Use the power of your mind to transform health and aging

Posted: February 18, 2025 Filed under: attention, behavior, cancer, CBT, cognitive behavior therapy, COVID, education, health, meditation, mindfulness, Pain/discomfort, placebo, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: health, imimune function, longevity, mental-health, mind-body, nutrition, Reframing, wellness Leave a commentMost of the time when I drive or commute by BART, I listen to podcasts (e.g., Freakonomics, Hidden Brain, this podcast will kill you, Science VS, Huberman Lab). although many of the podcasts are highly informative; , rarely do I think that everyone could benefit from it. The recent podcast, Using your mind to control your health and longevity, is an exception. In this podcast, neuroscientist Andrew Huberman interviews Professor Ellen Langer. Although it is three hours and twenty-two minute long, every minute is worth it (just skip the advertisements by Huberman which interrupts the flow). Dr. Langer delves into how our thoughts, perceptions, and mindfulness practices can profoundly influence our physical well-being.

She presents compelling evidence that our mental states are intricately linked to our physical health. She discusses how our perceptions of time and control can significantly impact healing rates, hormonal balance, immune function, and overall longevity. By reframing our understanding of mindfulness—not merely as a meditative practice but as an active, moment-to-moment engagement with our environment—we can harness our mental faculties to foster better health outcomes. The episode also highlights practical applications of Dr. Langer’s research, offering insights into how adopting a mindful approach to daily life can lead to remarkable health benefits. By noticing new things and embracing uncertainty, individuals can break free from mindless routines, reduce stress, and enhance their overall quality of life. This podcast is a must-listen for anyone interested in the profound connection between mind and body. It provides valuable tools and perspectives for those seeking to take an active role in their health and well-being through the power of mindful thinking. It will change your perspective and improve your health. Listen to or watch the interview:

Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QYAgf_lfio4

Useful blogs to reduce stress

From Conflict to Calm: Reframing Stress and Finding Peace with Difficult People

Posted: February 6, 2025 Filed under: attention, behavior, Breathing/respiration, CBT, emotions, healing, health, Neck and shoulder discomfort, Pain/discomfort, stress management | Tags: anger, anger management, conflict resolution, Reframing, resentment 8 Comments

Adapted from: Peper, E. (2025, Feb 15). From Conflict to Calm: Reframing Stress and Finding Peace with Difficult People. Townsend Letter-Innovative Health Perspectives. https://townsendletter.com/from-conflict-to-calm-reframing-stress-and-finding-peace-with-difficult-people/

After living in our house for a few years, a new neighbor moved in next door. Within months, she accused us of moving things in her yard, blamed us when there was a leak in her house, dumped her leaves from her property onto other neighbors’ properties, and even screamed at her tenants to the extent that the police were called numerous times.

Just looking at her house through the window was enough to make my shoulders tighten and leave me feeling upset. When I drove home and saw her standing in front of her house, I would drive around the block one more time to avoid her while feeling my body contract. Often, when I woke up in the morning, I would already anticipate conflict with my neighbor. I would share stories of my disturbing neighbor and her antics with my friends. They were very supportive and agreed with me that she was crazy.

However, this did not resolve my anger, indignation, or the anxiety that was triggered whenever I saw her or thought of her. I spent far too much time anticipating and thinking about her, which resulted in tension in my own body—my heart rate would increase, and my neck and shoulders would tighten. I decided to change. I knew I could not change her; however, I could change my reactivity and perspective.

Thus, I practiced the “Pause and Recenter” technique described in the blog. At the first moment of awareness that I was thinking about her or her actions, I would change my posture by sitting up straight and looking upward, breathe lower and slower, and then, in my mind’s eye, send a thought of goodwill streaming to her like an ocean wave flowing through and around her in the distance. I choose to do this because I believe that within every person, no matter how crazy or cruel, there is a part that is good, and it is that part I want to support.

I repeated this many times—whenever I looked in the direction of her house or saw her in her yard. I also reframed her aggressive, negative behavior as her way of coping with her own demons. Three months later, I no longer react defensively. When I see her, I can say hello and discuss the weather without triggering my defensive reaction. I feel so much more at peace living where I am.

When stressed, angry, rejected, frustrated, or hurt, we so often blame the other person. The moment we think about that person or event, our anger, indignation, resentment, and frustration are triggered. We keep rehashing what happened. As we do this, we are unaware that we are reliving the past event and are often unaware of the harm we are doing to ourselves until we experience symptoms such as high blood pressure, gastrointestinal distress, insomnia, anxiety, or muscle tightness. As we think of the event or interact again with that person, our body automatically responds with a defense reaction as if we are actually being threatened. This response activates the defense to protect ourselves from harm— the person is not a threat like the saber-toothed tiger ready to attack. Yet we respond as if the person is the tiger.

This defense reaction activates our “fight or flight” responses and increases sympathetic activation so that we can run faster and fight more ferociously to survive; however, it reduces blood flow through the frontal cortex—a process that reduces our ability to think rationally (Willeumier, et al., 2011; van Dinther et al., 2024). When we become so upset and stressed that our mind is captured by the other person, it contributes to an increase in hypertension, myofascial pain, depression, insomnia, cardiovascular disease, and other chronic disorders (Russel et al., 2015; Suls, 2013; Duan et al., 2022).

Our initial response of sharing our frustrations with others is normal. It feels good to blame the other; however, over time, the only person who gets hurt is yourself (Fast & Tiedens, 2010; Lou et al., 2023). The time spent rehashing and justifying our feelings diminishes our time we are in the present moment or focus on upcoming opportunities.

We may not realize that we have a choice. We can keep living and reacting to past hurt or losses, or we can let go and/or forgive and make space for new opportunities. Although the choice is ours, it is often very challenging to implement—even with the best intentions—as we react automatically when reminded of the past hurt (seeing that person, anticipating meeting or actually meeting that person who caused the hurt, or being triggered by other events that evoke memories of the pain).

What can you do

If choose to change your response and reactivity, it does not mean you condone what happened or agree that the other person was right. You are just choosing to live your life and not continue to be captured and react to the previous triggers. Many people report that after implementing some of the practices described below or others stress management techniques frequently their automatic reactivity was significantly reduced. They report that their symptoms are reduced and have the freedom to live in present instead of being captured by the painful past.

Pause and recenter

Our automatic reaction to the trigger elicits a defense reaction that reduces our ability to think rationally. Therefore, the moment you anticipate or begin to react, take three very slow diaphragmatic breaths. As you inhale, allow your abdomen to expand; then, as you exhale slowlymake your yourself tall and look up. Looking up allows easier access to empowering and positive memories (Peper et al., 2017). Continue looking up and inhale slowly allow the abdomen to expand. Repeat this slow breath again.

On the third breath, while looking up, evoke a memory of someone in whose presence you felt at peace and who loves –you such as your grandmother, aunt or uncle or your dog. Reawaken that feeling associated with that memory. Allow a smile with soft eyes to come to your face as you experience the loving memory. Then, put your hands on your chest, take a breath as your abdomen to expands, and as you exhale, bring your hands away from your chest and stretch them out in front of you. At the same time, in your mind’s eye imagine sending good will to that person or conflict that previously evoked your stress response.

As you do this, you are not condoning what happened; instead, you are sending goodwill to that person’s positive aspect. From this perspective, everyone has an intrinsic component—however small—that some label as Christ nature or Buddha nature.

Why could this be effective? This practice short-circuits the automatic stress response and provides time to recenter. It interrupts ongoing rumination by shifting the mind away from thoughts about the person or event that induces stress and toward a positive memory. Evoking a loving memory from the past facilitates a reduction in arousal, evokes a positive mood, and decreases sympathetic nervous system activation (Speer & Delgado, 2017). Additionally, slower diaphragmatic breathing reduces sympathetic activation (Birdee et al., 2023; Siedlecki et al., 2022). By combining body and mind, we can pause and create the opportunity to respond positively rather than reacting with anger and hurt.

Practice sending goodwill the moment you wake up

So often when we wake up, we already anticipate the challenges and even the prospect of interacting with person or event heightens our defense reaction. Therefore, as soon as you wake up, sit at the edge of the bed, repeat the previous practice, Pause and Center. Then, as you sit at the edge of the bed, slightly smile with soft eyes, look up, inhale as your abdomen expand. Then, stamp your right foot into the floor while saying, “Today is a new day.” Next, inhale allowing your abdomen expand; as you look up, stamp your left foot on the floor while saying, “Today is a new day.” Finally, send goodwill to the person who previously triggered your defensive reaction.

Why could this be effective?

Looking up makes it easier to access positive memories and thoughts. Stamping your foot on the ground is a non-verbal expression of determination and anchors the thought of a new day, thereby focuses on new opportunities (Feldman, 2022).

Discuss your issue from the third-person perspective instead of the first-person perspective

When thinking, ruminating, talking, texting, or writing about the event, discuss it from the third-person perspective. Replace the first-person pronoun “I” with “she” or “he.” For example, instead of saying:

I was really pissed off when my boss criticized my work without giving any positive suggestions for improvement,

Say:

He was really pissed off when his boss criticized his work without offering any positive suggestions for improvement.

Why could this be effective? The act of substituting the third person pronoun for the first-person pronoun interrupts our automatic reactivity because it requires us to observe and change our language, which activating the frontal cortex. This process creates a psychological distance from our feelings, allowing for a more objective and calmer perspective on the situation. It effectively reducing stress by stepping back from the immediate emotional response (Moser et al., 2017). It means that you are no longer fully captured by the emotions, as you are simultaneously the observer of your own inner language and speech.

Compare yourself to others who are suffering more

When you feel sorry for yourself or hurt, take a breath, look upward, and compare yourself to others who are suffering much more. In that moment, consider yourself incredibly lucky compared to people enduring extreme poverty, bombings, or severe disfigurement. Be grateful for what you have.

Why could this be effective? The research data shows that if we have low self-esteem when we compare ourselves to people who are more successful (healthier, richer, or successful), we feel worse in comparison and if we compare ourselves to other who are suffering more we feel better (Aspinwall, & Taylor, 1993). The comparision relativize our suffering. Thus our own suffering become less significant compared to the other people’s severe suffering.

Research shows that when we compare ourselves to people who are more successful (healthier, richer, or more accomplished), we tend to feel worse—especially if we have low self-esteem. However, when we compare ourselves to others who are suffering more, we tend to feel better (Aspinwall, & Taylor, 1993). This comparison relativizes our suffering, making our own hardships and suffering seem less significant compared to the severe suffering of others.

Interrupt the stress response

When overwhelmed by a stress reaction, implement the recue techniques described in the article, Quick rescue techniques when stress (Peper, Oded and Harvey, 2024) and the blog to help reduce stress. https://peperperspective.com/2024/02/04/quick-rescue-techniques-when-stressed/

Conclusion

It is much easier to write and talk about these practices than to actually do them. Remembering and reminding yourself to implement them can be very challenging. It requires significant effort and commitment. In most cases, the benefits are not experienced immediately. However, when practiced many times over weeks and months, many people report feeling less resentment, experience a reduction in symptoms, and improvements in health and relationships.

*This blog was inspired by the podcast, No hard feelings, that featured psychologist Fred Luskin. It is an episode on Hidden Brain, produced by Shankar Vedantam (2025) and the wisdom taught by Dora Kunz (Kunz & Peper, 1983; Kunz and Peper, 1984a; Kunz and Peper, 1984b; Kunz and Peper, 1987).

Useful blog that complement the concepts in this blog

References

Aspinwall, L. G., & Taylor, S. E. (1993). Effects of social comparison direction, threat, and self-esteem on affect, self-evaluation, and expected success. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(5), 708–722. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.64.5.708

Birdee, G., Nelson, K., Wallston, K., Nian, H., Diedrich, A., Paranjape, S., Abraham, R., & Gamboa, A. (2023). Slow breathing for reducing stress: The effect of extending exhale. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2023.102937

Duan, S., Lawrence, A., Valmaggia, L., Moll, J. & Zahn, R. (2022). Maladaptive blame-related action tendencies are associated with vulnerability to major depressive disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 145, 70-76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.11.043

Fast, N.J. & Tiedens, L.Z. (2010). Blame contagion: The automatic transmission of self-serving attributions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46(1), 97-106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.10.007

Feldman, Y. (2022). The Dialogical Dance-A Relational Embodied Approach to Supervision. In Butte, C. & Colbert, T. (Eds). Embodied Approaches to Supervision-The Listening Body. London: Routledge. https://www.amazon.com/Embodied-Approaches-Supervision-C%C3%A9line-Butt%C3%A9/dp/0367473348

Kunz, D. & Peper, E. (1983). Fields and Their Clinical Implications-Part III: Anger and How It Affects Human Interactions. The American Theosophist, 71(6), 199-203. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280777019_Fields_and_their_clinical_implications-Part_III_Anger_and_how_it_affects_human_interactions

Kunz, D. & Peper, E. (1984a). Fields and Their Clinical Implications IV: Depression from the Energetic Perspective: Etiological Underpinnings. The American Theosophist, 72(8), 268-275. https://biofeedbackhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/fields-and-their-clinical-implications-iv-depression-from-the-energetic-perspectivive.pdf

Kunz, D. & Peper, E. (1984b). Fields and Their Clinical Implications V: Depression from the Energetic Perspective: Treatment Strategies. The American Theosophist, 72(9), 299-306. https://biofeedbackhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/fields-and-their-clinical-implications-part-v-depression-treatment-strategies.pdf

Kunz, D. & Peper, E. (1987). Resentment: A poisonous undercurrent. The Theosophical Research Journal. IV (3), 54-59. Also in: Cooperative Connection. IX (1), 1-5. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/387030905_Resentment_Continued_from_page_4

Lou, Y., Wang, T., Li, H., Hu, T. Y., & Xie, X. (2023). Blame others but hurt yourself: blaming or sympathetic attitudes toward victims of COVID-19 and how it alters one’s health status. Psychology & Health, 39(13), 1877–1898. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2023.2269400

Moser, J. S., Dougherty, A., Mattson, W. I., Katz, B., Moran, T. P., Guevarra, D., Shablack, H., Ayduk, O., Jonides, J., Berman, M. G., & Kross, E. (2017). Third-person self-talk facilitates emotion regulation without engaging cognitive control: Converging evidence from ERP and fMRI. Scientific reports, 7(1), 4519. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-04047-3

Oneda, B., Ortega, K., Gusmão, J. et al. (2010). Sympathetic nerve activity is decreased during device-guided slow breathing. Hypertens Res, 33, 708–712. https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2010.74

Peper, E., Oded, Y, & Harvey, R. (2024). Quick somatic rescue techniques when stressed. Biofeedback, 52(1), 18–26. https://doi.org/10.5298/982312

Peper, E., Lin, I-M., Harvey, R., & Perez, J. (2017). How posture affects memory recall and mood. Biofeedback.45 (2), 36-41. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-45.2.01

Russell, M. A., Smith, T. W., & Smyth, J. M. (2016). Anger Expression, Momentary Anger, and Symptom Severity in Patients with Chronic Disease. Annals of behavioral medicine : a publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 50(2), 259–271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-015-9747-7

Siedlecki, P., Ivanova, T.D., Shoemaker, J.K. et al. (2022). The effects of slow breathing on postural muscles during standing perturbations in young adults. Exp Brain Res, 240, 2623–2631. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-022-06437-0

Speer, M. & Delgado, M. (2017).Reminiscing about positive memories buffers acute stress responses. Nat Hum Behav 1, 0093 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-017-0093

Suls J. (2013). Anger and the heart: perspectives on cardiac risk, mechanisms and interventions. Progress in cardiovascular diseases, 55(6), 538–547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2013.03.002

van Dinther, M., Hooghiemstra, A. M., Bron, E. E., Versteeg, A., Leeuwis, A. E., Kalay, T., Moonen, J. E., Kuipers, S., Backes, W. H., Jansen, J. F. A., van Osch, M. J. P., Biessels, G. J., Staals, J., van Oostenbrugge, R. J., & Heart-Brain Connection consortium (2024). Lower cerebral blood flow predicts cognitive decline in patients with vascular cognitive impairment. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, 20(1), 136–144. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.13408

Vedantma, S. (2025). Hidden Brain episode, No hard feelings. Accessed February 5, 2025. https://hiddenbrain.org/podcast/no-hard-feelings/

Willeumier, K., Taylor, D. V., & Amen, D. G. (2011). Decreased cerebral blood flow in the limbic and prefrontal cortex using SPECT imaging in a cohort of completed suicides. Translational psychiatry, 1(8), e28. https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2011.28

Act now before history repeats itself

Posted: January 23, 2025 Filed under: education | Tags: Brexit, Gladwell, history, Musk, Nazi, Politics, Trump 20 CommentsOn November 8–9, 1923, Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party launched a bold attempt to overthrow Germany’s federal government in Munich, aiming to establish a nationalist regime. Known as the Beer Hall Putsch, this failed coup grabbed global headlines, shocking the world. Hitler and his associates were quickly arrested, and after a dramatic 24-day trial, they were convicted of treason. Despite being sentenced to prison, Hitler served less than a year before his release—time he used to lay the groundwork for his infamous future.

Fast forward to January 6, 2021: history echoed in eerie ways. Fueled by false claims of a stolen election, groups like the Oath Keepers and Proud Boys, with the backing of then-President Donald Trump, stormed the U.S. Capitol in a desperate bid to block Joe Biden’s certification as the newly elected President. The attack left the nation reeling, its democratic institutions shaken.

By August 2024, over 1,400 individuals had been charged with federal crimes related to the insurrection, and more than 900 had been convicted. Yet, in a shocking twist, Trump—returning to the presidency—undermined the justice system on his first day back in office. He issued sweeping pardons for approximately 1,500 individuals and commuted the sentences of 14 key allies connected to the Capitol attack.

Are we seeing echoes of 1930s Germany in today’s America? In 1935, the Nuremberg Laws stripped citizenship from anyone not deemed “Aryan,” cementing a dangerous precedent of exclusion and authoritarianism. Now on the first day in office, President Trump President Donald Trump’s executive order that purports to limit birthright citizenship-

Fast forward to now: former President Donald Trump’s blanket clemency and pardons for Proud Boys and other January 6 participants seem to signal unconditional support for his loyal MAGA followers. The message is clear—carry out Trump’s agenda without fear of legal consequences because he’ll have your back. Could the Proud Boys become a modern-day equivalent of Hitler’s Brownshirts (Sturmabteilung, or SA)—used to protect Trump’s movement, suppress dissent, and disrupt political opposition? This question grows even more pressing in an age where social media wields enormous influence. With Elon Musk controlling X (formerly Twitter), critics worry about the platform’s role in shaping discourse. Musk’s actions and statements have led some to compare his influence to that of Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi Minister of Propaganda. My fears are heightened after Musk made gestures similarly to that associated with Nazi symbolism during Trump’s inauguration.

Read about the possible impact of the Trump policies in the New York Times, “Donald Trump Is Running Riot” by David French, the outstanding New York Times’ opinion writer.

How Did We Get Here? A Warning from History

How could this happen? It might seem that the majority of Americans support Trump’s actions, but the numbers tell a different story. In reality, only about 33% of eligible voters cast their ballots for Trump. Over one-third of eligible voters stayed home, choosing not to vote at all. To put it in perspective, Trump’s 2024 total of 77,284,118 votes fell short of Biden’s 81,284,666 votes in 2020. The difference wasn’t that Trump gained overwhelming support—it was that fewer people showed up for Harris, and 36% did not vote.

This scenario isn’t unique to America. Take Brexit, for example: In January 2020, the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union, a decision driven by a passionate and sometimes misinformed minority. Now, just a few years later, many in England regret that choice, realizing the long-term consequences of their decision to leave the EU.

The truth is, in almost every major upheaval, it only takes about 30% of highly dedicated and committed individuals—some might even call them zealots—to shift the course of history. It was true for Brexit, it was true for Hitler, and is now true for Trump.

If you want to understand how this dynamic works, Malcolm Gladwell’s The Revenge of the Tipping Point offers invaluable insights into how a small but determined group can take control of the narrative and change the agenda for everyone.

Now is the time to act. It’s not too late to support democratic institutions and ensure the U.S. doesn’t slide into the abyss. Staying silent or staying home isn’t an option—democracy needs defenders–silence in the face of oppression is siding with the oppressor.

Compassionate Presence: Covert Training Invites Subtle Energies Insights

Posted: January 20, 2025 Filed under: attention, healing, meditation, mindfulness, relaxation, Uncategorized | Tags: being safe, compassion, energy, Energy healing, healing, reiki, spirituality, therapeutic touch Leave a commentAdapted from: Peper, E. (2015). Compassionate Presence: Covert Training Invites Subtle Energies Insights. Subtle Energies Magazine, 26(2), 22-25. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283123475_Compassionate_Presence_Covert_Training_Invites_Subtle_Energies_Insights

“Healing is best accomplished when art and science are conjoined, when body and spirit are probed together. Only when doctors can brood for the fate of a fellow human afflicted with fear and pain do they engage the unique individuality of a particular human being…a doctor thereby gains courage to deal with the pervasive uncertainties for which technical skill alone is inadequate. Patient and doctor then enter into a partnership as equals.

I return to my central thesis. Our health care system is breaking down because the medical profession has been shifting its focus away from healing, which begins with listening to the patient. The reasons for this shift include a romance with mindless technology.” Bernard Lown, MD, The Lost art of healing: Practicing Compassion in Medicine (1999)

Therapeutic Touch healing by Dora Kunz.

I wanted to study with the healer and she instructed me to sit and observe, nothing more. She did not explain what she was doing, and provided no further instructions. Just observe. I did not understand. Yet, I continued to observe because she knew something, she did something that seemed to be associated with improvement and healing of many patients. A few showed remarkable improvement – at times it seemed miraculous. I felt drawn to understand. It was an unique opportunity and I was prepared to follow her guidance.

The healer was remarkable. When she put her hands on the patient, I could see the patient’s defenses melt. At that moment, the patient seemed to feel safe, cared for, and totally nurtured. The patient felt accepted for just who she was and all the shame about the disease and past actions appeared to melt away. The healer continued to move her hands here and there and, every so often, she spoke to the client. Tears and slight sobbing erupted from the client. Then, the client became very peaceful and quiet. Eventually, the session was finished and the client expressed gratitude to the healer and reported that her lower back pain and the constriction around her heart had been released, as if a weight had been taken from her body.

How was this possible? I had so many questions to ask the healer: “What were you doing? What did you feel in your hands? What did you think? What did you say so softly to the client?”

Yet she did not help me understand how I could do this. The main instruction the healer kept giving me was to observe. Yes, she did teach me to be aware of the energy fields around the person and taught me how I could practice therapeutic touch (Kreiger, 1979; Peper, 1986; Kunz & Peper,1995; Kunz & Krieger, 2004; Denison, 2004; van Gelder & Chesley, F, 2015). But she was doing much more and I longed to understand more about the process.

Sitting at the foot of the healer, observing for months, I often felt frustrated as she continued to insist that I just observe. How could I ever learn from this healer if she did not explain what I should do! Does the learning occur by activating my mirror neurons (Acharya & Shukla, 2012).? Similar instructions are common in spiritual healing and martial arts traditions – the guru or mentor usually tells an apprentice to observe and be there. But how can one gain healing skills or spiritual healing abilities if you are only allowed to observe the process? Shouldn’t the healer be demonstrating actual practices and teaching skills?

After many sessions, I finally realized that the healer’s instruction to to learn was to observe and observe. I began to learn how to be present without judging, to be present with compassion, to be present with total awareness in all senses, and to be present without frustration. The many hours at the foot of this master were not just wasted time. It eventually became clear that those hours of observation were important training and screening strategies used to insure that only those students who were motivated enough to master the discipline of non-judgmental observation, the discipline to be present and open to any experience, would continue to participate in the training process. I finally understood. I was being taught a subtle energies skill of compassionate, and mindful awareness. Once I, the apprentice, achieved this state, I was ready to begin work with clients and master technical aspects of the healing practice – but not before.

A major component of the healing skill that relies on subtle energies is the ability to be totally present with the client without judgment (Peper, Gibney & Wilson, 2005). To be peaceful, caring, and present seems to create an energetic ambiance that sets stage, creates the space, for more subtle aspects of the healing interaction. This energetic ambiance is similar to feeling the love of a grandparent: feeling total acceptance from someone who just knows you are a remarkable human being. In the presence of a healer with such a compassionate presence, you feel safe, accepted, and engaged in a timeless state of mind, a state that promotes healing and regeneration as it dissolves long held defensiveness and fear-based habits of holding others at bay. This state of mind provides an opportunity for worries and unsettled emotions to dissipate. Feeling safe, accepted, and experiencing compassionate love supports the bological processes that nurture regeneration and growth.

How different this is from the more common experience with health care/medical practitioners who have little time to listen and to be with a patient. We might experience a medical provider as someone who sees us only as an illness (the cancer patient, the asthma patient) instead of recognizing us as a human spirit who happens to have an illness ( a person with cancer or asthma). At times we can feel as though we are seen only as a series of numbers in a medical chart – yet we know we are more than that. People long to be seen. Often the medical provider interrupts with unrelated questions instead of listening. It becomes clear that the computerized medical record is more important than the human being seated there. We can feel more fragmented, less safe, when we are not heard, not understood.

As one 23 year old student reported after being diagnosed with a serious medical condition,”/ cried immediately upon leaving the physician’s office. Even though he is an expert on the subject, I felt like I had no psychological support. I was on Gabapentin, and it made me very depressed. I thought to myself: Is my life, as I know it, over?” (Peper, Martinez Aranda, P., & Moss, 2015).

The healing connection is often blocked, the absence of a human connection is so obvious. The medical provider may be unaware of the effect of their rushed behavior and lack of presence. They can issue a diagnosis based on the scientific data without recognizing the emotional impact on the person receiving it.

What is missing is compassion and caring for the patient. Sitting at the foot of the master healer is not wasted time when the apprentice learns how to genuinely attend to another with non-judgmental, compassionate presence. However, this requires substantial personal work. Possibly all healthcare providers should be required, or at least invited, to learn how to attain the state of mind that can enhance healing. Perhaps the practice of medicine could change if, as Bernard Lown wrote, the focus were once again on healing, “…which begins with listening to the patient.”

References

Acharya, S., & Shukla, S. (2012). Mirror neurons: Enigma of the metaphysical modular brain. Journal of natural science, biology, and medicine, 3(2), 118–124. https://doi.org/10.4103/0976-9668.101878

Denison, B. (2004). Touch the pain away: New research on therapeutic touch and persons with fibromyalgia syndrome. Holistic nursing practice, 18(3), 142-151. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004650-200405000-00006

Krieger, D. (1979). The therapeutic touch: How to use your hands to help or to heal. Vol. 15. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. https://www.amazon.com/Therapeutic-Touch-Your-Hands-Help/dp/067176537X

Kunz, D. & Krieger, D. (2004). The spiritual dimension of therapeutic touch. Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions/Bear & Co. https://www.amazon.com/Spiritual-Dimension-Therapeutic-Touch/dp/1591430259/

Kunz, D., & Peper, E. (1995). Fields and their clinical implications. In Kunz, D. Spiritual Aspects of the Healing Arts. Wheaton, ILL: Theosophical Pub House, 213-222. https://www.amazon.com/Spiritual-Aspects-Healing-Arts-Quest/dp/0835606015

Lown, B. (1999). The lost art of healing: Practicing compassion in medicine. New York, NY: Ballantine Books. https://www.amazon.com/Lost-Art-Healing-Practicing-Compassion/dp/0345425979

Peper, E. (1986). You are whole through touch: An energetic approach to give support to a breast cancer patient. Cooperative Connection. VII (3), 1-6. Also in: (1986/87). You are whole through touch: Dora Kunz and Therapeutic Touch. Somatics. VI (1), 14-19. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280884245_You_are_whole_through_touch_Dora_Kunz_and_therapeutic_touch

Peper, E. (2024). Reflections on Dora and the Healing Process, webinar presented to the Therapeutic Touch International Association, Saturday, December 14, 2024. https://youtu.be/skq9Chn-eME?si=HJNAhiUsgXSkqd_5

Peper, E., Gibney, K. H. & Wilson, V. E. (2005). Enhancing Therapeutic Success–Some Observations from Mr. Kawakami: Yogi, Teacher, Mentor and Healer. Somatics. XIV (4), 18-21. https://biofeedbackhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/edited-enhancing-therapeutic-success-8-23-05.pdf

Peper, E., Martinez Aranda, P., & Moss, E. (2015). Vulvodynia treated successfully with breathing biofeedback and integrated stress reduction: A case report. Biofeedback, 43(2), 103-109. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-43.2.04

Van Gelder, K & Chesley, F. (2015). A Most Unusual Life. Wheaton Ill: Theosophical Publishing House. https://www.amazon.com/Most-Unusual-Life-Clairvoyant-Theosophist/dp/0835609367

[1] I thank Peter Parks for his superb editorial support.

Implement your New Year’s resolution successfully[1]

Posted: December 29, 2024 Filed under: attention, behavior, CBT, cognitive behavior therapy, education, emotions, Exercise/movement, healing, health, self-healing | Tags: goal setting, health, lifestyle, motivation, performance, personal-development Leave a comment

Adapted from: Peper, E. Pragmatic suggestions to implement behavior change. Biofeedback.53(2), 41-45. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-53.02.05

Ready to crush your New Year’s resolutions and actually stick to them this time? Whether you’re determined to quit vaping or smoking, cut back on sugar and processed foods, reduce screen time, get moving, volunteer more, or land that dream job, sticking to your goals is the real challenge. We’ve all been there: kicking off the year with ambitious plans like, “I’ll work out every day,” or “I’m done with junk food for good.” But a few weeks in? The gym is a distant memory, the junk food stash is back, and those cigarettes are harder to let go of than expected.

So, how can you make this year different? Here are some tried-and-true tips to help you turn those resolutions into lasting habits:

Be clear of your goal and state exactly what you want to do (Pilcher et al., 2022; Latham & Locke, 2006).

Did you know your brain is super literal and doesn’t process “not” the way you think it does? For example, if you say, “I will not smoke,” your brain has to first imagine you smoking, then mentally cross it out. Guess what? By rehearsing the act of smoking in your mind, you’re actually increasing the chances that you’ll light up again.

Think of it like this: hand a four-year-old a cup of hot chocolate and ask them to walk it over to someone across the room. Halfway there, you call out, “Be careful, don’t spill it!” What usually happens? Yep, the hot chocolate spills. That’s because the brain focuses on “spill,” not the “don’t.” Now, imagine instead you say, “You’re doing great! Keep walking steadily.” Positive framing reinforces the action you want to see. The lesson is to reframe your goals in a way that focuses on what you want to achieve, not what you’re trying to avoid. Let’s look at some examples to get you started:

| Negative framing | Positive framing |

| I plan to stop smoking | I choose to become a nonsmoker |

| I will eat less sugar and ultra-processed foods | I will shop at the farmer’s market, buy more fresh vegetable and prepare my own food. |

| I will reduce my negative thinking (e.g., the glass is half empty). | I will describe events and thoughts positively (e.g., the class is half full). |

Describe what you want to do positively.

Be precise and concrete.

The more specific you can describe what you plan to do, the more likely will it occur as illustrated in the following examples.

| Imprecise | Concrete and specific |

| I will begin exercising. | I will buy the gym membership next week Monday and will go to the gym on Monday, Wednesday and Friday right after work at 5:30pm for 45 minutes. |

| I will reduce my angry outbursts, | Before I respond, I will take a slow breath, look up, relax my shoulders and remind myself that the other person is doing their best. |

| I want to limit watching streaming videos | At home, I will move the couch so that it does not face the large TV screen, and I have enrolled in a class to learn another language and I will spent 30 minutes in the evening practicing the new language. |

| I will stop smoking | When I feel the initial urge to smoke, I stand up, do a few stretches, and practice box breathing and remind myself that I am a nonsmoker. |

Describe in detail what you will do.

Identify the benefits of the old behavior that you want to change and how you can achieve the same benefits with your new behavior. (Peper et al, 2002)

When setting a New Year’s resolution, it’s easy to focus on the perks of the new behavior and the harms of the old behavior while overlooking the benefits your old habit provided. However, if you don’t plan ways to achieve the same benefits, the old behavior provided, it’s much harder to stick to your goal.

Before diving into your new resolution, take a moment to reflect. What did your old behavior do for you? What needs did it meet? Once you identify those, you can develop strategies to achieve the same benefits in healthier, more constructive ways.

For example, let’s say your goal is to stop smoking. Smoking might have helped you relax during stressful moments or provided a social activity with friends. To make the switch, you’ll need to find alternatives that deliver similar results, like practicing deep-breathing exercises to manage stress or inviting friends for a walk instead of a smoke break. By creating a plan to meet those needs, you’ll set yourself up for lasting success.

| Benefits of smoking | How to achieve the same benefits when being a none smoker |

| Stress reduction | I will learn relaxation and diaphragmatic breathing. The moment, I feel the urge to smoke, I sit up, look up, raise my shoulder and dropped them, and breathe slowly |

| Breaks during work | I will install a reminder on my cellphone to ping and each time it pings, I stop, stand up, walk around and stretch. |

| Meeting with friends | I will tell my friends, not to offer me a cigarette and I will spent time with friends who are non-smokers. |

| Rebelling against my parents who were opposed to smoking | I will explore how to be independent without smoking |

Describe your benefits and how you will achieve them.

Reduce the cues that evoke the old behavior and create new cues that will trigger the new behavior (Peper & Wilson, 2021).

A lot of our behavior is automatic—shaped by classical conditioning, just like Pavlov’s dog. Remember the famous experiment? Pavlov paired the sound of a bell with food, and after a while, the bell alone made the dog salivate (McLeod, 2024). We’re not so different.

Think about it: if you’ve gotten into the habit of smoking in your car, simply sitting in the driver’s seat can trigger the automatic urge to grab a cigarette. Or, if you tend to feel depressed when you’re home but better when you’re out with friends, your home environment might be acting as a cue for those feelings.

Interestingly, many people find it easier to change habits in a new environment. Why? Because there are no built-in triggers to reinforce the behavior they’re trying to change. This highlights how much of what we often call “addiction” might actually be conditioned behavior, reinforced by familiar cues in our surroundings. By recognizing the power of these triggers can help you disrupt old patterns. By creating a fresh environment or consciously changing your responses to cues, you can take control and start forming new, healthier habits.

This concept has been understood for centuries by some hunting and gathering societies. When something tragic happened—like the death of a family member in a hut—the community would often burn the hut to “eliminate the evil spirit.” Beyond the spiritual aspect, this practice served a practical purpose: it removed all the physical cues that reminded people of their loss, making it easier to focus on the present and move forward.

Of course, I’m not suggesting you destroy your home. But the underlying principle still holds true in modern times. In fact, many Northern European cultures incorporate a version of this idea through the ritual of Spring Cleaning. By decluttering, rearranging furniture, and refreshing the home, the old cues are removed and create a sense of renewal.

So often we forget that cues in our environment play a powerful role in triggering our behavior. By identifying the triggers that evoke old habits and finding ways to remove or change them, you can create a fresh environment that supports your goals. For example, if you’re trying to stop snacking on junk food late at night, consider rearranging your pantry so the tempting items are out of sight—or better yet, replace them with healthier options. Small changes like this can have a big impact on your ability to stay on track.

| Cues that triggered the behavior | How cues were changed |

| In the evening going to the kitchen and getting the chocolate from the cupboard. | Buying fruits and have them on the table and not buying chocolate. If I do buy chocolate store it on the top shelf away so that I do not see it or store it in the freezer. |

| Getting home and being depressed. | Clean the house, change the furniture around and put positive picture high up on the wall. |

| Smoking in the car. | Replace the car with another car that no one had smoked in and spray the care with pine scent. |

Identify the cues that trigger your behavior and how you changed them.

Identify the first sensation that triggered the behavior you would like to change.

Whether it’s smoking, drinking, scratching your skin, spiraling into negative thoughts, or eating too many pastries, once a behavior starts, it can feel nearly impossible to stop. That’s why the key is to catch yourself before the habit takes over., t’s much easier to interrupt a pattern at the very first sign—the initial trigger—rather than after you’ve fully dived into the behavior. Yet how often do we find ourselves saying, “Next time, I’ll do it differently”?

Here’s the strategy: identify the first trigger. This could be a physical sensation, an emotion, a thought, or an external cue. Once you’re aware of that first flicker of a trigger, redirect your thoughts and actions toward what you actually want, rather than letting the automatic behavior take control. For example:

I just came home at 10:15 PM and felt lonely and slightly depressed. I walked into the kitchen, opened the fridge, grabbed a beer, and drank it. Then, I reached for another bottle.

Observing this behavior, the first trigger was the loneliness and slight depression upon arriving home. Recognizing that feeling in the moment offers an opportunity to pause and make a conscious choice. Instead of heading to the fridge, you could redirect your actions—call a friend, go for a quick walk, or write down your thoughts in a journal. By catching that initial trigger, you can focus yourself toward healthier behaviors and break the cycle.

| First sensation | Changed response to the sensation |

| I observed that the first sensation was feeling tired and lonely. | When I entered the house, instead of going to the kitchen, I stretched, looked up and took a deep breath and then called a close friend of mine. We talked for ten minutes and then I went to bed. |

Identify your first sensation and how you changed your behavior.

Incorporate social support and social accountability (Drageset, 2021).

Doing something on your own often requires a lot of willpower, and sticking to it every time can feel like an uphill battle. Take this example:

My goal is to exercise every other morning. But last night, I stayed up late and felt tired in the morning, so I skipped my workout.

Sound familiar? Now imagine if I’d planned to meet a workout buddy. Knowing someone was counting on me would’ve gotten me out of bed, even if I was tired, because I wouldn’t want to let them down.

Accountability can make all the difference. Another powerful strategy is sharing your goals publicly. When you announce your plans on social media or to friends and family, you create a sense of commitment—not just to yourself but to others. It’s like having a built-in support system cheering you on and holding you accountable. Whether it’s finding a partner, joining a group, or sharing your progress online, involving others can help turn your resolutions into habits you’re more likely to stick with.

Describe a strategy to increase social support and accountability.

Be honest in identifying what motivates you.

Exercising, eating healthy foods, thinking positively, or being on time are laudable goals; however, it often feels like work doing the “right” thing. To increase success, analyze what really helped you be successful. For example:

Many years ago, I decided that I should exercise more. Thus, I drove from house to the track and ran eight laps. I did this for the next three weeks and then stopped exercising. Eventually, I pushed myself again to exercise and after a while stopped again. The same pattern kept repeating. I would exercise and fall off the wagon and stop. Later that fall, I met a woman who was a jogger and we became friends and for the next year we jogged together and even did races. During this time, I did not experience any effort to go jogging. After a year, she broke up with me and once again, I had to use willpower to go jogging and my old pattern emerged and after a few days I stopped jogging even though I felt much better after having jogged.

I finally, asked what is going on? I realized that the joy of the jogging was running with a friend. Once, I recognized this, instead using will power to go running, I spent my willpower finding people with whom I could exercise. With these new friends, running did not depend upon my willpower– It only depended on making running dates with my new friends.

Explore factors that will allow you to do your activity without having to use willpower.

Conclusion

These seven strategies are just a starting point—there are countless other techniques that can help you stick to your New Year’s resolutions. For example, keeping a log, setting reminders, or rewarding yourself for progress are all powerful ways to stay on track. The real magic happens when your new behavior becomes part of your routine—embedded in your habitual patterns. The more automatic it feels, the greater your chances of long-term success.

So, take joy in identifying, implementing, and maintaining your resolutions. Let them enhance your well-being and become second nature. Share your successful strategies with me and others—it could be just the inspiration someone else needs to achieve their goals, too.

References

Drageset, J. (2021). Social Support. In: Haugan G, Eriksson M, editors. Health Promotion in Health Care – Vital Theories and Research [Internet]. Cham (CH): Springer, Chapter 11. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK585650/ https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-63135-2_11

Latham, G. P., & Locke, E. A. (2006). Enhancing the Benefits and Overcoming the Pitfalls of Goal Setting. Organizational Dynamics, 35(4), 332–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2006.08.008

McLeod, S. (2024). Classical Conditioning: How It Works With Examples.Simple Psychology. Accessed December 29, 2024. https://www.simplypsychology.org/classical-conditioning.html

Peper, E., Gibney, H. K. & Holt, C. (2002). Make Health Happen. Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall-Hunt. (Pp 185-192). https://he.kendallhunt.com/make-health-happen

Peper, E. & Wilson, V. (2021). Optimize the learning state: techniques and habits. Biofeedback, 9(2), 46-49. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-49-2-04

Pilcher, S., Schweickle, M. J., Lawrence, A., Goddard, S. G., Williamson, O., Vella, S. A., & Swann, C. (2022). The effects of open, do-your-best, and specific goals on commitment and cognitive performance. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 11(3), 382–395. https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000301

For detailed suggestions, see the following blogs:

[1] Edited with the help of ChatGPT.

Pragmatic techniques for monitoring and coaching breathing

Posted: December 14, 2024 Filed under: attention, behavior, biofeedback, Breathing/respiration, emotions, meditation, mindfulness, neurofeedback, Pain/discomfort, posture, relaxation, self-healing, Uncategorized | Tags: art, books, Breathing rate, coaching, FlowMD app, nasal breathing, personal-development, self-monitoring, writing 4 CommentsDaniella Matto, MA, BCIA BCB-HRV , Erik Peper, PhD, BCB, and Richard Harvey, PhD

Adapted from: Matto, D., Peper, E., & Harvey, R. (2025). Monitoring and coaching breathing patterns and rate. Townsend Letter-Innovative Health Perspectives. https://townsendletter.com/monitoring-and-coaching-breathing-patterns-and-rate/

This blog aims to describe several practical strategies to observe and monitor breathing patterns to promote effortless diaphragmatic breathing. The goal of these strategies is to foster effortless, whole-body diaphragmatic breathing that promote health.

Breathing is usually covert and people are not usually aware of their breathing rate (breaths per minute) or pattern (abdominal or thoracic, breath holding or shallow breathing) unless they have an illness such as asthma, emphysema or are performing physical activity (Boulding et al, 2015)). Observing breathing is challenging; awareness of respiration often leads to unaware changes in the breath pattern or to an attempt to breathe perfectly (van Dixhoorn, 2021). Ideally breathing patterns should be observed/monitored when the person is unaware of their breathing pattern and the whole body participates (van Dixhoorn, 2008). A useful strategy is to have the person perform a task and then ask, “What happened to your breathing?”. For example, ask a person to simulate putting a thread through the eye of a needle or quickly look to the extreme right and left while keeping their head still. In almost all cases, the person holds their breath (Peper et al., 2002).

Teaching effortless slow diaphragmatic breathing is a precursor of Heart rate variability (HRV) biofeedback and is based on slow paced breathing (Lehrer & Gevirtz, 2014; Steffen et al., 2017; Shaffer and Meehan, 2020). Mastering effortless diaphragmatic breathing is a powerful tool in the treatment of a variety of physical, behavioural, and cognitive conditions; however, to integrate this method into clinical or educational practice is easier said than done. Clients with dysfunctional breathing patterns often have difficulty following a breath pacer or mastering effortless breathing at a slower pace.

The purpose of this paper is to describe a few simple strategies that can be used to observe and monitor breathing patterns, provide economic strategies for observation and training, and suggestions to facilitate effortless diaphragmatic breathing.

Strategies to observe and monitor breathing pattern

Observation of the breathing patterns

- Is the breathing through the nose or mouth? Nose is usually better (Watso et al., 2023; Nestor, 2020).

- Does the abdomen expand during inhalation and constricts during exhalation or does the chest expand and rise during inhalation and fall during exhalation? Abdominal movement is usually better.

- Is exhalation flow softly or explosively like a sigh? Slow flow exhalation is preferred.

- Is the breath held or continues during activities? In most cases continued breathing is usually better.

- Does the person gasp before speaking or allows to speak while normally exhaling?

- What is the breathing rate (breaths per minute)? When sitting peacefully less than 14 breaths/minute is usually better and about 6 breaths per minute to optimize HRV

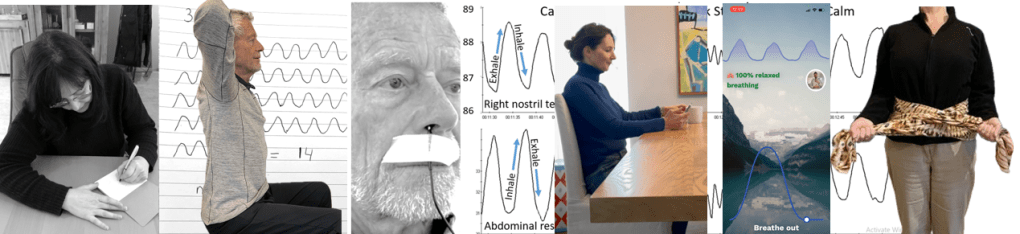

Physiological monitoring.

- Monitoring breathing with strain gauges around the abdomen and chest, and heart rate is the most common approach to identify the location of breath, the breathing pattern and heart rate variability. The strain gauges are placed around the chest and abdomen and heart rate is monitored with a blood volume pulse amplitude sensor from the finger. representative recording shows the effect of thoughts on breathing, heartrate and pulse amplitude of which the participant is totally unaware as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Physiological recording of breathing patterns with strain gauges.

- Monitoring breathing with a thermistor placed at the entrance of the nostril that has the most airflow (nasal patency) (Jovanov et al., 2001; Lerman et al., 2016). When the person exhales through the nose, the thermistor temperature increases and decreases when they inhale. A representative recording of a person being calm, thinking a stressful thought. and being calm. Although there were significant changes as indicated by the change in breathing patterns, the person was unaware of the changes as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Use of a thermistor to monitor breathing from the dominant nostril compared to the abdominal expansion as monitored by a strain gauge around the abdomen.

- Additional physiological monitoring approaches. There are many other physiological measures can be monitored to such as end-tidal carbon dioxide (EtCO2), a non-invasive measurement of the amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) in exhaled breath (Meuret et al., 2008; Meckley, 2013); scalene/trapezius EMG to identify thoracic breathing (Peper & Tibbett, 1992; Peper & Tibbets, 1994); low abdominal EMG to identify transfers and oblique tightening during exhalation and relaxation during inhalation (Peper et al., 2016; and heart rate to monitor cardiorespiratory synchrony (Shaffer & Meehan, 2020). Physiological monitoring is useful; since, the clinician and the participant can observe the actual breathing pattern in real time, how the pattern changes in response the cognitive and physical tasks, and used for feedback training. The recorded data can document breathing problems and evidence of mastery.

The challenges of using physiological monitoring arethat the equipment may be expensive, takes skill to operate and interpret the data, and is usually located in the office and not at home.

Economic strategies for observation and training breathing

To complement the physiological monitoring and allow observations outside the office and at home, some of the following strategies may be used to observe breathing pattern (rate and expansion of the breath in the body), and suggestion to facilitate effortless diaphragmatic breathing. These exercises make excellent homework for the client. Practicing awareness and internal self-regulation by the client outside the clinic contributes enormously to the effect of biofeedback training (Wilson et al., 2023),

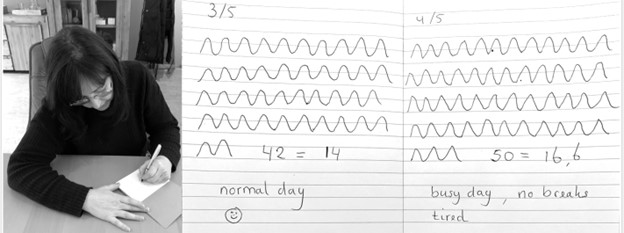

Observe breathing rate: Draw the breathing pattern

Take a piece of paper, a pen and a timer, set to 3 minutes. Start the timer. Upon inhalation draw the line up and upon exhalation draw the line down, creating a wave. When the timer stops, after 3 minutes, calculate the breathing rate per minute by dividing the number of waves by 3 as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Drawing the breathing pattern for three minutes during two different days.

From these drawings, the breathing rate become evident. Many individuals are often surprised to discover that their breathing rate increased during periods of stress, such as a busy day with no breaks, compared to their normal days.

Monitoring and training diaphragmatic breathing

The scarf technique for abdominal feedback

Many participants are unaware that they are predominantly breathing in their chest and their abdomen expansion is very limited during inhalation. Before beginning, have participant loosen their belt and or stand upright since sitting collapsed/slouched or having the waist constriction such as a belt of tight constrictive clothing that inhibits abdominal expansion during inhalation.

Place the middle part of a long scarf or shawl on your lower back, take the ends in both hands and cross the ends: your left hand is holding the right part of the scarf, and the right hand is holding the left end of the scarf. Give a bit of a pull, so you can feel any movement of the scarf. When breathing more abdominally you will feel a pull at the ends of the scarf as you lower back, and flanks will expand as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Using a scarf as feedback.

FlowMD app

A recent cellphone app, FlowMD, is unique because it uses the cellphone camera to detect the subtle movements of the chest and abdomen (FlowMD, 2024). It provides real time feedback of the persons breathing pattern. Using this app, the person sits in front of their cellphone camera and after calibration, the breathing pattern is displayed as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Training breathing with FlowMD,.

Suggestions to optimize abdominal breathing that may lead to a slower breath rate when the client practices the technique

Beach pose

By locking the upper chest and sitting up straight it is often easier to breathe so that the abdomen can expand and constrict. Place your hands behind your head and Interlock your finger of both hands, pull your elbows back and up. The person can practice this either laying down on their back or sitting straight up at the edge of the chair as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Sitting erect with the shoulders pulled back and up to allow abdominal expansion and constriction as the breathing pattern.

Observe the effect of posture on breathing

Have the person sit slouched/collapsed like a letter C and take a few slow breath, then have them sit up in a tall and erect position and take a few slow breaths. Usually they will observe that it is easier to breathe slower and lower and tall and erect.

Using your hands for feedback to guide natural breathing

Holding your hands with index fingers and thumbs touching the lower abdomen. When inhaling the fingers and thumbs separate and when exhaling they touch again (ensuring a full exhale and avoiding over breathing). The slight increase in lower abdominal muscle tension during the exhalation and relaxation during inhalation and the abdominal wall expands can also be felt with fingertips as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Using your hands and finger for feedback to guide the natural breathing of expansion and constriction of the abdomen. Reproduced by permission from Peper, E., Booiman, A., Lin, I-M, Harvey, R., & Mitose, J. (2016). Abdominal SEMG Feedback for Diaphragmatic Breathing: A Methodological Note. Biofeedback. 44(1), 42-49.

Coaching suggestions

There are many strategies to observe, teach and implement effortless breathing (Peper et al., 2024).. Even though breathing is natural and babies and young children breathe diaphragmatically as their large belly expands and constricts. Yet, in many cases the natural breathing shifts to dysfunctional breathing for multiple reasons such as chronic triggering defense reactions to avoiding pain following abdominal surgery (Peper et al, 2015). When participants initially attempt to relearn this natural pattern, it can be challenging especially, if the person habitually breathes shallowly, rapidly and predominantly in their chest.

When initially teaching effortless breathing, have the person exhale more air than normal without the upper chest compressing down and instead allow the abdomen comes in and up thereby exhaling all the air. If the person is upright then allow inhalation to occur without effort by letting the abdominal wall relaxes and expands. Initially inhale more than normal by expanding the abdomen without lifting the chest. Then exhale very slowly and continue to breathe so that the abdomen expands in 360 degrees during inhalation and constricts during exhalation. Let the breathing go slower with less and less effort. Usually, the person can feel the anus dropping and relaxing during inhalation.

Another technique is to ask the person to breathe in more air than normal and then breathe in a little extra air to completely fill the lungs, before exhaling fully. Clients often report that it teaches them to use the full capacity of the lungs.

The goal is to breath without effort. Indirectly this can be monitored by finger temperature. If the finger temperature decreases, the participant most likely is over-breathing or breathing with too much effort, creating sympathetic activity; if the finger temperature increases, breathing occurs slower and usually with less effort indicating that the person’s sympathetic activation is reduced.

Conclusion

There are many strategies to monitor and coach breathing. Relearning diaphragmatic breathing can be difficult due to habitual shallow chest breathing or post-surgical adaptations. Initial coaching may involve extended exhalations, conscious abdominal expansion, and gentle inhalation without chest movement. Progress can be monitored through indirect physiological markers like finger temperature, which reflects changes in sympathetic activity. The integration of these techniques into clinical or educational practice enhances self-regulation, contributing significantly to therapeutic outcomes. In this article we provided a few strategies which may be useful for some clients.

Additional blogs on breathing

https://peperperspective.com/2015/09/25/resolving-pelvic-floor-pain-a-case-report/

REFERENCES

Boulding, R., Stacey, R., & Niven, N. (2016). Dysfunctional breathing: a review of the literature and proposal for classification. European Respiratory Review, 25(141),: 287-294. https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0088-2015

FlowMD. (2024). FlowMD app. Accessed December 13, 2024. https://desktop.flowmd.co/

Jovanov, E., Raskovic, D., & Hormigo, R. (2001). Thermistor-based breathing sensor for circadian rhythm evaluation. Biomedical sciences instrumentation, 37, 493–497. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11347441/

Lehrer, P. & Gevirtz R. (2014). Heart rate variability biofeedback: how and why does it work? Front Psychol, 5,756. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00756

Lerman, J., Feldman, D., Feldman, R. et al. Linshom respiratory monitoring device: a novel temperature-based respiratory monitor. (2016). Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth, 63, 1154–1160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-016-0694-y

Meckley, A. (2013). Balancing Unbalanced Breathing: The Clinical Use of Capnographic Biofeedback. Biofeedback, 41(4), 183–187. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-41.4.02

Meuret, A. E., Wilhelm, F. H., Ritz, T., & Roth, W. T. (2008). Feedback of end-tidal pCO2 as a therapeutic approach for panic disorder. Journal of psychiatric research, 42(7), 560–568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.06.005

Nestor, J. (2020). Breath: The New Science of a Lost Art. New York: Riverhead Books. https://www.amazon.com/Breath-New-Science-Lost-Art/dp/0735213615/

Peper, E., Booiman, A., Lin, I-M, Harvey, R., & Mitose, J. (2016). Abdominal SEMG Feedback for Diaphragmatic Breathing: A Methodological Note. Biofeedback. 44(1), 42-49. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-44.1.03

Peper, E., Gilbert, C.D., Harvey, R. & Lin, I-M. (2015). Did you ask about abdominal surgery or injury? A learned disuse risk factor for breathing dysfunction. Biofeedback. 34(4), 173-179. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-43.4.06

Peper, E., Gibney, K.H., & Holt, C.F. (2002). Make Health Happen. Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company. https://he.kendallhunt.com/product/make-health-happen-training-yourself-create-wellness

Peper, E., Oded, Y., Harvey, R., Hughes, P., Ingram, H., & Martinez, E. (2024). Breathing for health: Mastering and generalizing breathing skills. Townsend Letter-Innovative Health Perspectives. November 15, 2024. https://townsendletter.com/suggestions-for-mastering-and-generalizing-breathing-skills/

Peper, E., & Tibbetts, V. (1992). Fifteen-month follow-up with asthmatics utilizing EMG/incentive inspirometer feedback. Biofeedback and self-regulation, 17(2), 143–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01000104

Peper, E. & Tibbetts, V. (1994). Effortless diaphragmatic breathing. Physical Therapy Products. 6(2), 67-71. https://biofeedbackhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/peper-and-tibbets-effortless-diaphragmatic.pdf

Shaffer, F. and Meehan, Z.M. (2020). A Practical Guide to Resonance Frequency Assessment for Heart Rate Variability Biofeedback. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 14. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnins.2020.570400

Steffen, P.R., Austin, T., DeBarros, A., and Brown, T. (2017). The Impact of Resonance Frequency Breathing on Measures of Heart Rate Variability, Blood Pressure, and Mood. Front Public Health, 5, 222. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00222

van Dixhoorn, J.V. (2008). Whole-body breathing. Biofeedback, 36,54–58. https://www.euronet.nl/users/dixhoorn/L.513.pdf

van Dixhoorn, J.V. (2021). Functioneel ademen-Adem-en ontspannings oefeningen voor gevorderden. Amersfoort: Uiteveriy Van Dixhoorn. https://www.bol.com/nl/nl/p/functioneel-ademen/9300000132165255/

Watso, J. C., Cuba, J.N., Boutwell, S.L, Moss, J…(2023). Acute nasal breathing lowers diastolic blood pressure and increases parasympathetic contributions to heart rate variability in young adults. American Journal of Physiology Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology.

325I(6), R797-R80. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.00148.2023

Wilson, V., Somers, K. & Peper, E. (2023). Differentiating Successful from Less Successful Males and Females in a Group Relaxation/Biofeedback Stress Management Program. Biofeedback, 51(3), 53–67. https://doi.org/10.5298/608570

[1] Correspondence should be addressed to:

Erik Peper, Ph.D., Institute for Holistic Health Studies, San Francisco State University, 1600 Holloway Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94132 Tel: 415 338 7683 Email: epeper@sfsu.edu web: www.biofeedbackhealth.org blog: www.peperperspective.com

Suggestions for mastering and generalizing breathing skills

Posted: October 30, 2024 Filed under: attention, behavior, biofeedback, Breathing/respiration, CBT, cellphone, cognitive behavior therapy, emotions, ergonomics, healing, health, mindfulness, Neck and shoulder discomfort, Pain/discomfort, posture, relaxation, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: abdominal beathing, anxiety, diaphragmatic braething, health, hyperventilation, meditation, mental-health, mindfulness, mouth breathing, Toning 3 CommentsAdapted from: Peper, E., Oded, Y., Harvey, R., Hughes, P., Ingram, H., & Martinez, E. (2024). Breathing for health: Mastering and generalizing breathing skills. Townsend Letter-Innovative Health Perspectives. November 15, 2024. https://townsendletter.com/suggestions-for-mastering-and-generalizing-breathing-skills/

Breathing techniques are commonly employed with complimentary treatments, biofeedback, neurofeedback or adjunctive therapeutic strategies to reduce stress and symptoms associated with excessive sympathetic arousal such as anxiety, high blood pressure, insomnia, or gastrointestinal discomfort. Even though it seems so simple, some participants experience difficulty in mastering effortless breathing and/or transferring slow breathing skills into daily life. The purpose of this article is to describe: 1) factors that may interfere with learning slow diaphragmatic breathing (also called cadence or paced breathing, HRV or resonant frequency breathing along with other names), 2) challenges that may occur when learning diaphragmatic breathing, and 3) strategies to generalize the effortless breathing into daily life.

Background

A simple two-item to-do list could be: ‘Breathe in, breathe out.’ Simple things are not always easy to master. Mastering and implementing effortless ‘diaphragmatic’ or ‘abdominal belly’ breathing may be simple, yet not easy. Breathing is a dynamic process that involves the diaphragm, abdominal, pelvic floor and intercostal muscles that can include synchronizing the functions of the heart and lungs and may result in cardio-respiratory synchrony or coupling, as well as ‘heart-rate variability breathing training (Codrons et al., 2014; Dick et al., 2014; Elstad et al., 2018; Maric et al., 2020; Matic et al., 2020). Improving heart-rate variability is a useful approach to reduce symptoms of stress and promotes health and reduce anxiety, asthma, blood pressure, insomnia, gastrointestinal discomfort and many other symptoms associated with excessive sympathetic activity (Lehrer & Gevirtz, 2014; Xiao et al., 2017; Jerath et al., 2019; Chung et al., 2021; Magnon et al., 2021; Peper et al., 2022).

Breathing can be effortful and In some cases people have dysfunctional breathing patterns such as breath holding, rapid breathing (hyperventilation), shallow breathing and lack of abdominal movement. This usually occurs without awareness and may contribute to illness onset and maintenance. When participants learn and implement effortless breathing, symptoms often are reduced. For example, when college students are asked to practice effortless diaphragmatic breathing twenty-minutes a day for one week, as well as transform during the day dysfunction breathing patterns into diaphragmatic breathing, they report a reduction in shallow breathing, breath holding,, and a decrease of symptoms as shown in Fig 1 (Peper et al, 2022).

Figure 1. Percent of people who reported that their initial symptoms improved after practicing slow diaphragmatic breathing for twenty minutes per day over the course of a week (reproduced from: Peper et al, 2022).

Most students became aware of their dysfunctional breathing and substituted slow, diaphragmatic breathing whenever they realized they were under stress; however, some students had difficulty mastering ‘effortless’ (e.g., automated, non-volitional) slow, diaphragmatic breathing that allowed abdominal expansion during inhalation.

Among those had more difficulty, they tended to have almost no abdominal movement (expansion during inhalation and abdominal constriction during exhalation). They tended to breathe shallowly as well as quickly in their chest using the accessory muscles of breathing (sternocleidomastoid, pectoralis major and minor, serratus anterior, latissimus dorsi, and serratus posterior superior).

The lack of abdominal movement during breathing reduced the movement of lymph as well as venous blood return in the abdomen; since; the movement of the diaphragm (the expansion and constriction of the abdomen) acts a pump. Breathing predominantly in the chest may increase the risk of anxiety, neck, back and shoulder pain as well as increase abdominal discomfort, acid reflux, irritable bowel, dysmenorrhea and pelvic floor pain (Banushi et al., 2023; Salah et al., 2023; Peper & Cohen, 2017; Peper et al., 2017; Peper et al., 2020, Peper et al., 2023). Learning slow, diaphragmatic or effortless breathing at about six breaths per minute (resonant frequency ) is also an ‘active ingredient’ in heartrate variability (HRV) training (Steffen et al., 2017; Shaffer & Meehan, 2020).

1. Factors that interfere with slow, diaphragmatic breathing

Difficulty allowing the skeletal and visceral muscles in the abdomen to expand or constrict in ‘three-dimensions’ (e.g., all around you in 360 degrees) during inhalation or exhalation. Whereas internal factors under volitional control and will mediate breathing practices, external factors can restrict and moderate the movement of the muscles. For example:

Clothing restrictions (designer jeans syndrome). The clothing is too tight around the abdomen; thereby, the abdomen cannot expand (MacHose & Peper, 1991; Peper et al., 2016). An extreme example were the corsets worn in the late 19th century that was correlated with numerous illnesses.

Suggested solutions and recommendations: Explain the physiology of breathing and how breathing occurs by the diaphragmatic movement. Discuss how babies and dogs breathe when they are relaxed; namely, the predominant movement is in the abdomen while the chest is relaxed. This would also be true when a person is sitting or standing tall. Discuss what happens when the person is eating and feels full and how they feel better when they loosen their waist constriction. When their belt is loosened or the waist button of their pants is undone, they usually feel better.

Experiential practice. If the person is wearing a belt, have the person purposely tighten their belt so that the circumference of the stomach is made much smaller. If the person is not wearing a belt, have them circle their waist with their hands and compress it so that the abdomen can not expand. Have them compare breathing with the constricted waist versus when the belt is loosened and then describe what they experienced.

Most participants will feel it is easier to breathe and much more comfortable when the abdomen is not constricted.

Previous abdominal injury. When a person has had abdominal surgery (e.g., Cesarean section, appendectomy, hernia repair, or episiotomy), they unknowingly may have learned to avoid pain by not moving (relaxing or tensing) the abdomen muscles (Peper et al., 2015; Peper et al., 2016). Each time the abdomen expands or constricts, it would have pulled on the injured area or stitches that would have cause pain. The body immediately learns to limit movement in the affected area to avoid pain. The reduction in abdominal movement becomes the new normal ‘feeling’ of abdominal muscle inactivity and is integrated in all daily activities. This is a process known as ‘learned disuse’ (Taub et al., 2006). In some cases, learned disuse may be combined with fear that abdominal movement may cause harm or injury such as after having a kidney transplant. The reduction in abdominal movement induces shallow thoracic breathing which could increase the risk of anxiety and would reduce abdominal venous and lymph circulation that my interfere with the healing.

Suggested solutions and recommendations. Discuss the concept of learned disuse and have participant practice abdominal movement and lower and slower breathing.

Experiential practices: Practicing abdominal movements

Sit straight up and purposely exhale while pulling the abdomen in and upward and inhale while expanding the abdomen. Even with these instructions, some people may continue to breathe in their chest. To limit chest movement, have the person interlock their hands and bring them up to the ceiling while going back as far as possible. This would lock the shoulders and allows the abdomen to elongate and thereby increase the diaphragmatic movement by allowing the abdomen to expand. If people initially have held their abdomen chronically tight then the initial expansion of abdomen by relaxing those muscle occurs with staccato movement. When the person becomes more skilled relaxing the abdominal muscles during inhalation the movement becomes smoother.

Make a “psssssst” sound while exhaling. Sit tall and erect and slightly pull in and up the abdominal wall and feel the anus tightening (pulling the pelvic floor up) while making the sound. Then allow inhalation to occur by relaxing the stomach and feeling the anus go down.

Use your hands as feedback. Sit up straight, placing one hand on the chest and another on the abdomen. While breathing feel the expansion of the abdomen and the contraction of the abdomen during exhalation. Use a mirror to monitor the chest-muscle movement to ensure there is limited rising and falling in this area.

Observe the effect of collapsed sitting. When sitting with the lower back curled, there is limited movement in the lower abdomen (between the pubic region and the umbilicus/belly button) and the breathing movement is shallower without any lower pelvic involvement (Kang et al., 2016). This is a common position of people who are working at their computer or looking at their cellphone.

Experiential practice: looking at your cellphone

Sit in a collapsed position and look down at your cellphone. Look at the screen and text as quickly as possible.

Compare this to sitting up and then lift the cell phone at eye level while looking straight ahead at the cellphone. Look at the screen and text as quickly as possible.