Implement your New Year’s resolution successfully[1]

Posted: December 29, 2024 Filed under: attention, behavior, CBT, cognitive behavior therapy, education, emotions, Exercise/movement, healing, health, self-healing | Tags: goal setting, health, lifestyle, motivation, performance, personal-development Leave a comment

Adapted from: Peper, E. Pragmatic suggestions to implement behavior change. Biofeedback.53(2), 41-45. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-53.02.05

Ready to crush your New Year’s resolutions and actually stick to them this time? Whether you’re determined to quit vaping or smoking, cut back on sugar and processed foods, reduce screen time, get moving, volunteer more, or land that dream job, sticking to your goals is the real challenge. We’ve all been there: kicking off the year with ambitious plans like, “I’ll work out every day,” or “I’m done with junk food for good.” But a few weeks in? The gym is a distant memory, the junk food stash is back, and those cigarettes are harder to let go of than expected.

So, how can you make this year different? Here are some tried-and-true tips to help you turn those resolutions into lasting habits:

Be clear of your goal and state exactly what you want to do (Pilcher et al., 2022; Latham & Locke, 2006).

Did you know your brain is super literal and doesn’t process “not” the way you think it does? For example, if you say, “I will not smoke,” your brain has to first imagine you smoking, then mentally cross it out. Guess what? By rehearsing the act of smoking in your mind, you’re actually increasing the chances that you’ll light up again.

Think of it like this: hand a four-year-old a cup of hot chocolate and ask them to walk it over to someone across the room. Halfway there, you call out, “Be careful, don’t spill it!” What usually happens? Yep, the hot chocolate spills. That’s because the brain focuses on “spill,” not the “don’t.” Now, imagine instead you say, “You’re doing great! Keep walking steadily.” Positive framing reinforces the action you want to see. The lesson is to reframe your goals in a way that focuses on what you want to achieve, not what you’re trying to avoid. Let’s look at some examples to get you started:

| Negative framing | Positive framing |

| I plan to stop smoking | I choose to become a nonsmoker |

| I will eat less sugar and ultra-processed foods | I will shop at the farmer’s market, buy more fresh vegetable and prepare my own food. |

| I will reduce my negative thinking (e.g., the glass is half empty). | I will describe events and thoughts positively (e.g., the class is half full). |

Describe what you want to do positively.

Be precise and concrete.

The more specific you can describe what you plan to do, the more likely will it occur as illustrated in the following examples.

| Imprecise | Concrete and specific |

| I will begin exercising. | I will buy the gym membership next week Monday and will go to the gym on Monday, Wednesday and Friday right after work at 5:30pm for 45 minutes. |

| I will reduce my angry outbursts, | Before I respond, I will take a slow breath, look up, relax my shoulders and remind myself that the other person is doing their best. |

| I want to limit watching streaming videos | At home, I will move the couch so that it does not face the large TV screen, and I have enrolled in a class to learn another language and I will spent 30 minutes in the evening practicing the new language. |

| I will stop smoking | When I feel the initial urge to smoke, I stand up, do a few stretches, and practice box breathing and remind myself that I am a nonsmoker. |

Describe in detail what you will do.

Identify the benefits of the old behavior that you want to change and how you can achieve the same benefits with your new behavior. (Peper et al, 2002)

When setting a New Year’s resolution, it’s easy to focus on the perks of the new behavior and the harms of the old behavior while overlooking the benefits your old habit provided. However, if you don’t plan ways to achieve the same benefits, the old behavior provided, it’s much harder to stick to your goal.

Before diving into your new resolution, take a moment to reflect. What did your old behavior do for you? What needs did it meet? Once you identify those, you can develop strategies to achieve the same benefits in healthier, more constructive ways.

For example, let’s say your goal is to stop smoking. Smoking might have helped you relax during stressful moments or provided a social activity with friends. To make the switch, you’ll need to find alternatives that deliver similar results, like practicing deep-breathing exercises to manage stress or inviting friends for a walk instead of a smoke break. By creating a plan to meet those needs, you’ll set yourself up for lasting success.

| Benefits of smoking | How to achieve the same benefits when being a none smoker |

| Stress reduction | I will learn relaxation and diaphragmatic breathing. The moment, I feel the urge to smoke, I sit up, look up, raise my shoulder and dropped them, and breathe slowly |

| Breaks during work | I will install a reminder on my cellphone to ping and each time it pings, I stop, stand up, walk around and stretch. |

| Meeting with friends | I will tell my friends, not to offer me a cigarette and I will spent time with friends who are non-smokers. |

| Rebelling against my parents who were opposed to smoking | I will explore how to be independent without smoking |

Describe your benefits and how you will achieve them.

Reduce the cues that evoke the old behavior and create new cues that will trigger the new behavior (Peper & Wilson, 2021).

A lot of our behavior is automatic—shaped by classical conditioning, just like Pavlov’s dog. Remember the famous experiment? Pavlov paired the sound of a bell with food, and after a while, the bell alone made the dog salivate (McLeod, 2024). We’re not so different.

Think about it: if you’ve gotten into the habit of smoking in your car, simply sitting in the driver’s seat can trigger the automatic urge to grab a cigarette. Or, if you tend to feel depressed when you’re home but better when you’re out with friends, your home environment might be acting as a cue for those feelings.

Interestingly, many people find it easier to change habits in a new environment. Why? Because there are no built-in triggers to reinforce the behavior they’re trying to change. This highlights how much of what we often call “addiction” might actually be conditioned behavior, reinforced by familiar cues in our surroundings. By recognizing the power of these triggers can help you disrupt old patterns. By creating a fresh environment or consciously changing your responses to cues, you can take control and start forming new, healthier habits.

This concept has been understood for centuries by some hunting and gathering societies. When something tragic happened—like the death of a family member in a hut—the community would often burn the hut to “eliminate the evil spirit.” Beyond the spiritual aspect, this practice served a practical purpose: it removed all the physical cues that reminded people of their loss, making it easier to focus on the present and move forward.

Of course, I’m not suggesting you destroy your home. But the underlying principle still holds true in modern times. In fact, many Northern European cultures incorporate a version of this idea through the ritual of Spring Cleaning. By decluttering, rearranging furniture, and refreshing the home, the old cues are removed and create a sense of renewal.

So often we forget that cues in our environment play a powerful role in triggering our behavior. By identifying the triggers that evoke old habits and finding ways to remove or change them, you can create a fresh environment that supports your goals. For example, if you’re trying to stop snacking on junk food late at night, consider rearranging your pantry so the tempting items are out of sight—or better yet, replace them with healthier options. Small changes like this can have a big impact on your ability to stay on track.

| Cues that triggered the behavior | How cues were changed |

| In the evening going to the kitchen and getting the chocolate from the cupboard. | Buying fruits and have them on the table and not buying chocolate. If I do buy chocolate store it on the top shelf away so that I do not see it or store it in the freezer. |

| Getting home and being depressed. | Clean the house, change the furniture around and put positive picture high up on the wall. |

| Smoking in the car. | Replace the car with another car that no one had smoked in and spray the care with pine scent. |

Identify the cues that trigger your behavior and how you changed them.

Identify the first sensation that triggered the behavior you would like to change.

Whether it’s smoking, drinking, scratching your skin, spiraling into negative thoughts, or eating too many pastries, once a behavior starts, it can feel nearly impossible to stop. That’s why the key is to catch yourself before the habit takes over., t’s much easier to interrupt a pattern at the very first sign—the initial trigger—rather than after you’ve fully dived into the behavior. Yet how often do we find ourselves saying, “Next time, I’ll do it differently”?

Here’s the strategy: identify the first trigger. This could be a physical sensation, an emotion, a thought, or an external cue. Once you’re aware of that first flicker of a trigger, redirect your thoughts and actions toward what you actually want, rather than letting the automatic behavior take control. For example:

I just came home at 10:15 PM and felt lonely and slightly depressed. I walked into the kitchen, opened the fridge, grabbed a beer, and drank it. Then, I reached for another bottle.

Observing this behavior, the first trigger was the loneliness and slight depression upon arriving home. Recognizing that feeling in the moment offers an opportunity to pause and make a conscious choice. Instead of heading to the fridge, you could redirect your actions—call a friend, go for a quick walk, or write down your thoughts in a journal. By catching that initial trigger, you can focus yourself toward healthier behaviors and break the cycle.

| First sensation | Changed response to the sensation |

| I observed that the first sensation was feeling tired and lonely. | When I entered the house, instead of going to the kitchen, I stretched, looked up and took a deep breath and then called a close friend of mine. We talked for ten minutes and then I went to bed. |

Identify your first sensation and how you changed your behavior.

Incorporate social support and social accountability (Drageset, 2021).

Doing something on your own often requires a lot of willpower, and sticking to it every time can feel like an uphill battle. Take this example:

My goal is to exercise every other morning. But last night, I stayed up late and felt tired in the morning, so I skipped my workout.

Sound familiar? Now imagine if I’d planned to meet a workout buddy. Knowing someone was counting on me would’ve gotten me out of bed, even if I was tired, because I wouldn’t want to let them down.

Accountability can make all the difference. Another powerful strategy is sharing your goals publicly. When you announce your plans on social media or to friends and family, you create a sense of commitment—not just to yourself but to others. It’s like having a built-in support system cheering you on and holding you accountable. Whether it’s finding a partner, joining a group, or sharing your progress online, involving others can help turn your resolutions into habits you’re more likely to stick with.

Describe a strategy to increase social support and accountability.

Be honest in identifying what motivates you.

Exercising, eating healthy foods, thinking positively, or being on time are laudable goals; however, it often feels like work doing the “right” thing. To increase success, analyze what really helped you be successful. For example:

Many years ago, I decided that I should exercise more. Thus, I drove from house to the track and ran eight laps. I did this for the next three weeks and then stopped exercising. Eventually, I pushed myself again to exercise and after a while stopped again. The same pattern kept repeating. I would exercise and fall off the wagon and stop. Later that fall, I met a woman who was a jogger and we became friends and for the next year we jogged together and even did races. During this time, I did not experience any effort to go jogging. After a year, she broke up with me and once again, I had to use willpower to go jogging and my old pattern emerged and after a few days I stopped jogging even though I felt much better after having jogged.

I finally, asked what is going on? I realized that the joy of the jogging was running with a friend. Once, I recognized this, instead using will power to go running, I spent my willpower finding people with whom I could exercise. With these new friends, running did not depend upon my willpower– It only depended on making running dates with my new friends.

Explore factors that will allow you to do your activity without having to use willpower.

Conclusion

These seven strategies are just a starting point—there are countless other techniques that can help you stick to your New Year’s resolutions. For example, keeping a log, setting reminders, or rewarding yourself for progress are all powerful ways to stay on track. The real magic happens when your new behavior becomes part of your routine—embedded in your habitual patterns. The more automatic it feels, the greater your chances of long-term success.

So, take joy in identifying, implementing, and maintaining your resolutions. Let them enhance your well-being and become second nature. Share your successful strategies with me and others—it could be just the inspiration someone else needs to achieve their goals, too.

References

Drageset, J. (2021). Social Support. In: Haugan G, Eriksson M, editors. Health Promotion in Health Care – Vital Theories and Research [Internet]. Cham (CH): Springer, Chapter 11. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK585650/ https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-63135-2_11

Latham, G. P., & Locke, E. A. (2006). Enhancing the Benefits and Overcoming the Pitfalls of Goal Setting. Organizational Dynamics, 35(4), 332–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2006.08.008

McLeod, S. (2024). Classical Conditioning: How It Works With Examples.Simple Psychology. Accessed December 29, 2024. https://www.simplypsychology.org/classical-conditioning.html

Peper, E., Gibney, H. K. & Holt, C. (2002). Make Health Happen. Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall-Hunt. (Pp 185-192). https://he.kendallhunt.com/make-health-happen

Peper, E. & Wilson, V. (2021). Optimize the learning state: techniques and habits. Biofeedback, 9(2), 46-49. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-49-2-04

Pilcher, S., Schweickle, M. J., Lawrence, A., Goddard, S. G., Williamson, O., Vella, S. A., & Swann, C. (2022). The effects of open, do-your-best, and specific goals on commitment and cognitive performance. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 11(3), 382–395. https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000301

For detailed suggestions, see the following blogs:

[1] Edited with the help of ChatGPT.

Pragmatic techniques for monitoring and coaching breathing

Posted: December 14, 2024 Filed under: attention, behavior, biofeedback, Breathing/respiration, emotions, meditation, mindfulness, neurofeedback, Pain/discomfort, posture, relaxation, self-healing, Uncategorized | Tags: art, books, Breathing rate, coaching, FlowMD app, nasal breathing, personal-development, self-monitoring, writing 4 CommentsDaniella Matto, MA, BCIA BCB-HRV , Erik Peper, PhD, BCB, and Richard Harvey, PhD

Adapted from: Matto, D., Peper, E., & Harvey, R. (2025). Monitoring and coaching breathing patterns and rate. Townsend Letter-Innovative Health Perspectives. https://townsendletter.com/monitoring-and-coaching-breathing-patterns-and-rate/

This blog aims to describe several practical strategies to observe and monitor breathing patterns to promote effortless diaphragmatic breathing. The goal of these strategies is to foster effortless, whole-body diaphragmatic breathing that promote health.

Breathing is usually covert and people are not usually aware of their breathing rate (breaths per minute) or pattern (abdominal or thoracic, breath holding or shallow breathing) unless they have an illness such as asthma, emphysema or are performing physical activity (Boulding et al, 2015)). Observing breathing is challenging; awareness of respiration often leads to unaware changes in the breath pattern or to an attempt to breathe perfectly (van Dixhoorn, 2021). Ideally breathing patterns should be observed/monitored when the person is unaware of their breathing pattern and the whole body participates (van Dixhoorn, 2008). A useful strategy is to have the person perform a task and then ask, “What happened to your breathing?”. For example, ask a person to simulate putting a thread through the eye of a needle or quickly look to the extreme right and left while keeping their head still. In almost all cases, the person holds their breath (Peper et al., 2002).

Teaching effortless slow diaphragmatic breathing is a precursor of Heart rate variability (HRV) biofeedback and is based on slow paced breathing (Lehrer & Gevirtz, 2014; Steffen et al., 2017; Shaffer and Meehan, 2020). Mastering effortless diaphragmatic breathing is a powerful tool in the treatment of a variety of physical, behavioural, and cognitive conditions; however, to integrate this method into clinical or educational practice is easier said than done. Clients with dysfunctional breathing patterns often have difficulty following a breath pacer or mastering effortless breathing at a slower pace.

The purpose of this paper is to describe a few simple strategies that can be used to observe and monitor breathing patterns, provide economic strategies for observation and training, and suggestions to facilitate effortless diaphragmatic breathing.

Strategies to observe and monitor breathing pattern

Observation of the breathing patterns

- Is the breathing through the nose or mouth? Nose is usually better (Watso et al., 2023; Nestor, 2020).

- Does the abdomen expand during inhalation and constricts during exhalation or does the chest expand and rise during inhalation and fall during exhalation? Abdominal movement is usually better.

- Is exhalation flow softly or explosively like a sigh? Slow flow exhalation is preferred.

- Is the breath held or continues during activities? In most cases continued breathing is usually better.

- Does the person gasp before speaking or allows to speak while normally exhaling?

- What is the breathing rate (breaths per minute)? When sitting peacefully less than 14 breaths/minute is usually better and about 6 breaths per minute to optimize HRV

Physiological monitoring.

- Monitoring breathing with strain gauges around the abdomen and chest, and heart rate is the most common approach to identify the location of breath, the breathing pattern and heart rate variability. The strain gauges are placed around the chest and abdomen and heart rate is monitored with a blood volume pulse amplitude sensor from the finger. representative recording shows the effect of thoughts on breathing, heartrate and pulse amplitude of which the participant is totally unaware as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Physiological recording of breathing patterns with strain gauges.

- Monitoring breathing with a thermistor placed at the entrance of the nostril that has the most airflow (nasal patency) (Jovanov et al., 2001; Lerman et al., 2016). When the person exhales through the nose, the thermistor temperature increases and decreases when they inhale. A representative recording of a person being calm, thinking a stressful thought. and being calm. Although there were significant changes as indicated by the change in breathing patterns, the person was unaware of the changes as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Use of a thermistor to monitor breathing from the dominant nostril compared to the abdominal expansion as monitored by a strain gauge around the abdomen.

- Additional physiological monitoring approaches. There are many other physiological measures can be monitored to such as end-tidal carbon dioxide (EtCO2), a non-invasive measurement of the amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) in exhaled breath (Meuret et al., 2008; Meckley, 2013); scalene/trapezius EMG to identify thoracic breathing (Peper & Tibbett, 1992; Peper & Tibbets, 1994); low abdominal EMG to identify transfers and oblique tightening during exhalation and relaxation during inhalation (Peper et al., 2016; and heart rate to monitor cardiorespiratory synchrony (Shaffer & Meehan, 2020). Physiological monitoring is useful; since, the clinician and the participant can observe the actual breathing pattern in real time, how the pattern changes in response the cognitive and physical tasks, and used for feedback training. The recorded data can document breathing problems and evidence of mastery.

The challenges of using physiological monitoring arethat the equipment may be expensive, takes skill to operate and interpret the data, and is usually located in the office and not at home.

Economic strategies for observation and training breathing

To complement the physiological monitoring and allow observations outside the office and at home, some of the following strategies may be used to observe breathing pattern (rate and expansion of the breath in the body), and suggestion to facilitate effortless diaphragmatic breathing. These exercises make excellent homework for the client. Practicing awareness and internal self-regulation by the client outside the clinic contributes enormously to the effect of biofeedback training (Wilson et al., 2023),

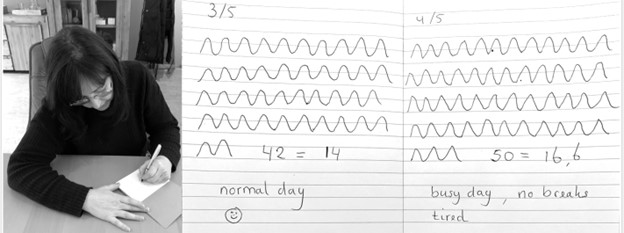

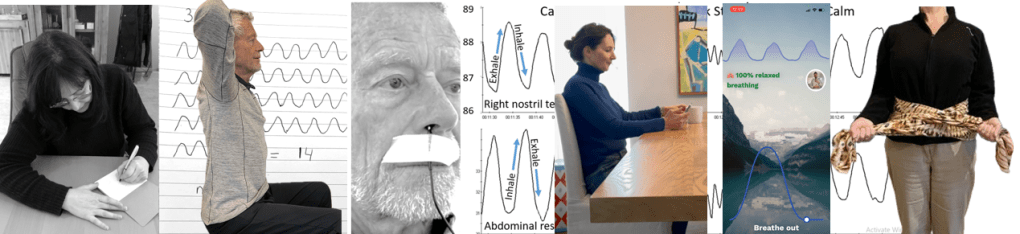

Observe breathing rate: Draw the breathing pattern

Take a piece of paper, a pen and a timer, set to 3 minutes. Start the timer. Upon inhalation draw the line up and upon exhalation draw the line down, creating a wave. When the timer stops, after 3 minutes, calculate the breathing rate per minute by dividing the number of waves by 3 as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Drawing the breathing pattern for three minutes during two different days.

From these drawings, the breathing rate become evident. Many individuals are often surprised to discover that their breathing rate increased during periods of stress, such as a busy day with no breaks, compared to their normal days.

Monitoring and training diaphragmatic breathing

The scarf technique for abdominal feedback

Many participants are unaware that they are predominantly breathing in their chest and their abdomen expansion is very limited during inhalation. Before beginning, have participant loosen their belt and or stand upright since sitting collapsed/slouched or having the waist constriction such as a belt of tight constrictive clothing that inhibits abdominal expansion during inhalation.

Place the middle part of a long scarf or shawl on your lower back, take the ends in both hands and cross the ends: your left hand is holding the right part of the scarf, and the right hand is holding the left end of the scarf. Give a bit of a pull, so you can feel any movement of the scarf. When breathing more abdominally you will feel a pull at the ends of the scarf as you lower back, and flanks will expand as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Using a scarf as feedback.

FlowMD app

A recent cellphone app, FlowMD, is unique because it uses the cellphone camera to detect the subtle movements of the chest and abdomen (FlowMD, 2024). It provides real time feedback of the persons breathing pattern. Using this app, the person sits in front of their cellphone camera and after calibration, the breathing pattern is displayed as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Training breathing with FlowMD,.

Suggestions to optimize abdominal breathing that may lead to a slower breath rate when the client practices the technique

Beach pose

By locking the upper chest and sitting up straight it is often easier to breathe so that the abdomen can expand and constrict. Place your hands behind your head and Interlock your finger of both hands, pull your elbows back and up. The person can practice this either laying down on their back or sitting straight up at the edge of the chair as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Sitting erect with the shoulders pulled back and up to allow abdominal expansion and constriction as the breathing pattern.

Observe the effect of posture on breathing

Have the person sit slouched/collapsed like a letter C and take a few slow breath, then have them sit up in a tall and erect position and take a few slow breaths. Usually they will observe that it is easier to breathe slower and lower and tall and erect.

Using your hands for feedback to guide natural breathing

Holding your hands with index fingers and thumbs touching the lower abdomen. When inhaling the fingers and thumbs separate and when exhaling they touch again (ensuring a full exhale and avoiding over breathing). The slight increase in lower abdominal muscle tension during the exhalation and relaxation during inhalation and the abdominal wall expands can also be felt with fingertips as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Using your hands and finger for feedback to guide the natural breathing of expansion and constriction of the abdomen. Reproduced by permission from Peper, E., Booiman, A., Lin, I-M, Harvey, R., & Mitose, J. (2016). Abdominal SEMG Feedback for Diaphragmatic Breathing: A Methodological Note. Biofeedback. 44(1), 42-49.

Coaching suggestions

There are many strategies to observe, teach and implement effortless breathing (Peper et al., 2024).. Even though breathing is natural and babies and young children breathe diaphragmatically as their large belly expands and constricts. Yet, in many cases the natural breathing shifts to dysfunctional breathing for multiple reasons such as chronic triggering defense reactions to avoiding pain following abdominal surgery (Peper et al, 2015). When participants initially attempt to relearn this natural pattern, it can be challenging especially, if the person habitually breathes shallowly, rapidly and predominantly in their chest.

When initially teaching effortless breathing, have the person exhale more air than normal without the upper chest compressing down and instead allow the abdomen comes in and up thereby exhaling all the air. If the person is upright then allow inhalation to occur without effort by letting the abdominal wall relaxes and expands. Initially inhale more than normal by expanding the abdomen without lifting the chest. Then exhale very slowly and continue to breathe so that the abdomen expands in 360 degrees during inhalation and constricts during exhalation. Let the breathing go slower with less and less effort. Usually, the person can feel the anus dropping and relaxing during inhalation.

Another technique is to ask the person to breathe in more air than normal and then breathe in a little extra air to completely fill the lungs, before exhaling fully. Clients often report that it teaches them to use the full capacity of the lungs.

The goal is to breath without effort. Indirectly this can be monitored by finger temperature. If the finger temperature decreases, the participant most likely is over-breathing or breathing with too much effort, creating sympathetic activity; if the finger temperature increases, breathing occurs slower and usually with less effort indicating that the person’s sympathetic activation is reduced.

Conclusion

There are many strategies to monitor and coach breathing. Relearning diaphragmatic breathing can be difficult due to habitual shallow chest breathing or post-surgical adaptations. Initial coaching may involve extended exhalations, conscious abdominal expansion, and gentle inhalation without chest movement. Progress can be monitored through indirect physiological markers like finger temperature, which reflects changes in sympathetic activity. The integration of these techniques into clinical or educational practice enhances self-regulation, contributing significantly to therapeutic outcomes. In this article we provided a few strategies which may be useful for some clients.

Additional blogs on breathing

https://peperperspective.com/2015/09/25/resolving-pelvic-floor-pain-a-case-report/

REFERENCES

Boulding, R., Stacey, R., & Niven, N. (2016). Dysfunctional breathing: a review of the literature and proposal for classification. European Respiratory Review, 25(141),: 287-294. https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0088-2015

FlowMD. (2024). FlowMD app. Accessed December 13, 2024. https://desktop.flowmd.co/

Jovanov, E., Raskovic, D., & Hormigo, R. (2001). Thermistor-based breathing sensor for circadian rhythm evaluation. Biomedical sciences instrumentation, 37, 493–497. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11347441/

Lehrer, P. & Gevirtz R. (2014). Heart rate variability biofeedback: how and why does it work? Front Psychol, 5,756. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00756

Lerman, J., Feldman, D., Feldman, R. et al. Linshom respiratory monitoring device: a novel temperature-based respiratory monitor. (2016). Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth, 63, 1154–1160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-016-0694-y

Meckley, A. (2013). Balancing Unbalanced Breathing: The Clinical Use of Capnographic Biofeedback. Biofeedback, 41(4), 183–187. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-41.4.02

Meuret, A. E., Wilhelm, F. H., Ritz, T., & Roth, W. T. (2008). Feedback of end-tidal pCO2 as a therapeutic approach for panic disorder. Journal of psychiatric research, 42(7), 560–568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.06.005

Nestor, J. (2020). Breath: The New Science of a Lost Art. New York: Riverhead Books. https://www.amazon.com/Breath-New-Science-Lost-Art/dp/0735213615/

Peper, E., Booiman, A., Lin, I-M, Harvey, R., & Mitose, J. (2016). Abdominal SEMG Feedback for Diaphragmatic Breathing: A Methodological Note. Biofeedback. 44(1), 42-49. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-44.1.03

Peper, E., Gilbert, C.D., Harvey, R. & Lin, I-M. (2015). Did you ask about abdominal surgery or injury? A learned disuse risk factor for breathing dysfunction. Biofeedback. 34(4), 173-179. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-43.4.06

Peper, E., Gibney, K.H., & Holt, C.F. (2002). Make Health Happen. Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company. https://he.kendallhunt.com/product/make-health-happen-training-yourself-create-wellness

Peper, E., Oded, Y., Harvey, R., Hughes, P., Ingram, H., & Martinez, E. (2024). Breathing for health: Mastering and generalizing breathing skills. Townsend Letter-Innovative Health Perspectives. November 15, 2024. https://townsendletter.com/suggestions-for-mastering-and-generalizing-breathing-skills/

Peper, E., & Tibbetts, V. (1992). Fifteen-month follow-up with asthmatics utilizing EMG/incentive inspirometer feedback. Biofeedback and self-regulation, 17(2), 143–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01000104

Peper, E. & Tibbetts, V. (1994). Effortless diaphragmatic breathing. Physical Therapy Products. 6(2), 67-71. https://biofeedbackhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/peper-and-tibbets-effortless-diaphragmatic.pdf

Shaffer, F. and Meehan, Z.M. (2020). A Practical Guide to Resonance Frequency Assessment for Heart Rate Variability Biofeedback. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 14. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnins.2020.570400

Steffen, P.R., Austin, T., DeBarros, A., and Brown, T. (2017). The Impact of Resonance Frequency Breathing on Measures of Heart Rate Variability, Blood Pressure, and Mood. Front Public Health, 5, 222. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00222

van Dixhoorn, J.V. (2008). Whole-body breathing. Biofeedback, 36,54–58. https://www.euronet.nl/users/dixhoorn/L.513.pdf

van Dixhoorn, J.V. (2021). Functioneel ademen-Adem-en ontspannings oefeningen voor gevorderden. Amersfoort: Uiteveriy Van Dixhoorn. https://www.bol.com/nl/nl/p/functioneel-ademen/9300000132165255/

Watso, J. C., Cuba, J.N., Boutwell, S.L, Moss, J…(2023). Acute nasal breathing lowers diastolic blood pressure and increases parasympathetic contributions to heart rate variability in young adults. American Journal of Physiology Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology.

325I(6), R797-R80. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.00148.2023

Wilson, V., Somers, K. & Peper, E. (2023). Differentiating Successful from Less Successful Males and Females in a Group Relaxation/Biofeedback Stress Management Program. Biofeedback, 51(3), 53–67. https://doi.org/10.5298/608570

[1] Correspondence should be addressed to:

Erik Peper, Ph.D., Institute for Holistic Health Studies, San Francisco State University, 1600 Holloway Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94132 Tel: 415 338 7683 Email: epeper@sfsu.edu web: www.biofeedbackhealth.org blog: www.peperperspective.com