Playful practices to enhance health with biofeedback

Posted: May 4, 2024 Filed under: attention, behavior, biofeedback, Breathing/respiration, computer, Exercise/movement, health, Neck and shoulder discomfort, Pain/discomfort, self-healing, Uncategorized | Tags: exercise, Feldenkrais, pain, Play, somatics 1 CommentAdapted from: Gibney, K.H. & Peper, E. (2003). Exercise or play? Medicine of fun. Biofeedback, 31(2), 14-17.

Homework assignments are sometimes viewed as chore and one more thing to do. Changing the perception from that of work to fun by encouraging laughter and joy often supports the healing process. This blog focusses on utilizing childhood activities and paradoxical movement to help clients release tension patterns and improve range of motion. A strong emphasis is placed on linking diaphragmatic breathing to movement.

When I went home I showed my granddaughter how to be a tree swaying in the wind, she looked at me and said, “Grandma, I learned that in kindergarten!”

‘Betty’ laughed heartily as she relayed this story. Her delight in being able to sway her arms like the limbs of a tree starkly contrasted with her demeanor only a month prior. Betty was referred for biofeedback training after a series of 9 surgeries – wrists, fingers, elbows and shoulders. She arrived at her first session in tears with acute, chronic pain accompanied by frequent, incapacitating spasms in her shoulders and arms. She was unable to abduct her arms more than a few inches without triggering more painful spasms. Her protective bracing and rapid thoracic breathing probably exacerbated her pain and contributed to a limited range of motion of her arms. Unable to work for over a year, she was coping not only with pain, but also with weight gain, poor self-esteem and depression.

The biofeedback training began with effortless, diaphragmatic breathing which is often the foundation of health (Peper and Gibney, 1994). Each thoracic breath added to Betty’s chronic shoulder pain. Convincing Betty to drop her painful bracing pattern and to allow her arms to hang freely from her shoulders as she breathed diaphragmatically was the first major step in regaining mobility. She discovered in that first session that she could use her breathing to achieve control over muscle spasms when she initiated the movement during the exhalation phase of breathing as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Initiate the physical activity after exhaling has begun and body is relaxing especially if the movement or procedure such as an injection would cause pain. Pause the movement when inhaling and then continue the movement again during the exhalation phase. The simple rule is to initiate the activity slightly after beginning exhaling and when the heart rate started to decrease (reproduced with permission from Gorter & Peper, 2012).

During the first week, she practiced her breathing assiduously at home and had fewer spasms. Betty was able to move better during her physical therapy sessions. Each time she felt the onset of muscle spasms she would stop all activity for a moment and ‘go into my trance’ to prevent a recurrence. For the first time in many months, she was feeling optimistic.

Subsequent sessions built upon the foundation of diaphragmatic breathing: boosting Betty’s confidence, increasing range of motion (ROM), and bringing back some fun in life. Activities included many childhood games: tossing a ball, swaying like a tree in the wind, pretending to conduct an orchestra, bouncing on gym balls, playing “Simon Says” (following the movements of the therapist), and dancing. Laughter and childlike joy became a common occurrence. She looked forward to receiving the sparkly star stickers she was given after successful sessions. With each activity, Betty gained more confidence, gradually increased ROM, and began losing weight. Although she had some days where the pain was strong and spasms threatened, Betty reframed the pain as occurring as a result of healing and expanding her ROM—she was no longer a victim of the pain. In addition, her family was proud of her, she was doing more fun activities, and she felt confident that she would return to work.

Betty’s story is similar to other clients whom we have seen. The challenge presented to therapists is to help the client better cope with pain, increase ROM, regain function and, often the most important, to reclaim a “joie de vivre”. Increasing function includes using the minimum amount of effort necessary for the task, allowing unnecessary muscles to remain relaxed (inhibition of dysponesis[i]), and quickly releasing muscle tension when the muscle is no longer required for the activity (work/rest) (Whatmore & Kohli, 1974; Peper et al, 2010; Sella, 2019). The challenge is to perform the task without concurrent evocation of components of the alarm reaction, which tend to be evoked when “we try to do it perfectly,” or “it has to work,” “If I do not do it correctly,” or “I will be judged.” For example, when people learn how to implement micro-breaks (1–2 second rest periods) at the computer, they often sit quietly believing that they are relaxed; however, they may continue a bracing pattern (Peper et al, 2006). Alternatively, tossing a small ball rather than resting at the keyboard will generally evoke laughter, encourage generalization of skills, and covertly induce more relaxation. In some cases, therapists in their desire to help clientss to get well assign structured exercises as homework that evoke striving for performance and boredom—this striving to perform the structured exercises may inhibit healing. Utilizing tools other than those found in the work setting helps the client achieve a broader perspective of the healing/preventive concepts that are taught.

To optimize success, clients are active participants in their own healing process which means that they learn the skills during the therapeutic session and practice at home and at work. Home practices are assigned to integrate the mastery of news skills into daily life. To help clients achieve increased health through physical activity three different approaches are often used: movement reeducation, youthful play, and pure exercise. How the client performs the activity may be monitored with surface electromyography (SEMG) to identify muscles tightening that are not needed for the task and how the muscle relaxes when not needed for the task performance. This monitoring can be done with a portable biofeedback device or multi-channel system when walking or performing the exercises. Clients can even use a single channel SEMG at home.

When working to improve ROM and physical function, explore the following:

- Maintain diaphragmatic breathing – rhythm or tempo may change but the breath must be generated from the diaphragm with emphasis on full exhalation. Use strain gauge feedback and/or SEMG feedback to monitor and train effortless breathing (Peper et al., 2016). Strain gauge feedback is used to teach a slower and diaphragmatic breathing pattern, while SEMG recorded from the scalene to trapezius is used to teach how to reduce shoulder and ancillary muscle tension during inhalation

- Perform activities or stretching/strengthening exercises so slowly that they don’t trigger or aggravate pain during the exhalation phase of breathing.

- Use the minimum amount of tension necessary for the task and let unnecessary muscles remain relaxed. Use SEMG feedback recorded from muscles not needed for the performance of the task to teach clients awareness of inappropriate muscle tension and to learn relaxation of those muscles.

- Release muscle tension immediately when the task is accomplished. Use SEMG feedback to monitor that the muscles are completely relaxed. If rapid relaxation is not achieved, first teach the person to relax the muscles before repeating the muscle activity.

- Perform the exercises as if you have never performed them and do them with a childlike, beginner’s mind, and exploratory attitude (Kabat-Zinn, 1990).

- Create exercises that are totally new and novel so that the participant has no expectancy of outcome can be surprised by their own experience. This approach is part of many somatic educational and therapeutic approaches such as Feldenkrais or Somatics (Hanna, 2004; Feldenkrais, 2009).

Movement and exercise can be taught as pure physical exercise, movement reeducation or youthful playing. Physical exercise is necessary for strength and endurance and at the same time, improves our mood (Thayer, 1996; Mahindru et al., 2023). However, many exercises are considered a burden and are often taught without a sense of lightness and fun, which results in the client thinking in terms that are powerless and helpless (depressive)—“I have to do them.” Helping your clients to understand that exercise is simply a part of every day life, that it encourages healing and improves health, and that they can “cheat” at it, may help them to reframe their attitudes toward it and accomplish their healing goals.

Pure Physical Exercise—Enjoyment through Strength and Flexibility

The major challenge of structured exercises is that the person is very serious and strives too hard to attain the goal. In the process of striving, the body is often held rigid: Breath is shallow and halted and shoulders are slightly braced. Maintaining a daily chart is an excellent tool to show improvement (e.g., more repetitions, more weight, increased flexibility; since, structured exercises are very helpful for improving ROM and strength. When using pure exercise, remember that injured person may have a sense of urgency – they want to get well quickly and, if work stress was a factor in developing pain, they often rush when they need to meet a deadline.

As much as possible make the exercise fun. Help the client understand that he/she can be quick while not rushed. For example, monitor SEMG from an upper trapezius muscle using a portable electromyography. For example, begin by walking slowly. Add a ramp or step to ensure that there is no bracing when climbing (a common occurrence). Walk around the room, down the hall, around the block. Maintain relaxed shoulders, an even swing of the arms, and diaphragmatic breathing. Walk more quickly while emphasizing relaxation with speed rather than rushing. Go faster and faster. Up the stairs. Down the stairs. Walk backward. Skip. Hop. Laugh.

Movement Reeducation – Be ‘Oppositional’ And Do It Differently

Movement reeducation, such as Feldenkrais, Alexander Technique or Hannah Somatics, involves conscious awareness of movement (Alexander, 2001; Hanna, 2004; Murphy, 1993). Many daily patterns of movement become imbedded in our consciousness and, over the years, may include a pain trigger. A common trigger is lifting the shoulders when reaching for the keyboard or mouse, people suffering from thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) often have such patterns (Peper & Harvey, 2021). A keyboard can often inadvertently cue the client to trigger this dysponetic, and frequently painful, pattern. Have the client do movement reeducation exercises as they are guided through practices in which they have no expectancy and the movements are novel. The focus is on awareness without triggering any fight/flight or startle responses.

Ask the client to explore performing many functional activities with the opposite hand, such as brushing his/her hair or teeth, eating, blowing his/her hair dry, or doing household chores, such as vacuuming. (Explore this for yourself, as well!). Be aware of how much shoulder muscle tension is needed to raise the arms for combing or blow-drying the hair. Explore how little effort is required to hold a fork or knife (you might want to do this in the privacy of your own home!).

Do movements differently such as, practicing alternating hands when leading with the vacuum or when sweeping, changing routes when driving/walking to work or the store, getting out of bed differently. Break up habitual conditioned reflex patterns such as eye, head and hand coordination. For example, slowly rotate your head from left to right and simultaneously shift your eyes in the opposite direction (e.g., turn your head fully to the right while shifting your eyes fully to the left, and then reverse) or before reaching forward, drop your elbows to your sides then, bend your elbows and touch your shoulders with your thumbs then, reach forward. Often, when we change our patterns we increase our flexibility, inhibit bracing and reduce discomfort.

Free Your Neck and Shoulders (adapted from a demonstration by Sharon Keane and developed by Ilana Rubenfeld, 2001)

–Push away from the keyboard and sit at the edge of the chair with your knees bent at right angles and your feet shoulder-width apart and flat on the floor. Do the following movements slowly. Do NOT push yourself if you feel discomfort. Be gentle with yourself.

–Look to the right and gently turn your head and body as far as you can go to the right. When you have gone as far as you can comfortably go, look at the furthest spot on the wall and remember that spot. Gently rotate your head back to center. Close your eyes and relax.

–Reach up with your left hand; pass it over the top of your head and hold on to your right ear. Then, gently bend to the left lowering your elbow towards the floor. Slowly straighten up. Repeat for a few times feeling as if you are a sapling flexing in the breeze. Observe what your body is doing as it bends and comes back up to center. Notice the movements in your ribs, back and neck. Then, drop your arm to your lap and relax. Make sure you continue to breathe diaphragmatically throughout the exercise.

–Reach up with your right hand and pass it over the top of your head and hold on to your left ear. Repeat as above except bending to the right.

–Reach up with your left hand and pass it over the top of your head and hold on to your right ear. Then, look to the left with your eyes and rotate your head to the left as if you are looking behind you. Return to center and repeat the movement a few times. Then, drop your arm to your lap and relax for a few breaths.

–Again, reach over your head with your left hand and hold onto your right ear. Repeat the same rotating motion of your head to the left except that your eyes look to the right. Repeat this a few times then, drop your arm to your lap and relax for a few breaths.

–Reach up with your right hand and pass it over the top of your head and hold on to your left ear. Then, look to the right with your eyes and rotate your head to the right as if you are looking behind you. Return to center and repeat a few times. Then, drop your arm to your lap and relax for a few breaths.

–Again, reach over your head with your right hand and hold onto your left ear. Repeat the same rotating motion of your head to the right except that your eyes look to the left. Repeat this a few times then, drop your arm to your lap and relax for a few breaths.

–Now, look to the right and gently turn your head and body as far as you can go. When you can not go any further, look at that point on the wall. Did you rotate further than at the beginning of the exercise?

–Gently rotate your head back to center, close your eyes, relax and notice the feeling in your neck, shoulders and back.

Youthful Playing – Pavlovian Practice

Evoking positive past memories and actually acting them out may enhance health as is illustrated by the recovery of serious illness of Ivan Pavlov, the discovery of classical conditioning. When Pavlov quietly lay in his hospital bed, many, including his family, thought he was slipping into death. He then ask the nurse to get him a bowl of water with earth in it and the whole night long he gently played with the mud. He recreated the experience when as a child he was playing in mud along a river’s bank. Pavlov knew that evoking the playful joy of childhood would help to encourage mental and physical healing. The mud in hands was the conditioned stimulus to evoke the somatic experience of wellness (Peper, Gibney, & Holt, 2002).

Having clients play can encourage laughter and joie de vivre, which may help in physical healing. Being involved in childhood games and actually playing these games with children removes one from worries and concerns—both past and future—and allows one to be simply in the present. Just being present is associated with playfulness, timelessness, passive attention, creativity and humor. A state in which one’s preconceived mental images and expectancies—the personal, familial, cultural, and healthcare provider’s hypnotic suggestions—are by-passed and for that moment, the present and the future are yet undefined. This is often the opposite of the client’s expectancy; since, remembering the past experiences and the diagnosis creates a fixed mental image that may expect pain and limitation.

Explore some of the following practices as strategies to increase movement and flexibility without effort and to increase joy. Use your creativity and explore your own permutations of the practices. Observe how your mood improves and your energy increases when you play a childhood game instead of an equivalent exercise. For example, instead of dropping your hands to your lap or stretching at the computer terminal during a micro- or meso-break[ii], go over to your coworker and play “pattycake.” This is the game in which you and your partner face each other and then clap your hands and then touch each other’s palms. Do this in all variations of the game.

For increased ROM in the shoulders explore some of the following (remember the basics: diaphragmatic breathing, minimum effort, rapid release) in addition, do the practices to the rhythm of the music that you enjoyed as a young person.

Ball Toss: a hand-sized ball that is easily squeezed is best for this exercise. Monitor respiration patterns, and SEMG forearm extensors and/or flexors, and upper trapezii muscles. Sit quietly in a chair and focus on a relaxed breathing rhythm. Toss the ball in the air with your right hand and catch it with your left hand. As soon as you catch the ball, drop both hands to your lap. Toss the ball back only when you achieve relaxation—both with the empty hand and the hand holding the ball. Watch for over-efforting in the upper trapezii. Begin slowly and increase the pace as you train yourself to quickly release unnecessary muscle tension. Go faster and faster (just about everyone begins to laugh, especially each time they drop the ball).

Ball Squeeze/Toss: Expand upon the above by squeezing the ball prior to tossing. When working with a client, call out different degrees of pressure (e.g., 50%, 10%, 80%, etc.). The same rules apply as with the ball toss.

Ball Hand to Hand: Close your eyes and hand the ball back and forth. Go faster and faster and add ball squeezes prior to passing the ball.

Gym Ball Bounces: Sit on a gym ball and find your balance. Begin bouncing slowly up and down. Reach up and lower your left then, right hand. Abduct your arms forward then, laterally. Turn on the radio and bounce to music.

Simon Says: This can be done standing, sitting in a chair or on a gym ball. When on a gym ball, bounce during the game. Have your client do a mirror image of your movements: reaching up, down, left, right, forward or backward. Touch your head, nose, knees or belly. Have fun and go more quickly.

Back-To-Back Massage: With a partner, stand back-to-back. Lean against each other’s back so that you provide mutual support. Then each rub your back against each other’s back. Enjoy the wiggling movement and stimulation. Be sure to continue to breathe.

Summary: An Attitude of Fun

In summary, it is not what you do; it is also the attitude by which you do it that affects health. From this perspective,when exercises are performed playfully, flexibility, movement and health are enhanced while discomfort is decreased. Inducing laughter promotes healing and disrupts the automatic negative hypnotic suggestion/self-images of what is expected. The clients begins to live in the present moment and thereby decreases the anticipatory bracing and dysponetic activity triggered by striving. By decreasing striving and concern for results, clients may allow themselves to perform the practices with a passive attentive attitude that may facilitate healing. For that moment, the client forgets the painful past and a future expectances that are fraught with promises of continued pain and inactivity. At moment, the pain cycle is interrupted which provides hope for a healthier future.

References

Alexander, F.M. (2001). The Use of the Self. London: Orion Publishing. https://www.amazon.com/Use-Self-F-M-Alexander/dp/0752843915

Feldenkrais, M. (2009). Awareness Through Movement Easy-to-Do Health Exercises to Improve Your Posture, Vision, Imagination, and Personal Awareness. New York: HarperOne. https://www.amazon.com/Awareness-Through-Movement-Easy-Do/dp/0062503227

Gibney, K.H. & Peper, E. (2003). Exercise or play? Medicine of fun. Biofeedback, 31(2), 14-17. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/380317304_EXERCISE_OR_PLAY_MEDICINE_OF_FUN

Gorter, R. & Peper, E. (2012). Fighting Cancer- A Nontoxic Approach to Treatment. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books. https://www.amazon.com/Fighting-Cancer-Nontoxic-Approach-Treatment/dp/1583942483

Hanna, T. (2004). Somatics: Reawakening The Mind’s Control Of Movement, Flexibility, And Health. Da Capo Press. https://www.amazon.com/Somatics-Reawakening-Control-Movement-Flexibility/dp/0738209570

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living. New York: Delacorte Press.

Mahindru, A., Patil, P., & Agrawal, V. (2023). Role of Physical Activity on Mental Health and Well-Being: A Review. Cureus, I5(1), e33475. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.33475

Murphy, M. (1993). The future of the body. New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Perigee. https://www.amazon.com/Future-Body-Explorations-Further-Evolution/dp/0874777305

Peper, E., Booiman, A., Lin, I-M, Harvey, R., & Mitose, J. (2016). Abdominal SEMG Feedback for Diaphragmatic Breathing: A Methodological Note. Biofeedback. 44(1), 42-49. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/300365890_Abdominal_SEMG_Feedback_for_Diaphragmatic_Breathing_A_Methodological_Note

Peper, E., Booiman, A., Tallard, M., & Takebayashi, N. (2010). Surface electromyographic biofeedback to optimize performance in daily life: Improving physical fitness and health at the worksite. Japanese Journal of Biofeedback Research, 37(1), 19-28. https://doi.org/10.20595/jjbf.37.1_19

Peper, E., Gibney, K. & Holt, C. (2002). Make health happen: Training yourself to create wellness. Dubuque, IA: Kendall-Hunt. https://he.kendallhunt.com/product/make-health-happen-training-yourself-create-wellness

Peper, E. & Harvey, R. (2021). Causes of TechStress and ‘Technology-Associated Overuse’ Syndrome and Solutions for Reducing Screen Fatigue, Neck and Shoulder Pain, and Screen Addiction. Townsend Letter-The examiner of Alternative Medicine, Oct 28, 2021. https://www.townsendletter.com/article/459-techstress-how-technology-is-hurting-us

Peper, E., Harvey, R. & Tylova, H. (2006). Stress protocol for assessing computer related disorders. Biofeedback. 34(2), 57-62. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242549995_FEATURE_Stress_Protocol_for_Assessing_Computer-Related_Disorders

Peper, E. & Tibbetts, V. (1994). Effortless diaphragmatic breathing. Physical Therapy Products. 6(2), 67-71. Also in: Electromyography: Applications in Physical Therapy. Montreal: Thought Technology Ltd. https://www.bfe.org/protocol/pro10eng.htm

Rubenfeld, I. (2001). The listening hands: Self-healing through Rubenfeld Synergy method of talk and touch. New York: Random House. https://www.amazon.com/Listening-Hand-Self-Healing-Through-Rubenfeld/dp/0553379836

Sella, G. E. (2019). Surface EMG (SEMG): A Synopsis. Biofeedback, 47(2), 36–43. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-47.1.05

Thayer, R.E. (1996). The origin of everyday moods—Managing energy, tension, and stress. New York: Oxford University Press. https://www.amazon.com/Origin-Everyday-Moods-Managing-Tension/dp/0195118057

Whatmore, G. and Kohli, D. The Physiopathology and Treatment of Functional Disorders. New York: Grune and Stratton, 1974. https://www.amazon.com/physiopathology-treatment-functional-disorders-biofeedback/dp/0808908510

[i] Dysponesis involves misplaced muscle activities or efforts that are usually covert and do not add functionally to the movement. From: Dys” meaning bad, faulty or wrong, and “ponos” meaning effort, work or energy (Whatmore and Kohli, 1974)

[ii] A meso-break is a 10 to 90 second break that consists of a change in work position, movement or a structured activity such as stretching that automatically relaxes those muscles that were previously activated while performing a task.

Freedom of movement with the Alexander Technique

Posted: April 26, 2022 Filed under: behavior, computer, digital devices, education, emotions, ergonomics, Exercise/movement, healing, health, Pain/discomfort, posture, screen fatigue, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: Alexander Technique, back pain, neck and shoulder pain, somatics 3 CommentsErik Peper and Elyse Shafarman

After taking Alexander Technique lessons I felt lighter and stood taller and I have learned how to direct myself differently. I am much more aware of my body, so that while I am working at the computer, I notice when I am slouching and contracting. Even better, I know what to do so that I have no pain at the end of the day. It’s as though I’ve learned to allow my body to move freely.

The Alexander Technique is one of the somatic techniques that optimize health and performance (Murphy, 1993). Many people report that after taking Alexander lessons, many organic and functional disorders disappear. Others report that their music or dance performances improve. The Alexander Technique has been shown to improve back pain, neck pain, knee pain walking gait, and balance (Alexander technique, 2022; Hamel, et al, 2016; MacPherson et al., 2015; Preece, et al., 2016). Benefits are not just physical. Studying the technique decreases performance anxiety in musicians and reduces depression associated with Parkinson’s disease (Klein, et al, 2014; Stallibrass et al., 2002).

Background

The Alexander Technique was developed in the late 19th century by the Australian actor, Frederick Matthias Alexander (Alexander, 2001). It is an educational method that teaches students to align, relax and free themselves from limiting tension habits (Alexander, 2001; Alexander technique, 2022). F.M Alexander developed this technique to resolve his own problem of becoming hoarse and losing his voice when speaking on stage.

Initially he went to doctors for treatment but nothing worked except rest. After resting, his voice was great again; however, it quickly became hoarse when speaking. He recognized that it must be how he was using himself while speaking that caused the hoarseness. He understood that “use” was not just a physical pattern, but a mental and emotional way of being. “Use” included beliefs, expectations and feelings. After working on himself, he developed the educational process known as the Alexander Technique that helps people improve the way they move, breathe and react to the situations of life.

The benefits of this approach has been documented in a large randomized controlled trial of one-on-one Alexander Technique lessons which showed that it significantly reduced chronic low back pain and the benefits persisted a year after treatment (Little, et al, 2008). Back pain as well as shoulder and neck pain often is often related to stress and how we misuse ourselves. When experiencing discomfort, we quickly tend to blame our physical structure and assume that the back pain is due to identifiable structural pathology identified by X-ray or MRI assessments. However, similar structural pathologies are often present in people who do not experience pain and the MRI findings correlate poorly with the experience of discomfort (Deyo & Weinstein, 2001; Svanbergsson et al., 2017). More likely, the causes and solutions involve how we use ourselves (e.g., how we stand, move, or respond to stress). A functional approach may include teaching awareness of the triggers that precede neck and back tension, skills to prevent the tensing of those muscles not needed for task performance, resolving psychosocial stress and improving the ergonomic factors that contribute to working in a stressed position (Peper, Harvey & Faass, 2020). Conceptually, how we are use ourselves (thoughts, emotions, and body) affects and transforms our physical structure and then our physical structure constrains how we use ourselves.

Watch the video with Alexander Teacher, Elyse Shafarman, who describes the Alexander Technique and guides you through practices that you can use immediately to optimize your health while sitting and moving.

See also the following posts:

References

Alexander, F.M. (2001). The Use of the Self. London: Orion Publishing. https://www.amazon.com/Use-Self-F-M-Alexander/dp/0752843915

Alexander technique. (2022). National Health Service. Retrieved 19 April, 2022/. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/alexander-technique/

Deyo, R.A. & Weinstein, J.N. (2001). Low back pain. N Engl J Med., 344(5),363-70. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200102013440508

Hamel, K.A., Ross, C., Schultz, B., O’Neill, M., & Anderson, D.I. (2016). Older adult Alexander Technique practitioners walk differently than healthy age-matched controls. J Body Mov Ther. 20(4), 751-760. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2016.04.009

Klein, S. D., Bayard, C., & Wolf, U. (2014). The Alexander Technique and musicians: a systematic review of controlled trials. BMC complementary and alternative medicine, 14, 414. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-14-414

Little, P. Lewith, W G., Webley, F., Evans, M., …(2008). Randomised controlled trial of Alexander technique lessons, exercise, and massage (ATEAM) for chronic and recurrent back pain. BMJ, 337:a884. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a884

MacPherson, H., Tilbrook, H., Richmond, S., Woodman, J., Ballard, K., Atkin, K., Bland, M., et al. (2015). Alexander Technique Lessons or Acupuncture Sessions for Persons With Chronic Neck Pain: A Randomized Trial. Ann Intern Med, 163(9), 653-62. https://doi.org/10.7326/M15-0667

Murphy, M. (1993). The Future of the Body. New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Perigee.

Preece, S.J., Jones, R.K., Brown, C.A. et al. (2016). Reductions in co-contraction following neuromuscular re-education in people with knee osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 17, 372. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-016-1209-2

Stallibrass, C., Sissons, P., & Chalmers. C. (2002). Randomized controlled trial of the Alexander technique for idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Clin Rehabil, 16(7), 695-708. https://doi.org/10.1191/0269215502cr544oa

Svanbergsson, G., Ingvarsson, T., & Arnardóttir RH. (2017). [MRI for diagnosis of low back pain: Usability, association with symptoms and influence on treatment]. Laeknabladid, 103(1):17-22. Icelandic. https://doi.org/10.17992/lbl.2017.01.116

Tuomilehto, J., Lindström, J., Eriksson, J.G., Valle, T.T., Hämäläinen, H., Ilanne-Parikka, P., Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi, S., Laakso, M., Louheranta, A., Rastas, M., et al. (2001). Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N. Engl. J. Med., 344, 1343–1350. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200105033441801

Uusitupa, Mm, Khan, T.A., Viguiliouk, E., Kahleova, H., Rivellese, A.A., Hermansen, K., Pfeiffer, A., Thanopoulou, A., Salas-Salvadó, J., Schwab, U., & Sievenpiper. J.L. (2019). Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes by Lifestyle Changes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients, 11(11)2611. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11112611

Posture affects memory recall and mood

Posted: November 25, 2017 Filed under: Exercise/movement, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: cognitive therapy, depression, empowerment, energy, helplessness, memory, mood, posture, power posture, somatics 5 CommentsThis blog has been reprinted from: Peper, E., Lin, I-M., Harvey, R., & Perez, J. (2017). How posture affects memory recall and mood. Biofeedback, 45 (2), 36-41.

When I sat collapsed looking down, negative memories flooded me and I found it difficult to shift and think of positive memories. While sitting erect, I found it easier to think of positive memories. -Student participant

The link between posture and mood is embedded in idiomatic phrases such as walking tall, standing proud, and an upstanding citizen, versus collapsed, defeated, or in a slump–Language suggests that posture and mood/emotions are connected. Slumped posture is commonly observed in depression (Canales et al., 2010; Michalak et al., 2009) and adapting an upright posture increases positive affect, reduces fatigue, and increases energy in people with mild to moderate depression (Wilkes et al., 2017; Peper & Lin, 2012).

The link between posture and mood is embedded in idiomatic phrases such as walking tall, standing proud, and an upstanding citizen, versus collapsed, defeated, or in a slump–Language suggests that posture and mood/emotions are connected. Slumped posture is commonly observed in depression (Canales et al., 2010; Michalak et al., 2009) and adapting an upright posture increases positive affect, reduces fatigue, and increases energy in people with mild to moderate depression (Wilkes et al., 2017; Peper & Lin, 2012).

This blog describes in detail our research study that demonstrated how posture affects memory recall (Peper et al, 2017). Our findings may explain why depression is increasing the more people use cell phones. More importantly, learning posture awareness and siting more upright at home and in the office may be an effective somatic self-healing strategy to increase positive affect and decrease depression.

Background

Most psychotherapies tend to focus on the mind component of the body-mind relationship. On the other hand, exercise and posture focus on the body component of the mind/emotion/body relationship. Physical activity in general has been demonstrated to improve mood and exercise has been successfully used to treat depression with lower recidivism rates than pharmaceuticals such as sertraline (Zoloft) (Babyak et al., 2000). Although the role of exercise as a treatment strategy for depression has been accepted, the role of posture is not commonly included in cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) or biofeedback or neurofeedback therapy.

The link between posture, emotions and cognition to counter symptoms of depression and low energy have been suggested by Wilkes et al. (2017) and Peper and Lin (2012), . Peper and Lin (2012) demonstrated that if people tried skipping rather than walking in a slouched posture, subjective energy after the exercise was significantly higher. Among the participants who had reported the highest level of depression during the last two years, there was a significant decrease of subjective energy when they walked in slouched position as compared to those who reported a low level of depression. Earlier, Wilson and Peper (2004) demonstrated that in a collapsed posture, students more easily accessed hopeless, powerless, defeated and other negative memories as compared to memories accessed in an upright position. More recently, Tsai, Peper, and Lin (2016) showed that when participants sat in a collapsed position, evoking positive thoughts required more “brain activation” (i.e. greater mental effort) compared to that required when walking in an upright position.

Even hormone levels also appear to change in a collapsed posture (Carney, Cuddy, & Yap, 2010). For example, two minutes of standing in a collapsed position significantly decreased testosterone and increased cortisol as compared to a ‘power posture,’ which significantly increased testosterone and decreased cortisol while standing. As Professor Amy Cuddy pointed out in herTechnology, Entertainment and Design (TED) talk, “By changing posture, you not only present yourself differently to the world around you, you actually change your hormones” (Cuddy, 2012). Although there appears to be controversy about the results of this study, the overall findings match mammalian behavior of dominance and submission. From my perspective, the concepts underlying Cuddy’s TED talk are correct and are reconfirmed in our research on the effect of posture. For more detail about the controversy, see the article by Susan Dominusin in the New York Times, “When the revolution came for Amy Cuddy,”, and Amy Cuddy’s response (Dominus, 2017;Singal and Dahl, 2016).

The purpose of our study is to expand on our observations with more than 3,000 students and workshop participants. We observed that body posture and position affects recall of emotional memory. Moreover, a history of self-described depression appears to affect the recall of either positive or negative memories.

Method

Subjects: 216 college students (65 males; 142 females; 9 undeclared), average age: 24.6 years (SD = 7.6) participated in a regularly planned classroom demonstration regarding the relationship between posture and mood. As an evaluation of a classroom activity, this report of findings was exempted from Institutional Review Board oversight.

Procedure

While sitting in a class, students filled out a short, anonymous questionnaire, which asked them to rate their history of depression over the last two years, their level of depression and energy at this moment, and how easy it was for them to change their moods and energy level (on a scale from 1–10). The students also rated the extent they became emotionally absorbed or “captured” by their positive or negative memory recall. Half of the students were asked to rate how they sat in front of their computer, tablet, or mobile device on a scale from 1 (sitting upright) to 10 (completely slouched).

Two different sitting postures were clearly defined for participants: slouched/collapsed and erect/upright as shown in Figure 1. To assume the collapsed position, they were asked to slouch and look down while slightly rounding the back. For the erect position, they were asked to sit upright with a slight arch in their back, while looking upward.

Figure 1. Sitting in a collapsed position and upright position (photo by Jana Asenbrennerova). Reprinted by permission from Gorter and Peper (2011).

Figure 1. Sitting in a collapsed position and upright position (photo by Jana Asenbrennerova). Reprinted by permission from Gorter and Peper (2011).

After experiencing both postures, half the students sat in the collapsed position while the other half sat in the upright position. While in this position, they were asked to recall/evoke as many hopeless, helpless, powerless, or defeated memories as possible, one after the other, for 30 seconds.

After 30 seconds they were reminded to keep their same position and let go of thinking negative memories. They were then asked to recall/evoke only positive, optimistic, or empowering memories for 30 seconds.

They were then asked to switch positions. Those who were collapsed switched to sitting erect, and those who were erect switched to sitting collapsed. Then they were again asked to recall/evoke as many hopeless, helpless, powerless, or defeated memories as possible one after the other for 30 seconds. After 30 seconds they were reminded to keep their same position and again let go of thinking of negative memories. They were then asked to recall/evoke only positive, optimistic, or empowering memories for 30 seconds, while still retaining the second posture.

They then rated their subjective experience in recalling negative or positive memories and the degree to which they were absorbed or captured by the memories in each position, and in which position it was easier to recall positive or negative experiences.

Results

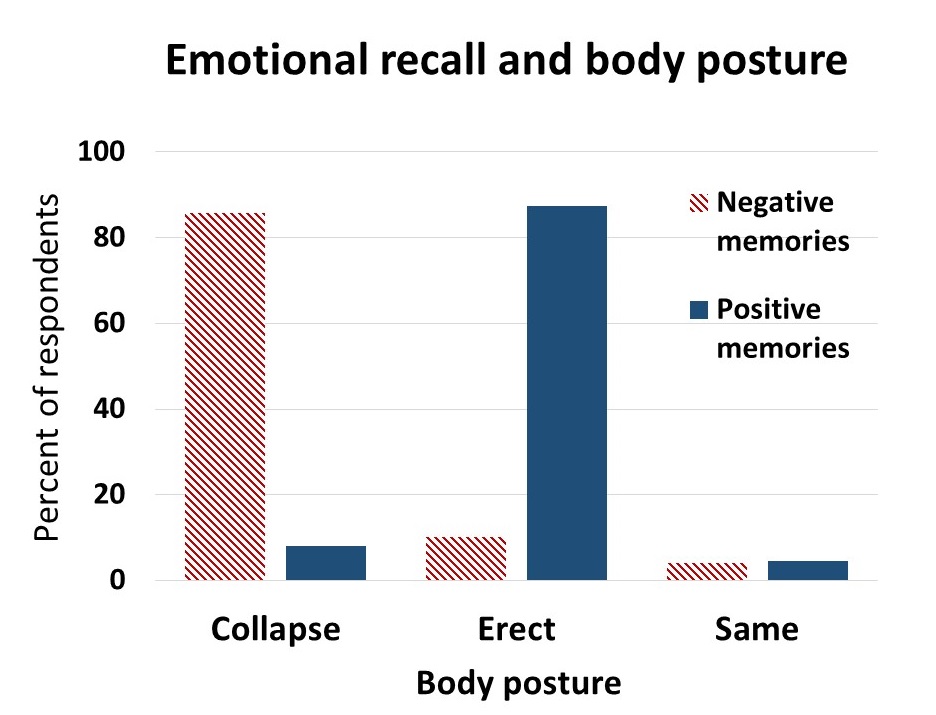

86% of the participants reported that it was easier to recall/access negative memories in the collapsed position than in the erect position, which was significantly different as determined by one-way ANOVA (F(1,430)=110.193, p < 0.01) and 87% of participants reported that it was easier to recall/access positive images in the erect position than in the collapsed position, which was significantly different as determined by one-way ANOVA (F(1,430)=173.861, p < 0.01) as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Percent of respondents who reported that it was easier to recall positive or negative memories in an upright or slouched posture.

Figure 2. Percent of respondents who reported that it was easier to recall positive or negative memories in an upright or slouched posture.

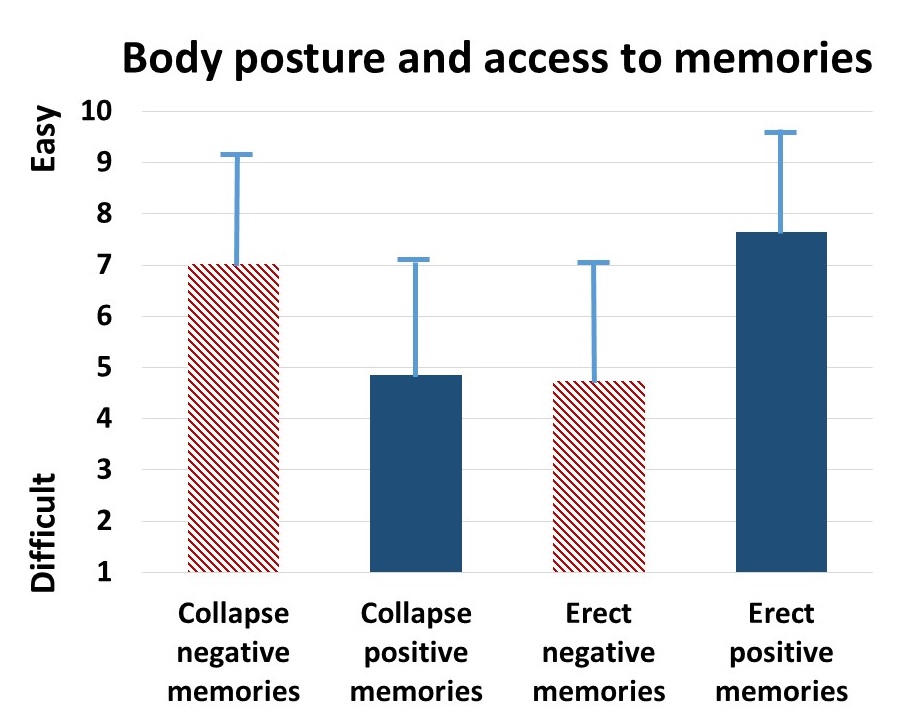

The difficulty or ease of recalling negative or positive memories varied depending on position as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. The relative subjective rating in the ease or difficulty of recalling negative and positive memories in collapsed and upright positions.

Figure 3. The relative subjective rating in the ease or difficulty of recalling negative and positive memories in collapsed and upright positions.

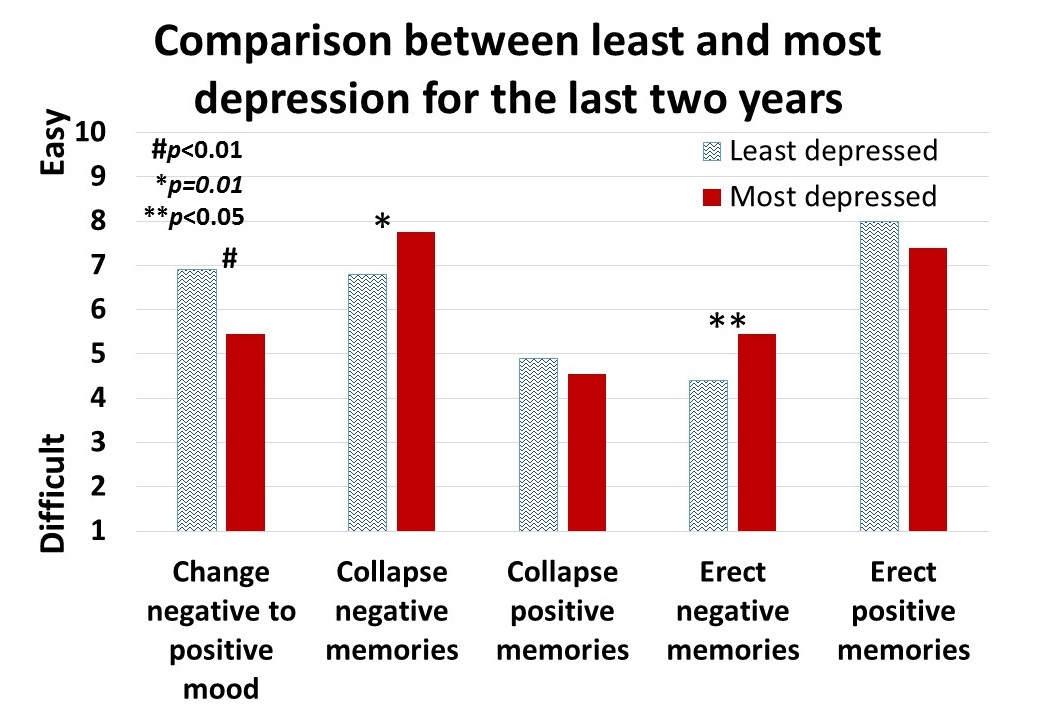

The participants with a high level of depression over the last two years (top 23% of participants who scored 7 or higher on the scale of 1–10) reported that it was significantly more difficult to change their mood from negative to positive (t(110) = 4.08, p < 0.01) than was reported by those with a low level of depression (lowest 29% of the participants who scored 3 or less on the scale of 1–10). It was significantly easier for more depressed students to recall/evoke negative memories in the collapsed posture (t(109) = 2.55, p = 0.01) and in the upright posture (t(110) = 2.41, p ≦0.05 he) and no significant difference in recalling positive memories in either posture, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Differences is in memory access for participants with a history of least or most depression.

Figure 4. Differences is in memory access for participants with a history of least or most depression.

For all participants, there was a significant correlation (r = 0.4) between subjective energy level and ease with which they could change from negative to positive mood. There were no significance differences for gender in all measures except that males reported a significantly higher energy level than females (M = 5.5, SD = 3.0 and M = 4.7, SD = 3.8, respectively; t(203) = 2.78, p < 0.01).

A subset of students also had rated their posture when sitting in front of a computer or using a digital device (tablet or cell phone) on a scale from 1 (upright) to 10 (completely slouched). The students with the highest levels of depression over the last two years reporting slouching significantly more than those with the lowest level of depression over the last two years (M = 6.4, SD = 3.5 and M = 4.6, SD = 2.6; t(46) = 3.5, p < 0.01).

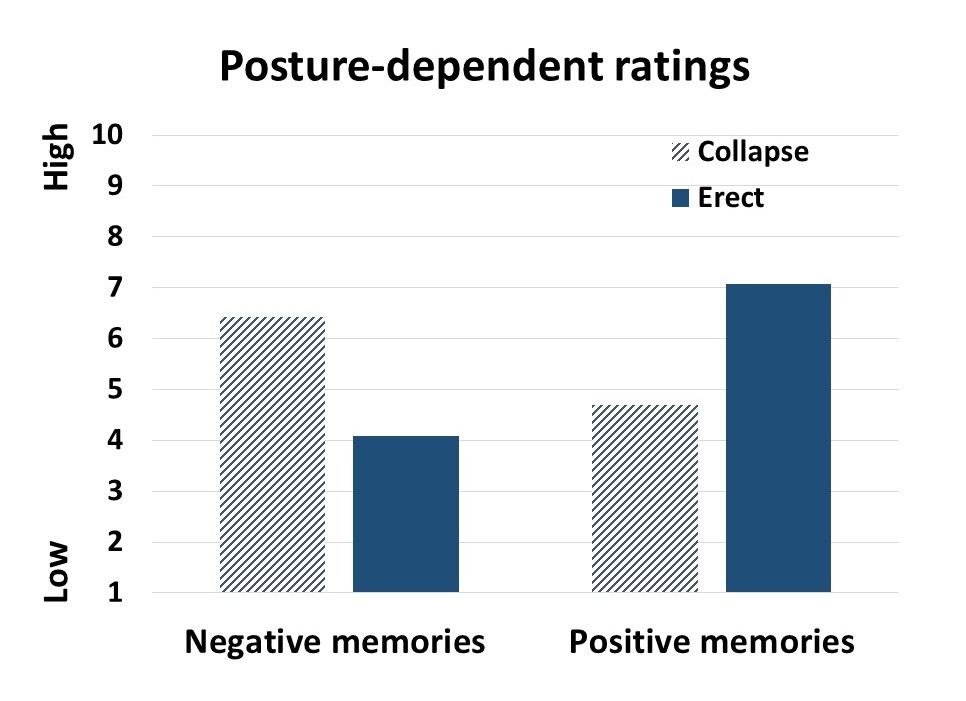

There were no other order effects except of accessing fewer negative memories in the collapsed posture after accessing positive memories in the erect posture (t(159)=2.7, p < 0.01). Approximately half of the students who also rated being “captured” by their positive or negative memories were significantly more captured by the negative memories in the collapsed posture than in the erect posture (t(197) = 6.8, p < 0.01) and were significantly more captured by positive memories in the erect posture than the collapsed posture (t(197) = 7.6, p < 0.01), as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Subjective rating of being captured by negative and positive memories depending upon position.

Figure 5. Subjective rating of being captured by negative and positive memories depending upon position.

Discussion

Posture significantly influenced access to negative and positive memory recall and confirms the report by Wilson and Peper (2004). The collapsed/slouched position was associated with significantly easier access to negative memories. This is a useful clinical observation because ruminating on negative memories tends to decrease subjective energy and increase depressive feelings (Michi et al., 2015). When working with clients to change their cognition, especially in the treatment of depression, the posture may affect the outcome. Thus, therapists should consider posture retraining as a clinical intervention. This would include teaching clients to change their posture in the office and at home as a strategy to optimize access to positive memories and thereby reduce access or fixation on negative memories. Thus if one is in a negative mood, then slouching could maintain this negative mood while changing body posture to an erect posture, would make it easier to shift moods.

Physiologically, an erect body posture allows participants to breathe more diaphragmatically because the diaphragm has more space for descent. It is easier for participants to learn slower breathing and increased heart rate variability while sitting erect as compared to collapsed, as shown in Figure 6 (Mason et al., 2017).

Figure 6. Effect of posture on respiratory breathing pattern and heart rate variability.

Figure 6. Effect of posture on respiratory breathing pattern and heart rate variability.

The collapsed position also tends to increase neck and shoulder symptoms This position is often observed in people who work at the computer or are constantly looking at their cell phone—a position sometimes labeled as the i-Neck.

Implication for therapy

In most biofeedback and neurofeedback training sessions, posture is not assessed and clients sit in a comfortable chair, which automatically causes a slouched position. Similarly, at home, most clients sit on an easy chair or couch, which lets them slouch as they watch TV or surf the web. Finally, most people slouch when looking at their cellphone, tablet, or the computer screen (Guan et al., 2016). They usually only become aware of slouching when they experience neck, shoulder, or back discomfort.

Clients and therapists are usually not aware that a slouched posture may decrease the client’s energy level and increase the prevalence of a negative mood. Thus, we recommend that therapists incorporate posture awareness and training to optimize access to positive imagery and increase energy.

References

Singal, J. and Dahl, M. (2016, Sept 30 ) Here Is Amy Cuddy’s Response to Critiques of Her Power-Posing Research. https://www.thecut.com/2016/09/read-amy-cuddys-response-to-power-posing-critiques.html

We thank Frank Andrasik for his constructive comments.