Reduce Interpersonal Stress*

Posted: December 4, 2025 Filed under: attention, behavior, Breathing/respiration, CBT, emotions, Exercise/movement, healing, health, meditation, mindfulness, Pain/discomfort, stress management | Tags: health, mental-health, nutrition, wellness 3 CommentsAdapted from: Peper, E. & Harvey, R. Adjunctive techniques to reduce interpersonal stress at home. Biofeedback. 53(3), 54-57. https://rdcu.be/eMJqt

Stress often triggers defensive reactions—manifesting as anger, frustration, or anxiety that may mirror fight-or-flight responses. These reactions can reduce rational thinking, increase long-term health risks, and contribute to psychological and physiological disorders. and complicate the management of specific symptoms. Outlined are some pragmatic techniques that can be implemented during the day to interrupt and reduce stress.

After we had been living in our house for a few years, a new neighbor moved in next door. Within months, she accused us of moving things in her yard, blamed us when there was a leak in her house, claimed we were blowing leaves from her property onto other neighbors’ properties, and even screamed at her tenants to the extent that the police were called numerous times. Just looking at her house through the window was enough to make my shoulders tighten and leave me feeling upset.

When I drove home and saw her standing in front of her house, I would drive around the block one more time to avoid her while . . . feeling my body contract. Often, when I woke up in the morning, I would already anticipate conflict with my neighbor. I would share stories of my disturbing neighbor and her antics with my friends. They were very supportive and agreed with me that she was crazy. However, the acknowledgment and validation from my friends did not resolve my anger or indignation or the anxiety that was triggered whenever I saw my neighbor or thought of her. I spent far too much time anticipating and thinking about her, which resulted in tension in my own body—my heart rate would increase, and my neck and shoulders would tighten.

I decided to change. I knew I could not change her; however, I could change my reactivity and perspective. Thus, I practiced a “pause and recenter” technique. At the first moment of awareness that I was thinking about her or her actions, I would change my posture by sitting up straight, begin looking upward, breathe lower and slower, and then, in my mind’s eye, send a thought of goodwill streaming to her like an ocean wave flowing through and around her in the distance. I chose to do this series of steps because I believe that within every person, no matter how crazy or cruel, there is a part that is good, and it is that part I want to support.

I repeated this pause and recenter technique many times, especially whenever I looked in the direction of her house or saw her in her yard. I also reframed and reappraised her aggressive, negative behavior as her way of coping with her own demons. Three months later, I no longer reacted defensively. When I see her, I can say hello and discuss the weather without triggering my defensive reaction. I feel so much more at peace living where I am.

When stressed, angry, rejected, frustrated, or hurt, we so often blame the other person (Leary, 2015). The moment we think about that person or event, our anger, indignation, resentment, and frustration are triggered. We keep rehashing what happened. As we relive the experiences in our mind, we are unaware that we are also reliving bodily reactions to past events.

We are often unaware of the harm we are doing to ourselves until we experience physical symptoms such as high blood pressure, gastrointestinal distress, and muscle tightness along with behavioral and psychological symptoms such as insomnia, anxiety, or depression (Carney et al., 2006; Gerin et al., 2012). As we think of past events or interact again with a person involved in those past events, our body automatically responds with a defense reaction as if we were being threatened again in the present moment.

This defense reaction to memory of past threats from a “crazy” neighbor activates our fight-or-flight responses and increases sympathetic activation so that we can run faster and fight more ferociously to survive; however, this reaction also reduces blood flow through the frontal cortex—a process that reduces our ability to think rationally (van Dinther et al., 2024; Willeumier, et al., 2011). When we become so upset and stressed that our mind is captured by the other person, this reaction contributes to symptoms of chronic stress such as an increase in hypertension, myofascial pain, depression, insomnia, cardiovascular disease, and other chronic disorders (Duan et al., 2022; Russell et al., 2015; Suls, 2013).

Sharing our frustrations with friends and others is normal. It feels good to blame people for their personal limitations or mental illness; however, over time, blaming others avoids building adaptive capacity in strengthening skills that reduce chronic stress reactions (Fast & Tiedens, 2010; Lou et al., 2023). The time spent rehashing and justifying our feelings diminishes the time we spend in the present moment and our focus on upcoming opportunities.

In the moment of an encounter with a difficult neighbor, we may not realize that we have a choice. Some people keep living and reacting to past hurts or losses perpetually. Some people can learn to let go and/or forgive and make space in favor of considering new opportunities for learning and growth. Although the choice is ours, it is often very challenging to implement—even with the best intentions—because we react automatically when reminded of past hurts (seeing that person, anticipating meeting or actually meeting that person who caused the hurt, or being triggered by other events that evoke memories of the pain).

What Can You Do

Choose to change your response. Choose to reduce reactivity. Choosing adaptive reactions does not mean you condone what happened or agree that the other person was right. You are just choosing to live your life and not continue to be captured by nor react to the previous triggers. Many people report that after implementing some of the practices described below along with many other stress management techniques, their automatic reactivity was noticeably decreased. They report that their chronic stress symptoms were reduced and they have the freedom to live in present instead of being captured by the painful past.

Pause and Recenter by Sending Goodwill

Our automatic reaction to the trigger elicits a defense reaction that reduces our ability to think rationally. Therefore, the moment you anticipate or begin to react, take three very slow diaphragmatic breaths, inhaling for approximately 4–5 seconds and exhaling for about 5–6 seconds, where one in-and-out breath takes about 10 seconds to complete. As you inhale, allow your abdomen to expand; then as you exhale, slowly make yourself tall and look up. Looking up allows easier access to empowering and positive memories (Peper et al., 2017).

Continue looking up, inhaling slowly to allow the abdomen to expand. Repeat this slow breath again. On the third long, slow breath, while looking up, evoke a memory of someone in whose presence you felt at peace and who loves you, such as your grandmother, aunt, uncle, or even a pet. Reawaken positive feelings associated with memories of being loved. Allow a smile inwardly or outwardly and soften your eyes as you experience the loving memory.

Next, put your hands on your chest, take another long slow breath as your abdomen expands, and as you exhale bring your hands away from your chest and stretch them out in front of you. At the same time in your mind’s eye, imagine sending goodwill to that person involved in the interpersonal conflict that previously evoked your stress response. As if you are sending an ocean wave that is streaming outward to the person.

As you do the pause and recenter technique, remember you are not condoning what happened; instead, you are sending goodwill to that person’s positive aspect. From this perspective, everyone has an intrinsic component—however small—that some label as the individual’s human potential, Christ nature or Buddha nature.

Why would this be effective? This practice short-circuits the automatic stress response and provides time to recenter, interrupting ongoing rumination by shifting the mind away from thoughts about the person or event that induced stress toward a positive memory. By evoking a loving memory from the past, we facilitate a reduction in arousal, evoke a positive mood, and decrease sympathetic nervous system activation (Speer & Delgado, 2017). Slower diaphragmatic breathing also reduces sympathetic activation (Birdee et al., 2023; Siedlecki et al., 2022). By combining body-centered and mind-centered techniques, we can pause and create the opportunity to respond positively rather than reacting with anger and hurt.

Practice Sending Goodwill the Moment You Wake Up

So often when we wake up, we anticipate the challenges, and even the prospect of interacting with a person or event heightens our defense reaction. Therefore, as soon as you wake up, sit at the edge of the bed, repeat the previous practice, pause, and center. Then, as you sit at the edge of the bed, slightly smile with soft eyes, look up, and inhale as your abdomen expands. Then, stamp a foot into the floor while saying, “Today is a new day.” Next, inhale, allowing your abdomen to expand; as you look up, stamp the opposite foot on the floor while saying, “Today is a new day.” Finally, send goodwill to the person who previously triggered your defensive reaction.

Why would this be effective? Looking up makes it easier to access positive memories and thoughts. Stamping your foot on the ground is a nonverbal expression of determination and anchors the thought of a new day, thereby focusing on new opportunities (Feldman, 2022).

Interrupt the Stress Response with the ABCs

The moment you notice discomfort, pain, stress, or negative thoughts, interrupt the cycle with a simple ABC strategy (Peper, 2025):

- Adjust posture and look up

- Breathe by allowing your abdomen to relax and expand while inhaling

- Change your internal dialogue, smile and focus on what you want to do

Why would this be effective? By shifting your posture and gently looking upward, you make it easier to access positive and empowering memories and thoughts (Peper et al., 2019). This simple change in body position can interrupt habitual stress responses and open the doorway to more constructive states.

Slow, diaphragmatic breathing further supports this process by reducing sympathetic arousal and restoring a sense of calm. As your breathing deepens, clarity of mind increases, allowing you to respond rather than react (Peper et al, 2024b; Matto et al, 2025).

Equally important is transforming critical, judgmental, or negative self-talk into affirmative, supportive statements. Describe what you want to do—rather than what you want to avoid. This reframing creates a clear internal guide and significantly increases the likelihood that you will achieve your desired goals.

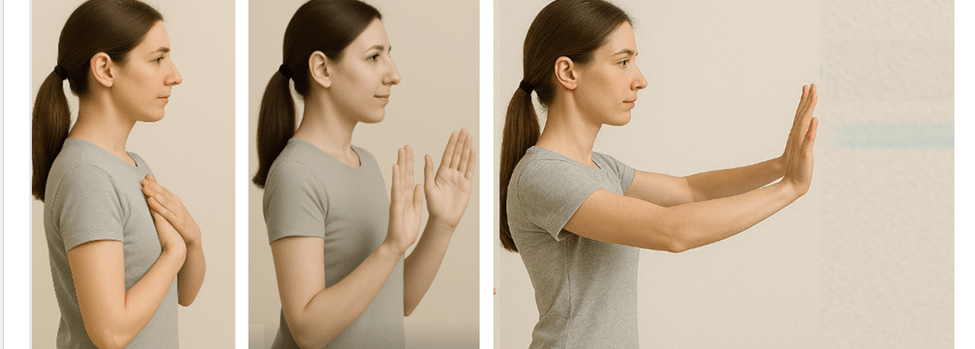

Complete the Alarm Reaction a Burst of Physical Activity

When you feel overwhelmed and fully captured by a stress reaction, one of the most effective strategies is to complete the fight-flight response with a brief burst of intense physical activity. This momentary action such as running in place, vigorously shaking your arms, or doing a few rapid push-offs from a wall (Peper et al., 2024a). After completing the physical activity implement your stress management strategies such as breathing, cognitive reframing, meditation, etc.

Why would this be effective? The intense physical activity discharges the excessive physiological arousal and interrupts the cycle of rumination. For practical examples and step-by-step guidance, see the article Quick Rescue Techniques When Stressed (Peper et al., 2024a) or the accompanying blog post: https://peperperspective.com/2024/02/04/quick-rescue-techniques-when-stressed/

Discuss Your Issue from the Third-Person Perspective

When thinking, ruminating, talking, texting, or writing about the event, discuss it from the third-person perspective. Replace the first-person pronoun “I” with “she” or “he.” For example, instead of saying “I was really pissed off when my boss criticized my work without giving any positive suggestions for improvement,” say “He was really pissed off when his boss criticized his work without offering any positive suggestions for improvement.”

Why would this be effective? The act of substituting the third-person pronoun for the first-person pronoun interrupts our automatic reactivity because it requires us to observe and change our language, which activates parts of the frontal cortex. This third-person/first-person process creates a psychological distance from our feelings, allowing for a more objective and calmer perspective on the situation, effectively reducing stress by stepping back from the immediate emotional response (Moser et al., 2017). This process can be interpreted as meaning that you are no longer fully captured by the emotions, as you are simultaneously the observer of your own inner language and speech.

Compare Yourself with Others Who are less Fortunate

When you feel sorry for yourself or hurt, take a breath, look upward, and compare yourself with others who are suffering much more. In that moment, consider yourself incredibly lucky compared with people enduring extreme poverty, bombings, or severe disfigurement. Be grateful for what you have.

Why would this be effective? Research shows that when we compare ourselves with people who are more successful, we tend to feel worse—especially when we have low self-esteem. However, when we compare ourselves with others who are suffering more, we tend to feel better (Aspinwall, & Taylor, 1993). This comparison relativizes our perspective on suffering, making our own hardships and suffering seem less significant compared with the severe suffering of others.

Conclusion

It is much easier to write and talk about these practices than to implement them. Reminding yourself to implement them can be very challenging. It requires significant effort and commitment. In some cases, the benefits are not experienced immediately; however, when practiced many times during the day for six to eight weeks, many people report feeling less resentment and experience a reduction in symptoms and improvements in health and relationships.

*This blog was inspired by the podcast “No Hard Feelings,” an episode on Hidden Brain produced by Shankar Vedantam (2025) that featured psychologist Fred Luskin, and the wisdom taught by Dora Kunz (Kunz & Peper, 1983, 1984a, 1984b, 1987).

See the following posts for more relevant information

References

Aspinwall, L. G., & Taylor, S. E. (1993). Effects of social comparison direction, threat, and self-esteem on affect, self-evaluation, and expected success. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(5), 708–722. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.64.5.708

Birdee, G., Nelson, K.,Wallston, K., Nian, H., Diedrich, A., Paranjape, S., Abraham, R., & Gamboa, A. (2023). Slow breathing for reducing stress: The effect of extending exhale. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2023.102937

Carney, C. E., Edinger, J. D., Meyer, B., Lindman, L., & Istre, T. (2006). Symptom-focused rumination and sleep disturbance. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 4(4), 228–241. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15402010bsm0404_3

Defayette, A. B., Esposito-Smythers, C., Cero, I., Harris, K. M.,Whitmyre, E. D., & López, R. (2023). Interpersonal stress and proinflammatory activity in emerging adults with a history of suicide risk: A pilot study. Journal of Mood and Anxiety Disorders, 2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xjmad.2023.100016

Dienstbier, R. A. (1989). Arousal and physiological toughness: Implications for mental and physical health. Psychological Review, 96(1), 84. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-95x.96.1.84

Duan, S., Lawrence, A., Valmaggia, L., Moll, J., & Zahn, R. (2022). Maladaptive blame-related action tendencies are associated with vulnerability to major depressive disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 145, 70–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.11.043

Fast, N. J., & Tiedens, L. Z. (2010). Blame contagion: The automatic transmission of self-serving attributions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46(1), 97–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.10.007

Feldman, Y. (2022). The dialogical dance–A relational embodied approach to supervision. In C. Butte & T. Colbert (Eds.), Embodied approaches to supervision: The listening body (chap. 2). Routledge. https://www.amazon.com/Embodied-Approaches-Supervision-C%C3%A9line-Butt%C3%A9/dp/0367473348

Gerin,W., Zawadzki,M. J., Brosschot, J. F., Thayer, J. F., Christenfeld, N. J., Campbell, T. S., & Smyth, J. M. (2012). Rumination as a mediator of chronic stress effects on hypertension: A causal model. International Journal of Hypertension, 2012, 453465. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/453465

Hase, A., O’Brien, J., Moore, L. J., & Freeman, P. (2019). The relationship between challenge and threat states and performance: A systematic review. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 8(2), 123. https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000132

Hassamal, S. (2023). Chronic stress, neuroinflammation, and depression: An overview of pathophysiological mechanisms and emerging anti-inflammatories. Frontiers in Psychiatry,

14, 1130989. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1130989

Kunz, D., & Peper, E. (1983). Fields and their clinical implications—Part III: Anger and how it affects human interactions. The American Theosophist, 71(6), 199–203. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280777019_Fields_and_their_clinical_implications-Part_III_Anger_and_how_it_affects_human_interactions

Kunz, D., & Peper, E. (1984a). Fields and their clinical implications IV: Depression from the energetic perspective: Etiological underpinnings. The American Theosophist, 72(8), 268–275. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280884054_Fields_and_their_clinical_implications_Part_IV_Depression_from_the_energetic_perspective-Etiological_underpinnings

Kunz, D., & Peper, E. (1984b). Fields and their clinical implications V: Depression from the energetic perspective: Treatment strategies. The American Theosophist, 72(9), 299–306. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280884158_Fields_and_their_clinical_implications_Part_V_Depression_from_the_energetic_perspective-Treatment_strategies

Kunz, D., & Peper, E. (1987). Resentment: A poisonous undercurrent. The Theosophical Research Journal, IV(3), 54–59. Also in: Cooperative Connection, IX(1), 1–5. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/387030905_Resentment_Continued_from_page_4

Leary, M. R. (2015). Emotional responses to interpersonal rejection. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 17(4), 435–441. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2015.17.4/mleary

Lou, Y., Wang, T., Li, H., Hu, T. Y., & Xie, X. (2023). Blame others but hurt yourself: Blaming or sympathetic attitudes toward victims of COVID-19 and how it alters one’s health status. Psychology & Health, 39(13), 1877–1898. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2023.2269400

Matto, D., Peper, E., & Harvey, R. (2025). Monitoring and coaching breathing patterns and rate. Townsend Letter-Innovative Health Perspectives. https://townsendletter.com/monitoring-and-coaching-breathing-patterns-and-rate/

Moser, J. S., Dougherty, A., Mattson, W. I., Katz, B., Moran, T. P.,Guevarra, D., Shablack, H.,Ayduk,O., Jonides, J., Berman, M. G., & Kross, E. (2017). Third-person self-talk facilitates emotion regulation without engaging cognitive control: Converging evidence from ERP and fMRI. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 4519. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-04047-3

Peper, E. (2025). Breathe Away Menstrual Pain- A Simple Practice That Brings Relief. the peper perspective-ideas on illness, health and well-being from Erik Peper. https://peperperspective.com/2025/11/22/6825/

Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Hamiel, D. (2019). Transforming thoughts with postural awareness to increase therapeutic and teaching efficacy. NeuroRegulation, 6(3), 153-169. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.6.3.1533-1

Peper, E., Lin, I.-M., Harvey, R., & Perez, J. (2017). How posture affects memory recall and mood. Biofeedback, 45(2), 36–41. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-45.2.01

Peper, E., Oded, Y., & Harvey, R. (2024a). Quick somatic rescue techniques when stressed. Biofeedback, 52(1), 18–26. https://doi.org/10.5298/982312

Peper, E., Oded, Y., Harvey, R., Hughes, P., Ingram, H., & Martinez, E. (2024b). Breathing for health: Mastering and generalizing breathing skills. Townsend Letter-Innovative Health Perspectives. November 15, 2024. https://townsendletter.com/suggestions-for-mastering-and-generalizing-breathing-skills/

Russell, M. A., Smith, T. W., & Smyth, J. M. (2015). Anger expression, momentary anger, and symptom severity in patients with chronic disease. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 50(2), 259–271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-015-9747-7

Siedlecki, P., Ivanova, T. D., Shoemaker, J. K., & Garland, S. J. (2022). The effects of slow breathing on postural muscles during standing perturbations in young adults. Experimental Brain Research, 240, 2623–2631. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-022-06437-0

Speer, M. E., & Delgado, M. R. (2017). Reminiscing about positive memories buffers acute stress responses. Nature Human Behaviour, 1, 0093. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-017-0093

Suls, J. (2013). Anger and the heart: Perspectives on cardiac risk, mechanisms and interventions. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases, 55(6), 538–547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2013.03.002

van Dinther, M., Hooghiemstra, A. M., Bron, E. E., Versteeg, A., et al. (2024). Lower cerebral blood flow predicts cognitive decline in patients with vascular cognitive impairment. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, 20(1), 136–144. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.13408

Vedantam, S. (2025). No hard feelings. Hidden brain. Accessed February 5, 2025. https://hiddenbrain.org/podcast/no-hard-feelings/

Willeumier, K., Taylor, D. V., & Amen, D. G. (2011). Decreased cerebral blood flow in the limbic and prefrontal cortex using SPECT imaging in a cohort of completed suicides. Translational Psychiatry, 1(8), e28. https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2011.28

Zannas, A. S., & West, A. E. (2014). Epigenetics and the regulation of stress vulnerability and resilience. Neuroscience, 264, 157–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.12.003

Exploring the pain-brain-breathing connection

Posted: August 30, 2025 Filed under: attention, behavior, Breathing/respiration, cognitive behavior therapy, education, emotions, healing, meditation, Pain/discomfort, placebo, self-healing, Uncategorized | Tags: deliberate harm Leave a commentIf you’re curious about how the mind and body interplay in shaping pain—or looking for real, actionable techniques grounded in research listen to this episode of the Heart Rate Variability Podcast, Matt Bennett interviews Dr. Erik Peper about his article and blogpost Pain – There Is Hope. The conversation takes listeners beyond the common perception of pain as merely a physical response. It is a balanced mix of scientific depth and real-life applications, especially valuable for anyone interested in self-healing, holistic health, or understanding mind-body medicine. Moreover, it explains how pain is shaped by posture, breathing, mindset, and emotional context. Finally, it provides practical strategies to shift the pain experience, offering an uplifting and science-backed blend of understanding and hope.

If you find this helpful, let me know! And feel free to share it with friends and post it on your social channels so more people can benefit.

Blogs that complement this interview

If you want to explore further, check out the companion blog posts I hve created to expand on the themes from this discussion. These blogs highlight practical strategies, scientific insights, and everyday applications.

Use the power of your mind to transform health and aging

Posted: February 18, 2025 Filed under: attention, behavior, cancer, CBT, cognitive behavior therapy, COVID, education, health, meditation, mindfulness, Pain/discomfort, placebo, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: health, imimune function, longevity, mental-health, mind-body, nutrition, Reframing, wellness Leave a commentMost of the time when I drive or commute by BART, I listen to podcasts (e.g., Freakonomics, Hidden Brain, this podcast will kill you, Science VS, Huberman Lab). although many of the podcasts are highly informative; , rarely do I think that everyone could benefit from it. The recent podcast, Using your mind to control your health and longevity, is an exception. In this podcast, neuroscientist Andrew Huberman interviews Professor Ellen Langer. Although it is three hours and twenty-two minute long, every minute is worth it (just skip the advertisements by Huberman which interrupts the flow). Dr. Langer delves into how our thoughts, perceptions, and mindfulness practices can profoundly influence our physical well-being.

She presents compelling evidence that our mental states are intricately linked to our physical health. She discusses how our perceptions of time and control can significantly impact healing rates, hormonal balance, immune function, and overall longevity. By reframing our understanding of mindfulness—not merely as a meditative practice but as an active, moment-to-moment engagement with our environment—we can harness our mental faculties to foster better health outcomes. The episode also highlights practical applications of Dr. Langer’s research, offering insights into how adopting a mindful approach to daily life can lead to remarkable health benefits. By noticing new things and embracing uncertainty, individuals can break free from mindless routines, reduce stress, and enhance their overall quality of life. This podcast is a must-listen for anyone interested in the profound connection between mind and body. It provides valuable tools and perspectives for those seeking to take an active role in their health and well-being through the power of mindful thinking. It will change your perspective and improve your health. Listen to or watch the interview:

Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QYAgf_lfio4

Useful blogs to reduce stress

Compassionate Presence: Covert Training Invites Subtle Energies Insights

Posted: January 20, 2025 Filed under: attention, healing, meditation, mindfulness, relaxation, Uncategorized | Tags: being safe, compassion, energy, Energy healing, healing, reiki, spirituality, therapeutic touch Leave a commentAdapted from: Peper, E. (2015). Compassionate Presence: Covert Training Invites Subtle Energies Insights. Subtle Energies Magazine, 26(2), 22-25. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283123475_Compassionate_Presence_Covert_Training_Invites_Subtle_Energies_Insights

“Healing is best accomplished when art and science are conjoined, when body and spirit are probed together. Only when doctors can brood for the fate of a fellow human afflicted with fear and pain do they engage the unique individuality of a particular human being…a doctor thereby gains courage to deal with the pervasive uncertainties for which technical skill alone is inadequate. Patient and doctor then enter into a partnership as equals.

I return to my central thesis. Our health care system is breaking down because the medical profession has been shifting its focus away from healing, which begins with listening to the patient. The reasons for this shift include a romance with mindless technology.” Bernard Lown, MD, The Lost art of healing: Practicing Compassion in Medicine (1999)

Therapeutic Touch healing by Dora Kunz.

I wanted to study with the healer and she instructed me to sit and observe, nothing more. She did not explain what she was doing, and provided no further instructions. Just observe. I did not understand. Yet, I continued to observe because she knew something, she did something that seemed to be associated with improvement and healing of many patients. A few showed remarkable improvement – at times it seemed miraculous. I felt drawn to understand. It was an unique opportunity and I was prepared to follow her guidance.

The healer was remarkable. When she put her hands on the patient, I could see the patient’s defenses melt. At that moment, the patient seemed to feel safe, cared for, and totally nurtured. The patient felt accepted for just who she was and all the shame about the disease and past actions appeared to melt away. The healer continued to move her hands here and there and, every so often, she spoke to the client. Tears and slight sobbing erupted from the client. Then, the client became very peaceful and quiet. Eventually, the session was finished and the client expressed gratitude to the healer and reported that her lower back pain and the constriction around her heart had been released, as if a weight had been taken from her body.

How was this possible? I had so many questions to ask the healer: “What were you doing? What did you feel in your hands? What did you think? What did you say so softly to the client?”

Yet she did not help me understand how I could do this. The main instruction the healer kept giving me was to observe. Yes, she did teach me to be aware of the energy fields around the person and taught me how I could practice therapeutic touch (Kreiger, 1979; Peper, 1986; Kunz & Peper,1995; Kunz & Krieger, 2004; Denison, 2004; van Gelder & Chesley, F, 2015). But she was doing much more and I longed to understand more about the process.

Sitting at the foot of the healer, observing for months, I often felt frustrated as she continued to insist that I just observe. How could I ever learn from this healer if she did not explain what I should do! Does the learning occur by activating my mirror neurons (Acharya & Shukla, 2012).? Similar instructions are common in spiritual healing and martial arts traditions – the guru or mentor usually tells an apprentice to observe and be there. But how can one gain healing skills or spiritual healing abilities if you are only allowed to observe the process? Shouldn’t the healer be demonstrating actual practices and teaching skills?

After many sessions, I finally realized that the healer’s instruction to to learn was to observe and observe. I began to learn how to be present without judging, to be present with compassion, to be present with total awareness in all senses, and to be present without frustration. The many hours at the foot of this master were not just wasted time. It eventually became clear that those hours of observation were important training and screening strategies used to insure that only those students who were motivated enough to master the discipline of non-judgmental observation, the discipline to be present and open to any experience, would continue to participate in the training process. I finally understood. I was being taught a subtle energies skill of compassionate, and mindful awareness. Once I, the apprentice, achieved this state, I was ready to begin work with clients and master technical aspects of the healing practice – but not before.

A major component of the healing skill that relies on subtle energies is the ability to be totally present with the client without judgment (Peper, Gibney & Wilson, 2005). To be peaceful, caring, and present seems to create an energetic ambiance that sets stage, creates the space, for more subtle aspects of the healing interaction. This energetic ambiance is similar to feeling the love of a grandparent: feeling total acceptance from someone who just knows you are a remarkable human being. In the presence of a healer with such a compassionate presence, you feel safe, accepted, and engaged in a timeless state of mind, a state that promotes healing and regeneration as it dissolves long held defensiveness and fear-based habits of holding others at bay. This state of mind provides an opportunity for worries and unsettled emotions to dissipate. Feeling safe, accepted, and experiencing compassionate love supports the bological processes that nurture regeneration and growth.

How different this is from the more common experience with health care/medical practitioners who have little time to listen and to be with a patient. We might experience a medical provider as someone who sees us only as an illness (the cancer patient, the asthma patient) instead of recognizing us as a human spirit who happens to have an illness ( a person with cancer or asthma). At times we can feel as though we are seen only as a series of numbers in a medical chart – yet we know we are more than that. People long to be seen. Often the medical provider interrupts with unrelated questions instead of listening. It becomes clear that the computerized medical record is more important than the human being seated there. We can feel more fragmented, less safe, when we are not heard, not understood.

As one 23 year old student reported after being diagnosed with a serious medical condition,”/ cried immediately upon leaving the physician’s office. Even though he is an expert on the subject, I felt like I had no psychological support. I was on Gabapentin, and it made me very depressed. I thought to myself: Is my life, as I know it, over?” (Peper, Martinez Aranda, P., & Moss, 2015).

The healing connection is often blocked, the absence of a human connection is so obvious. The medical provider may be unaware of the effect of their rushed behavior and lack of presence. They can issue a diagnosis based on the scientific data without recognizing the emotional impact on the person receiving it.

What is missing is compassion and caring for the patient. Sitting at the foot of the master healer is not wasted time when the apprentice learns how to genuinely attend to another with non-judgmental, compassionate presence. However, this requires substantial personal work. Possibly all healthcare providers should be required, or at least invited, to learn how to attain the state of mind that can enhance healing. Perhaps the practice of medicine could change if, as Bernard Lown wrote, the focus were once again on healing, “…which begins with listening to the patient.”

References

Acharya, S., & Shukla, S. (2012). Mirror neurons: Enigma of the metaphysical modular brain. Journal of natural science, biology, and medicine, 3(2), 118–124. https://doi.org/10.4103/0976-9668.101878

Denison, B. (2004). Touch the pain away: New research on therapeutic touch and persons with fibromyalgia syndrome. Holistic nursing practice, 18(3), 142-151. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004650-200405000-00006

Krieger, D. (1979). The therapeutic touch: How to use your hands to help or to heal. Vol. 15. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. https://www.amazon.com/Therapeutic-Touch-Your-Hands-Help/dp/067176537X

Kunz, D. & Krieger, D. (2004). The spiritual dimension of therapeutic touch. Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions/Bear & Co. https://www.amazon.com/Spiritual-Dimension-Therapeutic-Touch/dp/1591430259/

Kunz, D., & Peper, E. (1995). Fields and their clinical implications. In Kunz, D. Spiritual Aspects of the Healing Arts. Wheaton, ILL: Theosophical Pub House, 213-222. https://www.amazon.com/Spiritual-Aspects-Healing-Arts-Quest/dp/0835606015

Lown, B. (1999). The lost art of healing: Practicing compassion in medicine. New York, NY: Ballantine Books. https://www.amazon.com/Lost-Art-Healing-Practicing-Compassion/dp/0345425979

Peper, E. (1986). You are whole through touch: An energetic approach to give support to a breast cancer patient. Cooperative Connection. VII (3), 1-6. Also in: (1986/87). You are whole through touch: Dora Kunz and Therapeutic Touch. Somatics. VI (1), 14-19. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280884245_You_are_whole_through_touch_Dora_Kunz_and_therapeutic_touch

Peper, E. (2024). Reflections on Dora and the Healing Process, webinar presented to the Therapeutic Touch International Association, Saturday, December 14, 2024. https://youtu.be/skq9Chn-eME?si=HJNAhiUsgXSkqd_5

Peper, E., Gibney, K. H. & Wilson, V. E. (2005). Enhancing Therapeutic Success–Some Observations from Mr. Kawakami: Yogi, Teacher, Mentor and Healer. Somatics. XIV (4), 18-21. https://biofeedbackhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/edited-enhancing-therapeutic-success-8-23-05.pdf

Peper, E., Martinez Aranda, P., & Moss, E. (2015). Vulvodynia treated successfully with breathing biofeedback and integrated stress reduction: A case report. Biofeedback, 43(2), 103-109. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-43.2.04

Van Gelder, K & Chesley, F. (2015). A Most Unusual Life. Wheaton Ill: Theosophical Publishing House. https://www.amazon.com/Most-Unusual-Life-Clairvoyant-Theosophist/dp/0835609367

[1] I thank Peter Parks for his superb editorial support.

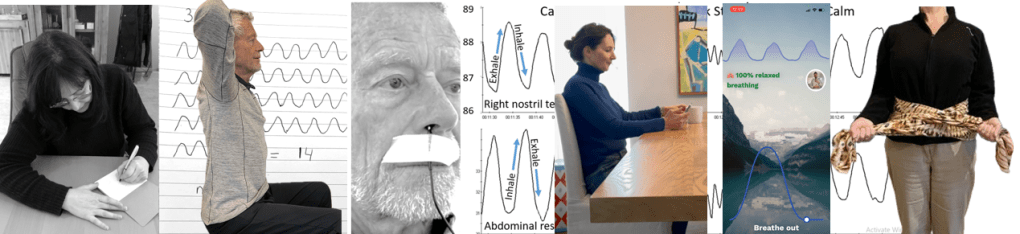

Pragmatic techniques for monitoring and coaching breathing

Posted: December 14, 2024 Filed under: attention, behavior, biofeedback, Breathing/respiration, emotions, meditation, mindfulness, neurofeedback, Pain/discomfort, posture, relaxation, self-healing, Uncategorized | Tags: art, books, Breathing rate, coaching, FlowMD app, nasal breathing, personal-development, self-monitoring, writing 4 CommentsDaniella Matto, MA, BCIA BCB-HRV , Erik Peper, PhD, BCB, and Richard Harvey, PhD

Adapted from: Matto, D., Peper, E., & Harvey, R. (2025). Monitoring and coaching breathing patterns and rate. Townsend Letter-Innovative Health Perspectives. https://townsendletter.com/monitoring-and-coaching-breathing-patterns-and-rate/

This blog aims to describe several practical strategies to observe and monitor breathing patterns to promote effortless diaphragmatic breathing. The goal of these strategies is to foster effortless, whole-body diaphragmatic breathing that promote health.

Breathing is usually covert and people are not usually aware of their breathing rate (breaths per minute) or pattern (abdominal or thoracic, breath holding or shallow breathing) unless they have an illness such as asthma, emphysema or are performing physical activity (Boulding et al, 2015)). Observing breathing is challenging; awareness of respiration often leads to unaware changes in the breath pattern or to an attempt to breathe perfectly (van Dixhoorn, 2021). Ideally breathing patterns should be observed/monitored when the person is unaware of their breathing pattern and the whole body participates (van Dixhoorn, 2008). A useful strategy is to have the person perform a task and then ask, “What happened to your breathing?”. For example, ask a person to simulate putting a thread through the eye of a needle or quickly look to the extreme right and left while keeping their head still. In almost all cases, the person holds their breath (Peper et al., 2002).

Teaching effortless slow diaphragmatic breathing is a precursor of Heart rate variability (HRV) biofeedback and is based on slow paced breathing (Lehrer & Gevirtz, 2014; Steffen et al., 2017; Shaffer and Meehan, 2020). Mastering effortless diaphragmatic breathing is a powerful tool in the treatment of a variety of physical, behavioural, and cognitive conditions; however, to integrate this method into clinical or educational practice is easier said than done. Clients with dysfunctional breathing patterns often have difficulty following a breath pacer or mastering effortless breathing at a slower pace.

The purpose of this paper is to describe a few simple strategies that can be used to observe and monitor breathing patterns, provide economic strategies for observation and training, and suggestions to facilitate effortless diaphragmatic breathing.

Strategies to observe and monitor breathing pattern

Observation of the breathing patterns

- Is the breathing through the nose or mouth? Nose is usually better (Watso et al., 2023; Nestor, 2020).

- Does the abdomen expand during inhalation and constricts during exhalation or does the chest expand and rise during inhalation and fall during exhalation? Abdominal movement is usually better.

- Is exhalation flow softly or explosively like a sigh? Slow flow exhalation is preferred.

- Is the breath held or continues during activities? In most cases continued breathing is usually better.

- Does the person gasp before speaking or allows to speak while normally exhaling?

- What is the breathing rate (breaths per minute)? When sitting peacefully less than 14 breaths/minute is usually better and about 6 breaths per minute to optimize HRV

Physiological monitoring.

- Monitoring breathing with strain gauges around the abdomen and chest, and heart rate is the most common approach to identify the location of breath, the breathing pattern and heart rate variability. The strain gauges are placed around the chest and abdomen and heart rate is monitored with a blood volume pulse amplitude sensor from the finger. representative recording shows the effect of thoughts on breathing, heartrate and pulse amplitude of which the participant is totally unaware as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Physiological recording of breathing patterns with strain gauges.

- Monitoring breathing with a thermistor placed at the entrance of the nostril that has the most airflow (nasal patency) (Jovanov et al., 2001; Lerman et al., 2016). When the person exhales through the nose, the thermistor temperature increases and decreases when they inhale. A representative recording of a person being calm, thinking a stressful thought. and being calm. Although there were significant changes as indicated by the change in breathing patterns, the person was unaware of the changes as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Use of a thermistor to monitor breathing from the dominant nostril compared to the abdominal expansion as monitored by a strain gauge around the abdomen.

- Additional physiological monitoring approaches. There are many other physiological measures can be monitored to such as end-tidal carbon dioxide (EtCO2), a non-invasive measurement of the amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) in exhaled breath (Meuret et al., 2008; Meckley, 2013); scalene/trapezius EMG to identify thoracic breathing (Peper & Tibbett, 1992; Peper & Tibbets, 1994); low abdominal EMG to identify transfers and oblique tightening during exhalation and relaxation during inhalation (Peper et al., 2016; and heart rate to monitor cardiorespiratory synchrony (Shaffer & Meehan, 2020). Physiological monitoring is useful; since, the clinician and the participant can observe the actual breathing pattern in real time, how the pattern changes in response the cognitive and physical tasks, and used for feedback training. The recorded data can document breathing problems and evidence of mastery.

The challenges of using physiological monitoring arethat the equipment may be expensive, takes skill to operate and interpret the data, and is usually located in the office and not at home.

Economic strategies for observation and training breathing

To complement the physiological monitoring and allow observations outside the office and at home, some of the following strategies may be used to observe breathing pattern (rate and expansion of the breath in the body), and suggestion to facilitate effortless diaphragmatic breathing. These exercises make excellent homework for the client. Practicing awareness and internal self-regulation by the client outside the clinic contributes enormously to the effect of biofeedback training (Wilson et al., 2023),

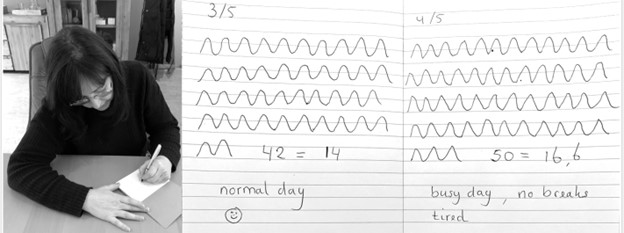

Observe breathing rate: Draw the breathing pattern

Take a piece of paper, a pen and a timer, set to 3 minutes. Start the timer. Upon inhalation draw the line up and upon exhalation draw the line down, creating a wave. When the timer stops, after 3 minutes, calculate the breathing rate per minute by dividing the number of waves by 3 as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Drawing the breathing pattern for three minutes during two different days.

From these drawings, the breathing rate become evident. Many individuals are often surprised to discover that their breathing rate increased during periods of stress, such as a busy day with no breaks, compared to their normal days.

Monitoring and training diaphragmatic breathing

The scarf technique for abdominal feedback

Many participants are unaware that they are predominantly breathing in their chest and their abdomen expansion is very limited during inhalation. Before beginning, have participant loosen their belt and or stand upright since sitting collapsed/slouched or having the waist constriction such as a belt of tight constrictive clothing that inhibits abdominal expansion during inhalation.

Place the middle part of a long scarf or shawl on your lower back, take the ends in both hands and cross the ends: your left hand is holding the right part of the scarf, and the right hand is holding the left end of the scarf. Give a bit of a pull, so you can feel any movement of the scarf. When breathing more abdominally you will feel a pull at the ends of the scarf as you lower back, and flanks will expand as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Using a scarf as feedback.

FlowMD app

A recent cellphone app, FlowMD, is unique because it uses the cellphone camera to detect the subtle movements of the chest and abdomen (FlowMD, 2024). It provides real time feedback of the persons breathing pattern. Using this app, the person sits in front of their cellphone camera and after calibration, the breathing pattern is displayed as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Training breathing with FlowMD,.

Suggestions to optimize abdominal breathing that may lead to a slower breath rate when the client practices the technique

Beach pose

By locking the upper chest and sitting up straight it is often easier to breathe so that the abdomen can expand and constrict. Place your hands behind your head and Interlock your finger of both hands, pull your elbows back and up. The person can practice this either laying down on their back or sitting straight up at the edge of the chair as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Sitting erect with the shoulders pulled back and up to allow abdominal expansion and constriction as the breathing pattern.

Observe the effect of posture on breathing

Have the person sit slouched/collapsed like a letter C and take a few slow breath, then have them sit up in a tall and erect position and take a few slow breaths. Usually they will observe that it is easier to breathe slower and lower and tall and erect.

Using your hands for feedback to guide natural breathing

Holding your hands with index fingers and thumbs touching the lower abdomen. When inhaling the fingers and thumbs separate and when exhaling they touch again (ensuring a full exhale and avoiding over breathing). The slight increase in lower abdominal muscle tension during the exhalation and relaxation during inhalation and the abdominal wall expands can also be felt with fingertips as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Using your hands and finger for feedback to guide the natural breathing of expansion and constriction of the abdomen. Reproduced by permission from Peper, E., Booiman, A., Lin, I-M, Harvey, R., & Mitose, J. (2016). Abdominal SEMG Feedback for Diaphragmatic Breathing: A Methodological Note. Biofeedback. 44(1), 42-49.

Coaching suggestions

There are many strategies to observe, teach and implement effortless breathing (Peper et al., 2024).. Even though breathing is natural and babies and young children breathe diaphragmatically as their large belly expands and constricts. Yet, in many cases the natural breathing shifts to dysfunctional breathing for multiple reasons such as chronic triggering defense reactions to avoiding pain following abdominal surgery (Peper et al, 2015). When participants initially attempt to relearn this natural pattern, it can be challenging especially, if the person habitually breathes shallowly, rapidly and predominantly in their chest.

When initially teaching effortless breathing, have the person exhale more air than normal without the upper chest compressing down and instead allow the abdomen comes in and up thereby exhaling all the air. If the person is upright then allow inhalation to occur without effort by letting the abdominal wall relaxes and expands. Initially inhale more than normal by expanding the abdomen without lifting the chest. Then exhale very slowly and continue to breathe so that the abdomen expands in 360 degrees during inhalation and constricts during exhalation. Let the breathing go slower with less and less effort. Usually, the person can feel the anus dropping and relaxing during inhalation.

Another technique is to ask the person to breathe in more air than normal and then breathe in a little extra air to completely fill the lungs, before exhaling fully. Clients often report that it teaches them to use the full capacity of the lungs.

The goal is to breath without effort. Indirectly this can be monitored by finger temperature. If the finger temperature decreases, the participant most likely is over-breathing or breathing with too much effort, creating sympathetic activity; if the finger temperature increases, breathing occurs slower and usually with less effort indicating that the person’s sympathetic activation is reduced.

Conclusion

There are many strategies to monitor and coach breathing. Relearning diaphragmatic breathing can be difficult due to habitual shallow chest breathing or post-surgical adaptations. Initial coaching may involve extended exhalations, conscious abdominal expansion, and gentle inhalation without chest movement. Progress can be monitored through indirect physiological markers like finger temperature, which reflects changes in sympathetic activity. The integration of these techniques into clinical or educational practice enhances self-regulation, contributing significantly to therapeutic outcomes. In this article we provided a few strategies which may be useful for some clients.

Additional blogs on breathing

https://peperperspective.com/2015/09/25/resolving-pelvic-floor-pain-a-case-report/

REFERENCES

Boulding, R., Stacey, R., & Niven, N. (2016). Dysfunctional breathing: a review of the literature and proposal for classification. European Respiratory Review, 25(141),: 287-294. https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0088-2015

FlowMD. (2024). FlowMD app. Accessed December 13, 2024. https://desktop.flowmd.co/

Jovanov, E., Raskovic, D., & Hormigo, R. (2001). Thermistor-based breathing sensor for circadian rhythm evaluation. Biomedical sciences instrumentation, 37, 493–497. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11347441/

Lehrer, P. & Gevirtz R. (2014). Heart rate variability biofeedback: how and why does it work? Front Psychol, 5,756. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00756

Lerman, J., Feldman, D., Feldman, R. et al. Linshom respiratory monitoring device: a novel temperature-based respiratory monitor. (2016). Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth, 63, 1154–1160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-016-0694-y

Meckley, A. (2013). Balancing Unbalanced Breathing: The Clinical Use of Capnographic Biofeedback. Biofeedback, 41(4), 183–187. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-41.4.02

Meuret, A. E., Wilhelm, F. H., Ritz, T., & Roth, W. T. (2008). Feedback of end-tidal pCO2 as a therapeutic approach for panic disorder. Journal of psychiatric research, 42(7), 560–568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.06.005

Nestor, J. (2020). Breath: The New Science of a Lost Art. New York: Riverhead Books. https://www.amazon.com/Breath-New-Science-Lost-Art/dp/0735213615/

Peper, E., Booiman, A., Lin, I-M, Harvey, R., & Mitose, J. (2016). Abdominal SEMG Feedback for Diaphragmatic Breathing: A Methodological Note. Biofeedback. 44(1), 42-49. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-44.1.03

Peper, E., Gilbert, C.D., Harvey, R. & Lin, I-M. (2015). Did you ask about abdominal surgery or injury? A learned disuse risk factor for breathing dysfunction. Biofeedback. 34(4), 173-179. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-43.4.06

Peper, E., Gibney, K.H., & Holt, C.F. (2002). Make Health Happen. Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company. https://he.kendallhunt.com/product/make-health-happen-training-yourself-create-wellness

Peper, E., Oded, Y., Harvey, R., Hughes, P., Ingram, H., & Martinez, E. (2024). Breathing for health: Mastering and generalizing breathing skills. Townsend Letter-Innovative Health Perspectives. November 15, 2024. https://townsendletter.com/suggestions-for-mastering-and-generalizing-breathing-skills/

Peper, E., & Tibbetts, V. (1992). Fifteen-month follow-up with asthmatics utilizing EMG/incentive inspirometer feedback. Biofeedback and self-regulation, 17(2), 143–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01000104

Peper, E. & Tibbetts, V. (1994). Effortless diaphragmatic breathing. Physical Therapy Products. 6(2), 67-71. https://biofeedbackhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/peper-and-tibbets-effortless-diaphragmatic.pdf

Shaffer, F. and Meehan, Z.M. (2020). A Practical Guide to Resonance Frequency Assessment for Heart Rate Variability Biofeedback. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 14. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnins.2020.570400

Steffen, P.R., Austin, T., DeBarros, A., and Brown, T. (2017). The Impact of Resonance Frequency Breathing on Measures of Heart Rate Variability, Blood Pressure, and Mood. Front Public Health, 5, 222. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00222

van Dixhoorn, J.V. (2008). Whole-body breathing. Biofeedback, 36,54–58. https://www.euronet.nl/users/dixhoorn/L.513.pdf

van Dixhoorn, J.V. (2021). Functioneel ademen-Adem-en ontspannings oefeningen voor gevorderden. Amersfoort: Uiteveriy Van Dixhoorn. https://www.bol.com/nl/nl/p/functioneel-ademen/9300000132165255/

Watso, J. C., Cuba, J.N., Boutwell, S.L, Moss, J…(2023). Acute nasal breathing lowers diastolic blood pressure and increases parasympathetic contributions to heart rate variability in young adults. American Journal of Physiology Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology.

325I(6), R797-R80. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.00148.2023

Wilson, V., Somers, K. & Peper, E. (2023). Differentiating Successful from Less Successful Males and Females in a Group Relaxation/Biofeedback Stress Management Program. Biofeedback, 51(3), 53–67. https://doi.org/10.5298/608570

[1] Correspondence should be addressed to:

Erik Peper, Ph.D., Institute for Holistic Health Studies, San Francisco State University, 1600 Holloway Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94132 Tel: 415 338 7683 Email: epeper@sfsu.edu web: www.biofeedbackhealth.org blog: www.peperperspective.com

360-Degree Belly Breathing with Jamie McHugh

Posted: April 26, 2024 Filed under: attention, Breathing/respiration, emotions, healing, health, meditation, mindfulness, Pain/discomfort, relaxation, self-healing | Tags: abdominal braething, belly breathing, daiphragm, effortless breathing, passive attention, self-acceptance, somatic awreness 4 Comments

Breathing is a whole mind-body experience and reflects our physical, cognitive and emotional well-being. By allowing the breath to occur effortlessly, we provide ourselves the opportunity to regenerate. Although there are many directed breathing practices that specifically directs us to inhale or exhale at specific rhythms or depth to achieve certain goals, healthy breathing is whole body experience. Many focus on being paced at a specific rhythm such as 5.5 breath per minute; however, effortless breathing is dynamic and constantly changing. It is contstantly adapting to the body’s needs: sometimes the breath is slightly slower, sometimes slightly faster, sometimes slightly deeper, sometimes slightly more shallower. The breathing process is effortless. This process can be described by the Autogenic training phrase, “It breathes me” (Luthe, 1969; Luthe, 1979; Luthe & de Rivera, 2015). Read the essay by Jamie McHugh, Registered Master Somatic Movement Therapist and then let yourself be guided in this non-striving somatic approach to allow effortless 360 degree belly breathing for regeneration.

The 360 degree belly breathing by Jamie McHugh, MSMT, is a somatic exploration to experience that breathing is not just abdominal breathing by letting the belly expand forward, but a rhythmic 360 degree increase and decrease in abdominal volume without effort. This effortless breathing pattern can often be observed in toddlers when they sit peacefully erect on the floor. This pattern of breathing not only enhances gas exchange, more importantly, it enhances abdominal blood and lymph circulation.

“The usual psychodynamic foundation for the self-experience is that of hunger, not breath. The body is experienced as an alien entity that has to be kept satisfied; the way an anxious mother might experience a new baby. When awareness is shifted from appetite to breath, the anxieties about not being enough are automatically attenuated. It requires a settling down or relaxing into one’s own body. When this fluidity moves to the forefront of awareness…there is a relaxation of the tensed self…and the emergence of a simpler, breath-based self that is capable of surrender to the moment.” – Mark Epstein (2013).

The intention behind 360 Degree Belly Breathing is to access and express the movement of the breath in all three dimensions. This is the basis for all subsequent somatic explorations within the Embodied Mindfulness protocol, a body-based approach to traditional meditation practices I have developed over the past 20 years (McHugh, 2016). Embodied Mindfulness explores the inner landscape of the body with the essential somatic technologies of breath, vocalization, self-contact, stillness and subtle movement. We focus and sustain mental attention while pleasurably cultivating bodily calm and clarity as a daily practice for survival in these turbulent times. Coupled with individual variations and experimentation, this practice becomes a reliable sanctuary from overwhelm, scattered attention, and emotional turmoil.

The Central Diaphragm

The central diaphragm, a dome-shaped muscular sheath that divides the thorax (chest) and the abdomen (belly), is the primary mechanism for breathing. It is the floor for your heart and lungs and the ceiling for your belly. The central diaphragm is a mostly impenetrable divide, with a few openings through it for the aorta, vena cava and the esophagus. Each time you inhale, the diaphragm contracts and flattens out a bit as it presses down towards your pelvis. Each time you exhale, the diaphragm relaxes and floats back up towards your heart. The motion of the diaphragm impacts the barometric pressure in your chest: the downward movement of the diaphragm on the inhale pulls oxygen into your lungs, and the subsequent exhale expels carbon dioxide into the world as the diaphragm releases upwards.

The movement of the diaphragm is twofold: involuntary and voluntary. Involuntary, ordinary breathing is a homebase and a point of return. Breathing just automatically happens – you don’t have to think about it. Breathing is also voluntary; you can choose to change the tempo (quick or slow), the duration (short or long) and quality (smooth or sharp) of this movement to “charge up and chill out” at will. Knowing how to collaborate with your diaphragm, discovering your own rhythm of diaphragmatic action, and undulating between the automatic and the chosen is a foundation for physiological equilibrium and emotional “self-soothing”.

Watch these two brief videos to get a visual image of your diaphragm in motion:

Beginning Sitting Practice

“When your back becomes straight, your mind will become quiet.” – Shunryu Suzuki

What does it mean to have a “straight back”? What are the inner coordinates and outer parameters of this position in space? And what kind of environment is needed to support this uprightness? This simple orientation to sitting can create more comfort, ease and support in your structure, which will stimulate more fluidity in your breathing and your thinking.

As you sit on a chair, consider two points of focus: body and environment. Can I sit upright with ease and comfort on this chair? If not, what changes can I make with my body and how can I adapt the environment of this chair to meet my needs? Since we are all various heights, it is not surprising a one-size-fits-all chair would need adaptation. Don’t be content with your first solution – experiment until you find just the right configuration. Valuing and seeking bodily comfort and ease are simple yet profound acts of self-kindness.

Do you need to move your pelvis forward on the chair or back? If you move your pelvis back, do you get the necessary support from the back of the chair for your pelvic bowl? If the back of the chair is too far away and/or makes you lean back into space, place a small cushion or two between the back of the chair and the base of your spine. With your back supported, are your feet on the floor? If not, place a folded blanket or a cushion under them.

With pelvis and feet in place, take a few full breaths to stabilize your pelvis and let your weight drop down through your sitz bones into the chair. The upper body receives more support from the core muscles of the lower body when your center of gravity drops – you don’t have to work so hard to maintain uprightness. Finally, rock on your sitz bones forward, backward, and side-to-side. Movement awakens bodily feedback so you can feel where center is in this moment. That sense of center will continue to change throughout the duration of the practice period so feel free to periodically adjust your position.

After this initial structural orientation, the next step is attending to the combination of breath and self-contact to fill out our self-perception. Self-contact is like using a magnifying glass – focusing the mind by feeling the substance of the belly’s movement in our hands. Since the diaphragm is a 360-degree phenomenon that generates movement in our sides and our back as well as our front, spreading awareness out not only creates different patterns of muscular activation – it also changes the brain’s map of the body and how we perceive ourselves. This change of orientation over time recalibrates our alignment and how we settle in ourselves, with awareness of our back in equal proportion to our front and sides.

360-Degree Belly Breath

“To stop your mind does not mean to stop the activities of the mind. It means your mind pervades your whole body.” – Shunryu Suzuki

Read text below or be guided by the audio file or YouTube video. http://somaticexpression.com/classes/360DegreeBreathingwithJamieMcHugh.mp3

Sit comfortably and place your hands on the front of your belly. With each inhale, become aware of the forward movement of your belly swelling. Then, with each exhale, notice the release of your belly and the settling back to center. Give this action and each subsequent action at least 5-7 breath cycles. Intersperse this way of breathing with ordinary, effortless breathing by letting the body breathe automatically. Return time and again to ordinary breathing, letting go of the focus and the effort to rest in the aftermath.

Now, slide your hands to the sides of your belly. Notice with each breath cycle how your belly moves laterally out to the sides on the inhale and then settles back to center again on the exhale.

Now, slide your hands to the back of your belly. You may wish to make contact with the back of your hands instead of your palms if it is more comfortable. With each inhale, focus on the movement into the backspace – this will be much smaller than the movement to the front; and with each exhale, the movement settling back to center.

Finally, connect all three directions: your belly radiates out 360 degrees on the horizon with each inhale, simultaneously moving forward, backward, and out to both sides, and then settles inward with each exhale.

Finish with open awareness – scanning your whole inner landscape from feet to head, back to front, and center to extremities, and letting your body breathe itself, as you notice what is alive in you now.

Inhale – Belly Radiates Outwards; Exhale – Belly Settles Inwards

“The belly is an extraordinary diagnostic instrument. It displays the armoring of the heart as a tension in the belly. Trying tightens the belly. Trying stimulates judgment. Hard belly is often judging belly. Observing the relative openness or closedness of the belly gives insight into when and how we are holding (on) to our pain. The deeper our relationship to the belly, the sooner we discover if we are holding in the mind or opening into the heart.” – Steven Levine (1991)

The contact of your hands on your belly helps the mind pay attention to the subtle movement created by the inhale-exhale cycle of the diaphragm. The combination of tactility and interoceptive awareness focusing on the belly shifts attention into our “second brain” (the enteric nervous system) and signals the mind it can rest and soften. More pleasurable sensation is often accompanied by an emergent feeling of safety as you settle into sensing the rhythm of a slower, more even breath, creating a feedback loop between bodily/somatic ease and mental calm. Giving yourself some daily “breathing room” in this way can help you build the calm muscle!

Naturally, there can be hiccups along the way so it is not all unicorns and rainbows! By giving the mind bodily tasks to accomplish, particularly in relationship to deepening and expanding the movement of the breath, we ease the self into a slower, more receptive state of being. Yet, in this receptive state of ease, whatever is in the background of awareness can arise and slip through the “border control”, sometimes taking us by surprise and causing distress. Depending upon the nature of the information, there are layers of action strategies that can be progressively taken to modulate and buffer what arises:

Tether your awareness to the breath rhythm with hands on your belly to stay present as a witness. Next step up: open your eyes softly and look around to orient in your present environment. Further step up: breath flow, hands-on belly, eyes open a wee bit looking around, and adding simple movement, like rocking a bit in all directions or expressing an exhale as a sigh, a yawn or a hum.

Note: If you find your personal resources are insufficient, find a guide to work with one-on-one to discover your own individual path for increasing the “window of capacity”. Above all, be gentle with yourself – take your time – cultivate your garden – and enjoy your breath!

References

Epstein, M. (2013) Thoughts without a Thinker: Psychotherapy from a Buddhist Perspective. New York: Basic Books. https://www.amazon.com/Thoughts-Without-Thinker-Psychotherapy-Perspective/dp/0465050948

Levine, S. (1991). Guided Meditations, Explorations and Healings. New York: Anchor. https://www.amazon.com/Guided-Meditations-Explorations-Healings-Stephen/dp/0385417373

Luthe, W. (1969). Autogenic Therapy Volume 1 Autogenic Methods. New York: Grune and Stratton. https://www.amazon.com/Autogenic-Therapy-1-Methods/dp/B0013457B4/

Luthe, W. (1979). About the Methods of Autogenic Therapy. In: Peper, E., Ancoli, S., Quinn, M. (eds). Mind/Body Integration. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4613-2898-8_12

Luthe, W. & de Rivera, L. (2015). Wolfgang Luthe Introductory workshop: Introduction to the Methods of Autogenic Training, Therapy and Psychotherapy (Autogenic Training & Psychotherapy). CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. https://www.amazon.com/WOLFGANG-LUTHE-INTRODUCTORY-WORKSHOP-Psychotherapy/dp/1506008038/

Is mindfulness training old wine in new bottles?

Posted: January 11, 2024 Filed under: attention, behavior, biofeedback, Breathing/respiration, CBT, cognitive behavior therapy, healing, health, meditation, self-healing, stress management | Tags: anxiety, autogenic training, biofeedback, health, meditation, mental-health, mindfulness, pain, passive attention, progressive muscle relaxation, wellness, yoga 2 CommentsAdapted from: Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Lin, I-M. (2019). Mindfulness training has themes common to other technique. Biofeedback. 47(3), 50-57. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-47.3.02

This extensive blog discusses the benefits of mindfulness-based meditation (MM) techniques and explores how similar beneficial outcomes occur with other mind-centered practices such as transcendental meditation, and body-centered practices such as progressive muscle relaxation (PMR), autogenic training (AT), and yoga. For example, many standardized mind-body techniques such as mindfulness-based stress reduction and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (a) are associated with a reduction in symptoms of symptoms such as anxiety, pain and depression. This article explores the efficacy of mindfulness based techniques to that of other self-regulation techniques and identifies components shared between mindfulness based techniques and several previous self-regulation techniques, including PMR, AT, and transcendental meditation. The authors conclude that most of the commonly used self-regulation strategies have comparable efficacy and share many elements.

Mindfulness-based strategies are based in ancient Buddhist practices and have found acceptance as one of the major contemporary behavioral medicine techniques (Hilton et al, 2016; Khazan, 2013). Throughout this blog the term mindfulness will refer broadly to a mental state of paying total attention to the present moment, with a non-judgmental awareness of the inner and/ or outer experiences (Baer et al., 2004; Kabat-Zinn, 1994).

In 1979, Jon Kabat-Zinn introduced a manual for a standardized Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center (Kabat-Zinn, 1994, 2003). The eight-week program combined mindfulness as a form of insight meditation with specific types of yoga breathing and movements exercises designed to focus on awareness of the mind and body, as well as thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

There is a substantial body of evidence that mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT); Teasdale et al., 1995) and mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) (Kabat-Zinn, 1994, 2003) have combined with skills of cognitive therapy for ameliorating stress symptoms such as negative thinking, anxiety and depression. For example, MBSR and MBCT has been confirmed to be clinical beneficial in alleviating a variety of mental and physical conditions, for people dealing with anxiety, depression, cancer-related pain and anxiety, pain disorder, or high blood pressure (The following are only a few of the hundred studies published: Andersen et al., 2013; Carlson et al., 2003; Fjorback et al., 2011; Greeson, & Eisenlohr-Moul, 2014; Hoffman et al., 2012; Marchand, 2012; Baer, 2015; Demarzo et al., 2015; Khoury et al, 2013; Khoury et al, 2015; Chapin et al., 2014; Witek Janusek et al., 2019). Currently, MBSR and MBCT techniques that are more standardized are widely applied in schools, hospitals, companies, prisons, and other environments.

The Relationship Between Mindfulness and Other Self-Regulation Techniques

This section addresses two questions: First, how do mindfulness-based interventions compare in efficacy to older self-regulation techniques? Second, and perhaps more basically, how new and different are mindfulness-based therapies from other self-regulation-oriented practices and therapies?

Is mindfulness more effective than other mind/body body/mind approaches?

Although mindfulness-based meditation (MM) techniques are effective, it does not mean that is is more effective than other traditional meditation or self-regulation approaches. To be able to conclude that MM is superior, it needs to be compared to equivalent well-coached control groups where the participants were taught other approaches such as progressive relaxation, autogenic training, transcendental meditation, or biofeedback training. In these control groups, the participants would be taught by practitioners who were self-experienced and had mastered the skills and not merely received training from a short audio or video clip (Cherkin et al, 2016). The most recent assessment by the National Centere for Complementary and Integrative Health, National Institutes of Health (NCCIH-NIH, 2024) concluded that generally “the effects of mindfulness meditation approaches were no different than those of evidence-based treatments such as cognitive behavioral therapy and exercise especially when they include how to generalize the skills during the day” (NCCIH, 2024). Generalizing the learned skills into daily life contributes to the successful outcome of Autogenic Training, Progressive Relaxation, integrated biofeedback stress management training, or the Quieting Response (Luthe, 1979; Davis et al., 2019; Wilson et al., 2023; Stroebel, 1982).

Unfortunately, there are few studies that compare the effective of mindfulness meditation to other sitting mental techniques such as Autogenic Training, Transcendental Meditation or similar meditative practices that are used therapeutically. When the few randomized control studies of MBSR versus autogenic training (AT) was done, no conclusions could be drawn as to the superior stress reduction technique among German medical students (Kuhlmann et al., 2016).

Interestingly, Tanner, et al (2009) in a waitlist study of students in Washington, D.C. area universities practicing TM used the concept of mindfulness, as measured by the Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills (KIM) (Baer et al, 2004) as a dependent variable, where TM practice resulted in greater degrees of ‘mindfulness.’ More direct comparisons of MM with body-focused techniques, such as progressive relaxation, or Autogenic training mindfulness-based approaches, have not found superior benefit. For example, Agee et al (2009) compared the stress management effects of a five-week Mindfulness Meditation (MM) to a five-week Progressive Muscle Relaxation (PMR) course and found no meaningful reports of superiority of one over the other program; both MM and PMR were effective in reducing symptoms of stress.

In a persuasive meta-analysis comparing MBSR with other similar stress management techniques used among military service members, Crawford, et al (2013) described various multimodal programs for addressing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other military or combat-related stress reactions. Of note, Crawford, et al (2013) suggest that all of the multi-modal approaches that include Autogenic Training, Progressive Muscle Relaxation, movement practices including Yoga and Tai Chi, as well as Mindfulness Meditation, and various types of imagery, visualization and prayer-based contemplative practices ALL provide some benefit to service members experiencing PTSD.

An important observation by Crawford et al (2013) pointed out that when military service members had more physical symptoms of stress, the meditative techniques appeared to work best, and when the chief complaints were about cognitive ruminations, the body techniques such as Yoga or Tai Chi worked best to reduce symptoms. Whereas it may not be possible to say that mindfulness meditation practices are clearly superior to other mind-body techniques, it may be possible to raise questions about mechanisms that unite the mind-body approaches used in therapeutic settings.

Could there be negative side effects?

Another point to consider is the limited discussion of the possible absence of benefit or even harms that may be associated with mind-body therapies. For example, for some people, meditation does not promote prosocial behavior (Kreplin et al, 2018). For other people, meditation can evoke negative physical and/or psychological outcomes (Lindahl et al, 2017; Britton et al., 2021). There are other struggles with mind-body techniques when people only find benefit in the presence of a skilled clinician, practitioner, or guru, suggesting a type of psychological dependency or transference, rather than the ability to generalize the benefits outside of a set of conditions (e.g. four to eight weeks of one to four hour trainings) or a particular setting (e.g. in a natural and/or quiet space).

Whereas the detailed instructions for many mindfulness meditation trainings, along with many other types of mind-body practices (e.g. Transcendental Meditation, Autogenic Training, Progressive Muscle Relaxation, Yoga, Tai Chi…) create conditions that are laudable because they are standardized, a question is raised as to ‘critical ingredients’, using the metaphor of baking. The difference between a chocolate and a vanilla cake is not ingredients such as flour, or sugar, etc., which are common to all cakes, but rather the essential or critical ingredient of the chocolate or vanilla flavoring. So what are the essential or critical ingredients in mind-body techniques? Extending the metaphor, Crawford, et al (2013, p. 20) might say the critical ingredient common to the mind-body techniques they studied was that people “can change the way their body and mind react to stress by changing their thoughts, emotions, and behaviors…” with techniques that, relatively speaking, “involve minimal cost and training time.”

The skeptical view suggested here is that MM techniques share similar strategies with other mind-body approaches that encouraging learners to ‘pay attention and shift intention.’ This strategy is part of the instructions when learning Progressive Relaxation, Autogenic Training, Transcendental Meditation, movement meditation of Yoga and Tai Chi and, with instrumented self-regulation techniques such as bio/neurofeedback. In this sense, MM training repackages techniques that have been available for millennia and thus becomes ‘old wine sold in new bottles.’

We wonder if a control group for compassionate mindfulness training would report more benefits if they were asked not only to meditate on compassionate acts, but actually performed compassionate tasks such as taking care of person in pain, helping a homeless person, or actually writing and delivering a letter of gratitude to a person who has helped them in the past? The suggestion is to titrate the effects of MM techniques, moving from a more basic level of benefit to a more fully actualized level of benefit, generalizing their skill beyond a training setting, as measured by the Baer et al (2004) Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills.