Reduce hot flashes and premenstrual symptoms with breathing

Posted: February 18, 2015 Filed under: Breathing/respiration, Pain/discomfort, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: biofeedback, Breathing, diaphragmatic breathing, heart rate variability, hormone replacement therapy, hot flashes, HRT, Menopause, respiration, sighs, stress, sympathetic activity 6 CommentsAfter the first week to my astonishment, I have fewer hot flashes and they bother me less. Each time I feel the warmth coming, I breathe out slowly and gently. To my surprise they are less intense and are much less frequent. I keep breathing slowly throughout the day. This is quite a surprise because I was referred for biofeedback training because of headaches that occurred after getting a large electrical shock. After 5 sessions my headaches have decreased and I can control them, and my hot flashes have decreased from 3-4 per day to 1-2 per week. -50 year old client

After students in my Holistic Health class at San Francisco State University practiced slower diaphragmatic breathing and begun to change their dysfunctional shallow breathing, gasping, sighing, and breath holding to diaphragmatic breathing. A number of the older female students students reported that their hot flashes decreased. Some of the younger female students reported that their menstrual cramps and discomfort were reduced by 80 to 90% when they laid down and breathed slower and lower into their abdomen.

The recent study in JAMA reported that many women continue to experience menopausal triggered hot flashes for up to 14 years. Although the article described the frequency and possible factors that were associated with the prolonged hot flashes, it did not offer helpful solutions.

The recent study in JAMA reported that many women continue to experience menopausal triggered hot flashes for up to 14 years. Although the article described the frequency and possible factors that were associated with the prolonged hot flashes, it did not offer helpful solutions.

Another understanding of the dynamics of hot flashes is that the decrease in estrogen accentuates the sympathetic/ parasympathetic imbalances that probably already existed. Then any increase in sympathetic activation can trigger a hot flash. In many cases the triggers are events and thoughts that trigger a stress response, emotional responses such as anger, anxiety, or worry, increase caffeine intake and especially shallow chest breathing punctuated with sighs. Approximately 80% of American women tend to breathe thoracically often punctuated with sighs and these women are more likely to experience hot flashes. On the other hand, the 20% of women who habitually breathe diaphragmatically tend to have fewer and less intense hot flashes and often go through menopause without any discomfort. In the superb study Drs. Freedman and Woodward (1992), taught women who experience hot flashes to breathe slowly and diaphragmatically which increased their heart rate variability as an indicator of sympathetic/parasympathetic balance and most importantly it reduced the the frequency and intensity of hot flashes by 50%.

Test the breathing connection if you experience hot flashes

Take a breath into your chest and rapidly exhale with a sigh. Repeat this quickly five times. In most cases, one minute later you will experience the beginning sensations of a hot flash. Similarly, when you practice slow diaphragmatic breathing throughout the day and interrupt every gasp, breath holding moment, sigh or shallow chest breathing with slower diaphragmatic breathing, you will experience a significant reduction in hot flashes.

Although this breathing approach has been well documented, many people are unaware of this simple behavioral approach unlike the common recommendation for the hormone replacement therapies (HRT) to ameliorate menopausal symptoms. This is not surprising since pharmaceutical companies spent nearly five billion dollars per year in direct to consumer advertising for drugs and very little money is spent on advertising behavioral treatments. There is no profit for pharmaceutical companies teaching effortless diaphragmatic breathing unlike prescribing HRTs. In addition, teaching and practicing diaphragmatic breathing takes skill training and practice time–time which is not reimbursable by third party payers.

For more information, research data and breathing skills to reduce hot flash intensity, see our article which is reprinted below.

Gibney, H.K. & Peper, E. (2003). Taking control: Strategies to reduce hot flashes and premenstrual mood swings. Biofeedback, 31(3), 20-24.

Taking control: Strategies to reduce hot flashes and premenstrual mood swings*

Erik Peper, Ph.D**., and Katherine H. Gibney

San Francisco State University

After the first week to my astonishment, I have fewer hot flashes and they bother me less. Each time I feel the warmth coming, I breathe out slowly and gently. To my surprise they are less intense and are much less frequent. I keep breathing slowly throughout the day. This is quite a surprise because I was referred for biofeedback training because of headaches that occurred after getting a large electrical shock. After 5 sessions my headaches have decreased and I can control them, and my hot flashes have decreased from 3-4 per day to 1-2 per week. -50 year old client

For the first time in years, I experienced control over my premenstrual mood swings. Each time I could feel myself reacting, I relaxed, did my autogenic training and breathing. I exhaled. It brought me back to center and calmness. -26 year old student

Abstract

Women have been troubled by hot flashes and premenstrual syndrome for ages. Hormone replacement therapy, historically the most common treatment for hot flashes, and other pharmacological approaches for pre-menstrual syndrome (PMS) appear now to be harmful and may not produce significant benefits. This paper reports on a model treatment approach based upon the early research of Freedman & Woodward to reduce hot flashes and PMS using biofeedback training of diaphragmatic breathing, relaxation, and respiratory sinus arrhythmia. Successful symptom reduction is contingent upon lowering sympathetic arousal utilizing slow breathing in response to stressors and somatic changes. We strongly recommend that effortless diaphragmatic breathing be taught as the first step to reduce hot flashes and PMS symptoms.

A long and uncomfortable history

Women have been troubled by hot flashes and premenstrual syndrome for ages. Hot flashes often result in red faces, sweating bodies, and noticeable and embarrassing discomfort. They come in the middle of meetings, in the middle of the night, and in the middle of romantic interludes. Premenstrual syndrome also arrives without notice, bringing such symptoms as severe mood swings, anger, crying, and depression.

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) was the most common treatment for hot flashes for decades. However, recent randomized controlled trials show that the benefits of HRT are less than previously thought and the risks—especially of invasive breast cancer, coronary artery disease, dementia, stroke and venous thromboembolism—are greater (Humphries & Gill, 2003; Shumaker, et al, 2003; Wassertheil-Smoller, et al, 2003). In addition, there is no evidence of increased quality of life improvements (general health, vitality, mental health, depressive symptoms, or sexual satisfaction) as claimed for HRT (Hays et al, 2003).

“As a result of recent studies, we know that hormone therapy should not be used to prevent heart disease. These studies also report an increased risk of heart attack, stroke, breast cancer, blood clots, and dementia…” -Wyeth Pharmaceuticals (2003)

Because of the increased long-term risk and lack of benefit, many physicians are weaning women off HRT at a time when the largest population of maturing women in history (‘baby boomers’) is entering menopausal years. The desire to find a reliable remedy for hot flashes is on the front burner of many researchers’ minds, not to mention the minds of women suffering from these ‘uncontrollable’ power surges. Yet, many women are becoming increasingly leery of the view that menopause is an illness. There is a rising demand to find a natural remedy for this natural stage in women’s health and development.

For younger women a similar dilemma occurs when they seek treatment of discomfort associated with their menstrual cycle. Is premenstrual syndrome (PMS) just a natural variation in energy and mood levels? Or, are women expected to adapt to a masculine based environment that requires them to override the natural tendency to perform in rhythm with their own psychophysiological states? Instead of perceiving menstruation as a natural occurrence in which one has different moods and/or energy levels, women in our society are required to perform at the status quo, which may contribute to PMS. The feelings and mood changes are quickly labeled as pathology that can only be treated with medication.

Traditionally, premenstrual syndrome is treated with pharmaceuticals, such as birth control pills or Danazol. Although medications may alleviate some symptoms, many women experience unpleasant side effects, such as bloating or acne, and still experience a variety of PMS symptoms. Many cannot tolerate the medications. Thus, millions of women (and families) suffer monthly bouts of ‘uncontrollable’ PMS symptoms

For both hot flashes and PMS the biomedical model tends to frame the symptoms as a “structural biological problem.” Namely, the pathology occurs because the body is either lacking in, or has an excess of, some hormone. All that needs to be done is either augment or suppress hormones/symptoms with some form of drug. Recently, for example, medicine has turned to antidepressant medications to address menopausal hot flashes (Stearns, Beebe, Iyengar, & Dube, 2003).

The biomedical model, however, is only one perspective. The opposite perspective is that the dysfunction occurs because of how we use ourselves. Use in this sense means our thoughts, emotions and body patterns. As we use ourselves, we change our physiology and, thereby, may affect and slowly change the predisposing and maintaining factors that contribute to our dysfunction. By changing our use, we may reduce the constraints that limit the expression of the self-healing potential that is intrinsic in each person.

The intrinsic power of self-healing is easily observed when we cut our finger. Without the individual having to do anything, the small cut bleeds, clotting begin and tissue healing is activated. Obviously, we can interfere with the healing process, such as when we scrape the scab, rub dirt in the wound, reduce blood flow to the tissue or feel anxious or afraid. Conversely, cleaning the wound, increasing blood flow to the area, and feeling “safe” and relaxed can promote healing. Healing is a dynamic process in which both structure and use continuously affect each other. It is highly likely that menopausal hot flashes and PMS mood swings are equally an interaction of the biological structure (hormone levels) and the use factor (sympathetic/parasympathetic activation).

Uncontrollable or overly aroused?

Are the hot flashes and PMS mood swings really ‘uncontrollable?’ From a physiological perspective, hot flashes are increased by sympathetic arousal. When the sympathetic system is activated, whether by medication or by emotions, hot flashes increase and similarly, when sympathetic activity decreases hot flashes decrease. Equally, PMS, with its strong mood swings, is aggravated by sympathetic arousal. There are many self-management approaches that can be mastered to change and reduce sympathetic arousal, such as breathing, meditation, behavioral cognitive therapy, and relaxation.

Breathing patterns are closely associated with hot flashes. During sleep, a sigh generally occurs one minute before a hot flash as reported by Freedman and Woodward (1992). Women who habitually breathe thoracically (in the chest) report much more discomfort and hot flashes than women who habitually breathe diaphragmatically. Freedman, Woodward, Brown, Javaid, and Pandey (1995) and Freedman and Woodward (1992) found that hot flash rates during menopause decreased in women who practiced slower breathing for two weeks. In their studies, the control groups received alpha electroencephalographic feedback and did not benefit from a reduction of hot flashes. Those who received training in paced breathing reduced the frequency of their hot flashes by 50% when they practiced slower breathing. This data suggest that the slower breathing has a significant effect on the sympathetic and parasympathetic balance.

Women with PMS appear similarly able to reduce their discomfort. An early study utilizing Autogenic Training (AT) combined with an emphasis on warming the lower abdomen resulted in women noting improvement in dysfunctional bleeding (Luthe & Schultz, 1969, pp. 144-148). Using a similar approach, Mathew, Claghorn, Largen, and Dobbins (1979) and Dewit (1981) found that biofeedback temperature training was helpful in reducing PMS symptoms.. A later study by Goodale, Domar, and Benson (1990) found that women with severe PMS symptoms who practiced the relaxation response reported a 58% improvement in overall symptomatology as compared to a 27.2% improvement for the reading control group and a 17.0% improvement for the charting group.

Teaching control and achieving results

Teaching women to breathe effortlessly can lead to positive results and an enhanced sense of control. By effortless breathing, the authors refer to their approach to breath training, which involves a slow, comfortable respiration, larger volume of air exchange, and a reliance upon action of the muscles of the diaphragm rather than the chest (Peper, 1990). For more instructions see the recent blog, A breath of fresh air: Improve health with breathing.

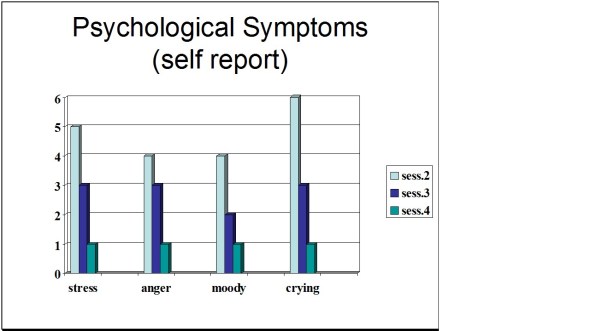

Slowing breathing helps to limit the sighs common to rapid thoracic breathing—sighs that often precede menopausal hot flashes. Effortless breathing is associated with stress reduction—stress and mood swings are common concerns of women suffering from PMS. In a pilot study Bier, Kazarian, Peper, and Gibney (2003) at San Francisco State University (SFSU) observed that when the subject practiced diaphragmatic breathing throughout the month, combined with Autogenic Training, her premenstrual psychological symptoms (anger, depressed mood, crying) and premenstrual responses to stressors were significantly reduced as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Student’s Individual Subjective Rating in Response to PMS Symptoms.

In another pilot study at SFSU, Frobish, Peper, and Gibney (2003) trained a volunteer who suffered from frequent hot flashes to breathe diaphragmatically. The training goals included modifying breathing patterns, producing a Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia (RSA), and peripheral hand warming. RSA refers to a pattern of slow, regular breathing during which variations in heart rate enter into a synchrony with the respiration. Each inspiration is accompanied by an increase in heart rate, and each expiration is accompanied by a decrease in heart rate (with some phase differences depending on the rate of breathing). The presence of the RSA pattern is an indication of optimal balance between sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous activity.

During the 11-day study period, the subject charted the occurrence of hot flashes and noted a significant decrease by day 5. However, on the evening of day 7 she sprained her ankle and experienced a dramatic increase in hot flashes on day 8. Once the subject recognized her stress response, she focused more on breathing and was able to reduce the flashes as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Subjective rating of intensity, frequency and bothersomeness of hot flashes. The increase in hot flashes coincided with increased frustration about an ankle injury.

Our clinical experience confirms the SFSU pilot studies and the previously referenced research by Freedman and Woodward (1992) and Freedman et al. (1995). When arousal is lowered and breathing is effortless, women are better able to cope with stress and report a reduction in symptoms. Habitual rapid thoracic breathing tends to increase arousal while slower breathing, especially slower exhalation, tends to relax and reduce arousal. Learning and then applying effortless breathing reduces excessive sympathetic arousal. It also interrupts the cycle of cognitive activation, anxiety, and somatic arousal. The anticipation and frustration at having hot flashes becomes the cue to shift attention and “breathe slower and lower.” This process stops the cognitively mediated self-activation.

Successful self-regulation and the return to health begin with cognitive reframing: We are not only a genetic biological fixed (deficient) structure but also a dynamic changing system in which all parts (thoughts, emotions, behavior, diet, stress, and physiology) affect and are effected by each other. Within this dynamic changing system, there is an opportunity to implement and practice behaviors and life patterns that promote health.

Learning Diaphragmatic Breathing with and without Biofeedback

Although there are many strategies to modify respiration, biofeedback monitoring combined with respiration training is very useful as it provides real-time feedback. Chest and abdominal movement are recorded with strain gauges and heart rate can be monitored either by an electrocardiogram (EKG) or by a photoplethysmograph sensor on a finger or thumb. Peripheral temperature and electrodermal activity (EDA) biofeedback are also helpful in training. The training focuses on teaching effortless diaphragmatic breathing and encouraging the participant to practice many times during the day, especially when becoming aware of the first sensations of discomfort.

Learning and integrating effortless diaphragmatic breathing into daily life is one of the biofeedback strategies that has been successfully used as a primary or adjunctive/complementary tool for the reversal of disorders such as hypertension, migraine headaches, repetitive strain injury, pain, asthma and anxiety (Schwartz & Andrasik, 2003), as well as hot flashes and PMS.

The biofeedback monitoring provides the trainer with a valuable tool to:

- Observe & identify: Dysfunctional rapid thoracic breathing patterns, especially in response to stressors, are clearly displayed in real-time feedback.

- Demonstrate & train: The physiological feedback display helps the person see that she is breathing rapidly and shallowly in her chest with episodic sighs. Coaching with feedback helps her to change her breathing pattern to one that promotes a more balanced homeostasis.

- Motivate, persuade and change beliefs: The person observes her breathing patterns change concurrently with a felt shift in physiology, such as a decrease in irritability, or an increase in peripheral temperature, or a reduction in the incidence of hot flushes. Thus, she has a confirmation of the importance of breathing diaphragmatically.

In addition, we suggest exercises that integrate verbal and kinesthetic instructions, such as the following: “Exhale gently,” and “Breathe down your leg with a partner.”

Exhale Gently:

Imagine that you are holding a baby. Now with your shoulders relaxed, inhale gently so that your abdomen widens. Then as you exhale, purse your lips and very gently and softly blow over the baby’s hair. Allow your abdomen to narrow when exhaling. Blow so softly that the baby’s hair barely moves. At the same time, imagine that you can allow your breath to flow down and through your legs. Continue imagining that you are gently blowing on the baby’s hair while feeling your breath flowing down your legs. Keep blowing very softly and continuously.

Practice exhaling like this the moment that you feel any sensation associated with hot flashes or PMS symptoms. Smile sweetly as you exhale.

Breathe Down Your Legs with a Partner

Sit or lie comfortably with your feet a shoulder width apart. As you exhale softly whisper the sound “Haaaaa….” Or, very gently press your tongue to your pallet and exhale while making a very soft hissing sound.

Have your partner touch the side of your thighs. As you exhale have your partner stroke down your thighs to your feet and beyond, stroking in rhythm with your exhalation. Do not rush. Apply gentle pressure with the stroking. Do this for four or five breaths.

Now, continue breathing as you imagine your breath flowing through your legs and out your feet.

During the day remember the feeling of your breath flowing downward through your legs and out your feet as you exhale.

Learning Strategies in Biofeedback Assisted Breath Training

Common learning strategies that are associated with the more successful amelioration of hot flashes and PMS include:

- Master effortless diaphragmatic breathing, and concurrently increase respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA). Instead of breathing rapidly, such as at 18 breaths per minute, the person learns to breathe effortlessly and slowly (about 6 to 8 breaths per minute). This slower breathing and increased RSA is an indication of sympathetic-parasympathetic balance as shown in Figure 3.

- Practice slow effortless diaphragmatic breathing many times during the day and, especially in response to stressors.

- Use the physical or emotional sensations of a hot flash or mood alteration as the cue to exhale, let go of anxiety, breathe diaphragmatically and relax.

- Reframe thoughts by accepting the physiological processes of menstruation or menopause, and refocus the mind on positive thoughts, and breathing rhythmically.

- Change one’s lifestyle and allow personal schedules to flow in better balance with individual, dynamic energy levels.

Figure 3. Physiological Recordings of a Participant with PMS. This subject learned effortless diaphragmatic breathing by the fifth session and experienced a significant decrease in symptoms.

Figure 3. Physiological Recordings of a Participant with PMS. This subject learned effortless diaphragmatic breathing by the fifth session and experienced a significant decrease in symptoms.

Generalizing skills and interrupting the pattern

The limits of self-regulation are unknown, often held back only by the practitioner’s and participant’s beliefs. Biofeedback is a powerful self-regulation tool for individuals to observe and modify their covert physiological reactions. Other skills that augment diaphragmatic breathing are Quieting Reflex (Stroebel, 1982), Autogenic Training (Schultz & Luthe, 1969), and mindfulness training (Kabat-Zinn, 1990). In all skill learning, generalization is a fundamental factor underlying successful training. Integrating the learned psychophysiological skills into daily life can significantly improve health—especially in anticipation of and response to stress. The anticipated stress can be a physical, cognitive or social trigger, or merely the felt onset of a symptom.

As the person learns and applies effortless breathing to daily activities, she becomes more aware of factors that affect her breathing. She also experiences an increased sense of control: She can now take action (a slow effortless breath) in moments when she previously felt powerless. The biofeedback-mastered skill interrupts the evoked frustrations and irritations associated with an embarrassing history of hot flashes or mood swings. Instead of continuing with the automatic self-talk, such as “Damn, I am getting hot, why doesn’t it just stop?” (language fueling sympathetic arousal), she can take a relaxing breath in response to the internal sensations, stop the escalating negative self-talk and allows more acceptance—a process reducing sympathetic arousal.

In summary, effortless breathing appears to be a non-invasive behavioral strategy to reduce hot flashes and PMS symptoms. Practicing effortless diaphragmatic breathing contributes to a sense of control, supports a healthier homeostasis, reduces symptoms, and avoids the negative drug side effects. We strongly recommend that effortless diaphragmatic breathing be taught as the first step to reduce hot flashes and PMS symptoms.

I feel so much cooler. I can’t believe that my hand temperature went up. I actually feel calmer and can’t even feel the threat of a hot flash. Maybe this breathing does work! –Menopausal patient after initial training in diaphragmatic breathing

References

Bier, M., Kazarian, D., Peper, E., & Gibney, K. (2003). Reducing the severity of PMS symptoms with diaphragmatic breathing, autogenic training and biofeedback. Unpublished report.

Freedman, R.R., & Woodward, S. (1992). Behavioral treatment of menopausal hot flushes: Evaluation by ambulatory monitoring. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 167 (2), 436-439.

Freedman, R.R., Woodward, S., Brown, B., Javaid, J.I., & Pandey, G.N. (1995). Biochemical and thermoregulatory effects of behavioral treatment for menopausal hot flashes. Menopause: The Journal of the North American Menopause Society, 2 (4), 211-218.

Frobish,C., Peper, E. & Gibney, K. H. (2003). Menopausal Hot Flashes: A Self-Regulation Case Study. Poster presentation at the 35th Annual Meeting of the Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. Abstract in: Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. 29 (4), 302.

Goodale, I.L., Domar, A.D., & Benson, H. (1990). Alleviation of Premenstrual Syndrome symptoms with the relaxation response. Obstetrics and Gynecological Journal, 75 (5), 649-55.

Hays, J., Ockene, J.K., Brunner, R.L., Kotchen, J.M., Manson, J.E., Patterson, R.E., Aragaki, A.K., Shumaker, S.A., Brzyski, R.G., LaCroix, A.Z., Granek, I.A, & Valanis, B.G., Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. (2003). Effects of estrogen plus progestin on health-related quality of life. New England Journal of Medicine, 348, 1839-1854.

Humphries, K.H.., & Gill, s. (2003). Risks and benefits of hormone replacement therapy: the evidence speaks. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 168(8), 1001-10.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living. New York: Delacorte Press.

Luthe, W. & Schultz, J.H. (1969). Autogenic therapy: Vol II: Medical applications. New York: Grune & Stratton.

Mathew, R.J.; Claghorn, J.L.; Largen, J.W.; & Dobbins, K. (1979). Skin Temperature control for premenstrual tension syndrome:A pilot study. American Journal of Clinical Biofeedback, 2 (1), 7-10.

Peper, E. (1990). Breathing for health. Montreal: Thought Technology Ltd.

Schultz, J.H., & Luthe, W. (1969). Autogenic therapy: Vol 1. Autogenic methods. New York: Grune and Stratton.

Schwartz, M.S. & Andrasik, F.(2003). Biofeedback: A practitioner’s guide, 3nd edition. New York: Guilford Press.

Shumaker, S.A., Legault, C., Thal, L., Wallace, R.B., Ockene, J., Hendrix, S., Jones III, B., Assaf, A.R., Jackson, R. D., Morley Kotchen, J., Wassertheil-Smoller, S.; & Wactawski-Wende, J. (2003). Estrogen plus progestin and the incidence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in post menopausal women: The Women’s Health Initiative memory study: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 289 (20), 2651-2662.

Stearns, V., Beebe, K. L., Iyengar, M., & Dube, E. (2003). Paroxetine controlled release in the treatment of menopausal hot flashes. Journal of the American Medical Association, 289 (21), 2827-2834.

Stroebel, C. F. (1982). QR, the quieting reflex. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons.

van Dixhoorn, J.J. (1998). Ontspanningsinstructie Principes en Oefeningen (Respiration instructions: Principles and exercises). Maarssen, Netherlands: Elsevier/Bunge.

Wassertheil-Smoller, S., Hendrix, S., Limacher, M., Heiss, G., Kooperberg, C., Baird, A., Kotchen, T., Curb, Dv., Black, H., Rossouw, J.E., Aragaki, A., Safford, M., Stein, E., Laowattana, S., & Mysiw, W.J. (2003). Effect of estrogen plus progestin on stroke in postmenopausal women: The Women’s Health Initiative: A randomized trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 289 (20), 2673-2684.

Wyeth Pharmaceuticals (2003, June 4). A message from Wyeth: Recent reports on hormone therapy and where we stand today. San Francisco Chronicle, A11.

*We thank Candy Frobish, Mary Bier and Dalainya Kazarian for their helpful contributions to this research.

**For communications contact: Erik Peper, Ph.D., Institute for Holistic Healing Studies, San Francisco State University, 1600 Holloway Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94132; Tel: (415) 338 7683; Email: epeper@sfsu.edu; website: http://www.biofeedbackhealth.org; blog: http://www.peperperspective.come

The surprising and powerful links between posture and mood

Posted: February 3, 2015 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: anxiety, depression, mind-body, posture, stress, stress management Leave a commentEnjoy Vivian Giang’s superb blog, The surprising and powerful links between posture and mood, published by Fast Company and reprinted with permission. It summarizes in a very readable way how posture affects health and well being.

The Surprising and Powerful Links between Posture and Mood

Why feeling taller tricks your brain into making you feel more confident and why your smartphone addiction might be making you depressed.

The next time you’re feeling sad and depressed, pay close attention to your posture. According to cognitive scientists, you’ll likely be slumped over with your neck and shoulders curved forward and head looking down.

While it’s true that you’re sitting this way because you’re sad, it’s also true that you’re sad because you’re sitting this way. This philosophy, known as embodied cognition, is the idea that the relationship between our mind and body runs both ways, meaning our mind influences the way our body reacts, but the form of our body also triggers our mind.

In large part due to Amy Cuddy’s widly popular 2012 TED talk, most of us know that two minutes of “power poses” a day can change how we feel about ourselves. This isn’t just about displaying confidence to others around; this is about actually changing your hormones—increased levels of testosterone and decreased levels of cortisol, or the stress hormone, in the brain.

“The brain has an area that reflects confidence, but once that area is triggered it doesn’t matter exactly how it’s triggered,” says Richard Petty, professor of psychology at Ohio State University. “It can be difficult to distinguish real confidence from confidence that comes from just standing up straight … these things go both ways just like happiness leads to smiling, but also smiling leads to happiness.”

When it comes to posture, Petty explains that the way we ultimately feel has a lot to do with the associations we have with being taller. For example, if you take two people and you put one on a chair that’s above the other person, the one that’s looking down will feel more powerful because “we have all these associations” with height and power that “gets triggered automatically when certain movements are made,” he says. The function of your body posture tells your brain that you’re powerful, which, in turn, affects your attitude.

In a 2009 study published in the European Journal of Social Psychology, Petty along with other researchers instructed 71 college students to either “sit up straight” and “push out [their] chest” or “sit slouched forward” with their “face looking at [their] knees.” While holding their assigned posture, the students were asked to list either three positive or negative personal traits they thought would contribute to their future job satisfaction and professional performance. Afterward, the students were asked to take a survey where they rated themselves on how well they thought they would perform as a future professional.

The researchers found that how the students rated themselves depended on the posture they kept when they wrote the positive or negative traits. Those who were in the upright position believed in the positive and negative traits they wrote down while those in the slouched over position weren’t convinced of their positive or negative traits. In other words, when the students were in the upright, confident position, they trusted their own thoughts whether those thoughts were positive or negative. On the other hand, when the students sat in a powerless position, they didn’t trust anything they wrote down whether it was positive or negative.

However, those in the upright position likely had an easier time thinking of “empowering, positive” traits about themselves to write down while those in the slouched over position probably had an easier time recalling “hopeless, helpless, powerless, and negative” feelings, according to Erik Peper, professor of Holistic Health at San Francisco State University.

In a series of experiments, Peper found that sitting in a collapsed, helpless position makes it easier for negative thoughts and memories to appear while sitting in an upright, powerful position makes it easier to have empowering thoughts and memories.

“Emotions and thoughts affect our posture and energy levels; conversely, posture and energy affect our emotions and thoughts,” says one of Peper’s studies from 2012, and two minutes of skipping versus walking in a slouched position can make a significant difference on our energy levels. Like Cuddy, Peper’s research finds that it only takes two minutes to change your hormones, meaning you can basically change the chemistry in your brain while waiting for your food to heat up in the microwave.

Since posture affects our mood and thoughts so much, the increase of collapsed sitting and walking—from sitting in front of our computer to looking down at our smartphones—may very much have an effect on the rise of depression in recent years. Peper and his team of researchers suggest that posture is a significant contributor to decreased energy levels and depression. Slouching is also known to result in frequent headaches and neck and shoulder pains.

With so much research proving the influence posture has on our mind, Peper suggests hanging photos of people you love slightly higher on the wall or above your desk so that you have to look up. Also, adjust your rear view mirror slightly higher so that you have to sit up taller while driving. If you need reminders, Petty advises setting reminders on your phone, computer, or even a Post-It note. When you do have negative thoughts, instead of validating them by slumping over or bending your head, Petty says that you should write them down on a piece of paper, then throw that piece of paper away in the trash.

“People who throw those negative thoughts into the trash can are less affected by them then people who had the same thoughts but symbolically put them in their pocket,” he says. “It’s this idea that it’s not what we think that’s important; it’s how much we trust what we think.”

Reprinted by permission from Vivian Giang

Increase strength and mood

Posted: June 22, 2014 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: depression, exercise, mind-body, posture, stress 13 Comments“Don’t slouch! How many times do I have to tell you to sit up straight?”

“I couldn’t believe it, I could not think of any positive thoughts while looking down?

Body posture is part of our nonverbal communication; it sometimes projects how we feel. We may collapse when we receive bad news or jump up with joy when we achieve our goal. More and more we sit collapsed for many hours with our spine in flexion. We crane our heads forward to read text messages, a tablet, a computer screen or watch TV. Our bodies collapse when we think hopeless, helpless, powerless thoughts, or when we are exhausted. We tend to slouch and feel “down” when depressed.

We often shrink and collapse to protect ourselves from danger when we are threatened. In prehistoric times this reaction would protect us from predators as we were still prey. Now we may still give the same reaction we worry or respond to demands from our boss. At those moments, we may blank out and have difficulty to think and plan for future events. When the body reacts defensively, the whole body-mind is concerned with immediate survival. Rational and abstract thinking is reduced as we attempt to escape.

When standing tall we occupy more space and tend to project power and authority to others and to ourselves. When we feel happy, we walk erect with a bounce in our step. Emotions and thoughts affect our posture and energy levels; conversely, posture and energy affect our emotions and thoughts. At San Francisco State University, we have researched how posture changes physical strength and access to past memories. Experience this in the following practice (you will need a partner to do this).

How posture affects strength

Stand behind your partner and ask them to lift their right arm straight out as shown in figure 1. Apply gentle pressure downward at the right wrist while your partner attempts to resist the downward pressure. Apply enough pressure downward so that the right arm begins to go down. Relax and repeat the same exercise with the left arm. Then relax.

Figure 1. Experimenter pressing down on the arm while the subject resist the downward pressure

For the rest of this exercise, do the testing with the arm that most resisted to the downward pressure.

Have the person stand in a slouched position and then lift the same arm straight out. Again the experimenter applies enough pressure downward so that the arm begins to go down. Relax.

Then have the person stand a tall position and lift the arm straight out. Again, the experimenter now applies enough pressure downward so that the arm begins to go down. Relax.

Describe to each other how easy it was to resist the downward pressure and how much effort it took to press the arm down while standing tall or slouched.

In our just completed study in the Netherlands with my colleague Annette Booiman, we observed that 98% of the participants felt significantly stronger to resist the downward pressure when they stood in a tall position than when they stood in the collapsed position as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The perceived strength to resist the down pressure on the arm in either the erect or collapsed position as observed by the subjects and the experimenters (Exp).

The subjective experience of strength may be a metaphor of how posture affects our thoughts, emotions, hormones and immune system[1]. When slouching we experience less strength to resist and it is much more challenging to project authority, think creatively and successfully solve problem. Obviously, the loss of strength mainly related to the change in the shoulder mechanics; however, the collapsed body position contributes to feeling hopeless, helpless, and powerless.

With my colleague Dr. Vietta Wilson (Wilson & Peper, 2004), we discovered that in the collapsed position it was very difficult to evoke positive and empowering memories as compared to the upright position (for more information see the article by Wilson and Peper: http://biofeedbackhealth.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/the-effects-of-posture-on-mood.pdf).

Consistently, my students at San Francisco State University have reported that when they blank out on exams or class presentations, if they stop for a moment, change their posture and breathe, they can think again. Similarly, clients who are captured by worry and discomfort, when they shift position and look up, find it is easier to think of new options. Explore for this yourself.

How Posture effect Memory Recall

Sit comfortably at the edge of a chair and then collapse downward so that your back is rounded like the letter C. Let your head tilt forward and look at the floor between your thighs as shown in figure 3.

Figure 3. Sitting in a collapsed position (photo by Jana Asenbrennerova). Reprinted by permission from Gorter and Peper (2011).

Figure 3. Sitting in a collapsed position (photo by Jana Asenbrennerova). Reprinted by permission from Gorter and Peper (2011).

While in this position, bring to mind hopeless, helpless, powerless, and depressive memories one after the other for thirty seconds.

Then, let go of those thoughts and images and, without changing your position and still looking downward, recall empowering, positive, and happy memories one after the other for thirty seconds.

Shift position and sit up erect, with your back almost slightly arched and your head held tall while looking slightly upward as shown in figure 4.

Figure 4. Sitting in an upright position (photo by Jana Asenbrennerova). Reprinted by permission from Gorter and Peper (2011).

Figure 4. Sitting in an upright position (photo by Jana Asenbrennerova). Reprinted by permission from Gorter and Peper (2011).

While is this position, bring to mind many hopeless, helpless, powerless, or depressive memories one after the other for thirty seconds.

Then, let go of those thoughts and images and, without changing position and while still looking upward, recall as many empowering, positive, and happy memories one after the other for thirty seconds

Ask yourself: In which position was it easier to evoke negative memories and in which position was it easier to evoke empowering, positive, and happy memories?

Overwhelmingly participants report that in the downward position it was much easier to recall negative and hopeless memories. And, in the upright position it was easier to recall positive and empowering memories. In many cases, participant reported that when they looked down, they could not evoke any positive and empowering memories. It is not surprising that when people feel optimistic about the future, they say, “Things are looking up.”

Mind and body affect each other. The increase in depression and fatigue may be in part be caused by the body position of sitting collapsed at work, at home and walking a slouched pattern. By shifting body movement and position from slouching to skipping one’s subjective energy may significantly increase (Peper & Lin, 2012) (for more information see: https://peperperspective.com/2012/09/30/take-charge-of-your-energy-level-and-depression-with-movement-and-posture/)

Take charge, lightening your mood and give yourself the opportunity to be empowered and hopeful. When feeling down, acknowledge the feeling and say, “At this moment, I feel overwhelmed, and I’m not sure what to do” or whatever phrase fits the felt emotions. When your energy is low, again acknowledge this to yourself: “At this moment I feel exhausted,” or “At this moment, I feel tired,” or whatever phrase fits the feeling. As you acknowledge it, be sure to state “at this moment.” The phrase “at this moment” is correct and accurate. It implies what is occurring without a self-suggestion that the feeling will continue, which helps to avoid the idea that this was, is, and will always be. The reality is that whatever we are experiencing is always limited to this moment, as no one knows what will occur in the future. This leaves the future open to improvement.

Remind yourself that you to shift your mood by changing your posture. When you’re outside, focus on the clouds moving across the sky, the flight of birds, or leaves on the trees. In your home, you can focus on inspiring art on the wall or photos of family members you love and who love you. When you hang pictures, hang them higher than you normally would so that you must look up. You can also put pictures above your desk to remind yourself to look up and to evoke positive memories.

These two studies point out that psychology needs to incorporate body posture and movement as part of the therapeutic and teaching process. Without teaching how to change body posture only one half of the mind-body equation that underlies health and illness is impacted.

Each time you collapse or have negative thoughts, change your position and sit up and look up. Arrange your world so that you are erect (e.g., stand while working at the computer, use a separate keyboard with your laptop so that the top of the screen is at eye level, or place a pillow in your lower back when sitting). Finally, every so often, get up and move while alternately reach up with your arms into the sky as if picking fruits which you can not quite reach.

After having done these two practices, I realized how powerful my body effects my mood and energy level. Now each time I am aware that I collapse, I take a breath, shift my position, look up, and often stand up and stretch. To my surprise, I have so much more energy and my negative depressive mood has lifted.

References:

Gorter, R. & Peper, E. (2011). Fighting cancer-A nontoxic approach to treatment. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books.

Peper, E. & Lin, I-M. (2012). Increase or decrease depression-How body postures influence your energy level. Biofeedback, 40 (3), 126-130.

Wilson, V.E. and Peper, E. (2004). The Effects of upright and slumped postures on the generation of positive and negative thoughts. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.29 (3), 189-195.

[1] In an elegant study by Professor Amy Cuddy from the Harvard Business School, she demonstrated that two minutes of standing in a power position significant increased testosterone and decreased cortisol while standing in the collapsed position significantly decreased testosterone and increased cortisol. By changing posture, you not only present yourself differently to the world around you, you actually change your hormones (For more information, see Professor Amy Cuddy’s Ted talk: http://www.ted.com/talks/amy_cuddy_your_body_language_shapes_who_you_are).

Optimizing ergonomics: Adapt the world to you and not the other way around

Posted: February 24, 2014 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: ergonomics, muscle tension, posture, stress, Workstyle 2 CommentsHaving the right equipment doesn’t mean we use it correctly. It turns out that usage patterns matter just as much as fancy new office furniture. This post was inspired by a wonderful article that David Kadavy generously interviewed me for. His article explores split keyboards and working wellness. In this post, I go in-depth on some complimentary workplace tools and techniques.

After working on a laptop, smartphone or computer, many people experience discomfort and exhaustion. Back and neck pain and vision problems are very common. Although there are many components that contribute to maintaining health and productivity with digital devices, two factors stand out:

- Ergonomic arrangement: the way the physical environment forces the person to adapt, such as bending over to read and perform data entry with a tablet.

- Work style: the way the person manages themselves to perform the tasks.

Many problems that are aggravated or caused by inappropriate ergonomics can be compensated by changing workstyle. For example, if you bend forward to read the tablet or squint to see the text on the monitor, you can take many movement and stress reduction breaks to compensate for the challenging ergonomics. Having the right equipment, appropriately adjusted, is the focus of ergonomics. Working so that health is maintained regardless of equipment is the focus of work style.

Shoes are a great example. Healthy shoes would look like duck feet–wider at the ball of the feet and toes and narrower at the heel. However, most shoes have pointy or narrow toe boxes. Over time, incorrect footwear becomes a major cause of bunions, foot, hip and back pain for older adults. It causes physical deformity just as the 19th century Chinese practice of foot-binding crippled many women. If you want to run a 100 meter race or a marathon—running shoes are better than high heels. Adapting the environment to you instead of the other way around is the underlying theme of ergonomics.

But even with correctly fitting shoes many people still experience discomfort. Often this is because of misaligned movement patterns. such as their feet point outward while walking instead of pointing ahead. Or they unknowingly favor one leg over the other because many years earlier they broke that leg and adapted their walking pattern to reduce the pain. After walking to avoid pain for a month, this new dysfunctional pattern became habitual and their gait never returned to normal. Changing how you walk or work is the focus of optimum work style. For useful suggestions about workstyle see Healthy Computer Email Tips by Erik Peper.

Many experts have worked for decades on defining optimal ergonomics for using digital devices. The results are always compromises because human beings did not evolve to sit in a chair for hours without movement or read from a small screen in front of them. Nevertheless, the ergonomic setup while using laptops and tablets can be significantly improved. It is impossible to achieve a healthy ergonomic setup while using a laptop or tablet. If the screen is placed so that is easily readable, then the fingers and hands need to be lifted (which often involves lifting the shoulders) to perform data entry. On the other hand if the keyboard is at the appropriate height then you have to look down on the screen. If you regularly use a laptop or tablet, consider purchasing a separate monitor and/or keyboard to improve your setup.

And if you’re replacing your keyboard, make sure to check out David Kadavy’s excellent blog: This weird keyboard may be the biggest thing since your standing desk.

Simple Ways to Manage Stress- An experiential lecture for people impacted by the March 11, 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake

Posted: November 8, 2013 Filed under: self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: anxiety, depression, earthquake, exercise, insomnia, neck pain, stress, stress management, tsunami 6 CommentsStress can be reduced by simple pragmatic exercises. This 99 minute participatory lecture was presented in Sendei, Japan, on July 20, 2013 to people who were impacted by the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami disaster.* The lecture includes practices that demonstrate 1) how thoughts, emotions and images affect the body, 2) how simple movements can reduce muscle tension, 3) how breathing can be used to reduce stress, 4) how changing posture can change access to positive or negative memories, 5) how acceptance is the beginning step for healing. This approach based upon a holistic evolutionary perspective of stress and health can be used to reduce symptoms caused or increased by stress such as neck, shoulder and back tension, digestive problems, worrying and insomnia. The video lecture is sequentially translated from English to Japanese. Click on the link to watch the video lecture.

http://cat-vnet.tv/movie/medical_health/suimin_02/001_02.html

*The program was organized by Toshihiko Sato, Ph.D., Dept. Health and Social Services, Faculty of Medical Sciences and Welfare Tohoku Bunka Gakuen University, Sendai.

Live longer, enhance fertility and increase stress resistance: Eat organic foods

Posted: April 21, 2013 Filed under: Nutrition/diet, Uncategorized | Tags: diet, fertility, organic foods, pesticide, stress 12 CommentsHealth food advocates have long claimed that organic foods are better for your health because they have more nutrients and fewer pesticides than non organic or genetically modified grown foods. On the other hand, the USDA and agribusiness tend to claim that organically grown foods have no additional benefits. Until now, much of the published research appeared inconclusive and meta-analysis appeared to indicate that there are no health benefits from organic as compared to non organic foods although organic foods did reduce eczema in infants (Dangour et al, 2010).

Food studies that have demonstrated no benefits of organic farmed foods as compared to non-organic or genetically modified crops should be viewed with skepticism since many of these studies have been funded directly or indirectly by agribusiness. On the other hand, independently funded research studies have tended to demonstrate that organic foods are more beneficial than non-organic foods. Sadly, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and agribusiness are highly interdependent as the USDA both regulates and promotes agricultural products. On the one hand the USDA’s mission is “To expand economic opportunity through innovation, helping rural America to thrive; to promote agriculture production” and on the other hand “Enhance food safety by taking steps to reduce the prevalence of food borne hazards from farm to table, improving nutrition and health by providing food assistance and nutrition education and promotion. (For more discussion on the conflict of interest between agribusiness and the USDA, see Michael Pollan’s superb books, The Omnivore’s Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals and In Defense of Food: An Eater’s Manifest).

Historically, most nutritional studies have investigated the nutritional difference or pesticide residue between organic and non-organically farmed. Many studies have shown that organic grown foods have significantly lower pesticide residues than non organic foods (Baker et al, 2002; Luc, 2006). Even though agribusiness and the USDA tend to state that the pesticide residues left in or on the food are safe and non-toxic and have no health consequences, I have my doubts. Human beings accumulate pesticides just like tuna fish accumulates mercury—frequent ingesting of very low levels of pesticides residue may result in long term harmful effects. One way to measure if there is an effect of organic, non organic or genetically modified grown foods or residual pesticides is to do a long term follow up and measure the impact over the lifespan of the organism. This is difficult with human beings; since, it would take 50 or more years to observe the long term effects. Nevertheless, the effects of organically grown foods versus non-organically grown foods upon lifespan, fertility and stress resistance has now been demonstrated with fruit flies.

The elegant research by Chhabra R, Kolli S, Bauer JH (2013) showed that when fruit flies were fed either organic bananas, potatoes, soy or raisins, they demonstrated a significant increase in longevity, fertility and stress resistance as compared to eating non-organic bananas, potatoes, soy and raisins. In this controlled study, the outcome data is stunning. Below are some of their results reproduced from their article, “Organically Grown Food Provides Health Benefits to Drosophila melanogaster.”

Figure 1. Longevity of D. melanogaster fed organic diets. Survivorship curves of female fruit flies fed diets made from extracts of potatoes, raisins, bananas or soybeans (grey: conventional food; black: organic food; statistically significant changes (p,0.005) are indicated by asterisks).Median survival times of flies on conventional and organics food sources, respectively, are: potatoes: 16 and 22 days (,38% longevity increase,p,0.0001); soybeans: 8 and 14 days (,75% longevity increase, p,0.0001).doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0052988.g001. Reproduced from Chhabra R, Kolli S, Bauer JH (2013).

Figure 2. Daily egg-laying of flies exposed to organic diets. Egg production of flies fed the indicated food was determined daily. Shown are the averages of biological replicates; error bars represent the standard deviation (grey: conventional food; black: organic food; statistically significant changes (p,0.005) are indicated by asterisks; p,0.0001 for all food types). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0052988.g002. Reproduced from Chhabra R, Kolli S, Bauer JH (2013).

Figure 3. Starvation tolerance of flies raised on organic diets. Survivorship curves of female flies raised for 10 days on the indicated food sources. Flies were then transferred to starvation media and dead flies were counted twice daily (grey: conventional food; black: organic food; statistically significant changes (p,0.005) are indicated by asterisks). Median survival times of flies on conventional and organics food sources, respectively, are: potatoes: 6 and 24 hours (p,0.0001); bananas: 24 and 48 hours (p,0.0001). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0052988.g003. Reproduced from Chhabra R, Kolli S, Bauer JH (2013)

This elegant study demonstrated the cumulative impact of organic versus non-organic food source upon survival fitness. It demonstrated that non-organic foods decreased the overall health of the organism which may be due to the lower levels of essential nutrients, presence of pesticides or genetic modified factors.

The take home message of their research is: If you are concerned about your health, want to live healthier and longer, improve fertility and resist stress, eat organically grown fruits and vegetable. Although this research was done with fruit flies and human beings are not fruit flies since we eat omnivorously, it may still be very relevant especially for children. As children grow the ingestion of non-organic foods may cause a very low level nutrient malnutrition coupled with an increased exposure to pesticides. The same concept can be extended to meats and fish. Eat only meat from free ranging animals that have been fed organic grown foods and not been given antibiotics or hormones to promote growth.

Bon appétit

.References

Baker, B.P., Benbrook, C.M., & Groth III, E., & Lutz, K. (2002). Pesticide residues in conventional, integrated pest management (IPM)-grown and organic foods: insights from three US data sets. Food Additives and Contaminants, 19(5) http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02652030110113799

Chhabra R, Kolli S, Bauer JH (2013) Organically Grown Food Provides Health Benefits to Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS ONE 8(1): e52988. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0052988 http://www.plosone.org/article/info:doi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0052988

Dangour, A.D., Lock, K., Hayter, A., Aikenhead, A., Allen, E., Uauy, R. (2010). Nutrition related health effects of organic foods: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr, 92,203–210. http://ajcn.nutrition.org/content/92/1/203.short

Luc, C., Toepel, K., Irish, R., Fenske, R.A., Barr, D.B., & Bravo, R. (2006). Organic Diets Significantly Lower Children’s Dietary Exposure to Organophosphorus Pesticides. Environ Health Perspect, 114(2), 260–263. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1367841/

Pollan, M. (2009). In Defense of Food: An Eater’s Manifesto. New York: Penguin Press. ISBN: 978-0143114963

Pollan, M. (2006). The Omnivore’s Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals. New York: Penguin Press. ISBN: 1594200823

Biofeedback and pain control. Two YouTube interviews of Erik Peper, PhD by Larry Berkelhammer, PhD

Posted: October 12, 2012 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: asthma, biofeedback, hope, pain, self-regulation, stress, stress management 1 CommentErik Peper, Biofeedback Builds Self-efficacy, Hope, Health, & Well-being

Interview with biofeedback pioneer Dr. Erik Peper on how biofeedback builds self-efficacy, hope, health and well-being. How to use the mind to improve physiological functioning and health. Skill-building to develop self-efficacy, self-empowerment, and hope. Evidence-based mental training to manage symptoms, self-regulate blood pressure, chronic pain & fatigue, cardiac dysrhythmias, digestion, and many other bodily processes.

Erik Peper, Pain Control Through Relaxation

This interview of Dr. Erik Peper explores the frontier of psychophysiological self-regulation. Included is conscious regulation of pain, blood pressure, and other physiological measures. We discuss how you can take control and consciously calm your sympathetic nervous system in order to attenuate pain. Autogenic Training, yogic disciplines, biofeedback, and other methods are mentioned as ways to use the mind to gain conscious control of cognitive, emotional, and physiological processes. For example, when we experience sudden pain, we automatically brace against it in the hope of resisting it. Paradoxically, this increases suffering. Autogenic Training and many other disciplines provide us with the skills to relax into any painful stimulus. Although it seems counterintuitive, learning to fully accept and relax into the pain allows us to take control over the pain, whereas trying to control it serves to increase the suffering. Another concept that is discussed in this video is that we can reduce pain and speed healing by extending loving self-care to any injury.

Adopt a power posture and change brain chemistry and probability of success

Posted: October 7, 2012 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: cortisol, posture, stress 3 CommentsLess than two minutes of body movement can increase or decrease energy level depending on which movement the person performs (Peper and Lin). Static posture has an even larger social impact—it affects how others see us and how we perform. Social psychologist Amy Cuddy, professor and researcher from Harvard Business School, has demonstrated that by adopting a posture of confidence for two minutes—even when you just fake it—significantly improves yourchances for success and your brain chemistry. The power position significantly increases testosterone and decreases cortisol levels in our brain. If you want to improve performance and success, watch Professor Amy Cuddy’s inspiring Ted talk (http://www.ted.com/talks/amy_cuddy_your_body_language_shapes_who_you_are.html)

Is there a link between stress and cancer?

Posted: January 19, 2012 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: breast cancer, cancer, stress, stress management Leave a commentMany factors contribute to the onset and progression of cancer such as exposure to carcinogenic agents, behavioral risk factors, compromised immune functioning or stress. The stress most strongly associated with increased breast cancer occurrence is the stress caused by major life events such death of a husband, divorce/separation, personal illness or injury, death of a close relative or friend, and loss of a job. Stress also increases the risk of re-occurrence and poorer outcome.

If stress can increase cancer risk then learning stress management techniques may reduce the risk and improve clinical outcome. In a superb eleven year long follow-up study, Professor Barbara Anderson of Ohio University showed that patients with breast cancer who had participated in a 14 week stress management program had significantly higher survival rates and lower re-occurrence rates as compared to the control group.

The findings that stress increases cancer risk and stress management improves survival suggests that stress management should be part of cancer treatment and prevention. For useful stress management techniques that patients can immediately do for themselves, see Part III-Self-care in the book, Fighting Cancer.