Cellphones affects social communication, vision, breathing, and health: What to do!

Posted: September 4, 2024 Filed under: ADHD, attention, behavior, Breathing/respiration, cellphone, computer, digital devices, educationj, ergonomics, health, laptops, Neck and shoulder discomfort, posture, screen fatigue, self-healing, stress management, techstress, Uncategorized, vision, zoom fatigue | Tags: communication, myopia, pedestrian deaths, peripheral vision, text neck 7 CommentsAdapted from: Peper, E. & Harvey, R. (2024). Cell phones affects social communication, vision, breathing, and mental and physical health: What to do! TownsendLetter-The Examiner of Alternative Medicine,September 15, 2024. https://townsendletter.com/smartphone-affects-social-communication-vision-breathing-and-mental-and-physical-health-what-to-do/

Abstract

Smartphones are an indispensable part of our lives. Unfortunately too much of a ‘good thing’ regarding technology can work against us, leading to overuse, which in turn influences physical, mental and emotional development among current ‘Generation Z’ and ‘Millennial’ users (e.g., born 1997-2012, and 1981-1996, respectively). Compared to older technology users, Generation Z report more mental and physical health problems. Categories of mental health include attentional deficits, feelings of depression, anxiety social isolation and even suicidal thoughts, as along with physical health complaints such as sore neck and shoulders, eyestrain and increase in myopia. Long duration of looking downward at a smartphone affects not only eyestrain and posture but it also affects breathing which burden overall health. The article provides evidence and practices so show how technology over use and slouching posture may cause a decrease in social interactions and increases in emotional/mental and physical health symptoms such as eyestrain, myopia, and body aches and pains. Suggestions and strategies are provided for reversing the deleterious effects of slouched posture and shallow breathing to promote health.

We are part of an uncontrolled social experiment

We, as technology users, are all part of a social experiment in which companies examine which technologies and content increase profits for their investors (Mason, Zamparo, Marini, & Ameen, 2022). Unlike University research investigations which have a duty to warn of risks associated with their projects, we as participants in ‘profit-focused’ experiments are seldom fully and transparently informed of the physical, behavioral and psychological risks (Abbasi, Jagaveeran, Goh, & Tariq, 2021; Bhargava, & Velasquez, 2021). During university research participants must be told in plain language about the risks associated with the project (Huh-Yoo & Rader, 2020; Resnik, 2021). In contrast for-profit technology companies make it possible to hurriedly ‘click through’ terms-of-service and end-user-license-agreements, ‘giving away’ our rights to privacy, then selling our information to the highest bidder (Crain, 2021; Fainmesser, Galeotti, & Momot, 2023; Quach et al., 2022; Yang, 2022).

Although some people remain ignorant and or indifferent (e.g., “I don’t know and I don’t care”) about the use of our ‘data,’ an unintended consequence of becoming ‘dependent’ on technology overuse includes the strain on our mental and physical health (Abusamak, Jaber & Alrawashdeh, 2022; Padney et al., 2020). We have adapted new technologies and patterns of information input without asking the extent to which there were negative side effects (Akulwar-Tajane, Parmar, Naik & Shah, 2020; Elsayed, 2021). As modern employment shifted from predominantly blue-collar physical labor to white collar information processing jobs, people began sitting more throughout the day. Workers tended to look down to read and type. ‘Immobilized’ sitting for hours of time has increased as people spend time working on a computer/laptop and looking down at smartphones (Park, Kim & Lee, 2020). The average person now sits in a mostly immobilized posture 10.4 hours/day and modern adolescents spent more than two thirds of their waking time sitting and often looking down at their smartphones (Blodgett, et al., 2024; Arundell et al., 2019).

Smartphones are an indispensable part of our lives and is changing the physical and mental emotional development especially of Generation Z who were born between 1997-2012 (Haidt, 2024). They are the social media and smartphone natives (Childers & Boatwright, 2021). The smartphone is their personal computer and the gateway to communication including texting, searching, video chats, social media (Hernandez-de-Menendez, Escobar Díaz, & Morales-Menendez, 2020; Nichols, 2020; Schenarts, 2020; Szymkowiak et al., 2021). It has 100,000 times the processing power of the computer used to land the first astronauts on the moon on July 20, 1969 according to University of Nottingham’s computer scientist Graham Kendal (Dockrill, 2020). More than one half of US teens spend on the average more than 7 hours on daily screen time that includes watching streaming videos, gaming, social media and texting and their attention span has decreased from 150 seconds in 2004 to an average of 44 seconds in 2021 (Duarte, F., 2023; Mark, 2022, p. 96).

For Generation Z, social media use is done predominantly with smartphones while looking down. It has increased mental health problems such as attentional deficits, depression, anxiety suicidal thoughts, social isolation as well as decreased physical health (Haidt, 2024; Braghieri et al., 2023; Orsolini, Longo & Volpe, 2023; Satılmış, Cengız, & Güngörmüş, 2023; Muchacka-Cymerman, 2022; Fiebert, Kistner, Gissendanner & DaSilva, 2021; Mohan et al., 2021; Goodwin et al., 2020).

The shift in communication from synchronous (face-to-face) to asynchronous (texting) has transformed communications and mental health as it allows communication while being insulated from the other’s reactions (Lewis, 2024). The digital connection instead of face-to-face connection by looking down at the smart phone also has decreased the opportunity connect with other people and create new social connections, with three typical hypotheses examining the extent to which digital technologies (a) displace/ replace; (b) compete/ interfere with; and/or, (c) complement/ enhance in-person activities and relationships (Kushlev & Leitao, 2020).

As described in detail by Jonathan Haidt (2024), in his book, The Anxious Generation, the smartphone and the addictive nature of social media combined with the reduction in exercise, unsupervised play and childhood independence was been identified as the major factors in the decrease in mental health in your people (Gupta, 2023). This article focuses less on distraction such as attentional deficits, or dependency leading to tolerance, withdrawal and cravings (e.g., addiction-like symptoms) and focuses more on ‘dysregulation’ of body awareness (posture and breathing changes) and social communication while people are engaged with technology (Nawaz,Bhowmik, Linden & Mitchell, 2024).

The excessive use of the smartphones is associated with a significant reduction of physical activity and movement leading to a so-called sedentarism or increases of sitting disease (Chandrasekaran & Ganesan, 2021; Nakshine, Thute, Khatib, & Sarkar, 2022). Unbeknown to the smartphone users their posture changes, as they looks down at their screen, may also affect their mental and physical health (Aliberti, Invernizzi, Scurati & D’lsanto, 2020).

(1) Explore how looking at your smartphone affects you (adapted from: Peper, Harvey, & Rosegard, 2024)

For a minute, sit in your normal slouched position and look at your smartphone while intensely reading the text or searching social media. For the next minute sit tall and bring the cell phone in front of you so you can look straight ahead at it. Again, look at your smartphone while intensely reading the text or searching social media.

Compare how the posture affects you. Most likely, your experience is similar to the findings from students in a classroom observational study. Almost all experienced a reduction in peripheral awareness and breathed more shallowly when they slouched while looking at their cellphone.

Decreased peripheral awareness and increased shallow breathing that affects physical and mental health and performance. The students reported looking down position reduces the opportunity of creating new social connections. Looking down my also increases the risk for depression along with reduced cognitive performance during class (Peper et al., 2017; Peper et al., 2018).

(2) Explore how posture affects eye contact (adapted from the exercise shared by Ronald Swatzyna, 2023)[2]

Walk around your neighborhood or through campus either looking downwards or straight ahead for 30 minutes while counting the number of eye contacts you make.

Most likely, when looking straight ahead and around versus slouched and looking down you had the same experience as Ronald Swatzyna (2023), Licensed Clinical Social Worker. He observed that when he walked a three-mile loop around the park in a poor posture with shoulders forward in a head down position, and then reversed direction and walked in good posture with the shoulders back and the head level, he would make about five times as many eye contacts with a good posture compared to the poor posture.

Anecdotal observations, often repeated by many educators, suggest before the omnipresent smartphone, students would look around and talk to each other before a university class began. Now, when Generation Z students enter an in-person class, they sit down, look down at their phone and tend not to interact with other students.

(3) Experience the effect of face-to-face in-person communication

During the first class meeting, ask students to put their cellphones away, meet with three or four other students for a few minutes, and share a positive experience that happened to them last week as well as what they would like to learn in the class. After a few minutes, ask them to report how their energy and mood changed.

In our observational class study with 24 junior and senior college students in the in-person class and 54 students in the online zoom class, almost all report that that their energy and positive mood increased after they interacted with each other. The effects were more beneficial for the in-person small group sharing than the online breakout groups sharing on Zoom as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Change in subjective energy and mood after sharing experiences synchronously in small groups either in-person or online.

Without direction of a guided exercise to increase social connections, students tend to stay within their ‘smartphone bubble’ while looking down (Bochicchio et al., 2022). As a result, they appear to be more challenged to meet and interact with other people face-to-face or by phone as is reflected in the survey data that Generation Z is dating much less and more lonely than the previous generations (Cox et al., 2023).

What to do:

- Put the smartphone away so that you do not see it in social settings such as during meals or classes. This means that other people can be present with you and the activity of eating or learning.

- Do not permit smartphones in the classroom including universities unless it is required for a class assignment.

- In classrooms and in the corporate world, create activities that demands face-to-face synchronous communication.

- Unplug from the audio programs when walking and explore with your eyes what is going on around you.

(4) Looking down increases risk of injury and death

Looking down at a close screen reduces peripheral awareness and there by increases the risk of accidents and pedestrian deaths. Pedestrian deaths are up 69% since 2011 (Cova, 2024) and have consistently increased since the introduction of the iPhone in 2007 as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Increase in pedestrian death since the introduction of the iphone (data plotted from https://www.iihs.org/topics/fatality-statistics/detail/pedestrians)

In addition, the increase use of mobile phones is also associated with hand and wrist pain from overuse and with serious injuries such as falls and texting while driving due to lack of peripheral awareness. McLaughlin et al (2023) reports an increase in hand and wrist injuries as well serious injuries related to distracted behaviors, such as falls and texting while driving. The highest phone related injuries (lacerations) as reported from the 2011 to 2020 emergency room visits were people in the age range from 11–20 years followed by 21–30 years.

What to do:

- Do not walk while looking at your smartphone. Attend to the environment around you.

- Unplug from the audio podcasts when walking and explore with your eyes what is going on around you.

- Sit or stop walking when answering the smartphone to reduce the probability of an accident.

- For more pragmatic suggestions, see the book, TechStress: How Technology is Hijacking Our Lives, Strategies for Coping, and Pragmatic Ergonomics, by Peper, Harvey and Faass (2020).

(5) Looking at screens increases the risk of myopia

Looking at a near screen for long periods of time increases the risk of myopia (near sightedness) which means that distant vision is more blurry. Myopia has increased as children predominantly use computers or, smartphones with smaller screen at shorter distances. By predominantly focusing on nearby screens without allowing the eye to relax remodels the eyes structure. Consequently, myopia has increase in the U.S. from 25 percent in the early 1970s to nearly 42 percent three decades later (OHSU, 2022).

Looking only at nearby screens, our eyes converge and the ciliary muscles around the lens contract and remain contracted until the person looks at the far distance. The less opportunity there is to allow the eyes to look at distant vision, the more myopia occurs. in Singapore 80 per cent of young people aged 18 or below have nearsightedness and 20 % of the young people have high myopia as compared to 10 years ago (Singapore National Eye Centre, 2024). The increase in myopia is a significant concern since high myopia is associated with an increased risk of vision loss due to cataract, glaucoma, and myopic macular degeneration (MMD). MMD is rapidly increasing and one of the leading causes of blindness in East Asia that has one of the highest myopia rates in the world (Sankaridurg et al., 2021).

What to do:

- Every 20 minutes stop looking at the screen and look at the far distance to relax the eyes for 20 seconds.

- Do not allow young children access to cellphones or screens. Let them explore and play in nature where they naturally alternate looking at far and near objects.

- Implement the guided eye regenerating practices descrubed in the article, Resolve eyestrain and screen fatigue, by Peper (2021).

- Read Meir Schneider’s (2016) book, Vision for Life, for suggestions how to maintain and improve vision.

(6) Looking down increases tech neck discomfort

Looking down at the phone while standing or sitting strains the neck and shoulder muscles because of the prolonged forward head posture as illustrated in the YouTube video, Tech Stress Symptoms and Causes (DeWitt, 2018). Using a smartphone while standing or walking causes a significant increase in thoracic kyphosis and trunk (Betsch et al., 2021). When the head is erect, the muscle of the neck balance a weight of about 10 to 12 pounds or, approximately 5 kilograms; however, when the head is forward at 60 degrees looking at your cell phone the forces on the muscles are about 60 pound or more than 25 kilograms, as illustrated in Figure 4 (Hansraj, 2014).

Figure 4. The head forward position puts as much as sixty pounds of pressure on the neck muscles and spine (by permission from Dr. Kenneth Hansraj, 2014).

This process is graphically illustrated in the YouTube video, Text Neck Symptoms and Causes Video, produced by Veritas Health (2020).

What to do:

- Keep the phone in front of you so that you do not slouch down by having your elbow support on the table.

- Every ten minutes stretch, look up and roll your shoulders backwards.

- Wear a posture feedback device such as the UpRight Go 2 to remind you when you slouch to change posture and activity (Peper et al., 2019; Stuart, Godfrey & Mancini, 2022).

- Take Alexander Technique lessons to improve your posture (Cacciatore, Johnson, & Cohen, 2020; AmAT, 2024; STAT, 2024).

(7) Looking down increases negative memory recall and depression

In our previous research, Peper et al. (2017) have found that recalling hopeless, helpless, powerless, and defeated memories is easier when sitting in a slouched position than in an upright position. Recalling positive memories is much easier when sitting upright and looking slightly upward than sitting slouched position. If attempting to recall positive memories the brain has to work hard as indicated by an significantly higher amplitudes of beta2, beta3, and beta4 EEG (i.e., electroencephalograph) when sitting slouched then when sitting upright (Tsai et al., 2016).

Not only does the postural position affect memory recall, it also affects mental math under time-pressure performance. When students sit in a slouched position, they report that is much more difficult to do mental math (serial 7ths) than when in the upright position (Peper et al., 2018). The effect of posture is most powerful for the 70% of students who reported that they blanked out on exams, were anxious, or worried about class performance or math. For the 30% who reported no performance anxiety, posture had no significant effect. When students become aware of slouching thought posture feedback and then interrupt their slouching by sitting up, they report an increase in concentration, attention and school performance (Peper et al., 2024).

How we move and walk also affects our subjective energy. In most cases, when people sit for a long time, they report feeling more fatigue; however, if participants interrupt sitting with short movement practices they report becoming less fatigue and improved cognition (Wennberg et al., 2016). The change in subjective energy and mood depends upon the type of movement practice. Peper & Lin (2012) reported that when students were asked to walk in a slow slouching pattern looking down versus to walk quickly while skipping and looking up, they reported that skipping significantly increased their subjective energy and mood while the slouch walking decreased their energy. More importantly, student who had reported that they felt depressed during the last two years had their energy decrease significantly more when walking very slowly while slouched than those who did not report experiencing depression. Regardless of their self-reported history of depression, when students skipped, they all reported an increase in energy (Peper & Lin, 2012; Miragall et al., 2020).

What to do:

- Walk with a quick step while looking up and around.

- Wear a posture feedback device such as the UpRight Go 2 to remind you when you slouch to change posture and activity (Peper et al., 2019; Roggio et al., 2021).

- When sitting put a small pillow in the mid back so that you can sit more erect (for more suggestions, see the article by Peper et al., 2017a, Posture and mood: Implications and applications to therapy).

- Place photo and other objects that you like to look a slightly higher on your wall so that you automatically look up.

(8) Shallow breathing increases the risk for anxiety

When slouching we automatically tend to breathe slightly faster and more shallowly. This breathing pattern increases the risk for anxiety since it tends to decrease pCO2 (Feinstein et al., 2022; Meuret, Rosenfield, Millard & Ritz, 2023; Paulus, 2013; Smits et al., 2022; Van den Bergh et al., 2013). Sitting slouched also tends to inhibit abdominal expansion during the inhalation because the waist is constricted by clothing or a belt –sometimes labeled as ‘designer jean syndrome’ and may increase abdominal symptoms such as acid reflux and irritable bowel symptoms (Engeln & Zola, 2021; Peper et al., 2016; Peper et al., 2020). When students learn diaphragmatic breathing and practice diaphragmatic breathing whenever they shallow breathe or hold their breath, they report a significant decrease in anxiety, abdominal symptoms and even menstrual cramps (Haghighat et al., 2020; Peper et al., 2022; Peper et al., 2023).

What to do:

- Loosen your belt and waist constriction when sitting so that the abdomen can expand.

- Learn and practice effortless diaphragmatic breathing to reduce anxiety.

Conclusion

There are many topics related to postural health and technology overuse that were addressed in this article. Some topics are beyond the scope of the article, and therefore seen as limitations. These relate to diagnosis and treatment of attentional deficits, or dependency leading to tolerance, withdrawal and cravings (e.g., addiction-like symptoms), or of modeling relationships between factors that contribute to the increasing epidemic of mental and physical illness associated with smartphone use and social media, such as hypotheses examining the extent to which digital technologies (a) displace/ replace; (b) compete/ interfere with; and/or, (c) complement/ enhance in-person activities and relationships. Typical pharmaceutical ‘treat-the-symptom’ approaches for addressing ‘tech stress’ related to technology overuse includes prescribing ‘anxiolytics, pain-killers and muscle relaxants’ (Kazeminasab et al., 2022; Kim, Seo, Abdi, & Huh, 2020). Although not usually included in diagnosis and treatment strategies, suggesting improving posture and breathing practices can significantly affect mental and physical health. By changing posture and breathing patterns, individuals may have the option to optimize their health and well-being.

See the book, TechStress-How Technology is Hijacking our Lives, Strategies for Coping and Pragmatic Ergonomics by Erik Peper, Richard Harvey and Nancy Faass. Available from: https://www.amazon.com/Beyond-Ergonomics-Prevent-Fatigue-Burnout/dp/158394768X/

Explore the following blogs for more background and useful suggestions

References

Abbasi, G. A., Jagaveeran, M., Goh, Y. N., & Tariq, B. (2021). The impact of type of content use on smartphone addiction and academic performance: Physical activity as moderator. Technology in Society, 64, 101521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101521

Abusamak, M., Jaber, H. M., & Alrawashdeh, H. M. (2022). The effect of lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic on digital eye strain symptoms among the general population: a cross-sectional survey. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 895517. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.895517

Akulwar-Tajane, I., Parmar, K. K., Naik, P. H., & Shah, A. V. (2020). Rethinking screen time during COVID-19: impact on psychological well-being in physiotherapy students. Int J Clin Exp Med Res, 4(4), 201-216. https://doi.org/10.26855/ijcemr.2020.10.014

Aliberti, S., Invernizzi, P. L., Scurati, R., & D’Isanto, T. (2020). Posture and skeletal muscle disorders of the neck due to the use of smartphones. Journal of Human Sport and Exercise , 15 (3proc), S586-S598. https://www.jhse.ua.es/article/view/2020-v15-n3-proc-posture-skeletal-muscle-disorders-neck-smartpho; https://air.unimi.it/retrieve/handle/2434/774436/1588570/HSE%20-%20Posture%20and%20skeletal%20muscle%20disorders.pdf

AmSAT. (2024). American Society for the Alexander Technique. Accessed July 27, 2024. https://alexandertechniqueusa.org/

Arundell, L., Salmon, J., Koorts, H. et al. (2019). Exploring when and how adolescents sit: cross-sectional analysis of activPAL-measured patterns of daily sitting time, bouts and breaks. BMC Public Health 19, 653. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6960-5

Bhargava, V. R., & Velasquez, M. (2021). Ethics of the attention economy: The problem of social media addiction. Business Ethics Quarterly, 31(3), 321-359. https://doi.org/10.1017/beq.2020.32

Betsch, M., Kalbhen, K., Michalik, R., Schenker, H., Gatz, M., Quack, V., Siebers, H., Wild, M., & Migliorini, F. (2021). The influence of smartphone use on spinal posture – A laboratory study. Gait Posture, 85, 298-303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2021.02.018

Blodgett, J.M., Ahmadi, M.N., Atkin, A.J., Chastin, S., Chan, H-W., Suorsa, K., Bakker, E.A., Hettiarcachchi, P., Johansson, P.J., Sherar,L. B., Rangul, V., Pulsford, R.M…. (2024). ProPASS Collaboration , Device-measured physical activity and cardiometabolic health: the Prospective Physical Activity, Sitting, and Sleep (ProPASS) consortium, European Heart Journal, 45(6) 458–471, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad717

Bochicchio, V., Keith, K., Montero, I., Scandurra, C., & Winsler, A. (2022). Digital media inhibit self-regulatory private speech use in preschool children: The “digital bubble effect”. Cognitive Development, 62, 101180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogdev.2022.101180

Braghieri, L., Levy, R., & Makarin, A. (2022). Social Media and Mental Health (July 28, 2022). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3919760 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3919760

Cacciatore, T. W., Johnson, P. M., & Cohen, R. G. (2020). Potential mechanisms of the Alexander technique: Toward a comprehensive neurophysiological model. Kinesiology Review, 9(3), 199-213. https://doi.org/10.1123/kr.2020-0026

Chandrasekaran, B., & Ganesan, T. B. (2021). Sedentarism and chronic disease risk in COVID 19 lockdown–a scoping review. Scottish Medical Journal, 66(1), 3-10. https://doi.org/10.1177/0036933020946336

Childers, C., & Boatwright, B. (2021). Do digital natives recognize digital influence? Generational differences and understanding of social media influencers. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 42(4), 425-442. https://doi.org/10.1080/10641734.2020.1830893

Cox, D.A., Hammond, K.E., & Gray, K. (2023). Generation Z and the Transformation of American Adolescence: How Gen Z’s Formative Experiences Shape Its Politics, Priorities, and Future. Survey Center of American Life, November 23, 2023. Accessed July 4, 2024. https://www.americansurveycenter.org/research/generation-z-and-the-transformation-of-american-adolescence-how-gen-zs-formative-experiences-shape-its-politics-priorities-and-future/

Crain, M. (2021). Profit over privacy: How surveillance advertising conquered the internet. U of Minnesota Press. https://www.amazon.com/Profit-over-Privacy-Surveillance-Advertising/dp/1517905044

Cova, E. (2024). Pedestrian fatalities at historic high. Smart Growth America (data from U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT). Accessed July 2, 2024. https://smartgrowthamerica.org/pedestrian-fatalities-at-historic-high/

Duarte, F. (2023). Average Screen Time for Teens (2024). Exploding Topics. Accessed July 5, 2024. https://explodingtopics.com/blog/screen-time-for-teens#average

DeWitt, D. (2018). How Does Text Neck Cause Pain? Spine-Health October 26, 2018. Accessed July 5, 2024. https://www.spine-health.com/conditions/neck-pain/how-does-text-neck-cause-pain

Dockrill, P. (2020). Your laptop charger is more powerful than Apollo11’s computer, says apple developer. Science Alert, Janural 12, 2020. Accessed July 4, 2024. https://www.sciencealert.com/apollo-11-s-computer-was-less-powerful-than-a-usb-c-charger-programmer-discovers

Elsayed, W. (2021). Covid-19 pandemic and its impact on increasing the risks of children’s addiction to electronic games from a social work perspective. Heliyon, 7(12). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08503

Engeln, R., & Zola, A. (2021). These boots weren’t made for walking: gendered discrepancies in wearing painful, restricting, or distracting clothing. Sex roles, 85(7), 463-480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-021-01230-9

Fainmesser, I. P., Galeotti, A., & Momot, R. (2023). Digital privacy. Management Science, 69(6), 3157-3173. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2022.4513

Feinstein, J. S., Gould, D., & Khalsa, S. S. (2022). Amygdala-driven apnea and the chemoreceptive origin of anxiety. Biological psychology, 170, 108305. https://10.1016/j.biopsycho.2022.108305

Fiebert, I., Kistner, F., Gissendanner, C., & DaSilva, C. (2021). Text neck: An adverse postural phenomenon. Work, 69(4), 1261-1270. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-213547

Goodwin, R. D., Weinberger, A. H., Kim, J. H., Wu. M., & Galea, S. (2020). Trends in anxiety among adults in the United States, 2008–2018: Rapid increases among young adults. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 130, 441–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.08.014

Gupta, N. (2023). Impact of smartphone overuse on health and well-being: review and recommendations for life-technology balance. Journal of Applied Sciences and Clinical Practice, 4(1), 4-12. https://doi.org/10.4103/jascp.jascp_40_22

Haghighat, F., Moradi, R., Rezaie, M., Yarahmadi, N., & Ghaffarnejad, F. (2020). Added Value of Diaphragm Myofascial Release on Forward Head Posture and Chest Expansion in Patients with Neck Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Research Square. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-53279/v1

Haidt, J. (2024). The Anxious generation: How the great rewiring of childhood is causing an epidemic of mental illness. New York: Penguin Press. https://www.anxiousgeneration.com/book

Hansraj, K.K. (2014). Assessment of stresses in the cervical spine caused by posture and position of the head. Surg Technol Int. 25, 277-279. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25393825/

Hernandez-de-Menendez, M., Escobar Díaz, C. A., & Morales-Menendez, R. (2020). Educational experiences with Generation Z. International Journal on Interactive Design and Manufacturing (IJIDeM), 14(3), 847-859. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12008-020-00674-9

Huh-Yoo, J., & Rader, E. (2020). It’s the Wild, Wild West: Lessons learned from IRB members’ risk perceptions toward digital research data. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 4(CSCW1), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1145/3392868

IIHS (2024). Fatality Facts 2022Pedestrians. The Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS). Accessed July 2, 2024. https://www.iihs.org/topics/fatality-statistics/detail/pedestrians

Kazeminasab, S., Nejadghaderi, S. A., Amiri, P., Pourfathi, H., Araj-Khodaei, M., Sullman, M. J., … & Safiri, S. (2022). Neck pain: global epidemiology, trends and risk factors. BMC musculoskeletal disorders, 23, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-021-04957-4

Kim, K. H., Seo, H. J., Abdi, S., & Huh, B. (2020). All about pain pharmacology: what pain physicians should know. The Korean journal of pain, 33(2), 108-120. https://doi.org/10.3344/kjp.2020.33.2.108

Kushlev, K., & Leitao, M. R. (2020). The effects of smartphones on well-being: Theoretical integration and research agenda. Current opinion in psychology, 36, 77-82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.05.001

Lewis, H.R. (2024). Mechanical intelligence and counterfeit humanity. Harvard Magazine, 126(6), 38-40. https://www.harvardmagazine.com/2024/07/harry-lewis-computers-humanity#google_vignette

Mark, G. (2023). Attention Span: A Groundbreaking Way to Restore Balance, Happiness and Productivity. Toronto, Canada: Hanover Square Press. https://www.amazon.com/Attention-Span-Finding-Fighting-Distraction-ebook/dp/B09XBJ29W9

Mason, M. C., Zamparo, G., Marini, A., & Ameen, N. (2022). Glued to your phone? Generation Z’s smartphone addiction and online compulsive buying. Computers in Human Behavior, 136, 107404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107404

McLaughlin, W.M., Cravez, E., Caruana, D.L., Wilhelm, C., Modrak, M., & Gardner, E.C. (2023). An Epidemiological Study of Cell Phone-Related Injuries of the Hand and Wrist Reported in United States Emergency Departments From 2011 to 2020. J Hand Surg Glob, 5(2),184-188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsg.2022.11.009

Meuret, A. E., Rosenfield, D., Millard, M. M., & Ritz, T. (2023). Biofeedback Training to Increase Pco2 in Asthma With Elevated Anxiety: A One-Stop Treatment of Both Conditions?. Psychosomatic medicine, 85(5), 440-448. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000001188

Miragall, M., Borrego, A., Cebolla, A., Etchemendy, E., Navarro-Siurana, J., Llorens, R., … & Baños, R. M. (2020). Effect of an upright (vs. stooped) posture on interpretation bias, imagery, and emotions. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 68, 101560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2020.101560

Mohan, A., Sen, P., Shah, C., Jain, E., & Jain, S. (2021). Prevalence and risk factor assessment of digital eye strain among children using online e-learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: Digital eye strain among kids (DESK study-1). Indian journal of ophthalmology, 69(1), 140-144. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijo.IJO_2535_20

Muchacka-Cymerman, A. (2022). ‘I wonder why sometimes I feel so angry’ The associations between academic burnout, Facebook intrusion, phubbing, and aggressive behaviours during pandemic Covid 19. Polish Psychological Bulletin, 53(4). https://doi.org/10.24425/ppb.2022.143376

Nakshine, V. S., Thute, P., Khatib, M. N., & Sarkar, B. (2022). Increased screen time as a cause of declining physical, psychological health, and sleep patterns: a literary review. Cureus, 14(10). https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.30051

Nawaz, S., Bhowmik, J., Linden, T., & Mitchell, M. (2024). Validation of a modified problematic use of mobile phones scale to examine problematic smartphone use and dependence. Heliyon, 10(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e24832

Nicholas, A. J. (2020). Preferred learning methods of generation Z. Faculty and Staff – Articles & Papers. Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. Salve Regina University. https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/fac_staff_pub/74

OHSU. (2022). Myopia on the rise, especially among children. Casey Eye Institute. Oregan Health and Science University. Accessed July 7, 2024. https://www.ohsu.edu/casey-eye-institute/myopia-rise-especially-among-children

Orsolini, L., Longo, G., & Volpe, U. (2023). The mediatory role of the boredom and loneliness dimensions in the development of problematic internet use. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 4446. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054446

Pandey, R., Gaur, S., Kumar, R., Kotwal, N., & Kumar, S. (2020). Curse of the technology-computer related musculoskeletal disorders and vision syndrome: a study. International Journal of Research in Medical Sciences, 8(2), 661. https://doi.org/10.18203/2320-6012.ijrms20200253

Park, J. C., Kim, S., & Lee, H. (2020). Effect of work-related smartphone use after work on job burnout: Moderating effect of social support and organizational politics. Computers in human behavior, 105, 106194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.106194

Paulus, M.P. (2013). The breathing conundrum-interoceptive sensitivity and anxiety. Depress Anxiety.30(4), 315-20. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22076

Peper, E. (2021). Resolve eyestrain and screen fatigue. Well Being Journal, 30(1), 24-28. https://wellbeingjournal.com/resolve-eyestrain-and-screen-fatigue/

Peper, E., Booiman, A., Lin, I-M, Harvey, R., & Mitose, J. (2016). Abdominal SEMG Feedback for Diaphragmatic Breathing: A Methodological Note. Biofeedback. 44(1), 42-49. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-44.1.03

Peper, E., Chen, S., Heinz, N. & Harvey, R. (2023). Hope for menstrual cramps (dysmenorrhea) with breathing. Biofeedback, 51(2), 44–51. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-51.2.04

Peper, E., Harvey, R., Cuellar, Y., & Membrila, C. (2022). Reduce anxiety. NeuroRegulation, 9(2), 91–97. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.9.2.91

Peper, E., Harvey, R. & Faass, N. (2020). TechStress: How Technology is Hijacking Our Lives, Strategies for Coping, and Pragmatic Ergonomics. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books. https://www.amazon.com/Beyond-Ergonomics-Prevent-Fatigue-Burnout/dp/158394768X

Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Mason, L. (2019). “Don’t slouch!” Improve health with posture feedback. Townsend Letter-The Examiner of Alternative Medicine, 436, 58-61. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/337424599_Don%27t_slouch_Improve_health_with_posture_feedback

Peper, E., Harvey, R., Mason, L., & Lin, I.-M. (2018). Do better in math: How your body posture may change stereotype threat response. NeuroRegulation, 5(2), 67–74. http://dx.doi.org/10.15540/nr.5.2.67

Peper, E., Harvey, R. & Rosegard, E. (2024). Increase attention, concentration and school performance with posture feedback. Biofeedback, 52(2). https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-52.02.07

Peper, E. & Lin, I-M. (2012). Increase or decrease depression-How body postures influence your energy level. Biofeedback, 40 (3), 126-130. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-40.3.01

Peper, E., Lin, I-M, & Harvey, R. (2017a). Posture and mood: Implications and applications to therapy. Biofeedback, 35(2), 42-48. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-45.2.03

Peper, E., Lin, I-M., Harvey, R., & Perez, J. (2017). How posture affects memory recall and mood. Biofeedback.45 (2), 36-41. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-45.2.01

Peper, E., Mason, L., Harvey, R., Wolski, L, & Torres, J. (2020). Can acid reflux be reduced by breathing? Townsend Letters-The Examiner of Alternative Medicine, 445/446, 44-47. https://www.townsendletter.com/article/445-6-acid-reflux-reduced-by-breathing/

Quach, S., Thaichon, P., Martin, K. D., Weaven, S., & Palmatier, R. W. (2022). Digital technologies: tensions in privacy and data. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 50(6), 1299-1323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-022-00845-y

Resnik, D. B. (2021). Standards of evidence for institutional review board decision-making. Accountability in research, 28(7), 428-455. https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2020.1855149

Roggio, F., Ravalli, S., Maugeri, G., Bianco, A., Palma, A., Di Rosa, M., & Musumeci, G. (2021). Technological advancements in the analysis of human motion and posture management through digital devices. World journal of orthopedics, 12(7), 467. https://doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v12.i7.467

Sankaridurg, P., Tahhan, N., Kandel, H., Naduvilath, T., Zou, H., Frick,K.D., Marmamula, S., Friedman, D.S., Lamoureux, e. Keeffe, J. Walline, J.J., Fricke, T.R., Kovai, V., & Resnikoff, S. (2021) IMI Impact of Myopia. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci, 62(5), 2. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.62.5.2

Satılmış, S. E., Cengız, R., & Güngörmüş, H. A. (2023). The relationship between university students’ perception of boredom in leisure time and internet addiction during social isolation process. Bağımlılık Dergisi, 24(2), 164-173. https://doi.org/10.51982/bagimli.1137559

Schenarts, P. J. (2020). Now arriving: surgical trainees from generation Z. Journal of surgical education, 77(2), 246-253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2019.09.004

Schneider, M. (2016). Vision for life. Ten Steps to Natural Eyesight Improvement. Berkeley: North Atlantic books. https://www.amazon.com/Vision-Life-Revised-Eyesight-Improvement/dp/1623170087

Singapore National Eye Centre. (2024). Severe myopia cases among children in Singapore almost doubled in past decade. CAN. Accessed July 4, 2024. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/singapore/myopia-children-cases-almost-double-glasses-eye-checks-4250266

Smits, J. A., Monfils, M. H., Otto, M. W., Telch, M. J., Shumake, J., Feinstein, J. S., … & Exposure Therapy Consortium. (2022). CO2 reactivity as a biomarker of exposure-based therapy non-response: study protocol. BMC psychiatry, 22(1), 831. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-04478-x

STAT (2024). The society of teachers of the Alexander Technique. Assessed July 27, 2024. https://alexandertechnique.co.uk/

Stuart, S., Godfrey, A., & Mancini, M. (2022). Staying UpRight in Parkinson’s disease: A pilot study of a novel wearable postural intervention. Gait & Posture, 91, 86-93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2021.09.202

Swatzyna, R. (2023). Personal communications.

Szymkowiak, A., Melović, B., Dabić, M., Jeganathan, K., & Kundi, G. S. (2021). Information technology and Gen Z: The role of teachers, the internet, and technology in the education of young people. Technology in Society, 65, 101565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101565

Tsai, H. Y., Peper, E., & Lin, I. M.*(2016). EEG patterns under positive/negative body postures and emotion recall tasks. NeuroRegulation, 3(1), 23-27. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.3.1.23

Van den Bergh, O., Zaman, J., Bresseleers, J., Verhamme, P., Van Diest, I. (2013). Anxiety, pCO2 and cerebral blood flow, International Journal of Psychophysiology, 89 (1), 72-77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2013.05.011

Veritas Health. (2020). Text Neck Symptoms and Causes Video. YouTube video, accessed August 29, 2024. https://www.spine-health.com/conditions/neck-pain/how-does-text-neck-cause-pain?source=YT

Wennberg, P., Boraxbekk, C., Wheeler, M., et al. (2016). Acute effects of breaking up prolonged sitting on fatigue and cognition: a pilot study. BMJ Open, 6, e009630. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009630

Yang, K. H. (2022). Selling consumer data for profit: Optimal market-segmentation design and its consequences. American Economic Review, 112(4), 1364-1393. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles/pdf/doi/10.1257/aer.20210616

[1] Correspondence should be addressed to: Erik Peper, Ph.D., Institute for Holistic Health Studies, Department of Recreation, Parks, Tourism and Holistic Health, San Francisco State University, 1600 Holloway Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94132 Email: epeper@sfsu.edu; web: www.biofeedbackhealth.org; blog: www.peperperspective.com

[2] I thank Ronald Swatzyna (2023), Licensed Clinical Social Worker for sharing this exercise with me. He discovered that a difference in the number of eye contacts depending how he walked. When he walked a 3.1 mile loop around the park in a poor posture- shoulders forward, head down position- and then reversed direction and walked in good posture with the shoulders back and the head level, that that he make about 5 times as many eye contacts with good posture compared to the poor posture. He observed that he make about five times as many eye contacts with good posture as compared to the poor posture.

Are you encouraging your child to get into accidents or even blind when growing up?

Posted: May 12, 2021 Filed under: ADHD, behavior, computer, education, ergonomics, Evolutionary perspective, Exercise/movement, laptops, Neck and shoulder discomfort, posture, screen fatigue, Uncategorized, vision | Tags: glaucoma, myopia, nearsightedness, palming 6 CommentsErik Peper and Meir Schneider

Adapted in part from: TechStress-How Technology is Hijacking our Lives, Strategies for Coping and Pragmatic Ergonomics by Erik Peper, Richard Harvey and Nancy Faass

As a young child I laid on the couch and I read one book after the other. Hours would pass as I was drawn into the stories. By the age of 12 I was so nearsighted that I had to wear glasses. When my son started to learn to read, I asked him to look away at the far distance after reading a page. Even today at age 34, he continues this habit of looking away for a moment at the distance after reading or writing a page. He is a voracious reader and a novelist of speculative fiction. His vision is perfect. –Erik Peper

How come people in preliterate, hunting and gatherer, and agricultural societies tend to have better vision and very low rates of nearsightedness (Cordain et al, 2003)? The same appear true for people today who spent much of their childhood outdoors as compared to those who predominantly stay indoors. On the other hand, how come 85% of teenagers in Singapore are myopic (neasighted) and how come in the United States myopia rate have increased for children from 25% in the 1970s to 42% in 2000s (Bressler, 2020; Min, 2019)?

Why should you worry that your child may become nearsighted since it is easy correct with contacts or glasses? Sadly, in numerous cases, children with compromised vision and who have difficulty reading the blackboard may be labeled disruptive or having learning disability. The vision problems can only be corrected if the parents are aware of the vision problem (see https://www.covd.org/page/symptoms for symptoms that may be related to vision problems). In addition, glasses may be stigmatizing and children may not want to wear glasses because of vanity or the fear of being bullied.

The recent epidemic of near sightedness is paritally a result of disrespecting our evolutionary survival patterns that allowed us to survive and thrive. Throughout human history, people continuously alternated by looking nearby and at the distance. When looking up close, the extraocular muscles contract to converge the eyes and the ciliary muscles around the lens contract to increase the curvature of the lens so that the scene is in focus on the retina — this muscle tension creates near visual stress.

The shift from alternating between far and near vision to predominantly near vision and immobility

Figure 2. The traditional culture of Hdzabe men in Tanzania returning from a hunt. Notice how upright they walk and look at the far distance as compared to young people today who slouch and look predominantly at nearby screens.

Experience the effect of near visual stress.

Bring your arm in front of you and point your thumb up. Look at your thumb on the stretched out arm. Keep focusing on the thumb and slow bring the thumb four inches from your nose. Keep focusing on the thumb for a half minute. Drop the arm to the side, and look outside at the far distance.

What did you experience? Almost everyone reports feeling tension in the eyes and a sense of pressure inside around and behind their eyes. When looking at the distance, the tension slowly dissipates. For some the tension is released immediately while for others it may take many minutes before the tension disappears especially if one is older. Many adults experience that after working at the computer, their distant vision is more fuzzy and that it takes a while to return to normal clarity.

When the eyes focus at the distance, the ciliary muscles around lens relaxes so that the lens can flatten and the extra ocular muscles relax so that the eyes can diverge and objects in the distance are in focus. Healthy vision is the alternation between near and far focus– an automatic process by which the muscles of the eyes tightening and relax/regenerate.

Use develops structure and structure limits use

If we predominantly look at nearby surfaces, we increase near visual stress and the risk of developing myopia. As children grow, the use of their eyes will change the shape of the eyeball so that the muscles will have to contract less to keep the visual object into focus. If the eyes predominantly look at near objects, books, cellphones, tablets, toys, and walls in a room where there is little opportunity to look at the far distance, the eye ball will elongate and the child will more likely become near sighted. Over the last thirty year and escalated during COVID’s reside-in-place policies, children spent more and more time indoors while looking at screens and nearby walls in their rooms. Predominantly focusing on nearby objects starts even earlier as parents provide screens to baby and toddlers to distract and entertain them. The constant near vision remodels the shape of eye and the child will likely develop near sightedness.

Health risks of sightedness and focusing predominantly upon nearby objects

- Increased risk of get into an accident as we have reduced peripheral vision. In earlier times if you were walking in jungle, you would not survive without being aware of your peripheral vision. Any small visual change could indicate the possible presence food or predator, friend or foe. Now we focus predominantly centrally and are less aware of our periphery. Observe how your peripheral awareness decreases when you bring your nose to the screen to see more clearly. When outside and focusing close up the risk of accidents (tripping, being hit by cars, bumping into people and objects) significantly increases as shown in figure 3 and illustrated in the video clip.

Pedestrian accidents (head forward with loss of peripheral vision)

Figure 3. Injuries caused by cell phone use per year since the introduction of the smartphone (graphic from Peper, Harvey and Faass,2020; data source: Povolatskly et al., 2020).

- Myopia increases the risk of eye disorder. The risk for glaucoma, one the leading causes of blindness, is doubled (Susanna, De Moraes, Cioffi, & Ritch, R. 2015). The excessive tension around the eyes and ciliary muscles around the lens can interfere with the outflow of the excess fluids of the aqueous humour through the schlemm canal and may compromise the production of the aqueous humour fluid. These canals are complex vascular structures that maintains fluid pressure balance within the anterior segment of the eye. When the normal outflow is hindered it would contribute to elevated intraocular pressure and create high tension glaucoma (Andrés-Guerrero, García-Feijoo, & Konstas, 2017). Myopia also increases the risk for retinal detachment and tears, macular degeneration and cataract. (Williams & Hammond, 2019).

By learning to relax the muscles around the lens, eye and face and sensing a feeling of soft eyes, the restriction around the schlemm canals is reduced and the fluids can drain out easier and is one possible approach to reverse glaucoma (Dada et al., 2018; Peper, Pelletier & Tandy, 1979).

- Increase in neck and upper back compression when the person cranes their head forward or looks down while reading books/articles, looking at a cellphone or a laptop screen, This often results in an increase of back, neck and shoulder pain as well as headaches (Harvey, Peper, Booiman, Heredia Cedillo, & Villagomez, 2018; Hansraj, 2014).

- Decrease in subjective energy and increase in helpless, hopeless, powerless and defeated thoughts when the person habitually looks down in a slouched position (Peper, Booiman, Lin, & Harvey, 2016; Peper, Lin, Harvey, & Perez, 2017).

WHAT CAN YOU DO?

The solutions are remarkable simple. Respect your evolutionary background and allow your eyes to spontaneously alternate between looking at near and far objects while being upright (Schneider, 2016; Peper, 2021; Peper, Harvey & Faass, 2020).

For yourself and your child

- Let children play outside so that they automatically look far and near.

- When teaching children to read have them look at the distance at the end of every paragraph or page to relax the eyes.

- Limit screen time and alternate with outdoor activities

- Every 15 to 20 minutes take a vision break when reading or watching screens. Get up, wiggle around, move your neck and shoulders, and look out the window at the far distance.

- When looking at digital screens, look away every few minutes. As you look away, close your eyes for a moment and as you are exhaling gently open your eyes.

- Practice palming and relaxing the eyes. For detailed guidance and instruction see the YouTube video by Meir Schneider.

Create healthy eye programs in schools and work

- Arrange 30 minute lesson plans and in between each lesson plan take a vision and movement breaks. Have children get up from their desks and move around. If possible have them look out the window or go outside and describe the furthest object they can see such as the shape of clouds, roof line or details of the top of trees.

- Teach young children as they are learning reading and math to look away at the distance after reading a paragraph or finishing a math problem.

- Teach palming for children.

- During recess have students play games that integrate coordination with vision such as ball games.

- Episodically, have students close their eyes, breathe diaphragmatically and then as they exhale slowly open their eyes and look for a moment at the world with sleepy/dreamy eyes.

- Whenever using screen use every opportunity to look away at the distance and for a moment close your eyes and relax your neck and shoulders.

BOOKS TO OPTIMIZE VISION AND TRANSFORM TECHSTRESS INTO TECHHEALTH

Vision for Life, Revised Edition: Ten Steps to Natural Eyesight Improvement by Meir Schneider.

YOUTUBE PRESENTATION, Transforming Tech Stress into Tech Health.

ADDITIONAL BLOGS THAT FOCUS ON RESOLVING EYES STREAN AND TECHSTRESS

REFERENCES

Bressler, N.M. (2020). Reducing the Progression of Myopia. JAMA, 324(6), 558–559.

Peper, E. (2021). Resolve eyestrain and screen fatigue. Well Being Journal, 30(1), 24-28.

Schneider, M. (2019). YouTube video Free Webinar by Meir Schneider: May 6, 2019.

Williams, K., & Hammond, C. (2019). High myopia and its risks. Community eye health, 32(105), 5–6.

Are LED screens harming you?

Posted: June 18, 2016 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: blue light, dry eyes, health, myopia, stress management, vision, visual stress 7 Comments

Sleep has become more and more elusive since checking my cellphone in bed.

Ouch, my eyes hurt when I flipped the light switch on and the room was flooded with light.

After working on my computer screen, the world looked blurry.

At night, the intense blue white LED headlights blinded me unlike the normal incandescent headlights.

My eyes become irritated and dry after looking at the computer screen.

More and more people are myopic and wear contacts lenses.

Many older people are suffering from macular degeneration and may go blind.

Migraine pain significantly decreased when a person looks at soft green light and significantly increased when looking at bright white light (Hamzelou, 2016). .

Vision problems are becoming more and more frequent. More and more children are near sighted and need vision correction while macular degeneration–a major cause of blindness for older adults–is becoming more prevalent (Fan et al, 2004: Lee et al, 2002;

Faber et al, 2015; Schneider, 2016). As we look ahead into the future, a new epidemic is starting to roll in—compromised vision. Major culprits include:

- Near visual stress caused by looking intensely at surfaces or objects one to two feet away such as computer screens, tablets and cell phones inhibits the eyes to relax and increases near sightedness (Fernández-Montero et al, 2015).

- Absence of visual relaxation and shifting focus from close to far distance. This ongoing increased focus decreases blinking rate and exhausts the eyes.

- Absence of looking at the green coloring of vegetation that historically predominated our visual environment–a color that is relaxing for the eyes and body especially when looked from a distance.

- Sleep suppression and disturbance caused working/reading/watching the LED screens (computer screen, tablet, cell phone, TV, or e-readers such as Amazon Kindle Fire or any tablet) before going to bed (Tosini et al, 2016). The blue light component produced by the LED screen suppresses melatonin production and interferes with sleep onset.

- Extreme variation in light intensity damages the retina. The pupil which normally contracts to protect the retina as light intensity increases is too slow to respond to the sharp changes in light intensity. This is very similar to looking at the sun during a solar eclipse without eye protection. The intense sun light literally will burn/damage the retina and can induce blindness.

- Harmful exposure of the blue light component of the LED screens or light bulbs may increase inflammation and damage to the macular area of the retina. This is often labeled as toxic blue light with a wavelength of 415-455nm (Roberts, 2011).

The light that illuminates our visual world and how our world conditions us to use our eyes is totally different from how our eyes evolved over the last million years. Although our present life is far removed from our evolutionary past, our evolutionary past is embedded within us and controls much of our biology and psychology. Consider how we used to live for millennia.

I look up and see vultures circling. It is not too far. I rapidly walk in the direction. I have a sense where the possible food source could be. As I walk I alternately look at the distance and close at the ground and scrubs. I continually scan the environment. Although there are shadows where I look the light is of somewhat similar intensity unless I look directly at the sun. While doing tasks I focus ahead where I will plant my feet or at my food or objects my hands are manipulating. I alternately shift from foreground to background. As I look in the distance and the many green plants, my eyes relax.

In the morning, the natural light wakes me. The bright morning light wakes me, I stretch and move. As the day progresses the light becomes brighter, then at sunset the light becomes softer and the yellow orange red spectrum predominates.

Whether we lived twenty thousand years ago in caves or communities, or two hundred years ago in small houses in cities or farms, sunlight illuminated our world. The sun light warm us, is necessary for vitamin D production and controls our biological circadian rhythms. The sun light and sometime the moonlight provided the only source of illumination. Generally, we woke up with the light and went to sleep when the light disappeared. For thousands of years human beings have attempted to bring light to the darkness to reduce danger. Light produced by fire for cooking and protection against predators, and some form of oil lamps to provide minimal illumination. These light sources were predominantly red and yellow. It was only with the application of gas and electrical illumination that lights could become brighter. Usually the light transitions were slow and gentle which allowed the ciliary muscles of the iris to contract thus making the pupil much smaller and reduce the influx of light to the retina and thereby protected the retina from excessive fluctuating light intensity.

Exposure to light in the evening or night is very recent in evolutionary terms. For hundreds of thousands of years the night was dark as we hid away in caves to avoid predators. And, the darkness allowed our eyes to regenerate. Only in the last few thousand years did candles or oil lamps with their yellow orange light illuminate the dark. The fear of the dark is primordial– in the dark we were the prey. During those prehistoric times, our fear was reduced by huddling together for warmth and safety as we slept. These days, while sleeping we turn on a night light to feel safe or allow us to see in case we have to get up. For many of us, darkness still feels unsafe since as babies the fear was amplified as we slept alone in a crib without feeling the tactile signals of safety provided by direct human contact.

Now most people live and work indoors and we are no longer exposed to direct or indirect sun light. Instead, we can illuminate our work and personal world twenty four hours a day and total darkness is elusive. Even when I close the shades in my bedroom, the blinking light of the smartphone charger, and the headlights of the cars passing by penetrate the darkness. While entering a dark room, we throw the switch and the room instantly is flooded with light. This instant transition to full light pains the eyes as the eyes struggle to adapt by closing the iris. The retina was already impacted. This may be one of the covert factors that contribute to the development of macular degeneration?

Historically, we mainly looked at reflected light and almost never at the light source such as the sun. Now we predominantly look directly into the light source of the light bulb, TV, computer, laptop, e-readers and smart phone screens. We are unaware that the light we see is not the same type of light as natural sun light. It still appears white; however, it is an illusion. We live most of our lives indoors illuminated by incandescent, fluorescent and LED light sources. These lights have limited spectrums and may lead to light malnutrition and blue light poisoning.

The most recent change has been the use of light-emitting diode (LED)–an electronic semiconductor device that emits light when an electric current passes through it. This is the process of flat TV, computer, tablet, cellphone screens and LED light bulbs. These bulbs are highly energy efficient and thus are being installed everywhere but are a significant health hazard which is described superbly and in detail at the end of the article by architect and lighting expert Milena Simeonova, www.lighting4health.com

What can you do to protect your eyes and improve your vision?

Use your eyes as much as possible as we did through most of our evolutionary history which means:

- Read and implement the practices described in the superb book, Vision for Life: Ten Steps to Natural Eyesight Improvement., by Meir Schneider which has helped thousands of people maintain and improve their vision.

- Take many vision breaks and look away from your screen. If possible look at the far distance and green plants and trees to relax your eyes.

- Do NOT use LED e-reader; instead, use e-readers that can be read by reflective light such as Amazon Kindle Paperwhite eReader.

- Block direct intense light sources. Arrange them so that they illuminate the walls and you only see gradual light gradients of reflective light.

- Install warm LED light (particularly for evening time) which have much less damaging blue light.

- Install software such on your computer that automatically adjusts your screen’s color-temperature depending on the time of day and your location. Thus, when the sun sets, the colors of the screen change and become more yellow, orange, and red thereby reducing the transmitted blue light I(Robinson, 2015).

–Mac, Windows, and Linux computers: f.flux is a free app (https://justgetflux.com/).

–Android or iPhones: install a “blue light filter” app.

–For additional free apps to protect your eyes from too bright screen light at night, see: http://sometips.wersjatestowa.eu/how-to-protect- eyes-from-too-bright-screen-light-especially-at-night/

- Spent as much time as possible looking at far distances with soft green light backgrounds.

- Encourage children to play outside and do not allow young children to entertain themselves with screen time especially as the eyes are developing (see my 2011 blog: Screens will hurt your children).

- Limit screen time and increase movement and physical activity time.

- Blink and blink more and relax your eyes. When visually stressed, blinking is inhibited because you do not want to miss the tiger who potentially could attack you. That is our evolutionary response pattern; however, there are no life threatening tigers around, thus allow yourself to blink. Do the following exercise to experience how your eyes change depending how you open and close them.

How to increase stressed dry eyes:

Sit comfortably and let your eyes be closed and breathe. Then exhale and when ready to inhale, inhale rapidly into your upper chest while opening your eyes wide as if fearful and frightened. Repeat a second time and then keep holding your eyes wide open as if looking for danger.

Observe what happened. Most people report that the front of their eyes felt slightly cooler as if a slight breeze was going over the cornea, and the eyes (cornea) are drier.

How to increase relaxed moist eyes:

Sit comfortably and let your eyes be closed and breathe. While breathing allow your abdomen to expand when you inhale and gently constrict when you exhale as if the lungs are a balloon in your abdomen. When ready, inhale while keeping the shoulders relaxed and the eyes still closed and then gently begin to exhale and very slowly and softly open your eyes slightly while looking down peacefully and content. Just as a mother may look down upon their baby in her arms with a slight smile. Repeat a second time and gently open your eyes slightly as the exhalation has started and is softly flowing.

Observe what happened. Most people report that their eyes became softer, more relaxed with increased of the beginning of a tear beginning to fill the front of the cornea.

You have a choice! You can mobilize health or continue to risk your vision. Adapt the precautionary principle and act now. See the in-depth description of the potential harm of LED lights described by architect and lighting designer Milena Simeonova who helps people stay healthy by applying natural light patterns inside buildings (www.lighting4health.com).

LED Lighting and Blue Light Hazard

By Milena Simeonova, Architect, MS in Lighting LRC, IES, LC

When TVs, computers, tablets, and mobile devices are used in the evening hours, the cool LED light emanating from the screens, shifts the body onset for melatonin production, pushing back our bed time by 1-1.5hr or later. You may think that’s not bad, if you have to study for exams or deliver this final project. Think twice when disrupting the circadian system and depriving your body of normal sleep hours. It is a recipe for initiating illness. Watch the superb TEDxCambridge 2011 lecture, A Sleep Epidemic, by Charles Szeisler, PhD, MD from Harvard Medical School (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p4UxLpoNCxU)

Science has discovered that Blue light suppresses melatonin (the sleep hormone), and can either regulate or deregulate our circadian system (bio-clock), disrupting our sleep during the night, and lowering our performance during the day. It affects our normal body function that is synchronized with the daylight-night cycle as shown in Figure 1. If this cycle is disrupted, poor health follows in the form of heart disease, cancer, depression, obesity, etc. Figure 1: Double plot (2 x 24 hours.) of typical daily rhythms of body temperature, melatonin, cortisol, and alertness in humans for a natural 24-hour light/dark cycle. Our circadian system regulates the body’s endocrine and hormonal production; these functions are synchronized with the cycle of day-night in Nature. A healthy body starts producing melatonin at about 7pm and melatonin (sleep hormone) peaks at 12am-3am. From: van Bommel, W. J. M. & van den Beld, G. J. (2003). Lighting for work: visual and biological effects. Philips Lighting. p.7.

Figure 1: Double plot (2 x 24 hours.) of typical daily rhythms of body temperature, melatonin, cortisol, and alertness in humans for a natural 24-hour light/dark cycle. Our circadian system regulates the body’s endocrine and hormonal production; these functions are synchronized with the cycle of day-night in Nature. A healthy body starts producing melatonin at about 7pm and melatonin (sleep hormone) peaks at 12am-3am. From: van Bommel, W. J. M. & van den Beld, G. J. (2003). Lighting for work: visual and biological effects. Philips Lighting. p.7.

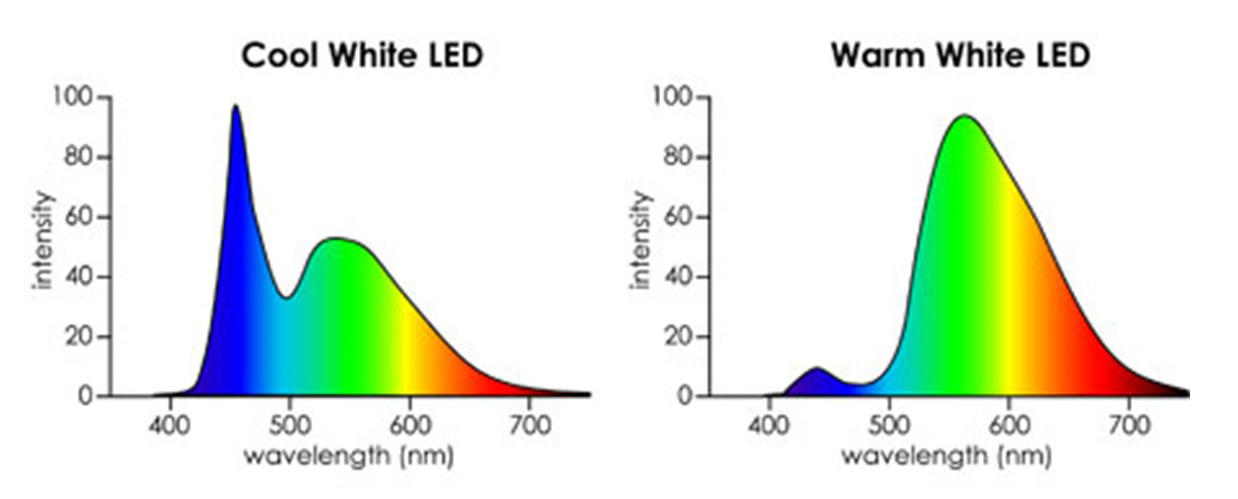

What about the change from incandescent to LED light in the room? With LED lighting, the Blue Light Hazard has increased, particularly from high output cool LED light fixtures with clear lens. LED lighting is produced from a Blue LED chip combined with warm phosphors; think of it as a Blue spike with a warm tail (see Figure 2). The trouble with the Blue spike is that it peaks at about 430nm-440nm, and science has found that light below the 440nm wavelength frequency, results in macular degeneration in older people (Roberts, 2001). For more detail, see Chemistry Professor Joan E. Roberts from Fordham University presentation, How does the spectrum of light affects the human health? http://www.be-exchange.org/media/ByLightofDay_Presentation.compressed-1.pdf

Figure 2: Actual measurements with LED Spectrometer of color tuning LED light source. On the left is cool LED light with big Blue light spike (big output of Blue light) and a small warm tail of phosphors. On the right is a warm LED light with decreased Blue Light output. From: Floroiu, V.A. (2015). The ABCs of truly energy efficient LED lighting. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/abcs-truly-energy-efficient-led-lighting-victor-adrian-floroiu

Figure 2: Actual measurements with LED Spectrometer of color tuning LED light source. On the left is cool LED light with big Blue light spike (big output of Blue light) and a small warm tail of phosphors. On the right is a warm LED light with decreased Blue Light output. From: Floroiu, V.A. (2015). The ABCs of truly energy efficient LED lighting. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/abcs-truly-energy-efficient-led-lighting-victor-adrian-floroiu

The health risk is even greater for younger eyes (ages 20-40) because the older eyes are more protected with the natural aging of the eye lens that is thickening and yellowing, which in turn scatters Blue light and protects the eye retina from energy absorption. In contrast, the younger eyes allow 2-3 times more transmittance of Blue light, resulting in higher ocular oxidation and greater risk of retinal photo-degradation (Hammond et al, 2014). Thus in a room lighted with cool LED lighting (above 4000K), there will be a lot of Blue light that can be damaging to the eye retina. This is particularly true, when eyes have direct exposure to high output LED fixtures that are non-dimmable.

This is just the tip of the iceberg, as LED lighting has other potential health issues, such as flicker that is barely discernible at full light output, but increases when dimming the lights; or the spatial flicker resulting from the gazing along bright LED lights in a room; or the multi-fringed or multiple shadows of a single object, projected from the multiple LED chips in a fixture, that is unnatural and not observed in Nature. It is important to choose LED lighting that maintains human health. (See: https://www.greenbiz.com/blog/2010/01/21/pendulum-energy-efficiency-and-importance-human-factors)

Interactive and dynamic lighting are also on the rise, and will have unintended effects on the Autonomous Nervous System (ANS) with over-stimulating the Sympathetic neural system, disrupting the balance of arousal and rest that is needed for people to stay healthy.

How can we protect our health? For now, use 4000K LED light for daytime, use warmer lights 3000K and below for the evening hours; use as night light warm or amber color light; get blue light filter apps for your screens; dim your room lights in the evening, use LED lights that have a diffuse lens, shade to soften the light beam; aim LED lights to the ceiling or wall surfaces, and away from the eyes; and best of all – get plenty of healthy daylight during the day.

The mechanism of Blue Light Hazard (BLH). Blue light also known as “cool” light, has a high frequency of oscillation, high excitation of its light particles or photons. The “blue” photons have smaller mass, and carry significantly higher energy than the red light photons, blue photons can create oxidative photodegradation in ocular tissues, and suppress effectively melatonin and disrupt sleep even at very low level.

The colors of a rainbow illustrate the visible Light Spectrum. Each color represents a specific light frequency, vibrational energy, wavelength, and excitation. Light wavelength can be for the benefit or to the detriment of human health, depending on the dosage or length of exposure to the particular wavelength of light; and depending on the timing or when exposured to light.

Visible light spectrum ranges from 360 nm to 760 nm wavelengths; with Red light (620-750 nm) having the longer wavelength and smaller excitation, and Blue light (420-490 nm) having a short wavelength with high frequency (more pulses/time).

Contact information for Milena Simeonova, Architect, MS in Lighting LRC, IES, LC

1658 8th Avenue, San Francisco, California 94122, USA

T: 415-684-2770 Light4Health, www.lighting4health.com

References:

Hamzelou, J. (2016). Green light eases migraine pain – but we don’t know why. New Scientist. 19 May 2016. https://www.newscientist.com/article/2089062-green-light-found-to-ease-the-pain-of-migraine/

Faber, C., Jehs, T., Juel, H. B., Singh, A., Falk, M. K., Sørensen, T. L., & Nissen, M. H. (2015). Early and exudative age‐related macular degeneration is associated with increased plasma levels of soluble TNF receptor II. Acta ophthalmologica, 93(3), 242-247.

Fernández-Montero, A., Olmo-Jimenez, J. M., Olmo, N., Bes-Rastrollo, M., Moreno-Galarraga, L., Moreno-Montañés, J., & Martínez-González, M. A. (2015). The impact of computer use in myopia progression: A cohort study in Spain. Preventive medicine, 71, 67-71.

Hammond, B. R., Johnson, B. A., & George, E. R. (2014). Oxidative photodegradation of ocular tissues: beneficial effects of filtering and exogenous antioxidants. Experimental eye research, 129, 135-150.

Roberts, D. (2011). Artificial Lighting and the Blue Light Hazard. Posted in: Daily Living. Retrieved June 18, 2016.

Roberts, J. E. (2001). Ocular phototoxicity. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology, 64(2), 136-143.

Robinson, M. (2015). This app has transformed my nighttime computer use. TechInsider, Oct. 28, 2015. http://www.techinsider.io/flux-review-2015-10

Schneider, M. (2016). Vision for Life: Ten Steps to Natural Eyesight Improvement. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books. ISBN-13: 978-1623170080