Reflections on the increase in Autism, ADHD, anxiety and depression: Part 2- Exposure to neurotoxins and ultra-processed foods

Posted: June 30, 2024 Filed under: ADHD, attention, behavior, CBT, digital devices, education, emotions, Evolutionary perspective, health, mindfulness, neurofeedback, Nutrition/diet, Uncategorized | Tags: ADHD, anxiety, depression, diet, glyphosate, herbicide, herbicites, mental-health, neurofeedback, pesticides, supplements', ultraprocessed foods, vitamins 4 CommentsAdapted from: Peper, E. & Shuford, J. (2024). Reflections on the increase in Autism, ADHD, anxiety and depression: Part 2- Exposure to neurotoxins and ultra-processed foods. NeuroRegulation, 11(2), 219–228. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.11.2.219

Look at your hand and remember that every cell in your body including your brain is constructed out the foods you ingested. If you ingested inferior foods (raw materials to be built your physical structure), then the structure can only be inferior. If you use superior foods, you have the opportunity to create a superior structure which provides the opportunity for superior functioning. -Erik Peper

Summary

Mental health symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), Autism, anxiety and depression have increased over the last 15 years. An additional risk factor that may affect mental and physical health is the foods we eat. Even though, our food may look and even taste the same as compared to 50 years ago, it contains herbicide and pesticide residues and often consist of ultra-processed foods. These foods (low in fiber, and high in sugar, animal fats and additives) are a significant part of the American diet and correlate with higher levels of inattention and hyperactivity in children with ADHD. Due to affluent malnutrition, many children are deficient in essential vitamins and minerals. We recommend that before beginning neurofeedback and behavioral treatments, diet and lifestyle are assessed (we call this Grandmother therapy assessment). If the diet appears low in organic foods and vegetable, high in ultra-processed foods and drinks, then nutritional deficiencies should be assessed. Then the next intervention step is to reduce the nutritional deficiencies and implement diet changes from ultra-processed foods to organic whole foods. Meta-analysis demonstrates that providing supplements such as Vitamin D, etc. and reducing simple carbohydrates and sugars and eating more vegetables, fruits and healthy fats during regular meals can ameliorate the symptoms and promote health.

The previous article and blog, Reflections on the increase in Autism, ADHD, anxiety and depression: Part 1-bonding, screen time, and circadian rhythms, pointed out how the changes in bonding, screen time and circadian rhythms affected physical and mental health (Peper, 2023a; Peper, 2023b). However, there are many additional factors including genetics that may contribute to the increase is ADHD, autism, anxiety, depression, allergies and autoimmune illnesses (Swatzyna et al., 2018). Genetics contribute to the risk of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD); since, family, twin, and adoption studies have reported that ADHD runs in families (Durukan et al., 2018; Faraone & Larsson, 2019). Genetics is in most cases a risk factor that may or may not be expressed. The concept underlying this blog is that genetics loads the gun and environment and behavior pulls the trigger as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Interaction between Genetics and Environment

The pandemic only escalated trends that already was occurring. For example, Bommersbach et al (2023) analyzed the national trends in mental health-related emergency department visits among USA youth, 2011-2021. They observed that in the USA, Over the last 10 years, the proportion of pediatric ED visits for mental health reasons has approximately doubled, including a 5-fold increase in suicide-related visits. The mental health-related emergency department visits increased an average of 8% per year while suicide related visits increased 23.1% per year. Similar trends have reported by Braghieri et al (2022) from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Mental health trends in the United States by age group in 2008–2019. The data come from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Reproduced with permission from Braghieri, Luca and Levy, Ro’ee and Makarin, Alexey, Social Media and Mental Health (July 28, 2022) https://ssrn.com/abstract=3919760 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3919760

The trends reported from this data shows an increase in mental health illnesses for young people ages 18-23 and 24-29 and no changes for the older groups which could be correlated with the release of the first iPhone 2G on June 29, 2007. Thus, the Covid 19 pandemic and social isolation were not THE CAUSE but an escalation of an ongoing trend. For the younger population, the cellphone has become the vehicle for personal communication and social connections, many young people communicate more with texting than in-person and spent hours on screens which impact sleep (Peper, 2023a). At the same time, there are many other concurrent factors that may contributed to increase of ADHD, autism, anxiety, depression, allergies and autoimmune illnesses.

Without ever signing an informed consent form, we all have participated in lifestyle and environmental changes that differ from that evolved through the process of evolutionary natural selection and promoted survival of the human species. Many of those changes in lifestyle are driven by demand for short-term corporate profits over long-term health of the population. As exemplified by the significant increase in vaping in young people as a covert strategy to increase smoking (CDC, 2023) or the marketing of ultra-processed foods (van Tulleken, 2023).

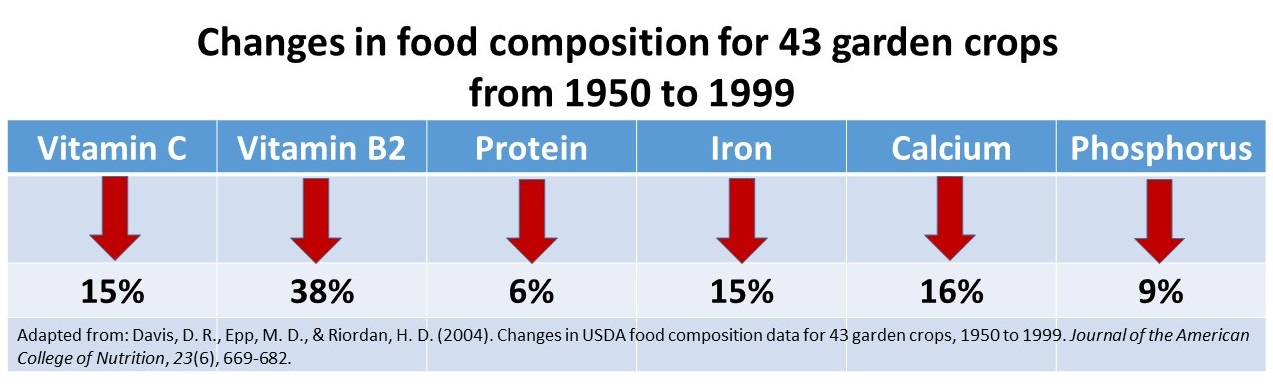

This post focusses how pesticides and herbicides (exposure to neurotoxins) and changes in our food negatively affects our health and well-being and is may be another contributor to the increase risk for developing ADHD, autism, anxiety and depression. Although our food may look and even taste the same compared to 50 years ago, it is now different–more herbicide and pesticide residues and is often ultra-processed. lt contains lower levels of nutrients and vitamins such as Vitamin C, Vitamin B2, Protein, Iron, Calcium and Phosphorus than 50 years ago (Davis et al, 2004; Fernandez-Cornejo et al., 2014). Non-organic foods as compared to organic foods may reduce longevity, fertility and survival after fasting (Chhabra et al., 2013).

Being poisoned by pesticide and herbicide residues in food

Almost all foods, except those labeled organic, are contaminated with pesticides and herbicides. The United States Department of Agriculture reported that “Pesticide use more than tripled between 1960 and 1981. Herbicide use increased more than tenfold (from 35 to 478 million pounds) as more U.S. farmers began to treat their fields with these chemicals” (Fernandez-Cornejo, et al., 2013, p 11). The increase in herbicides and pesticides is correlated with a significant deterioration of health in the United States (Swanson, et al., 2014 as illustrated in the following Figure 3.

Figure 3. Correlation between Disease Prevalence and Glyphosate Applications (reproduced with permission from Swanson et al., 2014.

Although correlation is not causation and similar relationships could be plotted by correlating consumption of ultra-refined foods, antibiotic use, decrease in physical activity, increase in computer, cellphone and social media use, etc.; nevertheless, it may suggest a causal relationship. Most pesticides and herbicides are neurotoxins and can accumulate in the person over time this could affect physical and mental health (Bjørling-Poulsen et al., 2008; Arab & Mostaflou, 2022). Even though the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has determined that the residual concentrations in foods are safe, their long-term safety has not been well established (Leoci & Ruberti, 2021). Other countries, especially those in which agribusiness has less power to affect legislation thorough lobbying, and utilize the research findings from studies not funded by agribusiness, have come to different conclusions…

For example, the USA allows much higher residues of pesticides such as, Round-Up, with a toxic ingredient glyphosate (0.7 parts per million) in foods than European countries (0.01 parts per million) (Wahab et al., 2022; EPA, 2023; European Commission, 2023) as is graphically illustrated in figure 4.

Figure 4: Percent of Crops Sprayed with Glyphosate and Allowable Glyphosate Levels in the USA versus the EU

The USA allows this higher exposure than the European Union even though about half of the human gut microbiota are vulnerable to glyphosate exposure (Puigbo et al., 2022). The negative effects most likely would be more harmful in a rapidly growing infant than for an adult. Most likely, some individuals are more vulnerable than others and are the “canary in mine.” They are the early indicators for possible low-level long-term harm. Research has shown that fetal exposure from the mother (gestational exposure) is associated with an increase in behaviors related to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorders and executive function in the child when they are 7 to 12 years old (Sagiv et al., 2021). Also, organophosphate exposure is correlated with ADHD prevalence in children (Bouchard et al., 2010). We hypothesize this exposure is one of the co-factors that have contributed to the decrease in mental health of adults 18 to 29 years.

At the same time as herbicides and pesticides acreage usage has increased, ultra-processed food have become a major part of the American diet (van Tulleken, 2023). Eating a diet high in ultra-processed foods, low in fiber, high sugar, animal fats and additives has been associated with higher levels of inattention and hyperactivity in children with ADHD; namely, high consumption of sugar, candy, cola beverages, and non-cola soft drinks and low consumption of fatty fish were also associated with a higher prevalence of ADHD diagnosis (Ríos-Hernández et al., 2017).

In international studies, less nutritional eating behaviors were observed in ADHD risk group as compared to the normal group (Ryu et al., 2022). Artificial food colors and additives are also a public health issue and appear to increase the risk of hyperactive behavior (Arnold et al., 2012). In a randomized double-blinded, placebo controlled trial 3 and 8/9 year old children had an increase in hyperactive behavior for those whose diet included extra additives (McCann et al., 2007). The risk may occur during fetal development since poor prenatal maternal is a critical factor in the infants neurodevelopment and is associated with an increased probability of developing ADHD and autism (Zhong et al., 2020; Mengying et al., 2016).

Poor nutrition even affects your unborn grandchild

Poor nutrition not only affects the mother and the developing fetus through epigenetic changes, it also impacts the developing eggs in the ovary of the fetus that can become the future granddaughter (Wilson, 2015). At birth, the baby has all of her eggs. Thus, there is a scientific basis for the old wives tale that curses may skip a generation. Providing maternal support is even more important since it affects the new born and the future grandchild. The risk may even begin a generation earlier since the grandmother’s poor nutrition as well as stress causes epigenetic changes in the fetus eggs. Thus 50% of the chromosomes of the grandchild were impacted epigenetically by the mother’s and grandmother’s dietary and health status .

Highly processed foods

Highly refined foods have been processed to remove many of their nutrients. These foods includes white bread, white rice, pasta, and sugary drinks and almost all the fast foods and snacks. These foods are low in fiber, vitamins, and minerals, and they are high in sugars, unhealthy fats, and calories. In addition, additives may have been added to maximize taste and mouth feel and implicitly encourage addiction to these foods. A diet high in refined sugars and carbohydrates increases the risk of diabetes and can worsen the symptoms of ADHD, autism, depression, anxiety and increase metabolic disease and diabetes (Woo et al., 2014; Lustig, 2021; van Tulleken, 2023). Del-Ponte et al. (2019) noted that a diet high in refined sugar and saturated fat increased the risk of symptoms of ADHD, whereas a healthy diet, characterized by high consumption of fruits and vegetables, would protect against the symptoms.

Most likely, a diet of highly refined foods may cause blood sugar to spike and crash, which can lead to mood swings, irritability, anxiety, depression and cognitive decline and often labeled as “hangryness” (the combination of anger and hunger) (Gomes et al., 2023; Barr et al., 2019). At the same time a Mediterranean diet improves depression significantly more than the befriending control group (Bayles et al., 2022). In addition, refined foods are low in essential vitamins and minerals as well as fiber. Not enough fiber can slow down digestion, affect the human biome, and makes it harder for the body to absorb nutrients. This can lead to nutrient deficiencies, which can contribute to the symptoms of ADHD, autism, depression, and anxiety. Foods do impact our mental and physical health as illustrated by foods that tend to reduce depression (LaChance & Ramsey, 2018; MacInerney et al., 2017). By providing appropriate micronutrients such as minerals (Iron, Magnesium Zinc), vitamins (B6, B12, B9 and D), Omega 3s (Phosphatidylserine) and changing our diet, ADHD symptoms can be ameliorated.

Many children with ADHD, anxiety, depression are low on essential vitamins and minerals. For example, low levels of Omega-3 fatty acids and vitamin D may be caused by eating ultra-refined foods, fast foods, and drinking soft drink. At the same time, the children are sitting more in indoors in front of the screen and thereby have lower sun exposure that is necessary for the vitamin D production.

“Because of lifestyle changes and sunscreen use, about 42% of Americans are deficient in vitamin D. Among children between 1 to 11 years old, an estimated 15% have vitamin D deficiency. And researchers have found that 17% of adolescents and 32% of young adults were deficient in vitamin D.” (Porto and Abu-Alreesh, 2022).

Reduced sun exposure is even more relevant for people of color (and older people); since, their darker skin (increased melanin) protects them from ultraviolet light damage but at the same time reduces the skins production of vitamin D. Northern Europeans were aware of the link between sun exposure and vitamin D production. To prevent rickets (a disease caused by vitamin D deficiency) and reduce upper respiratory tract infections the children were given a tablespoon of cod liver oil to swallow (Linday, 2010). Cod liver oil, although not always liked by children, is more nutritious than just taking a Vitamin D supplements. It is a whole food and a rich source of vitamin A and D as well as containing a variety of Omega 3 fatty acids (eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) (USDA, 2019).

Research studies suggest that ADHD can be ameliorated with nutrients, and herbs supplements (Henry & CNS, 2023). Table 1 summarizes some of the nutritional deficits observed and the reduction of ADHD symptoms when nutritional supplements were given (adapted from Henry, 2023; Henry & CNS, 2023).

| Nutritional deficits observed in people with ADHD | Decrease in ADHD symptoms with nutritional supplements |

| Vitamin D: In meta-analysis with a total number of 11,324 children, all eight trials reported significantly lower serum concentrations of 25(OH)D in patients diagnosed with ADHD compared to healthy controls. (Kotsi et al, 2019) | After 8 weeks children receiving vitamin D (50,000 IU/week) plus magnesium (6 mg/kg/day) showed a significant reduction in emotional problems as observed in a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial (Hemamy et al., 2021). |

| Iron: In meta-analysis lower serum ferritin was associated with ADHD in children (Wang et al., 2017) and the mean serum ferritin levels are lower in the children with ADHD than in the controls (Konofal et al., 2004). | After 12 weeks of supplementation with Iron (ferrous sulfate) in double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial, clinical trials symptoms of in children with ADHD as compared to controls were reduced (Tohidi et al., 2021; Pongpitakdamrong et all, 2022). |

| Omega 3’s: Children with ADHD are more likely to be deficient in omega 3’s than children without ADHD (Chang et al., 2017). | Adding Omega-3 supplements to their diet resulted in an improvement in hyperactivity, impulsivity, learning, reading and short term memory as compared to controls in 16 randomized controlled trials including 1514 children and young adults with ADHD (Derbyshire, 2017) |

| Magnesium: In meta-analysis, subjects with ADHD had lower serum magnesium levels compared with to their healthy controls (Effatpahah et al., 2019) | 8 weeks of supplementation with Vitamin D and magnesium caused a significant decrease in children with conduct problems, social problems, and anxiety/shy scores (Hemamy et al., 2020). |

| Vitamin B2, B6, B9 and B12deficiency has been found in many patients with Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder (Landaas et al, 2016; Unal et al., 2019). | Vitamin therapy appears to reduce symptoms of ADHD and ASD (Poudineh et al., 2023; Unal et al., 2019). An 8 weeks supplementing with Vitamin B6 and magnesium decreased hyperactivity and hyperemotivity/aggressiveness. When supplementation was stopped, clinical symptoms of the disease reappeared in few weeks (Mousain-Bosc et al., 2006). |

Table 1. Examples of vitamin and mineral deficiencies associated with symptoms of ADHD and supplementation to reduction of ADHD symptoms.

Supplementation of vitamins and minerals in many cases consisted of more than one single vitamin or mineral. For an in-depth analysis and presentation, see the superb webinar by Henry & CNS (2023): https://divcom-events.webex.com/recordingservice/sites/divcom-events/recording/e29cefcae6c1103bb7f3aa780efee435/playback? (Henry & CNS, 2023).

Whole foods are more than the sum of individual parts (the identified individual constituents/nutrients). The process of digestion is much more complicated than ingesting simple foods with added vitamins or minerals. Digestion is the interaction of many food components (many of which we have not identified) which interact and affect the human biome. A simple added nutrient can help; however, eating whole organic foods it most likely be healthier. For example, whole-wheat flour is much more nutritious. Whole wheat is rich in vitamins B-1, B-3, B-5, riboflavin, folate well as fiber while refined white flour has been bleached and stripped of fiber and nutrients to which some added vitamins and iron are added.

Recommendation

When working with clients, follow Talib’s principles as outlined in Part 1 by Peper (2023) which suggests that to improve health first remove the unnatural which in this case are the ultra-processed foods, simple carbohydrates, exposure to pesticides and herbicides (Taleb, 2014). The approach is beneficial for prevention and treatment. This recommendation to optimize health is both very simple and very challenging. The simple recommendation is to eat only organic foods and as much variety as possible as recommended by Professor Michael Pollan in his books, Omnivore’s Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals and Food Rules (Pollan, 2006; Pollan, 2011).

Do not eat foods that contain herbicides and pesticide residues or are ultra-processed. Although organic foods especially vegetable and fruits are often much more expensive, you have choice: You can pay more now to optimize health or pay later to treat disease. Be safe and not sorry. This recommendation is similar to the quote, “Let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food,” that has been attributed falsely since the 1970s to Hippocrates, the Greek founder of western medicine (5th Century, BC) (Cardenas, 2013).

There are many factors that interfere with implementing these suggestions; since, numerous people live in food deserts (no easy access to healthy unprocessed foods ) or food swamps (a plethora of fast food outlets) and 54 million Americans are food insecure (Ney, 2022). In addition, we and our parents have been programmed by the food industry advertising to eat the ultra- processed foods and may no longer know how to prepare healthy foods such as exemplified by a Mediterranean diet. Recent research by Bayles et al (2022) has shown that eating a Mediterranean diet improves depression significantly more than the befriending control group. In addition, highly processed foods and snacks are omnipresent, often addictive and more economical.

Remember that clients are individuals and almost all research findings are based upon group averages. Even when the data implies that a certain intervention is highly successful, there are always some participants for whom it is very beneficial and some for whom it is ineffective or even harmful. Thus, interventions need to be individualized for which there is usually only very limited data. In most cases, the original studies did not identify the characteristics of those who were highly successful or those who were unsuccessful. In addition, when working with specific individuals with ADHD, anxiety, depression, etc. there are multiple possible causes.

Before beginning specific clinical treatment such as neurofeedback and/or medication, we recommend the following:

- “Grandmother assessment” that includes and assessment of screen time, physical activity, outdoor sun exposure, sleep rhythm as outlined in Part 1 by Peper (2023). Then follow-up with a dietary assessment that investigates the prevalence of organic/non organic foods, ingestion of fast foods, ultra-processed foods, soft drinks, high simple carbohydrate and sugar, salty/sugary/fatty snacks, fruits, vegetables, and eating patterns (eating with family or by themselves in front of screens). Be sure to include an assessment of emotional reactivity and frequency of irritability and “hangryness”.

- If the assessment suggest low level of organic whole foods and predominance of ultra- refined foods, it may be possible that the person is deficient in vitamins and minerals. Recommend that the child is tested for the vitamin deficiencies. If vitamin deficiencies identified, recommend to supplement the diet with the necessary vitamins and mineral and encourage eating foods that naturally include these substances (Henry & CNS, 2023). If there is a high level of emotional reactivity and “hangryness,” a possible contributing factor could be hypoglycemic rebound from a high simple carbohydrate (sugar) intake or not eating breakfast combined with hyperventilation (Engel et al., 1947; Barr et al., 2019). Recommend eliminating simple carbohydrate breakfast and fast food snacks and substitute organic foods that include complex carbohydrates, protein, fats, vegetables and fruit. Be sure to eat breakfast.

- Implement “Grandmother Therapy”. Encourage the family and child to change their diet to eating a whide variety of organic foods (vegetables, fruits, some fish, meat and possibly dairy) and eliminate simple carbohydrates and sugars. This diet will tend to reduce nutritional deficits and may eliminate the need for supplements.

- Concurrent with the stabilization of the physiology begin psychophysiological treatment strategies such as neurofeedback biofeedback and cognitive behavior therapy.

Relevant blogs

Author Disclosure

Authors have no grants, financial interests, or conflicts to disclose.

References

Arnold, L, Lofthouse, N., & Hurt, E. (2012). Artificial food colors and attention-deficit/hyperactivity symptoms: conclusions to dye for. Neurotherapeutics, 9(3), 599-609. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-012-0133-x

Arab, A. & Mostafalou, S. (2022). Neurotoxicity of pesticides in the context of CNS chronic diseases. International Journal of Environmental Health Research, 32(12), 2718-2755. https://doi.org/10.1080/09603123.2021.1987396

Barr, E.A., Peper, E., & Swatzyna, R.J. (2019). Slouched Posture, Sleep Deprivation, and Mood Disorders: Interconnection and Modulation by Theta Brain Waves. NeuroRegulation, 6(4), 181–189. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.6.4.181

Bayes. J., Schloss, J., Sibbritt, D. (2022). The effect of a Mediterranean diet on the symptoms of depression in young males (the “AMMEND: A Mediterranean Diet in MEN with Depression” study): a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 116(2), 572-580. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqac106

Bjørling-Poulsen, M., Andersen, H.R. & Grandjean, P. Potential developmental neurotoxicity of pesticides used in Europe. Environ Health 7, 50 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-069X-7-50

Bommersbach, T.J., McKean, A.J., Olfson, M., Rhee, T.G. (2023). National Trends in Mental Health–Related Emergency Department Visits Among Youth, 2011-2020. JAMA, 329(17):1469–1477. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2023.4809

Bouchard, M.F., Bellinger, D.C., Wright, R.O., & Weisskopf, M.G. (2010). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and urinary metabolites of organophosphate pesticides. Pediatrics, 125(6), e1270-7. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-3058

Braghieri, L., Levy, R., & Makarin, A. (2022). Social Media and Mental Health (July 28, 2022). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3919760 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3919760

Cardenas, D. (2013). Let not thy food be confused with thy medicine: The Hippocratic misquotation. e-Spen Journal, 8(6), 3260-3262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnme.2013.10.002

CDC, (2023). Quick Facts on the Risks of E-cigarettes for Kids, Teens, and Young Adults. CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed September 23, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/Quick-Facts-on-the-Risks-of-E-cigarettes-for-Kids-Teens-and-Young-Adults.html

Chang, J.C., Su, K.P., Mondelli, V. et al. Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in Youths with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Clinical Trials and Biological Studies. Neuropsychopharmacol. 43, 534–545. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2017.160

Chhabra, R., Kolli, S., & Bauer, J.H. (2013). Organically Grown Food Provides Health Benefits to Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS ONE, 8(1): e52988. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0052988

Davis, D. R., Epp, M. D., & Riordan, H. D. (2004). Changes in USDA food composition data for 43 garden crops, 1950 to 1999. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 23(6), 669-682. https://doi.org/10.1080/07315724.2004.10719409

Derbyshire, E. (2017). Do Omega-3/6 Fatty Acids Have a Therapeutic Role in Children and Young People with ADHD? J Lipids. 6285218. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/6285218

Del-Ponte, B., Quinte, G.C., Cruz, S., Grellert, M., & Santos, I. S. Dietary patterns and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 252, 160-173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.04.061

Durukan, İ., Kara, K., Almbaideen, M., Karaman, D., & Gül, H. (2018). Alexithymia, depression and anxiety in parents of children with neurodevelopmental disorder: Comparative study of autistic disorder, pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified and attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics International, 60(3), 247–253. https://doi.org/10.1111/ped.13510

Effatpanah, M., Rezaei, M., Effatpanah, H., Effatpanah, Z., Varkaneh, H.K., Mousavi. S.M., Fatahi, S., Rinaldi, G., & Hashemi, R. (2019). Magnesium status and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res, 274, 228-234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.02.043

Engel, G.L., Ferris, E.B., & Logan, M. (1947). Hyperventilation; analysis of clinical symptomatology. Ann Intern Med, 27(5), 683-704. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-27-5-683

EPA. (2023). Glyphosate. United States Environmental Protection Agency. Accessed April 1, 2023. https://www.epa.gov/ingredients-used-pesticide-products/glyphosate

European Commission. (2023). EU legislation on MRLs.Food Safety. Assessed April 1, 2023. https://food.ec.europa.eu/plants/pesticides/maximum-residue-levels/eu-legislation-mrls_en#:~:text=A%20general%20default%20MRL%20of,e.g.%20babies%2C%20children%20and%20vegetarians

Faraone, S.V. & Larsson, H. (2019). Genetics of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Mol Psychiatry, 24(4), 562-575. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0070-0

Fernandez-Cornejo, J. Nehring, R, Osteen, C., Wechsler, S., Martin, A., & Vialou, A. (2014). Pesticide use in the U.S. Agriculture: 21 Selected Crops, 1960-2008. Economic Information Bulletin Number 123, United State Department of Agriculture. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/43854/46734_eib124.pdf

Gomes, G. N., Vidal, F. N., Khandpur. N., et al. (2023). Association Between Consumption of Ultraprocessed Foods and Cognitive Decline. JAMA Neurol, 80(2),142–150. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.4397

Hemamy, M., Heidari-Beni, M., Askari, G., Karahmadi, M., & Maracy, M. (2020). Effect of Vitamin D and Magnesium Supplementation on Behavior Problems in Children with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Int J Prev Med, 11(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_546_17

Henry, K. (2023). An Integrative Medicine Approach to ADHD. Rupa Health. Accessed September 30, 2023. https://www.rupahealth.com/post/an-integrative-medicine-approach-to-adhd

Henry, K. & CNS, L.A. (2023). Natural treatments for ADHD. Webinar Presentation by IntegrativePractitioner.com and sponsored by Rupa Health, June 6, 2023 https://divcom-events.webex.com/recordingservice/sites/divcom-events/recording/e29cefcae6c1103bb7f3aa780efee435/playback?

Hemamy, M., Pahlavani, N., Amanollahi, A. et al. (2021). The effect of vitamin D and magnesium supplementation on the mental health status of attention-deficit hyperactive children: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Pediatr, 21, 178. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-021-02631-1

Konofal, E., Lecendreux, M., Arnulf, I., & Mouren, M. (2004). Iron Deficiency in Children With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med, 158(12), 1113–1115. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.158.12.1113

Kotsi, E., Kotsi, E. & Perrea, D.N. (2019). Vitamin D levels in children and adolescents with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): a meta-analysis. ADHD Atten Def Hyp Disord, 11, 221–232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12402-018-0276-7

LaChance, L.R. & Ramsey, D. (2018). Antidepressant foods: An evidence-based nutrient profiling system for depression. World J Psychiatr, 8(3): 97-104. World J Psychiatr., 8(3): 97-104. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v8.i3.97

Landaas, E.T., Aarsland, T.I., Ulvik, A., Halmøy, A., Ueland. P.M., & Haavik, J. (20166). Vitamin levels in adults with ADHD. BJPsych Open, 2(6), 377-384. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjpo.bp.116.003491

Linday, L.A. (2010). Cod liver oil, young children, and upper respiratory tract infections. J Am Coll Nutr, 29(6), 559-62. https://doi.org/10.1080/07315724.2010.10719894

Leoci, R. & Ruberti, M. (2021) Pesticides: An Overview of the Current Health Problems of Their Use. Journal of Geoscience and Environment Protection, 9, 1-20. https://doi.org/10.4236/gep.2021.98001

Lustig, R.H. (2021). Metaboical: The lure and the lies of processed food, nutrition, and modern medicine. New York: Harper Wave. https://www.amazon.com/Metabolical-processed-poisons-people-planet/dp/1529350077

MacInerney, E. K., Swatzyna, R. J., Roark, A. J., Gonzalez, B. C., & Kozlowski, G. P. (2017). Breakfast choices influence brainwave activity: Single case study of a 12-year-old female. NeuroRegulation, 4(1), 56–62. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.4.1.56

McCann, D., Barrett, A., Cooper, A., Crumpler, D., Dalen, L., Grimshaw, K., et al. (2007). Food additives and hyperactive behavior in 3-year old and 8/9-year-old children in the community: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet, 370(9598), 1560-1567. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61306-3

Mengying, L.I, Fallin, A, D., Riley,A., Landa, R., Walker, S.O., Silverstein, M., Caruso, D., et al. (2016). The Association of Maternal Obesity and Diabetes With Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. Pediatrics, 137(2), e20152206. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-2206

Mousain-Bosc, M., Roche, M., Polge, A., Pradal-Prat, D., Rapin, J., & Bali, J.P. (2006). Improvement of neurobehavioral disorders in children supplemented with magnesium-vitamin B6. I. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorders. Magnes Res. 19(1), 46-52. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16846100/#:~:text=In%20almost%20all%20cases%20of,increase%20in%20Erc%2DMg%20values.

Ney, J. (2022). Food Deserts and Inequality. Social Policy Data Lab. Updated: Jan 24, 2022. Accessed September, 23, 2023. https://www.socialpolicylab.org/post/grow-your-blog-community

Peper, E. (2023a). Reflections on the increase in Autism, ADHD, anxiety and depression: Part 1-bonding, screen time, and circadian rhythms. the peperperspective July 2, 2023. Accessed august 8, 2024, https://peperperspective.com/2023/07/04/reflections-on-the-increase-in-autism-adhd-anxiety-and-depression-part-1-bonding-screen-time-and-circadian-rhythms/

Peper, E. (2023b). Reflections on the increase in Autism, ADHD, anxiety and depression: Part 1-bonding, screen time, and circadian rhythms. NeuroRegulation, 10(2), 134-138. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.10.2.134

Pollan, M. (2006). Omnivore’s Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals and Food Rules. New York Penguin Press. https://www.amazon.com/Omnivores-Dilemma-Natural-History-Meals/dp/1594200823/ref=tmm_hrd_swatch_0?_

Pollan, M. (2011). Food rules. New York Penguin Press. https://www.amazon.com/Food-Rules-Eaters-Michael-Pollan/dp/B00VSBILFG/ref=tmm_hrd_swatch_0?

Pongpitakdamrong, A., Chirdkiatgumchai, V., Ruangdaraganon, N., Roongpraiwan, R., Sirachainan, N., Soongprasit, M., & Udomsubpayakul, U. (2022). Effect of Iron Supplementation in Children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Iron Deficiency: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 43(2), 80-86., https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000000993

Porto, A. & Abu-Alreesh, S. (2022). Vitamin D for babies, children & adolescents. Health Living. Healthychildren.org. Accessed September 24, 2023. https://www.healthychildren.org/English/healthy-living/nutrition/Pages/vitamin-d-on-the-double.aspx#

Poudineh, M., Parvin, S., Omidali, M., Nikzad, F., Mohammadyari, F., Sadeghi Poor Ranjbar, F., F., Nanbakhsh, S., & Olangian-Tehrani, S. (2023). The Effects of Vitamin Therapy on ASD and ADHD: A Narrative Review. CNS & Neurological Disorders – Drug Targets (Formerly Current Drug Targets – CNS & Neurological Disorders), (22), 5, 2023, 711-735. https://doi.org/10.2174/1871527321666220517205813

Puigbò, P., Leino, L. I., Rainio, M. J., Saikkonen, K., Saloniemi, I., & Helander, M. (2022). Does Glyphosate Affect the Human Microbiota?. Life, 12(5), 707. https://doi.org/10.3390/life12050707

Ríos-Hernández, A., Alda, J.A., Farran-Codina, A., Ferreira-García, E., & Izquierdo-Pulido, M. (2017). The Mediterranean Diet and ADHD in Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics, 139(2):e20162027. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-2027

Ryu, S.A., Choi, Y.J., An, H., Kwon, H.J., Ha, M., Hong, Y.C., Hong, S.J., & Hwang, H.J. (2022). Associations between Dietary Intake and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) Scores by Repeated Measurements in School-Age Children. Nutrients, 14(14), 2919. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14142919

Sagiv, S.K., Kogut, K., Harley, K., Bradman, A., Morga, N., & Eskenazi, B. (2021). Gestational Exposure to Organophosphate Pesticides and Longitudinally Assessed Behaviors Related to Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Executive Function, American Journal of Epidemiology, 190(11), 2420–2431. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwab173

Swanson, N.L., Leu, A., Abrahamson, J., & Wallet, B. (2014). Genetically engineered crops, glyphosate and the deterioration of health in the United States of America. Journal of Organic Systems, 9(2), 6-17. https://www.organic-systems.org/journal/92/JOS_Volume-9_Number-2_Nov_2014-Swanson-et-al.pdf

Swatzyna, R. J., Boutros, N. N., Genovese, A. C., MacInerney, E. K., Roark, A. J., & Kozlowski, G. P. (2018). Electroencephalogram (EEG) for children with autism spectrum disorder: Evidential considerations for routine screening. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 28(5), 615–624. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-018-1225-x

Taleb, N. N. (2014). Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder (Incerto). New York: Random House Publishing Group. https://www.amazon.com/Antifragile-Things-That-Disorder-Incerto/dp/0812979680/ref=tmm_pap_swatch_0

Tohidi, S., Bidabadi, E., Khosousi, M.J., Amoukhteh, M., Kousha, M., Mashouf, P., Shahraki, T. (2021). Effects of Iron Supplementation on Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Children Treated with Methylphenidate. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci, 19(4), 712-720. https://doi.org/10.9758/cpn.2021.19.4.712

Unal, D. Çelebi, F., Bildik,H.N., Koyuncu, A., & Karahan, S. (2019). Vitamin B12 and haemoglobin levels may be related with ADHD symptoms: a study in Turkish children with ADHD, Psychiatry and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 29(4), 515-519. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750573.2018.1459005

USDA. (2019). Fish oil, cod liver. FoodData Central. USDA U.S> Department of Agriculture. Published 4/1/2019. Accessed September 24, 2024. https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/fdc-app.html#/food-details/173577/nutrients

Van Tulleken, C. (2023). Ultra-Processed People. The Science Behind Food That Isn’t Food. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. https://www.amazon.com/Ultra-Processed-People-Science-Behind-Food/dp/1324036729/ref=asc_df_1324036729/?

Wahab, S., Muzammil, K., Nasir, N., Khan, M.S., Ahmad, M.F., Khalid, M., Ahmad, W., Dawria, A., Reddy, L.K.V., & Busayli, A.M. (2022). Advancement and New Trends in Analysis of Pesticide Residues in Food: A Comprehensive Review. Plants (Basel), 11(9), 1106. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11091106

Wang. Y., Huang, L., Zhang, L., Qu, Y., & Mu, D. (2017). Iron Status in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One, 12(1):e0169145. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169145

Wilson, L. (2015). Mothers, beware: Your lifestyle choices will even affect your grandkids.

News Corp Australia Network. Accessed Jun 24, 2024. https://www.news.com.au/lifestyle/parenting/kids/mothers-beware-your-lifestyle-choices-will-even-affect-your-grandkids/news-story/3f326f457546cfb32af5c409f335fb56

Woo, H.D.,; Kim, D.W., Hong, Y.-S., Kim, Y.-M.,Seo, J.-H.,; Choe, B.M., Park, J.H.,; Kang, J.-W., Yoo, J.-H.,; Chueh, H.W., et al. (2014). Dietary Patterns in Children with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Nutrients, 6, 1539-1553. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu6041539

Zhong, C., Tessing, J., Lee, B.K., Lyall, K. Maternal Dietary Factors and the Risk of Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Systematic Review of Existing Evidence. Autism Res,13(10),1634-1658. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2402

Eat what grows in season

Posted: December 14, 2021 Filed under: health, Nutrition/diet, self-healing | Tags: food, herbicide, organic foods, pesticides Leave a commentAndrea Castillo and Erik Peper

We are what we eat. Our body is synthesized from the foods we eat. Creating the best conditions for a healthy body depends upon the foods we ingest as implied by the phrase, Let food be thy medicine, attributed to Hippocrates, the Greek founder of western medicine (Cardenas, 2013). The foods are the building blocks for growth and repair. Comparing our body to building a house, the building materials are the foods we eat, the architect’s plans are our genetic coding, the care taking of the house is our lifestyle and the weather that buffers the house is our stress reactions. If you build a house with top of the line materials and take care of it, it will last a life time or more. Although the analogy of a house to the body is not correct since a house cannot repair itself, it is a useful analogy since repair is an ongoing process to keep the house in good shape. Our body continuously repairs itself in the process of regeneration. Our health will be better when we eat organic foods that are in season since they have the most nutrients.

Organic foods have much lower levels of harmful herbicides and pesticides which are neurotoxins and harmful to our health (Baker et al., 2002; Barański, et al, 2014). Crops have been organically farmed have higher levels of vitamins and minerals which are essential for our health compared to crops that have been chemically fertilized (Peper, 2017),

Even seasonality appears to be a factor. Foods that are outdoor grown or harvested in their natural growing period for the region where it is produced, tend to have more flavor that foods that are grown out of season such as in green houses or picked prematurely thousands of miles away to allow shipping to the consumer. Compare the intense flavor of small strawberry picked in May from the plant grown in your back yard to the watery bland taste of the great looking strawberries bought in December.

The seasonality of food

It’s the middle of winter. The weather has cooled down, the days are shorter, and some nights feel particularly cozy. Maybe you crave a warm bowl of tomato soup so you go to the store, buy some beautiful organic tomatoes, and make yourself a warm meal. The soup is… good. But not great. It is a little bland even though you salted it and spiced it. You can’t quite put your finger on it, but it feels like it’s missing more tomato flavor. But why? You added plenty of tomatoes. You’re a good cook so it’s not like you messed up the recipe. It’s just—missing something.

That something could easily be seasonality. The beautiful, organic tomatoes purchased from the store in the middle of winter could not have been grown locally, outside. Tomatoes love warm weather and die when days are cooler, with temperatures dropping to the 30s and 40s. So why are there organic tomatoes in the store in the middle of cold winters? Those tomatoes could’ve been grown in a greenhouse, a human-made structure to recreate warmer environments. Or, they could’ve been grown organically somewhere in the middle of summer in the southern hemisphere and shipped up north (hello, carbon emissions!) so you can access tomatoes year-round.

That 24/7 access isn’t free and excellent flavor is often a sacrifice we pay for eating fruits and vegetables out of season. Chefs and restaurants who offer seasonal offerings, for example, won’t serve bacon, lettuce, tomato (BLT) sandwiches in winter. Not because they’re pretentious, but because it won’t taste as great as it would in summer months. Instead of winter BLTs, these restaurants will proudly whip up seasonal steamed silky sweet potatoes or roasted brussels sprouts with kimchee puree.

When we eat seasonally-available food, it’s more likely we’re eating fresher food. A spring asparagus, summer apricot, fall pear, or winter grapefruit doesn’t have to travel far to get to your plate. With fewer miles traveled, the vitamins, minerals, and secondary metabolites in organic fruits and vegetables won’t degrade as much compared to fruits and vegetables flown or shipped in from other countries. Seasonal food tastes great and it’s great for you too.

If you’re curious to eat more of what’s in season, visit your local farmers market if it’s available to you. Strike up a conversation with the people who grow your food. If farmers markets are not available, take a moment to learn what is in season where you live and try those fruits and vegetables next time to go to the store. This Seasonal Food Guide for all 50 states is a great tool to get you started.

Once you incorporate seasonal fruits and vegetables into your daily meals, your body will thank you for the health boost and your meals will gain those extra flavors. Remember, you’re not a bad cook: you just need to find the right seasonal partners so your dinners are never left without that extra little something ever again.

Sign up for Andrea Castillo’s Seasonal, a newsletter that connects you to the Bay Area food system, one fruit and vegetable at a time. Andrea is a food nerd who always wants to know the what’s, how’s, when’s, and why’s of the food she eats.

References

Baker, B.P., Benbrook, C.M., & Groth III, E., & Lutz, K. (2002). Pesticide residues in conventional, integrated pest management (IPM)-grown and organic foods: insights from three US data sets. Food Additives and Contaminants, 19(5) http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02652030110113799

Barański, M., Średnicka-Tober, D., Volakakis, N., Seal, C., Sanderson, R., Stewart, G., . . . Leifert, C. (2014). Higher antioxidant and lower cadmium concentrations and lower incidence of pesticide residues in organically grown crops: A systematic literature review and meta-analyses. British Journal of Nutrition, 112(5), 794-811. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114514001366

Cardenas, E. (2013). Let not thy food be confused with thy medicine: The Hippocratic misquotation,e-SPEN Journal, I(6), e260-e262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnme.2013.10.002

Peper, E. (2017). Yes, fresh organic food is better! the peper perspective. https://peperperspective.com/2017/10/27/yes-fresh-organic-food-is-better/

Yes, fresh organic food is better!

Posted: October 27, 2017 Filed under: Nutrition/diet, self-healing | Tags: farming, Holistic health, longevity, non-organic foods, nutrition, organic foods, pesticides 16 Comments

Is it really worthwhile to spent more money on locally grown organic fruits and vegetables than non-organic fruits and vegetables? The answer is a resounding “YES!” Organic grown foods have significantly more vitamins, antioxidants and secondary metabolites such as phenolic compounds than non-organic foods. These compounds provide protective health benefits and lower the risk of cancer, cardiovascular disease, type two diabetes, hypertension and many other chronic health conditions (Romagnolo & Selmin, 2017; Wilson et al., 2017; Oliveira et al., 2013; Surh & Na, 2008). We are what we eat–we can pay for it now and optimize our health or pay more later when our health has been compromised.

The three reasons why fresh organic food is better are:

- Fresh foods lengthen lifespan.

- Organic foods have more vitamins, minerals, antioxidants and secondary metabolites than non-organic foods.

- Organic foods reduce exposure to harmful neurotoxic and carcinogenic pesticide and herbicides residues.

Background

With the advent of chemical fertilizers farmers increased crop yields while the abundant food became less nutritious. The synthetic fertilizers do not add back all the necessary minerals and other nutrients that the plants extract from the soil while growing. Modern chemical fertilizers only replace three components–Nitrogen, Phosphorus and Potassium–of the hundred of components necessary for nutritious food. Nitrogen (N) which promotes leaf growth; Phosphorus (P which development of roots, flowers, seeds, fruit; and Potassium (K) which promotes strong stem growth, movement of water in plants, promotion of flowering and fruiting. These are great to make the larger and more abundant fruits and vegetables; however, the soil is more and more depleted of the other micro-nutrients and minerals that are necessary for the plants to produce vitamins and anti-oxidants. Our industrial farming is raping the soils for quick growth and profit while reducing the soil fertility for future generations. Organic farms have much better soils and more soil microbial activity than non-organic farm soils which have been poisoned by pesticides, herbicides, insecticides and chemical fertilizers (Mader, 2002; Gomiero et al, 2011). For a superb review of Sustainable Vs. Conventional Agriculture see the web article: https://you.stonybrook.edu/environment/sustainable-vs-conventional-agriculture/

1. Fresh young foods lengthen lifespan. Old foods may be less nutritious than young food. Recent experiments with yeast, flies and mice discovered that when these organisms were fed old versus young food (e.g., mice were diets containing the skeletal muscle of old or young deer), the organisms’ lifespan was shortened by 18% for yeast, 13% for flies, and 13% for mice (Lee et al., 2017). Organic foods such as potatoes, bananas and raisins improves fertility, enhances survival during starvation and decreases long term mortality for fruit flies(Chhabra et al, 2013). See Live longer, enhance fertility and increase stress resistance: Eat organic foods. https://peperperspective.com/2013/04/21/live-longer-enhance-fertility-and-increase-stress-resistance-eat-organic-foods/

In addition, eating lots of fruits and vegetables decreases our risk of dying from cancer and heart disease. In a superb meta-analysis of 95 studies, Dr. Dagfinn Aune from the School of Public Health, Imperial College London, found that people who ate ten portions of fruits and vegetable per day were a third less likely to die than those who ate none (Aune et al, 2017). Thus, eat lots of fresh and organic fruits and vegetables from local sources that is not aged because of transport.

2. Organic foods have more vitamins, minerals, antioxidants and secondary metabolites than non-organic foods. Numerous studies have found that fresh organic fruits and vegetables have more vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, and secondary metabolites than non-organic ones. For example, organic tomatoes contain 57 per cent more vitamin C than non-organic ones (Oliveira et al 2013) or organic milk has more beneficial polyunsaturated fats non-organic milk (Wills, 2017; Butler et al, 2011). Over the last 50 years key nutrients of fruits and vegetables have declined. In a survey of 43 crops of fruits and vegetables, Davis, Epp, & Riordan, (2004) found a significant decrease of vitamins and minerals in foods grown in the 1950s as compared to 1999 as shown in Figure 1 (Lambert, 2015).

Figure 1. Change in vitamins and minerals from 1950 to 1999. From: Davis, D. R., Epp, M. D., & Riordan, H. D. (2004). Changes in USDA food composition data for 43 garden crops, 1950 to 1999. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 23(6), 669-682.

3, Organic foods reduce exposure to harmful neurotoxic and carcinogenic pesticide and herbicides residues. Even though, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) state that pesticide residues left in or on food are safe and non-toxic and have no health consequences, I have my doubts! Human beings accumulate pesticides just like tuna fish accumulates mercury—frequent ingesting of very low levels of pesticide and herbicide residue may result in long term harmful effects and these long term risks have not been assessed. Most pesticides are toxic chemicals and were developed to kill agricultural pests — living organisms. Remember human beings are living organisms. The actual risk for chronic low level exposure is probably unknown; since, the EPA pesticide residue limits are the result of a political compromise between scientific findings and lobbying from agricultural and chemical industries (Portney, 1992). Organic diets expose consumers to fewer pesticides associated with human disease (Forman et al, 2012).

Adopt the precautionary principle which states, that if there is a suspected risk of herbicides/pesticides causing harm to the public, or to the environment, in the absence of scientific consensus, the burden of proof that it is not harmful falls on those recommending the use of these substances (Read & O’Riordan, 2017). Thus, eat fresh locally produced organic foods to optimize health.

References

Butler, G. Stergiadis, s., Seal, C., Eyre, M., & Leifert, C. (2011). Fat composition of organic and conventional retail milk in northeast England. Journal of Dairy Science. 94(1), 24-36.http://dx.doi.org/10.3168/jds.2010-3331

Davis, D. R., Epp, M. D., & Riordan, H. D. (2004). Changes in USDA food composition data for 43 garden crops, 1950 to 1999. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 23(6), 669-682. http://www.chelationmedicalcenter.com/!_articles/Changes%20in%20USDA%20Food%20Composition%20Data%20for%2043%20Garden%20Crops%201950%20to%201999.pdf

Lambert, C. (2015). If Food really better from the farm gate than super market shelf? New Scientist.228(3043), 33-37.

Oliveira, A.B., Moura, C.F.H., Gomes-Filho, E., Marco, C.A., Urban, L., & Miranda, M.R.A. (2013). The Impact of Organic Farming on Quality of Tomatoes Is Associated to Increased Oxidative Stress during Fruit Development. PLoS ONE, 8(2): e56354. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0056354

Read, R. and O’Riordan, T. (2017). The Precautionary Principle Under Fire. Environment-Science and policy for sustainable development. September-October. http://www.environmentmagazine.org/Archives/Back%20Issues/2017/September-October%202017/precautionary-principle-full.html

Romagnolo, D. F. & Selmin, O.L. (2017). Mediterranean Diet and Prevention of Chronic Diseases. Nutr Today. 2017 Sep;52(5):208-222. doi: 10.1097/NT.0000000000000228. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29051674

Wills, A. (2017). There is evidence organic food is more nutritious. New Scientist,3114, p53.

Wilson, L.F., Antonsson, A., Green, A.C., Jordan, S.J., Kendall, B.J., Nagle, C.M., Neale, R.E., Olsen, C.M., Webb, P.M., & Whiteman, D.C. (2017). How many cancer cases and deaths are potentially preventable? Estimates for Australia in 2013. Int J Cancer. 2017 Oct 6. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31088. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28983918

Don’t poison yourself: Avoid foods with high pesticide residues

Posted: May 1, 2014 Filed under: Nutrition/diet, Uncategorized | Tags: diet, health, pesticides Leave a commentIs it worth to pay $3.49 for the organic strawberries while the non-organics are a bargain at $2.49?

Are there foods I should avoid because they have high pesticide residues?

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) state that pesticide residues left in or on food are safe and non-toxic and have no health consequences. I have my doubts! Human beings accumulate pesticides just like tuna fish accumulates mercury—frequent ingesting of very low levels of pesticides residue may result in long term harmful effects and these long term risks have not been assessed. Most pesticides are toxic chemicals and were developed to kill agricultural pests — living organisms. The actual risk for chronic low level exposure is probably unknown; since, the EPA pesticide residue limits are a political compromise between scientific findings and lobbying from agricultural and chemical industries (Portney, 1992).

Organic diets expose consumers to fewer pesticides associated with human disease (Forman et al, 2012). In addition, preliminary studies have shown that GMO foods such as soy, potatoes, bananas and raisins reduces longevity, fertility and starvation tolerance in fruit flies (Chhabra et al, 2013)

Adopt the precautionary principle. As much as possible avoid the following foods that have high levels of residual pesticides as identified by the Environmental Working Group in their 2014 report.

Apples

Strawberries

Grapes

Celery

Peaches

Spinach

Sweet bell peppers

Nectarines-imported

Cucumbers

Cherry tomatoes

Snap peas-imported

Potatoes

Hot peppers

Blueberries-domestic

Lettuce

Kale/collard greens

For more details, see the Environmental Working Group report for the rankings of 48 foods listed from worst to best.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=BfNQGd9BTK0

References:

Chhabra R, Kolli S, Bauer JH (2013) Organically Grown Food Provides Health Benefits to Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS ONE 8(1): e52988. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0052988 http://www.plosone.org/article/info:doi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0052988

Portney, P. R. (1992). The determinants of pesticide regulation: A statistical analysis of EPA decision making. The Journal of Political Economy, 100(1), 175-197.