Breathe Away Menstrual Pain- A Simple Practice That Brings Relief *

Posted: November 22, 2025 Filed under: attention, behavior, biofeedback, Breathing/respiration, cognitive behavior therapy, education, emotions, Neck and shoulder discomfort, Pain/discomfort, posture, relaxation, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: dysmenorrhea, health, meditation, menstrual cramps, mental-health, mindfulness, wellness 2 CommentsAdapted from: Peper, E. Harvey, R., Chen, & Heinz, N. (2025). Practicing diaphragmatic breathing reduces menstrual symptoms both during in-person and synchronous online teaching. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, Published online: 25 October 2025. https://rdcu.be/eMJqt https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-025-09745-7

“Once again, the pain starts—sharp, deep, and overwhelming—until all I can do is curl up and wait for it to pass. There’s no way I can function like this, so I call in sick. The meds take the edge off, but they don’t really fix anything—they just mask it for a little while. I usually don’t tell anyone it’s menstrual pain; I just say I’m not feeling well. For the next couple of days, I’m completely drained, struggling just to make it through.

Many women experience discomfort during menstruation, from mild cramps to intense, even disabling pain. When the pain becomes severe, the body instinctively responds by slowing down—encouraging rest, curling up to protect the abdomen, and often reaching for medication in hopes of relief. For most, the symptoms ease within a day or two, occasionally stretching into three, before the body gradually returns to balance.

Another helpful approach is to practice slow abdominal breathing, guided by a breathing app FlowMD. In our study led by Mattia Nesse, PhD, in Italy, the response of one 22-year-old woman illustrated the power of this simple practice.

“Last night my period started, so I was a bit discouraged because I knew I’d get stomach pain, etc. On the other hand, I said, “Okay, let’s see if the breathing works,” and it was like magic — incredible. I’ll need to try it more times to understand whether it consistently has the same effect, but right now it truly felt magical. Just 3 minutes of deep breathing with the app were enough, and I’m not saying I don’t feel any pain anymore, but it has decreased a lot, so thank you! Thank you again for this tool… I’m really happy!”

The Silent Burden of Menstrual Pain

Menstrual pain, or dysmenorrhea, affects most women at some point in their lives — often silently. For many, the monthly cycle brings not only physical discomfort but also shame, fatigue, and interruptions to work or school. It is one of the leading causes of absenteeism and reduced productivity worldwide (Itani et al., 2022; Thakur & Pathania, 2022). In addition, the estimated health cost ranged from US $1367 to US$ 7043 per year (Huang et al., 2021). Yet, despite its prevalence, most women are never taught how to use their own physiology to ease these symptoms.

The Study (Peper et al, 2025)

Seventy-five university women participated across two upper-division Holistic Health courses. Forty-nine practiced 30 minutes per day of breathing and relaxation over five weeks as well as practicing the moment they anticipated or felt discomfort; twenty-six served as a comparison group without a specific daily self-care routine. Students rated change in menstrual symptoms on a scale from –5 (“much worse”) to +5 (“much better”). For the detailed steps in training, see the blog: https://peperperspective.com/2023/04/22/hope-for-menstrual-cramps-dysmenorrhea-with-breathing/ (Peper et al., 2023).

What changed

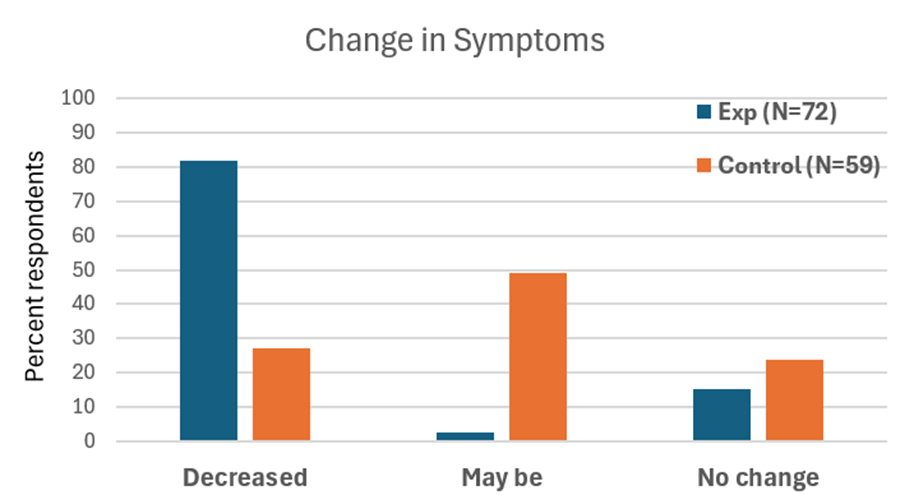

The results were striking. Women who practiced breathing and relaxation showed significant decrease in menstrual symptoms compared to the non-intervention group (p = 0.0008) as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Decrease in menstrual symptoms as compared to the control group after implementing slow diaphragmatic breathing.

Why does breathing and posture change have a beneficial effect?

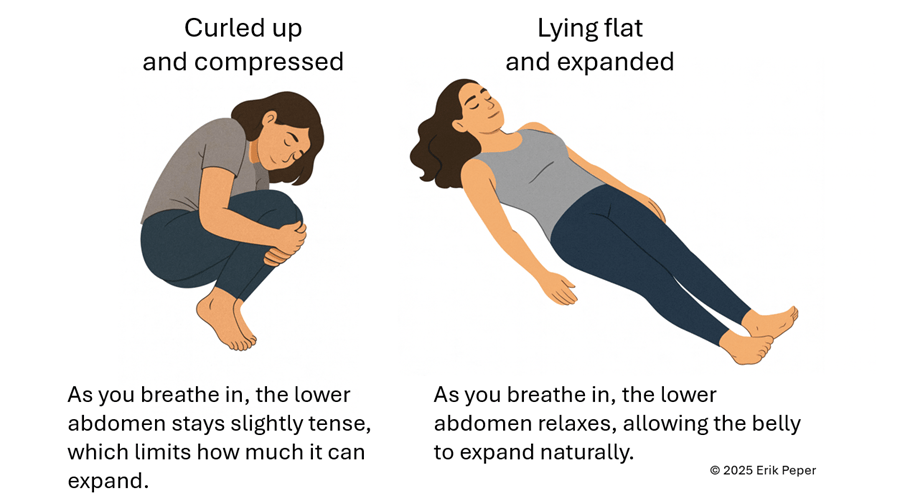

When you stay curled up, your abdomen becomes compressed, leaving little room for the lower belly to relax or for the diaphragm to move freely. The result? Tension builds, and pain often increases.

To reverse this, create space for relaxation. Gently loosen your waist and let your abdomen expand as you inhale. Uncurl your body—lengthen your spine and open your chest, as shown in Figure 2. With each easy breath, you invite calm and allow your body to shift from tension to ease.

Figure 2. Curling up compresses the abdomen and prevents relaxation of the lower belly. In contrast, lying flat with the body gently expanded allows the abdomen to move freely with each breath, which can help reduce menstrual discomfort.

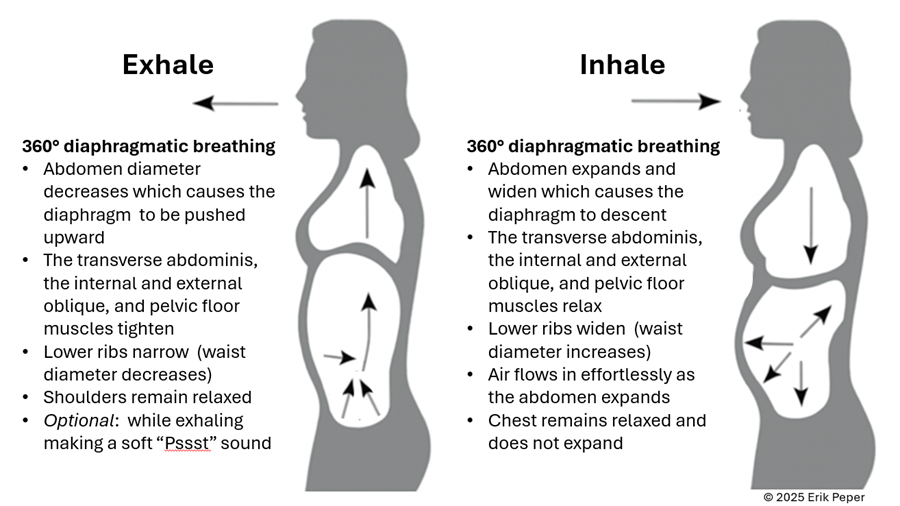

In contrast, slow abdominal or diaphragmatic breathing activates the body’s natural relaxation response. It quiets the stress-driven sympathetic nervous system, calms the mind, and improves circulation in the abdominal area. With each slow breath in, the abdomen gently expands while the pelvic floor and abdominal muscles relax. As you exhale, these muscles naturally tighten slightly, helping to massage and move blood and lymph through the abdominal region. This rhythmic movement supports healing and ease, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3. The dynamic process of diaphragmatic breathing.

The process of slower, lower diaphragmatic breathing

When lying down, rest comfortably on your back with your legs slightly apart. Allow your abdomen to rise naturally as you inhale and fall as you exhale. As you breathe out, imagine the air flowing through your abdomen, down your legs, and out through your feet. To deepen this sensation, you can ask a partner to gently stroke from your abdomen down your legs as you exhale—helping you sense the flow of release through your body.

Gently focus on slow, effortless diaphragmatic breathing. With each inhalation, your abdomen expands, and the lower belly softens. As you exhale, the abdomen gently goes down pushing the diaphragm upward and allowing the air to leave easily. Breathing slowly—about six breaths per minute—helps engage the body’s natural relaxation response.

If you notice that your breath is staying high in your chest instead of expanding through the abdomen, your symptoms may not improve and can even increase. One participant experienced this at first. After learning to let her abdomen expand with each inhalation while keeping her shoulders and chest relaxed, her next menstrual cycle was markedly easier and far less uncomfortable. The lesson is clear: technique matters.

“During times of pain, I practiced lying down and breathing through my stomach… and my cramps went away within ten minutes. It was awesome.” — 22-year-old college student

“Whenever I felt my cramps worsening, I practiced slow deep breathing for five to ten minutes. The pain became less debilitating, and I didn’t need as many painkillers.” — 18-year-old college student

These successes point out that it’s not just breathing — it’s how you breathe by providing space for the abdomen to expand during inhalation.

Practice: How to Do Diaphragmatic Breathing

- Find a quiet space. Lie on your back or sit comfortably erect with your shoulders relaxed.

- Place one hand on your chest and one on your abdomen.

- Inhale slowly through your nose for about 3–4 seconds. Let your abdomen expand as you breathe in — your chest should remain relaxed.

- Exhale gently through your mouth for 4—6 seconds, allowing the abdomen to fall or constrict naturally.

- As you exhale imagine the air moving down your arms, through your abdomen, down your legs, and out your feet

- Practice daily for 20 minutes and also for 5–10 minutes during the day when menstrual discomfort begins.

- Add warmth. Placing a warm towel or heating pad over your abdomen can enhance relaxation while lying on your back and breathing slowly.

With regular practice and implementing it during the day when stressed, this simple method can reduce cramps, promote calm, and reconnect you with your body’s natural rhythm.

Implement the ABCs during the day

The ABC sequence—adapted from the work of Dr. Charles Stroebel, who developed The Quieting Reflex (Stroebel, 1982)—teaches a simple way to interrupt stress reactions in real time. The moment you notice discomfort, pain, stress, or negative thoughts, interrupt the cycle with a simple ABC strategy:

A — Adjust your posture

Sit or stand tall, slightly arch your lower back and allowing the abdomen to expand while you inhale and look up. This immediately shifts your body out of the collapsed “defense posture’ and increases access to positive thoughts (Tsai et all, 2016; Peper et al., 2019)

B — Breathe

Allow your abdomen to expand as you inhale slowly and deeply. Let it get smaller as you exhale. Gently make a soft hissing sound as you exhale while helps the abdomen and pelvic floor to tighten. Then allow the abdomen to relax and widen which without effort draws the air in during inhalation. As you exhale, stay tall and imagine the air flowing through you and down your legs and out your feet.

C — Concentrate

Refocus your attention on what you want to do and add a gentle smile. This engages positive emotions, the smile helps downshift tension.

The video clip guides you through the ABCs process.

Integrate the breathing during the day by implementing your ABCs

When students practice relaxation technique and this method, they reported greater reductions in symptoms compared with a control group. By learning to notice tension and apply the ABC steps as soon as stress arises, they could shift their bodies and minds toward calm more quickly, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Change in symptoms after practicing a sequential relaxation and breathing techniques for four weeks.

Takeaway

Menstrual pain doesn’t have to be endured in silence or masked by medication alone. By practicing 30 minutes of slow diaphragmatic breathing daily and many times during the day, women may be able to reduce pain, stress, and discomfort — while building self-awareness and confidence in their body’s natural rhythms thereby having the opportunity to be more productive.

We recommend that schools and universities include self-care education—especially breathing and relaxation practices—as part of basic health curricula as this approach is scalable. Teaching young women to understand their bodies, manage stress, and talk openly about menstruation can profoundly improve well-being. It not only reduces physical discomfort but also helps dissolve the stigma that still surrounds this natural process,

Remember: Breathing is free—available anytime, anywhere and is helpful in reducing pain and discomfort. (Peper et al., 2025; Joseph et al., 2022)

See the following blogs for more in-depth information and practical tips on how to learn and apply diaphragmatic breathing:

REFERENCES

Itani, R., Soubra, L., Karout, S., Rahme, D., Karout, L., & Khojah, H.M.J. (2022). Primary Dysmenorrhea: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment Updates. Korean J Fam Med, 43(2), 101-108. https://doi.org/10.4082/kjfm.21.0103

Huang, G., Le, A. L., Goddard, Y., James, D., Thavorn, K., Payne, M., & Chen, I. (2022). A systematic review of the cost of chronic pelvic pain in women. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada, 44(3), 286–293.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogc.2021.08.011

Joseph, A. E., Moman, R. N., Barman, R. A., Kleppel, D. J., Eberhart, N. D., Gerberi, D. J., Murad, M. H., & Hooten, W. M. (2022). Effects of slow deep breathing on acute clinical pain in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Evidence-Based Integrative Medicine, 27, 2515690X221078006. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515690X221078006

Peper, E., Booiman, A. & Harvey, R. (2025). Pain-There is Hope. Biofeedback, 53(1), 1-9. http://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-53.01.16

Peper, E., Chen, S., Heinz, N., & Harvey, R. (2023). Hope for menstrual cramps (dysmenorrhea) with breathing. Biofeedback, 51(2), 44–51. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-51.2.04

Peper, E., Harvey, R., Chen, S., & Heinz, N. (2025). Practicing diaphragmatic breathing reduces menstrual symptoms both during in-person and synchronous online teaching. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. Published online: 25 October 2025. https://rdcu.be/eMJqt https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-025-09745-7

Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Hamiel, D. (2019). Transforming thoughts with postural awareness to increase therapeutic and teaching efficacy. NeuroRegulation, 6(3),153-169. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.6.3.1533-1

Stroebel, C. (1982). The Quieting Reflex. New York: Putnam Pub Group. https://www.amazon.com/Qr-Quieting-Charles-M-D-Stroebel/dp/0399126570/

Thakur, P. & Pathania, A.R. (2022). Relief of dysmenorrhea – A review of different types of pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments. MaterialsToday: Proceedings.18, Part 5, 1157-1162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2021.08.207

Tsai, H. Y., Peper, E., & Lin, I. M. (2016). EEG patterns under positive/negative body postures and emotion recall tasks. NeuroRegulation, 3(1), 23-27. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.3.1.23

*Edited with the help of ChatGPT 5

Hope for menstrual cramps (dysmenorrhea) with breathing

Posted: April 22, 2023 Filed under: behavior, biofeedback, Breathing/respiration, healing, health, meditation, Pain/discomfort, posture, relaxation, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: dysmenorrhea, Imagery, menstrual cramps, stroking, visualization 6 CommentsAdapted from: Peper, E., Chen, S., Heinz, N., & Harvey, R. (2023). Hope for menstrual cramps (dysmenorrhea) with breathing. Biofeedback, 51(2), 44–51. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-51.2.04; Republished in Townsend E-Letter – 18 November, 2023 https://www.townsendletter.com/e-letter-22-breath-affects-stress-and-menstrual-cramps/ Google NotebookLM generated podcast:

“I have always had extremely painful periods. They would get so painful that I would have to call in sick and take some time off from school. I have been to many doctors and medical professionals, and they told me there is nothing I could do. I am currently on birth control, and I still get some relief from the menstrual pain, but it would mess up my moods. I tried to do the diaphragmatic breathing so that I would be able to continue my life as a normal woman. And to my surprise it worked. I was simply blown away with how well it works. I have almost no menstrual pain, and I wouldn’t bloat so much after the diaphragmatic breathing.” -22 year old student

Each semester numerous students report that their cramps and dysmenorrhea symptoms decrease or disappear during the semester when they implement the relaxation and breathing practices that are taught in the semester long Holistic Health class. Given that so many young women suffer from dysmenorrhea, many young women could benefit by using this integrated approach as the first self-care intervention before relying on pain reducing medications or hormones to reduce pain or inhibit menstruation. Another 28-year-old student reported:

“Historically, my menstrual cramps have always required ibuprofen to avoid becoming distracting. After this class, I started using diaphragmatic breath after pain started for some relief. True benefit came when I started breathing at the first sign of discomfort. I have not had to use any pain medication since incorporating diaphragmatic breath work.”

This report describes students practicing self-regulation and effortless breathing to reduce stress symptoms, explores possible mechanisms of action, and suggests a protocol for reducing symptoms of menstrual cramps. Watch the short video how diaphragmatic breathing eliminated recurrent severe dysmenorrhea (pain and discomfort associated with menstruation).

Background: What is dysmenorrhea?

Dysmenorrhea is one of the most common conditions experienced by women during menstruation and affects more than half of all women who menstruate (Armour et al., 2019). Most commonly dysmenorrhea is defined by painful cramps in the lower abdomen often accompanied by pelvic pain that starts either a couple days before or at the start of menses. Symptoms also increase with stress (Wang et al., 2003) with pain symptoms usually decreasing in severity as women get older and, after pregnancy.

Economic cost of dysmenorrhea

Dysmenorrhea can significantly interfere with a women’s ability to be productive in their occupation and/or their education. It is “one of the leading causes of absenteeism from school or work, translating to a loss of 600 million hours per year, with an annual loss of $2 billion in the United States” (Itani et al, 2022). For students, dysmenorrhea has a substantial detrimental influence on academic achievement in high school and college (Thakur & Pathania, 2022). Despite the frequent occurrence and negative impact in women’s lives, many young women struggle without seeking or having access to medical advice or, without exploring non-pharmacological self-care approaches (Itani et al, 2022).

Treatment

The most common pharmacological treatments for dysmenorrhea are nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (e.g., Ibuprofen, Aspirin, and Naproxen Sodium) along with hormonal contraceptives. NSAIDs act by preventing the action of cyclooxygenase which prevents the production of prostaglandins. Itani et al (2022) suggested that prostaglandin production mechanisms may be responsible for the disorder. Hormonal contraceptives also prevent the production of prostaglandins by suppressing ovulation and endometrial proliferation.

The pharmacological approach is predominantly based upon the model that increased discomfort appears to be due to an increase in intrauterine secretion of prostaglandins F2α and E2 that may be responsible for the pain that defines this condition (Itani et al, 2022). Pharmaceuticals which influence the presence of prostaglandins do not cure the cause but mainly treat the symptoms.

Treatment with medications has drawbacks. For example, NSAIDs are associated with adverse gastrointestinal and neurological effects and also are not effective in preventing pain in everyone (Vonkeman & van de Laar, 2010). Hormonal contraceptives also have the possibility of adverse side effects (ASPH, 2023). Acetaminophen is another commonly used treatment; however, it is less effective than other NSAID treatments.

Self-regulation strategies to reduce stress and influence dysmenorrhea

Common non-pharmacological treatments include topical heat application and exercise. Both non-medication approaches can be effective in reducing the severity of pain. According to Itani et al. (2022), the success of integrative holistic health treatments can be attributed to “several mechanisms, including increasing pelvic blood supply, inhibiting uterine contractions, stimulating the release of endorphins and serotonin, and altering the ability to receive and perceive pain signals.”

Although less commonly used, self-regulation strategies can significantly reduce stress levels associated menstrual discomfort as well as reduce symptoms. More importantly, they do not have adverse side effects, but the effectiveness of the intervention varies depending on the individual.

- Autogenic Training (AT), is a hundred year old treatment approach developed by the German psychiatrist Johannes Heinrich Schultz that involves three 15 minute daily practice of sessions, resulted in a 40 to 70 percent decrease of symptoms in patient suffering from primary and secondary dysmenorrhea (Luthe & Schultz, 1969). In a well- controlled PhD dissertation, Heczey (1978) compared autogenic training taught individually, autogenic training taught in a group, autogenic training plus vaginal temperature training and a no treatment control in a randomized controlled study. All treatment groups except the control group reported a decrease in symptoms and the most success was with the combined autogenic training and vaginal temperature training in which the subjects’ vaginal temperature increased by .27 F degrees.

- Progressive muscle relaxation developed by Edmund Jacobson in the 1920s and imagery are effective treatments for dysmenorrhea (Aldinda et al., 2022; Chesney & Tasto, 1975; Çelik, 2021; Jacobson, 1938; Proctor et al., 2007).

- Rhythmic abdominal massage as compared to non-treatment reduces dysmenorrhea symptoms (Suryantini, 2022; Vagedes et al., 2019):

- Biofeedback strategies such as frontalis electromyography feedback (EMG) and peripheral temperature training (Hart, Mathisen, & Prater, 1981); trapezius EMG training (Balick et al, 1982); lower abdominal EMG feedback training and relaxation (Bennink, Hulst, & Benthem, 1982); and integrated temperature feedback and autogenic training (Dietvorts & Osborne, 1978) all successfully reduced the symptoms of dysmenorrhea.

- Breathing relaxation for 5 to 30 minutes resulted in a decrease in pain or the pain totally disappeared in adolescents (Hidayatunnafiah et al., 2022). While slow deep breathing in combination with abdominal massage is more effective than applying hot compresses (Ariani et al., 2020). Slow pranayama (Nadi Shodhan) breathing the quality of life and pain scores improved as compared to fast pranayama (Kapalbhati) breathing and improved quality of life and reduces absenteeism and stress levels (Ganesh et al. 2015). When students are taught slow diaphragmatic breathing, many report a reduction in symptoms compared to the controls (Bier et al., 2005).

Observations from Integrated stress management program

This study reports on changes in dysmenorrhea symptoms by students enrolled in a University Holistic Health class that included homework assignment for practicing stress awareness, dynamic relaxation, and breathing with imagery.

Respondents: 32 college women, average age 24.0 years (S.D. 4.5 years)

Procedure: Students were enrolled in a three-unit class in which they were assigned daily home practices which changed each week as described in the book, Make Health Happen (Peper, Gibney & Holt, 2002). The first five weeks consisted of the following sequence: Week 1 focused on monitoring one’s reactions to stressor; week 2 consisted of daily practice for 30 minutes of a modified progressive relaxation and becoming aware of bracing and reducing the bracing during the day; Week 3 consisted of practicing slow diaphragmatic breathing for 30 minutes a day and during the day becoming aware of either breath holding or shallow chest breath and then use that awareness as cue to shift to lower slower diaphragmatic breathing; week 4 focused on evoking a memory of wholeness and relaxing; and week 5 focused on learning peripheral hand warming.

During the class, students observed lectures about stress and holistic health and met in small groups to discuss their self-regulation experiences. During the class discussion, some women discussed postures and practices that were beneficial when experiencing menstrual discomfort, such as breathing slowly while lying on their back, focusing on slow abdominal awareness in which their abdomen expanded during inhalation and contracted during exhalation. While exhaling they focused on imagining a flow of air initially going through their arms and then through their abdomen, down their legs and out their feet. This kinesthetic feeling was enhanced by first massaging down the arm while exhaling and then massaging down their abdomen and down their thighs when exhaling. In most cases, the women also experienced that their hands and feet warmed. In addition, they were asked to shift to slower diaphragmatic breathing whenever they observed themselves gasping, shallow breathing or holding their breath. After five weeks, the students filled out a short assessment questionnaire in which they rated the change in dysmenorrhea symptoms since the beginning of the class.

Results.

About two-thirds of all respondents reported a decrease in overall discomfort symptoms. In addition to any ‘treatment as usual’ (TAU) strategies already being used (e.g. medications or other treatments such as NSAIDs or birth control pills), 91% (20 out 22 women) who reported experiencing dysmenorrhea reported a decrease in symptoms when they practiced the self-regulation and diaphragmatic breathing techniques as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Self-report in dysmenorrhea symptoms after 5 weeks.

Discussion

Many students reported that their symptoms were significantly reduced and they could be more productive. Generally, the more they practiced the relaxation and breathing self-regulation skills, the more they experienced a decrease in symptoms. The limitation of this report is that it is an observational study; however, the findings are similar to those reported by earlier self-care and biofeedback approaches. This suggests that women should be taught the following simple self-regulation strategies as the first intervention to prevent and when they experience dysmenorrhea symptoms.

Why would breathing reduce dysmenorrhea?

Many women respond by ‘curling up’ a natural protective defense response when they experience symptoms. This protective posture increases abdominal and pelvic muscle tension, inhibits lymph and blood flow circulation, increases shallow breathing rate, and decreases heart rate variability. Intentionally relaxing the abdomen with slow lower breathing when lying down with the legs extended is often the first step in reducing discomfort.

By focusing on diaphragmatic breathing with relaxing imagery, it is possible to restore abdominal expansion during inhalation and slight constriction during exhalation. This dynamic breathing while lying supine would enhance abdominal blood and lymph circulation as well as muscle relaxation (Peper et al., 2016). While practicing, participants were asked to wear looser clothing that did not constrict the waist to allow their abdomen to expand during inhalation; since, waist constriction by clothing (designer jean syndrome) interferes with abdominal expansion. Allowing the abdomen to fully extend also increased acceptance of self, that it was okay to let the abdomen expand instead of holding it in protectively. The symptoms were reduced most likley by a combination of the following factors.

- Abdominal movement is facilitated during the breathing cycle. This means reducing the factors that prevent the abdomen expanding during inhalation or constricting during exhalation (Peper et al., 2016).

- Eliminate‘Designer jean syndrome’ (the modern girdle). Increase the expansion of your abdomen by loosening the waist belt, tight pants or slimming underwear (MacHose & Peper, 1991).

- Accept yourself as you are. Allow your stomach to expand without pulling it in.

- Free up learned disuse: Allow the abdomen to expand and constrict instead of inhibiting movement to avoid pain that occurred following a prior abdominal injury/surgery (e.g., hernia surgery, appendectomy, or cesarean operation), abdominal pain (e.g., irritable bowel syndrome, recurrent abdominal pain, ulcers, or acid reflux), pelvic floor pain (e.g., pelvic floor pain, pelvic girdle pain, vulvodynia, or sexual abuse).

- The ‘defense response’ is reduced. Many students described that they often would curl up in a protective defense posture when experiencing menstrual cramps. This protective defense posture would maintain pelvic floor muscle contractions and inhibit blood and lymph flow in the abdomen, increase shallow rapid thoracic breathing and decrease pCO2 which would increase vasoconstriction and muscle constriction (Peper et al., 2015; Peper et al., 2016). By having the participant lie relaxed in a supine position with their legs extended while practicing slow abdominal breathing, the pelvic floor and abdominal wall muscles can relax and thereby increase abdominal blood and lymph circulation and parasympathetic activity. The posture of lying down implies feeling safe which is a state that facilitates healing.

- The pain/fear cycle is interrupted. The dysmenorrhea symptoms may trigger more symptoms because the person anticipates and reacts to the discomfort. The breathing and especially the kinesthetic imagery where the attention goes from the abdomen and area of discomfort to down the legs and out the feet acts as a distraction technique (not focusing on the discomfort).

- Support sympathetic-parasympathetic balance. The slow breathing and kinesthetic imagery usually increases heart rate variability and hand and feet temperature and supports sympathetic parasympathetic balance.

- Interrupt the classical conditioned response of the defense reaction. For some young girls, the first menstruation occurred unexpectedly. All of a sudden, they bled from down below without any understanding of what is going on which could be traumatic. For some this could be a defense reaction and a single trial condition response (somatic cues of the beginning of menstruation triggers the defense reaction). Thus, when the girl later experiences the initial sensations of menstruation, the automatic conditioned response causes her to tense and curl up which would amplify the discomfort. Informal interviews with women suggests that those who experienced their first menstruation experience as shameful, unexpected, or traumatic (“I thought I was dying”) thereafter framed their menstruation negatively. They also tended to report significantly more symptoms than those women who reported experiencing their first menstruation positively as a conformation that they have now entered womanhood.

How to integrate self-care to reduce dysmenorrhea

Be sure to consult your healthcare provider to rule out treatable underlying conditions before implementing learning effortless diaphragmatic breathing.

- Allow the abdomen to expand during inhalation and become smaller during exhalation. This often means, loosen belt and waist constriction, acceptance of allowing the stomach to be larger and reversing learned disuse and protective response caused by stress.

- Master diaphragmatic breathing (see: Peper & Tibbetts, 1994 and the blogs listed at the end of the article).

- Practice slow effortless diaphragmatic breathing lying down with warm water bottle on stomach in a place that feels safe.

- Include kinesthetic imagery as you breathe at about 6 breaths per minute (e.g. slowly inhale for 4 or 5 seconds and then exhale for 5 or 6 seconds, exhaling slightly longer than inhaling). Imaging that when you exhale you can sense healing energy flow through your abdomen, down the legs and out the feet.

- If possible, integrate actual touch with the exhalation can provide added benefit. Have a partner first stroke or massage down the arms from the shoulder to your fingertips as you exhale and, then on during next exhalation stroke gently from your abdomen down your legs and feet. Stroke in rhythm the exhalation.

- Exhale slowly and shift to slow and soft diaphragmatic breathing each time you become aware of neck and shoulder tension, breath holding, shallow breathing, or anticipating stressful situations. At the same time imagine /sense when exhaling a streaming going through the abdomen and out the feet when exhaling. Do this many times during the day.

- Practice and apply general stress reduction skills into daily life since stress can increase symptoms. Anticipate when stressful event could occur and implement stress reducing strategies.

- Be respectful of the biological changes that are part of the menstrual cycle. In some cases adjust your pace and slow down a bit during the week of the menstrual cycle; since, the body needs time to rest and regenerate. Be sure to get adequate amount of rest, hydration, and nutrition to optimize health.

- Use self-healing imagery and language to transform negative association with menstruation to positive associations (e.g., “curse” to confirmation “I am healthy”).

Conclusion

There are many ways to alleviate dysmenorrhea. Women can find ways to anticipate and empower themselves by practicing stress reduction, wearing more comfortable clothing, using heat compression, practicing daily diaphragmatic breathing techniques, visualizing relaxed muscles, and positive perception towards menstrual cycles to reduce the symptoms of dysmenorrhea. These self-regulation methods should be taught as a first level intervention to all young women starting in middle and junior high school so that they are better prepared for the changes that occur as they age.

“I have been practicing the breathing techniques for two weeks prior and I also noticed my muscles, in general, are more relaxed. Of course, I also avoided the skinny jeans that I like to wear and it definitely helped.

I have experienced a 90% improvement from my normal discomfort. I was still tired – and needed more rest and sleep but haven’t experienced any “terrible” physical discomfort. Still occasionally had some sharp pains or bloating but minor discomfort, unlike some days when I am bedridden and unable to move for half a day. – and this was a very positive experience for me “ — Singing Chen (Chen, 2023)

Useful blogs to learn diaphragmatic breathing

References

Aldinda, T. W., Sumarni, S., Mulyantoro, D. K., & Azam, M. (2022). Progressive muscle relaxation application (PURE App) for dysmenorrhea. Medisains Jurnal IlmiahLlmiah LLmu-LLmu Keshatan, 20(2), 52-57. https://doi.org/10.30595/medisains.v20i2.14351

Ariani, D., Hartiningsih, S.S., Sabarudin, U. Dane, S. (2020). The effectiveness of combination effleurage massage and slow deep breathing technique to decrease menstrual pain in university students. Journal of Research in Medical and Dental Science, 8(3), 79-84. https://www.jrmds.in/articles/the-effectiveness-of-combination-effleurage-massage-and-slow-deep-breathing-technique-to-decrease-menstrual-pain-in-university-stu-53607.html

Armour, M., Parry, K., Manohar, N., Holmes, K., Ferfolja, T., Curry, C., MacMillan, F., & Smith, C. A. (2019). The prevalence and academic impact of dysmenorrhea in 21,573 young women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of women’s health, 28(8), 1161-1171.https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2018.7615

ASPH. (2023). Estrogen and Progestin (Oral Contraceptives). MedlinePlus. Assessed March 3, 2023. https://medlineplus.gov/druginfo/meds/a601050.html

Balick, L., Elfner, L., May. J., Moore, J.D. (1982). Biofeedback treatment of dysmenorrhea. Biofeedback Self Regul, 7(4), 499-520. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00998890

Bennink, C.D., Hulst, L.L. & Benthem, J.A. (1982). The effects of EMG biofeedback and relaxation training on primary dysmenorrhea. J Behav Med, 5(3), 329-341.https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00846160

Bier, M., Kazarian, D. & Peper, E. (2005). Reducing PMS through biofeedback and breathing. Poster presentation at the 36th Annual Meeting of the Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. Abstract published in: Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. 30 (4), 411-412.

Çelik, A.S. & Apay, S.E. (2021). Effect of progressive relaxation exercises on primary dysmenorrhea in Turkish students: A randomized prospective controlled trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract, Feb 42,101280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2020.101280

Chen, S. (2023). Diaphragmatic breathing reduces dysmenorrhea symptoms-a testimonial. YouTube. Accessed March 3, 2023. https://youtu.be/E45iGymVe3U

De Sanctis, V., Soliman, A., Bernasconi, S., Bianchin, L., Bona, G., Bozzola, M., Buzi, F., De Sanctis, C., Tonini, G., Rigon, F., & Perissinotto, E. (2015). Primary Dysmenorrhea in Adolescents: Prevalence, Impact and Recent Knowledge. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 13(2), 512-20. PMID: 26841639. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26841639/

De Sanctis, V., Soliman, A. T., Daar, S., Di Maio, S., Elalaily, R., Fiscina, B., & Kattamis, C. (2020). Prevalence, attitude and practice of self-medication among adolescents and the paradigm of dysmenorrhea self-care management in different countries. Acta Bio Medica: Atenei Parmensis, 91(1), 182. https://doi.org/10.23750/abm.v91i1.9242

Dietvorst, T.F. & Osborne, D. (1978). Biofeedback-Assisted Relaxation Training

for Primary Dysmenorrhea: A Case Study. Biofeedback and Self-Regulation, 3(3), 301-305. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00999298

Chesney, M. A., & Tasto, D. L. (1975).The effectiveness of behavior modification with spasmodic and congestive dysmenorrhea. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 13, 245-253. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(75)90029-7

Ganesh, B.R., Donde, M.P., & Hegde, A.R. (2015). Comparative study on effect of slow and fast phased pranayama on quality of life and pain in physiotherapy girls with primary dysmenorrhea: Randomize clinical trial. International Journal of Physiotherapy and Research, 3(2), 960-965. https://doi.org/10.16965/ijpr.2015.115

Hart, A.D., Mathisen, K.S. & Prater, J.S. A comparison of skin temperature and EMG training for primary dysmenorrhea. Biofeedback and Self-Regulation 6, 367–373 (1981). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01000661

Heczey, M. D. (1978). Effects of biofeedback and autogenic training on menstrual experiences: relationship among anxiety, locus of control and dysmenorrhea. City University of New York ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 7805763. https://www.proquest.com/openview/088e0d68511b5b59de1fa92dec832cc8/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y

Hidayatunnafiah, F., Mualifah, L., Moebari, M., & Iswantiningsih, E. (2022). The Effect of Relaxation Techniques in Reducing Dysmenorrhea in Adolescents. The International Virtual Conference on Nursing. in The International Virtual Conference on Nursing, KnE Life Sciences, 473–480. https://doi.org/10.18502/kls.v7i2.10344

Itani, R., Soubra, L., Karout, S., Rahme, D., Karout, L., & Khojah, H.M.J. (2022). Primary Dysmenorrhea: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment Updates. Korean J Fam Med, 43(2), 101-108. https://doi.org/10.4082/kjfm.21.0103

Jacobson, E. (1938). Progressive Relaxation: A Physiological and Clinical Investigation of Muscular States and Their Significance in Psychology and Medical Practice. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Ju, H., Jones, M., & Mishra, G. (2014). The prevalence and risk factors of dysmenorrhea. Epidemiol Rev, 36, 104-13. https://doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxt009

Karout, S., Soubra, L., Rahme, D. et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and management practices of primary dysmenorrhea among young females. BMC Women’s Health 21, 392 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-021-01532-w

Iacovides, S., Avidon,I, & Baker, F.C. (2015).What we know about primary dysmenorrhea today: a critical review, Human Reproduction Update, 21(6), 762–778. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmv039

Luthe, W. & Schultz, J.H. (1969). Autogenic Therapy, Volume II Medical Applications. New York: Grune & Stratton, pp144-148.

MacHose, M. & Peper, E. (1991). The effect of clothing on inhalation volume. Biofeedback and Self-Regulation, 16(3), 261–265. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01000020

Peper, E., Booiman, A., Lin, I-M, Harvey, R., & Mitose, J. (2016). Abdominal SEMG Feedback for Diaphragmatic Breathing: A Methodological Note. Biofeedback. 44(1), 42-49. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-44.1.03

Peper, E., Gibney, H. K. & Holt, C. (2002). Make Health Happen. Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall-Hunt. ISBN: 978-0787293314 https://he.kendallhunt.com/make-health-happen

Peper, E., Gilbert, C.D., Harvey, R. & Lin, I-M. (2015). Did you ask about abdominal surgery or injury? A learned disuse risk factor for breathing dysfunction. Biofeedback. 34(4), 173-179. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-43.4.06

Peper, E. & Tibbetts, V. (1994). Effortless diaphragmatic breathing. Physical Therapy Products. 6(2), 67-71. Also in: Electromyography: Applications in Physical Therapy. Montreal: Thought Technology Ltd. https://biofeedbackhealth.files.wordpress.com/2011/01/peper-and-tibbets-effortless-diaphragmatic.pdf

Proctor, M. & Farquhar, C. (2006). Diagnosis and management of dysmenorrhoea. BMJ. 13, 332(7550), 1134-8. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.332.7550

Proctor, M.L, Murphy, P.A., Pattison, H.M., Suckling, J., & Farquhar, C.M. (2007). Behavioural interventions for primary and secondary dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, (3):CD002248. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002248.pub3

Suryantini, N. P. (2022). Effleurage Massage: Alternative Non-Pharmacological Therapy in Decreasing Dysmenorrhea Pain. Women, Midwives and Midwifery, 2(3), 41-50. https://wmmjournal.org/index.php/wmm/article/view/71/45

Thakur, P. & Pathania, A.R. (2022). Relief of dysmenorrhea – A review of different types of pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments. MaterialsToday: Proceedings.18, Part 5, 1157-1162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2021.08.207

Vagedes, J., Fazeli, A., Boening, A., Helmert, E., Berger, B. & Martin, D. (2019). Efficacy of rhythmical massage in comparison to heart rate variability biofeedback in patients with dysmenorrhea—A randomized, controlled trial. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 42, 438-444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2018.11.009

Vonkeman, H.E. & van de Laar, M,A. (2010). Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: adverse effects and their prevention, Semin Arthritis Rheum, 39(4), 294-312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2008.08.001

Wang, L., Wand, X., Wang, W., Chen, C. Ronnennberg, A.G., Guang, W. Huang, A. Fang, Z. Zang, T., Wang, L. & Xu, X. (2003).Stress and dysmenorrhoea: a population based prospective study. Occupation and Environmental Medicine, 61(12). http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/oem.2003.012302

Reduce anxiety

Posted: March 23, 2022 Filed under: behavior, Breathing/respiration, CBT, cognitive behavior therapy, digital devices, education, emotions, health, mindfulness, posture, relaxation, self-healing, stress management | Tags: anxiety, concentration, insomnia, menstrual cramps, pain 3 Comments

The purpose of this blog is to describe how a university class that incorporated structured self-experience practices reduced self-reported anxiety symptoms (Peper, Harvey, Cuellar, & Membrila, 2022). This approach is different from a clinical treatment approach as it focused on empowerment and mastery learning (Peper, Miceli, & Harvey, 2016).

As a result of my practice, I felt my anxiety and my menstrual cramps decrease. — College senior

When I changed back to slower diaphragmatic breathin, I was more aware of my negative emotions and I was able to reduce the stress and anxiety I was feeling with the deep diaphragmatic breathing.– College junior

Background

More than half of college students now report anxiety (Coakley et al., 2021). In our recent survey during the first day of the spring semester class, 59% of the students reported feeling tired, dreading their day, being distracted, lacking mental clarity and had difficulty concentrating.

Before the COVID pandemic nearly one-third of students had or developed moderate or severe anxiety or depression while being at college (Adams et al., 2021. The pandemic accelerated a trend of increasing anxiety that was already occurring. “The prevalence of major depressive disorder among graduate and professional students is two times higher in 2020 compared to 2019 and the prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder is 1.5 times higher than in 2019” As reported by Chirikov et al (2020) from the UC Berkeley SERU Consortium Reports.

This increase in anxiety has both short and long term performance and health consequences. Severe anxiety reduces cognitive functioning and is a risk factor for early dementia (Bierman et al., 2005; Richmond-Rakerd et al, 2022). It also increases the risk for asthma, arthritis, back/neck problems, chronic headache, diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, pain, obesity and ulcer (Bhattacharya et al., 2014; Kang et al, 2017).

The most commonly used treatment for anxiety are pharmaceutical and cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) (Kaczkurkin & Foa, 2015). The anti-anxiety drugs are usually benzodiazepines (e.g., alprazolam (Xanax), clonazepam (Klonopin), chlordiazepoxide (Librium), diazepam (Valium) and lorazepam (Ativan). Although these drugs they may reduce anxiety, they have numerous side effects such as drowsiness, irritability, dizziness, memory and attention problems, and physical dependence (Shri, 2012; Crane, 2013).

Cognitive behavior therapy techniques based upon the assumption that anxiety is primarily a disorder in thinking which then causes the symptoms and behaviors associated with anxiety. Thus, the primary treatment intervention focuses on changing thoughts.

Given the significant increase in anxiety and the potential long term negative health risks, there is need to provide educational strategies to empower students to prevent and reduce their anxiety. A holistic approach is one that assumes that body and mind are one and that soma/body, emotions and thoughts interchangeably affect the development of anxiety. Initially in our research, Peper, Lin, Harvey & Perez (2017) reported that it was easier to access hopeless, helpless, powerless and defeated memories in a slouched position than an upright position and it was easier to access empowering positive memories in an upright position than a slouched position. Our research on transforming hopeless, helpless, depressive thought to empowering thoughts, Peper, Harvey & Hamiel (2019) found that it was much more effective if the person first shifts to an upright posture, then begins slow diaphragmatic breathing and finally reframes their negative to empowering/positive thoughts. Participants were able to reframe stressful memories much more easily when in an upright posture compared to a slouched posture and reported a significant reduction in negative thoughts, anxiety (they also reported a significant decrease in negative thoughts, anxiety and tension as compared to those attempting to just change their thoughts).

The strategies to reduce anxiety focus on breathing and posture change. At the same time there are many other factors that may contribute the onset or maintenance of anxiety such as social isolation, economic insecurity, etc. In addition, low glucose levels can increase irritability and may lower the threshold of experiencing anxiety or impulsive behavior (Barr, Peper, & Swatzyna, 2019; Brad et al, 2014). This is often labeled as being “hangry” (MacCormack & Lindquist, 2019). Thus, by changing a high glycemic diet to a low glycemic diet may reduce the somatic discomfort (which can be interpreted as anxiety) triggered by low glucose levels. In addition, people are also sitting more and more in front of screens. In this position, they tend to breathe quicker and more shallowly in their chest.

Shallow rapid breathing tends to reduce pCO2 and contributes to subclinical hyperventilation which could be experienced as anxiety (Lum, 1981; Wilhelm et al., 2001; Du Pasquier et al, 2020). Experimentally, the feeling of anxiety can rapidly be evoked by instructing a person to sequentially exhale about 70 % of the inhaled air continuously for 30 seconds. After 30 seconds, most participants reported a significant increase in anxiety (Peper & MacHose, 1993). Thus, the combination of sitting, shallow breathing and increased stress from the pandemic are all cofactors that may contribute to the self-reported increase in anxiety.

To reduce anxiety and discomfort, McGrady and Moss (2013) suggested that self-regulation and stress management approaches be offered as the initial treatment/teaching strategy in health care instead of medication. One of the useful approaches to reduce sympathetic arousal and optimize health is breathing awareness and retraining (Gilbert, 2003).

Stress management as part of a university holistic health class

Every semester since 1976, up to 180 undergraduates have enrolled in a three-unit Holistic Health class on stress management and self-healing (Klein & Peper, 2013). Students in the class are assigned self-healing projects using techniques that focus on awareness of stress, dynamic regeneration, stress reduction imagery for healing, and other behavioral change techniques adapted from the book, Make Health Happen (Peper, Gibney & Holt, 2002).

82% of students self-reported that they were ‘mostly successful’ in achieving their self-healing goals. Students have consistently reported achieving positive benefits such as increasing physical fitness, changing diets, reducing depression, anxiety, and pain, eliminating eczema, and even reducing substance abuse (Peper et al., 2003; Bier et al., 2005; Peper et al., 2014).

This assessment reports how students’ anxiety decreased after five weeks of daily practice. The students filled out an anonymous survey in which they rated the change in their discomfort after practicing effortless diaphragmatic breathing. More than 70% of the students reported a decrease in anxiety. In addition, they reported decreases in symptoms of stress, neck and shoulder pain as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Self-report of decrease in symptoms after practice diaphragmatic breathing for a week.

In comparing the self-reported responses of the students in the holistic health class to those of the control group (N=12), the students in the holistic health class reported a significant decrease in symptoms since the beginning of the semester as compared to the control group as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Change in self-reported symptoms after 6 weeks of practice the integrated holistic health skills as compared to the control group who did not practice these skills.

Changes in symptoms Most students also reported an increase in mental clarity and concentration that improved their study habits. As one student noted: Now that I breathe properly, I have less mental fog and feel less overwhelmed and more relaxed. My shoulders don’t feel tense, and my muscles are not as achy at the end of the day.

The teaching components for the first five weeks included a focus on the psychobiology of stress, the role of posture, and psychophysiology of respiration. The class included didactic presentations and daily self-practice

Lecture content

- Diadactic presentation on the physiology of stress and how posture impacts health.

- Self-observation of stress reactions; energy drain/energy gain and learning dynamic relaxation.

- Short experiential practices so that the student can experience how slouched posture allows easier access to helpless, hopeless, powerless and defeated memories.

- Short experiential breathing practices to show how breathing holding occurs and how 70% exhalation within 30 seconds increases anxiety.

- Didactic presentation on the physiology of breathing and how a constricted waist tends to have the person breathe high in their chest (the cause of neurasthemia) and how the fight/flight response triggers chest breathing, breath holding and/or shallow breathing.

- Explanation and practice of diaphragmatic breathing.

Daily self-practice

Students were assigned weekly daily self-practices which included both skill mastery by practicing for 20 minutes as well and implementing the skill during their daily life. They then recorded their experiences after the practice. At the end of the week, they reviewed their own log of week and summarized their observations (benefits, difficulties) and then met in small groups to discuss their experiences and extract common themes. These daily practices consisted of:

- Awareness of stress. Monitoring how they reacted to daily stressor

- Practicing dynamic relaxation. Students practiced for 20 minutes a modified progressive relaxation exercise and observed and inhibit bracing pattern

- Changing energy drain and energy gains. Students observed what events reduced or increased their subjective energy and implemented changes in their behavior to decrease events that reduced their energy and increased behaviors that increase their enery

- Creating a memory of wholeness practice

- Practicing effortless breathing. Students practiced slowly diaphragmatic abdominal breathing for 20 minutes per day and each time they become aware of dysfunctional breathing (breath holding, shallow chest breathing, gasping) during the day, they would shift to slower diaphragmatic breathing.

Discussion

Almost all students were surprised how beneficial these practices were to reduce their anxiety and symptoms. Generally, the more the students would interrupt their personal stress responses during the day by shifting to diaphragmatic breathing the more did they experience success. We hypothesize that some of the following factors contributed to the students’ improvement.

- Learning through self-mastery as an education approach versus clinical treatment.

- Generalizing the skills into daily life and activities. Practicing the skills during the day in which the cue of a stress reaction triggered the person to breathe slowly. The breathing would reduce the sympathetic activation.

- Interrupting escalating sympathetic arousal. Responding with an intervention reduced the sense of being overwhelmed and unable to cope by the participant by taking charge and performing an active task.

- Redirecting attention and thoughts away from the anxiety triggers to a positive task.

- Increasing heart rate variability. Through slow breathing heart rate variability increased which enhanced sympathetic parasympathetic balance.

- Reducing subclinical hyperventilation by breathing slower and thereby increasing pC02.

- Increasing social support by meeting in small groups. The class discussion group normalized the anxiety experiences.

- Providing hope. The class lectures, assigned readings and videos provide hope; since, it included reports how other students had reversed their chronic disorders such as irritable bowel disease, acid reflux, psoriasis with behavioral interventions.

Although the study lacked a control group and is only based upon self-report, it offers an economical non-pharmaceutical approach to reduce anxiety. These stress management strategies may not resolve anxiety for everyone. Nevertheless, we recommend that schools implement this approach as the first education intervention to improve health in which students are taught about stress management, learn and practice relaxation and diaphragmatic breathing and then practice these skills during the day whenever they experience stress or dysfunctional breathing.

I noticed that breathing helped tremendously with my anxiety. I was able to feel okay without having that dreadful feeling stay in my chest and I felt it escape in my exhales. I also felt that I was able to breathe deeper and relax better altogether. It was therapeutic, I felt more present, aware, and energized.

See the following blogs for detailed breathing instructions

References

Adams. K.L., Saunders KE, Keown-Stoneman CDG, et al. (2021). Mental health trajectories in undergraduate students over the first year of university: a longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open 2021; 11:e047393. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047393

Barr, E. A., Peper, E. & Swatzyna, R.J. (2019). Slouched Posture, Sleep Deprivation, and Mood Disorders: Interconnection and Modulation by Theta Brain Waves. Neuroregulation, 6(4), 181–189 https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.6.41.181

Bhattacharya, R., Shen, C. & Sambamoorthi, U. (2014). Excess risk of chronic physical conditions associated with depression and anxiety. BMC Psychiatry 14, 10 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-10

Bier, M., Peper, E., & Burke, A. (2005). Integrated stress management with ‘Make Health Happen: Measuring the impact through a 5-month follow-up. Poster presentation at the 36th Annual Meeting of the Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. Abstract published in: Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 30(4), 400. https://biofeedbackhealth.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/2005-aapb-make-health-happen-bier-peper-burke-gibney3-12-05-rev.pdf

Bierman, E.J.M., Comijs, H.C. , Jonker, C. & Beekman, A.T.F. (2005). Effects of Anxiety Versus Depression on Cognition in Later Life. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry,13(8), 686-693, https://doi.org/10.1097/00019442-200508000-00007.

Brad, J., Bushman, C., DeWall, N., Pond, R.S., &. Hanus, M.D. (2014).. Low glucose relates to greater aggression in married couples. PNAS, April 14, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1400619111

Chirikov, I., Soria, K. M, Horgos, B., & Jones-White, D. (2020). Undergraduate and Graduate Students’ Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic. UC Berkeley: Center for Studies in Higher Education. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/80k5d5hw

Coakley, K.E., Le, H., Silva, S.R. et al. Anxiety is associated with appetitive traits in university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nutr J 20, 45 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-021-00701-9

Crane,E.H. (2013).Highlights of the 2011 Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) Findings on Drug-Related Emergency Department Visits. 2013 Feb 22. In: The CBHSQ Report. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); 2013-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK384680/

Du Pasquier, D., Fellrath, J.M., & Sauty, A. (2020). Hyperventilation syndrome and dysfunctional breathing: update. Revue Medicale Suisse, 16(698), 1243-1249. https://europepmc.org/article/med/32558453

Gilbert C. Clinical Applications of Breathing Regulation: Beyond Anxiety Management. Behavior Modification. 2003;27(5):692-709. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445503256322

Kaczkurkin, A.N. & Foa, E.B. (2015). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders: an update on the empirical evidence. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 17(3):337-46. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2015.17.3/akaczkurkin

Kang, H. J., Bae, K. Y., Kim, S. W., Shin, H. Y., Shin, I. S., Yoon, J. S., & Kim, J. M. (2017). Impact of Anxiety and Depression on Physical Health Condition and Disability in an Elderly Korean Population. Psychiatry investigation, 14(3), 240–248. https://doi.org/10.4306/pi.2017.14.3.240

Klein, A. & Peper, W. (2013). There is Hope: Autogenic Biofeedback Training for the Treatment of Psoriasis. Biofeedback, 41(4), 194–201. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-41.4.01

Lum, L. C. (1981). Hyperventilation and anxiety state. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 74(1), 1-4. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/014107688107400101

MacCormack, J. K., & Lindquist, K. A. (2019). Feeling hangry? When hunger is conceptualized as emotion. Emotion, 19(2), 301–319. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000422

McGrady, A. & Moss, D. (2013). Pathways to illness, pathways to health. New York: Springer. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-1-4419-1379-1

Peper, E., Gibney, K.H., & Holt, C.F. (2002). Make health happen: Training yourself to create wellness. Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company. https://he.kendallhunt.com/make-health-happen

Peper, E., Harvey, R., Cuellar, Y., & Membrila, C. (2022). Reduce anxiety. NeuroRegulation, 9(2), 91–97. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.9.2.91 https://www.neuroregulation.org/article/view/22815/14575

Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Hamiel, D. (2019). Transforming thoughts with postural awareness to increase therapeutic and teaching efficacy. NeuroRegulation, 6(3),153-169. doi:10.15540/nr.6.3.1533-1 https://www.neuroregulation.org/article/view/19455/13261

Peper, E., Lin, I-M., Harvey, R., & Perez, J. (2017). How posture affects memory recall and mood. Biofeedback.45 (2), 36-41. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-45.2.01

Peper, E., Lin, I-M, Harvey, R., Gilbert, M., Gubbala, P., Ratkovich, A., & Fletcher, F. (2014). Transforming chained behaviors: Case studies of overcoming smoking, eczema and hair pulling (trichotillomania). Biofeedback, 42(4), 154-160. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-42.4.06

Peper, E., MacHose, M. (1993). Symptom prescription: Inducing anxiety by 70% exhalation. Biofeedback and Self-Regulation 18, 133–139). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00999790

Peper, E., Miceli, B., & Harvey, R. (2016). Educational Model for Self-healing: Eliminating a Chronic Migraine with Electromyography, Autogenic Training, Posture, and Mindfulness. Biofeedback, 44(3), 130–137. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-44.3.03

Peper, E., Sato-Perry, K & Gibney, K. H. (2003). Achieving Health: A 14-Session Structured Stress Management Program—Eczema as a Case Illustration. 34rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. Abstract in: Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 28(4), 308. Proceeding in: http://www.aapb.org/membersonly/articles/P39peper.pdf

Richmond-Rakerd, L.S., D’Souza, S, Milne, B.J, Caspi, A., & Moffitt, T.E. (2022). Longitudinal Associations of Mental Disorders with Dementia: 30-Year Analysis of 1.7 Million New Zealand Citizens. JAMA Psychiatry. Published online February 16, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.4377

Shri, R. (2012). Anxiety: Causes and Management. The Journal of Behavioral Science, 5(1), 100–118. Retrieved from https://so06.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/IJBS/article/view/2205

Wilhelm, F.H., Gevirtz, R., & Roth, W.T. (2001). Respiratory dysregulation in anxiety, functional cardiac, and pain disorders. Assessment, phenomenology, and treatment. Behav Modif, 25(4), 513-45. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445501254003

Breathing reduces acid reflux and dysmenorrhea discomfort

Posted: October 4, 2018 Filed under: Breathing/respiration, Pain/discomfort, posture, relaxation, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: acid reflux, dysmenorrhea, gastroesophageal reflux disease, GERD, menstrual cramps, PMS 14 CommentsPublished as: Peper, E., Mason, L., Harvey, R., Wolski, L, & Torres, J. (2020). Can acid reflux be reduced by breathing? Townsend Letters-The Examiner of Alternative Medicine, 445/446, 44-47. https://www.townsendletter.com/article/445-6-acid-reflux-reduced-by-breathing/

“Although difficult and going against my natural reaction to curl up in the response to my cramps, I stretched out on my back and breathed slowly so that my stomach got bigger with each inhalation. My menstrual pain slowly decreased and disappeared.

“For as long as I remember, I had stomach problems and when I went to doctors, they said, I had acid reflux. I was prescribed medication and nothing worked. The problem of acid reflux got really bad when I went to college and often interfered with my social activities. After learning diaphragmatic breathing so that my stomach expanded instead of my chest, I am free of my symptoms and can even eat the foods that previously triggered the acid reflux.”

In the late 19th earlier part of the 20th century many women were diagnosed with Neurasthenia. The symptoms included fatigue, anxiety, headache, fainting, light headedness, heart palpitation, high blood pressure, neuralgia and depression. It was perceived as a weakness of the nerves. Even though the diagnosis is no longer used, similar symptoms still occur and are aggravated when the abdomen is constricted with a corset or by stylish clothing (see Fig 1).

Figure 1. Wearing a corset squeezes the abdomen.

The constricted waist compromises the functions of digestion and breathing. When the person inhales, the abdomen cannot expand as the diaphragm is flattening and pushing down. Thus, the person is forced to breathe more shallowly by lifting their ribs which increases neck and shoulder tension and the risk of anxiety, heart palpitation, and fatigue. It also can contribute to abdominal discomfort since abdomen is being squeezed by the corset and forcing the abdominal organs upward. It was the reason why the room on top of stairs in the old Victorian houses was call the fainting room (Melissa, 2015).

During inhalation the diaphragm flattens and attempts to descend which increases the pressure of the abdominal content. In some cases this causes the stomach content to be pushed upward into the esophagus which could result in heart burn and acid reflux. To avoid this, health care providers often advice patients with acid reflux to sleep on a slanted bed with the head higher than their feet so that the stomach content flows downward. However, they may not teach the person to wear looser clothing that does not constrict the waist and prevent designer jean syndrome. If the clothing around the waist is loosened, then the abdomen may expand in all directions in response to the downward movement of the diaphragm during inhalation and not squeeze the stomach and thereby pushing its content upward into the esophagus.

Most people have experienced the benefits of loosening the waist when eating a large meal. The moment the stomach is given the room to spread out, you feel more comfortable. If you experienced this, ask yourself, “Could there be a long term cost of keeping my waist constricted?” A constricted waist may be as harmful to our health as having the emergency brake on while driving for a car.

We are usually unaware that shallow rapid breathing in our chest can contribute to symptoms such as anxiety, neck and shoulder tension, heart palpitations, headaches, abdominal discomfort such as heart burn, acid reflux, irritable bowel syndrome, dysmenorrhea and even reduced fertility (Peper, Mason, & Huey, 2017; Domar, Seibel, & Benson, 1990).

Assess whether you are at risk for faulty breathing

Stand up and observe what happens when you take in a big breath and then exhale. Did you feel taller when you inhaled and shorter/smaller when you exhaled?

If the answer is YES, your breathing pattern may compromise your health. Most likely when you inhaled you lifted your chest, slightly arched your back, tightened and raised your shoulders, and lifted your head up while slightly pulling the stomach in. When you exhaled, your body relaxed and collapsed downward and even the stomach may have relaxed and expanded. This is a dysfunctional breathing pattern and the opposite of a breathing pattern that supports health and regeneration as shown in figure 2.

Figure 2. Incorrect and correct breathing. Source unknown.

Observe babies, young children, dogs, and cats when they are peaceful. The abdomen is what moves during breathing. While breathing in, the abdomen expands in all 360 degrees directions and when breathing out, the abdomen constricts and comes in. Similarly when dogs or cats are lying on their sides, their stomach goes up during inhalation and goes down during exhalation.

Many people tend to breathe shallowly in their chest and have forgotten—or cannot– allow their abdomen and lower ribs to widen during inhalation (Peper et al, 2016). These factors include:

- Constriction by the modern corset called “Spanx” to slim the figure or by wearing tight fitting pants. In either case the abdominal content is pushed upward and interferes with normal healthy breathing.

- Maintaining a slim figure by pulling the abdomen (I will look fat when my stomach expands; I will suck it in).

- Avoiding post-surgical abdominal pain by inhibiting abdominal movement. Numerous patients have unknowingly learned to shallowly breathe in their chest to avoid pain at the site of the incision of the abdominal surgery such as for hernia repair or a cesarean operation. This dysfunctional breathing became the new normal unless they actively practice diaphragmatic breathing.

- Slouching as we sit or watch digital screens or look down at our cell phone.

Observe how slouching affects the space in your abdomen.

When you shift from an upright erect position to a slouched or protective position the distance between your pubic bone and the bottom of the sternum (xiphoid process) is significantly reduced.

- Tighten our abdomen to protect ourselves from pain and danger as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Erect versus collapsed posture. There is less space for the abdomen to expand in the protective collapsed position. Reproduced by permission from Clinical Somatics (http://www.clinicalsomatics.ie/).

Regardless why people breathe shallowly in their chest or avoid abdominal and lower rib movement during breathing, by re-establishing normal diaphragmatic breathing many symptoms may be reduced. Numerous students have reported that when they shift to diaphragmatic breathing which means the abdomen and lower ribs expand during inhalation and come in during exhalation as shown in Figure 4, their symptoms such as acid reflux and menstrual cramp significantly decrease.

Figure 4. Diaphragmatic breathing. Reproduced from: www.devang.house/blogs/thejob/belly-breathing-follow-your-gut.

Reduce acid reflux

A 21-year old student, who has had acid reflux (GERD-gastroesophageal reflux diseases) since age 6, observed that she only breathed in her chest and that there were no abdominal movements. When she learned and practiced slower diaphragmatic breathing which allowed her abdomen to expand naturally during inhalation and reduce in size during exhalation her symptoms decreased. The image she used was that her lungs were like a balloon located in her abdomen. To create space for the diaphragm going down, she bought larger size pants so that her abdominal could spread out instead of squeezing her stomach (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Hydraulic model who inhaling without the abdomen expanding increases pressure on the stomach and possibly cause stomach fluids to be pushed into the esophagus.

She practiced diaphragmatic breathing many times during the day. In addition, the moment she felt stressed and tightened her abdomen, she interrupted this tightening and re-established abdominal breathing. Practicing this was very challenging since she had to accept that she would still be attractive even if her stomach expanded during inhalation. She reported that within two weeks her symptom disappeared and upon a year follow-up she has had no more symptoms. In the video she describes her experiences of integrate breathing and awareness into daily life.

We have also use this similar approach to successfully overcome irritable bowel syndrome see: https://peperperspective.com/2017/06/23/healing-irritable-bowel-syndrome-with-diaphragmatic-breathing/

Take control of menstrual cramps

Numerous college students have reported that when they experience menstrual cramps, their natural impulse is to curl up in a protective cocoon. If instead they interrupted this natural protective pattern and lie relaxed on their back with their legs straight out and breathe diaphragmatically with their abdomen expanding and going upward during inhalation, they report a 50 percent decrease in discomfort (Gibney & Peper, 2003). For some the discomfort totally disappears when they place a warm pad on their lower abdomen and focused on breathing slowly about six breaths per minute so that the abdomen goes up when inhaling and goes down when exhaling. At the same time, they also imagine that the air would flow like a stream from their abdomen through their legs and out their feet while exhaling. They observed that as long as they held their abdomen tight the discomfort including the congestive PMS symptoms remained. Yet, the moment they practice abdominal breathing, the congestion and discomfort is decreased. Most likely the expanding and constricting of the abdomen during the diaphragmatic breathing acts as a pump in the abdomen to increase the lymph and venous blood return and improve circulation.

Conclusion

Breathing is the body-mind bridge and offers hope for numerous disorders. Slower diaphragmatic breathing with the corresponding abdomen movement at about six breaths per minute may reduce autonomic dysregulation. It has profound self-healing effects and may increase calmness and relaxation. At the same time, it may reduce heart palpitations, hypertension, asthma, anxiety, and many other symptoms.

References

DeVault, K.R. & Castell, D.O. (2005). Updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. The American Journal of Gastroenterology, 100, 190-200.

Domar, A.D., Seibel, M.M., & Benson, H. (1990). The Mind/Body Program for Infertility: a new behavioral treatment approach for women with infertility. Fertility and sterility, 53(2), 246-249.

Gibney, H.K. & Peper, E. (2003). Taking control: Strategies to reduce hot flashes and premenstrual mood swings. Biofeedback, 31(3), 20-24.

Johnson, L.F. & DeMeester, T.R. (1981). Evaluation of elevation of the head of the bed, bethanechol, and antacid foam tablets on gastroesophageal reflux. Digestive Diseases Sciences, 26, 673-680. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7261830

Melissa. (2015). Why women fainted so much in the 19th century. May 20, 2015. Donloaded October 2, 1018. http://www.todayifoundout.com/index.php/2015/05/women-fainted-much-19th-century/

Peper, E., Booiman, A., Lin, I-M, Harvey, R., & Mitose, J. (2016). Abdominal SEMG Feedback for Diaphragmatic Breathing: A Methodological Note. Biofeedback. 44(1), 42-49.

Peper, E., Mason, L., Huey, C. (2017). Healing irritable bowel syndrome with diaphragmatic breathing. Biofeedback. (45-4)

Stanciu, C. & Bennett, J.R.. (1977). Effects of posture on gastro-oesophageal reflux. Digestion, 15, 104-109. https://www.karger.com/Article/Abstract/197991