How effective is treatment? The importance of active placebos

Posted: December 16, 2017 Filed under: Pain/discomfort, placebo, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: Active placebo, Clinical trials, expectancy, hope, nocebo, passive placebo, placebo 3 CommentsAdapted by Erik Peper and Richard Harvey from: Peper, E. & Harvey, R. (2017). The fallacy of the placebo-controlled clinical trials: Are positive outcomes the result of “indirect” treatment effects? NeuroRegulation, 4(3–4), 102–113. http://dx.doi.org/10.15540/nr.4.3-4.102

How come some drugs or medical procedures are initially acclaimed to be beneficial and later ineffective or harmful and withdrawn from the market?

How come some patients with a cancer diagnosis experience symptom remission after receiving a placebo medication? Take the case of Mr. Wright. Several decades ago Dr. Klopher (1957) described Mr. Wright as a patient who had a generalized and far advanced malignancy in the form of a lymphosarcoma with an estimated life expectancy of less than two weeks. Following the diagnosis Mr. Wright read a newspaper article about a promising experimental cancer medication called Krebiozen and requested that he receive the latest treatment. Soon after receiving the drug, Mr. Wright had a complete remission of cancer symptoms with no signs of the deadly tumor. For over two months after receiving the new promising drug, Krebiozen, Mr. Wright engaged in a normal life and was even able to fly his own plane at 12,000 feet. After a promising introduction to the medication, Mr. Wright subsequently read another newspaper article which proved the new medication to be a useless, inert preparation. Confused and demoralized, the results of the wonder drug did not last and his symptoms returned. When the final AMA announcement was published “Nationwide tests show Krebiozen to be a worthless drug in treatment of cancer,” his symptoms became acute and he died within two days (Klopher, 1957).

The term placebo loosely translates as ‘I shall please you’ can be contrasted with the term nocebo which loosely translates as ‘I shall harm you’ when referring to exposure to a sham medication, treatment or procedure that results a positive outcome (placebo response), or a negative outcome (nocebo response), respectively. The responses a person has reflect a complex interaction between many processes. For example, when studying a placebo or nocebo response we measure internal psychological processes, measured in terms of a person’s self-reported attitudes, beliefs, cognitions and emotions; behavioral processes, measured overtly by observations of a person’s actions; and, physiological processes, measured more or less directly with instruments such as heart rate monitors, or biochemical analyses. Most relevant is that a person’s beliefs about the placebo (or nocebo) medication, treatment or procedure leads to predictable positive (or negative) behaviors and physiological benefits or harms.

The case of Mr. Wright illustrates that we may underestimate the positive power of the placebo or, the negative power of the nocebo, where Mr. Wright’s belief about the medication’s benefits first interacted in a positive way (placebo) with his behaviors (e.g. engaging in daily activities including flying an airplane) as well as his physiology (e.g. cancer remission) and unfortunately later, in a negative way (nocebo) interacting with his physiology (e.g. cancer return) contributing to his death.

The placebo response can be very powerful and healing. For example, watch the very dramatic demonstration of how the placebo response can be optimized in Derren Brown’s BBC video Fear and Faith Placebo https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y2XHDLuBZSw).

Placebo and nocebo effects are found in all therapeutic transactions when the communications between therapist and patient reflect embedded beliefs about the treatment. For example, patients have faith in clinician’s knowledge and belief that a prescribed medication is going to be effective at treating their symptoms, which then reinforces the patient’s belief in the medication, increasing indirect, embedded placebo effects, above and beyond any direct effects from the medication. The indirect effects of placebo responses have been most studied with medications; however, placebo effects are also studied in non-drug therapies. The research on placebo effects has demonstrated time and time again that when patients expect that the drug, surgery, or other therapeutic technique to be beneficial, then the patients tend to benefit more from the treatment.

The expectancy that the treatment will be effective at reducing symptoms is overtly, and covertly communicated by the health care professional during patient interactions, as well as by drug companies through direct to consumer advertising, and social media. The implied message is that the drug or procedure will improve symptoms, recovery or improve quality of life. On the other hand, if you do not do take the drug or do the procedure, your health will be compromised. For example, if you have high cholesterol, then take a statin drug to prevent the consequences of high cholesterol such as a heart attack or stroke. The implied message is that if you do not take it, you will die significantly sooner. Statins lower the risk for heart attacks; however, the benefits may be over stated. For people without prior heart disease, 60 people will have to take statins for 5 years to prevent 1 heart attack and 268 people to prevent 1 stroke. During the same time period 1 in 10 will experience muscle damage and 1 in 50 develop diabetes (theNNT, 2017 November).

If placebo and nocebo can have significant effects on medical outcome, how do you know if the treatment benefits are due to the direct effects of a drug or procedure or due to any indirect placebo effects or a combination of both?

The randomized controlled trial (RCT) is considered the gold standard method to determine the effectiveness of a drug or procedure. The ideal study would be a double blind, randomized, placebo controlled clinical trial in which neither the practitioner nor the patient would know who is getting what condition. For example, blinding implies the placebo group would receive a pill that appears identical to a ‘real’ pill, except the placebo has pharmacological ingredients. Similarly, a patient may receive an ‘exploratory’ surgery in which anesthesia is given and the skin is cut however the no further actual internal surgery occurs because the surgeon determined further internal surgery was unnecessary. Although, it is not possible to perform a double blind surgery study, the patient may be totally unaware whether an internal surgery had occurred.

Peper and Harvey (2017) point out that the positive findings of an ‘effective’ treatment are not always the results of the direct effects of medications and may be more attributable to indirect placebo responses. For example, patients may attribute the ‘effectiveness’ of the treatment to their experience of ‘non-directed’ treatment side effects that include: the post-surgical discomfort which signals to the patient that the procedure was successful, or a dry mouth and constipation that were caused by the antidepressant medication, which signals to the person that the trial medication or procedure-related medication is working (Bell, Rear, Cunningham, Dawnay, & Yellon, 2014; Stewart-Williams & Podd, 2004).

Just imagine the how pain can evoke totally different reactions. If you recently had a heart attack and then later experienced pain and cramping in the chest, you automatically may feel terrified as you could interpret the pain as another heart attack. The fear response to the pain may increase pathology and inhibit healing (a nocebo response). On the other hand, after bypass surgery, you may also experience severe pain when you move your chest. In this case, you interpret the pain as a sign that the bypass surgery was successful, which then reduces fear and reinforces the belief that you have survived a life threatening situation and will continue healing (placebo response).

Many research studies employ a placebo control, however what is less typical is a double-blind study using an ‘active’ placebo (Enck, Bingel, Schedlowski, & Rief, 2013). Less than 0.5% of all placebo studies include an active placebo group. (Shader, 2017; Jensen et al, 2017).

Unfortunately, a typical ‘placebo controlled’ study design is problematic for distinguishing the direct from any indirect (covert) placebo effects that occur within the study as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Normal (passive) placebo control group controls and experimental group. What is not assessed are placebo benefits induced by the medication/treatment induced side effects.

Figure 1. Normal (passive) placebo control group controls and experimental group. What is not assessed are placebo benefits induced by the medication/treatment induced side effects.

With a passive placebo, there is no way to know if the observed benefits are from the medication/medical procedure, or from the placebo/self-healing response triggered by the medication/medical procedure (or both combined, or neither the placebo or medical procedure). The best way to know if the treatment is actually beneficial is to use an ‘active’ placebo instead of a passive placebo.

An active placebo builds on a patient’s attributions about a medication or medical procedure. For example, a patient may be told by a clinician that feeling any side effects such as insomnia, a racing heart or, experiencing a warm flushing feeling will let them know the medication is working, so the patient becomes conditioned to expect the medication is working when they feel or experience side effects. Whereas a passive (inert) placebo such as a sugar pill will have effects that are extremely subtly felt or experienced, an active placebo will have effects that are more overtly felt or experienced. Examples of active placebos include administering low doses of caffeine or niacin that have effects which may be felt internally however which do not have the same effects as the medication. When a patient is told they may have side effects from the medication that include felt changes in heart rate or a flushing feeling, the patient attributes the changes they feel to a medication they believe will bring about benefits, even though the changes are rightfully attributed to the caffeine or niacin in the active placebo.

An active placebo triggers observed and felt body changes which do not affect the actual illness. For surgical procedures, an ‘active’ placebo control would be a sham/mock surgery in which the patient would undergo the same medical procedure (e.g. external surgery incision) without continuing some internal surgical procedure (Jonas et al, 2015). In numerous cases of accepted surgery, such as the Vineberg procedure (Vineburg & Miller, 1951) for angina, or arthroscopic knee surgery for treating osteoarthritis, the clinical benefits of a sham/mock surgery were just as successful as the actual surgery. Similar studies suggest the clinical benefits were solely (or primarily) due directly to the placebo response (Beecher, 1961; Cobb et al, 1959; Moseley et al, 2002).

To persuasively demonstrate that a treatment or therapeutic procedure is effective it should incorporate a study design using an active placebo arm as shown in Figure 2. Figure 2. Active placebo control group controls for the normal placebo benefits plus those placebo benefits induced by the medication/treatment induced side effects.

Figure 2. Active placebo control group controls for the normal placebo benefits plus those placebo benefits induced by the medication/treatment induced side effects.

Some treatments may be less effective then claimed because they were not compared to an active placebo, which could be one of the reasons why so many medical and psychological studies cannot be replicated. The absence of ‘active’ placebo controls may also be a factor explaining why some respected authorities have expressed some doubt about published scientific medical research results. Following are two quotes that illustrate such skepticism.

“Much of the scientific literature, perhaps half, may simply be untrue.” —Richard Horton, editor-in-chief of the Lancet (Horton, 2015).

“It is simply no longer possible to believe much of the clinical research that is published, or to rely on the judgment of trusted physicians or authoritative medical guidelines. I take no pleasure in this conclusion, which I reached slowly and reluctantly over my two decades as an editor of the New England Journal of Medicine” —Dr. Marcia Angell, longtime Editor in Chief of the New England Medical Journal (Angell, 2009).

There are a variety of questions to ask before agreeing on a procedure or before taking medication

A quick way to ask whether a medication or medical treatment effectiveness is the result of placebo components is to ask the following questions:

- Have there been successful self-care or behavioral approaches beyond surgical or pharmaceutical treatments that have demonstrated effectiveness? When successful treatments are reported, then questions are raised whether pharmaceutical or surgical outcomes are also attributable to the result of placebo effects. On the other hand, if there a no successful self-care approaches, then the benefits may be more due to the direct therapeutic effect of a surgical procedure or medication.

- Has the procedure been compared to an active placebo control? If not, then to what extent it is possible that the results of the surgical or pharmaceutical therapy could be attributed to a placebo response instead of directly to the medication or surgery?

- What are the long term benefits and complication rates of the medication, treatment or procedure? When benefits are low and risks of the procedure are high, explore the risks associated with ‘watchful waiting’ (Colloca, Pine, Ernst, Miller & Grillon, 2016; Thomas et al, 2014; Taleb, 2012).

Unfortunately, most clinical studies that includes pharmaceuticals and/or surgery do not test their medication, surgery against an ‘active’ placebo. Whenever possible, enquire whether an active placebo was used to determine the degree of effectiveness of the proposed treatment or procedure. Fortunately, the design of ‘active’ placebo-controlled studies is very possible for anyone interested in comparing the effectiveness of medications, treatments and procedures in various settings, from hospitals and clinics to university classrooms and individual homes.

In summary, the benefits of the treatment must significantly outweigh any risks of negative treatment side effects. Short-term treatment benefits need to be balanced by any long-term benefits. Unfortunately, short-term benefits may lead to significant, long-term harm such as in the use of some medications (e.g. sleep medications, opioid pain killers) that result in chronic dependency and which lead to a significant increase in morbidity and mortality of many kinds. We suggest that more medications and other procedures are tested against an active placebo to investigate whether the medication or procedure is actually effective.

For a detailed analysis and discussion of placebo and the importance of active placebo see our article, Peper, E. & Harvey, R. (2017). The fallacy of the placebo-controlled clinical trials: Are positive outcomes the result of “indirect” treatment effects? NeuroRegulation, 4(3–4), 102–113. http://dx.doi.org/10.15540/nr.4.3-4.102

References:

Angell M. Drug companies and doctors: A story of corruption. January 15, 2009. The New York Review of Books 56. Available: http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2009/jan/15/drug-companies-doctorsa-story-of-corruption/. Accessed 24, November, 2016.

Beecher, H. K. (1961). Surgery as placebo: A quantitative study ofbias. JAMA, 176(13), 1102–1107. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.1961.63040260007008

Bell, R. M., Rear, R., Cunningham, J., Dawnay, A., & Yellon, D. M. (2014). Effect of remote ischaemic conditioning on contrast-induced nephropathy in patients undergoing elective coronary angiography (ERICCIN): rationale and study design of a randomised single-centre, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Clinical Research in Cardiology, 103(3), 203-209. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00392-013-0637-3

Cobb, L. A., Thomas, G. I., Dillard, D. H., Merendino, K. A., & Bruce, R. A. (1959). An evaluation of internal-mammary-artery ligation by a double-blind technic. New England Journal of Medicine, 260(22), 1115–1118. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM195905282602204

Colloca, L., Pine, D. S., Ernst, M., Miller, F. G., & Grillon, C. (2016). Vasopressin boosts placebo analgesic effects in women: A randomized trial. Biological Psychiatry, 79(10), 794–802. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.07.019

Derren Brown’s BBC video Fear and Faith Placebo https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y2XHDLuBZSw

Enck, P., Bingel, U., Schedlowski, M., & Rief, W. (2013). The placebo response in medicine: minimize, maximize or personalize?. Nature reviews Drug discovery, 12(3), 191-204. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrd3923

Horton, R. (2015). Offline: What is medicine’s 5 sigma. The Lancet, 385(9976), 1380. http://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/lancet/PIIS0140-6736%2815%2960696-1.pdf

Jensen, J. S., Bielefeldt, A. Ø., & Hróbjartsson, A. (2017). Active placebo control groups of pharmacological interventions were rarely used but merited serious consideration: A methodological overview. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.03.001

Jonas, W. B., Crawford, C., Colloca, L., Kaptchuk, T. J., Moseley, B., Miller, F. G., & Meissner, K. (2015). To what extent are surgery and invasive procedures effective beyond a placebo response? A systematic review with meta-analysis of randomised, sham controlled trials. BMJ open, 5(12), e009655. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009655

Klopfer, B., (1957). Psychological Variables in Human Cancer, Journal of Projective Techniques, 21(4), 331–340. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/08853126.1957.10380794

Moseley, J. B., O’Malley, K., Petersen, N. J., Menke, T. J., Brody, B. A., Kuykendall, D. H., … Wray, N. P. (2002). A controlled trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. The New England Journal of Medicine. 347(2), 81–88. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056 /NEJMoa013259

Peper, E. & Harvey, R. (2017). The fallacy of the placebo-controlled clinical trials: Are positive outcomes the result of “indirect” treatment effects? NeuroRegulation, 4(3–4), 102–113. http://dx.doi.org/10.15540/nr.4.3-4.102

Shader, R. I. (2017). Placebos, Active Placebos, and Clinical Trials. Clinical Therapeutics, 39(3), 451–454. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2017.02.001

Stewart-Williams, S., & Podd, J. (2004). The placebo effect: dissolving the expectancy versus conditioning debate. Psychological bulletin, 130(2), 324. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.2.324

Taleb, N. N. (2012). Antifragile: Things that gain from disorder. Random House.

TheNNT (2017, November). http://www.thennt.com/nnt/statins-for-heart-disease-prevention-without-prior-heart-disease/

Thomas, R., Williams, M., Sharma, H., Chaudry, A., & Bellamy, P. (2014). A double-blind, placebo-controlled randomised trial evaluating the effect of a polyphenol-rich whole food supplement on PSA progression in men with prostate cancer—the UK NCRN Pomi-T study. Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases, 17(2), 180–186. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/pcan.2014.6

Vineberg, A., & Miller, G. (1951). Treatment of coronary insufficiency. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 64(3), 204. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1821866/pdf/canmedaj00654-0019.pdf

Overcoming obstacles

Posted: December 8, 2017 Filed under: self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: deaf, healing, Inspiration, paraplegia, public speaking, singing 1 CommentIn a world with so much violence, inequalities and overwhelming negative news, it is easy to feel discouraged and forget that people can overcome trauma. Take charge of the news and images that surround us since the sounds and images impact our brain. Instead of watching disheartening and violent news before going to sleep, inspire yourself by watching the following two videos.

Muniba Mazari who at age 21 sustained spinal cord damage which left her paraplegic. She is an activist, motivational speaker and television host. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=btb9wLkiKPE

Mandy Harvey who at age nineteen lost her hearing and is an outstanding American pop singer and songwriter. Even though she is deaf, she received Simon’s Golden Buzzer in America’s Got Talent 2017 while singing her original song. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZKSWXzAnVe0

Posture and mood: implications and applications to health and therapy

Posted: November 28, 2017 Filed under: Neck and shoulder discomfort, posture, self-healing, Uncategorized | Tags: back pain, electromyography, ergonomics, neck and shoulder tension, posture, spinal alignment, stress management 7 CommentsThis blog has been reprinted from: Peper, E., Lin, I-M, & Harvey, R. (2017). Posture and mood: Implications and applications to therapy. Biofeedback.35(2), 42-48.

Slouched posture is very common and tends to increase access to helpless, hopeless, powerless and depressive thoughts as well as increased head, neck and shoulder pain. Described are five educational and clinical strategies that therapists can incorporate in their practice to encourage an upright/erect posture. These include practices to experience the negative effects of a collapsed posture as compared to an erect posture, watching YouTube video to enhance motivation, electromyography to demonstrate the effect of posture on muscle activity, ergonomic suggestions to optimize posture, the use of a wearable posture biofeedback device, and strategies to keep looking upward. When clients implement these changes, they report a more positive outlook and reduced neck and shoulder discomfort.

Background

Most people slouch without awareness when looking at their cellphone, tablet, or the computer screen (Guan et al., 2016) as shown in Figure 1. Many clients in psychotherapy and in biofeedback or neurofeedback training experience concurrent rumination and depressive thoughts with their physical symptoms. In most therapeutic sessions, clients sit in a comfortable chair, which automatically creates a posterior pelvic tilt and encourages the spine to curve so that the client sits in a slouched position. While at home, they sit on an easy chair or couch, which lets them slouch as they watch TV or surf the web.

Figure 1. (A). Employee working on his laptop. (B). Boy with ADHD being trained with neurofeedback in a clinic. (C). Student looking at cell phone. When people slouch and look at the screen, they tend to slouch and scrunch their neck.

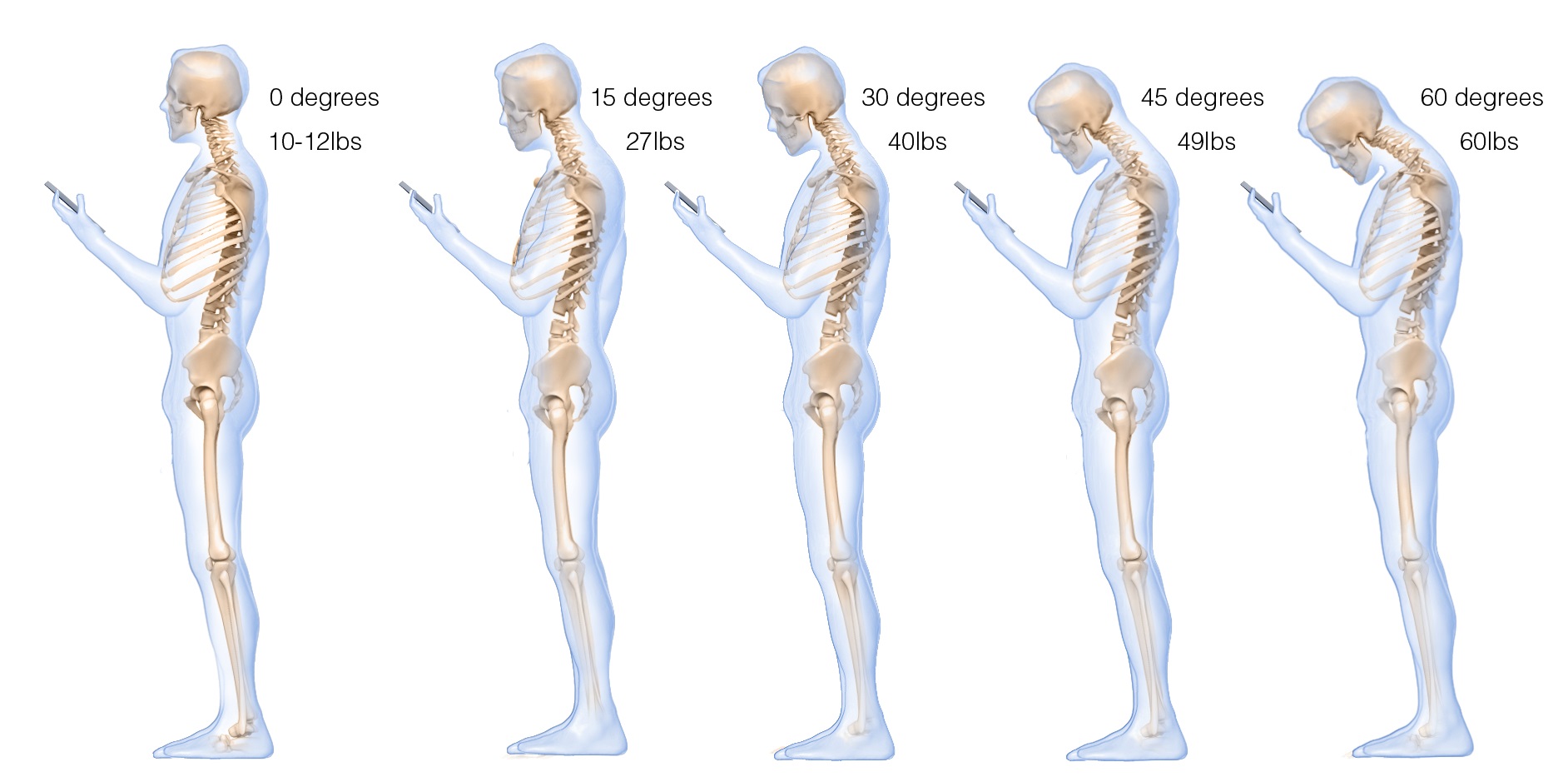

In many cases, the collapsed position also causes people to scrunch their necks, which puts pressure on their necks that may contribute to developing headache or becoming exhausted. Repetitive strain on the neck and cervical spine may trigger a cervical neuromuscular syndrome that involves chronic neck pain, autonomic imbalance and concomitant depression and anxiety (Matsui & Fujimoto, 2011), and may contribute to vertebrobasilar insufficiency –a reduction in the blood supply to the hindbrain through the left and right vertebral arteries and basilar arteries (Kerry, Taylor, Mitchell, McCarthy, & Brew, 2008). From a biomechanical perspective, slouching also places more stress is on the cervical spine, as shown in Figure 2. When the neck compression is relieved, the symptoms decrease (Matsui & Fujimoto, 2011).

Figure 2. The more the head tilts forward, the more stress is placed on the cervical spine. Reproduced by permission from: Hansraj, K. K. (2014). Assessment of stresses in the cervical spine caused by posture and position of the head. Surgical Technology International, 25, 277–279.

Figure 2. The more the head tilts forward, the more stress is placed on the cervical spine. Reproduced by permission from: Hansraj, K. K. (2014). Assessment of stresses in the cervical spine caused by posture and position of the head. Surgical Technology International, 25, 277–279.

Most people are totally unaware of slouching positions and postures until they experience neck, shoulder, and/or back discomfort. Neither clients nor therapists are typically aware that slouching may decrease energy levels and increase the prevalence of negative (hopeless, helpless, powerless, or defeated) memories and thoughts (Peper & Lin, 2012; Peper et al, 2017)

Recommendations for posture awareness and training in treatment/education

The first step in biofeedback training and therapy is to systematically increase awareness and training of posture before attempting further bio/neurofeedback training and/or cognitive behavior therapy. If the client is sitting in a collapsed position in therapy, then it will be much more difficult for them to access positive thoughts, which interferes with further training and effective therapy. For example, research by Tsai, Peper, & Lin (2016) showed that engaging in positive thinking while slouched requires greater mental effort then when sitting erect. Sitting erect and tall contributes to elevated mood and positive thinking. An upright posture supports positive outcomes that may be akin to the beneficial effects of exercise for the treatment of depression (Schuch, Vancampfort, Richards, Rosenbaum, Ward, & Stubbs., 2016).

Most people know that posture affects health; however, they are unaware of how rapidly a slouching posture can impact their physical and mental health. We recommend the following educational and clinical strategies to teach this awareness.

- Practicing activities that raise awareness about a collapsed posture as compared to an erect posture

Guide clients through the practices so that they experience how posture can affect memory recall, physical strength, energy level, and possible triggering of headaches.

A. The effect of collapsed and erect posture on memory recall. Participants reported that it is much easier evoke powerless, hopeless, helpless, and defeated memories when sitting in a collapsed position than when sitting upright. Guide the client through the procedure described in the article, How posture affects memory recall and mood (Peper, Lin, Harvey, and Perez, 2017) and in the blog Posture affects memory recall and mood.

B. The effects of collapsed and erect posture on perceived physical strength. Participants experience much more difficulty in resisting downward pressure at the wrist of an outstretched arm when slouched rather than upright. Guide the client through the exercise described in the article, Increase strength and mood with posture (Peper, Booiman, Lin, & Harvey, 2016) and the blog, Increase strength and mood with posture.

C. The effect of slouching versus skipping on perceived energy levels. Participants experience a significant increase in subjective energy after skipping than walking slouched. Guide the client through the exercises as described in the article, Increase or decrease depression—How body postures influence your energy level (Peper & Lin, 2012).

D. The effect of neck compression to evoke head pressure and headache sensations. In our unpublished study with students and workshop participants, almost all participants who are asked to bring their head forward, then tilt the chin up and at the same time compress the neck (scrunching the neck), report that within thirty seconds they feel a pressure building up in the back of the head or the beginning of a headache. To their surprise, it may take up to 5 to 20 minutes for the discomfort to disappear. Practicing similar awareness activities can be a useful demonstration for clients with dizziness or headaches to experience how posture can increase their symptoms.

- Watching a Youtube video to enhance motivation.

Have clients watch Professor Amy Cuddy’s 2012 TED (Technology, Entertainment, and Design) Talk, Your body language shape who you are, which describes the hormonal changes that occur when adapting a upright power versus collapsed defeated posture.

- Electromyographic (EMG) feedback to demonstrate how posture affects muscle activity.

Record EMG from muscles such as around the cervical spine, trapezius, frontalis, and masseters or beneath the chin (submental lead) to demonstrate that having the head is forward and/or the neck compressed will increase EMG activity, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Electromyographic recording of the muscle under the chin while alternating between bringing the head forward or holding it back, feeling erect and tall.

The client can then learn awareness of the head and neck position. For example, one client with severe concussion experienced significant increase in head pressure and dizziness when she slouched or looked at a computer screen as well as feeling she would never get better. She then practiced the exercise of alternating her awareness by bringing her head forward and then back, and then bringing her neck back while her chin was down, thereby elongating the neck while she continued to breathe. With her head forward, she would feel her molars touching and with her neck back she felt an increase in space between the molars. When she elongated her neck in an erect position, she felt the pressure draining out of her head and her dizziness and tinnitus significantly decrease.

- Assessing ergonomics to optimize posture.

Change the seated posture of both the therapist and the client during treatment and training. Although people may be aware of their posture, it is much easier to change the external environment so that they automatically sit in a more erect power posture. Possible options include:

A. Seat insert or cushions. Sit in upright chairs that encourage an anterior pelvic tilt by having the seat pan slightly lower in the front than in the back or using a seat insert to facilitate a more erect posture (Schwanbeck, Peper, Booiman, Harvey, & Lin, 2015) as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. An example of how posture can be impacted covertly when one sits on a seat insert that rotates the pelvis anteriorly (The seat insert shown in the diagram and used in research is produced by BackJoy™).

B. Back cushion. Place a small pillow or rolled up towel at the kidney level so that the spine is slight arched, instead of sitting collapsed, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. An example of how a small pillow, placed between the back of the chair and the lower back, changes posture from collapsed to erect.

Figure 5. An example of how a small pillow, placed between the back of the chair and the lower back, changes posture from collapsed to erect.

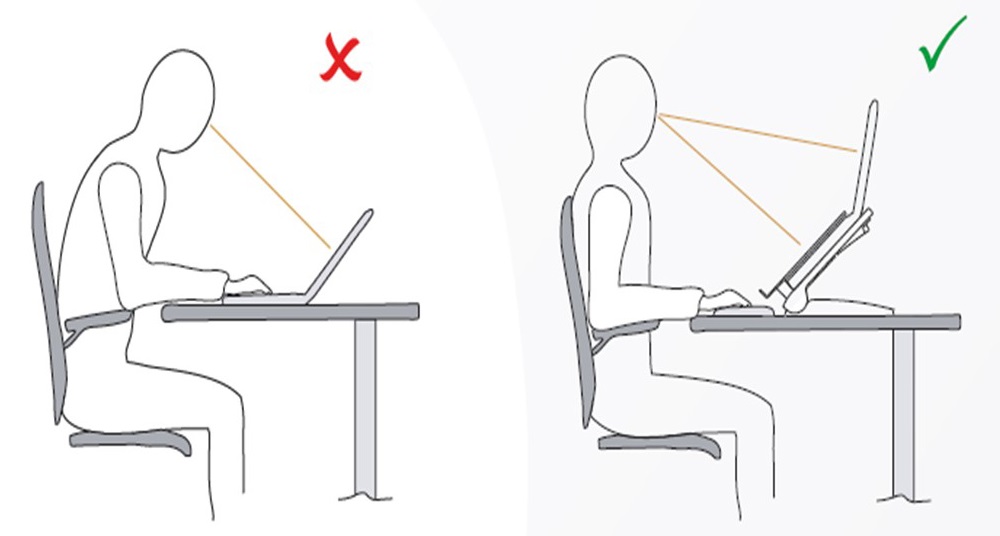

C. Check ergonomic and work site computer use to ensure that the client can sit upright while working at the computer. For some, that means checking their vision if they tend to crane forward and crunch their neck to read the text. For those who work on laptops, it means using either an external keyboard, a monitor, or a laptop stand so the screen is at eye level, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Posture is collapsed when working on a laptop and can be improved by using an external keyboard and monitor. Reproduced by permission from: Bakker Elkhuizen. (n.d.). Office employees are like professional athletes! (2017).

Figure 6. Posture is collapsed when working on a laptop and can be improved by using an external keyboard and monitor. Reproduced by permission from: Bakker Elkhuizen. (n.d.). Office employees are like professional athletes! (2017).

- Wearable posture biofeedback training device

The wearable biofeedback device, UpRight™, consists of a small sensor placed on the spine and works as an app on the cell phone. After calibration the erect and slouched positions, the posture device gives vibratory feedback each time the participant slouches, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Illustration of a posture feedback device, UpRight™. It provides vibratory feedback to the wearer to indicate that they are beginning to slouch.

Clinically, we have observed that clients can learn to identify conditions that are associated with slouching, such as feeling tired, thinking depressive/hopeless thoughts or other situations that evoke slouching. When people wear a posture feedback device during the day, they rapidly become aware of these subjective experiences whenever they slouch. The feedback reminds them to sit in an erect position, and they subsequently report an improvement in health (Colombo et al., 2017). For example, a 26-year-old man who works more than 8 hours a day on computer reported, “I have an improved awareness of my posture throughout my day. I also notice that I had less back pain at the end of the day.”

- Integrating posture awareness and position changes throughout the day

After clients have become aware of their posture, additional training included having them observe their posture as well and negative changes in mood, energy level or tension in their neck and head. When they become aware of these changes, they use it as a cue to slightly arch their back and look upward. If possible have the clients look outside at the tops of trees and notice details such as how the leaves and branches move. Looking at the details interrupts any ongoing rumination. At the same time, have them think of an uplifting positive memory. Then have them take another breath, wiggling, and return to the task at hand. Recommend to clients to go outside during breaks and lunchtime to look upward at the trees, the hills, or the clouds. Each time one is distracted, return to appreciate the natural patterns. This mental break concludes by reminding oneself that humans are like trees.

Trees are rooted in the earth and reach upward to the light. Despite the trauma of being buffeted by the storms, they continue to reach upward. Similarly, clouds reflect the natural beauty of the world, and are often visible in the densest city environment. The upward movement reflects our intrinsic resilience and growth. –Erik Peper

Have clients place family photos and art slightly higher on the wall at home so they automatically look upward to see the pictures. A similar strategy can be employed in the office, using art to evoke positive feelings. When clients integrate an erect posture into their daily lives, they experience a more positive outlook and reduced neck and shoulder discomfort.

Compliance with Ethical Standards:

Conflict of Interest: Author Erik Peper has received donations of 15 UpRight posture feedback devices from UpRight (http://www.uprightpose.com/) and 12 BackJoy seat inserts from Backjoy (https://www.backjoy.com) for use in research. Co-authors I-Mei Lin and Richard Harvey declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This report evaluated a convenience sample of a student classroom activity related to posture and the information was anonymous collected. As an evaluation of a classroom activity, this report of findings was exempted from Institutional Review Board oversight

References:

Bakker Elkhuizen. (n.d.). Office employees are like professional athletes! (2017). Retrieved from https://www.bakkerelkhuizen.com/knowledge-center/whitepaper-improving-work-performance-with-insights-from-pro-sports/

Cuddy, A. (2012). Your body language shapes who you are. Technology, Entertainment, and Design (TED) Talk, available at: www.ted.com/talks/amy_cuddy_your_body_language_shapes_who_you_are

We thank Frank Andrasik for his constructive comments.

Posture affects memory recall and mood

Posted: November 25, 2017 Filed under: Exercise/movement, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: cognitive therapy, depression, empowerment, energy, helplessness, memory, mood, posture, power posture, somatics 5 CommentsThis blog has been reprinted from: Peper, E., Lin, I-M., Harvey, R., & Perez, J. (2017). How posture affects memory recall and mood. Biofeedback, 45 (2), 36-41.

When I sat collapsed looking down, negative memories flooded me and I found it difficult to shift and think of positive memories. While sitting erect, I found it easier to think of positive memories. -Student participant

The link between posture and mood is embedded in idiomatic phrases such as walking tall, standing proud, and an upstanding citizen, versus collapsed, defeated, or in a slump–Language suggests that posture and mood/emotions are connected. Slumped posture is commonly observed in depression (Canales et al., 2010; Michalak et al., 2009) and adapting an upright posture increases positive affect, reduces fatigue, and increases energy in people with mild to moderate depression (Wilkes et al., 2017; Peper & Lin, 2012).

The link between posture and mood is embedded in idiomatic phrases such as walking tall, standing proud, and an upstanding citizen, versus collapsed, defeated, or in a slump–Language suggests that posture and mood/emotions are connected. Slumped posture is commonly observed in depression (Canales et al., 2010; Michalak et al., 2009) and adapting an upright posture increases positive affect, reduces fatigue, and increases energy in people with mild to moderate depression (Wilkes et al., 2017; Peper & Lin, 2012).

This blog describes in detail our research study that demonstrated how posture affects memory recall (Peper et al, 2017). Our findings may explain why depression is increasing the more people use cell phones. More importantly, learning posture awareness and siting more upright at home and in the office may be an effective somatic self-healing strategy to increase positive affect and decrease depression.

Background

Most psychotherapies tend to focus on the mind component of the body-mind relationship. On the other hand, exercise and posture focus on the body component of the mind/emotion/body relationship. Physical activity in general has been demonstrated to improve mood and exercise has been successfully used to treat depression with lower recidivism rates than pharmaceuticals such as sertraline (Zoloft) (Babyak et al., 2000). Although the role of exercise as a treatment strategy for depression has been accepted, the role of posture is not commonly included in cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) or biofeedback or neurofeedback therapy.

The link between posture, emotions and cognition to counter symptoms of depression and low energy have been suggested by Wilkes et al. (2017) and Peper and Lin (2012), . Peper and Lin (2012) demonstrated that if people tried skipping rather than walking in a slouched posture, subjective energy after the exercise was significantly higher. Among the participants who had reported the highest level of depression during the last two years, there was a significant decrease of subjective energy when they walked in slouched position as compared to those who reported a low level of depression. Earlier, Wilson and Peper (2004) demonstrated that in a collapsed posture, students more easily accessed hopeless, powerless, defeated and other negative memories as compared to memories accessed in an upright position. More recently, Tsai, Peper, and Lin (2016) showed that when participants sat in a collapsed position, evoking positive thoughts required more “brain activation” (i.e. greater mental effort) compared to that required when walking in an upright position.

Even hormone levels also appear to change in a collapsed posture (Carney, Cuddy, & Yap, 2010). For example, two minutes of standing in a collapsed position significantly decreased testosterone and increased cortisol as compared to a ‘power posture,’ which significantly increased testosterone and decreased cortisol while standing. As Professor Amy Cuddy pointed out in herTechnology, Entertainment and Design (TED) talk, “By changing posture, you not only present yourself differently to the world around you, you actually change your hormones” (Cuddy, 2012). Although there appears to be controversy about the results of this study, the overall findings match mammalian behavior of dominance and submission. From my perspective, the concepts underlying Cuddy’s TED talk are correct and are reconfirmed in our research on the effect of posture. For more detail about the controversy, see the article by Susan Dominusin in the New York Times, “When the revolution came for Amy Cuddy,”, and Amy Cuddy’s response (Dominus, 2017;Singal and Dahl, 2016).

The purpose of our study is to expand on our observations with more than 3,000 students and workshop participants. We observed that body posture and position affects recall of emotional memory. Moreover, a history of self-described depression appears to affect the recall of either positive or negative memories.

Method

Subjects: 216 college students (65 males; 142 females; 9 undeclared), average age: 24.6 years (SD = 7.6) participated in a regularly planned classroom demonstration regarding the relationship between posture and mood. As an evaluation of a classroom activity, this report of findings was exempted from Institutional Review Board oversight.

Procedure

While sitting in a class, students filled out a short, anonymous questionnaire, which asked them to rate their history of depression over the last two years, their level of depression and energy at this moment, and how easy it was for them to change their moods and energy level (on a scale from 1–10). The students also rated the extent they became emotionally absorbed or “captured” by their positive or negative memory recall. Half of the students were asked to rate how they sat in front of their computer, tablet, or mobile device on a scale from 1 (sitting upright) to 10 (completely slouched).

Two different sitting postures were clearly defined for participants: slouched/collapsed and erect/upright as shown in Figure 1. To assume the collapsed position, they were asked to slouch and look down while slightly rounding the back. For the erect position, they were asked to sit upright with a slight arch in their back, while looking upward.

Figure 1. Sitting in a collapsed position and upright position (photo by Jana Asenbrennerova). Reprinted by permission from Gorter and Peper (2011).

Figure 1. Sitting in a collapsed position and upright position (photo by Jana Asenbrennerova). Reprinted by permission from Gorter and Peper (2011).

After experiencing both postures, half the students sat in the collapsed position while the other half sat in the upright position. While in this position, they were asked to recall/evoke as many hopeless, helpless, powerless, or defeated memories as possible, one after the other, for 30 seconds.

After 30 seconds they were reminded to keep their same position and let go of thinking negative memories. They were then asked to recall/evoke only positive, optimistic, or empowering memories for 30 seconds.

They were then asked to switch positions. Those who were collapsed switched to sitting erect, and those who were erect switched to sitting collapsed. Then they were again asked to recall/evoke as many hopeless, helpless, powerless, or defeated memories as possible one after the other for 30 seconds. After 30 seconds they were reminded to keep their same position and again let go of thinking of negative memories. They were then asked to recall/evoke only positive, optimistic, or empowering memories for 30 seconds, while still retaining the second posture.

They then rated their subjective experience in recalling negative or positive memories and the degree to which they were absorbed or captured by the memories in each position, and in which position it was easier to recall positive or negative experiences.

Results

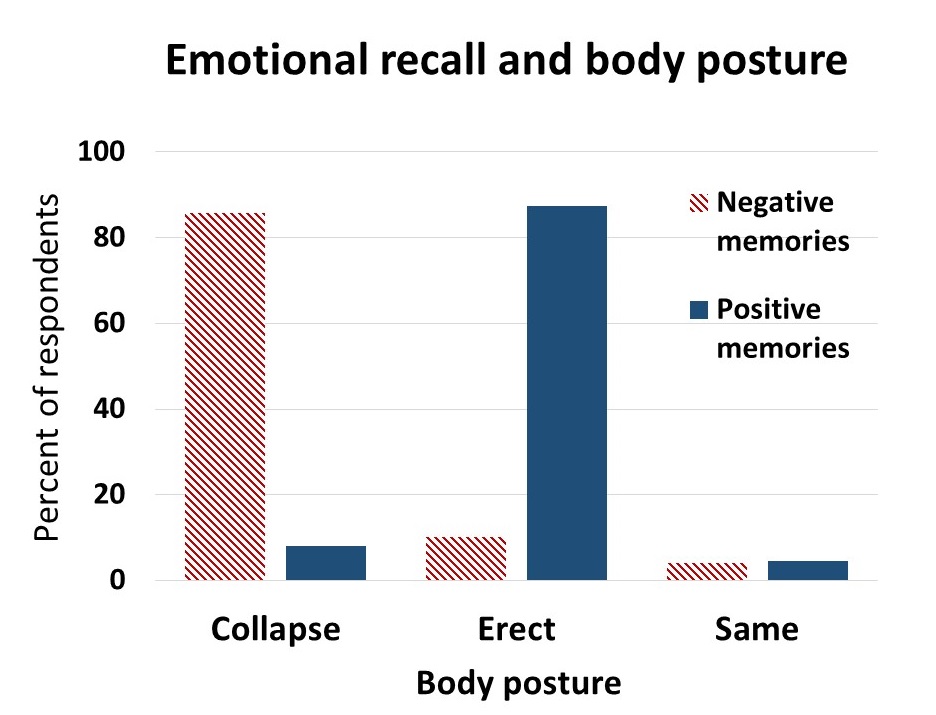

86% of the participants reported that it was easier to recall/access negative memories in the collapsed position than in the erect position, which was significantly different as determined by one-way ANOVA (F(1,430)=110.193, p < 0.01) and 87% of participants reported that it was easier to recall/access positive images in the erect position than in the collapsed position, which was significantly different as determined by one-way ANOVA (F(1,430)=173.861, p < 0.01) as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Percent of respondents who reported that it was easier to recall positive or negative memories in an upright or slouched posture.

Figure 2. Percent of respondents who reported that it was easier to recall positive or negative memories in an upright or slouched posture.

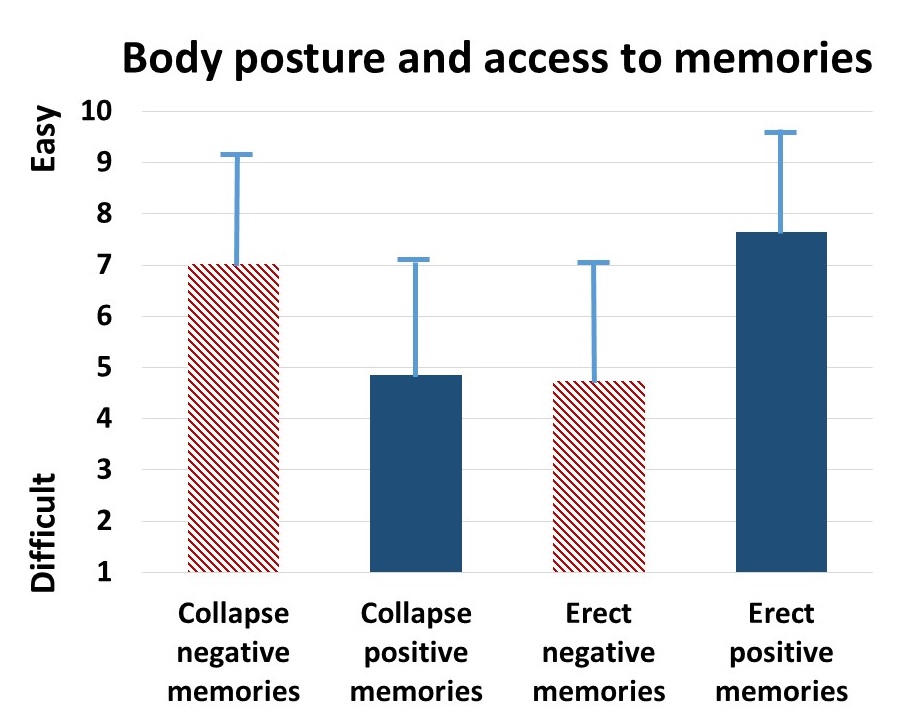

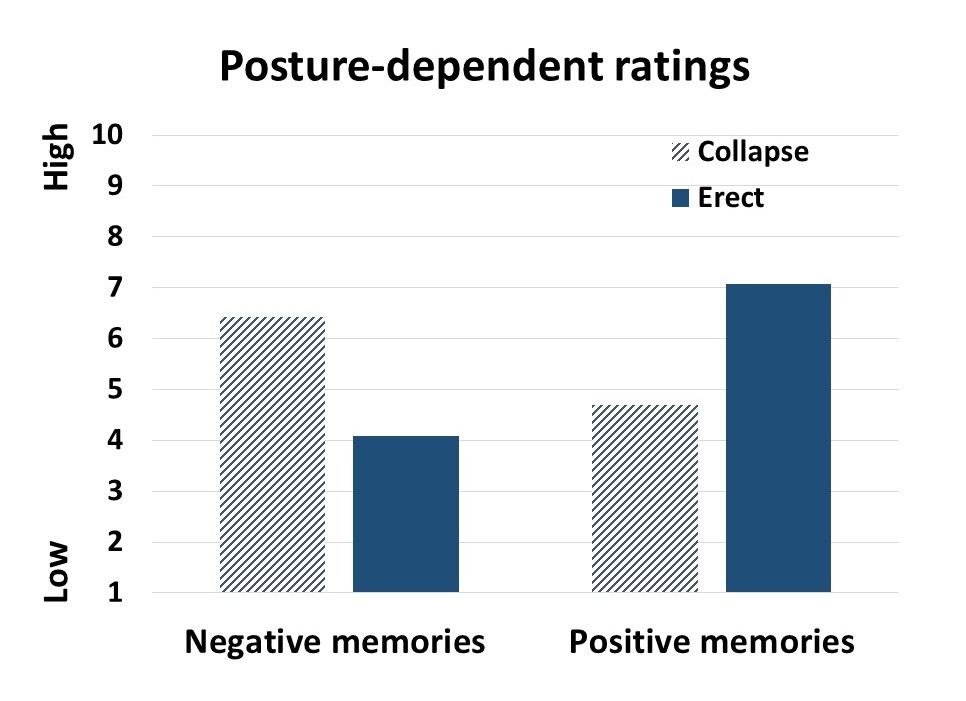

The difficulty or ease of recalling negative or positive memories varied depending on position as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. The relative subjective rating in the ease or difficulty of recalling negative and positive memories in collapsed and upright positions.

Figure 3. The relative subjective rating in the ease or difficulty of recalling negative and positive memories in collapsed and upright positions.

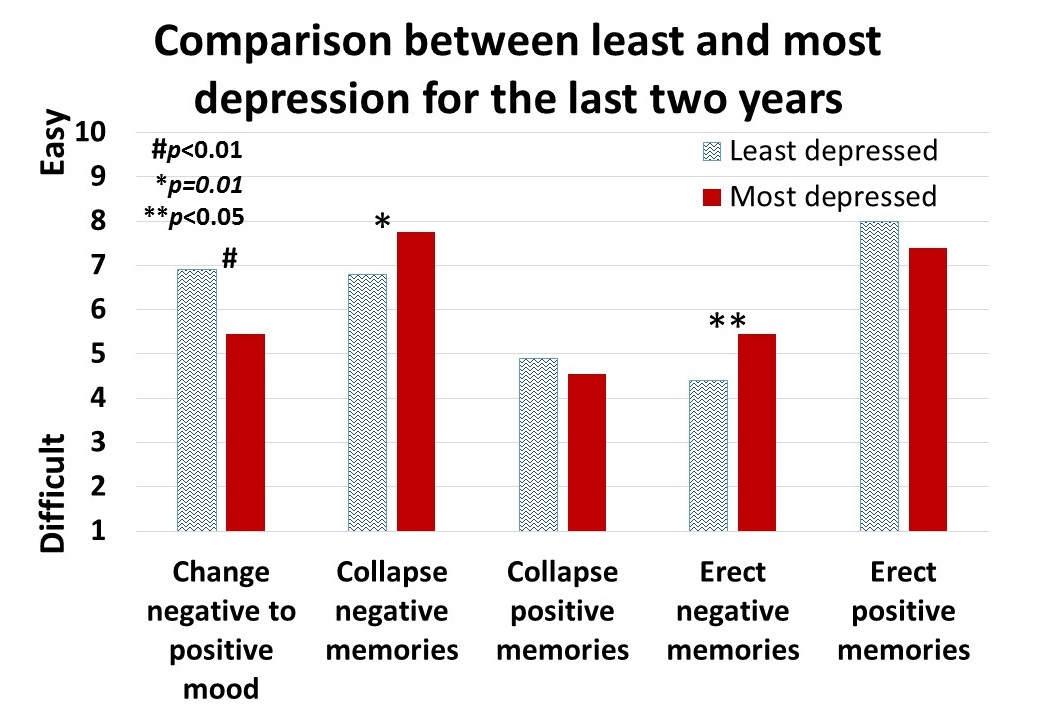

The participants with a high level of depression over the last two years (top 23% of participants who scored 7 or higher on the scale of 1–10) reported that it was significantly more difficult to change their mood from negative to positive (t(110) = 4.08, p < 0.01) than was reported by those with a low level of depression (lowest 29% of the participants who scored 3 or less on the scale of 1–10). It was significantly easier for more depressed students to recall/evoke negative memories in the collapsed posture (t(109) = 2.55, p = 0.01) and in the upright posture (t(110) = 2.41, p ≦0.05 he) and no significant difference in recalling positive memories in either posture, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Differences is in memory access for participants with a history of least or most depression.

Figure 4. Differences is in memory access for participants with a history of least or most depression.

For all participants, there was a significant correlation (r = 0.4) between subjective energy level and ease with which they could change from negative to positive mood. There were no significance differences for gender in all measures except that males reported a significantly higher energy level than females (M = 5.5, SD = 3.0 and M = 4.7, SD = 3.8, respectively; t(203) = 2.78, p < 0.01).

A subset of students also had rated their posture when sitting in front of a computer or using a digital device (tablet or cell phone) on a scale from 1 (upright) to 10 (completely slouched). The students with the highest levels of depression over the last two years reporting slouching significantly more than those with the lowest level of depression over the last two years (M = 6.4, SD = 3.5 and M = 4.6, SD = 2.6; t(46) = 3.5, p < 0.01).

There were no other order effects except of accessing fewer negative memories in the collapsed posture after accessing positive memories in the erect posture (t(159)=2.7, p < 0.01). Approximately half of the students who also rated being “captured” by their positive or negative memories were significantly more captured by the negative memories in the collapsed posture than in the erect posture (t(197) = 6.8, p < 0.01) and were significantly more captured by positive memories in the erect posture than the collapsed posture (t(197) = 7.6, p < 0.01), as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Subjective rating of being captured by negative and positive memories depending upon position.

Figure 5. Subjective rating of being captured by negative and positive memories depending upon position.

Discussion

Posture significantly influenced access to negative and positive memory recall and confirms the report by Wilson and Peper (2004). The collapsed/slouched position was associated with significantly easier access to negative memories. This is a useful clinical observation because ruminating on negative memories tends to decrease subjective energy and increase depressive feelings (Michi et al., 2015). When working with clients to change their cognition, especially in the treatment of depression, the posture may affect the outcome. Thus, therapists should consider posture retraining as a clinical intervention. This would include teaching clients to change their posture in the office and at home as a strategy to optimize access to positive memories and thereby reduce access or fixation on negative memories. Thus if one is in a negative mood, then slouching could maintain this negative mood while changing body posture to an erect posture, would make it easier to shift moods.

Physiologically, an erect body posture allows participants to breathe more diaphragmatically because the diaphragm has more space for descent. It is easier for participants to learn slower breathing and increased heart rate variability while sitting erect as compared to collapsed, as shown in Figure 6 (Mason et al., 2017).

Figure 6. Effect of posture on respiratory breathing pattern and heart rate variability.

Figure 6. Effect of posture on respiratory breathing pattern and heart rate variability.

The collapsed position also tends to increase neck and shoulder symptoms This position is often observed in people who work at the computer or are constantly looking at their cell phone—a position sometimes labeled as the i-Neck.

Implication for therapy

In most biofeedback and neurofeedback training sessions, posture is not assessed and clients sit in a comfortable chair, which automatically causes a slouched position. Similarly, at home, most clients sit on an easy chair or couch, which lets them slouch as they watch TV or surf the web. Finally, most people slouch when looking at their cellphone, tablet, or the computer screen (Guan et al., 2016). They usually only become aware of slouching when they experience neck, shoulder, or back discomfort.

Clients and therapists are usually not aware that a slouched posture may decrease the client’s energy level and increase the prevalence of a negative mood. Thus, we recommend that therapists incorporate posture awareness and training to optimize access to positive imagery and increase energy.

References

Singal, J. and Dahl, M. (2016, Sept 30 ) Here Is Amy Cuddy’s Response to Critiques of Her Power-Posing Research. https://www.thecut.com/2016/09/read-amy-cuddys-response-to-power-posing-critiques.html

We thank Frank Andrasik for his constructive comments.

Breathing to improve well-being

Posted: November 17, 2017 Filed under: Breathing/respiration, Exercise/movement, Neck and shoulder discomfort, Pain/discomfort, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: anxiety, Breathing, health, mindfulness, pain, respiration, stress 9 CommentsBreathing affects all aspects of your life. This invited keynote, Breathing and posture: Mind-body interventions to improve health, reduce pain and discomfort, was presented at the Caribbean Active Aging Congress, October 14, Oranjestad, Aruba. www.caacaruba.com

The presentation includes numerous practices that can be rapidly adapted into daily life to improve health and well-being.

Yes, fresh organic food is better!

Posted: October 27, 2017 Filed under: Nutrition/diet, self-healing | Tags: farming, Holistic health, longevity, non-organic foods, nutrition, organic foods, pesticides 16 Comments

Is it really worthwhile to spent more money on locally grown organic fruits and vegetables than non-organic fruits and vegetables? The answer is a resounding “YES!” Organic grown foods have significantly more vitamins, antioxidants and secondary metabolites such as phenolic compounds than non-organic foods. These compounds provide protective health benefits and lower the risk of cancer, cardiovascular disease, type two diabetes, hypertension and many other chronic health conditions (Romagnolo & Selmin, 2017; Wilson et al., 2017; Oliveira et al., 2013; Surh & Na, 2008). We are what we eat–we can pay for it now and optimize our health or pay more later when our health has been compromised.

The three reasons why fresh organic food is better are:

- Fresh foods lengthen lifespan.

- Organic foods have more vitamins, minerals, antioxidants and secondary metabolites than non-organic foods.

- Organic foods reduce exposure to harmful neurotoxic and carcinogenic pesticide and herbicides residues.

Background

With the advent of chemical fertilizers farmers increased crop yields while the abundant food became less nutritious. The synthetic fertilizers do not add back all the necessary minerals and other nutrients that the plants extract from the soil while growing. Modern chemical fertilizers only replace three components–Nitrogen, Phosphorus and Potassium–of the hundred of components necessary for nutritious food. Nitrogen (N) which promotes leaf growth; Phosphorus (P which development of roots, flowers, seeds, fruit; and Potassium (K) which promotes strong stem growth, movement of water in plants, promotion of flowering and fruiting. These are great to make the larger and more abundant fruits and vegetables; however, the soil is more and more depleted of the other micro-nutrients and minerals that are necessary for the plants to produce vitamins and anti-oxidants. Our industrial farming is raping the soils for quick growth and profit while reducing the soil fertility for future generations. Organic farms have much better soils and more soil microbial activity than non-organic farm soils which have been poisoned by pesticides, herbicides, insecticides and chemical fertilizers (Mader, 2002; Gomiero et al, 2011). For a superb review of Sustainable Vs. Conventional Agriculture see the web article: https://you.stonybrook.edu/environment/sustainable-vs-conventional-agriculture/

1. Fresh young foods lengthen lifespan. Old foods may be less nutritious than young food. Recent experiments with yeast, flies and mice discovered that when these organisms were fed old versus young food (e.g., mice were diets containing the skeletal muscle of old or young deer), the organisms’ lifespan was shortened by 18% for yeast, 13% for flies, and 13% for mice (Lee et al., 2017). Organic foods such as potatoes, bananas and raisins improves fertility, enhances survival during starvation and decreases long term mortality for fruit flies(Chhabra et al, 2013). See Live longer, enhance fertility and increase stress resistance: Eat organic foods. https://peperperspective.com/2013/04/21/live-longer-enhance-fertility-and-increase-stress-resistance-eat-organic-foods/

In addition, eating lots of fruits and vegetables decreases our risk of dying from cancer and heart disease. In a superb meta-analysis of 95 studies, Dr. Dagfinn Aune from the School of Public Health, Imperial College London, found that people who ate ten portions of fruits and vegetable per day were a third less likely to die than those who ate none (Aune et al, 2017). Thus, eat lots of fresh and organic fruits and vegetables from local sources that is not aged because of transport.

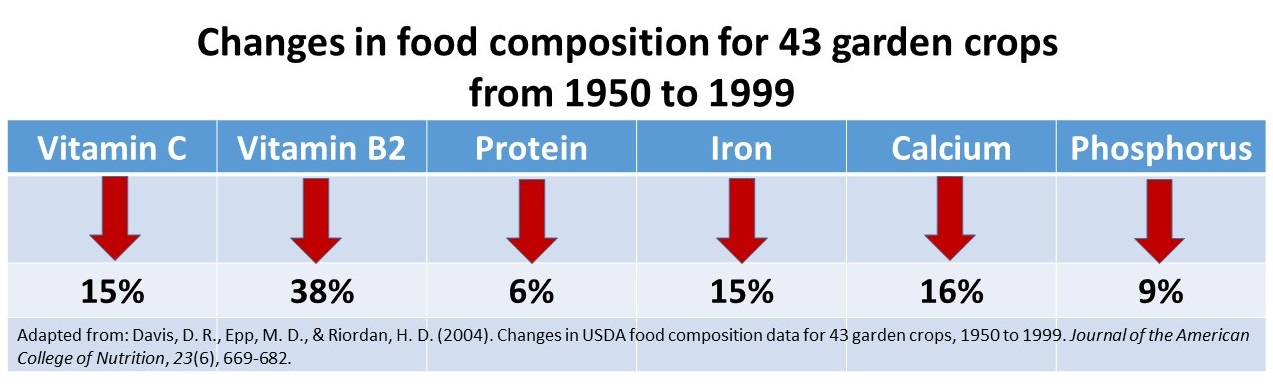

2. Organic foods have more vitamins, minerals, antioxidants and secondary metabolites than non-organic foods. Numerous studies have found that fresh organic fruits and vegetables have more vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, and secondary metabolites than non-organic ones. For example, organic tomatoes contain 57 per cent more vitamin C than non-organic ones (Oliveira et al 2013) or organic milk has more beneficial polyunsaturated fats non-organic milk (Wills, 2017; Butler et al, 2011). Over the last 50 years key nutrients of fruits and vegetables have declined. In a survey of 43 crops of fruits and vegetables, Davis, Epp, & Riordan, (2004) found a significant decrease of vitamins and minerals in foods grown in the 1950s as compared to 1999 as shown in Figure 1 (Lambert, 2015).

Figure 1. Change in vitamins and minerals from 1950 to 1999. From: Davis, D. R., Epp, M. D., & Riordan, H. D. (2004). Changes in USDA food composition data for 43 garden crops, 1950 to 1999. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 23(6), 669-682.

3, Organic foods reduce exposure to harmful neurotoxic and carcinogenic pesticide and herbicides residues. Even though, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) state that pesticide residues left in or on food are safe and non-toxic and have no health consequences, I have my doubts! Human beings accumulate pesticides just like tuna fish accumulates mercury—frequent ingesting of very low levels of pesticide and herbicide residue may result in long term harmful effects and these long term risks have not been assessed. Most pesticides are toxic chemicals and were developed to kill agricultural pests — living organisms. Remember human beings are living organisms. The actual risk for chronic low level exposure is probably unknown; since, the EPA pesticide residue limits are the result of a political compromise between scientific findings and lobbying from agricultural and chemical industries (Portney, 1992). Organic diets expose consumers to fewer pesticides associated with human disease (Forman et al, 2012).

Adopt the precautionary principle which states, that if there is a suspected risk of herbicides/pesticides causing harm to the public, or to the environment, in the absence of scientific consensus, the burden of proof that it is not harmful falls on those recommending the use of these substances (Read & O’Riordan, 2017). Thus, eat fresh locally produced organic foods to optimize health.

References

Butler, G. Stergiadis, s., Seal, C., Eyre, M., & Leifert, C. (2011). Fat composition of organic and conventional retail milk in northeast England. Journal of Dairy Science. 94(1), 24-36.http://dx.doi.org/10.3168/jds.2010-3331

Davis, D. R., Epp, M. D., & Riordan, H. D. (2004). Changes in USDA food composition data for 43 garden crops, 1950 to 1999. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 23(6), 669-682. http://www.chelationmedicalcenter.com/!_articles/Changes%20in%20USDA%20Food%20Composition%20Data%20for%2043%20Garden%20Crops%201950%20to%201999.pdf

Lambert, C. (2015). If Food really better from the farm gate than super market shelf? New Scientist.228(3043), 33-37.

Oliveira, A.B., Moura, C.F.H., Gomes-Filho, E., Marco, C.A., Urban, L., & Miranda, M.R.A. (2013). The Impact of Organic Farming on Quality of Tomatoes Is Associated to Increased Oxidative Stress during Fruit Development. PLoS ONE, 8(2): e56354. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0056354

Read, R. and O’Riordan, T. (2017). The Precautionary Principle Under Fire. Environment-Science and policy for sustainable development. September-October. http://www.environmentmagazine.org/Archives/Back%20Issues/2017/September-October%202017/precautionary-principle-full.html

Romagnolo, D. F. & Selmin, O.L. (2017). Mediterranean Diet and Prevention of Chronic Diseases. Nutr Today. 2017 Sep;52(5):208-222. doi: 10.1097/NT.0000000000000228. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29051674

Wills, A. (2017). There is evidence organic food is more nutritious. New Scientist,3114, p53.

Wilson, L.F., Antonsson, A., Green, A.C., Jordan, S.J., Kendall, B.J., Nagle, C.M., Neale, R.E., Olsen, C.M., Webb, P.M., & Whiteman, D.C. (2017). How many cancer cases and deaths are potentially preventable? Estimates for Australia in 2013. Int J Cancer. 2017 Oct 6. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31088. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28983918

Healing irritable bowel syndrome with diaphragmatic breathing*

Posted: June 23, 2017 Filed under: Breathing/respiration, self-healing | Tags: abdominal pain, diaphragmatic breathing, food intolerances, health, Holistic health, IBS, irritable bowel syndrome, pain, recurrent abdominal pain, self-care, SIBO, stress, thoracic breathing 30 CommentsErik Peper, Lauren Mason and Cindy Huey

This blog was adapted and expanded from: Peper, E., Mason, L., & Huey, C. (2017). Healing irritable bowel syndrome with diaphragmatic breathing. Biofeedback. 45(4), 83-87. DOI: 10.5298/1081-5937-45.4.04 https://biofeedbackhealth.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/a-healing-ibs-published.pdf

After having constant abdominal pain, severe cramps, and losing 15 pounds from IBS, I found myself in the hospital bed where all the doctors could offer me was morphine to reduce the pain. I searched on my smart phone for other options. I saw that abdominal breathing could help. I put my hands on my stomach and tried to expand it while I inhaled. All that happened was that my chest expanded and my stomach did not move. I practiced and practiced and finally, I could breathe lower. Within a few hours, my pain was reduced. I continued breathing this way many times. Now, two years later, I no longer have IBS and have regained 20 pounds.

– 21-year old woman who previously had severe IBS

Irritable bowel syndrome(IBS) affects between 7% to 21% of the general population and is a chronic condition. The symptoms usually include abdominal cramping, discomfort or pain, bloating, loose or frequent stools and constipation and can significantly reduce the quality of life (Chey et al, 2015). A precursor of IBS in children is called recurrent abdominal pain (RAP) which affects between 0.3 to 19% of school children (Chitkara et al, 2005). Both IBS and RAP appear to be functional illnesses, as no organic causes have been identified to explain the symptoms. In the USA, this results in more than 3.1 physician visits and 5.9 million prescriptions written annually. The total direct and indirect cost of these services exceeds $20 billion (Chey et al, 2015). Multiple factors may contribute to IBS, such as genetics, food allergies, previous treatment with antibiotics, severity of infection, psychological status and stress. More recently, changes in the intestinal and colonic microbiome resulting in small intestine bacterial overgrowth are suggested as another risk factor (Dupont, 2014).

Generally, standard medical treatments (reassurance, dietary manipulation and of pharmacological therapy) are often ineffective in reducing abdominal IBS and other abdominal symptoms (Chey et al, 2015), while complementary and alternative approaches such as relaxation and cognitive therapy are more effective than traditional medical treatment (Vlieger et, 2008). More recently, heart rate variability training to enhance sympathetic/ parasympathetic balance appears to be a successful strategy to treat functional abdominal pain (FAB) in children (Sowder et al, 2010). Sympathetic/parasympathetic balance can be enhanced by increasing heart rate variability (HRV), which occurs when a person breathes at their resonant frequency which is usually between 5-7 breaths per minute. For most people, it means breathing much slower, as slow abdominal breathing appears to be a self-control strategy to reduce symptoms of IBS, RAP and FAP.

This article describes how a young woman healed herself from IBS with slow abdominal breathing without any therapeutic coaching, reviews how slower diaphragmatic breathing (abdominal breathing) may reduce symptoms of IBS, explores the possibility that breathing is more than increasing sympathetic/parasympathetic balance, and suggests some self-care strategies to reduce the symptoms of IBS.

Healing IBS-a case report

After being diagnosed with Irritable Bowel Syndrome her Junior year of high school, doctors told Cindy her condition was incurable and could only be managed at best, although she would have it throughout her entire life. With adverse symptoms including excessive weight loss and depression, Cindy underwent monthly hospital visits and countless tests, all which resulted in doctors informing her that her physical and psychological symptoms were due to her untreatable condition known as IBS, of which no one had ever been cured. When doctors offered her what they believed to be the best option: morphine, something Cindy describes now as a “band-aid,” she was left feeling discouraged. Hopeless and alone in her hospital bed, she decided to take matters into her own hands and began to pursue other options. From her cell phone, Cindy discovered something called “diaphragmatic breathing,” a technique which involved breathing through the stomach. This strategy could help to bring warmth to the abdominal region by increasing blood flow throughout abdomen, thereby relieving discomfort of the bowel. Although suspicious of the scientific support behind this method, previous attempts at traditional western treatment had provided no benefit to recovery; therefore, she found no harm in trying. Lying back flat against the hospital bed, she relaxed her body completely, and began to breathe. Immediately, Cindy became aware that she took her breath in her chest, rather than her stomach. Pushing out all of her air, she tried again, this time gasping with inhalation. Delighted, she watched as air flooded into her stomach, causing it to rise beneath her hands, while her chest remained still. Over time, Cindy began to develop more awareness and control over her newfound strategy. While practicing, she could feel her stomach and abdomen becoming warmer. Cindy shares that for the first time in years, she felt relief from pain, causing her to cry from happiness. Later that day, she was released from the hospital, after denying any more pain medication from doctors.

Cindy continues to practice her diaphragmatic breathing as much as she can, anywhere at all, at the sign of pain or discomfort, as well as preventatively prior to what she anticipates will be a stressful situation. Since beginning her practice, Cindy says that her IBS is pretty much non-existent now. She no longer feels depressed about her situation due to her developed ability to manage her condition. Overall, she is much happier. Moreover, since this time two years ago, Cindy has gained approximately 20 pounds, which she attributes to eating a lot more. In regard to her success, she believes it was her drive, motivation, and willingness to dedicate herself fully to the breathing practice which allowed for her to develop skills and prosper. Although it was not natural for her to breathe in her stomach at first, a trait which she says she often recognizes in others, Cindy explains it was due to necessity which caused her to shift her previously-ingrained way of breathing. Upon publicly sharing her story with others for the first time, Cindy reflects on her past, revealing that she experienced shame for a long time as she felt that she had a weird condition, related to abnormal functions, which no one ever talks about. On the experience of speaking out, she affirms that it was very empowering, and hopes to encourage others coping with a situation similar to hers that there is in fact hope for the future. Cindy continues to feel empowered, confident, and happy after taking control of her own body, and acknowledges that her condition is a part of her, something of which she is proud.

Watch the in-depth interview with Cindy Huey in which she describes her experience of discovering diaphragmatic breathing and how she used this to heal herself of IBS

Video 1. Interview with Cindy Huey describing how she healed herself from IBS.

Background perspective

“Why should the body digest food or repair itself, when it will be someone else’s lunch” (paraphrased from Sapolsky (2004), Why zebras do not get ulcers).

From an evolutionary perspective, we were prey and needed to be on guard (vigilant) to the presence of predators. In the long forgotten past, the predators were tigers, snakes, and the carnivore for whom we were food as well as other people. Today, the same physiological response pathways are still operating, except that the pathways are now more likely to be activated by time urgency, work and family conflict, negative mental rehearsal and self-judgment. This is reflected in the common colloquial phrases: “It makes me sick to my stomach,” “I have no stomach for it,” “He is gutless,” “It makes me queasy,” “Butterflies in my stomach,” “Don’t get your bowels in uproar,” “Gut feelings’, or “Scared shitless.”

Whether conscious or unconscious, when threatened, our body reacts with a fight/flight/freeze response in which the blood flow is diverted from the abdomen to deep muscles used for propulsion. This results in peristalsis being reduced. At the same time the abdomen tends to brace to protect it from injury. In almost all cases, the breathing patterns shift to thoracic breathing with limited abdominal movement. As the breathing pattern is predominantly in the chest, the person increases the risk of hyperventilation because the body is ready to run or fight.

In our clinical observations, people with IBS, small intestine bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), abdominal discomfort, anxiety and panic, and abdominal pain tend to breathe more in their chest, and when asked to take breathe, they tend to inhale in their upper chest with little or no abdominal displacement. Almost anyone who experiences abdominal pain tends to hold the abdomen rigid as if the splinting could reduce the pain. A similar phenomenon is observed with female students experiencing menstrual cramps. They tend to curl up to protect themselves and breathe shallowly in their chest instead of slowly in their abdomen, a body pattern which triggers a defense reaction and inhibits regeneration. If instead they breathe slowly and uncurl they report a significant decrease in discomfort (Gibney & Peper, 2003).

Paradoxically, this protective stance of bracing the abdomen and breathing shallowly in the chest increases breathing rate and reduces heart rate variability. It reduces and inhibits blood and lymph flow through the abdomen as the defensive posture evokes the physiology of fight/flight/freeze. The reduction in venous blood and lymph flow occurs because the ongoing compression and expansion in the abdomen is inhibited by the thoracic breathing and, moreover, the inhibition of diaphragmatic breathing. It also inhibits peristalsis and digestion. No wonder so many of the people with IBS report that they are reactive to some foods. If the GI track has reduced blood flow and reduced peristalsis, it may be less able to digest foods which would affect the bacteria in the small intestine and colon. We wonder if a risk factor that contributes to SIBO is chronic lack of abdominal movement and bracing.

Slow diaphragmatic abdominal breathing to establish health

“Digestion and regeneration occurs when the person feels safe.”

Effortless, slow diaphragmatic breathing occurs when the diaphragm descends and pushes the abdominal content downward during inhalation, which causes the abdomen to become bigger. As the abdomen expands, the pelvic floor relaxes and descends. During exhalation, the pelvic floor muscles tighten slightly, lifting the pelvic floor and the transverse and oblique abdominal muscles contract and push the abdominal content upward against the diaphragm, allowing the diaphragm to relax and go upward, pushing the air out. The following video, 3D view of the diaphragm, from www.3D-Yoga.com by illustrates the movement of the diaphragm.

Video 2. 3D view of diaphragm by sohambliss from www.3D-Yoga.com,

This expansion and constriction of the abdomen occurs most easily if the person is extended, whether sitting or standing erect or lying down, and the waist is not constricted. If the arches forward in a protected pattern and the spine is flexed in a c shape, it would compress the abdomen; instead, the body is long and the abdomen can move and expand during inhalation as the diaphragm descends (see figure 1). If the person holds their abdomen tight or it is constricted by clothing or a belt, it cannot expand during inhalation. Abdominal breathing occurs more easily when the person feels safe and expanded versus unsafe or fearful and collapsed or constricted.

Figure 1. Erect versus collapsed posture note that there is less space for the abdomen to expand in the protective collapsed position. Reproduced by permission from: Clinical Somatics (http://www.clinicalsomatics.ie/

When a person breathes slower and lower it encourages blood and lymph flow through the abdomen. As the person continues to practice slower, lower breathing, it reduces the arousal and vigilance. This is the opposite state of the flight, fight, freeze response so that blood flow is increased in abdomen, and peristalsis re-occurs. When the person practices slow exhalation and breathing and they slightly tighten the oblique and transverse abdominal muscles as well as the pelvic floor and allow these muscles to relax during inhalation. When they breathe in this pattern effortless they, they often will experience an increase in abdominal warmth and an initiation of abdominal sounds (stomach rumble or borborygmus) which indicates that peristalsis has begun to move food through the intestines (Peper et al., 2016). For a detailed description see https://peperperspective.com/2016/04/26/allow-natural-breathing-with-abdominal-muscle-biofeedback-1-2/

What can you do to reduce IBS

There are many factors that cause and effect IBS, some of which we have control over and some which are our out of our control, such as genetics. The purpose of proposed suggestions is to focus on those things over which you have control and reduce risk factors that negatively affect the gastrointestinal track. Generally, begin by integrating self-healing strategies that promote health which have no negative side effects before agreeing to do more aggressive pharmaceutical or even surgical interventions which could have negative side effects. Along the way, work collaboratively with your health care provider. Experiment with the following:

- Avoid food and drinks that may irritate the gastrointestinal tract. These include coffee, hot spices, dairy products, wheat and many others. If you are not sure whether you are reacting to a food or drink, keep a detailed log of what you eat and drink and how you feel. Do self-experimentation by eating or drinking the specific food by itself as the first food in the morning. Then observe how you feel in the next two hours. If possible, eat only organic foods that have not been contaminated by herbicides and pesticides (see: https://peperperspective.com/2015/01/11/are-herbicides-a-cause-for-allergies-immune-incompetence-and-adhd/).

- Identify and resolve stressors, conflicts and problems that negatively affect you and drain your energy. Keep a log to identify situations that drain or increase your subjective energy. Then do problem solving to reduce those situations that drain your energy and increase those situations that increase your energy. For a detailed description of the practice see https://peperperspective.com/2012/12/09/increase-energy-gains-decrease-energy-drains/

Often the most challenging situations that we cannot stomach are those where we feel defeated, helpless, hopeless and powerless or situations where we feel threatened– we do not feel safe. Reach out to other both friends and social services to explore how these situations can be resolved. In some cases, there is nothing that can be done except to accept what is and go on.

- Feel safe. As long as we feel unsafe, we have to be vigilant and are stressed which affects the GI track. Explore the following:

- What does safety mean for you?

- What causes you to feel unsafe from the past or the present?

- What do you need to feel safe?

- Who can offer support that you feel safe?

Reflect on these questions and then explore and implement ways by which you can create feeling more safe.

- Take breaks to regenerate. During the day, at work and at home, monitor yourself. Are you pushing yourself to complete tasks. In a 24/7 world with many ongoing responsibilities, we are unknowingly vigilant and do not allow ourselves to rest and relax to regenerate. Do not wait till you feel tired or exhausted. Stop earlier and take a short break. The break can be a short walk, a cup of tea or soup, or looking outside at a tree. During this break, think about positive events that have happened or people who love you and for whom you feel love. When you smile and think of someone who loves you, such as a grandparent, you may relax and for that moment as you feel safe which allows regeneration to begin.

- Observe how you inhale. Take a deep breath. If you feel you are moving upward and becoming a little bit taller, your breathing is wrong. Put one hand on your lower abdomen and the other on your chest and take a deep breath. If you observe your chest lifted upward and stomach did not expand, your breathing is wrong. You are not breathing diaphragmatically. Watch the following video, The correct way to breathe in, on how to observe your breathing and how to breathe diaphragmatically.

- Learn diaphragmatic breathing. Take time to practice diaphragmatic breathing. Practice while lying down and sitting or standing. Let the breathing rate slow down to about six breaths per minute. Exhale to the count of four and then let it trail off for two more counts, and inhale to the count of three and let it trail for another count. Practice this sitting and lying down (for more details on breathing see: https://peperperspective.com/2014/09/11/a-breath-of-fresh-air-improve-health-with-breathing/.

- Sitting position. Exhale by feeling your abdomen coming inward slightly for the count of four and trailing off for the count of two, then allow the lower ribs to widen, abdomen expand–the whole a trunk expands–as you inhale while the shoulders stay relaxed for a count of three. Allow it to trail off for one more count before you again begin to exhale. Be gentle, do not rush or force yourself. Practice this slower breathing for five minutes. Focus more on the exhalation and allowing the air to just flow in. Give yourself time during the transition between inhalation and exhalation.

- Lying down position. While lying on your back, place a two to five-pound weight such as a bag of rice on your stomach as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Lying down and practicing breathing with two to five-pound weight on stomach (reproduced by permission from Gorter and Peper, 2011.

As you inhale push the weight upward and also feel your lower ribs widen. Then allow exhalation to occur by the weight pushing the abdominal content down which pushes the diaphragm upward. This causing the breath to flow out. As you exhale, imagine the air flowing out through your legs as if there were straws inside your legs. When your attention wanders, smile and bring it back to imagining the air flowing down your legs during exhalation. Practice this for twenty minutes. Many people report that during the practice the gurgling in their abdomen occurs which is a sign that peristalsis and healing is returning.