Reduce anxiety

Posted: March 23, 2022 Filed under: behavior, Breathing/respiration, CBT, cognitive behavior therapy, digital devices, education, emotions, health, mindfulness, posture, relaxation, self-healing, stress management | Tags: anxiety, concentration, insomnia, menstrual cramps, pain 3 Comments

The purpose of this blog is to describe how a university class that incorporated structured self-experience practices reduced self-reported anxiety symptoms (Peper, Harvey, Cuellar, & Membrila, 2022). This approach is different from a clinical treatment approach as it focused on empowerment and mastery learning (Peper, Miceli, & Harvey, 2016).

As a result of my practice, I felt my anxiety and my menstrual cramps decrease. — College senior

When I changed back to slower diaphragmatic breathin, I was more aware of my negative emotions and I was able to reduce the stress and anxiety I was feeling with the deep diaphragmatic breathing.– College junior

Background

More than half of college students now report anxiety (Coakley et al., 2021). In our recent survey during the first day of the spring semester class, 59% of the students reported feeling tired, dreading their day, being distracted, lacking mental clarity and had difficulty concentrating.

Before the COVID pandemic nearly one-third of students had or developed moderate or severe anxiety or depression while being at college (Adams et al., 2021. The pandemic accelerated a trend of increasing anxiety that was already occurring. “The prevalence of major depressive disorder among graduate and professional students is two times higher in 2020 compared to 2019 and the prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder is 1.5 times higher than in 2019” As reported by Chirikov et al (2020) from the UC Berkeley SERU Consortium Reports.

This increase in anxiety has both short and long term performance and health consequences. Severe anxiety reduces cognitive functioning and is a risk factor for early dementia (Bierman et al., 2005; Richmond-Rakerd et al, 2022). It also increases the risk for asthma, arthritis, back/neck problems, chronic headache, diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, pain, obesity and ulcer (Bhattacharya et al., 2014; Kang et al, 2017).

The most commonly used treatment for anxiety are pharmaceutical and cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) (Kaczkurkin & Foa, 2015). The anti-anxiety drugs are usually benzodiazepines (e.g., alprazolam (Xanax), clonazepam (Klonopin), chlordiazepoxide (Librium), diazepam (Valium) and lorazepam (Ativan). Although these drugs they may reduce anxiety, they have numerous side effects such as drowsiness, irritability, dizziness, memory and attention problems, and physical dependence (Shri, 2012; Crane, 2013).

Cognitive behavior therapy techniques based upon the assumption that anxiety is primarily a disorder in thinking which then causes the symptoms and behaviors associated with anxiety. Thus, the primary treatment intervention focuses on changing thoughts.

Given the significant increase in anxiety and the potential long term negative health risks, there is need to provide educational strategies to empower students to prevent and reduce their anxiety. A holistic approach is one that assumes that body and mind are one and that soma/body, emotions and thoughts interchangeably affect the development of anxiety. Initially in our research, Peper, Lin, Harvey & Perez (2017) reported that it was easier to access hopeless, helpless, powerless and defeated memories in a slouched position than an upright position and it was easier to access empowering positive memories in an upright position than a slouched position. Our research on transforming hopeless, helpless, depressive thought to empowering thoughts, Peper, Harvey & Hamiel (2019) found that it was much more effective if the person first shifts to an upright posture, then begins slow diaphragmatic breathing and finally reframes their negative to empowering/positive thoughts. Participants were able to reframe stressful memories much more easily when in an upright posture compared to a slouched posture and reported a significant reduction in negative thoughts, anxiety (they also reported a significant decrease in negative thoughts, anxiety and tension as compared to those attempting to just change their thoughts).

The strategies to reduce anxiety focus on breathing and posture change. At the same time there are many other factors that may contribute the onset or maintenance of anxiety such as social isolation, economic insecurity, etc. In addition, low glucose levels can increase irritability and may lower the threshold of experiencing anxiety or impulsive behavior (Barr, Peper, & Swatzyna, 2019; Brad et al, 2014). This is often labeled as being “hangry” (MacCormack & Lindquist, 2019). Thus, by changing a high glycemic diet to a low glycemic diet may reduce the somatic discomfort (which can be interpreted as anxiety) triggered by low glucose levels. In addition, people are also sitting more and more in front of screens. In this position, they tend to breathe quicker and more shallowly in their chest.

Shallow rapid breathing tends to reduce pCO2 and contributes to subclinical hyperventilation which could be experienced as anxiety (Lum, 1981; Wilhelm et al., 2001; Du Pasquier et al, 2020). Experimentally, the feeling of anxiety can rapidly be evoked by instructing a person to sequentially exhale about 70 % of the inhaled air continuously for 30 seconds. After 30 seconds, most participants reported a significant increase in anxiety (Peper & MacHose, 1993). Thus, the combination of sitting, shallow breathing and increased stress from the pandemic are all cofactors that may contribute to the self-reported increase in anxiety.

To reduce anxiety and discomfort, McGrady and Moss (2013) suggested that self-regulation and stress management approaches be offered as the initial treatment/teaching strategy in health care instead of medication. One of the useful approaches to reduce sympathetic arousal and optimize health is breathing awareness and retraining (Gilbert, 2003).

Stress management as part of a university holistic health class

Every semester since 1976, up to 180 undergraduates have enrolled in a three-unit Holistic Health class on stress management and self-healing (Klein & Peper, 2013). Students in the class are assigned self-healing projects using techniques that focus on awareness of stress, dynamic regeneration, stress reduction imagery for healing, and other behavioral change techniques adapted from the book, Make Health Happen (Peper, Gibney & Holt, 2002).

82% of students self-reported that they were ‘mostly successful’ in achieving their self-healing goals. Students have consistently reported achieving positive benefits such as increasing physical fitness, changing diets, reducing depression, anxiety, and pain, eliminating eczema, and even reducing substance abuse (Peper et al., 2003; Bier et al., 2005; Peper et al., 2014).

This assessment reports how students’ anxiety decreased after five weeks of daily practice. The students filled out an anonymous survey in which they rated the change in their discomfort after practicing effortless diaphragmatic breathing. More than 70% of the students reported a decrease in anxiety. In addition, they reported decreases in symptoms of stress, neck and shoulder pain as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Self-report of decrease in symptoms after practice diaphragmatic breathing for a week.

In comparing the self-reported responses of the students in the holistic health class to those of the control group (N=12), the students in the holistic health class reported a significant decrease in symptoms since the beginning of the semester as compared to the control group as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Change in self-reported symptoms after 6 weeks of practice the integrated holistic health skills as compared to the control group who did not practice these skills.

Changes in symptoms Most students also reported an increase in mental clarity and concentration that improved their study habits. As one student noted: Now that I breathe properly, I have less mental fog and feel less overwhelmed and more relaxed. My shoulders don’t feel tense, and my muscles are not as achy at the end of the day.

The teaching components for the first five weeks included a focus on the psychobiology of stress, the role of posture, and psychophysiology of respiration. The class included didactic presentations and daily self-practice

Lecture content

- Diadactic presentation on the physiology of stress and how posture impacts health.

- Self-observation of stress reactions; energy drain/energy gain and learning dynamic relaxation.

- Short experiential practices so that the student can experience how slouched posture allows easier access to helpless, hopeless, powerless and defeated memories.

- Short experiential breathing practices to show how breathing holding occurs and how 70% exhalation within 30 seconds increases anxiety.

- Didactic presentation on the physiology of breathing and how a constricted waist tends to have the person breathe high in their chest (the cause of neurasthemia) and how the fight/flight response triggers chest breathing, breath holding and/or shallow breathing.

- Explanation and practice of diaphragmatic breathing.

Daily self-practice

Students were assigned weekly daily self-practices which included both skill mastery by practicing for 20 minutes as well and implementing the skill during their daily life. They then recorded their experiences after the practice. At the end of the week, they reviewed their own log of week and summarized their observations (benefits, difficulties) and then met in small groups to discuss their experiences and extract common themes. These daily practices consisted of:

- Awareness of stress. Monitoring how they reacted to daily stressor

- Practicing dynamic relaxation. Students practiced for 20 minutes a modified progressive relaxation exercise and observed and inhibit bracing pattern

- Changing energy drain and energy gains. Students observed what events reduced or increased their subjective energy and implemented changes in their behavior to decrease events that reduced their energy and increased behaviors that increase their enery

- Creating a memory of wholeness practice

- Practicing effortless breathing. Students practiced slowly diaphragmatic abdominal breathing for 20 minutes per day and each time they become aware of dysfunctional breathing (breath holding, shallow chest breathing, gasping) during the day, they would shift to slower diaphragmatic breathing.

Discussion

Almost all students were surprised how beneficial these practices were to reduce their anxiety and symptoms. Generally, the more the students would interrupt their personal stress responses during the day by shifting to diaphragmatic breathing the more did they experience success. We hypothesize that some of the following factors contributed to the students’ improvement.

- Learning through self-mastery as an education approach versus clinical treatment.

- Generalizing the skills into daily life and activities. Practicing the skills during the day in which the cue of a stress reaction triggered the person to breathe slowly. The breathing would reduce the sympathetic activation.

- Interrupting escalating sympathetic arousal. Responding with an intervention reduced the sense of being overwhelmed and unable to cope by the participant by taking charge and performing an active task.

- Redirecting attention and thoughts away from the anxiety triggers to a positive task.

- Increasing heart rate variability. Through slow breathing heart rate variability increased which enhanced sympathetic parasympathetic balance.

- Reducing subclinical hyperventilation by breathing slower and thereby increasing pC02.

- Increasing social support by meeting in small groups. The class discussion group normalized the anxiety experiences.

- Providing hope. The class lectures, assigned readings and videos provide hope; since, it included reports how other students had reversed their chronic disorders such as irritable bowel disease, acid reflux, psoriasis with behavioral interventions.

Although the study lacked a control group and is only based upon self-report, it offers an economical non-pharmaceutical approach to reduce anxiety. These stress management strategies may not resolve anxiety for everyone. Nevertheless, we recommend that schools implement this approach as the first education intervention to improve health in which students are taught about stress management, learn and practice relaxation and diaphragmatic breathing and then practice these skills during the day whenever they experience stress or dysfunctional breathing.

I noticed that breathing helped tremendously with my anxiety. I was able to feel okay without having that dreadful feeling stay in my chest and I felt it escape in my exhales. I also felt that I was able to breathe deeper and relax better altogether. It was therapeutic, I felt more present, aware, and energized.

See the following blogs for detailed breathing instructions

References

Adams. K.L., Saunders KE, Keown-Stoneman CDG, et al. (2021). Mental health trajectories in undergraduate students over the first year of university: a longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open 2021; 11:e047393. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047393

Barr, E. A., Peper, E. & Swatzyna, R.J. (2019). Slouched Posture, Sleep Deprivation, and Mood Disorders: Interconnection and Modulation by Theta Brain Waves. Neuroregulation, 6(4), 181–189 https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.6.41.181

Bhattacharya, R., Shen, C. & Sambamoorthi, U. (2014). Excess risk of chronic physical conditions associated with depression and anxiety. BMC Psychiatry 14, 10 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-10

Bier, M., Peper, E., & Burke, A. (2005). Integrated stress management with ‘Make Health Happen: Measuring the impact through a 5-month follow-up. Poster presentation at the 36th Annual Meeting of the Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. Abstract published in: Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 30(4), 400. https://biofeedbackhealth.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/2005-aapb-make-health-happen-bier-peper-burke-gibney3-12-05-rev.pdf

Bierman, E.J.M., Comijs, H.C. , Jonker, C. & Beekman, A.T.F. (2005). Effects of Anxiety Versus Depression on Cognition in Later Life. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry,13(8), 686-693, https://doi.org/10.1097/00019442-200508000-00007.

Brad, J., Bushman, C., DeWall, N., Pond, R.S., &. Hanus, M.D. (2014).. Low glucose relates to greater aggression in married couples. PNAS, April 14, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1400619111

Chirikov, I., Soria, K. M, Horgos, B., & Jones-White, D. (2020). Undergraduate and Graduate Students’ Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic. UC Berkeley: Center for Studies in Higher Education. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/80k5d5hw

Coakley, K.E., Le, H., Silva, S.R. et al. Anxiety is associated with appetitive traits in university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nutr J 20, 45 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-021-00701-9

Crane,E.H. (2013).Highlights of the 2011 Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) Findings on Drug-Related Emergency Department Visits. 2013 Feb 22. In: The CBHSQ Report. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); 2013-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK384680/

Du Pasquier, D., Fellrath, J.M., & Sauty, A. (2020). Hyperventilation syndrome and dysfunctional breathing: update. Revue Medicale Suisse, 16(698), 1243-1249. https://europepmc.org/article/med/32558453

Gilbert C. Clinical Applications of Breathing Regulation: Beyond Anxiety Management. Behavior Modification. 2003;27(5):692-709. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445503256322

Kaczkurkin, A.N. & Foa, E.B. (2015). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders: an update on the empirical evidence. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 17(3):337-46. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2015.17.3/akaczkurkin

Kang, H. J., Bae, K. Y., Kim, S. W., Shin, H. Y., Shin, I. S., Yoon, J. S., & Kim, J. M. (2017). Impact of Anxiety and Depression on Physical Health Condition and Disability in an Elderly Korean Population. Psychiatry investigation, 14(3), 240–248. https://doi.org/10.4306/pi.2017.14.3.240

Klein, A. & Peper, W. (2013). There is Hope: Autogenic Biofeedback Training for the Treatment of Psoriasis. Biofeedback, 41(4), 194–201. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-41.4.01

Lum, L. C. (1981). Hyperventilation and anxiety state. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 74(1), 1-4. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/014107688107400101

MacCormack, J. K., & Lindquist, K. A. (2019). Feeling hangry? When hunger is conceptualized as emotion. Emotion, 19(2), 301–319. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000422

McGrady, A. & Moss, D. (2013). Pathways to illness, pathways to health. New York: Springer. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-1-4419-1379-1

Peper, E., Gibney, K.H., & Holt, C.F. (2002). Make health happen: Training yourself to create wellness. Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company. https://he.kendallhunt.com/make-health-happen

Peper, E., Harvey, R., Cuellar, Y., & Membrila, C. (2022). Reduce anxiety. NeuroRegulation, 9(2), 91–97. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.9.2.91 https://www.neuroregulation.org/article/view/22815/14575

Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Hamiel, D. (2019). Transforming thoughts with postural awareness to increase therapeutic and teaching efficacy. NeuroRegulation, 6(3),153-169. doi:10.15540/nr.6.3.1533-1 https://www.neuroregulation.org/article/view/19455/13261

Peper, E., Lin, I-M., Harvey, R., & Perez, J. (2017). How posture affects memory recall and mood. Biofeedback.45 (2), 36-41. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-45.2.01

Peper, E., Lin, I-M, Harvey, R., Gilbert, M., Gubbala, P., Ratkovich, A., & Fletcher, F. (2014). Transforming chained behaviors: Case studies of overcoming smoking, eczema and hair pulling (trichotillomania). Biofeedback, 42(4), 154-160. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-42.4.06

Peper, E., MacHose, M. (1993). Symptom prescription: Inducing anxiety by 70% exhalation. Biofeedback and Self-Regulation 18, 133–139). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00999790

Peper, E., Miceli, B., & Harvey, R. (2016). Educational Model for Self-healing: Eliminating a Chronic Migraine with Electromyography, Autogenic Training, Posture, and Mindfulness. Biofeedback, 44(3), 130–137. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-44.3.03

Peper, E., Sato-Perry, K & Gibney, K. H. (2003). Achieving Health: A 14-Session Structured Stress Management Program—Eczema as a Case Illustration. 34rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. Abstract in: Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 28(4), 308. Proceeding in: http://www.aapb.org/membersonly/articles/P39peper.pdf

Richmond-Rakerd, L.S., D’Souza, S, Milne, B.J, Caspi, A., & Moffitt, T.E. (2022). Longitudinal Associations of Mental Disorders with Dementia: 30-Year Analysis of 1.7 Million New Zealand Citizens. JAMA Psychiatry. Published online February 16, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.4377

Shri, R. (2012). Anxiety: Causes and Management. The Journal of Behavioral Science, 5(1), 100–118. Retrieved from https://so06.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/IJBS/article/view/2205

Wilhelm, F.H., Gevirtz, R., & Roth, W.T. (2001). Respiratory dysregulation in anxiety, functional cardiac, and pain disorders. Assessment, phenomenology, and treatment. Behav Modif, 25(4), 513-45. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445501254003

When you have pain-Listen to this first!

Posted: February 20, 2022 Filed under: behavior, CBT, cognitive behavior therapy, emotions, healing, health, Pain/discomfort, self-healing 2 Comments

Pain is so different for each person. It can range from mildly distracting to totally debilitating. It can be the result from a medical procedure (post- surgical pain), a traumatic injury, disease, trauma or unknown causes. It is challenging to know what to do to reduce suffering and improve health and functioning. Should I take narcotics, have surgery, see a pain psychologist, have acupuncture, receive physical therapy, use biofeedback, change my diet, or get a massage? Should I exercise or rest? Should I follow my doctor’s recommendations?

Before you do anything, first listen to this podcast by pain psychologist, Rachel Zoffness, PhD. In this podcast she will explain what pain is; how it works; and how thoughts, emotions, and sensations are always interconnected. You will also learn the fundamentals of treating chronic pain and helping patients living with it. As one of my close friends stated, “I only wished I could have listened to this before, it would have saved years of suffering.” The podcast is Ologies with Alie Ward and the episode is Dolorology. The link for the episode is:

https://www.alieward.com/ologies/dolorology

Rachel Zoffness, PhD, a pain psychologist, Visiting Professor at Stanford, and Assistant Clinical Professor at the UCSF School of Medicine. She serves on the Board of Directors of the U.S. Association for the Study of Pain, and the Society of Pediatric Pain Medicine. She is the author of The Pain Management Workbook and The Chronic Pain and Illness Workbook for Teens. She is a 2021 Mayday Fellow and consults on the development of integrative pain programs around the world.

Resolving a chronic headache with posture feedback and breathing

Posted: January 4, 2022 Filed under: behavior, Breathing/respiration, computer, digital devices, ergonomics, health, laptops, Neck and shoulder discomfort, Pain/discomfort, posture, relaxation, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: Desktop feedback app, headache, migraine 37 Comments| Adapted from Peper, E., Covell, A., & Matzembacker, N. (2021). How a chronic headache condition became resolved with one session of breathing and posture coaching. NeuroRegulation, 8(4), 194–197. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.8.4.194 |

This blog describes the process by which a 32 year old woman student’s chronic headaches that she had since age eighteen was resolved in a single coaching session. The student suffered two or three headache per week a week which initially began when she was eighteen after using digital devices and encouraged her to slouch as she looked down. Although she describes herself as healthy, she reported having high level of anxiety and occasional depression. She self-medicated with 2 to 10 Excedrin tablets a week. It is possible that the chronic headaches could partially be triggered by caffeine withdrawal which get resolved by taking more Excedrins (Greben et al., 1980) since Excedrin contains 65 mg of caffeine as well as 250 mg of Acetaminophen which can be harmful to liver function (Bauer et al., 2021).

The behavioral coaching intervention

During the first day in class, the student approached the instructor and she shared that she had a severe headache. During their conversation, the instructor noticed that she was breathing in her chest without abdominal movement, her shoulders were held tight, her posture slightly slouched and her hands were cold. As she was unaware of her body responses, the instructor offered to guide her through some practices that may be useful to reduce her headache. The same strategies could also be useful for the other students in the class; since, headaches, anxiety, zoom fatigue, neck and shoulder tension, abdominal discomfort, and vision problems are common and have increased as people spent more time in front of screens (Charles et al., 2021; Ahmed et al., 2021; Bauer, 2021; Kuehn, 2021; Peper et al., 2021 ).

These symptoms may occur because of bad posture, neck and shoulder tension, shallow chest breathing, stress and social isolation (Elizagaray-Garcia et al., 2020; Schulman, 2002). When people become aware of their dysfunctional somatic patterns and change their posture, breathing pattern, internal language and implement stress management techniques, they often report a reduction in symptoms such as irritable bowel syndrome, acid reflux, neck and shoulder tension, or anxiety (Peper et al, 2017a; Peper et al, 2016a). Sometimes, a single coaching session can be sufficient to improve health.

Working hypothesis: The headaches were most likely tension headaches and not migraines and may be the result of chronic neck and shoulder tension which was maintained during chest breathing and the slouched head forward body posture. If she could change her posture, relax her neck and shoulders, and breathe diaphragmatically so that the lower abdomen widen during inhalation, most likely her shoulder and neck tension would decrease. Therefore, by changing posture from a slouched to upright position combined with slower diaphragmatic breathing, the muscle tension would be reduced and the headaches would decrease.

Breathing and posture changes

She was encouraged to sit upright so that the abdomen had space to expand (Peper et al., 2020). In addition, she needed to loosen the clothing around her waist to provide room for her abdomen to expand during inhalation instead of her chest lifting (MacHose & Peper, 1991). Allowing abdominal expansion can be challenging for many paticipants since they are self-conscious about their body image, as well holding their stomach in as an unconscious learned response to avoid pain after having had abdominal surgery, or as an automatic protective response to threat (Peper et al., 2015). The upright position also allowed her to sit tall and erect in which the back of head reaches upward towards the ceiling while relaxing and feeling gravity pulling her shoulders downward and at the same time relaxing her hips and legs.

With guided verbal and tactile coaching, she learned to master slower diaphragmatic breathing in which she gently and slowly exhaled by making a sound of pssssssst (exhaling through pursed lips) which tends to activate the transverse and oblique abdominal muscles and slightly tighten the pelvic floor muscles so that her lower abdomen would slightly constrict at the end of the exhalation (Peper et al., 2016). Then, by allowing the lower abdomen and pelvic floor relax so that the abdomen could expand in 360 degrees, inhalation occurred.

While practicing the slower breathing in this relaxed upright position, she was instructed to sense/imagine feeling a flow of down and through her arms and out her hands as she exhaled (as if the air could flow through straws down her arms). After a few minutes, she felt her headache decrease and noticed that her hands had warmed. After this short coaching intervention, she went back to her seat in class and continued to practice the relaxed effortless breathing while sitting upright and allowing her shoulders to melt downward.

The use of muscle feedback to demonstrate residual covert muscle tension

During class session, she volunteered to have her trapezius muscle monitored with electromyography (EMG). The EMG indicated that her muscles were slightly tense even though she reported feeling relaxed. With a few minutes of EMG biofeedback exploration, she discovered that she could relax her shoulder muscles by feeling them being heavy and melting.

Implementing home practice with a posture app

As part of the class homework, she was assigned a self-study for two weeks with the posture feedback app, Dario Desktop. The app uses the computer/laptop camera to monitor posture and provides visual feedback in a small window on the computer screen and/or an auditory signal each time she slouches as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Posture feedback to signal to participant that the person is slouching.

To observe the effect of the posture breathing training, she monitored her symptoms for three days without feedback and then installed the posture feedback application on her laptop to provide feedback whenever she slouched. The posture feedback reminded her to practice better posture during the day while working on her computer and also do a few stretches or shift to standing when using the computer for an extended period of time. Each time the feedback signal indicated she slouched, she would sit up and change her posture, breathe lower and slower and relax her shoulders.

She also monitored what factors triggered the slouching. In additionally, she added daily reminders to her phone to remind her of her posture and to stretch and stand after each hour of studying. After two weeks she recorded her symptoms for three days for the post assessment without posture feedback.

Results

The chronic headache condition which had been present for fourteen years disappeared and she has not used any medication since the first day of class. She reported after two weeks that her shoulder and back discomfort/pain, depression, anxiety and lack of motivation decreased as shown in Figure 2. At the fourteen week follow up, she continues to have no headaches and has not used any medication.

Figure 2. Changes in symptoms after implementing posture feedback for two weeks.

She used the desktop posture app every time she opened her laptop at home as often as 3-5 times per day (roughly 2-6 hours).In addition, when she felt beginning of discomfort or thought she should take medication, she would adjust her posture and breathe. While using the app, she identified numerous factors that were associated with slouching as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Behaviors associated with slouching.

Discussion

The decrease in depression, anxiety and increase in motivation may be the direct result of posture change; since, a slouched position tends to increase hopeless, helpless and powerless thoughts while the upright position tends to increase subjective felt energy and easier access to empowering and positive thoughts (Peper et al., 2017b; Veenstra et al., 2017; Wilson & Peper, 2004; Tsai et al., 2016). Most likely, a major factor that contributed to the elimination of her headaches was that she implemented changes in her behavior. One major factor was using posture feedback tool at home to remind her to sit tall and relax her shoulders while practicing slower diaphragmatic breathing. As she noted, “Although it was distracting to be reminded all the time about my posture, it did decrease my neck pain. With the pain reduction, I was able to sit at the computer longer and felt more motivated.”

The combination of slower lower abdominal breathing with the upright posture reversed her protective/defensive body position (tightening the muscle in the lower abdomen and pelvic floor and pressing the knees together while curling the shoulder forward for protection). The upright posture creates a position of empowerment and trust by which the lower abdomen could expand which supported health and regeneration. In addition, the upright posture allowed easier access to positive thoughts and reduced recall of hopeless, powerless, defeated memories. It is also possible that caffeine withdrawal was a co-factor in evoking headaches (Küçer, 2010). By eliminating the medication containing caffeine, she also eliminated the triggering of the caffeine withdrawal headaches.

This case example suggests that health care providers first rule out any pathology and then teach behavioral self-healing strategies that the clients can implement instead of immediately prescribing medications. These interventions could include slower and lower diaphragmatic breathing, upright posture feedback, muscle biofeedback training, hear rate variability training, stress management, cognitive behavior therapy and facilitating health promoting lifestyles modifications such as regular sleep, exercise and healthier diet. When students implement these behavioral changes as part of a five week self-healing program, many report significant decreases in symptoms such as headaches, anxiety, neck and shoulder pain, and gastrointestinal distress (Peper et al., 2016a).

Watch April Covell describe her experience with the self-healing approach to eliminate her chronic headaches.

See the following blogs for additional instructions how to breathe diaphragmatically.

References

Ahmed, S., Akter, R., Pokhrel, N. et al. (2021). Prevalence of text neck syndrome and SMS thumb among smartphone users in college-going students: a cross-sectional survey study. J Public Health (Berl.) 29, 411–416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-019-01139-4

Bauer, A.Z., Swan, S.H., Kriebel, D. et al. (2021). Paracetamol use during pregnancy — a call for precautionary action. Nat Rev Endocrinol . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-021-00553-7

Charles, N. E., Strong, S. J., Burns, L. C., Bullerjahn, M. R., & Serafine, K. M. (2021). Increased mood disorder symptoms, perceived stress, and alcohol use among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry research, 296, 113706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113706

Elizagaray-Garcia, I., Beltran-Alacreu, H., Angulo-Díaz, S., Garrigós-Pedrón, M., Gil-Martínez, A. (2020). Chronic Primary Headache Subjects Have Greater Forward Head Posture than Asymptomatic and Episodic Primary Headache Sufferers: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Pain Med, 21(10):2465-2480. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnaa235

Greden, J.F., Victor, B.S., Fontaine, P., & Lubetsky, M. (1980). Caffeine-Withdrawal Headache: A Clinical Profile. Psychosomatics, 21(5), 411-413, 417-418. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0033-3182(80)73670-8

Küçer, N. (2010). The relationship between daily caffeine consumption and withdrawal symptoms: a questionnaire-based study. Turk J Med Sci, 40(1), 105-108. https://doi.org/10.3906/sag-0809-26

Kuehn, B.M. (2021). Increase in Myopia Reported Among Children During COVID-19 Lockdown. JAMA, 326(11),999. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.14475

MacHose, M. & Peper, E. (1991). The effect of clothing on inhalation volume. Biofeedback and Self-Regulation 16, 261–265 (1991). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01000020

Peper, E., Booiman, A., Lin, I-M, Harvey, R., & Mitose, J. (2016). Abdominal SEMG Feedback for Diaphragmatic Breathing: A Methodological Note. Biofeedback. 44(1), 42-49. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-44.1.03

Peper, E., Gilbert, C.D., Harvey, R. & Lin, I-M. (2015). Did you ask about abdominal surgery or injury? A learned disuse risk factor for breathing dysfunction. Biofeedback. 34(4), 173-179. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-43.4.06

Peper, E., Lin, I-M., Harvey, R., & Perez, J. (2017b). How posture affects memory recall and mood. Biofeedback. 45 (2), 36-41. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-45.2.01

Peper, E., Mason, L., Harvey, R., Wolski, L, & Torres, J. (2020). Can acid reflux be reduced by breathing? Townsend Letters-The Examiner of Alternative Medicine, 445/446, 44-47. https://www.townsendletter.com/article/445-6-acid-reflux-reduced-by-breathing/

Peper, E., Mason, L., Huey, C. (2017a). Healing irritable bowel syndrome with diaphragmatic breathing. Biofeedback. (45-4). https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-45.4.04

Peper, E., Miceli, B., & Harvey, R. (2016a). Educational Model for Self-healing: Eliminating a Chronic Migraine with Electromyography, Autogenic Training, Posture, and Mindfulness. Biofeedback, 44(3), 130–137. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-44.3.03

Peper, E., Wilson, V., Martin, M., Rosegard, E., & Harvey, R. (2021). Avoid Zoom fatigue, be present and learn. NeuroRegulation, 8(1), 47–56. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.8.1.47

Schulman, E.A. (2002). Breath-holding, head pressure, and hot water: an effective treatment for migraine headache. Headache, 42(10), 1048-50. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1526-4610.2002.02237.x

Tsai, H. Y., Peper, E., & Lin, I. M.* (2016). EEG patterns under positive/negative body postures and emotion recall tasks. NeuroRegulation, 3(1), 23-27. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.3.1.23

Veenstra, L., Schneider, I.K., & Koole, S.L. (2017). Embodied mood regulation: the impact of body posture on mood recovery, negative thoughts, and mood-congruent recall. Cogntion and Emotion, 31(7), 1361-1376. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2016.1225003

Wilson, V.E. and Peper, E. (2004). The effects of upright and slumped postures on the generation of positive and negative thoughts. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 29(3), 189–195. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:apbi.0000039057.32963.34

Make your New Year Resolution come true

Posted: December 28, 2021 Filed under: behavior, emotions, healing, health, self-healing | Tags: habits 5 Comments

It is the time of year when we once again make New Year resolutions, “I plan to exercise every day,” “I will stop drinking,” “I will eat less processed foods and more fruits and vegetables.” We use our will power and positive thoughts to begin these new activities; however, our will power often fades out and we quickly fall of the wagon. The reason vary such as, I had planned to jog today; however it is raining, I was planning to eat more vegies; however, I had dinner with a friend and ate a juicy hamburger, I had planned to meditate; however, I needed to help my son. So many other things took priority and the motivation disappeared..

Yet it is possible to be successful with starting and then maintaining new health promoting habits. The key is to increase the friction for the behaviors that you want to reduce and decrease the friction for behaviors that you want to increase. Friction is the extra work you need to do in order to do the task. For example, to eat fewer cookies, increase the friction by not having them in the house (you now have to go to the store to buy them) or by placing them somewhere where it takes greater effort to get them such as the top shelf for which that you need a small ladder to reach them. The extra effort (increased friction) brings awareness to the automatic behavior. At that point, you can interrupt your unconscious eating pattern and choose to do something else. On the other hand, to increase eating fruits, decrease the friction by having the fruit right in front of you on the table so that you can take one without thinking.

The key is to interrupt the habit chain of behavior you want to reduce and automate the habit chains of behaviors you want to increase. The more you do a behavior and the more pleasurable it is, the more likely will the new behaviore become an automatic habit. To learn how to change friction and how to be successful in creating new habits, listen to Shankar Vedantam Hidden Brain’s Podcast, Creatures of Habit.

Eat what grows in season

Posted: December 14, 2021 Filed under: health, Nutrition/diet, self-healing | Tags: food, herbicide, organic foods, pesticides Leave a commentAndrea Castillo and Erik Peper

We are what we eat. Our body is synthesized from the foods we eat. Creating the best conditions for a healthy body depends upon the foods we ingest as implied by the phrase, Let food be thy medicine, attributed to Hippocrates, the Greek founder of western medicine (Cardenas, 2013). The foods are the building blocks for growth and repair. Comparing our body to building a house, the building materials are the foods we eat, the architect’s plans are our genetic coding, the care taking of the house is our lifestyle and the weather that buffers the house is our stress reactions. If you build a house with top of the line materials and take care of it, it will last a life time or more. Although the analogy of a house to the body is not correct since a house cannot repair itself, it is a useful analogy since repair is an ongoing process to keep the house in good shape. Our body continuously repairs itself in the process of regeneration. Our health will be better when we eat organic foods that are in season since they have the most nutrients.

Organic foods have much lower levels of harmful herbicides and pesticides which are neurotoxins and harmful to our health (Baker et al., 2002; Barański, et al, 2014). Crops have been organically farmed have higher levels of vitamins and minerals which are essential for our health compared to crops that have been chemically fertilized (Peper, 2017),

Even seasonality appears to be a factor. Foods that are outdoor grown or harvested in their natural growing period for the region where it is produced, tend to have more flavor that foods that are grown out of season such as in green houses or picked prematurely thousands of miles away to allow shipping to the consumer. Compare the intense flavor of small strawberry picked in May from the plant grown in your back yard to the watery bland taste of the great looking strawberries bought in December.

The seasonality of food

It’s the middle of winter. The weather has cooled down, the days are shorter, and some nights feel particularly cozy. Maybe you crave a warm bowl of tomato soup so you go to the store, buy some beautiful organic tomatoes, and make yourself a warm meal. The soup is… good. But not great. It is a little bland even though you salted it and spiced it. You can’t quite put your finger on it, but it feels like it’s missing more tomato flavor. But why? You added plenty of tomatoes. You’re a good cook so it’s not like you messed up the recipe. It’s just—missing something.

That something could easily be seasonality. The beautiful, organic tomatoes purchased from the store in the middle of winter could not have been grown locally, outside. Tomatoes love warm weather and die when days are cooler, with temperatures dropping to the 30s and 40s. So why are there organic tomatoes in the store in the middle of cold winters? Those tomatoes could’ve been grown in a greenhouse, a human-made structure to recreate warmer environments. Or, they could’ve been grown organically somewhere in the middle of summer in the southern hemisphere and shipped up north (hello, carbon emissions!) so you can access tomatoes year-round.

That 24/7 access isn’t free and excellent flavor is often a sacrifice we pay for eating fruits and vegetables out of season. Chefs and restaurants who offer seasonal offerings, for example, won’t serve bacon, lettuce, tomato (BLT) sandwiches in winter. Not because they’re pretentious, but because it won’t taste as great as it would in summer months. Instead of winter BLTs, these restaurants will proudly whip up seasonal steamed silky sweet potatoes or roasted brussels sprouts with kimchee puree.

When we eat seasonally-available food, it’s more likely we’re eating fresher food. A spring asparagus, summer apricot, fall pear, or winter grapefruit doesn’t have to travel far to get to your plate. With fewer miles traveled, the vitamins, minerals, and secondary metabolites in organic fruits and vegetables won’t degrade as much compared to fruits and vegetables flown or shipped in from other countries. Seasonal food tastes great and it’s great for you too.

If you’re curious to eat more of what’s in season, visit your local farmers market if it’s available to you. Strike up a conversation with the people who grow your food. If farmers markets are not available, take a moment to learn what is in season where you live and try those fruits and vegetables next time to go to the store. This Seasonal Food Guide for all 50 states is a great tool to get you started.

Once you incorporate seasonal fruits and vegetables into your daily meals, your body will thank you for the health boost and your meals will gain those extra flavors. Remember, you’re not a bad cook: you just need to find the right seasonal partners so your dinners are never left without that extra little something ever again.

Sign up for Andrea Castillo’s Seasonal, a newsletter that connects you to the Bay Area food system, one fruit and vegetable at a time. Andrea is a food nerd who always wants to know the what’s, how’s, when’s, and why’s of the food she eats.

References

Baker, B.P., Benbrook, C.M., & Groth III, E., & Lutz, K. (2002). Pesticide residues in conventional, integrated pest management (IPM)-grown and organic foods: insights from three US data sets. Food Additives and Contaminants, 19(5) http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02652030110113799

Barański, M., Średnicka-Tober, D., Volakakis, N., Seal, C., Sanderson, R., Stewart, G., . . . Leifert, C. (2014). Higher antioxidant and lower cadmium concentrations and lower incidence of pesticide residues in organically grown crops: A systematic literature review and meta-analyses. British Journal of Nutrition, 112(5), 794-811. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114514001366

Cardenas, E. (2013). Let not thy food be confused with thy medicine: The Hippocratic misquotation,e-SPEN Journal, I(6), e260-e262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnme.2013.10.002

Peper, E. (2017). Yes, fresh organic food is better! the peper perspective. https://peperperspective.com/2017/10/27/yes-fresh-organic-food-is-better/

Reduce your risk of COVID-19 variants and future pandemics

Posted: July 5, 2021 Filed under: behavior, health, Nutrition/diet, self-healing | Tags: COVID-19, immune, pandemic, prevention, vitamin D 2 CommentsErik Peper, PhD and Richard Harvey, PhD

The number of hospitalizations and deaths from COVID-19 are decreasing as more people are being vaccinated. At the same time, herd immunity will depend on how vaccinated and unvaccinated people interact with one another. Close-proximity, especially indoor interactions, increases the likelihood of transmission of coronavirus for unvaccinated individuals. During the summer months, people tend to congregate outdoors which reduces viral transmission and also increases vitamin D production which supports the immune system (Holick, 2021)..

Most likely, COVID-19 disease will become endemic because the SARS-CoV-2 virus will continue to mutate. Already Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla stated on April 15, 2021 that people will “likely” need a third dose of a Covid-19 vaccine within 12 months of getting fully vaccinated. Although, at this moment the vaccines are effective against several variants, we need to be ready for the next COVID XX outbreak.

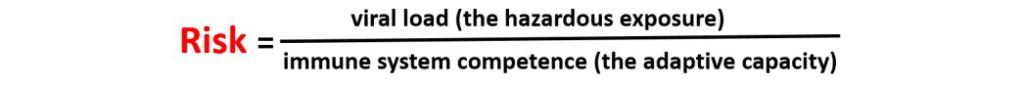

To reduce future infections, the focus of interventions should 1) reduce virus exposure, 2) vaccinate to activate the immune system, and 3) enhance the innate immune system competence. The risk of illness may relate to virus density exposure and depend upon the individual’s immune competence (Gandhi & Rutherford, 2020; Mukherjee, 2020) which can be expressed in the following equation.

Reduce viral load (hazardous exposure)

Without exposure to the virus and its many variants, the risk is zero which is impossible to achieve in democratic societies. People do not live in isolated bubbles but in an interconnected world and the virus does not respect borders or nationalities. Therefore, public health measures need to focus upon strategies that reduce virus exposure by encouraging or mandating wearing masks, keeping social distance, limiting social contact, and increasing fresh air circulation.

Wearing masks reduces the spread of the virus since people may shed viruses one or two days before experiencing symptoms (Lewis et al., 2021). When a person exhales through the mask, a good fitting N95 mask will filter out most of the virus and thereby reduce the spread of the virus during exhalation. To protect oneself from inhaling the virus, the mask needs be totally sealed around the face with the appropriate filters. Systematic observations suggest that many masks such as bandanas or surgical masks do not filter out the virus (Fisher et al., 2020).

Fresh air circulation reduces the virus exposure and is more important than the arbitrary 6 feet separation (CDC, May 13, 2021). If separated by 6 feet in an enclosed space, the viral particles in the air will rapidly increase even when the separation is 10 feet or more. On the other hand, if there is sufficient fresh air circulation, even three feet of separation would not be a problem. The spatial guidelines need to be based upon air flow and not on the distance of separation as illustrated in the outstanding graphical modeling schools by Nick Bartzokas et al. (February 26, 2021) in the New York Times article, Why opening windows is a key to reopening schools.

The public health recommendations of sheltering-in-place to prevent exposure or spreading the virus may also result in social isolation. Thus, shelter-in-place policies have resulted in compromising physical health such as weight gain (e.g. average increase of more than 7lb in weight in America according to Lin et al., 2021), reduced physical activity and exercise levels (Flanagan et al., 2021) and increased anxiety and depression (e.g. a three to four fold increase in the self-report of anxiety or depression according to Abbott, 2021). Increases in weight, depression and anxiety symptoms tend to decrease immune competence (Leonard, 2010). In addition, the stay at home recommendations especially in the winter time meant that individuals are less exposed to sunlight which results in lower vitamin D levels which is correlated with increased COVID-19 morbidity (Seheult, 2020).

Increase immune competence

Vaccination is the primary public health recommendation to prevent the spread and severity of COVID-19. Through vaccination, the body increases its adaptive capacity and becomes primed to respond very rapidly to virus exposure. Unfortunately, as Pfizer Chief Executive Albert Bourla states, there is “a high possibility” that emerging variants may eventually render the company’s vaccine ineffective (Steenhuysen, 2021). Thus, it is even more important to explore strategies to enhance immune competence independent of the vaccine.

Public Health policies need to focus on intervention strategies and positive health behaviors that optimize the immune system capacity to respond. The research data has been clear that COVID -19 is more dangerous for those whose immune systems are compromised and have comorbidities such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease, regardless of age.

Comorbidity and being older are the significant risk factors that contribute to COVID-19 deaths. For example, in evaluating all patients in the Fair Health National Private Insurance Claims (FH NPIC’s) longitudinal dataset, researchers identified 467,773 patients diagnosed with COVID-19 from April 1, 2020, through August 31, 2020. The severity of the illness and death from COVID-19 depended on whether the person had other co-morbidities first as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The distribution of patients with and without a comorbidity among all patients diagnosed with COVID-19 (left) and all deceased COVID-19 patients (right) April-August 2020. Reproduced by permission from: https://www.ajmc.com/view/contributor-links-between-covid-19-comorbidities-mortality-detailed-in-fair-health-study

Each person who died had about 2 or 3 types of pre-existing co-morbidities such as cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, obesity, congestive heart failure, chronic kidney disease, respiratory disease and cancer (Ssentongo et al., 2020; Gold et al., 2020). The greater the frequency of comorbidities the greater the risk of death, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Across all age groups, the risk of COVID-19 death increased significantly as a patient’s number of comorbidities increased. Compared to patients with no comorbidities. Reproduced by permission from https://s3.amazonaws.com/media2.fairhealth.org/whitepaper/asset/Risk%20Factors%20for%20COVID-19%20Mortality%20among%20Privately%20Insured%20Patients%20-%20A%20Claims%20Data%20Analysis%20-%20A%20FAIR%20Health%20White%20Paper.pdf

Although the risk of serious illness and death is low for young people, the presence of comorbidity increases the risk. Kompaniyets et al. (2021) reported that for patients under 18 years with severe COVID-19 illness who required ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, or died most had underlying medical conditions such as asthma, neurodevelopmental disorders, obesity, essential hypertension or complex chronic diseases such as malignant neoplasms or multiple chronic conditions.

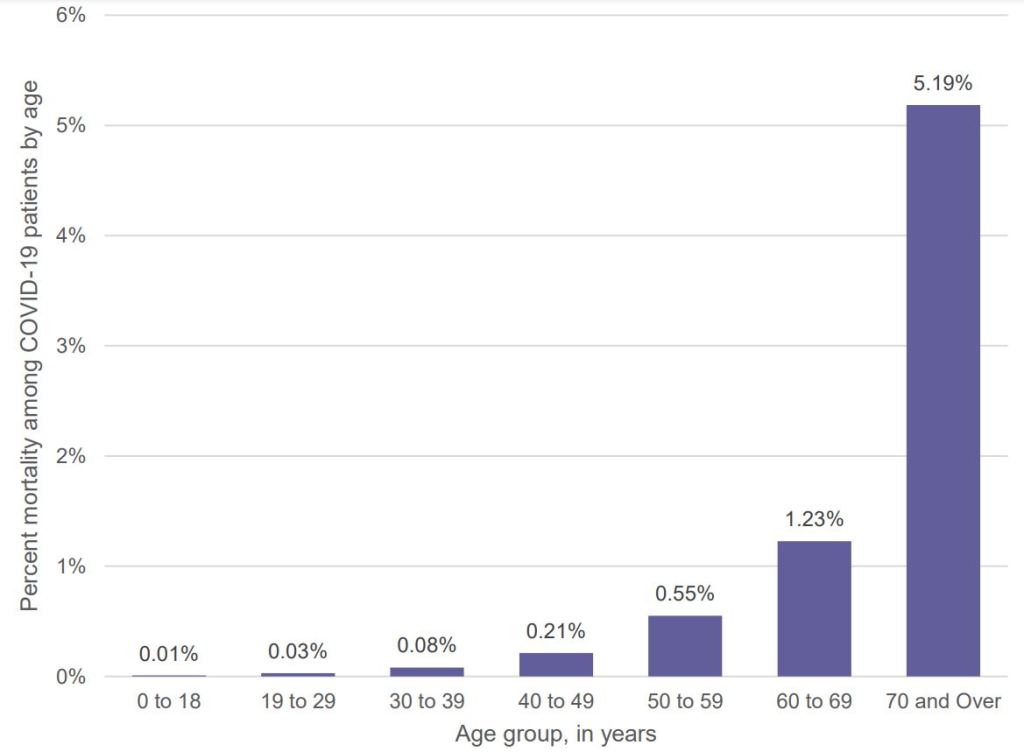

Consistent with earlier findings, the Fair Health National Private Insurance Claims (FH NPIC’s) longitudinal dataset also showed that the COVID-19 mortality rate rose sharply with age as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Percent mortality among COVID-19 patients by age, April-August 2020. Reproduced by permission from: https://s3.amazonaws.com/media2.fairhealth.org/whitepaper/asset/Risk%20Factors%20for%20COVID-19%20Mortality%20among%20Privately%20Insured%20Patients%20-%20A%20Claims%20Data%20Analysis%20-%20A%20FAIR%20Health%20White%20Paper.pdf

Optimize antibody response from vaccinations

Assuming that the immune system reacts similarly to other vaccinations, higher antibody response is evoked when the vaccine is given in the morning versus the afternoon or after exercise (Long et al., 2016; Long et al., 2012). In addition, the immune response may be attenuated if the person suppresses the body’s natural immune response–the flulike symptoms which may occur after the vaccination–with Acetaminophen (Tylenol (Graham et al, 1990).

Support the immune system with a healthy life style

Support the immune system by implementing a lifestyle that reduces the probability of developing comorbidities. This means reducing risk factors such as vaping, smoking, immobility and highly processed foods. For example, young people who vape experience a fivefold increase to become seriously sick with COVID-19 (Gaiha, Cheng, & Halpern-Felsher, 2020); similarly, cigarette smoking increases the risk of COVID morbidity and mortality (Haddad, Malhab, & Sacre, 2021).

There are many factors that have contributed to the epidemic of obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease and other chronic diseases. In many cases, the environment and lifestyle factors (lack of exercise, excessive intake of highly processed foods, environmental pollution, social isolation, stress, etc.) significantly contribute to the initiation and development of comorbidities. Genetics also is a factor; however, the generic’s risk factor may not be triggered if there are no environmental/behavioral exposures. Phrasing it colloquially, Genetics loads the gun, environment and behavior pulls the trigger. Reducing harmful lifestyle behaviors and environment is not simply an individual’s responsibility but a corporate and governmental responsibility. At present, harmful lifestyles choices are actively supported by corporate and government policies that choose higher profits over health. For example, highly processed foods made from corn, wheat, soybeans, rice are grown by farmers with US government farm subsidies. Thus, many people especially of lower economic status live in food deserts where healthy non-processed organic fruits and vegetable foods are much less available and more expensive (Darmon & Drewnowski, 2008; Michels, Vynckier, Moreno, L.A. et al. 2018; CDC, 2021). In the CDC National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey that analyzed the diet of 10,308 adults, researchers Siegel et al. (2016) found that “Higher consumption of calories from subsidized food commodities was associated with a greater probability of some cardiometabolic risks” such as higher levels of obesity and unhealthy blood glucose levels (which raises the risk of Type 2 diabetes).

Immune competence is also affected by many other factors such as exercise, stress, shift work, social isolation, and reduced micronutrients and Vitamin D (Zimmermann & Curtis, 2019). Even being sedentary increases the risk of dying from COVID as reported by the Kaiser Permanente Southern California study of 50,000 people who developed COVID (Sallis et al., 2021).

People who exercised 10 minutes or less each week were hospitalized twice as likely and died 2.5 times more than people who exercised 150 minutes a week (Sallis et al., 2021). Although exercise tends to enhance immune competence (da Silveira et al, 2020), it is highly likely that exercise is a surrogate marker for other co-morbidities such as obesity and heart disease as well as aging. At the same time sheltering–in-place along with the increase in digital media has significantly reduced physical activity.

The importance of vitamin D

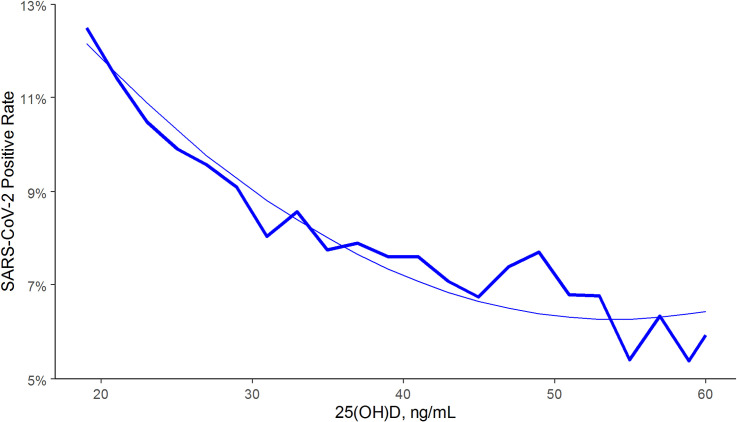

Low levels of vitamin D is correlated with poorer prognosis for patients with COVID-19 (Munshi et al., 2021). Kaufman et al. (2020) reported that the positivity rate correlated inversely with vitamin D levels as shown in figure 4.

Figure 4. SARS-CoV-2 NAAT positivity rates and circulating 25(OH)D levels in the total population. From: Kaufman, H.W., Niles, J.K., Kroll, M.H., Bi, C., Holick, M.F. (2020). SARS-CoV-2 positivity rates associated with circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels. PLoS One. 15(9):e0239252. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239252

Vitamin D is a modulator for the immune system (Baeke, Takiishi, Korf, Gysemans, & Mathieu, 2010). There is an inverse correlation of all-cause, cardiovascular, cancer, and respiratory disease mortality with hydroxyvitamin D concentrations in a large cohort study (Schöttker et al., 2013). For a superb discussion about how much vitamin D is needed, see the presentation, The D-Lightfully Controversial Vitamin D: Health Benefits from Birth until Death, by Dr. Michael F. Holick, Ph.D., M.D. from the University Medical Center Boston.

Low vitamin D levels may partially explain why in the winter there is an increase in influenza. During winter time, people have reduced sunlight exposure so that their skin does not produce enough vitamin D. Lower levels of vitamin D may be a cofactor in the increased rates of COVID among people of color and older people. The darker the skin, the more sunlight the person needs to produce Vitamin D and as people become older their skin is less efficient in producing vitamin D from sun exposure (Harris, 2006; Gallagher, 2013). Vitamin D also moderates macrophages by regulating the release, and the over-release of inflammatory factors in the lungs (Khan et al., 2021).

Watch the interesting presentation by Professor Roger Seheult, MD, UC Riverside School of Medicine, Vitamin D and COVID 19: The Evidence for Prevention and Treatment of Coronavirus (SARS CoV 2). 12/20/2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ha2mLz-Xdpg

What can be done NOW to enhance immune competence?

We need to recognize that once the COVID-19 pandemic has passed, it does not mean it is over. It is only a reminder that a new COVID-19 variant or another new virus will emerge in the future. Thus, the government public health policies need to focus on promoting health over profits and aim at strategies to prevent the development of chronic illnesses that affect immune competence. One take away message is to incorporate behavioral medicine prescriptions supporting a healthy lifestyle into treatment plans, such as prescribing a walk in the sun to increase vitamin D production and develop dietary habits of eating organic locally grown vegetable and fruits foods. Even just reducing the refined sugar content in foods and drinks is challenging although it may significantly reduce incidence and prevalence of obesity and diabetes (World Health Organization, 2017. The benefits of such an approach has been clearly demonstrated by the Pennsylvania-based Geisinger Health System’s Fresh Food Farmacy. This program for food-insecure people with Type 2 diabetes and their families provides enough fresh fruits and vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins for two healthy meals a day five days a week. After one year there was a 40 percent decrease in the risk of death or serious complications and an 80 percent drop in medical costs per year (Brody, 2020).

The simple trope of this article ‘eat well, exercise and get good rest’ and increase your immune competence concludes with some simple reminders.

- Increase availability of organic foods since they do not contain pesticides such as glyphosate residue that reduce immune competence.

- Increase vegetable and fruits and reduce highly processed foods, simple carbohydrates and sugars.

- Decrease sitting and increase movement and exercise

- Increase sun exposure without getting sunburns

- Master stress management

- Increase social support

For additional information see: https://peperperspective.com/2020/04/04/can-you-reduce-the-risk-of-coronavirus-exposure-and-optimize-your-immune-system/

References

Baeke, F., Takiishi, T., Korf, H., Gysemans, C., & Mathieu, C. (2010). Vitamin D: modulator of the immune system,Current Opinion in Pharmacology,10(4), 482-496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coph.2010.04.001

Brody, J. (2020). How Poor Diet Contributes to Coronavirus Risk. The New York Times, April 20, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/20/well/eat/coronavirus-diet-metabolic-health.html?referringSource=articleShare

CDC. (2021). Adult Obesity Prevalence Maps. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/prevalence-maps.html#nonhispanic-white-adults

CDC. (May 13, 2021). Ways COVID-19 Spreads. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/how-covid-spreads.html

Darmon, N. & Drewnowski, A. (2008). Does social class predict diet quality?, The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 87(5), 2008, 1107–1117. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/87.5.1107

da Silveira, M. P., da Silva Fagundes, K. K., Bizuti, M. R., Starck, É., Rossi, R. C., & de Resende E Silva, D. T. (2021). Physical exercise as a tool to help the immune system against COVID-19: an integrative review of the current literature. Clinical and experimental medicine, 21(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10238-020-00650-3

Elflein, J. (2021). COVID-19 deaths reported in the U.S. as of January 2, 2021, by age. Downloaded, 1/13/2021 from https://www.statista.com/statistics/1191568/reported-deaths-from-covid-by-age-us/

Fisher, E. P., Fischer, M.C., Grass, D., Henrion, I., Warren, W.S., & Westmand, E. (2020). Low-cost measurement of face mask efficacy for filtering expelled droplets during speech. Science Advance, (6) 36, eabd3083. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abd3083

Flanagan. E.W., Beyl, R.A., Fearnbach, S.N., Altazan, A.D., Martin, C.K., & Redman, L.M. (2021). The Impact of COVID-19 Stay-At-Home Orders on Health Behaviors in Adults. Obesity (Silver Spring), (2), 438-445. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.23066

Gaiha, S.M., Cheng, J., & Halpern-Felsher, B. (2020). Association Between Youth Smoking, Electronic Cigarette Use, and COVID-19. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(4), 519-523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.07.002

Gallagher J. C. (2013). Vitamin D and aging. Endocrinology and metabolism clinics of North America, 42(2), 319–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecl.2013.02.004

Gandhi, M. & Rutherford, G. W. (2020). Facial Masking for Covid-19 — Potential for “Variolation” as We Await a Vaccine. New England Journal of Medicine, 383(18), e101 https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp2026913

Gold, M.S., Sehayek, D., Gabrielli, S., Zhang, X., McCusker, C., & Ben-Shoshan, M. (2020). COVID-19 and comorbidities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Postgrad Med, 132(8), 749-755. https://doi.org/10.1080/00325481.2020.1786964

Graham, N.M., Burrell, C.J., Douglas, R.M., Debelle, P., & Davies, L. (1990). Adverse effects of aspirin, acetaminophen, and ibuprofen on immune function, viral shedding, and clinical status in rhinovirus-infected volunteers. J Infect Dis., 162(6), 1277-82. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/162.6.1277

Haddad, C., Malhab, S.B., & Sacre, H. (2021). Smoking and COVID-19: A Scoping Review. Tobacco Use Insights, 14, First Published February 15, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1177/1179173X21994612

Harris, S.S. (2006). Vitamin D and African Americans. The Journal of Nutrition, 136(4), 1126-1129. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/136.4.1126

Kaufman, H.W., Niles, J.K., Kroll, M.H., Bi, C., Holick, M.F. (2020). SARS-CoV-2 positivity rates associated with circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels. PLoS One. 15(9):e0239252. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239252

Khan, A. H., Nasir, N., Nasir, N., Maha, Q., & Rehman, R. (2021). Vitamin D and COVID-19: is there a role?. Journal of Diabetes & Metabolic Disorders, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40200-021-00775-6

Kompaniyets, L., Agathis, N.T., Nelson, J.M., et al. (2021). Underlying Medical Conditions Associated With Severe COVID-19 Illness Among Children. JAMA Netw Open. 4(6):e2111182. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.11182

Leonard B. E. (2010). The concept of depression as a dysfunction of the immune system. Current immunology reviews, 6(3), 205–212. https://doi.org/10.2174/157339510791823835

Lewis, N. M., Duca, L. M., Marcenac, P., Dietrich, E. A., Gregory, C. J., Fields, V. L….Kirking, H. L. (2021). Characteristics and Timing of Initial Virus Shedding in Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2, Utah, USA. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 27(2), 352-359. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2702.203517

Long, J.E., Drayson, M.T., Taylor, A.E., Toellner, K.M., Lord, J.M., & Phillips, A.C. (2016). Morning vaccination enhances antibody response over afternoon vaccination: A cluster-randomised trial. Vaccine, 34(24), 2679-85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.04.032.

Long. J.E., Ring, C., Drayson, M., Bosch, J., Campbell, J.P., Bhabra, J., Browne, D., Dawson, J., Harding, S., Lau, J., & Burns, V.E. (2012). Vaccination response following aerobic exercise: can a brisk walk enhance antibody response to pneumococcal and influenza vaccinations? Brain Behav Immun., 26(4), 680-687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2012.02.004

Merelli, A. (2021, February 2). Pfizer’s Covid-19 vaccine is set to be one of the most lucrative drugs in the world. QUARTZ. https://qz.com/1967638/pfizer-will-make-15-billion-from-covid-19-vaccine-sales/

Michels, N., Vynckier, L., Moreno, L.A. et al. (2018). Mediation of psychosocial determinants in the relation between socio-economic status and adolescents’ diet quality. Eur J Nutr, 57, 951–963. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-017-1380-8

Mukherjee, S. (2020). How does the coronavirus behave inside a patient? We’ve counted the viral spread across peoples; now we need to count it within people. The New Yorker, April 6, 2020. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/04/06/how-does-the-coronavirus-behave-inside-a-patient?utm_source=onsite-share&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=onsite-share&utm_brand=the-new-yorker

Munshi, R., Hussein, M.H., Toraih, E.A., Elshazli, R.M., Jardak, C., Sultana, N., Youssef, M.R., Omar, M., Attia, A.S., Fawzy, M.S., Killackey, M., Kandil, E., & Duchesne, J. (2020) Vitamin D insufficiency as a potential culprit in critical COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol, 93(2), 733-740. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.26360

Renoud. L, Khouri, C., Revol, B., et al. (2021) Association of Facial Paralysis With mRNA COVID-19 Vaccines: A Disproportionality Analysis Using the World Health Organization Pharmacovigilance Database. JAMA Intern Med. Published online April 27, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.2219

Sallis, R., Young, D. R., Tartof, S.Y., et al. (2021). Physical inactivity is associated with a higher risk for severe COVID-19 outcomes: a study in 48 440 adult patients. British Journal of Sports Medicine. Published Online First: 13 April 2021. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2021-104080

Schöttker, B., Haug, U., Schomburg, L., Köhrle, L., Perna, L., Müller. H., Holleczek, B., & Brenner. H. (2013). Strong associations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels with all-cause, cardiovascular, cancer and respiratory disease mortality in a large cohort study. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 97(4), 782–793 2013; https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.112.047712

Siegel, K.R., McKeever Bullard, K., Imperatore. G., et al. (2016). Association of Higher Consumption of Foods Derived From Subsidized Commodities With Adverse Cardiometabolic Risk Among US Adults. JAMA Intern Med. 176(8), 1124–1132. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2410

Ssentongo P, Ssentongo AE, Heilbrunn ES, Ba DM, Chinchilli VM (2020) Association of cardiovascular disease and 10 other pre-existing comorbidities with COVID-19 mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 15(8): e0238215. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238215

Steenhuysen, J. 2021, Jan 30). Fresh data show toll South African virus variant takes on vaccine efficacy. Accessed January 31, 2021. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-vaccines-variant/fresh-data-show-toll-south-african-virus-variant-takes-on-vaccine-efficacy-idUSKBN29Z0I7

World Health Organization. (2017). Sugary drinks1 – a major contributor to obesity and diabetes. WHO/NMH/PND/16.5 Rev. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/260253/WHO-NMH-PND-16.5Rev.1-eng.pdf?sequence=1

Zimmermann, P. & Curtis, N. (2019). Factors That Influence the Immune Response to Vaccination. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 32(2), 1-50. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00084-18

Useful resources about breathing, phytonutrients and exercise

Posted: June 30, 2021 Filed under: behavior, Breathing/respiration, cancer, Evolutionary perspective, health, Nutrition/diet, self-healing, Uncategorized | Tags: diet, exercise, immune system, nasal breathing, phytonutrients, respiration 1 Comment

Dysfunctional breathing, eating highly processed foods, and lack of movement contribute to development of illnesses such as cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease and many chronic diseases. They also contributes to immune dysregulation that increases vulnerability to infectious diseases, allergies and autoimmune diseases. If you wonder what breathing patterns optimize health, what foods have the appropriate phytonutrients to support your immune system, or what the evidence is that exercise reduces illness and promotes longevity, look at the following resources.

Breath: the mind-body connector that underlies health and illness

Read the outstanding article by Martin Petrus (2021). How to breathe.

https://psyche.co/guides/how-to-breathe-your-way-to-better-health-and-transcendence

You are the food you eat

Watch the superb webinar presentation by Deanna Minich, MS., PHD., FACN, CNS, (2021) Phytonutrient Support for a Healthy Immune System.

Movement is life

Explore the summaries of recent research that has demonstrated the importance of exercise to increase healthcare saving and reduce hospitalization and death.

Reactivate your second heart

Posted: June 14, 2021 Filed under: behavior, computer, digital devices, ergonomics, Evolutionary perspective, Exercise/movement, health, Pain/discomfort, posture, screen fatigue, self-healing, zoom fatigue | Tags: blood clots, blood flow, calf muscle, cardiovascular disease, deep vein thrombosis, edema, exhaustion, Sitting disease, tired legs, Type 2 diabetes 6 CommentsMonica Almendras and Erik Peper

Adapted from: Almendras, M. & Peper, E. (2021). Reactivate your second heart. Biofeedback, 49(4), 99-102. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-49.04.07

Have you ever wondered why after driving long distances or sitting in a plane for hours your feet and lower leg are slightly swollen (Hitosugi, Niwa, & Takatsu, 2000)? It is the same process by which soldiers standing in attention sometimes faint or why salespeople or cashiers, especially those who predominantly stand most of the day, have higher risk of developing varicose veins. By the end of the day, they feel that their legs being heavy and tired? In the vertical position, gravity is the constant downward force that pools venous blood and lymph fluid in the legs. The pooling of the blood and reduced circulation is a contributing factor why airplane flights of four or more hours increases the risk for developing blood clots-deep vein thrombosis (DVT) (Scurr, 2002; Kuipers et al., 2007). When blood clots reaches the lung, they can cause a pulmonary embolisms that can be fatal. In other cases, they may even travel to the brain and cause strokes.[1]

Sitting without moving the leg muscles puts additional stress on your heart, as the blood and lymph pools in the legs. Tightening and relaxing the calf muscles can prevent the pooling of the blood. The inactivity of your calf muscles does not allow the blood to flow upwards. The episodic contractions of the calf muscles squeezes the veins and pumps the venous blood upward towards the heart as illustrated in figure 1. Therefore, it is important to stand, move, and walk so that your calf muscle can act as a second heart (Prevosti, April 16, 2020).

Figure 1. Your calf muscles are your second heart! The body is engineered so that when you walk, the calf muscles pump venous blood back toward your heart. Reproduced by permission from Dr. Louis Prevosti of the Center for Vein Restoration (https://veinatlanta.com/your-second-heart/).

To see the second heart in action watch the YouTube video, Medical Animation Movie on Venous Disorders, by the Sigvaris Group Europe (2017).

If you stand too long and experienced slight swelling of the legs, raise your feet slightly higher than the head, to help drain the fluids out of the legs. Another way to reduce pooling of fluids and prevent blood clots and edema is to wear elastic stockings or wrap the legs with intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) devices that periodically compresses the leg (Zhao et al., 2014). You can also do this by performing foot rotations or other leg and feet exercises. The more the muscle of the legs and feet contract and relax, the more are the veins episodically compressed which increases venous blood return. Yet in our quest for efficiency and working in front of screens, we tend to sit for long time-periods.

Developing sitting disease

Have you noticed how much of the time you sit during the day? We sit while studying, working, socializing and entertaining in front of screens. This sedentary behavior has significantly increased during the pandemic (Zheng et al, 2010). Today, we do not need to get up because we call on Amazon’s Alexa, Apple’s Siri or Google’s Hey Google to control timers, answer queries, turn on the lights, fan, TV, and other home devices. Everything is at our fingertips and we have finally become The Jetsons without the flying cars (an American animated sitcom aired in the 1960s). There is no need to get up from our seat to do an activity. Everything can be controlled from the palm of our hand with a mobile phone app.

With the pandemic, our activities involve sitting down with minimum or no movement at all. We freeze our body’s position in a scrunch–a turtle position–and then we wonder why we get neck, shoulder, and back pains–a process also observed in young adults or children. Instead of going outside to play, young people sit in front of screens. The more we sit and watch screens, the poorer is our mental and physical health (Smith et al., 2020; Matthews et al., 2012). We are meant to move instead of sitting in a single position for eight or more hours while fixating our attention on a screen.

The visual stimuli on screen captures our attention, whether it is data entry, email, social media, or streaming videos (Peper, Harvey & Faass, 2020). While at the computer, we often hold up our index finger on the mouse and wait with baited breath to react. Holding this position and waiting to click may look harmless; however, our right shoulder is often elevated and raised upward towards our ear. This bracing pattern is covert and contributes to the development of discomfort. The moment your muscles tighten, the blood flow through the muscle is reduced (Peper, Harvey, & Tylova, 2006). Muscles are most efficient when they alternately tighten and relax. It is no wonder that our body starts to scream for help when feeling pain or discomfort on our neck, shoulders, back and eyes.

Why move?

Figure 2a and 2b Move instead of sit (photos source: Canva.com).

The importance of tightening and then relaxing muscles is illustrated during walking. During the swing phase of walking, the hip flexor muscles relax, tighten, relax again, tighten again, and this is repeated until the destination is reached. It is important to relax the muscles episodically for blood flow to bring nutrients to the tissue and remove the waste product. Most people can walk for hours; however, they can only lift their foot from the floor (raise their leg up for a few minutes) till discomfort occurs.

Movement is what we need to do and play is a great way to do it. Dr. Joan Vernikos (2016) who conducted seminal studies in space medicine and inactivity physiology investigated why astronauts rapidly aged in space and lost muscle mass, bone density and developed a compromised immune system. As we get older, we are hooked on sitting, and this includes the weekends too. If you are wondering how to separate from your seat, there are ways to overcome this. In the research to prevent the deterioration caused by simulating the low gravity experience of astronauts, Dr. Joan Vernikos (2021) had earthbound volunteers lie down with the head slightly lower than the feet on a titled bed. She found that standing up from lying down every 30-minutes was enough to prevent the deterioration of inactivity, standing every hour was not enough to reverse the degeneration. Standing stimulated the baroreceptors in the neck and activated a cardiovascular response for optimal health (Vernikos, 2021).

We have forgotten something from our evolutionary background and childhood, which is to play and move around. When children move around, wiggle, and contort themselves in different positions, they maintain and increase their flexibility. Children can jump and move their arms up, down, side to side, forward, and backward. They do this every day, including the weekends.

When was the last time you played with a child or like a child? As an adult, we might feel tired to play with a child and it can be exhausting after staring at the screen all day. Instead of thinking of being tired to play with your child, consider it as a good workout. Then you and your child bond and hopefully they will also be ready for a nap. For you, not only do you move around and wake up those muscles that have not worked all day, you also relax the tight muscles, stretch and move your joints. Do playful activities that causes the body to move in unpredictable fun ways such as throwing a ball or roleplaying being a different animal. It will make both of you smile–smiling helps relaxation and rejuvenates your energy.