Reduce hot flashes and premenstrual symptoms with breathing

Posted: February 18, 2015 Filed under: Breathing/respiration, Pain/discomfort, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: biofeedback, Breathing, diaphragmatic breathing, heart rate variability, hormone replacement therapy, hot flashes, HRT, Menopause, respiration, sighs, stress, sympathetic activity 6 CommentsAfter the first week to my astonishment, I have fewer hot flashes and they bother me less. Each time I feel the warmth coming, I breathe out slowly and gently. To my surprise they are less intense and are much less frequent. I keep breathing slowly throughout the day. This is quite a surprise because I was referred for biofeedback training because of headaches that occurred after getting a large electrical shock. After 5 sessions my headaches have decreased and I can control them, and my hot flashes have decreased from 3-4 per day to 1-2 per week. -50 year old client

After students in my Holistic Health class at San Francisco State University practiced slower diaphragmatic breathing and begun to change their dysfunctional shallow breathing, gasping, sighing, and breath holding to diaphragmatic breathing. A number of the older female students students reported that their hot flashes decreased. Some of the younger female students reported that their menstrual cramps and discomfort were reduced by 80 to 90% when they laid down and breathed slower and lower into their abdomen.

The recent study in JAMA reported that many women continue to experience menopausal triggered hot flashes for up to 14 years. Although the article described the frequency and possible factors that were associated with the prolonged hot flashes, it did not offer helpful solutions.

The recent study in JAMA reported that many women continue to experience menopausal triggered hot flashes for up to 14 years. Although the article described the frequency and possible factors that were associated with the prolonged hot flashes, it did not offer helpful solutions.

Another understanding of the dynamics of hot flashes is that the decrease in estrogen accentuates the sympathetic/ parasympathetic imbalances that probably already existed. Then any increase in sympathetic activation can trigger a hot flash. In many cases the triggers are events and thoughts that trigger a stress response, emotional responses such as anger, anxiety, or worry, increase caffeine intake and especially shallow chest breathing punctuated with sighs. Approximately 80% of American women tend to breathe thoracically often punctuated with sighs and these women are more likely to experience hot flashes. On the other hand, the 20% of women who habitually breathe diaphragmatically tend to have fewer and less intense hot flashes and often go through menopause without any discomfort. In the superb study Drs. Freedman and Woodward (1992), taught women who experience hot flashes to breathe slowly and diaphragmatically which increased their heart rate variability as an indicator of sympathetic/parasympathetic balance and most importantly it reduced the the frequency and intensity of hot flashes by 50%.

Test the breathing connection if you experience hot flashes

Take a breath into your chest and rapidly exhale with a sigh. Repeat this quickly five times. In most cases, one minute later you will experience the beginning sensations of a hot flash. Similarly, when you practice slow diaphragmatic breathing throughout the day and interrupt every gasp, breath holding moment, sigh or shallow chest breathing with slower diaphragmatic breathing, you will experience a significant reduction in hot flashes.

Although this breathing approach has been well documented, many people are unaware of this simple behavioral approach unlike the common recommendation for the hormone replacement therapies (HRT) to ameliorate menopausal symptoms. This is not surprising since pharmaceutical companies spent nearly five billion dollars per year in direct to consumer advertising for drugs and very little money is spent on advertising behavioral treatments. There is no profit for pharmaceutical companies teaching effortless diaphragmatic breathing unlike prescribing HRTs. In addition, teaching and practicing diaphragmatic breathing takes skill training and practice time–time which is not reimbursable by third party payers.

For more information, research data and breathing skills to reduce hot flash intensity, see our article which is reprinted below.

Gibney, H.K. & Peper, E. (2003). Taking control: Strategies to reduce hot flashes and premenstrual mood swings. Biofeedback, 31(3), 20-24.

Taking control: Strategies to reduce hot flashes and premenstrual mood swings*

Erik Peper, Ph.D**., and Katherine H. Gibney

San Francisco State University

After the first week to my astonishment, I have fewer hot flashes and they bother me less. Each time I feel the warmth coming, I breathe out slowly and gently. To my surprise they are less intense and are much less frequent. I keep breathing slowly throughout the day. This is quite a surprise because I was referred for biofeedback training because of headaches that occurred after getting a large electrical shock. After 5 sessions my headaches have decreased and I can control them, and my hot flashes have decreased from 3-4 per day to 1-2 per week. -50 year old client

For the first time in years, I experienced control over my premenstrual mood swings. Each time I could feel myself reacting, I relaxed, did my autogenic training and breathing. I exhaled. It brought me back to center and calmness. -26 year old student

Abstract

Women have been troubled by hot flashes and premenstrual syndrome for ages. Hormone replacement therapy, historically the most common treatment for hot flashes, and other pharmacological approaches for pre-menstrual syndrome (PMS) appear now to be harmful and may not produce significant benefits. This paper reports on a model treatment approach based upon the early research of Freedman & Woodward to reduce hot flashes and PMS using biofeedback training of diaphragmatic breathing, relaxation, and respiratory sinus arrhythmia. Successful symptom reduction is contingent upon lowering sympathetic arousal utilizing slow breathing in response to stressors and somatic changes. We strongly recommend that effortless diaphragmatic breathing be taught as the first step to reduce hot flashes and PMS symptoms.

A long and uncomfortable history

Women have been troubled by hot flashes and premenstrual syndrome for ages. Hot flashes often result in red faces, sweating bodies, and noticeable and embarrassing discomfort. They come in the middle of meetings, in the middle of the night, and in the middle of romantic interludes. Premenstrual syndrome also arrives without notice, bringing such symptoms as severe mood swings, anger, crying, and depression.

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) was the most common treatment for hot flashes for decades. However, recent randomized controlled trials show that the benefits of HRT are less than previously thought and the risks—especially of invasive breast cancer, coronary artery disease, dementia, stroke and venous thromboembolism—are greater (Humphries & Gill, 2003; Shumaker, et al, 2003; Wassertheil-Smoller, et al, 2003). In addition, there is no evidence of increased quality of life improvements (general health, vitality, mental health, depressive symptoms, or sexual satisfaction) as claimed for HRT (Hays et al, 2003).

“As a result of recent studies, we know that hormone therapy should not be used to prevent heart disease. These studies also report an increased risk of heart attack, stroke, breast cancer, blood clots, and dementia…” -Wyeth Pharmaceuticals (2003)

Because of the increased long-term risk and lack of benefit, many physicians are weaning women off HRT at a time when the largest population of maturing women in history (‘baby boomers’) is entering menopausal years. The desire to find a reliable remedy for hot flashes is on the front burner of many researchers’ minds, not to mention the minds of women suffering from these ‘uncontrollable’ power surges. Yet, many women are becoming increasingly leery of the view that menopause is an illness. There is a rising demand to find a natural remedy for this natural stage in women’s health and development.

For younger women a similar dilemma occurs when they seek treatment of discomfort associated with their menstrual cycle. Is premenstrual syndrome (PMS) just a natural variation in energy and mood levels? Or, are women expected to adapt to a masculine based environment that requires them to override the natural tendency to perform in rhythm with their own psychophysiological states? Instead of perceiving menstruation as a natural occurrence in which one has different moods and/or energy levels, women in our society are required to perform at the status quo, which may contribute to PMS. The feelings and mood changes are quickly labeled as pathology that can only be treated with medication.

Traditionally, premenstrual syndrome is treated with pharmaceuticals, such as birth control pills or Danazol. Although medications may alleviate some symptoms, many women experience unpleasant side effects, such as bloating or acne, and still experience a variety of PMS symptoms. Many cannot tolerate the medications. Thus, millions of women (and families) suffer monthly bouts of ‘uncontrollable’ PMS symptoms

For both hot flashes and PMS the biomedical model tends to frame the symptoms as a “structural biological problem.” Namely, the pathology occurs because the body is either lacking in, or has an excess of, some hormone. All that needs to be done is either augment or suppress hormones/symptoms with some form of drug. Recently, for example, medicine has turned to antidepressant medications to address menopausal hot flashes (Stearns, Beebe, Iyengar, & Dube, 2003).

The biomedical model, however, is only one perspective. The opposite perspective is that the dysfunction occurs because of how we use ourselves. Use in this sense means our thoughts, emotions and body patterns. As we use ourselves, we change our physiology and, thereby, may affect and slowly change the predisposing and maintaining factors that contribute to our dysfunction. By changing our use, we may reduce the constraints that limit the expression of the self-healing potential that is intrinsic in each person.

The intrinsic power of self-healing is easily observed when we cut our finger. Without the individual having to do anything, the small cut bleeds, clotting begin and tissue healing is activated. Obviously, we can interfere with the healing process, such as when we scrape the scab, rub dirt in the wound, reduce blood flow to the tissue or feel anxious or afraid. Conversely, cleaning the wound, increasing blood flow to the area, and feeling “safe” and relaxed can promote healing. Healing is a dynamic process in which both structure and use continuously affect each other. It is highly likely that menopausal hot flashes and PMS mood swings are equally an interaction of the biological structure (hormone levels) and the use factor (sympathetic/parasympathetic activation).

Uncontrollable or overly aroused?

Are the hot flashes and PMS mood swings really ‘uncontrollable?’ From a physiological perspective, hot flashes are increased by sympathetic arousal. When the sympathetic system is activated, whether by medication or by emotions, hot flashes increase and similarly, when sympathetic activity decreases hot flashes decrease. Equally, PMS, with its strong mood swings, is aggravated by sympathetic arousal. There are many self-management approaches that can be mastered to change and reduce sympathetic arousal, such as breathing, meditation, behavioral cognitive therapy, and relaxation.

Breathing patterns are closely associated with hot flashes. During sleep, a sigh generally occurs one minute before a hot flash as reported by Freedman and Woodward (1992). Women who habitually breathe thoracically (in the chest) report much more discomfort and hot flashes than women who habitually breathe diaphragmatically. Freedman, Woodward, Brown, Javaid, and Pandey (1995) and Freedman and Woodward (1992) found that hot flash rates during menopause decreased in women who practiced slower breathing for two weeks. In their studies, the control groups received alpha electroencephalographic feedback and did not benefit from a reduction of hot flashes. Those who received training in paced breathing reduced the frequency of their hot flashes by 50% when they practiced slower breathing. This data suggest that the slower breathing has a significant effect on the sympathetic and parasympathetic balance.

Women with PMS appear similarly able to reduce their discomfort. An early study utilizing Autogenic Training (AT) combined with an emphasis on warming the lower abdomen resulted in women noting improvement in dysfunctional bleeding (Luthe & Schultz, 1969, pp. 144-148). Using a similar approach, Mathew, Claghorn, Largen, and Dobbins (1979) and Dewit (1981) found that biofeedback temperature training was helpful in reducing PMS symptoms.. A later study by Goodale, Domar, and Benson (1990) found that women with severe PMS symptoms who practiced the relaxation response reported a 58% improvement in overall symptomatology as compared to a 27.2% improvement for the reading control group and a 17.0% improvement for the charting group.

Teaching control and achieving results

Teaching women to breathe effortlessly can lead to positive results and an enhanced sense of control. By effortless breathing, the authors refer to their approach to breath training, which involves a slow, comfortable respiration, larger volume of air exchange, and a reliance upon action of the muscles of the diaphragm rather than the chest (Peper, 1990). For more instructions see the recent blog, A breath of fresh air: Improve health with breathing.

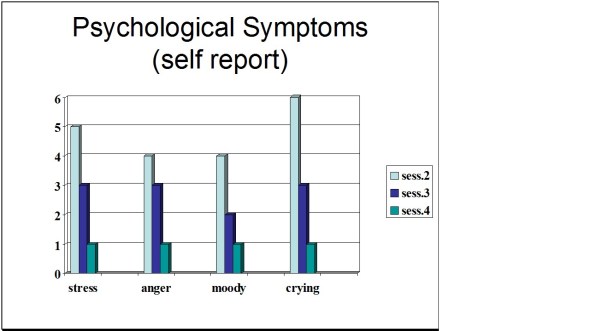

Slowing breathing helps to limit the sighs common to rapid thoracic breathing—sighs that often precede menopausal hot flashes. Effortless breathing is associated with stress reduction—stress and mood swings are common concerns of women suffering from PMS. In a pilot study Bier, Kazarian, Peper, and Gibney (2003) at San Francisco State University (SFSU) observed that when the subject practiced diaphragmatic breathing throughout the month, combined with Autogenic Training, her premenstrual psychological symptoms (anger, depressed mood, crying) and premenstrual responses to stressors were significantly reduced as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Student’s Individual Subjective Rating in Response to PMS Symptoms.

In another pilot study at SFSU, Frobish, Peper, and Gibney (2003) trained a volunteer who suffered from frequent hot flashes to breathe diaphragmatically. The training goals included modifying breathing patterns, producing a Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia (RSA), and peripheral hand warming. RSA refers to a pattern of slow, regular breathing during which variations in heart rate enter into a synchrony with the respiration. Each inspiration is accompanied by an increase in heart rate, and each expiration is accompanied by a decrease in heart rate (with some phase differences depending on the rate of breathing). The presence of the RSA pattern is an indication of optimal balance between sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous activity.

During the 11-day study period, the subject charted the occurrence of hot flashes and noted a significant decrease by day 5. However, on the evening of day 7 she sprained her ankle and experienced a dramatic increase in hot flashes on day 8. Once the subject recognized her stress response, she focused more on breathing and was able to reduce the flashes as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Subjective rating of intensity, frequency and bothersomeness of hot flashes. The increase in hot flashes coincided with increased frustration about an ankle injury.

Our clinical experience confirms the SFSU pilot studies and the previously referenced research by Freedman and Woodward (1992) and Freedman et al. (1995). When arousal is lowered and breathing is effortless, women are better able to cope with stress and report a reduction in symptoms. Habitual rapid thoracic breathing tends to increase arousal while slower breathing, especially slower exhalation, tends to relax and reduce arousal. Learning and then applying effortless breathing reduces excessive sympathetic arousal. It also interrupts the cycle of cognitive activation, anxiety, and somatic arousal. The anticipation and frustration at having hot flashes becomes the cue to shift attention and “breathe slower and lower.” This process stops the cognitively mediated self-activation.

Successful self-regulation and the return to health begin with cognitive reframing: We are not only a genetic biological fixed (deficient) structure but also a dynamic changing system in which all parts (thoughts, emotions, behavior, diet, stress, and physiology) affect and are effected by each other. Within this dynamic changing system, there is an opportunity to implement and practice behaviors and life patterns that promote health.

Learning Diaphragmatic Breathing with and without Biofeedback

Although there are many strategies to modify respiration, biofeedback monitoring combined with respiration training is very useful as it provides real-time feedback. Chest and abdominal movement are recorded with strain gauges and heart rate can be monitored either by an electrocardiogram (EKG) or by a photoplethysmograph sensor on a finger or thumb. Peripheral temperature and electrodermal activity (EDA) biofeedback are also helpful in training. The training focuses on teaching effortless diaphragmatic breathing and encouraging the participant to practice many times during the day, especially when becoming aware of the first sensations of discomfort.

Learning and integrating effortless diaphragmatic breathing into daily life is one of the biofeedback strategies that has been successfully used as a primary or adjunctive/complementary tool for the reversal of disorders such as hypertension, migraine headaches, repetitive strain injury, pain, asthma and anxiety (Schwartz & Andrasik, 2003), as well as hot flashes and PMS.

The biofeedback monitoring provides the trainer with a valuable tool to:

- Observe & identify: Dysfunctional rapid thoracic breathing patterns, especially in response to stressors, are clearly displayed in real-time feedback.

- Demonstrate & train: The physiological feedback display helps the person see that she is breathing rapidly and shallowly in her chest with episodic sighs. Coaching with feedback helps her to change her breathing pattern to one that promotes a more balanced homeostasis.

- Motivate, persuade and change beliefs: The person observes her breathing patterns change concurrently with a felt shift in physiology, such as a decrease in irritability, or an increase in peripheral temperature, or a reduction in the incidence of hot flushes. Thus, she has a confirmation of the importance of breathing diaphragmatically.

In addition, we suggest exercises that integrate verbal and kinesthetic instructions, such as the following: “Exhale gently,” and “Breathe down your leg with a partner.”

Exhale Gently:

Imagine that you are holding a baby. Now with your shoulders relaxed, inhale gently so that your abdomen widens. Then as you exhale, purse your lips and very gently and softly blow over the baby’s hair. Allow your abdomen to narrow when exhaling. Blow so softly that the baby’s hair barely moves. At the same time, imagine that you can allow your breath to flow down and through your legs. Continue imagining that you are gently blowing on the baby’s hair while feeling your breath flowing down your legs. Keep blowing very softly and continuously.

Practice exhaling like this the moment that you feel any sensation associated with hot flashes or PMS symptoms. Smile sweetly as you exhale.

Breathe Down Your Legs with a Partner

Sit or lie comfortably with your feet a shoulder width apart. As you exhale softly whisper the sound “Haaaaa….” Or, very gently press your tongue to your pallet and exhale while making a very soft hissing sound.

Have your partner touch the side of your thighs. As you exhale have your partner stroke down your thighs to your feet and beyond, stroking in rhythm with your exhalation. Do not rush. Apply gentle pressure with the stroking. Do this for four or five breaths.

Now, continue breathing as you imagine your breath flowing through your legs and out your feet.

During the day remember the feeling of your breath flowing downward through your legs and out your feet as you exhale.

Learning Strategies in Biofeedback Assisted Breath Training

Common learning strategies that are associated with the more successful amelioration of hot flashes and PMS include:

- Master effortless diaphragmatic breathing, and concurrently increase respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA). Instead of breathing rapidly, such as at 18 breaths per minute, the person learns to breathe effortlessly and slowly (about 6 to 8 breaths per minute). This slower breathing and increased RSA is an indication of sympathetic-parasympathetic balance as shown in Figure 3.

- Practice slow effortless diaphragmatic breathing many times during the day and, especially in response to stressors.

- Use the physical or emotional sensations of a hot flash or mood alteration as the cue to exhale, let go of anxiety, breathe diaphragmatically and relax.

- Reframe thoughts by accepting the physiological processes of menstruation or menopause, and refocus the mind on positive thoughts, and breathing rhythmically.

- Change one’s lifestyle and allow personal schedules to flow in better balance with individual, dynamic energy levels.

Figure 3. Physiological Recordings of a Participant with PMS. This subject learned effortless diaphragmatic breathing by the fifth session and experienced a significant decrease in symptoms.

Figure 3. Physiological Recordings of a Participant with PMS. This subject learned effortless diaphragmatic breathing by the fifth session and experienced a significant decrease in symptoms.

Generalizing skills and interrupting the pattern

The limits of self-regulation are unknown, often held back only by the practitioner’s and participant’s beliefs. Biofeedback is a powerful self-regulation tool for individuals to observe and modify their covert physiological reactions. Other skills that augment diaphragmatic breathing are Quieting Reflex (Stroebel, 1982), Autogenic Training (Schultz & Luthe, 1969), and mindfulness training (Kabat-Zinn, 1990). In all skill learning, generalization is a fundamental factor underlying successful training. Integrating the learned psychophysiological skills into daily life can significantly improve health—especially in anticipation of and response to stress. The anticipated stress can be a physical, cognitive or social trigger, or merely the felt onset of a symptom.

As the person learns and applies effortless breathing to daily activities, she becomes more aware of factors that affect her breathing. She also experiences an increased sense of control: She can now take action (a slow effortless breath) in moments when she previously felt powerless. The biofeedback-mastered skill interrupts the evoked frustrations and irritations associated with an embarrassing history of hot flashes or mood swings. Instead of continuing with the automatic self-talk, such as “Damn, I am getting hot, why doesn’t it just stop?” (language fueling sympathetic arousal), she can take a relaxing breath in response to the internal sensations, stop the escalating negative self-talk and allows more acceptance—a process reducing sympathetic arousal.

In summary, effortless breathing appears to be a non-invasive behavioral strategy to reduce hot flashes and PMS symptoms. Practicing effortless diaphragmatic breathing contributes to a sense of control, supports a healthier homeostasis, reduces symptoms, and avoids the negative drug side effects. We strongly recommend that effortless diaphragmatic breathing be taught as the first step to reduce hot flashes and PMS symptoms.

I feel so much cooler. I can’t believe that my hand temperature went up. I actually feel calmer and can’t even feel the threat of a hot flash. Maybe this breathing does work! –Menopausal patient after initial training in diaphragmatic breathing

References

Bier, M., Kazarian, D., Peper, E., & Gibney, K. (2003). Reducing the severity of PMS symptoms with diaphragmatic breathing, autogenic training and biofeedback. Unpublished report.

Freedman, R.R., & Woodward, S. (1992). Behavioral treatment of menopausal hot flushes: Evaluation by ambulatory monitoring. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 167 (2), 436-439.

Freedman, R.R., Woodward, S., Brown, B., Javaid, J.I., & Pandey, G.N. (1995). Biochemical and thermoregulatory effects of behavioral treatment for menopausal hot flashes. Menopause: The Journal of the North American Menopause Society, 2 (4), 211-218.

Frobish,C., Peper, E. & Gibney, K. H. (2003). Menopausal Hot Flashes: A Self-Regulation Case Study. Poster presentation at the 35th Annual Meeting of the Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. Abstract in: Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. 29 (4), 302.

Goodale, I.L., Domar, A.D., & Benson, H. (1990). Alleviation of Premenstrual Syndrome symptoms with the relaxation response. Obstetrics and Gynecological Journal, 75 (5), 649-55.

Hays, J., Ockene, J.K., Brunner, R.L., Kotchen, J.M., Manson, J.E., Patterson, R.E., Aragaki, A.K., Shumaker, S.A., Brzyski, R.G., LaCroix, A.Z., Granek, I.A, & Valanis, B.G., Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. (2003). Effects of estrogen plus progestin on health-related quality of life. New England Journal of Medicine, 348, 1839-1854.

Humphries, K.H.., & Gill, s. (2003). Risks and benefits of hormone replacement therapy: the evidence speaks. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 168(8), 1001-10.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living. New York: Delacorte Press.

Luthe, W. & Schultz, J.H. (1969). Autogenic therapy: Vol II: Medical applications. New York: Grune & Stratton.

Mathew, R.J.; Claghorn, J.L.; Largen, J.W.; & Dobbins, K. (1979). Skin Temperature control for premenstrual tension syndrome:A pilot study. American Journal of Clinical Biofeedback, 2 (1), 7-10.

Peper, E. (1990). Breathing for health. Montreal: Thought Technology Ltd.

Schultz, J.H., & Luthe, W. (1969). Autogenic therapy: Vol 1. Autogenic methods. New York: Grune and Stratton.

Schwartz, M.S. & Andrasik, F.(2003). Biofeedback: A practitioner’s guide, 3nd edition. New York: Guilford Press.

Shumaker, S.A., Legault, C., Thal, L., Wallace, R.B., Ockene, J., Hendrix, S., Jones III, B., Assaf, A.R., Jackson, R. D., Morley Kotchen, J., Wassertheil-Smoller, S.; & Wactawski-Wende, J. (2003). Estrogen plus progestin and the incidence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in post menopausal women: The Women’s Health Initiative memory study: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 289 (20), 2651-2662.

Stearns, V., Beebe, K. L., Iyengar, M., & Dube, E. (2003). Paroxetine controlled release in the treatment of menopausal hot flashes. Journal of the American Medical Association, 289 (21), 2827-2834.

Stroebel, C. F. (1982). QR, the quieting reflex. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons.

van Dixhoorn, J.J. (1998). Ontspanningsinstructie Principes en Oefeningen (Respiration instructions: Principles and exercises). Maarssen, Netherlands: Elsevier/Bunge.

Wassertheil-Smoller, S., Hendrix, S., Limacher, M., Heiss, G., Kooperberg, C., Baird, A., Kotchen, T., Curb, Dv., Black, H., Rossouw, J.E., Aragaki, A., Safford, M., Stein, E., Laowattana, S., & Mysiw, W.J. (2003). Effect of estrogen plus progestin on stroke in postmenopausal women: The Women’s Health Initiative: A randomized trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 289 (20), 2673-2684.

Wyeth Pharmaceuticals (2003, June 4). A message from Wyeth: Recent reports on hormone therapy and where we stand today. San Francisco Chronicle, A11.

*We thank Candy Frobish, Mary Bier and Dalainya Kazarian for their helpful contributions to this research.

**For communications contact: Erik Peper, Ph.D., Institute for Holistic Healing Studies, San Francisco State University, 1600 Holloway Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94132; Tel: (415) 338 7683; Email: epeper@sfsu.edu; website: http://www.biofeedbackhealth.org; blog: http://www.peperperspective.come

A historical perspective of neurofeedback: Video interview by Larrry Berkelhammer of Erik Peper

Posted: January 18, 2015 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: biofeedback, cancer, electroencephalography, health, neurofeedback, self-regulation 1 CommentDr. Erik Peper is interviewed by Dr. Larry Berkelhammer about the research he did in the late 60s and early 70s on EEG alpha training. He describes how he learned to turn off alpha brain rhythms in one hemisphere and turn them on in the other.

Neurofeedback equipment allows researchers and clinicians to get extremely useful feedback, allowing people who are hooked up to get very good at identifying their own brain rhythms and to alter them at will. This can potentially allow us to re-train our brains. Dr. Peper talks about how the real gift of science is about being open to explore rather than to assume our beliefs are factual. Science is about curiosity, experimentation, and exploration. In studying people with cancer and other diseases it is vital that we study more than just pathology–we need to study those individuals who are the outliers, that is, those who recovered against all odds–let’s see what they did to mobilize their health.

Go for it: The journey from paraplegia to flying

Posted: November 30, 2014 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: biofeedback, depression, exercise, healing, hope, human potential, illness beliefs, paraplegia 2 CommentsAfter a catastrophic event occurs a person often becomes depressed as the future looks bleak. One may keep asking, ”Why, why me?” When people accept–acceptance without resignation— and concentrate on the small steps of the journey towards their goal, remarkable changes may occur. The challenge is to focus on new possibilities without comparing to how it was in the past. The limits of possibility are created by the limits of our beliefs. We may learn from athletes who aim to improve performance whereas clients usually come to reduce symptoms. As Wilson and Peper (2011) point out, “Athletes want to go beyond normal—they want to be superb, to be atypical, to be the outlier. It is irrelevant what the athlete believes or feels. What is relevant is whether the performance is improved, which is a measurable and documented event”. They have described some of the factors that distinguish work with athletes from work with clients which includes intensive transfer of learning training, often between 2 and 6 hours of daily practice across days, weeks, and months. This process is described by the Australian cross-country skier, Janine Shepherd, who had hoped for an Olympic medal — until she was hit by a truck during a training bike ride. She shares a powerful story about the human potential for recovery. Her message: You are not your body, and giving up old dreams can allow new ones to soar. Watch Janine Shepherd’s 2012 Ted talk, A broken body isn’t a broken person.

Reference:

Wilson, V.E. & Peper, E. (2011). Athletes Are Different: Factors That Differentiate Biofeedback/Neurofeedback for Sport Versus Clinical Practice. Biofeedback, 39(1), 27–30.

Shepherd, J. (2012). A broken body isn’t a broken person. Ted talk. http://www.ted.com/talks/janine_shepherd_a_broken_body_isn_t_a_broken_person

Making the Unaware Aware*

Posted: April 27, 2014 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: awareness, biofeedback, mind-body, muscle tension, posture, relaxation 2 Comments“You only have to think to lift the hand and the muscles react.”

“I did not realize that muscle tension occurred without visible movement.”

“I was shocked that I was unaware of my muscle activity—The EMG went up before I felt anything.”

“Just anticipating the thought of the lifting of my hand increased the EMG numbers.”

“After training I could feel the muscle tension and it was one third lower than before I started.”

-Workshop participants after working with SEMG feedback

Many people are totally unaware that they are tightening their muscles and continuously holding slight tension until they experience stiffness or pain. This covert low-level muscle tension can occur in any muscle and has been labeled dysponesis, namely, misplaced and misdirected efforts (from the Greek: dys = bad; ponos = effort, work, or energy) (Whatmore & Kohli, 1974; Harvey & Peper, 2012). This chronic covert tension is a significant contributor to numerous disorders that range from neck, shoulder, and back pain to headaches and exhaustion and can easily be observed in people working at the computer.

While mousing and during data entry, most people are unaware that they are slightly tightening their shoulder muscles. One can often see this low level chronic tension when a person continuously lifts an index finger in anticipation of clicking the mouse or bends the wrist and lifts the fingers away from the keyboard while mousing with the other hand as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Lifting the hand without any awareness while mousing with the other hand (from Peper et al, 2014)

People may hold a position for a long time without being aware that they are contracting their muscles. They are focusing on their task performance. They are “captured by the screen” – until discomfort and pain occur. Only after they experience discomfort or pain, do they change position. Factors that contribute to this apparent lack of somatic awareness include:

- Being captured by the task. People are so focused upon performing a task that they are unaware of their dysfunctional body position, which eventually will cause discomfort.

- Institutionalized powerlessness. People accept the external environment as unchangeable. They cannot conceive new options and do not attempt to adjust the environment to fit it to themselves.

- Lack of somatic awareness and training. People are unaware of their own low levels of somatic and muscle tension.

Being Captured By the Task

People often want to perform a task well and they focus their attention upon correctly performing the task. They forget to check whether their body position is optimized for the task. Only after the body position becomes uncomfortable and interferes with task performance, do they become aware. At this point, the discomfort has often transformed into pain or illness.

This process of immediately focusing on task performance is easily observed when people are assigned to perform a new task. For example, you can ask people who are sitting in chairs arranged by row to form discussion groups to share information with the individuals in front or behind them. Some will physically lift and rotate their chair to be comfortable, while others will rotate their body without awareness that this twisted position increases physical discomfort. As instructors, we often photograph the participants as they are performing their tasks as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Workshop participants rotating their bodies or chairs to perform the group exercise (from Peper et al, 2014).

Although there are many strategies to teach participants awareness of covert tension, our recent published article, Making the Unaware Aware-Surface Electromyography to Unmask Tension and Teach Awareness,describes a simple biofeedback approach to teach awareness and control of residual muscle contraction. Almost all the subjects can rapidly learn to increase their recognition of minimal muscle tension as shown in figure 3.

Figure 3. Measurement of forearm extensor muscle awareness of minimum muscle tension before and after feedback training (from Peper et al, 2014).

Figure 3. Measurement of forearm extensor muscle awareness of minimum muscle tension before and after feedback training (from Peper et al, 2014).

This study showed that participants were initially unaware of covert tension and that they could quickly learn to increase their sensitivity of muscle tension and reduce this tension within a short time period. Surface electromyograpy (SEMG) provides an objective (third person) perspective of what is actually occurring inside the body and is more accurate than a person’s own perception (first person perspective). The SEMG feedback (numbers and graphs) learning experience was a powerful tool to shift participants’ illness beliefs and encourage them to actively participate in their own self-improvement. It demonstrated that: 1) they were unaware of low tension levels, and 2) they could learn to increase their awareness with SEMG feedback.

The participants became aware that covert tension could contribute to their discomfort and would inhibit regeneration. In some cases, they observed that merely anticipating the task caused an increase in muscle tension. Finally, they realized that if they could be aware during the day of the covert tension, they could identify the situation that triggered the response and also lower the muscle tension.

For detailed methodology and clinical application, see the published article, Peper,E., Booiman, A., Lin, I-M., & Shaffer, F. (2014). Making the Unaware Aware-Surface Electromyography to Unmask Tension and Teach Awareness. Biofeedback, 42(1), 16-23.

References:

Harvey, E. & Peper, E. (2012). I thought I was relaxed: The use of SEMG biofeedback for training awareness and control. In W. A. Edmonds, & G. Tenenbaum (Eds.),Case studiesin applied psychophysiology: Neurofeedback and biofeedback treatments foradvances inhuman performance. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 144-159.

There is Hope! Interrupt Chained Behavior

Posted: December 28, 2013 Filed under: self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: biofeedback, biofeedback breathing, posture, psoriasis, self-talk, stress management 4 Comments“I was able to self-heal myself. I didn’t need anyone else to do it for me.”

“I was surprised that I actually succeeded and had some really great results.”

“How much control I really had over being able to change several of my habits, when I previously thought that it was impossible.”

“That I actually have control.”

Students who have practiced stress management at SFSU

This blog summarizes our recent published article that describes a teaching healing approach that can be used by many clients to mobilize their health. The process is illustrated by a case report student who had suffered from psoriasis for more than five years totally cleared his skin in six weeks and has continued to this benefit (Klein & Peper, 2013). At the recent one year follow-up his skin is still clear.

Low energy, being tired and depressed, having pain, insomnia, itching skin, psoriasis, nervously pulling out hair, hypertension and other are symptoms that affects our lives. In many cases there is no identifiable biological cause. Currently, 74% of patients who visit their health care providers have undiagnosed medical conditions. Most of the symptoms are a culmination of stress, anxiety, and depression. In many cases, health care professionals treat these patients ineffectively with medications instead of offering stress management options. For example, if patients with insomnia visits their physicians, they are most likely prescribed a sleep inducing medication (hypnotics). Patients who take sleeping medication nightly have a fourfold increase in mortality (Kripke et al., 2012). If on the other hand if the healthcare professional takes time to talk to the patient and explores the factors that contribute to the insomnia and teach sleep hygiene methods, 50s% fewer prescriptions are written. Obviously, you may not be able to sleep if you are worried about money, job security, struggles with your partner or problems with your children; however, medication do not solve these problems. Learning problem solving and stress management techniques often does!

When students begin to learn these stress management and self-healing skills as part of a semester long Holistic Health Class at San Francisco State University, 82% reported improvement in achieving benefits such as increasing physical fitness, healthier diets, reducing depression, anxiety, pain and eliminating eczema or reducing hair pulling (one student with Trichotillomania reduced her hair pulling from 855 to 19 minutes per week) (Peper et al., 2003; Bier et al., 2005; Ratkovich et al., 2012). The major factors that contributed to the students’ improvement are:

- Daily monitoring of subjective and objective experiences to facilitates awareness and identify cues that trigger or aggravate the symptoms.

- Ongoing practicing during the day and during activities of the stress management skills as adapted from the book, Make Health Happen (Peper et al, 2003)

- Sharing subjective experiences in small groups which reduces social isolation, normalizes experiences, and encourages hope. Usually, a few students will report rapid benefits such as aborting a headache, falling asleep rapidly, or reducing menstrual cramps, which helps motivate other students to continue their practices.

- Writing an integrative summary paper, which provides a structure to see how emotions, daily practices and change in symptoms are related.

The first step is usually Identifying the trigger that initiates the illness producing patterns. Once identified, the next step is to interrupt the pattern and do something different. This can include transforming internal dialogue, practicing relaxation or modifying body posture. The mental/emotional and physical practices interrupts and diverts the cascading steps that develop the symptoms (Peper et al., 2003).

Interrupting and transforming the chained behavior is illustrated in our article “There Is Hope: Autogenic Biofeedback Training for the Treatment of Psoriasis” published in the recent issue of Biofeedback. We report on the process by which a 23-year-student totally cleared his skin after having had psoriasis for the last five years. Psoriasis causes red, flaky skin and is currently the most common autoimmune disease affecting approximately 2% of the US population. Many people afflicted with this disease use steroids, topical creams, special shampoos, and prescription medication. Unfortunately, the disease can only be suppressed, not cured. Thus many people with psoriasis feel damaged and have a difficult time socially. Stress is often one of the triggers that makes psoriasis worse. In this case study, the 23-year-old student learned how to train his mind/body to transform his feelings of stress, anxiety, self-doubt, and urge to scratch his skin into a positive self-healing process.

Initially, the student was trained in stress management and biofeedback techniques that included relaxation, stress reduction, and desensitization. He learned how to increase his confidence by changing his body posture while sitting and standing. He also took time to stop and refocus his energy when he felt the need to fall back into old habits. What did he really do?

The moment he became aware of skin sensations, he would:

- Stop, take a deep breath into his abdomen and slowly exhale

- Assess how he was thinking-having negative and hopeless thoughts

- Change the negative thoughts into positive affirmative thoughts

- Breathe deeply

- Imagine as he exhaled feeling heaviness and warmth in his arms and feet

- Talk to his body by saying, “My skin is cool, clear, and regenerative.” “I am worthy.”

To become aware of his automatic negative behavior was very challenging. He had to stop focusing on the task in front of him and to put all of his energy into regaining his composure. This is very difficult because people are normally captured by whatever they are doing at that moment. As he stated: “Breaking this chain behavior was by far the hardest things I’ve ever done. It didn’t matter what situation I found myself in, my practice took precedence. The level of self- control I had to maintain was far beyond my norm. I remember taking an exam. I was struggling to recall the answer to the last essay question. All I wanted to do was finish the exam and go home. I knew that I knew it, it was coming to me, I began to write… Yet in that same moment I felt my right elbow start to tingle (the location of one of the psoriasis plagues) and my left hand started to drift towards it. Immediately I had to switch my focus. Despite my desire to finish I dropped my pen. I paused to breathe and focused upon my positive thoughts. Moments like this happened daily, my normal functions were routinely interrupted by urges to scratch. Sometimes I would spend significantly more time doing the practices than the task at hand.

Similarly, whenever he observed his body posture “collapsing” and “hiding” — thus falling into a more powerless posture — he would interrupt the collapse and shift to a power position by expanding and being more erect. He did this while standing, sitting, and talking to other students. As he stated: “I hadn’t realized how my collapsing posture was effecting my self-image until I began practicing a more powerful posture. In class I made myself sit with my butt pushed back against the back of the chair instead of letting myself slide forwarding into a slouch. Just like the urge to itch I had to stay conscious of my posture constantly. At work, at school, even at home on the couch I practiced expanding body posture. The more I was aware of my posture the better my posture became, and the more time I spent in power pose the more natural it began to feel. The more natural it felt the more powerful I felt.”

After three weeks, his skin had cleared and has continued to stay this way for the last year as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Pre and post photos of the elbow and knee showing the improvement of the skin.

Figure 1. Pre and post photos of the elbow and knee showing the improvement of the skin.

There are many diseases and ailments that require the use of medication for appropriate treatment, but when stress is a factor in any diagnosis, or when a diagnosis cannot be found, it is important for stress management to be offered as a viable option for patients to consider. As shown by the student with psoriasis, learning stress management skills and then actually practicing them during the day can play a major factor in improving the health of an individual. The same process is applicable for numerous symptoms. There is hope=-Just do it.

References:

Bier, M., Peper, E., & Burke, A. (2005). Integrated stress management with ‘Make Health Happen: Measuring the impact through a 5-month follow-up. Presented at the 36th Annual Meeting of the Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. Abstract published in: Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 30(4), 400. http://biofeedbackhealth.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/2005-aapb-make-health-happen-bier-peper-burke-gibney3-12-05-rev.pdf

Klein, A. & Peper, W. (2013). There is Hope: Autogenic Biofeedback Training for the Treatment of Psoriasis. Biofeedback, 41(4), 194–201. http://biofeedbackhealth.files.wordpress.com/2011/01/published-article-there-is-hope.pdf

Kripke, D.F., Langer, R.D., Kline. L.E. (2012). Hypnotics’association with mortality or cancer: a matched cohort study. BMJOpen, 2:e000850. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000850 http://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/2/1/e000850.full.pdf+html

Peper, E., Gibney, K.H. & Holt. C. (2002). Make Health Happen: Training Yourself to Create Wellness. Dubuque, IA: Kendall-Hunt. http://www.amazon.com/Make-Health-Happen-Training-Yourself/dp/0787293318

Peper, E., Sato-Perry, K & Gibney, K. H. (2003). Achieving health: A 14-session structured stress management program—Eczema as a case illustration. 34rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. Abstract in: Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 28(4), 308. http://biofeedbackhealth.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/2003-aapb-poster-peper-keiko-long1.pdf

Ratkovich, A., Fletcher, L., Peper, E., & Harvey, R. (2012). Improving College Students’ Health-Including Stopping Smoking and Healing Eczema. Presented at the 43st Annual Meeting of the Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. Baltimore, MD. http://biofeedbackhealth.files.wordpress.com/2011/01/2012-improving-college-student-health-2012-02-28.pdf

Mind-Guided Body Scans for Awareness and Healing–Youtube Interview of Erik Peper, PhD by Larry Berkelhammer, PhD

Posted: December 23, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: biofeedback, body scan, body sensations, healing, Imagery, meditation, mind-body, passive attention, visualization 2 CommentsIn this interview psychophysiology expert Dr. Erik Peper explains the ways how a body scan can facilitate awareness and healing. The discussion describes how the mind-guided body scan can be used to improve immune function and hold passive attention (mindfulness) to become centered. It explores the process of passive attentive process that is part of Autogenic Training and self-healing mental imagery. Mind-guided body scanning involves effortlessly observing and attending to body sensations through which we can observe our own physiological processes. Body scanning can be combined with imagery to be in a nonjudgmental state that supports self-healing and improves physiological functioning.

Focus On Possibilities, Not On Limitations. Youtube interviews of Erik Peper, PhD, by Larry Berkelhammer, PhD

Posted: March 18, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: biofeedback, mind-body, pain, relaxation, shoulder pain, yoga Leave a commentFocus On Possibilities, Not On Limitations

This interview with psychophysiologist Dr. Erik Peper reveals self-healing secrets used by yogis for thousands of years. Mind-training methods used by yogis like Jack Schwarz were explored. The underlying message throughout the discussion was that suffering and even actual tissue damage are profoundly influenced by both our negative and our positive attributions. The methods by which yogis have learned to self-heal is available to all of us who are willing to assiduously adopt a daily practice. It is very clear that when our attention goes to our pain or other symptoms, our suffering and even tissue damage worsens. When we focus all our attention on what we want rather than on what we are afraid of, we achieve a healthier, more positive, and more robust level of healing. We suffer when we have negative expectancies and we reduce suffering when we focus our attention on positive expectancies. We can train the mind to fully experience sensations without negative attributions. For the vast majority of us, we have far greater potential than we believe we have. Biofeedback, concentration practices, mindfulness practices, and other yogic practices allow us to condition ourselves to concentrate on the present moment, rather than on our negative expectancies, limitations, attributions, and fears.

Belief Becomes Biology

Dr. Larry Berkelhammer speaks with Dr. Erik Peper about the connection of our beliefs and our health.

Epilepsy: New (old) treatment without drugs

Posted: March 10, 2013 Filed under: Nutrition/diet, self-healing, Uncategorized | Tags: biofeedback, diet, ketogenic diet, neurofeedback 11 CommentsNothing is so hard as watching a child having a seizure.

–Elizabeth A. Thiele, MD, PhD, professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School

Until recently, when people asked me, “What would I suggest as a non-toxic/non-invasive biofeedback approach for the treatment of epilepsy?” I automatically replied, “A combination of neurofeedback, behavioral analysis treatment, respiration training, a low glycemic diet, and stress management and if these did not work, medications.” I have now changed my mind!

Epilepsy is diagnosed if the person has two or more seizures. About one to two percent of the population is diagnosed with epilepsy and it is the most common neurological illness in children. Medication is usually the initial treatment intervention; however, in about one third of the people, the seizures will still occur despite the medications. In some cases, people -often without the support of their neurologist/healthcare provider–will explore other treatment strategies such as diet, respiration training, neurofeedback, behavioral control, diet, or traditional Chinese medicine.

It is ironic that one of the tools to diagnose epilepsy is recording the electroencephalography (EEG)– brain waves–of the person after fasting while breathing quickly (hyperventilating). For some, the combination of low blood sugar and hyperventilation will evoke epileptic wave forms in their EEG and can trigger seizures (hyperventilation when paired with low sugar levels tends to increase slow wave EEG which would promote seizure activity).

If hyperventilation and fluctuating blood sugar levels are contributing factors in triggering seizures, why not teach breathing control and diet control as the first non-toxic clinical intervention before medications are prescribed. This breathing approach has shown very promising clinical success. (For more details see the book, Fried, R. (1987). The Hyperventilation syndrome-Research and Clinical Treatment. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press).

Self-management should be the first clinical intervention and not the last. Similarly, neurofeedback– brain wave biofeedback–is another proven approach to reduce seizures. This approach was developed by Professor Maurice B. Sterman at UCLA and was based upon animal studies. He demonstrated that cats who were trained to increase sensory motor rhythm (SMR) in their EEG could postpone seizure onset when exposed to a neurotoxin that induced seizures. He then demonstrated that human beings with epilepsy could equally learn to control their EEG patterns and inhibit seizures. This approach, just as the breathing approach, is non-toxic and reduces seizures.

Underlying both these approaches is the concept of behavioral analysis to identify and interrupt the chained behavior that leads to a seizure. Namely, a stimulus (internal or external) triggers a cascading chain of neurological processes that eventually results in a seizure. Thus, if the person learns to identify and interrupt/divert this cascading chain, the seizure does not occur. From this perspective, respiration training and neurofeedback could be interpreted to interrupt this cascading process. Behavioral analyses includes all behaviors (movement, facial expressions, emotions, etc) which can be identified and then interrupted. As professors Joanne Dahl and Tobias Lundgren from Uppsala University in Sweden state, The behavior technology of seizure control provides low-cost, drug free treatment alternative for individual already suffering from seizures and the stigmatization of epilepsy.

Until recently, I would automatically suggest that people explore these self-control strategies as the first intervention in treatment of epilepsy and only medication for the last resort. Now, I have changed my mind. I suggest the ketogenic diet as the first step for the treatment of epilepsy in conjunction with the self-regulation strategies—medication should only be used if the previous strategies were unsuccessful.

A ketogenic diet has a 90% clinical success rates in children–even in patients with refractory seizures. This diet stabilizes blood sugar levels and is very low on simple carbohydrates, high in fat, some protein, and lots of vegetables (a ratio of 4 grams of fat to 1 gram of carbohydrates and protein). In adults, the success rates drops to about 50%. The lower success rate may be the result of the challenges in implementing these self-regulatory diet approaches. As Elizabeth A. Thiele, MD, PhD, professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School points out, dietary therapy is the most effective known treatment strategy for epilepsy. Even though, ketogenic diet is the most effective therapy, it is less likely to be prescribed than medications—there are no financial incentives; there are, however, many financial incentives for prescribing pharmaceuticals.

These lifestyle changes are very challenging to implement. They need to be taught and socially supported. Just telling people what to do does not often work. It is similar to learning to play a musical instrument. The person needs step by step coaching and social support which is an intensive educational approach. To learn more about the research underlying the ketogenic diet as the first level of intervention for epilepsy, watch Professor Thiele’s presentation from the 2012 Ancentral Health Symposium, Dietary Therapy: Role in Epilepsy and Beyond.

Change Illness Beliefs with Words, Biofeedback, and Somatic Feedback*

Posted: January 2, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: biofeedback, cancer, illness beliefs, mind-body 8 CommentsI never felt that thinking about my work affected my body. I was totally surprised to see my body’s reaction on the computer screen. I now realized how I contributed to my illness and could see other ways to change and improve my health. The feedback made the invisible visible, the undocumented documented.

Use of words, biofeedback and somatic feedback to transform illness beliefs. Many clients are unaware how much their thoughts and emotions affect their physiology. The numbers and graphs on the computer screen show how the body is responding. Seeing the changes in the physiological recording and the immediate feedback signals are usually accepted by the client as evidence, whereas the verbal comments made by a therapist might be denied as the therapist’s subjective opinion. The feedback is experienced as objective data—numbers and graphs ‘‘do not lie’’—which represents truth to the client. Clients seek biofeedback therapy because they believe the cause of illness is in their body, and then the biofeedback may demonstrate that emotions and cognitions influence their somatic illness patterns. This process has been labeled by Ian Wickramasekera (2003) as a ‘‘Trojan Horse’’ approach. Biofeedback and somatic feedback exercises provide effective tools for changing illness attributions and awaken the client to the impact of thoughts and emotions on physiology. Whether the feedback comes from a biofeedback device that records the covert physiological signal or is subjectively experienced through a somatic exercise, the self-experience is a powerful trigger for an ‘‘aha’’ experience—a realization that mind, body, and emotions are not separate (Wilson, Peper, & Gibney, 2004). Clinically, this approach can be used to facilitate changing illness beliefs and to motivate clients to begin changing their cognitive, emotional, and behavioral patterns. Clients begin to realize that they can be active participants in the healing process and that in many cases it is their mind-body life patterns that contribute to illness or health. For more information, case example and detailed description of a somatic feedback practice, download a pre-publication of our article, The Power of Words, Biofeedback, and Somatic Feedback to Impact Illness Beliefs.

*Adapted from: Peper, E., Shumay, D.M., & Moss, D. (2012). Change Illness Beliefs with Biofeedback and Somatic Feedback. Biofeedback. 40(4), 154–159.

Biofeedback and pain control. Two YouTube interviews of Erik Peper, PhD by Larry Berkelhammer, PhD

Posted: October 12, 2012 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: asthma, biofeedback, hope, pain, self-regulation, stress, stress management 1 CommentErik Peper, Biofeedback Builds Self-efficacy, Hope, Health, & Well-being

Interview with biofeedback pioneer Dr. Erik Peper on how biofeedback builds self-efficacy, hope, health and well-being. How to use the mind to improve physiological functioning and health. Skill-building to develop self-efficacy, self-empowerment, and hope. Evidence-based mental training to manage symptoms, self-regulate blood pressure, chronic pain & fatigue, cardiac dysrhythmias, digestion, and many other bodily processes.

Erik Peper, Pain Control Through Relaxation

This interview of Dr. Erik Peper explores the frontier of psychophysiological self-regulation. Included is conscious regulation of pain, blood pressure, and other physiological measures. We discuss how you can take control and consciously calm your sympathetic nervous system in order to attenuate pain. Autogenic Training, yogic disciplines, biofeedback, and other methods are mentioned as ways to use the mind to gain conscious control of cognitive, emotional, and physiological processes. For example, when we experience sudden pain, we automatically brace against it in the hope of resisting it. Paradoxically, this increases suffering. Autogenic Training and many other disciplines provide us with the skills to relax into any painful stimulus. Although it seems counterintuitive, learning to fully accept and relax into the pain allows us to take control over the pain, whereas trying to control it serves to increase the suffering. Another concept that is discussed in this video is that we can reduce pain and speed healing by extending loving self-care to any injury.