Welcome the New Year with Inspiration

Posted: December 22, 2025 Filed under: attention, behavior, CBT, cognitive behavior therapy, emotions, healing, health, mindfulness, self-healing | Tags: hope, Inspreiation, meaning, post=traumatic growth, purpose, resilience 1 CommentAs the holiday season begins, I find myself looking back on all that has unfolded this year and looking forward with hope to the year ahead. My social media feed is full of touching, uplifting messages and videos—reminders of resilience, creativity, and the simple goodness in the world. Best wishes for the holidays and the New Year and I hope you will enjoy the two inspiring videos.

1. Nine life lessons from comedian Tim Minchin, presented at the University of Western Australia. His humor and wisdom offer a refreshing take on what truly matters.

2. A powerful story about transforming disaster into blessing.

If you ever feel stuck or unsure about the future, this video is a beautiful reminder that unexpected turns can lead to new possibilities.

Wishing you a healthy and inspiring New Year!

Erik

Breathe Away Menstrual Pain- A Simple Practice That Brings Relief *

Posted: November 22, 2025 Filed under: attention, behavior, biofeedback, Breathing/respiration, cognitive behavior therapy, education, emotions, Neck and shoulder discomfort, Pain/discomfort, posture, relaxation, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: dysmenorrhea, health, meditation, menstrual cramps, mental-health, mindfulness, wellness 2 CommentsAdapted from: Peper, E. Harvey, R., Chen, & Heinz, N. (2025). Practicing diaphragmatic breathing reduces menstrual symptoms both during in-person and synchronous online teaching. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, Published online: 25 October 2025. https://rdcu.be/eMJqt https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-025-09745-7

“Once again, the pain starts—sharp, deep, and overwhelming—until all I can do is curl up and wait for it to pass. There’s no way I can function like this, so I call in sick. The meds take the edge off, but they don’t really fix anything—they just mask it for a little while. I usually don’t tell anyone it’s menstrual pain; I just say I’m not feeling well. For the next couple of days, I’m completely drained, struggling just to make it through.

Many women experience discomfort during menstruation, from mild cramps to intense, even disabling pain. When the pain becomes severe, the body instinctively responds by slowing down—encouraging rest, curling up to protect the abdomen, and often reaching for medication in hopes of relief. For most, the symptoms ease within a day or two, occasionally stretching into three, before the body gradually returns to balance.

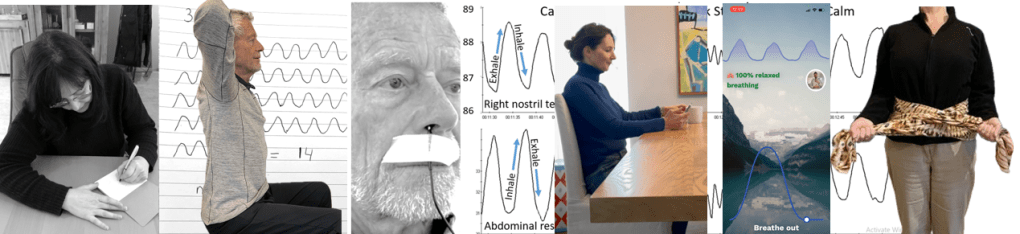

Another helpful approach is to practice slow abdominal breathing, guided by a breathing app FlowMD. In our study led by Mattia Nesse, PhD, in Italy, the response of one 22-year-old woman illustrated the power of this simple practice.

“Last night my period started, so I was a bit discouraged because I knew I’d get stomach pain, etc. On the other hand, I said, “Okay, let’s see if the breathing works,” and it was like magic — incredible. I’ll need to try it more times to understand whether it consistently has the same effect, but right now it truly felt magical. Just 3 minutes of deep breathing with the app were enough, and I’m not saying I don’t feel any pain anymore, but it has decreased a lot, so thank you! Thank you again for this tool… I’m really happy!”

The Silent Burden of Menstrual Pain

Menstrual pain, or dysmenorrhea, affects most women at some point in their lives — often silently. For many, the monthly cycle brings not only physical discomfort but also shame, fatigue, and interruptions to work or school. It is one of the leading causes of absenteeism and reduced productivity worldwide (Itani et al., 2022; Thakur & Pathania, 2022). In addition, the estimated health cost ranged from US $1367 to US$ 7043 per year (Huang et al., 2021). Yet, despite its prevalence, most women are never taught how to use their own physiology to ease these symptoms.

The Study (Peper et al, 2025)

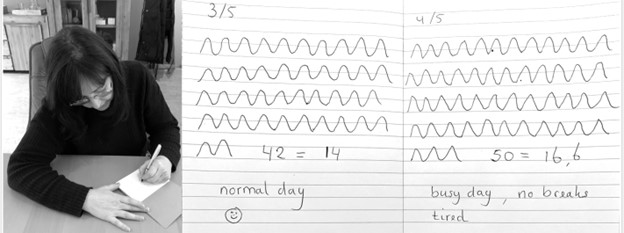

Seventy-five university women participated across two upper-division Holistic Health courses. Forty-nine practiced 30 minutes per day of breathing and relaxation over five weeks as well as practicing the moment they anticipated or felt discomfort; twenty-six served as a comparison group without a specific daily self-care routine. Students rated change in menstrual symptoms on a scale from –5 (“much worse”) to +5 (“much better”). For the detailed steps in training, see the blog: https://peperperspective.com/2023/04/22/hope-for-menstrual-cramps-dysmenorrhea-with-breathing/ (Peper et al., 2023).

What changed

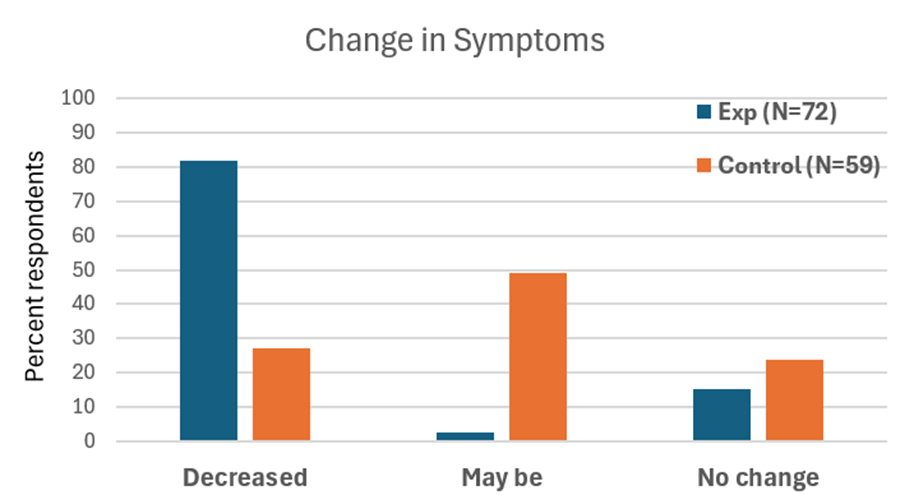

The results were striking. Women who practiced breathing and relaxation showed significant decrease in menstrual symptoms compared to the non-intervention group (p = 0.0008) as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Decrease in menstrual symptoms as compared to the control group after implementing slow diaphragmatic breathing.

Why does breathing and posture change have a beneficial effect?

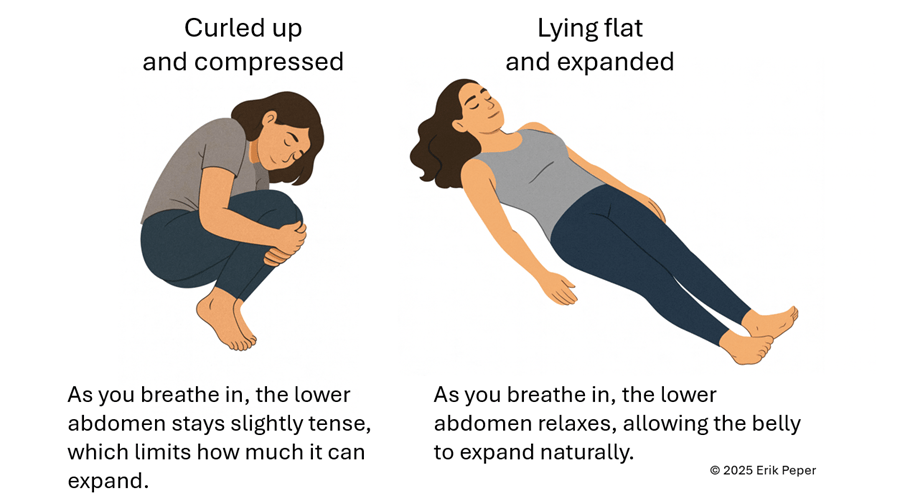

When you stay curled up, your abdomen becomes compressed, leaving little room for the lower belly to relax or for the diaphragm to move freely. The result? Tension builds, and pain often increases.

To reverse this, create space for relaxation. Gently loosen your waist and let your abdomen expand as you inhale. Uncurl your body—lengthen your spine and open your chest, as shown in Figure 2. With each easy breath, you invite calm and allow your body to shift from tension to ease.

Figure 2. Curling up compresses the abdomen and prevents relaxation of the lower belly. In contrast, lying flat with the body gently expanded allows the abdomen to move freely with each breath, which can help reduce menstrual discomfort.

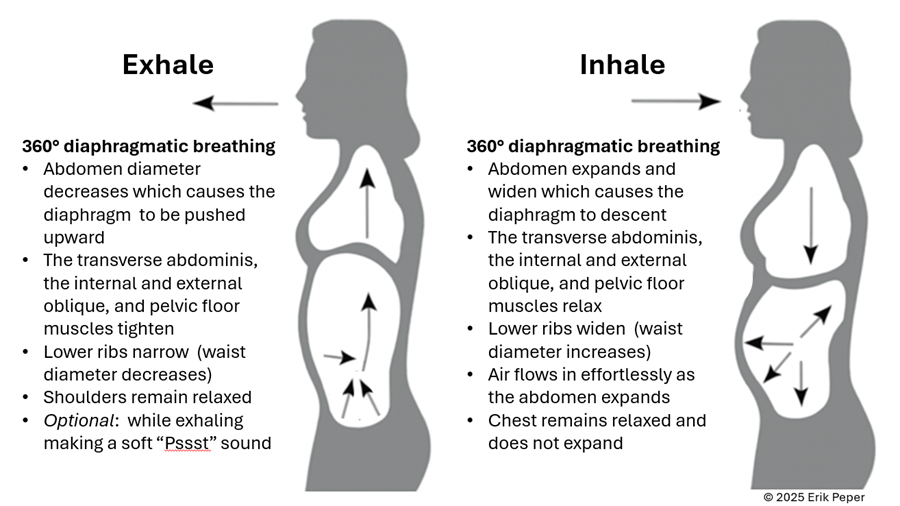

In contrast, slow abdominal or diaphragmatic breathing activates the body’s natural relaxation response. It quiets the stress-driven sympathetic nervous system, calms the mind, and improves circulation in the abdominal area. With each slow breath in, the abdomen gently expands while the pelvic floor and abdominal muscles relax. As you exhale, these muscles naturally tighten slightly, helping to massage and move blood and lymph through the abdominal region. This rhythmic movement supports healing and ease, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3. The dynamic process of diaphragmatic breathing.

The process of slower, lower diaphragmatic breathing

When lying down, rest comfortably on your back with your legs slightly apart. Allow your abdomen to rise naturally as you inhale and fall as you exhale. As you breathe out, imagine the air flowing through your abdomen, down your legs, and out through your feet. To deepen this sensation, you can ask a partner to gently stroke from your abdomen down your legs as you exhale—helping you sense the flow of release through your body.

Gently focus on slow, effortless diaphragmatic breathing. With each inhalation, your abdomen expands, and the lower belly softens. As you exhale, the abdomen gently goes down pushing the diaphragm upward and allowing the air to leave easily. Breathing slowly—about six breaths per minute—helps engage the body’s natural relaxation response.

If you notice that your breath is staying high in your chest instead of expanding through the abdomen, your symptoms may not improve and can even increase. One participant experienced this at first. After learning to let her abdomen expand with each inhalation while keeping her shoulders and chest relaxed, her next menstrual cycle was markedly easier and far less uncomfortable. The lesson is clear: technique matters.

“During times of pain, I practiced lying down and breathing through my stomach… and my cramps went away within ten minutes. It was awesome.” — 22-year-old college student

“Whenever I felt my cramps worsening, I practiced slow deep breathing for five to ten minutes. The pain became less debilitating, and I didn’t need as many painkillers.” — 18-year-old college student

These successes point out that it’s not just breathing — it’s how you breathe by providing space for the abdomen to expand during inhalation.

Practice: How to Do Diaphragmatic Breathing

- Find a quiet space. Lie on your back or sit comfortably erect with your shoulders relaxed.

- Place one hand on your chest and one on your abdomen.

- Inhale slowly through your nose for about 3–4 seconds. Let your abdomen expand as you breathe in — your chest should remain relaxed.

- Exhale gently through your mouth for 4—6 seconds, allowing the abdomen to fall or constrict naturally.

- As you exhale imagine the air moving down your arms, through your abdomen, down your legs, and out your feet

- Practice daily for 20 minutes and also for 5–10 minutes during the day when menstrual discomfort begins.

- Add warmth. Placing a warm towel or heating pad over your abdomen can enhance relaxation while lying on your back and breathing slowly.

With regular practice and implementing it during the day when stressed, this simple method can reduce cramps, promote calm, and reconnect you with your body’s natural rhythm.

Implement the ABCs during the day

The ABC sequence—adapted from the work of Dr. Charles Stroebel, who developed The Quieting Reflex (Stroebel, 1982)—teaches a simple way to interrupt stress reactions in real time. The moment you notice discomfort, pain, stress, or negative thoughts, interrupt the cycle with a simple ABC strategy:

A — Adjust your posture

Sit or stand tall, slightly arch your lower back and allowing the abdomen to expand while you inhale and look up. This immediately shifts your body out of the collapsed “defense posture’ and increases access to positive thoughts (Tsai et all, 2016; Peper et al., 2019)

B — Breathe

Allow your abdomen to expand as you inhale slowly and deeply. Let it get smaller as you exhale. Gently make a soft hissing sound as you exhale while helps the abdomen and pelvic floor to tighten. Then allow the abdomen to relax and widen which without effort draws the air in during inhalation. As you exhale, stay tall and imagine the air flowing through you and down your legs and out your feet.

C — Concentrate

Refocus your attention on what you want to do and add a gentle smile. This engages positive emotions, the smile helps downshift tension.

The video clip guides you through the ABCs process.

Integrate the breathing during the day by implementing your ABCs

When students practice relaxation technique and this method, they reported greater reductions in symptoms compared with a control group. By learning to notice tension and apply the ABC steps as soon as stress arises, they could shift their bodies and minds toward calm more quickly, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Change in symptoms after practicing a sequential relaxation and breathing techniques for four weeks.

Takeaway

Menstrual pain doesn’t have to be endured in silence or masked by medication alone. By practicing 30 minutes of slow diaphragmatic breathing daily and many times during the day, women may be able to reduce pain, stress, and discomfort — while building self-awareness and confidence in their body’s natural rhythms thereby having the opportunity to be more productive.

We recommend that schools and universities include self-care education—especially breathing and relaxation practices—as part of basic health curricula as this approach is scalable. Teaching young women to understand their bodies, manage stress, and talk openly about menstruation can profoundly improve well-being. It not only reduces physical discomfort but also helps dissolve the stigma that still surrounds this natural process,

Remember: Breathing is free—available anytime, anywhere and is helpful in reducing pain and discomfort. (Peper et al., 2025; Joseph et al., 2022)

See the following blogs for more in-depth information and practical tips on how to learn and apply diaphragmatic breathing:

REFERENCES

Itani, R., Soubra, L., Karout, S., Rahme, D., Karout, L., & Khojah, H.M.J. (2022). Primary Dysmenorrhea: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment Updates. Korean J Fam Med, 43(2), 101-108. https://doi.org/10.4082/kjfm.21.0103

Huang, G., Le, A. L., Goddard, Y., James, D., Thavorn, K., Payne, M., & Chen, I. (2022). A systematic review of the cost of chronic pelvic pain in women. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada, 44(3), 286–293.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogc.2021.08.011

Joseph, A. E., Moman, R. N., Barman, R. A., Kleppel, D. J., Eberhart, N. D., Gerberi, D. J., Murad, M. H., & Hooten, W. M. (2022). Effects of slow deep breathing on acute clinical pain in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Evidence-Based Integrative Medicine, 27, 2515690X221078006. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515690X221078006

Peper, E., Booiman, A. & Harvey, R. (2025). Pain-There is Hope. Biofeedback, 53(1), 1-9. http://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-53.01.16

Peper, E., Chen, S., Heinz, N., & Harvey, R. (2023). Hope for menstrual cramps (dysmenorrhea) with breathing. Biofeedback, 51(2), 44–51. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-51.2.04

Peper, E., Harvey, R., Chen, S., & Heinz, N. (2025). Practicing diaphragmatic breathing reduces menstrual symptoms both during in-person and synchronous online teaching. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. Published online: 25 October 2025. https://rdcu.be/eMJqt https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-025-09745-7

Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Hamiel, D. (2019). Transforming thoughts with postural awareness to increase therapeutic and teaching efficacy. NeuroRegulation, 6(3),153-169. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.6.3.1533-1

Stroebel, C. (1982). The Quieting Reflex. New York: Putnam Pub Group. https://www.amazon.com/Qr-Quieting-Charles-M-D-Stroebel/dp/0399126570/

Thakur, P. & Pathania, A.R. (2022). Relief of dysmenorrhea – A review of different types of pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments. MaterialsToday: Proceedings.18, Part 5, 1157-1162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2021.08.207

Tsai, H. Y., Peper, E., & Lin, I. M. (2016). EEG patterns under positive/negative body postures and emotion recall tasks. NeuroRegulation, 3(1), 23-27. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.3.1.23

*Edited with the help of ChatGPT 5

This May Save Your Life! Bacteriophage Treatment for Bacterial Diseases*

Posted: September 11, 2025 Filed under: Evolutionary perspective, healing, health, Pain/discomfort, self-healing | Tags: antibiotic resistance, antibiotics, bacteria, bacteriohage, health, Medicine Leave a commentRecently, I listened to a special episode featuring Lina Zeldovich on her book The Living Medicine, from This Podcast Will Kill You. I was totally inspired because it discussesd the healing power of bacteriophages, which apparently treat antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections successfully, reportedly without side effects. (Bacterial phages are viruses that selectively kill specific bacteria and have been used to treat multi-antibiotic-resistant conditions).

This emerging therapy is an aspect of individualized treatment. Zeldovich reports that it can not only be used to treat, but also to prevent the occurrence of bacterial illnesses. I rushed out to buy the book, The Living Medicine: How a lifesaving cure was nearly lost and why it will rescue us when antibiotics fail. Zeldovich is a great science storyteller and the book really captured me. I read it in two evenings and wanted to share this information, since a day may come when it could save your life.

This is a must-read for all of us, particularly for health professionals. It offers hope through a non-toxic strategy in the fight against antibiotic-resistant disease. The book provides a perspective on the challenges of bringing this effective healing strategy to acceptance and implementation when cultural biases and financial disincentives have stood in the way.;

Zeldovich, describes the development and history of bacterial phage medicine and why it has taken so many years to become accepted in the West. Only after several high-profile cases has this approach become of interest. A prime example is the 2016 treatment of Dr. Tom Patterson, a professor at UC San Diego, who contracted a life-threatening Acinetobacter baumannii infection while traveling (Garnett, 2019). The bacteria that caused his infection was resistant to every available antibiotic. After he slipped into a coma, his doctors feared the worst. As a last resort, his wife, Dr. Steffanie Strathdee, worked with scientists to identify phages that could target the infection. Within 48 hours of receiving intravenous phage therapy, Patterson woke up. He went on to make a full recovery, one of the first documented cases in the U.S. in which phages saved a patient’s life.

Pros and cons of antibiotics

Until antibiotics were discovered, bacterial infections were often fatal. This changed with the discovery of penicillin by Alexander Fleming in 1928. During World War II, antibiotics saved countless solders’ lives in the treatment of infected wounds, pneumonia, and blood poisoning. The antibiotic approach was quickly adopted in the United States, beginning in the early 1940’s, since penicillin could be mass-produced and thus was highly profitable for the pharmaceutical companies. Despite the initial success of the drug, bacteria quickly developed antibiotic resistance to penicillin due to the ability of bacteria to produce β-lactamase, an enzyme capable of breaking down the drug.

Antibiotics were and are extraordinary drugs. When a patient is becoming sicker and sicker as a bacterial infection spreads, the infection can be stopped in its tracks with an effective antibiotic. Before the era of antibiotic resistance, patients recovered as if by magic, simple by giving an antibiotic orally or intravenously,

I still remember when our son developed pneumonia at the age of 12, initially with coughing, a high fever, chest pain, and a great deal of congestion. But as the infection progressed, he began to have difficulty breathing and his energy was fading. We were initially hesitant to give the prescribed antibiotic because we hoped his immune system would be able to fight the infection. My hesitancy was based upon the fact that antibiotics do not selectively kill the bacteria causing the illness, but also destroy beneficial bacteria that are part of the human biome.

Millions of women who have taken an antibiotic for an infection subsequently experience chronic vaginal yeast infections. This occurs because antibiotics such as tetracyclines, which are used to treat UTIs, intestinal tract infections, eye infections, sexually transmitted infections, acne, and gum disease, also kill the healthy bacteria of the human biome in the vagina. Since nature abhors a vacuum, yeast then overgrow where healthy bacteria used to predominate, thus allowing a vaginal infection (candidiasis) to occur (Spinillo et al., 1999)

In the case of my son, as it became clear that he was getting weaker and his immune system was not successfully clearing the infection, we followed his doctor’s advice and gave him the antibiotic. Magically, within two days he was better, and we continued with the course of antibiotics to clear his body of all the bacteria that was causing the pneumonia. Treatment is always a decision that involves balancing risk and benefit, getting sicker or getting well, given the possible negative side effects of the treatment. At the same time, it was possible that the antibiotic would not work since there was no time to run a lab test for that specific bacteria. If it had not worked, he would have needed another, different antibiotic, and if that had failed, a third drug.

Today, antibiotic resistance has grown into a worldwide crisis. The World Health Organization estimates that antimicrobial resistance directly caused 1.27 million deaths and contributed to another 5 million deaths globally in 2019. In the United States alone, the CDC reports over 2.8 million antibiotic-resistant infections occur every year, leading to at least 35,000 deaths and more than 3 million cases of infection by Clostridioides difficile (C. diff) occur (CDC, 2019).

Potentially fatal diseases that have become antibiotic resistant include Staphylococcus aureus (such as methicillin-resistant Staph aureus or MRSA) and Streptococcus pneumoniae (strep), as well as Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Escherichia coli, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. These six pathogens alone were responsible for nearly 1 million deaths in 2019. Other dangerous resistant infections include multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB), extensively drug-resistant typhoid fever, and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), sometimes described as “nightmare bacteria” (Murray, et al., 2022).

Bacterial resistance develops because bacteria, like all living organisms, evolve. Antibiotics, which are typically chemicals produced by molds or other organisms, work by killing or interfering with the life cycle of specific types of bacteria. However, antibiotics are often a blunt instrument: they resemble a form of what has been referred to as carpet bombing in warfare, in which the enemy is destroyed, but the whole neighborhood is also destroyed. While antibiotics may eliminate the bacteria causing the infection, they can also damage or destroy many beneficial bacteria in the gut, on the skin, and other areas of the body.

One in five medication-related visits to the emergency room are from reactions to antibiotics (CDC, 2025). This collateral damage can disrupt the gut microbiome, weaken immunity, and create opportunities for other harmful microbes to flourish. In addition, frequent antibiotic use could possibly contribute to obesity, as evidenced by the fact that low dosages of antibiotics are often given to farm animals, not only to prevent disease, but to increase their weight. Antibiotics appear to alter the gut microbiome to make it more efficient at extracting nutrients and energy from feed (Cox, 2016).

Antibiotics have been one of the major focuses of pharmaceutical drug development; however, they can cause serious side effects and tend to become less effective over time as the bacteria develop antibiotic resistance. Many bacteria can develop antibiotic resistance in less than a 6 month time period (Poku et al., 2023). Once bacteria develop antibiotic resistance to one drug, a new antibiotic drug needs to be discovered, developed, and produced. Even the newer and stronger antibiotics rapidly loose their efficacy as the bacteria develop resistance to it. In the long term, it is a loosing battle, and a totally new approach is needed.

Bacteriophage therapy

One new approach worth closer consideration is bacteriophage therapy. In nature, bacteria and viruses have been locked in a constant evolutionary battle for billions of years. Bacteria are vulnerable to specific viruses, so a bacteriophage, or phage, refers to a virus that specifically infects and kills a particular strain of bacteria. As bacteria change to evade attack, phages evolve to counter them, maintaining an ongoing balance to some degree. The theory is that because phages are very specific and only act on one particular type of bacteria, that potentially makes them a uniquely precise form of medicine.

The challenge involves matching the phage to the pathogenic bacterium, and there are an astonishing number of different phages and bacteria. In two patients with the same symptoms or diagnosis, the causal bacteria could be a slightly different subspecies. When used clinically, bacteriophages work only against specific type of bacterium. This makes phage therapy a useful form of individualized medicine.

To be successful, the bacteria that causes the patient’s infection must first be identified. This is different from the way in which antibiotics are commonly used in primary care. When a patient develops symptoms, often an antibiotic is given before the bacteria has been identified, and if it does not work, another antibiotic is given.

In contrast, phage therapy depends on matching the specific disease-causing bacteria to a specific phage. Phage medicine requires a library of thousands of known phages as an essential prerequisite to treatment. Clinical care involves identifying the phage that can target and destroy that specific bacterium. Then the phage is cultured, purified, and administered in either a liquid preparation, capsule, ointment, intravenously or at a wound site depending on the type of infection.

Unlike antibiotics, which often damage beneficial microbes, phages only target the bacteria they evolved to destroy, leaving the rest of the human biome intact. Because viruses are capable of reproduction, once a phage reaches its bacterial host, it multiplies rapidly and produces hundreds of new phages that continue to attack the specific disease-causing bacteria as shown in Figure 1. According to reports from phage medicine, symptoms improve dramatically within 24 hours. The phages are self-limiting and their numbers naturally decline once the infection is cleared.

Figure 1. Electron micrograph of a phage attaching and injecting it viral genome into the cell and its life cycle

At present, phage therapy has already shown success against a variety of resistant infections, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Acinetobacter baumannii wound infections (a major problem in military medicine), multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae, and even certain cases of tuberculosis. Instead of being the last line of defense, in the future this may become the first line of defense.

The initial research and clinical use has been concentrated in Russia and Eastern Europe. The United States largely abandoned phage therapy after the discovery of antibiotics. Several factors contributed to this trend.

- Funding barriers. Funding agencies in the West have not seen phage therapy as a credible option. In many cases, the review committees that decided which grant applications to approve have tended to fund research that supported their own biases and their interests in antibiotic research. As a result, research money was rarely allocated to study or develop phage therapies. Generally, high- risk, novel research ideas are almost never funded by federal agencies except DARPA which is more open to new concepts when they offer a high potential of success.

- Economic realities discourage investment. Unlike antibiotics, which can be mass-produced as a single chemical and sold at high volume for profit, phage therapy requires maintaining large, evolving phage libraries and tailoring treatments to each patient. This individualized model offered little appeal to large pharmaceutical companies seeking standardized products with a high payout.

- Development is not scalable. A specific bacteriophage must be selected for each specific pathogenic bacteria, and a large phage collection must be maintained to identify the correct phage.

- Scientific and cultural bias. American researchers have tended to dismiss work coming out of Russia and Georgia, failing to recognize the rigor and effectiveness of decades of phage therapy practiced there. Limited scientific exchange was also a factor during the Cold War. A similar bias, for example, has influenced the adoption of psychological treatment strategies developed in Russia. In the U.S., the focus was more on using instrumental learning while neglecting the power of Pavlov’s classical condition.

These scientific prejudices, financial disincentives, and geopolitical divides have meant that phage therapy was almost totally absent in Western medicine although it continued in Eastern Europe, where it has saved countless lives. Phage therapy is currently becoming recognized and desperately needed because of the increase in multi-drug-resistant infections.

Phage treatment challenges

The greatest challenge with phage therapy is that it must be individualized to the pathogen. Each patient’s infection may require a different phage, because phages are exquisitely specific to the bacterium they target. A phage that destroys one strain of E. coli, for example, may have no effect on another subspecies of E. coli. While the same phage can sometimes be used for multiple patients with the same infection, in most cases treatment must be customized to the individual patient.

This requires maintaining vast phage libraries that researchers and clinicians must be able to screen rapidly in order to find the right match. The scale of this challenge is staggering, although AI technology may be part of the solution. Scientists estimate that there are 10³¹ (ten million trillion trillion) specific phages on Earth, making them the most abundant biological entities known. Only a tiny fraction of these have been studied, and only a relatively smaller number are currently catalogued for medical use.

Specialized research institutes, particularly in Georgia, Poland, and Russia (and now in the U.S. and Europe) have developed large collections of phages that can be tested against samples of specific bacterium. Building, maintaining, and updating these libraries is labor-intensive and requires constant monitoring, since both bacteria and phages evolve. Phage therapy does not lend itself easily to large-scale commercialization. Nevertheless, phage therapy represents one of the most promising approaches to resistant infections.

Summary

Unlike antibiotics, which disrupt the human microbiome and can cause significant side effects, phages are naturally occurring, highly targeted, and generally well tolerated. Because they attack only a specific bacterium, without disturbing beneficial microbes, phages have the potential to be used not only as a treatment but also for prevention, helping to control bacterial populations before they cause disease. Harnessing this form of living medicine could mark an evolutionary shift in modern healthcare, offering a sustainable, balanced way to prevent and treat infections. Read the outstanding book by Lina Zeldovich, The Living Medicine: How a lifesaving cure was nearly lost and why it will rescue us when antibiotics fail.

References

admin. (2025, August 28). Special Episode: Lina Zeldovich & The Living Medicine. This Podcast Will Kill You. Accessed September 1, 2025. https://thispodcastwillkillyou.com/2025/08/28/special-episode-lina-zeldovich-the-living-medicine/

CDC. (2019). Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2019. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/antimicrobial-resistance/media/pdfs/2019-ar-threats-report-508.pdf

CDC. (2025). Do antibiotics have side effects. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC Accessed September 5, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/media/pdfs/Do-Antibiotics-Have-Side-Effects-508.pdf

Cox, L.M. (2016). Antibiotics shape microbiota and weight gain across the animal kingdom, Animal Frontiers, 6(3), 8–14. https://doi.org/10.2527/af.2016-0028

Garnett, C. (2019). Personal quest resurrects phage therapy in infection fight. NIH Record, LXXI(6). https://nihrecord.nih.gov/2019/03/22/personal-quest-resurrects-phage-therapy-infection-fight

Murray, C. J. L. et al. (2022). Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. The Lancet, 399(103250, 629 – 655. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02724-0

Poku, E., Cooper, K., Cantrell, A., Harnan, S., Sin, M.A., Zanuzdana, A., & Hoffmann, A. (2023). Systematic review of time lag between antibiotic use and rise of resistant pathogens among hospitalized adults in Europe. JAC Antimicrob Resist, 5(1), dlad001. https://doi.org/10.1093/jacamr/dlad001

Spinillo, A., Capuzzo, E., Acciano, S., De Santolo, A., & Zara, F. (1999). Effect of antibiotic use on the prevalence of symptomatic vulvovaginal candidiasis. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 180(1 Pt 1),14-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70141-9

Zeldovich, L. (2024). The Living Medicine: How a lifesaving cure was nearly lost and why it will rescue us when antibiotics fail. New York: St. Martin’s Press. https://www.amazon.com/Living-Medicine-Lifesaving-Lost_and-Antibiotics/dp/1250283388

*Created in part from the information in the book, The Living Medicine-How a lifesaving cure was nearly lost-and why it will rescue Us When Antibiotics Fail, by Linda Zeldovich and with the editorial help of ChatGPT5.

Exploring the pain-brain-breathing connection

Posted: August 30, 2025 Filed under: attention, behavior, Breathing/respiration, cognitive behavior therapy, education, emotions, healing, meditation, Pain/discomfort, placebo, self-healing, Uncategorized | Tags: deliberate harm Leave a commentIf you’re curious about how the mind and body interplay in shaping pain—or looking for real, actionable techniques grounded in research listen to this episode of the Heart Rate Variability Podcast, Matt Bennett interviews Dr. Erik Peper about his article and blogpost Pain – There Is Hope. The conversation takes listeners beyond the common perception of pain as merely a physical response. It is a balanced mix of scientific depth and real-life applications, especially valuable for anyone interested in self-healing, holistic health, or understanding mind-body medicine. Moreover, it explains how pain is shaped by posture, breathing, mindset, and emotional context. Finally, it provides practical strategies to shift the pain experience, offering an uplifting and science-backed blend of understanding and hope.

If you find this helpful, let me know! And feel free to share it with friends and post it on your social channels so more people can benefit.

Blogs that complement this interview

If you want to explore further, check out the companion blog posts I hve created to expand on the themes from this discussion. These blogs highlight practical strategies, scientific insights, and everyday applications.

Healing from the Inside Out: How Your Mind–Body Shapes Pain

Posted: June 9, 2025 Filed under: attention, behavior, Breathing/respiration, CBT, emotions, healing, health, mindfulness, Pain/discomfort, placebo, self-healing, Uncategorized | Tags: health, meditation, mental-health, mindfulness, Sufism, yoga 2 CommentsAdapted from Peper, E., Booiman, A. C., & Harvey, R. (2025). Pain-There is Hope. Biofeedback, 53(1), 1-9. http://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-53.01.16

Pain is more than a physical sensation—it’s shaped by our breath, thoughts, emotions, and beliefs. A striking example: a four-year-old received a vaccination with no pain, revealing the disconnect between what science knows about pain relief and what’s practiced.

The article highlights five key ways to reduce pain:

- Exhale during the painful moment – This activates the parasympathetic nervous system, calming the body. A yogi famously demonstrated this by pushing skewers through his tongue without bleeding or feeling pain.

- Create a sense of safety – Feeling secure can lessen pain and speed healing. Sufi mystics have shown this by pushing knives through their chest muscles without long-term damage, often healing rapidly.

- Distract the mind – Shifting focus can ease discomfort.

- Reduce anticipation – Fear of pain often amplifies it.

- Explore the personal meaning of pain – Understanding what pain symbolizes can shift how we experience it.

The blog also explores how the body regulates pain through mechanisms which influence inflammation and pain signals. In the end, hope, trust, and acceptance, along with mindful breathing, healing imagery, and meaningful engagement, emerge as powerful tools not just to reduce pain—but to promote true healing.

Listen to the AI generated podcast created from this article by Google NotebookLM

I took my four-year-old daughter to the pediatrician for a vaccination. As the nurse prepared to administer the shot in her upper arm. I instructed my daughter to exhale while breathing, understanding that this technique could influence her perception of pain. Despite my efforts, my daughter did not follow my instructions. At that point, the nurse interjected and said, “Please sit in front of your daughter.” Then turned to my daughter and said, “Do you see your father’s curly hair? Do you think you could blow the curls to move them back and forth?” My daughter thought this playful game was fun! As she blew at my hair, the curls moved back and forth while the nurse administered the injection. My daughter was unaware that she had received the shot and felt no pain.

My experience as a father and as a biofeedback practitioner was enlightening–it demonstrated the difference between theoretical knowledge of breathing techniques associated with pain perception and practical applications of clinical skills used by a pediatric nurse practitioner while administering an injection with children. An obvious question raised is: What processes are involved in the perception of pain?

There are many factors influencing pain perception, such as physical/physiological, behavioral and psychological/emotional factors related to the injection as described by St Clair-Jones et al., (2020). Physical and physiological considerations include device type such as needle gauge size as well as formulation volume and ingredients (e.g., adjuvants, pH, buffers), fluid viscosity, temperature, as well as possible sensitivity to coincidental exposures associated with an injection (e.g., sensitivity to latex exam gloves or some other irritant in the injection room).

There are overlapping physical and behavioral-related moderators that include weight and body fat composition, proclivity towards movements (e.g., activity level or ‘squirminess’), as well as co-morbid factors such as whether the person has body sensitization due to rheumatoid arthritis and/or fibromyalgia, for example. Other behavioral factors include a clinician selecting the injection site, along with the angle, speed or duration of injection. Psychological influences center around patient expectations including injection-anxiety or needle phobia, pain catastrophizing, as well as any nocebo effects such as white-coat hypertension.

Although the physical, behavioral and psychological categories allow for considering many physical and physiological factors (e.g., product-related factors), behavioral factors (e.g., injection-related behaviors) and psychological factors (e.g., person-related psychological attitudes, beliefs, cognitions and emotions), this article focuses on a figurative recipe for success associated with benefits of simple breathing to reduce pain perceptions.

Of the many categories of consideration related to pain perceptions, following are five key ‘recipe ingredients’ that contributed to a relatively painless experience:

- Exhaling During Painful Stimuli: Exhaling during a painful stimulus can activate parts of the parasympathetic nervous system leading to promotion of self-healing.

- Creating a Sense of Safety: Ensuring that the child feels safe and secure is crucial in managing pain. My lack of worry and concern and the nurse’s gentle and engaging approach created a comforting environment for my daughter.

- Using Distraction: Distraction techniques, such as focusing on the movement of the curls of the hair served to redirect my daughter’s attention away from the anticipated pain.

- Reducing Anticipation of Pain: My daughter’s previous visits were always enjoyable and as a parent, I was not anxious and was looking forward to the pediatrician visit and their helpful advice.

- Understanding the Personal Meaning of Pain: The approach taken by the nurse allowed the injection to be perceived as a non-event, thereby minimizing the psychological impact of the pain.

Exhaling During Painful Stimuli

Exhaling during painful stimuli facilitates a reduction in discomfort through several physiological mechanisms. During exhalation the parasympathetic nervous system is activated, which slows the heart rate and promotes relaxation, regeneration, reduces anxiety, and may counteract the effects of pain (Magnon et al., 2021). Breathing moderation of discomfort is observable through heart rate variability associated with slow, resonant breathing patterns, where heart rate increases with inhalation and decreases with exhalation (Lehrer & Gevirtz, 2014; Steffen et al., 2017). Physiological studies show that slow, resonant breathing at approximately six breaths per minute for adults, and a little faster for young children, causes the heart rate to increase during inhalation and decrease during exhalation, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Changes in heart rate as modulated by slower breathing at about six breaths per minute

One can experience how breathing affects discomfort when taking a cold shower under two conditions: As the cold water hits your skin: (1) gasping and holding your breath versus (2) exhaling slowly as the cold water hits you. Most people will report that slowly exhaling feels less uncomfortable, though they may still prefer a warm shower.

An Exercise for Use During Medical Procedures: Paring the procedure with inhalation and exhalation

A simple breathing technique can be used to reduce the experience of pain during a procedure or treatment, or during uncomfortable movement post-injury or post-surgery. Physiologically, inhalation tends to increase heart rate and sympathetic activation while exhalation reduces heart rate and increases parasympathetic activity. Often inhalation increases tension in the body, while during exhalation, one tends to relax and let go. The goal is to have the patient practice longer and slower breathing so that a procedure that might be uncomfortable is initiated during the exhalation phase. Applications of long, slow breathing techniques include having blood drawn, insertion of acupuncture needles in tender points, or movement that causes discomfort or pain. Slowly breathing is helpful in reducing many kinds of discomfort and pain perceptions (Joseph et al., 2022; Jafari et al., 2020).

Implementing the technique of exhaling during painful experiences can be deceptively simple yet challenging. When initially practicing this technique, the participants often try too hard by quickly inhaling and exhaling as the pain stimulus occurs. The effective technique involves allowing the abdomen to expand while inhaling, then allowing exhaled air to flow out while simultaneously relaxing the body and smiling slightly, and initiating the painful procedure only after about 25 percent of the air is exhaled.

Some physiological mechanisms that explain how slow breathing influences on pain perceptions have focused on baroreceptors that are mechanically sensitive to pressure and breathing dynamics. According to Suarez-Roca et al. (2021, p 29): “Several physiological factors moderate the magnitude and the direction of baroreceptor modulation of pain perception, including: (a) resting systolic and diastolic AP, (b) pain modality and dimension, (c) type of activated vagal afferent, and (d) the presence of a chronic pain condition It supports the parasympathetic activity that exert an anti-inflammatory influence, whereas the sympathetic activity is mostly pro-inflammatory. Although there are complex physiological interactions between cardiorespiratory systems, arterial pressure and baroreceptor sensitivity that influence pain perceptions, this report focuses on simpler reminders, such as creating a sense of safety for people as a result of better breathing techniques.

Creating a Sense of Safety

My young daughter did not know what to expect and totally trusted me and I was relaxed because the purpose was to enhance my daughter’s future health by giving her a vaccination to prevent being sick at a future time. Often, a parent’s anxiety is contagious to the child since expectations and emotional states influence the experience of medical procedures and pain (Sullivan et al., 2021). For my daughter, the nurse’s calm and confident demeanor contributed to a safe and reassuring environment. As a result, she was more engaged in a playful distraction, blowing at my hair, rather than focusing on the impending shot. This observation underscores an important psychological principle: when individuals do not anticipate pain and feel safe, they are more likely to experience surprise rather than distress. Conversely, anticipation of pain can amplify the perception of discomfort.

For instance, many people have experienced heightened anxiety at the dentist, where they may feel the pain of the needle before it is inserted. Anticipation evocates a past memory of pain that triggers a defensive reaction, increasing sympathetic arousal and sharpening awareness of potential danger. By providing the experience of feeling of safety, parents, caretakers, and medical professionals can play a crucial role in reducing the perceived pain of medical interventions.

Using Distraction

It is inherently difficult to attend to two tasks simultaneously; thus, focusing one’s attention on one task often diminishes awareness of pain and other stimuli (Rischer et al., 2020). For instance, when the nurse asked my daughter to see if she could blow hard enough to make the curls move back and forth, this task captured her attention in a fun and multisensory way. She was engaged visually by the movement of the curls, audibly by the sound of the rushing air, physically by the act of exhalation, and cognitively by following the instructions. Additionally, her success in moving the curls reinforced the activity as a positive and enjoyable experience.

In contrast, it is challenging to allow oneself to be distracted when anticipating discomfort, as numerous cues can continuously refocus attention on the procedure that may induce pain. This experience is akin to attempting to tickle oneself, which typically fails to elicit laughter due to the predictability and lack of external stimulation. Most of us have experienced how challenging it is to be self-directive and not focus on the sensations during dental procedures as discussed in the overview of music therapy for use in dentistry by Bradt and Teague (2018). The challenges are illustrated by my own experience during a dental cleaning

During a dental cleaning, I often attempt to distract myself by mentally visualizing the sensation of breathing down my legs while repeating an internal mantra or evoking joyful memories. Despite these efforts, I frequently find myself attending to the sound of the ultrasonic probe and the sensations in my mouth. To manage this distraction more effectively, I have found that external interventions such as listening to music or an engaging audio story through earphones is more beneficial.

From this perspective, we wished that the dentist could implement an external intervention by collaborating with a massage therapist to provide a simultaneous foot massage during the teeth cleaning. This dual stimulation would offer enough competing sensations to divert attention from the dental procedure to the comfort of the foot massage.

Reducing Anticipation of Pain

A crucial factor in the experience of pain is the anticipation and expectation of discomfort, which is often shaped by previous experiences (Henderson et al., 2020; Reicherts et al., 2017). When encountering a novel experience, we might interpret the sensations as novel rather than painful. Similar phenomena can be observed in young children when they fall or get hurt on the playground. They may initially react with surprise or shock and may look for their caretaker. Depending the reaction of their caregiver, they may begin to cry or they might cry briefly, stop and resume playing.

Conversely, the anticipation of pain can heighten sensitivity to any stimuli, causing them to be automatically perceived as painful. Anticipatory responses function as a form of mental rehearsal, where the body responds in a manner similar to the actual experience of pain. For example, Peper, et al. (2015) showed that when a pianist imagined playing the piano, her forearm flexor and extensor muscles exhibited slight contractions, even though there was no observable movement in her arm and the pianist was unaware of these contractions (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. The covert SEMG increase in forearm SEMG as the participant imagined playing the piano (reproduced by permission from Peper et al., 2015).

These kind of muscle reactions are also visible in sportsmen. For example, while mentally racing a lap on a motorbike, the arm muscles act like as if the person is racing in the dust of the circuit (Booiman 2018). The blood flow (BVP) and blood vessels are reacting even quicker than muscle tension on thoughts and expected (negative) experiences.

These findings underscore how anticipatory responses can mirror actual physical experiences, providing insights into how anticipation and expectancy can modify pain perception (Henderson et al., 2020). Understanding these mechanisms allows for the development of interventions aimed at managing pain through the modification of expectations and the introduction of distraction techniques.

The Personal Meaning of Pain (adapted from Peper, 2015)

The personal meaning of pain is a complex construct that varies significantly based on context and individual perception. For example, consider the case of a heart attack. Initially, the person might experience chest pain and dismiss it, which can be attributed to societal norms where people are conditioned to ignore pain. However, once the pain is assumed or diagnosed to be a heart attack, the same pain may become terrifying as it may signify the potential for life-threatening consequences. Following bypass surgery, the pain might actually be worse, but it is now reframed positively as a sign of the surgery’s success and a symbol of hope for survival. Thus, the meaning of pain evolves from one of fear to one of reassurance and recovery.

This notion that pain is defined by the context in which it occurs is crucial (Carlino et al., 2014). For instance, childbirth, despite being intensely painful, is understood within the context of a natural and temporary process that leads to the birth of a child. This perception is often reinforced nonverbally by a supportive midwife or doula. It may be helpful if the midwife or doula has given birth herself. Without words she communicates, “This is an experience that you can transcend, just as I did.” Psychologically/emotionally, the pain serves a higher purpose, to deliver a child into the world, which may also make the pain more bearable. There is a reward, namely the child. In addition, women who have had training and information about the process of childbirth have a significant faster delivery (about 2 hours faster).

Piercing the body without reporting pain or bleeding

To further illustrate this concept, Peper et al. (2006) and Kakigi et al. (2005) physiologically monitored the experiences of a Japanese Yogi Master, Mitsumasa Kawakami,who performed voluntary body piercing with unsterilized skewers, as depicted in Figure 3 (Peper, 2015).

Figure 3. Demonstration Japanese Yogi Master, Mitsumasa Kawakami, voluntary piercing the tongue and neck with unsterilized skewers while experiencing no pain, bleeding or infection (reproduced by permission from Peper et al., 2006).

See the video recording of tongue piercing study recorded November 11, 2000, at the annual Biofeedback Society Meeting of California, Monterey, CA, https://youtu.be/f7hafkUuoU4 (Peper & Gunkelman, 2007).

Despite the visual discomfort of seeing this procedure, physiological data from pulse, EEG and breathing patterns revealed that the yogi did not experience pain. During the piercing, his heart rate was elevated, his electrodermal activity was low and unresponsive, and his EEG showed predominant alpha waves, indicating a state of focused meditation rather than pain. This study suggests that conscious self-regulation, rather than dissociation, can be employed to control attention and responsiveness to painful stimuli and possibly benefit individuals with chronic pain (Peper et al., 2005).

A similar phenomenon was observed among a spiritual gathering of Kasnazani Sufi initiates in Amman, Jordan and physiologically monitored during demonstrations as part of a scientific meeting. The Kasnazani order is a branch of Sufism that has gained widespread popularity in Iraq and Iran, particularly among the Kurdish population. What sets the Kasnazani order apart is its inclusive approach—it welcomes both Sunni and Shia Muslims, making no distinction between them. During spiritual gatherings, some followers perform acts that might seem extreme to outsiders: piercing their bodies. These acts are seen as expressions of deep spiritual devotion and are performed in a state believed to be beyond normal physical sensation. With the permission of their Sheikh Mohammed Abdul Kareem Kasnazani, they pierced their face, neck arms, or chest and reported no pain or bleeding and heal quickly, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Voluntary piercing and with unsterilized skewers by Sufi initiates and subsequent tissue healing after 14 hours.

See the video recording of the actual piercing study organized by Erik Peper and Howard Hall with Thomas Collura recording the QEEG at the 2013 Annual Scientific Meeting of the Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, Portland, OR (Peper & Hall, 2013; Collura et al., 2014), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=56nLZyG87oc

What Factors Decrease the Experience of Pain and Promote Rapid Healing with the Absence of Bleeding?

In the case of the Kasnazani Sufis, they framed their experience as a normal, spiritual phenomenon that occurs in a setting of religious faith and total trust in their spiritual leader (Hall, 2011). The Sufis reported that they had permission and support from their master, Sheikh Mohammed Abdul Kareem Kasnazani. Thus, they felt totally safe and protected—they had no doubt they could experience the piercing with reasonable composure and that their bodies would totally heal. Even if pain occurred, it was not to be feared but part of the process. The experience may be modulated by the psychological context of the group, the drumming, and the chanting. The phenomenon was not simply a matter of belief; they knew that healing would occur because they had seen it many times in the past. The knowledge that healing would occur rapidly was transmitted as a felt sense in the group that this is possible and following the expected normal pattern.

The most impressive finding was that the physiology markers (heart rate, skin conductance, and breathing) were normal and there was no notable change (Booiman et al., 2015; Peper & Hall, 2013) and the QEEG indicated the inhibition of pain (Collura et al., 2014).

Clinical implications

These observations underscore that the context of pain—whether through personal meaning, spiritual belief, or communal support—can significantly alter its perception and management. This concept is also reflected in clinical settings, where a lack of diagnosis or acknowledgment of pain can exacerbate suffering. An isolated individual, alone at night with the physical sensation of pain, may find the pain tremendously stressful, which tends to intensify the experience. In this situation, there are concerns about the future: “It may get worse, it will not go away, I’m going to die from this, maybe I’ll die alone,” and the worry continues.

If one can let go of these thoughts, breathe through the pain, relax the muscles and experience a feeling of hope, the pain is often reduced. On the other hand, focusing on the pain may intensify it. On the other hand, the meaning of pain implies survival or hope as sometimes is observed in injured soldiers. In context of the hospital setting: “I have survived and I am safe.”

What are the implications of these experiences in clinical settings in which the patient is in constant pain and yet has not received an accurate diagnosis? Or, in cases in which the patient has a diagnosis, such as fibromyalgia, but treatment has not reduced the pain significantly? Experiencing pain or illness that goes undiagnosed, and/or that is not acknowledged, may increase the level of stress and tension, which can contribute to more pain and discomfort. As long as we are resentful/angry/resigned to the pain or especially to the event that we believe has caused the pain, the pain often increases. Another way to phrase this is that chronic sympathetic arousal increases the sensitivity to pain and reduces healing potential (Kyle & McNeil, 2014).

Acknowledgement means having an accurate diagnosis, validating that the pain experience is legitimate and that it is not psychosomatic (imagined), because that simply makes the experience of pain worse. Once the patient has a more accurate diagnosis, treatment may be possible.

When one has constant, chronic, or unrelenting pain, this evokes hopelessness and the patient is more likely to get depressed (Sheng et al., 2017; Meda et al., 2022). The question is, What can be done? The first step for the patients is to acknowledge to themselves that it does not mean that the situation is unsolvable. It is important to focus on other options for diagnosis and treatment and take one’s own lead in the healing/recovery process. We have observed that a creative activity that uses the signals of pain to evoke images and thoughts to promote healing may reduce pain (Peper et al., 2022). Pain awareness may be reduced when the person initiates actions that contribute to improving the well-being of others.

Overall, pain appears to decrease when a person accepts without resignation what has happened or is happening. A useful practice that may change the pain experience is to do an appreciation practice. Namely, appreciate what that part of the body has done for you and how so often in the past you may have abused it. For example, if you experience hip pain, each time you are aware of the pain, thank the hip for all the work it has done for you in the past and how often you may have neglected it. Keep thanking it for how it has supported you.

Pain often increases when the person is resentful or wished that what has happened had not happened (Burns et al., 2011). If the person can accept where they are and focus on the new opportunities and new goals can achieve, pain may still occur; however, the quality is different. Focus on what you can do and not on what you cannot do. See Janine Shepherd’s 2012 empowering TED talk, “A broken body isn’t a broken person.”

Conclusion

The primary lessons from studying the yogi and the Sufis are the concepts that a sense of safety, acceptance, and purpose can transform the experience of pain. Expressing confidence in a patient’s recovery prospects places the focus on their ability to recover. Incorporating these elements into clinical care may offer new avenues for addressing chronic pain and improving patient outcomes (Booiman & Peper, 2021).

We propose the first step is to create an atmosphere of hope, trust and safety and to emphasize the improvements made (even small ones). Then master effortless breathing to increase slow diaphragmatic breathing and teach clients somato-cognitive techniques to refocus their attention during painful stimuli (mindfulness) (Pelletier & Peper, 1977; Peper et al., 2022). Using the slow breathing as the overlearned response would facilitate the recovery and regeneration following the painful situation. To develop mastery and be able to apply it under stressful situations requires training and over-learning. Yoga masters overlearned these skills with many years of meditation. With mastery, patients may learn to abort the escalating cycle of pain, worry, exhaustion, more pain, and hopelessness by shifting their attention and psychophysiological responses. In clinical practice, strategies such as hypnotic induction, multisensory distraction, self-healing visualizations, and mindfulness techniques can be employed to manage pain. A foundational principle is that healing is promoted when the participant feels safe and accepted, experiences suffering without blame, and looks forward to life with meaning and purpose.

Acknowledgement

We thank Mitsumasa Kawakami, Sheikh Mohammed Abdul Kareem Kasnazani, and Safaa Saleh for their generous participation in this research and I thank our research collegues Thomas Collura, Howard Hall and Jay Gunkelman for their support and collaboration.

References

Booiman, A.C. (2018) Posture corrections and muscle control can prevent arm pump during motocross, a case study. Beweegreden, 14(3), 24–27. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/382853342

Booiman, A. C. & Peper, E. (2021) De pijnbeleving van Kaznazanisoefi’s, wat kan de fysiotherapeut daarvan leren? Physios Vol 13 (3) pp. 32–35. https://www.physios.nl/tijdschrift/editie/artikel/t/de-pijnbeleving-van-kaznazani-soefi-s-wat-kan-de-fysiotherapeut-daarvan-leren

Booiman, A., Peper, E., Saleh, S., Collura, T., & Hall, H. (2015). Soefi piercing een andere kijk op pijnervaring en pijnmanagement. https://biofeedbackhealth.files.wordpress.com/2011/01/soefi-en-pijn-management-08-12-20131.pdf

Bradt. J. & Teague, A. (2018). Music interventions for dental anxiety. Oral Diseases, 24(3), 300–306. https://doi.org/10.1111/odi.12615

Burns, J.W., Quartana, P., & Bruehl, S. (2011). Anger suppression and subsequent pain behaviors among chronic low back pain patients: moderating effects of anger regulation style. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 42(1), 42–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-011-9270-4

Carlino, E., Frisaldi, E., & Benedetti, F. (2014). Pain and the context. Nature Reviews Rheumatology, 10(6), 348–355. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2014.17

Collura, T. F., Hall, H., & Peper, E. (2014). A Sufi self-piercing analyzed with EEG and sLORETA. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 39(3–4), 293–293. https://brainmaster.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/AAPB_BOS05_2015_Pain_Controll.pdf

Hall, H. (2011). Sufism and healing. In Neuroscience, Consciousness and Spirituality (pp. 263–278). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-2079-4_16

Henderson, L. A., Di Pietro, F., Youseff, A. M. , Lee, S., Tam, S., Akhter, R., Mills, E.P., Murray, G. M., Peck, C.C., & Macey, P.M. (2020). Effect of expectation on pain processing: A psychophysics and functional MRI analysis. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2020.00006

Jafari, H., Gholamrezaei, A., Franssen, M., Van Oudenhove, L., Aziz, Q., Van den Bergh, O., Vlaeyen, J. W. S., & Van Diest, I. (2020). The Journal of Pain, 21(9–10), 1018−1030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2019.12.010

Joseph, A. E., Moman, R. N., Barman, R. A., Kleppel, D. J., Eberhart, N. D., Gerberi, D. J., Murad, M. H., & Hooten, W. M. (2022). Effects of slow deep breathing on acute clinical pain in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Evidence-Based Integrative Medicine, 27, 2515690X221078006. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515690X221078006

Kakigi, R. Nakata, H., Inui, K., Hiroe,N. Nagata, O., Honda, M., Tanaka, S., Sadato, N. & Kawakami, M. (2005). Intracerebral pain processing in a Yoga Master who claims not to feel pain during meditation. European Journal of Pain. 9(5), 581–581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.12.006

Kyle, B. N., & McNeil, D. W. (2014). Autonomic arousal and experimentally induced pain: a critical review of the literature. Pain Research Management, 19(3),159–167. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/536859

Lehrer, P. & Gevirtz R. (2014). Heart rate variability biofeedback: How and why does it work? Frontiers in Psychology, 5,756. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00756

Magnon, V., Dutheil, F. & Vallet, G. T. (2021). Benefits from one session of deep and slow breathing on vagal tone and anxiety in young and older adults. Scientific Reports, 11, 19267. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-98736-9

Meda, R. T., Nuguru, S .P., Rachakonda, S., Sripathi, S., Khan, M. I., & Patel, N. (2022). Chronic paininduced depression: A review of prevalence and management. Cureus,14(8):e28416. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.28416

Pelletier, K. R. and Peper, E. (1977). Developing a biofeedback model: Alpha EEG as a means for pain control. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 24(4), 361–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207147708415991

Peper, E. (2015). Pain as a contextual experience. Townsend Letter—The Examiner of Alternative Medicine, 388, 63–66. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Erik-Peper/publication/284721706_Pain_as_a_contextual_experience/links/5657483908ae1ef9297bab71/Pain-as-a-contextual-experience.pdf

Peper, E., Cosby, J., & Almendras, M. (2022). Healing chronic back pain. NeuroRegulation, 9(3), 164–172. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.9.3.164

Peper, E. & Gunkelman, J. (2007). Tongue piercing by a yogi: QEEG observations and implications for pain control and health. Presented at the 2007 meeting of the Biofeedback Society of California. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/382394304_Tongue_Piercing_by_a_Yogi_QEEG_Observations_and_Implications_for_Pain_Control_and_Health

Peper, E. & Hall, H. (2013). What is possible: A discussion, physiological recording and actual demonstration in voluntary pain control by Kasnazani Sufis. Presented at the 44st Annual Meeting of the Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. Portland, OR.

Peper, E., Kawakami, M., Sata, M. & Wilson, V.S. (2005). The physiological correlates of body piercing by a yoga master: Control of pain and bleeding. Subtle Energies & Energy Medicine Journal, 14(3), 223–237. https://biofeedbackhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/366-663-1-sm.pdf

Peper, E., Nemoto, S., Lin, I-M., & Harvey, R. (2015). Seeing is believing: Biofeedback a tool to enhance motivation for cognitive therapy. Biofeedback, 43(4), 168–172. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-43.4.03

Peper, E., Wilson, V.E., Gunkelman, J., Kawakami, M. Sata, M., Barton, W. & Johnston, J. (2006). Tongue piercing by a yogi: QEEG observations. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. 34(4), 331–338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-006-9025-3

Reicherts, P., Wiemer, J., Gerdes, A.B.M., Schulz, S.M., Pauli, P., & Wieser, M.J. (2017). Anxious anticipation and pain: The influence of instructed vs conditioned threat on pain. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 12(4), 544–554. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsw181

Rischer, K. M., González-Roldán, A. M., Montoya, P., Gigl, S., Anton, F., & van der Meulen, M. (2020). Distraction from pain: The role of selective attention and pain catastrophizing. European Journal of Pain, 24(10),1880–1891. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.1634

Sheng, J., Liu, S., Wang, Y., Cui, R., & Zhang, X. (2017). The link between depression and chronic pain: Neural mechanisms in the brain. Neural Plasticity, 9724371. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/9724371

Shepherd, J. (2012). A broken body isn’t a broken person. TEDxKC. Accessed July 19, 2024. https://www.ted.com/talks/janine_shepherd_a_broken_body_isn_t_a_broken_person?subtitle=en

Steffen, P.R., Austin, T., DeBarros, A., & Brown, T. (2017). The impact of resonance frequency breathing on measures of heart rate variability, blood pressure, and mood. Frontiers in Public Health, 5, 222. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00222

St Clair-Jones, A., Prignano, F., Goncalves, J., Paul, M., & Sewerin, P. (2020). Understanding and minimising injection-site pain following subcutaneous administration of biologics: A narrative review. Rheumatology and therapy, 7, 741–757. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13034609

Suarez-Roca, H., Mamoun, N., Sigurdson, M. I., & Maixner, W. (2021). Baroreceptor modulation of the cardiovascular system, pain, consciousness, and cognition. Comprehensive Physiology, 11(2), 1373. https://doi.org/10.1002/cphy.c190038

Sullivan, V., Sullivan, D. H. & Weatherspoon, D. (2021). Parental and child anxiety perioperatively: Relationship, repercussions, and recommendations. Journal of PeriAnesthesia Nursing, 36(3), 305–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jopan.2020.08.015

Wilber, K. (1997). An integral theory of consciousness. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 4(1), 71–92. https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/imp/jcs/1997/00000004/00000001/748

The Power of No

Posted: March 6, 2025 Filed under: behavior, Breathing/respiration, CBT, cognitive behavior therapy, emotions, healing, health, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: assertiveness, emotional awareness, HIV, immune resilence, surviaval 1 CommentBrenda Stockdale, PhD and Erik Peper, PhD

Adapted from: Stockdale, B. & Peper, E. (2025). How the Power of No Supports Health and Healing. Townsend Letter-Innovative Health Perspectives, March15, 2025 https://townsendletter.com/the-power-of-no/

I felt exhausted and just wanted to withdraw to recharge. Just then, my partner asked me to go to the store to get some olive oil. I paused, took a deep breath, and checked in with myself. I realized that I needed to take care of myself. After a few seconds, I responded, “No, I cannot do it at this time.”

It was challenging to say this because, in the past, I would have automatically said “yes” to avoid disappointing my partner. However, by saying “yes” and ignoring my own needs, I would have become even more exhausted, hindering my recovery. I felt proud that I had said “no.” By listening to myself, I took charge and prioritized my own healing.

For many people, saying “no” feels unkind, and we want to be kind while avoiding burdening others. Nevertheless, how you answer this question may have implications for your health! Consider the following question and rate it on a scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always):

How often do you do favors for people when you really don’t want to? Namely, things you really don’t want to do but do anyway because someone asks you to and you don’t want to or can’t say “No.“

In analysis of numerous studies, Prof. George Solomon and Dr. Lydia Temoshok reported that a low score on this question (indicating the ability to say No) was the best predictor of related outcomes across studies, such as survivorship with AIDS as well as more favorable HIV immune measures (Solomon, et al, 1987). This aligns with research suggesting that excessive compliance, self-sacrifice, and conflict avoidance (i.e., people-pleasing) in individuals with cancer and chronic illness may weaken, rather than strengthen, their immune systems (Temoshok, & Dreher, 1992).

Unconsciously avoiding or suppressing distressing thoughts, emotions, or memories instead of dealing with them––a process known as repressive coping–– may even contribute to an increased risk of cancer and cardiovascular disease (Mund & Mitte, 2012). Avoiding emotional cues or dismissing feelings may seem self-protective but can lead to reflexive or automatic behavior such as saying “yes” when individuals would rather say “no.” Although the conflict may not be consciously recognized, it can manifest physiologically (Mund & Mitte, 2012). Paying attention to states of tension, or symptoms such as headache or loss of appetite can serve as a doorway to exploring unacknowledged feelings.

Automatically saying “yes” and sacrificing yourself may contribute to poor boundaries, leading to chronic stress which is linked to numerous health issues, including hypertension and immune dysfunction (Dai et al., 2020; Segerstrom et al., 2004; Deci & Ryan, 2008). Conversely, research indicates that individuals who assertively manage stress—rather than suppress emotions and avoid conflict—demonstrate stronger immune resilience (Ironson et al., 2005; Dantzer et al, 2018) and are better protected against burnout and prolonged emotional distress (Deci & Ryan, 2018).

When faced with illness––or even the possibly death––ask yourself: “Do I really want to do this, or am I doing it just to please my partner, children, parents, doctors, or society? By doing what truly brings me joy and meaning, what do I have to lose?” Altruism is valuable and an important part of maintaining health. At the same time boundaries and assertiveness are essential.

Psychologist Lawrence LeShan (1994) reported that when cancer patients began to seek and start singing their “own song,” their cancer regressed in numerous cases, and some experienced total remission. Living your own song means doing what you truly desire rather than following the expectations of parents, society, or economic pressures. It is important to keep in mind that while psychological factors can influence overall health, the development of cancer is a multifaceted process involving genetic, lifestyle and environmental factors.

The Key Question: When and How to Say “No”?

The answer lies in emotional awareness and acting on it. One woman with cancer confided, “I’ve operated in the realm of expected behavior for so long that I no longer know what I want or feel” (Stockdale, 2009). Teasing out our true feelings—hour by hour, as Bernie Siegel, M.D., recommends—helps us recognize where we stand (Siegel, 1986; Siegel & August, 2004). This practice fosters a sense of agency, a cornerstone of resilience that directly contributes to well-being.

For those accustomed to prioritizing others’ needs over their own, learning to say “No” takes practice. Although one may have feelings of vulnerability and even guilt by disappointing someone, one person shared that only after he stopped exclusively prioritizing others–and instead learned to love himself as well as his neighbor–did he realize how much people genuinely cared for him. Authentic connection is essential for well-being, but trust cannot develop without agency and the freedom to say “no.”

What to Do Before Automatically Saying Yes

When someone asks you for help or a favor, pause. Look up, take a slow, diaphragmatic breath, and ask yourself, “Do I want to do this? What would I recommend to another person to do in this situation?”

(In cases where you are asked or ordered to harm another person or do something illegally, ask yourself, “What would a moral person do?”)

If you feel that you would rather not—whether because you are tired or it interferes with your own priorities—say “No.” Saying “No” does not mean you are unwilling to help; it simply means that, at this moment, you are listening to yourself. When we listen to ourselves and act accordingly, we enhance our immune competence and self-healing.

Obviously, if saying “No” would put another person in danger or in crisis, then say “Yes,” if possible. However, true crises are rare. If emergencies happen frequently, they are not true crises or emergencies but rather a result of poor planning.

Saying “No” can be challenging, but if you constantly say “Yes,” you may eventually become resentful and exhausted, increasing your stress and decreasing your ability to heal. You may even notice that when your own well-being is appropriately prioritized you will be in a better position to show up for others in a whole-hearted way, when it is right for them and for you.

Saying “No” Can Be Life-Saving

Beyond personal relationships, saying “No” can be crucial in medical settings. Anthony Kaveh, M.D., a Stanford- and Harvard-trained anesthesiologist and integrative medicine specialist, asserts, “Nice patients come out last” (Kaveh, 2024). Kaveh emphasizes that trusting our instincts is crucial, as the fear of displeasing others can lead to dangerous “fake nice” behavior.

See the YouTube video #1 Mistake You Make with Doctors: Medical Secrets (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9-E3CHHX05c)

A case example is illustrated by Tracy who was hospitalized with complex fractures of the tibia and fibula. After five surgeries, she felt something was terribly wrong–she knew she was dying. However, the nurses dismissed her concerns. Taking control, she infuriated the staff by calling 911, which prompted a doctor to check on her. It was discovered that excessive negative pressure applied to the drain caused five pints of her blood to flow into her leg causing compartment syndrome.

She was bleeding to death. Tracy’s intuition, resilience, and refusal to comply saved her life. Kaveh argues that those who don’t trust their instincts are more likely to err on the side of “nice” and suffer as a result.

Learning to say “No” is empowering as illustrated by one woman who discovered its importance in a cancer educational group she attended. She shared her success in saying “No” with humor, explaining, “I just tell people it’s this group’s fault because I used to be a nice person.”

Learning to listen to yourself before agreeing or disagreeing to do something, may also help you maintain your integrity when faced with pressure to follow an immoral suggestion or order. So often due to social, economic, corporate, or political pressure, people may be asked to do something they later regret (Sah, 2025). The courage to disagree and act according to your moral consciousness is the bases of the Nuremberg Code, established by the American judges in 1947 at the Nuremberg trials for Nazi doctors (Shuster, 1997).

Finally, learning to say “No” and listen to your needs takes practice and time. Explore the following Body Dialogue technique to tap into your intuitive wisdom. You can use it anytime you need clarity about your feelings and responses to life’s challenges.

Breathe in deeply and engage all your senses. When you are ready, focus on the sensation of breathing. You don’t have to make anything happen, just feel the air moving in and out. Your lungs, vital to energy production, obtain oxygen from the atmosphere and bring it to millions of specialized cells. All without your conscious awareness, your breath moves in and out, removing toxins and waste from your body and bringing oxygen in.