Biofeedback, posture and breath: Tools for health

Posted: December 1, 2022 Filed under: ADHD, behavior, biofeedback, Breathing/respiration, CBT, cognitive behavior therapy, computer, digital devices, education, emotions, ergonomics, Evolutionary perspective, Exercise/movement, healing, health, laptops, mindfulness, Neck and shoulder discomfort, Pain/discomfort, posture, relaxation, screen fatigue, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized, vision, zoom fatigue 2 CommentsTwo recent presentations that that provide concepts and pragmatic skills to improve health and well being.

How changing your breathing and posture can change your life.

In-depth podcast in which Dr. Abby Metcalf, producer of Relationships made easy, interviews Dr. Erik Peper. He discusses how changing your posture and how you breathe may result in major improvement with issues such as anxiety, depression, ADHD, chronic pain, and even insomnia! In the presentation he explain how this works and shares practical tools to make the changes you want in your life.

How to cope with TechStress

A wide ranging discussing between Dr. Russel Jaffe and Dr Erik that explores the power of biofeedback, self-healing strategies and how to cope with tech-stress.

These concepts are also explored in the book, TechStress-How Technology is Hijacking our Lives, Strategies for Coping and Pragmatic Ergonomics. You may find this book useful as we spend so much time working online. The book describes the impacts personal technology on our physical and emotional well-being. More importantly, “Tech Stress” provides all of the basic tools to be able not only to survive in this new world but also thrive in it.

Additiona resources:

Gonzalez, D. (2022). Ways to improve your posture at home.

A breath of fresh air: Breathing and posture to optimize health

Posted: April 3, 2022 Filed under: behavior, Breathing/respiration, CBT, cognitive behavior therapy, emotions, ergonomics, Exercise/movement, health, mindfulness, Neck and shoulder discomfort, Pain/discomfort, posture, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: respiration 1 CommentMost people breathe 22,000 breaths per day. We tend to breathe more rapidly when stressed, anxious or in pain. While a slower diaphragmatic breathing supports recovery and regeneration. We usually become aware of our dysfunctional breathing when there are problems such as nasal congestion, allergies, asthma, emphysema, or breathlessness during exertion. Optimal breathing is much more than the absence of symptoms and is influenced by posture. Dysfunctional posture and breathing are cofactors in illness. We often do not realize that posture and breathing affect our thoughts and emotions and that our thoughts and emotions affect our posture and breathing. Watch the video, A breath of fresh air: Breathing and posture to optimize health, that was recorded for the 2022 Virtual Ergonomics Summit.

Resolving a chronic headache with posture feedback and breathing

Posted: January 4, 2022 Filed under: behavior, Breathing/respiration, computer, digital devices, ergonomics, health, laptops, Neck and shoulder discomfort, Pain/discomfort, posture, relaxation, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: Desktop feedback app, headache, migraine 11 Comments| Adapted from Peper, E., Covell, A., & Matzembacker, N. (2021). How a chronic headache condition became resolved with one session of breathing and posture coaching. NeuroRegulation, 8(4), 194–197. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.8.4.194 |

This blog describes the process by which a 32 year old woman student’s chronic headaches that she had since age eighteen was resolved in a single coaching session. The student suffered two or three headache per week a week which initially began when she was eighteen after using digital devices and encouraged her to slouch as she looked down. Although she describes herself as healthy, she reported having high level of anxiety and occasional depression. She self-medicated with 2 to 10 Excedrin tablets a week. It is possible that the chronic headaches could partially be triggered by caffeine withdrawal which get resolved by taking more Excedrins (Greben et al., 1980) since Excedrin contains 65 mg of caffeine as well as 250 mg of Acetaminophen which can be harmful to liver function (Bauer et al., 2021).

The behavioral coaching intervention

During the first day in class, the student approached the instructor and she shared that she had a severe headache. During their conversation, the instructor noticed that she was breathing in her chest without abdominal movement, her shoulders were held tight, her posture slightly slouched and her hands were cold. As she was unaware of her body responses, the instructor offered to guide her through some practices that may be useful to reduce her headache. The same strategies could also be useful for the other students in the class; since, headaches, anxiety, zoom fatigue, neck and shoulder tension, abdominal discomfort, and vision problems are common and have increased as people spent more time in front of screens (Charles et al., 2021; Ahmed et al., 2021; Bauer, 2021; Kuehn, 2021; Peper et al., 2021 ).

These symptoms may occur because of bad posture, neck and shoulder tension, shallow chest breathing, stress and social isolation (Elizagaray-Garcia et al., 2020; Schulman, 2002). When people become aware of their dysfunctional somatic patterns and change their posture, breathing pattern, internal language and implement stress management techniques, they often report a reduction in symptoms such as irritable bowel syndrome, acid reflux, neck and shoulder tension, or anxiety (Peper et al, 2017a; Peper et al, 2016a). Sometimes, a single coaching session can be sufficient to improve health.

Working hypothesis: The headaches were most likely tension headaches and not migraines and may be the result of chronic neck and shoulder tension which was maintained during chest breathing and the slouched head forward body posture. If she could change her posture, relax her neck and shoulders, and breathe diaphragmatically so that the lower abdomen widen during inhalation, most likely her shoulder and neck tension would decrease. Therefore, by changing posture from a slouched to upright position combined with slower diaphragmatic breathing, the muscle tension would be reduced and the headaches would decrease.

Breathing and posture changes

She was encouraged to sit upright so that the abdomen had space to expand (Peper et al., 2020). In addition, she needed to loosen the clothing around her waist to provide room for her abdomen to expand during inhalation instead of her chest lifting (MacHose & Peper, 1991). Allowing abdominal expansion can be challenging for many paticipants since they are self-conscious about their body image, as well holding their stomach in as an unconscious learned response to avoid pain after having had abdominal surgery, or as an automatic protective response to threat (Peper et al., 2015). The upright position also allowed her to sit tall and erect in which the back of head reaches upward towards the ceiling while relaxing and feeling gravity pulling her shoulders downward and at the same time relaxing her hips and legs.

With guided verbal and tactile coaching, she learned to master slower diaphragmatic breathing in which she gently and slowly exhaled by making a sound of pssssssst (exhaling through pursed lips) which tends to activate the transverse and oblique abdominal muscles and slightly tighten the pelvic floor muscles so that her lower abdomen would slightly constrict at the end of the exhalation (Peper et al., 2016). Then, by allowing the lower abdomen and pelvic floor relax so that the abdomen could expand in 360 degrees, inhalation occurred.

While practicing the slower breathing in this relaxed upright position, she was instructed to sense/imagine feeling a flow of down and through her arms and out her hands as she exhaled (as if the air could flow through straws down her arms). After a few minutes, she felt her headache decrease and noticed that her hands had warmed. After this short coaching intervention, she went back to her seat in class and continued to practice the relaxed effortless breathing while sitting upright and allowing her shoulders to melt downward.

The use of muscle feedback to demonstrate residual covert muscle tension

During class session, she volunteered to have her trapezius muscle monitored with electromyography (EMG). The EMG indicated that her muscles were slightly tense even though she reported feeling relaxed. With a few minutes of EMG biofeedback exploration, she discovered that she could relax her shoulder muscles by feeling them being heavy and melting.

Implementing home practice with a posture app

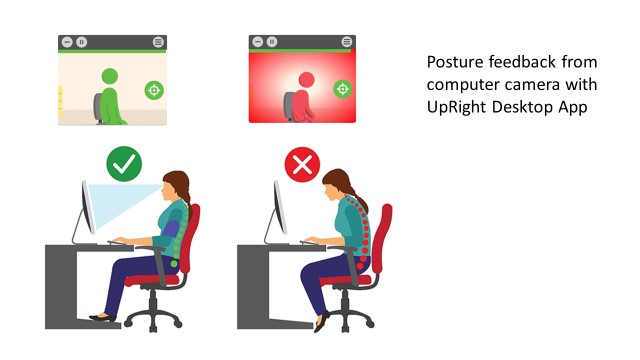

As part of the class homework, she was assigned a self-study for two weeks with the posture feedback app, Dario Desktop. The app uses the computer/laptop camera to monitor posture and provides visual feedback in a small window on the computer screen and/or an auditory signal each time she slouches as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Posture feedback to signal to participant that the person is slouching.

To observe the effect of the posture breathing training, she monitored her symptoms for three days without feedback and then installed the posture feedback application on her laptop to provide feedback whenever she slouched. The posture feedback reminded her to practice better posture during the day while working on her computer and also do a few stretches or shift to standing when using the computer for an extended period of time. Each time the feedback signal indicated she slouched, she would sit up and change her posture, breathe lower and slower and relax her shoulders.

She also monitored what factors triggered the slouching. In additionally, she added daily reminders to her phone to remind her of her posture and to stretch and stand after each hour of studying. After two weeks she recorded her symptoms for three days for the post assessment without posture feedback.

Results

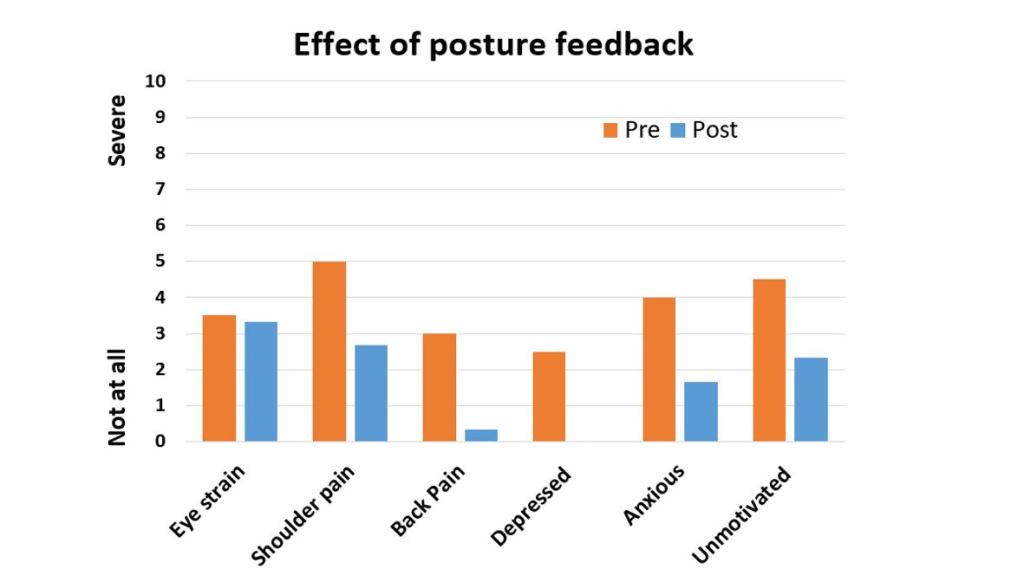

The chronic headache condition which had been present for fourteen years disappeared and she has not used any medication since the first day of class. She reported after two weeks that her shoulder and back discomfort/pain, depression, anxiety and lack of motivation decreased as shown in Figure 2. At the fourteen week follow up, she continues to have no headaches and has not used any medication.

Figure 2. Changes in symptoms after implementing posture feedback for two weeks.

She used the desktop posture app every time she opened her laptop at home as often as 3-5 times per day (roughly 2-6 hours).In addition, when she felt beginning of discomfort or thought she should take medication, she would adjust her posture and breathe. While using the app, she identified numerous factors that were associated with slouching as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Behaviors associated with slouching.

Discussion

The decrease in depression, anxiety and increase in motivation may be the direct result of posture change; since, a slouched position tends to increase hopeless, helpless and powerless thoughts while the upright position tends to increase subjective felt energy and easier access to empowering and positive thoughts (Peper et al., 2017b; Veenstra et al., 2017; Wilson & Peper, 2004; Tsai et al., 2016). Most likely, a major factor that contributed to the elimination of her headaches was that she implemented changes in her behavior. One major factor was using posture feedback tool at home to remind her to sit tall and relax her shoulders while practicing slower diaphragmatic breathing. As she noted, “Although it was distracting to be reminded all the time about my posture, it did decrease my neck pain. With the pain reduction, I was able to sit at the computer longer and felt more motivated.”

The combination of slower lower abdominal breathing with the upright posture reversed her protective/defensive body position (tightening the muscle in the lower abdomen and pelvic floor and pressing the knees together while curling the shoulder forward for protection). The upright posture creates a position of empowerment and trust by which the lower abdomen could expand which supported health and regeneration. In addition, the upright posture allowed easier access to positive thoughts and reduced recall of hopeless, powerless, defeated memories. It is also possible that caffeine withdrawal was a co-factor in evoking headaches (Küçer, 2010). By eliminating the medication containing caffeine, she also eliminated the triggering of the caffeine withdrawal headaches.

This case example suggests that health care providers first rule out any pathology and then teach behavioral self-healing strategies that the clients can implement instead of immediately prescribing medications. These interventions could include slower and lower diaphragmatic breathing, upright posture feedback, muscle biofeedback training, hear rate variability training, stress management, cognitive behavior therapy and facilitating health promoting lifestyles modifications such as regular sleep, exercise and healthier diet. When students implement these behavioral changes as part of a five week self-healing program, many report significant decreases in symptoms such as headaches, anxiety, neck and shoulder pain, and gastrointestinal distress (Peper et al., 2016a).

Watch April Covell describe her experience with the self-healing approach to eliminate her chronic headaches.

See the following blogs for additional instructions how to breathe diaphragmatically.

References

Ahmed, S., Akter, R., Pokhrel, N. et al. (2021). Prevalence of text neck syndrome and SMS thumb among smartphone users in college-going students: a cross-sectional survey study. J Public Health (Berl.) 29, 411–416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-019-01139-4

Bauer, A.Z., Swan, S.H., Kriebel, D. et al. (2021). Paracetamol use during pregnancy — a call for precautionary action. Nat Rev Endocrinol . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-021-00553-7

Charles, N. E., Strong, S. J., Burns, L. C., Bullerjahn, M. R., & Serafine, K. M. (2021). Increased mood disorder symptoms, perceived stress, and alcohol use among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry research, 296, 113706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113706

Elizagaray-Garcia, I., Beltran-Alacreu, H., Angulo-Díaz, S., Garrigós-Pedrón, M., Gil-Martínez, A. (2020). Chronic Primary Headache Subjects Have Greater Forward Head Posture than Asymptomatic and Episodic Primary Headache Sufferers: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Pain Med, 21(10):2465-2480. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnaa235

Greden, J.F., Victor, B.S., Fontaine, P., & Lubetsky, M. (1980). Caffeine-Withdrawal Headache: A Clinical Profile. Psychosomatics, 21(5), 411-413, 417-418. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0033-3182(80)73670-8

Küçer, N. (2010). The relationship between daily caffeine consumption and withdrawal symptoms: a questionnaire-based study. Turk J Med Sci, 40(1), 105-108. https://doi.org/10.3906/sag-0809-26

Kuehn, B.M. (2021). Increase in Myopia Reported Among Children During COVID-19 Lockdown. JAMA, 326(11),999. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.14475

MacHose, M. & Peper, E. (1991). The effect of clothing on inhalation volume. Biofeedback and Self-Regulation 16, 261–265 (1991). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01000020

Peper, E., Booiman, A., Lin, I-M, Harvey, R., & Mitose, J. (2016). Abdominal SEMG Feedback for Diaphragmatic Breathing: A Methodological Note. Biofeedback. 44(1), 42-49. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-44.1.03

Peper, E., Gilbert, C.D., Harvey, R. & Lin, I-M. (2015). Did you ask about abdominal surgery or injury? A learned disuse risk factor for breathing dysfunction. Biofeedback. 34(4), 173-179. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-43.4.06

Peper, E., Lin, I-M., Harvey, R., & Perez, J. (2017b). How posture affects memory recall and mood. Biofeedback. 45 (2), 36-41. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-45.2.01

Peper, E., Mason, L., Harvey, R., Wolski, L, & Torres, J. (2020). Can acid reflux be reduced by breathing? Townsend Letters-The Examiner of Alternative Medicine, 445/446, 44-47. https://www.townsendletter.com/article/445-6-acid-reflux-reduced-by-breathing/

Peper, E., Mason, L., Huey, C. (2017a). Healing irritable bowel syndrome with diaphragmatic breathing. Biofeedback. (45-4). https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-45.4.04

Peper, E., Miceli, B., & Harvey, R. (2016a). Educational Model for Self-healing: Eliminating a Chronic Migraine with Electromyography, Autogenic Training, Posture, and Mindfulness. Biofeedback, 44(3), 130–137. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-44.3.03

Peper, E., Wilson, V., Martin, M., Rosegard, E., & Harvey, R. (2021). Avoid Zoom fatigue, be present and learn. NeuroRegulation, 8(1), 47–56. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.8.1.47

Schulman, E.A. (2002). Breath-holding, head pressure, and hot water: an effective treatment for migraine headache. Headache, 42(10), 1048-50. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1526-4610.2002.02237.x

Tsai, H. Y., Peper, E., & Lin, I. M.* (2016). EEG patterns under positive/negative body postures and emotion recall tasks. NeuroRegulation, 3(1), 23-27. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.3.1.23

Veenstra, L., Schneider, I.K., & Koole, S.L. (2017). Embodied mood regulation: the impact of body posture on mood recovery, negative thoughts, and mood-congruent recall. Cogntion and Emotion, 31(7), 1361-1376. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2016.1225003

Wilson, V.E. and Peper, E. (2004). The effects of upright and slumped postures on the generation of positive and negative thoughts. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 29(3), 189–195. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:apbi.0000039057.32963.34

Reduce stress, anxiety and negative thoughts with posture, breathing and reframing

Posted: October 19, 2019 Filed under: behavior, Breathing/respiration, emotions, Exercise/movement, posture, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: Acceptance and comitment therapy, ACT, CBT, cognitive behavior therapy, empowerment, Reframing 4 CommentsWhen locked into a position, options appear less available. By unlocking our body, we allow our brain to unlock and become open to new options.

Changing positions may dissolve the rigidity associated with a fixed position. When we step away from the conflict, take a walk, look up at the treetops, roof lines and clouds, or do something different, we loosen up and new ideas may occur. We may then be able see the conflict from a different point of view that allows resolution.

When stressed, anxious or depressed, it is challenging to change. The negative feelings, thoughts and worries continue to undermine the practice of reframing the experience more positively. Our recent study found that a simple technique, that integrates posture with breathing and reframing, rapidly reduces anxiety, stress, and negative self-talk (Peper, Harvey, Hamiel, 2019).

Thoughts and emotions affect posture and posture affects thoughts and emotions. When stressed or worried (e.g., school performance, job security, family conflict, undefined symptoms, or financial insecurity), our bodies respond to the negative thoughts and emotions by slightly collapsing and shifting into a protective position. When we collapse/slouch, we are much more at risk to:

- Feel helpless (Riskind & Gotay, 1982).

- Feel powerless (Westfeld & Beresford, 1982; Cuddy, 2012).

- Recall and being more captured by negative memories (Peper, Lin, Harvey, & Perez, 2017; Tsai, Peper, & Lin, 2016),

- Experience cognitive difficulty (Peper, Harvey, Mason, & Lin, 2018).

When we are upright and look up, we are more likely to:

- Have more energy (Peper & Lin, 2012).

- Feel stronger (Peper, Booiman, Lin, & Harvey, 2016).

- Find it easier to do cognitive activity (Peper, Harvey, Mason, & Lin, 2018).

- Feel more confident and empowered (Cuddy, 2012).

- Recall more positive autobiographical memories (Michalak, Mischnat,& Teismann, 2014).

Experience how posture affects memory and the feelings (adapted from Alan Alda, 2018)

Stand up and do the following:

- Think of a memory/event when you felt defeated, hurt or powerless and put your body in the posture that you associate with this feeling. Make it as real as possible . Stay with the feeling and associated body posture for 30 seconds. Let go of the memory and posture. Observe what you experienced.

- Think of a memory/event when you felt empowered, positive and happy put your body in the posture that you associate with those feelings. Make it as real as possible. Stay with the feeling and associated body posture for 30 seconds. Let go of the memory and posture. Observe what you experienced.

- Adapt the defeated posture and now recall the positive empowering memory while staying in the defeated posture. Observe what you experience.

- Adapt the empowering posture and now recall the defeated hopeless memory while staying in the empowered posture. Observe what you experience.

Almost all people report that when they adapt the body posture congruent with the emotion that it was much easier to access the memory and feel the emotion. On the other hand when they adapt the body posture that was the opposite to the emotions, then it was almost impossible to experience the emotions. For many people, when they adapted the empowering posture, they could not access the defeated hopeless memory. If they did access that memory, they were more likely be an observer and not be involved or emotionally captured by the negative memory.

Comparison of Posture with breathing and reframing to Reframing

The study investigated whether changing internal dialogue (reframing) or combining posture change and breathing with changing internal dialogue would reduce stress and negative self-talk more effectively.

The participants were 145 college students (90 women and 55 men) average age 25.0 who participated as part of a curricular practice in four different classes.

After the students completed an anonymous informational questionnaire (history of depression, anxiety, blanking out on exams, worrying, slouching), the classes were divided into two groups. They were then asked to do the following:

- Think of a stressful conflict or problem and make it as real as possible for one minute. Then let go of the stressful memory and do one of the two following practices.

- Practice A: Reframe the experience positively for 20 seconds.

- Practice B: Sit upright, look up, take a breath and reframe the experience positively for 20 seconds.

- After doing practice A or practice B, rate the extent to which your negative thoughts and anxiety/tension were reduced, from 0 (not at all) to 10 (totally).

- Now repeat this exercise except switch and do the other practice. (Namely, if you did A now you do B; if you did B now you do A).

RESULTS

Overwhelmingly students reported that sitting erect, breathing and reframing positively was much more effective than only reframing as shown in Figure 1 and 2.

Figure 1. Percentage of students rating posture, breath and reframing practice (PBRP) as more effective than reframing practice (RP) in reducing negative thoughts, anxiety and stress. Figure 2. Self-rating of reduction of negative thoughts and anxiety/tension

Figure 2. Self-rating of reduction of negative thoughts and anxiety/tension

Stop reading. Do the practice yourself. It is only through experience that you know whether posture with breathing and reframing is a more beneficial than simply reframing the language.

Implications for education, counseling, psychotherapy.

Our findings have implications for education, counseling and psychotherapy because students and clients usually sit in a slouched position in classrooms and therapeutic settings. By shifting the body position to an erect upright position, taking a breath and then reframing, people are much more successful in reducing their negative thoughts and anxiety/stress. They report feeling much more optimistic and better able to cope with felt stress as shown by representative comments in table 1.

| Reframing | Posture, breath and reframing |

| After changing my internal language, I still strongly felt the same thoughts. | I instantly felt better about my situation after adjusting my posture. |

| I felt a slight boost in positivity and optimism. The negative feelings (anxiety) from the negative thoughts also diminished slightly. | The effects were much stronger and it was not isolated mentally. I felt more relief in my body as well. |

| Even after changing my language, I still felt more anxious. | Before changing my posture and breathing, I felt tense and worried. After I felt more relaxed. |

| I began to lift my mood up; however, it didn’t really improve my mood. I still felt a bit bad afterwards and the thoughts still stayed. | I began to look from the floor and up towards the board. I felt more open, understanding and loving. I did not allow myself to get let down. |

| During the practice, it helped calm me down a bit, but it wasn’t enough to make me feel satisfied or content, it felt temporary. | My body felt relaxed overall, which then made me feel a lot better about the situation. |

| Difficult time changing language. | My posture and breathing helped, making it easier to change my language. |

| I felt anger and stayed in my position. My body stayed tensed and I kept thinking about the situation. | I felt anger but once I sat up straight and thought about breathing, my body felt relaxed. |

| Felt like a tug of war with my thoughts. I was able to think more positively but it took a lot more brain power to do so. | Relaxed, extended spine, clarity, blank state of mind. |

Table 1. Some representative comments of practicing reframing or posture, breath and reframing.

The results of our study in the classroom setting are not surprising. Many us know to take three breaths before answering questions, pause and reflect before responding, take time to cool down before replying in anger, or wait till the next day before you hit return on your impulsive email response.

Currently, counseling, psychotherapy, psychiatry and education tend not to incorporate body posture as a potential therapeutic or educational intervention for teaching participants to control their mood or reduce feelings of powerlessness. Instead, clients and students often sit slightly collapsed in a chair during therapy or in class. On the other hand, if individuals were encouraged to adopt an upright posture especially in the face of stressful circumstances it would help them maintain their self-esteem, reduce negative mood, and use fewer sadness words as compared to the individual in a slumped and seated posture (Nair, Sagar, Sollers, Consedine, & Broadbent, 2015).

THE VALUE OF SELF-EXPERIENCE

What makes this study valuable is that participants compare for themselves the effects of the two different interventions techniques to reduce anxiety, stress and negative thoughts. Thus, the participants have an opportunity to discover which strategy is more effective instead of being told what to do. The demonstration is even more impressive when done in groups because nearly all participants will report that changing posture with breathing and reframing is more beneficial.

This simple and quick technique can be integrated in counseling and psychotherapy by teaching clients this behavioral technique to reduce stress. In Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), sitting upright can help the individual replace a thought with a more reasonable one. In third wave CBT, it can help bypass the negative content of the original language and create a metacognitive change, such as, “I will not let this thought control me.”

It can also help in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) since changing one’s body posture may facilitate the process of “acceptance” (Hayes, Pistorello, & Levin, 2012). Adopting an upright sitting position and taking a breath is like saying “I am here, I am present, I am not escaping or avoiding.” This change in body position represents movement from inside to outside, movement from accepting the unpleasant emotion related to the negative thoughts toward a “commitment” to moving ahead, contrary to the automatic tendency to follow the negative thought. The positive reframing during body position or posture change is not an attempt to color reality in pretty colors, but rather a change of awareness, perspective, and focus that helps the individual identify and see some new options for moving ahead toward commitment according to one’s values. This intentional change in direction is central in ACT and also in positive psychology (Stichter, 2018).

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

We suggest that therapists, educators, clients and students get up out of their chairs and incorporate body movements when they feels overwhelmed and stuck. Finally, this study points out that mind and body are affected by each other. It provides another example of the psychophysiological principle enunciated by Elmer Green (1999, p 368):

“Every change in the physiological state is accompanied by an appropriate change in the mental-emotional state, conscious or unconscious; and conversely, every change in the mental-emotional state, conscious or unconscious is accompanied by an appropriate change in the physiological state.”

The findings of this study echo the ancient spiritual wisdom that is is central to the teaching of the Zen Master, Thich Nhat Hanh. He recommends that his students recite the following at any time:

Breathing in I calm my body,

Breathing out I smile,

Dwelling in the present moment,

I know it is a wonderful moment.

References

Cuddy, A. (2012). Your body language shapes who you are. Technology, Entertainment, and Design (TED) Talk, available at: www.ted.com/talks/amy_cuddy_your_body_language_shapes_who_you_are

Green, E. (1999). Beyond psychophysics, Subtle Energies & Energy Medicine, 10(4), page 368.

Peper, E., Booiman, A., Lin, I.M., & Harvey, R. (2016). Increase strength and mood with posture. Biofeedback. 44(2), 66–72.

“Don’t slouch!” Improve health with posture feedback

Posted: July 1, 2019 Filed under: behavior, digital devices, ergonomics, health, Neck and shoulder discomfort, posture, self-healing, Uncategorized | Tags: cellphone, eye strain, Laptop 3 Comments“Although I knew I slouched and often corrected myself, I never realized how often and how long I slouched until the vibratory posture feedback from the UpRight Go 2™ cued me to sit up (see Figure 1).” -Erik Peper

Figure 1. Wearing an UpRight Go 2™ to increase awareness of slouching and as a reminder to change position.

Figure 1. Wearing an UpRight Go 2™ to increase awareness of slouching and as a reminder to change position.

For thousands of years we sat and stood erect. In those earlier times, we looked down to identify specific plants or animal track and then looked up and around to search for possible food sources, identify friends, and avoid predators. The upright, not slouched posture body posture, is innate and optimizes body movement as illustrated in Figure 2 (for more information, see Gokhale, 2013).

Figure 2. The normal aligned spine of a toddler and the aligned posture of a man carrying a heavy load.

Figure 2. The normal aligned spine of a toddler and the aligned posture of a man carrying a heavy load.

Being tall and erect allows the head to freely rotate. Head rotation is reduced when we look down at our cell phones, tablets or laptops (Harvey, Peper, Booiman, Heredia Cedillo, & Villagomez, 2018). Our digital world captures us as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Captured by the screen with a head forward positions.

Figure 3. Captured by the screen with a head forward positions.

Looking down and focusing on the screen for long time periods is the opposite of what supported us to survive and thrive when we lived as hunters and gatherers. When we look down, we become more oblivious to our surroundings and unaware of the possible predators that would have been hunting us for food.

This slouched position increases back, neck, head and eye tension as well as affecting respiration and digestion (Devi, Lakshmi, & Devi, 2018; Peper, Lin, & Harvey, 2017). After looking at the screens for a long time, we may feel tired or exhausted and lack initiative to do something else. Our mood may turn more negative since it is easier to evoke hopeless, helpless and powerless thoughts and memories when looking down than when looking up (Wilson, & Peper, 2004; Peper, Lin, Harvey, & Perez, 2017). In the down position, our brain has to work harder to evoke positive thoughts and memories or perform cognitive tasks as compared to when the head is erect (Tsai, Peper, & Lin, 2016; Peper, Harvey, Mason, & Lin, 2018). By looking down and focusing at the screen, our eyes may begin to strain. To be able to see objects near us, the extraocular muscles of the eyes contract to converge the eyes and the cilia muscles around the lens contract to increase the curvature of the lens so that the reading material is in focus.

Become aware how nearby vision increases eye strain.

Hold your arm straight ahead of you at eye level with your thumb up. While focusing on your thumb, slowly bring your thumb closer and closer to your nose. Observe the increase in eyestrain as you bring your thumb closer to your nose.

Eyestrain tends to develop when we do not relax the eyes by periodically looking away from the screen. When we look at the horizon or trees in the far distance the ciliary muscles and the extraocular muscles relax (Schneider, 2016).

Head forward posture increases neck and back tension

When we look down and concentrate, our head moves significantly forward. The neck and back muscles have to work much harder to hold the head up when the neck is in this flexed position. As Dr. Kenneth Hansraj, Chief of Spine Surgery New York Spine Surgery & Rehabilitation Medicine reported, “The weight seen by the spine dramatically increases when flexing the head forward at varying degrees. An adult head weighs 10-12 pounds in the neutral position. As the head tilts forward the forces seen by the neck surges to 27 pounds at 15 degrees, 40 pounds at 30 degrees, 49 pounds at 45 degrees and 60 pounds at 60 degrees.” (Hansraj, 2014). Our head tends to tilt down when we look at the text, videos, emails, photos, or games and stay in this position for long time periods. We are captured by the digital display and are unaware of our tight overused neck and back muscles. Straightening up so that the back of the head is re-positioned over the spine and looking into the distance may help relax those muscles.

To reduce discomfort caused by slouching, we need to reintegrate our prehistoric life style pattern of alternating between looking down to being tall and looking at the distant scenery or across the room. The first step is awareness of knowing when slouching begins. Yet, we tend to be unaware until we experience discomfort or are reminded by others (e.g, “Don’t slouch! Sit up straight!”). If we could have immediate posture feedback when we begin to slouch, our awareness would increase and remind us to change our posture.

Posture feedback with UpRight Go

Simple posture feedback device such as an UpRight Go 2™ can provide vibratory feedback each time slouching starts as the neck as the head goes forward. The wearable feedback device consists of a small sensor that is attached to the back of the neck or back (see Figure 1). After being paired with a cellphone and calibrated for the upright position, the software algorithm detects changes in tilt and provides vibratory feedback each time the neck/back tilts forward.

In our initial exploration, employees, students and clients used the UpRight feedback devices at work, at school, at home, while driving, walking and other activities to identify situations that caused them to slouch. The most common triggers were:

- Ergonomic caused movement such as bring the head closer to the screen or looking down at their cell phone (for suggestions to improve ergonomics see recommendations at the end of the article)

- Tiredness

- Negative self-critical/depressive thoughts

- Crossing the legs protectively, shallow breathing, and other factors

After having identified some of the factors that were associated with slouching, we compared the health outcome of students who used the device for a minimum for 15 minutes a day for four weeks as compared to a control group who did not use the device. The students who received the UpRight feedback were also encouraged to use the feedback to change their posture and behavior and implemented some of the following strategies.

- Head down when looking at their laptop, tablet or cellphone.

- Change the ergonomics such as using a laptop stand and an external keyboard so that they could be upright while looking at the screen.

- Take many movement breaks to interrupt the static tension.

- Feeling tired.

- Take a break or nap to regenerate.

- Do fun physical activity especially activities where you look upward to re-energize.

- Negative self-critical, powerless, self-critical and depressive thoughts and feelings.

- Reframe internal language to empowering thoughts.

- Change posture by wiggling and looking up to have a different point of view.

- Crossing the legs.

- Sit in power position and breathe diaphragmatically.

- Get up and do a few movements such as shoulder rolls, skipping, or arm swings.

- Other causes.

- Identify the trigger and explore strategies so that you can sit erect without effort.

- Wiggle, move and get up to interrupt static muscle tension.

- Stand up and look out of the window and the far distance while breathing slowly

Posture feedback improves health

After four weeks of using the feedback device and changing behavior, the treatment group reported significant improvements in physical and mental health as shown in Figure 4 & 5.

Figure 4. Using the posture feedback significantly improved the Physical Health and Mental Health Composite Scores for the treatment group as compared to the control group (reproduced from Mason, L., Joy, Peper, & Harvey, 2018).

Figure 5. Pre to post changes after using posture feedback (reproduced from Colombo, Joy, Mason, L., Peper, Harvey, & Booiman, 2017).

Summary

Slouched posture and head forward and down position usually occurs without awareness and often results in long-term discomfort. We recommend that practitioners integrate wearable biofeedback devices to facilitate home practice especially for people with neck, shoulder, back and eye discomfort as well as for those with low energy and depression (Mason et al., 2018). We observed that a small wearable posture feedback device helped participants improve posture and decreased symptoms. The vibratory posture feedback provided the person with the opportunity to identify the triggers associated with slouching and the option to change their posture, behavior and environment.

As one participant reported, “I have been using the Upright device for a few weeks now. I mostly use the device while studying at my desk and during class. I have found that it helps me stay focused at my desk for longer time. Knowing there is something monitoring my posture helps to keep me sitting longer because I want to see how long I can keep an upright posture. While studying, I have found whenever I become frustrated, tired, or when my mind begins to wander I slouch. The Upright then vibrates and I become aware of these feelings and thoughts, and can quickly correct them. This device has improved my posture, created awareness, and increased my overall study time.”

Suggestions to reduce slouching and improve ergonomics

How to arrange your computer and laptop: https://peperperspective.com/2014/09/30/cartoon-ergonomics-for-working-at-the-computer-and-laptop/

Relieve neck and shoulder stiffness: https://peperperspective.com/2019/05/21/relieve-and-prevent-neck-stiffness-and-pain/

Cellphone health: https://peperperspective.com/2014/11/20/cellphone-harm-cervical-spine-stress-and-increase-risk-of-brain-cancer/

References

Colombo, S., Joy, M., Mason, L., Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Booiman, A. (2017). Posture Change Feedback Training and its Effect on Health. Poster presented at the 48th Annual Meeting of the Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, Chicago, IL March, 2017. Abstract published in Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.42(2), 147.

Gokhale, E. (2013). 8 Steps to a Pain-Free Back. Pendo Press.

Schneider, M. (2016). Vision for Life. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic.

Posture and mood: implications and applications to health and therapy

Posted: November 28, 2017 Filed under: Neck and shoulder discomfort, posture, self-healing, Uncategorized | Tags: back pain, electromyography, ergonomics, neck and shoulder tension, posture, spinal alignment, stress management 5 CommentsThis blog has been reprinted from: Peper, E., Lin, I-M, & Harvey, R. (2017). Posture and mood: Implications and applications to therapy. Biofeedback.35(2), 42-48.

Slouched posture is very common and tends to increase access to helpless, hopeless, powerless and depressive thoughts as well as increased head, neck and shoulder pain. Described are five educational and clinical strategies that therapists can incorporate in their practice to encourage an upright/erect posture. These include practices to experience the negative effects of a collapsed posture as compared to an erect posture, watching YouTube video to enhance motivation, electromyography to demonstrate the effect of posture on muscle activity, ergonomic suggestions to optimize posture, the use of a wearable posture biofeedback device, and strategies to keep looking upward. When clients implement these changes, they report a more positive outlook and reduced neck and shoulder discomfort.

Background

Most people slouch without awareness when looking at their cellphone, tablet, or the computer screen (Guan et al., 2016) as shown in Figure 1. Many clients in psychotherapy and in biofeedback or neurofeedback training experience concurrent rumination and depressive thoughts with their physical symptoms. In most therapeutic sessions, clients sit in a comfortable chair, which automatically creates a posterior pelvic tilt and encourages the spine to curve so that the client sits in a slouched position. While at home, they sit on an easy chair or couch, which lets them slouch as they watch TV or surf the web.

Figure 1. (A). Employee working on his laptop. (B). Boy with ADHD being trained with neurofeedback in a clinic. (C). Student looking at cell phone. When people slouch and look at the screen, they tend to slouch and scrunch their neck.

In many cases, the collapsed position also causes people to scrunch their necks, which puts pressure on their necks that may contribute to developing headache or becoming exhausted. Repetitive strain on the neck and cervical spine may trigger a cervical neuromuscular syndrome that involves chronic neck pain, autonomic imbalance and concomitant depression and anxiety (Matsui & Fujimoto, 2011), and may contribute to vertebrobasilar insufficiency –a reduction in the blood supply to the hindbrain through the left and right vertebral arteries and basilar arteries (Kerry, Taylor, Mitchell, McCarthy, & Brew, 2008). From a biomechanical perspective, slouching also places more stress is on the cervical spine, as shown in Figure 2. When the neck compression is relieved, the symptoms decrease (Matsui & Fujimoto, 2011).

Figure 2. The more the head tilts forward, the more stress is placed on the cervical spine. Reproduced by permission from: Hansraj, K. K. (2014). Assessment of stresses in the cervical spine caused by posture and position of the head. Surgical Technology International, 25, 277–279.

Figure 2. The more the head tilts forward, the more stress is placed on the cervical spine. Reproduced by permission from: Hansraj, K. K. (2014). Assessment of stresses in the cervical spine caused by posture and position of the head. Surgical Technology International, 25, 277–279.

Most people are totally unaware of slouching positions and postures until they experience neck, shoulder, and/or back discomfort. Neither clients nor therapists are typically aware that slouching may decrease energy levels and increase the prevalence of negative (hopeless, helpless, powerless, or defeated) memories and thoughts (Peper & Lin, 2012; Peper et al, 2017)

Recommendations for posture awareness and training in treatment/education

The first step in biofeedback training and therapy is to systematically increase awareness and training of posture before attempting further bio/neurofeedback training and/or cognitive behavior therapy. If the client is sitting in a collapsed position in therapy, then it will be much more difficult for them to access positive thoughts, which interferes with further training and effective therapy. For example, research by Tsai, Peper, & Lin (2016) showed that engaging in positive thinking while slouched requires greater mental effort then when sitting erect. Sitting erect and tall contributes to elevated mood and positive thinking. An upright posture supports positive outcomes that may be akin to the beneficial effects of exercise for the treatment of depression (Schuch, Vancampfort, Richards, Rosenbaum, Ward, & Stubbs., 2016).

Most people know that posture affects health; however, they are unaware of how rapidly a slouching posture can impact their physical and mental health. We recommend the following educational and clinical strategies to teach this awareness.

- Practicing activities that raise awareness about a collapsed posture as compared to an erect posture

Guide clients through the practices so that they experience how posture can affect memory recall, physical strength, energy level, and possible triggering of headaches.

A. The effect of collapsed and erect posture on memory recall. Participants reported that it is much easier evoke powerless, hopeless, helpless, and defeated memories when sitting in a collapsed position than when sitting upright. Guide the client through the procedure described in the article, How posture affects memory recall and mood (Peper, Lin, Harvey, and Perez, 2017) and in the blog Posture affects memory recall and mood.

B. The effects of collapsed and erect posture on perceived physical strength. Participants experience much more difficulty in resisting downward pressure at the wrist of an outstretched arm when slouched rather than upright. Guide the client through the exercise described in the article, Increase strength and mood with posture (Peper, Booiman, Lin, & Harvey, 2016) and the blog, Increase strength and mood with posture.

C. The effect of slouching versus skipping on perceived energy levels. Participants experience a significant increase in subjective energy after skipping than walking slouched. Guide the client through the exercises as described in the article, Increase or decrease depression—How body postures influence your energy level (Peper & Lin, 2012).

D. The effect of neck compression to evoke head pressure and headache sensations. In our unpublished study with students and workshop participants, almost all participants who are asked to bring their head forward, then tilt the chin up and at the same time compress the neck (scrunching the neck), report that within thirty seconds they feel a pressure building up in the back of the head or the beginning of a headache. To their surprise, it may take up to 5 to 20 minutes for the discomfort to disappear. Practicing similar awareness activities can be a useful demonstration for clients with dizziness or headaches to experience how posture can increase their symptoms.

- Watching a Youtube video to enhance motivation.

Have clients watch Professor Amy Cuddy’s 2012 TED (Technology, Entertainment, and Design) Talk, Your body language shape who you are, which describes the hormonal changes that occur when adapting a upright power versus collapsed defeated posture.

- Electromyographic (EMG) feedback to demonstrate how posture affects muscle activity.

Record EMG from muscles such as around the cervical spine, trapezius, frontalis, and masseters or beneath the chin (submental lead) to demonstrate that having the head is forward and/or the neck compressed will increase EMG activity, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Electromyographic recording of the muscle under the chin while alternating between bringing the head forward or holding it back, feeling erect and tall.

The client can then learn awareness of the head and neck position. For example, one client with severe concussion experienced significant increase in head pressure and dizziness when she slouched or looked at a computer screen as well as feeling she would never get better. She then practiced the exercise of alternating her awareness by bringing her head forward and then back, and then bringing her neck back while her chin was down, thereby elongating the neck while she continued to breathe. With her head forward, she would feel her molars touching and with her neck back she felt an increase in space between the molars. When she elongated her neck in an erect position, she felt the pressure draining out of her head and her dizziness and tinnitus significantly decrease.

- Assessing ergonomics to optimize posture.

Change the seated posture of both the therapist and the client during treatment and training. Although people may be aware of their posture, it is much easier to change the external environment so that they automatically sit in a more erect power posture. Possible options include:

A. Seat insert or cushions. Sit in upright chairs that encourage an anterior pelvic tilt by having the seat pan slightly lower in the front than in the back or using a seat insert to facilitate a more erect posture (Schwanbeck, Peper, Booiman, Harvey, & Lin, 2015) as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. An example of how posture can be impacted covertly when one sits on a seat insert that rotates the pelvis anteriorly (The seat insert shown in the diagram and used in research is produced by BackJoy™).

B. Back cushion. Place a small pillow or rolled up towel at the kidney level so that the spine is slight arched, instead of sitting collapsed, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. An example of how a small pillow, placed between the back of the chair and the lower back, changes posture from collapsed to erect.

Figure 5. An example of how a small pillow, placed between the back of the chair and the lower back, changes posture from collapsed to erect.

C. Check ergonomic and work site computer use to ensure that the client can sit upright while working at the computer. For some, that means checking their vision if they tend to crane forward and crunch their neck to read the text. For those who work on laptops, it means using either an external keyboard, a monitor, or a laptop stand so the screen is at eye level, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Posture is collapsed when working on a laptop and can be improved by using an external keyboard and monitor. Reproduced by permission from: Bakker Elkhuizen. (n.d.). Office employees are like professional athletes! (2017).

Figure 6. Posture is collapsed when working on a laptop and can be improved by using an external keyboard and monitor. Reproduced by permission from: Bakker Elkhuizen. (n.d.). Office employees are like professional athletes! (2017).

- Wearable posture biofeedback training device

The wearable biofeedback device, UpRight™, consists of a small sensor placed on the spine and works as an app on the cell phone. After calibration the erect and slouched positions, the posture device gives vibratory feedback each time the participant slouches, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Illustration of a posture feedback device, UpRight™. It provides vibratory feedback to the wearer to indicate that they are beginning to slouch.

Clinically, we have observed that clients can learn to identify conditions that are associated with slouching, such as feeling tired, thinking depressive/hopeless thoughts or other situations that evoke slouching. When people wear a posture feedback device during the day, they rapidly become aware of these subjective experiences whenever they slouch. The feedback reminds them to sit in an erect position, and they subsequently report an improvement in health (Colombo et al., 2017). For example, a 26-year-old man who works more than 8 hours a day on computer reported, “I have an improved awareness of my posture throughout my day. I also notice that I had less back pain at the end of the day.”

- Integrating posture awareness and position changes throughout the day

After clients have become aware of their posture, additional training included having them observe their posture as well and negative changes in mood, energy level or tension in their neck and head. When they become aware of these changes, they use it as a cue to slightly arch their back and look upward. If possible have the clients look outside at the tops of trees and notice details such as how the leaves and branches move. Looking at the details interrupts any ongoing rumination. At the same time, have them think of an uplifting positive memory. Then have them take another breath, wiggling, and return to the task at hand. Recommend to clients to go outside during breaks and lunchtime to look upward at the trees, the hills, or the clouds. Each time one is distracted, return to appreciate the natural patterns. This mental break concludes by reminding oneself that humans are like trees.

Trees are rooted in the earth and reach upward to the light. Despite the trauma of being buffeted by the storms, they continue to reach upward. Similarly, clouds reflect the natural beauty of the world, and are often visible in the densest city environment. The upward movement reflects our intrinsic resilience and growth. –Erik Peper

Have clients place family photos and art slightly higher on the wall at home so they automatically look upward to see the pictures. A similar strategy can be employed in the office, using art to evoke positive feelings. When clients integrate an erect posture into their daily lives, they experience a more positive outlook and reduced neck and shoulder discomfort.

Compliance with Ethical Standards:

Conflict of Interest: Author Erik Peper has received donations of 15 UpRight posture feedback devices from UpRight (http://www.uprightpose.com/) and 12 BackJoy seat inserts from Backjoy (https://www.backjoy.com) for use in research. Co-authors I-Mei Lin and Richard Harvey declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This report evaluated a convenience sample of a student classroom activity related to posture and the information was anonymous collected. As an evaluation of a classroom activity, this report of findings was exempted from Institutional Review Board oversight

References:

Bakker Elkhuizen. (n.d.). Office employees are like professional athletes! (2017). Retrieved from https://www.bakkerelkhuizen.com/knowledge-center/whitepaper-improving-work-performance-with-insights-from-pro-sports/

Cuddy, A. (2012). Your body language shapes who you are. Technology, Entertainment, and Design (TED) Talk, available at: www.ted.com/talks/amy_cuddy_your_body_language_shapes_who_you_are

We thank Frank Andrasik for his constructive comments.

Posture affects memory recall and mood

Posted: November 25, 2017 Filed under: Exercise/movement, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: cognitive therapy, depression, empowerment, energy, helplessness, memory, mood, posture, power posture, somatics 5 CommentsThis blog has been reprinted from: Peper, E., Lin, I-M., Harvey, R., & Perez, J. (2017). How posture affects memory recall and mood. Biofeedback, 45 (2), 36-41.

When I sat collapsed looking down, negative memories flooded me and I found it difficult to shift and think of positive memories. While sitting erect, I found it easier to think of positive memories. -Student participant

The link between posture and mood is embedded in idiomatic phrases such as walking tall, standing proud, and an upstanding citizen, versus collapsed, defeated, or in a slump–Language suggests that posture and mood/emotions are connected. Slumped posture is commonly observed in depression (Canales et al., 2010; Michalak et al., 2009) and adapting an upright posture increases positive affect, reduces fatigue, and increases energy in people with mild to moderate depression (Wilkes et al., 2017; Peper & Lin, 2012).

The link between posture and mood is embedded in idiomatic phrases such as walking tall, standing proud, and an upstanding citizen, versus collapsed, defeated, or in a slump–Language suggests that posture and mood/emotions are connected. Slumped posture is commonly observed in depression (Canales et al., 2010; Michalak et al., 2009) and adapting an upright posture increases positive affect, reduces fatigue, and increases energy in people with mild to moderate depression (Wilkes et al., 2017; Peper & Lin, 2012).

This blog describes in detail our research study that demonstrated how posture affects memory recall (Peper et al, 2017). Our findings may explain why depression is increasing the more people use cell phones. More importantly, learning posture awareness and siting more upright at home and in the office may be an effective somatic self-healing strategy to increase positive affect and decrease depression.

Background

Most psychotherapies tend to focus on the mind component of the body-mind relationship. On the other hand, exercise and posture focus on the body component of the mind/emotion/body relationship. Physical activity in general has been demonstrated to improve mood and exercise has been successfully used to treat depression with lower recidivism rates than pharmaceuticals such as sertraline (Zoloft) (Babyak et al., 2000). Although the role of exercise as a treatment strategy for depression has been accepted, the role of posture is not commonly included in cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) or biofeedback or neurofeedback therapy.

The link between posture, emotions and cognition to counter symptoms of depression and low energy have been suggested by Wilkes et al. (2017) and Peper and Lin (2012), . Peper and Lin (2012) demonstrated that if people tried skipping rather than walking in a slouched posture, subjective energy after the exercise was significantly higher. Among the participants who had reported the highest level of depression during the last two years, there was a significant decrease of subjective energy when they walked in slouched position as compared to those who reported a low level of depression. Earlier, Wilson and Peper (2004) demonstrated that in a collapsed posture, students more easily accessed hopeless, powerless, defeated and other negative memories as compared to memories accessed in an upright position. More recently, Tsai, Peper, and Lin (2016) showed that when participants sat in a collapsed position, evoking positive thoughts required more “brain activation” (i.e. greater mental effort) compared to that required when walking in an upright position.

Even hormone levels also appear to change in a collapsed posture (Carney, Cuddy, & Yap, 2010). For example, two minutes of standing in a collapsed position significantly decreased testosterone and increased cortisol as compared to a ‘power posture,’ which significantly increased testosterone and decreased cortisol while standing. As Professor Amy Cuddy pointed out in herTechnology, Entertainment and Design (TED) talk, “By changing posture, you not only present yourself differently to the world around you, you actually change your hormones” (Cuddy, 2012). Although there appears to be controversy about the results of this study, the overall findings match mammalian behavior of dominance and submission. From my perspective, the concepts underlying Cuddy’s TED talk are correct and are reconfirmed in our research on the effect of posture. For more detail about the controversy, see the article by Susan Dominusin in the New York Times, “When the revolution came for Amy Cuddy,”, and Amy Cuddy’s response (Dominus, 2017;Singal and Dahl, 2016).

The purpose of our study is to expand on our observations with more than 3,000 students and workshop participants. We observed that body posture and position affects recall of emotional memory. Moreover, a history of self-described depression appears to affect the recall of either positive or negative memories.

Method

Subjects: 216 college students (65 males; 142 females; 9 undeclared), average age: 24.6 years (SD = 7.6) participated in a regularly planned classroom demonstration regarding the relationship between posture and mood. As an evaluation of a classroom activity, this report of findings was exempted from Institutional Review Board oversight.

Procedure

While sitting in a class, students filled out a short, anonymous questionnaire, which asked them to rate their history of depression over the last two years, their level of depression and energy at this moment, and how easy it was for them to change their moods and energy level (on a scale from 1–10). The students also rated the extent they became emotionally absorbed or “captured” by their positive or negative memory recall. Half of the students were asked to rate how they sat in front of their computer, tablet, or mobile device on a scale from 1 (sitting upright) to 10 (completely slouched).

Two different sitting postures were clearly defined for participants: slouched/collapsed and erect/upright as shown in Figure 1. To assume the collapsed position, they were asked to slouch and look down while slightly rounding the back. For the erect position, they were asked to sit upright with a slight arch in their back, while looking upward.

Figure 1. Sitting in a collapsed position and upright position (photo by Jana Asenbrennerova). Reprinted by permission from Gorter and Peper (2011).

Figure 1. Sitting in a collapsed position and upright position (photo by Jana Asenbrennerova). Reprinted by permission from Gorter and Peper (2011).

After experiencing both postures, half the students sat in the collapsed position while the other half sat in the upright position. While in this position, they were asked to recall/evoke as many hopeless, helpless, powerless, or defeated memories as possible, one after the other, for 30 seconds.

After 30 seconds they were reminded to keep their same position and let go of thinking negative memories. They were then asked to recall/evoke only positive, optimistic, or empowering memories for 30 seconds.

They were then asked to switch positions. Those who were collapsed switched to sitting erect, and those who were erect switched to sitting collapsed. Then they were again asked to recall/evoke as many hopeless, helpless, powerless, or defeated memories as possible one after the other for 30 seconds. After 30 seconds they were reminded to keep their same position and again let go of thinking of negative memories. They were then asked to recall/evoke only positive, optimistic, or empowering memories for 30 seconds, while still retaining the second posture.

They then rated their subjective experience in recalling negative or positive memories and the degree to which they were absorbed or captured by the memories in each position, and in which position it was easier to recall positive or negative experiences.

Results

86% of the participants reported that it was easier to recall/access negative memories in the collapsed position than in the erect position, which was significantly different as determined by one-way ANOVA (F(1,430)=110.193, p < 0.01) and 87% of participants reported that it was easier to recall/access positive images in the erect position than in the collapsed position, which was significantly different as determined by one-way ANOVA (F(1,430)=173.861, p < 0.01) as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Percent of respondents who reported that it was easier to recall positive or negative memories in an upright or slouched posture.

Figure 2. Percent of respondents who reported that it was easier to recall positive or negative memories in an upright or slouched posture.

The difficulty or ease of recalling negative or positive memories varied depending on position as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. The relative subjective rating in the ease or difficulty of recalling negative and positive memories in collapsed and upright positions.

Figure 3. The relative subjective rating in the ease or difficulty of recalling negative and positive memories in collapsed and upright positions.

The participants with a high level of depression over the last two years (top 23% of participants who scored 7 or higher on the scale of 1–10) reported that it was significantly more difficult to change their mood from negative to positive (t(110) = 4.08, p < 0.01) than was reported by those with a low level of depression (lowest 29% of the participants who scored 3 or less on the scale of 1–10). It was significantly easier for more depressed students to recall/evoke negative memories in the collapsed posture (t(109) = 2.55, p = 0.01) and in the upright posture (t(110) = 2.41, p ≦0.05 he) and no significant difference in recalling positive memories in either posture, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Differences is in memory access for participants with a history of least or most depression.

Figure 4. Differences is in memory access for participants with a history of least or most depression.

For all participants, there was a significant correlation (r = 0.4) between subjective energy level and ease with which they could change from negative to positive mood. There were no significance differences for gender in all measures except that males reported a significantly higher energy level than females (M = 5.5, SD = 3.0 and M = 4.7, SD = 3.8, respectively; t(203) = 2.78, p < 0.01).

A subset of students also had rated their posture when sitting in front of a computer or using a digital device (tablet or cell phone) on a scale from 1 (upright) to 10 (completely slouched). The students with the highest levels of depression over the last two years reporting slouching significantly more than those with the lowest level of depression over the last two years (M = 6.4, SD = 3.5 and M = 4.6, SD = 2.6; t(46) = 3.5, p < 0.01).

There were no other order effects except of accessing fewer negative memories in the collapsed posture after accessing positive memories in the erect posture (t(159)=2.7, p < 0.01). Approximately half of the students who also rated being “captured” by their positive or negative memories were significantly more captured by the negative memories in the collapsed posture than in the erect posture (t(197) = 6.8, p < 0.01) and were significantly more captured by positive memories in the erect posture than the collapsed posture (t(197) = 7.6, p < 0.01), as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Subjective rating of being captured by negative and positive memories depending upon position.

Figure 5. Subjective rating of being captured by negative and positive memories depending upon position.

Discussion

Posture significantly influenced access to negative and positive memory recall and confirms the report by Wilson and Peper (2004). The collapsed/slouched position was associated with significantly easier access to negative memories. This is a useful clinical observation because ruminating on negative memories tends to decrease subjective energy and increase depressive feelings (Michi et al., 2015). When working with clients to change their cognition, especially in the treatment of depression, the posture may affect the outcome. Thus, therapists should consider posture retraining as a clinical intervention. This would include teaching clients to change their posture in the office and at home as a strategy to optimize access to positive memories and thereby reduce access or fixation on negative memories. Thus if one is in a negative mood, then slouching could maintain this negative mood while changing body posture to an erect posture, would make it easier to shift moods.

Physiologically, an erect body posture allows participants to breathe more diaphragmatically because the diaphragm has more space for descent. It is easier for participants to learn slower breathing and increased heart rate variability while sitting erect as compared to collapsed, as shown in Figure 6 (Mason et al., 2017).

Figure 6. Effect of posture on respiratory breathing pattern and heart rate variability.

Figure 6. Effect of posture on respiratory breathing pattern and heart rate variability.

The collapsed position also tends to increase neck and shoulder symptoms This position is often observed in people who work at the computer or are constantly looking at their cell phone—a position sometimes labeled as the i-Neck.

Implication for therapy

In most biofeedback and neurofeedback training sessions, posture is not assessed and clients sit in a comfortable chair, which automatically causes a slouched position. Similarly, at home, most clients sit on an easy chair or couch, which lets them slouch as they watch TV or surf the web. Finally, most people slouch when looking at their cellphone, tablet, or the computer screen (Guan et al., 2016). They usually only become aware of slouching when they experience neck, shoulder, or back discomfort.

Clients and therapists are usually not aware that a slouched posture may decrease the client’s energy level and increase the prevalence of a negative mood. Thus, we recommend that therapists incorporate posture awareness and training to optimize access to positive imagery and increase energy.

References

Singal, J. and Dahl, M. (2016, Sept 30 ) Here Is Amy Cuddy’s Response to Critiques of Her Power-Posing Research. https://www.thecut.com/2016/09/read-amy-cuddys-response-to-power-posing-critiques.html

We thank Frank Andrasik for his constructive comments.

The surprising and powerful links between posture and mood

Posted: February 3, 2015 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: anxiety, depression, mind-body, posture, stress, stress management Leave a commentEnjoy Vivian Giang’s superb blog, The surprising and powerful links between posture and mood, published by Fast Company and reprinted with permission. It summarizes in a very readable way how posture affects health and well being.

The Surprising and Powerful Links between Posture and Mood

Why feeling taller tricks your brain into making you feel more confident and why your smartphone addiction might be making you depressed.

The next time you’re feeling sad and depressed, pay close attention to your posture. According to cognitive scientists, you’ll likely be slumped over with your neck and shoulders curved forward and head looking down.

While it’s true that you’re sitting this way because you’re sad, it’s also true that you’re sad because you’re sitting this way. This philosophy, known as embodied cognition, is the idea that the relationship between our mind and body runs both ways, meaning our mind influences the way our body reacts, but the form of our body also triggers our mind.

In large part due to Amy Cuddy’s widly popular 2012 TED talk, most of us know that two minutes of “power poses” a day can change how we feel about ourselves. This isn’t just about displaying confidence to others around; this is about actually changing your hormones—increased levels of testosterone and decreased levels of cortisol, or the stress hormone, in the brain.

“The brain has an area that reflects confidence, but once that area is triggered it doesn’t matter exactly how it’s triggered,” says Richard Petty, professor of psychology at Ohio State University. “It can be difficult to distinguish real confidence from confidence that comes from just standing up straight … these things go both ways just like happiness leads to smiling, but also smiling leads to happiness.”

When it comes to posture, Petty explains that the way we ultimately feel has a lot to do with the associations we have with being taller. For example, if you take two people and you put one on a chair that’s above the other person, the one that’s looking down will feel more powerful because “we have all these associations” with height and power that “gets triggered automatically when certain movements are made,” he says. The function of your body posture tells your brain that you’re powerful, which, in turn, affects your attitude.

In a 2009 study published in the European Journal of Social Psychology, Petty along with other researchers instructed 71 college students to either “sit up straight” and “push out [their] chest” or “sit slouched forward” with their “face looking at [their] knees.” While holding their assigned posture, the students were asked to list either three positive or negative personal traits they thought would contribute to their future job satisfaction and professional performance. Afterward, the students were asked to take a survey where they rated themselves on how well they thought they would perform as a future professional.

The researchers found that how the students rated themselves depended on the posture they kept when they wrote the positive or negative traits. Those who were in the upright position believed in the positive and negative traits they wrote down while those in the slouched over position weren’t convinced of their positive or negative traits. In other words, when the students were in the upright, confident position, they trusted their own thoughts whether those thoughts were positive or negative. On the other hand, when the students sat in a powerless position, they didn’t trust anything they wrote down whether it was positive or negative.

However, those in the upright position likely had an easier time thinking of “empowering, positive” traits about themselves to write down while those in the slouched over position probably had an easier time recalling “hopeless, helpless, powerless, and negative” feelings, according to Erik Peper, professor of Holistic Health at San Francisco State University.

In a series of experiments, Peper found that sitting in a collapsed, helpless position makes it easier for negative thoughts and memories to appear while sitting in an upright, powerful position makes it easier to have empowering thoughts and memories.

“Emotions and thoughts affect our posture and energy levels; conversely, posture and energy affect our emotions and thoughts,” says one of Peper’s studies from 2012, and two minutes of skipping versus walking in a slouched position can make a significant difference on our energy levels. Like Cuddy, Peper’s research finds that it only takes two minutes to change your hormones, meaning you can basically change the chemistry in your brain while waiting for your food to heat up in the microwave.

Since posture affects our mood and thoughts so much, the increase of collapsed sitting and walking—from sitting in front of our computer to looking down at our smartphones—may very much have an effect on the rise of depression in recent years. Peper and his team of researchers suggest that posture is a significant contributor to decreased energy levels and depression. Slouching is also known to result in frequent headaches and neck and shoulder pains.

With so much research proving the influence posture has on our mind, Peper suggests hanging photos of people you love slightly higher on the wall or above your desk so that you have to look up. Also, adjust your rear view mirror slightly higher so that you have to sit up taller while driving. If you need reminders, Petty advises setting reminders on your phone, computer, or even a Post-It note. When you do have negative thoughts, instead of validating them by slumping over or bending your head, Petty says that you should write them down on a piece of paper, then throw that piece of paper away in the trash.

“People who throw those negative thoughts into the trash can are less affected by them then people who had the same thoughts but symbolically put them in their pocket,” he says. “It’s this idea that it’s not what we think that’s important; it’s how much we trust what we think.”

Reprinted by permission from Vivian Giang

Adopt a power posture and change brain chemistry and probability of success

Posted: October 7, 2012 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: cortisol, posture, stress 3 CommentsLess than two minutes of body movement can increase or decrease energy level depending on which movement the person performs (Peper and Lin). Static posture has an even larger social impact—it affects how others see us and how we perform. Social psychologist Amy Cuddy, professor and researcher from Harvard Business School, has demonstrated that by adopting a posture of confidence for two minutes—even when you just fake it—significantly improves yourchances for success and your brain chemistry. The power position significantly increases testosterone and decreases cortisol levels in our brain. If you want to improve performance and success, watch Professor Amy Cuddy’s inspiring Ted talk (http://www.ted.com/talks/amy_cuddy_your_body_language_shapes_who_you_are.html)

Take charge of your energy level and depression with movement and posture

Posted: September 30, 2012 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: depression, energy level, exercise, posture 14 CommentsI felt depressed when I looked down walking slowly. I realized that I walk like that all the time. I really need to change my walking pattern. When doing opposite arm and leg skipping, I had more energy. Right away I felt happy and free. I automatically smiled. –Student

Hunched forward at the computer, collapsed in front of the TV, bent forward with an I-pad and smart phone while answering emails, updating Facebook, playing games, reading or texting—these are all habits that may affect our energy level. Students may also experience a decrease in energy level and concentration when they slouch in their seats.