Fever can save your life

Posted: March 22, 2025 Filed under: attention, cancer, health, Pain/discomfort, Uncategorized | Tags: acetaminophen, books, classical conditioning, fever, food, immune response, lifestyle, mental-health, self-care, travel 3 CommentsErik Peper, PhD and Robert Gorter, MD, PhD

Adapted from: Peper, E. & Gorter, R. (2025). Fever can save your life. Townsend Letter-Innovative Health Perspective. Published March 27, 2025. https://townsendletter.com/fever-can-save-your-life/

My child’s fever was 102 F° and I was worried. I made my daughter comfortable, gave her some liquids and applied a lemon wrap around the calves. Fifteen minutes later the fever was down by a degree and a half to 100.5 F.° I continue to check how my child was doing. I touched her forehead and noted that it became slightly cooler. By the next day the fever had broken, and my daughter felt much better.

Most people are worried when they or their children have a fever, as it may indicates an illness. They quickly rush to take a Tylenol or other medications to reduce the fever and discomfort. We question whether this almost automatic response to inhibit fever is the best approach. It is important to note that fever is seldom the cause of illness; instead, fever is the body’s response to support healing by activating the immune system so that it can fight the infection. In most cases, the fever may last for a day or two and then disappears. Watchful waiting does not mean, not seeking medical help. It means careful monitoring so that the fever does not go too high versus automatically taking medications to suppress the fever.

Although fever can be uncomfortable, in most casest is not something to be feared. Rather than suppressing it, allow the fever to run its course, as fevers can improve clinical outcomes. Research findings indicate that individuals who experience an increase in body temperature (i.e., a fever) have higher survival rates following infection (Repasky et al., 2013). Spontaneous remissions of cancer—altogether a rarer event—have been observed repeatedly in connection with febrile infectious diseases, especially those of bacterial origin (Kienle, 2012). Late in 19th and early 20th century, Prof Coley observed that in patients who had wound fever or fevers that were induced by injecting bacterial toxins, their cancer sometimes disappeared (Kienle, 2012). In the early 20th century, inducing fever with injecting a bacterial toxin became an acceptable and somewhat successful treatment strategy for treating cancer (Karamanou, et al., 2013; Kendell et al, 1969). It was even a fairly successful treatment for neuro-syphilis before advent of antibiotics. Malaria-induced fevers were used as a treatment for neurosyphilis from the 1920s until the 1950s,—the spiking fevers associated with malaria killed the bacteria that caused the syphilitic infection (Gambino, 2015). The fever therapy slowly disappeared as antibiotics (penicillin), chemotherapy and radiation tended to be more effective.

Although suppressing fever with medication may make you feel more comfortable, and in some cases allow a child to go to day care, it may be harmful. Dr. Schulman and colleagues at the University of Miami Leonard M. Miller School of Medicine demonstrated in a randomized controlled study that, among similar patients admitted to the ICU, the risk of death was seven times higher for those who received fever-reducing medication compared to those who did not (Schulman et al., 2005).(Schulman et al., 2005).

Fever reducing medication may in rare cases lead to complications. For example, aspirin may cause stomach irritation and ulcers as well as being cofactor in Reye’s syndrome (Temple, 1981; Schrör 2007). While acetaminophen (also known as paracetamol), often given to young children, may increase the risk of allergic rhinitis and possibly asthma by the age of six (Caballero, et al., 2015; McBride, 2011). As McBride point out, there appears to be a correlation between acetaminophen use and asthma across all groups, ages and location. This correlation even holds up for mothers who took acetaminophen during pregnancy as their children have increased risk for asthma by age six.

As Bauer and colleagues (Bauer et al., 2021) point out: “Paracetamol (N-acetyl-p-aminophenol (APAP), otherwise known as acetaminophen) is the active ingredient in more than 600 medications (Excedrine) used to relieve mild to moderate pain and reduce fever. Research suggests that prenatal exposure to APAP might alter fetal development, which could increase the risks of some neurodevelopmental, reproductive and urogenital disorders. Pregnant women should be cautioned at the beginning of pregnancy to: forego APAP unless its use is medically indicated. This Consensus Statement reflects our concerns and is currently supported by 91 scientists, clinicians and public health professionals from across the globe.”

Finally, we wonder whether active fever suppression during childhood might condition the immune system not to initiate a fever response through the process of classical conditioning, thereby reducing the immune system’s overall competence. This could be a contributing factor to the increasing rates of allergies, immune disorders, and the earlier onset of certain cancers (Gorter & Peper, 2011). Specifically, if a person begins to develop a fever and medication was used to reduce it, over time the fever response may become automatically inhibited through covert classical conditioning.

Simple home remedy when having a fever?

- Practice watchful waiting. This means monitoring the person and only use medication to reduce fever if necessary. When in doubt contact your physician. Remember, in almost all cases, fever is not the illness; it is the body’s response to fight the illness and regain health.

- Hydrate. When having a fever, we perspire and need more fluids. Thus, increase fluid intake. Almost all cultural traditions recommend drinking some fluids such as hot water with lemon juice and honey, chicken soup broth, etc.

- Reframe the experience as a healing experience versus an illness experience. For example, when a fever, reframe it possitively such as, I feel pleased that my body is responding and I trust that my body is fighting the illness well (or even better).

- Implement the following gentle self-care approaches (Schirm, 2018).

Lemon wrap around calves or feet may help reduce fevers by using the cooling properties of lemon and evaporating water. How to make lemon wraps:

• Fill a bowl with water that’s 2–3° C below your fever temperature.

• Add 1–2 lemon halves.

• Score the lemon peel with a knife to release essential oils.

• Mash the lemons in the water.

• Soak a cloth in the lemon water.

• Wrap the cloth around your calves from ankle to knee.

• Cover with a blanket and rest for 10–15 minutes.

• Repeat as needed.

“Tips for using lemon wraps

• Change the wraps when they become warm.

• If your feet get cold, stop using the wraps.

• Don’t over-bundle a child with blankets, as babies can’t regulate their body temperatures as well as adults.

The information in this blog is designed for educational purposes only and is not intended to be a substitute for informed medical advice or care. This information should not be used to diagnose or treat any health problems or illnesses without consulting a doctor. Consult with a health care practitioner before relying on any information in this article or on this website.

References

Bauer, A.Z., Swan, S.H., Kriebel, D. et al. Paracetamol use during pregnancy — a call for precautionary action. Nat Rev Endocrinol (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-021-00553-7

Caballero, N., Welch, K. C., Carpenter, P. S., Mehrotra, S., O’Connell, T. F., & Foecking, E. M. (2015). Association between chronic acetaminophen exposure and allergic rhinitis in a rat model. Allergy & rhinology (Providence, R.I.), 6(3), 162–167. https://doi.org/10.2500/ar.2015.6.0131

Gambino, M. (2015). Fevered Decisions: Race, Ethics, and Clinical Vulnerability in the Malarial Treatment of Neurosyphilis, 1922-1953. Hastings Center Report. https://doi.org/10.1002/hast.451

Gorter, R. & Peper, E. (2011). Fighting Cancer: A Nontoxic Approach to Treatment. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books. https://www.amazon.com/Fighting-Cancer-Nontoxic-Approach-Treatment/dp/1583942483

Karamanou, M., Liappas, I., Antoniou, C.h, Androutsos, G., & Lykouras, E. (2013). Julius Wagner-Jauregg (1857-1940): Introducing fever therapy in the treatment of neurosyphilis. Psychiatrike = Psychiatriki, 24(3), 208–212. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24185088/

Kendell, H. W., Rose, D. L., & Simpson, W. M. (1969). Fever therapy technique in syphilis and gonococcic infections. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 50(10), 603–608. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4981888/

Kienle G. S. (2012). Fever in Cancer Treatment: Coley’s Therapy and Epidemiologic Observations. Global advances in health and medicine, 1(1), 92–100. https://doi.org/10.7453/gahmj.2012.1.1.016

McBride, J.T. (2011). The Association of Acetaminophen and Asthma Prevalence and Severity. Pediatrics, 128(6), 1181–1185. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-1106

Repasky, E. A., Evans, S. S., & Dewhirst, M. W. (2013). Temperature matters! And why it should matter to tumor immunologists. Cancer immunology research, 1(4), 210–216. https://doi.org/10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0118

Schirm, J. (2018). Essentials of homecare-A gentle approach to healing. Holistic Essence. https://www.amazon.com/Essentials-Home-Care-II-Approach/dp/0692121250

Schulman, C. I., Namias, N., Doherty, J., Manning, R. J., Li, P., Elhaddad, A., Lasko, D., Amortegui, J., Dy, C. J., Dlugasch, L., Baracco, G., & Cohn, S. M. (2005). The effect of antipyretic therapy upon outcomes in critically ill patients: a randomized, prospective study. Surgical infections, 6(4), 369–375. https://doi.org/10.1089/sur.2005.6.369

Schrör K. (2007). Aspirin and Reye syndrome: a review of the evidence. Paediatric drugs, 9(3), 195–204. https://doi.org/10.2165/00148581-200709030-00008

Temple, A.R. (1981). Acute and Chronic Effects of Aspirin Toxicity and Their Treatment. Arch Intern Med, 141(3), 364–369. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.1981.00340030096017

Pragmatic techniques for monitoring and coaching breathing

Posted: December 14, 2024 Filed under: attention, behavior, biofeedback, Breathing/respiration, emotions, meditation, mindfulness, neurofeedback, Pain/discomfort, posture, relaxation, self-healing, Uncategorized | Tags: art, books, Breathing rate, coaching, FlowMD app, nasal breathing, personal-development, self-monitoring, writing 4 CommentsDaniella Matto, MA, BCIA BCB-HRV , Erik Peper, PhD, BCB, and Richard Harvey, PhD

Adapted from: Matto, D., Peper, E., & Harvey, R. (2025). Monitoring and coaching breathing patterns and rate. Townsend Letter-Innovative Health Perspectives. https://townsendletter.com/monitoring-and-coaching-breathing-patterns-and-rate/

This blog aims to describe several practical strategies to observe and monitor breathing patterns to promote effortless diaphragmatic breathing. The goal of these strategies is to foster effortless, whole-body diaphragmatic breathing that promote health.

Breathing is usually covert and people are not usually aware of their breathing rate (breaths per minute) or pattern (abdominal or thoracic, breath holding or shallow breathing) unless they have an illness such as asthma, emphysema or are performing physical activity (Boulding et al, 2015)). Observing breathing is challenging; awareness of respiration often leads to unaware changes in the breath pattern or to an attempt to breathe perfectly (van Dixhoorn, 2021). Ideally breathing patterns should be observed/monitored when the person is unaware of their breathing pattern and the whole body participates (van Dixhoorn, 2008). A useful strategy is to have the person perform a task and then ask, “What happened to your breathing?”. For example, ask a person to simulate putting a thread through the eye of a needle or quickly look to the extreme right and left while keeping their head still. In almost all cases, the person holds their breath (Peper et al., 2002).

Teaching effortless slow diaphragmatic breathing is a precursor of Heart rate variability (HRV) biofeedback and is based on slow paced breathing (Lehrer & Gevirtz, 2014; Steffen et al., 2017; Shaffer and Meehan, 2020). Mastering effortless diaphragmatic breathing is a powerful tool in the treatment of a variety of physical, behavioural, and cognitive conditions; however, to integrate this method into clinical or educational practice is easier said than done. Clients with dysfunctional breathing patterns often have difficulty following a breath pacer or mastering effortless breathing at a slower pace.

The purpose of this paper is to describe a few simple strategies that can be used to observe and monitor breathing patterns, provide economic strategies for observation and training, and suggestions to facilitate effortless diaphragmatic breathing.

Strategies to observe and monitor breathing pattern

Observation of the breathing patterns

- Is the breathing through the nose or mouth? Nose is usually better (Watso et al., 2023; Nestor, 2020).

- Does the abdomen expand during inhalation and constricts during exhalation or does the chest expand and rise during inhalation and fall during exhalation? Abdominal movement is usually better.

- Is exhalation flow softly or explosively like a sigh? Slow flow exhalation is preferred.

- Is the breath held or continues during activities? In most cases continued breathing is usually better.

- Does the person gasp before speaking or allows to speak while normally exhaling?

- What is the breathing rate (breaths per minute)? When sitting peacefully less than 14 breaths/minute is usually better and about 6 breaths per minute to optimize HRV

Physiological monitoring.

- Monitoring breathing with strain gauges around the abdomen and chest, and heart rate is the most common approach to identify the location of breath, the breathing pattern and heart rate variability. The strain gauges are placed around the chest and abdomen and heart rate is monitored with a blood volume pulse amplitude sensor from the finger. representative recording shows the effect of thoughts on breathing, heartrate and pulse amplitude of which the participant is totally unaware as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Physiological recording of breathing patterns with strain gauges.

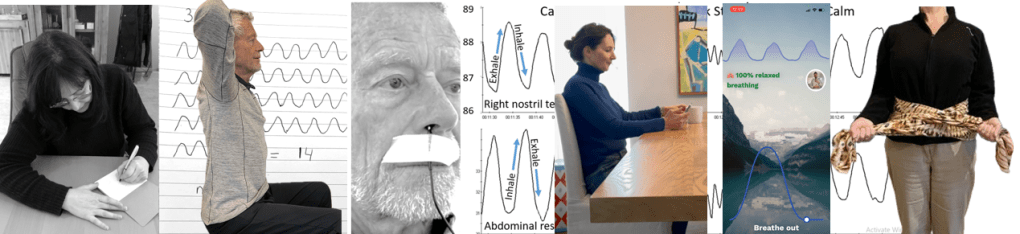

- Monitoring breathing with a thermistor placed at the entrance of the nostril that has the most airflow (nasal patency) (Jovanov et al., 2001; Lerman et al., 2016). When the person exhales through the nose, the thermistor temperature increases and decreases when they inhale. A representative recording of a person being calm, thinking a stressful thought. and being calm. Although there were significant changes as indicated by the change in breathing patterns, the person was unaware of the changes as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Use of a thermistor to monitor breathing from the dominant nostril compared to the abdominal expansion as monitored by a strain gauge around the abdomen.

- Additional physiological monitoring approaches. There are many other physiological measures can be monitored to such as end-tidal carbon dioxide (EtCO2), a non-invasive measurement of the amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) in exhaled breath (Meuret et al., 2008; Meckley, 2013); scalene/trapezius EMG to identify thoracic breathing (Peper & Tibbett, 1992; Peper & Tibbets, 1994); low abdominal EMG to identify transfers and oblique tightening during exhalation and relaxation during inhalation (Peper et al., 2016; and heart rate to monitor cardiorespiratory synchrony (Shaffer & Meehan, 2020). Physiological monitoring is useful; since, the clinician and the participant can observe the actual breathing pattern in real time, how the pattern changes in response the cognitive and physical tasks, and used for feedback training. The recorded data can document breathing problems and evidence of mastery.

The challenges of using physiological monitoring arethat the equipment may be expensive, takes skill to operate and interpret the data, and is usually located in the office and not at home.

Economic strategies for observation and training breathing

To complement the physiological monitoring and allow observations outside the office and at home, some of the following strategies may be used to observe breathing pattern (rate and expansion of the breath in the body), and suggestion to facilitate effortless diaphragmatic breathing. These exercises make excellent homework for the client. Practicing awareness and internal self-regulation by the client outside the clinic contributes enormously to the effect of biofeedback training (Wilson et al., 2023),

Observe breathing rate: Draw the breathing pattern

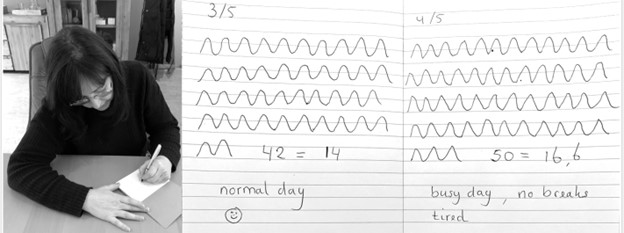

Take a piece of paper, a pen and a timer, set to 3 minutes. Start the timer. Upon inhalation draw the line up and upon exhalation draw the line down, creating a wave. When the timer stops, after 3 minutes, calculate the breathing rate per minute by dividing the number of waves by 3 as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Drawing the breathing pattern for three minutes during two different days.

From these drawings, the breathing rate become evident. Many individuals are often surprised to discover that their breathing rate increased during periods of stress, such as a busy day with no breaks, compared to their normal days.

Monitoring and training diaphragmatic breathing

The scarf technique for abdominal feedback

Many participants are unaware that they are predominantly breathing in their chest and their abdomen expansion is very limited during inhalation. Before beginning, have participant loosen their belt and or stand upright since sitting collapsed/slouched or having the waist constriction such as a belt of tight constrictive clothing that inhibits abdominal expansion during inhalation.

Place the middle part of a long scarf or shawl on your lower back, take the ends in both hands and cross the ends: your left hand is holding the right part of the scarf, and the right hand is holding the left end of the scarf. Give a bit of a pull, so you can feel any movement of the scarf. When breathing more abdominally you will feel a pull at the ends of the scarf as you lower back, and flanks will expand as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Using a scarf as feedback.

FlowMD app

A recent cellphone app, FlowMD, is unique because it uses the cellphone camera to detect the subtle movements of the chest and abdomen (FlowMD, 2024). It provides real time feedback of the persons breathing pattern. Using this app, the person sits in front of their cellphone camera and after calibration, the breathing pattern is displayed as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Training breathing with FlowMD,.

Suggestions to optimize abdominal breathing that may lead to a slower breath rate when the client practices the technique

Beach pose

By locking the upper chest and sitting up straight it is often easier to breathe so that the abdomen can expand and constrict. Place your hands behind your head and Interlock your finger of both hands, pull your elbows back and up. The person can practice this either laying down on their back or sitting straight up at the edge of the chair as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Sitting erect with the shoulders pulled back and up to allow abdominal expansion and constriction as the breathing pattern.

Observe the effect of posture on breathing

Have the person sit slouched/collapsed like a letter C and take a few slow breath, then have them sit up in a tall and erect position and take a few slow breaths. Usually they will observe that it is easier to breathe slower and lower and tall and erect.

Using your hands for feedback to guide natural breathing

Holding your hands with index fingers and thumbs touching the lower abdomen. When inhaling the fingers and thumbs separate and when exhaling they touch again (ensuring a full exhale and avoiding over breathing). The slight increase in lower abdominal muscle tension during the exhalation and relaxation during inhalation and the abdominal wall expands can also be felt with fingertips as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Using your hands and finger for feedback to guide the natural breathing of expansion and constriction of the abdomen. Reproduced by permission from Peper, E., Booiman, A., Lin, I-M, Harvey, R., & Mitose, J. (2016). Abdominal SEMG Feedback for Diaphragmatic Breathing: A Methodological Note. Biofeedback. 44(1), 42-49.

Coaching suggestions

There are many strategies to observe, teach and implement effortless breathing (Peper et al., 2024).. Even though breathing is natural and babies and young children breathe diaphragmatically as their large belly expands and constricts. Yet, in many cases the natural breathing shifts to dysfunctional breathing for multiple reasons such as chronic triggering defense reactions to avoiding pain following abdominal surgery (Peper et al, 2015). When participants initially attempt to relearn this natural pattern, it can be challenging especially, if the person habitually breathes shallowly, rapidly and predominantly in their chest.

When initially teaching effortless breathing, have the person exhale more air than normal without the upper chest compressing down and instead allow the abdomen comes in and up thereby exhaling all the air. If the person is upright then allow inhalation to occur without effort by letting the abdominal wall relaxes and expands. Initially inhale more than normal by expanding the abdomen without lifting the chest. Then exhale very slowly and continue to breathe so that the abdomen expands in 360 degrees during inhalation and constricts during exhalation. Let the breathing go slower with less and less effort. Usually, the person can feel the anus dropping and relaxing during inhalation.

Another technique is to ask the person to breathe in more air than normal and then breathe in a little extra air to completely fill the lungs, before exhaling fully. Clients often report that it teaches them to use the full capacity of the lungs.

The goal is to breath without effort. Indirectly this can be monitored by finger temperature. If the finger temperature decreases, the participant most likely is over-breathing or breathing with too much effort, creating sympathetic activity; if the finger temperature increases, breathing occurs slower and usually with less effort indicating that the person’s sympathetic activation is reduced.

Conclusion

There are many strategies to monitor and coach breathing. Relearning diaphragmatic breathing can be difficult due to habitual shallow chest breathing or post-surgical adaptations. Initial coaching may involve extended exhalations, conscious abdominal expansion, and gentle inhalation without chest movement. Progress can be monitored through indirect physiological markers like finger temperature, which reflects changes in sympathetic activity. The integration of these techniques into clinical or educational practice enhances self-regulation, contributing significantly to therapeutic outcomes. In this article we provided a few strategies which may be useful for some clients.

Additional blogs on breathing

https://peperperspective.com/2015/09/25/resolving-pelvic-floor-pain-a-case-report/

REFERENCES

Boulding, R., Stacey, R., & Niven, N. (2016). Dysfunctional breathing: a review of the literature and proposal for classification. European Respiratory Review, 25(141),: 287-294. https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0088-2015

FlowMD. (2024). FlowMD app. Accessed December 13, 2024. https://desktop.flowmd.co/

Jovanov, E., Raskovic, D., & Hormigo, R. (2001). Thermistor-based breathing sensor for circadian rhythm evaluation. Biomedical sciences instrumentation, 37, 493–497. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11347441/

Lehrer, P. & Gevirtz R. (2014). Heart rate variability biofeedback: how and why does it work? Front Psychol, 5,756. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00756

Lerman, J., Feldman, D., Feldman, R. et al. Linshom respiratory monitoring device: a novel temperature-based respiratory monitor. (2016). Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth, 63, 1154–1160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-016-0694-y

Meckley, A. (2013). Balancing Unbalanced Breathing: The Clinical Use of Capnographic Biofeedback. Biofeedback, 41(4), 183–187. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-41.4.02

Meuret, A. E., Wilhelm, F. H., Ritz, T., & Roth, W. T. (2008). Feedback of end-tidal pCO2 as a therapeutic approach for panic disorder. Journal of psychiatric research, 42(7), 560–568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.06.005

Nestor, J. (2020). Breath: The New Science of a Lost Art. New York: Riverhead Books. https://www.amazon.com/Breath-New-Science-Lost-Art/dp/0735213615/

Peper, E., Booiman, A., Lin, I-M, Harvey, R., & Mitose, J. (2016). Abdominal SEMG Feedback for Diaphragmatic Breathing: A Methodological Note. Biofeedback. 44(1), 42-49. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-44.1.03

Peper, E., Gilbert, C.D., Harvey, R. & Lin, I-M. (2015). Did you ask about abdominal surgery or injury? A learned disuse risk factor for breathing dysfunction. Biofeedback. 34(4), 173-179. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-43.4.06

Peper, E., Gibney, K.H., & Holt, C.F. (2002). Make Health Happen. Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company. https://he.kendallhunt.com/product/make-health-happen-training-yourself-create-wellness

Peper, E., Oded, Y., Harvey, R., Hughes, P., Ingram, H., & Martinez, E. (2024). Breathing for health: Mastering and generalizing breathing skills. Townsend Letter-Innovative Health Perspectives. November 15, 2024. https://townsendletter.com/suggestions-for-mastering-and-generalizing-breathing-skills/

Peper, E., & Tibbetts, V. (1992). Fifteen-month follow-up with asthmatics utilizing EMG/incentive inspirometer feedback. Biofeedback and self-regulation, 17(2), 143–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01000104

Peper, E. & Tibbetts, V. (1994). Effortless diaphragmatic breathing. Physical Therapy Products. 6(2), 67-71. https://biofeedbackhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/peper-and-tibbets-effortless-diaphragmatic.pdf

Shaffer, F. and Meehan, Z.M. (2020). A Practical Guide to Resonance Frequency Assessment for Heart Rate Variability Biofeedback. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 14. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnins.2020.570400

Steffen, P.R., Austin, T., DeBarros, A., and Brown, T. (2017). The Impact of Resonance Frequency Breathing on Measures of Heart Rate Variability, Blood Pressure, and Mood. Front Public Health, 5, 222. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00222

van Dixhoorn, J.V. (2008). Whole-body breathing. Biofeedback, 36,54–58. https://www.euronet.nl/users/dixhoorn/L.513.pdf

van Dixhoorn, J.V. (2021). Functioneel ademen-Adem-en ontspannings oefeningen voor gevorderden. Amersfoort: Uiteveriy Van Dixhoorn. https://www.bol.com/nl/nl/p/functioneel-ademen/9300000132165255/

Watso, J. C., Cuba, J.N., Boutwell, S.L, Moss, J…(2023). Acute nasal breathing lowers diastolic blood pressure and increases parasympathetic contributions to heart rate variability in young adults. American Journal of Physiology Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology.

325I(6), R797-R80. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.00148.2023

Wilson, V., Somers, K. & Peper, E. (2023). Differentiating Successful from Less Successful Males and Females in a Group Relaxation/Biofeedback Stress Management Program. Biofeedback, 51(3), 53–67. https://doi.org/10.5298/608570

[1] Correspondence should be addressed to:

Erik Peper, Ph.D., Institute for Holistic Health Studies, San Francisco State University, 1600 Holloway Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94132 Tel: 415 338 7683 Email: epeper@sfsu.edu web: www.biofeedbackhealth.org blog: www.peperperspective.com