Hope for teens with pain

Posted: August 31, 2019 Filed under: behavior, health, Pain/discomfort, relaxation, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: adolescents, teenagers 3 CommentsErik Peper, PhD and Rachel Zoffness, PhD*

KM was 14 years old when he came to my (Zoffness) office for treatment. He’d been diagnosed with migraine and cyclical vomiting syndrome and had been in bed for about 3 years. He had long, unwashed hair; was a sickly, pasty white; and rocked himself back and forth from the pain. He’d seen 15 doctors and had been prescribed 30 medications, including occipital nerve injections and Thorazine. Nothing had worked. Like most teens with chronic pain, KM was depressed, stressed, and terrified he’d never get his life back.

We started Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), beginning with pain neuroscience education. This involved teaching KM and his family how pain works in the brain, and how thoughts, emotions, physical sensations and behaviors work together to trigger and maintain flares. He then learned a variety of cognitive, behavioral and mind-body techniques to help manage and change pain. His parents received parent-training to support him behind the scenes. After a few weeks of treatment, KM was able to get out of bed and walk to the corner mailbox. After a few more weeks, he was able to walk his dog to the dog park and get a haircut. Within a few months he was jogging around the block, then running. As his functioning increased, his brain desensitized and his body strengthened, his pain started to recede. Gradually he returned to school and social relationships, eventually rejoining his soccer team. I attended his high school graduation a year ago. He got onstage and told the audience that, if you’d told him 4 years ago that he’d graduate high school, he’d never have believed you. He is currently in college, successfully managing his pain, living his important life.

Chronic pain (CP) in teens can be devastating. Teens are already tasked with managing the turbulence of hormone changes, social stress, academic stress, social media, family dynamics, and developing autonomy and independence. CP impacts not only the teen, but also the entire family. Because CP is framed as a biomedical problem, it is frequently treated with opioids and other minimally-helpful (and sometimes harmful) medications. Opioids are ineffective for long-term treatment of chronic pain, and are only useful in acute crises or to control pain at the end of life (Dowell, 2016; King et al, 2011).

Although we typically think of chronic pain as an issue primarily affecting adults coping with issues such as post-surgical pain and arthritis, CP affects up to 1 in 3 youth in the USA – more than 10 million children and teens (Friedrichsdorf, 2016; ). Pain impacts self-esteem, hope, and functioning, relegating teens to their beds and denying them normal educations and healthy social interactions. Like adults, teens often feel powerless and blamed. In a superb workbook, The Chronic Pain & Illness Workbook for Teens, psychologist Rachel Zoffness describes what pain is; how pain is constructed by the brain; how mind, body and emotions interact to affect pain; and offers a sequence of assessments and practices to reduce pain and improve health in language children and teens can easily understand. The approach combines cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) with imagery, mindfulness, breathing, handwarming with biofeedback, and somatic practices (Turk & Gatchel, 2018; Peper, Gibney, & Holt, 2002).

This simple graphic of the pain cycle is helpful to clients (see Fig. 1).

Fig 1. CBT Pain Cycle

The pragmatic practices in this book offer tools and guided instructions that any child or teen can use for themselves, with parents, or with health providers. Therapists can use and adapt these activities with their clients of all ages. Although these scientifically-supported pain management techniques are written for teens, they can equally be used with adults. Below are two of many different practices described in the book that are useful for chronic pain.

Practice 1: Assessment: What sets off your pain?

The first step is to help youth identify factors that “trigger” – or set off – their pain. It’s helpful to define a trigger as a difficult emotion, situation, or event that causes pain to increase. Difficult situations and events of all kinds – biological, social, etc (situational triggers) can trigger difficult thoughts and emotions (cognitive and emotional triggers), and vice versa. For example, Adam was recovering from back surgery (situational trigger), got into a big fight with his sister about the car (situational trigger), and became angry and frustrated (emotional trigger). He felt the anger in his body, his muscles got hot and tight, and his back started spasming. Gina is an example of the reverse. She believed that nothing could cure her fibromyalgia (cognitive trigger), which made her feel depressed and hopeless (emotional trigger). She stayed home for weeks on end without school, friends, or distractions (situational trigger), and started feeling worse.

We can help youth with pain by asking:

- What emotions trigger your pain?

- Frustration

- Anger

- Stress

- Anxiety

- Loneliness

- Sadness

- What situations trigger your pain?

- Not getting enough sleep

- Arguing with family members

- Inflammation after physical therapy

- Missing fun events because you’re sick

- Thinking about upcoming exams

- Doctor’s appointments and hospital visits

Sometimes, the teen needs to keep a log for a week to identify the situations or triggers related to the pain. Once these have been identified then the teen can explore strategies to reduce the negative reactivity triggered by the emotions or situations.

Practice 2: Changing the voice of pain (Note: this is a summary of a longer activity)

One technique we use in CBT for chronic pain is identifying and tracking cognitive distortions, also known as “thinking traps.” I (Zoffness) call these traps “Pain Voice.” This is the catastrophic, pessimistic, critical, and negative voice that tells us awful, worrisome things, particularly about our pain or health.

For example:

Pain Voice pretends she can predict the future, and says it’s going to be terrible. She says: “You’ll never get better. Nothing will ever help you.” But since she can’t predict the future (who can?), Pain Voice is a liar! Pain Voice is also very bossy about what you can and can’t do: “You can’t see your friends this week,” or “You can’t go for a bike ride, and you definitely can’t have any fun.” Science teaches us that negative thoughts increase pain by turning up the brain’s “pain dial,” so we must make sure not to listen to or believe them. To stop Pain Voice, we first catch negative thoughts.

As soon as you learn how to recognize Pain Voice, you gain the power to change negative thoughts into more helpful “Wise Voice” thoughts. One way to bust Pain Voice is to start tracking your negative thoughts. First, list these critical, self-defeating, catastrophic Pain Voice thoughts. Notice if they’re helpful or harmful. Then check and question them, thoughtfully determining whether they’re the truth or a trap. Next, gather evidence as to why Pain Voice might be wrong by asking yourself, is this thought a fact? What evidence do I have that this thought might not be true? What else might happen other than what I’m predicting? Write out your Wise Voice responses, and use them to fight back every time you hear Pain Voice!

Jason’s example: Jason had terrible, daily back pain and hadn’t gone outside in 6 weeks. His friends texted, inviting him to watch a movie. Immediately he heard the thought, “I can’t go, I’m broken. If I leave my house my pain will spike and I won’t be able to function.” He recognized this as his Pain Voice and knew he had to fight back. He sat down with his worksheet and filled in the answers: yes, the thoughts were harmful, not helpful, and they were trying to trap him! He examined the evidence and wrote the Wise Voice thought, “This negative prediction is not a fact, it’s a trap. I’ve had back pain for 2 years, and sometimes going out and seeing friends actually reduces my pain.” Tuning into his Wise Voice gave him the strength to get the social support and distraction he needed to feel a little better! He went to his friend’s house, watched movies, ate popcorn, giggled, and had a great time. For the first time in 6 weeks, his pain went down. An example of his log is shown in table 1.

|

Situation |

Pain Voice |

Helpful or Harmful? |

Trap or Truth |

Wise Voice |

| Returning to school after missing 3 weeks | If I go back to school, I’ll be so far behind that I won’t understand anything the teacher is talking about. | Harmful | Trap | This negative prediction is not a fact. I’m smart and competent, I’ll probably understand some things. Last time I was behind, I made up the work and everything was fine. |

|

Pain flare-up

|

I can’t handle this! | Harmful | Trap | This negative prediction is not a fact. I’ve had 42 pain flare-ups this year, and I handled all of them. I’ve proven that I’m strong and resilient. There is a 0% chance I can’t handle this. |

Table 1. Example from Jason’s log

Summary: There is hope for youth with chronic pain. Interventions like CBT, mindfulness, biofeedback and other mind-body approaches are scientifically-supported and have evidence of effectiveness. Adhering to the biopsychosocial model – targeting biological, psychological and social factors – is proven to be the most effective treatment for chronic pain across conditions and ages. For more information, see Rachel Zoffness’ book, The chronic pain & illness workbook for teens, for pragmatic treatment practices and user-friendly pain education.

References

*Dr. Rachel Zoffness is a pain psychologist, consultant, writer and educator in Northern California’s East Bay specializing in chronic pain and illness.

Do self-healing first

Posted: May 27, 2019 Filed under: behavior, Breathing/respiration, emotions, Exercise/movement, health, mindfulness, Neck and shoulder discomfort, Nutrition/diet, Pain/discomfort, placebo, relaxation, self-healing, stress management, surgery, Uncategorized 2 Comments

“I am doing very well, and I am very healthy. The vulvodynia symptoms have never come back. Also,my stomach (gastrointestinal discomfort) has gotten much, much better. I don’t really have random pain anymore, now I just have to be watchful and careful of my diet and my exercise, which are all great things!” —A five-year follow-up report from a 28-year-old woman who had previously suffered from severe vulvodynia (pelvic floor pain).

Numerous clients and students have reported that implementing self-healing strategies–common sense suggestions often known as “grandmother’s therapy”—significantly improves their health and find that their symptoms decreased or disappeared (Peper et al, 2014). These educational self-healing approaches are based upon a holistic perspective aimed to reduce physical, emotional and lifestyle patterns that interfere with healing and to increase those life patterns that support healing. This may mean learning diaphragmatic breathing, doing work that give you meaning and energy, alternating between excitation and regeneration, and living a life congruent with our evolutionary past.

If you experience discomfort/symptoms and worry about your health/well-being, do the following:

- See your health professional for diagnosis and treatment suggestions.

- Ask what are the benefits and risks of treatment.

- Ask what would happen if you if you first implemented self-healing strategies before beginning the recommended and sometimes invasive treatment?

- Investigate how you could be affecting your self-healing potential such as:

- Lack of sleep

- Too much sugar, processed foods, coffee, alcohol, etc.

- Lack of exercise

- Limited social support

- Ongoing anger, resentment, frustration, and worry

- Lack of hope and purpose

- Implement self-healing strategies and lifestyle changes to support your healing response. In many cases, you may experience positive changes within three weeks. Obviously, if you feel worse, stop and reassess. Keep a log and monitor what you do so that you can record changes.

This self-healing process has often been labeled or dismissed as the “placebo effect;” however, the placebo effect is the body’s natural self-healing response (Peper & Harvey, 2017). It is impressive that many people report feeling better when they take charge and become active participants in their own healing process. A process that empowers and supports hope and healing. When participants change their life patterns, they often feel better. Their health worries and concerns become reminders/cues to initiate positive action such as:

- Practicing self-healing techniques throughout the day (e.g., diaphragmatic breathing, self-healing imagery, meditation, and relaxation)

- Eating organic foods and eliminating processed foods

- Incorporating daily exercise and movement activities

- Accepting what is and resolving resentment, anger and fear

- Taking time to regenerate

- Resolving stress

- Focusing on what you like to do

- Be loving to yourself and others

For suggestions of what to do, explore some of the following blogs that describe self-healing practices that participants implemented to improve or eliminate their symptoms.

Acid reflux (GERD) https://peperperspective.com/2018/10/04/breathing-reduces-acid-reflux-and-dysmenorrhea-discomfort/

Dyspareunia https://peperperspective.com/2017/03/19/enjoy-sex-breathe-away-the-pain/

Epilepsy https://peperperspective.com/2013/03/10/epilepsy-new-old-treatment-without-drugs/

Irritability/hangry https://peperperspective.com/2017/10/06/are-you-out-of-control-and-reacting-in-anger-the-role-of-food-and-exercise/

Hot flashes and premenstrual symptoms https://peperperspective.com/2015/02/18/reduce-hot-flashes-and-premenstrual-symptoms-with-breathing/

Internet addiction https://peperperspective.com/2018/02/10/digital-addiction/

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) https://peperperspective.com/2017/06/23/healing-irritable-bowel-syndrome-with-diaphragmatic-breathing/

Math and test anxiety https://peperperspective.com/2018/07/03/do-better-in-math-dont-slouch-be-tall/

Neck stiffness https://peperperspective.com/2017/04/06/freeing-the-neck-and-shoulders/

Neck tension https://peperperspective.com/2019/05/21/relieve-and-prevent-neck-stiffness-and-pain/

Posture and mood https://peperperspective.com/2017/11/28/posture-and-mood-implications-and-applications-to-health-and-therapy/

Psoriasis https://peperperspective.com/2013/12/28/there-is-hope-interrupt-chained-behavior/

Surgery https://peperperspective.com/2018/03/18/surgery-hope-for-the-best-but-plan-for-the-worst/

Trichotillomania (hair pulling) https://peperperspective.com/2015/03/07/interrupt-chained-behaviors-overcome-smoking-eczema-and-hair-pulling/

Vulvodynia https://peperperspective.com/2015/09/25/resolving-pelvic-floor-pain-a-case-report/

References

Relieve and prevent neck stiffness and pain

Posted: May 21, 2019 Filed under: behavior, Exercise/movement, health, Neck and shoulder discomfort, Pain/discomfort, posture, Uncategorized | Tags: muscle tension, neck pain, neck stiffness, vision 6 CommentsIs your neck stiff, uncomfortable and painful?

When driving is it more difficult to turn your head?

Neck and shoulder pain affect more than 30% of people (Fejer et al, 2006; Cohen, 2015). This blog explores some strategies to reduce or prevent neck stiffness and discomfort and suggests practices to reduce discomfort and increase flexibility if you already are uncomfortable.

Shifts in posture may optimize neck flexibility

In our modern world, we frequently engage in a forward head position while looking at electronic devices or typing on computers. Prolonged smart phone usage has the potential to negatively impact posture and breathing functions (Jung et al., 2016) since we tilt our head down to look at the screen. Holding the head in a forward position, as displayed in Figure 1, can result in muscle tension in the spine, neck, and shoulders.

Fig 1. Forward head and neck posture in comparison to a neutral spine. Source: https://losethebackpain.com/conditions/forward-head-posture/

Fig 1. Forward head and neck posture in comparison to a neutral spine. Source: https://losethebackpain.com/conditions/forward-head-posture/

Whenever you bring your head forward to look at the screen or tilt it down to look at your cellphone, your neck and shoulder muscles tighten and your breathing pattern become more shallowly. The more the head is forward, the more difficulty is it to rotate your head as is describe in the blog, Head position, it matters! (Harvey et al, 2018). Over time, the head forward position may lead to symptoms such as headaches and backpain. On the other hand, when we shift to an aligned upright position throughout the day, we create an opportunity to relieve this tension as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. EMG and respiration recording from a subject sitting with a forward head position and a neutral, aligned head position. The neck and shoulder muscle tension was recorded from the right trapezius and left scalene muscles (Mason et all, unpublished). .

Figure 2. EMG and respiration recording from a subject sitting with a forward head position and a neutral, aligned head position. The neck and shoulder muscle tension was recorded from the right trapezius and left scalene muscles (Mason et all, unpublished). .

The muscle tension recorded from scalene and trapezius muscles (neck and shoulder) in Figure 2 shows that as the head goes forward or tilts down, the muscle tension significantly increases. In most cases participants are totally unware that their neck tightens. It is only after looking at the screen or focus our eyes until the whole day that we notice discomfort in the late afternoon.

Experience this covert muscle tension pattern in the following video, Sensing neck muscle tension-The eye, head, and neck connection.

Interrupt constant muscle tension

One possible reason why we develop the stiffness and discomfort is that we hold the muscles contracted for long time in static positions. If the muscle can relax frequently, it would significantly reduce the probability of developing discomfort. Experience this concept of interrupting tension practice by practicing the following:

- Sit on a chair and lift your right foot up one inch up from the floor. Keep holding it up? For some people, as soon as five seconds, they will experience tightening and the onset of discomfort and pain in the upper thigh and hip.

How long could you hold your foot slight up from the floor? Obviously, it depends on your motivation, but most people after one minute want to put the foot down as the discomfort become more intense. Put the foot down and relax. Notice the change is sensation and for some it takes a while for the discomfort to fade out.

- The reason for the discomfort is that the function of muscle is to move a joint and then relax. If tightening and relaxation occurs frequently, then there is no problem

- Repeat the same practice except lift the foot, relax and drop it down and repeat and repeat. Many people can easily do this for hours when walking.

What to do to prevent neck and shoulder stiffness.

Interrupt static muscle neck tension by moving your head neck and shoulder frequently while looking at the screen or performing tasks. Explore some of the following:

- Look away from the screen, take a breath and as you exhale, wiggle your head light heartedly as if there is a pencil at reaching from the top of your head to the ceiling and you are drawing random patterns on the ceiling. Keep breathing make the lines in all directions.

- Push the chair back from the desk, roll your right shoulder forward, up and back let it drop down and relax. Then roll you left shoulder forward up and back and drop down and relax. Again, be sure to keep breathing.

- Stand up and skip in place with your hands reaching to the ceiling so that when your right foot goes up you reach upward with your left hand toward the ceiling while looking at your left hand. Then, as your left foot goes up your reach upward to the ceiling with your right hand and look at your right hand. Smile as you are skipping in place.

- Install a break reminder program on your computer such as Stretch Break to remind you to stretch and move.

- Learn how to sit and stand aligned and how to use your body functionally such as with the Gokhale Method or the Alexander Technique (Gokhale, 2013; Peper et al, in press, Vineyard, 2007).

- Learn awareness and control neck and shoulder muscle tension with muscle biofeedback. For practitioners certified in biofeedback BCB, see https://certify.bcia.org/4dcgi/resctr/search.html

- Become aware of your collapsed and slouching wearing a posture feedback device such as UpRight Go on your upper back. This device provides vibratory feedback every time you slouch and reminds you to interrupt slouching and be upright and alighned.

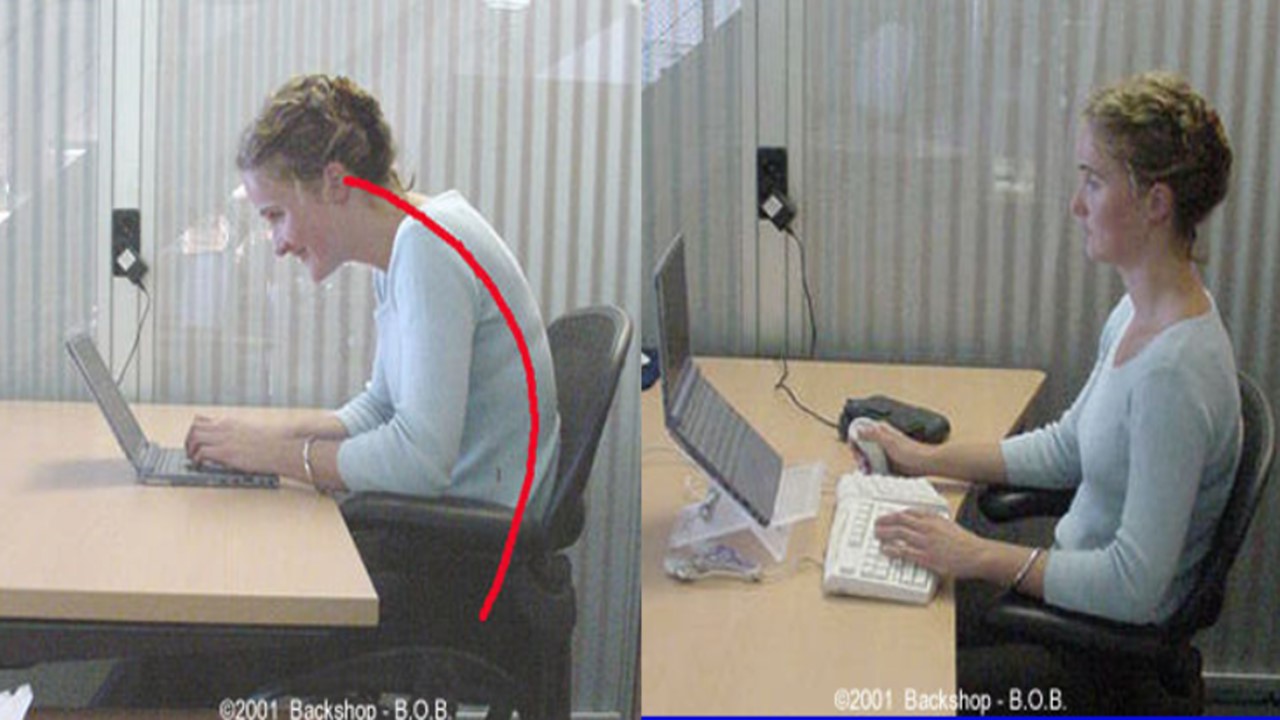

Arrange your computer screen and keyboard so that the screen is at eye level instead of having to reach forward or look down. Similarly, hold your cell phone so that it is at eye level as shown in Figure 3 and 4.

Figure 3. Slouching forward to see the laptop screen can be avoided by using an external keyboard, mouse and desktop riser. Reproduced by permission from www.backshop.nl

Figure 3. Slouching forward to see the laptop screen can be avoided by using an external keyboard, mouse and desktop riser. Reproduced by permission from www.backshop.nl

Figure 4. Avoid the collapsed while looking down at a cell phone by resting the arms on a backpack or purse and keeping the spine and head alighned. Photo of upright position reproduced with permission from Imogen Ragone, https://imogenragone.com/

Check vision

If you are squinting, bringing your nose to the screen, or if the letters are too small or blurry, have your eyes checked to see if you need computer glasses. Generally do not use bifocals or progressive glasses as they force you to tilt your head up or down to see the material at a specific focal length. Other options included changing the display size on screen by making the text and symbols larger may allow you see the screen without bending forward. Just as your muscle of your neck, your eyes need many vision breaks. Look away from the screen out of the window at a distant tree or for a moment close your eyes and breathe.

What to do if you have stiffness and discomfort

My neck was stiff and it hurt the moment I tried to look to the sides. I was totally surprised that I rapidly increased my flexibility and reduced the discomfort when I implemented the following two practices.

Begin by implementing the previous described preventative strategies. Most important is to interrupt static positions and do many small movement breaks. Get up and wiggle a lot. Look at the blog, Freeing the neck and shoulder, for additional practices.

Then, practice the following exercises numerous times during the day to release neck and shoulder tension and discomfort. While doing these practices exhale gently when you are stretching. If the discomfort increases, stop and see your health professional.

REFERENCES

Cohen, S.P. (2015). Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Neck Pain. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 90 (2), 284-299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.09.008

Fejer, R., Kyvik, K.Ohm, & Hartvigesen, J. (2006). The prevalence of neck pain in the world population: a systematic critical review of the literature. European Spine Journal, 15(6), 834-848. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-004-0864-4

Gokhale, E. (2013). 8 Steps to a Pain-Free Back. Pendo Press.

Harvey, R., Peper, E., Booiman, A., Heredia Cedillo, A., & Villagomez, E. (2018). The effect of head and neck position on head rotation, cervical muscle tension and symptoms. Biofeedback. 46(3), 65–71.

Mason, L., Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Hernandez, W. (unpublished). Healing headaches. Does success sustain over time?

Peper, E., Krüger, B., Gokhale, E., & Harvey, R. (in press). Comparing Muscle Activity and Spine Shape in Various Sitting Styles. Biofeedback.

Vineyar, M. (2007). How You Stand, How You Move, How You Live: Learning the Alexander Technique to Explore Your Mind-Body Connection and Achieve Self-Mastery. Boston: Da Capo Lifelong Books.

Optimize success: Enrich treatment with placebo-the body’s own natural healing response*

Posted: May 2, 2019 Filed under: behavior, health, Pain/discomfort, placebo, surgery, Uncategorized 2 CommentsWhen randomized controlled studies of pharmaceuticals or surgery find that the treatment is no more effective than the placebo, the authors conclude that surgery or drugs have no therapeutic value (Moseley et al, 2002; Jonas et al, 2015). Even though the patients may have gotten better, the researchers often do not explore questions such as, why did some of the patients improve just with the placebo treatment; what are the components of the placebo process; and, how can clinicians integrate placebo components into their practice to enhance the body’s own natural healing response.

To explore these topics further, listen to Shankar Vedantam’s outstanding podcast, A Dramatic Cure, from the NPR program, Hidden Brain-A conversation about life’s unseen patterns. Also, read the background materials on the website https://www.npr.org/2019/04/29/718227789/all-the-worlds-a-stage-including-the-doctor-s-office

Placebo effects can be a powerful healing strategy as demonstrated by numerous research studies that have persuasively explored the central features of the placebo effect. The research has found that the more dramatic and impressive the procedure, the more powerful the placebo effect. For example, branded medicine with brightly colored packaging is more effective than generic medicine in plain boxes, an injection of a saline or sugar solution is more effective than taking a sugar pill, and placebo surgery is more effective than simply receiving an injection (Branthwaite & Cooper, 1981; Colloca & Benedetti, 2005). For a detailed exploration of placebo, nocebo and the important role of active placebo, see the blog, How effective is treatment? The importance of active placebos.

Placebo effects can be a powerful healing strategy as demonstrated by numerous research studies that have persuasively explored the central features of the placebo effect. The research has found that the more dramatic and impressive the procedure, the more powerful the placebo effect. For example, branded medicine with brightly colored packaging is more effective than generic medicine in plain boxes, an injection of a saline or sugar solution is more effective than taking a sugar pill, and placebo surgery is more effective than simply receiving an injection (Branthwaite & Cooper, 1981; Colloca & Benedetti, 2005). For a detailed exploration of placebo, nocebo and the important role of active placebo, see the blog, How effective is treatment? The importance of active placebos.

To see the effect of the placebo in action, watch the well-known British stage hypnotist and illusionist, Derren Brown’s video, Fear and Faith (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hfDlfhHVvTY). He magically weaves together a narrative that addresses the powerful influences of the natural, physical, and clinical environment and language used during a ‘therapeutic’ interaction. He shows how the influences of role modeling, the words that increase hope, trust and social compliance, and other covert factors promote healing. It uses the cover of a drug trial to convince various members of the public to overcome their fears using a placebo medicine called “Rumyodin” (which is a made-up name of a fake pharmaceutical) and demonstrates that the limits of experience are the limits of your belief.

This blog post serves as a reminder to ask ourselves as educators and therapists, ‘what can I do to include placebo enhancing components into my practice so that my clinical and educational outcomes are more effective?’ Explore ways to optimize your clinical environment, language use during ‘therapeutic’ interactions, and role modeling to increase hope, trust and social compliance and thereby optimize your clients’ own natural healing response.

Watch the video: Fear and Faith

References:

*I thank Richard Harvey, PhD., for his constructive feedback and James Fadiman, PhD., for reminding me to reframe the term placebo into “the body’s natural healing response.”

Anxiety, lightheadedness, palpitations, prodromal migraine symptoms? Breathing to the rescue!

Posted: March 24, 2019 Filed under: behavior, Breathing/respiration, emotions, health, Pain/discomfort, relaxation, Uncategorized | Tags: anxiety, aura, diaphragmatic breathing, dizzyness, light headedness, migraine, prodrome, symptom prescription 7 Comments

I quickly gasped twice and a sharp pain radiated up my head and into my eye. I shifted to slow breathing and it faded away.

I felt anxious and became aware of my heart palpitations at the end of practicing 70% exhalation for 30 seconds. I was very surprised how quickly my anxiety was triggered when I changed my breathing pattern.

Breathing is the body/mind/emotion/spirit interface which is reflected in our language with phrases such as a sigh of relief, all choked up, breathless, full of hot air, waiting with bated breath, inspired or expired, all puffed up, breathing room, or it takes my breath away. The colloquial phrases reflect that breathing is more than gas exchange and may have the following effects.

- Changes the lymph and venous blood return from the abdomen (Piller, Leduc, & Ryan, 2006). The downward movement of the diaphragm with the corresponding expansion of the abdomen occurs during inhalation as well as slight relaxation of the pelvic floor. The constriction of the abdomen and slight tightening of the pelvic floor causing the diaphragm to go upward and allows exhalation. This dynamic movement increases and decreases internal abdominal and thoracic pressures and acts a pump to facilitate the venous and lymph return from the abdomen. In many people this dynamic pumping action is reduced because the abdomen does not expand during inhalation as it is constricted by tight clothing (designer jean syndrome), holding the abdomen in to maintain a slim self-image, tightening the abdomen in response to fear, or the result of learned disuse to reduce pain from abdominal surgery, gastrointestinal disorders, or abdominal insults (Peper et al, 2015).

- Increases spinal disk movement. Effortless diaphragmatic breathing is a whole body process and associated with improved functional movement (Bradley, & Esformes, 2014). The spine slightly flexes when we exhale and extends when we inhale which allows dynamic disk movement unless we sit in a chair.

- Communicates our emotional state as our breathing patterns reflect our emotional state. When we are anxious or fearful the breath usually quickens and becomes shallow while when we relax the breath slows and the movement is more in the abdomen (Homma, & Masoka, 2008).

- Evokes, maintains, inhibits symptoms or promotes healing. Breathing changes our physiology, thoughts and emotions. When breathing slowly to about 6 breaths a minute, it may enhance heart rate variability and thereby increase sympathetic and parasympathetic balance (Lehrer & Gevirtz, 2014; Moss & Shaffer, 2017).

Can breathing trigger symptoms?

A fifty-five year old woman asked for suggestions what she could do to prevent the occurrence of episodic prodrome and aura symptoms of visual disturbances and problems in concentration that would signal the onset of a migraine. In the past, she had learned to control her migraines with biofeedback; however, she now experienced these prodromal sensation more and more frequently without experiencing the migraine. As she was talking, I observed that she was slightly gasping before speaking with shallow rapid breathing in her chest.

To explore whether breathing pattern may contribute to evoke, maintain or amplify symptoms, the following two behavioral breathing challenges can suggest whether breathing is a factor: Rapid fearful gasping or 70% exhalation.

Behavioral breathing challenge: Rapid fearful gasping

Take a rapid fearful gasp when inhaling as if your feel scared or fearful. Let the air really quickly come in and repeat two or three times as described in the video. Then describe what you experienced.

If you became aware of the onset of a symptom or that the symptom intensified, then your dysfunctional breathing patterns (e.g., gasping, breath holding or shallow chest breathing) may contribute to development or maintenance of these symptoms. For many people when they gasp–a big rapid inhalation as if they are terrified–it may evoke their specific symptom such as a pain sensation in the back of the eye, slight pain in the neck, blanking out, not being able to think clearly, tightness and stiffness in their back, or even an increase in achiness in their joints (Peper et al, 2016).

To reduce or avoid triggering the symptom, breathe diaphragmatically without effort; namely each time you gasp, hold your breath or breathe shallowly, shift to effortless diaphragmatic breathing.

The above case of the woman with the prodromal migraine symptoms, she experienced visual disturbances and fuzziness in her head after the gasping. This experience allowed her to realize that her breathing style could be a contributing in triggering her symptoms. When she then practiced slow diaphragmatic breathing for a few breaths her symptoms disappeared. Hopefully, if she replaces gasping and shallow breathing with effortless diaphragmatic breathing then there is a possibility that her symptoms may no longer occur.

Behavioral breathing challenge: 70% exhalation

While sitting, breathe normally for a minute. Now change your breathing pattern so that you exhale only 70% or your previous inhaled air. Each time you exhale, exhale only 70% of the inhaled volume. If you need to stop, just stop, and then return to this breathing pattern again by exhaling only 70 percent of the inhaled volume of air. After 30 seconds, let go and breathe normally as guided by the video clip. Observe what happened?

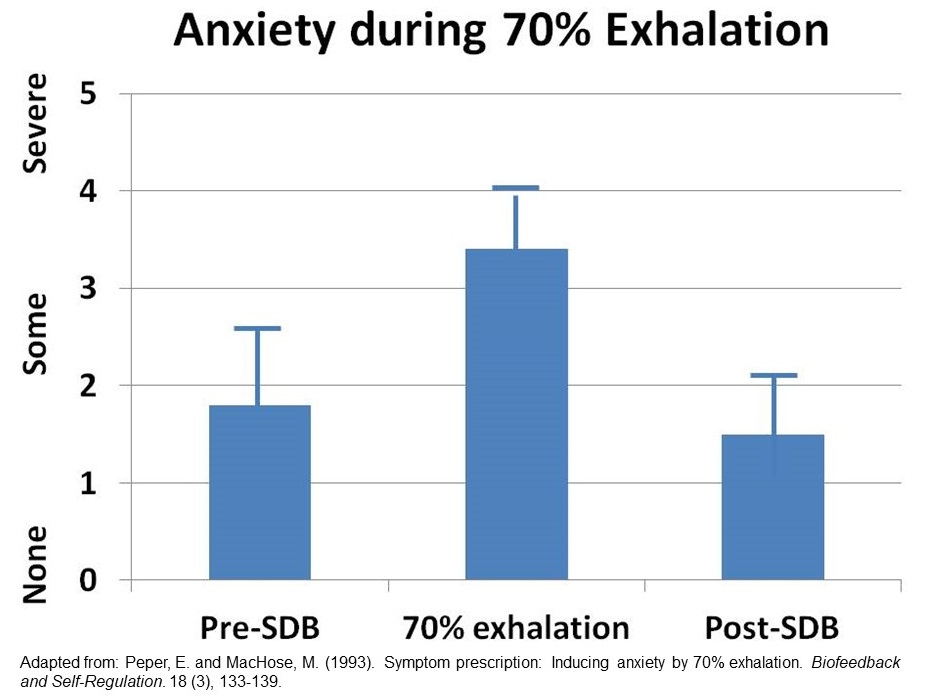

In our research study with 35 volunteers, almost all participants experienced an increase in arousal and symptoms such as lightheadedness, dizziness, anxiety, breathless, neck and shoulder tension after 30 seconds of incomplete exhalation as shown in Figure 1 and Table 1 (Peper and MacHose, 1993).

Figure 1. Increase in anxiety evoked by 70% exhalation.

Table 1. Symptoms experienced after exhalation 70%.

Although these symptoms may be similar to those evoked by hyperventilation and overbreathing, they are probably not caused by the reduction of end-tidal carbon dioxide (CO2). The apparent decrease in end-tidal PCO2 is cause by the room air mixing with the exhaled air and not a measure of end-tidal CO2 (Peper and Tibbets, 1992). Most likely the symptoms are associated by the shallow breathing that occurs when we were scared or terrified.

People who have a history of anxiety, panic, nervousness and tension as compared to those who report low anxiety tend to report more symptoms when exhaling 70% of inhaled air for 30 seconds. If this practice evoked symptoms, then changing the breathing patterns to slower diaphragmatic breathing may be a useful self-regulation strategy to optimize health.

These two behavior breathing challenges are useful demonstrations for students and clients that breathing patterns can influence symptoms. By experiencing ON and OFF control over their symptoms with breathing, the person now knows that breathing can affect their health and well being.

BLOGS WITH INSTRUCTIONS FOR LEARNING EFFORTLESS DIAPHRAGMATIC BREATHING

https://peperperspective.com/2017/11/17/breathing-to-improve-well-being/

https://peperperspective.com/2018/10/04/breathing-reduces-acid-reflux-and-dysmenorrhea-discomfort/

https://peperperspective.com/2015/02/18/reduce-hot-flashes-and-premenstrual-symptoms-with-breathing/

https://peperperspective.com/2017/03/19/enjoy-sex-breathe-away-the-pain/

REFERENCES

Lehrer, P.M. & Gevirtz, R. (2014). Heart rate variability biofeedback: how and why does it work? Frontiers in Psychology, 5

Head position, it matters!*

Posted: January 23, 2019 Filed under: behavior, digital devices, Exercise/movement, health, Neck and shoulder discomfort, Pain/discomfort, posture, Uncategorized 5 CommentsThe blog has been adapted from our published article, Harvey, R., Peper, E., Booiman, A., Heredia Cedillo, A., & Villagomez, E. (2018). The effect of head and neck position on head rotation, cervical muscle tension and symptoms. Biofeedback. 46(3), 65–71.

Why is it so difficult to turn your head to see what is behind you?

How come so many people feel pressure in the back of the head or have headaches after working on the computer?

Your mother may have been right when she said, “Sit up straight! Don’t slouch!” Sitting slouched and collapsed is the new norm as digital devices force us to slouch or tilt our head downward. Sometimes we scrunch our neck to look at the laptop screen or cellphone. This collapsed position also contributes to an increased in musculoskeletal dysfunction (Nahar & Sayed, 2018). The more you use a screen for digital tasks, the more you tend to have head-forward posture, especially when the screens are small (Kang, Park, Lee, Kim, Yoon, & Jung, 2012). In addition, the less time children play outside and the more time young children watch the screen, the more likely will they become near sighted and need to have their vision corrected (Sherwin et al, 2012). In addition, the collapsed head forward position unintentionally decreases subjective energy level and may amplify defeated, helpless, hopeless thoughts and memories (Bader, 2015; Peper & Lin, 2012; Tsai, Peper, & Lin, 2016; Peper et al, 2017).

Explore the following two exercises to experience how the head forward position immediately limits head rotation and how neck scrunching can rapidly induce back of the head pressure and headaches.

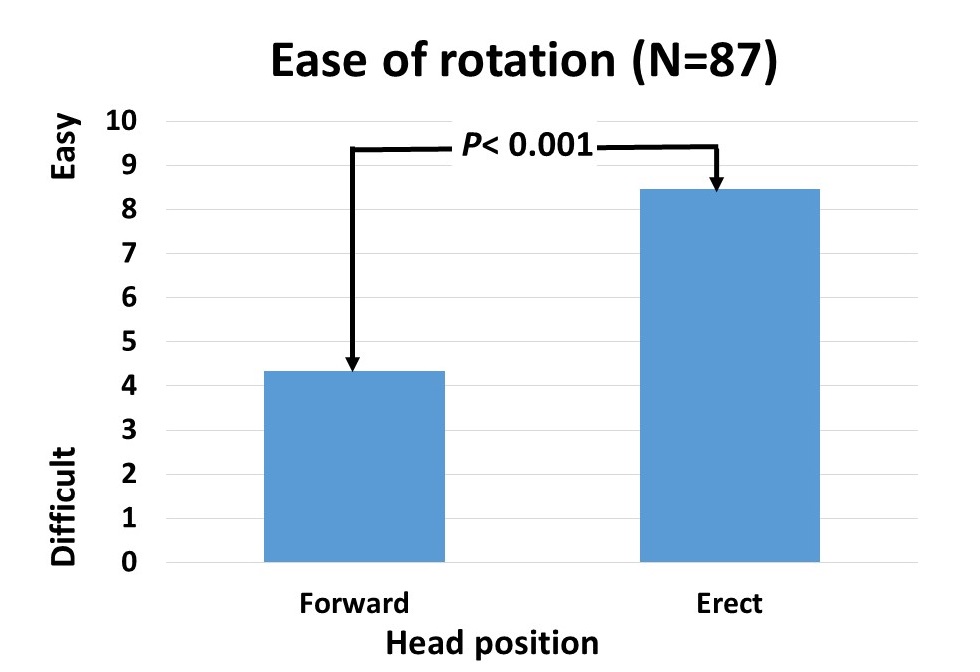

Exercise 1. Effect of head forward position on neck rotation

Sit at the edge of the chair and bring your head forward, then rotate your head to the right and to the left and observe how far you can rotate. Then sit erect with the crown of the head reaching towards the ceiling and again rotate your head from right to left and observe how far you can rotate as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Head-erect versus head-forward position.

Figure 1. Head-erect versus head-forward position.

What did you experience?

Most likely your experience is similar to the 87 students (Mean Age = 23.6 years) who participated in this classroom activity designed to bring awareness of the effect of head and neck position on symptoms of muscle tension. 92.0% of the students reported that is was much easier to rotate their head and could rotate further during the head-erect position as compared to the head-forward position (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Self-report of ease of head rotation.

Figure 2. Self-report of ease of head rotation.

What does this mean?

Almost all participants were surprised that the head forward position restricted head rotation as well as reduced peripheral awareness (Fernandez-de-Las-Penas et al., 2006). The collapsed head forward may directly affect personal safety; since, it reduces peripheral awareness while walking, biking or driving a car. In addition, when the head is forward, the cervical vertebrae are in a more curved position compared to the erect head with the normal cervical curve (Kang et al., 2012). This means that in the head-forward position, the pressure on the vertebrae and the intervertebral disc is elevated compared to the preferred position with a stretched neck. This increases the risk of damage to the vertebrae and intervertebral disc (Kang et al, 2012). It also means that the muscles that hold the head in the forward position have to work much harder.

Be aware that of factors that contribute to a head-forward position.

- Sitting in a car seat in which the headrest pushes the head forward. Solutions: Tilt the headrest back or put pillow in your back from your shoulders to your pelvis to move your body slightly forward.

- If you wear a bun or ponytail, the headrest (car, airplane seat, or chair) will often push your head forward. This causes a change of the head to a more forward position and it becomes a habit without the person even knowing it. Solution: Place a pillow in your back to move your body forward or loosen the bun or ponytail.

- Difficulty reading the text on the digital screen. The person automatically cranes their head forward to read the text. Solutions: Have your eyes checked and, if necessary, wear computer-reading glasses; alternatively, increase the font size and reduce glare.

- Working on a laptop and looking down on the screen. Solutions: Detachable keyboard and laptop on a stand to raise screen to eye level as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Trying to read the laptop screen, which causes the head to go forward as compared to raising the screen and using an external keyboard. Reproduced by permission from www.backshop.nl

- Being tired or exhausted encourages the body to collapse and slouch and increases the muscle tension in the upper cervical region. You can explore the effect of tiredness that causes slouching and head-forward position during the day by observing the following if you drive a car.

In the morning, adjust your rear mirror and side mirrors. Then at the end of the day when you sit in the car, you may note that you may need to readjust your inside rear mirror. No, the mirror didn’t change of position during the day by itself—you slouched unknowingly. Solutions: Take many breaks during the day to regenerate, install stretch break reminders, or wear an UpRight Go posture feedback device to remind you when you begin to slouch (Peper, Lin & Harvey, 2017).

Exercise 2: Effect of neck scrunching on symptom development

Sit comfortably and your nose forward and slightly. While the head is forward tighten your neck as if your squeezing the back of the head downward into the shoulders and hold this contracted neck position for 20 seconds. Let go and relax.

What did you experience?

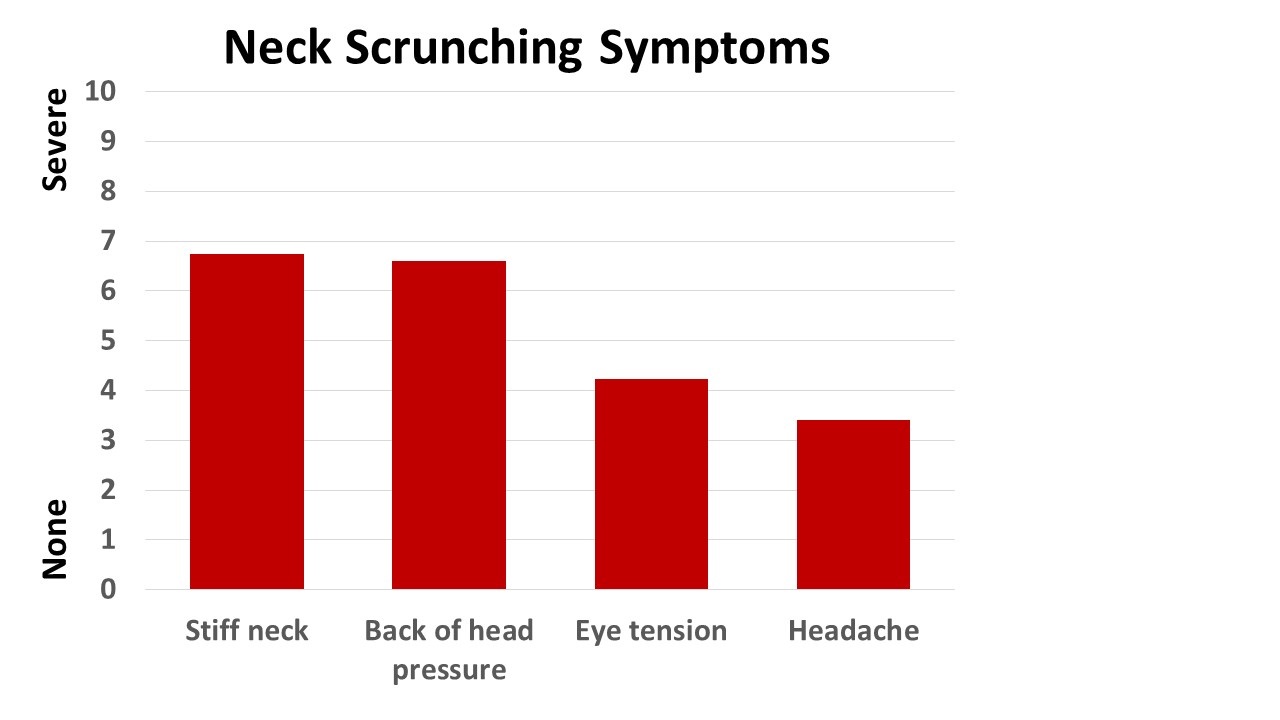

Most likely your experience was similar to 98.4% of the 125 college students who reported a rapid increase in discomfort after neck scrunching as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Symptoms induced by 30 seconds of neck scrunching.

Figure 4. Symptoms induced by 30 seconds of neck scrunching.

During scrunching there was a significant increase in the cervical and trapezius sEMG activity recorded from 12 volunteers as shown in Figure 5. Figure 5. Change in cervical and trapezius sEMG during head forward and neck scrunching.

Figure 5. Change in cervical and trapezius sEMG during head forward and neck scrunching.

What does this mean?

Nearly all participants were surprised that 30 seconds of neck scrunching would rapidly increase induce discomfort and cause symptoms. This experience provided motivation to identify situations that evoked neck scrunching and avoid those situations or change the ergonomics that induced the neck scrunching. If you experience headaches or neck discomfort, scrunching could be a contributing factor.

Factors that contribute to neck scrunching and discomfort.

- Bringing your head forward to see the text or graphics more clearly. There may be multiple causes such as blurred vision, tiny text font size, small screen and ergonomic factors. Possible solutions. Have your eyes checked and if appropriate wear computer-reading glasses. Increase the text font size or use a large digital screen. Reduce glare and place the screen at the appropriate height so that the top of the screen is no higher than your eyebrows.

- Immobility and working in static position for too long a time period. Possible solutions. Interrupt your static position with movements every few minutes such as stretching, standing, and wiggling.

Conclusion

These two experiential practices are “symptom prescription practices” that may help you become aware that head position contributes to symptoms development. For example, if you suffer from headaches or neck and backaches from computer work, check your posture and make sure your head is aligned on top of your neck–as if held by an invisible thread from the ceiling and take many movement breaks.The awareness may help you to identify situations that cause these dysfunctional body patterns that could cause symptoms. By inhibiting these head and neck patterns, you may be able to reduce or avoid discomfort. Just as a picture is worth a thousand words, self-experience through feeling and seeing is believing.

REFERENCES

Bader, E. E. (2015). The Psychology and Neurobiology of Mediation. Cardozo J. Conflict Resolution, 17, 363.

Fernandez-de-Las-Penas, C., Alonso-Blanco, C., Cuadrado, M. L., & Pareja, J. A. (2006). Forward head posture and neck mobility in chronic tension-type headache: A blinded, controlled study. Cephalalgia, 26(3), 314-319.

Kang, J. H., Park, R. Y., Lee, S. J., Kim, J. Y., Yoon, S. R., & Jung, K. I. (2012). The effect of the forward head posture on postural balance in long time computer based worker. Annals of rehabilitation medicine, 36(1), 98-104.

Lee, M. Y., Lee, H. Y., & Yong, M. S. (2014). Characteristics of cervical position sense in subjects with forward head posture. Journal of physical therapy science, 26(11), 1741-1743. https://doi.org/10.1589/jpts.26.1741

Nahar, S., & Sayed, A. (2018). Prevalence of musculoskeletal dysfunction in computer science students and analysis of workstation characteristics-an explorative study. International Journal of Advanced Research in Computer Science, 9(2), 21-27. https://doi.org/10.26483/ijarcs.v9i2.5570

Peper, E., & Lin, I. M. (2012). Increase or decrease depression: How body postures influence your energy level. Biofeedback, 40(3), 125-130

Peper, E., Lin, I-M., Harvey, R., & Perez, J. (2017). How posture affects memory recall and mood. Biofeedback.45 (2), 36-41.

Peper, E., Lin, I-M, & Harvey, R. (2017). Posture and mood: Implications and applications to therapy. Biofeedback.35(2), 42-48.

Sherwin, J.C., Reacher, M.H., Keogh, R.H., Khawaja, A.P, Mackey, D.A., & Foster, P.J. (2012). The Association between Time Spent Outdoors and Myopia in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ophthalmology, 119(10), 2141-2151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.04.020

Tsai, H. Y., Peper, E., & Lin, I. M. (2016). EEG patterns under positive/negative body postures and emotion recall tasks. NeuroRegulation, 3(1), 23-27.

*This blog was adapted from our published article, The blog has been adapted from our research article, Harvey, R., Peper, E., Booiman, A., Heredia Cedillo, A., & Villagomez, E. (2018). The effect of head and neck position on head rotation, cervical muscle tension and symptoms. Biofeedback. 46(3), 65–71.

Today is a new day-a new beginning

Posted: December 31, 2018 Filed under: behavior, health, Pain/discomfort, self-healing, Uncategorized | Tags: dance, hope, joy, pain, regenration, spinal injury 3 CommentsIn a world of turmoil, it is often challenging to think that tomorrow can be different and better. Yet, each day is an opportunity to accept whatever happened in the past and look forward to the unfolding present. So often, we anticipate that the future will be the same or worse especially if we feel depressed, suffer from ongoing pain, chronic illness, family or work stress, etc. At those moments, we forget that yesterday’s memories may contribute to how we experience and interpret the future. Most of us do not know what the future will bring, thus be open to new opportunities for growth and well-being. For the New Year, adapt a daily ritual that I learned from a remarkable healer Dora Kunz.

Each morning when you get out of bed, take a few slow deep breaths. Then think of someone who you feel loved by and makes you smile whether your grandmother, aunt or dog. Then when you get up and put your feet on the ground, say out loud, “Today is a new day- a new beginning.”

Watch the following two videos of people for whom the future appeared hopeless and yet had the courage to transcend their limitations and offer inspiration and joy.

Janine Shepherd: A broken body isn’t a broken person. Cross-country skier Janine Shepherd hoped for an Olympic medal — until she was hit by a truck during a training bike ride. She shares a powerful story about the human potential for recovery. Her message: you are not your body, and giving up old dreams can allow new ones to soar.

Ma Li and Zhai Xiaowei: Hand in Hand. This is a video of a broadcast that originally aired on China’s English-language CCTV channel 9 during a modern dance competition in Beijing, China in 2007. This very unique couple–she without an arm, he without a leg–was one of the finalists among 7000 competitors in the 4th CCTV national dance competition. It is the first time a handicapped couple had ever entered the competition. They won the silver medal and became an instant national hit. The young woman, in her 30’s, was a dancer who had trained since she was a little girl. Later in life, she lost her entire right arm in an automobile accident and fell into a state of depression for a few years. After rebounding, she decided to team with a young man who had lost his leg in a farming accident as a boy and who was completely untrained in dance. After a long and sometimes agonizing training regimen, this is the result. The dance is performed by Ma Li (馬麗) and Zhai Xiaowei (翟孝偉). The music “Holding Hands” is composed by San Bao and choreographed by Zhao Limin.

Breathing reduces acid reflux and dysmenorrhea discomfort

Posted: October 4, 2018 Filed under: Breathing/respiration, Pain/discomfort, posture, relaxation, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: acid reflux, dysmenorrhea, gastroesophageal reflux disease, GERD, menstrual cramps, PMS 14 CommentsPublished as: Peper, E., Mason, L., Harvey, R., Wolski, L, & Torres, J. (2020). Can acid reflux be reduced by breathing? Townsend Letters-The Examiner of Alternative Medicine, 445/446, 44-47. https://www.townsendletter.com/article/445-6-acid-reflux-reduced-by-breathing/

“Although difficult and going against my natural reaction to curl up in the response to my cramps, I stretched out on my back and breathed slowly so that my stomach got bigger with each inhalation. My menstrual pain slowly decreased and disappeared.

“For as long as I remember, I had stomach problems and when I went to doctors, they said, I had acid reflux. I was prescribed medication and nothing worked. The problem of acid reflux got really bad when I went to college and often interfered with my social activities. After learning diaphragmatic breathing so that my stomach expanded instead of my chest, I am free of my symptoms and can even eat the foods that previously triggered the acid reflux.”

In the late 19th earlier part of the 20th century many women were diagnosed with Neurasthenia. The symptoms included fatigue, anxiety, headache, fainting, light headedness, heart palpitation, high blood pressure, neuralgia and depression. It was perceived as a weakness of the nerves. Even though the diagnosis is no longer used, similar symptoms still occur and are aggravated when the abdomen is constricted with a corset or by stylish clothing (see Fig 1).

Figure 1. Wearing a corset squeezes the abdomen.

The constricted waist compromises the functions of digestion and breathing. When the person inhales, the abdomen cannot expand as the diaphragm is flattening and pushing down. Thus, the person is forced to breathe more shallowly by lifting their ribs which increases neck and shoulder tension and the risk of anxiety, heart palpitation, and fatigue. It also can contribute to abdominal discomfort since abdomen is being squeezed by the corset and forcing the abdominal organs upward. It was the reason why the room on top of stairs in the old Victorian houses was call the fainting room (Melissa, 2015).

During inhalation the diaphragm flattens and attempts to descend which increases the pressure of the abdominal content. In some cases this causes the stomach content to be pushed upward into the esophagus which could result in heart burn and acid reflux. To avoid this, health care providers often advice patients with acid reflux to sleep on a slanted bed with the head higher than their feet so that the stomach content flows downward. However, they may not teach the person to wear looser clothing that does not constrict the waist and prevent designer jean syndrome. If the clothing around the waist is loosened, then the abdomen may expand in all directions in response to the downward movement of the diaphragm during inhalation and not squeeze the stomach and thereby pushing its content upward into the esophagus.

Most people have experienced the benefits of loosening the waist when eating a large meal. The moment the stomach is given the room to spread out, you feel more comfortable. If you experienced this, ask yourself, “Could there be a long term cost of keeping my waist constricted?” A constricted waist may be as harmful to our health as having the emergency brake on while driving for a car.

We are usually unaware that shallow rapid breathing in our chest can contribute to symptoms such as anxiety, neck and shoulder tension, heart palpitations, headaches, abdominal discomfort such as heart burn, acid reflux, irritable bowel syndrome, dysmenorrhea and even reduced fertility (Peper, Mason, & Huey, 2017; Domar, Seibel, & Benson, 1990).

Assess whether you are at risk for faulty breathing

Stand up and observe what happens when you take in a big breath and then exhale. Did you feel taller when you inhaled and shorter/smaller when you exhaled?

If the answer is YES, your breathing pattern may compromise your health. Most likely when you inhaled you lifted your chest, slightly arched your back, tightened and raised your shoulders, and lifted your head up while slightly pulling the stomach in. When you exhaled, your body relaxed and collapsed downward and even the stomach may have relaxed and expanded. This is a dysfunctional breathing pattern and the opposite of a breathing pattern that supports health and regeneration as shown in figure 2.

Figure 2. Incorrect and correct breathing. Source unknown.

Observe babies, young children, dogs, and cats when they are peaceful. The abdomen is what moves during breathing. While breathing in, the abdomen expands in all 360 degrees directions and when breathing out, the abdomen constricts and comes in. Similarly when dogs or cats are lying on their sides, their stomach goes up during inhalation and goes down during exhalation.

Many people tend to breathe shallowly in their chest and have forgotten—or cannot– allow their abdomen and lower ribs to widen during inhalation (Peper et al, 2016). These factors include:

- Constriction by the modern corset called “Spanx” to slim the figure or by wearing tight fitting pants. In either case the abdominal content is pushed upward and interferes with normal healthy breathing.

- Maintaining a slim figure by pulling the abdomen (I will look fat when my stomach expands; I will suck it in).

- Avoiding post-surgical abdominal pain by inhibiting abdominal movement. Numerous patients have unknowingly learned to shallowly breathe in their chest to avoid pain at the site of the incision of the abdominal surgery such as for hernia repair or a cesarean operation. This dysfunctional breathing became the new normal unless they actively practice diaphragmatic breathing.

- Slouching as we sit or watch digital screens or look down at our cell phone.

Observe how slouching affects the space in your abdomen.

When you shift from an upright erect position to a slouched or protective position the distance between your pubic bone and the bottom of the sternum (xiphoid process) is significantly reduced.

- Tighten our abdomen to protect ourselves from pain and danger as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Erect versus collapsed posture. There is less space for the abdomen to expand in the protective collapsed position. Reproduced by permission from Clinical Somatics (http://www.clinicalsomatics.ie/).

Regardless why people breathe shallowly in their chest or avoid abdominal and lower rib movement during breathing, by re-establishing normal diaphragmatic breathing many symptoms may be reduced. Numerous students have reported that when they shift to diaphragmatic breathing which means the abdomen and lower ribs expand during inhalation and come in during exhalation as shown in Figure 4, their symptoms such as acid reflux and menstrual cramp significantly decrease.

Figure 4. Diaphragmatic breathing. Reproduced from: www.devang.house/blogs/thejob/belly-breathing-follow-your-gut.

Reduce acid reflux

A 21-year old student, who has had acid reflux (GERD-gastroesophageal reflux diseases) since age 6, observed that she only breathed in her chest and that there were no abdominal movements. When she learned and practiced slower diaphragmatic breathing which allowed her abdomen to expand naturally during inhalation and reduce in size during exhalation her symptoms decreased. The image she used was that her lungs were like a balloon located in her abdomen. To create space for the diaphragm going down, she bought larger size pants so that her abdominal could spread out instead of squeezing her stomach (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Hydraulic model who inhaling without the abdomen expanding increases pressure on the stomach and possibly cause stomach fluids to be pushed into the esophagus.

She practiced diaphragmatic breathing many times during the day. In addition, the moment she felt stressed and tightened her abdomen, she interrupted this tightening and re-established abdominal breathing. Practicing this was very challenging since she had to accept that she would still be attractive even if her stomach expanded during inhalation. She reported that within two weeks her symptom disappeared and upon a year follow-up she has had no more symptoms. In the video she describes her experiences of integrate breathing and awareness into daily life.

We have also use this similar approach to successfully overcome irritable bowel syndrome see: https://peperperspective.com/2017/06/23/healing-irritable-bowel-syndrome-with-diaphragmatic-breathing/

Take control of menstrual cramps

Numerous college students have reported that when they experience menstrual cramps, their natural impulse is to curl up in a protective cocoon. If instead they interrupted this natural protective pattern and lie relaxed on their back with their legs straight out and breathe diaphragmatically with their abdomen expanding and going upward during inhalation, they report a 50 percent decrease in discomfort (Gibney & Peper, 2003). For some the discomfort totally disappears when they place a warm pad on their lower abdomen and focused on breathing slowly about six breaths per minute so that the abdomen goes up when inhaling and goes down when exhaling. At the same time, they also imagine that the air would flow like a stream from their abdomen through their legs and out their feet while exhaling. They observed that as long as they held their abdomen tight the discomfort including the congestive PMS symptoms remained. Yet, the moment they practice abdominal breathing, the congestion and discomfort is decreased. Most likely the expanding and constricting of the abdomen during the diaphragmatic breathing acts as a pump in the abdomen to increase the lymph and venous blood return and improve circulation.

Conclusion

Breathing is the body-mind bridge and offers hope for numerous disorders. Slower diaphragmatic breathing with the corresponding abdomen movement at about six breaths per minute may reduce autonomic dysregulation. It has profound self-healing effects and may increase calmness and relaxation. At the same time, it may reduce heart palpitations, hypertension, asthma, anxiety, and many other symptoms.

References

DeVault, K.R. & Castell, D.O. (2005). Updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. The American Journal of Gastroenterology, 100, 190-200.

Domar, A.D., Seibel, M.M., & Benson, H. (1990). The Mind/Body Program for Infertility: a new behavioral treatment approach for women with infertility. Fertility and sterility, 53(2), 246-249.

Gibney, H.K. & Peper, E. (2003). Taking control: Strategies to reduce hot flashes and premenstrual mood swings. Biofeedback, 31(3), 20-24.

Johnson, L.F. & DeMeester, T.R. (1981). Evaluation of elevation of the head of the bed, bethanechol, and antacid foam tablets on gastroesophageal reflux. Digestive Diseases Sciences, 26, 673-680. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7261830

Melissa. (2015). Why women fainted so much in the 19th century. May 20, 2015. Donloaded October 2, 1018. http://www.todayifoundout.com/index.php/2015/05/women-fainted-much-19th-century/

Peper, E., Booiman, A., Lin, I-M, Harvey, R., & Mitose, J. (2016). Abdominal SEMG Feedback for Diaphragmatic Breathing: A Methodological Note. Biofeedback. 44(1), 42-49.

Peper, E., Mason, L., Huey, C. (2017). Healing irritable bowel syndrome with diaphragmatic breathing. Biofeedback. (45-4)

Stanciu, C. & Bennett, J.R.. (1977). Effects of posture on gastro-oesophageal reflux. Digestion, 15, 104-109. https://www.karger.com/Article/Abstract/197991

Family or work? The importance of value clarification

Posted: May 4, 2018 Filed under: Breathing/respiration, mindfulness, Neck and shoulder discomfort, Pain/discomfort, relaxation, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: meaning, regeneration, relaxation, respiration, stress management, values clarification 1 CommentRichard Harvey, PhD and Erik Peper, PhD

In a technologically modern world, many people have the option of spending 24 hours a day/ 7 days a week continuously interacting via telephone, text, work and personal emails or internet websites and various social media platforms such as Facebook, What’s App, Instagram, Twitter, LinkedIn and Snapchat. How many people do we know who work too many hours, watch too many episodes on digital screens, commute too many hours, or fill loneliness with online versions of retail therapy? In the rush of work-a-day survival as well as being nudged and bombarded with social media notifications, or advertisements for material goods, we forget to nurture meaningful friendships and family relationships (Peper and Harvey, 2018). The following ‘values clarification’ practice may help us identify what is most important to us and help keep sight of those things that are most relevant in our lives (Hofmann, 2008; Knott, Ribar, & Duson, 1989; Twohig & Crosby, 2009;. Peper, 2014).

Give yourself about 12 minutes of uninterrupted time to do this practice. Do this practice by yourself, in a group, or with family and friends. Have a piece of paper ready. Be guided by the two video clips at the end of the blog. Begin with the Touch Relaxation and Regeneration Practice to relax and let go of thoughts and worries, then follow it with the Value Clarification Practice.

Touch Relaxation and Regeneration Practice

Turn off your cell phone and let other know not to interrupt for the next 12 minutes, then engage in the following six-minute relaxation exercise. If your attention wanders during the practice, then bring your attention back to the various sensations in your body.

- Sit comfortably, then lift your arms from your lap, holding them parallel to the floor and tighten your arms while making a fist in each hand. While holding your fists tightly closed, keep breathing for a total of 10 seconds before dropping the arms to your lap while you relax all of your muscles. Attend for 20 seconds to the changing sensations in arms and hands as they relax. If your attention wanders bring it back to the sensations in your arm and hands.

- Tighten your buttock muscles and bend your ankles so that the toes move upwards in a direction towards your knees. Keep breathing and hold your toes upwards for 10 seconds and then let the toes move down to the floor, letting go and relaxing all the muscles of the lower trunk and legs. Feel your knees widening and feel your buttock muscles relaxing. Continue attending to the body and muscle sensations for the next 20 seconds. If your attention wanders bring it back to the sensations in your body.

- Tighten your whole body by pressing your knees together, lifting your arms up from your lap, making a fist and wrinkling your face. Hold the tension while continuing to breath for 10 seconds. Let go and relax and feel the whole body sinking and relaxing and being supported by the chair for the next 20 seconds.

- Bring your right hand to your left shoulder. Over the next 10 seconds, inhale for three or four seconds and as you exhale for five or six seconds, with your right hand stroke down your left arm from your shoulder to past your hand. Imagine that the exhaled air is flowing through your arm and out your hand. Repeat at least once more.

- Bring your left hand to your right shoulder. Inhale for three or four seconds and as you exhale for five or six seconds with your left hand stroke down your right arm from your shoulder to past your hand. Imagine that the exhaled air is flowing through your arm and out your hand. Repeat at least once more.

- Bring both hands to the sides of your hips. Inhale for three or four seconds and as you exhale for five or six seconds stroke your legs with your hands from the hips to the ankles. Imagine that the exhaled air is flowing through your legs and out your feet. Repeat a least once more.

- Close your eyes and inhale for three or four seconds, then hold your breath for seven seconds slowly exhale for eight seconds. Imagine as you exhale the air flowing through your arms and out your hands and through your legs and out your feet. Continue breathing easily and slowly such as inhaling for three or four seconds, and out for five to seven seconds. If your attention wanders just bring it back to the sensations going down your arms and legs. Feel the relaxation and peacefulness.

- Take another deep breath and then stretch and continue with the Value Clarification

Value Clarification Practice

Get the paper and pen and do the following Value Clarification Practice.

- Quickly (e.g. 30-60 seconds) list the 10 most important things in your life. For the activity to work, the list must contain 10 important things that may be concrete or abstract, ranging from material things such as a smart phone or a car to immaterial things such as family, love, god, health… If you need to, break up a larger category into smaller pieces. For example, if one item on the list is family, and you only have seven items on the list, assuming you have a family of four, then identify separate family members in order to complete a list of 10 important things.

- To start off, in only 10 seconds, please cross off three items from the list, then explain why you removed those three. If done in a group of people turn to the person explain why you made these choices.

- Next, in only 10 seconds, please cross off three more, then explain why you kept what you kept. If done in a group of people turn to the person explain why you made these choices.

- Finally, in only 10 seconds, please cross off three more, then reveal the one most important thing on your list. Share your choice for the item you kept and how you felt while crossing items from the list or keeping them.

- When engaging with this type of values clarification practice, please remind yourself and others that the items on the list were never gone, they are always in your life to the extent that you can honor the presence of those things in your life.

We have done these exercises with thousands of student and adults. The most common final item on the list is family or an individual family member. Sometimes, categories such as health or god appear, however it is extremely rare that material items make it to the final round. For example, no one would report that their last item is their job, their bank account, their house, or their smart phone. It is common that people have difficulty choosing the last item on their list, often taking more than 10 seconds to choose. For example, they find that they cannot choose between eliminating individual family members. For those who find the activity too difficult, remind them that the exercise is voluntary and meant as a ‘thought experiment’ which they may stop at any time.

Reflect how much of your time is spent nurturing what is most important to you? In many cases we feel compelled to finish some employment priorities instead of making time for nurturing our family relationship. And when we become overwhelmed with work demands, we retreat to sooth our difficulties by checking our email or browsing social media rather than supporting the family connections that are so important to us.

Organize an action plan to honor and support your commitment to the items on your list that you value the most. If possible let other people know what you are doing.

- Describe in detail what you will do in real life and in real time in service to honor and support your relationships with the things that you value.

- Describe in detail what you will do, when you will do it, with whom you will do it, at what time you will do it, and anticipate what will get in the way of doing it. For example, how will you resolve any conflicts between what you plan and what you actually do when there is not enough time to carry out your plans?

- Schedule a time during the following week for feedback about your plans to honor and support the things you value.

Summary

Many people experience that it is challenging to make time to honor and support their primary values given the ongoing demands of daily living. To be congruent with our values means making ongoing choices such as listening and sharing experiences with your partner versus binging on videos or, using your smartphone for answering email or texting instead of watching your child play ball.

The values you previously identified are similar to those identified by patients who are in hospice and dying. For them as they look back on their lives, the five most common regret are (Ware, 2009; Ware, 2012):

- I wish I’d the courage to live a life true to myself, not the life others expected of me.

- I wish I hadn’t worked so hard.

- I wish I had the courage to express my feelings.

- I wish I had stayed in touch with my friends.

- I wish I had let myself be happier.

Take the time to plan actions that support your identified values. Feel free to watch the following videos that guide you through the activities described here.

References

Hofmann, S.G. (2008). Acceptance and commitment therapy: New wave or Morita therapy?. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 15(4), 280-285. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2008.00138.x

Knott, J.E., Ribar, M.C. & Duson, B.M. (1989). Thanatopics: Activities and Exercises for Confronting Death, Lexington Books: Lexington, MA. https://www.amazon.com/Thanatopics-Activities-Exercise-Confronting-Death/dp/066920871X

Peper, E. (October 19, 2014). Choices-Creating meaningful days. https://peperperspective.com/2014/10/19/choices-creating-meaningful-days/

Peper, E. & Harvey, R. (2018). Digital addiction: increased loneliness, depression, and anxiety. NeuroRegulation. 5(1),3–8. doi:10.15540/nr.5.1.3 http://www.neuroregulation.org/article/view/18189/11842

Twohig, M.P. & Crosby, J.M. (2009). Values clarification. In: O’Donohue & W.T., Fisher, J.E., Eds. Cognitive behavior therapy: applying empirically supported techniques in your practice. Wiley: Hoeboken, N.J., p. 681-686.

Ware, B. (2009). Regrets of the dying. https://bronnieware.com/blog/regrets-of-the-dying/

Ware, B. (2012). The top five regrets of dying: A life transformed by the dearly departing. Hay House. ISBN: 978-1401940652

Surgery: Hope for the best and plan for the worst!

Posted: March 18, 2018 Filed under: Pain/discomfort, placebo, self-healing, stress management, surgery, Uncategorized | Tags: anesthesia, hernia, iatrogenic illness, technology, urinary retention 20 CommentsAdapted from: Peper, E. Surviving and preventing medical errors. (2019). Townsend Letter-The Examiner of Alternative Medicine. 429, 63-69. https://townsendletter.com/surviving-and-preventing-medical-errors-peper/

The purpose of this blog is to share what I have learned from a cascade of medical errors that happen much more commonly than surgeons, hospitals, or health care providers acknowledge and is the third leading cause of death in the US (Makary, M.A. & Daniel, M., 2016). My goal here is to provide a few simple recommendations to reduce these errors.

It is now two years since my own surgery—double hernia repair by laparoscopy. The recovery predicted by my surgeon, “In a week you can go swimming again,” turned out to be totally incorrect.

Six weeks after the surgery, I was still lugging a Foley catheter with a leg collection bag that drained my bladder. I had swelling due to blood clots in the abdominal area around my belly button, severe abdominal cramping, and at times, overwhelming spasms. For six weeks my throat was hoarse following the intubation. Instead of swimming, hiking, walking, working, and making love with my wife, I was totally incapacitated, unable to work, travel, or exercise. I had to lie down every few hours to reduce the pain and the spasms.

Instead of going to Japan for a research project, I had to cancel my trip. Rather than teaching my class at the University, I had another faculty member teach for me. I am a fairly athletic guy—I swim several times a week, bike the Berkeley hills, and hiked. Yet after the surgery, I avoided even walking in order to minimize the pain. I moved about as if I were crippled. Now two years later, I finally feel healthy again.

How come my experiences were not what the surgeon promised?

All those who cared for me during this journey were compassionate individuals, committed to doing their best, including the emergency staff, the nurses, my two primary physicians, my surgeon, and my urologist. However, given the personal, professional, and economic cost to me and my family, I feel it is important to assess where things went wrong. The research literature makes it clear that my experience was by no means unique, so I have summarized some of the most important factors that contributed to these unexpected complications, following “simple arthroscopic surgery.”

- Underestimating the risk. Although the surgeon suggested that the operation would be very low risk with no complications, the published research data does not support his optimistic statement and misrepresented the actual risk. Complications for laparoscopic surgery range from 15% to as high as 38% or higher, depending on the age of the patient and how well they do with general anesthesia (Vigneswaran et al, 2015; Neumayer et al, 2004; Perugini & Callery, 2001). Experienced surgeons who have done more than 250 laparoscopic surgeries have a lower complication rate. However, a 2011 Cochran review points out that there is theoretically a higher risk that intra-abdominal organs will be injured during a laparoscopic procedure (Sauerland, 2011). In addition, bilateral laparoscopic hernia repair has significantly higher risk than single sided laparoscopic hernia repair for post-operative urinary retention (Blair et al, 2016). My experience is not an outlier–it is more common.

- Inappropriate post-operative procedures. In my case I was released directly after waking up from general anesthesia without checking to determine whether I could urinate or not. The medical staff and facility should never have released me, since older males have a 30% or higher probability that urinary retention will occur after general anesthesia. However, it was a Friday afternoon and the staff probably wanted to go home since the facility closes at 5:30 pm. This landed me in the Emergency Room.

- Medical negligence. In my case the surgeon recommended that I have my bladder in the emergency room emptied and then go home. That was not sufficient, and my body still was not working properly, requiring a second visit to the ER and the insertion of a Foley catheter. Following the second ER visit, the surgeon removed the catheter in his office in the late afternoon and did not check to determine whether I could urinate or not. This resulted in a third ER visit.

- Medical error. On my third visit to the emergency room, the nurse made the error of inflating the Foley catheter balloon when it was in the urethra (rather than the bladder) which caused tearing and bleeding of the urethra and possible irritation to the prostate.

- Drawbacks of the ER as the primary resource for post-surgical care. Care is not scheduled for the patient’s needs, but rather based on a triage system. In my case I had to wait sometimes two hours or more until a catheter could be inserted. The wait kept increasing the urine volume which expanded and irritated the bladder further.

- A medical system that does not track treatment outcomes. Without good follow-up and long-term data, no one is accountable or responsible.

- A reimbursement system that rewards lower up-front costs. The system favors quick outpatient surgeries without factoring in the long-term costs and harm of the type I experienced.

Assuming the best and not planning for the worst.

Can I trust the health care provider’s statement that the procedure is low risk and that the recovery will go smoothly?