing to diaphragmatic breathing. Generally, when people breathe rapidly and predominantly in their chest, they usually tighten their neck and shoulder muscles during inhalation. One of the reasons T. breathed in her chest was that her clothing–very tight jeans–constricted her waist (MacHose & Peper, 1991; Peper et al., 2015). This breathing pattern probably contributed to sub-clinical hyperventilation and was part of a fear or flexor response pattern. When she loosened the upper buttons of her jeans and allowed her stomach to expand her pectoralis muscle relaxed as she breathed as shown in Figure 3. As she began to breathe in this pattern, each time she exhaled her pectoralis muscle tension decreased.

Figure 3. Illustration of the effect of loosening tight waist constriction (eliminating designer’s jean syndrome) on blood flow and pectoralis sEMG. Abdominal breathing became possible and finger temerature increased (this recording is from another subject whose physiological responses were similar to that was observed with the Myotrac from T.)

Following the demonstration that breathing significantly lowered her chest muscle tension, the discussion focussed on the importance of effortless diaphragmatic breathing for health and reduction of vigilance. Being awkward and uncomfortable at loosening her pants, she struggled with allowing her abdomen to expand and her pants to be looser because she thought that she looked much more attractive in tight clothing. Yet, she agreed that her boy friend would love her regardless whether she wore loose or tight clothing. To encourage an acceptance for wearing looser clothing and thereby permit diaphragmatic breathing during the day, an informal discussion focused on “designer jeans syndrome” (chest breathing induced by tight clothing) with humorous examples such as discussing the name of the room that is located on top of the stairs in the Victorian houses in San Francisco. It is called the fainting room–in the 19th century women who wore corsets and had to climb the stairs would have to breathe rapidly and then would faint when they reached the top of the stairs (Peper, 1990).

Rationale: Rapid shallow chest breathing can induce a catabolic state that inhibits healing while diaphragmatic breathing may induce an anabolic state that promotes regeneration. Moreover, effortless diaphragmatic breathing would increase respiratory sinus arhythmia (RSA)–heart rate variability linked to breathing– and thereby facilitate sympathetic-parasympathetic balance that would promote self-healing.

The discussion included the use of the YES set which meant asking a person questions in such a way that she/he answers the question with YES. When a person answers YES at least three times in a row rapport is often facilitated (Erikson, 1983, pp. 237-238). Questions were framed in such a way that the client would answer with YES. For example, if the therapist thought the person did not do their homework, a yes question could be framed as, “It must have been difficult to find time to do the homework this week?” In T.’s case, the therapist said, “I see, you would rather wear tight clothing than allow your shoulder to heal.” She answered, “Yes.” This was the expected answer, however, the question was framed in an intuitive guess on the therapist’s part. Nevertheless, the strategy would have been successful either way because if she had answered “No,” it would have broken the “Yes: set, but she would then be committed to change her clothing.

Throughout this discussion, the therapist placed his left hand on her abdomen over her belly button and overtly and covertly guided her breathing movement. As she exhaled, he pressed gently on her abdomen; as she inhaled he drew his hand away–as if her abdomen was like a balloon that inflated during inhalation and deflated during exhalation. To enhance learning diaphragmatic breathing and slower exhalation, the therapist covertly breathed at the same rhythm and gently exhaled as she exhaled while allowing the breathing movement to be mainly in his abdomen. In this process, learning occurred without demand for performance and she could imitate the breathing process that was covertly modelled by the therapist.

The Change

The central observation was that each time she tried to relax or do something, she would slight brace which increased her pectoralis SEMG activity. The chronic tension from guarding probably induced localized ischemia, inhibited lymphatic flow and drainage, and reduced blood circulation which would increase tissue irritation. Whenever the therapist began to move her arm, she would anticipate and try to help with the movement. Overall she was vigilant (also indicated by her very cold hands) and wanted to perform very well (a possible need for approval). Her muscle bracing and helping with movement was reframed as a combined activity that consisted of guarding to prevent further injury and as a compliment that she would like to perform well.

Labelling her activity as a “compliment” was part of a continuing YES set approach. The therapist was deliberately framing whatever happened as adaptive behaviour, with positive intent. Further, if one tries and does something with too much effort while being vigilant, the arousal would probably induce hand cooling. If the activity can be performed with passive attention, then increased blood flow and warmth may occur. The therapeutic challenge was how to reduce vigilance, perfectionism and guarding so that the muscles that were guarding the traumatized area would relax.

Therapeutic concept: If a direct approach does not work, an indirect approach needs to be employed. Through an indirect approach, the person experiences a change without trying to focus on doing or achieving it. Underlying this approach is the guideline: If something does not work, try it once more and then if it does not work, do something completely different. This is analogous to sexual arousal: If you demand from a male to have an erection: The more performance you demand the less likely will there be success. On the other hand, if you remove the demand for performance and allow the person to become interested and thereby feel an erotic experience an erection may occur without effort.

The shift to an indirect intervention was done through active somatic visualization. T. was encouraged to visualize and remember a positive image or memory from her past. She chose a memory of a time when she was in Paris with her grandmother. While T. visualized being with her grandmother, the therapist asked another older women participant to help and hold T’s right hand in a grandmother-like way as if she was her grandmother. The “grandmother” then moved T.’s hand in a playful way as if dancing with T.’s right arm. Through this kinesthetic experience, T. became more and more absorbed in her memory experience. At the same time, T´s left hand was being held and gently rocked by the therapist. During this gentle rocking, the SEMG activity decreased completely in her left pectoralis area. The therapist used the SEMG feedback to guide him in the gentle rocking motion of T.’s left arm and very slowly increased the range of her arm and shoulder motion. Gentle movement was done only as long as the SEMG activity did not increase. It allowed the muscle to stay relaxed and facilitated the experience of trust. The following is T. report two days later of what happened.

“Initially it was very difficult for me to let go of control because I found this idea somewhat strange and I was puzzled. I expected the therapist to intervene and I felt frightened. The therapist’s soft and gentle touch and his very soft voice in this kind of meditation helped me to let go of control and I was surprised about my own courage to give myself into the process without knowing what would happen next.”

Rationale: Every corresponding thought and emotion has an associated body response and every body response has an associated mental/emotional response (Green & Green, 1977; Green, 1999). Therefore, an image and experience of a happy and safe past memory will allow the body to evoke the same state and vigilance can be abated. The intensity of the experience is increased when multi-sensory cues are included such as actual handholding. The more senses are involved, the more the experience can become real. In addition, the tactile sensation of feeling the grandmother’s hand diverted her attention away from her shoulder into her hand and thereby reduced her active efforts of trying to relax the shoulder and pectoralis area. Doing something she did not expect to happen also helped her loose control – an implicit confusion approach.

SEMG feedback was used as the guide for controlling the movement. The therapist gently increased the range of the movements in abduction and external rotation directions while continuously rocking her arm until her injured arm was able to move unrestricted in full range of motion. The arm and shoulder relaxation and continuous subtle movement without evoking any SEMG activation facilitated blood flow and lymphatic drainage which probably reduced congestion. After a few minutes, the therapist gently dropped her arm on her lap. After her arm was resting on her lap, she reported that it felt very heavy and relaxed and that she didn’t feel any pain. However, she initially didn’t really realize that her mobility had increased dramatically.

Rationale: When previous movements that had been associated with pain are linked to an experience of pleasure, the movement is often easier. The conditioned muscle bracing patterns associated with anticipation of pain and/or concern for improvement/results are reduced.

Process to deepen and generalize the relaxation and breathing. She was asked to imagine breathing the air down and through her arms and legs–a strategy that she could then do at home with her boyfriend. We wanted to involve another person because it is often difficult to do homework practices without striving and concern for results and focussing on the area of discomfort. Her response to asking if her boyfriend would help was an automatic “naturally” (the continuation of the YES set). With her agreement, we role played how her boyfriend was to encourage diaphragmatic breathing. He was to gently stroke down her legs as she exhaled. She could then just focus on the sensations and allow the air to flow down her legs. Then, while she continued to breathe effortlessly, he would gently rock and move her arm.

To be sure that she knew how to give the instructions, the therapist role played her boyfriend and then asked her to rock his arm so that she would know how to teach her boy friend how to move her arm. The therapist sat on her left side, and, as she now held his right arm and gently rocked it with her left arm, the therapist gently moved backwards. This meant that she externally rotated her left arm and shoulder more and more. He moved in such a way that in the process of rocking his arm, she moved her “previously injured shoulder” in all directions (up, down, forward and backwards) and was unaware that she could move her arm and shoulder as she did not experience any discomfort. Afterwards, we shared our observations and she was asked to move her arm and shoulder. She moved it without any restrictions or discomfort.

Rationale: By focusing outside herself and not being concerned about herself, she did not think of herself or of trying to move her arm and shoulder. Hence, she did not evoke the anticipatory guarding and thus significantly increased her flexibility.

Process of acceptance. Often after an injury, we are frustrated with our bodies. This frustration may interfere with healing. Therefore, the session concluded by asking her to be appreciative of her shoulder and arm. She was asked to think of all the positive things her shoulder, chest and arm have done for her in the past instead of the many limitations and pains caused by the injury. Instead of being angry at her shoulder that it had not healed or restricted her movement, we suggested that she should appreciate her shoulder and pectoralis area for all it had done without her awareness such as: How the shoulder moved her arm during love-making, how without complaining her shoulder moved during walking, writing, skiing, eating, etc., and how many times in the past she had abused her shoulder without giving it proper respect and appreciation. This process reframes the way one symbolically relates to the injured area. Every thought of discomfort or negative judgement becomes the trigger and is transformed into breathing lower and slower and evokes an appreciation of the positive nice things her shoulder has done for her in the past.

Rationale: When injured we often evoke negative mental and emotional images which become post- hypnotic suggestions. Those negative thoughts, images and emotions interfere with healing while positive thoughts, images and emotions tend to promote healing. A possible energetic process that occurs when injured is that we withdraw awareness/ consciousness from the injured area which reduces blood and lymph circulation. Caring and positive feelings about an area tends to increase blood flow and warmth (a heart-warming experience) and promotes healing.

RESULTS

She left the initial session without any pain and with total range of motion. At the two week follow-up she reported continued pain relief and complete range of motion. T.s reflection of the experience was:

“I really was not aware that I could move my arm freely like before the accident, I was just feeling a kind of trance and was happy to not feel any pain and to feel much more upright than before. Then I watched the faces of the two other therapists who sat there with big eyes and a grin on their face and then become aware of my own arms position which was rotated backwards and up, a movement that was impossible to do before. I remember this evening that I left with this feeling of trance and that I often tried to go back to my collapsed posture but this was not possible anymore and I felt very tall and straight. Now two weeks later I still feel like that and know that I had an amazing experience which I will store in my brain!

My father who is an orthopedic surgeon tested me and found out, that I had hurt my rib. He said that I have a contusion and it will go away in a few weeks. Before this experience, I would say that he was not open to Biofeedback. However he was so captivated by my experiences that he spontaneously promised me to pay for my own biofeedback equipment and to support me with my educational program and even offered me a job in his practice to do this work!”

Psychophysiological Follow-up: 3 Weeks Later

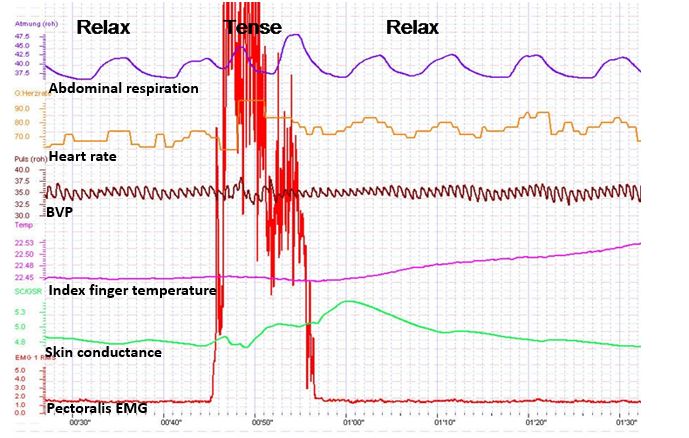

The physiological assessment included monitoring thoracic and abdominal breathing patterns, blood volume pulse, heart rate and SEMG from her left pectoralis muscle while she was asked to roll her left shoulder forward (adducted and internally rotated) for the count of 10 and then relax. The physiological recording showed that she breathed more diaphragmatically and that her pectoralis muscle relaxed and returned directly to baseline after rotation as shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4. Physiological profile during the rolling left shoulder forward (tense) and relaxing at thethree week follow-up. Note that the pectoralis sEMG activity returned rapidly to baseline after contracting and her breathing pattern is abdomninal and slower.

Summary

This case example demonstrates the usefulness of a simple one-channel SEMG biofeedback device to guide the interventions during assessment and treatment. It suggests that the therapist and client can use the SEMG activity as an indicator of guarding–a visual representation of the subjective experience of fear, pain and range of mobility–that can be evoked during assessment and therapeutic interventions. The anticipation of increased pain commonly occurs during diagnosis and treatment and often becomes an obstacle for healing because increased pain may increase anticipation of pain and trigger even more bracing. To avoid triggering this vicious circle of guarding/fear, the feedback signal allows the therapist and the client to explore strategies that reduce muscle activity by indirect interventions.

By using an indirect approach that the client may not expect, the interventions shift the focus of attention and striving and may allow increased freedom and relaxation. The biofeedback signal may guide the therapeutic process to reduce the patterns of fear, panic, and bracing that are commonly associated with injury and illnesses. Once this excessive sympathetic activity is reduced, the actual pathophysiology may become obvious (in most cases is much less then before) and the healing process may be accelerated. This case description may offer an approach in diagnosis and treatment for many therapists and open a door for a gentle, painless and yet successful way of treatment and encourage therapists to be creative and use both experience/technique and intuition.

For additional intervention approaches see the following two blogs.

References

Barlow, W. (1991). The Alexander technique: How to use your body without stress. Rochester, VT: Healing Arts Press https://www.amazon.com/Alexander-Technique-Your-without-Stress/dp/0892813857#:~:text=Barlow%2C%20the%20foremost%20exponent%20and,and%20movement%20in%20everyday%20activities.

Erikson, M. H. (1983). Healing in hypnosis, volume 1 (Edited by E. L. Rossi, M. O. Ryan, M. & F. A. Sharp). New York: Irvington Publishers, Inc.. https://www.amazon.com/Hypnosis-Seminars-Workshops-Lectures-Erickson/dp/0829007393/ref=sr_1_1?keywords=9780829007398&linkCode=qs&qid=1692038804&s=books&sr=1-1

Green, E. (1999). Psychophysical Principal. Accessed August 14, 2023 https://www.elmergreenfoundation.org/psychophysiological-principal/

Green, E., & Green, A. (1977). Beyond biofeedback. New York:

Delacorte Press/Seymour. https://elmergreenfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Beyond-Biofeedback-Green-Green-Searchable.pdf

MacHose, M., & Peper, E. (1991). The effect of clothing on inhalation volume. Biofeedback and Self-Regulation. 16(3), 261-265. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01000020

Peper, E. (1990). Breathing for health. Montreal: Thought Technology Ltd.

Peper, E. & Gibney, K.H. (2006). Muscle biofeedback at the computer-A manual to prevent repetitive strain injury (RSI) by taking the guesswwork out of assessment, monitoring and training. Biofeedback Foundation of Europe. https://thoughttechnology.com/muscle-biofeedback-at-the-computer-book-t2245/

Peper, E., Gilbert, C.D., Harvey, R. & Lin, I-M. (2015). Did you ask about abdominal surgery or injury? A learned disuse risk factor for breathing dysfunction. Biofeedback. 34(4), 173-179. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-43.4.06

Sella, G. E. (2006). SEMG: Objective methodology in muscular dysfunction investigation and rehabilitation. Weiner’s pain management: A practical guide for clinicians, CRC Press, 645-662. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.1201/b14253-45/semg-objective-methodology-muscular-dysfunction-investigation-rehabilitation-gabriel-sella

Sella, G. E. (1998). Towards an Integrated Approach of sEMG Utilization: Quantative Protocols of Assessment and Biofeedback. Electromyography: Applications in Physical Medicine. Thought Technology, 13. https://www.bfe.org/protocol/pro13eng.htm

[1] We thank Theresa Stockinger for her significant contribution and Candy Frobish for her helpful comments.

Freeing the neck and shoulders*

Posted: April 6, 2017 Filed under: Neck and shoulder discomfort, self-healing, Uncategorized | Tags: computer, flexibility, Holistic health, neck pain, relaxation, repetitive strain injurey, shoulder pain, somatic practices, stress 4 CommentsStress, incorrect posture, poor vision and not knowing how to relax may all contribute to neck and shoulder tension. More than 30% of all adults experience neck pain and 45% of girls and 19% of boys 18 year old, report back, neck and shoulder pain (Cohen, 2015; Côté, Cassidy, & Carroll, 2003; Hakala, Rimpelä, Salminen, Virtanen, & Rimpelä, 2002). Shoulder pain affects almost a quarter of adults in the Australian community (Hill et al, 2010). Most employees working at the computer experience neck and shoulder tenderness and pain (Brandt et al, 2014), more than 33% of European workers complained of back-ache (The European Agency for Safety and Health at Work, 2004), more than 25% of Europeans experience work-related neck-shoulder pain, and 15% experience work-related arm pain (Blatter & De Kraker, 2005; Eijckelhof et al, 2013), and more than 90% of college students report some muscular discomfort at the end of the semester especially if they work on the computer (Peper & Harvey, 2008).

The stiffness in the neck and shoulders or the escalating headache at the end of the day may be the result of craning the head more and more forward or concentrating too long on the computer screen. Or, we are unaware that we unknowingly tighten muscles not necessary for the task performance—for example, hunching our shoulders or holding our breath. This misdirected effort is usually unconscious, and unfortunately, can lead to fatigue, soreness, and a buildup of additional muscle tension.

The stiffness in the neck and shoulders or the escalating headache at the end of the day may be the result of craning the head more and more forward or concentrating too long on the computer screen. Poor posture or compromised vision can contribute to discomfort; however, in many cases stress is major factor. Tightening the neck and shoulders is a protective biological response to danger. Danger that for thousands of years ago evoke a biological defense reaction so that we could run from or fight from the predator. The predator is now symbolic, a deadline to meet, having hurry up sickness with too many things to do, anticipating a conflict with your partner or co-worker, worrying how your child is doing in school, or struggling to have enough money to pay for the rent.

Mind-set also plays a role. When we’re anxious, angry, or frustrated most of us tighten the muscles at the back of the neck. We can also experience this when insecure, afraid or worrying about what will happen next. Although this is a normal pattern, anticipating the worst can make us stressed. Thus, implement self-care strategies to prevent the occurrence of discomfort.

What can you do to free up the neck and shoulder?

Become aware what factors precede the neck and shoulder tension. For a week monitor yourself, keep a log during the day and observe what situations occur that precede the neck and should discomfort. If the situation is mainly caused by:

- Immobility while sitting and being captured by the screen. Interrupt sitting every 15 to 20 minutes and move such as walking around while swinging your arms.

- Ergonomic factors such as looking down at the computer or laptop screen while working. Change your work environment to optimize the ergonomics such as using a detached keyboard and raising the laptop screen so that the top of the screen is at eyebrow level.

- Emotional factors. Learn strategies to let go of the negative emotions and do problem solving. Take a slow deep breath and as you exhale imagine the stressor to flow out and away from you. Be willing to explore and change ask yourself: “What do I have to have to lose to change?”, “Who or what is that pain in my neck?”, or “What am I protecting by being so rigid?”

Regardless of the cause, explore the following five relaxation and stretching exercises to free up the neck and shoulders. Be gentle, do not force and stop if your discomfort increases. When moving, continue to breathe.

1. WIGGLE. Wiggle and shake your body many times during the day. The movements can be done surreptitiously such as, moving your feet back and forth in circles or tapping feet to the beat of your favorite music, slightly arching or curling your spine, sifting the weight on your buttock from one to the other, dropping your hands along your side while moving and rotating your fingers and wrists, rotating your head and neck in small unpredictable circles, or gently bouncing your shoulders up and down as if you are giggling. Every ten minutes, wiggle to facilitate blood flow and muscle relaxation.

2. SHAKE AND BOUNCE. Stand up, bend your knees slightly, and let your arms hang along your trunk. Gently bounce your body up and down by bending and straightening your knees. Allow the whole body to shake and move for about one minute like a raggedy Ann doll. Then stop bouncing and alternately reach up with your hand and arm to the ceiling and then let the arm drop. Be sure to continue to breathe.

3. ROTATION MOVEMENT (Adapted from the work by Sue Wilson and reproduced by permission from: Gorter, R. & Peper, E. (2011). Fighting Cancer- A Nontoxic Approach to Treatment).

Pre-assessment: Stand up and give yourself enough space, so that when you lift your arms to shoulder level and rotate, you don’t touch anything. Continue to stand in the same spot during the exercise as shown in figures 1a and 1b.

Lift your arms and hold them out, so that they are at shoulder level, positioned like airplane wings. Gently rotate your arms to the left as far as you can without discomfort. Look along your left arm to your fingertips and beyond to a spot on the wall and remember that spot. Rotate back to center and drop your arms to your sides and relax.

Figures 1a and 1b. Rotating the arms as far as is comfortable (photos by Jana Asenbrennerova)

Figures 1a and 1b. Rotating the arms as far as is comfortable (photos by Jana Asenbrennerova)

Movement practice. Again, lift your arms to the side so that they are like airplane wings pointing to the left and right. Gently rotate your trunk, keeping your arms fixed at a right angle to your body. Rotate your arms to the right and turn your head to the left. Then reverse the direction and rotate your arms in a fixed position to the left and turn your head to the right. Do not try to stretch or push yourself. Repeat the sequence three times in each direction and then drop your arms to your sides and relax.

With your arms at your sides, lift your shoulders toward your ears while you keep your neck relaxed. Feel the tension in your shoulders, and hold your shoulder up for five seconds. Let your shoulders drop and relax. Then relax even more. Stay relaxed for ten seconds.

Repeat this sequence, lifting, dropping, and relaxing your shoulders two more times. Remember to keep breathing; and each time you drop your shoulders, relax even more after they have dropped.

Repeat the same sequence, but this time, very slowly lift your shoulders so that it takes five seconds to raise them to your ears while you continue to breathe. Keep relaxing your neck and feel the tension just in your shoulders. Then hold the tension for a count of three. Now relax your shoulders very slowly so that it takes five seconds to lower them. Once they are lowered, relax them even more and stay relaxed for five seconds. Repeat this sequence two more times.

Now raise your shoulders quickly toward your ears, feel the tension in your upper shoulders, and hold it for the count of five. Let the tension go and relax. Just let your shoulders drop. Relax, and then relax even more.

Post-assessment. Lift your arms up to the side so that they are at shoulder level and are positioned like airplane wings. Gently rotate without discomfort to the left as far as you can while you look along your left arm to your fingers and beyond to a spot on the wall.

Almost everyone reports that when they rotate the last time, they rotated significantly further than the first time. The increased flexibility is the result of loosening your shoulder muscles.

4. TAPPING FEET (adapted from the work of Servaas Mes)

Diagonal movements underlie human coordination and if your coordination is in sync, this will happen as a reflex without thought. There are many examples of these basic reflexes, all based on diagonal coordination such as arm and leg movement while walking. To restore this coordination, we use exercises that emphasize diagonal movements. This will help you reverse unnecessary tension and use your body more efficiently and thereby reducing “sensory motor amnesia” and dysponesis (Hanna, 2004). Remember to do the practices without straining, with a sense of freedom, while you continue relaxed breathing. If you feel pain, you have gone too far, and you’ll want to ease up a bit. This practice offers brief, simple practices to avoid and reverse dysfunctional patterns of bracing and tension and reduce discomfort. Practicing healthy patterns of movement can reestablish normal tone and reduce tension and pain. This is a light series of movements that involve tapping your feet and turning your head. You’ll be able to do the entire exercise in less than twenty seconds.

Pre-assessment. Sit erect at the edge of the chair with your hands on your lap and your feet shoulders’ width apart, with your heels beneath your knees.

First, notice your flexibility by gently rotating your head to the right as far as you can. Now look at a spot on the wall as a measure of how far you can comfortably turn your head and remember that spot. Then rotate back to the center.

Practicing rotating feet and head. Become familiar with the feet movement, lift the balls of your feet so your feet are resting on your heels. Lightly pivot the balls of your feet to the right, tap the floor, and then stop and relax your feet for just a second. Now lift the balls of your feet, pivot your feet to the left, tap, relax, and pivot back to the right.

Just let your knees follow the movement naturally. This is a series of ten light, quick, relaxed pivoting movements—each pivot and tap takes only about one or two seconds.

Add head rotation. Turn your head in the opposite direction of your feet. This series of movements provides effortless stretches that you can do in less than half a minute as shown in figures 2a and 2b.

Figures 2a and 2b. Rotating the feet and head in opposite directions (photos by Gary Palmer)

Figures 2a and 2b. Rotating the feet and head in opposite directions (photos by Gary Palmer)

When you’re facing right, move your feet to the left and lightly tap. Then face left and move your feet to the right and tap.

- Continue the tapping movement, but each time pivot your head in the opposite direction. Don’t try to stretch or force the movement.

- Do this sequence ten times. Now stop, face straight head, relax your legs, and just keep breathing.

Post assessment. Rotate your head to the right as far as you can see and look at a spot on the wall. Notice how much more flexibility/rotation you have achieved.

Almost everyone reports being able to rotate significantly farther after the exercise than before. They also report that they have less stiffness in their neck and shoulders.

5. SHOULDER AWARENESS PRACTICE. Sit comfortably with your hands on your lap. Allow your jaw to hang loose and breathe diaphragmatically. Continue to breathe slowly as you do the following:

- Shrug, raising your shoulders towards your ears to 70% of maximum effort and hold them up for about 10 seconds (note the sensations of tension).

- Let your shoulders drop and relax for 10 to 20 seconds

- Shrug, raising your shoulders towards your ears to 50% of maximum effort and hold them up for about 10 seconds (note the sensations of tension).

- Let your shoulders drop and relax for 10 to 20 seconds

- Shrug, raising your shoulders towards your ears to 25% of maximum effort and hold them up for about 10 seconds (note the sensations of tension).

- Let your shoulders drop and relax for 10 to 20 seconds

- Shrug, raising your shoulders towards ears to 5% of maximum effort and hold them up for about 10 seconds (note the sensations of tension).

- Let your shoulders drop and relax for 10 to 20 seconds

- Pull your shoulders down to 25% of maximum effort and hold them up for about 10 seconds (note the sensations of tension).

- Allow your shoulders to come back up and relax for 10 to 20 seconds

Remember to relax your shoulders completely after each incremental tightening. If you tend to hold your breath while raising your shoulders, gently exhale and continue to breathe. When you return to work, check in occasionally with your shoulders and ask yourself if you can feel any of the sensations of tension. If so, drop your shoulders and relax for a few seconds before resuming your tasks.

In summary, when employees and students change their environment and integrate many movements during the day, they report a significant decrease in neck and shoulder discomfort and an increase in energy and health. As one employee reported, after taking many short movement breaks while working at the computer, that he no longer felt tired at the end of the day, “Now, there is life after five”.

To explore how prevent and reverse the automatic somatic stress reactions, read Thomas Hanna‘s book, Somatics: Reawakening The Mind’s Control of Movement, Flexibility, and Health. For easy to do neck and shoulder guided instructions stretches, see the following ebsite: http://greatist.com/move/stretches-for-tight-shoulders

References:

Blatter, B. M., & Kraker, H. D. (2005). Prevalentiecijfers van RSI-klachten en het vóórkomen van risicofactoren in 15 Europese landen. Tijdschrift voor gezondheidswetenschappen, 1, 83, 8-15.

Côté, P., Cassidy, J. D., & Carroll, L. (2003). The epidemiology of neck pain: what we have learned from our population-based studies. The Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association, 47(4), 284. http://www.pain-initiative-un.org/doc-

European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (2004). http://europa.eu.int/comm/employment_social/news/2004/nov/musculoskeletaldisorders_en.html

Paoli, P., Merllié, D., & Fundação Europeia para a Melhoria das Condições de Vida e de Trabalho. (2001). Troisième enquête européenne sur les conditions de travail, 2000.

*I thank Sue Wilson and Servaas Mes for teaching me these somatic practices.

Relax and Relax More*

Posted: February 6, 2015 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: awareness, electromyography, muscle biofeedback, relaxation, shoulder pain 3 CommentsAfter raising my shoulders and then relaxing it, I felt relaxed. I was totally surprised that the actual muscle tension recorded with surface electromyographic (SEMG) still showed tension. Only when I gave myself the second instruction, relax even more, that my SEMG activity decreased.

In our experiences, we (Vietta E. Wilson and Erik Peper, 2014) have observed that muscle tension often does not decrease completely after a person is instructed to relax. The complete relaxation only occurs after the second instruction, relax more, let go, drop, or feel the heaviness of gravity. The person is totally unaware that after the first relaxation their muscless have not totally relaxed. Their physiology does not match their perception (Peper et, 2010; Whatmore & Kohli, 1974). The low level of muscle tension appears more prevalent in people who are have a history of muscle stiffness or pain, or in athletes whose coaches report they look ‘tight.’ It is only after the second command, relax and release even more, that the individual notices a change and experiences a deeper relaxation.

The usefulness of giving a second instruction, relax more, after the first instruction, relax, is illustrated below by the surface electromyographic (SEMG) recording from the upper left and right trapezius muscle of a 68 year old male with chronic back pain. While sitting upright without experiencing any pain, he was instructed to lift his shoulders, briefly hold the tension, and then relax (Sella, 1997; Peper et al, 2008). When the SEMG of the trapezius muscles did not decrease to the relaxed state, he was asked to relax more as is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. SEMG recordings of the left and right upper trapezius when the client was asked to lift his shoulders, hold, relax, and relax more. Only after the second instruction did the muscle tension decrease to the relaxed baseline level. Reprinted from Wilson and Peper, 2014.

Although the subject felt that he was relaxed after the first relaxation instruction, he continued to hold a low level of muscle tension. We have observed this same process in hundreds of clients and students while teaching SEMG guided relaxation and progressive muscle relaxation.

For numerous people, even the second commands to relax even more is not sufficient for the SEMG to show muscle relaxation and for them to ‘feel’ or know when they are totally relaxed. These individuals may benefit from SEMG biofeedback to identify and quantify the degree of muscle tension. With this information the person can make the invisible muscle contractions ‘ visible,’ the un-felt tension ‘felt,’ and thus develop awareness and control (Peper et al, 2014).

In summary

- Instruct people to relax after tightening and then repeat the instruction to relax even more.

- Use surface electromyography to confirm whether the person’s subjective experience of being muscularly relaxed corresponds to the actual physiological SEMG recording.

- Use the SEMG biofeedback to train the person to increase awareness and learn relaxation (Peper et al, 2014).

- Read the complete article from which this blog was adapted: Wilson, E. & Peper, E. (2014). Clinical Tip: Relax and Relax More. 42(4), 163-164.

References

Peper, E., Booiman, A., Lin, I-M., & Shaffer, F. (2014). Making the Unaware Aware-Surface electromyography to unmask tension and teach awareness. Biofeedback. 42(1), 16-23.

Peper, E., Booiman, A., Tallard, M., & Takebayashi, N. (2010). Surface electromyographic biofeedback to optimize performance in daily life: Improving physical fitness and health at the worksite. Japanese Journal of Biofeedback Research, 37(1), 19-28.

Peper, E., Tylova, H., Gibney, K.H., Harvey, R., & Combatalade, D. (2008). Biofeedback mastery-An experiential teaching and self-training manual. Wheat Ridge, CO: AAPB.

*This blogpost is adapted from, Wilson, E. & Peper, E. (2014). Clinical tip: Relax and relax more. Biofeedback. 42(4), 163-164.

Cellphone harm: Cervical spine stress and increase risk of brain cancer

Posted: November 20, 2014 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: cancer, cell phones, ergonomics, health, microwaves, neck pain, posture, shoulder pain, wireless 2 CommentsIt is impossible to belief that that only a few years ago there were no cell phones.

When I go home, I purposely put the phone away so that I can be present with my children.

I just wonder if the cell phone’s electromagnetic radiation could do harm?

Cell phone use is ubiquitous since information is only a key press or voice command away. Students spend about many hours a day looking and texting on a cell phone and experience exhaustion and neck and shoulder discomfort (Peper et al, 2013). Constant use may also have unexpected consequences: Increased stress on the cervical spine and increased risk for brain cancer.

Increased cervical spine stress

As we look at the screen, text messages or touch the screen for more information, we almost always bend our head down to look down. This head forward position increases cervical compression and stress. The more the head bends down to look, the more the stress in the neck increases as the muscles have to work much harder that hold the head up. In a superb analysis Dr. Kennth Hansraj, Chief of Spine Surgery 0f New York Spine Surgery & Rehabilitation Medicine, showed that stress on the cervical spine increases from 10-12 lbs when the head is in its upright position to 60 lbs when looking down.

Figure 1. Stress on the cervical spine as related to posture. (From: Hansraj, K. K. (2014). Assessment of stresses in the cervical spine caused by posture and position of the head. Surgical technology international, 25, 277-279.)

Figure 1. Stress on the cervical spine as related to posture. (From: Hansraj, K. K. (2014). Assessment of stresses in the cervical spine caused by posture and position of the head. Surgical technology international, 25, 277-279.)

Looking down for a short time period is no problem; however, many of us look down for extended periods. This slouched collapsed position is becoming the more dominant position. A body posture which tends to decrease energy, and increase hopeless, helpless, powerless thoughts (Wilson & Peper, 2004; Peper & Lin, 2012). The long term effects of this habitual collapsed position are not know–one can expect more neck and back problems and increase in lower energy levels.

increased risk for brain cancer and inactive sperm and lower sperm count

Cell phone use not only affect posture, the cell phone radio-frequency electromagnetic radiation by which the cell phone communicates to the tower may negatively affect biological tissue. It would not be surprising that electromagnetic radiation could be harmful; since, it is identical to the frequencies used in your microwave ovens to cook food. The recent research by Drs Michael Carlberg and Lennart Hardell of the Department of Oncology, University Hospital, Örebro, Sweden, found that long term cell phone use is associated by an increased risk of developing malignant glioma (brain cancers) with the largest risk observed in people who used the cell phone before the age of 20. In addition, men who habitually carry the cell phone in a holster or in their pocket were more likely to have inactive or less mobile sperm as well as a lower sperm count.

What can you do:

Keep an upright posture and when using a cell phone or tablet. Every few minutes stretch, look up and reach upward with your hands to the sky.

Use your speaker phone or ear phones instead of placing the phone against your head.

Enjoy the cartoon video clip, Smartphone Ergonomics – Safe Tips – Mobile or Smart Phone Use while Driving, Traveling on the Move.

References:

Agarwal, A., Singh, A., Hamada, A., & Kesari, K. (2011). Cell phones and male infertility: a review of recent innovations in technology and consequences. International braz j urol, 37(4), 432-454. http://www.isdbweb.org/documents/file/1685_8.pdf

Carlberg, M., & Hardell, L. (2014). Decreased Survival of Glioma Patients with Astrocytoma Grade IV (Glioblastoma Multiforme) Associated with Long-Term Use of Mobile and Cordless Phones. International journal of environmental research and public health, 11(10), 10790-10805. http://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/11/10/10790/htm

De Iuliis, G. N., Newey, R. J., King, B. V., & Aitken, R. J. (2009). Mobile phone radiation induces reactive oxygen species production and DNA damage in human spermatozoa in vitro. PloS one, 4(7), e6446.

Hansraj, K. K. (2014). Assessment of stresses in the cervical spine caused by posture and position of the head. Surgical technology international, 25, 277-279.

Peper, E. & Lin, I-M. (2012). Increase or decrease depression-How body postures influence your energy level. Biofeedback, 40 (3), 126-130.

Peper, E., Waderich, K., Harvey, R., & Sutter, S. (2013). The Psychophysiology of Contemporary Information Technologies Tablets and Smartphones Can Be a Pain in the Neck. In Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 38(3), 219.

Wilson, V.E. and Peper, E. (2004). The Effects of upright and slumped postures on the generation of positive and negative thoughts. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.29 (3), 189-195.

Cartoon ergonomics for working at the computer and laptop

Posted: September 30, 2014 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: cell phones, computer, health, Laptop, muscle tension, neck pain, pain, posture, shoulder pain 6 CommentsI finally bought a separate keyboard and a small stand for my laptop so that the screen is at eye level and my shoulders are relaxed while typing at the keyboard. To my surprise, my neck and shoulder tightness and pain disappeared and I am much less exhausted.

How we sit and work at the computer significantly affects our health and productivity. Ergonomics is the science that offers guidelines on how to adjust your workspace and equipment to suit your individual needs. It is just like choosing appropriate shoes–Ever try jogging in high heels? The same process applies to the furniture and equipment you use when computing.

When people arrange their work setting according to good ergonomic principles and incorporate a healthy computing work style numerous disorders (e.g., fatigue, vision discomfort, head, neck, back, shoulder, arm or hand pain) may be prevented (Peper et al, 2004). For pragmatic tips to stay health at the computer see Erik Peper’s Health Computer Email Tips. Enjoy the following superb video cartoons uploaded by Stephen Walker on YouTube that summarize the basic guidelines for computer, laptop and cell phones use at work, home, or while traveling.

Adult or Child Laptop Use at Home, Work or Classroom

Healthy use of laptops anywhere.

Mobile or Smart Phone Use while Driving, Traveling or on the Move.

Focus On Possibilities, Not On Limitations. Youtube interviews of Erik Peper, PhD, by Larry Berkelhammer, PhD

Posted: March 18, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: biofeedback, mind-body, pain, relaxation, shoulder pain, yoga Leave a comment

Focus On Possibilities, Not On Limitations

This interview with psychophysiologist Dr. Erik Peper reveals self-healing secrets used by yogis for thousands of years. Mind-training methods used by yogis like Jack Schwarz were explored. The underlying message throughout the discussion was that suffering and even actual tissue damage are profoundly influenced by both our negative and our positive attributions. The methods by which yogis have learned to self-heal is available to all of us who are willing to assiduously adopt a daily practice. It is very clear that when our attention goes to our pain or other symptoms, our suffering and even tissue damage worsens. When we focus all our attention on what we want rather than on what we are afraid of, we achieve a healthier, more positive, and more robust level of healing. We suffer when we have negative expectancies and we reduce suffering when we focus our attention on positive expectancies. We can train the mind to fully experience sensations without negative attributions. For the vast majority of us, we have far greater potential than we believe we have. Biofeedback, concentration practices, mindfulness practices, and other yogic practices allow us to condition ourselves to concentrate on the present moment, rather than on our negative expectancies, limitations, attributions, and fears.

Belief Becomes Biology

Dr. Larry Berkelhammer speaks with Dr. Erik Peper about the connection of our beliefs and our health.

Improve health with fun movements: Practices you can do at home and at work

Posted: February 2, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: exercise, mind-body, muscle tension, neck pain, relaxation, shoulder pain, stress management 7 CommentsPhysical fitness promotes health. For one person it may be walking, for another jogging, bicycling or dancing. Increase the joy and pleasure of movement. In most cases about 20 minutes of continued activity is enough to keep in shape and regenerate. When the urge to watch TV or just to crash occurs, do some of the movement—you will gain energy. The exercises this article are are developed to reduce discomfort, increase flexibility and improve health. Practice them throughout the day, especially before the signals of pain or discomfort occur. First read over the General Concepts Underlying the Exercises and then explore the various practices.

General Concepts Underlying the Exercises

While practicing the strength and stretch exercises, always remember to breathe. Exercises should be performed slowly, gently and playfully. If pain or discomfort occurs, STOP. Please consult your health care provider if you have any medical condition which could be affected by exercise.

Perform the practices in a playful, exploratory manner. Ask yourself: “What is happening?” and “How do I feel different during and after the practice?” Practice with awareness and passive attention. Remember, Pain, No gain — Pain discourages practice. Pain and the anticipation of pain usually induce bracing which is the opposite of relaxation and letting go. In addition, many of our movements are conditioned and without knowing we hold our breath and tighten our shoulders when we perform an exercise. Explore ways to keep breathing and thereby inhibit the startle/orienting/flight response embedded and conditioned with the movements. For example, continue to breathe and relax instead of holding your breath and tightening your shoulders when you initially look at something or perform a task.

Learn to reduce the automatic and unnecessary tightening of muscles not needed for the performance of the task. As you do an exercise, continuously, check your body and explore how to relax muscles that are not needed for the actual exercise. Become your own instructor in the same way that a yoga teacher reminds you to exhale when you are doing an asana (yoga pose). If you are unsure whether you are tightening, initially look another person doing the exercise to observe their bracing and breath holding patterns. Ask them to observe you and give feedback. In many cases, the more others are involved the easier it is to do a practice.

It is often helpful to perform the practice in a group. Encourage your whole work unit to take breaks and exercise together. Usually it is much easier to do something together, especially when you are not motivated—use social support to help you do your practices.

Problems with neck, back and shoulders

The number one overall work-related complaint is the back pain and this is also true for many people who work at the computer. In many cases there are correlations between backache and stress, immobility, and lack of regeneration. Back pain is often blamed on disk problems which may be aggravated by chronic tension that may have some psychological factors. When you experience discomfort, explore some of the following questions:

- Is there something for which I am spineless?

- Who or what is the pain in my neck or back?

- What is the weight I am carrying?

- Am I rigid and not willing to be flexible?

- What negative emotion, such as anger or resentment, needs to resolved?

Be willing to act on whatever answers you observe. Back and neck pain is often significantly reduced after emotional conflicts are resolved (see the book by John Sarno, MD., Healing Back Pain: The Mind-Body Connection). The best treatment is prevention, emotional resolution, and physical movement. Allow your back to relax and move episodically. Allow tensions to dissipate and explore the physical, psychological and social burdens you carry. To loosen your neck practice the following exercise.

Free your neck and shoulders[1]

This is a slightly complicated, but very effective process. You may want to ask a friend or co-worker to read the following instructions to you.

Pretest: Push away from the keyboard. Sit at the edge of the chair with your knees bent at approximately 90 degrees and your feet flat on the floor about shoulder width apart. Do the movements slowly. Do NOT push yourself if you feel discomfort. Be gentle with yourself.

Look to the right and gently turn your head and body as far as you can go to the right. When you have gone as far as you can comfortably, look at the furthest spot on the wall and remember that spot. Gently rotate your head and body back to center. Close your eyes and relax.

Movement practice: Reach up with your right hand; pass it over the top of your head and hold on to your left ear. Then gently bend to the right lowering the elbow towards the floor. Slowly straighten up. Repeat a few times, feeling as if you are a sapling flexing in the breeze as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Illustration of side ways bending with hand holding ear.

Observe what your body is doing as it bends and comes back up to center. Notice the movements in your ribs, back and neck. Then drop your arm to your lap and relax. Make sure you continue to breathe diaphragmatically throughout the exercise.

Reach up with your left hand, pass it over the top of your head and hold on to your right ear. Repeat as above, this time bending to the right.

Reach up with your right hand and pass it over the top of your head, now holding onto your left ear. Then look to the right with your eyes and rotate your head to the right as if you are looking behind you. Return to center and repeat the movement a few times. Then drop your arm to your lap and relax for a few breaths as shown in Figure 2.  Figure 2. Illustration of rotational movement with hand holding ear.

Figure 2. Illustration of rotational movement with hand holding ear.

Repeat the same rotating motion of your head to the right, except that now your eyes look to the left. Repeat this a few times, then drop your arm to your lap and relax for a few breaths.

Repeat the exercise except reach up with your left hand and pass it over the top of your head, and hold on to your right ear. Then look to the left with your eyes and rotate your head to the left as if you are looking behind you. Return to center and repeat a few times. Then drop your arms to your lap and relax for a few breaths.

Repeat the same rotating motion of your head to the left, except that your eyes look to the right. Repeat this a few times, then drop your arm to your lap and relax for a few breaths.

Post test: look to the right and gently turn your head and body as far as you can go. When you cannot go any further, look at that point on the wall. Gently rotate your head back to center, close your eyes, relax and notice the relaxing feelings in your neck, shoulders and back.

Did you rotate further than at the beginning of the exercise? More than 95% of participants report rotating significantly further as compared to the pretest.

For additional exercises on how to loosen your neck, shoulders, back, arms, hands, and legs, click on the link for the article, Improve health with movement: There is life after five or look at the somatic relaxation practices in part 3 of our book, Fighting Cancer-A Nontoxic Approach to Treatment.

[1] Adapted from a demonstration by Sharon Keane and developed by Ilana Rubenfeld

Prevent Stress Immobilization Syndrome

Posted: January 27, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: exercise, muscle tension, neck pain, repetitive sttrain injury, shoulder pain 6 CommentsSource unknown

Working at the computer, tablet or smartphone is often a pain in the neck. Young adults who are digital natives and work with computers and mobile phones experienced frequent pain, numbness or aches in their neck and more than 30% reported aches in their hip and lower back. In addition, women experienced almost twice as much aches in their necks than men (Korinen and Pääkkönen, 2011). Similarly findings have been reported previously when Peper and Gibney observed that most students at San Francisco State University, experienced some symptoms when working at their computer near the end of the semester. At work, many employees also experience exhaustion, neck, back and shoulder pains when working at the computer. Although many factors contribute to this discomfort such as ergonomics, work and personal stress, a common cause is immobility. To prevent stress immobility syndrome, implement some of the following practice.

- Every hour take a 5-minute break (studies at the Internal Revenue Service show that employees report significant reduction in symptoms without loss in productivity when they take a 5 minute break each hour).

- Take a short walk or do other movements instead of snacking when feeling tense or tired.

- Perform a stretch, strengthening, relaxation, or mobilization movement every 30 minutes.

- Install a computer reminder program to signal you to take a short stress break such as StressBreak™.

- Perform 1-2 second wiggle movements (micro-breaks) every 30 to 60 seconds such as dropping your hands to your lap as you exhale.

- Leave your computer station for the 15-minute mid-morning and mid-afternoon breaks.

- Eat lunch away from your computer workstation.

- Stand or walk during meetings.

- Drink lots of water (then, you’ll have to walk to the restroom).

- Change work tasks frequently during the day.

- Move your printer to another room so that you have to walk to retrieve your documents.

- Stand up when talking on the phone or when a co-worker stops by to speak with you.

When people implement these new habits, they experience significant decrease in symptoms and improvements in quality of life and health (Peper & Gibney, 2004; Wolever et al, 2011)

Maintain energy and health at work

Posted: February 22, 2012 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: breath holding, Computing, neck pain, repetitive strain injury, respiration, shoulder pain 2 CommentsI never realized that I braced my shoulders and held my breath while typing. Now I know the importance of not doing this, and have tools to change.

–Secretary in training program, San Francisco State University

Most employees who work on computers experience discomfort ranging from neck, shoulder, back, and arm pain to eye irritation and exhaustion–a cluster of symptoms that we have labeled Stress Immobilization Syndrome. A major cause of this is the holding of chronic and unnecessary muscle tension of which the employee is usually unaware. This often leads to illness. Doing the following practice will help you to become aware of these patterns:

Sit on the edge of your chair and hold your mouse and then begin to draw with your mouse, the letters and numbers of your street address; however, draw the letters backward by beginning with the last letter of the street address. Draw each letter about 1 1/4 inch in height, and then click the left button after having drawn the letter. Continue to draw the next letter. Draw as quickly as possible without making any mistakes as if your boss is waiting for the results. Start now, and continue for the next 30 seconds. Now, observe what happened.

Did you hold your breath, tightened your neck, shoulders, and trunk, forgot to blink as you drew the letters with your mouse? Imagine what would happen if you worked like this hour after hour: Tension headaches, shoulder pain, exhaustion?

Research at San Francisco State University has demonstrated that with biofeedback 95% of employees automatically raised their shoulders, and maintained low-level tension in their forearms while keyboarding and mousing.They also increased their breathing rates , and decreased eye blinking rates. Almost all employees studied thought that their muscles were relaxed when they were sitting correctly at the computer, even though they were tense, as is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 is a representative recording of a person working at the computer. Note how 1) forearm and shoulder (deltoid/trapezius) muscle tension increased as the person rests her hands on the keyboard without typing; 2) respiration rate increased during typing and mousing; 3) shoulder muscle tension increased during typing and mousing; and 4) there were no rest periods in the shoulder muscles as long as the fingers are either resting, typing, or mousing. By permission from: Peper, E. (2007). Stay Healthy at the Computer: Lessons Learned from Research. Physical Therapy Products. April.

While working at the computer most people are captured by the computer, and are unaware of how their bodies react. Computing during the day and surfing the net at night, most people report neck and shoulder tension, back pain, eye irritation and/or fatigue otherwise labeled as Stress Immobilization Syndrome, see figure 2.

Figure 2. Distribution of reported symptoms experienced by college students (average age 26.3 years) while working on the computer near the end of their semester (reproduced with permission from Peper, E., & Gibney, K, H. (1999). Computer related symptoms: A major problem for college students. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. 24 (2), 134.

How to reverse and interrupt Stress Immobilization Syndrome

When working at the computer, remind yourself to

- Interrupt your computer work every few minutes to wiggle and move

- Breathe diaphragmatically

- Get up and do large movements (stretch or walk) for a few minutes.

- Smile and realize that the work stress it is not worth dying over

When implementing these simple changes, employees report significant reduction in symptoms. As one participant stated, “There is life after five.”

For detailed tips how to maintain health at the computer download Healthy Computing Email Tips

Muscle biofeedback makes the invisible visible

Posted: January 6, 2012 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: back pain, biofeedback, electromyography, muscle tension, neck pain, performance, shoulder pain 3 Comments“I feel much more relaxed and realize now how unaware I was of the unnecessary tension I’ve been holding” is a common response after muscle biofeedback training. Many people experience exhaustion, stiffness, tightness, neck, shoulder and back pain while working long hours at the computer or while exercising. As we get older, we assume that discomforts are the result of aging. You just have to accept it and live with it–grin and bear it–or you need to be more careful while doing your job or performing your hobby. The discomfort in many cases is the result of misuse of your body. Observes what happens when you perform the following experiential practice Threading the needle.

Perform this task so that an observer would think it was real and would not know that you are only simulating threading a needle.

Imagine that you are threading a needle — really imagine it by picturing it in your mind and acting it out. Hold the needle between your left thumb and index finger. Hold the thread between the thumb and index finger of your right hand. Bring the tip of the thread to your mouth and put it between your lips to moisten it and make it into a sharp point. Then attempt to thread the needle, which has a very small eye. The thread is almost as thick as the eye of the needle.

As you are concentrating on threading this imaginary needle, observed what happened? While acting out the imagery, did you raise or tighten your shoulders, stiffen your trunk, clench your teeth, hold your breath or stare at the thread and needle without blinking?

Most people are surprised that they have tightened their shoulders and braced their trunk while threading the needle. Awareness only occurred after their attention was directed to the covert muscle bracing patterns.

In many cases muscles are tense even though the person senses and feels that they are relaxed. This lack of awareness can be resolved with muscle biofeedback–it makes invisible visible. Muscle biofeedback (electromyographic feedback) is used to monitor the muscle activity, teach the person awareness of the previously unperceived muscle tension and learn relax and control it. For more information of the use of muscle biofeedback to improve health and performance at work or in the gym, see the published chapter, I thought I was relaxed: The use of SEMG biofeedback for training awareness and control, by Richard Harvey and Erik Peper. It was published in W. A. Edmonds, & G. Tenenbaum (Eds.). (2012), Case studies in applied psychophysiology: Neurofeedback and biofeedback treatments for advances in human performance. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 144-159.