Welcome the New Year with Inspiration

Posted: December 22, 2025 Filed under: attention, behavior, CBT, cognitive behavior therapy, emotions, healing, health, mindfulness, self-healing | Tags: hope, Inspreiation, meaning, post=traumatic growth, purpose, resilience 1 CommentAs the holiday season begins, I find myself looking back on all that has unfolded this year and looking forward with hope to the year ahead. My social media feed is full of touching, uplifting messages and videos—reminders of resilience, creativity, and the simple goodness in the world. Best wishes for the holidays and the New Year and I hope you will enjoy the two inspiring videos.

1. Nine life lessons from comedian Tim Minchin, presented at the University of Western Australia. His humor and wisdom offer a refreshing take on what truly matters.

2. A powerful story about transforming disaster into blessing.

If you ever feel stuck or unsure about the future, this video is a beautiful reminder that unexpected turns can lead to new possibilities.

Wishing you a healthy and inspiring New Year!

Erik

Reduce Interpersonal Stress*

Posted: December 4, 2025 Filed under: attention, behavior, Breathing/respiration, CBT, emotions, Exercise/movement, healing, health, meditation, mindfulness, Pain/discomfort, stress management | Tags: health, mental-health, nutrition, wellness 3 CommentsAdapted from: Peper, E. & Harvey, R. Adjunctive techniques to reduce interpersonal stress at home. Biofeedback. 53(3), 54-57. https://rdcu.be/eMJqt

Stress often triggers defensive reactions—manifesting as anger, frustration, or anxiety that may mirror fight-or-flight responses. These reactions can reduce rational thinking, increase long-term health risks, and contribute to psychological and physiological disorders. and complicate the management of specific symptoms. Outlined are some pragmatic techniques that can be implemented during the day to interrupt and reduce stress.

After we had been living in our house for a few years, a new neighbor moved in next door. Within months, she accused us of moving things in her yard, blamed us when there was a leak in her house, claimed we were blowing leaves from her property onto other neighbors’ properties, and even screamed at her tenants to the extent that the police were called numerous times. Just looking at her house through the window was enough to make my shoulders tighten and leave me feeling upset.

When I drove home and saw her standing in front of her house, I would drive around the block one more time to avoid her while . . . feeling my body contract. Often, when I woke up in the morning, I would already anticipate conflict with my neighbor. I would share stories of my disturbing neighbor and her antics with my friends. They were very supportive and agreed with me that she was crazy. However, the acknowledgment and validation from my friends did not resolve my anger or indignation or the anxiety that was triggered whenever I saw my neighbor or thought of her. I spent far too much time anticipating and thinking about her, which resulted in tension in my own body—my heart rate would increase, and my neck and shoulders would tighten.

I decided to change. I knew I could not change her; however, I could change my reactivity and perspective. Thus, I practiced a “pause and recenter” technique. At the first moment of awareness that I was thinking about her or her actions, I would change my posture by sitting up straight, begin looking upward, breathe lower and slower, and then, in my mind’s eye, send a thought of goodwill streaming to her like an ocean wave flowing through and around her in the distance. I chose to do this series of steps because I believe that within every person, no matter how crazy or cruel, there is a part that is good, and it is that part I want to support.

I repeated this pause and recenter technique many times, especially whenever I looked in the direction of her house or saw her in her yard. I also reframed and reappraised her aggressive, negative behavior as her way of coping with her own demons. Three months later, I no longer reacted defensively. When I see her, I can say hello and discuss the weather without triggering my defensive reaction. I feel so much more at peace living where I am.

When stressed, angry, rejected, frustrated, or hurt, we so often blame the other person (Leary, 2015). The moment we think about that person or event, our anger, indignation, resentment, and frustration are triggered. We keep rehashing what happened. As we relive the experiences in our mind, we are unaware that we are also reliving bodily reactions to past events.

We are often unaware of the harm we are doing to ourselves until we experience physical symptoms such as high blood pressure, gastrointestinal distress, and muscle tightness along with behavioral and psychological symptoms such as insomnia, anxiety, or depression (Carney et al., 2006; Gerin et al., 2012). As we think of past events or interact again with a person involved in those past events, our body automatically responds with a defense reaction as if we were being threatened again in the present moment.

This defense reaction to memory of past threats from a “crazy” neighbor activates our fight-or-flight responses and increases sympathetic activation so that we can run faster and fight more ferociously to survive; however, this reaction also reduces blood flow through the frontal cortex—a process that reduces our ability to think rationally (van Dinther et al., 2024; Willeumier, et al., 2011). When we become so upset and stressed that our mind is captured by the other person, this reaction contributes to symptoms of chronic stress such as an increase in hypertension, myofascial pain, depression, insomnia, cardiovascular disease, and other chronic disorders (Duan et al., 2022; Russell et al., 2015; Suls, 2013).

Sharing our frustrations with friends and others is normal. It feels good to blame people for their personal limitations or mental illness; however, over time, blaming others avoids building adaptive capacity in strengthening skills that reduce chronic stress reactions (Fast & Tiedens, 2010; Lou et al., 2023). The time spent rehashing and justifying our feelings diminishes the time we spend in the present moment and our focus on upcoming opportunities.

In the moment of an encounter with a difficult neighbor, we may not realize that we have a choice. Some people keep living and reacting to past hurts or losses perpetually. Some people can learn to let go and/or forgive and make space in favor of considering new opportunities for learning and growth. Although the choice is ours, it is often very challenging to implement—even with the best intentions—because we react automatically when reminded of past hurts (seeing that person, anticipating meeting or actually meeting that person who caused the hurt, or being triggered by other events that evoke memories of the pain).

What Can You Do

Choose to change your response. Choose to reduce reactivity. Choosing adaptive reactions does not mean you condone what happened or agree that the other person was right. You are just choosing to live your life and not continue to be captured by nor react to the previous triggers. Many people report that after implementing some of the practices described below along with many other stress management techniques, their automatic reactivity was noticeably decreased. They report that their chronic stress symptoms were reduced and they have the freedom to live in present instead of being captured by the painful past.

Pause and Recenter by Sending Goodwill

Our automatic reaction to the trigger elicits a defense reaction that reduces our ability to think rationally. Therefore, the moment you anticipate or begin to react, take three very slow diaphragmatic breaths, inhaling for approximately 4–5 seconds and exhaling for about 5–6 seconds, where one in-and-out breath takes about 10 seconds to complete. As you inhale, allow your abdomen to expand; then as you exhale, slowly make yourself tall and look up. Looking up allows easier access to empowering and positive memories (Peper et al., 2017).

Continue looking up, inhaling slowly to allow the abdomen to expand. Repeat this slow breath again. On the third long, slow breath, while looking up, evoke a memory of someone in whose presence you felt at peace and who loves you, such as your grandmother, aunt, uncle, or even a pet. Reawaken positive feelings associated with memories of being loved. Allow a smile inwardly or outwardly and soften your eyes as you experience the loving memory.

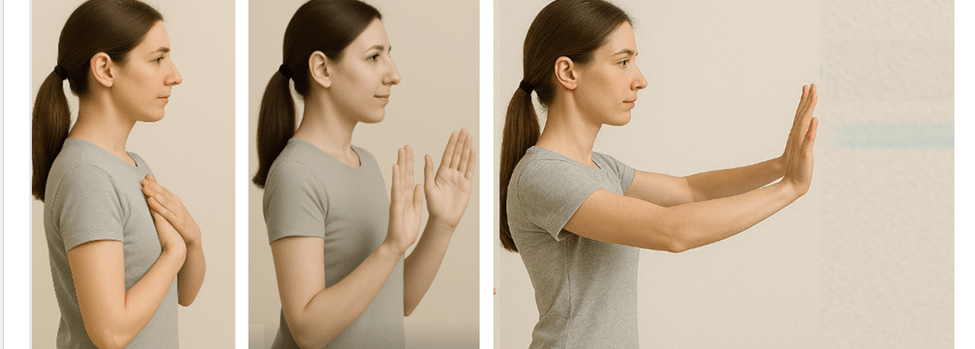

Next, put your hands on your chest, take another long slow breath as your abdomen expands, and as you exhale bring your hands away from your chest and stretch them out in front of you. At the same time in your mind’s eye, imagine sending goodwill to that person involved in the interpersonal conflict that previously evoked your stress response. As if you are sending an ocean wave that is streaming outward to the person.

As you do the pause and recenter technique, remember you are not condoning what happened; instead, you are sending goodwill to that person’s positive aspect. From this perspective, everyone has an intrinsic component—however small—that some label as the individual’s human potential, Christ nature or Buddha nature.

Why would this be effective? This practice short-circuits the automatic stress response and provides time to recenter, interrupting ongoing rumination by shifting the mind away from thoughts about the person or event that induced stress toward a positive memory. By evoking a loving memory from the past, we facilitate a reduction in arousal, evoke a positive mood, and decrease sympathetic nervous system activation (Speer & Delgado, 2017). Slower diaphragmatic breathing also reduces sympathetic activation (Birdee et al., 2023; Siedlecki et al., 2022). By combining body-centered and mind-centered techniques, we can pause and create the opportunity to respond positively rather than reacting with anger and hurt.

Practice Sending Goodwill the Moment You Wake Up

So often when we wake up, we anticipate the challenges, and even the prospect of interacting with a person or event heightens our defense reaction. Therefore, as soon as you wake up, sit at the edge of the bed, repeat the previous practice, pause, and center. Then, as you sit at the edge of the bed, slightly smile with soft eyes, look up, and inhale as your abdomen expands. Then, stamp a foot into the floor while saying, “Today is a new day.” Next, inhale, allowing your abdomen to expand; as you look up, stamp the opposite foot on the floor while saying, “Today is a new day.” Finally, send goodwill to the person who previously triggered your defensive reaction.

Why would this be effective? Looking up makes it easier to access positive memories and thoughts. Stamping your foot on the ground is a nonverbal expression of determination and anchors the thought of a new day, thereby focusing on new opportunities (Feldman, 2022).

Interrupt the Stress Response with the ABCs

The moment you notice discomfort, pain, stress, or negative thoughts, interrupt the cycle with a simple ABC strategy (Peper, 2025):

- Adjust posture and look up

- Breathe by allowing your abdomen to relax and expand while inhaling

- Change your internal dialogue, smile and focus on what you want to do

Why would this be effective? By shifting your posture and gently looking upward, you make it easier to access positive and empowering memories and thoughts (Peper et al., 2019). This simple change in body position can interrupt habitual stress responses and open the doorway to more constructive states.

Slow, diaphragmatic breathing further supports this process by reducing sympathetic arousal and restoring a sense of calm. As your breathing deepens, clarity of mind increases, allowing you to respond rather than react (Peper et al, 2024b; Matto et al, 2025).

Equally important is transforming critical, judgmental, or negative self-talk into affirmative, supportive statements. Describe what you want to do—rather than what you want to avoid. This reframing creates a clear internal guide and significantly increases the likelihood that you will achieve your desired goals.

Complete the Alarm Reaction a Burst of Physical Activity

When you feel overwhelmed and fully captured by a stress reaction, one of the most effective strategies is to complete the fight-flight response with a brief burst of intense physical activity. This momentary action such as running in place, vigorously shaking your arms, or doing a few rapid push-offs from a wall (Peper et al., 2024a). After completing the physical activity implement your stress management strategies such as breathing, cognitive reframing, meditation, etc.

Why would this be effective? The intense physical activity discharges the excessive physiological arousal and interrupts the cycle of rumination. For practical examples and step-by-step guidance, see the article Quick Rescue Techniques When Stressed (Peper et al., 2024a) or the accompanying blog post: https://peperperspective.com/2024/02/04/quick-rescue-techniques-when-stressed/

Discuss Your Issue from the Third-Person Perspective

When thinking, ruminating, talking, texting, or writing about the event, discuss it from the third-person perspective. Replace the first-person pronoun “I” with “she” or “he.” For example, instead of saying “I was really pissed off when my boss criticized my work without giving any positive suggestions for improvement,” say “He was really pissed off when his boss criticized his work without offering any positive suggestions for improvement.”

Why would this be effective? The act of substituting the third-person pronoun for the first-person pronoun interrupts our automatic reactivity because it requires us to observe and change our language, which activates parts of the frontal cortex. This third-person/first-person process creates a psychological distance from our feelings, allowing for a more objective and calmer perspective on the situation, effectively reducing stress by stepping back from the immediate emotional response (Moser et al., 2017). This process can be interpreted as meaning that you are no longer fully captured by the emotions, as you are simultaneously the observer of your own inner language and speech.

Compare Yourself with Others Who are less Fortunate

When you feel sorry for yourself or hurt, take a breath, look upward, and compare yourself with others who are suffering much more. In that moment, consider yourself incredibly lucky compared with people enduring extreme poverty, bombings, or severe disfigurement. Be grateful for what you have.

Why would this be effective? Research shows that when we compare ourselves with people who are more successful, we tend to feel worse—especially when we have low self-esteem. However, when we compare ourselves with others who are suffering more, we tend to feel better (Aspinwall, & Taylor, 1993). This comparison relativizes our perspective on suffering, making our own hardships and suffering seem less significant compared with the severe suffering of others.

Conclusion

It is much easier to write and talk about these practices than to implement them. Reminding yourself to implement them can be very challenging. It requires significant effort and commitment. In some cases, the benefits are not experienced immediately; however, when practiced many times during the day for six to eight weeks, many people report feeling less resentment and experience a reduction in symptoms and improvements in health and relationships.

*This blog was inspired by the podcast “No Hard Feelings,” an episode on Hidden Brain produced by Shankar Vedantam (2025) that featured psychologist Fred Luskin, and the wisdom taught by Dora Kunz (Kunz & Peper, 1983, 1984a, 1984b, 1987).

See the following posts for more relevant information

References

Aspinwall, L. G., & Taylor, S. E. (1993). Effects of social comparison direction, threat, and self-esteem on affect, self-evaluation, and expected success. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(5), 708–722. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.64.5.708

Birdee, G., Nelson, K.,Wallston, K., Nian, H., Diedrich, A., Paranjape, S., Abraham, R., & Gamboa, A. (2023). Slow breathing for reducing stress: The effect of extending exhale. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2023.102937

Carney, C. E., Edinger, J. D., Meyer, B., Lindman, L., & Istre, T. (2006). Symptom-focused rumination and sleep disturbance. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 4(4), 228–241. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15402010bsm0404_3

Defayette, A. B., Esposito-Smythers, C., Cero, I., Harris, K. M.,Whitmyre, E. D., & López, R. (2023). Interpersonal stress and proinflammatory activity in emerging adults with a history of suicide risk: A pilot study. Journal of Mood and Anxiety Disorders, 2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xjmad.2023.100016

Dienstbier, R. A. (1989). Arousal and physiological toughness: Implications for mental and physical health. Psychological Review, 96(1), 84. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-95x.96.1.84

Duan, S., Lawrence, A., Valmaggia, L., Moll, J., & Zahn, R. (2022). Maladaptive blame-related action tendencies are associated with vulnerability to major depressive disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 145, 70–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.11.043

Fast, N. J., & Tiedens, L. Z. (2010). Blame contagion: The automatic transmission of self-serving attributions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46(1), 97–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.10.007

Feldman, Y. (2022). The dialogical dance–A relational embodied approach to supervision. In C. Butte & T. Colbert (Eds.), Embodied approaches to supervision: The listening body (chap. 2). Routledge. https://www.amazon.com/Embodied-Approaches-Supervision-C%C3%A9line-Butt%C3%A9/dp/0367473348

Gerin,W., Zawadzki,M. J., Brosschot, J. F., Thayer, J. F., Christenfeld, N. J., Campbell, T. S., & Smyth, J. M. (2012). Rumination as a mediator of chronic stress effects on hypertension: A causal model. International Journal of Hypertension, 2012, 453465. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/453465

Hase, A., O’Brien, J., Moore, L. J., & Freeman, P. (2019). The relationship between challenge and threat states and performance: A systematic review. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 8(2), 123. https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000132

Hassamal, S. (2023). Chronic stress, neuroinflammation, and depression: An overview of pathophysiological mechanisms and emerging anti-inflammatories. Frontiers in Psychiatry,

14, 1130989. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1130989

Kunz, D., & Peper, E. (1983). Fields and their clinical implications—Part III: Anger and how it affects human interactions. The American Theosophist, 71(6), 199–203. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280777019_Fields_and_their_clinical_implications-Part_III_Anger_and_how_it_affects_human_interactions

Kunz, D., & Peper, E. (1984a). Fields and their clinical implications IV: Depression from the energetic perspective: Etiological underpinnings. The American Theosophist, 72(8), 268–275. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280884054_Fields_and_their_clinical_implications_Part_IV_Depression_from_the_energetic_perspective-Etiological_underpinnings

Kunz, D., & Peper, E. (1984b). Fields and their clinical implications V: Depression from the energetic perspective: Treatment strategies. The American Theosophist, 72(9), 299–306. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280884158_Fields_and_their_clinical_implications_Part_V_Depression_from_the_energetic_perspective-Treatment_strategies

Kunz, D., & Peper, E. (1987). Resentment: A poisonous undercurrent. The Theosophical Research Journal, IV(3), 54–59. Also in: Cooperative Connection, IX(1), 1–5. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/387030905_Resentment_Continued_from_page_4

Leary, M. R. (2015). Emotional responses to interpersonal rejection. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 17(4), 435–441. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2015.17.4/mleary

Lou, Y., Wang, T., Li, H., Hu, T. Y., & Xie, X. (2023). Blame others but hurt yourself: Blaming or sympathetic attitudes toward victims of COVID-19 and how it alters one’s health status. Psychology & Health, 39(13), 1877–1898. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2023.2269400

Matto, D., Peper, E., & Harvey, R. (2025). Monitoring and coaching breathing patterns and rate. Townsend Letter-Innovative Health Perspectives. https://townsendletter.com/monitoring-and-coaching-breathing-patterns-and-rate/

Moser, J. S., Dougherty, A., Mattson, W. I., Katz, B., Moran, T. P.,Guevarra, D., Shablack, H.,Ayduk,O., Jonides, J., Berman, M. G., & Kross, E. (2017). Third-person self-talk facilitates emotion regulation without engaging cognitive control: Converging evidence from ERP and fMRI. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 4519. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-04047-3

Peper, E. (2025). Breathe Away Menstrual Pain- A Simple Practice That Brings Relief. the peper perspective-ideas on illness, health and well-being from Erik Peper. https://peperperspective.com/2025/11/22/6825/

Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Hamiel, D. (2019). Transforming thoughts with postural awareness to increase therapeutic and teaching efficacy. NeuroRegulation, 6(3), 153-169. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.6.3.1533-1

Peper, E., Lin, I.-M., Harvey, R., & Perez, J. (2017). How posture affects memory recall and mood. Biofeedback, 45(2), 36–41. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-45.2.01

Peper, E., Oded, Y., & Harvey, R. (2024a). Quick somatic rescue techniques when stressed. Biofeedback, 52(1), 18–26. https://doi.org/10.5298/982312

Peper, E., Oded, Y., Harvey, R., Hughes, P., Ingram, H., & Martinez, E. (2024b). Breathing for health: Mastering and generalizing breathing skills. Townsend Letter-Innovative Health Perspectives. November 15, 2024. https://townsendletter.com/suggestions-for-mastering-and-generalizing-breathing-skills/

Russell, M. A., Smith, T. W., & Smyth, J. M. (2015). Anger expression, momentary anger, and symptom severity in patients with chronic disease. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 50(2), 259–271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-015-9747-7

Siedlecki, P., Ivanova, T. D., Shoemaker, J. K., & Garland, S. J. (2022). The effects of slow breathing on postural muscles during standing perturbations in young adults. Experimental Brain Research, 240, 2623–2631. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-022-06437-0

Speer, M. E., & Delgado, M. R. (2017). Reminiscing about positive memories buffers acute stress responses. Nature Human Behaviour, 1, 0093. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-017-0093

Suls, J. (2013). Anger and the heart: Perspectives on cardiac risk, mechanisms and interventions. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases, 55(6), 538–547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2013.03.002

van Dinther, M., Hooghiemstra, A. M., Bron, E. E., Versteeg, A., et al. (2024). Lower cerebral blood flow predicts cognitive decline in patients with vascular cognitive impairment. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, 20(1), 136–144. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.13408

Vedantam, S. (2025). No hard feelings. Hidden brain. Accessed February 5, 2025. https://hiddenbrain.org/podcast/no-hard-feelings/

Willeumier, K., Taylor, D. V., & Amen, D. G. (2011). Decreased cerebral blood flow in the limbic and prefrontal cortex using SPECT imaging in a cohort of completed suicides. Translational Psychiatry, 1(8), e28. https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2011.28

Zannas, A. S., & West, A. E. (2014). Epigenetics and the regulation of stress vulnerability and resilience. Neuroscience, 264, 157–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.12.003