Implement your New Year’s resolution successfully[1]

Posted: December 29, 2024 Filed under: attention, behavior, CBT, cognitive behavior therapy, education, emotions, Exercise/movement, healing, health, self-healing | Tags: goal setting, health, lifestyle, motivation, performance, personal-development Leave a comment

Adapted from: Peper, E. Pragmatic suggestions to implement behavior change. Biofeedback.53(2), 41-45. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-53.02.05

Ready to crush your New Year’s resolutions and actually stick to them this time? Whether you’re determined to quit vaping or smoking, cut back on sugar and processed foods, reduce screen time, get moving, volunteer more, or land that dream job, sticking to your goals is the real challenge. We’ve all been there: kicking off the year with ambitious plans like, “I’ll work out every day,” or “I’m done with junk food for good.” But a few weeks in? The gym is a distant memory, the junk food stash is back, and those cigarettes are harder to let go of than expected.

So, how can you make this year different? Here are some tried-and-true tips to help you turn those resolutions into lasting habits:

Be clear of your goal and state exactly what you want to do (Pilcher et al., 2022; Latham & Locke, 2006).

Did you know your brain is super literal and doesn’t process “not” the way you think it does? For example, if you say, “I will not smoke,” your brain has to first imagine you smoking, then mentally cross it out. Guess what? By rehearsing the act of smoking in your mind, you’re actually increasing the chances that you’ll light up again.

Think of it like this: hand a four-year-old a cup of hot chocolate and ask them to walk it over to someone across the room. Halfway there, you call out, “Be careful, don’t spill it!” What usually happens? Yep, the hot chocolate spills. That’s because the brain focuses on “spill,” not the “don’t.” Now, imagine instead you say, “You’re doing great! Keep walking steadily.” Positive framing reinforces the action you want to see. The lesson is to reframe your goals in a way that focuses on what you want to achieve, not what you’re trying to avoid. Let’s look at some examples to get you started:

| Negative framing | Positive framing |

| I plan to stop smoking | I choose to become a nonsmoker |

| I will eat less sugar and ultra-processed foods | I will shop at the farmer’s market, buy more fresh vegetable and prepare my own food. |

| I will reduce my negative thinking (e.g., the glass is half empty). | I will describe events and thoughts positively (e.g., the class is half full). |

Describe what you want to do positively.

Be precise and concrete.

The more specific you can describe what you plan to do, the more likely will it occur as illustrated in the following examples.

| Imprecise | Concrete and specific |

| I will begin exercising. | I will buy the gym membership next week Monday and will go to the gym on Monday, Wednesday and Friday right after work at 5:30pm for 45 minutes. |

| I will reduce my angry outbursts, | Before I respond, I will take a slow breath, look up, relax my shoulders and remind myself that the other person is doing their best. |

| I want to limit watching streaming videos | At home, I will move the couch so that it does not face the large TV screen, and I have enrolled in a class to learn another language and I will spent 30 minutes in the evening practicing the new language. |

| I will stop smoking | When I feel the initial urge to smoke, I stand up, do a few stretches, and practice box breathing and remind myself that I am a nonsmoker. |

Describe in detail what you will do.

Identify the benefits of the old behavior that you want to change and how you can achieve the same benefits with your new behavior. (Peper et al, 2002)

When setting a New Year’s resolution, it’s easy to focus on the perks of the new behavior and the harms of the old behavior while overlooking the benefits your old habit provided. However, if you don’t plan ways to achieve the same benefits, the old behavior provided, it’s much harder to stick to your goal.

Before diving into your new resolution, take a moment to reflect. What did your old behavior do for you? What needs did it meet? Once you identify those, you can develop strategies to achieve the same benefits in healthier, more constructive ways.

For example, let’s say your goal is to stop smoking. Smoking might have helped you relax during stressful moments or provided a social activity with friends. To make the switch, you’ll need to find alternatives that deliver similar results, like practicing deep-breathing exercises to manage stress or inviting friends for a walk instead of a smoke break. By creating a plan to meet those needs, you’ll set yourself up for lasting success.

| Benefits of smoking | How to achieve the same benefits when being a none smoker |

| Stress reduction | I will learn relaxation and diaphragmatic breathing. The moment, I feel the urge to smoke, I sit up, look up, raise my shoulder and dropped them, and breathe slowly |

| Breaks during work | I will install a reminder on my cellphone to ping and each time it pings, I stop, stand up, walk around and stretch. |

| Meeting with friends | I will tell my friends, not to offer me a cigarette and I will spent time with friends who are non-smokers. |

| Rebelling against my parents who were opposed to smoking | I will explore how to be independent without smoking |

Describe your benefits and how you will achieve them.

Reduce the cues that evoke the old behavior and create new cues that will trigger the new behavior (Peper & Wilson, 2021).

A lot of our behavior is automatic—shaped by classical conditioning, just like Pavlov’s dog. Remember the famous experiment? Pavlov paired the sound of a bell with food, and after a while, the bell alone made the dog salivate (McLeod, 2024). We’re not so different.

Think about it: if you’ve gotten into the habit of smoking in your car, simply sitting in the driver’s seat can trigger the automatic urge to grab a cigarette. Or, if you tend to feel depressed when you’re home but better when you’re out with friends, your home environment might be acting as a cue for those feelings.

Interestingly, many people find it easier to change habits in a new environment. Why? Because there are no built-in triggers to reinforce the behavior they’re trying to change. This highlights how much of what we often call “addiction” might actually be conditioned behavior, reinforced by familiar cues in our surroundings. By recognizing the power of these triggers can help you disrupt old patterns. By creating a fresh environment or consciously changing your responses to cues, you can take control and start forming new, healthier habits.

This concept has been understood for centuries by some hunting and gathering societies. When something tragic happened—like the death of a family member in a hut—the community would often burn the hut to “eliminate the evil spirit.” Beyond the spiritual aspect, this practice served a practical purpose: it removed all the physical cues that reminded people of their loss, making it easier to focus on the present and move forward.

Of course, I’m not suggesting you destroy your home. But the underlying principle still holds true in modern times. In fact, many Northern European cultures incorporate a version of this idea through the ritual of Spring Cleaning. By decluttering, rearranging furniture, and refreshing the home, the old cues are removed and create a sense of renewal.

So often we forget that cues in our environment play a powerful role in triggering our behavior. By identifying the triggers that evoke old habits and finding ways to remove or change them, you can create a fresh environment that supports your goals. For example, if you’re trying to stop snacking on junk food late at night, consider rearranging your pantry so the tempting items are out of sight—or better yet, replace them with healthier options. Small changes like this can have a big impact on your ability to stay on track.

| Cues that triggered the behavior | How cues were changed |

| In the evening going to the kitchen and getting the chocolate from the cupboard. | Buying fruits and have them on the table and not buying chocolate. If I do buy chocolate store it on the top shelf away so that I do not see it or store it in the freezer. |

| Getting home and being depressed. | Clean the house, change the furniture around and put positive picture high up on the wall. |

| Smoking in the car. | Replace the car with another car that no one had smoked in and spray the care with pine scent. |

Identify the cues that trigger your behavior and how you changed them.

Identify the first sensation that triggered the behavior you would like to change.

Whether it’s smoking, drinking, scratching your skin, spiraling into negative thoughts, or eating too many pastries, once a behavior starts, it can feel nearly impossible to stop. That’s why the key is to catch yourself before the habit takes over., t’s much easier to interrupt a pattern at the very first sign—the initial trigger—rather than after you’ve fully dived into the behavior. Yet how often do we find ourselves saying, “Next time, I’ll do it differently”?

Here’s the strategy: identify the first trigger. This could be a physical sensation, an emotion, a thought, or an external cue. Once you’re aware of that first flicker of a trigger, redirect your thoughts and actions toward what you actually want, rather than letting the automatic behavior take control. For example:

I just came home at 10:15 PM and felt lonely and slightly depressed. I walked into the kitchen, opened the fridge, grabbed a beer, and drank it. Then, I reached for another bottle.

Observing this behavior, the first trigger was the loneliness and slight depression upon arriving home. Recognizing that feeling in the moment offers an opportunity to pause and make a conscious choice. Instead of heading to the fridge, you could redirect your actions—call a friend, go for a quick walk, or write down your thoughts in a journal. By catching that initial trigger, you can focus yourself toward healthier behaviors and break the cycle.

| First sensation | Changed response to the sensation |

| I observed that the first sensation was feeling tired and lonely. | When I entered the house, instead of going to the kitchen, I stretched, looked up and took a deep breath and then called a close friend of mine. We talked for ten minutes and then I went to bed. |

Identify your first sensation and how you changed your behavior.

Incorporate social support and social accountability (Drageset, 2021).

Doing something on your own often requires a lot of willpower, and sticking to it every time can feel like an uphill battle. Take this example:

My goal is to exercise every other morning. But last night, I stayed up late and felt tired in the morning, so I skipped my workout.

Sound familiar? Now imagine if I’d planned to meet a workout buddy. Knowing someone was counting on me would’ve gotten me out of bed, even if I was tired, because I wouldn’t want to let them down.

Accountability can make all the difference. Another powerful strategy is sharing your goals publicly. When you announce your plans on social media or to friends and family, you create a sense of commitment—not just to yourself but to others. It’s like having a built-in support system cheering you on and holding you accountable. Whether it’s finding a partner, joining a group, or sharing your progress online, involving others can help turn your resolutions into habits you’re more likely to stick with.

Describe a strategy to increase social support and accountability.

Be honest in identifying what motivates you.

Exercising, eating healthy foods, thinking positively, or being on time are laudable goals; however, it often feels like work doing the “right” thing. To increase success, analyze what really helped you be successful. For example:

Many years ago, I decided that I should exercise more. Thus, I drove from house to the track and ran eight laps. I did this for the next three weeks and then stopped exercising. Eventually, I pushed myself again to exercise and after a while stopped again. The same pattern kept repeating. I would exercise and fall off the wagon and stop. Later that fall, I met a woman who was a jogger and we became friends and for the next year we jogged together and even did races. During this time, I did not experience any effort to go jogging. After a year, she broke up with me and once again, I had to use willpower to go jogging and my old pattern emerged and after a few days I stopped jogging even though I felt much better after having jogged.

I finally, asked what is going on? I realized that the joy of the jogging was running with a friend. Once, I recognized this, instead using will power to go running, I spent my willpower finding people with whom I could exercise. With these new friends, running did not depend upon my willpower– It only depended on making running dates with my new friends.

Explore factors that will allow you to do your activity without having to use willpower.

Conclusion

These seven strategies are just a starting point—there are countless other techniques that can help you stick to your New Year’s resolutions. For example, keeping a log, setting reminders, or rewarding yourself for progress are all powerful ways to stay on track. The real magic happens when your new behavior becomes part of your routine—embedded in your habitual patterns. The more automatic it feels, the greater your chances of long-term success.

So, take joy in identifying, implementing, and maintaining your resolutions. Let them enhance your well-being and become second nature. Share your successful strategies with me and others—it could be just the inspiration someone else needs to achieve their goals, too.

References

Drageset, J. (2021). Social Support. In: Haugan G, Eriksson M, editors. Health Promotion in Health Care – Vital Theories and Research [Internet]. Cham (CH): Springer, Chapter 11. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK585650/ https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-63135-2_11

Latham, G. P., & Locke, E. A. (2006). Enhancing the Benefits and Overcoming the Pitfalls of Goal Setting. Organizational Dynamics, 35(4), 332–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2006.08.008

McLeod, S. (2024). Classical Conditioning: How It Works With Examples.Simple Psychology. Accessed December 29, 2024. https://www.simplypsychology.org/classical-conditioning.html

Peper, E., Gibney, H. K. & Holt, C. (2002). Make Health Happen. Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall-Hunt. (Pp 185-192). https://he.kendallhunt.com/make-health-happen

Peper, E. & Wilson, V. (2021). Optimize the learning state: techniques and habits. Biofeedback, 9(2), 46-49. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-49-2-04

Pilcher, S., Schweickle, M. J., Lawrence, A., Goddard, S. G., Williamson, O., Vella, S. A., & Swann, C. (2022). The effects of open, do-your-best, and specific goals on commitment and cognitive performance. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 11(3), 382–395. https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000301

For detailed suggestions, see the following blogs:

[1] Edited with the help of ChatGPT.

Be careful what you think*

Posted: July 23, 2018 Filed under: behavior, Exercise/movement, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: CBT, cognitive therapy, Mind body connection, muscle testing, performance, psyching out, somatic practices Leave a comment“I couldn’t belief it. I thought that I was strong and yet, I could not resist the downward pressure when I recalled a hopeless and helpless memory. Yet a minute later, I could easily resist the downward pressure on my arm when I thought of a positive and empower memory. I now understand how thoughts affect me.”

Thoughts/emotions affect body and body affects thoughts and emotions is the basis of the psychophysiological principle formulated by the biofeedback pioneers Elmer and Alice Green. The language we use, the thoughts we contemplate, the worries and ruminations that preoccupy us may impact our health.

Changing thoughts is the basis of cognitive behavior therapy and practitioners often teach clients to become aware of their negative thoughts and transform the internal language from hopeless, helpless, or powerless to empowered and positive. Think and visualize what you want and not what you do not want. For example, state, “I have studied and I will perform as best as I can” or “I choose to be a non-smoker instead of stating, “I hope I do not fail the exam” or “I want to stop smoking.” The more you imagine what you what in graphic detail, the more likely will it occur.

Most people rationally accept that thoughts may affect their body; however, it is abstract and not a felt experience. Also, some people have less awareness of the mind-body connection unless it causes discomfort. Our attention tends to be captured by visual and auditory stimuli that constantly bombard us so that we are d less aware of the subtle somatic changes.

This guided practice explores what happens when you recall helpless, hopeless, powerless or defeated memories as compared to recalling empowering positive memories. It allows a person to experience–instead of believing—how thoughts impact the body. 98% of participants felt significantly weaker after recalling the helpless, hopeless, powerless or defeated memories. Once the participants have experienced the effect, they realize how thoughts effect their body.

The loss of strength is metaphor of what may happen to our immune system and health. Do you want to be stronger or weaker? The challenge in transforming thoughts is that they occur automatically and we often doubt that we can change them. The key is to become aware of the onset of the thought and transform the thought. Thoughts are habit patterns and the more you practice a habit, the more it becomes automatic. Enjoy the experiential exercise, Mind-body/Bodymind-connection: Muscle testing.

*I thank Paul Godina, Jung Lee and Lena Stampfli for participating in the videos.

The practice was adapted from, Gorter, R. & Peper, E. (2011). Fighting Cancer-A Non Toxic Approach to Treatment. Berkeley: North Atlantic.

Timing affects health and productivity

Posted: March 10, 2018 Filed under: behavior, education, emotions, Evolutionary perspective, Uncategorized | Tags: behavioral economics, chronobiology, emotions, mood, performance, productivity Leave a commentHave you experienced that your attentions is more focused in the morning than late afternoon?

Have you wondered what is the best time in the day to have a job interview?

Is it better to have an operation in the morning or in the afternoon?

These and many other questions are explored in the superb book by Daniel Pink, When-The scientific secrets of perfect timing. This book reviews the literature of chronobiology, psychology, and behavior economics and describes the effect of time of day on human behavior. For example, students do significantly better if they take math tests in the morning than late afternoon or parolees have a much higher chance of being paroled early morning or right after the judge has taken a break than before lunch or late afternoon. Read Pink’s book or watch his JCCSF presentation and use the information to change your own timing patterns to optimize your health and performance.

Do you blank out on exams? Improve school performance with breathing* **

Posted: September 18, 2016 Filed under: Breathing/respiration, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: anxiety, fear, gasping, math, memory, performance, respiration 3 Comments “I opened the exam booklet and I went blank.”

“I opened the exam booklet and I went blank.”

“When I got anxious, I took a slow breath, reminded myself that I would remember the material. I successfully passed the exam.”

“I was shocked, when I gasped, I could not remember my girlfriend’s name and then I could not remember my mother’s name. When breathed slowly, I had no problem and easily remembered both”

Blanking out the memorized information that you have studied on an exam is a common experiences of students even if they worked hard (Arnsten, Mazure, & Sinha, 2012). Fear and poor study habits often contribute to forgetting the material (Fitkov-Norris, & Yeghiazarian, 2013). Most students study while listening to music, responding to text message, or monitoring social network sites such as, Facebook, twitter, Instagram, or Pinterest (David et al., 2015).. Other students study the material for one class then immediately shift and study material from another class. While at home they study while sitting or lying on their bed. Numerous students have internalized the cultural or familial beliefs that math is difficult and you do not have the aptitude for the material—your mother and father were also poor in math (Cherif, Movahedzadeh, Adams, & Dunning, 2013). These beliefs and dysfunctional study habits limit learning (Neal, Wood, & Drolet, 2013).

Blanking out on an exam or class presentation is usually caused by fear or performance anxiety which triggers a stress response (Hodges, 2015; Spielberger, Anton, & Bedell, 2015). At that moment, the brain is flooded with thoughts such as, I can’t do it,” “I will fail,” “I used to know this, but…”, or “What will people think?” The body responds with a defense reaction as if you are being threatened and your survival is at stake. The emotional reactivity and anxiety overwhelms cognition, resulting in an automatic ‘freeze’ response of breath holding or very shallow breathing. At that moment, you blank out (Hagenaars, Oitzl, & Roelofs, 2014; Sink et al., 2013; Von Der Embse, Barterian, & Segool, 2013).

Experience how your thinking is affected by your breathing pattern. Do the following practice with another person.

Have the person ask you a question and the moment you hear the beginning of the question, gasp as if you are shocked or surprised. React just as quickly and automatically as you would if you see a car speeding towards you. At that moment of shock or surprise, you do not think, you don’t spend time identifying the car or look at who is driving. You reflexively and automatically jump out of the way. Similarly in this exercise, when you are asked to answer a question, act as if you are as shocked or surprised to see a car racing towards you.

Practice gasping at the onset of hearing the beginning of a question such as, “What day was it yesterday?” At the onset of the sound, gasp as if startled or afraid. During the first few practices, many people wait until they have heard the whole phrase before gasping. This would be similar to seeing a car racing towards you and first thinking about the car, at that point you would be hit. Repeat this a few times till it is automatic.

Now change the breathing pattern from gasping to slow breathing and practice this for a few times.

When you hear the beginning of the question breathe slowly and then exhale.” Inhale slowly for about 4 seconds while allowing your abdomen to expand and then exhale softly for about 5 or six seconds. Repeat practicing slow breathing in response to hearing the onset of the question until it is automatic.

Now repeat the two breathing patterns (gasping and slow breathing) while the person asks you a subtraction or math questions such as, “Subtract 7 from 93.”

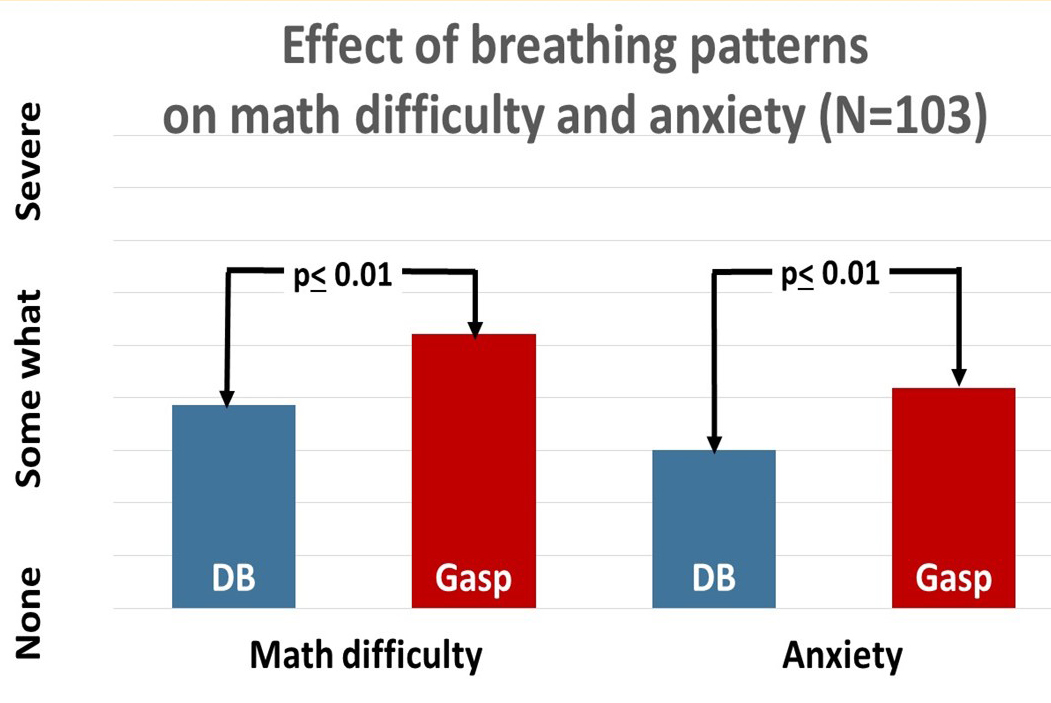

In research with more than 100 college students, we found that students had significantly more self-reported anxiety and difficulty in solving math problems when gasping as compared to slow breathing as shown Figure 1 (Lee et al, 2016; Peper, Lee, Harvey & Lin, 2016).

Fig 1. The effect of breathing style on math performance. Diaphragmatic breathing significantly increased math performance and decreased anxiety (from: Peper, Lee, Harvey & Lin, 2016).

As one 20 year old college student said, “When I gasped, my mind went blank and I could not do the subtraction. When I breathed slowly, I had no problem doing the subtractions. I never realized that breathing had such a big effect upon my performance.”

When you are stressed and blank out, take a slow diaphragmatic breath to improve performance; however, it is only effective if you have previously studied the materials effectively. To improve effective learning incorporate the following concepts when studying.

- Approached learning with a question. When you begin to study the material or attend a class, ask yourself a question that you would like to be answered. When you have a purpose, it is easier to stay emotionally present and remember the material (Osman, & Hannafin, 1994).

- Process what you are learning with as many sensory cues as possible. Take hand written notes when reading the text or listening to your teacher. Afterwards meet with your friends in person, on Skype and again discuss and review the materials. As you discuss the materials, add comments to your notes. Do not take notes on your computer because people can often type almost as quickly as someone speaks. The computer notes are much less processed and are similar to the experience of a court or medical transcriptionist where the information flows from the ears to the fingers without staying in between. College students who take notes in class on a computer or tablets perform worse on exams than students who write notes. When you write your notes you have to process the material and extract and synthesis relevant concepts.

- Review the notes and material before going to sleep. Research has demonstrated that whatever material is in temporary memory before going to sleep will be more likely be stored in long term memory (Gais et al., 2006; Diekelmann et al., 2009). When you study material is stored in temporary memory, and then when you study something else, the first material tends to displaced by the more recent material. The last studied material is more likely stored in long term memory. When you watch a movie after studying, the movie content is preferentially stored in permanent memory during sleep. In addition, what is emotionally most important to you is usually stored first. Thus, instead of watching movies and chatting on social media, discuss and review the materials just before you go to sleep.

- Learning is state dependent. Study and review the materials under similar conditions as you will be tested. Without awareness the learned content is covertly associated with environmental, emotional, social and kinesthetic cues. Thus when you study in bed, the material is most easily accessed while lying down. When you study with music, the music become retrieval trigger. Without awareness the materials are encoded with the cues of lying down or the music played in the background. When you come to the exam room, none of those cues are there, thus it is more difficult to recall the material (Eich, 2014).

- Avoid interruptions. When studying each time you become distracted by answering a text message or responding to social media, your concentration is disrupted (Swingle, 2016). Imagine that learning is like scuba diving and the learning occurs mainly at the bottom. Each interruption forces you to go to the surface and it takes time to dive down again. Thus you learn much less than if you stayed at the bottom for the whole time period.

- Develop study rituals. Incorporate a ritual before beginning studying and repeat it during studying such as three slow breaths. The ritual can become the structure cue associated with the learned material. When you come to exam and you do not remember or are anxious, perform the same ritual which will allow easier access to the memory.

- Change your internal language. What we overtly or covertly say and believe is what we become. When you say, “I am stupid”, “I can’t do math,” or “It is too difficult to learn,” you become powerless which increases your stress and inhibits cognitive function. Instead, change your internal language so that it implies that you can master the materials such as, “I need more time to study and to practice the material,” “Learning just takes time and at this moment it may take a bit longer than for someone else,” or “I need a better tutor,”

When you take charge of your study habits and practice slower breathing during studying and test taking, you may experience a significant improvement in learning, remembering, accessing, and processing information.

References

Arnsten, A., Mazure, C. M., & Sinha, R. (2012). This is your brain in meltdown. Scientific American, 306(4), 48-53.

Cherif, A. H., Movahedzadeh, F., Adams, G. E., & Dunning, J. (2013). Why Do Students Fail?. Higher Learning, 227, 228.

David, P., Kim, J. H., Brickman, J. S., Ran, W., & Curtis, C. M. (2015). Mobile phone distraction while studying. new media & society, 17(10), 1661-1679.

Diekelmann, S., Wilhelm, I., & Born, J. (2009). The whats and whens of sleep-dependent memory consolidation. Sleep medicine reviews, 13(5), 309-321.

Eich, J. E. (2014). State-dependent retrieval of information in human episodic memory. Alcohol and Human Memory (PLE: Memory), 2, 141.

Fitkov-Norris, E. D., & Yeghiazarian, A. (2013). Measuring study habits in higher education: the way forward?. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series (Vol. 459, No. 1, p. 012022). IOP Publishing.

Gais, S., Lucas, B., & Born, J. (2006). Sleep after learning aids memory recall. Learning & Memory, 13(3), 259-262.

Hagenaars, M. A., Oitzl, M., & Roelofs, K. (2014). Updating freeze: aligning animal and human research. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 47, 165-176.

Hodges, W. F. (2015). The psychophysiology of anxiety. Emotions and Anxiety (PLE: Emotion): New Concepts, Methods, and Applications, 12, 175.

Lee, S., Sanchez, J., Peper, E., & Harvey, R. (2016). Effect of Breathing Style on Math Problem Solving. Presented at the 47th Annual Meeting of the Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, Seattle WA, March 9-12, 2016

Neal, D. T., Wood, W., & Drolet, A. (2013). How do people adhere to goals when willpower is low? The profits (and pitfalls) of strong habits. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(6), 959.

Osman, M. E., & Hannafin, M. J. (1994). Effects of advance questioning and prior knowledge on science learning. The Journal of Educational Research,88(1), 5-13.

Peper, E., Lee, S., Harvey, R., & Lin, I-M. (2016). Breathing and math performance: Implication for performance and neurotherapy. NeuroRegulation, 3(4),142–149.

Spielberger, C. D., Anton, W. D., & Bedell, J. (2015). The nature and treatment of test anxiety. Emotions and anxiety: New concepts, methods, and applications, 317-344.

Sink, K. S., Walker, D. L., Freeman, S. M., Flandreau, E. I., Ressler, K. J., & Davis, M. (2013). Effects of continuously enhanced corticotropin releasing factor expression within the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis on conditioned and unconditioned anxiety. Molecular psychiatry, 18(3), 308-319.

Swingle, M. (2016). i-Minds: How cell phones, computers, gaming and social media are changing our brains, our behavior, and the evolution of our species. Gabriola Island, BC, Canada: New Society Publishers.

Von Der Embse, N., Barterian, J., & Segool, N. (2013). Test anxiety interventions for children and adolescents: A systematic review of treatment studies from 2000–2010. Psychology in the Schools, 50(1), 57-71.

*I thank Richard Harvey, PhD. for his constructive feedback and comments and Shannon Lee for her superb research.

** This blog was adapted from: Lee, S., Sanchez, J., Peper, E., & Harvey, R. (2016). Effect of Breathing Style on Math Problem Solving. Presented at the 47th Annual Meeting of the Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, Seattle WA, March 9-12, 2016

Muscle biofeedback makes the invisible visible

Posted: January 6, 2012 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: back pain, biofeedback, electromyography, muscle tension, neck pain, performance, shoulder pain 3 Comments“I feel much more relaxed and realize now how unaware I was of the unnecessary tension I’ve been holding” is a common response after muscle biofeedback training. Many people experience exhaustion, stiffness, tightness, neck, shoulder and back pain while working long hours at the computer or while exercising. As we get older, we assume that discomforts are the result of aging. You just have to accept it and live with it–grin and bear it–or you need to be more careful while doing your job or performing your hobby. The discomfort in many cases is the result of misuse of your body. Observes what happens when you perform the following experiential practice Threading the needle.

Perform this task so that an observer would think it was real and would not know that you are only simulating threading a needle.

Imagine that you are threading a needle — really imagine it by picturing it in your mind and acting it out. Hold the needle between your left thumb and index finger. Hold the thread between the thumb and index finger of your right hand. Bring the tip of the thread to your mouth and put it between your lips to moisten it and make it into a sharp point. Then attempt to thread the needle, which has a very small eye. The thread is almost as thick as the eye of the needle.

As you are concentrating on threading this imaginary needle, observed what happened? While acting out the imagery, did you raise or tighten your shoulders, stiffen your trunk, clench your teeth, hold your breath or stare at the thread and needle without blinking?

Most people are surprised that they have tightened their shoulders and braced their trunk while threading the needle. Awareness only occurred after their attention was directed to the covert muscle bracing patterns.

In many cases muscles are tense even though the person senses and feels that they are relaxed. This lack of awareness can be resolved with muscle biofeedback–it makes invisible visible. Muscle biofeedback (electromyographic feedback) is used to monitor the muscle activity, teach the person awareness of the previously unperceived muscle tension and learn relax and control it. For more information of the use of muscle biofeedback to improve health and performance at work or in the gym, see the published chapter, I thought I was relaxed: The use of SEMG biofeedback for training awareness and control, by Richard Harvey and Erik Peper. It was published in W. A. Edmonds, & G. Tenenbaum (Eds.). (2012), Case studies in applied psychophysiology: Neurofeedback and biofeedback treatments for advances in human performance. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 144-159.