Breathe Away Menstrual Pain- A Simple Practice That Brings Relief *

Posted: November 22, 2025 Filed under: attention, behavior, biofeedback, Breathing/respiration, cognitive behavior therapy, education, emotions, Neck and shoulder discomfort, Pain/discomfort, posture, relaxation, self-healing, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: dysmenorrhea, health, meditation, menstrual cramps, mental-health, mindfulness, wellness 2 CommentsAdapted from: Peper, E. Harvey, R., Chen, & Heinz, N. (2025). Practicing diaphragmatic breathing reduces menstrual symptoms both during in-person and synchronous online teaching. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, Published online: 25 October 2025. https://rdcu.be/eMJqt https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-025-09745-7

“Once again, the pain starts—sharp, deep, and overwhelming—until all I can do is curl up and wait for it to pass. There’s no way I can function like this, so I call in sick. The meds take the edge off, but they don’t really fix anything—they just mask it for a little while. I usually don’t tell anyone it’s menstrual pain; I just say I’m not feeling well. For the next couple of days, I’m completely drained, struggling just to make it through.

Many women experience discomfort during menstruation, from mild cramps to intense, even disabling pain. When the pain becomes severe, the body instinctively responds by slowing down—encouraging rest, curling up to protect the abdomen, and often reaching for medication in hopes of relief. For most, the symptoms ease within a day or two, occasionally stretching into three, before the body gradually returns to balance.

Another helpful approach is to practice slow abdominal breathing, guided by a breathing app FlowMD. In our study led by Mattia Nesse, PhD, in Italy, the response of one 22-year-old woman illustrated the power of this simple practice.

“Last night my period started, so I was a bit discouraged because I knew I’d get stomach pain, etc. On the other hand, I said, “Okay, let’s see if the breathing works,” and it was like magic — incredible. I’ll need to try it more times to understand whether it consistently has the same effect, but right now it truly felt magical. Just 3 minutes of deep breathing with the app were enough, and I’m not saying I don’t feel any pain anymore, but it has decreased a lot, so thank you! Thank you again for this tool… I’m really happy!”

The Silent Burden of Menstrual Pain

Menstrual pain, or dysmenorrhea, affects most women at some point in their lives — often silently. For many, the monthly cycle brings not only physical discomfort but also shame, fatigue, and interruptions to work or school. It is one of the leading causes of absenteeism and reduced productivity worldwide (Itani et al., 2022; Thakur & Pathania, 2022). In addition, the estimated health cost ranged from US $1367 to US$ 7043 per year (Huang et al., 2021). Yet, despite its prevalence, most women are never taught how to use their own physiology to ease these symptoms.

The Study (Peper et al, 2025)

Seventy-five university women participated across two upper-division Holistic Health courses. Forty-nine practiced 30 minutes per day of breathing and relaxation over five weeks as well as practicing the moment they anticipated or felt discomfort; twenty-six served as a comparison group without a specific daily self-care routine. Students rated change in menstrual symptoms on a scale from –5 (“much worse”) to +5 (“much better”). For the detailed steps in training, see the blog: https://peperperspective.com/2023/04/22/hope-for-menstrual-cramps-dysmenorrhea-with-breathing/ (Peper et al., 2023).

What changed

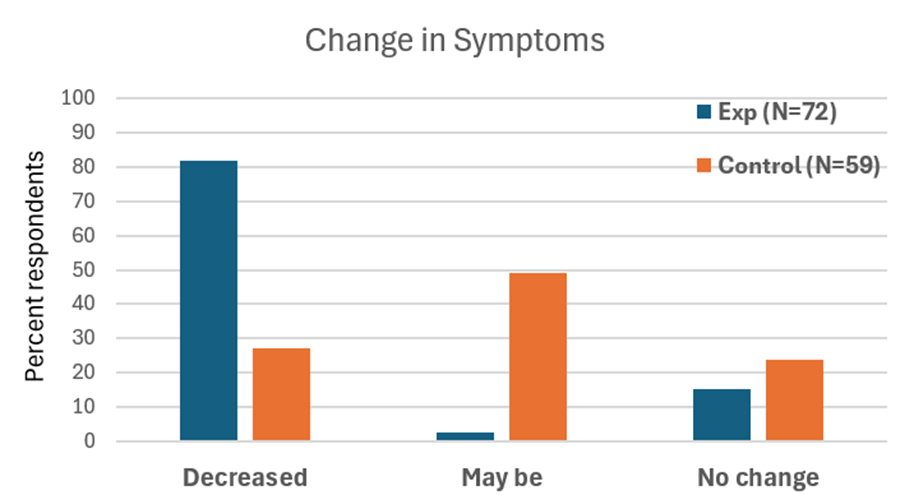

The results were striking. Women who practiced breathing and relaxation showed significant decrease in menstrual symptoms compared to the non-intervention group (p = 0.0008) as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Decrease in menstrual symptoms as compared to the control group after implementing slow diaphragmatic breathing.

Why does breathing and posture change have a beneficial effect?

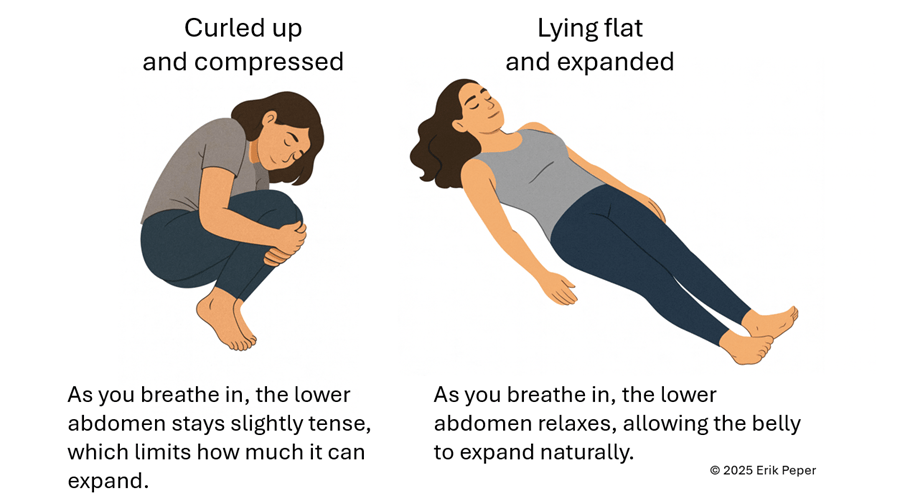

When you stay curled up, your abdomen becomes compressed, leaving little room for the lower belly to relax or for the diaphragm to move freely. The result? Tension builds, and pain often increases.

To reverse this, create space for relaxation. Gently loosen your waist and let your abdomen expand as you inhale. Uncurl your body—lengthen your spine and open your chest, as shown in Figure 2. With each easy breath, you invite calm and allow your body to shift from tension to ease.

Figure 2. Curling up compresses the abdomen and prevents relaxation of the lower belly. In contrast, lying flat with the body gently expanded allows the abdomen to move freely with each breath, which can help reduce menstrual discomfort.

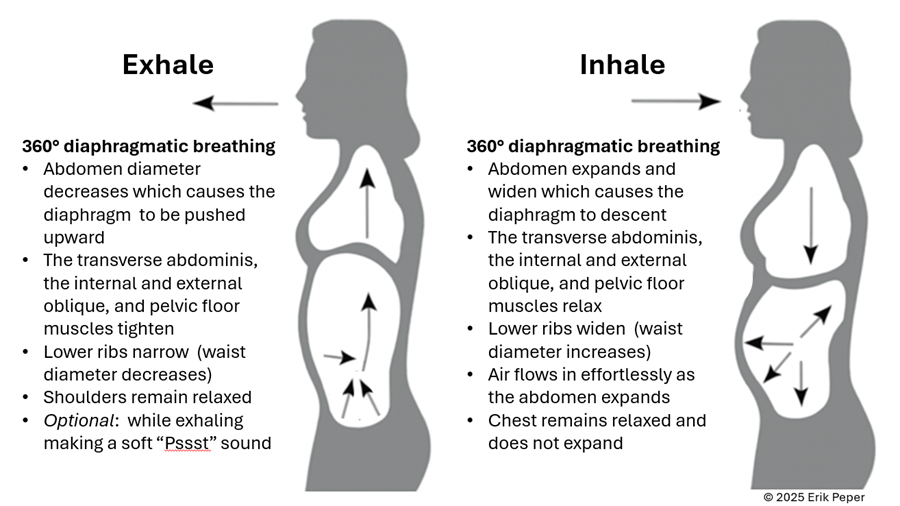

In contrast, slow abdominal or diaphragmatic breathing activates the body’s natural relaxation response. It quiets the stress-driven sympathetic nervous system, calms the mind, and improves circulation in the abdominal area. With each slow breath in, the abdomen gently expands while the pelvic floor and abdominal muscles relax. As you exhale, these muscles naturally tighten slightly, helping to massage and move blood and lymph through the abdominal region. This rhythmic movement supports healing and ease, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3. The dynamic process of diaphragmatic breathing.

The process of slower, lower diaphragmatic breathing

When lying down, rest comfortably on your back with your legs slightly apart. Allow your abdomen to rise naturally as you inhale and fall as you exhale. As you breathe out, imagine the air flowing through your abdomen, down your legs, and out through your feet. To deepen this sensation, you can ask a partner to gently stroke from your abdomen down your legs as you exhale—helping you sense the flow of release through your body.

Gently focus on slow, effortless diaphragmatic breathing. With each inhalation, your abdomen expands, and the lower belly softens. As you exhale, the abdomen gently goes down pushing the diaphragm upward and allowing the air to leave easily. Breathing slowly—about six breaths per minute—helps engage the body’s natural relaxation response.

If you notice that your breath is staying high in your chest instead of expanding through the abdomen, your symptoms may not improve and can even increase. One participant experienced this at first. After learning to let her abdomen expand with each inhalation while keeping her shoulders and chest relaxed, her next menstrual cycle was markedly easier and far less uncomfortable. The lesson is clear: technique matters.

“During times of pain, I practiced lying down and breathing through my stomach… and my cramps went away within ten minutes. It was awesome.” — 22-year-old college student

“Whenever I felt my cramps worsening, I practiced slow deep breathing for five to ten minutes. The pain became less debilitating, and I didn’t need as many painkillers.” — 18-year-old college student

These successes point out that it’s not just breathing — it’s how you breathe by providing space for the abdomen to expand during inhalation.

Practice: How to Do Diaphragmatic Breathing

- Find a quiet space. Lie on your back or sit comfortably erect with your shoulders relaxed.

- Place one hand on your chest and one on your abdomen.

- Inhale slowly through your nose for about 3–4 seconds. Let your abdomen expand as you breathe in — your chest should remain relaxed.

- Exhale gently through your mouth for 4—6 seconds, allowing the abdomen to fall or constrict naturally.

- As you exhale imagine the air moving down your arms, through your abdomen, down your legs, and out your feet

- Practice daily for 20 minutes and also for 5–10 minutes during the day when menstrual discomfort begins.

- Add warmth. Placing a warm towel or heating pad over your abdomen can enhance relaxation while lying on your back and breathing slowly.

With regular practice and implementing it during the day when stressed, this simple method can reduce cramps, promote calm, and reconnect you with your body’s natural rhythm.

Implement the ABCs during the day

The ABC sequence—adapted from the work of Dr. Charles Stroebel, who developed The Quieting Reflex (Stroebel, 1982)—teaches a simple way to interrupt stress reactions in real time. The moment you notice discomfort, pain, stress, or negative thoughts, interrupt the cycle with a simple ABC strategy:

A — Adjust your posture

Sit or stand tall, slightly arch your lower back and allowing the abdomen to expand while you inhale and look up. This immediately shifts your body out of the collapsed “defense posture’ and increases access to positive thoughts (Tsai et all, 2016; Peper et al., 2019)

B — Breathe

Allow your abdomen to expand as you inhale slowly and deeply. Let it get smaller as you exhale. Gently make a soft hissing sound as you exhale while helps the abdomen and pelvic floor to tighten. Then allow the abdomen to relax and widen which without effort draws the air in during inhalation. As you exhale, stay tall and imagine the air flowing through you and down your legs and out your feet.

C — Concentrate

Refocus your attention on what you want to do and add a gentle smile. This engages positive emotions, the smile helps downshift tension.

The video clip guides you through the ABCs process.

Integrate the breathing during the day by implementing your ABCs

When students practice relaxation technique and this method, they reported greater reductions in symptoms compared with a control group. By learning to notice tension and apply the ABC steps as soon as stress arises, they could shift their bodies and minds toward calm more quickly, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Change in symptoms after practicing a sequential relaxation and breathing techniques for four weeks.

Takeaway

Menstrual pain doesn’t have to be endured in silence or masked by medication alone. By practicing 30 minutes of slow diaphragmatic breathing daily and many times during the day, women may be able to reduce pain, stress, and discomfort — while building self-awareness and confidence in their body’s natural rhythms thereby having the opportunity to be more productive.

We recommend that schools and universities include self-care education—especially breathing and relaxation practices—as part of basic health curricula as this approach is scalable. Teaching young women to understand their bodies, manage stress, and talk openly about menstruation can profoundly improve well-being. It not only reduces physical discomfort but also helps dissolve the stigma that still surrounds this natural process,

Remember: Breathing is free—available anytime, anywhere and is helpful in reducing pain and discomfort. (Peper et al., 2025; Joseph et al., 2022)

See the following blogs for more in-depth information and practical tips on how to learn and apply diaphragmatic breathing:

REFERENCES

Itani, R., Soubra, L., Karout, S., Rahme, D., Karout, L., & Khojah, H.M.J. (2022). Primary Dysmenorrhea: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment Updates. Korean J Fam Med, 43(2), 101-108. https://doi.org/10.4082/kjfm.21.0103

Huang, G., Le, A. L., Goddard, Y., James, D., Thavorn, K., Payne, M., & Chen, I. (2022). A systematic review of the cost of chronic pelvic pain in women. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada, 44(3), 286–293.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogc.2021.08.011

Joseph, A. E., Moman, R. N., Barman, R. A., Kleppel, D. J., Eberhart, N. D., Gerberi, D. J., Murad, M. H., & Hooten, W. M. (2022). Effects of slow deep breathing on acute clinical pain in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Evidence-Based Integrative Medicine, 27, 2515690X221078006. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515690X221078006

Peper, E., Booiman, A. & Harvey, R. (2025). Pain-There is Hope. Biofeedback, 53(1), 1-9. http://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-53.01.16

Peper, E., Chen, S., Heinz, N., & Harvey, R. (2023). Hope for menstrual cramps (dysmenorrhea) with breathing. Biofeedback, 51(2), 44–51. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-51.2.04

Peper, E., Harvey, R., Chen, S., & Heinz, N. (2025). Practicing diaphragmatic breathing reduces menstrual symptoms both during in-person and synchronous online teaching. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. Published online: 25 October 2025. https://rdcu.be/eMJqt https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-025-09745-7

Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Hamiel, D. (2019). Transforming thoughts with postural awareness to increase therapeutic and teaching efficacy. NeuroRegulation, 6(3),153-169. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.6.3.1533-1

Stroebel, C. (1982). The Quieting Reflex. New York: Putnam Pub Group. https://www.amazon.com/Qr-Quieting-Charles-M-D-Stroebel/dp/0399126570/

Thakur, P. & Pathania, A.R. (2022). Relief of dysmenorrhea – A review of different types of pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments. MaterialsToday: Proceedings.18, Part 5, 1157-1162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2021.08.207

Tsai, H. Y., Peper, E., & Lin, I. M. (2016). EEG patterns under positive/negative body postures and emotion recall tasks. NeuroRegulation, 3(1), 23-27. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.3.1.23

*Edited with the help of ChatGPT 5

Ensorcelled: Breaking the Digital Enchantment

Posted: October 7, 2025 Filed under: ADHD, attention, behavior, cellphone, computer, digital devices, education, emotions, healing, health, laptops, techstress, Uncategorized | Tags: anxiety, depression, health, human connection, life, loneliness, media addictdion, mental-health, storytelling 1 Comment

My mom called, “Stop playing on your computer and come for dinner!” I heard her, but I was way too into my game. It felt like I was actually inside it. I think I yelled “Yeah!” back, but I didn’t move.

A few seconds later, I was totally sucked into this awesome world where I was conquering other galaxies. My avatar was super powerful, and I was winning this crazy battle.

Then, all of a sudden, my mom came into my room and just turned off the computer. I was so mad. I was about to win! The real world around me felt boring and empty. I didn’t even feel hungry anymore. I didn’t say anything, I just wanted to go back to my game.

For some, the virtual world feels more real and exciting than the actual one. It can seem more vivid precisely because they have not yet tasted the full, multi-dimensional richness of real human connection, those moments when you feel seen, touched, and understood.

This theme comes vividly alive in my son Eliot Peper’s new novella, Ensorcelled. I am so proud of him. He has crafted a story in which a young boy, captured by the spell of the immersive digital world, discovers that real-life experiences carry far deeper meaning. I won’t give away the plot, but the story creates the experience, it doesn’t just tell it. It reminds us that meaning and belonging arise through genuine connection, not through screens. As Eliot writes, “Sometimes a story is the only thing that can save your life.” It’s a story everyone should read.

The effects of our immersive digital world

Our new world of digital media can take over the reality of actual experiences. It is no wonder that more young people feel stressed and have social anxiety when they have to make an actual telephone call instead of texting (Jin, 2025). They also experience a significant increase in anxiety and depression and feel more awkward initiating in-person social communication with others. The increase in mental health problems and social isolation affects predominantly those who are cellphone and social media natives; namely, those who started to use social media after Facebook was released in 2004 and the iPhone in 2007 (Braghieri et al., 2022).

Students who are most often on their phone whether streaming videos, scrolling, texting, watching YouTube, Instagram or TikTok, and more importantly responding to notifications from phones when they are socializing, report higher levels of loneliness, depression and anxiety as shown inf Figure 1 (Peper & Harvey 2018). They also report less positive feelings and energy when they communicate with each other online as compared to in person (Peper & Harvey, 2024).

Figure 1. The those with the highest phone use were the most lonely, depressed and anxious (Peper and Harvey, 2018).

Even students’ sexual activity has decreased in U.S. high-school from 2013 to 2023 and young adults (ages 18-44) from 2000-2018 (CDC, 2023; Ueda et al., 2020). Much of this may be due to the reality that adolescents have reduced face-to-face socializing (dating, parties, going out) while increasing their time on digital media (Twenge et al., 2019).

What to do

As a parent it often feels like a losing battle to pull your child, or even yourself, away from the intoxicating digital media, since the digital world is supercharged with AI-generated media. It is all aimed at capturing eyeballs (your attention and time), resulting reducing genuine human social connection. (Peper at al., 2020; Haidt, 2024). To change behavior is challenging and yet rewarding. If possible, implement the following (Peper at al., 2020; Twenge, 2025; Haidt, 2024):

- Create tech-free zones. Keep phones and devices out of bedrooms, the dinner table, and family gatherings. Make these spaces sacred for real connection.

- Avoid screens before bedtime. Turn off screens at least an hour before bed. Replace scrolling with quiet reflection, reading, or gentle stretching. Read or tell actual stories before bedtime.

- Explore why we turn to digital media. Before you open an app, ask: Why am I doing this? Am I bored, anxious, or avoiding something? Awareness shifts behavior.

- Provide unstructured time. Let yourself and your children be bored sometimes. Boredom sparks creativity, imagination, and self-discovery.

- Create shared experiences. Plan family activities that don’t involve screens—cooking, hiking, playing music, or simply talking. Real connection satisfies what digital media only mimics.

- Implement social support. Coordinate with other parents, friends, or colleagues to agree on digital limits. Shared norms make it easier to follow through.

- Model what you want your children to do. Children imitate what they see. When adults practice digital restraint, kids learn that real life matters more than screen life.

We have a choice.

We can set limits now and experience real emotional connection and growth or become captured, enslaved, and manipulated by the corporate creators, producers and sellers of media.

Read Ensorcelled. which uses storytelling, the traditional way to communicate concepts and knowledge. Read it, share it. It may change your child’s life and your own.

Available from

Signed copy by author: https://store.eliotpeper.com/products/ensorcelled

Paperback: https://www.amazon.com/Ensorcelled-Eliot-Peper/dp/1735016535/

Kindle: https://www.amazon.com/Ensorcelled-Eliot-Peper-ebook/dp/B0FLGQC3BS/

References

Braghieri, L., Levy, R., & Makarin, A. (2022). Social Media and Mental Health (July 28, 2022) http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3919760

CDC. (2023). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). Youth Risk Behavior Survey: Data summary & trends report 2011–2021. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/index.htm

Haidt, J. (2024). The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness. New York: Penguin Press. https://www.amazon.com/Anxious-Generation-Rewiring-Childhood-Epidemic/dp/0593655036

Jin, B. (2025). Avoidance and Anxiety About Phone Calls in Young Adults: The Role of Social Anxiety and Texting Controllability. Communication Reports, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/08934215.2025.2542562

Peper, E. & Harvey, R. (2018). Digital addiction: increased loneliness, depression, and anxiety. NeuroRegulation. 5(1),3–8. doi:10.15540/nr.5.1.3 5(1),3–8. http://www.neuroregulation.org/article/view/18189/11842

Peper, E. & Harvey, R. (2024). Smart phones affects social communication, vision, breathing, and mental and physical health: What to do! Townsend Letter-Innovative Health Perspectives, September 15, 2024. https://townsendletter.com/smartphone-affects-social-communication-vision-breathing-and-mental-and-physical-health-what-to-do/

Peper, E., Harvey, R. & Faass, N. (2020). TechStress: How Technology is Hijacking Our Lives, Strategies for Coping, and Pragmatic Ergonomics. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books.

Ueda, P., Mercer, C. H., Ghaznavi, C., & Herbenick, D. (2020). Trends in frequency of sexual activity and number of sexual partners among adults aged 18 to 44 years in the US, 2000–2018. JAMA Network Open, 3(6), e203833. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3833

Twenge, J.M. (2025). 10 Rules for Raising Kids in a High-Tech World: How Parents Can Stop Smartphones, Social Media, and Gaming from Taking Over Their Children’s Lives. New York: Atria Books. https://www.amazon.com/Rules-Raising-Kids-High-Tech-World/dp/1668099993

Twenge, J. M., Spitzberg, B. H., & Campbell, W. K. (2019). Less in-person social interaction with peers among U.S. adolescents in the 21st century and links to loneliness. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 36(6), 1892-1913. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407519836170

Exploring the pain-brain-breathing connection

Posted: August 30, 2025 Filed under: attention, behavior, Breathing/respiration, cognitive behavior therapy, education, emotions, healing, meditation, Pain/discomfort, placebo, self-healing, Uncategorized | Tags: deliberate harm Leave a commentIf you’re curious about how the mind and body interplay in shaping pain—or looking for real, actionable techniques grounded in research listen to this episode of the Heart Rate Variability Podcast, Matt Bennett interviews Dr. Erik Peper about his article and blogpost Pain – There Is Hope. The conversation takes listeners beyond the common perception of pain as merely a physical response. It is a balanced mix of scientific depth and real-life applications, especially valuable for anyone interested in self-healing, holistic health, or understanding mind-body medicine. Moreover, it explains how pain is shaped by posture, breathing, mindset, and emotional context. Finally, it provides practical strategies to shift the pain experience, offering an uplifting and science-backed blend of understanding and hope.

If you find this helpful, let me know! And feel free to share it with friends and post it on your social channels so more people can benefit.

Blogs that complement this interview

If you want to explore further, check out the companion blog posts I hve created to expand on the themes from this discussion. These blogs highlight practical strategies, scientific insights, and everyday applications.

Use the power of your mind to transform health and aging

Posted: February 18, 2025 Filed under: attention, behavior, cancer, CBT, cognitive behavior therapy, COVID, education, health, meditation, mindfulness, Pain/discomfort, placebo, stress management, Uncategorized | Tags: health, imimune function, longevity, mental-health, mind-body, nutrition, Reframing, wellness Leave a commentMost of the time when I drive or commute by BART, I listen to podcasts (e.g., Freakonomics, Hidden Brain, this podcast will kill you, Science VS, Huberman Lab). although many of the podcasts are highly informative; , rarely do I think that everyone could benefit from it. The recent podcast, Using your mind to control your health and longevity, is an exception. In this podcast, neuroscientist Andrew Huberman interviews Professor Ellen Langer. Although it is three hours and twenty-two minute long, every minute is worth it (just skip the advertisements by Huberman which interrupts the flow). Dr. Langer delves into how our thoughts, perceptions, and mindfulness practices can profoundly influence our physical well-being.

She presents compelling evidence that our mental states are intricately linked to our physical health. She discusses how our perceptions of time and control can significantly impact healing rates, hormonal balance, immune function, and overall longevity. By reframing our understanding of mindfulness—not merely as a meditative practice but as an active, moment-to-moment engagement with our environment—we can harness our mental faculties to foster better health outcomes. The episode also highlights practical applications of Dr. Langer’s research, offering insights into how adopting a mindful approach to daily life can lead to remarkable health benefits. By noticing new things and embracing uncertainty, individuals can break free from mindless routines, reduce stress, and enhance their overall quality of life. This podcast is a must-listen for anyone interested in the profound connection between mind and body. It provides valuable tools and perspectives for those seeking to take an active role in their health and well-being through the power of mindful thinking. It will change your perspective and improve your health. Listen to or watch the interview:

Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QYAgf_lfio4

Useful blogs to reduce stress

Act now before history repeats itself

Posted: January 23, 2025 Filed under: education | Tags: Brexit, Gladwell, history, Musk, Nazi, Politics, Trump 20 CommentsOn November 8–9, 1923, Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party launched a bold attempt to overthrow Germany’s federal government in Munich, aiming to establish a nationalist regime. Known as the Beer Hall Putsch, this failed coup grabbed global headlines, shocking the world. Hitler and his associates were quickly arrested, and after a dramatic 24-day trial, they were convicted of treason. Despite being sentenced to prison, Hitler served less than a year before his release—time he used to lay the groundwork for his infamous future.

Fast forward to January 6, 2021: history echoed in eerie ways. Fueled by false claims of a stolen election, groups like the Oath Keepers and Proud Boys, with the backing of then-President Donald Trump, stormed the U.S. Capitol in a desperate bid to block Joe Biden’s certification as the newly elected President. The attack left the nation reeling, its democratic institutions shaken.

By August 2024, over 1,400 individuals had been charged with federal crimes related to the insurrection, and more than 900 had been convicted. Yet, in a shocking twist, Trump—returning to the presidency—undermined the justice system on his first day back in office. He issued sweeping pardons for approximately 1,500 individuals and commuted the sentences of 14 key allies connected to the Capitol attack.

Are we seeing echoes of 1930s Germany in today’s America? In 1935, the Nuremberg Laws stripped citizenship from anyone not deemed “Aryan,” cementing a dangerous precedent of exclusion and authoritarianism. Now on the first day in office, President Trump President Donald Trump’s executive order that purports to limit birthright citizenship-

Fast forward to now: former President Donald Trump’s blanket clemency and pardons for Proud Boys and other January 6 participants seem to signal unconditional support for his loyal MAGA followers. The message is clear—carry out Trump’s agenda without fear of legal consequences because he’ll have your back. Could the Proud Boys become a modern-day equivalent of Hitler’s Brownshirts (Sturmabteilung, or SA)—used to protect Trump’s movement, suppress dissent, and disrupt political opposition? This question grows even more pressing in an age where social media wields enormous influence. With Elon Musk controlling X (formerly Twitter), critics worry about the platform’s role in shaping discourse. Musk’s actions and statements have led some to compare his influence to that of Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi Minister of Propaganda. My fears are heightened after Musk made gestures similarly to that associated with Nazi symbolism during Trump’s inauguration.

Read about the possible impact of the Trump policies in the New York Times, “Donald Trump Is Running Riot” by David French, the outstanding New York Times’ opinion writer.

How Did We Get Here? A Warning from History

How could this happen? It might seem that the majority of Americans support Trump’s actions, but the numbers tell a different story. In reality, only about 33% of eligible voters cast their ballots for Trump. Over one-third of eligible voters stayed home, choosing not to vote at all. To put it in perspective, Trump’s 2024 total of 77,284,118 votes fell short of Biden’s 81,284,666 votes in 2020. The difference wasn’t that Trump gained overwhelming support—it was that fewer people showed up for Harris, and 36% did not vote.

This scenario isn’t unique to America. Take Brexit, for example: In January 2020, the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union, a decision driven by a passionate and sometimes misinformed minority. Now, just a few years later, many in England regret that choice, realizing the long-term consequences of their decision to leave the EU.

The truth is, in almost every major upheaval, it only takes about 30% of highly dedicated and committed individuals—some might even call them zealots—to shift the course of history. It was true for Brexit, it was true for Hitler, and is now true for Trump.

If you want to understand how this dynamic works, Malcolm Gladwell’s The Revenge of the Tipping Point offers invaluable insights into how a small but determined group can take control of the narrative and change the agenda for everyone.

Now is the time to act. It’s not too late to support democratic institutions and ensure the U.S. doesn’t slide into the abyss. Staying silent or staying home isn’t an option—democracy needs defenders–silence in the face of oppression is siding with the oppressor.

Implement your New Year’s resolution successfully[1]

Posted: December 29, 2024 Filed under: attention, behavior, CBT, cognitive behavior therapy, education, emotions, Exercise/movement, healing, health, self-healing | Tags: goal setting, health, lifestyle, motivation, performance, personal-development Leave a comment

Adapted from: Peper, E. Pragmatic suggestions to implement behavior change. Biofeedback.53(2), 41-45. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-53.02.05

Ready to crush your New Year’s resolutions and actually stick to them this time? Whether you’re determined to quit vaping or smoking, cut back on sugar and processed foods, reduce screen time, get moving, volunteer more, or land that dream job, sticking to your goals is the real challenge. We’ve all been there: kicking off the year with ambitious plans like, “I’ll work out every day,” or “I’m done with junk food for good.” But a few weeks in? The gym is a distant memory, the junk food stash is back, and those cigarettes are harder to let go of than expected.

So, how can you make this year different? Here are some tried-and-true tips to help you turn those resolutions into lasting habits:

Be clear of your goal and state exactly what you want to do (Pilcher et al., 2022; Latham & Locke, 2006).

Did you know your brain is super literal and doesn’t process “not” the way you think it does? For example, if you say, “I will not smoke,” your brain has to first imagine you smoking, then mentally cross it out. Guess what? By rehearsing the act of smoking in your mind, you’re actually increasing the chances that you’ll light up again.

Think of it like this: hand a four-year-old a cup of hot chocolate and ask them to walk it over to someone across the room. Halfway there, you call out, “Be careful, don’t spill it!” What usually happens? Yep, the hot chocolate spills. That’s because the brain focuses on “spill,” not the “don’t.” Now, imagine instead you say, “You’re doing great! Keep walking steadily.” Positive framing reinforces the action you want to see. The lesson is to reframe your goals in a way that focuses on what you want to achieve, not what you’re trying to avoid. Let’s look at some examples to get you started:

| Negative framing | Positive framing |

| I plan to stop smoking | I choose to become a nonsmoker |

| I will eat less sugar and ultra-processed foods | I will shop at the farmer’s market, buy more fresh vegetable and prepare my own food. |

| I will reduce my negative thinking (e.g., the glass is half empty). | I will describe events and thoughts positively (e.g., the class is half full). |

Describe what you want to do positively.

Be precise and concrete.

The more specific you can describe what you plan to do, the more likely will it occur as illustrated in the following examples.

| Imprecise | Concrete and specific |

| I will begin exercising. | I will buy the gym membership next week Monday and will go to the gym on Monday, Wednesday and Friday right after work at 5:30pm for 45 minutes. |

| I will reduce my angry outbursts, | Before I respond, I will take a slow breath, look up, relax my shoulders and remind myself that the other person is doing their best. |

| I want to limit watching streaming videos | At home, I will move the couch so that it does not face the large TV screen, and I have enrolled in a class to learn another language and I will spent 30 minutes in the evening practicing the new language. |

| I will stop smoking | When I feel the initial urge to smoke, I stand up, do a few stretches, and practice box breathing and remind myself that I am a nonsmoker. |

Describe in detail what you will do.

Identify the benefits of the old behavior that you want to change and how you can achieve the same benefits with your new behavior. (Peper et al, 2002)

When setting a New Year’s resolution, it’s easy to focus on the perks of the new behavior and the harms of the old behavior while overlooking the benefits your old habit provided. However, if you don’t plan ways to achieve the same benefits, the old behavior provided, it’s much harder to stick to your goal.

Before diving into your new resolution, take a moment to reflect. What did your old behavior do for you? What needs did it meet? Once you identify those, you can develop strategies to achieve the same benefits in healthier, more constructive ways.

For example, let’s say your goal is to stop smoking. Smoking might have helped you relax during stressful moments or provided a social activity with friends. To make the switch, you’ll need to find alternatives that deliver similar results, like practicing deep-breathing exercises to manage stress or inviting friends for a walk instead of a smoke break. By creating a plan to meet those needs, you’ll set yourself up for lasting success.

| Benefits of smoking | How to achieve the same benefits when being a none smoker |

| Stress reduction | I will learn relaxation and diaphragmatic breathing. The moment, I feel the urge to smoke, I sit up, look up, raise my shoulder and dropped them, and breathe slowly |

| Breaks during work | I will install a reminder on my cellphone to ping and each time it pings, I stop, stand up, walk around and stretch. |

| Meeting with friends | I will tell my friends, not to offer me a cigarette and I will spent time with friends who are non-smokers. |

| Rebelling against my parents who were opposed to smoking | I will explore how to be independent without smoking |

Describe your benefits and how you will achieve them.

Reduce the cues that evoke the old behavior and create new cues that will trigger the new behavior (Peper & Wilson, 2021).

A lot of our behavior is automatic—shaped by classical conditioning, just like Pavlov’s dog. Remember the famous experiment? Pavlov paired the sound of a bell with food, and after a while, the bell alone made the dog salivate (McLeod, 2024). We’re not so different.

Think about it: if you’ve gotten into the habit of smoking in your car, simply sitting in the driver’s seat can trigger the automatic urge to grab a cigarette. Or, if you tend to feel depressed when you’re home but better when you’re out with friends, your home environment might be acting as a cue for those feelings.

Interestingly, many people find it easier to change habits in a new environment. Why? Because there are no built-in triggers to reinforce the behavior they’re trying to change. This highlights how much of what we often call “addiction” might actually be conditioned behavior, reinforced by familiar cues in our surroundings. By recognizing the power of these triggers can help you disrupt old patterns. By creating a fresh environment or consciously changing your responses to cues, you can take control and start forming new, healthier habits.

This concept has been understood for centuries by some hunting and gathering societies. When something tragic happened—like the death of a family member in a hut—the community would often burn the hut to “eliminate the evil spirit.” Beyond the spiritual aspect, this practice served a practical purpose: it removed all the physical cues that reminded people of their loss, making it easier to focus on the present and move forward.

Of course, I’m not suggesting you destroy your home. But the underlying principle still holds true in modern times. In fact, many Northern European cultures incorporate a version of this idea through the ritual of Spring Cleaning. By decluttering, rearranging furniture, and refreshing the home, the old cues are removed and create a sense of renewal.

So often we forget that cues in our environment play a powerful role in triggering our behavior. By identifying the triggers that evoke old habits and finding ways to remove or change them, you can create a fresh environment that supports your goals. For example, if you’re trying to stop snacking on junk food late at night, consider rearranging your pantry so the tempting items are out of sight—or better yet, replace them with healthier options. Small changes like this can have a big impact on your ability to stay on track.

| Cues that triggered the behavior | How cues were changed |

| In the evening going to the kitchen and getting the chocolate from the cupboard. | Buying fruits and have them on the table and not buying chocolate. If I do buy chocolate store it on the top shelf away so that I do not see it or store it in the freezer. |

| Getting home and being depressed. | Clean the house, change the furniture around and put positive picture high up on the wall. |

| Smoking in the car. | Replace the car with another car that no one had smoked in and spray the care with pine scent. |

Identify the cues that trigger your behavior and how you changed them.

Identify the first sensation that triggered the behavior you would like to change.

Whether it’s smoking, drinking, scratching your skin, spiraling into negative thoughts, or eating too many pastries, once a behavior starts, it can feel nearly impossible to stop. That’s why the key is to catch yourself before the habit takes over., t’s much easier to interrupt a pattern at the very first sign—the initial trigger—rather than after you’ve fully dived into the behavior. Yet how often do we find ourselves saying, “Next time, I’ll do it differently”?

Here’s the strategy: identify the first trigger. This could be a physical sensation, an emotion, a thought, or an external cue. Once you’re aware of that first flicker of a trigger, redirect your thoughts and actions toward what you actually want, rather than letting the automatic behavior take control. For example:

I just came home at 10:15 PM and felt lonely and slightly depressed. I walked into the kitchen, opened the fridge, grabbed a beer, and drank it. Then, I reached for another bottle.

Observing this behavior, the first trigger was the loneliness and slight depression upon arriving home. Recognizing that feeling in the moment offers an opportunity to pause and make a conscious choice. Instead of heading to the fridge, you could redirect your actions—call a friend, go for a quick walk, or write down your thoughts in a journal. By catching that initial trigger, you can focus yourself toward healthier behaviors and break the cycle.

| First sensation | Changed response to the sensation |

| I observed that the first sensation was feeling tired and lonely. | When I entered the house, instead of going to the kitchen, I stretched, looked up and took a deep breath and then called a close friend of mine. We talked for ten minutes and then I went to bed. |

Identify your first sensation and how you changed your behavior.

Incorporate social support and social accountability (Drageset, 2021).

Doing something on your own often requires a lot of willpower, and sticking to it every time can feel like an uphill battle. Take this example:

My goal is to exercise every other morning. But last night, I stayed up late and felt tired in the morning, so I skipped my workout.

Sound familiar? Now imagine if I’d planned to meet a workout buddy. Knowing someone was counting on me would’ve gotten me out of bed, even if I was tired, because I wouldn’t want to let them down.

Accountability can make all the difference. Another powerful strategy is sharing your goals publicly. When you announce your plans on social media or to friends and family, you create a sense of commitment—not just to yourself but to others. It’s like having a built-in support system cheering you on and holding you accountable. Whether it’s finding a partner, joining a group, or sharing your progress online, involving others can help turn your resolutions into habits you’re more likely to stick with.

Describe a strategy to increase social support and accountability.

Be honest in identifying what motivates you.

Exercising, eating healthy foods, thinking positively, or being on time are laudable goals; however, it often feels like work doing the “right” thing. To increase success, analyze what really helped you be successful. For example:

Many years ago, I decided that I should exercise more. Thus, I drove from house to the track and ran eight laps. I did this for the next three weeks and then stopped exercising. Eventually, I pushed myself again to exercise and after a while stopped again. The same pattern kept repeating. I would exercise and fall off the wagon and stop. Later that fall, I met a woman who was a jogger and we became friends and for the next year we jogged together and even did races. During this time, I did not experience any effort to go jogging. After a year, she broke up with me and once again, I had to use willpower to go jogging and my old pattern emerged and after a few days I stopped jogging even though I felt much better after having jogged.

I finally, asked what is going on? I realized that the joy of the jogging was running with a friend. Once, I recognized this, instead using will power to go running, I spent my willpower finding people with whom I could exercise. With these new friends, running did not depend upon my willpower– It only depended on making running dates with my new friends.

Explore factors that will allow you to do your activity without having to use willpower.

Conclusion

These seven strategies are just a starting point—there are countless other techniques that can help you stick to your New Year’s resolutions. For example, keeping a log, setting reminders, or rewarding yourself for progress are all powerful ways to stay on track. The real magic happens when your new behavior becomes part of your routine—embedded in your habitual patterns. The more automatic it feels, the greater your chances of long-term success.

So, take joy in identifying, implementing, and maintaining your resolutions. Let them enhance your well-being and become second nature. Share your successful strategies with me and others—it could be just the inspiration someone else needs to achieve their goals, too.

References

Drageset, J. (2021). Social Support. In: Haugan G, Eriksson M, editors. Health Promotion in Health Care – Vital Theories and Research [Internet]. Cham (CH): Springer, Chapter 11. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK585650/ https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-63135-2_11

Latham, G. P., & Locke, E. A. (2006). Enhancing the Benefits and Overcoming the Pitfalls of Goal Setting. Organizational Dynamics, 35(4), 332–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2006.08.008

McLeod, S. (2024). Classical Conditioning: How It Works With Examples.Simple Psychology. Accessed December 29, 2024. https://www.simplypsychology.org/classical-conditioning.html

Peper, E., Gibney, H. K. & Holt, C. (2002). Make Health Happen. Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall-Hunt. (Pp 185-192). https://he.kendallhunt.com/make-health-happen

Peper, E. & Wilson, V. (2021). Optimize the learning state: techniques and habits. Biofeedback, 9(2), 46-49. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-49-2-04

Pilcher, S., Schweickle, M. J., Lawrence, A., Goddard, S. G., Williamson, O., Vella, S. A., & Swann, C. (2022). The effects of open, do-your-best, and specific goals on commitment and cognitive performance. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 11(3), 382–395. https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000301

For detailed suggestions, see the following blogs:

[1] Edited with the help of ChatGPT.

Increase attention, concentration and school performance

Posted: August 15, 2024 Filed under: ADHD, attention, behavior, Breathing/respiration, digital devices, education, ergonomics, posture, screen fatigue, stress management, vision, zoom fatigue | Tags: cellphone, concentration 5 CommentsReproduced from: Peper, E., Harvey, R., & Rosegard, E. (2024). Increase attention, concentration and school performance with posture feedback. Biofeedback, 52(2), 48-52. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-52.02.07

When I sit with good posture on my computer, I am significantly more engaged in what I’m doing. When I slouch on my computer I tend to procrastinate, go on my phone, and get distracted so it ends up taking much longer to do my work when my posture is bad.…I have ADHD and I struggle a lot with my mind wandering when I should be paying attention. Having good posture really helps me to lock in and focus.—22 year old male student.

Over the past two decades, there has been a significant increase in the prevalence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety, and depression. ADHD rates have increased from 6% in 1997 to approximately 10% in 2018 (CDC, 2022). The rates of anxiety among 18–25 year-olds have also increased from 7.97% in 2008 to 14.66% in 2018 (Goodwin et al., 2020). Students are more distracted, stressed and exhausted (Hanscom, 2022; Hoyt et al., 2021). The more students are distracted, the lower their academic achievement (Feng et al., 2019). In our recent class survey of more than 100 junior and senior college students on the first day of class, 54% reported that they were tired and dreading the day when they woke up. When you are tired and stressed it is difficult to focus attention and have clarity of thought. Their self-report is similar to the mental health trends in the United States by age group in 2008–2019. Mental health of young people has significantly deteriorated over the last 15 years (Braghieri et al., 2021/2023).

The increase in psychological distress is most prevalent in people ages 18–29 and who were brought up with the cellphone (the iPhone was introduced in 2007) and social media. Now when students enter a class, they tend to sit down, look down at their cellphone while slouching, and they do not make contact with most other students unless instructed or reminded by the instructor. When instructed to talk to another student for less than 5 minutes (e.g., share something positive that happened to you this week), 93% of the students reported an increase in subjective energy and alertness (Peper, 2024).

As a group, students are social media and cell phone natives and thus have many distractions and stimuli to which they continuously respond. It is not surprising that the average attention span has decreased from 150 seconds in 2004 to 44 seconds in 2021 (Mark, 2023). More importantly, they now tend to sit in a slouched collapsed position, which facilitates access to hopeless, helpless, powerless and defeated thoughts and memories (Tsai et al., 2016; Peper et al., 2017) and reduces cognitive performance when performing mental math (Peper et al., 2018). Sitting slouched and looking down also reduces peripheral awareness and increases shallow thoracic breathing—a breathing pattern that increases the risk of anxiety. Experience this yourself.

For a minute, look at your cellphone while intensely reading the text or searching social media in the following two positions: sitting straight up and looking straight ahead at your cell phone or slouching and looking down at your cell phone, as shown in Figure 1. Most likely, your experience is similar to the findings from the classroom observational study in which half the students looked down and the other half looked straight ahead and then reversed their positions (Peper, unpublished). They then compared the subjective experience associated with the position. In the slouched position, most experienced a reduction in peripheral awareness and breathed more shallowly (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Effect of slouching or looking straight ahead on vision and breathing.

The slouched position reduces social awareness and decreases awareness of external stimuli as illustrated in Steve Cutts’ superb animation, Mobile world (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wUW1wjlKvmY).

Given the constant stimulation, distractions and shortened attention span, it is more challenging to be calm and have clarity of mind when having to study or take an exam at school. As educators, we constantly explore ways to engage students and support their learning and especially share quick skills they can use to optimize performance (Peper& Wilson, 2021). In previous research, Harvey et al., 2020 showed that students who used posture feedback improved their health scores compared to the control group. The purpose of this paper is to share a 4-week class assignment by which numerous students reported an increase in attention, concentration, confidence, school performance and a decrease in stress.

Participants: 18 undergraduate students (7 males and 11 females, average age 22 [STDEV 2.2]) enrolled in an upper division class. As a report about an effort to improve the quality of a classroom activity, this report of findings was exempted from Institutional Review Board oversight.

Equipment: Wearable posture feedback device, UpRight Go 2, which the person wears on their neck and which provides vibratory feedback whenever they slouch, as shown in Figure 2. It is used in conjunction with the cellphone app that allows them to calibrate the feedback device.

Figure 2. Attachment of posture feedback device on neck or spine and the app to calibrate the device.

Procedure: Students attended the 3-hour weekly class that explored autogenic training, somatic awareness, psychobiology of stress, the role of posture, and the psychophysiology of respiration. The lectures included short experiential practices demonstrating the body-mind connections such as imagining a lemon to increase salivation, the effect of slouched versus erect posture on evoking positive/empowering or hopeless/helpless/powerless/defeated thoughts, and the effect of sequential 70% exhalation for 30 seconds on increasing anxiety (Tsai et al., 2016; Peper et al., 2017).

Each week for 4 weeks the students were assigned a self-practice that they would implement daily at home and record their experiences. At the end of the week, they reviewed their own log and summarized their own observations (benefits, difficulties). During the next class session, they met in small groups of 5 to 6 students to discuss their experiences and extract common themes.

The 4-week curriculum was sequenced as follows:

Week 1

- Lecture on the benefits/harms of posture with experiential practices (effect of slouching vs erect on access to hopeless/helpless/powerless thoughts versus optimistic and empowering thoughts; posture and arm strength (Peper, 2022).

- Homework assignments:

- Watch the great Ted Talk and one of the most viewed by Amy Cuddy (2013), “Your body language shapes who you are.”

- Keep a detailed log to monitor situations where they slouched and identify situations that were associated with slouching.

Week 2

- Lecture on psychophysiology and class discussion in which students shared their experiences of slouching; namely, what were the triggers, how it affected them and what they could do to change.

- Demonstration, explanation, and how to use the posture feedback device, UpRight Go 2.

- Homework assignment: Wear UpRight Go 2 during the day, use it in different settings (studying, walking, work), and keep a log. When it vibrates (slouching) observe what was going on and change your behavior such as when tired>get rest or do exercise; when depressed>change internal language; ergonomic issues>change the environment, posture>give yourself lower back support.

Week 3

- Class discussion on what to do when slouching is triggered by tiredness, negative and hopeless thoughts, ergonomics such as laptop placement and chair. Students meet in groups to share their experiences and what they did in response to the vibratory feedback.

- Homework assignment: Continue to wear the UpRight Go 2 during the day and keep a log.

Week 4

- Class discussion in groups of five students about their experiences of slouching, what to do and how it affects them.

- Homework assignment: Wear UpRight Go 2 during the day and keep a log. Submit a paper that describes their experience with the posture feedback from the UpRight Go 2 and fill out a short anonymous survey in which they rated their change in experience since using the posture feedback device on a scale from 3 (worse) to 0 (no change) to 3 (better) .

Results

All students reported that wearing the feedback device increased attention and concentration as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Amount of time using the UpRight Go 2:On the average the students used the device 4.8 days a week (STDEV 2.0) and 2.2 hours per day (STDEV 1.3).

Location of use:Although most students practiced sitting in front of their computer, they also reported using it while at work, playing pool or doing yoga and even while seeing a therapist.

Discussion

All the students reported that the posture feedback helped them to become more aware of slouching and when they then interrupted their slouching, they experienced an increase in energy and a decrease in stress. As a 21-year-old male student said: “I felt more engaged with whatever I was doing. I tend to … daydream and get distracted, but I experience much less of that when I sit with good posture.”

Many reported that it helped identify their emotions when they were feeling overwhelmed. Then they could sit up, shift their perspective, and many reported a decrease in back and neck pain as well as a decrease in tiredness. When participants wear non-invasive wearables that provide accurate feedback, they are often surprised what triggers are associated with feedback or how their performance improves when they respond to the feedback signal by changing their thoughts and behavior. This posture self-awareness project should be embedded in strategies that optimize the learning state as described by Peper & Wilson (2021).

To the students’ surprise, they were often unaware that they started to slouch, nor were they aware of how much this slouching was connected to their emotions, mental state or external factors. For example, one student reported that he wore the device while being in a therapy session. All of a sudden, it vibrated. At that moment, he realized that he was becoming anxious, although he and therapist were unaware. He then shared what happened with the therapist, and that helped the therapeutic process.

The benefits may not only be due to posture change but that the students became aware and interrupted their habitual pattern. This process is similar to that described by Charles Stroebel (1985) when he taught patients the Quieting Reflect that reduced numerous somatic symptoms ranging from headaches to hypertension.

The posture feedback intervention is both simple and challenging since it requires the participants to wear the device, identify factors that trigger the slouching, and interrupt their automatic patterns by changing posture and behavior whenever they felt the vibratory feedback. The awareness gave them the opportunity to change posture and thoughts. By shifting to an upright posture, they experienced that they could concentrate more and have increased energy. As a 19-year-old female student wrote: “My breathing was better and sitting in an upright position gave me more energy when doing tasks.”

Conclusion

We recommend that a 4-week home practice module that incorporates wearable posture feedback is offered to all students to enhance their well-being. With the posture feedback, participants can increase their awareness of slouching, identify situations that trigger slouch, and learn strategies to shift their posture, thoughts, emotions and external environment to optimize maintaining an empowered position. As a 20-year old male student reported, “The app helped me when I was feeling overwhelmed and then I would sit up. When I had it on, I did a lot of work. I was more concentrated.”

Explore the following blogs for more background and useful suggestions

References

Braghieri, L., Levy, R., & Makarin, A. (2023). Media and mental health (July 28, 2022). SSRN. (Original work published 2021). https://ssrn.com/abstract=3919760 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3919760

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). ADHD through the years. Attention-Deficit / Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Retrieved March 27, 2023, from https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/timeline.html

Cuddy, A. (2012) Your body language may shape who you are. TED Talk. Retrieved March 16, 2024 from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ks-_Mh1QhMc

Feng, S., Wong, Y. K., Wong, L. Y., & Hossain, L. (2019). The internet and Facebook usage on academic distraction of college students, Computers & Education, 134, 41-49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j

Goodwin, R. D., Weinberger, A. H., Kim, J. H., Wu. M., & Galea, S. (2020). Trends in anxiety among adults in the United States, 2008–2018: Rapid increases among young adults. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 130, 441–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.08.014

Hanscom, N. (2022). Students, staff notice higher levels of student distraction this school year, reflect on potential causes. Retrieved September 28, 2023, from https://dgnomega.org/13162/feature/students-staff-notice-higher-levels-of-student-distraction-this-school-year-reflect-on-potential-causes/

Harvey, R., Peper, E., Mason, L., & Joy, M. (2020). Effect of posture feedback training on health. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 45(1), 59–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-020-09457-0

Hoyt, L. T., Cohen, A. K., Dull, B., Castro, E. M., & Yazdani, N. (2021). “Constant stress has become the new normal”: Stress and anxiety inequalities among U.S. college students in the time of COVID-19. Journal of Adolescent Health. 68(2), 270–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.10.030

Mark, G. (2023). Attention span: A groundbreaking way to restore balance, happiness and productivity. Hanover Square Press.

Peper, E. (2022, March 4). A breath of fresh air: Breathing and posture to optimize health. [Conference presentation at the 2nd Virtual Ergonomics Summit], Krista Burns, PhD. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PhV7Ulhs38s

Peper, E. (2024a). Change in energy and alertness after talking with each other versus looking at cellphone. Data collected from HH380 class fall 2023. Unpublished.

Peper, E. (2024b). Changes in vision and breathing when looking down or straight ahead at the cellphone. Data collected from HH380 class, Spring, 2024, San Francisco State University. Unpublished.

Peper, E., Harvey, R., Mason, L., & Lin, I.-M. (2018). Do better in math: How your body posture may change stereotype threat response. NeuroRegulation, 5(2), 67–74. http://dx.doi.org/10.15540/nr.5.2.67

Peper, E., Lin, I.-M., Harvey, R., & Perez, J. (2017). How posture affects memory recall and mood. Biofeedback.45(2), 36–41. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-45.2.01

Peper, E. & Wilson, V. (2021). Optimize the learning state: Techniques and habits. Biofeedback, 49(2), 46-49. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-49-2-04

Stroebel, C. F. (1985). QR: The Quieting Reflex. Berkley. https://www.amazon.com/Qr-Quieting-Charles-M-D-Stroebel/dp/0399126570

Tsai, H. Y., Peper, E., & Lin, I.-M.(2016). EEG patterns under positive/negative body postures and emotion recall tasks. NeuroRegulation, 3(1), 23–27. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.3.1.23

Grandmother Therapy: A Common-Sense Approach to Health and Wellness

Posted: July 24, 2024 Filed under: ADHD, attention, behavior, education, Evolutionary perspective, Exercise/movement, Nutrition/diet, Pain/discomfort, relaxation, self-healing | Tags: anxiety, depression, epilepsy, exhaustion, grandmother therapy, health, insomnia, life style change, mental-health, therapy 1 CommentErik Peper, PhD and Angelika Sadar, MA

In today’s fast-paced world, college students and young adults often struggle with various health issues. From anxiety and depression to ADHD and epilepsy, these challenges can significantly impact their daily lives. But what if the solution to many of these problems lies in something as simple as “Grandmother Therapy”?

What is Grandmother Therapy? Grandmother Therapy is all about going back to basics and establishing healthy lifestyle habits. It’s the common-sense approach that our grandmothers might have suggested: regular sleep patterns, balanced nutrition, increased social connections, and regular physical activity.

The Problem: Many college students:

- Skip breakfast before their first class

- Rely on fast food and sugary stimulants

- Have irregular sleep schedules

- Spend excessive time on gaming and social media

The Medical Approach: Often, the quick solution is medication:

- Depression? Take antidepressants.

- Insomnia? Use sleeping pills.

- Anxiety? Try anti-anxiety medication.

- ADHD? Prescribe Ritalin or similar drugs.

While these treatments may help manage symptoms, they often overlook the underlying lifestyle factors contributing to these issues.

The Grandmother Therapy Approach:

- Establish regular sleep patterns

- Adopt healthy eating habits

- Increase social connections

- Incorporate regular physical activity

- Reduce gaming and social media use

Case Study #1: The Power of Sleep

This illustrates the simple intervention of having a bedtime routine. A college student in a holistic health class complained that she was tired most of the time and had difficulty focusing her attention and continuously drifted off in class.

Here is her reported sleep schedule:

- last night I went to bed at 3am and woke up 7;

- the day before, I went to bed at 1pm and woke up at 6,

- two nights before, I went to bed at 4pm and woke up at 10 am.

Holistic treatment approach:

Set a sleep schedule: she was provided with information about the importance of having a regular pattern of sleep and waking. Namely, go to bed at the same time and get up 8 hours later. She agreed to do an experiment for a week to go to bed at 12 and wake up at 8m. To her surprise, she felt so much more energized and could pay attention in class during the week of the experiment.

Case Study #2: Beyond Seizures: A Holistic Approach to Treating Psychogenic Nonepileptic Seizures

This case study highlights the importance of a comprehensive, lifestyle-based approach to treating psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES). It follows a 24-year-old male student initially diagnosed with intractable epilepsy, experiencing over 10 seizures per week that didn’t respond to medication.

Key points:

1. Initial misdiagnosis: Despite normal MRI and EEG results, the client was initially treated for epilepsy.

2. Limited assessment: Traditional medical evaluations focused solely on seizure descriptions and diagnostics, overlooking crucial lifestyle factors.

3. Comprehensive evaluation: A psychophysiological assessment revealed high sympathetic arousal, including rapid breathing, sweaty palms, and muscle tension.

4. Lifestyle factors: The client’s diet consisted of high-glycemic fast foods, excessive caffeine, alcohol, and daily marijuana use. He also had significant student debt and a history of abdominal surgery.

Holistic treatment approach:

– Dietary changes: Switching to unprocessed, low-glycemic foods and increasing vegetable and fruit intake

– Breathing techniques: Learning and practicing slow diaphragmatic breathing

– Stress management: Addressing underlying stressors and practicing relaxation techniques

– Supplements: Adding omega-3 and multivitamins to support brain health

Remarkable results: Within four months, the patient became seizure-free, reduced marijuana use significantly, and decreased medication dosage.

Summary

These cases underscore the potential of integrating lifestyle modifications and stress management techniques in treating attention, anxiety and even psychogenic nonepileptic seizures; offering hope for patients who don’t respond to traditional treatments alone. Before turning to medication or complex treatments, consider the power of Grandmother Therapy. By addressing fundamental lifestyle factors, we can often improve our health and well-being significantly. Remember, sometimes the most effective solutions are the simplest ones.

The Challenges of Simplicity: While Grandmother Therapy may seem straightforward, its simplicity can make it challenging to implement. It requires commitment and a willingness to change long-standing habits.

Implement many Life Style Changes at once: Recommending one change at the time is logical; however, participants will more likely experience rapid benefits and are more motivated to continue when they change multiple lifestyle factors at once.

Call to Action: Are you struggling with health issues? Try implementing some aspects of Grandmother Therapy in your life. Implement changes and see how they impact your overall well-being.

Please let us know your experience with implementing Grandmother Therapy.

See the following blogs for more background information

Reflections on the increase in Autism, ADHD, anxiety and depression: Part 2- Exposure to neurotoxins and ultra-processed foods

Posted: June 30, 2024 Filed under: ADHD, attention, behavior, CBT, digital devices, education, emotions, Evolutionary perspective, health, mindfulness, neurofeedback, Nutrition/diet, Uncategorized | Tags: ADHD, anxiety, depression, diet, glyphosate, herbicide, herbicites, mental-health, neurofeedback, pesticides, supplements', ultraprocessed foods, vitamins 4 CommentsAdapted from: Peper, E. & Shuford, J. (2024). Reflections on the increase in Autism, ADHD, anxiety and depression: Part 2- Exposure to neurotoxins and ultra-processed foods. NeuroRegulation, 11(2), 219–228. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.11.2.219

Look at your hand and remember that every cell in your body including your brain is constructed out the foods you ingested. If you ingested inferior foods (raw materials to be built your physical structure), then the structure can only be inferior. If you use superior foods, you have the opportunity to create a superior structure which provides the opportunity for superior functioning. -Erik Peper

Summary

Mental health symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), Autism, anxiety and depression have increased over the last 15 years. An additional risk factor that may affect mental and physical health is the foods we eat. Even though, our food may look and even taste the same as compared to 50 years ago, it contains herbicide and pesticide residues and often consist of ultra-processed foods. These foods (low in fiber, and high in sugar, animal fats and additives) are a significant part of the American diet and correlate with higher levels of inattention and hyperactivity in children with ADHD. Due to affluent malnutrition, many children are deficient in essential vitamins and minerals. We recommend that before beginning neurofeedback and behavioral treatments, diet and lifestyle are assessed (we call this Grandmother therapy assessment). If the diet appears low in organic foods and vegetable, high in ultra-processed foods and drinks, then nutritional deficiencies should be assessed. Then the next intervention step is to reduce the nutritional deficiencies and implement diet changes from ultra-processed foods to organic whole foods. Meta-analysis demonstrates that providing supplements such as Vitamin D, etc. and reducing simple carbohydrates and sugars and eating more vegetables, fruits and healthy fats during regular meals can ameliorate the symptoms and promote health.

The previous article and blog, Reflections on the increase in Autism, ADHD, anxiety and depression: Part 1-bonding, screen time, and circadian rhythms, pointed out how the changes in bonding, screen time and circadian rhythms affected physical and mental health (Peper, 2023a; Peper, 2023b). However, there are many additional factors including genetics that may contribute to the increase is ADHD, autism, anxiety, depression, allergies and autoimmune illnesses (Swatzyna et al., 2018). Genetics contribute to the risk of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD); since, family, twin, and adoption studies have reported that ADHD runs in families (Durukan et al., 2018; Faraone & Larsson, 2019). Genetics is in most cases a risk factor that may or may not be expressed. The concept underlying this blog is that genetics loads the gun and environment and behavior pulls the trigger as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Interaction between Genetics and Environment

The pandemic only escalated trends that already was occurring. For example, Bommersbach et al (2023) analyzed the national trends in mental health-related emergency department visits among USA youth, 2011-2021. They observed that in the USA, Over the last 10 years, the proportion of pediatric ED visits for mental health reasons has approximately doubled, including a 5-fold increase in suicide-related visits. The mental health-related emergency department visits increased an average of 8% per year while suicide related visits increased 23.1% per year. Similar trends have reported by Braghieri et al (2022) from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Mental health trends in the United States by age group in 2008–2019. The data come from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Reproduced with permission from Braghieri, Luca and Levy, Ro’ee and Makarin, Alexey, Social Media and Mental Health (July 28, 2022) https://ssrn.com/abstract=3919760 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3919760

The trends reported from this data shows an increase in mental health illnesses for young people ages 18-23 and 24-29 and no changes for the older groups which could be correlated with the release of the first iPhone 2G on June 29, 2007. Thus, the Covid 19 pandemic and social isolation were not THE CAUSE but an escalation of an ongoing trend. For the younger population, the cellphone has become the vehicle for personal communication and social connections, many young people communicate more with texting than in-person and spent hours on screens which impact sleep (Peper, 2023a). At the same time, there are many other concurrent factors that may contributed to increase of ADHD, autism, anxiety, depression, allergies and autoimmune illnesses.

Without ever signing an informed consent form, we all have participated in lifestyle and environmental changes that differ from that evolved through the process of evolutionary natural selection and promoted survival of the human species. Many of those changes in lifestyle are driven by demand for short-term corporate profits over long-term health of the population. As exemplified by the significant increase in vaping in young people as a covert strategy to increase smoking (CDC, 2023) or the marketing of ultra-processed foods (van Tulleken, 2023).

This post focusses how pesticides and herbicides (exposure to neurotoxins) and changes in our food negatively affects our health and well-being and is may be another contributor to the increase risk for developing ADHD, autism, anxiety and depression. Although our food may look and even taste the same compared to 50 years ago, it is now different–more herbicide and pesticide residues and is often ultra-processed. lt contains lower levels of nutrients and vitamins such as Vitamin C, Vitamin B2, Protein, Iron, Calcium and Phosphorus than 50 years ago (Davis et al, 2004; Fernandez-Cornejo et al., 2014). Non-organic foods as compared to organic foods may reduce longevity, fertility and survival after fasting (Chhabra et al., 2013).

Being poisoned by pesticide and herbicide residues in food

Almost all foods, except those labeled organic, are contaminated with pesticides and herbicides. The United States Department of Agriculture reported that “Pesticide use more than tripled between 1960 and 1981. Herbicide use increased more than tenfold (from 35 to 478 million pounds) as more U.S. farmers began to treat their fields with these chemicals” (Fernandez-Cornejo, et al., 2013, p 11). The increase in herbicides and pesticides is correlated with a significant deterioration of health in the United States (Swanson, et al., 2014 as illustrated in the following Figure 3.

Figure 3. Correlation between Disease Prevalence and Glyphosate Applications (reproduced with permission from Swanson et al., 2014.

Although correlation is not causation and similar relationships could be plotted by correlating consumption of ultra-refined foods, antibiotic use, decrease in physical activity, increase in computer, cellphone and social media use, etc.; nevertheless, it may suggest a causal relationship. Most pesticides and herbicides are neurotoxins and can accumulate in the person over time this could affect physical and mental health (Bjørling-Poulsen et al., 2008; Arab & Mostaflou, 2022). Even though the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has determined that the residual concentrations in foods are safe, their long-term safety has not been well established (Leoci & Ruberti, 2021). Other countries, especially those in which agribusiness has less power to affect legislation thorough lobbying, and utilize the research findings from studies not funded by agribusiness, have come to different conclusions…

For example, the USA allows much higher residues of pesticides such as, Round-Up, with a toxic ingredient glyphosate (0.7 parts per million) in foods than European countries (0.01 parts per million) (Wahab et al., 2022; EPA, 2023; European Commission, 2023) as is graphically illustrated in figure 4.

Figure 4: Percent of Crops Sprayed with Glyphosate and Allowable Glyphosate Levels in the USA versus the EU

The USA allows this higher exposure than the European Union even though about half of the human gut microbiota are vulnerable to glyphosate exposure (Puigbo et al., 2022). The negative effects most likely would be more harmful in a rapidly growing infant than for an adult. Most likely, some individuals are more vulnerable than others and are the “canary in mine.” They are the early indicators for possible low-level long-term harm. Research has shown that fetal exposure from the mother (gestational exposure) is associated with an increase in behaviors related to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorders and executive function in the child when they are 7 to 12 years old (Sagiv et al., 2021). Also, organophosphate exposure is correlated with ADHD prevalence in children (Bouchard et al., 2010). We hypothesize this exposure is one of the co-factors that have contributed to the decrease in mental health of adults 18 to 29 years.

At the same time as herbicides and pesticides acreage usage has increased, ultra-processed food have become a major part of the American diet (van Tulleken, 2023). Eating a diet high in ultra-processed foods, low in fiber, high sugar, animal fats and additives has been associated with higher levels of inattention and hyperactivity in children with ADHD; namely, high consumption of sugar, candy, cola beverages, and non-cola soft drinks and low consumption of fatty fish were also associated with a higher prevalence of ADHD diagnosis (Ríos-Hernández et al., 2017).

In international studies, less nutritional eating behaviors were observed in ADHD risk group as compared to the normal group (Ryu et al., 2022). Artificial food colors and additives are also a public health issue and appear to increase the risk of hyperactive behavior (Arnold et al., 2012). In a randomized double-blinded, placebo controlled trial 3 and 8/9 year old children had an increase in hyperactive behavior for those whose diet included extra additives (McCann et al., 2007). The risk may occur during fetal development since poor prenatal maternal is a critical factor in the infants neurodevelopment and is associated with an increased probability of developing ADHD and autism (Zhong et al., 2020; Mengying et al., 2016).

Poor nutrition even affects your unborn grandchild

Poor nutrition not only affects the mother and the developing fetus through epigenetic changes, it also impacts the developing eggs in the ovary of the fetus that can become the future granddaughter (Wilson, 2015). At birth, the baby has all of her eggs. Thus, there is a scientific basis for the old wives tale that curses may skip a generation. Providing maternal support is even more important since it affects the new born and the future grandchild. The risk may even begin a generation earlier since the grandmother’s poor nutrition as well as stress causes epigenetic changes in the fetus eggs. Thus 50% of the chromosomes of the grandchild were impacted epigenetically by the mother’s and grandmother’s dietary and health status .

Highly processed foods