Be a tree and share gratitude

Posted: December 11, 2016 Filed under: Breathing/respiration, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: gratitude, Holistic health, Imagery, relaxation, self-healing, stress management 1 Comment

It was late in the afternoon and I was tired. A knock on my office door. One of my students came in and started to read to me from a card. “I want to thank you for all your help in my self-healing project…I didn’t know the improvements were possible for me in a span of 5 weeks…. I thank you so much for encouraging and supporting me…. I have taken back control of myself and continue to make new discoveries about my identity and find my own happiness and fulfillment… Thank you so much.”

I was deeply touched and my eyes started to fill with tears. At that moment, I felt so appreciated. We hugged. My tiredness disappeared and I felt at peace.

In a world where we are constantly bombarded by negative, fearful stories and images, we forget that our response to these stories impacts our health. When people watch fear eliciting videos, their heart rate increases and their whole body responds with a defense reaction as if they are personally being threatened (Kreibig, Wilhelm, Roth, & Gross, 2007). Afterwards, we may continue to interpret and react to new stimuli as if they are the same as what happened in the video. For example, while watching a horror movie, we may hold our breath, perspire and feel our heart racing; however, when we leave the theatre and walk down the street by ourselves, we continue to be afraid and react to stimuli as if what happened in video will now happen to us.

When we feel threatened, our body responds to defend itself. It reduces the blood flow to the gastrointestinal tract where digestion is taking place and sends it to large muscles so that we can run and fight. When threatened, most of our resources shifted to the processes that promote survival while withdrawing it from processes that do not lead to immediate survival such as digestion or regeneration (Sapolsky, 2004). From an evolutionary perspective, why spent resources to heal yourself, enhance your immune system or digest your food when you will become someone else’s lunch!

The more we feel threatened, the more we will interpret the events around us negatively. We become more stressed, defensive, and pessimistic. If this response occurs frequently, it contributes to increased morbidity and mortality. We may not be in control of external or personal event; however, we may be able to learn how to change our reactions to these events. It is our reactions and interpretations of the event that contributes to our ongoing stress responses. The stressor can be labeled as crisis or opportunity.

Mobilize your own healing when you take charge. When 92 students as part of a class at San Francisco State University practiced self-healing skill, most reported significant improvements in their health as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Average self-reported improvement after practicing self-healing skills for at least four weeks. (Reproduced with permission from Tseng, Abili, Peper, & Harvey, 2016).

A strategy that many students used was to interrupt their cascading automatic negative reactions. The moment they became aware of their negative thought and body slumping, they interrupted the process and practiced a very short relaxation or meditation technique.

Implement what the students have done by taking charge of your stress responses and depressive thoughts by 1) beginning the day with a relaxation technique, Relax Body-Mind, 2) interrupting the automatic response to stressors with a rapid stress reduction technique, Breathe and be a Tree, and 3) increasing vitality by the practice, Share Gratitude (Gorter & Peper, 2011).

Relax Body-Mind to start the day*

- Lie down or sit and close your eyes. During the practice if your attention wanders, just bring it back to that part of the body you are asked to tighten or let go.

- Wrinkle your face for ten seconds while continuing to breathe. Let go and relax for ten seconds.

- Bring your hands to your face with the fingers touching the forehead while continuing to breathe. While exhaling, pull your fingers down your face so that you feel your jaw being pulled down and relaxing. Drop your hands to your lap. Feel the sensations in your face and your fingers for ten seconds.

- Make a fist with your hands and lift them slightly up from your lap while continuing to breathe. Feel the sensations of tension in your hands, arms and shoulders for ten seconds. Let go and relax by allowing the arms to drop to your lap and relax. Feel the sensations change in your hands, arms and shoulders for ten seconds.

- Tighten your buttocks and flex your ankles so that the toes are reaching upwards to your knees. Hold for ten seconds while continuing to breathe. Let go and relax for ten seconds.

- Take a big breath while slightly arching your back away from the bed ore chair and expand your stomach while keeping your arms, neck, buttocks and legs relaxed. Hold the breath for twenty seconds. Exhale and let your back relax while allowing the breathing to continue evenly while sensing your body’s contact with the bed or chair for twenty seconds. Repeat three times.

- Gently shake your arms and legs for ten seconds while continuing to breathe. Let go and relax. Feel the tingling sensations in your arms and legs for 20 seconds.

- Evoke a past positive memory where you felt at peace and nurtured.

- Stretch and get up. Know you have done the first self-healing step of the day.

*Be gentle to yourself and stop the tightening or breath holding if it feels uncomfortable.

Breathe and be a Tree to dissipate stress and focus on growth

- Look at a tall tree and realize that you are like a tree that is rooted in the ground and reaching upward to the light. It continues to grow even though it has been buffeted by storms.

- When you become aware of being stressed, exhale slowly and inhale so that your stomach expands, the while slowly exhaling, look upward to the top of a real or imagined tree, admire the upper branches and leaves that are reaching towards the light and smile.

- Remember that even though you started to respond to a stressor, the stressor will pass just like storms battering the tree. By breathing and looking upward, accept what happened and know you are growing just like the tree.

Share Gratitude to increase vitality and health (adapted from Professor Martin Seligman’s 2004 TED presentation, The new era of positive psychology).

- Think of someone who did something for you that impacted your life in a positive direction and whom you never properly thanked. This could be a neighbor, teacher, friend, parent, or other family members.

- Write a 300-word testimonial describing specifically what the person did and how it positively impacted you and changed the course of your life.

- Arrange an actual face-to-face meeting with the person. Tell them you would like to see him/her. If they are far away, arrange a Skype call where you can actually see and hear him/her. Do not do it by email or texting.

- Meet with the person and read the testimonial to her/him.

- It may seem awkward to read the testimonial, after you have done it, you will feel closer and more deeply connected to the person. Moreover, the person to whom you read the testimonial, will usually feel deeply touched. Both your hearts will open.

References:

Gorter, R. & Peper, E. (2011). Fighting cancer: A nontoxic approach to treatment. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books, 205-207.

Kreibig, S. D., Wilhelm, F. H., Roth, W. T., & Gross, J. J. (2007). Cardiovascular, electrodermal, and respiratory response patterns to fear‐and sadness‐inducing films. Psychophysiology, 44(5), 787-806.Kreibig, Sylvia D., Frank H. Wilhelm, Walton T. Roth, and James J. Gross. “Cardiovascular, electrodermal, and respiratory response patterns to fear‐and sadness‐inducing films.” Psychophysiology 44, no. 5 (2007): 787-806.

Sapolsky, R. (2004). Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers. New York: Owl Books

Seligman, M. (2014). The new era of positive psychology. Ted Talk. Retrieved, December 10, 2016. https://www.ted.com/talks/martin_seligman_on_the_state_of_psychology

Tseng, C., Abili, R., Peper, E., & Harvey, R. (2016). Reducing Acne-Stress and an integrated self-healing approach. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback, 4(4), 445.)

Education versus treatment for self-healing: Eliminating a headache[1]

Posted: November 18, 2016 Filed under: Pain/discomfort, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: autogenic training, biofeedback, education, electromyography, headache, Holistic health, migraine, posture, treatment 3 Comments“I have had headaches for six years, at first occurring almost every day. When I got put on an antidepressant, they slowed to about 3 times a week (sometimes more) and continued this way until I learned relaxation techniques. I am 20 years old and now headache free. Everyone should have this educational opportunity to heal themselves.” -Melinda, a 20 year old student

Health and wellness is a basic right for all people. When students learn stress management skills which include awareness of stress, progressive muscle relaxation, Autogenic phrases, slower breathing, posture change, transforming internal language, self-healing imagery, the role of diet, exercise embedded within an evolutionary perspective as part of a college class their health often improves. When students systematically applied these self-awareness techniques to address a self-selected illness or health behavior (e.g., eczema, diet, exercise, insomnia, or migraine headaches), 80% reported significant improvement in their health during that semester (Peper et al., 2014b; Tseng, et al., 2016). The semester long program is based upon the practices described in the book, Make Health Happen, (Peper, Gibney, & Holt, 2002).

The benefits often last beyond the semester. Numerous students reported remarkable outcomes at follow-up many months after the class had ended because they had mastered the self-regulation skills and continued to implement these skills into their daily lives. The educational model utilized in holistic health courses is often different from the clinical/treatment model.

Educational approach: I am a student and I have an illness (most of me is healthy and only part of me is sick).

Clinical treatment approach: I am a patient and I am sick (all of me is sick)

Some of the concepts underlying the differences between the educational and the clinical approach are shown in Table 1.

| Educational approach | Clinic/treatment approach |

| Focuses on growth and learning | Focuses on remediation |

| Focuses on what is right | Focuses on what is wrong |

| Focuses on what people can do for themselves | Focuses on how the therapist can help patients |

| Assumes students as being competent | Implies patients are damaged and incompetent |

| Students defined as being competent to master the skills | Patients defined as requiring others to help them |

| Encourages active participation in the healing process | Assumes passive participation in the healing process |

| Students keep logs and write integrative and reflective papers, which encourage insight and awareness | Patients usually do not keep logs nor are asked to reflect at the end of treatment to see which factors contributed to success |

| Students meet in small groups, develop social support and perspective | Patients meet only with practitioners and stay isolated |

| Students experience an increased sense of mastery and empowerment | Patients experience no change or possibly a decrease in sense of mastery |

| Students develop skills and become equal or better than the instructor | Patients are healed, but therapist is always seen as more competent than patient |

| Students can become colleagues and friends with their teachers | Patients cannot become friends of the therapist and thus are always distanced |

Table 1. Comparison of an educational versus clinical/treatment approach

The educational approach focuses on mastering skills and empowerment. As part of the course work, students become more mindful of their health behavior patterns and gradually better able to transform their previously covert harm promoting patterns. This educational approach is illustrated in a case report which describes how a student reduced her chronic migraines.

Case Example: Elimination of Chronic Migraines

Melinda, a 20-year-old female student, experienced four to five chronic migraines per week since age 14. A neurologist had prescribed several medications including Imitrex (used to treat migraines) and Topamax (used to prevent seizures as well as migraine headaches), although they were ineffective in treating her migraines. Nortriptyline (a tricyclic antidepressant) and Excedrin Migraine (which contains caffeine, aspirin, and acetaminophen) reduced the frequency of symptoms to three times per week.

She was enrolled in a university biofeedback class that focused on learning self-regulation and biofeedback skills. All these students were taught the fundamentals of biofeedback and practiced Autogenic Training (AT) every day during the semester (Luthe, 1979; Luthe & Schultz, 1969; Peper & Williams, 1980).

In the class, students practiced with surface electromyography (SEMG) feedback to identify the presence of shoulder muscle overexertion (dysponesis), as well as awareness of minimum muscle tension. Additional practices included hand warming, awareness of thoracic and diaphragmatic breathing, and other biofeedback or somatic awareness approaches. In parallel with awareness of physical sensations, students practiced behavioral awareness such as alternating between a slouching body posture (associated with feeling self-critical and powerless) and an upright body posture (associated with feeling powerful and in control). Psychological awareness was focused on transforming negative thoughts and self-judgments to positive empowering thoughts (Harvey and Peper, 2011; Peper et al., 2014a; Peper et al, 2015). Taken together, students systematically increased awareness of physical, behavioral, and psychological aspects of their reactions to stress.

The major determinant for success is to generalize training at school, home and at work. Each time Melinda felt her shoulders tightening, she learned to relax and release the tension in her shoulders, practiced Autogenic Training with the phrase “my neck and shoulders are heavy.” In addition, whenever she felt her body beginning to slouch or noticed a negative self-critical thought arising in her mind, she shifted her body to an upright empowered posture, and substituted positive thoughts to reduce her cortisol level and increase access to positive thoughts (Carney & Cuddy, 2010; Cuddy, 2012; Tsai, et al., 2016). Postural feedback was also informally given by Melinda’s instructor. Every time the instructor noticed her slouching in class or the hallway, he visually changed his own posture to remind her to be erect.

Results

Melinda’s headaches reduced from between three and five per week before enrolling in the class to zero following the course, as shown in Figure 2. She has learned to shift her posture from slouching to upright and relaxed. In addition, she reported feeling empowered, mentally clear, and her acne cleared up. All medications were eliminated. At a two year follow-up, she reported that since she took the class, she had only few headaches which were triggered by excessive stress.

Figure 2. Frequency of migraine and the implementation of self-practices.

The major factors that contributed to success were:

- Becoming aware of muscle tension through the SEMG feedback. Melinda realized that she had tension when she thought she was relaxed.

- Keeping detailed logs and developing a third person perspective by analyzing her own data and writing a report. A process that encouraged acceptance of self, thereby becoming less judgmental.

- Acquiring a new belief that she could learn to overcome her headaches, facilitated by class lecture and verbal feedback from the instructor.

- Taking active control by becoming aware of the initial negative thoughts or sensations and interrupting the escalating chain of negative thoughts and sensations by shifting the attention to positive empowering thoughts and sensations–a process that integrated mindfulness, acceptance and action. Thus, transforming judgmental thoughts into accepting and positive thoughts.

- Becoming more aware throughout the day, at school and at home, of initial triggers related to body collapse and muscle tension, then changing her body posture and relaxing her shoulders. This awareness was initially developed because the instructor continuously gave feedback whenever she started to slouch in class or when he saw her slouching in the hallways.

- Practicing many, many times during the day. Namely, increasing her ongoing mindfulness of posture, neck, and shoulder tension, and of negative internal dialogue without judgment.

The benefits of this educational approach is captured by Melinda’s summary, “The combined Autogenic biofeedback awareness and skill with the changes in posture helped me remarkably. It improved my self-esteem, empowerment, reduced my stress, and even improved the quality of my skin. It proves the concept that health is a whole system between mind, body, and spirit. When I listen carefully and act on it, my overall well-being is exceptionally improved.”

References:

Carney, D. R., Cuddy, A. J., & Yap, A. J. (2010). Power posing brief nonverbal displays affect neuroendocrine levels and risk tolerance. Psychological Science, 21(10), 1363-1368.

Cuddy, A. (2012). Your body language shapes who you are. Technology, Entertainment, and Design (TED) Talk, available at: http://www.ted.com/talks/amy_cuddy_your_body_language_shapes_who_you_are

Harvey, E. & Peper, E. (2011). I thought I was relaxed: The use of SEMG biofeedback for training awareness and control (pp. 144-159). In W. A. Edmonds, & G. Tenenbaum (Eds.), Case studies in applied psychophysiology: Neurofeedback and biofeedback treatments for advances in human performance. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Luthe, W. (1979). About the methods of autogenic therapy (pp. 167-186). In E. Peper, S. Ancoli, & M. Quinn, Mind/body integration. New York: Springer.

Luthe, W., & Schultz, J.H. (1969). Autogenic therapy (Vols. 1-6). New York, NY: Grune and Stratton.

Peper, E., Booiman, A., Lin, I-M., & Shaffer, F. (2014a). Making the unaware aware-Surface electromyography to unmask tension and teach awareness. Biofeedback. 42(1), 16-23.

Peper, E., Gibney, K.H. & Holt. C. (2002). Make health happen: Training yourself to create wellness. Dubuque, IA: Kendall-Hunt. ISBN-13: 978-0787293314

Peper, E., Lin, I-M, Harvey, R., Gilbert, M., Gubbala, P., Ratkovich, A., & Fletcher, F. (2014b). Transforming chained behaviors: Case studies of overcoming smoking, eczema and hair pulling (trichotillomania). Biofeedback, 42(4), 154-160.

Peper, E., Nemoto, S., Lin, I-M., & Harvey, R. (2015). Seeing is believing: Biofeedback a tool to enhance motivation for cognitive therapy. Biofeedback, 43(4), 168-172. doi: 10.5298/1081-5937-43.4.03

Peper, E. & Williams, E.A. (1980). Autogenic therapy (pp. 131-137). In: A. C. Hastings, J. Fadiman, & J. S. Gordon (Eds.). Health for the whole person. Boulder: Westview Press.

Tsai, H. Y., Peper, E., & Lin, I. M. (2016). EEG patterns under positive/negative body postures and emotion recall tasks. NeuroRegulation, 3(1), 23-27.

Tseng, C., Abili, R., Peper, E., & Harvey, R. (2016). Reducing acne-stress and an integrated self-healing approach. Poster presented at the 47th Annual Meeting of the Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, Seattle WA, March 9-12, 2016.

[1] Adapted from: Peper, E., Miceli, B., & Harvey, R. (2016). Educational Model for Self-healing: Eliminating a Chronic Migraine with Electromyography, Autogenic Training, Posture, and Mindfulness. Biofeedback, 44(3), 130–137. https://biofeedbackhealth.files.wordpress.com/2011/01/a-educational-model-for-self-healing-biofeedback.pdf

Allow natural breathing with abdominal muscle biofeedback [1, 2]

Posted: April 26, 2016 Filed under: Breathing/respiration, self-healing, Uncategorized | Tags: abdominal breathing, biofeedback, EMG, Muscle feedback, respiration 7 CommentsWhen I allowed my lower abdomen to expand during inhalation without any striving and slightly constrict during exhalation, breathing was effortless. At the end of exhalation, I just paused and then the air flowed in without any effort. I felt profoundly relaxed and safe. With each effortless breath my hurry-up sickness dissipated.

Effortless breathing from a developmental perspective is a whole body process previously described by the works of Elsa Gindler, Charlotte Selver and Bess M. Mensendieck (Brooks, 1986; Bucholtz, 1994; Gilbert 2016, Mensendieck, 1954). These concepts underlie the the research and therapeutic approach of Jan van Dixhoorn (2008, 2014) and is also part of the treatment processes of Mensendieck/Cesar therapists (Profile Mensendeick) . During inhalation the body expands and during exhalation the body contracts. While sitting or standing, during exhalation the abdominal wall contracts and during inhalation the abdominal wall relaxes. This whole body breathing pattern is often absent in clients who tend to lift their chest and do not expand or sometimes even constrict their abdomen when they inhale . Even if their breathing includes some abdominal movement, often only the upper abdomen above the belly button moves while the lower abdomen shows limited or no movement. This may be associated with physical and emotional discomfort such as breathing difficulty, digestive problems, abdominal and pelvic floor pains, back pain, hyper vigilance, and anxiety. (The background, methodology to monitor and train with muscle biofeedback, and pragmatic exercises are described in detail in our recent published article, Peper, E., Booiman, A.C, Lin, I-M, Harvey, R., & Mitose, J. (2016). Abdominal SEMG Feedback for Diaphragmatic Breathing: A Methodological Note. Biofeedback. 44(1), 42-49.)

Some of the major factors that contribute to the absence of abdominal movement during breathing are (Peper et, 2015):

- ‘Designer jean syndrome’ (the modern girdle): The abdomen is constricted by a waist belt, tight pants or slimming underwear such as Spanx and in former days by the corset as shown in Figure 1 (MacHose & Peper, 1991; Peper & Tibbitts, 1994).

- Self-image: The person tends to pull his or her abdomen inward in an attempt to look slim and attractive.

- Defense reaction: The person unknowingly tenses the abdominal wall –a flexor response-in response to perceived threats (e.g., worry, external threat, loud noises, feeling unsafe). Defense reactions are commonly seen in clients with anxiety, panic or phobias.

- Learned disuse: The person covertly learned to inhibit any movement in the abdominal wall to protect themselves from experiencing pain because of prior abdominal injury or surgery (e.g., hernia or cesarean), abdominal pain (e.g., irritable bowel syndrome, dysmenorrhea, vulvodynia, pelvic floor pain, low back pain).

- Inability to engage abdominal muscles because of the lack of muscle tone.

Figure 1. How clothing constricts abdominal movement. Previously it was a corset as shown on the left and now it is Spanx or very tight clothing which restricts the waist.

Figure 1. How clothing constricts abdominal movement. Previously it was a corset as shown on the left and now it is Spanx or very tight clothing which restricts the waist.

Whether the lower abdominal muscles are engaged or not (either by chronic tightening or lack of muscle activation), the resultant breathing pattern tends to be more thoracic, shallow, rapid, irregular and punctuated with sighst. Over time participants may not able to activate or relax the lower abdominal muscles during the respiratory cycle. Thus it is no longer involved in whole body movement which can usually be observed in infants and young children.

In our published paper by Peper, E., Booiman, A.C, Lin, I-M, Harvey, R., & Mitose, J. (2016), we describe a methodology to re-establish effortless whole body breathing with the use of surface electromyography (SEMG) recorded from the lower abdominal muscles (external/ internal abdominal oblique and transverse abdominis) and strategies to teach engagement of these lower abdominal muscles. Using this methodology, the participants can once again learn how to activate the lower abdominal muscles to flatten the abdominal wall thereby pushing the diaphragm upward during exhalation. Then, during inhalation they can relax the muscles of the abdominal wall to expand the abdomen and allow the diaphragm to descend as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Correspondence between respiratory strain gauge changes and SEMG activity during breathing. When the person exhales, the lower abdominal SEMG activity increases and when the person inhales the SEMG decreases.

Figure 2. Correspondence between respiratory strain gauge changes and SEMG activity during breathing. When the person exhales, the lower abdominal SEMG activity increases and when the person inhales the SEMG decreases.

The published article discusses the factors that contribute to the breathing dysregulation and includes guidelines for using SEMG abdominal recording. It describes in detail–with illustrations–numerous practices such as tactile awareness of the lower abdomen, active movements such as pelvic rocking and cats and dogs exercises that people can practice to facilitate lower abdominal breathing. One of these practices, Sensing the lower abdomen during breathing, is developed and described by Annette Booiman, Mensendieck therapist

Sensing the lower abdomen during breathing

The person place their hands below their belly button with the outer edge of hands resting on the groin. During inhalation, they practice bringing their lower abdomen/belly into their hands so that the person can feel the lower abdomen expanding. During exhalation, they pull their lower abdomen inward and away from their palms as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Hands placed below the belly button to sense the movement of the lower abdomen.

Lower abdominal SEMG feedback is useful in retraining breathing for people with depression, rehabilitation after pregnancy, abdomen or chest surgery (e.g., Cesarean surgery, hernia, or appendectomy operations), anxiety, hyperventilation, stress-related disorders, difficulty to become pregnant or maintain pregnancy, pelvic floor problems, headache, low back pain, and lung diseases. As one participant reported:

“Biofeedback might be the single thing that helped me the most. When I began to focus on breathing, I realized that it was almost impossible for me since my body was so tightened. However, I am getting much better at breathing diaphragmatically because I practice every day. This has helped my body and it relaxes my muscles, which in turn help reduce the vulvar pain.”

REFERENCES

Mensendieck, B.M. (1954). Look better, feel better. Pymble, NSW, Australia: HarperCollins.

van Dixhoorn, J. (2008). Whole body breathing. Biofeedback. 3I(2), 54-58

Gilbert, C. (2016). Working with breathing , some early influences. Paper presented at the 47th Annual Meeting of the Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, Seattle WA, March 9-12, 2016.

1. Adapted from: Peper, E., Booiman, A., Lin, I-M, Harvey, R., & Mitose, J. (2016). Abdominal SEMG Feedback for Diaphragmatic Breathing: A Methodological Note. Biofeedback. 44(1), 42-49.

2. .I thank Annette Booiman for her constructive feedback in writing this blog.

Increase energy*

Posted: April 1, 2016 Filed under: self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: cognitive therapy, energy level, health, Holistic health, stress management 2 CommentsAre you full of pep and energy, ready to do more? Or do you feel drained and exhausted? After giving at the office, is there nothing left to give at home? Do you feel as if you are on a treadmill that will never stop, that more things feel draining than energizing?

Feeling chronically drained is often a precursor for illness; conversely, feeling energized enhances productivity and encourages health. An important aspect of staying healthy is that one’s daily activities are filled more with activities that contribute to our energy than with tasks and activities that drain our energy. Similarly, Dr. John Gottman and colleagues have discovered that marriages prosper when there are many more positive appreciations communicated by each partner than negative critiques.

Energy is the subjective sense of feeling alive and vibrant. An energy gain is an activity, task, or thought that makes you feel better and slightly more alive—those things we want to or choose to do. An energy drain is the opposite feeling—less alive and almost depressed—those things we have to or must do; often something that we do not want to do. In almost all cases, it is not that we have to, should, or must do, it is a choice. Remember, even though you may say, “I have to study.” It is a choice. You can choose not to study and choose to drop out of school. Similarly, when you say, “I have to do the dishes,” it is still a choice. You can choose to do the dishes or let the dirty dishes pile up and just use paper plates.

Energy drains and gains are always unique to the individual; namely, what is a drain for one can be a gain for another. Energy drains can be doing the dishes and feeling resentful that your partner or children are not doing them, or anticipating seeing a person whom you do not really want to see. An energy gain can be meeting a friend and talking or going for a walk in the woods, or finishing a work project.

When patients with cancer start exploring what they truly would like to do and start acting on their unfulfilled dreams, a few experience that their health improves as documented by Dr. Lawrence LeShan in his remarkable book, Cancer as a Turning Point. So often our lives are filled with things that we should do versus want to do. In some cases, the lives we created are not the ones we wanted but the result of self-doubt and worry, “If I did do this, my family and friends won’t like me”, or “I am not sure I will be successful so I will do something that is safe.” Just ask yourself the question when you woke up this morning and most mornings this week, “How did you feel?” Did you felt happy and looking forward to the day?

Explore strategies to decrease the drains and increase the energy gains. Use the following exercise to increase your energy:

- For one week monitor your energy drains and energy gains. Monitor events, activities, thoughts, or emotions that increase or decrease energy at home and at work. For example some drains can include cleaning bathroom, cooking another meal, or talking to a family member on the phone, while gains can be taking a walk, talking to a friend, completing a work task. Be very honest, just note the events that change your energy level.

- After the week look over your notes and identify at least one activity that drains your energy and one activity that increases your energy

- Develop a strategy to decrease one of the energy drains. Be very specific how, where, when, with whom, and which situations decreasing the tasks that drain your energy. As you think about it, anticipate obstacles that may interfere with reducing your drains and develop new ways to overcome these obstacles such as trading tasks with others (I will cook if you clean the bathroom), setting time limits, giving yourself positive reward after finishing the task (a cup of tea, a text or phone message to a close friend, watching a video in the evening).

- Develop new ways how you can increase energy gains such as doing exercise, completing a task.

- Each day implement the behavior to reduce one less energy drain and increase one energy gain and observe what happens.

Initially it may seem impossible, many students and clients report that the practice made them aware, increased their energy, and they had more control over their lives than they thought. It also encouraged them to explore the question, “What is it that you really want to do?” So often we do energy drains because of convention, habit and fear which makes us feel powerless and suppresses our immune system thereby increasing the risk of illness. In observing the energy drains and energy gains, it may give the person a choice. Sometimes, the choice is not changing the tasks but how we think about it. Many of the things we do are not MUSTs; they are choices. I do the work at my job because I choose to benefits of earning money.

How your internal language impacts your energy**

Sit and think of something that you feel you have to do, should do, or must do. Something you slightly dread such as cleaning the dishes, doing a math assignment. While sitting say to yourself, “I have to do, should do, or must do_______________.” Keep repeating the phrase for a minute.

Then change your internal phrase and instead say one of the following phrases, “I choose to do,” “I look forward to doing,” or “I choose not to do _________.” Keep repeating the phrase for a minute.

Now compare how you felt. Almost all people feel slight less energy and more depressed when they are thinking, “I have to do,” “should do”, or must do”. While when they shifted the phrase to, “I choose to,” “I look forward to doing,” or “I choose not to do it,” they feel lighter, more expanded and more optimistic. When university students practice this change of language during the week, they find it was easier to start and complete their homework tasks.

Watch your thoughts; they become words.

Watch your words; they become actions.

Watch your actions; they become habits.

Watch your habits; they become character.

Watch your character; it becomes your destiny.

– Frank Outlaw

References

Gottman, J.M. & Silver, N. (2015). The Seven Principles for Making Marriage Work. New York: Harmony.

LeShan, L. (1999). Cancer as a Turning Point. New York: Plume

*Adapted from: Peper, E. (2016). Increase energy. Western Edition. April, pp4. http://thewesternedition.com/admin/files/magazines/WE-April-2016.pdf

**Adapted from: Gorter, R. & Peper, E. (2011). Fighting Cancer-A Nontoxic Approach to Treatment. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books, 107-200.

Can abdominal surgery cause epilepsy, panic and anxiety and be reversed with breathing biofeedback?*

Posted: March 5, 2016 Filed under: Breathing/respiration, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: anxiety, biofeedback, Breathing, epilepsy, iatrogenic illness, learned disuse, panic, respiration, surgery 4 Comments“I had colon surgery six months ago. Although I made no connection to my anxiety, it just started to increase and I became fearful and I could not breathe. The asthma medication did not help. Learning effortless diaphragmatic breathing and learning to expand my abdomen during inhalation allowed me to breathe comfortably without panic and anxiety—I could breathe again.” (72 year old woman)

“One year after my appendectomy, I started to have twelve seizures a day. After practicing effortless diaphragmatic breathing and changing my lifestyle, I am now seizure-free.” (24 year old male college student)

One of the hidden long term costs of surgery and injury is covert learned disuse. Learned disuse occurs when a person inhibits using a part of their body to avoid pain and compensates by using other muscle patterns to perform the movements (Taub et al, 2006). This compensation to avoid discomfort creates a new habit pattern. However, the new habit pattern often induces functional impairment and creates the stage for future problems.

Many people have experienced changing their gait while walking after severely twisting their ankle or breaking their leg. While walking, the person will automatically compensate and avoid putting weight on the foot of the injured leg or ankle. These compensations may even leads to shoulder stiffness and pain in the opposite shoulder from the injured leg. Even after the injury has healed, the person may continue to move in the newly learned compensated gait pattern. In most cases, the person is totally unaware that his/her gait has changed. These new patterns may place extra strain on the hip and back and could become a hidden factor in developing hip pain and other chronic symptoms.

Similarly, some women who have given birth develop urinary stress incontinence when older. This occurred because they unknowingly avoided tightening their pelvic floor muscles after delivery because it hurt to tighten the stretched or torn tissue. Even after the tissue was healed, the women may no longer use their pelvic floor muscles appropriately. With the use of pelvic floor muscle biofeedback, many women with stress incontinence can rapidly learn to become aware of the inhibited/forgotten muscle patterns (learned disuse) and regain functional control in nine sessions of training (Burgio et al., 1998; Dannecker et al., 2005). The process of learned disuse is the result of single trial learning to avoid pain. Many of us as children have experienced this process when we touched a hot stove—afterwards we tended to avoid touching the stove even when it was cold.

Often injury will resolve/cure the specific problem. It may not undo the covert newly learned dysfunctional patterns which could contribute to future iatrogenic problems or illnesses (treatment induced illness). These iatrogenic illnesses are treated as a new illness without recognizing that they were the result of functional adaptations to avoid pain and discomfort in the recovery phase of the initial illness.

Surgery creates instability at the incision site and neighboring areas, so our bodies look for the path of least resistance and the best place to stabilize to avoid pain. (Adapted from Evan Osar, DC).

After successful surgical recovery do not assume you are healed!

Yes, you may be cured of the specific illness or injury; however, the seeds for future illness may be sown. Be sure that after injury or surgery, especially if it includes pain, you learn to inhibit the dysfunctional patterns and re-establish the functional patterns once you have recovered from the acute illness. This process is described in the two cases studies in which abdominal surgeries appeared to contribute to the development of anxiety and uncontrolled epilepsy.

How abdominal surgery can have serious, long-term effect on changing breathing patterns and contributing to the development of chronic illness.

When recovering from surgery or injury to the abdomen, it is instinctual for people to protect themselves and reduce pain by reducing the movement around the incision. They tend to breathe more shallowly as not to create discomfort or disrupt the healing process (e.g., open a stitch or staple. Prolonged shallow breathing over the long term may result in people experiencing hyperventilation induced panic symptoms or worse. This process is described in detail in our recent article, Did You Ask about Abdominal Surgery or Injury? A Learned Disuse Risk Factor for Breathing Dysfunction (Peper et al., 2015). The article describes two cases studies in which abdominal surgeries led to breathing dysfunction and ultimately chronic, serious illnesses.

Reducing epileptic seizures from 12 per week to 0 and reducing panic and anxiety

A routine appendectomy caused a 24-year-old male to develop rapid, shallow breathing that initiated a series of up to 12 seizures per week beginning a year after surgery. After four sessions of breathing retraining and incorporating lifestyle changes over a period of three months his uncontrolled seizures decreased to zero and is now seizure free. In the second example, a 39-year-old woman developed anxiety, insomnia, and panic attacks after her second kidney transplant probably due to shallow rapid breathing only in her chest. With biofeedback, she learned to change her breathing patterns from 25 breaths per minute without any abdominal movement to 8 breathes a minute with significant abdominal movement. Through generalization of the learned breathing skills, she was able to achieve control in situations where she normally felt out of control. As she practiced this skill her symptoms were significantly reduced and stated:

“What makes biofeedback so terrific in day-to-day situations is that I can do it at any time as long as I can concentrate. When I feel I can’t concentrate, I focus on counting and working with my diaphragm muscles; then my concentration returns. Because of the repetitive nature of biofeedback, my diaphragm muscles swing into action as soon as I started counting. When I first started, I had to focus on those muscles to get them to react. Getting in the car, I find myself starting these techniques almost immediately. Biofeedback training is wonderful because you learn techniques that can make challenging situations more manageable. For me, the best approach to any situation is to be calm and have peace of mind. I now have one more way to help me achieve this.” (From: Peper et al, 2001).

The commonality between these two participants was that neither realized that they were bracing the abdomen and were breathing rapidly and shallowly in the chest. I highly recommend that anyone who has experienced abdominal insults or surgery observe their breathing patterns and relearn effortless breathing/diaphragmatically breathing instead of shallow, rapid chest breathing often punctuated with breath holding and sighs.

It is important that medical practitioners and post-operative surgery patients recognize the common covert learned disuse patters such as shifting to shallow breathing to avoid pain. The sooner these patterns are identified and unlearned, the less likely will the person develop future iatrogenic illnesses. Biofeedback is an excellent tool to help identify and retrain these patterns and teach patients how to reestablish healthy/natural body patterns.

The full text of the article see: “Did You Ask About Abdominal Surgery or Injury? A Learned Disuse Risk Factor for Breathing Dysfunction,”

*Adapted from: Biofeedback Helps to Control Breathing Dysfunction.http://www.prweb.com/releases/2016/02/prweb13211732.htm

References

Burgio, K. L., Locher, J. L., Goode, P. S., Hardin, J. M., McDowell, B. J., Dombrowski, M., & Candib, D. (1998). Behavioral vs drug treatment for urge urinary incontinence in older women: a randomized controlled trial. Jama, 280(23), 1995-2000.

Dannecker, C., Wolf, V., Raab, R., Hepp, H., & Anthuber, C. (2005). EMG-biofeedback assisted pelvic floor muscle training is an effective therapy of stress urinary or mixed incontinence: a 7-year experience with 390 patients. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 273(2), 93-97.

Osar, E. (2016). http://www.fitnesseducationseminars.com/

Peper, E., Castillo, J., & Gibney, K. H. (2001, September). Breathing biofeedback to reduce side effects after a kidney transplant. In Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback (Vol. 26, No. 3, pp. 241-241). 233 Spring St., New York, NY 10013 USA: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publ.

Peper, E., Gilbert, C.D., Harvey, R. & Lin, I-M. (2015). Did you ask about abdominal surgery or injury? A learned disuse risk factor for breathing dysfunction. Biofeedback. 34(4), 173-179. DOI: 10.5298/1081-5937-43.4.06

Taub, E., Uswatte, G., Mark, V. W., Morris, D. M. (2006). The learned nonuse phenomenon: Implications for rehabilitation. Europa Medicophysica, 42(3), 241-256.

Resolving pelvic floor pain-A case report

Posted: September 25, 2015 Filed under: Breathing/respiration, Pain/discomfort, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: biofeedback, Breathing, electromyography, pain, posture, self-regulation, vulvodynia 10 CommentsAdapted from: Martinez Aranda, P. & Peper, E. (2015). The healing of vulvodynia from a client’s perspective. https://biofeedbackhealth.files.wordpress.com/2011/01/a-healing-of-vulvodynia-from-the-client-perspective-2015-06-15.pdf

It’s been a little over a year since I began practicing biofeedback and visualization strategies to overcome vulvodynia. Today, I feel whole, healed, and hopeful. I learned that through controlled and conscious breathing, I could unleash the potential to heal myself from chronic pain. Overcoming pain did not happen overnight; but rather, it was a process where I had to create and maintain healthy lifestyle habits and meditation. Not only am I thankful for having learned strategies to overcome chronic pain, but for acquiring skills that will improve my health for the rest of my life. –-24 year old woman who successfully resolved vulvodynia

Pelvic floor pain can be debilitating, and it is surprisingly common, affecting 10 to 25% of American women. Pelvic floor pain has numerous causes and names. It can be labeled as vulvar vestibulitis, an inflammation of vulvar tissue, interstitial cystitis (chronic pain or tenderness in the bladder), or even lingering or episodic hip, back, or abdominal pain. Chronic pain concentrated at the entrance to the vagina (vulva), is known as vulvodynia. It is commonly under-diagnosed, often inadequately treated, and can go on for months and years (Reed et al., 2007; Mayo Clinic, 2014). The discomfort can be so severe that sitting is uncomfortable and intercourse is impossible because of the extreme pain. The pain can be overwhelming and destructive of the patient’s life. As the participant reported,

I visited a vulvar specialist and he gave me drugs, which did not ease the discomfort. He mentioned surgical removal of the affected tissue as the most effective cure (vestibulectomy). I cried immediately upon leaving the physician’s office. Even though he is an expert on the subject, I felt like I had no psychological support. I was on Gabapentin to reduce pain, and it made me very depressed. I thought to myself: Is my life, as I know it, over?

Physically, I was in pain every single day. Sometimes it was a raging burning sensation, while other times it was more of an uncomfortable sensation. I could not wear my skinny jeans anymore or ride a bike. I became very depressed. I cried most days because I felt old and hopeless instead of feeling like a vibrant 23-year-old woman. The physical pain, combined with my negative feelings, affected my relationship with my boyfriend. We were unable to have sex at all, and because of my depressed status, we could not engage in any kind of fun. (For more details, read the published case report,Vulvodynia treated successfully with breathing biofeedback and integrated stress reduction: A case report).

The four-session holistic biofeedback interventions to successfully resolved vulvodynia included teaching diaphragmatic breathing to transform shallow thoracic breathing into slower diaphragmatic breathing, transforming feelings of powerlessness and hopelessness to empowerment and transforming her beliefs that she could reduce her symptoms and optimize her health. The interventions also incorporated self-healing imagery and posture-changing exercises. The posture changes consisted of developing awareness of the onset of moving into a collapsed posture and use this awareness to shift to an erect/empowered postures (Carney, Cuddy, & Yap, 2010; Peper, 2014; Peper, Booiman, Lin, & Harvey, in press). Finally, this case report build upon the seminal of electromyographic feedback protocol developed by Dr. Howard Glazer (Glazer & Hacad, 2015) and the integrated relaxation protocol developed Dr. David Wise (Wise & Anderson, 2007).

Through initial biofeedback monitoring of the lower abdominal muscle activity, chest, and abdomen breathing patterns, the participant observed that when she felt discomfort or was fearful, her lower abdomen muscles tended to tighten. After learning how to sense this tightness, she was able to remind herself to breathe lower and slower, relax the abdominal wall during inhalation and sit or stand in an erect power posture.

The self-mastery approach for healing is based upon a functional as compared to a structural perspective. The structural perspective implies that the problem can only be fixed by changing the physical structure such as with surgery or medications. The functional perspective assumes that if you can learn to change your dysfunctional psychophysiological patterns the disorder may disappear.

The functional approach assumed that an irritation of the vestibular area might have caused the participant to tighten her lower abdomen and pelvic floor muscles reflexively in a covert defense reaction. In addition, ongoing worry and catastrophic thinking (“I must have surgery, it will never go away, I can never have sex again, my boyfriend will leave me”) also triggered the defense reaction—further tightening of her lower abdomen and pelvic area, shallow breathing, and concurrent increases in sympathetic nervous activation—which together activated the trigger points that lead to increased chronic pain (Banks et al, 1998).

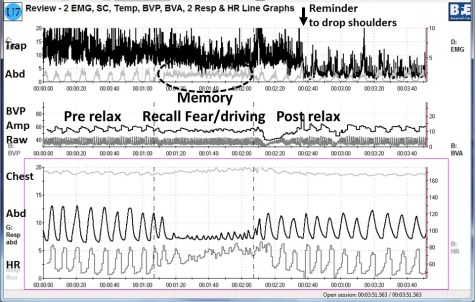

When the participant experienced a sensation or thought/worried about the pain, her body responded in a defense reaction by breathing in her chest and tightening the lower abdominal area as monitored with biofeedback. Anticipation of being monitored increased her shoulder tension, recalling the stressful memory increased lower abdominal muscle tension (pulling in the abdomen for protection), and the breathing became shallow and rapid as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Physiological recording of pre-stressor relaxation, the recall of a fearful driving experience, and a post-stressor relaxation. The scalene to trapezius SEMG increased in anticipation while she recalled the experience, and then initially did not relax (from Peper, Martinez Aranda, & Moss, 2015).

This defense pattern became a conditioned response—initiating intercourse or being touched in the affected area caused the participant to tense and freeze up. She was unaware of these automatic protective patterns, which only worsened her chronic pain.

During the four sessions of training, the participant learned to reverse and interrupt the habitual defense reaction. For example, as she became aware of her breathing patterns she reported,

It was amazing to see on the computer screen the difference between my regular breathing pattern and my diaphragmatic breathing pattern. I could not believe I had been breathing that horribly my whole life, or at least, for who knows how long. My first instinct was to feel sorry for myself. Then, rather than practicing negative patterns and thoughts, I felt happy because I was learning how to breathe properly. My pain decreased from an 8 to alternating between a 0 and 3.

The mastery of slower and lower abdominal breathing within a holistic perspective resulted in the successful resolution of her vulvodynia. An essential component of the training included allowing the participant to feel safe, and creating hope by enabling her to experience a decrease in discomfort while doing a specific practice, and assisting her to master skills to promote self-healing. Instead of feeling powerless and believing that the only resolution was the removal of the affected area (vestibulectomy). The integrated biofeedback protocol offered skill mastery training, to promote self-healing through diaphragmatic breathing, somatic postural changes, reframing internal language, and healing imagery as part of a common sense holistic health approach.

For more details about the case report, download the published study, Peper, E., Martinez Aranda, P., & Moss, E. (2015). Vulvodynia treated successfully with breathing biofeedback and integrated stress reduction: A case report. Biofeedback. 43(2), 103-109.

The participant also wrote up her subjective experience of the integrated biofeedback process in the paper, Martinez Aranda & Peper (2015). Healing of vulvodynia from the client perspective. In this paper she articulated her understanding and experiences in resolving vulvodynia which sheds light on the internal processes that are so often skipped over in published reports.

At the five year follow-up on May 29, 2019, she wrote:

“I am doing very well, and I am very healthy. The vulvodynia symptoms have never come back. It migrated to my stomach a couple of years after, and I still have a sensitive stomach. My stomach has gotten much, much better, though. I don’t really have random pain anymore, now I just have to be watchful and careful of my diet and my exercise, which are all great things!”

References

Banks, S. L., Jacobs, D. W., Gevirtz, R., & Hubbard, D. R. (1998). Effects of autogenic relaxation training on electromyographic activity in active myofascial trigger points. Journal of Musculoskeletal Pain, 6(4), 23-32. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/David_Hubbard/publication/232035243_Effects_of_Autogenic_Relaxation_Training_on_Electromyographic_Activity_in_Active_Myofascial_Trigger_Points/links/5434864a0cf2dc341daf4377.pdf

Carney, D. R., Cuddy, A. J., & Yap, A. J. (2010). Power posing brief nonverbal displays affect neuroendocrine levels and risk tolerance. Psychological Science, 21(10), 1363-1368. Available from: https://www0.gsb.columbia.edu/mygsb/faculty/research/pubfiles/4679/power.poses_.PS_.2010.pdf

Glazer, H. & Hacad, C.R. (2015). The Glazer Protocol: Evidence-Based Medicine Pelvic Floor Muscle (PFM) Surface Electromyography (SEMG). Biofeedback, 40(2), 75-79. http://www.aapb-biofeedback.com/doi/abs/10.5298/1081-5937-40.2.4

Martinez Aranda, P. & Peper, E. (2015). Healing of vulvodynia from the client perspective. Available from: https://biofeedbackhealth.files.wordpress.com/2011/01/a-healing-of-vulvodynia-from-the-client-perspective-2015-06-15.pdf

Mayo Clinic (2014). Diseases and conditions: Vulvodynia. Available at http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/vulvodynia/basics/definition/con-20020326

Peper, E. (2014). Increasing strength and mood by changing posture and sitting habits. Western Edition, pp.10, 12. Available from: http://thewesternedition.com/admin/files/magazines/WE-July-2014.pdf

Peper, E., Booiman, A., Lin, I, M.,& Harvey, R. (in press). Increase strength and mood with posture. Biofeedback.

Peper, E., Martinez Aranda, P., & Moss, E. (2015). Vulvodynia treated successfully with breathing biofeedback and integrated stress reduction: A case report. Biofeedback. 43(2), 103-109. Available from: https://biofeedbackhealth.files.wordpress.com/2011/01/a-vulvodynia-treated-with-biofeedback-published.pdf

Reed, B. D., Haefner, H. K., Sen, A., & Gorenflo, D. W. (2008). Vulvodynia incidence and remission rates among adult women: a 2-year follow-up study. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 112(2, Part 1), 231-237. http://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/Abstract/2008/08000/Vulvodynia_Incidence_and_Remission_Rates_Among.6.aspx

Wise, D., & Anderson, R. U. (2006). A headache in the pelvis: A new understanding and treatment for prostatitis and chronic pelvic pain syndromes. Occidental, CA: National Center for Pelvic Pain Research.http://www.pelvicpainhelp.com/books/

Interrupt Chained Behaviors: Overcome Smoking, Eczema, and Hair Pulling

Posted: March 7, 2015 Filed under: self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: chained behavior, eczema, hair pulling, healing, self-monitoring, smoking cessation, stress management, trichotillomania 7 Comments“I am proud to label myself a nonsmoker… diligently performing practices has profoundly helped me eliminate my troublesome craving…The conscious efforts I have made over the past month have helped me regain control of my life.” –L. F., a college student who became a non-smoker after smoking up to two packs a day since age 11. At 18 month follow-up L. F. is still a nonsmoker.

“I have been struggling with eczema for most of my life and until I began this course, I was feeling very hopeless in managing this condition without the use of costly, and potentially dangerous drugs. My self-healing project proved to be empirically successful. My eczema shrunk in size from 72 mm in length and 63 mm in width as measured at baseline to 0 mm in length and 0 mm in width by the final day of this project.” –L. C., a college student who experienced recurring scaly skin patches since childhood.

In our recent published paper, Transforming chained behaviors: Case studies of overcoming smoking, eczema and hair pulling (trichotillomania), we describe an approach by which students learn self-healing techniques which they practice as part of a semester long class project. After four weeks of of self-healing practices many of the students report significant decrease in symptoms and improvement of health as shown in Figure 1. Their success includes smoking cessation, eliminating hair pulling and eczema disappearing.

Figure 1. Students’ self-rating of success in achieving health benefits after four weeks of practice.

Figure 1. Students’ self-rating of success in achieving health benefits after four weeks of practice.

One component of the self-healing process is interrupting chained behavior. We react automatically and respond instantly with sadness, anger, neck and shoulders tension, eating too much, veg’ing out watching videos, or playing mindless digital games. After a time, we may notice that we are smoking more, experiencing an upset stomach, back pain, headaches, high blood pressure, or even more skin eruptions. The first step is to sense the initial reaction that leads to the symptom development. Then, the person performs an alternative health promoting behavior and interrupts the chained behavior that triggers symptoms as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Interrupting and transforming the chained behavior. The moment person become aware of the trigger or behavior that is chained to the development of the symptom, he/she interrupts and performs an active new health promoting behavior as illustrated by the dashed lines.

Figure 2. Interrupting and transforming the chained behavior. The moment person become aware of the trigger or behavior that is chained to the development of the symptom, he/she interrupts and performs an active new health promoting behavior as illustrated by the dashed lines.

Overtime these automatic patterns may contribute to the development of autoimmune diseases, increased vulnerability to infections or other chronic diseases. The challenge is to develop an awareness to recognize and interrupt the beginning of the ‘chain of behavior.’ The instant you become aware of the first reaction, do something different, such as,

- Shift your focus of attention to something joyful

- Chang your body position and smile while thinking, This will also pass.

- Practice a quick relaxation technique.

- Imagine a positive self-healing process.

The longer the person waits to interrupt the chain, the more difficult it is to redirect the chained behavior. Awareness and immediate interruption appears to be major factors in achieving success. It means practicing the interruption and new behavior all day long. This is different from from practicing a skill for twenty minutes a day and the rest of the time performing the old dysfunctional behavior.

Mastery of this process consists of three steps:

- Becoming aware of what is happening when the chain reactions.

- Learn a more functional alternative health behavior such as breathing, relaxing, focusing on empowering thought, eating other foods.

- Substitute the alternative behavior the moment you become aware of the triggered dysfunctional behavior.

After having integrated this into daily life, many students report experiencing a significant reduction and even elimination of symptoms and behaviors.

“I will continue to do the practices outlined not only to overcome trichotillomania but also to control my anxiety and, therefore, lead a less stressed and happier life. Knowing I have the power to heal myself is such an inspiring feeling, a feeling that can’t adequately be put into words.” –G. M., a 32 year old student with trichotillomania, who reduced her hair pulling, anxiety, and stress

“I have gained much wisdom from this project…I am ultimately responsible for my own health and well-being…I feel empowered, optimistic, and appreciative of every moment.” –L. C., a college student who experienced recurring scaly skin patches since childhood)

For background, specific techniques and successful case reports, read our published paper, Peper, E., Lin, I-M, Harvey, R., Gilbert, M., Gubbala, P., Ratkovich, A., & Fletcher, F. (2014). Transforming chained behaviors: Case studies of overcoming smoking, eczema and hair pulling (trichotillomania). Biofeedback, 42(4), 154-160.

Reduce hot flashes and premenstrual symptoms with breathing

Posted: February 18, 2015 Filed under: Breathing/respiration, Pain/discomfort, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: biofeedback, Breathing, diaphragmatic breathing, heart rate variability, hormone replacement therapy, hot flashes, HRT, Menopause, respiration, sighs, stress, sympathetic activity 6 CommentsAfter the first week to my astonishment, I have fewer hot flashes and they bother me less. Each time I feel the warmth coming, I breathe out slowly and gently. To my surprise they are less intense and are much less frequent. I keep breathing slowly throughout the day. This is quite a surprise because I was referred for biofeedback training because of headaches that occurred after getting a large electrical shock. After 5 sessions my headaches have decreased and I can control them, and my hot flashes have decreased from 3-4 per day to 1-2 per week. -50 year old client

After students in my Holistic Health class at San Francisco State University practiced slower diaphragmatic breathing and begun to change their dysfunctional shallow breathing, gasping, sighing, and breath holding to diaphragmatic breathing. A number of the older female students students reported that their hot flashes decreased. Some of the younger female students reported that their menstrual cramps and discomfort were reduced by 80 to 90% when they laid down and breathed slower and lower into their abdomen.

The recent study in JAMA reported that many women continue to experience menopausal triggered hot flashes for up to 14 years. Although the article described the frequency and possible factors that were associated with the prolonged hot flashes, it did not offer helpful solutions.

The recent study in JAMA reported that many women continue to experience menopausal triggered hot flashes for up to 14 years. Although the article described the frequency and possible factors that were associated with the prolonged hot flashes, it did not offer helpful solutions.

Another understanding of the dynamics of hot flashes is that the decrease in estrogen accentuates the sympathetic/ parasympathetic imbalances that probably already existed. Then any increase in sympathetic activation can trigger a hot flash. In many cases the triggers are events and thoughts that trigger a stress response, emotional responses such as anger, anxiety, or worry, increase caffeine intake and especially shallow chest breathing punctuated with sighs. Approximately 80% of American women tend to breathe thoracically often punctuated with sighs and these women are more likely to experience hot flashes. On the other hand, the 20% of women who habitually breathe diaphragmatically tend to have fewer and less intense hot flashes and often go through menopause without any discomfort. In the superb study Drs. Freedman and Woodward (1992), taught women who experience hot flashes to breathe slowly and diaphragmatically which increased their heart rate variability as an indicator of sympathetic/parasympathetic balance and most importantly it reduced the the frequency and intensity of hot flashes by 50%.

Test the breathing connection if you experience hot flashes

Take a breath into your chest and rapidly exhale with a sigh. Repeat this quickly five times. In most cases, one minute later you will experience the beginning sensations of a hot flash. Similarly, when you practice slow diaphragmatic breathing throughout the day and interrupt every gasp, breath holding moment, sigh or shallow chest breathing with slower diaphragmatic breathing, you will experience a significant reduction in hot flashes.

Although this breathing approach has been well documented, many people are unaware of this simple behavioral approach unlike the common recommendation for the hormone replacement therapies (HRT) to ameliorate menopausal symptoms. This is not surprising since pharmaceutical companies spent nearly five billion dollars per year in direct to consumer advertising for drugs and very little money is spent on advertising behavioral treatments. There is no profit for pharmaceutical companies teaching effortless diaphragmatic breathing unlike prescribing HRTs. In addition, teaching and practicing diaphragmatic breathing takes skill training and practice time–time which is not reimbursable by third party payers.

For more information, research data and breathing skills to reduce hot flash intensity, see our article which is reprinted below.

Gibney, H.K. & Peper, E. (2003). Taking control: Strategies to reduce hot flashes and premenstrual mood swings. Biofeedback, 31(3), 20-24.

Taking control: Strategies to reduce hot flashes and premenstrual mood swings*

Erik Peper, Ph.D**., and Katherine H. Gibney

San Francisco State University

After the first week to my astonishment, I have fewer hot flashes and they bother me less. Each time I feel the warmth coming, I breathe out slowly and gently. To my surprise they are less intense and are much less frequent. I keep breathing slowly throughout the day. This is quite a surprise because I was referred for biofeedback training because of headaches that occurred after getting a large electrical shock. After 5 sessions my headaches have decreased and I can control them, and my hot flashes have decreased from 3-4 per day to 1-2 per week. -50 year old client

For the first time in years, I experienced control over my premenstrual mood swings. Each time I could feel myself reacting, I relaxed, did my autogenic training and breathing. I exhaled. It brought me back to center and calmness. -26 year old student

Abstract

Women have been troubled by hot flashes and premenstrual syndrome for ages. Hormone replacement therapy, historically the most common treatment for hot flashes, and other pharmacological approaches for pre-menstrual syndrome (PMS) appear now to be harmful and may not produce significant benefits. This paper reports on a model treatment approach based upon the early research of Freedman & Woodward to reduce hot flashes and PMS using biofeedback training of diaphragmatic breathing, relaxation, and respiratory sinus arrhythmia. Successful symptom reduction is contingent upon lowering sympathetic arousal utilizing slow breathing in response to stressors and somatic changes. We strongly recommend that effortless diaphragmatic breathing be taught as the first step to reduce hot flashes and PMS symptoms.

A long and uncomfortable history

Women have been troubled by hot flashes and premenstrual syndrome for ages. Hot flashes often result in red faces, sweating bodies, and noticeable and embarrassing discomfort. They come in the middle of meetings, in the middle of the night, and in the middle of romantic interludes. Premenstrual syndrome also arrives without notice, bringing such symptoms as severe mood swings, anger, crying, and depression.

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) was the most common treatment for hot flashes for decades. However, recent randomized controlled trials show that the benefits of HRT are less than previously thought and the risks—especially of invasive breast cancer, coronary artery disease, dementia, stroke and venous thromboembolism—are greater (Humphries & Gill, 2003; Shumaker, et al, 2003; Wassertheil-Smoller, et al, 2003). In addition, there is no evidence of increased quality of life improvements (general health, vitality, mental health, depressive symptoms, or sexual satisfaction) as claimed for HRT (Hays et al, 2003).

“As a result of recent studies, we know that hormone therapy should not be used to prevent heart disease. These studies also report an increased risk of heart attack, stroke, breast cancer, blood clots, and dementia…” -Wyeth Pharmaceuticals (2003)

Because of the increased long-term risk and lack of benefit, many physicians are weaning women off HRT at a time when the largest population of maturing women in history (‘baby boomers’) is entering menopausal years. The desire to find a reliable remedy for hot flashes is on the front burner of many researchers’ minds, not to mention the minds of women suffering from these ‘uncontrollable’ power surges. Yet, many women are becoming increasingly leery of the view that menopause is an illness. There is a rising demand to find a natural remedy for this natural stage in women’s health and development.

For younger women a similar dilemma occurs when they seek treatment of discomfort associated with their menstrual cycle. Is premenstrual syndrome (PMS) just a natural variation in energy and mood levels? Or, are women expected to adapt to a masculine based environment that requires them to override the natural tendency to perform in rhythm with their own psychophysiological states? Instead of perceiving menstruation as a natural occurrence in which one has different moods and/or energy levels, women in our society are required to perform at the status quo, which may contribute to PMS. The feelings and mood changes are quickly labeled as pathology that can only be treated with medication.

Traditionally, premenstrual syndrome is treated with pharmaceuticals, such as birth control pills or Danazol. Although medications may alleviate some symptoms, many women experience unpleasant side effects, such as bloating or acne, and still experience a variety of PMS symptoms. Many cannot tolerate the medications. Thus, millions of women (and families) suffer monthly bouts of ‘uncontrollable’ PMS symptoms

For both hot flashes and PMS the biomedical model tends to frame the symptoms as a “structural biological problem.” Namely, the pathology occurs because the body is either lacking in, or has an excess of, some hormone. All that needs to be done is either augment or suppress hormones/symptoms with some form of drug. Recently, for example, medicine has turned to antidepressant medications to address menopausal hot flashes (Stearns, Beebe, Iyengar, & Dube, 2003).

The biomedical model, however, is only one perspective. The opposite perspective is that the dysfunction occurs because of how we use ourselves. Use in this sense means our thoughts, emotions and body patterns. As we use ourselves, we change our physiology and, thereby, may affect and slowly change the predisposing and maintaining factors that contribute to our dysfunction. By changing our use, we may reduce the constraints that limit the expression of the self-healing potential that is intrinsic in each person.

The intrinsic power of self-healing is easily observed when we cut our finger. Without the individual having to do anything, the small cut bleeds, clotting begin and tissue healing is activated. Obviously, we can interfere with the healing process, such as when we scrape the scab, rub dirt in the wound, reduce blood flow to the tissue or feel anxious or afraid. Conversely, cleaning the wound, increasing blood flow to the area, and feeling “safe” and relaxed can promote healing. Healing is a dynamic process in which both structure and use continuously affect each other. It is highly likely that menopausal hot flashes and PMS mood swings are equally an interaction of the biological structure (hormone levels) and the use factor (sympathetic/parasympathetic activation).

Uncontrollable or overly aroused?

Are the hot flashes and PMS mood swings really ‘uncontrollable?’ From a physiological perspective, hot flashes are increased by sympathetic arousal. When the sympathetic system is activated, whether by medication or by emotions, hot flashes increase and similarly, when sympathetic activity decreases hot flashes decrease. Equally, PMS, with its strong mood swings, is aggravated by sympathetic arousal. There are many self-management approaches that can be mastered to change and reduce sympathetic arousal, such as breathing, meditation, behavioral cognitive therapy, and relaxation.

Breathing patterns are closely associated with hot flashes. During sleep, a sigh generally occurs one minute before a hot flash as reported by Freedman and Woodward (1992). Women who habitually breathe thoracically (in the chest) report much more discomfort and hot flashes than women who habitually breathe diaphragmatically. Freedman, Woodward, Brown, Javaid, and Pandey (1995) and Freedman and Woodward (1992) found that hot flash rates during menopause decreased in women who practiced slower breathing for two weeks. In their studies, the control groups received alpha electroencephalographic feedback and did not benefit from a reduction of hot flashes. Those who received training in paced breathing reduced the frequency of their hot flashes by 50% when they practiced slower breathing. This data suggest that the slower breathing has a significant effect on the sympathetic and parasympathetic balance.

Women with PMS appear similarly able to reduce their discomfort. An early study utilizing Autogenic Training (AT) combined with an emphasis on warming the lower abdomen resulted in women noting improvement in dysfunctional bleeding (Luthe & Schultz, 1969, pp. 144-148). Using a similar approach, Mathew, Claghorn, Largen, and Dobbins (1979) and Dewit (1981) found that biofeedback temperature training was helpful in reducing PMS symptoms.. A later study by Goodale, Domar, and Benson (1990) found that women with severe PMS symptoms who practiced the relaxation response reported a 58% improvement in overall symptomatology as compared to a 27.2% improvement for the reading control group and a 17.0% improvement for the charting group.

Teaching control and achieving results

Teaching women to breathe effortlessly can lead to positive results and an enhanced sense of control. By effortless breathing, the authors refer to their approach to breath training, which involves a slow, comfortable respiration, larger volume of air exchange, and a reliance upon action of the muscles of the diaphragm rather than the chest (Peper, 1990). For more instructions see the recent blog, A breath of fresh air: Improve health with breathing.

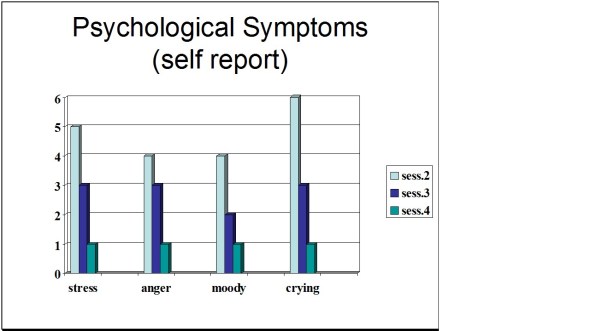

Slowing breathing helps to limit the sighs common to rapid thoracic breathing—sighs that often precede menopausal hot flashes. Effortless breathing is associated with stress reduction—stress and mood swings are common concerns of women suffering from PMS. In a pilot study Bier, Kazarian, Peper, and Gibney (2003) at San Francisco State University (SFSU) observed that when the subject practiced diaphragmatic breathing throughout the month, combined with Autogenic Training, her premenstrual psychological symptoms (anger, depressed mood, crying) and premenstrual responses to stressors were significantly reduced as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Student’s Individual Subjective Rating in Response to PMS Symptoms.

In another pilot study at SFSU, Frobish, Peper, and Gibney (2003) trained a volunteer who suffered from frequent hot flashes to breathe diaphragmatically. The training goals included modifying breathing patterns, producing a Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia (RSA), and peripheral hand warming. RSA refers to a pattern of slow, regular breathing during which variations in heart rate enter into a synchrony with the respiration. Each inspiration is accompanied by an increase in heart rate, and each expiration is accompanied by a decrease in heart rate (with some phase differences depending on the rate of breathing). The presence of the RSA pattern is an indication of optimal balance between sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous activity.

During the 11-day study period, the subject charted the occurrence of hot flashes and noted a significant decrease by day 5. However, on the evening of day 7 she sprained her ankle and experienced a dramatic increase in hot flashes on day 8. Once the subject recognized her stress response, she focused more on breathing and was able to reduce the flashes as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Subjective rating of intensity, frequency and bothersomeness of hot flashes. The increase in hot flashes coincided with increased frustration about an ankle injury.

Our clinical experience confirms the SFSU pilot studies and the previously referenced research by Freedman and Woodward (1992) and Freedman et al. (1995). When arousal is lowered and breathing is effortless, women are better able to cope with stress and report a reduction in symptoms. Habitual rapid thoracic breathing tends to increase arousal while slower breathing, especially slower exhalation, tends to relax and reduce arousal. Learning and then applying effortless breathing reduces excessive sympathetic arousal. It also interrupts the cycle of cognitive activation, anxiety, and somatic arousal. The anticipation and frustration at having hot flashes becomes the cue to shift attention and “breathe slower and lower.” This process stops the cognitively mediated self-activation.

Successful self-regulation and the return to health begin with cognitive reframing: We are not only a genetic biological fixed (deficient) structure but also a dynamic changing system in which all parts (thoughts, emotions, behavior, diet, stress, and physiology) affect and are effected by each other. Within this dynamic changing system, there is an opportunity to implement and practice behaviors and life patterns that promote health.

Learning Diaphragmatic Breathing with and without Biofeedback