Resolving a chronic headache with posture feedback and breathing

Posted: January 4, 2022 Filed under: behavior, Breathing/respiration, computer, digital devices, ergonomics, health, laptops, Neck and shoulder discomfort, Pain/discomfort, posture, relaxation, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: Desktop feedback app, headache, migraine 37 Comments| Adapted from Peper, E., Covell, A., & Matzembacker, N. (2021). How a chronic headache condition became resolved with one session of breathing and posture coaching. NeuroRegulation, 8(4), 194–197. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.8.4.194 |

This blog describes the process by which a 32 year old woman student’s chronic headaches that she had since age eighteen was resolved in a single coaching session. The student suffered two or three headache per week a week which initially began when she was eighteen after using digital devices and encouraged her to slouch as she looked down. Although she describes herself as healthy, she reported having high level of anxiety and occasional depression. She self-medicated with 2 to 10 Excedrin tablets a week. It is possible that the chronic headaches could partially be triggered by caffeine withdrawal which get resolved by taking more Excedrins (Greben et al., 1980) since Excedrin contains 65 mg of caffeine as well as 250 mg of Acetaminophen which can be harmful to liver function (Bauer et al., 2021).

The behavioral coaching intervention

During the first day in class, the student approached the instructor and she shared that she had a severe headache. During their conversation, the instructor noticed that she was breathing in her chest without abdominal movement, her shoulders were held tight, her posture slightly slouched and her hands were cold. As she was unaware of her body responses, the instructor offered to guide her through some practices that may be useful to reduce her headache. The same strategies could also be useful for the other students in the class; since, headaches, anxiety, zoom fatigue, neck and shoulder tension, abdominal discomfort, and vision problems are common and have increased as people spent more time in front of screens (Charles et al., 2021; Ahmed et al., 2021; Bauer, 2021; Kuehn, 2021; Peper et al., 2021 ).

These symptoms may occur because of bad posture, neck and shoulder tension, shallow chest breathing, stress and social isolation (Elizagaray-Garcia et al., 2020; Schulman, 2002). When people become aware of their dysfunctional somatic patterns and change their posture, breathing pattern, internal language and implement stress management techniques, they often report a reduction in symptoms such as irritable bowel syndrome, acid reflux, neck and shoulder tension, or anxiety (Peper et al, 2017a; Peper et al, 2016a). Sometimes, a single coaching session can be sufficient to improve health.

Working hypothesis: The headaches were most likely tension headaches and not migraines and may be the result of chronic neck and shoulder tension which was maintained during chest breathing and the slouched head forward body posture. If she could change her posture, relax her neck and shoulders, and breathe diaphragmatically so that the lower abdomen widen during inhalation, most likely her shoulder and neck tension would decrease. Therefore, by changing posture from a slouched to upright position combined with slower diaphragmatic breathing, the muscle tension would be reduced and the headaches would decrease.

Breathing and posture changes

She was encouraged to sit upright so that the abdomen had space to expand (Peper et al., 2020). In addition, she needed to loosen the clothing around her waist to provide room for her abdomen to expand during inhalation instead of her chest lifting (MacHose & Peper, 1991). Allowing abdominal expansion can be challenging for many paticipants since they are self-conscious about their body image, as well holding their stomach in as an unconscious learned response to avoid pain after having had abdominal surgery, or as an automatic protective response to threat (Peper et al., 2015). The upright position also allowed her to sit tall and erect in which the back of head reaches upward towards the ceiling while relaxing and feeling gravity pulling her shoulders downward and at the same time relaxing her hips and legs.

With guided verbal and tactile coaching, she learned to master slower diaphragmatic breathing in which she gently and slowly exhaled by making a sound of pssssssst (exhaling through pursed lips) which tends to activate the transverse and oblique abdominal muscles and slightly tighten the pelvic floor muscles so that her lower abdomen would slightly constrict at the end of the exhalation (Peper et al., 2016). Then, by allowing the lower abdomen and pelvic floor relax so that the abdomen could expand in 360 degrees, inhalation occurred.

While practicing the slower breathing in this relaxed upright position, she was instructed to sense/imagine feeling a flow of down and through her arms and out her hands as she exhaled (as if the air could flow through straws down her arms). After a few minutes, she felt her headache decrease and noticed that her hands had warmed. After this short coaching intervention, she went back to her seat in class and continued to practice the relaxed effortless breathing while sitting upright and allowing her shoulders to melt downward.

The use of muscle feedback to demonstrate residual covert muscle tension

During class session, she volunteered to have her trapezius muscle monitored with electromyography (EMG). The EMG indicated that her muscles were slightly tense even though she reported feeling relaxed. With a few minutes of EMG biofeedback exploration, she discovered that she could relax her shoulder muscles by feeling them being heavy and melting.

Implementing home practice with a posture app

As part of the class homework, she was assigned a self-study for two weeks with the posture feedback app, Dario Desktop. The app uses the computer/laptop camera to monitor posture and provides visual feedback in a small window on the computer screen and/or an auditory signal each time she slouches as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Posture feedback to signal to participant that the person is slouching.

To observe the effect of the posture breathing training, she monitored her symptoms for three days without feedback and then installed the posture feedback application on her laptop to provide feedback whenever she slouched. The posture feedback reminded her to practice better posture during the day while working on her computer and also do a few stretches or shift to standing when using the computer for an extended period of time. Each time the feedback signal indicated she slouched, she would sit up and change her posture, breathe lower and slower and relax her shoulders.

She also monitored what factors triggered the slouching. In additionally, she added daily reminders to her phone to remind her of her posture and to stretch and stand after each hour of studying. After two weeks she recorded her symptoms for three days for the post assessment without posture feedback.

Results

The chronic headache condition which had been present for fourteen years disappeared and she has not used any medication since the first day of class. She reported after two weeks that her shoulder and back discomfort/pain, depression, anxiety and lack of motivation decreased as shown in Figure 2. At the fourteen week follow up, she continues to have no headaches and has not used any medication.

Figure 2. Changes in symptoms after implementing posture feedback for two weeks.

She used the desktop posture app every time she opened her laptop at home as often as 3-5 times per day (roughly 2-6 hours).In addition, when she felt beginning of discomfort or thought she should take medication, she would adjust her posture and breathe. While using the app, she identified numerous factors that were associated with slouching as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Behaviors associated with slouching.

Discussion

The decrease in depression, anxiety and increase in motivation may be the direct result of posture change; since, a slouched position tends to increase hopeless, helpless and powerless thoughts while the upright position tends to increase subjective felt energy and easier access to empowering and positive thoughts (Peper et al., 2017b; Veenstra et al., 2017; Wilson & Peper, 2004; Tsai et al., 2016). Most likely, a major factor that contributed to the elimination of her headaches was that she implemented changes in her behavior. One major factor was using posture feedback tool at home to remind her to sit tall and relax her shoulders while practicing slower diaphragmatic breathing. As she noted, “Although it was distracting to be reminded all the time about my posture, it did decrease my neck pain. With the pain reduction, I was able to sit at the computer longer and felt more motivated.”

The combination of slower lower abdominal breathing with the upright posture reversed her protective/defensive body position (tightening the muscle in the lower abdomen and pelvic floor and pressing the knees together while curling the shoulder forward for protection). The upright posture creates a position of empowerment and trust by which the lower abdomen could expand which supported health and regeneration. In addition, the upright posture allowed easier access to positive thoughts and reduced recall of hopeless, powerless, defeated memories. It is also possible that caffeine withdrawal was a co-factor in evoking headaches (Küçer, 2010). By eliminating the medication containing caffeine, she also eliminated the triggering of the caffeine withdrawal headaches.

This case example suggests that health care providers first rule out any pathology and then teach behavioral self-healing strategies that the clients can implement instead of immediately prescribing medications. These interventions could include slower and lower diaphragmatic breathing, upright posture feedback, muscle biofeedback training, hear rate variability training, stress management, cognitive behavior therapy and facilitating health promoting lifestyles modifications such as regular sleep, exercise and healthier diet. When students implement these behavioral changes as part of a five week self-healing program, many report significant decreases in symptoms such as headaches, anxiety, neck and shoulder pain, and gastrointestinal distress (Peper et al., 2016a).

Watch April Covell describe her experience with the self-healing approach to eliminate her chronic headaches.

See the following blogs for additional instructions how to breathe diaphragmatically.

References

Ahmed, S., Akter, R., Pokhrel, N. et al. (2021). Prevalence of text neck syndrome and SMS thumb among smartphone users in college-going students: a cross-sectional survey study. J Public Health (Berl.) 29, 411–416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-019-01139-4

Bauer, A.Z., Swan, S.H., Kriebel, D. et al. (2021). Paracetamol use during pregnancy — a call for precautionary action. Nat Rev Endocrinol . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-021-00553-7

Charles, N. E., Strong, S. J., Burns, L. C., Bullerjahn, M. R., & Serafine, K. M. (2021). Increased mood disorder symptoms, perceived stress, and alcohol use among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry research, 296, 113706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113706

Elizagaray-Garcia, I., Beltran-Alacreu, H., Angulo-Díaz, S., Garrigós-Pedrón, M., Gil-Martínez, A. (2020). Chronic Primary Headache Subjects Have Greater Forward Head Posture than Asymptomatic and Episodic Primary Headache Sufferers: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Pain Med, 21(10):2465-2480. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnaa235

Greden, J.F., Victor, B.S., Fontaine, P., & Lubetsky, M. (1980). Caffeine-Withdrawal Headache: A Clinical Profile. Psychosomatics, 21(5), 411-413, 417-418. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0033-3182(80)73670-8

Küçer, N. (2010). The relationship between daily caffeine consumption and withdrawal symptoms: a questionnaire-based study. Turk J Med Sci, 40(1), 105-108. https://doi.org/10.3906/sag-0809-26

Kuehn, B.M. (2021). Increase in Myopia Reported Among Children During COVID-19 Lockdown. JAMA, 326(11),999. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.14475

MacHose, M. & Peper, E. (1991). The effect of clothing on inhalation volume. Biofeedback and Self-Regulation 16, 261–265 (1991). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01000020

Peper, E., Booiman, A., Lin, I-M, Harvey, R., & Mitose, J. (2016). Abdominal SEMG Feedback for Diaphragmatic Breathing: A Methodological Note. Biofeedback. 44(1), 42-49. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-44.1.03

Peper, E., Gilbert, C.D., Harvey, R. & Lin, I-M. (2015). Did you ask about abdominal surgery or injury? A learned disuse risk factor for breathing dysfunction. Biofeedback. 34(4), 173-179. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-43.4.06

Peper, E., Lin, I-M., Harvey, R., & Perez, J. (2017b). How posture affects memory recall and mood. Biofeedback. 45 (2), 36-41. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-45.2.01

Peper, E., Mason, L., Harvey, R., Wolski, L, & Torres, J. (2020). Can acid reflux be reduced by breathing? Townsend Letters-The Examiner of Alternative Medicine, 445/446, 44-47. https://www.townsendletter.com/article/445-6-acid-reflux-reduced-by-breathing/

Peper, E., Mason, L., Huey, C. (2017a). Healing irritable bowel syndrome with diaphragmatic breathing. Biofeedback. (45-4). https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-45.4.04

Peper, E., Miceli, B., & Harvey, R. (2016a). Educational Model for Self-healing: Eliminating a Chronic Migraine with Electromyography, Autogenic Training, Posture, and Mindfulness. Biofeedback, 44(3), 130–137. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-44.3.03

Peper, E., Wilson, V., Martin, M., Rosegard, E., & Harvey, R. (2021). Avoid Zoom fatigue, be present and learn. NeuroRegulation, 8(1), 47–56. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.8.1.47

Schulman, E.A. (2002). Breath-holding, head pressure, and hot water: an effective treatment for migraine headache. Headache, 42(10), 1048-50. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1526-4610.2002.02237.x

Tsai, H. Y., Peper, E., & Lin, I. M.* (2016). EEG patterns under positive/negative body postures and emotion recall tasks. NeuroRegulation, 3(1), 23-27. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.3.1.23

Veenstra, L., Schneider, I.K., & Koole, S.L. (2017). Embodied mood regulation: the impact of body posture on mood recovery, negative thoughts, and mood-congruent recall. Cogntion and Emotion, 31(7), 1361-1376. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2016.1225003

Wilson, V.E. and Peper, E. (2004). The effects of upright and slumped postures on the generation of positive and negative thoughts. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 29(3), 189–195. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:apbi.0000039057.32963.34

Healing from paralysis-Music (toning) to activate health

Posted: November 22, 2021 Filed under: behavior, Breathing/respiration, emotions, healing, health, mindfulness, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: chakra, chanting, music therapy, paralysis, quadriplegia, singing, Toning 8 CommentsMadhu Anziani and Erik Peper

In April 2009, Madhu Anziani, just one month prior to graduation from San Francisco State University with a degree in Jazz/World music performance, fell two stories and broke C5 and C7 vertebras. He became a quadriplegic (tretraplegia) and could not breathe, talk, move his arms and legs and was incontinent. He also could not remember anything about the accident because of retrograde amnesia. Even though he was paralyzed and the medical staff suggested that he focussed on how to live well as a quadriplegic, he transcended his paralysis and the prognosis and is now a well-known vocal looping arts and ceremonial song leader/composer.

His recovery against all odds provides hope that growth and healing is possible when the mind and spirit focus on possibilities and not on limitations. Alongside physical thereapy he utilized energy healing and toning/sound vibrations to recover mobility. Toning, the vocalization of an elonggated monotonous vowel sound susteained for a number of minutes tends to vibrate specific areas in the body where the chakras are located (Crowe & Scovel, 1996; Goldman, 2017). Toning compared to mindfulness meditation reduces intrusive thoughts and mind wandering. It also increases body vibration sensations and heart rate variability much more than mindfulness practice (Peper et al, 2019). The body vibrations induced by toning and music could be one of the mechanisms by which recovery can occur at an accelerated rate as it allows the person’s passive awareness and sustained attention to feel the paralyzed body and yet be relaxed in the present without judgement.

Watch Madhu’s inspirational presentation as part of the Holistic Health Lecture Series by the Institute for Holistic Health Studies, San Francisco State University. In this presentation, he describes the process of recovery and guides the viewer through toning practices to evoke quieting of mind, bliss within the heart, and a healing state of being.

For an additional discussion and guided practice in toning, see the blog, Toning quiets the mind and increases HRV more quickly than mindfulness practice.

Madu Anziani is a sound healer who endured being a tetraplegic (paralysis affecting all four

limbs) and used sound and energy healing to recover mobility. He is a SFSU graduate and most

well-known as a vocal looping artist and ceremonial song leader/composer.

http://www.firstwasthesound.com

http://madhu.bandcamp.co

REFERENCES:

Goldman, J. (2017). The 7 Secrets of Sound Healing. Carlsbad, CA: Hay House Inc.

Reduce the spread of COVID and influenza by improving building ventilation

Posted: September 14, 2021 Filed under: behavior, Breathing/respiration, COVID, health | Tags: air circulation, airborne pathogens, Cholera, influenza, John Snow, ventilation 1 CommentAdapted from the superb article by Sarah Zhang, The plan to stop every respiratory virus at once. The Atlantic. (September 7, 2021).

With good clean air circulation, the risk of transmitting or contracting airborne disease such as COVID-19 during air travel is very low (Pombal, Hosegood & Powell, 2020). Pombal, Hosegood & Powell, 2020 point out that modern airplanes maintain clean air by circulating a mix of fresh air and air recycled through HEPA filter. Air enters from overhead air inlets and flows downward toward floor level outlets at the same seat row or nearby rows. There is little airflow forward and backward between rows.

The risk of transmission or contracting airborne dieases is very high if the airplane ventilation system is not working while passengers are in the plane. For example, when a jet airliner with 54 persons aboard was delayed on the ground for three hours with an inoperative ventilation system 72 % of the passengers became ill with symptoms of cough, fever, fatigue, headache, sore throat and myalgia within 72 hours (Moser et al.,1979).

To reduce the risk of COVID and other airborne infections such as influenza, government policies need to implement strategies to reduce exposure to airborne pathogens and optimize the immune system. By improving ventilation that reduces and removes airborne pathogens, thousands, if not millions, lives will be saved from being infected or dying of COVID or influenza.

Before the COVID pandemic between 2010 and 2020 an average of 39,900 people a year died of influenza in the United States and during a severe influenza season such as that occurred in 2017-2018, 61,000 people died (CDC, 2021). Influenza, just as COVID, is caused by an airborne pathogens (viruses). Although wearing masks significantly reduces the airborne spread of the pathogens, the long term preventative solution is to implement indoor ventilation strategies so that the air is not contaminated in the same way that we expect drinking water not to cause illness. From a public health perspective, changing external environment so the virus is cannot spread is a more effective strategy than depending upon individuals’ actions to prevent the spread of the pathogens.

By improving the air filtration and fresh air circulation in rooms and buildings, COVID, influenza virus and other airborne pathogens can be significantly reduced just as that has been done in modern airplanes. This demands changes in building ventilation codes and design. It means changing the physical infrastructure and upgrading ventilation systems so that only fresh and/or filtered air circulates through the rooms. This infrastructure improvement would be analogous to what occurred in the 19th century in eventually eliminating the cholera epidemics that killed thousands of people a year.

For example in England during the 1831-1832 and 1848 cholera epidemics more than 50,000 people died each year as they became infected with the toxigenic bacterium Vibrio cholerae which was present the water or foods contaminated with feces from a a person infected with cholera bacterium. Approximately 1 in 10 people who get sick with cholera will develop severe symptoms and without treatment, death can occur within hours (CDC, 2021).

In Londong during the 1854 cholera epidemic Dr. John Snow observed that people who got cholera were drawing water from a the same water pump on Broad Street. He persuaded the authorities to remove the pump handle which eliminated the use of the contaminated water and stopped the spread of the Cholera.

The water pump in Broadwick Street.

This public health intervention provided some of the rationale in 19th century to build the infrastructure to provide clean drinking water and appropriate sewage disposal, so that cholera, typhoid as well as other waterborne diseases epidemics would not enter the drinking water supply.

We now need a similar infrastructure improvement to provide clean air in buildings to stop the spread of COVID-19 variants and influenza. How ventilation affects the spread a virus in a class room is illustrated in the outstanding graphical modeling by Nick Bartzokas et al. (February 26, 2021) in the New York Times article, Why opening windows is a key to reopening schools. The spatial guidelines need to be based upon air flow and not on the distance of separation.

In summary, to prevent future airborne illnesses, local, state and federal government need to create and implement ventilation standards so that airborne pathogens are not spread indoors by contaminated air. This is not rocket science! It is a very solvable problem and has been implemented in airplanes. When the air is HEPA filtered so that passengers do not rebreathe each other’s potentially contaminated exhaled air, airborne transmission is very low. Let’s do the same for the air circulating in buildings.

For an indepth analyses, read the superb article, The Plan to Stop Every Respiratory Virus at Once, by Sarah Zhang published September 7, 2021 in the The Atlantic.

For more details to reduce virus exposure and increase immune competence, see the previoius published blogs,

https://peperperspective.com/2021/07/05/reduce-your-risk-of-covid-19-variants-and-future-pandemics/

REFERENCES

CDC (2021). Disease Burden of Influenza. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/burden/index.html

Moser, M.R., Bender, T.R., Margolis, H.S., Noble, G.R., Kendal, A.P., & Ritter, D.G. (1979). An outbreak of influenza aboard a commercial airliner. Am J Epidemiol, 110(1), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112781

Pombal, R., Hosegood, I., & Powell, D. (2020). Risk of COVID-19 During Air Travel. JAMA, 324(17), 1798 https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.19108

Zhang, S. (September 7, 2021). The plan to stop every respiratory virus at once. The Atlantic. Downloaded September 13. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2021/09/coronavirus-pandemic-ventilation-rethinking-air/620000/

Useful resources about breathing, phytonutrients and exercise

Posted: June 30, 2021 Filed under: behavior, Breathing/respiration, cancer, Evolutionary perspective, health, Nutrition/diet, self-healing, Uncategorized | Tags: diet, exercise, immune system, nasal breathing, phytonutrients, respiration 1 Comment

Dysfunctional breathing, eating highly processed foods, and lack of movement contribute to development of illnesses such as cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease and many chronic diseases. They also contributes to immune dysregulation that increases vulnerability to infectious diseases, allergies and autoimmune diseases. If you wonder what breathing patterns optimize health, what foods have the appropriate phytonutrients to support your immune system, or what the evidence is that exercise reduces illness and promotes longevity, look at the following resources.

Breath: the mind-body connector that underlies health and illness

Read the outstanding article by Martin Petrus (2021). How to breathe.

https://psyche.co/guides/how-to-breathe-your-way-to-better-health-and-transcendence

You are the food you eat

Watch the superb webinar presentation by Deanna Minich, MS., PHD., FACN, CNS, (2021) Phytonutrient Support for a Healthy Immune System.

Movement is life

Explore the summaries of recent research that has demonstrated the importance of exercise to increase healthcare saving and reduce hospitalization and death.

Clean the air with plants*

Posted: March 22, 2021 Filed under: Breathing/respiration, ergonomics, health, Uncategorized | Tags: air pollution, plants Leave a comment

Fresh clean air is essential for health while polluted air is an environmental health hazard. For more than fifty years the harm of air pollution has been documented. As the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIH NIEHS) points out, initially air pollution was primarily regarded as threat to respiratory health and contributed to an increases in asthma, emphysema, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and chronic bronchitis. More recently, air pollution has been identified as a significant risk factor for cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, obesity, reproductive, neurological, and immune system disorders and ADHD (Keller et al., 2018; Perera et al, 2014; NIH NIEHS ).

Yet many of us are unaware that often the air we breathe indoors is even more polluted than the outside air. The indoor air is the sum of outdoor air plus the indoor air pollution produced from cooking and outgassing of the volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from the many materials (Wolkoff, 2028). Materials and equipment in home and office also shed micro dust particles and outgas a chemical brew of volatile organic compounds (e.g., formaldehyde, benzene and tricholorethylene). These VOCs come from paper, inks, furniture, carpet, paints, wall coverings, cleaning materials, floor tiles and the fumes produced from gas heaters and cooking stoves. In addition, copiers and laser printers often add microscopic dust particles and sometimes ozone. These gasses stay in the room where there is limited air circulation due to sealed buildings or closed windows. Reduced air circulation is also a significant risk factor for COVID-19; since, the virus keeps recirculating in unventilated rooms. See the superb graphic illustration by Bartzokas et al (Feb 26, 2021).in the New York Times of virus concentration in schools when the windows are opened. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/02/26/science/reopen-schools-safety-ventilation.html?smid=em-share).

Be proactive to reduce pollution and enhance your health by placing plants in your office and home. When the plants are placed in the office, they also enhances subjective perceptions of air quality, concentration, and workplace satisfaction as well as objective measures of productivity (Nieuwenhuis et al., 2014). Certain plants help remove carbon dioxide and convert it to oxygen, clear the indoor smog, and remove the volatile organic compounds. Warning: Be sure that your pets do not chew or eat the leaves of these plants because they could be poisonous (e.g., azaleas are poisonous for dogs and cats),

The following plants help remove carbon dioxide and by converting it into oxygen.

- Areca Palm. You will need four shoulder height plants per person to convert all the exhaled carbon dioxide into oxygen (Meattle, 20009; Meattle, 2018).

- Mother-in-law’s Tongue is a bedroom plant because it converts carbon dioxide into oxygen at night. You will need six to eight shoulder height plants per person (Meattle, 20009).

Watch Kamal Meattle short TED talk presentation, How to grow fresh air (for an updated longer presentation watch, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KXgWxRUGLwM). https://www.ted.com/talks/kamal_meattle_how_to_grow_fresh_air?language=en#t-100683

The following plants remove VOCs from the air (Wolverton, 2020).

- Azaleas, rubber plants, tulips, poinsettia, philodendron, money plant, and bamboo palms (formaldehyde)

- Areca palm (toluene)

- Lady palm (ammonia)

- Peace lily and chrysanthemum (acetone, methanol, trichlorethylene, benzene, ethylacetate)

To remove particulates, install an air purifier with a HEPA filter.

After renovation or installation of furniture or carpets, be sure to allow for air circulation by opening windows and doors. Explore some of the following strategies to clean the air:

- Turn the exhaust fan on when cooking and using the oven.

- Ventilate your work area (open a window or door, if possible).

- Move copier/laser printers to a well-ventilated space and/or place an exhaust fan near the printer.

- Turn off copier or laser printers when not in use (purchase new equipment that is energy efficient and shuts down when not in use).

Take a many walks outside in nature

If possible take a walk at lunch or ask coworkers to have a walking meeting so that you can get out in the fresh air. Being in nature and forest bathing (Shinrin-Yoku) is associated with a decrease in stress, regeneration and improvement in immune function (Park et al., 2010; Hansen et a., 2017; Lyu et al., 2019). Watch the presentation by Dr. Aiko Yoshino, Soaking Up the Benefits of Nature During the PandemicForum.

* Adapted from Peper, E. (2023). Clean air with plants. Townsend Letters. The Examiner of Alternative Medicine, Sunday, June 4, 2023. https://www.townsendletter.com/e-letter-11-using-plants-to-improve-indoor-air-quality/

Republished: Peper, E. (2024). Townsend e-Letter, Townsend Letters. The Examiner of Alternative Medicine, June 3, 2024. https://www.townsendletter.com/e-letter-11-using-plants-to-improve-indoor-air-quality/

References:

Meattle, K. (2018). How to grow fresh air inside your house amidst pollution. Quint Fit. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KXgWxRUGLwM

Nieuwenhuis, M., Knight, C., Postmes, T., & Haslam, S. A. (2014). The relative benefits of green versus lean office space: Three field experiments. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 20(3), 199–214. https://doi.org/10.1037/xap0000024

NIH NIEHS, Air Pollution and Your Health, National Institute of Health, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences https://www.niehs.nih.gov/health/topics/agents/air-pollution/index.cfm#:~:text=Air%20pollution%20can%20affect%20lung,are%20linked%20to%20chronic%20bronchitis

Resolve Eyestrain and Screen Fatigue

Posted: June 29, 2020 Filed under: Breathing/respiration, computer, digital devices, ergonomics, Exercise/movement, health, laptops, Neck and shoulder discomfort, Pain/discomfort, relaxation, stress management, Uncategorized, vision | Tags: blurry vision, computer vision syndrome, dry eyes, eyestrain, near vision stress, zoom fatigue 13 CommentsAdapted from: Peper, E., Harvey, R. & Faass, N. (2020). TechStress: How Technology is Hijacking Our Lives, Strategies for Coping, and Pragmatic Ergonomics. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books.

Forty percent of adults and eighty percent of teenagers report experiencing significant visual symptoms (eyestrain, blurry vision, dry eyes, headaches, and exhaustion) during and immediately after viewing electronic displays. These ‘technology-associated overuse’ symptoms are often labeled as digital eyestrain or computer vision syndrome (Rosenfield, 2016; Randolph & Cohn, 2017). Even our distant vision may be affected— after working in front of a screen for hours, the world looks blurry. At the same time, we may experience an increase in neck, shoulders and back discomfort. These symptoms increase as we spend more hours looking at computer screens, laptops, tablets, e-readers, gaming consoles, and cellphones for work, taking online classes, watching streaming videos for entertainment, and keeping connected with friends and family (Borhany et al, 2018; Turgut, 2018; Jensen et al, 2002).

Eye, head, neck, shoulder and back discomfort are partly the result of sitting too long in the same position and attending to the screen without taking short physical and vision breaks, moving our bodies and looking at far objects every 20 minutes or so. The obvious question is, “Why do we stare at and are captured by, the screen?” Two answers are typical: (1) we like the content of what is on the screen; and, (2) we feel compelled to watch the rapidly changing visual scenes.

From an evolutionary perspective, our sense of vision (and hearing) evolved to identify predators who were hunting us, or to search for prey so we could have a nice meal. Attending to fast moving visual changes is linked to our survival. We are unaware that our adaptive behaviors of attending to a visual or auditory signals activate the same physiological response patterns that were once successful for humans to survive–evading predictors, identifying food, and discriminating between friend or foe. The large and small screen (and speakers) with their attention grabbing content and notifications have become an evolutionary trap that may lead to a reduction in health and fitness (Peper, Harvey & Faass, 2020).

Near vision stress

To be able to see the screen, the eyes need to converge and accommodate. To converge, the extraocular muscles of the eyes tighten; to focus (accomodation), the ciliary muscle around the lens tighten to increase the curvature of the lens. This muscle tension is held constant as long as we look at the screen. Overuse of these muscles results is near vision stress that contributes to computer vision syndrome, development of myopia in younger people, and other technology-associated overuse syndromes (Sherwin et al, 2012; Enthoven et al, 2020).

Continually overworking the visual muscles related to convergences increases tension and contributes to eyestrain. While looking at the screen, the eye muscles seldom have the chance to relax. To function effectively, muscles need to relax /regenerate after momentary tightening. For the eye muscles to relax, they need to look at the far distance– preferably objects green in color. As stated earlier, the process of distant vision occurs by relaxing the extraocular muscles to allow the eyes to diverge along with relaxing the ciliary muscle to allow the lens to flatten. In our digital age, where screen of all sizes are ubiquitous, distant vision is often limited to the nearby walls behind a screen or desk which results in keeping the focus on nearby objects and maintaining muscular tension in the eyes.

As we evolved, we continuously alternated between between looking at the far distance and nearby areas for food sources as well as signals indicating danger. If we did not look close and far, we would not know if a predator was ready to attack us. Today we tend to be captured by the screens. Arguably, all media content is designed to capture our attention such as data entry tasks required for employment, streaming videos for entertainment, reading and answering emails, playing e-games, responding to text notifications, looking at Instagram and Snapchat photos and Tiktok videos, scanning Tweets and using social media accounts such as Facebook. We are unaware of the symptoms of visual stress until we experience symptoms. To illustrate the physiological process that covertly occurs during convergence and accommodation, do the following exercise.

Sit comfortably and lift your right knee a few inches up so that the foot is an inch above the floor. Keep holding it in this position for a minute…. Now let go and relax your leg.

A minute might have seemed like a very long time and you may have started to feel some discomfort in the muscles of your hip. Most likely, you observed that when you held your knee up, you most likely held your breath and tightened your neck and back. Moreover, to do this for more than a few minutes would be very challenging.

Lift your knee up again and notice the automatic patterns that are happening in your body.

For muscles to regenerate they need momentary relaxation which allows blood flow and lymph flow to occur. By alternately tensing and relaxing muscles, they can work more easily for longer periods of time without experiencing fatigue and discomfort (e.g., we can hike for hours but can only lift our knee for a few minutes).

Solutions to relax the eyes and reduce eye strain

- Reestablish the healthy evolutionary pattern of alternately looking at far and near distances to reduce eyestrain, such as:

- Look out through a window at a distant tree for a moment after reading an email or clicking link.

- Look up and at the far distance each time you have finished reading a page or turn the page over.

- Rest and regenerate your eyes with palming. While sitting upright, place a pillow or other supports under our elbows so that your hands can cover your closed eyes without tensing the neck and shoulders.

- Cup the hands so that there is no pressure on your eyeballs, allow the base of the hands to touch the cheeks while the fingers are interlaced and resting your forehead.

- Close your eyes, imagine seeing black. Breathe slowly and diaphragmatically while feeling the warmth of the palm soothing the eyes. Feel your shoulders, head and eyes relaxing. Palm for 5 minutes while breathing at about six breaths per minute through your nose. Then stretch and go back to work.

Palming is one of the many practices that improves vision. For a comprehensive perspective and pragmatic exercises to reduce eye strain, maintain and improve vision, see the superb book by Meir Schneider, PhD., L.M.T., Vision for Life, Revised Edition: Ten Steps to Natural Eyesight Improvement.

Increased sympathetic arousal

Seeing the changing stimuli on the screen evokes visual attention and increases sympathetic arousal. In addition, many people automatically hold their breath when they see novel visual or hear auditory signals; since, they trigger a defense or orienting response. At the same time, without awareness, we may tighten our neck and shoulder muscles as we bring our nose literally to the screen. As we attend and concentrate to see what is on the screen, our blinking rate decreases significantly. From an evolutionary perspective, an unexpected movement in the periphery could be a snake, a predator, a friend or foe and the body responds by getting ready: freeze, fight or flight. We still react the same survival responses. Some of the physiological reactions that occur include:

- Breath holding or shallow breathing. These often occur the moment we receive a text notification, begin concentrating and respond to the messages, or start typing or mousing. Without awareness, we activate the freeze, flight and fight response. By breath holding or shallow breathing, we reduce or limit our body movements, effectively becoming a non-moving object that is more difficult to see by many animal predators. In addition, during breath holding, hearing become more acute because breathing noises are effectively reduced or eliminated.

- Inhibition of blinking. When we blink it is another movement signal that in earlier times could give away our position. In addition, the moment we blink we become temporarily blind and cannot see what the predator could be doing next.

- Increased neck, shoulder and back tension. The body is getting ready for a defensive fight or avoidance flight.

Experience some of these automatic physiological responses described above by doing the following two exercises.

Eye movement neck connection: While sitting up and looking at the screen, place your fingers on the back of the neck on either side of the cervical spine just below the junction where the spine meets the skull.

Feel the muscles of neck along the spine where they are attaching to the skull. Now quickly look to the extreme right and then to the extreme left with your eyes. Repeat looking back and forth with the eyes two or three times.

What did you observe? Most likely, when you looked to the extreme right, you could feel the right neck muscles slightly tightening and when you looked the extreme left, the left neck muscles slightly tightening. In addition, you may have held your breath when you looked back and forth.

Focus and neck connection: While sitting up and looking at the screen, place your fingers on the back of the neck as you did before. Now focus intently on the smallest size print or graphic details on the screen. Really focus and concentrate on it and look at all the details.

What did you observe? Most likely, when you focused on the text, you brought your head slightly forward and closer to the screen, felt your neck muscles tighten, and possibly held your breath or started to breathe shallowly.

As you concentrated, the automatic increase in arousal, along with the neck and shoulder tension and reduced blinking contributes to developing discomfort. This can become more pronounced after looking at screens to detailed figures, numerical data, characters and small images for hours (Peper, Harvey & Tylova, 2006; Peper & Harvey, 2008; Waderich et al, 2013).

Staying alert, scanning and reacting to the images on a computer screen or notifications from text messages, can become exhausting. in the past, we scanned the landscape, looking for information that will help us survive (predators, food sources, friend or foe) however today, we react to the changing visual stimuli on the screen. The computer display and notifications have become evolutionary traps since they evoke these previously adaptive response patterns that allowed us to survive.

The response patterns occur mostly without awareness until we experience discomfort. Fortunately, we can become aware of our body’s reactions with physiological monitoring which makes the invisible visible as shown in the figure below (Peper, Harvey & Faass, 2020).

Representative physiological patterns that occur when working at a computer, laptop, tablet or cellphone are unnecessary neck and shoulder tension, shallow rapid breathing, and an increase in heart rate during data entry. Even when the person is resting their hands on the keyboard, forearm muscle tension, breathing and heart rate increased.

Moreover, muscle tension in the neck and shoulder region also increased, even when those muscles were not needed for data entry task. Unfortunately, this unnecessary tension and shallow breathing contributes to exhaustion and discomfort (Peper, Harvey & Faass, 2020).

With biofeedback training, the person can learn to become aware and control these dysfunctional patterns and prevent discomfort (Peper & Gibney, 2006; Peper et, 2003). However, without access to biofeedback monitoring, assume that you respond similarly while working. Thus, to prevent discomfort and improve health and performance, implement the following.

- Practice breathing lower and slower to reduce sympathetic activation. Every few minutes remember to breathe slowly in and out through the nose. See the following blogs for more detailed instructions:

- Blink many times. Blink each time you click on a link, after typing a paragraph or after entering a few numbers.

- Get up, move, stretch and wiggle.

- Every few minutes do a small movement such as rotating your shoulders, dropping your hands to your lap.

- Every twenty minutes get up, stretch and walk around to reduce the chronic muscle tension.

- Install the free Stretch Break software on your computer or laptop to remind you to stretch… and then shows you how. Download free version from: https://stretchbreak.com/.

- Use small portable muscle biofeedback devices to learn awareness of the covert muscle tension and how to work without unnecessary muscle tension. For detailed training procedures see the free downloadable book by Erik Peper and Katherine Gibney, Muscle Biofeedback at the Computer- A Manual to Prevent Repetitive Strain Injury (RSI) by Taking the Guesswork out of Assessment, Monitoring and Training.

Finally, for a comprehensive overview based on an evolutionary perspective that explains why TechStress develops, why digital addiction occurs. and what can be done to prevent discomfort and improve health and performance, see our new book by Erik Peper, Richard Harvey and Nancy Faass, Tech Stress-How Technology is Hijack our Lives, Strategies for Coping and Pragmatic Ergonomics.

References

Peper, E. & Gibney, K. (2006). Muscle Biofeedback at the Computer- A Manual to Prevent Repetitive Strain Injury (RSI) by Taking the Guesswork out of Assessment, Monitoring and Training. The Biofeedback Federation of Europe. Download free PDF version of the book: http://bfe.org/helping-clients-who-are-working-from-home/

Schneider, M. (2016). Vision for Life, Revised Edition: Ten Steps to Natural Eyesight Improvement. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books. https://self-healing.org/shop/books/vision-for-life-2nd-ed

Turgut, B. (2018). Ocular Ergonomics for the Computer Vision Syndrome. Journal Eye and Vision, 1(2).

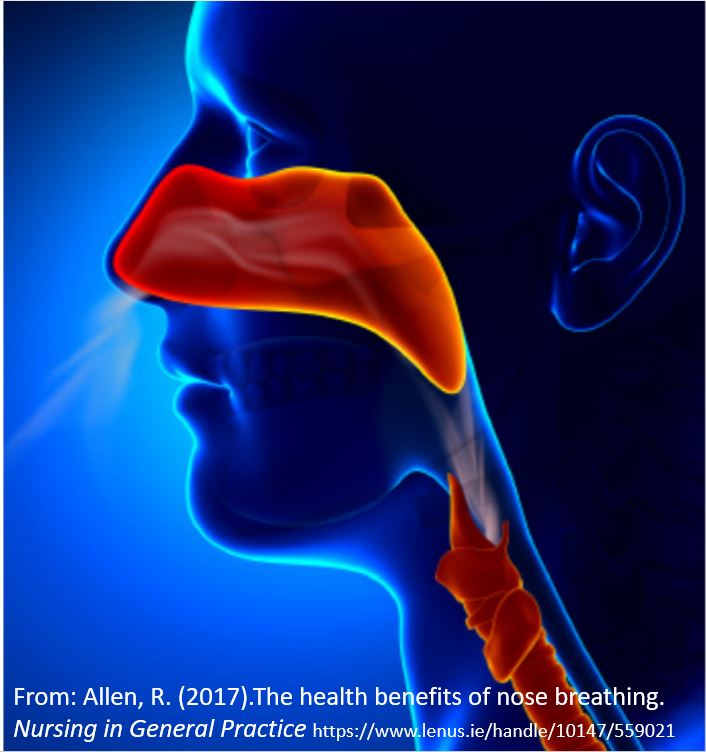

Do nose breathing FIRST in the age of COVID-19

Posted: May 30, 2020 Filed under: Breathing/respiration, health, self-healing, Uncategorized | Tags: anxiety, COVID-19, HRV, nasal breathing, respiration 4 Comments

Breathing affects every cell of our body and should be the first intervention strategy to improve physical and mental well-being (Peper & Tibbetts, 1994). Breathing patterns are much more subtle than indicated by the respiratory function tests (spirometry, lung capacity, airway resistance, diffusing capacity and blood gas analysis) or commonly monitored in medicine and psychology (breathing rate, tidal volume, peak flow, oxygen saturation, end-tidal carbon dioxide) (Gibson, Loddenkemper, Sibille & Lundback, 2019).

When a person feels safe, healthy and peaceful, the breathing is effortless and the breath flows in and out of the nose without awareness. Functional and dysfunctional breathing patterns includes an assessment of the whole body pattern by which breathing occurs such as nose versus mouth breathing, alternation of nasal patency, the rate of air flow rate during inhalation and exhalation, the length of time during inhalation and exhalation, the post exhalation pause time. the pattern of transition between inhaling and exhaling, the location and timing of expansion in the truck, the range of diaphragmatic movement, and the subjective quality of breathing effort (Gilbert, 2019; Peper, Gilbert, Harvey & Lin, 2015; Nestor, 2020).

Breathing patterns affect sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems (Levin & Swoap, 2019). Inhaling tends to activate the sympathetic nervous system (fight/flight response) while exhaling activates the parasympathetic nervous system (rest and repair response) (Lehrer & Gevirtz, 2014). To observe how breathing affects your heart rate, monitor your pulse from either the radial artery in the wrist or the carotid artery in your neck as shown in Figure 1 and practice the following.

After sensing the baseline rate of your pulse, continue to feel your radial artery pulse in your wrist or at the carotid artery in your neck. Then inhale for the count of four hold for a moment and gently exhale for the count of 5 or 6. Repeat two or three times.

Most people observe that during inhalation, their heart rate increased (sympathetic activation for action) and during exhalation, the heart rate decreases (restoration during safety).

Nearly everyone who is anxious tends to breathe rapidly and shallowly or when stressed, unknowingly gasp or holds their breath–they may even freeze up and blank out (Peper et al, 2016). In addition, many people habitually breathe through their mouth instead of their nose and wake up tired with a dry mouth with bad breath. Mouth breathing combined with chest breathing in the absence of slower diaphragmatic breathing (the lower ribs and abdomen expand during inhalation and constrict during exhalation) is a risk factor for disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome, hypertension, tiredness, anxiety, panic attacks, asthma, dysmenorrhea, epilepsy, cold hands and feet, emphysema, and insomnia. Many of our clients who aware of their dysfunctional breathing patterns and are able to implement effortless breathing report significant reduction in symptoms (Chaitow, Bradley, & Gilbert, 2013; Peper, Mason, Huey, 2017; Peper & Cohen, 2017; Peper, Martinez Aranda, & Moss, 2015).

Breathing is usually overlooked as a first treatment strategy-it is not as glamorous as drugs, surgery or psychotherapy. Teaching breathing takes skill since practitioners needs to be experienced. Namely, they need to be able to demonstrate in action how to breathe effortlessly before teaching it to others. Although it seems unbelievable, a small change in our breathing pattern can have major physical, mental, and emotional effects as can be experienced in the following practice.

Begin by breathing normally and then exhale only 70% of the inhaled air, and inhale normally and again exhale only 70% of the inhaled air. With each exhalation exhale on 70% of the inhaled air. Continue this for 30 seconds. Stop and note how you feel.

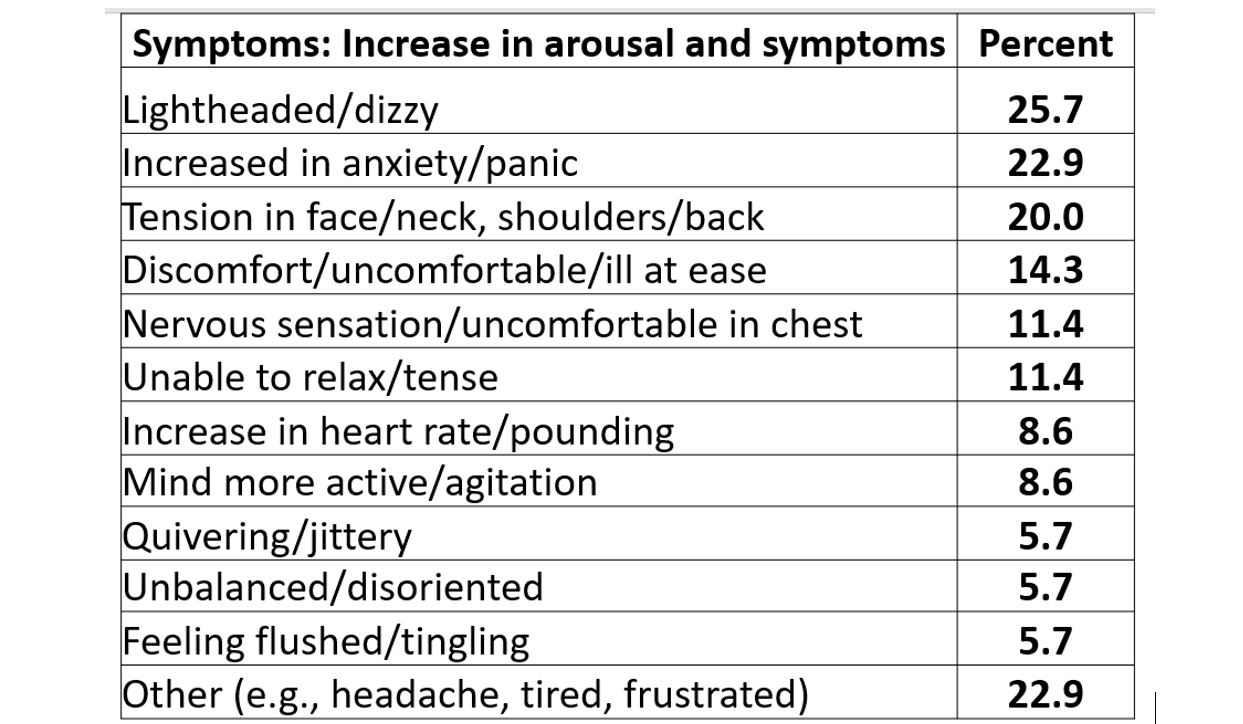

Almost every reports that the 30 seconds feels like a minute and experience some of the following symptoms listed in table 1.

Table 1. Symptoms experienced after 30-45 seconds of sequentially exhaling 70% percent of the inhales air (Peper & MacHose, 1993).

Even though many therapists have long pointed out that breathing is essential, it is usually the forgotten ingredient. It is now being rediscovered in the age of the COVID-19 as respiratory health may reduce the risk of COVID-19.

Simply having very sick patients lie on their side or stomach can improve gas exchange. By lying on your side or prone, breathing is easier as the lung can expand more which appears to reduce the utilization of respirators and intubation (Long & Singh, 2020; Farkas, 2020). This side or prone breathing approach is thousands of years old.

One of the natural and health promoting breathing patterns to promote lung health is to breathe predominantly through the nose. The nose filters, warms, moisturizes and slows the airflow so that airway irritation is reduced. Nasal breathing also increases nitric oxide production that significantly increases oxygen absorption in the body. More importantly for dealing with COVID-19, nitric oxide, produced and released inside the nasal cavities and the lining of the blood vessels, acts as an anti-viral and is a secondary strategy to protect against viral infections (Mehta, Ashkar & Mossman, 2012). During inspiration through the nose, the nitric oxide helps dilate the airways in your lungs and blood vessels (McKeown, 2016).

To increase your health, breathe through your nose, yes, even at night (McKeown, 2020). As you practice this during the day be sure that the lower ribs and abdomen expand during inhalation and decrease in diameter during exhalation. It is breathing without effort although many people will report that it initially feels unnatural. Exhale to the count of about 5 or 6 and inhale (allow the air to flow in) to the count of 4 or 5. Mastering nasal breathing takes practice, practice and practice. See the following for more information.

Watch the Youtube presentation by Patrick McKeown author of the Oxygen Advantage, Practical 40 minute free breathing session with Patrick McKeown to improve respiratory health. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AiwrtgWQeDc&t=680s

Listen to Terry Gross interviewing James Nestor on “How The ‘Lost Art’ Of Breathing Can Impact Sleep And Resilience” on May 27, 2020 on the NPR radio show, Fresh Air.

Look at the Peperperspective blogs that focus on breathing in the age of Covid-19.

Read science writer James Nestor’s book, Breath The new science of a lost art, Breath The new science of a lost art.

References

Allen, R. (2017).The health benefits of nose breathing. Nursing in General Practice.

Christopher, G. (2019). A Guide to Monitoring Respiration. Biofeedback, 47(1), 6-11.

Farkas, J. (2020). PulmCrit – Awake Proning for COVID-19. May 5, 2020.

Long, L. & Singh, S. (2020). COVID-19: Awake Repositioning / Proning. EmDocs

McKeown, P. (2016). Oxygen advantage. New York: William Morrow.

Nestor, James. (2020). Breath The new science of a lost art. New York: Riverhead Books

Can changing your breathing pattern reduce coronavirus exposure?

Posted: April 1, 2020 Filed under: Breathing/respiration, health, relaxation, self-healing, Uncategorized | Tags: coronavirus, COVID-19 9 Comments

This blog is based upon our breathing research that began in the 1990s, This research helped identify dysfunctional breathing patterns that could contribute to illness. We developed coaching/teaching strategies with biofeedback to optimize breathing patterns, improve health and performance (Peper and Tibbetts, 1994; Peper, Martinez Aranda and Moss, 2015; Peper, Mason, and Huey, 2017).

For example, people with asthma were taught to reduce their reactivity to cigarette smoke and other airborne irritants (Peper and Tibbitts, 1992; Peper and Tibbetts, 2003). The smoke of cigarettes or vaping spreads out as the person exhales. If the person was infected, the smoke could represent the cloud of viruses that the other people would inhale as is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Vaping by young people in Riga, Latvia (photo by Erik Peper).

To learn how to breathe differently, the participants first learned effortless slow diaphragmatic breathing. Then were taught that the moment they would become aware of an airborne irritant such as cigarette smoke, they would hold their breath and relax their body and move away from the source of the polluted air while exhaling very slowly through their nose. When the air was clearer they would inhale and continue effortless diaphragmatically breathing (Peper and Tibbetts, 1994). From this research we propose that people may reduce exposure to the coronavirus by changing their breathing pattern; however, the first step is prevention by following the recommended public health guidelines.

- Social distancing (physical distancing while continuing to offer social support)

- Washing your hands with soap for at least 20 seconds

- Not touching your face

- Cleaning surfaces which could have been touched by other such as door bell, door knobs, packages.

- Wear a mask to protect other people and your community. The mask will reduce the shedding of the virus to others by people with COVID-19 or those who are asymptomatic carriers.

Reduce your exposure to the virus when near other people by changing your breathing pattern

Normally when startled or surprised, we tend to gasp and inhale air rapidly. When someone sneezes, coughs or exhales near you, we often respond with a slight gasp and inhale their droplets. To reduce inhaling their droplets (which may contain the coronavirus virus), implement the following:

- When a person is getting too close

- Hold your breath with your mouth closed and relax your shoulders (just pause your breathing) as you move away from the person.

- Gently exhale through your nose (do not inhale before exhaling)-just exhale how little or much air you have

- When far enough away, gently inhale through your nose.

- Remember to relax and feel your shoulders drop when holding your breath. It will last for only a few seconds as you move away from the person. Exhale before inhaling through your nose.

- When a person coughs or sneezes

- Hold your breath, rotate you head away from the person and move away from them while exhaling though your nose.

- If you think the droplets of the sneeze or cough have landed on you or your clothing, go home, disrobe outside your house, and put your clothing into the washing machine. Take a shower and wash yourself with soap.

- When passing a person ahead of you or who is approaching you

- Inhale before they are too close and exhale through your nose as you are passing them.

- After you are more than 6 feet away gently inhale through your nose.

- When talking to people outside

- Stand so that the breeze/wind hits both people from the same side so that the exhaled droplets are blown away from both of you (down wind).

These breathing skills seem so simple; however, in our experience with people with asthma and other symptoms, it took practice, practice, and practice to change their automatic breathing patterns. The new pattern is pause (stop) the breath and then exhale through your nose. Remember, this breathing pattern is not forced and with practice it will occur effortlessly.

The following blogs offer instructions for mastering effortless diaphragmatic breathing.

https://peperperspective.com/2018/10/04/breathing-reduces-acid-reflux-and-dysmenorrhea-discomfort/

https://peperperspective.com/2017/03/19/enjoy-sex-breathe-away-the-pain/

https://peperperspective.com/2015/02/18/reduce-hot-flashes-and-premenstrual-symptoms-with-breathing/

https://peperperspective.com/2015/09/25/resolving-pelvic-floor-pain-a-case-report/

References

Peper, E., Mason, L., Huey, C. (2017). Healing irritable bowel syndrome with diaphragmatic breathing. Biofeedback. (45-4). /

Reduce stress, anxiety and negative thoughts with posture, breathing and reframing

Posted: October 19, 2019 Filed under: behavior, Breathing/respiration, emotions, Exercise/movement, posture, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: Acceptance and comitment therapy, ACT, CBT, cognitive behavior therapy, empowerment, Reframing 10 CommentsWhen locked into a position, options appear less available. By unlocking our body, we allow our brain to unlock and become open to new options.

Changing positions may dissolve the rigidity associated with a fixed position. When we step away from the conflict, take a walk, look up at the treetops, roof lines and clouds, or do something different, we loosen up and new ideas may occur. We may then be able see the conflict from a different point of view that allows resolution.

When stressed, anxious or depressed, it is challenging to change. The negative feelings, thoughts and worries continue to undermine the practice of reframing the experience more positively. Our recent study found that a simple technique, that integrates posture with breathing and reframing, rapidly reduces anxiety, stress, and negative self-talk (Peper, Harvey, Hamiel, 2019).

Thoughts and emotions affect posture and posture affects thoughts and emotions. When stressed or worried (e.g., school performance, job security, family conflict, undefined symptoms, or financial insecurity), our bodies respond to the negative thoughts and emotions by slightly collapsing and shifting into a protective position. When we collapse/slouch, we are much more at risk to:

- Feel helpless (Riskind & Gotay, 1982).

- Feel powerless (Westfeld & Beresford, 1982; Cuddy, 2012).

- Recall and being more captured by negative memories (Peper, Lin, Harvey, & Perez, 2017; Tsai, Peper, & Lin, 2016),

- Experience cognitive difficulty (Peper, Harvey, Mason, & Lin, 2018).

When we are upright and look up, we are more likely to:

- Have more energy (Peper & Lin, 2012).

- Feel stronger (Peper, Booiman, Lin, & Harvey, 2016).

- Find it easier to do cognitive activity (Peper, Harvey, Mason, & Lin, 2018).

- Feel more confident and empowered (Cuddy, 2012).

- Recall more positive autobiographical memories (Michalak, Mischnat,& Teismann, 2014).

Experience how posture affects memory and the feelings (adapted from Alan Alda, 2018)

Stand up and do the following:

- Think of a memory/event when you felt defeated, hurt or powerless and put your body in the posture that you associate with this feeling. Make it as real as possible . Stay with the feeling and associated body posture for 30 seconds. Let go of the memory and posture. Observe what you experienced.

- Think of a memory/event when you felt empowered, positive and happy put your body in the posture that you associate with those feelings. Make it as real as possible. Stay with the feeling and associated body posture for 30 seconds. Let go of the memory and posture. Observe what you experienced.

- Adapt the defeated posture and now recall the positive empowering memory while staying in the defeated posture. Observe what you experience.

- Adapt the empowering posture and now recall the defeated hopeless memory while staying in the empowered posture. Observe what you experience.

Almost all people report that when they adapt the body posture congruent with the emotion that it was much easier to access the memory and feel the emotion. On the other hand when they adapt the body posture that was the opposite to the emotions, then it was almost impossible to experience the emotions. For many people, when they adapted the empowering posture, they could not access the defeated hopeless memory. If they did access that memory, they were more likely be an observer and not be involved or emotionally captured by the negative memory.

Comparison of Posture with breathing and reframing to Reframing

The study investigated whether changing internal dialogue (reframing) or combining posture change and breathing with changing internal dialogue would reduce stress and negative self-talk more effectively.

The participants were 145 college students (90 women and 55 men) average age 25.0 who participated as part of a curricular practice in four different classes.

After the students completed an anonymous informational questionnaire (history of depression, anxiety, blanking out on exams, worrying, slouching), the classes were divided into two groups. They were then asked to do the following:

- Think of a stressful conflict or problem and make it as real as possible for one minute. Then let go of the stressful memory and do one of the two following practices.

- Practice A: Reframe the experience positively for 20 seconds.

- Practice B: Sit upright, look up, take a breath and reframe the experience positively for 20 seconds.

- After doing practice A or practice B, rate the extent to which your negative thoughts and anxiety/tension were reduced, from 0 (not at all) to 10 (totally).

- Now repeat this exercise except switch and do the other practice. (Namely, if you did A now you do B; if you did B now you do A).

RESULTS

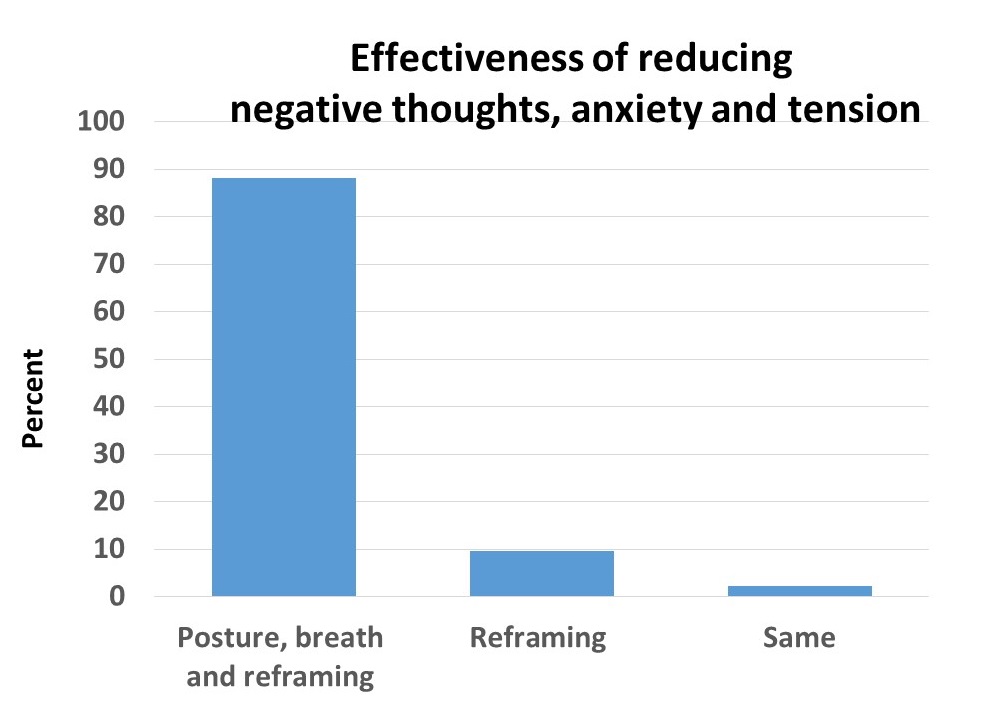

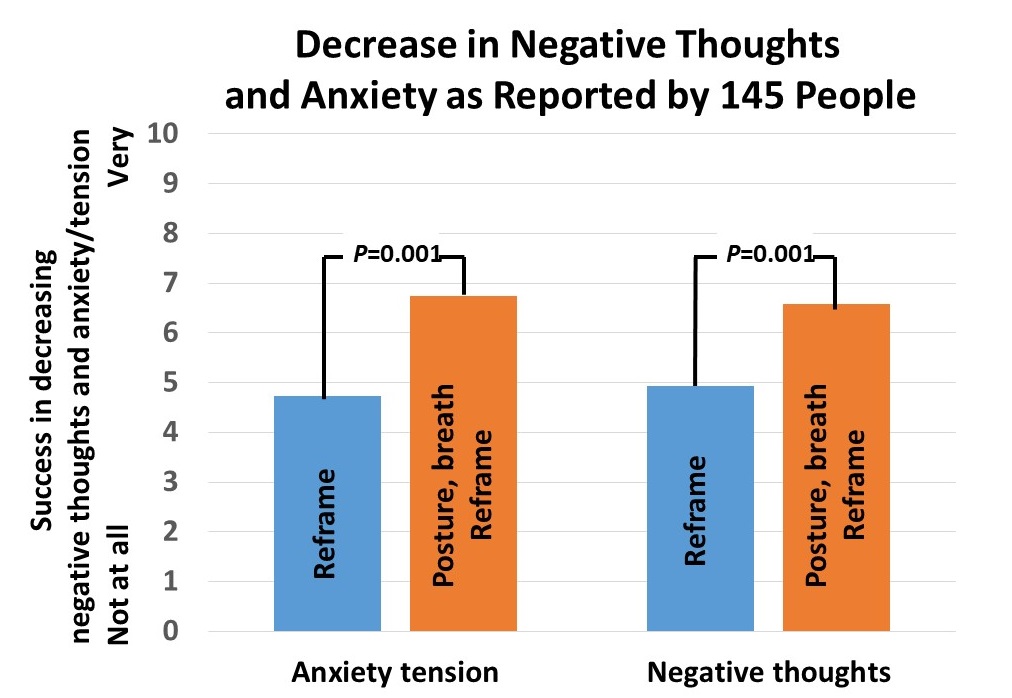

Overwhelmingly students reported that sitting erect, breathing and reframing positively was much more effective than only reframing as shown in Figure 1 and 2.

Figure 1. Percentage of students rating posture, breath and reframing practice (PBRP) as more effective than reframing practice (RP) in reducing negative thoughts, anxiety and stress. Figure 2. Self-rating of reduction of negative thoughts and anxiety/tension

Figure 2. Self-rating of reduction of negative thoughts and anxiety/tension

Stop reading. Do the practice yourself. It is only through experience that you know whether posture with breathing and reframing is a more beneficial than simply reframing the language.

Implications for education, counseling, psychotherapy.

Our findings have implications for education, counseling and psychotherapy because students and clients usually sit in a slouched position in classrooms and therapeutic settings. By shifting the body position to an erect upright position, taking a breath and then reframing, people are much more successful in reducing their negative thoughts and anxiety/stress. They report feeling much more optimistic and better able to cope with felt stress as shown by representative comments in table 1.

| Reframing | Posture, breath and reframing |

| After changing my internal language, I still strongly felt the same thoughts. | I instantly felt better about my situation after adjusting my posture. |

| I felt a slight boost in positivity and optimism. The negative feelings (anxiety) from the negative thoughts also diminished slightly. | The effects were much stronger and it was not isolated mentally. I felt more relief in my body as well. |

| Even after changing my language, I still felt more anxious. | Before changing my posture and breathing, I felt tense and worried. After I felt more relaxed. |

| I began to lift my mood up; however, it didn’t really improve my mood. I still felt a bit bad afterwards and the thoughts still stayed. | I began to look from the floor and up towards the board. I felt more open, understanding and loving. I did not allow myself to get let down. |

| During the practice, it helped calm me down a bit, but it wasn’t enough to make me feel satisfied or content, it felt temporary. | My body felt relaxed overall, which then made me feel a lot better about the situation. |

| Difficult time changing language. | My posture and breathing helped, making it easier to change my language. |

| I felt anger and stayed in my position. My body stayed tensed and I kept thinking about the situation. | I felt anger but once I sat up straight and thought about breathing, my body felt relaxed. |

| Felt like a tug of war with my thoughts. I was able to think more positively but it took a lot more brain power to do so. | Relaxed, extended spine, clarity, blank state of mind. |

Table 1. Some representative comments of practicing reframing or posture, breath and reframing.

The results of our study in the classroom setting are not surprising. Many us know to take three breaths before answering questions, pause and reflect before responding, take time to cool down before replying in anger, or wait till the next day before you hit return on your impulsive email response.

Currently, counseling, psychotherapy, psychiatry and education tend not to incorporate body posture as a potential therapeutic or educational intervention for teaching participants to control their mood or reduce feelings of powerlessness. Instead, clients and students often sit slightly collapsed in a chair during therapy or in class. On the other hand, if individuals were encouraged to adopt an upright posture especially in the face of stressful circumstances it would help them maintain their self-esteem, reduce negative mood, and use fewer sadness words as compared to the individual in a slumped and seated posture (Nair, Sagar, Sollers, Consedine, & Broadbent, 2015).

THE VALUE OF SELF-EXPERIENCE

What makes this study valuable is that participants compare for themselves the effects of the two different interventions techniques to reduce anxiety, stress and negative thoughts. Thus, the participants have an opportunity to discover which strategy is more effective instead of being told what to do. The demonstration is even more impressive when done in groups because nearly all participants will report that changing posture with breathing and reframing is more beneficial.

This simple and quick technique can be integrated in counseling and psychotherapy by teaching clients this behavioral technique to reduce stress. In Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), sitting upright can help the individual replace a thought with a more reasonable one. In third wave CBT, it can help bypass the negative content of the original language and create a metacognitive change, such as, “I will not let this thought control me.”

It can also help in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) since changing one’s body posture may facilitate the process of “acceptance” (Hayes, Pistorello, & Levin, 2012). Adopting an upright sitting position and taking a breath is like saying “I am here, I am present, I am not escaping or avoiding.” This change in body position represents movement from inside to outside, movement from accepting the unpleasant emotion related to the negative thoughts toward a “commitment” to moving ahead, contrary to the automatic tendency to follow the negative thought. The positive reframing during body position or posture change is not an attempt to color reality in pretty colors, but rather a change of awareness, perspective, and focus that helps the individual identify and see some new options for moving ahead toward commitment according to one’s values. This intentional change in direction is central in ACT and also in positive psychology (Stichter, 2018).

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

We suggest that therapists, educators, clients and students get up out of their chairs and incorporate body movements when they feels overwhelmed and stuck. Finally, this study points out that mind and body are affected by each other. It provides another example of the psychophysiological principle enunciated by Elmer Green (1999, p 368):

“Every change in the physiological state is accompanied by an appropriate change in the mental-emotional state, conscious or unconscious; and conversely, every change in the mental-emotional state, conscious or unconscious is accompanied by an appropriate change in the physiological state.”

The findings of this study echo the ancient spiritual wisdom that is is central to the teaching of the Zen Master, Thich Nhat Hanh. He recommends that his students recite the following at any time:

Breathing in I calm my body,

Breathing out I smile,

Dwelling in the present moment,

I know it is a wonderful moment.

References

Cuddy, A. (2012). Your body language shapes who you are. Technology, Entertainment, and Design (TED) Talk, available at: www.ted.com/talks/amy_cuddy_your_body_language_shapes_who_you_are

Green, E. (1999). Beyond psychophysics, Subtle Energies & Energy Medicine, 10(4), page 368.

Peper, E., Booiman, A., Lin, I.M., & Harvey, R. (2016). Increase strength and mood with posture. Biofeedback. 44(2), 66–72.

Toning quiets the mind and increases HRV more quickly than mindfulness practice

Posted: September 21, 2019 Filed under: behavior, Breathing/respiration, emotions, health, mindfulness, Pain/discomfort, relaxation, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: heart rate variability, intrusive thoughts, meditation, rumination 6 CommentsDisruptive thoughts, ruminations and worrying are common experiences especially when stressed. Numerous clinical strategies such as cognitive behavioral therapy attempt to teach clients to reduce negative ruminations (Kopelman-Rubin, Omer, & Dar, 2017). Over the last ten years, many people and therapists practice meditative techniques to let go and not be captured by negative ruminations, thoughts, and emotions. However, many people continue to struggle with distracting and wandering thoughts.

Just think back when you’re upset, hurt, angry or frustrated. Attempting just to observe without judgment can be very, very challenging as the mind keeps rehearsing and focusing on what happened. Telling yourself to stop being upset often doesn’t work because your mind is focused on how upset you are. If you can focus on something else or perform physical activity, the thoughts and feelings often subside.

Over the last fifteen years, mindfulness meditation has been integrated and adapted for use in behavioral medicine and psychology (Peper, Harvey, & Lin, 2019). It has also been implemented during bio- and neurofeedback training (Khazan, 2013; Khazan, 2019). Part of the mindfulness instruction is to recognize the thoughts without judging or becoming experientially “fused” with them. A process referred to as “meta-awareness” (Dahl, Lutz, & Davidson, 2015). Mindfulness training combined with bio- and neurofeedback training can improve a wide range of psychological and physical health conditions associated with symptoms of stress, such as anxiety, depression, chronic pain, and addiction (Creswell, 2015, Khazan, 2019).

Mindfulness is an effective technique; however, it may not be more effective than other self-regulations strategies (Peper et al, 2019). Letting go of worrying thoughts and rumination is even more challenging when one is upset, angry, or captured by stressful life circumstances. Is it possible that other strategies beside mindfulness may more rapidly reduce wandering and intrusive thoughts? In 2015, researchers van der Zwan, de Vente, Huiznik, Bogels, & de Bruin found that physical activity, mindfulness meditation and heart rate variability biofeedback were equally effective in reducing stress and its related symptoms when practiced for five weeks.

Our research explored whether other techniques from the ancient wisdom traditions could provide participants tools to reduce rumination and worry. We investigated the physiological effects and subject experiences of mindfulness and toning. Toning is vocalizing long and sustained sounds as a form of mediation. (Watch the video the toning demonstration by sound healer and musician, Madhu Anziani at the end of the blog.)

COMPARING TONING AND MINDFULNESS

The participants were 91 undergraduate college students (35 males, 51 females and 5 unspecified; average age, 22.4 years, (SD = 3.5 years).

After sitting comfortably in class, each student practiced either mindfulness or toning for three minutes each. After each practice, the students rated the extent of mind wandering, occurrence of intrusive thoughts and sensations of vibration on a scale from 0 (not all) to 10 (all the time). They also rated pre and post changes in peacefulness, relaxation, stress, warmth, anxiety and depression. After completing the assessment, they practice the other practice and after three minutes repeated the assessment.

The physiological changes that may occur during mindfulness practice and toning practice was recorded in a separate study with 11 undergraduate students (4 males, 7 females; average age 21.4 years. Heart rate and respiration were monitored with ProComp Infiniti™ system (Thought Technology, Ltd., Montreal, Canada). Respiration was monitored from the abdomen and upper thorax with strain gauges and heartrate was monitored with a blood volume pulse sensor placed on the thumb.

After the sensors were attached, the participants faced away from the screen so they did not receive feedback. They then followed the same procedure as described earlier, with three minutes of mindfulness, or toning practice, counterbalanced. After each condition, they completed a subjective assessment form rating experiences as described above.

RESULTS: SUBJECTIVE FINDINGS

Toning was much more successful in reducing mind wandering and intrusive thoughts than mindfulness. Toning also significantly increased awareness of body vibration as compared to mindfulness as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Differences between mindfulness and toning practice.

There was no significant difference between toning and mindfulness in the increased self-report of peacefulness, warmth, relaxation, and decreased self-report of anxiety and depression as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. No significant difference between toning and mindfulness practice in relaxation or stress reports.

RESULTS: PHYSIOLOGICAL FINDINGS

Respiration rate was significantly lower during toning (4.6 br/min) as compared to mindfulness practice (11.6 br/min); heart rate standard deviation (SDNN) was much higher during toning condition (11.6) (SDNN 103.7 ms) than mindfulness (6.4) (SDNN 61.9 ms). Two representative physiological recording are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Representative recordings of breathing and heart rate during mindfulness and toning practice. During toning the respiration rate (chest and abdomen) was much slower than during mindfulness and baseline conditions. Also, during toning heart rate variability was much larger than during mindfulness or baseline conditions.

DISCUSSION

Toning practice is a useful strategy to reduce mind wandering as well as inhibit intrusive thoughts and increase heart rate variability (HRV). Most likely toning uses the same neurological pathways as self-talk and thus inhibits the negative and hopeless thoughts. Toning is a useful meditation alternative because it instructs people to make a sound that vibrates in their body and thus they attend to the sound and not to their thoughts.

Physiologically, toning immediately changed the respiration rate to less than 6 breaths per minute and increases heart rate variability. This increase in heart rate variability occurs without awareness or striving. We recommend that toning is integrated as a strategy to complement bio-neurofeedback protocols. It may be a useful approach to enhance biofeedback-assisted HRV training since toning increases HRV without trying and it may be used as an alternative to mindfulness, or used in tandem for maximum effectiveness.

TAKE HOME MESSAGE

1) When people report feeling worried and anxious and have difficulty interrupting ruminations that they first practice toning before beginning mindfulness meditation or bio-neurofeedback training.

2) When training participants to increase heart rate variability, toning could be a powerful technique to increase HRV without striving

TONING DEMONSTRATION AND INSTRUCTION BY SOUND HEALER MADHU ANZIANI

For the published article see: Peper, E., Pollack, W., Harvey, R., Yoshino, A., Daubenmier, J. & Anziani, M. (2019). Which quiets the mind more quickly and increases HRV: Toning or mindfulness? NeuroRegulation, 6(3), 128-133.

REFERENCES

Creswell, J. D. (2015). Mindfulness Interventions. Annual Review of Psychology, 68, 491-516.

van der Zwan, J. E., de Vente, W., Huizink, A. C., Bogels, S. M., & de Bruin, E. I. (2015). Physical activity, mindfulness meditation, or heart rate variability biofeedback for stress reduction: A randomized controlled trial. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 40(4), 257-268. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-015-9293-x