Are food companies responsible for the epidemic in diabetes, cancer, dementia and chronic disease and do their products need to be regulated like tobacco? Is it time for a class action suit?

Posted: July 15, 2023 Filed under: behavior, cancer, Evolutionary perspective, health, Nutrition/diet, self-healing | Tags: dementia, diabetes, diet, high fructose corn syrup, mortality, obsity, smoking, sugar, ultra-processed foods, UPF 2 CommentsAdapted from: Peper, E. & Harvey, R. (2024). Are Food Companies Responsible for the Epidemic in Diabetes, Cancer, Dementia and Chronic Disease and Do Their Products Need to Be Regulated Like Tobacco? Is It Time for a Class Action Suit? Thownsend Letter-the examiner of alternative medicine. https://www.townsendletter.com/e-letter-26-ultra-processed-foods-and-health-issues/

Erik Peper, PhD and Richard Harvey, PhD

Why are one third of young Americans becoming obese and at risk for diabetes?

Why are heart disease, cancer, and dementias occurring earlier and earlier? Is it genetics, environment, foods, or lifestyle?

Is it individual responsibility or the result of the quest for profits by agribusiness and the food industry?

Like the tobacco industry that sells products regulated because of their public health dangers, is it time for a class action suit against the processed food industry? The argument relates not only to the regulation of toxic or hazardous food ingredients (e.g., carcinogenic or obesogenic chemicals) but also to the regulation of consumer vulnerabilities. Addressing vulnerabilities to tobacco products include regulations such as how cigarette companies may not advertise their products for sale within a certain distance from school grounds.

Is it time to regulate nationally the installation of vending machines on school grounds selling sugar-sweetened beverages? Students have sensitivity to the enticing nature of advertised, and/or conveniently available consumable products such as ‘fast foods’ that are highly processed (e.g., packaged, preserved and practically imperishable). Whereas ‘processed foods’ have some nutritive value, and may technically pass as ‘nutritious’ food, the quality of processed ‘nutrients’ can be called into question. For the purpose of this blog other important questions to raise relate to ingredients which, alone or in combination, may contribute to the onset of or, the acceleration of a variety of chronic health outcomes related to various kinds of cancers, cardiovascular diseases, and diabetes.

It may be an over statement to suggest that processed food companies are directly responsible for the epidemic in diabetes, cancer, dementia and chronic disease and need to be regulated like tobacco. On the other hand, processed food companies should become much more regulated than they are now.

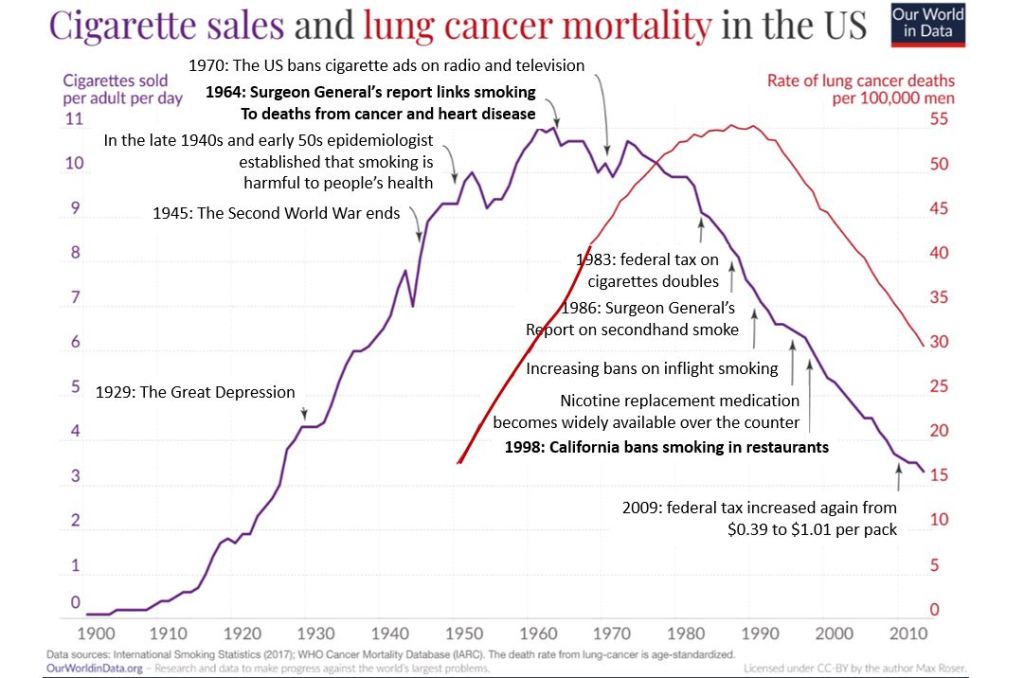

More than 80 years ago, smoking was identified as a significant factor contributing to lung cancer, heart disease and many other disorders. In 1964 the Surgeon Generals’ report officially linked smoking to deaths of cancer and heart disease (United States Public Health Service, 1964). Another 34 years pased before California prohibited smoking in restaurants in 1998 and, eventually inside all public buildings. The harms of smoking tobacco products were well known, yet many years passed with countless deaths and suffering which could have been prevented before regulation of tobacco products took place. Reviewing historical data there is about a 20 year delay (e.g., a whole generation) before death rates decrease in relation to when regulations became effective and smoking rates decreased, as shown in figure 1.

Figure 1. The relationship between smoking and lung cancer. Reproduced by permission from Roser, M. (2021). Smoking: How large of a global problem is it? And how can we make progress against it? Our world in data.

During those interim years before government actions limited smoking more effectively, tobacco companies hid data regarding the harmful effects of smoking. Arguably, the ‘Big Tobacco’ industry paid researchers to publish data which could confuse readers about tobacco product harm. There is evidence of some published articles suggesting that the harm of cigarette smoking was a hoax– all for the sake of boosting corporate profits (Bero, 2005).

Now we are experiencing a similar problem with the processed food industry. It has been suggested that alongside smoking and vaping, opioid use, a sedentary ‘couch potato’ lifestyle, and lack of exercise, ultra-processed food (UPF) that we eat severely affects our health.

Ultra-processed foods, which for many constitutes a majority of calories ranging from 55% to over 80% of the food they eat, contain chemical additives that trick the tastebuds, mouth and eventually our brain to desire those processed foods and eat more of them (Srour et al., 2022).

What are ultra-processed foods? Any foods that your great grandmother would not recognize as food. This includes all soft drinks, highly processed chips, additives, food coloring, stabilizers, processed proteins, etc. Even oils such as palm oil, canola oil, or soybean are ultra processed since they heated, highly processed with phosphoric acid to remove gums and waxes, neutralized with chemicals, bleached, and deodorized with high pressure steam (van Tulleken, 2023).

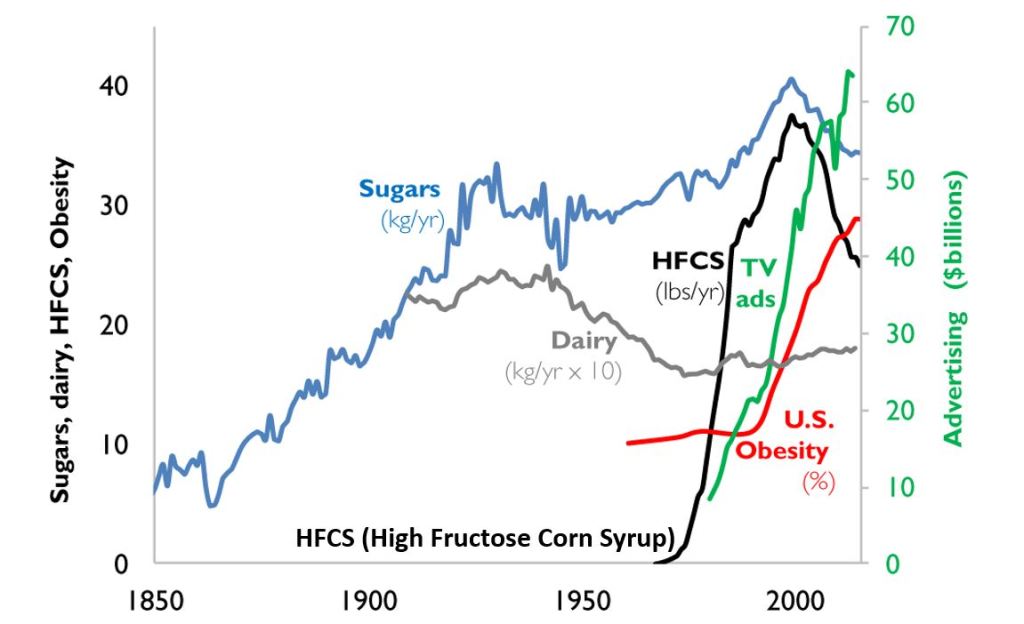

The data is clear! Since the 1970s obesity and inflammatory disease have exploded after ultra-processed foods became the constituents of the modern diet as shown in figure 2.

Figure 2. A timeline from 1850 to 2000 reflects the increase in use of refined sugar and high fructose corn syrup (HFCS) to the U.S. diet, together with the increase in U.S. obesity rate. The data for sugar, dairy and HFCS consumption per capita are from USDA Economic Research Service (Johnson et al., 2009) and reflects historical estimates before 1967 (Guyenet et al., 2017). The obesity data (% of U.S. adult population) are from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Trust for America’s Health. (stateofobesity.org). Total U.S. television advertising data are from the World Advertising Research Center (www.warc.com). The vertical measure (y–axis) for kilograms per year (kg/yr) on the left covers all data except advertising expenditures, which uses the vertical measure for advertising on the right. Reproduced by permission from Bentley et al, 2018.

This graph clearly shows a close association between the years that high fructose corn syrups (HFCS) were introduced into the American diet and an increase in TV advertising with corresponding increase in obesity. HFCS is an ultra-processed food and is a surrogate marker for all other ultra-processed foods. The best interpretation is that ultra-processed foods, which often contain HFCS, are a causal factor of the increase in obesity, and diabetes and in turn are risk factors for heart disease, cancers and dementias.

Ultra-processed foods are novel from an evolutionary perspective.

The human digestive system has only recently encountered sources of calories which are filled with so many unnatural chemicals, textures and flavors. Ultra-processed foods have been engineered, developed and product tested to increase the likelihood they are wanted by consumers and thereby increase sales and profits for the producers. These foods contain the ‘right amount’ processed materials to evoke the taste, flavor and feel of desired foods that ‘trick’ the consumer it eat them because they activate evolutionary preference for survival. Thus, these ultra-processed foods have become an ‘evolutionary trap’ where it is almost impossible not to eat them. We eat the food because it capitalized on our evolutionary preferences even though doing so is ultimately harmful for our health (for a detailed discussion on evolutionary traps, see Peper, Harvey & Faass, 2020).

An example is a young child wanting the candy while waiting with her parents at the supermarket checkout line. The advertised images of sweet foods trigger the cue to eat. Remember, breast milk is sweet and most foods in nature that are sweet in taste, provide calories for growth and survival and are not harmful. Calories are essential of growth. Thus, we have no intrinsic limit on eating sweets unlike foods that taste bitter.

As parents, we wish that our children (and even adults) have self-control and no desire to eat the candy or snacks that is displayed at eye level (eye candy) especially while waiting at the cashier. When reflecting about food advertising and the promotion of foods that are formulated to take advantage of ‘evolutionary traps’, who is responsible? Is it the child, who does not yet have the wisdom and self-control or, is it the food industry that ultra-processes the foods and adds ingredients into foods which can be harmful and then displays them to trigger an evolutionary preference for food that have been highly processed?

Every country that has adapted the USA diet of ultra-processed foods has experienced similar trends in increasing obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, etc. The USA diet is replacing traditional diets as illustrated by the availability of Coca-Cola. It is sold in over 200 countries and territories (Coca-Cola, 2023).

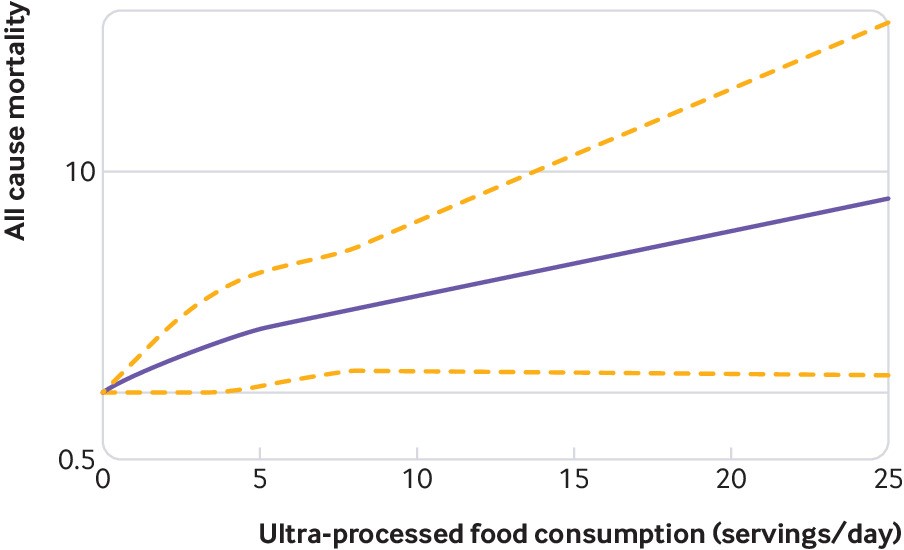

An increase in ultra-processed foods by 10 percent was associated with a 25 percent increase in the risk of dementia and a 14 per cent increase in the risk of Alzheimers’s (Li et al., 2022). More importantly, people who eat the highest proportion of their diet in ultra-processed foods had a 22%-62% increased risk of death compared to the people who ate the lowest proportion of processed foods (van Tulleken, 2023). In the USA, counties with the highest food swamp scores (the availability of fast food outlets in a county) had a 77% increased odds of high obesity-related cancer mortality (Bevel et al., 2023). The increase risk has also been observed for cardiovascular disease, coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease and all cause mortality as is shown in figure 3 (Srour et al., 2019; Rico-Campà et al., 2019).

Figure 3. Association between consumption of ultra-processed foods and all cause mortality. Reproduced from Rico-Campà et al, 2019.

The harmful effects of UPF holds up even when correcting for the amount of sugars, carbohydrates or fats in the diet and controlling for socio economic variables.

The logic that underlies this perspective is based upon the writing by Nassim Taleb (2012) in his book, Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder (Incerto). He provides an evolutionary perspective and offers broad and simple rules of health as well as recommendations for reducing UPF risk factors:

- Assume that anything that was not part of our evolutionary past is probably harmful.

- Remove the unnatural/unfamiliar (e.g. smoking/ e-cigarettes, added sugars, textured proteins, gums, stabilizers (guar gum, sodium alginate), emulsifiers (mono-and di-glycerides), modified starches, dextrose, palm stearin, and fats, colors and artificial flavoring or other ultra-processed food additives).

What can we do?

The solutions are simple and stated by Michael Pollan in his 2007 New York Times article, “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly Plants.” Eat foods that your great grandmother would recognize as foods (Pollan, 2009). Do not eat any of the processed foods that fill a majority of a supermarket’s space.

- Buy only whole organic natural foods and prepare them yourself.

- Request that food companies only buy and sell non-processed foods.

- Demand government action to tax ultra-processed food and limit access to these foods. In reality, it is almost impossible to expect people to choose healthy, organic foods when they are more expensive and not easily available in the American ‘food swamps and deserts’ (the presence of many fast food outlets or the absence of stores that have fresh produce and non-processed foods). We do have a choice. We can spend more money now for organic, health promoting foods or, pay much more later to treat illness related to UPF.

- It is time to take our cues from the tobacco wars that led to regulating tobacco products. We may even need to start class action suits against producers and merchants of UPF for causing increased illness and premature morbidity.

For more background information and the science behind this blog, read, the book, Ultra-processed people, by Chris van Tulleken.

Look at the following blogs for more background information.

References

Bentley, R.A., Ormerod, P. & Ruck, D.J. (2018). Recent origin and evolution of obesity-income correlation across the United States. Palgrave Commun 4, 146. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-018-0201-x

Bero, L. A. (2005). Tobacco Industry Manipulation of Research. Public Health Reports (1974-), 120(2), 200–208. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20056773

Bevel, M.S., Tsai, M., Parham, A., Andrzejak, S.E., Jones, S., & Moore, J.X. (2023). Association of Food Deserts and Food Swamps With Obesity-Related Cancer Mortality in the US. JAMA Oncol. 9(7), 909–916. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2023.0634

Coca-Cola. (2023). More on Coca-Cola. Accessed July 14, 2023. https://www.coca-cola.co.uk/our-business/faqs/how-many-countries-sell-coca-cola-is-there-anywhere-in-the-world-that-doesnt

Johnson, R.K., Appel, L.J., Brands, M., Howard, B.V., Lefevre, M., Lustig, R.H., Sacks, F., Steffen, L.M., & Wylie–Rosett, J. (2009). Dietary sugars intake and cardiovascular health: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 120(10), 1011–1020. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192627

Li, H., Li, S., Yang, H., et al, 2022. Association of ultraprocessed food consumption with the risk of dementia: a prospective cohort study. Neurology, 99, e1056-1066. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000200871

Peper, E., Harvey, R. & Faass, N. (2020). TechStress: How Technology is Hijacking Our Lives, Strategies for Coping, and Pragmatic Ergonomics. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books, pp 18-22, 151. https://www.amazon.com/Beyond-Ergonomics-Prevent-Fatigue-Burnout/dp/158394768X/ref=sr_1_1?crid=1U9Y82YO4DKKP&keywords=erik+peper&qid=1689372466&sprefix=erik+peper%2Caps%2C187&sr=8-1

Pollan, M. (2007). Unhappy meals. The New York Times Magazine. https://www.nytimes.com/2007/01/28/magazine/28nutritionism.t.html

Pollan, M. (2009). Food Rules: An Eater’s Manual. New York: Penguin Books. https://www.amazon.com/Food-Rules-Eaters-Michael-Pollan/dp/014311638X/ref=tmm_pap_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=1689373484&sr=8-2

Rico-Campà, A., Martínez-González, M. A., Alvarez-Alvarez, I., de Deus Mendonça, R., Carmen de la Fuente-Arrillaga, C., Gómez-Donoso, C., & Bes-Rastrollo, M. (2019). Association between consumption of ultra-processed foods and all cause mortality: SUN prospective cohort study. BMJ; 365: l1949 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l1949

Roser, M. (2021).Smoking: How large of a global problem is it? And how can we make progress against it? Our world in data. Assessed July 13, 2023. https://ourworldindata.org/smoking-big-problem-in-brief

Srour, B., Fezeu, L.K., Kesse-Guyot, E.,Alles, B., Mejean, C…(2019). Ultra-processed food intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: prospective cohort study (NutriNet-Santé) BMJ,365:l1451. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l1451

Srour, B., Kordahi, M. C., Bonazzi, E., Deschasaux-Tanguy, M., Touvier, M., & Chassaing, B. (2022). Ultra-processed foods and human health: from epidemiological evidence to mechanistic insights. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(22)00169-8

Taleb, N. N. (2012). Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder (Incerto). New York: Random House Publishing Group. (Kindle Locations 5906-5908). https://www.amazon.com/Antifragile-Things-Disorder-ANTIFRAGILE-Hardcover/dp/B00QOJ6MLC/ref=sr_1_4?crid=3BISYYG0RPGW5&keywords=Antifragile%3A+Things+That+Gain+from+Disorder+%28Incerto%29&qid=1689288744&s=books&sprefix=antifragile+things+that+gain+from+disorder+incerto+%2Cstripbooks%2C158&sr=1-4

Van Tulleken, C. (2023). Ultra-processed people. The science behind food that isn’t food. New Yoerk: W.W. Norton & Company. https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/1324036729/ref=ox_sc_act_title_1?smid=ATVPDKIKX0DER&psc=1

United States Public Health Service. (1964). The 1964 Report on Smoking and Health. United States. Public Health Service. Office of the Surgeon General. https://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/spotlight/nn/catalog?f%5Bexhibit_tags%5D%5B%5D=smoking

Reflections on the increase in Autism, ADHD, anxiety and depression: Part 1-bonding, screen time, and circadian rhythm

Posted: July 4, 2023 Filed under: ADHD, behavior, computer, digital devices, education, emotions, Evolutionary perspective, health, laptops, screen fatigue, Uncategorized | Tags: anxiety, autism, bonding, circadian rhythms, depression, nature, still face experiment 3 Comments

Adapted from: Peper, E. Reflections on the increase in Autism, ADHD, anxiety and depression: Part 1-bonding, screen time, and circadian rhythms. NeuroRegulation,10(2), 134-138. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.10.2.134

Over the past two decades, there has been a significant increase in the prevalence of autism, Attention-Deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety, depression, and pediatric suicidal behavior. Autism rates have risen from 1 in 150 children in 2000 to 1 in 36 children in 2020 (CDC, 2023), while ADHD rates have increased from 6% in 1997 to approximately 10% in 2018 (CDC, 2022). The rates of anxiety among 18-25 year-olds have also increased from 7.97% in 2008 to 14.66% in 2018 (Goodwin et al., 2020), and depression rates for U.S. teens ages 12-17 have increased from 8% in 2007 to 13% in 2017 (Geiger & Davis, 2019; Walrave et al., 2022). Pediatric suicide attempts have also increased by 163% from 2009 to 2019 (Arakelyan et al., 2023), and during the COVID-19 pandemic, these rates have increased by more than 25% (WHO, 2022; Santomauro et al., 2021). In addition, the prevalence of these disorders has tripled for US adults during the pandemic compared to before (Ettman et al., 2020).

The rapid increase of these disorders is not solely due to improved diagnostic methods, genetic factors or the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic amplified pre-existing increasing trends. More likely, individuals who were at risk had their disorders triggered or amplified by harmful environmental and behavioral factors. Conceptually, Genetics loads the gun; epigenetics, behavior, and environment pull the trigger.

While behavioral strategies such as neurofeedback, Cognitive Behavior Therapy, biofeedback, meditation techniques, and pharmaceuticals can treat or ameliorate these disorders, the focus needs to be on risk reduction. In some ways, treatment can be likened to closing the barn doors after the horses have bolted.

Evolutionary perspective to reduce risk factors

Nassim Taleb (2012) in his book, Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder (Incerto), provides an evolutionary perspective and offers simple rules of health by reducing risk factors:

- Assume that anything that was not part of our evolutionary past is probably harmful.

- Remove the unnatural/unfamiliar (e.g. smoking/ e-cigarettes, sugar, digital media).

- We do not need evidence of harm to claim that a drug or an unnatural procedure is dangerous. If evidence of harm does not exist, it does not mean harm does not exist.

- Only resort to medical techniques when the health payoff is very large (to save a life), exceeds its potential harm, such as incontrovertibly needed surgery or life-saving medicine (penicillin).

- Avoid the iatrogenics and negative side effects of prescribed medication.

Writer and scholar Taleb’s suggestions are reminiscent of the perspective described by the educator Joseph C. Pearce (1993) in his book, Evolution’s End. Pearce argued that modern lifestyles have negatively affected the secure attachment and bonding between caregivers and infants. The lack of nurturing and responsive caregiving in early childhood may lead to long-term emotional and psychological problems. He points out that we have radically adapted behaviors that differ from those that evolved over thousands of generations and that allowed us to thrive and survive. In the last 100 years, babies have often been separated from their mothers at birth or early infancy by being put in a nursery or separate room, limited or no breastfeeding with the use of formula, exposure to television for entertainment, lack of exploratory play outdoors, and the absence of constant caretakers in high-stress and unsafe environments.

As Pearce pointed out, “If you want true learning, learning that involves the higher frontal lobes – the intellectual, creative brain – then again, the emotional environment must be positive and supportive. This is because at the first sign of anxiety the brain shifts its functions from the high, prefrontal lobes to the old defenses of the reptilian brain… These young people need audio-vocal communication, nurturing, play, body movement, eye contact, sweet sounds and close heart contact on a physical level” (Mercogliano & Debus, 1999).

To optimize health, eliminate or reduce those factors that have significantly changed or were not part of our evolutionary past. The proposed recommendations are based upon Talib’s perspective that anything that was not part of our evolutionary past is probably harmful; thus, it is wise to remove the unnatural/unfamiliar and adopt the precautionary principle, which states that if evidence of harm does not exist, it does not mean harm does not exist (Kriebel et al., 2010).

This article is the first of a three-part series. Part 1 focuses on increasing reciprocal communication between infant and caretaker, reducing screen time, and re-establishing circadian rhythms; Part 2 focuses on reducing exposure to neurotoxins, eliminating processed foods, and supporting the human biome; and Part 3 focuses on respiration and movement.

Part 1- Increase bonding, reduce screen time, and re-establish circadian rhythms

Increase bonding between infant and caretaker

Infants develop emotional communication through reciprocal interactions with their caregivers, during which the caregiver responds to the infant’s expressions. When this does not occur, it can be highly stressful and detrimental to the infant’s development. Unfortunately, more and more babies are emotionally and socially isolated while their caregivers are focussed on, and captured by, the content on their digital screens. Moreover, infants and toddlers are entertained (babysat) by cellphones and tablets instead of dynamically interacting with their caretakers. Screens do not respond to the child’s expressions; the screen content is programmed to capture the infant’s attention through rapid scene changes. Without reciprocal interaction, babies often become stressed, as shown by the research of developmental psychologist Professor Edward Tronick, who conducted the “Still Face” experiment (Tronick & Beeghly, 2011; Weinberg et al, 2008).

The “Still Face” experiment illustrated what happens when caregivers are not responding to infants’ communication. The caregivers were asked to remain still and unresponsive to their babies, resulting in the infants becoming increasingly distressed and disengaged from their surroundings. Not only does this apply to infants but also to children, teenagers and older individuals. Watch the short Still Face experiment, which illustrates what happens when the caretaker is not responding to the infant’s communication.

Recommendation. Do not use cellphone and digital media while being with an infant in the first two years of life. It is important for caregivers to limit their cellphone use and prioritize reciprocal interactions with their infants for healthy emotional and psychological development.

Reduce screen time (television, social media, streaming videos, gaming)[1]

From an evolutionary perspective, screen time is an entirely novel experience. Television, computers, and cellphones are modern technologies that have significantly impacted infants’ and young people’s development. To grow, infants, toddlers, and children require opportunities to explore the environment through movement, touch, and play with others, which is not possible with screens. Research has shown that excessive screen time can negatively affect children’s motor development, attention span, socialization skills, and contribute to obesity and other health problems (Hinkley et al., 2014; Carson et al., 2016; Mark, 2023).

When four-year-olds watch fast-paced videos, they exhibit reduced executive functions and impulse control, which may be a precursor for ADHD, compared to children who engage in activities such as drawing (Lillard & Peterson, 2011; Mark, 2023).

Furthermore, excessive screen time and time spent on social media are causal in increasing depression in young adults-–as was discovered when Facebook became available at selected universities. Researchers compared the mental health of students at similar universities where Facebook was or was not available and observed how the students’ mental health changed when Facebook became available (Braghieri et al., 2022). Their research showed that “College-wide access to Facebook led to an increase in severe depression by 7% and anxiety disorders by 20%. In total, the negative effect of Facebook on mental health appeared to be roughly 20% the magnitude of what is experienced by those who lose their job” (Walsh, 2022).

Exposure to digital media has also significantly reduced our attention span from 150 seconds in 2004 to an average of 44 seconds in 2021. The shortening of attention span may contribute to the rise of ADHD and anxiety (Mark, 2022, p. 96).

Recommendations: Reduce time spent on social media, gaming, mindlessly following one link after the other, or watching episode after episode of streaming videos. Instead, set time limits for screen use, turn off notifications, and prioritize in-person interactions with friends, family and colleagues while engaging in collaborative activities. Encourage children to participate in physical and social activities and to explore nature.

To achieve this, follow the guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics’ recommendation on screen time (Council on Communications and Media, 2016), which suggest these limits on screen time for children of different age groups:

- Children under 18 months of age should avoid all screen time, except for video chatting with family and friends.

- Children aged 18-24 months should have limited screen time, and only when watched together with a caretaker.

- Children aged 2 to 5 years should have no more than one hour of screen time per day with parental supervision.

- For adolescents, screen and social media time should be limited to no more than an hour a day.

In our experience, when college students reduce their time spent on social media, streaming videos, and texting, they report that it is challenging; however, they then report an increase in well-being and performance over time (Peper et al., 2021). It may require more effort to provide children with actual experiential learning and entertainment than allowing them to use screens, but it is worthwhile. Having children perform activities and play outdoors–in a green nature environment–appears to reduce ADHD symptoms (Louv, 2008; Kuo & Taylor, 2004).

Reestablish circadian (daily) rhythms

Our natural biological and activity rhythms were regulated by natural light until the 19th century. It is hard to imagine not having light at night to read, to work on the computer, or to answer email. However, light not only illuminates, but also affects our physiology by regulating our biological rhythms. Exposure to light at night can interfere with the production of melatonin, which is essential for sleep. Insufficient sleep affects 30% of toddlers, preschoolers, and school-age children, as well as the majority of adolescents. The more media is consumed at bedtime, the more bedtime is delayed and total sleep time is reduced (Hale et al., 2018). Reduced sleep is a contributing factor to increased ADHD symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity (Cassoff et al., 2012).

Recommendations: Support the circadian rhythms. Avoid screen time one hour before bedtime. This will reduce exposure to blue light and reduce sympathetic arousal triggered by the content on the screen or reactions to social media and emails. Sleep in total darkness, and establish a regular bedtime and waking time to avoid “social jetlag,” which can negatively affect health and performance (Caliandro et al., 2021). Implement sleep hygiene strategies such as developing a bedtime ritual to improve sleep quality (Stager et al., 2023; Suni, 2023). Thus, go to bed and wake up at the same time each day, including weekends. Avoid large meals, caffeine, and alcohol before bedtime. Consistency is key to success.

Conclusion

To optimize health, eliminate or reduce those factors that have significantly changed or were not part of our evolutionary past, and explore strategies that support behaviors that have allowed the human being to thrive and survive. Improve clinical outcomes and optimize health by enhancing reciprocal communication interactions, reducing screen time and re-establishing the circadian rhythm.

References

Arakelyan, M., Freyleue, S., Avula, D., McLaren, J.L., O’Malley, A.J., & Leyenaar, J.K. (2023). Pediatric Mental Health Hospitalizations at Acute Care Hospitals in the US, 2009-2019. JAMA, 329(12), 1000–1011. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2023.1992

Braghieri, L., Levy, R., & Makarin, A. (2022). Social Media and Mental Health (July 28, 2022). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3919760 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3919760

Caliandro, R., Streng, A.A., van Kerkhof, L.W.M., van der Horst, G.T.J., & Chaves, I. (2021). Social Jetlag and Related Risks for Human Health: A Timely Review. Nutrients, 13(12), 4543. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13124543

Carson, V., Tremblay, M.S., Chaput, J.P., & Chastin, S.F. (2016). Associations between sleep duration, sedentary time, physical activity, and health indicators among Canadian children and youth using compositional analyses. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab, 41(6 Suppl 3), S294-302. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2016-0026

Cassoff, J., Wiebe, S.T., & Gruber, R. (2012). Sleep patterns and the risk for ADHD: a review. Nat Sci Sleep, 4, 73-80. https://doi.org/10.2147/NSS.S31269

CDC. (2022). Attention-Deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): ADHD through the years. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Assessed March 27, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/timeline.html

CDC. (2023). Data & Statistics on Autism Spectrum Disorder. CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Assessed March 25, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data.html

Council on Communications and Media. (2016). Media and young minds. Pediatrics, 138(5), e20162591. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-2591

Ettman, C.K., Abdalla, S.M., Cohen, G.H., Sampson, L., Vivier, P.M.,& Galea, S. (2020), Prevalence of Depression Symptoms in US Adults Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw Open, 3(9):e2019686. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19686

Geiger, A.W. & Davis, L. (2019). A growing number of American teenagers-particularly girls-are facing depression. Pew Research Center. Accessed March 28, 2023.

Goodwin, R.D., Weinberger, A.H., Kim, J.H., Wu. M., & Galea, S. (2020). Trends in anxiety among adults in the United States, 2008-2018: Rapid increases among young adults. J Psychiatr Res. 130, 441-446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.08.014

Hale, L., Kirschen, G/W., LeBourgeois, M.K., Gradisar, M., Garrison, M.M., Montgomery-Downs, H., Kirschen, H., McHale, S.M., Chang, A.M., & Buxton, O.M. (2018). Youth Screen Media Habits and Sleep: Sleep-Friendly Screen Behavior Recommendations for Clinicians, Educators, and Parents. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am, 27(2),229-245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2017.11.014

Hinkley, T., Verbestel, V., Ahrens, W., Lissner, L., Molnár, D., Moreno, L.A., Pigeot, I., Pohlabeln, H., Reisch, L.A., Russo, P., Veidebaum, T., Tornaritis, M., Williams, G., De Henauw, S., De Bourdeaudhuij, I; IDEFICS Consortium. (2014). Early childhood electronic media use as a predictor of poorer well-being: a prospective cohort study. JAMA Pediatr,. May;168(5):485-92. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.94

Kriebel, D., Tickner, J., Epstein, P., Lemons, J., Levins, R., Loechler, E.L., Quinn, M., Rudel, R., Schettler, T., Stoto, M. (2001). The precautionary principle in environmental science. Environ Health Perspect, 109(9):871-6. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.01109871

Kuo. F.E. & Taylor, A.F. (2004). A potential natural treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: evidence from a national study. Am J Public Health. 94(9),1580-6. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.94.9.1580

Lillard, A.S. & Peterson, J. The immediate impact of different types of television on young children’s executive function. Pediatrics, 128(4), 644-9. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-1919

Louv, R. (2008). Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder. Algonquin Books. Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books

Mark, G. (2023). Attention Span: A Groundbreaking Way to Restore Balance, Happiness and Productivity. Toronto, Canada: Hanover Square Press.

Mercogliano, C. & Debus, K. (1999). Nurturing Heart-Brain Development Starting With Infants 1999 Interview with Joseph Chilton Pearce. Journal of Family Life, 5(1). https://www.michaelmount.co.za/nurturing-heart-brain-development-starting-with-infants-1999-interview-with-joseph-chilton-pearce/

Pearce, J.C. (1993). Evolutions’s End. New York: HarperOne.

Peper, E., Wilson, V., Martin, M., Rosegard, E., & Harvey, R. (2021). Avoid Zoom fatigue, be present and learn. NeuroRegulation, 8(1), 47–56. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.8.1.47

Santomauro, D.F., Mantilla Herrera, A.M., Shadid, J., Zheng, P., Ashbaugh, C., Pigott, D.M., Abbafati, C., Adolph, C., …. (2021). Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet, 398(103121700-1712., https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02143-7

Stager, L.M., Caldwell, A., Bates, C., & Laroche, H. (2023). Helping kids get the sleep they need. Society of Behavioral Medicine. Accessed March 29, 2023 https://www.sbm.org/healthy-living/helping-kids-get-the-sleep-they-need?gclid=Cj0KCQjww4-hBhCtARIsAC9gR3ZM7v9VSvqaFkLnceBOH1jIP8idiBIyQcqquk5y_RZaNdUjAR9Wpx4aAhTBEALw_wcB

Suni, E. (2023). Sleep hygiene- What it is, why it matters, and how to revamp your habits to get better nightly sleep. Sleep Foundation. Accessed March 29, 2023. https://www.sleepfoundation.org/sleep-hygiene

Taleb, N. N. (2012). Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder (Incerto) Random House Publishing Group. (Kindle Locations 5906-5908).

Tronick, E. & Beeghly, M. (2011).Infants’ meaning-making and the development of mental health problems. Am Psychol, 66(2),107-19. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021631

Walrave, R., Beerten, S.G., Mamouris, P. et al. Trends in the epidemiology of depression and comorbidities from 2000 to 2019 in Belgium. BMC Prim. Care 23, 163 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-022-01769-w

Walsh, D. (2022 September 14). Study: Social media use linked to decline in mental health. MIT Management Ideas Made to Matter. Accessed March 28, 2023. https://mitsloan.mit.edu/ideas-made-to-matter/study-social-media-use-linked-to-decline-mental-health#:~:text=College%2Dwide%20access%20to%20Facebook,with%20either%20psychotherapy%20or%20antidepressants

Weinberg, M.K., Beeghly, M., Olson, K.L., & Tronick, E. (2008). A Still-face Paradigm for Young Children: 2½ Year-olds’ Reactions to Maternal Unavailability during the Still-face. J Dev Process, 3(1):4-22. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22384309/

WHO (2022). COVID-19 pandemic triggers 25% increase in prevalence of anxiety and depression worldwide. World Health Organization. Assessed march 26, 2023. https://www.who.int/news/item/02-03-2022-covid-19-pandemic-triggers-25-increase-in-prevalence-of-anxiety-and-depression-worldwide

[1] The critique of social media does not imply that there are no benefits. If used judiciously, it is a powerful tool to connect with family and friends or access information.

Mouth breathing and tongue position: a risk factor for health

Posted: June 8, 2023 Filed under: ADHD, behavior, Breathing/respiration, cognitive behavior therapy, Evolutionary perspective, healing, health, Nutrition/diet, self-healing, Uncategorized | Tags: babies, breastfeedging, development, infants, jaw, mouth breathing, neurocognitive develoment, nose breathing, sleep, tongue-tie Leave a commentErik Peper, PhD, BCB and Ron Swatzyna, PhD, LCSW, BCB, BCN

Adapted from: Peper, E., Swatzyna, R., & Ong, K. (2023). Mouth breathing and tongue position: a risk factor for health. Biofeedback. 51(3), 74–78 https://doi.org/10.5298/912512

Breathing usually occurs without awareness unless there are problems such as asthma, emphysema, allergies, or viral infections. Infant and child development may affect how we breathe as adults. This blog discusses the benefits of nasal breathing, factors that contribute to mouth breathing, how babies’ breastfeeding and chewing decreases the risk of mouth breathing, recommendations that parents may implement to support healthy development of a wider palate, and the embedded video presentation, How the Tongue Informs Healthy (or Unhealthy) Neurocognitive Development, by Karindy Ong, MA, CCC-SLP, CFT, .

Benefits of nasal breathing

Breathing through the nose filters, humidifies, warms, or cools the inhaled air as well as reduces the air turbulence in the upper airways. In addition, the epithelial cells of the nasal cavities produce nitric oxide that are carried into the lungs when inhaling during nasal breathing (Lundberg & Weitzberg, 1999). The nitric oxide contributes to healthy respiratory function by promoting vasodilation, aiding in airway clearance, exerting antimicrobial effects, and regulating inflammation. Breathing through the nose is associated with deeper and slower breathing rate than mouth breathing. This slower breathing also facilitates sympathetic parasympathetic balance and reduces airway irritation.

Mouth breathing

Some people breathe predominantly through their mouth although nose breathing is preferred and health promoting. Mouth breathing negatively impacts the ability to perform during the day as well as affect our cognitions and mood (Nestor, 2020). It contributes to disturbed sleep, snoring, sleep apnea, dry mouth upon waking, fatigue, allergies, ear infections, attention deficit disorders, crowded mis-aligned teeth, and poorer quality of life (Kahn & Ehrlich, 2018). Even the risk of ear infections in children is 2.4 time higher for mouth breathers than nasal breathers (van Bon et al, 1989) and nine and ten year old children who mouth breath have significantly poorer quality of life and have higher use of medications (Leal et al, 2016).

One recommendation to reduce mouth breathing is to tape the mouths closed with mouth tape (McKeown, 2021). Using mouth tape while sleeping bolsters nose breathing and may help people improve sleep, reduce snoring, and improves alertness when awake (Lee et al, 2022).

Experience how mouth breathing affects the throat and upper airway

Inhale quickly, like a gasp, as much air as possible through your open mouth. Exhale letting the air flow out through your mouth. Repeat once more.

Inhale quickly as much air through the nose, then exhale by allow the airflow out through the nose. Repeat once more.

What did you observe? Many people report that rapidly inhaling through the mouth causes the back of the throat and even upper airways to feel drier and irritated. This does not occur when inhaling through the nose. This simple experiment illustrates how habitual mouth breathing may irritate the airways.

Developmental behavior that contributes to mouth breathing

The development of mouth breathing may begin right at birth when the mouth, tongue, jaw and nasal area are still developing. The arch of the upper palate forms the roof of the oral cavity that separates the oral and nasal cavities. When the palate and jaw narrows, the arch of the palate increases and pushes upwards into the nasal area. This reduces space in the nasal cavity for the air to flow and obstructs nasal breathing. The highly vaulted palate is not only genetically predetermined but also by how we use our tongue and jaw from birth. The highly arched palate is only a recent anatomical phenomena since the physical structure of the upper palate and jaw from the pre- industrial era was wider (less arched upper palate) than many of our current skulls (Kahn & Ehrlich, 2018).

The role of the tongue in palate development

After babies are born, they breastfeed by sucking with the appropriate tongue movements that help widen the upper palate and jaw. On the other hand, when babies are bottle fed, the tongue tends to move differently which causes the cheek to pull in and the upper palate to arch which may create a high narrow upper palate and making the jaw narrower. There are many other possible factors that could cause mouth breathing such as tongue-tie (ankyloglossia), septal deviation, congenital malformation, enlarged adenoids and tonsils (Aden tonsillar hyperplasia), inflammatory diseases such as allergic rhinitis (Trabalon et al, 2012). Whatever the reasons, the result of the impoverished tongue movement and jaw increases the risk for having a higher arched upper palate that impedes nasal breathing and contributes to habitual mouth breathing.

The forces that operate on the mouth, jaw and palate during bottle feeding may be similar to when you suck on straw and the cheeks coming in with the face narrowing. The way the infants are fed will change the development of the physical structure that may result in lifelong problems and may contribute to developing a highly arched palate with a narrow jaw and facial abnormalities such as long face syndrome (Tourne, 1990).

To widen the upper palate and jaw, the infant needs to chew, chew and tear the food with their gums and teeth. Before the industrialization of foods, children had to tear food with their teeth, chew fibrous foods or gnaw at the meat on bones. The chewing forces allows the jaw to widen and develop so that when the permanent teeth are erupting, they would more likely be aligned since there would be enough space–eliminating the need for orthodontics. On the other hand, when young children eat puréed and highly processed soft foods (e.g., cereals soaked in milk, soft breads), the chewing forces are not powerful enough to encourage the widening of the palate and jaw.

Although the solution in adults can be the use of mouth tape to keep the mouth closed at night to retrain the breathing pattern, we should not wait until we have symptoms. The focus needs to be on prevention. The first step is an assessment whether the children’s tongue can do its job effectively or limited by tongue-tie and the arch of the palate. These structures are not totally fixed and can change depending on our oral habits. The field of orthodontics is based upon the premise that the physical structure of the jaw and palate can be changed, and teeth can be realigned by applying constant forces with braces.

Support healthy development of the palate and jaw

Breastfeed babies (if possible) for the first year of life and do NOT use bottle feeding. When weaning, provide chewable foods (fruits, vegetable, roots, berries, meats on bone) that was traditionally part of our pre-industrial diet. These foods support in infants’ healthy tongue and jaw development, which helps to support the normal widening of the palate to provide space for nasal breathing.

Provide fresh organic foods that children must tear and chew. Avoid any processed foods which are soft and do not demand chewing. This will have many other beneficial health effects since processed foods are high in simple carbohydrates and usually contain color additives as well as traces of pesticides and herbicides. The highly processed foods increase the risk of developing depression, type 2 diabetes, inflammatory disease, and colon cancer (Srour et al., 2019).

Sadly, the USA allows much higher residues of pesticide and herbicides that act as neurotoxins than are allowed in by the European Union. For example, the acceptable level of the herbicide glyphosate (Round-Up) is 0.7 parts per million in the USA while in the acceptable level is 0.01 parts per million in European countries (Tano, 2016; EPA, 2023; European Commission, 2023). The USA allows this higher exposure even though about half of the human gut microbiota are vulnerable to glyphosate exposure (Puigbò et al., 2022).

The negative effects of herbicides and pesticides are harmful for growing infants. Even fetal exposure from the mother (gestational exposure) is associated with an increase in behaviors related to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorders and executive function in the child when they are 7 to 12 years old (Sagiv et al., 2021) and organophosphate exposure is correlated with ADHD prevalence in children (Bouchard et al., 2010).

To implement these basic recommendations are very challenging. It means the mother has to breastfeed her infant during the first year of life. This is often not possible because of socioeconomic inequalities; work demands and medical complications. It also goes against the recent cultural norm that fathers should participate in caring for the baby by giving the baby a bottle of stored breast milk or formula.

From our perspective, women who give birth must have a year paid maternity leave to provide their infants with the best opportunity for health (e.g., breast-feeding, emotional bonding, and reduced financial stress). As a society, we have the option to pay the upfront cost now by providing a year- long maternity leave to mothers or later pay much more costs for treating chronic conditions that may have developed because we did not support the natural developmental process of babies.

Relevance to the field of neurofeedback and biofeedback

Clinicians often see clients, especially children with diagnostic labels such as ADHD who have failed to respond to numerous psychotherapies and pharmacotherapies. In the recent umbrella review and meta-analytic evaluation of recent meta-analyses, Leichsenring et al. (2022) found only small benefits overall for both types of intervention. They suggest that a paradigm shift in research seems to be required to achieve further progress in resolving mental health issues. As the past director of National Institute of Health, Dr. Thomas Insel pointed out that the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is not a valid instrument and should be a big wake up call for all of us to think outside the box (Insel, 2009). One factor that starts right at birth is the oral cavity development by dysfunctional tongue movements.

We want to make all of you aware of a serious issue in children that you may come across. For those of us who work with children children, we need to ask their parents about the following: tongue-tie, mouth breathing, bedwetting, high-vaulted palate, thumb sucking, abnormal eating issues, apraxia, dysarthria, and hypotonia. Research suggests that the palates of these children are so arched that the tongue cannot do its job effectively, causing multiple issues which may be related.

Please view the webinar from May 17, 2023. Presented by Karindy Ong, MA, CCC-SLP, CFT, How the Tongue Informs Healthy (or Unhealthy) Neurocognitive Development. The presentation explains the developmental process of the role the tongue plays and how it contributes to nasal breathing. Please pass it on to others who may have interest.

References

Bouchard, M.F., Bellinger, D.C., Wright, R.O., & Weisskopf, M.G. (2010). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and urinary metabolites of organophosphate pesticides. Pediatrics, 125(6), e1270-7. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-3058

EPA. (2023). Glyphosate. United States Environmental Protection Agency. Accessed April 1, 2023. https://www.epa.gov/ingredients-used-pesticide-products/glyphosate

European Commission. (2023). EU legislation on MRLs.Food Safety. Assessed April 1, 2023. https://food.ec.europa.eu/plants/pesticides/maximum-residue-levels/eu-legislation-mrls_en#:~:text=A%20general%20default%20MRL%20of,e.g.%20babies%2C%20children%20and%20vegetarians.

Insel, T.R. (2009). Translating scientific opportunity into public health impact: a strategic plan for research on mental illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 66(2), 128-133. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.540

Kahn, S. & Ehrlich, P.R. (2018). Jaws. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. https://www.amazon.com/Jaws-Hidden-Epidemic-Sandra-Kahn/dp/1503604136/ref=tmm_hrd_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=1685135054&sr=1-1

Leal, R.B., Gomes, M.C., Granville-Garcia, A.F., Goes, P.S.A., & de Menezes, V.A. (2016). Impact of Breathing Patterns on the Quality of Life of 9- to 10-year-old Schoolchildren. American Journal of Rhinology & Allergy, 30(5):e147-e152. https://doi.org/10.2500/ajra.2016.30.4363

Lee, Y.C., Lu, C.T., Cheng, W.N., & Li, H.Y. (2022).The Impact of Mouth-Taping in Mouth-Breathers with Mild Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Preliminary Study. Healthcare (Basel), 10(9), 1755. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10091755

Leichsenring, F., Steinert, C., Rabung, S. and Ioannidis, J.P.A. (2022), The efficacy of psychotherapies and pharmacotherapies for mental disorders in adults: an umbrella review and meta-analytic evaluation of recent meta-analyses. World Psychiatry, 21: 133-145. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20941

Lundberg, J.O. & Weitzberg, E. (1999). Nasal nitric oxide in man. Thorax. (10):947-52. https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.54.10.947

McKeown, P. (2021). The Breathing Cure: Develop New Habits for a Healthier, Happier, and Longer Life. Boca Raton, Fl “Humanix Books. https://www.amazon.com/BREATHING-CURE-Develop-Healthier-Happier/dp/1630061972/

Nestor, J. (2020). Breath: The New Science of a Lost Art. New York: Riverhead Books. https://www.amazon.com/Breath/dp/0593191358/ref=tmm_pap_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=1686191995&sr=8-1

Puigbò, P., Leino, L. I., Rainio, M. J., Saikkonen, K., Saloniemi, I., & Helander, M. (2022). Does Glyphosate Affect the Human Microbiota?. Life, 12(5), 707. https://doi.org/10.3390/life12050707

Sagiv, S.K., Kogut, K., Harley, K., Bradman, A., Morga, N., & Eskenazi, B. (2021). Gestational Exposure to Organophosphate Pesticides and Longitudinally Assessed Behaviors Related to Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Executive Function, American Journal of Epidemiology, 190(11), 2420–2431. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwab173

Srour, B. et al. (2019). Ultra-processed food intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: prospective cohort study (NutriNet-Santé).BMJ, 365. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l1451

Tano, B. (2016). The Layman’s Guide to Integrative Immunity. Integrative Medical Press. https://www.amazon.com/Laymans-Guide-Integrative-Immunity-Discover/dp/0983419299/_

Tourne, L.P. (1990). The long face syndrome and impairment of the nasopharyngeal airway. Angle Orthod, 60(3):167-76. https://doi.org/10.1043/0003

Trabalon, M. & Schaal, B. (2012). It takes a mouth to eat and a nose to breathe: abnormal oral respiration affects neonates’ oral competence and systemic adaptation. Int J Pediatr, 207605. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/207605

van Bon, M.J., Zielhuis, G.A., Rach, G.H., & van den Broek, P. (1989). Otitis media with effusion and habitual mouth breathing in Dutch preschool children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol, (2), 119-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-5876(89)90087-6

Healing from vulvodynia

Posted: May 4, 2023 Filed under: behavior, biofeedback, Breathing/respiration, emotions, healing, health, Pain/discomfort, relaxation, self-healing, Uncategorized | Tags: muscle tension, pelvic floor pain, therapeutic relationship, triggers for illness, vulvodynia Leave a commentPamela Jertberg and Erik Peper

Adapted from: Jertberg, P. & Peper, E. (2023). The healing of vulvodynia from the client’s perspective. Biofeedback, 51 (1), 18–21. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-51.01.02

This introspective report describes how a young woman who experienced a year-long struggle with vulvodynia, or vulvar vestibulitis, regained her health through biofeedback training and continues to be symptom-free 7 years after the intervention. This perspective may offer insight into factors that promote health and healing and provide an approach to reduce symptoms and promote health. The methodology of this case was described previously by Peper et al. (2015).

The Client’s Experience

I have been a healthy young woman my whole life. Growing up in a loving, dedicated family, I always ate home-cooked meals, went to bed at a reasonable time, and got plenty of exercise by playing with my family members and friends. I never once thought that at age 23 I might be at risk of undergoing vulvar surgery. There are many factors that contributed to the genesis of my vulvar pain, and many other factors that worsened this pain. Traditional medicine did not help me, and I did not find relief until I met my biofeedback practitioner, who taught me biofeedback. Through the many strategies I learned, such as visualization, diaphragmatic breathing techniques, diet tips, and skills to reframe my thoughts, I finally began to feel relief and hope. Practicing all these elements every day helped me overcome my physical pain and enjoy a normal life once again. Today, I do not have any vulvar discomfort. I am so grateful to my biofeedback practitioner for the many skills he taught me. I can enjoy my daily activities once again without experiencing pain. I have been given a second chance at loving life, and now I have learned the techniques that will help me sustain a more balanced path for the rest of my life. Seven years later, I am healthy and have no symptoms.

Triggers for Illness

Not Having a Positive Relationship with the Doctor

The first factor that aggravated my pain was having a doctor with whom I did not have a good relationship. Although the vulvar specialist I was referred to had treated hundreds of women with vulvar vestibulitis, his methods were very traditional: medicine, low oxalate diet, ointments, and surgery. Whenever I left his office, I would cry and feel like surgery was the only option. Vaginal surgery at 23 was one of the scariest and most unexpected thoughts my brain had ever considered. The doctor never thought of the impact that his words and treatment would have on my mental state.

Depression

Being depressed also triggered more pain. Whenever I would have feelings of hopelessness and create irrational beliefs in my mind (“I will never get better,” “I will never have sex again,” “I am not a woman anymore”), my physical pain would increase. Having depression only triggered more depression and pain, and this became a vicious cycle. The depression deeply affected my relationships with my boyfriend, friends, and family and my performance in my college classes.

Being Sedentary

Being sedentary and not exercising also increased my pain. At first, I believed that the mere act of sitting down hurt me due to the direct pressure on the area, but after a few months I came to realize that it was inactivity itself that triggered pain. Whenever I would sit for too long writing a paper or I would stay home all day because of my depression, my pain would increase, perhaps because I was inhibiting circulation. Still, when I am inactive most of the day, I feel lethargic and bloated. When I exercise, the pain goes away 100%. Exercise is almost magical.

Stress

Stress is the worst trigger for pain. Throughout my life, I always strived to be perfect in every way, meaning I was stressed about the way I looked, performed in school, drove, etc. Through the sessions with my biofeedback practitioner, I learned that my body was in a state of perpetual stress and tightness, which induced pain in certain areas. My body’s way of releasing such tension was to send pain signals to my vulvar area, perhaps because of a yeast infection a couple of months back. Still, if I become very stressed, I will feel pain or tightness in certain parts of my body, but now I have strategies for performing proper stress-relieving techniques.

Processed Foods

Junk food affects me instantly. When I eat processed foods for a week straight, I feel groggy, bloated, lethargic, and in pain. Processed sugar, white flour, and salt are a few of the foods that make the pain increase. I used to love sugar, so I would enjoy the occasional milkshake and cheeseburger and feel mostly okay. However, in times of stress it became crucial for me to learn to refrain from any junk food, because it would worsen my vulvar pain and increase my overall stress levels.

Menstruation

Menstruation is unavoidable, and unfortunately it would always worsen my vulvar pain. Right about the time of my period, my sensitivity and pain would massively increase. Sometimes as my pain would increase incredibly, I would question myself: “What am I doing wrong?” Then, I would remember: “Oh yes, I am getting my period in a few days.” The whole area became very sensitive and would get irritated easily. It became imperative to listen to my body and nurture myself especially around that time of the month.

Triggers for Healing

A Good Doctor

Just as I learned which factors triggered the pain, I also learned how to reduce it. The most important factor that helped me find true relief was meeting a good health professional (which could be a healer, nurse, or professor). The first time I met my biofeedback practitioner and told him about my issues, he really listened, gave me positive feedback, and even made jokes with me. To this day we still have a friendship, which has really aided me in getting better. In contrast to the vulvar specialist, I would leave the biofeedback practitioner’s office feeling powerful, able to defeat vulvodynia, and truly happy. Just having this support from a professional (or a friend, boyfriend, or relative) can make all the difference in the world. I don’t know where I would be right now if I hadn’t worked with him.

Positive Thoughts and Beliefs

Along with having a good support group, having positive thoughts and believing in a positive result helped me greatly. When I actually set my mind to feel “happy” and to believe that I was getting better, I began to really heal. After months of being depressed and feeling incomplete, when I began to practice mantras such as “I am healing,” “I am healthy,” and “I am happy,” my pain began to go away, and I was able to reclaim my life.

Journaling

One of the ways in which “happiness” became easier to achieve was to journal every day. I would write everything: from my secrets to what I ate, my pain levels, my goals for the day, and my symptoms. Writing down everything and knowing that no one would ever read it but me gave me relief, and my journal became my confidante. I still journal every day, and if I forget to write, the next day I will write twice as much. Now that writing has become a habit and a hobby, it is hard to imagine my life without that level of introspection.

Meditation

Although I would do yoga often, I would never sit and meditate. I began to use Dr. Peper’s guided meditations and Dr. Kabat-Zinn’s CD (Kabat-Zinn, 2006; Peper et al., 2002). The combination of these meditation techniques, whether on different days or on the same day, helped me focus on my breathing and relax my muscles and mind. Today, I meditate at least 20 min each day, and I feel that it helps me see life through a more willing and patient perspective. In addition, through meditation and deep breathing I have learned to control my pain levels, concentration, and awareness.

Imagery and Visualization

Imagery is a powerful tool that allowed me to heal faster. My biofeedback practitioner instructed me to visualize how I wanted to feel and look. In addition, he suggested that I draw and color how I was feeling at any given moment, my imagined healing process, and how I would look and feel after the healing process had traveled throughout my body (Peper et al., 2022). It is still amazing to me how much imagery helped me. Even visualizing here and there throughout the day helped. Now I envision how I want to feel as a healthy woman, I take a deep breath, and as a I breathe out I let my imagined healing process go through my body into all my tight areas along with the exhalation.

Biofeedback

Biofeedback is the single strategy that helped me the most. During my first session with my biofeedback practitioner, he pointed out that my muscles were always contracted and stressed and that I was not breathing diaphragmatically. As I learned how to take deep belly breaths, I began to feel the tight areas in my body loosen up. I started to practice controlled breathing 20 min every day. Through biofeedback, my body and muscles became more relaxed, promoting circulation and ultimately reducing the vulvar pain.

Regular Exercise and Yoga

Exercising daily decreased my pain and improved the quality of my life greatly. When I first started experiencing significant vulvar pain, I stopped exercising because I felt that movement would aggravate the pain. To my surprise, the opposite was true. Being sedentary increased the feelings of discomfort, whereas exercising released the tension. The exercise I found most helpful was yoga because it is meditation in movement. I became so focused on my breathing and the poses that my brain did not have time to think about anything else. After attending every yoga class, I felt like I could take on anything. Swimming, Pilates, and gentle cardiovascular exercises have also helped me greatly in reducing stress and feeling great.

Sex

Although sex was impossible for almost a year due to the pain, it became possible and even enjoyable after implementing other relaxation strategies. When I first reintroduced sex back into my life, my partner at the time and I would go gently and stop if it hurt my vulvar area at all. Today, sex again is joyful. Being able to engage in intercourse has boosted my self-esteem and helped me feel sexy again, which empowers me to keep practicing the relaxation techniques.

Listening to the Mind-Body Connection

The mind-body connection is present in all of us, but I am fortunate to have a very strong connection. My thoughts influence my body almost instantly, which is why when I would get depressed my pain would increase, and when I would see my biofeedback practitioner or believe in a good outcome, my pain would decrease. Being aware of this connection is crucial because it can help me or hurt me greatly. After a few months of practicing the relaxation strategies, I saw a different gynecologist and one dermatologist. Both professionals said that there was nothing wrong with my vulvar area—that maybe I just felt some irritation due to the medicines I had previously taken and my current stress. They said that there was no way I needed surgery. When I heard these opinions, I began to feel instantly better—thus proving that my thoughts (and even others’ thoughts) affect my body in significant ways.

Although today I am 100% better, I still experience pain and tightness in my body when I experience the “illness factors” I mentioned above. I still have to remember that feeling healthy and good is a process, not a result, and that even if I feel better one day that does not mean I can stop all my new healthy habits. To completely cure vulvodynia, I needed to change my life habits, perspective, and attitude toward the illness and life. I needed to make significant changes, and now my biggest challenge is to stick to those changes. Biofeedback, imagery, meditation, good food, and exercise are not just treatments that I begin and end on a certain day, but rather they have become essential components of my life forever.

My life with vulvodynia was ultimately a journey of introspection, decision making, and life-changing habits. I struggled with vulvar pain for over a year, and during that year I experienced severe symptoms, depression, and the loss of several friendships and relationships. I felt old, hopeless, useless, and powerless. When I began to incorporate biofeedback, relaxation techniques, journaling, visualization, a proper diet, and regular exercise, life took a turn for the better. Not only did my vulvar pain begin to decrease, but the quality of my overall life improved and I regained the self-confidence I had lost. I became happy, hopeful, and proactive. Even though I practiced the relaxation strategies every day, the pain did not go away in a day or even a month. It took me several months of diligent practice to truly heal my vulvar pain. Even today, such practices have carried on to all areas of my life, and now there is not a day when I do not meditate, even for 5 min.

As paradoxical as it may seem, vulvodynia was a blessing in disguise. I believe that vulvodynia was my body’s way of signaling to me that many areas of my life were in perpetual stress: my pelvic floor, my thoracic breathing, my romantic relationship at the time, etc. When I learned to let go and truly embrace my life, I began to feel relief. I became less irritable and more patient and understanding, with both my body and the outside world. The best advice I can give a woman with vulvar symptoms or any person with otherwise inexplicable chronic pain is to apply the strategies that work for you and stick to them every day—even on the days when you want to go astray. When I started to focus on what my body needed to be nurtured and to live my life and do the things I truly wanted to do, I became free. Today, I live in a way that allows me to find peace, serenity, pride, and fun. I live exactly the way I want to, and I find the time to follow my passions. Vulvodynia, or any kind of chronic pain, does not define who we are. We define who we are.

Conclusion

This introspective account of the client’s personal experience with biofeedback suggests that healing is multidimensional. We suggest that practitioners use a holistic approach, which can provide hope and relief to clients who suffer from vulvodynia or other disorders that are often misunderstood and underreported.

Useful blogs

References

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2006). Coming to our senses: Healing ourselves and the world through mindfulness. Hachette Books

Peper, E., Cosby, J. & Almendras, M. (2022). Healing chronic back pain. NeuroRegulation, 9(3), 164–172. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.9.3.164

Peper, E., Gibney, K.H, & Holt, C.F. (2002. Make health happen: Training yourself to create wellness. Kendall/Hunt.

Peper, E. Martinex, Aranda, P. & Moss, D. (2015). Vulvodynia treated successfully with breathing biofeedback and integrated stress reduction: A case report. Biofeedback, 43(2), 103–109. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-43.2.04

Hope for menstrual cramps (dysmenorrhea) with breathing

Posted: April 22, 2023 Filed under: behavior, biofeedback, Breathing/respiration, healing, health, meditation, Pain/discomfort, posture, relaxation, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: dysmenorrhea, Imagery, menstrual cramps, stroking, visualization 1 CommentAdapted from: Peper, E., Chen, S., Heinz, N., & Harvey, R. (2023). Hope for menstrual cramps (dysmenorrhea) with breathing. Biofeedback, 51(2), 44–51. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-51.2.04

“I have always had extremely painful periods. They would get so painful that I would have to call in sick and take some time off from school. I have been to many doctors and medical professionals, and they told me there is nothing I could do. I am currently on birth control, and I still get some relief from the menstrual pain, but it would mess up my moods. I tried to do the diaphragmatic breathing so that I would be able to continue my life as a normal woman. And to my surprise it worked. I was simply blown away with how well it works. I have almost no menstrual pain, and I wouldn’t bloat so much after the diaphragmatic breathing.” -22 year old student

Each semester numerous students report that their cramps and dysmenorrhea symptoms decrease or disappear during the semester when they implement the relaxation and breathing practices that are taught in the semester long Holistic Health class. Given that so many young women suffer from dysmenorrhea, many young women could benefit by using this integrated approach as the first self-care intervention before relying on pain reducing medications or hormones to reduce pain or inhibit menstruation. Another 28-year-old student reported:

“Historically, my menstrual cramps have always required ibuprofen to avoid becoming distracting. After this class, I started using diaphragmatic breath after pain started for some relief. True benefit came when I started breathing at the first sign of discomfort. I have not had to use any pain medication since incorporating diaphragmatic breath work.”

This report describes students practicing self-regulation and effortless breathing to reduce stress symptoms, explores possible mechanisms of action, and suggests a protocol for reducing symptoms of menstrual cramps. Watch the short video how diaphragmatic breathing eliminated recurrent severe dysmenorrhea (pain and discomfort associated with menstruation).

Background: What is dysmenorrhea?

Dysmenorrhea is one of the most common conditions experienced by women during menstruation and affects more than half of all women who menstruate (Armour et al., 2019). Most commonly dysmenorrhea is defined by painful cramps in the lower abdomen often accompanied by pelvic pain that starts either a couple days before or at the start of menses. Symptoms also increase with stress (Wang et al., 2003) with pain symptoms usually decreasing in severity as women get older and, after pregnancy.

Economic cost of dysmenorrhea

Dysmenorrhea can significantly interfere with a women’s ability to be productive in their occupation and/or their education. It is “one of the leading causes of absenteeism from school or work, translating to a loss of 600 million hours per year, with an annual loss of $2 billion in the United States” (Itani et al, 2022). For students, dysmenorrhea has a substantial detrimental influence on academic achievement in high school and college (Thakur & Pathania, 2022). Despite the frequent occurrence and negative impact in women’s lives, many young women struggle without seeking or having access to medical advice or, without exploring non-pharmacological self-care approaches (Itani et al, 2022).

Treatment

The most common pharmacological treatments for dysmenorrhea are nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (e.g., Ibuprofen, Aspirin, and Naproxen Sodium) along with hormonal contraceptives. NSAIDs act by preventing the action of cyclooxygenase which prevents the production of prostaglandins. Itani et al (2022) suggested that prostaglandin production mechanisms may be responsible for the disorder. Hormonal contraceptives also prevent the production of prostaglandins by suppressing ovulation and endometrial proliferation.

The pharmacological approach is predominantly based upon the model that increased discomfort appears to be due to an increase in intrauterine secretion of prostaglandins F2α and E2 that may be responsible for the pain that defines this condition (Itani et al, 2022). Pharmaceuticals which influence the presence of prostaglandins do not cure the cause but mainly treat the symptoms.

Treatment with medications has drawbacks. For example, NSAIDs are associated with adverse gastrointestinal and neurological effects and also are not effective in preventing pain in everyone (Vonkeman & van de Laar, 2010). Hormonal contraceptives also have the possibility of adverse side effects (ASPH, 2023). Acetaminophen is another commonly used treatment; however, it is less effective than other NSAID treatments.

Self-regulation strategies to reduce stress and influence dysmenorrhea

Common non-pharmacological treatments include topical heat application and exercise. Both non-medication approaches can be effective in reducing the severity of pain. According to Itani et al. (2022), the success of integrative holistic health treatments can be attributed to “several mechanisms, including increasing pelvic blood supply, inhibiting uterine contractions, stimulating the release of endorphins and serotonin, and altering the ability to receive and perceive pain signals.”

Although less commonly used, self-regulation strategies can significantly reduce stress levels associated menstrual discomfort as well as reduce symptoms. More importantly, they do not have adverse side effects, but the effectiveness of the intervention varies depending on the individual.

- Autogenic Training (AT), is a hundred year old treatment approach developed by the German psychiatrist Johannes Heinrich Schultz that involves three 15 minute daily practice of sessions, resulted in a 40 to 70 percent decrease of symptoms in patient suffering from primary and secondary dysmenorrhea (Luthe & Schultz, 1969). In a well- controlled PhD dissertation, Heczey (1978) compared autogenic training taught individually, autogenic training taught in a group, autogenic training plus vaginal temperature training and a no treatment control in a randomized controlled study. All treatment groups except the control group reported a decrease in symptoms and the most success was with the combined autogenic training and vaginal temperature training in which the subjects’ vaginal temperature increased by .27 F degrees.

- Progressive muscle relaxation developed by Edmund Jacobson in the 1920s and imagery are effective treatments for dysmenorrhea (Aldinda et al., 2022; Chesney & Tasto, 1975; Çelik, 2021; Jacobson, 1938; Proctor et al., 2007).

- Rhythmic abdominal massage as compared to non-treatment reduces dysmenorrhea symptoms (Suryantini, 2022; Vagedes et al., 2019):

- Biofeedback strategies such as frontalis electromyography feedback (EMG) and peripheral temperature training (Hart, Mathisen, & Prater, 1981); trapezius EMG training (Balick et al, 1982); lower abdominal EMG feedback training and relaxation (Bennink, Hulst, & Benthem, 1982); and integrated temperature feedback and autogenic training (Dietvorts & Osborne, 1978) all successfully reduced the symptoms of dysmenorrhea.

- Breathing relaxation for 5 to 30 minutes resulted in a decrease in pain or the pain totally disappeared in adolescents (Hidayatunnafiah et al., 2022). While slow deep breathing in combination with abdominal massage is more effective than applying hot compresses (Ariani et al., 2020). Slow pranayama (Nadi Shodhan) breathing the quality of life and pain scores improved as compared to fast pranayama (Kapalbhati) breathing and improved quality of life and reduces absenteeism and stress levels (Ganesh et al. 2015). When students are taught slow diaphragmatic breathing, many report a reduction in symptoms compared to the controls (Bier et al., 2005).

Observations from Integrated stress management program

This study reports on changes in dysmenorrhea symptoms by students enrolled in a University Holistic Health class that included homework assignment for practicing stress awareness, dynamic relaxation, and breathing with imagery.

Respondents: 32 college women, average age 24.0 years (S.D. 4.5 years)

Procedure: Students were enrolled in a three-unit class in which they were assigned daily home practices which changed each week as described in the book, Make Health Happen (Peper, Gibney & Holt, 2002). The first five weeks consisted of the following sequence: Week 1 focused on monitoring one’s reactions to stressor; week 2 consisted of daily practice for 30 minutes of a modified progressive relaxation and becoming aware of bracing and reducing the bracing during the day; Week 3 consisted of practicing slow diaphragmatic breathing for 30 minutes a day and during the day becoming aware of either breath holding or shallow chest breath and then use that awareness as cue to shift to lower slower diaphragmatic breathing; week 4 focused on evoking a memory of wholeness and relaxing; and week 5 focused on learning peripheral hand warming.

During the class, students observed lectures about stress and holistic health and met in small groups to discuss their self-regulation experiences. During the class discussion, some women discussed postures and practices that were beneficial when experiencing menstrual discomfort, such as breathing slowly while lying on their back, focusing on slow abdominal awareness in which their abdomen expanded during inhalation and contracted during exhalation. While exhaling they focused on imagining a flow of air initially going through their arms and then through their abdomen, down their legs and out their feet. This kinesthetic feeling was enhanced by first massaging down the arm while exhaling and then massaging down their abdomen and down their thighs when exhaling. In most cases, the women also experienced that their hands and feet warmed. In addition, they were asked to shift to slower diaphragmatic breathing whenever they observed themselves gasping, shallow breathing or holding their breath. After five weeks, the students filled out a short assessment questionnaire in which they rated the change in dysmenorrhea symptoms since the beginning of the class.

Results.

About two-thirds of all respondents reported a decrease in overall discomfort symptoms. In addition to any ‘treatment as usual’ (TAU) strategies already being used (e.g. medications or other treatments such as NSAIDs or birth control pills), 91% (20 out 22 women) who reported experiencing dysmenorrhea reported a decrease in symptoms when they practiced the self-regulation and diaphragmatic breathing techniques as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Self-report in dysmenorrhea symptoms after 5 weeks.

Discussion