Cellphones affects social communication, vision, breathing, and health: What to do!

Posted: September 4, 2024 Filed under: ADHD, attention, behavior, Breathing/respiration, cellphone, computer, digital devices, educationj, ergonomics, health, laptops, Neck and shoulder discomfort, posture, screen fatigue, self-healing, stress management, techstress, Uncategorized, vision, zoom fatigue | Tags: communication, myopia, pedestrian deaths, peripheral vision, text neck 7 CommentsAdapted from: Peper, E. & Harvey, R. (2024). Cell phones affects social communication, vision, breathing, and mental and physical health: What to do! TownsendLetter-The Examiner of Alternative Medicine,September 15, 2024. https://townsendletter.com/smartphone-affects-social-communication-vision-breathing-and-mental-and-physical-health-what-to-do/

Abstract

Smartphones are an indispensable part of our lives. Unfortunately too much of a ‘good thing’ regarding technology can work against us, leading to overuse, which in turn influences physical, mental and emotional development among current ‘Generation Z’ and ‘Millennial’ users (e.g., born 1997-2012, and 1981-1996, respectively). Compared to older technology users, Generation Z report more mental and physical health problems. Categories of mental health include attentional deficits, feelings of depression, anxiety social isolation and even suicidal thoughts, as along with physical health complaints such as sore neck and shoulders, eyestrain and increase in myopia. Long duration of looking downward at a smartphone affects not only eyestrain and posture but it also affects breathing which burden overall health. The article provides evidence and practices so show how technology over use and slouching posture may cause a decrease in social interactions and increases in emotional/mental and physical health symptoms such as eyestrain, myopia, and body aches and pains. Suggestions and strategies are provided for reversing the deleterious effects of slouched posture and shallow breathing to promote health.

We are part of an uncontrolled social experiment

We, as technology users, are all part of a social experiment in which companies examine which technologies and content increase profits for their investors (Mason, Zamparo, Marini, & Ameen, 2022). Unlike University research investigations which have a duty to warn of risks associated with their projects, we as participants in ‘profit-focused’ experiments are seldom fully and transparently informed of the physical, behavioral and psychological risks (Abbasi, Jagaveeran, Goh, & Tariq, 2021; Bhargava, & Velasquez, 2021). During university research participants must be told in plain language about the risks associated with the project (Huh-Yoo & Rader, 2020; Resnik, 2021). In contrast for-profit technology companies make it possible to hurriedly ‘click through’ terms-of-service and end-user-license-agreements, ‘giving away’ our rights to privacy, then selling our information to the highest bidder (Crain, 2021; Fainmesser, Galeotti, & Momot, 2023; Quach et al., 2022; Yang, 2022).

Although some people remain ignorant and or indifferent (e.g., “I don’t know and I don’t care”) about the use of our ‘data,’ an unintended consequence of becoming ‘dependent’ on technology overuse includes the strain on our mental and physical health (Abusamak, Jaber & Alrawashdeh, 2022; Padney et al., 2020). We have adapted new technologies and patterns of information input without asking the extent to which there were negative side effects (Akulwar-Tajane, Parmar, Naik & Shah, 2020; Elsayed, 2021). As modern employment shifted from predominantly blue-collar physical labor to white collar information processing jobs, people began sitting more throughout the day. Workers tended to look down to read and type. ‘Immobilized’ sitting for hours of time has increased as people spend time working on a computer/laptop and looking down at smartphones (Park, Kim & Lee, 2020). The average person now sits in a mostly immobilized posture 10.4 hours/day and modern adolescents spent more than two thirds of their waking time sitting and often looking down at their smartphones (Blodgett, et al., 2024; Arundell et al., 2019).

Smartphones are an indispensable part of our lives and is changing the physical and mental emotional development especially of Generation Z who were born between 1997-2012 (Haidt, 2024). They are the social media and smartphone natives (Childers & Boatwright, 2021). The smartphone is their personal computer and the gateway to communication including texting, searching, video chats, social media (Hernandez-de-Menendez, Escobar Díaz, & Morales-Menendez, 2020; Nichols, 2020; Schenarts, 2020; Szymkowiak et al., 2021). It has 100,000 times the processing power of the computer used to land the first astronauts on the moon on July 20, 1969 according to University of Nottingham’s computer scientist Graham Kendal (Dockrill, 2020). More than one half of US teens spend on the average more than 7 hours on daily screen time that includes watching streaming videos, gaming, social media and texting and their attention span has decreased from 150 seconds in 2004 to an average of 44 seconds in 2021 (Duarte, F., 2023; Mark, 2022, p. 96).

For Generation Z, social media use is done predominantly with smartphones while looking down. It has increased mental health problems such as attentional deficits, depression, anxiety suicidal thoughts, social isolation as well as decreased physical health (Haidt, 2024; Braghieri et al., 2023; Orsolini, Longo & Volpe, 2023; Satılmış, Cengız, & Güngörmüş, 2023; Muchacka-Cymerman, 2022; Fiebert, Kistner, Gissendanner & DaSilva, 2021; Mohan et al., 2021; Goodwin et al., 2020).

The shift in communication from synchronous (face-to-face) to asynchronous (texting) has transformed communications and mental health as it allows communication while being insulated from the other’s reactions (Lewis, 2024). The digital connection instead of face-to-face connection by looking down at the smart phone also has decreased the opportunity connect with other people and create new social connections, with three typical hypotheses examining the extent to which digital technologies (a) displace/ replace; (b) compete/ interfere with; and/or, (c) complement/ enhance in-person activities and relationships (Kushlev & Leitao, 2020).

As described in detail by Jonathan Haidt (2024), in his book, The Anxious Generation, the smartphone and the addictive nature of social media combined with the reduction in exercise, unsupervised play and childhood independence was been identified as the major factors in the decrease in mental health in your people (Gupta, 2023). This article focuses less on distraction such as attentional deficits, or dependency leading to tolerance, withdrawal and cravings (e.g., addiction-like symptoms) and focuses more on ‘dysregulation’ of body awareness (posture and breathing changes) and social communication while people are engaged with technology (Nawaz,Bhowmik, Linden & Mitchell, 2024).

The excessive use of the smartphones is associated with a significant reduction of physical activity and movement leading to a so-called sedentarism or increases of sitting disease (Chandrasekaran & Ganesan, 2021; Nakshine, Thute, Khatib, & Sarkar, 2022). Unbeknown to the smartphone users their posture changes, as they looks down at their screen, may also affect their mental and physical health (Aliberti, Invernizzi, Scurati & D’lsanto, 2020).

(1) Explore how looking at your smartphone affects you (adapted from: Peper, Harvey, & Rosegard, 2024)

For a minute, sit in your normal slouched position and look at your smartphone while intensely reading the text or searching social media. For the next minute sit tall and bring the cell phone in front of you so you can look straight ahead at it. Again, look at your smartphone while intensely reading the text or searching social media.

Compare how the posture affects you. Most likely, your experience is similar to the findings from students in a classroom observational study. Almost all experienced a reduction in peripheral awareness and breathed more shallowly when they slouched while looking at their cellphone.

Decreased peripheral awareness and increased shallow breathing that affects physical and mental health and performance. The students reported looking down position reduces the opportunity of creating new social connections. Looking down my also increases the risk for depression along with reduced cognitive performance during class (Peper et al., 2017; Peper et al., 2018).

(2) Explore how posture affects eye contact (adapted from the exercise shared by Ronald Swatzyna, 2023)[2]

Walk around your neighborhood or through campus either looking downwards or straight ahead for 30 minutes while counting the number of eye contacts you make.

Most likely, when looking straight ahead and around versus slouched and looking down you had the same experience as Ronald Swatzyna (2023), Licensed Clinical Social Worker. He observed that when he walked a three-mile loop around the park in a poor posture with shoulders forward in a head down position, and then reversed direction and walked in good posture with the shoulders back and the head level, he would make about five times as many eye contacts with a good posture compared to the poor posture.

Anecdotal observations, often repeated by many educators, suggest before the omnipresent smartphone, students would look around and talk to each other before a university class began. Now, when Generation Z students enter an in-person class, they sit down, look down at their phone and tend not to interact with other students.

(3) Experience the effect of face-to-face in-person communication

During the first class meeting, ask students to put their cellphones away, meet with three or four other students for a few minutes, and share a positive experience that happened to them last week as well as what they would like to learn in the class. After a few minutes, ask them to report how their energy and mood changed.

In our observational class study with 24 junior and senior college students in the in-person class and 54 students in the online zoom class, almost all report that that their energy and positive mood increased after they interacted with each other. The effects were more beneficial for the in-person small group sharing than the online breakout groups sharing on Zoom as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Change in subjective energy and mood after sharing experiences synchronously in small groups either in-person or online.

Without direction of a guided exercise to increase social connections, students tend to stay within their ‘smartphone bubble’ while looking down (Bochicchio et al., 2022). As a result, they appear to be more challenged to meet and interact with other people face-to-face or by phone as is reflected in the survey data that Generation Z is dating much less and more lonely than the previous generations (Cox et al., 2023).

What to do:

- Put the smartphone away so that you do not see it in social settings such as during meals or classes. This means that other people can be present with you and the activity of eating or learning.

- Do not permit smartphones in the classroom including universities unless it is required for a class assignment.

- In classrooms and in the corporate world, create activities that demands face-to-face synchronous communication.

- Unplug from the audio programs when walking and explore with your eyes what is going on around you.

(4) Looking down increases risk of injury and death

Looking down at a close screen reduces peripheral awareness and there by increases the risk of accidents and pedestrian deaths. Pedestrian deaths are up 69% since 2011 (Cova, 2024) and have consistently increased since the introduction of the iPhone in 2007 as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Increase in pedestrian death since the introduction of the iphone (data plotted from https://www.iihs.org/topics/fatality-statistics/detail/pedestrians)

In addition, the increase use of mobile phones is also associated with hand and wrist pain from overuse and with serious injuries such as falls and texting while driving due to lack of peripheral awareness. McLaughlin et al (2023) reports an increase in hand and wrist injuries as well serious injuries related to distracted behaviors, such as falls and texting while driving. The highest phone related injuries (lacerations) as reported from the 2011 to 2020 emergency room visits were people in the age range from 11–20 years followed by 21–30 years.

What to do:

- Do not walk while looking at your smartphone. Attend to the environment around you.

- Unplug from the audio podcasts when walking and explore with your eyes what is going on around you.

- Sit or stop walking when answering the smartphone to reduce the probability of an accident.

- For more pragmatic suggestions, see the book, TechStress: How Technology is Hijacking Our Lives, Strategies for Coping, and Pragmatic Ergonomics, by Peper, Harvey and Faass (2020).

(5) Looking at screens increases the risk of myopia

Looking at a near screen for long periods of time increases the risk of myopia (near sightedness) which means that distant vision is more blurry. Myopia has increased as children predominantly use computers or, smartphones with smaller screen at shorter distances. By predominantly focusing on nearby screens without allowing the eye to relax remodels the eyes structure. Consequently, myopia has increase in the U.S. from 25 percent in the early 1970s to nearly 42 percent three decades later (OHSU, 2022).

Looking only at nearby screens, our eyes converge and the ciliary muscles around the lens contract and remain contracted until the person looks at the far distance. The less opportunity there is to allow the eyes to look at distant vision, the more myopia occurs. in Singapore 80 per cent of young people aged 18 or below have nearsightedness and 20 % of the young people have high myopia as compared to 10 years ago (Singapore National Eye Centre, 2024). The increase in myopia is a significant concern since high myopia is associated with an increased risk of vision loss due to cataract, glaucoma, and myopic macular degeneration (MMD). MMD is rapidly increasing and one of the leading causes of blindness in East Asia that has one of the highest myopia rates in the world (Sankaridurg et al., 2021).

What to do:

- Every 20 minutes stop looking at the screen and look at the far distance to relax the eyes for 20 seconds.

- Do not allow young children access to cellphones or screens. Let them explore and play in nature where they naturally alternate looking at far and near objects.

- Implement the guided eye regenerating practices descrubed in the article, Resolve eyestrain and screen fatigue, by Peper (2021).

- Read Meir Schneider’s (2016) book, Vision for Life, for suggestions how to maintain and improve vision.

(6) Looking down increases tech neck discomfort

Looking down at the phone while standing or sitting strains the neck and shoulder muscles because of the prolonged forward head posture as illustrated in the YouTube video, Tech Stress Symptoms and Causes (DeWitt, 2018). Using a smartphone while standing or walking causes a significant increase in thoracic kyphosis and trunk (Betsch et al., 2021). When the head is erect, the muscle of the neck balance a weight of about 10 to 12 pounds or, approximately 5 kilograms; however, when the head is forward at 60 degrees looking at your cell phone the forces on the muscles are about 60 pound or more than 25 kilograms, as illustrated in Figure 4 (Hansraj, 2014).

Figure 4. The head forward position puts as much as sixty pounds of pressure on the neck muscles and spine (by permission from Dr. Kenneth Hansraj, 2014).

This process is graphically illustrated in the YouTube video, Text Neck Symptoms and Causes Video, produced by Veritas Health (2020).

What to do:

- Keep the phone in front of you so that you do not slouch down by having your elbow support on the table.

- Every ten minutes stretch, look up and roll your shoulders backwards.

- Wear a posture feedback device such as the UpRight Go 2 to remind you when you slouch to change posture and activity (Peper et al., 2019; Stuart, Godfrey & Mancini, 2022).

- Take Alexander Technique lessons to improve your posture (Cacciatore, Johnson, & Cohen, 2020; AmAT, 2024; STAT, 2024).

(7) Looking down increases negative memory recall and depression

In our previous research, Peper et al. (2017) have found that recalling hopeless, helpless, powerless, and defeated memories is easier when sitting in a slouched position than in an upright position. Recalling positive memories is much easier when sitting upright and looking slightly upward than sitting slouched position. If attempting to recall positive memories the brain has to work hard as indicated by an significantly higher amplitudes of beta2, beta3, and beta4 EEG (i.e., electroencephalograph) when sitting slouched then when sitting upright (Tsai et al., 2016).

Not only does the postural position affect memory recall, it also affects mental math under time-pressure performance. When students sit in a slouched position, they report that is much more difficult to do mental math (serial 7ths) than when in the upright position (Peper et al., 2018). The effect of posture is most powerful for the 70% of students who reported that they blanked out on exams, were anxious, or worried about class performance or math. For the 30% who reported no performance anxiety, posture had no significant effect. When students become aware of slouching thought posture feedback and then interrupt their slouching by sitting up, they report an increase in concentration, attention and school performance (Peper et al., 2024).

How we move and walk also affects our subjective energy. In most cases, when people sit for a long time, they report feeling more fatigue; however, if participants interrupt sitting with short movement practices they report becoming less fatigue and improved cognition (Wennberg et al., 2016). The change in subjective energy and mood depends upon the type of movement practice. Peper & Lin (2012) reported that when students were asked to walk in a slow slouching pattern looking down versus to walk quickly while skipping and looking up, they reported that skipping significantly increased their subjective energy and mood while the slouch walking decreased their energy. More importantly, student who had reported that they felt depressed during the last two years had their energy decrease significantly more when walking very slowly while slouched than those who did not report experiencing depression. Regardless of their self-reported history of depression, when students skipped, they all reported an increase in energy (Peper & Lin, 2012; Miragall et al., 2020).

What to do:

- Walk with a quick step while looking up and around.

- Wear a posture feedback device such as the UpRight Go 2 to remind you when you slouch to change posture and activity (Peper et al., 2019; Roggio et al., 2021).

- When sitting put a small pillow in the mid back so that you can sit more erect (for more suggestions, see the article by Peper et al., 2017a, Posture and mood: Implications and applications to therapy).

- Place photo and other objects that you like to look a slightly higher on your wall so that you automatically look up.

(8) Shallow breathing increases the risk for anxiety

When slouching we automatically tend to breathe slightly faster and more shallowly. This breathing pattern increases the risk for anxiety since it tends to decrease pCO2 (Feinstein et al., 2022; Meuret, Rosenfield, Millard & Ritz, 2023; Paulus, 2013; Smits et al., 2022; Van den Bergh et al., 2013). Sitting slouched also tends to inhibit abdominal expansion during the inhalation because the waist is constricted by clothing or a belt –sometimes labeled as ‘designer jean syndrome’ and may increase abdominal symptoms such as acid reflux and irritable bowel symptoms (Engeln & Zola, 2021; Peper et al., 2016; Peper et al., 2020). When students learn diaphragmatic breathing and practice diaphragmatic breathing whenever they shallow breathe or hold their breath, they report a significant decrease in anxiety, abdominal symptoms and even menstrual cramps (Haghighat et al., 2020; Peper et al., 2022; Peper et al., 2023).

What to do:

- Loosen your belt and waist constriction when sitting so that the abdomen can expand.

- Learn and practice effortless diaphragmatic breathing to reduce anxiety.

Conclusion

There are many topics related to postural health and technology overuse that were addressed in this article. Some topics are beyond the scope of the article, and therefore seen as limitations. These relate to diagnosis and treatment of attentional deficits, or dependency leading to tolerance, withdrawal and cravings (e.g., addiction-like symptoms), or of modeling relationships between factors that contribute to the increasing epidemic of mental and physical illness associated with smartphone use and social media, such as hypotheses examining the extent to which digital technologies (a) displace/ replace; (b) compete/ interfere with; and/or, (c) complement/ enhance in-person activities and relationships. Typical pharmaceutical ‘treat-the-symptom’ approaches for addressing ‘tech stress’ related to technology overuse includes prescribing ‘anxiolytics, pain-killers and muscle relaxants’ (Kazeminasab et al., 2022; Kim, Seo, Abdi, & Huh, 2020). Although not usually included in diagnosis and treatment strategies, suggesting improving posture and breathing practices can significantly affect mental and physical health. By changing posture and breathing patterns, individuals may have the option to optimize their health and well-being.

See the book, TechStress-How Technology is Hijacking our Lives, Strategies for Coping and Pragmatic Ergonomics by Erik Peper, Richard Harvey and Nancy Faass. Available from: https://www.amazon.com/Beyond-Ergonomics-Prevent-Fatigue-Burnout/dp/158394768X/

Explore the following blogs for more background and useful suggestions

References

Abbasi, G. A., Jagaveeran, M., Goh, Y. N., & Tariq, B. (2021). The impact of type of content use on smartphone addiction and academic performance: Physical activity as moderator. Technology in Society, 64, 101521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101521

Abusamak, M., Jaber, H. M., & Alrawashdeh, H. M. (2022). The effect of lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic on digital eye strain symptoms among the general population: a cross-sectional survey. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 895517. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.895517

Akulwar-Tajane, I., Parmar, K. K., Naik, P. H., & Shah, A. V. (2020). Rethinking screen time during COVID-19: impact on psychological well-being in physiotherapy students. Int J Clin Exp Med Res, 4(4), 201-216. https://doi.org/10.26855/ijcemr.2020.10.014

Aliberti, S., Invernizzi, P. L., Scurati, R., & D’Isanto, T. (2020). Posture and skeletal muscle disorders of the neck due to the use of smartphones. Journal of Human Sport and Exercise , 15 (3proc), S586-S598. https://www.jhse.ua.es/article/view/2020-v15-n3-proc-posture-skeletal-muscle-disorders-neck-smartpho; https://air.unimi.it/retrieve/handle/2434/774436/1588570/HSE%20-%20Posture%20and%20skeletal%20muscle%20disorders.pdf

AmSAT. (2024). American Society for the Alexander Technique. Accessed July 27, 2024. https://alexandertechniqueusa.org/

Arundell, L., Salmon, J., Koorts, H. et al. (2019). Exploring when and how adolescents sit: cross-sectional analysis of activPAL-measured patterns of daily sitting time, bouts and breaks. BMC Public Health 19, 653. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6960-5

Bhargava, V. R., & Velasquez, M. (2021). Ethics of the attention economy: The problem of social media addiction. Business Ethics Quarterly, 31(3), 321-359. https://doi.org/10.1017/beq.2020.32

Betsch, M., Kalbhen, K., Michalik, R., Schenker, H., Gatz, M., Quack, V., Siebers, H., Wild, M., & Migliorini, F. (2021). The influence of smartphone use on spinal posture – A laboratory study. Gait Posture, 85, 298-303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2021.02.018

Blodgett, J.M., Ahmadi, M.N., Atkin, A.J., Chastin, S., Chan, H-W., Suorsa, K., Bakker, E.A., Hettiarcachchi, P., Johansson, P.J., Sherar,L. B., Rangul, V., Pulsford, R.M…. (2024). ProPASS Collaboration , Device-measured physical activity and cardiometabolic health: the Prospective Physical Activity, Sitting, and Sleep (ProPASS) consortium, European Heart Journal, 45(6) 458–471, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad717

Bochicchio, V., Keith, K., Montero, I., Scandurra, C., & Winsler, A. (2022). Digital media inhibit self-regulatory private speech use in preschool children: The “digital bubble effect”. Cognitive Development, 62, 101180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogdev.2022.101180

Braghieri, L., Levy, R., & Makarin, A. (2022). Social Media and Mental Health (July 28, 2022). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3919760 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3919760

Cacciatore, T. W., Johnson, P. M., & Cohen, R. G. (2020). Potential mechanisms of the Alexander technique: Toward a comprehensive neurophysiological model. Kinesiology Review, 9(3), 199-213. https://doi.org/10.1123/kr.2020-0026

Chandrasekaran, B., & Ganesan, T. B. (2021). Sedentarism and chronic disease risk in COVID 19 lockdown–a scoping review. Scottish Medical Journal, 66(1), 3-10. https://doi.org/10.1177/0036933020946336

Childers, C., & Boatwright, B. (2021). Do digital natives recognize digital influence? Generational differences and understanding of social media influencers. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 42(4), 425-442. https://doi.org/10.1080/10641734.2020.1830893

Cox, D.A., Hammond, K.E., & Gray, K. (2023). Generation Z and the Transformation of American Adolescence: How Gen Z’s Formative Experiences Shape Its Politics, Priorities, and Future. Survey Center of American Life, November 23, 2023. Accessed July 4, 2024. https://www.americansurveycenter.org/research/generation-z-and-the-transformation-of-american-adolescence-how-gen-zs-formative-experiences-shape-its-politics-priorities-and-future/

Crain, M. (2021). Profit over privacy: How surveillance advertising conquered the internet. U of Minnesota Press. https://www.amazon.com/Profit-over-Privacy-Surveillance-Advertising/dp/1517905044

Cova, E. (2024). Pedestrian fatalities at historic high. Smart Growth America (data from U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT). Accessed July 2, 2024. https://smartgrowthamerica.org/pedestrian-fatalities-at-historic-high/

Duarte, F. (2023). Average Screen Time for Teens (2024). Exploding Topics. Accessed July 5, 2024. https://explodingtopics.com/blog/screen-time-for-teens#average

DeWitt, D. (2018). How Does Text Neck Cause Pain? Spine-Health October 26, 2018. Accessed July 5, 2024. https://www.spine-health.com/conditions/neck-pain/how-does-text-neck-cause-pain

Dockrill, P. (2020). Your laptop charger is more powerful than Apollo11’s computer, says apple developer. Science Alert, Janural 12, 2020. Accessed July 4, 2024. https://www.sciencealert.com/apollo-11-s-computer-was-less-powerful-than-a-usb-c-charger-programmer-discovers

Elsayed, W. (2021). Covid-19 pandemic and its impact on increasing the risks of children’s addiction to electronic games from a social work perspective. Heliyon, 7(12). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08503

Engeln, R., & Zola, A. (2021). These boots weren’t made for walking: gendered discrepancies in wearing painful, restricting, or distracting clothing. Sex roles, 85(7), 463-480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-021-01230-9

Fainmesser, I. P., Galeotti, A., & Momot, R. (2023). Digital privacy. Management Science, 69(6), 3157-3173. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2022.4513

Feinstein, J. S., Gould, D., & Khalsa, S. S. (2022). Amygdala-driven apnea and the chemoreceptive origin of anxiety. Biological psychology, 170, 108305. https://10.1016/j.biopsycho.2022.108305

Fiebert, I., Kistner, F., Gissendanner, C., & DaSilva, C. (2021). Text neck: An adverse postural phenomenon. Work, 69(4), 1261-1270. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-213547

Goodwin, R. D., Weinberger, A. H., Kim, J. H., Wu. M., & Galea, S. (2020). Trends in anxiety among adults in the United States, 2008–2018: Rapid increases among young adults. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 130, 441–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.08.014

Gupta, N. (2023). Impact of smartphone overuse on health and well-being: review and recommendations for life-technology balance. Journal of Applied Sciences and Clinical Practice, 4(1), 4-12. https://doi.org/10.4103/jascp.jascp_40_22

Haghighat, F., Moradi, R., Rezaie, M., Yarahmadi, N., & Ghaffarnejad, F. (2020). Added Value of Diaphragm Myofascial Release on Forward Head Posture and Chest Expansion in Patients with Neck Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Research Square. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-53279/v1

Haidt, J. (2024). The Anxious generation: How the great rewiring of childhood is causing an epidemic of mental illness. New York: Penguin Press. https://www.anxiousgeneration.com/book

Hansraj, K.K. (2014). Assessment of stresses in the cervical spine caused by posture and position of the head. Surg Technol Int. 25, 277-279. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25393825/

Hernandez-de-Menendez, M., Escobar Díaz, C. A., & Morales-Menendez, R. (2020). Educational experiences with Generation Z. International Journal on Interactive Design and Manufacturing (IJIDeM), 14(3), 847-859. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12008-020-00674-9

Huh-Yoo, J., & Rader, E. (2020). It’s the Wild, Wild West: Lessons learned from IRB members’ risk perceptions toward digital research data. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 4(CSCW1), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1145/3392868

IIHS (2024). Fatality Facts 2022Pedestrians. The Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS). Accessed July 2, 2024. https://www.iihs.org/topics/fatality-statistics/detail/pedestrians

Kazeminasab, S., Nejadghaderi, S. A., Amiri, P., Pourfathi, H., Araj-Khodaei, M., Sullman, M. J., … & Safiri, S. (2022). Neck pain: global epidemiology, trends and risk factors. BMC musculoskeletal disorders, 23, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-021-04957-4

Kim, K. H., Seo, H. J., Abdi, S., & Huh, B. (2020). All about pain pharmacology: what pain physicians should know. The Korean journal of pain, 33(2), 108-120. https://doi.org/10.3344/kjp.2020.33.2.108

Kushlev, K., & Leitao, M. R. (2020). The effects of smartphones on well-being: Theoretical integration and research agenda. Current opinion in psychology, 36, 77-82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.05.001

Lewis, H.R. (2024). Mechanical intelligence and counterfeit humanity. Harvard Magazine, 126(6), 38-40. https://www.harvardmagazine.com/2024/07/harry-lewis-computers-humanity#google_vignette

Mark, G. (2023). Attention Span: A Groundbreaking Way to Restore Balance, Happiness and Productivity. Toronto, Canada: Hanover Square Press. https://www.amazon.com/Attention-Span-Finding-Fighting-Distraction-ebook/dp/B09XBJ29W9

Mason, M. C., Zamparo, G., Marini, A., & Ameen, N. (2022). Glued to your phone? Generation Z’s smartphone addiction and online compulsive buying. Computers in Human Behavior, 136, 107404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107404

McLaughlin, W.M., Cravez, E., Caruana, D.L., Wilhelm, C., Modrak, M., & Gardner, E.C. (2023). An Epidemiological Study of Cell Phone-Related Injuries of the Hand and Wrist Reported in United States Emergency Departments From 2011 to 2020. J Hand Surg Glob, 5(2),184-188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsg.2022.11.009

Meuret, A. E., Rosenfield, D., Millard, M. M., & Ritz, T. (2023). Biofeedback Training to Increase Pco2 in Asthma With Elevated Anxiety: A One-Stop Treatment of Both Conditions?. Psychosomatic medicine, 85(5), 440-448. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000001188

Miragall, M., Borrego, A., Cebolla, A., Etchemendy, E., Navarro-Siurana, J., Llorens, R., … & Baños, R. M. (2020). Effect of an upright (vs. stooped) posture on interpretation bias, imagery, and emotions. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 68, 101560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2020.101560

Mohan, A., Sen, P., Shah, C., Jain, E., & Jain, S. (2021). Prevalence and risk factor assessment of digital eye strain among children using online e-learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: Digital eye strain among kids (DESK study-1). Indian journal of ophthalmology, 69(1), 140-144. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijo.IJO_2535_20

Muchacka-Cymerman, A. (2022). ‘I wonder why sometimes I feel so angry’ The associations between academic burnout, Facebook intrusion, phubbing, and aggressive behaviours during pandemic Covid 19. Polish Psychological Bulletin, 53(4). https://doi.org/10.24425/ppb.2022.143376

Nakshine, V. S., Thute, P., Khatib, M. N., & Sarkar, B. (2022). Increased screen time as a cause of declining physical, psychological health, and sleep patterns: a literary review. Cureus, 14(10). https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.30051

Nawaz, S., Bhowmik, J., Linden, T., & Mitchell, M. (2024). Validation of a modified problematic use of mobile phones scale to examine problematic smartphone use and dependence. Heliyon, 10(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e24832

Nicholas, A. J. (2020). Preferred learning methods of generation Z. Faculty and Staff – Articles & Papers. Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. Salve Regina University. https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/fac_staff_pub/74

OHSU. (2022). Myopia on the rise, especially among children. Casey Eye Institute. Oregan Health and Science University. Accessed July 7, 2024. https://www.ohsu.edu/casey-eye-institute/myopia-rise-especially-among-children

Orsolini, L., Longo, G., & Volpe, U. (2023). The mediatory role of the boredom and loneliness dimensions in the development of problematic internet use. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 4446. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054446

Pandey, R., Gaur, S., Kumar, R., Kotwal, N., & Kumar, S. (2020). Curse of the technology-computer related musculoskeletal disorders and vision syndrome: a study. International Journal of Research in Medical Sciences, 8(2), 661. https://doi.org/10.18203/2320-6012.ijrms20200253

Park, J. C., Kim, S., & Lee, H. (2020). Effect of work-related smartphone use after work on job burnout: Moderating effect of social support and organizational politics. Computers in human behavior, 105, 106194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.106194

Paulus, M.P. (2013). The breathing conundrum-interoceptive sensitivity and anxiety. Depress Anxiety.30(4), 315-20. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22076

Peper, E. (2021). Resolve eyestrain and screen fatigue. Well Being Journal, 30(1), 24-28. https://wellbeingjournal.com/resolve-eyestrain-and-screen-fatigue/

Peper, E., Booiman, A., Lin, I-M, Harvey, R., & Mitose, J. (2016). Abdominal SEMG Feedback for Diaphragmatic Breathing: A Methodological Note. Biofeedback. 44(1), 42-49. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-44.1.03

Peper, E., Chen, S., Heinz, N. & Harvey, R. (2023). Hope for menstrual cramps (dysmenorrhea) with breathing. Biofeedback, 51(2), 44–51. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-51.2.04

Peper, E., Harvey, R., Cuellar, Y., & Membrila, C. (2022). Reduce anxiety. NeuroRegulation, 9(2), 91–97. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.9.2.91

Peper, E., Harvey, R. & Faass, N. (2020). TechStress: How Technology is Hijacking Our Lives, Strategies for Coping, and Pragmatic Ergonomics. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books. https://www.amazon.com/Beyond-Ergonomics-Prevent-Fatigue-Burnout/dp/158394768X

Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Mason, L. (2019). “Don’t slouch!” Improve health with posture feedback. Townsend Letter-The Examiner of Alternative Medicine, 436, 58-61. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/337424599_Don%27t_slouch_Improve_health_with_posture_feedback

Peper, E., Harvey, R., Mason, L., & Lin, I.-M. (2018). Do better in math: How your body posture may change stereotype threat response. NeuroRegulation, 5(2), 67–74. http://dx.doi.org/10.15540/nr.5.2.67

Peper, E., Harvey, R. & Rosegard, E. (2024). Increase attention, concentration and school performance with posture feedback. Biofeedback, 52(2). https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-52.02.07

Peper, E. & Lin, I-M. (2012). Increase or decrease depression-How body postures influence your energy level. Biofeedback, 40 (3), 126-130. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-40.3.01

Peper, E., Lin, I-M, & Harvey, R. (2017a). Posture and mood: Implications and applications to therapy. Biofeedback, 35(2), 42-48. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-45.2.03

Peper, E., Lin, I-M., Harvey, R., & Perez, J. (2017). How posture affects memory recall and mood. Biofeedback.45 (2), 36-41. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-45.2.01

Peper, E., Mason, L., Harvey, R., Wolski, L, & Torres, J. (2020). Can acid reflux be reduced by breathing? Townsend Letters-The Examiner of Alternative Medicine, 445/446, 44-47. https://www.townsendletter.com/article/445-6-acid-reflux-reduced-by-breathing/

Quach, S., Thaichon, P., Martin, K. D., Weaven, S., & Palmatier, R. W. (2022). Digital technologies: tensions in privacy and data. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 50(6), 1299-1323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-022-00845-y

Resnik, D. B. (2021). Standards of evidence for institutional review board decision-making. Accountability in research, 28(7), 428-455. https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2020.1855149

Roggio, F., Ravalli, S., Maugeri, G., Bianco, A., Palma, A., Di Rosa, M., & Musumeci, G. (2021). Technological advancements in the analysis of human motion and posture management through digital devices. World journal of orthopedics, 12(7), 467. https://doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v12.i7.467

Sankaridurg, P., Tahhan, N., Kandel, H., Naduvilath, T., Zou, H., Frick,K.D., Marmamula, S., Friedman, D.S., Lamoureux, e. Keeffe, J. Walline, J.J., Fricke, T.R., Kovai, V., & Resnikoff, S. (2021) IMI Impact of Myopia. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci, 62(5), 2. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.62.5.2

Satılmış, S. E., Cengız, R., & Güngörmüş, H. A. (2023). The relationship between university students’ perception of boredom in leisure time and internet addiction during social isolation process. Bağımlılık Dergisi, 24(2), 164-173. https://doi.org/10.51982/bagimli.1137559

Schenarts, P. J. (2020). Now arriving: surgical trainees from generation Z. Journal of surgical education, 77(2), 246-253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2019.09.004

Schneider, M. (2016). Vision for life. Ten Steps to Natural Eyesight Improvement. Berkeley: North Atlantic books. https://www.amazon.com/Vision-Life-Revised-Eyesight-Improvement/dp/1623170087

Singapore National Eye Centre. (2024). Severe myopia cases among children in Singapore almost doubled in past decade. CAN. Accessed July 4, 2024. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/singapore/myopia-children-cases-almost-double-glasses-eye-checks-4250266

Smits, J. A., Monfils, M. H., Otto, M. W., Telch, M. J., Shumake, J., Feinstein, J. S., … & Exposure Therapy Consortium. (2022). CO2 reactivity as a biomarker of exposure-based therapy non-response: study protocol. BMC psychiatry, 22(1), 831. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-04478-x

STAT (2024). The society of teachers of the Alexander Technique. Assessed July 27, 2024. https://alexandertechnique.co.uk/

Stuart, S., Godfrey, A., & Mancini, M. (2022). Staying UpRight in Parkinson’s disease: A pilot study of a novel wearable postural intervention. Gait & Posture, 91, 86-93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2021.09.202

Swatzyna, R. (2023). Personal communications.

Szymkowiak, A., Melović, B., Dabić, M., Jeganathan, K., & Kundi, G. S. (2021). Information technology and Gen Z: The role of teachers, the internet, and technology in the education of young people. Technology in Society, 65, 101565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101565

Tsai, H. Y., Peper, E., & Lin, I. M.*(2016). EEG patterns under positive/negative body postures and emotion recall tasks. NeuroRegulation, 3(1), 23-27. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.3.1.23

Van den Bergh, O., Zaman, J., Bresseleers, J., Verhamme, P., Van Diest, I. (2013). Anxiety, pCO2 and cerebral blood flow, International Journal of Psychophysiology, 89 (1), 72-77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2013.05.011

Veritas Health. (2020). Text Neck Symptoms and Causes Video. YouTube video, accessed August 29, 2024. https://www.spine-health.com/conditions/neck-pain/how-does-text-neck-cause-pain?source=YT

Wennberg, P., Boraxbekk, C., Wheeler, M., et al. (2016). Acute effects of breaking up prolonged sitting on fatigue and cognition: a pilot study. BMJ Open, 6, e009630. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009630

Yang, K. H. (2022). Selling consumer data for profit: Optimal market-segmentation design and its consequences. American Economic Review, 112(4), 1364-1393. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles/pdf/doi/10.1257/aer.20210616

[1] Correspondence should be addressed to: Erik Peper, Ph.D., Institute for Holistic Health Studies, Department of Recreation, Parks, Tourism and Holistic Health, San Francisco State University, 1600 Holloway Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94132 Email: epeper@sfsu.edu; web: www.biofeedbackhealth.org; blog: www.peperperspective.com

[2] I thank Ronald Swatzyna (2023), Licensed Clinical Social Worker for sharing this exercise with me. He discovered that a difference in the number of eye contacts depending how he walked. When he walked a 3.1 mile loop around the park in a poor posture- shoulders forward, head down position- and then reversed direction and walked in good posture with the shoulders back and the head level, that that he make about 5 times as many eye contacts with good posture compared to the poor posture. He observed that he make about five times as many eye contacts with good posture as compared to the poor posture.

Improve learning with peak performance techniques

Posted: August 12, 2021 Filed under: ADHD, behavior, digital devices, education, educationj, screen fatigue, stress management, zoom fatigue | Tags: cueing, learning, optimum performance, peak performance, state dependent learning 3 CommentsErik Peper, PhD and Vietta Wilson, PhD

Adapted from: Peper, E. & Wilson, V. (2021). Optimize the learning state: techniques and habits. Biofeedback, 9(2), 46-49. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-49-2-04

Long after the COVID-19 pandemic is over, online learning will continue to increase as better methodologies and strategies are developed to implement and integrate it into our lives. This post provides suggestions on how to enhance the learner’s ability to engage while online with the use of pre-performance routines or habits.

Facilitating online learning requires coordination of the teacher, technology, student, environment and the topic. Teachers can enhance engagement (Shoepe et al., 2020) online through different types of prompts: intellectual (associated with instructor interaction, academic challenge, active learning), organizational (associated with enriching academic experiences by directing students, selecting topics and summarizing or redirecting), and social (associated with supportive campus environments by encouraging social interaction, using informal language and affirming student comments).

The student can enhance the satisfaction and quality of the online experience by having a good self-regulated learning style. Learning is impacted by motivation (beliefs about themselves or the task, perceived value, etc.), and metacognition (ability to plan, set goals, monitor and regulate their behavior and evaluate their performance) (Greene & Azevedo, 2010; Mega et al., 2014). While critical for learning, it does not provide information on how students can maintain their optimized performance long term, which is increasingly necessary during the pandemic but will possibly be the model of education and therapy of the future.

Habit can enhance performance across a life span.

Habit is a behavioral tendency tied to a specific context, such as learning to brush one’s teeth while young and continuing through life (Fiorella, 2020). Habits are related to self-control processes that are associated with higher achievement (Hagger, 2019). Sport performance extensively values habit, typically called pre-performance routine, in creating an ongoing optimized state of performance (Lautenbach et al., 2015; Lidor & Mayan, 2005; Mesagno et al., 2015). Habits or pre-performance routines are formed by repeating a behavior tied to a specific context and with continued repetition, wherein the mental association between the context and the response are strengthened. This shifts from conscious awareness to subconscious behavior that is then cued by the environment. The majority of one’s daily actions and behaviors are the results of these habits.

Failure to create a self-regulated learning habit impedes long-term success of students. It does take significant time and reinforcement to create the automaticity of a real-life habit. Lally et al. (2010) tracked real world activities (physical activity, eating, drinking water) and found habit formation varied from 18-254 days with a mean of 66 days. There was wide variability in the creation of the habit and some individuals never reached the stage of automaticity. Interestingly, those who performed the behavior with greater consistency were more likely to develop a habit.

The COVID pandemic resulted in many people working at home, which interrupted many of the covert habit patterns by which they automatically performed their tasks. A number of students reported that everything is the same and that they are more easily distracted from doing the tasks. As one student reported:

After a while, it all seems the same. Sitting and looking at the screen while working, taking classes, entertaining, streaming videos and socializing. The longer I sit and watch screens, the more I tend to feel drained and passive, and the more challenging it is to be present, productive and pay attention.

By having rituals and habits trigger behavior, it is easier to initiate and perform tasks. Students can use the strategies developed for peak performance in sports to optimize their performances so that they can achieve their personal best (Wilson & Peper, 2011; Peper et al., 2021). These strategies include environmental cueing and personal cueing.

Environmental cueing

By taking charge of your environment and creating a unique environment for each task, it is possible to optimize performance specific for each task. After a while, we do not have to think to configure ourselves for the task. It is no different than the sequence before going to sleep: you brush your teeth and if you forget, it feels funny and you probably will get up to brush your teeth.

Previously, many people, without awareness, would configure and reinforce themselves for work by specific tasks such as commuting to go work, being at a specific worksite to perform the work, wearing specific clothing, etc. (Peper et al., 2021). Now there are few or no specific cues tied to working; it tends to be all the same and it is no wonder that people feel less energized and focused.

Many people forget that learning and recall are state-dependent to where the information was acquired. The Zoom environment where we work or attend class is the same environment where we socialize, game, watch videos, message, surf the net and participate in social media. For most, there has been no habit developed for the new reality of in-home learning. To do this, the environment must be set up so the habit state (focused, engaged) is consistently paired with environmental, emotional, social and kinesthetic cues. The environment needs to be reproducible in many locations, situations, and mental states as possible. As illustrated by one student’s report.

To cue myself to get ready for learning, I make my cappuccino play the same short piece of music, wear the same sweater, place my inspiring poster behind my screen, turn off all software notifications and place the cell phone out of visual range.

A similar concept is used in the treatment of insomnia by making the bedroom the only room to be associated with sleep or intimacy (Irish et al., 2017; Suni, 2021). All other activities, arguing with your partner, eating, watching television, checking email, texting, or social media are done at other locations. Given enough time, the cues in the bedroom become the conditioned triggers for sleep and pleasure.

Create different environments that are unique to each category of Zoom involvement (studying, working, socializing, entertaining).

Pre COVID, we usually wore different clothing for different events (work versus party) or visited different environments for different tasks (religious locations for worship; a bar, coffee shop, or restaurant for social gathering). The specific tasks in a specified location had conscious and subconscious cues that included people, lighting, odors, sound or even drinks and food. These stimuli become the classically conditioned cues to evoke the appropriate response associated with the task, just as Pavlov conditioned dogs to salivate when the bell sound was paired with the presentation of meat. Taking charge of the conditioning process at home may help many people to focus on their task as so many people now use their bedroom, kitchen or living room for Zoom work that is not always associated with learning or work. The following are suggestions to create working/learning environments.

- Wear task-specific clothing just as you would have done going to work or school. When you plan to study or work, put on your work shirt. In time, the moment you put on the work shirt, you are cueing yourself to focus on studying/working. When finishing with working/studying, change your clothing.

- If possible, maintain a specific location for learning/working. When attending classes or working, sit at your desk with the computer on top of the desk. For games or communication tasks, move to another location.

- If you can’t change locations, arrange task-specific backgrounds for each category of Zoom tasks. Place a different background such as a poster or wall hanging behind the computer screen—one for studying/working, and another for entertainment. When finished with the specific Zoom event, take down the poster and change the background.

- Keep the sound appropriate to the workstation area. Try to duplicate what is your best learning/working sound scape.

Personal Cueing

Learning to become aware of and in control of one’s personal self is equally or more important than setting up the environment with cues that foster attention and learning. Practicing getting the body/mind into the learning state can become a habit that will be available in many different learning situations across one’s lifespan.

- Perform a specific ritual or pre-performance routine before beginning your task to create the learning/performing state. The ritual is a choreographed sequence of actions that gets you ready to perform. For example, some people like to relax before learning and find playing a specific song or doing some stretching before the session is helpful. Others sit at the desk, turn off all notifications, take a deep breath then look up and state to themselves: “I am now looking forward to working/studying and learning,” “focus” (whatever it may be). For some, their energy level is low and doing quick arm and hand movements, slapping their thighs or face, or small fast jumps may bring them to a more optimal state. For many people smell and taste are the most powerful conditioners, and coffee improves their attention level. Test out an assortment of activities that get your body and mind at the performance level. Practice and modify as necessary.

Just as in sport, the most reliable method is to set up oneself for the learning/performance state, because a person has less control over the environment. For example, when I observed the Romanian rhythmic gymnasts team members practice their routine during the warmup before the international competition, they would act as if it was the actual competition. They stood at the mat preparing their body/mind state, then they would bow to the imaginary judge, wait for a signal to begin, and then perform their routine. On the other hand, most of the American rhythmic gymnasts would just do their practice routine. For the Romanian athletes, the competition was the same as their rehearsal practice. No wonder, the Romanian athletes were much more consistent in their performance. Additionally, ritual helps buffer against uncertainty and anxiety (Hobson et al., 2017).

- Develop awareness of the body-mind state associated with optimum performance. This can be done by creating a ritual and an environment that evoke the optimum mental and emotional state for learning. As you configure yourself and your environment, explore how you physically feel when you are most focused and engaged. Identify what your posture, muscle tension, and body position feel like during these times, and identify what you are paying attention to. If your attention wanders, observe how you bring your attention back to the task. Does it help focus you to write summary notes or doodle? Do you flag important statements in your head and then visibly nod your head when you understand the concept? Or do you repeat an important cue word? Find what you do when you are optimally functioning. Then try to reproduce that same state that can be triggered by a key word that tells you what to focus on (e.g., listen to teacher, look at slide, etc.).

In summary, by becoming aware of and controlling one’s environment and personal states that are associated with productive learning, and then practicing them until they become a routine or habit, one can maximize all learning opportunities. This blog presented a few tips, techniques and cues that may help one to maximize attention and increase performance and learning while online.

I noticed when I took the time to prepare and ready myself to be focused and be present during the class, I no longer had to actively work to resist distractions; I was focused in the moment and not worried about emails, other assignments, what to make for dinner, etc…

References

Findlay-Thompson, S. and Mombourquette, P. (2014). Evaluation of a Flipped Classroom in an Undergraduate Business Course. Business Education & Accreditation, v. 6 (1), 63-71.https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2331035

Fiorella, L. (2020). The science of habit and its implications for student learning and ell-being. Educational Psychology Review, 32,603–625. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-020-09525-1

Greene, J. A., & Azevedo, R. (2010). The measurement of learners’ self-regulated cognitive and metacognitive processes while using computer-based learning environments. Educational Psychologist, 45(4), 203–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2010.515935

Hagger, M. S. (2019). Habit and physical activity: Theoretical advances, practical implications, and agenda. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 42, 118–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.12.007

Hobson, N. M., Bonk, D., & Inzlicht, M. (2017). Rituals decrease the neural response to performance failure. PeerJ, 5, e3363. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.3363

Irish, L. A., Kline, C. E., Gunn, H. E., Buysse, D. J., & Hall, M. H. (2015). The role of sleep hygiene in promoting public health: A review of empirical evidence. Sleep medicine reviews, 22, 23–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2014.10.001

Lally, P., VanJaarsveld, C. H., Potts, H. W., & Wardle, J. (2010). How habits are formed: Modelling habit formation the real world. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 998–1009. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.674

Lautenbach, F., Laborder, S. I., Lobinger, B. H., Mesagno, C. Achtzehn, S., & Arimond, F. (2015). Non automated pre-performance routine in tennis: An intervention study. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 27(2), 123-131. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2014.957364

Lidor, R. & Mayan, Z. (2005). Can beginning learners benefit, from pre-performance routines when serving in volleyball? The Sport Psychologist 19(4), 243–263. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.19.4.343

Mega, C., Ronconi, L., & De Beni, R. (2014). What makes a good student? How emotions, self-regulated learning, and motivation contribute to academic achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106(1), 121–131. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033546

Mesagno, C., Hill, D. M., & Larkin, P. (2015). Examining the accuracy and in game performance effects between pre- and post-performance routines: A mixed methods study. Psychology of Sort and Exercise, 19, 85–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.03.005

Peper, E., Wilson, V., Martin, M., Rosegard, E., & Harvey, R. (2021). Avoid Zoom fatigue, be present and learn. NeuroRegulation, 7(1).

Shoepe, T. C., McManus, J. F., August, S. E., Mattos, N. L., Vollucci, T. C. & Sparks, P. R. (2020). Instructor prompts and student engagement in synchronous online nutrition classes. American Journal of Distance Education, 34, 194–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2020.1726166

Suni, E. (2021). Sleep Hygiene. https://www.sleepfoundation.org/sleep-hygiene.

Wilson, V. E. & Peper, E. (2011). Athletes are different: factors that differentiate biofeedback/neurofeedback for sport versus clinical practice. Biofeedback, 39(1), 27–30. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-39.1.01

Beyond Zoom Fatigue: Re-energize Yourself and Improve Learning

Posted: November 24, 2020 Filed under: behavior, computer, digital devices, educationj, health, posture, stress management | Tags: boredom, learning, mind-body, zoom fatigue 7 CommentsErik Peper and Amber Yang

“Instead of zoning out and being on my phone half the time. I felt more engaged in the class and like I was actually learning something.” -21 year old college student

Before the pandemic, roughly, two-thirds of all social interactions were face-to-face—and when the shelter-in-place order hit our communities, we were all faced with the task of learning how to engage virtually. The majority of students reported that taking online classes instead of in person classes is significantly more challenging. It is easier to be distracted and multitask online—for example, looking at Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, texting, surfing the internet, responding to notifications, listening to music, or drifting to sleep. Hours of watching TV and/or streaming videos have conditioned many people to sit and take in information passively, which discourages them from actively responding or initiating. The information is rapidly forgotten when the next screen image or advertisement appears. Effectively engaging on Zoom requires a shift from passively watching and listening to being an active, creative participant.

Another barrier to virtual engagement is that communicating online does not engage all senses. A considerable amount of our communication is nonverbal—sounds, movement, visuals, physical structures, touch, and body language. Without these sensory cues, it can be difficult to feel socially connected on Zoom, Microsoft Teams, or Google Meet to sustain attention and to focus especially if there are many people in the class or meeting. Another challenge to virtual learning is that without the normal environment of a classroom, many students across the country are forced to learn in emotionally and/or physically challenging environments, which gets in the way of maintaining attention and focus. The Center for Disease Prevention (CDC) reported that anxiety disorder and depressive disorder have increased considerably in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic (Leeb et al, 2020; McGinty et al, 2020). Social isolation, stay-at-home orders, and coping with COVID-19 are contributing factors affecting mental health especially for minority and ethnic youth. Stress, anxiety and depression can greatly affect students’ ability to learn and focus.

The task of teaching has also become more stressful since many students are not visible or appear still-faced and non-responsive. Teaching to non-responsive faces is significantly more stressful since the presenter receives no social feedback. The absence of social feedback during communication is extremely stressful. It is the basis of Trier Social stress test in which a person presents for five minutes to a group of judges who provide no facial or verbal feedback (Allen et al, 2016; Peper, 2020).

The Zoom experience especially in a large class can be a no win situation for the presenter and the viewer. To help resolve this challenge, we explored a strategy to increase student engagement and reduce social stress of the teacher. In this exploration, we asked students to rate their subjective energy level, attention and involvement during a Zoom conducted class. For the next Zoom class, they were asked to respond frequently with facial and body expressions to the presentation. For example, students would expressively shake their head no or yes and/or use facial expressions to signal to the teacher that they were engaged and listening. Other strategies included giving thumbs up or thumbs down, making sounds, and changing your body posture as a response to the presentation. Watch the superb non-judgmental instructions adapted for high school students by Amber Yang.

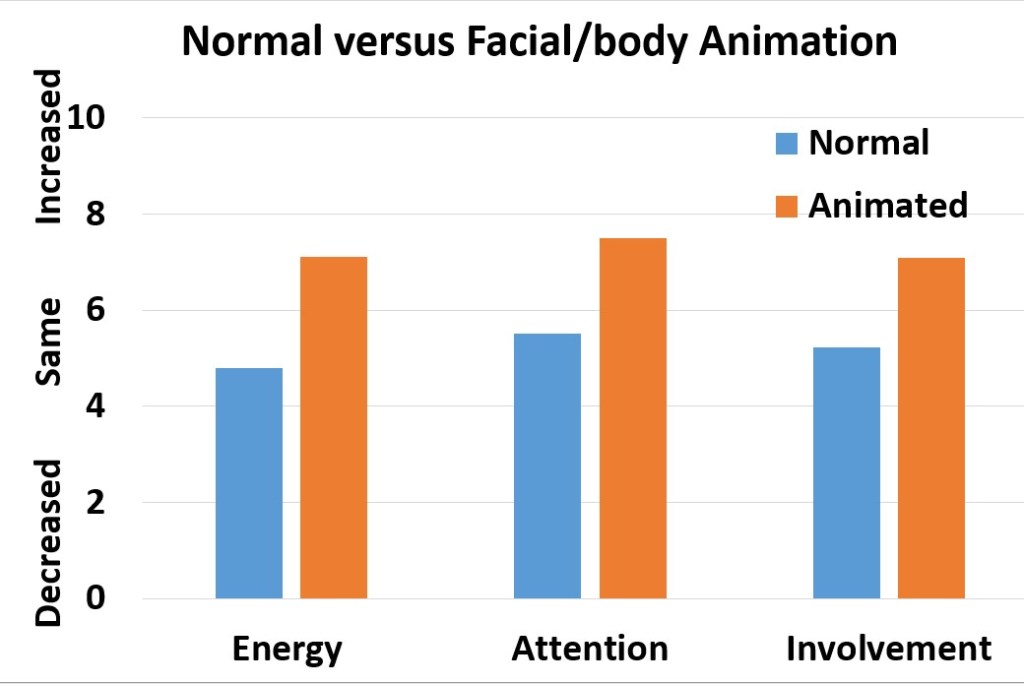

When college students purposely implement and increase their animated facial and body responses by 123% during Zoom classes, they report a significant increase in frequency of animation (ANOVA (F(1,70) = 30.66, p < .0001), energy level (ANOVA (F(1,70) = 28.96, p < .0001), attention (ANOVA (F(1,70) = 16.87, p = .0001) and involvement (ANOVA (F(1,69) = 10.70, p = .002) as compared just attending normally in class (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Change in subjective energy, attention and involvement when the students significantly increase their facial and body animation by 123 % as compared to their normal non-expressive class behavior (Peper & Yang, in press).

“I never realized how my expressions affected my attention. Class was much more fun” -22 year old college student

“I can see how paying attention and participation play a large role in learning material. After trying to give positive facial and body feedback I felt more focused and I was taking better notes and felt I was understanding the material a bit better.” –28 year old medical student

These quotes are a few of the representative reports by more than 80% of the students who observed that being animated and responsive helped them to stay present and learn much more easily and improve retention of the materials. For a few students, it was challenging to be animated as they felt shy, self-conscious and silly and kept wondering what other students would think of them.

Having students compare two different ways of being in Zoom class is a useful assignment since it allows students to discover that being animated and responsive with facial/body expression improves learning. So often we forget how our body impacts our thoughts and emotions. For example, when students were asked to sit in a slouched position, they reported that it was much easier to recall hopeless, helpless, powerless and defeated memories and more difficult to perform mental math in the slouched position. While in the upright position it was easier to access positive empowering memories and easier to perform mental math (Peper et al, 2017; Peper et al, 2018).

Experience how body posture affects emotional recall and feeling (adapted from Alda, 2018).

1) Stand up and configure your body in a position that signals defeat, hopelessness and depression (slouching with the head down). While holding this position, recall a memory of hopelessness and defeat. Notice any negative emotions that arise from this.

2) Shift and configure your body into a position that signals joy, happiness and success (standing tall, looking up with a smile). While holding this position, recall a memory of joy and happiness. Notice any positive emotions that arise from this.

3) Configure your body in a position that signals defeat, hopelessness and depression (slouching with the head down). While holding this position, recall a joy, happiness and success. Do not change your body position. End this configuration after holding it for a little while.

4) Shift and your body in a position that signals joy, happiness and success (standing tall, looking up with a smile). While holding this position, recall a memory of hopelessness and defeat. Do not change your body position. End this configuration after holding it for a little while.

When body posture and expression are congruent with the evoked emotion, it is almost always easier to experience the emotions. On the other hand, when the body posture expression is the opposite of the evoked emotion (e.g., the body in a positive empowered stance while recalling hopeless defeated memories) it is much more difficult to evoke and experience the emotion. This same concept applies to learning. When slouching and lying on the bed while in a Zoom class, it is much more difficult to stay present and not drift off. On the other hand, when sitting erect and upright and actively responding to the presentation, the body presence/posture invites the brain to focus for optimized learning.

Conclusion

In a Zoom environment, it is easy to slouch, drift away, and become non-responsive—which can exacerbate zoom fatigue symptoms and also decrease our capacity to learn, focus, and feel connected with the people around us. Take charge and actively participate in class by sitting up, maintaining an empowered posture, and using nonverbal facial and body expressions to communicate. The important concept is not how you show your animation, but that you actively participate within the constraints of your own limitations. For example, if a person is paralyzed the person will benefit if they do the experience internally even though their body may not show any expression. By engaging our soma we optimize our learning experience as we face the day-to-day challenges of the pandemic and beyond.

I noticed I was able to retain information better as well as enjoy the class more when I used facial-body responses. At times, where I would try to wonder off into bliss, I would catch myself and try to actively engage in the class with body movements even if there is no discussion. Animated face/body was a better learning experience. –21-year old college student.

References

Peper, E. (October 13, 2020). Breaking the social bond: The immobilized face. The Peper Perspective.

Peper, E., Wilson, V.E., Martin, M., Rosengard, E., & Harvey, R. (unpublished). Avoid Zoom fa